Abstract

Background:

There is a lack of national level data from India on prescription of psychotropics by psychiatrists.

Aim and Objective:

This study aimed to assess the first prescription handed over to the psychiatrically ill patients whenever they contact a psychiatrist.

Materials and Methods:

Data were collected across 11 centers. Psychiatric diagnosis was made as per the International Classification of Diseases Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders 10th edition criteria based on Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, and the data of psychotropic prescriptions was collected.

Results:

Study included 4480 patients, slightly more than half of the subjects were of male (54.8%) and most of the participants were married (71.8%). Half of the participants were from the urban background, and about half (46.9%) were educated up to or beyond high school. The most common diagnostic category was that of affective disorders (54.3%), followed by Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (22.2%) and psychotic disorders (19.1%). Other diagnostic categories formed a very small proportion of the study participants. Among the antidepressants, most commonly prescribed antidepressant included escitalopram followed by sertraline. Escitalopram was the most common antidepressant across 7 out of 11 centers and second most common in three centers. Among the antipsychotics, the most commonly prescribed antipsychotic was olanzapine followed by risperidone. Olanzapine was the most commonly prescribed antipsychotic across 6 out of 11 centers and second most common antipsychotic across rest of the centers. Among the mood stabilizers valproate was prescribed more often, and it was the most commonly prescribed mood stabilizer in 8 out of 11 centers. Clonazepam was prescribed as anxiolytic about 5 times more commonly than lorazepam. Clonazepam was the most common benzodiazepine prescribed in 6 out of the 11 centers. Rate of polypharmacy was low.

Conclusion:

Escitalopram is the most commonly prescribed antidepressant, olanzapine is the most commonly prescribed antipsychotic and clonazepam is most commonly prescribed benzodiazepine. There are very few variations in prescription patterns across various centers.

Keywords: Antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, mood stabilizers, prescription patterns

INTRODUCTION

Study of prescriptions is considered as part of “drug utilization,” which encompasses the study of marketing, distribution and prescription of various drugs in society, along with evaluation of its medical, social, and economic consequences’. The basic aim of studying drug utilization is to encourage and facilitate rational use of medications.[1]

Psychotropic prescriptions play an important role in the management of various psychiatric disorders. Considering the importance of psychotropic medications in the management of various psychiatric disorders, almost all treatment guidelines formulated by various scientific organizations provide information about how to use psychotropic agents in the management of a particular disorder. However, it is often discussed that many patients receive irrational prescriptions, which either do not provide any benefit to the patients or actually harm them. Accordingly, understanding the prescriptions can partly provide us information about the type of care received by patients.

There is ample research on the psychotropic drug prescriptions in the West. These studies have evaluated the national prescription patterns[2,3] and have additionally looked at the prescription patterns in general practice,[4,5] specialist care,[4] emergency services,[6] and extreme of ages.[7,8] Studies have also looked at the prescription patterns specific to various psychiatric disorders such as depression,[9] bipolar disorder,[10] and psychosis.[11] Data are also available in the form of prescription patterns for antidepressants, mood stabilizers[12] and antipsychotics in patients with mental disorders.[13,14,15,16,17] Some of the authors have also looked at the influence of demographic factors like gender on the prescription patterns.[18]

In recent times, many studies have evaluated the prescription patterns in various Asian countries too, in which data from a few centers in India has also been included.[19,20,21,22,23] Some of the studies from India have also evaluated the prescription patterns of patients with various psychiatric disorders, but these studies have included small number of patients and have been mostly limited to one center only.[24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] It is often difficult to compare these studies because of the different time frames in which these were conducted. In recent times, a study was published with a large sample size covering patients with different diagnoses, but this study too included patients from one center only.[30] Only one multicentric study has evaluated the prescription patterns, but it limited itself to use of antidepressants in patients with depression. This study was conducted under the aegis of Indian Psychiatric Society (IPS), and it showed escitalopram was the most commonly prescribed antidepressant, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were the most commonly prescribed class of antidepressants. Polypharmacy in the form of use of combination of two antidepressants in the same patient was infrequent and benzodiazepines were used as a co-prescription in a significantly higher proportion of patients.[33] Most studies from India do not provide data with regard to the dosages used.

In this background, this multicentric study funded by the IPS aimed to assess the first prescription handed over to the psychiatrically ill patients on their contact with a psychiatrist.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was funded by the IPS. The study was approved by the IPS Ethical Review Board and/or by the Local Institutional Ethics Committees. Patients were recruited after obtaining informed consent. Initially, 22 centers showed their willingness to participate, but finally 11 centers participated. Of the centers which participated, maximum numbers of sites were from North India (Chandigarh, Ludhiana, Mullana, Rohtak, and Udaipur) and there were 2 centers each from central India (Agra and Lucknow) and Western India (Ahmedabad and Vadodara). There was one center each from Eastern part of India (Guwahati) and Southern India (Chennai). Among the participating centers, 1 center was in the centrally funded Institute (Chandigarh), 5 centers were in the state Government run medical colleges (Agra, Ahmadabad, Guwahati, Lucknow and Rohtak), 4 centers were in privately run medical colleges (Chennai, Mullana, Udaipur and Vadodara) and 1 privately run clinic (Ludhiana).

This study followed a cross-sectional design and the prescriptions handed over to the patients were assessed only once at the time of intake into the study. The sample comprised of consecutive patients attending the psychiatric services. The inclusion criteria for the study was age more than equal to 15 years and the patient must have fulfilled the criteria of one of the mental disorders as per ICD-10, assessed by using Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview.[34] Current level of functioning was assessed on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)[35] scale.

All patients fulfilling the selection criteria were approached and explained about the purpose of the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients or their primary caregivers before they were included in the study.

Descriptive analysis was carried out using mean and standard deviation with range for continuous variables and frequency and percentages for ordinal or nominal variables.

RESULTS

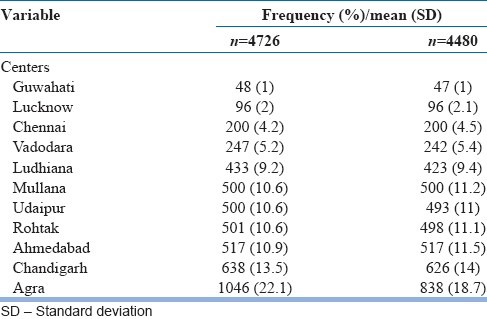

Table 1 shows the distribution of patients across different centers. Highest numbers of patients were from the center at Agra followed by Chandigarh. Least number of patients were from Guwahati. Initially, data of 4726 patients was received from various centers. After thorough evaluation of the data, 4480 patients were taken up for analysis. The main reason for exclusion of cases was having included patients with only neurological disorders (for example, epilepsy).

Table 1.

Distribution of patients across different centers

Demographic profile

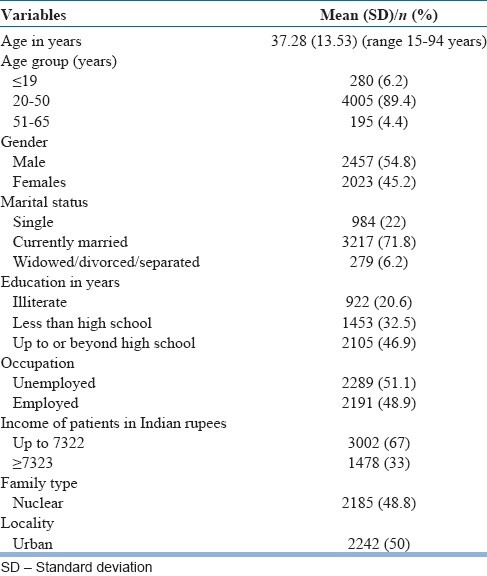

As shown in Table 2, Majority (89.4%) of the patients were in the age range of 20-65 years with a mean age of the study sample being 37.28 (SD: 13.53) years. There was nearly equal distribution of patients of either gender, those from nuclear versus nonnuclear families, employed versus unemployed and urban versus rural locality. About two-third of the patients had family income of less than Indian rupees 7322 and 71.8% were married.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic profile of study sample (n=4480)

Diagnostic distribution

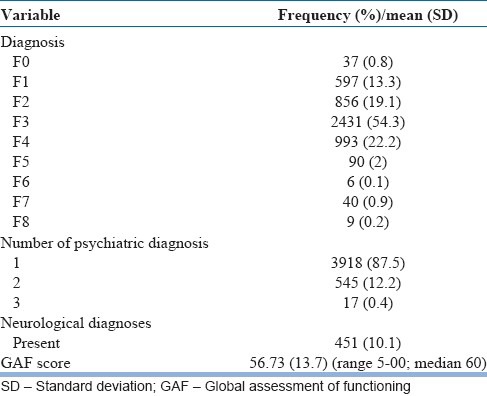

As shown in Table 3, more than half of the study sample had the diagnosis of affective disorder, majority being of unipolar depressive disorders (N = 1957) and remaining having a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (N = 474). Nearly one-fifth of patients had diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, with schizophrenia (N = 592) being the most common diagnosis in this category followed by Unspecified nonorganic psychosis (N = 81), Acute and transient psychosis (N = 74), schizoaffective disorder (N = 39) and persistent delusional disorder (N = 33). Other psychotic diagnoses formed a very small group. Another one-fifth of the patients had Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders, with other anxiety disorders (N = 425) being the most common followed by obsessive compulsive disorder (N = 240). Other small groups of Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders included dissociative disorders (N = 84), phobic anxiety disorder (N = 54), Reaction to severe stress, adjustment disorders (N = 44) and other neurotic disorders (N = 22).

Table 3.

Diagnostic distribution of the study sample

Most of the patients (87.5%) were assigned one psychiatric diagnosis; a few patients (12.2%) had 2 diagnoses, while only occasional patients (0.4%) were diagnosed to have three psychiatric disorders. About one-tenth (N = 451; 10.1%) had comorbid neurological diagnosis, comorbid physical illness related to cardiovascular system (i.e. hypertension) was assigned to 4.1% patients (N = 201) and very few patients (N = 98; 2.2%) were diagnosed to have an endocrine disorder (i.e. diabetes mellitus or hypothyroidism).

The mean GAF scale score for the study sample was 56.73.

Prescription patterns

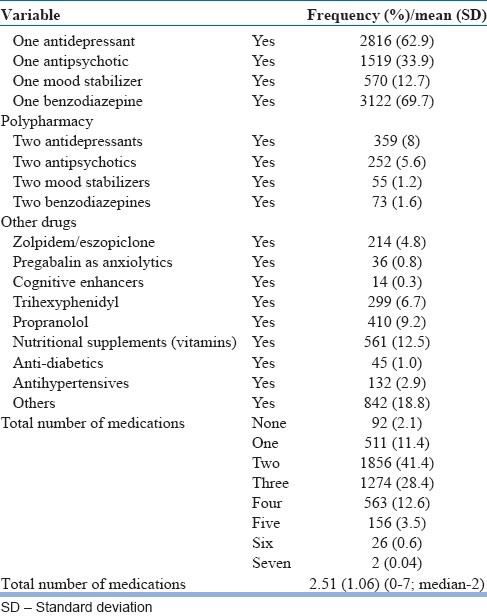

Among the various psychotropics, benzodiazepines were the most commonly prescribed medications. This was followed by antidepressants and antipsychotics. About one-eighth of the patients were prescribed one of the classical mood stabilizers (i.e. lithium carbonate, valproate, carbamazepine, ox-carbamazepine, and lamotrigine). Other details are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Prescription patterns of the study sample

In terms of diagnostic groups, 95.5% of patients with unipolar depression were prescribed one antidepressant, 95.1% of patients with psychosis were prescribed at least one antipsychotic medication, 78.7% of bipolar patients received one antipsychotic medication, and 74.7% of bipolar patients received one of the mood stabilizers. In terms of polypharmacy, that is., prescription of more than one medication from the same group (example, two antidepressants), highest level of polypharmacy was seen for antidepressants (8%), followed by antipsychotics (5.6%).

About 5% of subjects also received zolpidem. Very few patients were prescribed pregabalin as anxiolytic (0.8%) and still fewer (0.3%) were on various cognitive enhancers. The mean number of medications prescribed for a patient was 2.51. Two-fifth (41.4%) patients were prescribed two medications. In addition, nearly one-fifth of the prescriptions included medications other than psychotropics, in the form of nutritional supplements, trihexyphenidyl, propranolol, antidiabetic and antihypertensive medications.

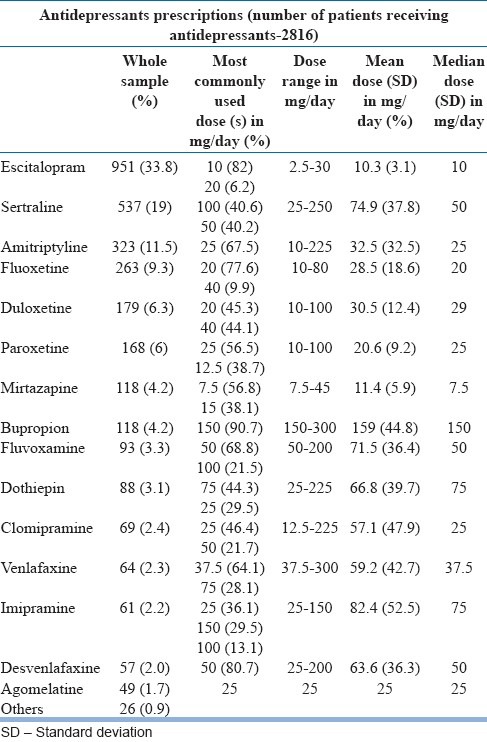

Antidepressants prescriptions

As is evident from Table 5, escitalopram was the most commonly prescribed antidepressant, followed by sertraline and amitriptyline. In total, Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) formed 71.4% of the total prescriptions. One-fifth (19.2%) of the antidepressant prescriptions were those of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (Amitriptyline, imipramine, Clomipramine, and dothiepin). Details of the mean and median doses along with most commonly used doses for each antidepressant are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Prescription pattern for antidepressants

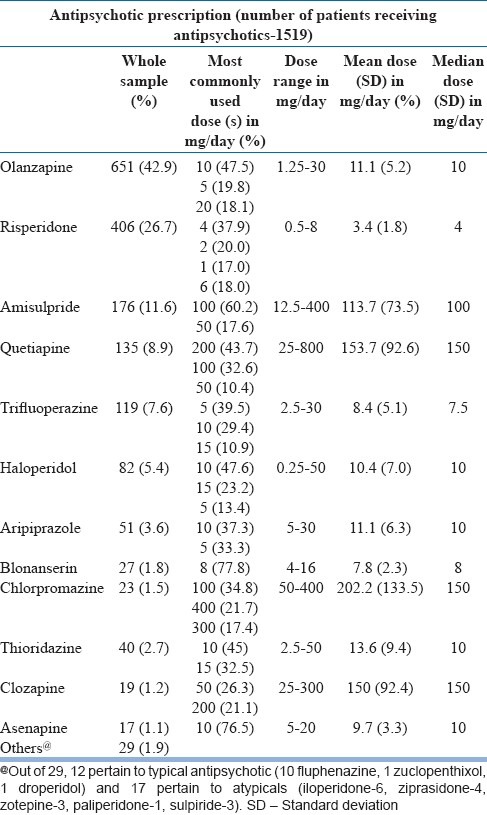

Antipsychotic prescriptions

Among the antipsychotics, olanzapine (42.9%) was the most commonly prescribed antipsychotic medication, followed by risperidone (26.7%) and amisulpride (11.6%). About one-sixth (18%) of the prescriptions included a typical antipsychotics. Details of the mean and median doses along with most commonly used doses for each antipsychotic are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Prescription pattern for antipsychotics

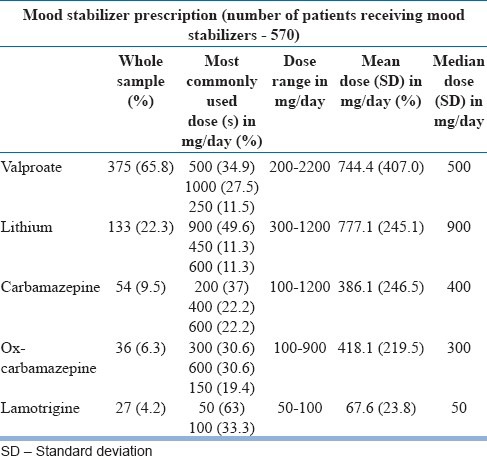

Mood stabilizer prescriptions

Among the patients prescribed mood stabilizers, about two-third (65.8%) were prescribed valproate, and 22.3% were prescribed lithium. The other details of prescriptions are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Prescription pattern for mood stabilizers

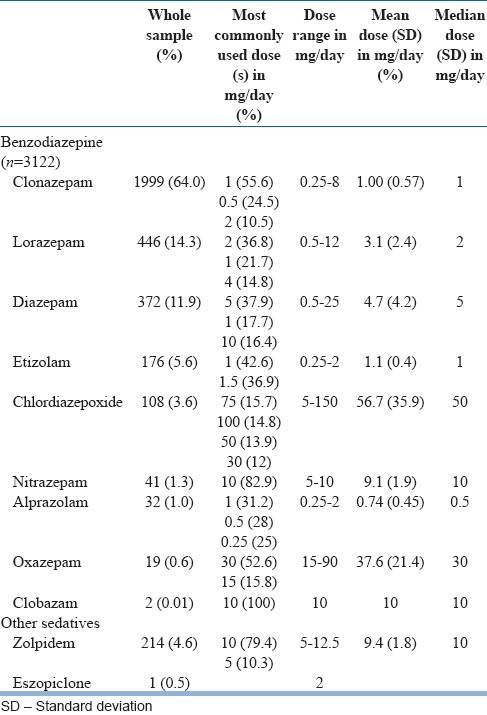

Benzodiazepine prescriptions

Among the benzodiazepines, clonazepam formed 64% of all the benzodiazepine prescriptions, and it was followed by lorazepam and diazepam. Zolpidem was prescribed in only 4.6% of cases. Details of doses are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Prescription pattern for benzodiazepines and other sedatives

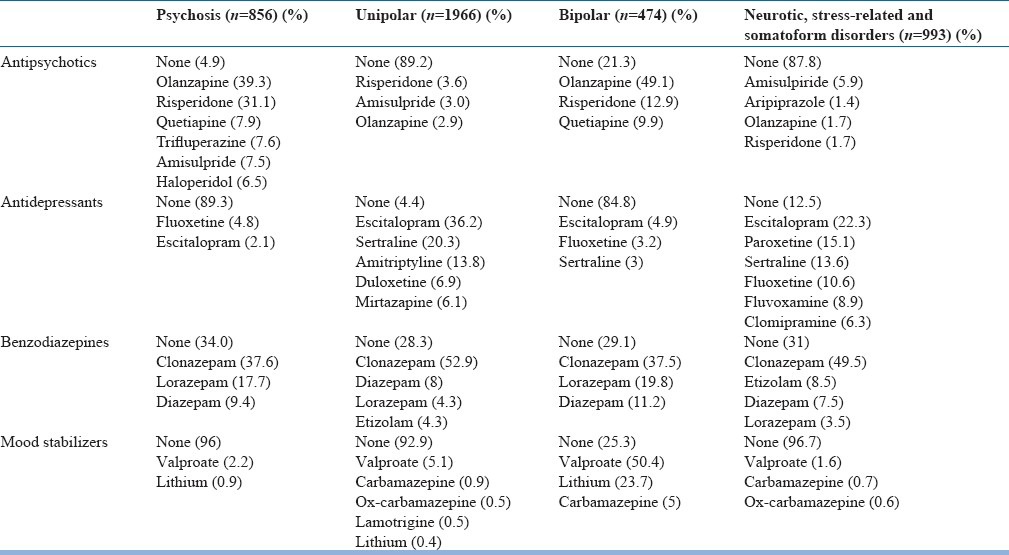

Prescriptions as per the diagnostic groups

As shown in Table 9, olanzapine was the most commonly prescribed antipsychotic followed by risperidone in patients with psychosis and bipolar disorder. Risperidone was the most common antipsychotic in the unipolar affective disorders and amisulpride was the most common antipsychotic in the anxiety disorder group. However, it is important to note that most of the patients with unipolar affective disorders and anxiety disorders were not on any antipsychotic medications. Escitalopram was the most commonly prescribed antidepressant in patients with affective disorders and anxiety disorders. However, in patients with psychosis, fluoxetine was prescribed more commonly than escitalopram. As is evident from Table 9, two-third of patients with psychotic disorder were prescribed benzodiazepines and about 70% of patients with affective disorders and anxiety disorders were prescribed benzodiazepine. In all the diagnostic groups, clonazepam was the most commonly prescribed benzodiazepine, with about half of the patients with unipolar affective disorders and anxiety disorders receiving clonazepam.

Table 9.

Prescription pattern as per diagnostic categories

In terms of diagnosis and polypharmacy, the rate of antidepressant polypharmacy in unipolar depression group was 13.64%, 0.63% in bipolar depression, 10% in Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders and 0.35% of patients with psychotic disorders received more than one antidepressant. In terms of antipsychotic polypharmacy, 20.9% of patients with psychotic disorders received more than one antipsychotic medications, and the antipsychotic polypharmacy rate was 0.61% for unipolar depression, 12.65% for bipolar depression and 0.4% for Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders. Mood stabilizer polypharmacy in bipolar depression was 10.33%, in unipolar depression was 0.11%, in anxiety disorders was 0.2% and that for psychotic disorders was 0.1%. Benzodiazepine polypharmacy in unipolar depression group was 1%, in bipolar depression was 0.6%, in anxiety disorders were 1.3% and that for psychotic disorders was 1.1%.

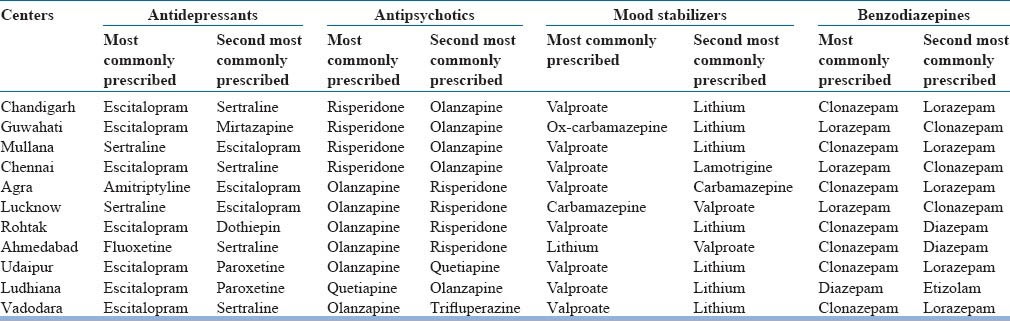

Differences across the participating centers

For various major medications, few differences were seen across different treatment centers as shown in Table 10. Among the antidepressants, escitalopram was the most common antidepressant across 7 out of 11 centers and second most common in 3 centers. In terms of antipsychotics, olanzapine was the most commonly prescribed antipsychotic across 6 out of 11 centers and second most common across rest of the centers. Among mood stabilizers, valproate was more often prescribed in 8 out of 11 centers and in terms of benzodiazepines, clonazepam was the most common benzodiazepine prescribed in 6 out of the 11 centers.

Table 10.

Most commonly prescribed medications across different centers

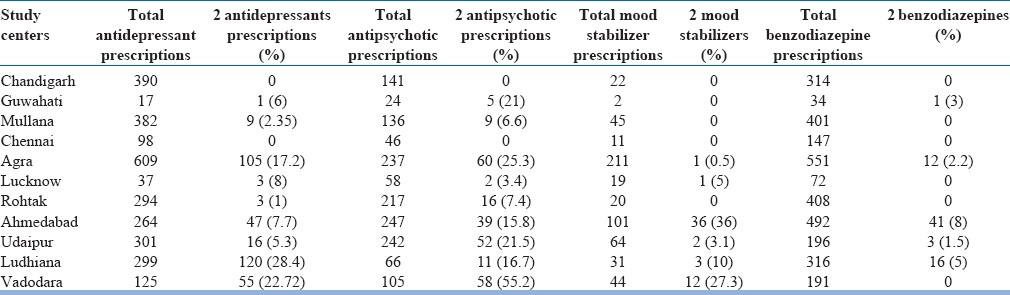

In terms of polypharmacy, there were significant differences across various centers. For antidepressants, polypharmacy varied from 0% to 28.4%. Polypharmacy for antipsychotics was more common with the prevalence varying from 0% to 55.2%. Polypharmacy for mood stabilizers varied from 0% to 27.3% and for benzodiazepines varied from 0% to 8%. Details of polypharmacy across various centers are shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Poly pharmacy across different centers

DISCUSSION

This is the first multicentric study from India, which has attempted to evaluate the prescription pattern of various psychotropic agents across multiple diagnostic groups. This study included 4480 patients aged 15 or more years spread across 11 centers in India. The main focus of the study was prescriptions given to consecutive patients contacting the specific mental health services for the first time, irrespective of their past treatment history.

Certain important findings emerge from this study. This study shows that the escitalopram is the most commonly prescribed antidepressant, followed by sertraline and amitriptyline. As a class, SSRIs made up more than two-third of all antidepressant prescriptions. Overall TCAs formed a very small proportion of prescriptions of antidepressants. SNRIs formed 10% of total prescriptions of antidepressants. When we compare these findings with other studies from India, findings concur with some of the studies,[33] but differ from that reported from other centers[29] and from those reported more than a decade ago.[28] When we compare the findings of this study with reports from the West, certain similarities are again noted. A multicountry study from Europe, which evaluated the prescription of antidepressants to patients with first episode depression or those suffering from recurrent depressive disorder and requiring an antidepressant for a new episode reported that about two-third (63.3%) of patients were prescribed an SSRI, whereas SNRI formed 13.6% of the total antidepressant prescriptions.[2] A multicountry survey from Asia also reported that together SSRIs and SNRIs form 77% of all antidepressant prescriptions.[36]

In this study, TCAs formed one-sixth (16.8%) of the total prescriptions, with amitriptyline being the most commonly prescribed antidepressant from this class. Thus, TCAs are still considered an important option in the management of depression and this finding is similar to the findings noted by Grover et al.[33] in their study from Chandigarh. However, when compared with older studies[28] over the years there is a reduction in the prescriptions of TCAs.

In various diagnostic groups, escitalopram again emerged as the most commonly prescribed antidepressant medication in patients with unipolar depression, in patients with bipolar disorder and those with Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders and it emerged as the second most commonly prescribed antidepressant in those with psychotic disorders. These findings suggest that, probably diagnosis is not the only factor that influences the choice of antidepressants, and there could be many other factors such as clinicians’ experience, patient profile, side-effect profile of medication, etc., that influence the choice of antidepressants. However, these factors were not evaluated in this study.

In this study, very few patients (10.7%) with psychotic disorders received concurrent antidepressants. There is wide variation in the concomitant antidepressant prescription in patients with schizophrenia as reported in the literature. Some of the studies from Asian countries report similar prescription rates for antidepressants in patients with schizophrenia as seen in this study.[20] However, a study from Malaysia reported that majority of patients with schizophrenia received antidepressants.[37] The rate of antidepressant prescriptions in this study are much lower than that reported in the studies from West, which reported antidepressant prescription rates of 37.4-40% in patients with schizophrenia.[38,39] It is important to note that the lower antidepressant prescription rate in patients of schizophrenia could have been influenced by the fact that the present study focused only on the first prescriptions. It is quite likely that most patients with psychotic disorders might have presented in the acute psychotic phase, when clinicians would prefer to use antipsychotics only. Other reason for lower rate of antidepressant prescriptions in patients with psychosis in the present study could be the recent evidence that suggests that some of the atypical antipsychotics also influence mood.[40] In the present study, the rate of atypical antipsychotic prescription was high.

About 15% of patients with bipolar disorders were prescribed antidepressant medications. This prescription rate of antidepressants in patients with bipolar disorder is similar to that reported in previous studies from India.[30,41] The commonly prescribed antidepressants in bipolar disorder group in this study included escitalopram, fluoxetine and sertraline, which is also very akin to the previous study, which also reported escitalopram and sertraline to be the commonly prescribed antidepressants in patients with bipolar disorder.[30] However, this rate of antidepressant prescription in patients with bipolar disorder is much less than that reported from some of the Western countries.[42] The lower prescription of antidepressants in this group could be a reflection of concern for manic/hypomanic switch.

In psychotic patients, olanzapine was the most commonly prescribed antipsychotic medication, followed by risperidone, amisulpride, and quetiapine. Typical antipsychotics formed about 18% of all antipsychotic prescriptions, and the rest were all atypical antipsychotics. This prescription pattern is very similar to that reported in previous studies from India[29,30] as well as in the survey conducted on Indian psychiatrists.[43] When we compare the findings with those reported from Western countries and other countries from Asia, certain similarities are evident. Recent studies from various part of the world suggest increase in the prescription of atypical antipsychotics contributing to about 76.9-77.2% of all antipsychotic prescriptions.[44,45] However, a study from Malaysia reported haloperidol to be the most commonly used oral antipsychotic medication and atypical antipsychotics formed only 32% of all the prescriptions.[37] All these findings suggest that many factors like availability of particular medications in a country, availability in the dispensary, cost, etc., could influence the prescription patterns, and there is a need to evaluate the role of these factors.

Nearly 75% received monotherapy (i.e. only one antipsychotic medication), 20.9% patients received more than one antipsychotic medications, and 4.9% did not receive any antipsychotic. This rate of monotherapy, nonprescription of antipsychotics and polypharmacy in patients with psychosis is comparable to that reported from other countries.[37,45,46,47] The proportion of patients receiving antipsychotic polypharmacy in this study was much less than 51.6%, reported in a multicountry study from Asia.[48] It is important to note that the study by Xiang et al.[48] focused on inpatients whereas the present study evaluated the prescriptions at the first contact. A study from Finland assessed antipsychotic polypharmacy in outpatients with diagnosis of schizophrenia and reported that 46.2% of patients received polypharmacy; however, it is important to note that the study defined polypharmacy as concurrent use of 2 antipsychotics for the duration of at least 2 months.[49]

About 10% of patients with unipolar depression received antipsychotics. Risperidone, amisulpride and olanzapine were the most commonly prescribed antipsychotics in this diagnostic group. This antipsychotic prescription rate in unipolar depression group is about half than that reported in some of the studies from the West,[50] but is similar to the 8.6% prescription rate of second generation antipsychotics in patients with nonpsychotic depression.[51] When we compared the antipsychotic prescription rate in patients of unipolar depression with previous studies from India, the rates were slightly higher than one of the earlier studies (6% vs. 10% in the current study),[33] but less than that reported in other studies.[28] These variations could be attributed to the differences in the clinical profile of the patients studied.

More than three-fourth of the patients with bipolar disorder received antipsychotics; olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine being the most commonly prescribed antipsychotic in this diagnostic group. This rate is much higher than that reported in previous studies from other countries[12,52] and India.[30] However, the preference of atypical antipsychotics in this group is similar to the findings from other countries[52] and is possibly a reflection of the emerging evidence that atypical antipsychotic also have mood stabilizing properties.[40]

About one-eighth of the patients with Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders received antipsychotics; amisulpride, aripiprazole, olanzapine, and risperidone were the most commonly prescribed antipsychotics in this diagnostic group. The rate of antipsychotic prescription in patients with Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders is much higher than that reported in a previous study from India,[30] but lower than that reported in a study from the west in which antipsychotic prescription rates in patients with anxiety disorders was 10.6% during the years 1996-1999 and it increased to 21.3% during the years 2004-2007.[53]

In the present study, nearly three-fourth of the patients with bipolar disorder were prescribed one of the classical mood stabilizers, with valproate being prescribed much more than other mood stabilizers. Existing literature is somewhat contradictory with respect to mood stabilizer prescriptions in patients with bipolar disorder with some studies reporting 72-82% the prescription rate of classical mood stabilizers in bipolar patients.[12,52,54] Other studies have reported the mood stabilizer prescription rates in the range of 50%.[12,55] Many studies from the West have reported more use of lithium compared to valproate contrary to the findings of the present study.[42,55,56] Conversely, preference for valproate over lithium is also supported by some of the studies[12] and also by the data, which suggests that over the years valproate is increasingly preferred compared to lithium.[57] Earlier studies from India too suggest contradictory trends; one study reported higher use of valproate,[30] while the other reported preference for lithium.[41] These differences could be due to different samples studied i.e., one study focused on follow-up patients[41] and the other evaluated the first prescription of patients.[30] Higher preference of valproate in the first prescriptions of patients with bipolar disorder could be due to the evidence for higher efficacy of valproate in treatment of acute mania.[58] Other reasons of preference for valproate could be the ease in increasing its doses, and relatively lesser number of investigations required both prior to starting of valproate and thereafter.

Very few patients (4%) in this study with psychotic disorders received concurrent mood stabilizers studies for various other countries suggest that. 3.3-18% of patients with schizophrenia receive mood stabilizers.[45] Prescription of mood stabilizers was found in 20.4% of patients with schizophrenia admitted to inpatient units in various countries of Asia.[59] The mood stabilizer prescription rate in patients with psychosis as noted in this study is higher than that reported by a previous study from India.[30] It is difficult to account for such differences in the absence of the study of factors determining the drug-prescription.

In the unipolar depression (7%) and Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (3.3%) groups although few patients received mood stabilizers yet this prescription rate was significantly higher than that reported by Grover et al.[30] As discussed earlier, these higher prescription rates could be due to variation in prescription patterns across different study centers.

More than two-third of patients with any of the diagnostic group were prescribed a benzodiazepine, with clonazepam being the most commonly prescribed agent in all the diagnostic groups. Lorazepam was the second most commonly prescribed benzodiazepine in the psychotic and bipolar disorder group; diazepam was the second most commonly prescribed benzodiazepine in the unipolar depression group; etizolam was the second most commonly prescribed benzodiazepine in the Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders group. These benzodiazepine prescription rates are similar to those of the earlier study from a center in north India,[30] but are less than that reported for depression and bipolar disorder in studies from Lucknow.[29,41] The benzodiazepine prescription rates across different disorders observed in this study was much higher than that reported in studies from the West.[12,42,56,60,61]

When one looks at the doses of various medications, it is evident that lower doses are more preferred by the psychiatrists in India for most of the antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers and benzodiazepines. The commonly used doses for most of the psychotropics in majority of the patients are in the usual recommended doses as given in the various treatment guidelines.[62,63] This is contradictory to many studies from the West, which report use of megadoses of various medications in some of the patients.[64] When we compare the doses with that reported in the survey of psychiatrists from India, the doses in this study were on the lower side.[43] A possible reason for the same could be that in the present study we had evaluated the first prescription only. A study from the Asian countries reported that about 18% of patient with schizophrenia were prescribed high doses of antipsychotic (i.e. more than 1000 mg/day of chlorpromazine equivalent).[65] The proportion of patients receiving doses of antipsychotics on the higher side was much lower in the present study. Rate of antidepressant polypharmacy (i.e. concurrent use of two antidepressants) in the index study was 8% for the whole study sample, this is about half the rate reported in the previous IPS multicentric study which looked at the prescription of antidepressants in patients with depression.[30] Antidepressant polypharmacy in patients with depression in the present study was comparable with that in the previously reported study.[30]

The rate of antidepressant monotherapy in this study is significantly higher than that reported in a study from Japan;[66] however, it is important to note that the study from Japan followed a longitudinal study design and the patients were evaluated over a period of time. It is quite possible that while carrying out the longitudinal assessments, it becomes more evident that certain patients do not respond to a particular antidepressant and resultantly require combination/augmentation with another agent.

In terms of antipsychotic polypharmacy, one-fifth of patients with psychotic disorders received more than one antipsychotic medication concurrently, and the antipsychotic polypharmacy rate was 0.61% for unipolar depression, 12.65% for bipolar depression and 0.4% for Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders. These rates are much higher than that reported in a previous study from India for all the diagnostic groups[30] and that reporting prescription patterns in patients with bipolar disorder.[41] The overall rate of use of antipsychotic combinations across different age groups in this study was less than that reported in some of the studies from the West.[67,68] Mood stabilizer polypharmacy in patients with bipolar disorder was 10.33%, less than that reported in studies from the west.[69]

In terms of variation across different centers, escitalopram emerged as the most commonly used antidepressant in 7 out of the 11 participating centers and was ranked as the second most commonly used antidepressant in other 3 centers. Therefore, it can be concluded that the results of the present study were not influenced by the prescription patterns of one particular center alone. Of the 11 centers, olanzapine and risperidone emerged in 8 centers as the two most commonly prescribed antipsychotics. In other 3 centers, again olanzapine was among the two most commonly used antipsychotic. For mood stabilizers, valproate emerged as the most commonly prescribed mood stabilizer across 8 different centers and second most commonly prescribed mood stabilizer in 2 out the remaining 3 centers. This suggests a preference of valproate over other mood stabilizers in management of acute symptoms of bipolar disorder. Clonazepam emerged as the most commonly prescribed benzodiazepine across 7 of the 11 centers and second most commonly prescribed benzodiazepine in 3 out of the remaining 4 centers. However, there were certain differences in the rate of polypharmacy across different treatment centers, with some centers virtually reporting no same class polypharmacy.

This study has many limitations. The study was limited to assessment of the first prescription handed over to the patients, and this does not reflect the prescriptions received by patients in various stages of their illness. The study was also limited by the cross-sectional assessment and was not able to provide information about the duration of prescriptions. Further, the study did not evaluate the relationship of prescriptions with particular symptoms per se and was limited to the presence or absence of a particular diagnosis. The study also did not focus on assessment of side-effects experienced by the patients, nor did it evaluate the factors associated with the prescriber which can influence the prescription patterns. This study also does not provide information about the tolerability of various doses used and cannot be generalized to inpatients, who are often more severely ill and require higher doses of medications. The study also did not look at the relationship of prescription patterns and drugs available free of cost in the dispensary of the hospital. Study did not evaluate the nonpharmacological treatments advised to the patients. Similarly, although the study focused on first prescriptions, it must be understood that all the patients were not necessarily seeking treatment for the first time or were drug-naïve. It is quite possible that a proportion of patients would have been on treatment prior to contacting the particular study site. Future studies must attempt to overcome these limitations. In future multicentric studies must evaluate the relationship of prescriptions with various clinical parameters such as age of onset, duration of symptoms, past history of treatment and type of symptoms, past history of side-effects, etc., In addition, the studies must attempt to evaluate the prescriptions over a period of time to study the duration of use of each medication, and the side-effects experienced, in order to reach a better conclusion in terms of polypharmacy and particularly the use of drugs like benzodiazepines.

CONCLUSION

This study suggests that there is little difference in prescription patterns of various psychotropics across different treatment centers, irrespective of the treatment setting, that is., central institute, government medical college or private practice, except for the prevalence of polypharmacy. Escitalopram and sertraline are the most commonly prescribed antidepressants. Olanzapine and risperidone are the most commonly prescribed antipsychotics, valproate and lithium are the most commonly prescribed mood stabilizers and clonazepam and lorazepam are the most commonly prescribed benzodiazepines. Overall the rate of polypharmacy is low.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was funded by Indian Psychiatric Society (Funded amount- 1.2 lakhs)

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. Introduction to drug utilization research. 2003. [Last accessed on 2013 December 16]. Available from: http://www.WHO.int.061130 .

- 2.Bauer M, Monz BU, Montejo AL, Quail D, Dantchev N, Demyttenaere K, et al. Prescribing patterns of antidepressants in Europe: Results from the Factors Influencing Depression Endpoints Research (FINDER) study. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Priest RG, Guilleminault C. Psychotropic medication consumption patterns in the UK general population. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:273–83. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00238-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kjosavik SR, Hunskaar S, Aarsland D, Ruths S. Initial prescription of antipsychotics and antidepressants in general practice and specialist care in Norway. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123:459–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Rijswijk E, Borghuis M, van de Lisdonk E, Zitman F, van Weel C. Treatment of mental health problems in general practice: A survey of psychotropics prescribed and other treatments provided. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;45:23–9. doi: 10.5414/cpp45023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ernst CL, Bird SA, Goldberg JF, Ghaemi SN. The prescription of psychotropic medications for patients discharged from a psychiatric emergency service. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:720–6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnell K, Fastbom J. Comparison of prescription drug use between community-dwelling and institutionalized elderly in Sweden. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:751–8. doi: 10.1007/s40266-012-0002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas CP, Conrad P, Casler R, Goodman E. Trends in the use of psychotropic medications among adolescents, 1994 to 2001. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:63–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfeiffer PN, Szymanski BR, Valenstein M, McCarthy JF, Zivin K. Trends in antidepressant prescribing for new episodes of depression and implications for health system quality measures. Med Care. 2012;50:86–90. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182294a3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grande I, de Arce R, Jiménez-Arriero MÁ, Lorenzo FG, Valverde JI, Balanzá-Martínez V, et al. Patterns of pharmacological maintenance treatment in a community mental health services bipolar disorder cohort study (SIN-DEPRES) Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:513–23. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiivet RA, Llerena A, Dahl ML, Rootslane L, Sánchez Vega J, Eklundh T, et al. Patterns of drug treatment of schizophrenic patients in Estonia, Spain and Sweden. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;40:467–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb05791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldessarini RJ, Leahy L, Arcona S, Gause D, Zhang W, Hennen J. Patterns of psychotropic drug prescription for U.S. patients with diagnoses of bipolar disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:85–91. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sproule BA, Lake J, Mamo DC, Uchida H, Mulsant BH. Are antipsychotic prescribing patterns different in older and younger adults? a survey of 1357 psychiatric inpatients in Toronto. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55:248–54. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerhard T, Akincigil A, Correll CU, Foglio NJ, Crystal S, Olfson M. National trends in second-generation antipsychotic augmentation for nonpsychotic depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:490–7. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermes ED, Sernyak M, Rosenheck R. Use of second-generation antipsychotic agents for sleep and sedation: A provider survey. Sleep. 2013;36:597–600. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weintraub D, Chen P, Ignacio RV, Mamikonyan E, Kales HC. Patterns and trends in antipsychotic prescribing for Parkinson disease psychosis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:899–904. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroken RA, Mellesdal LS, Wentzel-Larsen T, Jørgensen HA, Johnsen E. Time-dependent effect analysis of antipsychotic treatment in a naturalistic cohort study of patients with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27:489–95. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith S. Gender differences in antipsychotic prescribing. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22:472–84. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2010.515965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiang YT, Li Y, Correll CU, Ungvari GS, Chiu HF, Lai KY, et al. Common use of high doses of antipsychotic medications in older Asian patients with schizophrenia (2001-2009) Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:359–66. doi: 10.1002/gps.4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiang YT, Ungvari GS, Wang CY, Si TM, Lee EH, Chiu HF, et al. Adjunctive antidepressant prescriptions for hospitalized patients with schizophrenia in Asia (2001-2009) Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2013;5:E81–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-5872.2012.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakao M, Takeuchi T, Yano E. Prescription of benzodiazepines and antidepressants to outpatients attending a Japanese university hospital. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;45:30–5. doi: 10.5414/cpp45030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiang YT, Wang CY, Si TM, Lee EH, He YL, Ungvari GS, et al. Use of anticholinergic drugs in patients with schizophrenia in Asia from 2001 to 2009. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44:114–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan CH, Shinfuku N, Sim K. Psychotropic prescription practices in east Asia: Looking back and peering ahead. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21:645–50. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32830e6dc4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khanna R, Bhandari SN, Das A. Survey of psychotropic drug prescribing pattern for long stay patients. Indian J Psychiatry. 1990;32:162–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padmini DD, Amarjeeth R, Sushma M, Guido S. Prescription patterns of psychotropic drugs in hospitalized schizophrenic patients in a tertiary care hospital. Calicut Med J. 2007;5:e3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sawhney V, Chopra V, Kapoor B, Thappa JR, Tandon VR. Prescription trends in schizophrenia and manic depressive psychosis. J K Sci. 2005;7:156–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trivedi JK, Dhyani M, Yadav VS, Rai SB. Anti-psychotic drug prescription pattern for schizophrenia: Observation from a general hospital psychiatry unit. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:279. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.70996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chakrabarti S, Kulhara P. Patterns of antidepressant prescriptions: L acute phase treatments. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:21–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trivedi JK, Dhyani M, Sareen H, Yadav VS, Rai SB. Anti-depressant drug prescription pattern for depression at a tertiary health care center of Northern India. Med Pract Rev. 2010;1:16–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grover S, Kumar V, Avasthi A, Kulhara P. An audit of first prescription of new patients attending a psychiatry walk-in-clinic in north India. Indian J Pharmacol. 2012;44:319–25. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.96302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarkar P, Chakraborty K, Misra A, Shukla R, Swain SP. Pattern of psychotropic prescription in a tertiary care center: A critical analysis. Indian J Pharmacol. 2013;45:270–3. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.111947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grover S, Kumar V, Avasthi A, Kulhara P. First prescription of new elderly patients attending the psychiatry outpatient of a tertiary care institute in North India. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012;12:284–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grover S, Avasth A, Kalita K, Dalal PK, Rao GP, Chadda RK, et al. IPS multicentric study: Antidepressant prescription patterns. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:41–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall RC. Global Assessment of Functioning. A modified scale. Psychosomatics. 1995;36:267–75. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(95)71666-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uchida N, Chong MY, Tan CH, Nagai H, Tanaka M, Lee MS, et al. International study on antidepressant prescription pattern at 20 teaching hospitals and major psychiatric institutions in East Asia: Analysis of 1898 cases from China, Japan, Korea, Singapore and Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61:522–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ponto T, Ismail NI, Abdul Majeed AB, Marmaya NH, Zakaria ZA. A prospective study on the pattern of medication use for schizophrenia in the outpatient pharmacy department, Hospital Tengku Ampuan Rahimah, Selangor, Malaysia. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2010;32:427–32. doi: 10.1358/mf.2010.32.6.1477907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Himelhoch S, Slade E, Kreyenbuhl J, Medoff D, Brown C, Dixon L. Antidepressant prescribing patterns among VA patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;136:32–5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lako IM, Taxis K, Bruggeman R, Knegtering H, Burger H, Wiersma D, et al. The course of depressive symptoms and prescribing patterns of antidepressants in schizophrenia in a one-year follow-up study. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27:240–4. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh J, Chen G, Canuso CM. Antipsychotics in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2012;40:187–212. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-25761-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trivedi JK, Sareen H, Yadav VS, Rai SB. Prescription pattern of mood stabilizers for bipolar disorder at a tertiary health care centre in north India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:131–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.111449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghaemi SN, Hsu DJ, Thase ME, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Miyahara S, et al. Pharmacological treatment patterns at study entry for the first 500 STEP-BD participants. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:660–5. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.5.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grover S, Avasthi A. Anti-psychotic prescription pattern: A preliminary survey of psychiatrists in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:257–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.70982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu CS, Lin YJ, Feng J. Trends in treatment of newly treated schizophrenia-spectrum disorder patients in Taiwan from 1999 to 2006. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:989–96. doi: 10.1002/pds.3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.An FR, Xiang YT, Wang CY, Zhang GP, Chiu HF, Chan SS, et al. Change of psychotropic drug prescription for schizophrenia in a psychiatric institution in Beijing, China between 1999 and 2008. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;48:270–4. doi: 10.5414/cpp48270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gören JL, Meterko M, Williams S, Young GJ, Baker E, Chou CH, et al. Antipsychotic prescribing pathways, polypharmacy, and clozapine use in treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:527–33. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.002022012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernardo M, Coma A, Ibáñez C, Zara C, Bari JM, Serrano-Blanco A. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in a regional health service: A population-based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiang YT, Dickerson F, Kreyenbuhl J, Ungvari GS, Wang CY, Si TM, et al. Common use of antipsychotic polypharmacy in older Asian patients with schizophrenia (2001-2009) J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32:809–13. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182726623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suokas JT, Suvisaari JM, Haukka J, Korhonen P, Tiihonen J. Description of long-term polypharmacy among schizophrenia outpatients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:631–8. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0586-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mohamed S, Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA. Use of antipsychotics in the treatment of major depressive disorder in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:906–12. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gerhard T, Akincigil A, Correll CU, Foglio NJ, Crystal S, Olfson M. National trends in second-generation antipsychotic augmentation for nonpsychotic depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:490–7. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nuss P, de Carvalho W, Blin P, Arnaud R, Filipovics A, Loze JY, et al. Treatment practices in the management of patients with bipolar disorder in France. The TEMPPO study. Encephale. 2012;38:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Comer JS, Mojtabai R, Olfson M. National trends in the antipsychotic treatment of psychiatric outpatients with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1057–65. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walpoth-Niederwanger M, Kemmler G, Grunze H, Weiss U, Hörtnagl C, Strauss R, et al. Treatment patterns in inpatients with bipolar disorder at a psychiatric university hospital over a 9-year period: Focus on mood stabilizers. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27:256–66. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e328356ac92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frangou S, Raymont V, Bettany D. The Maudsley bipolar disorder project. A survey of psychotropic prescribing patterns in bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4:378–85. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levine J, Chengappa KN, Brar JS, Gershon S, Yablonsky E, Stapf D, et al. Psychotropic drug prescription patterns among patients with bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2:120–30. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.020205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blanco C, Laje G, Olfson M, Marcus SC, Pincus HA. Trends in the treatment of bipolar disorder by outpatient psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1005–10. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hirschfeld RM, Baker JD, Wozniak P, Tracy K, Sommerville KW. The safety and early efficacy of oral-loaded divalproex versus standard-titration divalproex, lithium, olanzapine, and placebo in the treatment of acute mania associated with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:841–6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sim K, Yong KH, Chan YH, Tor PC, Xiang YT, Wang CY, et al. Adjunctive mood stabilizer treatment for hospitalized schizophrenia patients: Asia psychotropic prescription study (2001-2008) Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14:1157–64. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Valenstein M, Taylor KK, Austin K, Kales HC, McCarthy JF, Blow FC. Benzodiazepine use among depressed patients treated in mental health settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:654–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bingefors K, Isacson DG. Concomitant prescribing of tranquilizers and hypnotics among patients receiving antidepressant prescriptions. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:531–5. doi: 10.1345/aph.17211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, McGlashan TH, Miller AL, Perkins DO, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2 Suppl):1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision). American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4 Suppl):1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yoshio T. The trend for megadose polypharmacy in antipsychotic pharmacotherapy: A prescription survey conducted by the psychiatric clinical pharmacy research group. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2012;114:690–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sim K, Su HC, Fujii S, Yang SY, Chong MY, Ungvari G, et al. High-dose antipsychotic use in schizophrenia: A comparison between the 2001 and 2004 Research on East Asia Psychotropic Prescription (REAP) studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67:110–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Onishi Y, Hinotsu S, Furukawa TA, Kawakami K. Psychotropic prescription patterns among patients diagnosed with depressive disorder based on claims database in Japan. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33:597–605. doi: 10.1007/s40261-013-0104-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aparasu RR, Jano E, Bhatara V. Concomitant antipsychotic prescribing in US outpatient settings. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2009;5:234–41. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bret P, Bret MC, Queuille E. Prescribing patterns of antipsychotics in 13 French psychiatric hospitals. Encephale. 2009;35:129–38. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mojtabai R, Olfson M. National trends in psychotropic medication polypharmacy in office-based psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:26–36. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]