Abstract

Aim:

The aim of the current cross-sectional study was to assess oral mucosal lesions among psychiatric jail patients residing in central jail, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India.

Materials and Methods:

The study subjects consisted of prediagnosed psychiatric patients residing in central jail, Bhopal. A matched control consisting of cross section of the population, that is, jail inmates residing in the same central jail locality was also examined to compare the psychiatric subjects. The WHO oral health assessment proforma, 1997 along with 18-item questionnaire was used for the oral health examination.

Results:

A total number of subjects examined were 244, which comprised of 122 psychiatric inmates and 122 nonpsychiatric inmates. Among all psychiatric inmates, about 57.4% of inmates had a diagnosis of depression, 14.8% had psychotic disorders (like schizophrenia), and 12.3% had anxiety disorder. A total of 77% study inmates, which comprised of 87.7% psychiatrics and 66.4% nonpsychiatrics had a habit of tobacco consumption (smokeless or smoking). Overall prevalence of oral mucosal lesions among the inmates was 85 (34.8%), which comprised of 39.3% psychiatric inmates and 30.3% nonpsychiatric inmates.

Conclusion:

The information presented in this study adds to our understanding of the common oral mucosal lesions occurring in a psychiatric inmate population. Leukoplakia and oral submucous fibrosis were the most common types of oral mucosal lesions found. Efforts to increase patient awareness of the oral effects of tobacco use and to eliminate the habit are needed to improve oral and general health of the prison population.

Keywords: Dental diseases, jail inmates, oral mucosal lesions, psychiatric illness, psychiatrics

INTRODUCTION

Oral malignancies are the sixth most common cancer around the globe.[1] In South-Central Asia, 80% of head and neck cancers are found in the oral cavity and oropharynx.[2,3] Notably, oral cancer is one of the few cancers whose survival rate has not improved over 30 years, while during the past three decades a 60% increase in oral cancer in adults under the age of 40 has been documented.[4,5] Prognosis of oral cancer differs significantly between specific oral locations, with carcinoma of the lip, for example, having a much better prognosis than at the base of tongue or on the gingiva. Prognosis of intra-oral cancer is generally poor, with a 5-year survival less than 50%.[6]

Several oral lesions such as leukoplakia, erythroplakia, and lichen planus carry an increased risk for malignant transformation in the oral cavity. Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF), a potentially oral malignant condition has increased manifold, especially among the younger generation in South Asia.[7] This disease occurs most commonly in South-East Asia, but cases have been reported worldwide in countries such as Kenya, China, UK, Saudi Arabia, and other parts of the world.[8] In India, about 5 million people suffer from this disease.[9]

Oral mucosal lesions could be due to infection (bacterial, viral, and fungal), local trauma and or irritation (traumatic keratosis, irritational fibroma, and burns), systemic disease (metabolic or immunological), or related to lifestyle factors such as the usage of tobacco, areca nut, betel quid, or alcohol.[10]

For planning of national or regional oral health promotion programs as well as to prevent and treat oral health problems, baseline data about magnitude of the problem is required. India has a vast geographic area, divided into states, which differ with regard to their socioeconomic, educational, cultural and behavioral traditions.[10] These factors may affect the oral health status.

Individuals affected with mental illness are one of the neglected special groups in India where special attention is required. Dental disease and psychiatric illness are among the most prevalent health problems in the world.[11] There is some evidence that patients suffering from mental illness are more vulnerable to dental neglect and poor oral health.[12,13]

Many patients suffering from long-term psychiatric illness are on medication for long periods. These medications frequently cause xerostomia leading to an increased risk of caries, mucosal, lip, and tongue lesions,[12] gingivitis, periodontitis, and stomatitis.[11]

Mental or behavioral disorders are especially prevalent among prison populations.[14,15,16] According to Abram, Teplin, and McClelland, 6.4% male inmates and 12.2% female inmates were with severe mental disorders.[17,18]

In India, the accessibility to dental facilities for the psychiatric jail inmates is nearly nonexistent.

There are many challenges in delivering oral health services in the prison system, including service provision with respect to security procedures; recruitment and retention of dental staff and declining prison budgets with decreasing finance available for facilities, equipment and staffing pattern in addition there is currently no standardized system of assessment and prioritization of the dental needs of prisoners.[19]

There is every possible chance that this neglected group of population may have heavy stress and indulge in alcoholism, gutkha-pan chewing and other pernicious habits. These factors may cause many oral health related problems which can make their lives worse.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no data available on the oral mucosal status of this special community. Hence, the current cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the prevalence of oral mucosal lesions among psychiatric inmates residing in central jail and attempts to correlate the various risk factors with the lesions found.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and setting

A descriptive, cross-sectional survey following the STROBE-Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology[20] guidelines was conducted among the psychiatric inmates residing in central jail, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India.

Source of data

The study subjects consisted of prediagnosed psychiatric patients residing in central jail, Bhopal. A matched control consisting of cross-section of the population, that is, jail inmates residing in the same central jail locality was also examined to compare the psychiatric inmates.

Eligibility criteria

All the available prediagnosed psychiatric inmates who are approved by psychiatric professional and who are willing to participate in the survey with their consent were considered for the study.

Exclusion criteria

Subjects with serious mental illness, intellectual disability and aggressive, and uncooperative subjects, were excluded from the study due to their limited ability to cooperate.

Similarly, subjects who fail to give consent were also excluded from the study.

Sample size

A total of 244 subjects comprised of 122 psychiatric inmates and 122 nonpsychiatric inmates residing in central jail were included in the study.

Method of collection of data

Organizing the survey

Ethical approval for the survey was taken from Ethical Committee, People's Dental Academy. Permission to conduct the survey was obtained from the medical in-charge of Psychiatric Department of central jail, Bhopal.

Survey scheduling

The survey procedure was systematically scheduled and was carried out for a period of 2 weeks in the month of September 2013.

Details of the survey

All the psychiatric patients with symptoms of mental disorder, and who are approved by the psychiatrist based on criteria specified in the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, were examined for oral mucosal lesions. Prior to the examination a written consent from each participant was taken. The cross-section of the eligible subjects residing in central jail was also matched to make valid comparisons.

Assessment of demographic details

Prior to the clinical examination, information on age, sex, education, type of psychiatric disorder, medication used for illness, duration spent in the jail, along with tobacco related habits, and extent of knowledge about the risk factors of oral cancer was obtained from the surveyed subjects.

Clinical assessment of mucosal lesions

The clinical examination was carried out by using the criteria as prescribed by Oral Health Survey - Basic Methods, WHO (1997).[21] The oral examination was made using a mouth mirror and community periodontal index probe on a dental chair in the dental unit of central jail, Bhopal by a single trained and calibrated investigator. The investigator read, understood, and standardized his method of operation so as to minimize error and have reproducible data. A trained recording clerk assisted the examiner in recording procedures.

An examination of the oral mucosa and soft tissues in and around the mouth was made on every subject. The examination was performed in the following sequence:

Labial mucosa and labial sulci (upper and lower)

Labial part of the commissure and buccal mucosa (right and left)

Tongue (dorsal and ventral surfaces, margins)

Floor of the mouth

Hard and soft palate

Alveolar ridges/gingiva (upper and lower).

Mouth mirror and the handle of the periodontal probe were used to retract the tissues.

Statistical analysis

All the obtained data were entered into a personal computer on Microsoft excel sheet and analyzed by using a software; Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS; IBM, USA) version 20. Data comparison was carried out by applying Chi-square test and t-test. Similarly, the association of different variables with mucosal lesions was analyzed by using step wise multiple linear regression analysis. The statistically significant level was fixed at P < 0.05 with a confidence interval of 95%.

RESULTS

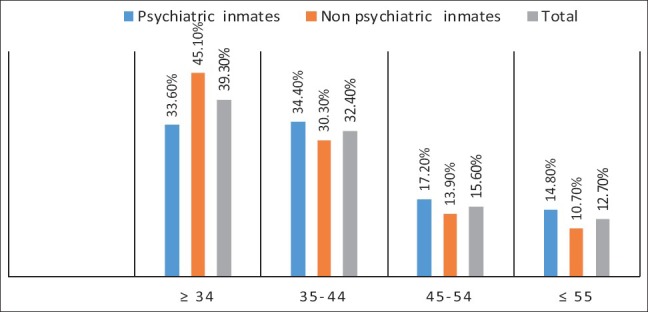

A total of 244 inmates (all males) were equally distributed into two groups, that is, 122 (50%) psychiatric inmates and 122 (50%) nonpsychiatric inmates. Highest number of inmates, that is, 96 (39.3%) were in the age group of less than 34 years while, lowest of 31 (12.7%) inmates belonged to age group above 55 years. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.310) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Distribution of inmates according to age

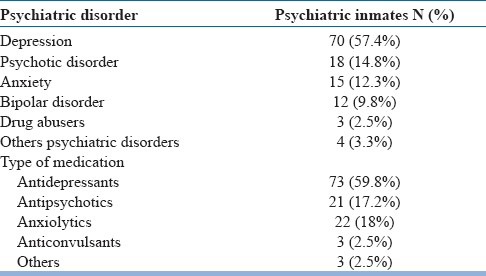

Among 122 psychiatric inmates, about 70 (57.4%) of inmates had a diagnosis of depression, 18 (14.8%) had psychotic disorders (like schizophrenia), and 15 (12.3%) had anxiety disorder. About 12 (9.8%) bipolar disorder, 3 (2.5%) drug abusers, and remainder 4 (3.3%) had others psychiatric disorders (e.g. dementia and sexual dysfunction). However, the majority of psychiatric inmates, 73 (59.8%) were receiving antidepressants. About 21 (17.2%) and 22 (18%) inmates were taking antipsychotics and anxiolytic drugs. Only 3 (2.5%) were taking anticonvulsants and other kind of psychiatric medications [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of psychiatric inmates according to psychiatric disorder and type of medication

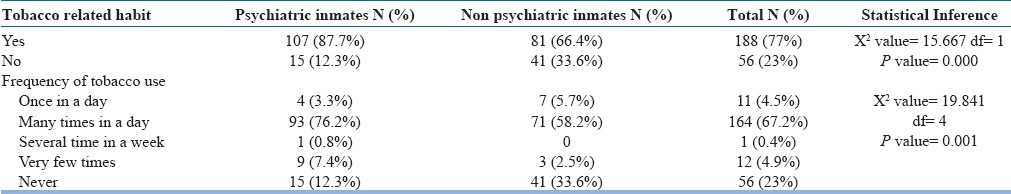

A total of 188 (77%) study inmates, which comprised of 107 (87.7%) psychiatrics and 81 (66.4%) nonpsychiatrics had a habit of tobacco consumption (smokeless or smoking). The difference in tobacco consumption among inmates was statistically significant (P = 0.000). Similarly, the frequency of tobacco consumption many times a day was highest among 93 (76.2%) psychiatric inmates, followed by 71 (58.2%) nonpsychiatric inmates. The difference in frequency of tobacco consumption among inmates was statistically significant (P = 0.001) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Distribution of inmates according to tobacco related habits and frequency of tobacco use

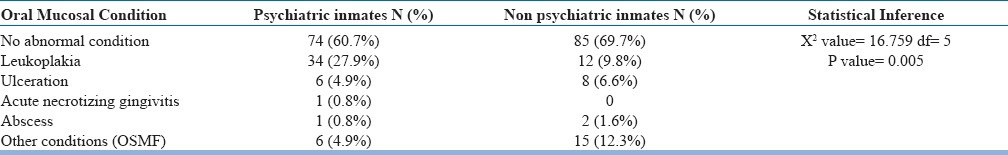

Overall prevalence of oral mucosal lesions among the inmates was 85 (34.8%) which comprised of 48 (39.3%) psychiatric inmates and 37 (30.3%) nonpsychiatric inmates. Leukoplakia 18.9%, OSMF 8.6%, and ulceration 5.7% were the major oral mucosal conditions observed. Leukoplakia was most prevalent among psychiatric inmates, that is, 34 (27.9%) followed by 12 (9.8%) nonpsychiatric inmates. Although, prevalence of OSMF among nonpsychiatric inmates was highest, that is, 15 (12.3%) compared with 6 (4.9%) psychiatric inmates. The difference in distribution of oral mucosal conditions among inmates was statistically significant (P = 0.005) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Distribution of oral mucosal conditions among inmates

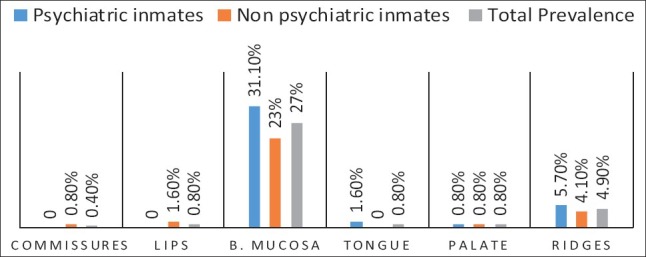

Among 38 (31.1%) psychiatric inmates and 28 (23%) nonpsychiatric inmates; buccal mucosa (27%) was found to be the most affected site with oral mucosal lesions. Alveolar ridge/gingiva was affected in 7 (5.7%) psychiatric inmates followed by 5 (4.1%) nonpsychiatric inmates. The difference in distribution of locations for oral mucosal lesion among inmates was not statistically significant (P = 0.268) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Distribution of locations for oral mucosal lesion among inmates

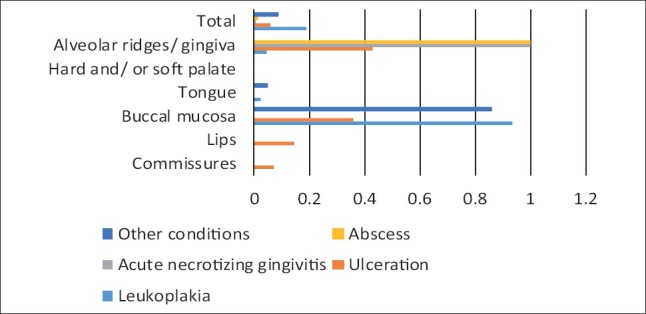

Most of the mucosal conditions such as leukoplakia (93.5%) and OSMF (85.7%) were present on buccal mucosa whereas, a majority of (42.9%) ulcerations were present on alveolar ridges/gingiva. The difference in distribution of mucosal conditions by location was statistically significant (P = 0.000) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Distribution of oral mucosal conditions by location

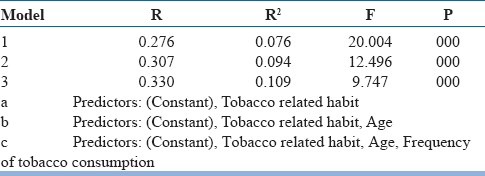

The step-wise multiple linear regression analysis, which was executed to estimate the linear relationship between oral mucosal lesions as a dependent variable and various other independent variables showed that the best predictors in the descending order for oral mucosal lesions were tobacco related habits, age, and frequency of tobacco consumption. Mucosal lesions show great association with tobacco related habits. It also reveals that all the independent variables were significantly associated with oral mucosal lesions (P = 0.000) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Step-wise multiple linear regression analysis with oral mucosal lesion as a dependent variable

DISCUSSION

Very few studies have been carried out on the oral health status of prisoners across the globe. In the present study, a very first of its kind, pioneering attempt has been made to assess the prevalence of oral mucosal lesions among psychiatric jail inmates residing in central jail, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India. The oral examination was conducted by using WHO oral health assessment proforma 1997.

The present study had two limitations: first all the inmates recruited were male subjects. The second was lack of literature on the subject at both country and international level for comparison and discussion purposes. Nevertheless, a sincere attempt has been made to compare our data with studies conducted among psychiatric patients and general population.

A total of 244 inmates distributed into two groups, that is, 122 (50%) psychiatric inmates and 122 (50%) nonpsychiatric inmates were recruited in the study. The highest number of inmates 39.3% were in the age group of less than 34 years, while, lowest of 12.7% inmates belonged to age group above 55 years and no significant difference was observed in the distribution of age among two groups.

Among psychiatric inmates, about 57.4% of inmates had a diagnosis of depression (affective mood disorder). The next psychiatric condition, which was prevalent were psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia (14.8%), followed by anxiety disorder (9.8%) and bipolar disorder (2.5%). These findings are similar to the study on psychiatric patients conducted in Copenhagen by Hede.[22]

They found that majority of the subjects, that is, 34% were with affective mood disorder. Furthermore, a study in Virginia by Barnes et al.[23] showed that majority (38%) were diagnosed with affective mood disorder and second large proportion were diagnosed to be having schizophrenia. According to the severity of symptoms, the psychotic disorders are generally ranges from mild, moderate to severe. In our study, no attempt was made to classify them based on their severity of symptoms.

The majority of psychiatric inmates, 59.8% were receiving antidepressants, followed by 17.2% antipsychotics and 18% anxiolytic drugs. These findings are similar to a study conducted by Kebede et al.[24] where, 65.8% patients were receiving antidepressants, and 17.5% antipsychotics.

In our study, it was observed that duration in the jail is directly related to increased prevalence of mental disorder among inmates. This can be attributed to many factors like extremely stressful living conditions present in jail, feeling of loneliness, derived and solitary life of an individual, etc.

The overall prevalence of clinically significant oral lesions among total population was 34.8% which mainly comprised of 39.3% psychiatric inmates and 30.3% nonpsychiatric inmates. The proportion of mucosal lesions in our study was higher in comparison to studies conducted by Mehrotra et al.[10] and Saraswathi et al.[25] where prevalence of mucosal lesions among general population was 8.4% and 4.1% respectively. High prevalence of oral mucosal lesion in our study could be attributed to high intake of tobacco chewing both in study and control group. This probably be due to higher prevalence of smoking and/or tobacco chewing habits observed among our study participants. This conclusion is in accordance with observations drawn by Vellappally et al.[26] where the highest prevalence of oral mucosal lesions were present in tobacco chewers (22.7%) followed by regular smokers (12.9%), occasional smokers (8.6%), ex-smokers (5.1%), and nontobacco users (2.8%). In our study, marked rise in consumption of tobacco (smoked and smokeless) and associated products (gutkha, paan masala, khaini, areca nut, etc.) was observed among psychiatric (87.7%) and nonpsychiatric inmates (66.4%). The higher usage of tobacco among study population can be correlated with stressful conditions of prison along with depression. Inmates may probably felt that use of these products reduces stress, tiredness and brought in excitement in the body.[27] Similarly, depression has been consistently associated with smoking,[28] in this study, the mentally ill group smoked more and for longer duration than the healthy individuals.

Of the clinically significant lesions which were diagnosed in our study, the percentage of patients suffering from leukoplakia was 18.9%, OSMF 8.6%, and ulceration 5.7% which are higher to those found by Mehrotra et al.[10] (9.7%, 40.7%, and 2.7%) and Saraswathi et al.[25] (0.59%, 0.55%, and 0.15%). Leukoplakia was most prevalent among psychiatric inmates (27.9%) while, prevalence of OSMF among nonpsychiatric inmates was highest (12.3%). Many studies have shown that subjects who smoked or chewed tobacco in any form had a far higher incidence of oral lesions vis-à-vis nonusers. On assessing the correlation of habits with incidence of leukoplakia, it was found that smokers had an odds ratio of 4.5 while chewers had 5.6 as compared to nonusers.[10] Same author has also revealed that subjects who chewed areca nut with or without tobacco had a higher prevalence of OSMF.

On the basis of site of involvement, it was found that, among total 34.8% mucosal lesions, majority, that is, 27% lesions were present on buccal mucosa followed by alveolar ridges/gingiva (4.9%), tongue, lips, hard or soft palate (0.8% respectively). Similar conclusion were obtained by Bhurgri[29] in her report from South Karachi, Pakistan on oral malignancy where buccal mucosa was the most frequently involved site (55.9%).

Most of the oral mucosal lesions found in our study, that is, leukoplakia (93.5%), and OSMF (85.7%) were associated with buccal mucosa whereas, abscess (100%) and ulcerations (42.9%) were most common on alveolar ridge/gingiva. Similar findings were obtained by Mathew et al.[30] where buccal mucosa was highly affected with conditions such as leukoplakia and OSMF.

Step-wise multiple linear regression analysis with oral mucosal lesion as a dependent variable showed that tobacco related habits, age, and frequency of tobacco consumption had greatest association with mucosal lesions (P = 0.000). Similar variables were recorded in a report presented by Dangi et al.[31]

The findings of the present study revealed that tobacco use amongst psychiatric inmates of central jail, Bhopal is an issue of significant concern, which had a serious impact on their oral health status. Working toward the mitigation of factors affecting tobacco menace at the individual level as well as at the institutionalized level should be implemented as a part of a long term commitment to safeguard public health. Antitobacco initiatives are thus warranted.

Further comparative studies with a larger sample size and with addition of more number of similar institutionalized settings are recommended to focus on a broader assessment of oral health status of psychiatric inmates and correlating it with possible associating factors.

CONCLUSION

The information presented in this study adds to our understanding of the common oral mucosal lesions occurring in a psychiatric inmate population. Leukoplakia and OSMF were the most common types of oral mucosal lesions found. Mucosal lesions were most common among inmates having tobacco related habits. Efforts to increase patient awareness of the oral effects of tobacco use and to eliminate the habit are needed to improve oral and general health of the prison population. Special attention to the psychiatric inmates should be provided by including the periodic monitoring of their oral health. The greater coordination between dentists and psychiatrists may better serve the needs of this underprivileged population. The results of this study should serve as the basis for a larger, nation-wide survey of oral lesions among institutionalized communities like psychiatric inmates.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silverman S, Jr, Gorsky M, Lozada F. Oral leukoplakia and malignant transformation. A follow-up study of 257 patients. Cancer. 1984;53:563–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840201)53:3<563::aid-cncr2820530332>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverman S., Jr Demographics and occurrence of oral and pharyngeal cancers. The outcomes, the trends, the challenge. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132(Suppl):7–11S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lane PM, Gilhuly T, Whitehead P, Zeng H, Poh CF, Ng S, et al. Simple device for the direct visualization of oral-cavity tissue fluorescence. J Biomed Opt. 2006;11:024006. doi: 10.1117/1.2193157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myers JN, Elkins T, Roberts D, Byers RM. Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue in young adults: Increasing incidence and factors that predict treatment outcomes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:44–51. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(00)70142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehrotra R, Pandya S, Chaudhary AK, Kumar M, Singh M. Prevalence of oral pre-malignant and malignant lesions at a tertiary level hospital in Allahabad, India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008;9:263–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta PC, Sinor PN, Bhonsle RB, Pawar VS, Mehta HC. Oral submucous fibrosis in India: A new epidemic? Natl Med J India. 1998;11:113–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah B, Lewis MA, Bedi R. Oral submucous fibrosis in a 11-year-old Bangladeshi girl living in the United Kingdom. Br Dent J. 2001;191:130–2. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiu CJ, Chang ML, Chiang CP, Hahn LJ, Hsieh LL, Chen CJ. Interaction of collagen-related genes and susceptibility to betel quid-induced oral submucous fibrosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:646–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehrotra R, Thomas S, Nair P, Pandya S, Singh M, Nigam NS, et al. Prevalence of oral soft tissue lesions in Vidisha. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:23. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Markette RL, Dicks JL, Watson RC. Dentistry and the mentally ill. J Acad Gen Dent. 1975;23:28–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stiefel DJ, Truelove EL, Menard TW, Anderson VK, Doyle PE, Mandel LS. A comparison of the oral health of persons with and without chronic mental illness in community settings. Spec Care Dentist. 1990;10:6–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1990.tb01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armstrong M. Dentists and community care. Br Dent J. 1994;176:48–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brinded PM, Simpson AI, Laidlaw TM, Fairley N, Malcolm F. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in New Zealand prisons: a national study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35:166–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brugha T, Singleton N, Meltzer H, Bebbington P, Farrell M, Jenkins R, et al. Psychosis in the community and in prisons: a report from the British National Survey of psychiatric morbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:774–80. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holley HL, Arboleda-Flórez J, Love E. Lifetime prevalence of prior suicide attempts in a remanded population and relationship to current mental illness. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 1995;39:190–209. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abram KM, Teplin LA, McClelland GM. Comorbidity of severe psychiatric disorders and substance use disorders among women in jail. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1007–10. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teplin LA. The prevalence of severe mental disorder among male urban jail detainees: comparison with the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:663–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.6.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh T, Tickle M, Milsom K, Buchanan K, Zoitopoulos L. An investigation of the nature of research into dental health in prisons: a systematic review. Br Dent J. 2008;204:683–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.STROBE-Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology. [Last cited on 2013 Mar 13]. Available from: http://www.strobe-statementorg/?id=available-checklists .

- 21.World Health Organization. 4th ed. Ch 5. New Delhi, India: AITBS Publishers and Distributors; 1997. Oral Health Survey, Basic Methods; pp. 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hede B. Oral health in Danish hospitalized psychiatric patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1995;23:44–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1995.tb00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnes GP, Allen EH, Parker WA, Lyon TC, Armentrout W, Cole JS. Dental treatment needs among hospitalized adult mental patients. Spec Care Dentist. 1988;8:173–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1988.tb00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kebede B, Kemal T, Abera S. Oral health status of patients with mental disorders in southwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saraswathi TR, Ranganathan K, Shanmugam S, Sowmya R, Narasimhan PD, Gunaseelan R. Prevalence of oral lesions in relation to habits: Cross-sectional study in South India. Indian J Dent Res. 2006;17:121–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.29877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vellappally S, Jacob V, Smejkalová J, Shriharsha P, Kumar V, Fiala Z. Tobacco habits and oral health status in selected Indian population. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2008;16:77–84. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasat V, Joshi M, Somasundaram KV, Viragi P, Dhore P, Sahuji S. Tobacco use, its influences, triggers, and associated oral lesions among the patients attending a dental institution in rural Maharashtra, India. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2012;2:25–30. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.103454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall SM, Muñoz RF, Reus VI, Sees KL. Nicotine, negative affect, and depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:761–7. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.5.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhurgri Y. Cancer of the oral cavity-trends in Karachi South (1995-2002) Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2005;6:22–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathew AL, Pai KM, Sholapurkar AA, Vengal M. The prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in patients visiting a dental school in Southern India. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:99–103. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.40461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dangi J, Kinnunen TH, Zavras AI. Challenges in global improvement of oral cancer outcomes: Findings from rural Northern India. Tob Induc Dis. 2012;10:5. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-10-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]