Abstract

Vanadium, abbreviated V, is an early transition metal that readily forms coordination complexes with a variety of biological products such as proteins, metabolites, membranes and other structures. The formation of coordination complexes stabilizes metal ions, which in turn impacts the biodistribution of the metal. To understand the biodistribution of V, V in oxidation state IV in the form of vanadyl sulfate (25, 50, 100 mg V daily) was given orally for 6 weeks to 16 persons with type 2 diabetes. Elemental V was determined using Graphite Furnas Atomic Absorption Spectrometry against known concentrations of V in serum, blood or urine. Peak serum V levels were 15.4±6.5, 81.7±40 and 319±268 ng/ml respectively, and mean peak serum V was positively correlated with dose administered (r=0.992, p=0.079), although large inter-individual variability was found. Total serum V concentration distribution fit a one compartment open model with a first order rate constant for excretion with mean half times of 4.7±1.6 days and 4.6±2.5 days for the 50 and 100 mg V dose groups respectively. At steady state, 24 hour urinary V output was 0.18±0.24 and 0.97±0.84 mg in the 50 and 100 mg V groups respectively, consistent with absorption of 1 percent or less of the administered dose. Peak V in blood and serum were positively correlated (r=0.971, p<0.0005). The serum to blood V ratio for the patients receiving 100 mg V was 1.7±0.45. Regression analysis showed that glycohemoglobin was a negative predictor of the natural log (ln) peak serum V (R2=0.40, p=0.009) and a positive predictor of the euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp results at high insulin values (R2=0.39, p=0.010). Insulin sensitivity measured by euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp was not significantly correlated with ln peak serum V. Globulin and glycohemoglobin levels taken together were negative predictors of fasting blood glucose (R2=0.49, p=0.013). Although V accumulation in serum was dose-dependent, no correlation between total serum V concentation and the insulin-like response was found in this first attempt to correlate anti-diabetic activity with total serum V. This study suggests that V pools other than total serum V are likely related to the insulin-like effect of this metal. These results, obtained in diabetic patients, document the need for consideration of the coordination chemistry of metabolites and proteins with vanadium in anti-diabetic vanadium complexes.

1. INTRODUCTION

V is an early transition metal which readily forms coordination complexes with a range of biological products such as proteins, metabolites, membranes or other structures. Metal ions are stabilized by formation of coordination complexes1–11. These complexes are important to the biodistribution of the metal3, 7, 12–18 For example, V is well known to complex with transferrin1, 19, 20 thereby decreasing the potentially biologically active V pool in the blood21–24. However, transferrin is not the only enzyme that interacts with vanadium, and in particular the mode of action of vanadium compounds have been implicated in the inhibition of a range of different enzymes1, 25–27. It is well recognized that vanadium undergoes redox chemistry after administration19, and a wide range of hydrolytic coordination chemistry takes place forming complexes with both metabolites and proteins7, 8, 11, 12, 19, 26, 28–35. In this manuscript we describe the pharmacokinetics of a V salt, with the vanadium in oxidation state IV and in the form of vanadyl sulfate, administered to type 2 diabetic patients to determine the role of compartmentalization in metal distribution.

The distribution of most drugs in serum correlates with pharmacological response. Enzymatic processing of organic drugs reduces their presence until they have been completely metabolized or excreted. In the case of metal based drugs the fate of the drug (the metal complex) involves the formation of new metal-coordination complexes3, 8, 12, 14, 19, 20, 29, 30, 36, 37. Since the metal ions do not participate in the same reactions as organic compounds, they either persist with a continued pharmaceutical response, accumulate in a non-active silent reservoir or are excreted. In the present work we analyze pharmacokinetic properties of orally administered vanadyl sulfate (VOSO4) monitoring blood and serum levels, pharmacological response and excretion.

A number of chemical forms of V (that is coordination compounds) are currently under study as potential drug candidates for the treatment of diabetes. Properties of V compounds vary dramatically depending on ligand and oxidation state of the metal, thus a wide range of complexes have been explored in isolated cells38, 39, in animals3, 40–42 and even in humans7, 43–46. In general the modification of ligands can change the observed insulin response and in many cases marginal, if any, improvement is observed8, 42, 47–50. Administered metal salts and complexes are processed in cells and animals via metabolism which generally results in the alteration of the vanadium-containing species1, 3, 19, 29, 30, 51–53. In this manuscript we refer to V speciation to mean the distribution of V in different oxidation states, bound to small molecules such as citrate and glutathione or bound to macromolecules (such as proteins and membranes)15–18. Also, experiments conducted in the laboratory in buffered solutions or biological media are referred to as in vitro studies, while work in isolated cell systems will be referred to as cellular studies.

Human studies administering vanadyl or vanadate at doses of 33 to 50 mg elemental V per day have demonstrated improved glycemia evidenced by decreased fasting blood glucose and glycohemoglobin43, 45, 46 and some studies showed improved insulin sensitivity during euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp43, 54. It is important to assess dose response relationships of all vanadium species and their pharmacokinetic parameters as candidate drugs to treat diabetes are developed.

Vanadium is poorly absorbed after oral administration, is eliminated primarily in the urine, and can be modeled by first order kinetics of elimination following an initial distribution phase as seen in animals given tracer doses of48V55, 56. Adipose tissue and bone are depots for V storage and account for a major portion of the total V body burden57, 58. Although the oxidation state of administered inorganic V compounds had little effect on the tissue, blood and serum levels of V after equivalent doses in the rat59, organovanadium compounds can display considerably different absorption, distribution and excretion than the inorganic V compounds29. For example, vanadate is taken up by human red blood cells and this uptake is blocked in the presence of 4,4’-diisothiocyano-2,2’-stilbene disulphonate (DIDS), a specific inhibitor of the general anion transporter60. In contrast, there is no change in the uptake of VO(acac)2 in the presence or absence of DIDS. These studies demonstrate that vanadate and VO(acac)2 are taken up by the cells by different mechanisms60. Differences in biological response may be related to the coordination chemistry of the form of the V used in these studies combined with the V speciation that occurs both within the cells and in the experimental media used.

There are few studies on the natural pharmacokinetics of V compounds in humans. These studies generally use units of microg per liter (µg/l) which corresponds to 50 times lower concentrations than the microMolar and nanoMolar concentrations seen in pharmacological studies. Normal blood concentrations of V are reported to be 0.4–2.8 µg/l, with the majority of the V associated with the serum fraction ranging from 2–4 µg/l61, 62. Normal levels of V in urine have an upper limit reported to be 22 µg/l, and excretion averaged less than 8 µg/24 hours. The total body burden in non-occupationally exposed human subjects is estimated to be approximately 430 µg/kg, and the daily intake is estimated to be 2.5 mg/day63.

Few V speciation studies have been performed in any living system, because the analytical techniques used to measure total V do not inform on speciation13, 20, 64. The distribuion of V(IV) and (V) in yeast exposed to vanadate in the medium has been assessed using both EPR and51V-NMR51. The formation of V (IV) species has also been measured in rats by EPR following injection of various V coordination complexes65. Based on known speciation profiles the simplest monomeric forms of the V exist at low V concentration. Also, drugs such as bis(maltolato)oxovanadium(IV),66 bis(picolinato)oxovandium(IV)67 and dipicolinatocisdioxidovanadium68 at low concentrations will eventually dissociate. Only the very strongest complexes such as V-transferrin and V-citrate will remain intact22, 69. There results are supported in rat studies using48V and14C labeled bis(ethylmaltolato)oxovanadium(IV) which show the metal and the ligand separating within one hour of administration29, 30.

The present study builds on a clinical trial in which three groups of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus were administered oral doses of 25, 50, and 100 mg V in oxidation state IV as VOSO4 three times daily with meals for six weeks. Improved fasting blood glucose was seen in approximately 50% of the patients in the two higher dose groups and has been the subject of a previous report44. The current study reports on the pharmacokinetics of V in the same patients.

2. EXPERIMENTAL

2.1 Patient protocol

Sixteen subjects with type 2 diabetes were studied for 12 weeks in a single mask placebo lead-in trial design as previously described44. Briefly, after baseline laboratory testing for a period of one week subjects were started on placebo 2 tablets orally, three times per day with meals for three weeks. At the end of placebo treatment subjects were admitted to the General Clinical Research Center of Brigham and Women’s Hospital for a two-step euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp study to quantify insulin sensitivity. Subjects were then switched from placebo to 25, 50 or 100 mg V/day administered orally in tablets with meals (3 per day), as VOSO4 (for respective daily doses of 75, 150, 300 mg) for six weeks. After the sixth week of VOSO4 the euglycemic insulin clamp studies were repeated and VOSO4 was discontinued. Subjects were monitored for an additional 2 weeks. Blood samples were taken periodically for biochemical monitoring, and determination of whole blood and serum V concentrations. Throughout the study patients were instructed to monitor their blood glucose four times daily, prior to meals and at bedtime with a One Touch™ glucose monitor and weekly values were reported as averages for each of the four time points. Patients collected 24 hour urine samples at various times throughout the experiment.

2.2 Insulin Sensitivity

Two step euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp studies were done pre-treatment and post-treatment to assess insulin sensitivity as described44. Briefly, variable rate low-dose insulin infusion was administered overnight prior to the clamp to normalize blood glucose. After collection of baseline samples for hormones and substrates, a primed-continuous infusion of insulin at 0.5 mU insulin/kg/min (low dose) was started for a 2 hour period, immediately followed by a second 2 hour infusion at 1.0 mU insulin/kg/min, (high dose). Throughout insulin administration, glucose was determined at 5 min intervals and a variable rate of glucose infusion was adjusted to maintain euglycemia. Insulin sensitivity is reported for the two steady-state hyperinsulinemic levels as the metabolic rate (M) of glucose uptake normalized for the mass in kilograms of the subject.

2.3 Metal Analysis

Blood, serum and urine levels of elemental V were determined by Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry (GFAAS) using a Perkin Elmer 4110ZL unit with Zeeman correction equipped with an AS40 Autosampler. Sample V concentration was determined against a standard curve analyzed on the same day as the samples. One quality control sample, of concentration 100 ng/ml elemental V in blood and 250 ng/ml in serum and urine, was analyzed for every ten samples. A limit of detection (LOD) analysis was performed based on the standard deviation (SD) of responses of multiple determinations (usually between ten and thirty) of a blank sample and the mean slope (SLP) of the calibration line from day to day. In this analysis, LOD=3.3 (SD/SLP), and was calculated to be 13.5 ng/ml for blood V, 18.3 ng/ml for serum V and 16.4 ng/ml for urine V (ten determinations of the blank used for each). Blood standards, with concentrations of 0, 25, 50, 100, 250 ng/ml, were prepared by adding known amounts of V to sheep’s blood. Serum and Urine standards were prepared in a similar fashion with two additional standards, of concentration 500 and 1000 ng/ml. Patient samples were aliquoted to a volume of 0.50 ml. Serum and urine samples can then be analyzed directly. Blood samples interfere upon direct GFAAS analysis, therefore both standards and samples needed further preparation. The 0.50 ml standards and samples were dried at 55 degrees Celsius for approximately 48 hours. They were then heated in a CEM Microwave Muffle Furnace according to the following program: 30 minutes at 200 degrees C, 30 minutes at 300 degrees C, 20 minutes at 400 degrees C, 15 minutes at 600 degrees C, and finally 60 minutes at 700 degrees C, resulting in complete ashing of the samples. The standards and samples were reconstituted to 0.125 ml with 0.05% sulfuric acid for GFAAS analysis.

2.4 Statistical and Kinetic Analysis

Correlation analysis was used to examine associations among the measures of clinical response and between the clinical response measures and blood components. Measurements of serum V and blood components were made on 10 separate days. The day of peak serum V was determined for each patient, and serum and blood values on day of peak serum were used for the correlation analyses. Stepwise regression analysis was used to search for multivariate predictors of clinical response variables. Correlation and regression analyses were carried out using Minitab and R statistical software.

Serum and blood V kinetics were modeled using a first-order kinetic model of the type Ct = Co e−k (t – to), where Ct is the serum concentration at time t, Co is the initial concentration at time to, and k is the elimination constant. This model was used to fit the elimination data, using four measurements that include the last day of treatment and three subsequent measurements. The time to was assumed to be the day the treatment was stopped and a non-linear least squares algorithm in SPlus statistical software was used to estimate Co and k. These parameters were then used to model V accumulation from the day the treatment started to the day it ended. The model used for V accumulation was: Ct = Co (1 - e−k (t – to)). Areas under the whole blood and serumV concentration curves were computed and these areas represent the patient's total integrated exposure to V in whole blood and in serum, respectively.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Determination of total Vanadium in blood, serum and urine

The time course for total elemental V concentration in serum or blood and the urinary V clearance are shown in Figures 1–3 for individual patients receiving 25, 50 and 100 mg V per day respectively. Individual response to the drug was variable. Generally patients receiving the three V dose rates exhibited a serum accumulation of V during the dosing phase until a steady state serum concentration was achieved. The time course profiles for urinary clearance of V were closely related to the kinetic profiles for serum and blood V concentrations. Upon termination of exposure, there was an exponential decline in serum and blood V concentration, which was fit to a one compartment pharmacokinetic model, and kinetic parameters were calculated for each patient as well as for the aggregate data for each dose group.

Fig. 1.

Time course for serum vanadium concentration and urine vanadium clearance in patients dosed with 25 mg V. Patients were dosed for forty days with 25 mg V as vanadyl sulfate. A four-week pre-treatment period is followed by the forty-day dosing period and a sixteen-day washout. Serum V concentration (ng/ml, Panel A) and urine V clearance (mg/24 hr, Panel B) for three individual patients (○) 25V-1, (▲) 25V-2, and (■) 25V-3, are shown.

Fig. 3.

Time course for serum vanadium concentration, urine vanadium clearance, and blood vanadium concentration in patients dosed with 100 mg vanadium. Patients were dosed for forty days with 100 mg V as vanadyl sulfate. A four-week pre-treatment period is followed by the forty-day dosing period and a sixteen-day washout. Serum V concentration (ng/ml, Panel A), urine V clearance (mg/24 hr, Panel B), and blood V concentration (ng/ml, Panel C) for eight individual patients (◆) 100V-1, (✕) 100V-2, (▲) 100V-3, (■) 100V-4, (△) 100V-5, (●)100V-6, (○)100V-7, and (□) 100V-8 are shown.

Summary data for serum and blood V levels for individual patients are shown in Table 2. For the 25 mg dose group, whole blood V concentrations were not determined and serum V concentrations in that group were very near the LOD. Only limited kinetic parameters could be calculated for that group. In comparing the three dose groups, peak V concentrations in serum and blood displayed a dose dependent increase. V dose administered correlated with peak serum V concentration, r=0.985 (p=0.079). Peak V concentration in blood had a positive correlation with serum V, r=0.971 (p < 0.0005). Peak serum V and steady state (SS) serum V were also correlated (R2=0.93). Serum V concentrations were modeled using a first-order kinetic model as described earlier. Figure 4 presents an example of curve fits generated with this model using rate constants derived from the decline phase. Individuals were selected which provide a typical fit (Panel A) and the worst fit obtained (Panel B) from all patients analyzed. In both panel A and panel B, the fit of the actual data to the decline phase is acceptable. The greatest deviation of the actual to the theoretical points occurs during the dosing phase. In both cases, the model provides a reasonable representation of the actual data.

TABLE 2.

Serum and Blood Vanadium Data

| Patient IDa |

Pk Serum V (ng/mL) |

SS Serum V (ng/mL) |

Ser V t1/2 (days) |

AUCd Serum V |

Pk Blood V (ng/mL) |

SSb Blood V (ng/mL) |

Bld V t1/2 (days) |

AUCd Blood V |

AUCSer V / AUCBld V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25V-1 | 16.7 | 16.9 | 2.1 | NDb | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 25V-3 | 21.1 | 13.9 | 3.3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| MEAN | 18.9 | 15.4 | 2.7 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 50V-1 | 114 | 104 | 4.20 | 3894 | 109 | 111 | 4.4 | 3474 | 1.12 |

| 50V-2 | 30.2 | 30.4 | 4.30 | 946 | 50 | 50 | 3.9 | 2025 | 0.46 |

| 50V-3 | 51.7 | 18.8 | 4.91 | 617 | 75 | 45 | 6.7 | 1788 | 0.34 |

| 50V-4 | 125 | 93.4 | 7.22 | 3538 | 163 | 101 | 10.0 | 3762 | 0.94 |

| 50V-5 | 87.0 | 68.1 | 2.96 | 1747 | 26 | 17 | 2.9 | 701 | 2.49 |

| MEAN ± SD | 81.7 ± 40.5 | 63.1 ± 37.8 | 4.7 ± 1.6 | 2149 ± 1494 | 85 ± 54 | 65 ± 39 | 5.6 ± 2.8 | 2351 ± 1264 | 1.07 ± 0.85 |

| 100V-1 | 252 | 234 | 3.19 | 8695 | 136 | 141 | 4.0 | 5648 | 1.53 |

| 100V-2 | 227 | 238 | 3.81 | 8328 | 132 | 147 | 4.3 | 5863 | 1.42 |

| 100V-3 | 423 | 397 | 5.87 | 15779 | 264 | 269 | 7.2 | 10552 | 1.49 |

| 100V-4 | 906 | 668 | 3.22 | 26713 | 654 | 546 | 6.1 | 20245 | 1.31 |

| 100V-5 | 213 | 211 | 2.00 | 8041 | 95 | 94 | 2.1 | 3741 | 2.14 |

| 100V-7 | 368 | 326 | 4.91 | 11412 | 225 | 175 | 3.0 | 6998 | 1.63 |

| 100V-8 | 144 | 126 | 9.49 | 4781 | 95 | 60 | 8.7 | 2341 | 2.04 |

| MEAN ± SD | 319 ± 268 | 314 ± 178 | 4.6 ± 2.5 | 11965 ± 7340 | 201 ± 200 | 205 ± 164 | 5.1 ± 2.4 | 7912 ± 6023 | 1.65 ± 0.31 |

Patients 25V-2 and 100V-6 are not presented as 25V-2’s serum [V] was less than the LOD throughout the experiment and 100V-6 had only one point above it.

Steady state levels were determined after 5 half lives for elimination.

Not Determined

Units for AUC were (ng/mL)days

Fig. 4.

Vanadium accumulation and removal from serum in patients receiving 100 mg V per day as vanadyl sulfate. The decline phase was fit to a one-compartment open model using the equation Ct = Baseline Concentration + Co e−kt. The elimination constant (k) from the washout period was then used to fit the accumulation phase by the equation Ct = Baseline Concentration + Co (1- e−kt). Panel A is patient 100V-3 and Panel B is patient 100V-4. The patients’ observed serum V levels are indicated by (■) in both panels.

The areas under the curve (AUC) in (ng/mL)days were calculated for the exposure and decline phases of both serum and whole blood, and are provided along with the ratio of serum AUC to whole blood AUC in Table 2. There was considerable variability among individuals in the respective AUCs and ratios. For the 50 mg dose group, which had a mean value of 1.07±0.86 (ng/mL)days, the individual values ranged from 0.34 to 2.49. The individual ratios for the 100 mg dose group were much less variable and displayed a mean value of 1.65±0.32 (ng/mL)days.

Half times calculated from the decline phase after termination of dosing were similar for serum and whole blood. The mean half time for V in serum was 4.7±1.6 days in the 50 mg dose group compared to 4.6±2.5 days in the 100 mg dose group. The mean half times for V in whole blood were 5.6±2.8 days and 5.1±2.4 days for the same dose groups respectively. There were no significant dose dependent differences in half times when the 50 and 100 mg dose groups were compared for both whole blood and serum.

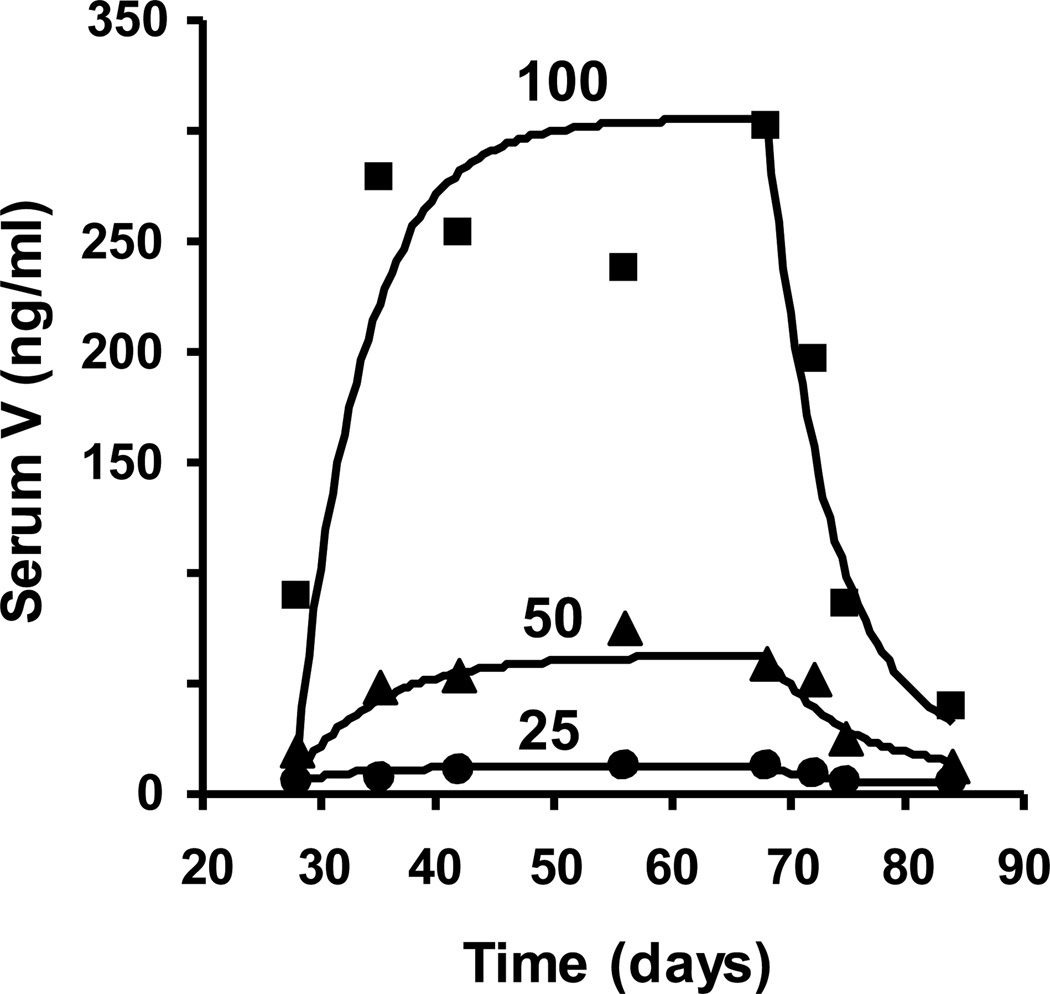

The kinetic profiles for the accumulation and decline of mean serum V concentration for the composite data of each dose group is seen in Figure 5. The half times calculated from the decline phase in the 50 and 100 mg dose groups of 4.9 days and 3.8 days compared reasonably well with the means for the individuals described above. Since the half times for the dose groups were similar, there was a similar kinetic profile in the approach to steady state during the dosing phase. Although the approach to steady state was similar for all doses, with 95% of the steady state concentration being reached in approximately 20 days, the steady state concentrations reached in each case was not directly proportional to the dose; rather there was a more than proportional increase in steady state serum concentration with increasing dose.

Fig. 5.

Composite serum vanadium accumulation and decline curves for all patients dosed at 25, 50, and 100 mg V as vanadyl sulfate. The mean concentrations of V for each time point of the decline phase were used to generate the first order elimination constant for a one-compartment open model using the equation Ct = Baseline Concentration + Co e−kt. The elimination constant (k) from the washout period was then used to fit the accumulation phase by the equation Ct = Baseline Concentration + Co (1- e−kt). Mean serum V levels are indicated by (●) for the 25 mg V dose, (▲) for the 50 mg V dose, and (■) for the 100 mg V dose.

Individual patient data for 24 hour urinary clearance performed during steady state are presented in Table 3. The number of determinations varied from one to three values per patient. V output in urine was dose dependent. Compared to the 50 mg dose group, the increase in urinary clearance of V in the 100 mg dose group was proportional to the increase observed in in steady state serum concentration of V. In this study, the overall correlation between peak serum V concentration and 24 hour urine V clearances is shown in Fig 6 with an R2=0.78 and p≤0.001. It should be noted that the four highest V points in Fig 6A came from one patient (100V-4). The correlation coefficients were highly variable among the patients studied, ranging from 0.170 to 0.932 as seen in Table 4.

TABLE 3.

Steady State Urinary Vanadium Clearance Data

| Patient IDa |

Number of Samples at Steady State (n) |

Mean Urine [V] at Steady State (ng/mL) |

Mean Urine Volume at Steady State (L/day) |

Mean Urinary V Clearance at Steady State (mg/24hr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25V-1 | 1 | 60 | 0.7 | 0.04 |

| 25V-3 | 3 | 47 | 2.6 | 0.10 |

| MEAN | 54 | 3.3 | 0.08 | |

| 50V-1 | 2 | 165 | 2.5 | 0.41 |

| 50V-2 | 2 | 18 | 4.0 | 0.08 |

| 50V-3 | 2 | 22 | 1.6 | 0.03 |

| 50V-4 | 1b | 215 | 2.4 | 0.52 |

| 50V-5 | 3 | 29 | 2.0 | 0.06 |

| MEAN ± SD | 59 ± 80 | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 0.18 ± 0.24 | |

| 100V-1 | 3 | 412 | 1.9 | 0.86 |

| 100V-2 | 2 | 468 | 2.2 | 0.96 |

| 100V-3 | 2 | 457 | 1.8 | 0.84 |

| 100V-4 | 3 | 2199 | 1.3 | 2.74 |

| 100V-5 | 3 | 207 | 2.2 | 0.37 |

| 100V-7 | 2 | 703 | 1.3 | 0.86 |

| 100V-8 | 1 | 135 | 0.7 | 0.09 |

| MEAN ± SD | 654 ± 705 | 1.6 ±0.6 | 0.97 ±0.84 |

Patients 25V-2 and 100V-6 are not presented as 25V-2’s serum [V] was less than the LOD throughout the experiment and 100V-6 had only one point above it.

Steady state is the vanadium level reached after 5 half-lives (estimated from for the washout phase).

This patient was calculated to reach steady state on day 57 but had no sample after that day, therefore day 56 is used.

Fig. 6.

Serum [V] and Urine V Clearance correlation for all patients. Serum [V] (ng/ml) is graphed vs. Urine V Clearance (mg) for all patients dosed with 25 (open triangles), 50 (open squares) and 100 (closed diamonds) mg elemental V. Panel A presents all data points. Panel B is the same graph as panel A with the axis limitations placed on it to show detail for 25 and 50 mg V patients. Note that in Panel B four highest urine V clearance points are omitted. In both panels the R2=0.78 with p≤0.001. These figures omit the data for 25V-2 and 100V-6 for reasons previously mentioned.

TABLE 4.

Correlation of Serum V (ng/ml) with Urinary V Clearance (mg/24hours) for Individual Patients

| Patient ID | # Samples Used in Analysis (n)a |

Correlation Coefficient (R2) |

|---|---|---|

| 25V-1 | 6 | 0.932 |

| 25V-3 | 7 | 0.209 |

| 50V-1 | 6 | 0.228 |

| 50V-2 | 7 | 0.817 |

| 50V-3 | 6 | 0.424 |

| 50V-4 | 6 | 0.927 |

| 50V-5 | 6 | 0.170 |

| 100V-1 | 7 | 0.345 |

| 100V-2 | 7 | 0.331 |

| 100V-3 | 7 | 0.364 |

| 100V-4 | 6 | 0.758 |

| 100V-5 | 7 | 0.971 |

| 100V-7 | 6 | 0.521 |

| 100V-8 | 5 | 0.510 |

A maximum of seven samples is possible for this analysis as done, the five samples collected during vanadium dosing and two samples after dosing was completed (the last sample, day 84, was omitted from this analysis). Patients with less than seven samples used in their analyses either had a missing serum or urine sample.

3.2 Comparison of clinical response of type 2 diabetic patients with serum V levels

We have previously shown that treatment of type 2 diabetic patients with VOSO4 improved insulin sensitivity in 3 out of 5 patients dosed with 50 mg V/day and 4 of 8 patients dosed with 100 mgV/day. However, the positive response of those patients was not sufficient to produce a statistically significant change for the mean glucose utilization of either group. The mean fasting blood glucose was significantly reduced by VOSO4 (50 and 100 mgV/day) treatment44. In the current study we examined correlations between clinical responses and peak serum V levels.

The clinical responses of all patients for mean fasting blood glucose and euglycemic clamp at low and at high insulin levels (clamp low and high) are given in Figure 7. Clinical responses were treated as a fractional response (Final Value - Original Value)/ Original Value. Thus, if V treatment improved the mean fasting glucose the fractional change would be negative, while the fractional clamp responses would be positive, indicating increased insulin sensitivity. Of the three patients receiving 25 mg V/day, one showed improved clinical responses for 2 variables. Of the 5 patients receiving 50 mg V/day, two showed an improved response for 2 variables, while 2 showed improved responses for all three variables. Of the 8 patients receiving 100 mg V/day four responded well for two variables and three responded well for all three.

Fig. 7.

Patient response to Vanadium treatment. Mean fasting blood glucose (MFG, open bar), clamp high (striped bar) and clamp low (closed bar) are presented as fractional responses. The fractional responses were calculated by subtracting the pre-vanadium treatment value from the post-vanadium treatment value and then dividing this by the pre-vanadium treatment value. A negative MFG fractional response, a positive clamp high or a positive clamp low fractional response translates to a positive response to the V treatment. A 2+ indicates two variables showed improved response. A 3+ indicates all three variables showed improved response.

To correlate peak serum V to these three clinical responses Pierson product-moment correlation coefficients and their associated p values were calculated for the natural log of peak serum V and the three fractional clinical responses for all patients. The results showed the correlation and p value of the natural log of peak serum V with mean fasting blood glucose to be 0.26, p=0.34 respectively, with low insulin clamp to be −0.17, p=0.53, and with high insulin clamp to be 0.17, p=0.53. Thus, there was clearly no correlation between peak serum V and any of the three clinical responses in these small groups of patients treated with VOSO4.

Multiple regression analysis was used to determine whether levels of blood lipids or proteins predicted clinical response or serum V levels. Table 4 shows that there was a significant correlation between glycohemoglobin and the clamp high response (R2=0.39, p=0.010), as expected as dysglycemia is associated with decreased insulin action (glucotoxicity), demonstrating the ability to detect anticipated findings in a cohort of this size. Interestingly there was a significant negative correlation between glycohemoglobin and peak serum V (R2 = 0.38, p = 0.009), and there was a significant negative correlation of both variables of the glycohemoglobin/globulin composite and fasting blood glucose (R2=0.49, p=0.013).

4. DISCUSSION

The V concentration achieved in serum and urine is highly variable in individual patients with type 2 diabetes following orally administered vandium dosed at 25, 50 and 100 mg V daily as a simple salt (75, 150 and 300 mg VOSO4). Administration of 25 mg V in only small elevations in serum V levels, which were near the LOD. Thus kinetic analysis of low dose vanadium in the 25 mg V group is hampered by the paucity of usable data, despite this dose being approximately 10-fold above the normal daily consumption of V. With higher doss, peak serum V concentrations varied by a factor of 4.1 and 6.2 in the 50 and 100 mg dose groups respectively. Similarly, the average serum steady state V concentrations varied by a factor of 3.4 and 5.3 in the same groups. There was a good correlation between mean peak serum V and dose administered. (R2=0.992, p=0.079). Individual and composite serum curves indicate that steady state (plateau) is established well within the period of dosing. Mean steady state serum V concentrations did not increase in direct proportion to the dose. The two-fold increase in dose between the 25 to 50, and 50 to 100 mg dose groups resulted in a 4 and 5 fold increase in the steady state serum V concentrations respectively. The median steady state V concentration for both serum and plasma was approximately three fold higher in the 100 mg dose group compared to the 50 mg dose group.

Both serum and whole blood V concentration fit to a one compartment open model with a first order rate constant for excretion due to the lack of an apparent terminal long-term component to the deay curves. The t1/2 in days for disappearance of V from serum was obtained from the decline phase fit to a one-compartment exponential. The half times for serum V were similar in the 50 and 100 mg dose groups. Mean half times for whole blood V were within 20% of that found in serum in the two higher dose groups. Similar kinetics have been observed in the Beagle dog with the majority of the dose following a single exponential decline with a half time of 24 hours after intravenous administration of radiolabeled vanadyl or vanadate29. Our findings cannot preclude a large number of compartments into which the V is actually distributed. A multi-compartmental model for whole body V kinetics in the sheep following both oral and intravenously administered vanadate have been reported56. A differential disposition of radiolabled V into bone, kidney, liver and testes over a 24 hour time course in the rat after oral and intraperitoneal administration of VOSO4 and BMOV has also been demonstrated29.

At steady state the amount of V excreted should provide an estimate of the minimum amount of V absorbed during oral dosing. The urine is the major clearance pathway for absorbed V70, 71. For the three doses of V used in this study, the absorption of V was less than 1% of the daily dose. As reported here, patients taking 100 mg V per day excreted approximately 1 mg V per day. This is equivalent to an absorption of 1% of V entering the GI tract. The corresponding absorption values for patients taking 25 mg V was 0.32%, and for patients taking 50 mg V was 0.36%. This is consistent with values previously calculated of 1.1% with a range of 0.5 to 2.3%, after daily administration 25 to 125 mg of ammonium vanadyl tartrate in humans72. These estimates are minimum values owing to the fact that there may be a number of compartments accumulating V. If this is the case at a higher V level, when a larger absorption rate predominates, the V is simply being sequstered in deep compartments. This may partially explain the lack of a direct relationship between V serum concentrations and clinical responses reported here.

The V concentrations were similar in whole blood and serum in the 50 mg dose group. The AUC ratio of serum to whole blood was unity at the lower dose rate, but elevated to 1.65 at the 100 mg dose rate. This dose dependent change in the distribution of V from red cells to serum may partially explain the more than proportional increase in urinary excretion at the higher dose group.

There was no significant correlation between the concentration of V in serum and any of the three clinical responses evaluated, reduction in mean fasting glucose, or increased glucose sensitivity when measured by euglycemic clamp. A striking example of this can be seen in the data of patient 100V-6, who responded well for all three clinical variables, yet accumulated little V above his baseline levels (Figure 2). However, more patients did show improvement in the clinical variables assessed as the dose of V was increased. These data strongly imply that neither serum V levels, nor another compartment in equilibration with total serum V, is the effective compartment in gauging the clinical response to V. The regression analysis of these data support the observation that patients who respond best to V salts are those that are in poor control as indicated by a higher glycohemoglobin.

Fig. 2.

Time course for serum V concentration, urine vanadium clearance, and blood vanadium concentration in patients dosed with 50 mg vanadium. Patients were dosed for forty days with 50 mg V as vanadyl sulfate. A four-week pre-treatment period is followed by the forty-day dosing period and a sixteen-day washout. Serum V concentration (ng/ml, Panel A), urine V clearance (mg/24 hr, Panel B), and blood V concentration (ng/ml, Panel C) for five individual patients (▲) 50V-1, (■) 50V-2, (○) 50V-3, (◆) 50V-4, and (✕) 50V-5 are shown.

Factors that can influence the lack of correlation between serum V with clinical response may involve concentration related differences in the kintetics of absorption in the gastrointestinal tract and/or differences in equilibration among compartments critical for initiating the clinical response. The deviations from an ideal one compartment kinetic model have been described for drugs given in multiple doses and are well recognized73. For example, these deviations can be caused by dose dependent differences in drug volume of distribution or drug bioavailablility that can ultimately affect pharmacological response.

The V pool which is most relevant to its insulin-like properties remains elusive. There are a number of possible explanations for the lack of correlation of whole blood and serum V concentrations with the clinical effects on blood glucose. We know that hydrolytic and coordination chemistry of V in all of its oxidation states can create several different V pools. The site(s) of action for the response would likely require a specific active chemical form of V (ionization state, free vs complexed, etc.) as well as sufficient concentration to elicit the insulin like effect. The kinetics of accumulation and interaction of the active form of V at the target site(s) may be very different from the kinetics of total V serum or whole blood, and therefore may not be directly proportional to the measured total V concentration in the blood and serum at any given time. Experiments in yeast support the idea that there are no “free” metal ions within cells as with other metal ions such as copper74 and this is consistent with the recent studies showing a range of complexes forming in blood and serum upon administration of several vanadium compounds9, 11, 19, 31–35. The variable response to the metal salt VOSO4 may be due to free metal ions quickly binding to various ligands in the serum (such as serum proteins and specifically human transferrin). A series of in vitro studies with both salts and V complexes have shown complexation of the V ion in several oxidation states to the transferrin23, 24, 75, 76. Some controversy existed in the early studies because studies with BMOV resulted in an additional V signal53. This was initially interpreted as formation of a ternary complex, and that V indeed bound to transferrin with a coordinated ligand as the 1:1 complex77. Later studies showed in fact that this extra signal was due to excees protein and formation of uncomplexed vanadyl cation.77 However, since then alternative methods have been used to observe mixed ternary complexes formed from the salts or coordination complexes in the presence of proteins9, 11, 21, 23, 24, 31–35, 75, 76. Specifically, in vitro studies demonstrate formation of cis-VO(ma)2(human Transferrin),24 Other protein complexes form including complexes with human serum albumin such as cis-VO(ma)2(HSA) and immunoglobin such as cis-VO(ma)2(IgG). Although the V binds less tightly, complexes with all serum proteins studied form in vitro and have been observed using various methods including EPR spectroscopy21, 23, 24, 75, 76. Having these formation constants permits the calculation of the expected distribution of V complexes in blood and serum78 as well as generally predict overall what species exist in blood and serum79. Binding of V to membranes has also been well characterized in cells60, reverse micelles and other in vitro systems20, 64, 80. It is likely that V therapeutically administered to mammals as a salt or complex, would also bind to the membrane components and red blood cells of the cirulatory system7. Indeed recent studies have shown that BMOV and [VO2dipic]- complexes do exert effects similar to but also different than insulin on signal transduction systems81. In interpreting effects of vanadium administration in animals one must also remember biological variability. In a global gene expession study using wistar outbred diabetic rats, there were two distinct responses to oral treatment with VOSO4, one correlated with lowering diabetic hyperglycemia and one in which the diabetic hyperglycemia was not lowered82.

Differential V binding to ligands present in serum could affect its bioavailability. This could contribute to the variable effectiveness of V demonstrated when administered as a salt. Given the controlled chemistry of coordinated V complexes, total serum V might better correlate to clinical outcome if V were administered as a coordinated derivative with limited binding capacity to different ligands in serum. When VOSO4 was administered in the STZ diabetic rat model, there was no relationship of blood V concentration with plasma glucose levels, similar to our studies here with human diabetic patients; whereas the administration of the coordinated V compound bis(maltolato)oxovandium(IV), low plasma glucose tended to correlate with high blood V53. In that same study, differential binding to various serum proteins between the free and coordinated V compounds was observed.

Much of the work on coordinated metals have been done in vitro and used to predict the behaviour of these metal complexes in animals. Differential effects of ligands forming coordinated metal complexes have been observed in humans in studies using chelators to detoxify metal intoxication. Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) and dimercaptopropanol (BAL) have very different effects on the distribution and elimination of methylmercury. Whereas DMSA is a quite effective antidote causing a rapid elimination and low brain levels of the metal, BAL does not effectively eliminate methylmercury from the target organ, the brain83. Lead intoxication has been successful treated with oral administration of 2,3 dimercaptosuccinic acid since the 1980’s84.

At the doses of V used in this clinical study, subjects reported symptoms of gastrointestinal distress, although these symptoms were not severe enough to force any subjects to be dropped from the study. The gastrointestinal symptoms were managed with either Kaopectate or Immodium®. Adverse symptomology and toxicology issues52, 85must be considered and minimized for V compounds to be brought to market as viable treatment alternatives for diabetic patients. Undoubtedly a better understanding of the pharmacokinetics and bioavailability would assist in product development. Ideally studies would be carried out that reveal cellular V speciation, and with increasing development of analytical techniques, such studies may be possible.

5. CONCLUSIONS

V concentrations in blood, serum and urine were used to determine the pharmcokinetics of V accumulation and excretion in 16 type 2 diabetic patients given oral vanadyl sulfate. The patients absorbed about 1% of the administered V. Total serum V concentration did not have a significant relationship with clinical response, neither fasting blood glucose nor insulin sensitivity. These results imply that total serum V or any compartment in equilibruim with serum V are unlikely to be the site of the active V pool. We suggest that the coordination chemistry of V taking place during oral administration and distribution of V through the body allows the administered metal to be complexed with both small metabolites and macromolecules, mostly forming biological inactive complexes. The therapeutically active V complex may well exist in serum, however, the identity of that specific V pool still remains to be identified. The results reported here support the processing of V-ligand complexes involving ligand dissociation and coordinating chemistry with binding to metabolites, proteins or membranes.

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Patienta ID |

Age (yr) |

Sex | BMI (kg/m2) |

HbA1cb (%) |

Total Globulinb (g/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25V-1 | 59 | M | 26.0 | 10.4 | 2.1 |

| 25V-2 | 57 | F | 52.0 | 14.1 | 2.6 |

| 25V-3 | 57 | F | 38.6 | 8.8 | 3.2 |

| 50V-1 | 48 | M | 37.7 | 13.0 | 2.5 |

| 50V-2 | 51 | M | 27.4 | 7.8 | 2.4 |

| 50V-3 | 65 | M | 27.1 | 9.0 | 3.0 |

| 50V-4 | 58 | M | 39.3 | 7.4 | 2.9 |

| 50V-5 | 59 | M | 28.0 | 10.1 | 2.3 |

| 100V-1 | 54 | M | 48.7 | 10.8 | 2.6 |

| 100V-2 | 38 | M | 37.5 | 8.0 | 2.7 |

| 100V-3 | 65 | F | 32.5 | 7.8 | 2.8 |

| 100V-4 | 51 | F | 28.8 | 8.0 | 3.4 |

| 100V-5 | 52 | M | 27.1 | 7.6 | 2.4 |

| 100V-6 | 38 | M | 31.5 | 14.9 | 1.7 |

| 100V-7 | 43 | F | 22.0 | 7.4 | 2.8 |

| 100V-8 | 64 | M | 37.0 | 8.9 | 2.5 |

| Mean ± SD | 53 ± 8 | 33.8 ± 8.1 | 9.6 ± 2.4 | 2.6 ± 0.4 |

Numerics in patient ID (25, 50 and 100) refer to the dose of elemental V administered (mg).

The Hemoglobin and Globulin data reported are mean values at steady state. For 25V-2 and 100V-6 who never reached steady state, the value on the last day of dosing is reported.

TABLE 5.

Multiple Regression Analysis of Clinical Variables

| Response Variablea | Predictor Variableb | R2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LN Peak Serum V | −HbA1c | 0.38 | 0.009 |

| Clamp-High | +HbA1c | 0.39 | 0.010 |

| Fasting Blood Glucose | −Globulin and −HbA1c | 0.49 | 0.013 |

The response variables used were natural log peak serum vanadium (LN Peak Serum V), clamp-high, clamp-low, and fasting blood glucose. Clamp-High is a euglycemic-hyperinsulinnemic clamp using 1.0 mU insulin/kg/minute. A low euglycemic clamp (0.5 mU insulin/kg/minute) was also used but correlated to no predictor variables.

The predictor variables used were: Hematocrit, gravametric lipid, Body Mass Index, and serum levels of triglyceride, HDL, VLDL, globulin, serum albumin, total protein, glycohemoglobin (HbA1c) and LN Peak Serum V.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge technical assistance of Marian Pazik. DCC and GRW thank the American Diabetes Foundation and the General Medicine Institute at the National Institutes of Health for funding this work R01 GM40525. ABG greatfully acknowledges the mentorship of C. Ronald Kahn, MD and support from the National Institutes of Health RO1 DK47462-05 and General Clinical Research Center M01 RR-02635-15. GRW would like to acknowledge the contributions of Elizabeth Johns and Alexander Salloum to this study.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AUC

Area Under the Curve

- GFAAS

Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrometry

- LOD

Limit of Detection

- V

Vanadium

- VOSO4

vanadyl Sulfate

REFERENCES

- 1.Chasteen ND. Struc.t Bond. 1983;53:105–138. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vilas Boas LV, Costa Pessoa J. In: Compre. Coord. Chem. The Synthesis, Reactions, Properties & Applications of Coordination Compounds. Wilkinson G Sir, Gillard RD, McCleverty JA, editors. Vol. 3. New York: Pergamon Press; 1987. pp. 453–583. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willsky GR, Chi LH, Godzala M, 3rd, Kostyniak PJ, Smee JJ, Trujillo AM, Alfano JA, Ding W, Hu Z, Crans DC. Coord. chem. rev. 2011;255:2258–2269. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler A, Carrano CJ. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1991;109:61–105. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rehder D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1991;30:148–167. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crans DC, Smee JJ, Gaidamauskas E, Yang L. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:849–902. doi: 10.1021/cr020607t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson KH, Orvig C. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006;100:1925–1935. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakurai H, Yoshikawa Y, Yasui H. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:2383–2392. doi: 10.1039/b710347f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiss T, Jakusch T, Hollender D, Dornyei A, Enyedy EA, Pessoa JC, Sakurai H, Sanz-Medel A. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008;252:1153–1162. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrio DA, Etcheverry SB. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010;17:3632–3642. doi: 10.2174/092986710793213805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanna D, Biro L, Buglyo P, Micera G, Garribba E. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012;115:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson KH, Lichter J, LeBel C, Scaife MC, McNeill JH, Orvig C, Inorg J. Biochem. 2009;103:554–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crans DC, Trujillo A, Pharazyn P, Cohen M. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crans DC, Woll KA. Inorg. Chem. 2013 doi: 10.1021/ic4007873. submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lobinski R, Schaumloffel D, Szpunar J. Mass. Spectrom. Rev. 2006;25:255–289. doi: 10.1002/mas.20069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mounicou S, Szpunar J, Lobinski R. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:1119–1138. doi: 10.1039/b713633c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szpunar J. Analyst. 2005;130:442–465. doi: 10.1039/b418265k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metelo AM, Perez-Carro R, Castro MM, Lopez-Larrubia P. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012;115:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chasteen ND, Grady JK, Holloway CE. Inorg. Chem. 1986;25:2754–2760. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levina A, Lay PA. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:11675–11686. doi: 10.1039/c1dt10380f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiss E, Garribba E, Micera G, Kiss T, Sakurai H. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2000;78:97–108. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(99)00215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pessoa JC, Tomaz I. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010;17:3701–3738. doi: 10.2174/092986710793213742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanna D, Ugone V, Micera G, Garribba E. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:7304–7318. doi: 10.1039/c2dt12503j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanna D, Biro L, Buglyo P, Micera G, Garribba E. Metallomics. 2012;4:33–36. doi: 10.1039/c1mt00161b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cortizo AM, Bruzzone L, Molinuevo S, Etcheverry SB. Toxicology. 2000;147:89–99. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu L, Zhu M. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2011;11:164–171. doi: 10.2174/187152011794941271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner TL, Nguyen VH, McLauchlan CC, Dymon Z, Dorsey BM, Hooker JD, Jones MA. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012;108:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cannon JC, Chasteen ND. Biochemistry. 1975;14:4573–4577. doi: 10.1021/bi00692a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Setyawati IA, Thompson KH, Yuen VG, Sun Y, Battell M, Lyster DM, Vo C, Ruth TJ, Zeisler S, McNeill JH, Orvig C. J. Appl. Physiolog. 1998;84:569–575. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.2.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson KH, Liboiron BD, Sun Y, Bellman KDD, Setyawati IA, Patrick BO, Karunaratne V, Rawji G, Wheeler J, Sutton K, Bhanot S, Cassidy C, McNeill JH, Yuen VG, Orvig C. J. Biolog. Inorg. Chem. 2003;8:66–74. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jakusch T, Pessoa JC, Kiss T. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011;255:2218–2226. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jakusch T, Hollender D, Enyedy EA, Gonzalez CS, Montes-Bayon M, Sanz-Medel A, Costa Pessoa J, Tomaz I, Kiss T. Dalton Trans. 2009:2428–2437. doi: 10.1039/b817748a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanna D, Micera G, Garribba E. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:174–187. doi: 10.1021/ic9017213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanna D, Micera G, Garribba E. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:3717–3728. doi: 10.1021/ic200087p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiss T, Jakusch T, Gyurcsik B, Lakatos A, Enyedy EA, Sija E. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012;256:125–132. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reedijk J. Chem. Rev. 1999;99:2499–2510. doi: 10.1021/cr980422f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jungwirth U, Kowol CR, Keppler BK, Hartinger CG, Berger W, Heffeter P. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011;15:1085–1127. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rehder D, Pessoa JC, Geraldes C, Castro M, Kabanos T, Kiss T, Meier B, Micera G, Pettersson L, Rangel M, Salifoglou A, Turel I, Wang DR. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2002;7:384–396. doi: 10.1007/s00775-001-0311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hiromura M, Nakayama A, Adachi Y, Doi M, Sakurai H. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2007;12:1275–1287. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0295-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson KH, McNeill JH, Orvig C. Topics in Biolog. Inorg. Chem. 1999;2:139–158. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuen VG, Orvig C, McNeill JH. Can. J. Physiolog. Pharmacol. 1995;73:55–64. doi: 10.1139/y95-008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reul BA, Amin SS, Buchet JP, Ongemba LN, Crans DC, Brichard SM. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:467–477. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen N, Halberstam M, Shlimovich P, Chang CJ, Shamoon H, Rossetti L. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;95:2501–2509. doi: 10.1172/JCI117951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldfine AB, Patti ME, Zuberi L, Goldstein BJ, LeBlanc R, Landaker EJ, Jiang ZY, Willsky GR, Kahn CR. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2000;49:400–410. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(00)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boden G, Chen X, Ruiz J, van Rossum GD, Turco S. Metab. Clin. Exp. 1996;45:1130–1135. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(96)90013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cusi K, Cukier S, DeFronzo RA, Torres M, Puchulu FM, Redondo JC. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;86:1410–1417. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson KH, Orvig C. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2001:219–221. 1033–1053. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buglyo P, Crans DC, Nagy EM, Lindo RL, Yang LQ, Smee JJ, Jin WZ, Chi LH, Godzala ME, Willsky GR. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:5416–5427. doi: 10.1021/ic048331q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li M, Ding W, Smee JJ, Baruah B, Willsky GR, Crans DC. Biometals. 2009;22:895–905. doi: 10.1007/s10534-009-9241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li M, Smee JJ, Ding W, Crans DC. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009;103:585–589. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willsky GR, White DA, McCabe BC. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:13273–13281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Willsky GR, Goldfine AB, Kostyniak PJ. ACS Symposium Series. 1998;711:278–296. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willsky GR, Goldfine AB, Kostyniak PJ, McNeill JH, Yang LQ, Khan HR, Crans DC. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2001;85:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goldfine AB, Simonson DC, Folli F, Patti ME, Kahn CR. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995;80:3311–3320. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.11.7593444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harris WR, Friedman SB, Silberman D. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1984;20:157–169. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(84)80015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patterson BW, Hansard SL, 2nd, Ammerman CB, Henry PR, Zech LA, Fisher WR. Am. J. Physiol. 1986;251:R325–R332. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.251.2.R325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schroeder HA, Balassa JJ. J. Nutr. 1967;92:245–252. doi: 10.1093/jn/92.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Myron DR, Zimmerman TJ, Shuler TR, Klevay LM, Lee DE, Nielsen FH. Am. J. of Clin. Nutr. 1978;31:527–531. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/31.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sabbioni E, Marafante E, Amantini L, Ubertalli L, Birattari C. Bioinorg.Chem. 1978;8:503–515. doi: 10.1016/0006-3061(78)80004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang X, Wang K, Lu J, Crans DC. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003;237:103–111. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stroop SD, Helinek G, Greene HL. Clin. Chem. 1982;28:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gylseth B, Leira HL, Steinnes E, Thomassen Y. Scand J Work Environ. Health. 1979;5:188–194. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beliles RP. CODEN: 59YLA9 Conference; General Review written in English. CAN 125:255417 AN 1996:527747. In: Clayton GD, Clayton FE, editors. Patty's Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology. 4th edn. Pt. A. Vol. 2. Wiley, N. Y: N. Y. Publisher; 1993. pp. 25–75. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crans DC, Rithner CD, Baruah B, Gourley BL, Levinger NE. J Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:4437–4445. doi: 10.1021/ja0583721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fukui K, Fujisawa Y, OhyaNishiguchi H, Kamada H, Sakurai H. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1999;77:215–224. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(99)00204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Elvingson K, González Baró A, Pettersson L. Inorg. Chem. 1996;35:3388–3393. doi: 10.1021/ic951195s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Andersson I, Gorzsas A, Pettersson L. Dalton Trans. 2004:421–428. doi: 10.1039/b313424e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Crans DC, Yang LQ, Jakusch T, Kiss T. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:4409–4416. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gorzsas A, Getty K, Andersson I, Pettersson L. Dalton Trans. 2004:2873–2882. doi: 10.1039/B409429H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kiviluoto M, Pyy L, Pakarinen A. Scandinavian J. Work, Environ. Health. 1979;5:362–367. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kiviluoto M, Pyy L, Pakarinen A. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 1981;48:251–256. doi: 10.1007/BF00405612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dimond E, Caravaca J, Benchimol A. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1963;12:49–53. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/12.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wagner JG, Northam JI, Alway CD, Carpenter OS. Nature. 1965;207:1301–1302. doi: 10.1038/2071301a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rae TD, Schmidt PJ, Pufahl RA, Culotta VC, O'Halloran TV. Science. 1999;284:805–808. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sanna D, Buglyo P, Micera G, Garribba E. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2010;15:825–839. doi: 10.1007/s00775-010-0647-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sanna D, Garribba E, Micera G. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009;103:648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bordbar AK, Creagh AL, Mohammadi F, Haynes CA, Orvig C. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009;103:643–647. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liboiron BD, Thompson KH, Hanson GR, Lam E, Aebischer N, Orvig C. J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2005;127:5104–5115. doi: 10.1021/ja043944n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kiss T, Kiss E, Garribba E, Sakurai H. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2000;80:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Crans DC, Schoeberl S, Gaidamauskas E, Baruah B, Roess DA. J. Bio.l Inorg. Chem. 2011;16:961–972. doi: 10.1007/s00775-011-0796-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Winter PW, Al-Qatati A, Wolf-Ringwall AL, Schoeberl S, Chatterjee PB, Barisas BG, Roess DA, Crans DC. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:6419–6430. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30521f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Willsky GR, Chi LH, Liang Y, Gaile DP, Hu Z, Crans DC. Physiol. Genomics. 2006;26:192–201. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00196.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kostyniak PJ, Soiefer AI. J Appl. Toxicol. 1984;4:206–210. doi: 10.1002/jat.2550040409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Graziano JH, Siris ES, Loiacono N, Silverberg SJ, Turgeon L. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1985;37:431–438. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1985.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Thompson KH, Yuen VG, McNeill JH, Orvig C. ACS Symposium Series. 1998:329–343. [Google Scholar]