Abstract

Purpose

To develop a population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) model that characterizes the effects of major systemic corticosteroids on lymphocyte trafficking and responsiveness.

Materials and Methods

Single, presumably equivalent, doses of intravenous hydrocortisone (HC), dexamethasone (DEX), methylprednisolone (MPL), and oral prednisolone (PNL) were administered to five healthy male subjects in a five - way crossover, placebo - controlled study. Measurements included plasma drug and Cortisol concentrations, total lymphocyte counts, and whole blood lymphocyte proliferation (WBLP). Population data analysis was performed using a Monte Carlo-Parametric Expectation Maximization algorithm.

Results

The final indirect, multi-component, mechanism-based model well captured the circadian rhythm exhibited in Cortisol production and suppression, lymphocyte trafficking, and WBLP temporal profiles. In contrast to PK parameters, variability of drug concentrations producing 50% maximal immunosuppression (IC50) were larger between subjects (73–118%). The individual log-transformed reciprocal posterior Bayesian estimates of IC50 for ex vivo WBLP were highly correlated with those determined in vitro for the four drugs (r2 = 0.928).

Conclusions

The immunosuppressive dynamics of the four corticosteroids was well described by the population PK/PD model with the incorporation of inter-occasion variability for several model components. This study provides improvements in modeling systemic corticosteroid effects and demonstrates greater variability of system and dynamic parameters compared to pharmacokinetics.

Keywords: corticosteroids, mathematical modeling, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics

INTRODUCTION

Corticosteroids have pleiotropic effects and are extensively used to prevent or suppress inflammation and immunological related diseases. Their immunosuppressive effect forms the rationale for their use in the treatment of autoimmune diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus) as well as acute organ transplant rejection (1). Most effects of corticosteroids are mediated by genomic mechanisms, which may delay the time of onset and peak effects by several hours (2). Recent studies suggest that nongenomic mechanisms are also important, which are characterised by a rapid onset of effects (3). Thus, the net immunosuppressive effect of corticosteroids reflects the combination of rapid and delayed responses.

Mechanism-based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) models have been published for selected corticosteroids that describe rapid effects such as lymphocyte trafficking (4) and delayed effects such as whole blood lymphocyte proliferation (WBLP) (5). Based on the mechanism of action, lymphocyte immune responses can be well described using an indirect pharmacodynamic response model (6). In a previous analysis, we characterized and compared the immunosuppressive properties of four selected corticosteroids using a standard two stage analysis, showing that dose equivalency can be assessed using mechanistic indirect response models (7). However, PK/PD parameters were estimated as constant values across all occasions. A population PK/PD approach has been described to appropriately evaluate inter-occasion variability (IOV) (8).

The purpose of this study is to develop a population PK/PD model that characterizes the effects of major systemic corticosteroids on lymphocyte trafficking and immunoresponsiveness using an Monte Carlo-Parametric Expectation Maximization (MC-PEM) algorithm. An approach is presented that accounts for the modeling of interoccasion pharmacodynamic variability. The relationship between ex vivo and in vitro immunosuppressive potency is examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Bioassay

Details of the study design were described previously (7). Briefly, this was a randomized, five-way crossover study with placebo control. Single, equivalent doses of intravenous hydrocortisone (HC, hydrocortisone sodium succinate, Solu-Cortef®, Pharmacia), dexamethasone (DEX, dexamethasone phosphate, Decadron®, Merck), methylprednisolone (MPL, methylprednisolone sodium succinate, Solu-Medrol®, Pharmacia), and oral prednisolone (PNL, generic prednisolone tablets, Schein) were given to five healthy male subjects (ages 32.2±7.6 years and weights 73.6±10.7 kg). Each period was separated by a two-week washout. The average doses for HC, DEX, MPL, and PNL were 149, 5.7, 29, and 37 mg, which were stratified based on the total body weight of each subject as described by Mager et al. (7). Blood samples were collected at 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, 28, and 32 h after dosing during each study period. The study was approved by the Kaleida Health Millard Fillmore Hospital Institutional Review Board (Buffalo, NY), and written informed consent was obtained from all study subjects. Corticosteroid concentrations in plasma were measured using the normal phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) assay validated by Jusko et al. (9). The lower limit of quantitation was 10 ng/ml for all steroids, and intra- and inter-day coefficients of variation were less than 12%. Total lymphocyte cell count was obtained using an automated haemocytometer (CELL-DYN 1700, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) as described previously (10).

Whole Blood Lymphocyte Proliferation

The in vitro WBLP was determined by the assay developed by Ferron et al. (5). Blood samples collected at time zero were diluted 1:20 (v/v) with whole blood human complete medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 20 mM HEPES, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, 0.25 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). Diluted blood (165 µL) was plated in 96-well plates and the study drug (20 µL) was added to produce well concentrations ranging from 0.2 to 2,000 nM. Proliferation was induced by phytohemag-glutinin (PHA) at a final concentration of 3 µg/mL All samples were performed in quadruplicate in a total volume of 200 µL per well. After incubation for 72 h at 37°C in a 7.5% CO2-humidified air incubator, cultures were pulsed with 1 µCi of [3H]thymidine per well (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA) for an additional 20 h. The cells were then harvested onto microplates (Packard Instrument Company, Meriden, CT), washed with 3% hydrogen peroxide, dried and counted in liquid scintillation fluid (Microscint-20, Packard) in a Packard Top Count Microplate Scintillation Counter.

The ex vivo WBLP was performed using the blood collected at serial time points after the dosing of drug. The procedure is identical to the aforementioned in vitro method except for replacing 20 µL pulsing drug with the same volume of medium.

PK/PD Analysis

An integrated mechanism-based PK/PD model was proposed and is shown in Fig. 1. The model reflects circadian secretion of Cortisol suppressed by drug, and the joint inhibitory effect on lymphocyte trafficking and lymphocyte immune responses by endogenous Cortisol and exogenous corticosteroids. The pharmacokinetics of DEX, MPL, and PNL were characterised by one- and two- compartment mammillary models as previously described (7).

Fig. 1.

Mechanism-based pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic model of systemic corticosteroids. Symbols are defined in the text.

Pharmacodynamic Model

Cortisol Dynamics

Under normal physiological conditions, endogenous Cortisol concentrations (Cen) in the blood follow a circadian-episodic profile which can be described by a turnover model with a first-order elimination rate constant (kout), using the following differential equation:

| (1) |

where kin(t) is the Cortisol input function, which was defined as:

| (2) |

where an and bn are Fourier coefficients obtained by L2-norm approximation using FOURPHARM (11). The inhibitory effect of corticosteroids on Cortisol secretion can be characterized by an indirect response model as:

| (3) |

where Cp is the plasma concentration of exogenous corticosteroids, IC50 is the concentration of exogenous corticosteroid achieving 50% inhibition of Cortisol secretion, and S is the stimulation coefficient for PNL. The rate of change of exogenous HC concentrations is specified as:

| (4) |

Since exogenous hydrocortisone (Chc) and endogenous Cortisol are chemically identical, the total Cortisol concentration (Ct) following iv administration of HC is:

| (5) |

Lymphocyte Trafficking

Lymphocytes naturally equilibrate between blood and extravascular spaces (e.g., bone marrow, lymph node, and spleen). The movement of lymphocytes from peripheral tissues to blood can be inhibited by corticosteroids, which results in lymphocytopenia after treatment. The suppressive effect of corticosteroids on lymphocyte trafficking can be defined by an indirect response model which accounts for the joint effect of endogenous Cortisol and exogenous corticosteroids (12):

| (6) |

where L represents lymphocyte counts in the blood pool, kin,L is an apparent zero-order rate constant, IC50,C and IC50,GC reflect the endogenous Cortisol (Cen) and exogenous corticosteroid concentrations (Cp) that produce a 50% inhibition of maximal lymphocyte trafficking, and kbe is a first-order rate constant. The CP was fixed to 0 when the placebo data were analyzed. This same approach has been adopted by Stark and coworkers to describe the combined pharmacodynamic effects of budesonide and Cortisol on lymphocytes (13).

Ex vivo Whole Blood Lymphocyte Proliferation

The inhibitory effect of corticosteroids on ex vivo WBLP was modeled using (10):

| (7) |

where WBLPt is the extent of [3H] -thymidine incorporated by lymphocytes at time, t, post dose, which reflects ex vivo lymphocyte proliferative response, and is normalized by the corresponding value measured at predose (WBLP0); Lt and L0 are the lymphocyte count at time t and at pre-dose; DF is the dilution factor which is fixed to 0.05; Ca is the active corticosteroid concentration, which was introduced to account for the initial delay of lymphocyte responsiveness and was modeled by a linear transit compartment:

| (8) |

where kt is a first-order rate constant.

In vitro Whole Blood Lymphocyte Proliferation

The observed lymphocyte proliferative response in vitro (E) was calculated by:

| (9) |

where cpm is counts per minute. The subscripts D, N, and 0 denote counts after drug exposure, negative control (in absence of PHA and drug), and control (maximum counts without drug).

The inhibitory effect-concentration profile was modeled using a simple Imax model:

| (10) |

where E0 is 100%, Imax is maximum inhibitory effect on WBLP in vitro, Cp is the corticosteroid concentration, and IC50 represents the drug concentration producing 50% of maximum inhibition.

Modeling Inter-occasion Variability

A general approach for modeling IOV using an MC-PEM algorithm has been described (14). Denoting the ith subject’s base parameter value Pb,i and the deviation of jth occasion from subject’s base parameter ΔPij, the subject’s parameter value at the jth occasion Pij can be defined as:

| (11) |

The following mathematical functions were then specified to model Pb,i and ΔPij:

| (12) |

| (13) |

where is the typical value of Pb in the population, and ΔP̃j, defined as the typical value of ΔPj, is fixed to 1. Any off-diagonal variance terms among ΔPj are set to 0. Therefore, the population variance of base parameter Pb is defined as the inter-individual parameter variance. The population variance of ΔPj, when averaged by the number of occasions, creates a single inter-occasion variance for the parameter.

Data Analysis

PK/PD data were analyzed using the Monte Carlo-Parametric Expectation Maximization (MC-PEM) algorithm implemented in the S-ADAPT program (ver 1.51, http://bmsr.usc.edu/) (14).

The variance model was defined as:

| (14) |

where vari is the variance of the it h data point, σ1 and σ2 are the variance parameters with σ2 fixed to 2, and Y(θ, Ci) is the it h predicted value from the PK/PD model.

RESULTS

Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetic profiles for DEX, MPL, and PNL were best described by simple compartmental models and served as suitable driving functions for the pharmacodynamic model. Representative plasma concentration-time profiles are shown in Fig. 2, and the estimated pharmacokinetic parameters are listed in Table I. The final parameter estimates are in good agreement with those of previous studies (7,10), and the primary pharmacokinetic terms (CL and V) demonstrate low inter-individual variability (<27%).

Fig. 2.

Time course of observed (symbols) and individual predicted (solid lines) plasma corticosteroid concentrations after single doses of iv dexamethasone (6 mg), methylprednisolone (30 mg), and oral prednisolone (38 mg) in one representative subject.

Table I.

Population Pharmacokinetic Parameter Estimates for Corticosteroids

| Parameter a | Description | DEX |

MPL |

PNL |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meanb (%CV) |

IIVc (%CV) |

Mean (%CV) d |

IIV (%CV) |

Mean (%CV) |

IIV (%CV) |

||

| CL/F (L·hr−1) | Clearance | 18.1 (10.2) | 22.8 (62.9) | 22.8 (5.0) | 10.9 (60.6) | 19.7 (3.2) | 3.00 (96.0) |

| V/F (L) | Volume of Distribution | 41.6 (12.3) | 26.1 (62.3) | 78.4 (6.3) | 13.5 (61.8) | 76.6 (5.6) | 9.24 (77.1) |

| ka (hr−1) | Absorption Rate | —e | — | — | — | 2.58 (46.5) | 89.2 (81.0) |

| k12 (hr−1) | Distribution Rate | 1.09 (21.5) | 39.0 (60.5) | — | — | — | — |

| k21 (hr−1) | Distribution Rate | 1.02 (9.9) | 19.2 (63.7) | — | — | — | — |

| σ1 | Residual Variability | 0.0337 (20.7) | 0.0537 (16.2) | 0.479 (24.1) | |||

CL/F and V/F corrected for bioavailability F( F = 1 for iv DEX and MPL).

mean: population mean estimates.

IIV: inter-individual variability, expressed as percent of coefficient of variation.

%CV: percent coefficient of variation of the parameter estimate.

—: not applicable.

Cortisol Dynamics

Typical Cortisol concentration-time and model fitted profiles following treatment with HC, DEX, MPL, and PNL are shown in Fig. 3. Rapid Cortisol suppression was observed after drug administration. The baseline circadian rhythm resumed approximately 18 h after dosing of HC, MPL and PNL, whereas DEX persistently inhibited Cortisol secretion over 32 h.

Fig. 3.

Time course of observed (symbols) and individual predicted (solid lines) plasma Cortisol concentrations after single doses of iv hydrocortisone (150 mg), dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, and oral prednisolone in the same subject as shown in Fig. 2.

The population mean estimate for the volume of distribution of HC is 126 L, which is comparable to the value obtained in the previous study (115 L) (7). This estimate is considerably greater than that reported by Derendorf and colleagues (15); however, they administered 20 mg of HC following the suppression of endogenous Cortisol by DEX administration. The increased dose given in the present study coupled with the nonlinear plasma protein binding of Cortisol might result in an increase in the plasma free fraction of Cortisol and an increase in the apparent volume of distribution of this drug. The estimated pharmacodynamic parameters for Cortisol suppression are listed in Table II. The IC50 values for HC, DEX, and MPL are 5.52, 0.167, and 1.59 ng/mL The IC50 for PNL, when corrected for plasma free fraction (25%) (16), is 2.38 ng/mL, which is comparable with our previous estimate of 1.87 ng/mL (7). Prednisolone and Cortisol have been shown to compete for transcortin in a competitive and concentration-dependent fashion (17), which might account for the increase in the elimination rate of Cortisol. Therefore, a stimulation coefficient (S) was introduced to account for the increased Cortisol elimination in the presence of prednisolone and was estimated to be 0.0110 mL/ng. The population mean estimate of the Cortisol elimination rate constant (kout) was 0.3 h−1 and displayed 37.9% variability between occasions. The variability of IC50 for each of study drugs was large between subjects, ranging from 41 to 170%.

Table II.

Population Pharmacodynamic Parameter Estimates for Cortisol Suppression

| Parameter | Description | Mean (%CV) | IIV (%CV) | IOV a (%CV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcout (hr−1) | Cortisol Elimination Rate | 0.300 (12.2) | 12.8 (92.9) | 37.9 (37.2) |

| IC50C (ng/mL) | Cortisol Sensitivity Constant | 5.52 (25.4) | 41.1 (95.8) | — |

| IC50D (ng/mL) | DEX Sensitivity Constant | 0.167 (99.1) | 170 (70.2) | — |

| IC50M (ng/mL) | MPL Sensitivity Constant | 1.59 (50.2) | 77.3 (86.8) | — |

| IC50P (ng/mL) | PNL Sensitivity Constant | 9.54 (26.2) | 41.5 (104) | — |

| S (mL/ng) | PNL Stimulation Coefficient | 0.0110 (112) | 100 (81.9) | — |

| σ1 | Residual Variability | 0.344 (7.2) |

IOV: inter-occasion variability, expressed as percent of coefficient of variation.

Lymphocyte Trafficking

Total lymphocyte counts with model fitted curves after placebo and dosing of the four corticosteroids are shown in Fig. 4. The model well captured the lymphocyte circadian rhythms, which were out of phase with Cortisol profiles. After administration of the single doses, a transient lymphocytopenia in peripheral blood was induced, reaching its nadir at approximately 5 h post dose. The lymphocyte count resumed toward baseline conditions after about 20 h. Diagnostic plots revealed that there was good agreement between population predicted and individual observed values, and no systematic biases can be identified in the weighted residual plot (see “Supplementary Materials”).

Fig. 4.

Time course of observed (symbols) and individual predicted (solid lines) total lymphocyte counts after single doses of placebo, iv hydrocortisone, dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, and oral prednisolone in the same subject as shown in Figs. 2 and 3. Placebo profiles are represented by open circles and a dashed line

The pharmacodynamic parameters obtained from modeling are presented in Table III. The rank order of population mean estimates of IC50 for lymphocyte trafficking is DEX<MPL<PNL<HC (8.5, 19.6, 31.8, and 91.1 ng/mL). The inter-occasion variability of IC50 for Cortisol (IC50C) was estimated to be lower relative to its inter-individual variability (14.4 vs. 28.9%).

Table III.

Population Pharmacodynamic Parameter Estimates for Lymphocyte Trafficking

| Parameter | Description | Mean (%CV) | IIV (%CV) | IOV (%CV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kin,L (cell/µL/hr) | Lymphocyte Zero-order Rate | 1125 (17.1) | 35.0 (63.9) | 15.5 (29.2) |

| kbe (hr−1) | Lymphocyte Trafficking Rate | 0.283 (15.4) | 28.2 (72.5) | 6.4 (70.5) |

| IC50C (ng/mL) | Cortisol Sensitivity Constant | 91.1 (16.9) | 28.9 (74.4) | 14.4 (52.5) |

| IC50D (ng/mL) | DEX Sensitivity Constant | 8.5 (83.8) | 134 (71.2) | — |

| IC50M (ng/mL) | MPL Sensitivity Constant | 19.6 (30.7) | 77.5 (62.7) | — |

| IC50P (ng/mL) | PNL Sensitivity Constant | 31.8 (8.6) | 14.7 (79.0) | — |

| σ1 | Residual Variability | 0.134 (5.3) |

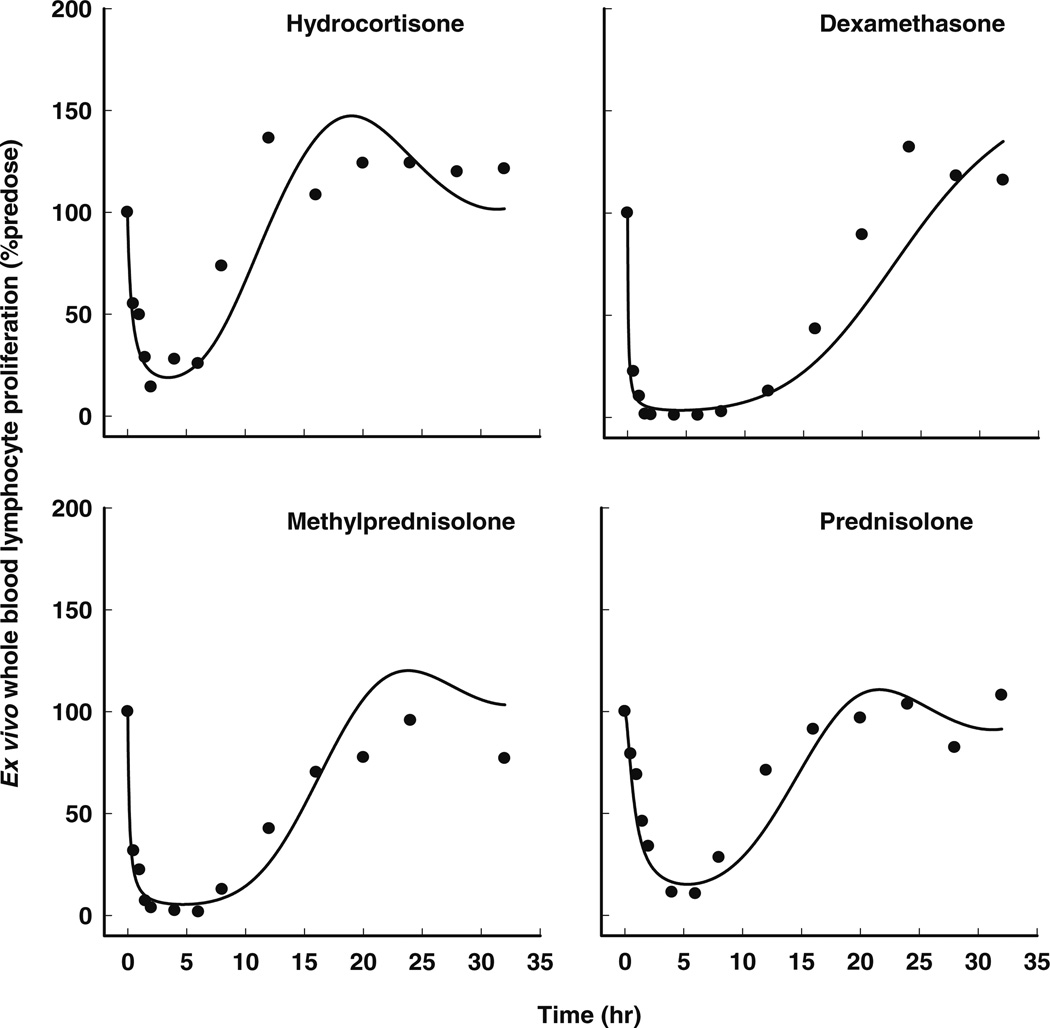

Whole Blood Lymphocyte Proliferation

The pharmacodynamic model for ex vivo WBLP includes a drug-induced suppression of both Cortisol and lymphocyte counts and a linear transduction delay of drug activity on lymphocyte proliferation (Fig. 1), and well captured the major features of the data (Fig. 5). The WBLP dynamics after the administration of HC and PNL were similar, with maximum suppression occurring at approximately 3 h post dose and a gradual recovery to pre-dose levels at around 16 h. In contrast, the extent of WBLP inhibition was more pronounced for MPL and DEX, where for the latter, complete inhibition lasted for up to 8 h. No systemic bias was observed in diagnostic plots (see “Supplementary Materials”).

Fig. 5.

Time course of observed (symbols) and individual predicted (solid lines) ex vivo whole blood lymphocyte proliferation after single doses of iv hydrocortisone, dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, and oral prednisolone in the same subject as shown in Figs. 2, 3 and 4.

The estimated pharmacodynamic parameters for ex vivo WBLP are summarized in Table IV. The population mean transit time (MTT) corresponding with the initial delay of immunoresponsiveness, is about 4.6 h (MTT = 1/kt). The population mean estimates of drug concentrations producing 50% maximal inhibition of ex vivo WBLP (IC50) has the same rank order as that for lymphocyte trafficking, with the lowest value of 0.112 ng/mL for DEX and the highest value of 4.72 ng/mL for HC. The variability of IC50 values was large between subjects, ranging from 73 to 118%.

Table IV.

Population Pharmacodynamic Parameter Estimates for Ex Vivo Whole Blood Lymphocyte Proliferation

| Parameter | Description | Mean (%CV) | IIV (%CV) | IOV (%CV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kt (hr−1) | First-order Transit Rate | 0.217 (40.6) | 79.3 (72.7) | 51.6 (44.0) |

| IC50C (ng/mL) | Cortisol Sensitivity Constant | 4.72 (49.1) | 104 (65.6) | — |

| IC50D (ng/mL) | DEX Sensitivity Constant | 0.112 (55.8) | 118 (64.5) | — |

| IC50M (ng/mL) | MPL Sensitivity Constant | 0.984 (33.6) | 73.2 (66.3) | — |

| IC50P (ng/mL) | PNL Sensitivity Constant | 3.93 (43.8) | 77.4 (72.0) | — |

| σ1 | Residual Variability | 0.537 (4.4) |

The in vitro immunosuppressive potency of corticosteroids demonstrated the same order as that for ex vivo WBLP. The population mean estimates of IC50 (%CV) for in vitro WBLP is 2.51 (41.7), 11.5 (17.3), 21.9 (20.9), and 51.8 (16.4) ng/mL for DEX, MPL, PNL, and HC. More importantly, it was found that the individual log-transformed posterior Bayesian estimates of drug potency for ex vivo WBLP were highly correlated with those determined in vitro (r2 = 0.928) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Correlation between log-transformed reciprocal individual posterior Bayesian estimates of drug potency (1/IC50) for ex vivo whole blood lymphocyte proliferation in subject 1(●), subject 2 (○), subject 3 (▲), subject 4 (△), and subject 5 (▽) and those determined in vitro (r2 = 0.928).

DISCUSSION

An integrated mechanistic population PK/PD model was developed that describes Cortisol dynamics, lymphocyte trafficking, and whole blood lymphocyte proliferation in humans treated with four systemic corticosteroids. The present study introduced several innovations in creating this multi-component model for jointly assessing the dynamics of the four drugs. The use of a stimulation coefficient in the Cortisol model to account for the protein-binding displacement properties of PNL permitted an assessment of the inter-occasion variability of the kout of Cortisol (Eq. 3). In the lymphocyte trafficking model, an interactive function was adapted to evaluate the joint effect of endogenous Cortisol and exogenous corticosteroids (Eq. 6). Furthermore, the explicit equation used to model ex vivo lymphocyte proliferation (Eq. 7) accounts for both alterations in Cortisol and cell trafficking caused by these drugs. Finally, it was necessary to account for a signal transduction delay (Eq. 8) for inhibition of lymphocyte proliferation. Our primary focus, however, was the simultaneous modeling of all study phases allowing examination of variability of system parameters.

The MC-PEM algorithm was selected to perform population analyses of the PK/PD data in this study. In contrast to the first-order approximation to the objective function values and maximum likelihood method implemented in NONMEM, MC-PEM estimates the parameter vector and variance matrix by randomly sampling over the entire parameter space and, therefore, is relatively more robust and efficient for analyzing population data with complex PK/PD models (14,18). The primary pharmacokinetic parameters (CL and V) for each study drug exhibited low inter-individual variability (3–26%). In contrast, inter-individual pharmacodynamic variability of ex vivo WBLP inhibition (IC50) was large (73–118%). Several mechanisms might contribute to the higher pharmacodynamic inter-individual variability. Firstly, inhibition of the T-lymphocyte induced immune response is the result of the joint effects of exogenous corticosteroids and endogenous Cortisol. Therefore, factors influencing Cortisol secretion may have an impact on lymphocyte responsiveness. Hon and coworkers investigated the pharmacodynamics of corticosteroids in healthy subjects with and without histamine N-methyltrans-ferase (HNMT) genetic polymorphism (19). Subjects with C/C genotype were more sensitive to corticosteroid inhibition of Cortisol secretion (i.e. lower IC50 values) than those carrying the C/T genotype. The authors postulated that this might be directly related to altered HNMT activity. Secondly, cytokines are essential co-factors for the lymphocyte proliferation reaction (20). Corticosteroids target the signal transduction pathway leading to interleukin-2 (IL-2) expression by inhibiting the nuclear translocation of transcription factors (e.g., nuclear factor-AT (NF-AT) and NF-κB) which are crucial to the induction of cytokines during T-cell activation (21). A recent study investigating the immunosuppressive capacity of cyclosporine revealed considerable interindividual variation in the expression of cytokine mRNA such as IL-2, IL-4, interferon-γ, and tumor necrosis factor-α (22). In contrast to the pronounced pharmacodynamic variability between subjects, the inter-occasion variability is estimated to be lower, which is reflected by minor fluctuation of individual posterior Bayesian parameter estimates across each study period (Fig. 7). This study result supports expectations in clinical pharmacology that pharmacodynamic variability in humans tends to be large but reproducible (23).

Fig. 7.

Individual posterior Bayesian parameter estimates for subject 1(●), subject 2 (○), subject 3 (▲), subject 4 (△), and subject 5 (▽) in each study period. PL represents the placebo control.

Population PK/PD analysis serves to quantify sources of inter- and intra-individual variability. When variability between study occasions is suspected, a common practice is to treat each occasion as a separate individual, which may bias the parameter estimation and inflate the interindividual variance (8). We therefore evaluated the effect of IOV on the estimation of population parameters and variances using S-ADAPT. Bias was detected in certain fixed-effect parameter estimates when IOV was not considered. The model with the inclusion of IOV estimated IC50C for Cortisol dynamic and lymphocyte trafficking to be 5.52 and 91.1 ng/mL compared to 7.22 and 81.2 ng/mL obtained from the model excluding IOV, whereas, the accuracy of these parameter estimates decreased when IOV was ignored (25 vs. 124% and 17 vs. 26% (CV%) for the IC50C estimates of Cortisol dynamics and lymphocyte trafficking). The effect of IOV modeling on the fixed-effect parameters is modest compared to its influence on the variance estimation. Ignoring IOV consistently inflated the estimated inter-individual pharmacodynamic variances. For example, the inter-individual variability of IC50C for Cortisol secretion and lymphocyte trafficking were 41 and 29% obtained from the model with IOV in contrast to those of 88 and 54% from the model without IOV. Therefore, dissecting IOV from the composite variability more accurately reflects the inter-individual variability in the population. The improvement in the post hoc individual fittings in Cortisol dynamics and lymphocyte trafficking and proliferation after the incorporation of IOV were evident by visual inspection.

A whole blood culture technique was used to evaluate lymphocyte immunodynamics owing to its simplicity with the fact that stimulating and suppressive factors for lymphocyte functions are maintained and that the microenvironment for lymphocytes is better preserved (24). There was a strong correlation between ex vivo and in vitro estimates of immunosuppressive potency, suggesting that in vitro WBLP might serve as an indirect measure of the in vivo immunosuppressive activity of corticosteroids. Interestingly, the ex vivo immunosuppressive potencies were approximately 10-fold greater than in vitro estimates (Fig. 6). The in vitro addition of corticosteroids to whole blood apparently does not reflect the biomolecular events occurring systemically following in vivo corticosteroid administration. T-lymphocyte responsiveness is the consequence of a cascade of events which includes phosphorylation of key signaling proteins and cytokine production (20,21). Corticosteroids may activate certain signaling pathways and/or cytokine induction/inhibition which are not likely present in an in vitro environment (25). In addition, the transient lymphocytopenia induced by in vivo administration of corticosteroids may play a role.

In conclusion, mechanism-based population PK/PD models were developed to describe the immunosuppressive dynamics of four major systemic corticosteroids utilizing an MC-PEM algorithm. Final models evaluated inter-occasion pharmacodynamic variability and results reflect a basic tenet of pharmacodynamics, namely that inter-individual PD variability tends to be large as compared to PK variability, but is reproducible. The strong correlation between in vitro and ex vivo immunosuppressive potency suggests that relative potency defined in vitro can be potentially used to predict the in vivo immunosuppressive activity of systemic corticosteroids.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Robert J. Bauer (XOMA LLC, Berkeley, CA), Dr. Olanrewaju Okusanya, and Dr. Alan Forrest (Department of Pharmacy Practice, University at Buffalo, SUNY) for their assistance with S-ADAPT, Dr. Sheren X. Lin and Dr. Christian D. Lates for their clinical support of our previous study, and Ms. Nancy Pyszczynski and Ms. Suzette Mis for providing technical assistance. This research was supported, in part, by NIH Grants GM24211 and GM57980 (to WJJ), new investigator support from the University at Buffalo, SUNY (to DEM), and the University at Buffalo-Pfizer Strategic Alliance Fellowship (for YH).

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11095-006-9232-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

REFERENCES

- 1.Czock D, Keller F, Rasche FM, Haussler U. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of systemically administered glucocorticoids. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:61–98. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newton R. Molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoid action: what is important? Thorax. 2000;55:603–613. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.7.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falkenstein E, Tillmann HC, Christ M, Feuring M, Wehling M. Multiple actions of steroid hormones—a focus on rapid, nongenomic effects. Pharmacol. Rev. 2000;52:513–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wald JA, Jusko WJ. Prednisolone pharmacodynamics: leukocyte trafficking in the rat. Life Sci. 1994;55:PL371–PL378. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00693-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferron GM, Jusko WJ. Species- and gender-related differences in cyclosporine/prednisolone/sirolimus interactions in whole blood lymphocyte proliferation assays. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;286:191–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dayneka NL, Garg V, Jusko WJ. Comparison of four basic models of indirect pharmacodynamic responses. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 1993;21:457–478. doi: 10.1007/BF01061691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mager DE, Lin SX, Blum RA, Lates CD, Jusko WJ. Dose equivalency evaluation of major corticosteroids: pharmacokinetics and cell trafficking and Cortisol dynamics. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2003;43:1216–1227. doi: 10.1177/0091270003258651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlsson MO, Sheiner LB. The importance of modeling interoccasion variability in population pharmacokinetic analyses. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 1993;21:735–750. doi: 10.1007/BF01113502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jusko WJ, Pyszczynski NA, Bushway MS, D’Ambrosio R, Mis SM. Fifteen years of operation of a high-performance liquid chromatographic assay for prednisolone, Cortisol and prednisone in plasma. J. Chromatogr. B, Biomed. Sciences and Appl. 1994;658:47–54. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(94)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magee MH, Blum RA, Lates CD, Jusko WJ. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model for prednisolone inhibition of whole blood lymphocyte proliferation. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002;53:474–484. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krzyzanski W, Chakraborty A, Jusko WJ. Algorithm for application of Fourier analysis for biorhythmic baselines of pharmacodynamic indirect response models. Chronobiol. Int. 2000;17:77–93. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100101034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milad MA, Ludwig EA, Anne S, Middleton E, Jr., Jusko WJ. Pharmacodynamic model for joint exogenous and endogenous corticosteroid suppression of lymphocyte trafficking. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 1994;22:469–480. doi: 10.1007/BF02353790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stark JG, Werner S, Homrighausen S, Tang Y, Krieg M, Derendorf H, Moellmann H, Hochhaus G. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling of total lymphocytes and selected subtypes after oral budesonide. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2006;33:441–459. doi: 10.1007/s10928-006-9013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauer RJ, Guzy S. Monte Carlo parametric expectation maximization (MCPEM) method for analyzing population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) data. In: D’Argenio DZ, D’Argenio DZ, editors. Advanced Methods of Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic System Analysis. Vol. 3. Boston, MA: Kluwer; 2004. pp. 135–163. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derendorf H, Mollmann H, Barth J, Mollmann C, Tunn S, Krieg M. Pharmacokinetics and oral biovailability of hydrocortisone. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1991;31:473–476. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1991.tb01906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mollmann H, Balbach S, Hochhaus G, Barth J, Derendorf H. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic correlations of corticosteroids. In: Derendorf H, Hochhaus G, editors. Handbook of Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic Correlation. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1995. pp. 323–361. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rocci ML, D’Ambrosio R, Jusko WJ. Prednisolone binding to albumin and transcortin in the presence of Cortisol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1982;31:289–292. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(82)90172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng CM, Joshi A, Dedrick RL, Garovoy MR, Bauer RJ. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic-efficacy analysis of efalizumab in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Pharma. Res. 2005;22:1088–1100. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-5642-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hon YY, Jusko WJ, Spratlin VE, Jann MW. Altered methylprednisolone pharmacodynamics in healthy subjects with histamine N-methyltransferase C314T genetic polymorphism. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2006;46:408–417. doi: 10.1177/0091270006286434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suni MA, Maino VC, Maecker HT. Ex vivo analysis of T-cell function. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2005;17:434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boumpas DT, Chrousos GP, Wilder RL, Cupps TR, Balow JE. Glucocorticoid therapy for immune-mediated diseases: basic and clinical correlates. Ann. Intern. Med. 1993;119:1198–1208. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-12-199312150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartel C, Hammers HJ, Schlenke P, Fricke L, Schumacher N, Kirchner H, Muller-Steinhardt M. Individual variability in cyclosporin A sensitivity: the assessment of functional measures on CD28-mediated costimulation of human whole blood T lymphocytes. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2003;23:91–99. doi: 10.1089/107999003321455480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy G. Predicting effective drug concentrations for individual patients. Determinants of pharmacodynamic variability. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1998;34:323–333. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199834040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fasanmade AA, Jusko WJ. Optimizing whole blood lymphocyte proliferation in the rat. J. Immunol. Methods. 1995;184:163–167. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00084-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang SR, Zweiman B. In vivo and in vitro effects of methylprednisolone on human lymphocyte proliferation. Immunopharmacology. 1980;2:95–101. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(80)90001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]