Abstract

Background

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) is the leading cause of death worldwide. The Global Burden of Diseases, Risk Factors and Injuries 2010 Study estimated global and regional IHD mortality from 1980 to 2010.

Methods and Results

Sources for IHD mortality estimates were country-level surveillance, verbal autopsy, and vital registration data. Regional income, metabolic and nutritional risk factors, and other covariates were estimated from surveys and a systematic review. An estimation and validation process led to an ensemble model of IHD mortality for 21 world regions. Globally, age-standardized IHD mortality has declined since the 1980s, and high-income regions (especially Australasia, Western Europe, and North America) experienced the most remarkable declines. Age-standardized IHD mortality increased in former Soviet Union countries and South Asia in the 1990s and attenuated after 2000. In 2010, Eastern Europe and Central Asia had the highest age-standardized IHD mortality rates. More IHD deaths occurred in South Asia in 2010 than in any other region. On average, IHD deaths in South Asia, North Africa and the Middle East, and sub-Saharan Africa occurred at younger ages in comparison with most other regions.

Conclusions

In most world regions, particularly in high-income regions, age-standardized IHD mortality rates have declined significantly since 1980. High age-standardized IHD mortality in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and South Asia point to the need to prevent and control established risk factors in those regions and to research the unique behavioral and environmental determinants of higher IHD mortality.

Keywords: epidemiology, mortality, myocardial ischemia, trends, world health

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) was the leading cause of death worldwide in 2010.1 Age-standardized IHD mortality has declined in high-income nations since 1980, in large part, because of a combination of improved primary prevention (improvements in risk factors) and improved secondary prevention (improved treatment of acute and chronic IHD).2–5 On average, IHD deaths have been pushed to older ages in the high-income regions. However, in the past, the IHD epidemic has evolved variably in different regions and nations.6 In some low- and middle-income regions, accelerated lifestyle changes, economic stresses, and other factors may be leading to increased IHD incidence often occurring in middle-aged adults, and changing the late 20th century paradigm of IHD as a disease of the affluent and the elderly.7

Measuring total IHD deaths and age-standardized IHD mortality rates is essential for assessing the burden of IHD and planning prevention programs. Global and regional analysis of IHD mortality trends is complicated by numerous factors, including changes in International Classification of Diseases (ICD) categories over time, sparse or low-quality original vital registration data in some regions, and variations in the degree of incorrect coding of IHD deaths. As part of the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors (GBD) 2010 Study, we used novel estimation methods to assess the numbers of IHD deaths, IHD mortality rates, and years of life lost (YLL) attributable to IHD for 21 world regions over the years 1980 to 2010, and provide uncertainty ranges for these estimates.

Methods

Definition of IHD Death

Detailed IHD mortality definitions and estimation methods are available elsewhere.8,9 In brief, IHD deaths fall into 2 categories: acute myocardial infarction deaths and sudden cardiac deaths. IHD has been consistently defined as an underlying cause of death across ICD revisions (most recently ICD-10 I20–I25 and ICD-9 410–414).8 A proportion of IHD deaths are erroneously assigned on death certificates to either nonfatal ICD conditions (eg, senility) or conditions not defined as an underlying cause of death (eg, heart failure, hypertension, or cardiac conduction disorders). The GBD developed methods for systematically reallocating these undefined or erroneously assigned deaths to IHD based on the total distribution of actual causes of death by the country, sex, age, and year.8,10

IHD Mortality Source Data

Cause-specific mortality data were gathered from vital registration, verbal autopsy, surveillance systems, surveys/censuses, or police report and aggregated in a central database. Data sources and availability varied substantially among GBD 2010 regions (Tables I and II in the online-only Data Supplement). Causes of death were mapped across revisions and national variations of the ICD over time, incomplete data were adjusted for reporting bias, erroneously coded deaths were redistributed, deaths were distributed to GBD age categories, and trends were smoothed to eliminate year-to-year fluctuations.1 No gold standard for validating GBD classification and redistribution algorithms exists (such as large-scale autopsy studies), so countries with the most complete vital registration and adherence to recommended cause-of-death coding practices were used as the standard. Even in the best of settings, there are problems with erroneous coding of deaths to inappropriate ICD codes, and GBD methods have been demonstrated to improve cause-of-death estimation.11 Overall, numbers of IHD deaths increased 21.5% after redistribution of undefined- coded deaths to IHD (Table III in the online-only Data Supplement). Globally, 76.9% of deaths incorrectly coded as heart failure, 47.2% incorrectly coded as hypertension, and 89.9% incorrectly coded as all cardiac conduction disorders were redistributed to IHD.9

IHD Mortality Models

Multilevel IHD mortality regression models were used to improve estimation for regions with sparse or outlying mortality data (Online- only Data Supplement Material). Models include fixed effects from covariates and nested random effects on super region, region, country, and age. Separate models were developed for males and females. Potential model covariates and their directions of effect were selected based on a comprehensive review by the comparative risk assessment arm of the GBD 2010 study, and included standard IHD risk factors (country mean blood pressure and cholesterol), behavioral variables (physical activity, diet, alcohol consumption), and contextual variables (per capita income, mean education level, and health system access).9 Independent ecological associations of covariates with IHD mortality were first tested in mixed-effects regressions, adding covariates stepwise, added in order from higher to lower evidence of causal association with IHD in past studies.9 Seventeen covariates produced multivariate coefficients with a plausible direction and were significant at the <0.05 level and were retained for subsequent models. With the use of IHD mortality data and the covariates selected, the Cause of Death Ensemble Model ranked outof-sample performance of individual IHD mortality statistical models and, with the use of a weighting algorithm, combined the best individual models into ensemble models.12 Out-of-sample predictive validity of the ensemble and individual predictive models were evaluated by ranking each model's root mean squared error of the natural log of the death rate (the average difference—or error—between model estimates and test set data for each year), the fraction of the time the trend in the prediction matched the temporal trend in the data (trend test), and the proportion of the test data set included in the 95% prediction interval of the model (coverage). All-cardiovascular death and total mortality envelopes were estimated independently and used to scale IHD mortality so that the sum of different cardiovascular disease–caused deaths would be equal to the all-cardiovascular disease death envelope, and all-cause deaths would be equal to the total mortality envelope.

Mean body mass index, systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), total cholesterol (mmol/L), and level of tobacco smoking (active smoking prevalence and mean cigarettes per day) were all significant predictors of IHD mortality and contributed most frequently to individual IHD models developed for both men and women.9 Alcohol (liters per capita) was the only covariate entered into models without specifying the direction of association (ie, not specifying benefit or harm) and contributed to 11% of male models and 42% of female models. Contextual covariates such as lower educational status (years per capita), lower income (US dollars per capita), high elevation (percentage of population dwelling at >1500 m), and high war deaths (rate per 1000 person-years) all contributed more to female than to male ensemble models.9 The prevalence of diabetes mellitus contributed to 30% of male ensemble models, but to zero female models. The root mean squared error of the best male IHD mortality model was 0.58, predicted the correct trend 62% of the time in test data, and included 90% of test data within the 95% confidence intervals around annual estimates. The best female model had a root mean squared error of 0.65, predicted the correct trend 61% of the time in test data sets, and included 91% of the test data within the 95% confidence interval.9

YLL were calculated by multiplying observed IHD deaths for a specific age in the year of interest by the age-specific reference life expectancy estimated by the use of life table methods (eg, 86.0 years at birth).13 Numbers of IHD deaths and YLL attributable to IHD death are reported for all 21 GBD regions for the years 1980 to 2010 (regions listed in Table IV in the online-only Data Supplement). Crude IHD mortality rates were calculated by dividing annual IHD deaths by the total population (all ages) at risk in that year. These rates were also age standardized by the direct method by using the 5-year GBD age categories and the World Health Organization standard population.14 To assist with interpretation, IHD mortality rate trend plots used 7 super regions: Latin America/Caribbean, East Asia/ Pacific, South Asia, North Africa/Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe/Central Asia, and High Income (Table IV in the online-only Data Supplement).

Results

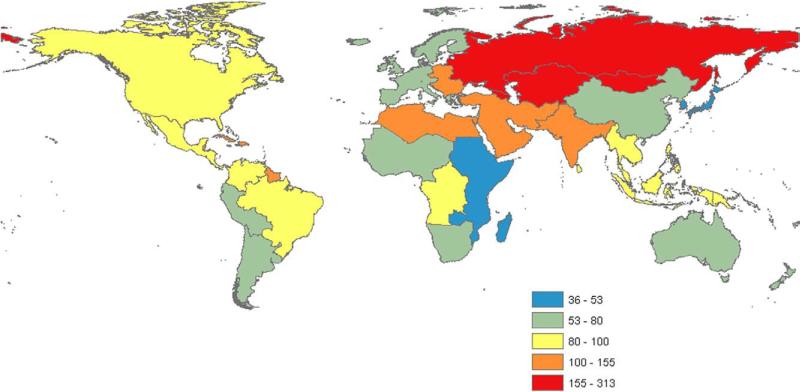

There were >7.0 million IHD deaths worldwide in 2010, in comparison with 4.5 million IHD deaths in 1980, 5.2 million in 1990, and 6.3 million in 2000 (Table V in the online-only Data Supplement). In 2010, the highest age-standardized IHD death rates were concentrated in a cluster of regions extending from Eastern Europe and Central Asia to Central Europe, North Africa/Middle East, and South Asia (Figure 1). High age-standardized IHD death rates were also found in the Caribbean region. Of all global IHD deaths in the year 2010, 25.6% occurred in persons <65 years of age (95% confidence interval, 25.9%–27.8%), in comparison with 26.5% in 1980 (95% confidence interval, 23.9%–26.6%).

Figure 1.

Map of age-standardized ischemic heart disease mortality rate per 100 000 persons in 21 world regions, 2010, the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study.

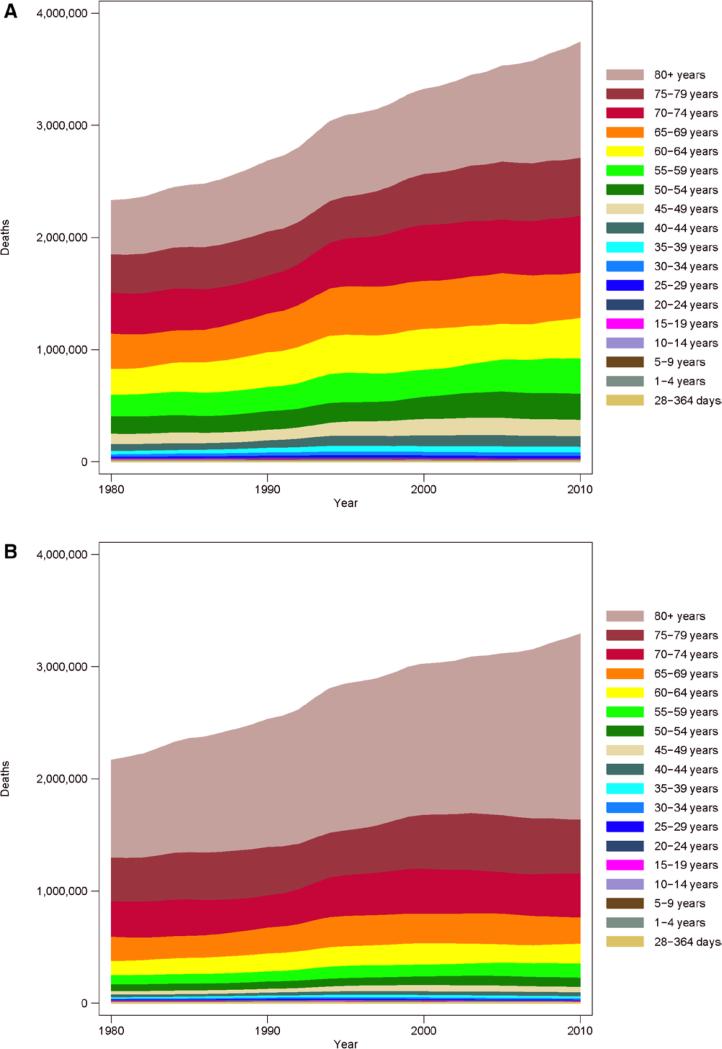

The number of IHD deaths increased most since 1980 in the ≥80-years age group, the same group in which about half of all female IHD deaths occurred in 2010 (Figure 2). Rarely, IHD deaths were recorded in infants and children, perhaps because of incorrect cause-of-death reporting. Crude IHD mortality rates in the High Income super regions were among the highest in the world in 1980, but declined substantially by 2005 (Figure I in the online-only Data Supplement). By far the highest crude rates of IHD deaths and the steepest increase since 1980 were observed in the regions of the former Soviet Union (Eastern Europe/Central Asia), especially among males. The South Asia and East Asia/Pacific super regions also saw steady crude IHD death rate increases after 1980.

Figure 2.

Total IHD deaths by age group, all world regions (A, males; B, females), 1980 to 2010, the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. IHD indicates ischemic heart disease.

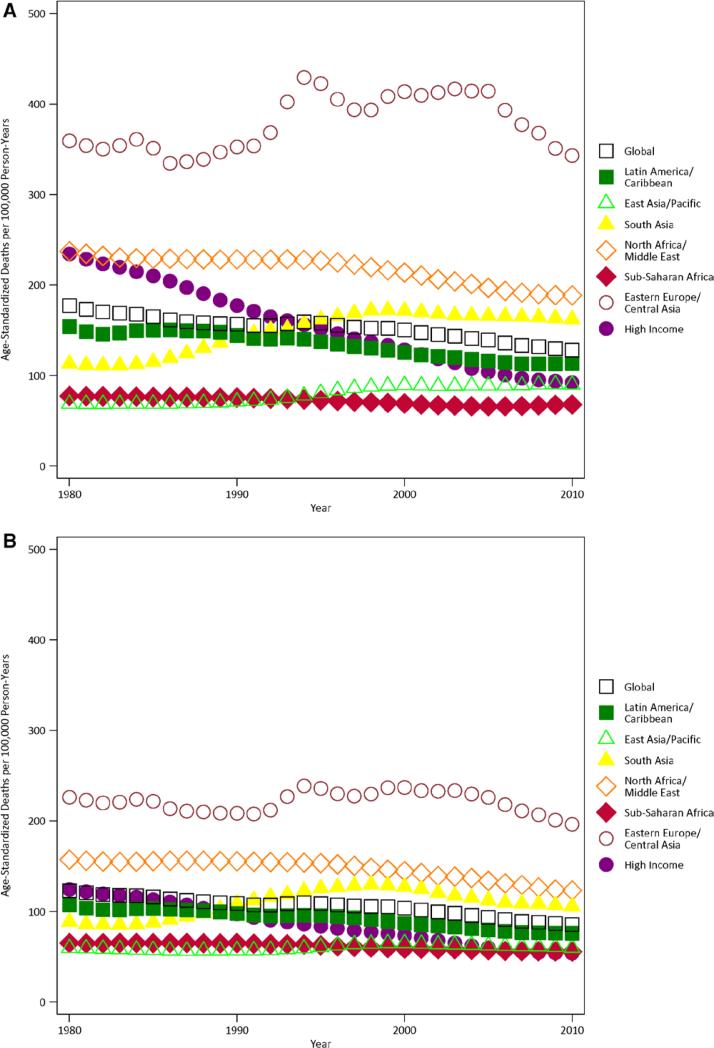

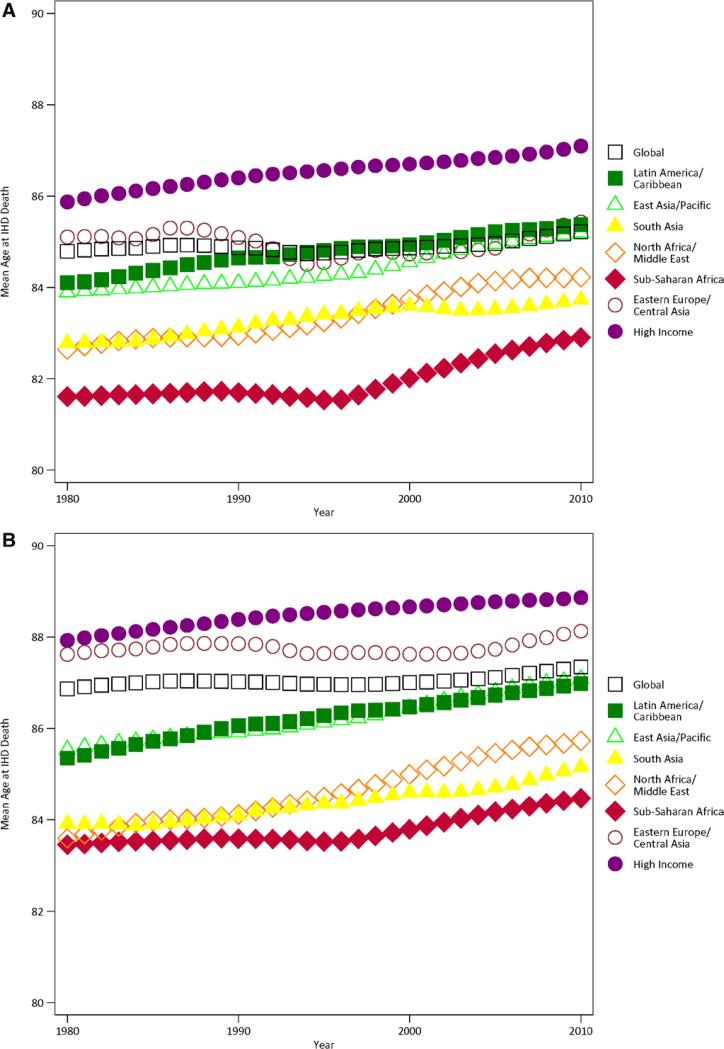

When mortality rates were age standardized, in comparison with the crude rates, IHD death rates emerged as distinctly higher in North Africa/Middle East and South Asia, 2 regions with younger populations (average age <65 years; Tables 1 and 2, Figure 3). South Asia's age-standardized death rates increased from ≈1985 to 2000; more recently rates there appear to have leveled off. Age-standardized IHD mortality remained low in sub-Saharan Africa from 1980 to 2010. The largest proportional increase in age-standardized IHD mortality between 1990 and 2010 occurred in East Asian males (38% increase), although the absolute rate remained comparatively low. On average, IHD deaths occurred at the youngest ages in North Africa/Middle East, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 4).

Table 1.

Age-Standardized IHD Mortality per 100 000 persons, by Region, Males, 1990, 2005, 2010, the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study

| GBD 2010 Super Region |

Males |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 |

2005 |

2010 |

|||||||

| GBD 2010 Region | Mean | Lower | Upper | Mean | Lower | Upper | Mean | Lower | Upper |

| High income | |||||||||

| Asia Pacific, high income | 69 | 60 | 73 | 49 | 45 | 56 | 46 | 42 | 52 |

| Europe, Western | 183 | 169 | 192 | 106 | 103 | 122 | 93 | 89 | 108 |

| Australasia | 209 | 190 | 216 | 99 | 94 | 116 | 91 | 83 | 108 |

| North America, high income | 226 | 209 | 238 | 135 | 129 | 155 | 120 | 112 | 139 |

| Latin America, Southern | 164 | 154 | 180 | 119 | 113 | 138 | 108 | 102 | 125 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | |||||||||

| Europe, Central | 285 | 263 | 302 | 226 | 215 | 246 | 201 | 192 | 222 |

| Europe, Eastern | 393 | 380 | 430 | 545 | 497 | 566 | 434 | 396 | 454 |

| Asia, Central | 395 | 382 | 427 | 441 | 411 | 459 | 400 | 366 | 430 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | |||||||||

| Latin America, Tropical | 159 | 142 | 170 | 119 | 113 | 139 | 113 | 106 | 132 |

| Latin America, Central | 130 | 121 | 144 | 115 | 101 | 120 | 117 | 103 | 124 |

| Latin America, Andean | 92 | 85 | 102 | 73 | 66 | 80 | 70 | 63 | 78 |

| Caribbean | 177 | 163 | 189 | 149 | 144 | 168 | 144 | 137 | 162 |

| East Asia/Pacific | |||||||||

| Asia, Southeast | 110 | 102 | 124 | 108 | 102 | 132 | 111 | 104 | 133 |

| Asia, East | 61 | 53 | 86 | 83 | 67 | 91 | 84 | 65 | 92 |

| Oceania | 122 | 106 | 185 | 117 | 101 | 179 | 115 | 98 | 168 |

| North Africa / Middle East | |||||||||

| North Africa / Middle East | 228 | 217 | 263 | 197 | 183 | 214 | 189 | 171 | 204 |

| South Asia | |||||||||

| Asia, South | 143 | 133 | 165 | 166 | 137 | 178 | 162 | 133 | 186 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | |||||||||

| Sub-Saharan Africa, Southern | 122 | 93 | 134 | 76 | 69 | 96 | 77 | 68 | 96 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa, East | 79 | 65 | 87 | 61 | 55 | 76 | 60 | 54 | 77 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa, Central | 112 | 84 | 134 | 103 | 84 | 124 | 112 | 91 | 135 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa, West | 52 | 47 | 69 | 60 | 54 | 73 | 63 | 56 | 77 |

GBD indicates Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors; and IHD, ishemic heart disease.

Table 2.

Age-Standardized IHD Mortality per 100 000 Persons, by Region, Females, 1990, 2005, 2010, the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study

| GBD 2010 Super Region |

Females |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 |

2005 |

2010 |

|||||||

| GBD 2010 Region | Mean | Lower | Upper | Mean | Lower | Upper | Mean | Lower | Upper |

| High income | |||||||||

| Asia Pacific, high income | 44 | 38 | 46 | 28 | 26 | 33 | 27 | 24 | 31 |

| Europe, Western | 96 | 85 | 99 | 58 | 56 | 71 | 51 | 49 | 65 |

| Australasia | 113 | 99 | 118 | 58 | 53 | 75 | 55 | 49 | 69 |

| North America, high income | 126 | 111 | 131 | 83 | 77 | 107 | 76 | 68 | 100 |

| Latin America, Southern | 84 | 78 | 90 | 62 | 59 | 76 | 58 | 54 | 70 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | |||||||||

| Europe, Central | 161 | 154 | 169 | 131 | 123 | 139 | 117 | 110 | 125 |

| Europe, Eastern | 224 | 216 | 246 | 272 | 245 | 284 | 235 | 209 | 245 |

| Asia, Central | 243 | 238 | 262 | 254 | 241 | 265 | 225 | 213 | 242 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | |||||||||

| Latin America, Tropical | 105 | 95 | 111 | 78 | 73 | 91 | 73 | 68 | 88 |

| Latin America, Central | 86 | 79 | 94 | 77 | 69 | 82 | 74 | 68 | 82 |

| Latin America, Andean | 72 | 63 | 80 | 60 | 54 | 69 | 55 | 49 | 64 |

| Caribbean | 133 | 122 | 139 | 116 | 111 | 133 | 112 | 105 | 150 |

| East Asia/Pacific | |||||||||

| Asia, Southeast | 76 | 69 | 84 | 70 | 65 | 90 | 68 | 63 | 86 |

| Asia, East | 52 | 46 | 79 | 60 | 45 | 65 | 57 | 40 | 65 |

| Oceania | 79 | 57 | 137 | 86 | 63 | 140 | 87 | 63 | 137 |

| North Africa / Middle East | |||||||||

| North Africa / Middle East | 155 | 148 | 173 | 134 | 123 | 143 | 123 | 114 | 131 |

| South Asia | |||||||||

| Asia, South | 109 | 98 | 131 | 112 | 89 | 124 | 106 | 86 | 120 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | |||||||||

| Sub-Saharan Africa, Southern | 74 | 55 | 83 | 57 | 49 | 76 | 52 | 43 | 72 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa, East | 59 | 45 | 65 | 49 | 42 | 55 | 47 | 41 | 55 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa, Central | 86 | 67 | 104 | 80 | 65 | 96 | 83 | 68 | 100 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa, West | 62 | 53 | 79 | 59 | 49 | 75 | 59 | 49 | 77 |

GBD indicates Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors; and IHD, ishemic heart disease.

Figure 3.

Age-standardized ischemic heart disease mortality rate per 100 000 persons by super region and globally (A, males; B, females), 1980 to 2010, the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study.

Figure 4.

Average age at the time of IHD death by super region and globally (A, males; B, females), 1980 to 2010, the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. IHD indicates ischemic heart disease.

Eastern Europe/Central Asia experienced steep increases in the age-standardized IHD death rate after 1990 (around the time of the breakup of the Soviet Union); age-standardized rates there declined starting in the mid-2000s (Figure 3).

Among the high-income regions, age-standardized IHD mortality rates decreased most in Australasia (≈51% decrease from 1990 to 2010), Western Europe (46% decrease), and North America (43% decrease; Tables 1 and 2). The lowest age-standardized IHD mortality rates over the period 1980 to 2010 were observed in the sub-Saharan Africa, Andean Latin America, and Asia/Pacific regions.

Regional totals of YLL attributable to IHD were highest in regions with larger populations, high IHD mortality rates, and younger average age at IHD death. The highest YLL in all years was observed in South Asia (a 72% increase since 1990), followed by Eastern Europe (Table 3, Table VI in the online-only Data Supplement). Despite having among the lowest IHD death rates in the world, East Asia ranked third in IHD YLL in 2010 and has experienced the largest proportional increase in YLL since 1990 (78% higher) because of its large and aging population. Driven both by lower IHD death rates and older average age at IHD death, the most remarkable decreases in YLL from 1990 to 2010 occurred in the high-income regions of Australasia (34% decrease) and Western Europe (32% decrease).

Table 3.

Years of Life Lost Owing to IHD, Males And Females, by Region, 1990, 2005, and 2010, the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study

| GBD 2010 Super Region |

1990 |

2005 |

2010 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBD 2010 Region | Mean | Lower | Upper | Mean | Lower | Upper | Mean | Lower | Upper |

| High income | |||||||||

| Asia Pacific, high income | 1 798146 | 1 620 244 | 1 900 184 | 1 812 636 | 1 692 038 | 2 018 899 | 1 920 451 | 1 752 565 | 2 116 832 |

| Europe, Western | 12860688 | 11929 341 | 13 404 064 | 8 807 634 | 8 566 677 | 9 942 095 | 8 428 017 | 8 135 515 | 9 554 209 |

| Australasia | 615 515 | 569 455 | 632 471 | 405 899 | 388 773 | 462 917 | 419 557 | 392 876 | 482 962 |

| North America, high income | 9 769 603 | 9 109 634 | 10 256 781 | 8 060 007 | 7 735 522 | 9 068 844 | 7 825 615 | 7 351 893 | 8 948 068 |

| Latin America, Southern | 952 977 | 904 836 | 1 037 283 | 933 315 | 898 505 | 1 032 393 | 945 652 | 905 779 | 1 055 796 |

| Eastern Europe/Central Asia | |||||||||

| Europe, Central | 5 597 369 | 5 242 998 | 5 831 784 | 5 089 778 | 4 920 576 | 5 468 643 | 4 835 548 | 4 650 986 | 5 210 929 |

| Europe, Eastern | 13 363 422 | 13 020 191 | 14 332 364 | 21 395 103 | 19 746 998 | 22 075 817 | 17 671 525 | 16 219 642 | 18 315 709 |

| Asia, Central | 2 434 441 | 2 366 917 | 2 603 885 | 3 358 046 | 3 149 985 | 3 497 223 | 3 344 003 | 3 095 362 | 3 565 863 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | |||||||||

| Latin America, Tropical | 2 341 808 | 2 193 945 | 2 534 789 | 2 779 536 | 2 657 763 | 3 083 571 | 3 015 732 | 2 872 578 | 3 380 191 |

| Latin America, Central | 1 762 410 | 1 637 594 | 1 905 648 | 2 366 529 | 2 129 444 | 2 484 887 | 2 827 557 | 2 550 462 | 3 012 726 |

| Latin America, Andean | 312 129 | 293 583 | 351 584 | 426 970 | 358 663 | 456 209 | 437 785 | 377 164 | 474 416 |

| Caribbean | 694 309 | 647 297 | 739 747 | 759 499 | 733 454 | 832 392 | 839 991 | 797 218 | 1 046 637 |

| East Asia/Pacific | |||||||||

| Asia, Southeast | 4 818 933 | 4 360 138 | 5 246 287 | 6 704 804 | 6 383 138 | 7 672 710 | 7 765 379 | 7 361 080 | 8 864 297 |

| Asia, East | 9 449 260 | 8 689 819 | 12 168 368 | 15 493 412 | 13 436 409 | 16 405 168 | 16 795 598 | 13 989 156 | 17 913 060 |

| Oceania | 71 723 | 61 923 | 98 564 | 107 351 | 90 631 | 150 617 | 122 337 | 102 152 | 165 558 |

| North Africa / Middle East | |||||||||

| North Africa / Middle East | 6 521 855 | 6 049 947 | 7 091 033 | 7 995 777 | 7 402 525 | 8 517 971 | 8 822 768 | 7 968 594 | 9 343 464 |

| South Asia | |||||||||

| Asia, South | 17 300 420 | 16 157 871 | 19 323 777 | 27 628 587 | 23 082 187 | 29 334 998 | 29 759 902 | 24 854 218 | 33 295 998 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | |||||||||

| Sub-Saharan Africa, Southern | 439 982 | 351 244 | 477 998 | 531 476 | 491 026 | 653 461 | 514 823 | 468 185 | 632 563 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa, East | 1 414 599 | 1 148 746 | 1 545 838 | 1 628 544 | 1 446 234 | 1 803 904 | 1 781 311 | 1 600 930 | 2 000 006 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa, Central | 508 418 | 404 775 | 597 259 | 666 283 | 576 079 | 770 551 | 805 163 | 697 096 | 940 718 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa, West | 1 492 723 | 1 274 743 | 1 714 206 | 1 890 019 | 1 683 958 | 2 126 861 | 2 146 457 | 1 913 551 | 2 462 752 |

GBD indicates Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors; and IHD, ishemic heart disease.

Discussion

In the overall GBD study, IHD was the leading cause of death worldwide in 2010.1 Our analysis of IHD mortality trends found that global age-standardized IHD mortality has declined since 1980. At the regional level, another, more complex story emerged: the age-standardized IHD death rate has declined steeply since 1980 in the Western, high-income regions, but has increased in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, South Asia, and East Asia. Reflecting its large population and relatively young average age at IHD death, the South Asia region had the highest number of life-years lost to premature IHD deaths.

An IHD epidemic emerged in Eastern Europe and Central Asia after the breakup of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s: this group of regions has had by far the highest crude and age- standardized IHD death rates of any region. Eastern Europe and Central Asia regions experienced a combined 21 million YLL in 2010 because of IHD, second only to South Asia, despite having less than a fifth of South Asia's population. The reasons for high IHD death rates in the Eastern Europe region are under debate: peak IHD death-rate years have coincided with economic downturns, and the greatest fluctuations have occurred in the nonmyocardial infarction (ie, cardiac arrest, atherosclerotic heart disease, and other IHD) portion of IHD deaths.15 There is strong evidence that heavy alcohol exposure is the cause of many deaths ascribed to IHD in this region, although the causal pathway needs to be better defined.15,16

Perhaps most concerning are high age-standardized IHD death rates in regions like North Africa/Middle East and South Asia where deaths occurred at younger ages on average, meaning IHD deaths were more likely to occur in productive, working-age adults. This represents the greatest loss for families and national economies.7,17 In the overall GBD 2010 study, regions such as South, Central, and East Asia; Central, Andean, and Tropical Latin America; and North Africa/Middle East stood out for having a double burden of YLL owing to cardiovascular and infectious diseases.

Dietary patterns have shifted worldwide in both high-and low-income regions to more consumption of edible oils, animal fats, and sugar-sweetened beverages.18 Earlier adoption of unhealthy lifestyles and higher risk factor exposures at younger ages may, in part, explain the increasing incidence of IHD at younger ages in regions like South Asia.19,20 East Asia (composed mostly of China) was another region with an IHD mortality increase in our analysis: in an earlier GBD study analysis of cholesterol trends, East Asia was among the few regions that experienced an increase in mean cholesterol after 1980.21 However, not all IHD epidemics are the same; there are past examples of IHD mortality declines in the face of adverse cholesterol or tobacco trends.22 Our analysis shows that, at a global level, traditional risk factors like tobacco smoke, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure play a central role in explaining regional differences in IHD mortality rates. Because no causal direction was specified and patterns of alcohol use were not distinguished (ie, binge or heavy compared with moderate alcohol consumption), our analysis did not accurately characterize the association of alcohol consumption with IHD. Regional air pollution level was not a significant covariate in the IHD mortality models, but epidemiological research has established air pollution as a risk factor for IHD,23 and its contribution will be explored in subsequent GBD analyses.

The association of lower regional economic and educational status with higher IHD rates suggests that many regions are undergoing an epidemiological transition to higher IHD death rates often associated with economic development. The populations of many of the transitioning regions (eg, South and East Asia, Latin America/Tropical [Brazil], and North Africa/Middle East) are enormous, and the continued development of these regions depends in part on successfully addressing the threat of cardiovascular disease. To succeed in stemming the tide of IHD mortality in younger adults in the 21st century, as many high-income regions did during the last decades of the 20th century, low- and middle-income regions may need to develop new approaches, emphasizing improved healthcare delivery infrastructure, universal health insurance and affordable essential medicines, and selected population- wide prevention interventions.24,25 Along with the public health community's emphasis on prevention, the impact of improved access to acute cardiac care should not be forgotten. Aspirin and a β-blocker for all acute myocardial infarctions and revascularization using low-cost thrombolytic for ST-elevation myocardial infarctions are often life-saving and may be affordable in low-resource settings.26

The strengths of this analysis of global trends in IHD mortality were the collection of a comprehensive set of national mortality data from a variety of sources, adjustments for biases introduced by ICD version changes and for death registration coding practices, and methods for accounting for and describing covariate parameter and statistical model selection uncertainty. Limitations of the analysis include incomplete data for many regions, especially sub-Saharan Africa, and the ecological nature of the associations found between covariates and IHD mortality. Unexpectedly, diabetes mellitus contributed more to male models than to female models, findings that may be explained by the inclusion of nontraditional IHD predictor covariates in the models that absorbed some of these covariates’ effects, or differential competing risk with other causes of death in males in comparison with females.

Implications

The decline in IHD mortality in high-income regions since 1980 is a success story. More troubling are the very high IHD mortality rates in Eastern Europe and Central Asia in 2010, and increased IHD mortality occurring in relatively young adults in South Asia. IHD prevention in the 21st century must extend the control of established risk factors from high- income to low- and middle-income regions while addressing newer social and behavioral determinants of IHD mortality observed in developing regions.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) leads to lost life-years and disability in high-, middle-, and lower-income regions and is the world's leading cause of death. Monitoring the trends in IHD mortality in diverse world regions requires analyzing a variety of data sources and using statistical modeling that accounts for sparse data in some regions. The Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study estimated IHD mortality in 21 world regions. Since 1980, age-standardized IHD mortality has declined in most world regions, particularly high-income regions. During the same period, age-standardized IHD mortality increased in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and South Asia. When estimated by using a standard method, age-standardized IHD mortality has trended favorably in most regions since 1980, but unfavorably in a few others. The causes of rising rates in IHD hot-spot regions merit more detailed investigation. Prevention and acute care quality improvements are needed in low- and middle- income regions, where IHD patients die at relatively young ages.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the many study participants and investigators of the studies contributing data to this analysis.

Sources of Funding

This research was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship to Dr Roth, and US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute award K08 HL089675-01A1, and a Columbia University Irving Scholarship to Dr Moran.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The perspectives expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, or any other government entity.

References

- 1.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Barker-Collo S, Bartels DH, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ, Bennett D, Bhalla K, Bikbov B, Bin Abdulhak A, Birbeck G, Blyth F, Bolliger I, Boufous S, Bucello C, Burch M, Burney P, Carapetis J, Chen H, Chou D, Chugh SS, Coffeng LE, Colan SD, Colquhoun S, Colson KE, Condon J, Connor MD, Cooper LT, Corriere M, Cortinovis M, de Vaccaro KC, Couser W, Cowie BC, Criqui MH, Cross M, Dabhadkar KC, Dahodwala N, De Leo D, Degenhardt L, Delossantos A, Denenberg J, Des Jarlais DC, Dharmaratne SD, Dorsey ER, Driscoll T, Duber H, Ebel B, Erwin PJ, Espindola P, Ezzati M, Feigin V, Flaxman AD, Forouzanfar MH, Fowkes FG, Franklin R, Fransen M, Freeman MK, Gabriel SE, Gakidou E, Gaspari F, Gillum RF, Gonzalez-Medina D, Halasa YA, Haring D, Harrison JE, Havmoeller R, Hay RJ, Hoen B, Hotez PJ, Hoy D, Jacobsen KH, James SL, Jasrasaria R, Jayaraman S, Johns N, Karthikeyan G, Kassebaum N, Keren A, Khoo JP, Knowlton LM, Kobusingye O, Koranteng A, Krishnamurthi R, Lipnick M, Lipshultz SE, Ohno SL, Mabweijano J, MacIntyre MF, Mallinger L, March L, Marks GB, Marks R, Matsumori A, Matzopoulos R, Mayosi BM, McAnulty JH, McDermott MM, McGrath J, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Michaud C, Miller M, Miller TR, Mock C, Mocumbi AO, Mokdad AA, Moran A, Mulholland K, Nair MN, Naldi L, Narayan KM, Nasseri K, Norman P, O'Donnell M, Omer SB, Ortblad K, Osborne R, Ozgediz D, Pahari B, Pandian JD, Rivero AP, Padilla RP, Perez-Ruiz F, Perico N, Phillips D, Pierce K, Pope CA, 3rd, Porrini E, Pourmalek F, Raju M, Ranganathan D, Rehm JT, Rein DB, Remuzzi G, Rivara FP, Roberts T, De León FR, Rosenfeld LC, Rushton L, Sacco RL, Salomon JA, Sampson U, Sanman E, Schwebel DC, Segui-Gomez M, Shepard DS, Singh D, Singleton J, Sliwa K, Smith E, Steer A, Taylor JA, Thomas B, Tleyjeh IM, Towbin JA, Truelsen T, Undurraga EA, Venketasubramanian N, Vijayakumar L, Vos T, Wagner GR, Wang M, Wang W, Watt K, Weinstock MA, Weintraub R, Wilkinson JD, Woolf AD, Wulf S, Yeh PH, Yip P, Zabetian A, Zheng ZJ, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, AlMazroa MA, Memish ZA. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Vanuzzo D, Hobbs M, Mähönen M, Cepaitis Z, Kuulasmaa K, Keil U. Estimation of contribution of changes in coronary care to improving survival, event rates, and coronary heart disease mortality across the WHO MONICA Project populations. Lancet. 2000;355:688–700. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)11181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuulasmaa K, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Dobson A, Fortmann S, Sans S, Tolonen H, Evans A, Ferrario M, Tuomilehto J. Estimation of contribution of changes in classic risk factors to trends in coronary-event rates across the WHO MONICA Project populations. Lancet. 2000;355:675–687. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)11180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Labarthe DR, Kottke TE, Giles WH, Capewell S. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980-2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2388–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Cesare M, Bennett JE, Best N, Stevens GA, Danaei G, Ezzati M. The contributions of risk factor trends to cardiometabolic mortality decline in industrialized countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:838–848. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirzaei M, Truswell AS, Taylor R, Leeder SR. Coronary heart disease epidemics: not all the same. Heart. 2009;95:740–746. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.154856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leeder S, Raymond S, Greenberg H, Liu H, Esson K. A Race Against Time: The Challenge of Cardiovascular Disease in Developing Countries. Columbia University Center for Global Health and Economic Development; New York, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moran AE, Oliver JT, Mirzaie M, Forouzanfar MH, Chilov M, Anderson L, Morrison JL, Khan A, Zhang N, Haynes N, Tran J, Murphy A, Degennaro V, Roth G, Zhao D, Peer N, Pichon-Riviere A, Rubinstein A, Pogosova N, Prabhakaran D, Naghavi M, Ezzati M, Mensah GA. Assessing the Global Burden of Ischemic Heart Disease, Part 1: methods for a systematic review of the Global Epidemiology of Ischemic Heart Disease in 1990 and 2010. Glob Heart. 2012;7:315–329. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forouzanfar MH, Moran AE, Flaxman AD, Roth G, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Naghavi M, Murray CJL. Assessing the global burden of ischemic heart failure, Part 2: analytic methods and estimates of the global epidemiology of ischemic heart disease in 2010. Global Heart. 2012;7:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naghavi M, Makela S, Foreman K, O'Brien J, Pourmalek F, Lozano R. Algorithms for enhancing public health utility of national causes-of-death data. Popul Health Metr. 2010;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray CJ, Kulkarni SC, Ezzati M. Understanding the coronary heart disease versus total cardiovascular mortality paradox: a method to enhance the comparability of cardiovascular death statistics in the United States. Circulation. 2006;113:2071–2081. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foreman KJ, Lozano R, Lopez AD, Murray CJ. Modeling causes of death: an integrated approach using CODEm. Popul Health Metr. 2012;10:1. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Ackerman I, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Ali MK, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Bahalim AN, Barker-Collo S, Barrero LH, Bartels DH, Basáñez MG, Baxter A, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ, Bennett D, Bernabé E, Bhalla K, Bhandari B, Bikbov B, Bin Abdulhak A, Birbeck G, Black JA, Blencowe H, Blore JD, Blyth F, Bolliger I, Bonaventure A, Boufous S, Bourne R, Boussinesq M, Braithwaite T, Brayne C, Bridgett L, Brooker S, Brooks P, Brugha TS, Bryan-Hancock C, Bucello C, Buchbinder R, Buckle G, Budke CM, Burch M, Burney P, Burstein R, Calabria B, Campbell B, Canter CE, Carabin H, Carapetis J, Carmona L, Cella C, Charlson F, Chen H, Cheng AT, Chou D, Chugh SS, Coffeng LE, Colan SD, Colquhoun S, Colson KE, Condon J, Connor MD, Cooper LT, Corriere M, Cortinovis M, de Vaccaro KC, Couser W, Cowie BC, Criqui MH, Cross M, Dabhadkar KC, Dahiya M, Dahodwala N, Damsere-Derry J, Danaei G, Davis A, De Leo D, Degenhardt L, Dellavalle R, Delossantos A, Denenberg J, Derrett S, Des Jarlais DC, Dharmaratne SD, Dherani M, Diaz-Torne C, Dolk H, Dorsey ER, Driscoll T, Duber H, Ebel B, Edmond K, Elbaz A, Ali SE, Erskine H, Erwin PJ, Espindola P, Ewoigbokhan SE, Farzadfar F, Feigin V, Felson DT, Ferrari A, Ferri CP, Fèvre EM, Finucane MM, Flaxman S, Flood L, Foreman K, Forouzanfar MH, Fowkes FG, Fransen M, Freeman MK, Gabbe BJ, Gabriel SE, Gakidou E, Ganatra HA, Garcia B, Gaspari F, Gillum RF, Gmel G, Gonzalez-Medina D, Gosselin R, Grainger R, Grant B, Groeger J, Guillemin F, Gunnell D, Gupta R, Haagsma J, Hagan H, Halasa YA, Hall W, Haring D, Haro JM, Harrison JE, Havmoeller R, Hay RJ, Higashi H, Hill C, Hoen B, Hoffman H, Hotez PJ, Hoy D, Huang JJ, Ibeanusi SE, Jacobsen KH, James SL, Jarvis D, Jasrasaria R, Jayaraman S, Johns N, Jonas JB, Karthikeyan G, Kassebaum N, Kawakami N, Keren A, Khoo JP, King CH, Knowlton LM, Kobusingye O, Koranteng A, Krishnamurthi R, Laden F, Lalloo R, Laslett LL, Lathlean T, Leasher JL, Lee YY, Leigh J, Levinson D, Lim SS, Limb E, Lin JK, Lipnick M, Lipshultz SE, Liu W, Loane M, Ohno SL, Lyons R, Mabweijano J, MacIntyre MF, Malekzadeh R, Mallinger L, Manivannan S, Marcenes W, March L, Margolis DJ, Marks GB, Marks R, Matsumori A, Matzopoulos R, Mayosi BM, McAnulty JH, McDermott MM, McGill N, McGrath J, Medina-Mora ME, Meltzer M, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Meyer AC, Miglioli V, Miller M, Miller TR, Mitchell PB, Mock C, Mocumbi AO, Moffitt TE, Mokdad AA, Monasta L, Montico M, Moradi-Lakeh M, Moran A, Morawska L, Mori R, Murdoch ME, Mwaniki MK, Naidoo K, Nair MN, Naldi L, Narayan KM, Nelson PK, Nelson RG, Nevitt MC, Newton CR, Nolte S, Norman P, Norman R, O'Donnell M, O'Hanlon S, Olives C, Omer SB, Ortblad K, Osborne R, Ozgediz D, Page A, Pahari B, Pandian JD, Rivero AP, Patten SB, Pearce N, Padilla RP, Perez-Ruiz F, Perico N, Pesudovs K, Phillips D, Phillips MR, Pierce K, Pion S, Polanczyk GV, Polinder S, Pope CA, 3rd, Popova S, Porrini E, Pourmalek F, Prince M, Pullan RL, Ramaiah KD, Ranganathan D, Razavi H, Regan M, Rehm JT, Rein DB, Remuzzi G, Richardson K, Rivara FP, Roberts T, Robinson C, De Leòn FR, Ronfani L, Room R, Rosenfeld LC, Rushton L, Sacco RL, Saha S, Sampson U, Sanchez-Riera L, Sanman E, Schwebel DC, Scott JG, Segui-Gomez M, Shahraz S, Shepard DS, Shin H, Shivakoti R, Singh D, Singh GM, Singh JA, Singleton J, Sleet DA, Sliwa K, Smith E, Smith JL, Stapelberg NJ, Steer A, Steiner T, Stolk WA, Stovner LJ, Sudfeld C, Syed S, Tamburlini G, Tavakkoli M, Taylor HR, Taylor JA, Taylor WJ, Thomas B, Thomson WM, Thurston GD, Tleyjeh IM, Tonelli M, Towbin JA, Truelsen T, Tsilimbaris MK, Ubeda C, Undurraga EA, van der Werf MJ, van Os J, Vavilala MS, Venketasubramanian N, Wang M, Wang W, Watt K, Weatherall DJ, Weinstock MA, Weintraub R, Weisskopf MG, Weissman MM, White RA, Whiteford H, Wiebe N, Wiersma ST, Wilkinson JD, Williams HC, Williams SR, Witt E, Wolfe F, Woolf AD, Wulf S, Yeh PH, Zaidi AK, Zheng ZJ, Zonies D, Lopez AD, AlMazroa MA, Memish ZA. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmad OB, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, Murray CJL, Lozano R, Inoue M. Age standardization of rates: a new who standard. GPE discussion paper series: No. 31. Switzerland: World Health Organization; Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaridze D, Maximovitch D, Lazarev A, Igitov V, Boroda A, Boreham J, Boyle P, Peto R, Boffetta P. Alcohol poisoning is a main determinant of recent mortality trends in Russia: evidence from a detailed analysis of mortality statistics and autopsies. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:143–153. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leon DA, Shkolnikov VM, McKee M, Kiryanov N, Andreev E. Alcohol increases circulatory disease mortality in Russia: acute and chronic effects or misattribution of cause? Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:1279–1290. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huffman MD, Rao KD, Pichon-Riviere A, Zhao D, Harikrishnan S, Ramaiya K, Ajay VS, Goenka S, Calcagno JI, Caporale JE, Niu S, Li Y, Liu J, Thankappan KR, Daivadanam M, van Esch J, Murphy A, Moran AE, Gaziano TA, Suhrcke M, Reddy KS, Leeder S, Prabhakaran D. A cross-sectional study of the microeconomic impact of cardiovascular disease hospitalization in four low- and middle-income countries. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev. 2012;70:3–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joshi P, Islam S, Pais P, Reddy S, Dorairaj P, Kazmi K, Pandey MR, Haque S, Mendis S, Rangarajan S, Yusuf S. Risk factors for early myocardial infarction in South Asians compared with individuals in other countries. JAMA. 2007;297:286–294. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Danaei G, Singh GM, Paciorek CJ, Lin JK, Cowan MJ, Finucane MM, Farzadfar F, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Lu Y, Rao M, Ezzati M, Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases Collaborating Group The global cardiovascular risk transition: associations of four metabolic risk factors with national income, urbanization, and Western diet in 1980 and 2008. Circulation. 2013;127:1493–502. 1502e1. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farzadfar F, Finucane MM, Danaei G, Pelizzari PM, Cowan MJ, Paciorek CJ, Singh GM, Lin JK, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Ezzati M, Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases Collaborating Group (Cholesterol) National, regional, and global trends in serum total cholesterol since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 321 country-years and 3.0 million participants. Lancet. 2011;377:578–586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicolosi A, Casati S, Taioli E, Polli E. Death from cardiovascular disease in Italy, 1972-1981: decline in mortality rates and possible causes. Int J Epidemiol. 1988;17:766–772. doi: 10.1093/ije/17.4.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brook RD, Franklin B, Cascio W, Hong Y, Howard G, Lipsett M, Luepker R, Mittleman M, Samet J, Smith SC, Jr, Tager I, Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science of the American Heart Association Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;109:2655–2671. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128587.30041.C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.2008–2013 action plan for the global strategy for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Switzerland: World Health Organization; Geneva: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebrahim S, Smith GD. Exporting failure? Coronary heart disease and stroke in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:201–205. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaziano TA. Cardiovascular disease in the developing world and its cost-effective management. Circulation. 2005;112:3547–3553. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.