Abstract

Background

Exposure to alcohol consumption and product imagery in films is associated with increased alcohol consumption among young people, but the extent to which exposure also occurs through television is not clear. We have measured the occurrence of alcohol imagery in prime-time broadcasting on UK free-to-air television channels.

Methods

Occurrence of alcohol imagery (actual use, implied use, brand appearances or other reference to alcohol) was measured in all broadcasting on the five most popular UK television stations between 6 and 10 p.m. during 3 weeks in 2010, by 1-min interval coding.

Results

Alcohol imagery occurred in over 40% of broadcasts, most commonly soap operas, feature films, sport and comedies, and was equally frequent before and after the 9 p.m. watershed. Brand appearances occurred in 21% of programmes, and over half of all sports programmes, a third of soap operas and comedies and a fifth of advertising/trailers. Three brands, Heineken, Budweiser and Carlsberg together accounted for ∼40% of all brand depictions.

Conclusions

Young people are exposed to frequent alcohol imagery, including branding, in UK prime-time television. It is likely that this exposure has an important effect on alcohol consumption in young people.

Keywords: alcohol, children and young people, media, policy, prevention, public health

Introduction

Systematic reviews of prospective cohort studies of exposure to alcohol advertising and marketing in various media have demonstrated significant associations with alcohol consumption among young people.1,2 Alcohol imagery occurs frequently in films marketed to children and young people in the UK,3 the USA4 and other countries5,6; and studies have demonstrated that exposure to alcohol use in films is an independent risk factor for initiation of alcohol use,7 consumption of alcohol without parental knowledge,5 binge drinking5 and increased consumption whilst watching films.8 However, since an estimated 27 million British homes have at least one television,9 over 75% of 7–14 year olds watch 2 h or more of television every weekday and 95% do so at the weekend,10 with 63% of children having their own television set in their own bedroom11 (where parents will be less aware of what their children are watching), and television content is also available online for on-demand or catch-up viewing,12 television is a potentially much greater source of exposure to alcohol imagery than films alone.13–16

Alcohol imagery is common in popular television programmes in countries outside the UK,17,18 and was especially so in UK television in the 1980s and 1990s,19–21 when British television fiction contained three times more depictions of alcohol consumption than equivalent programmes from Canada or the USA.22 A 2005 analysis of the 10 programmes most frequently watched by 10–15 year olds in the UK found that alcohol-related scenes occurred an average of 12 times every hour, actual or implied alcohol drinkers represented 21% of the characters shown, drinkers had relatively prominent roles and 37% of major characters were identified as drinkers.23 However, there has been no recent study of alcohol content across a comprehensive range of prime-time UK television broadcasting either before or after the 9 p.m. watershed, before which programmes are required to be suitable for viewing by those aged under 15 years.24 We have therefore measured the content of all programmes and advertisements/trailers broadcast on the five national UK free-to-air channels during the peak viewing hours of 6 to 10 p.m. in three separate weeks in 2010 to document the amount of alcohol imagery contained and to explore differences in content between channels and genres.

Methods

There were five national free-to-air channels available for viewing without a cable or satellite connection or subscription in the UK when this study was undertaken (BBC1, BBC2, ITV1, Channel4 and Channel5). These are also the most frequently viewed channels.25 Three of these (ITV1, Channel4 and Channel5) are commercial stations which broadcast commercial advertising; BBC1 and BBC2 are public service channels with no commercial advertising. We recorded all material broadcast for seven consecutive days from Monday to Sunday on three occasions 4 weeks apart (19–25 April; 17–23 May and 14–20 June 2010) during the prime-time television viewing period of 6–10 p.m. This included 3h before and 1h after the 9 p.m. watershed. All television was recorded as broadcast in Nottingham, in the East Midlands Region of the UK. Categories for coding were developed based on previous research investigating alcohol content in films3–6 and on television.17–23 Broadcasts were then coded, using 1-min intervals, into the following categories:

Alcohol use: actual use of alcohol on-screen by any character. The type of alcohol used was coded as beer, wine/champagne, spirits/liqueur, cocktails, mixed drink types (such as in a group or crowd scene) and type unknown.

Implied alcohol use: the presence of any implied but not actual use, categorized as a visible appearance of an alcoholic drink but without consumption, or a verbal reference to alcohol use, such as ordering a drink.

Other reference to alcohol: reference to alcohol without actual or implied use, for example beer pumps behind a bar in the background of a scene, or a verbal or written reference to alcohol that was unrelated to actual or implied current use.

Alcohol brand appearance: clear, unambiguous alcohol branding on-screen. This was sub-grouped as branding on a product used in a scene, branding on a product not used in a scene, branded merchandise, advertisements in commercial breaks or visible in other programme content and any other (noted).

Any alcohol: the presence of any of the above.

The categories of alcohol appearances were recorded as having occurred if observed on-screen once or more in any 1-min coding period. Multiple occurrences in the same category in the same 1-min interval were counted as a single event, and those that crossed a transition from 1-min interval to the next were recorded as two separate appearances. Occurrences in different coding categories were recorded as separate instances. Since changes from one programme to the next, or breaks in a programme for advertising did not necessarily occur at the end of a one 1-min interval, we coded part-minutes immediately before programme changes. For the minutes that crossed over the transition from advertisements to programmes, and vice versa, half the minute was considered advertising, and half as programming, and recorded as part-minutes. Although the BBC channels showed no commercial advertising they did broadcast programme trailers in the breaks between programmes; this also occurred on the commercial channels, often in conjunction with commercial advertising. We therefore coded advertisements and trailers together. We also categorized the genre of the programme (comedy, drama, soap opera, news, game show, feature film, chat show, sport, party political broadcast, documentary, reality TV, sci-fi/fantasy), as identified from the programme announcement, the Internet Movie Database (IMDb), the channel's webpage or the researcher's discretion, and noted whether any part of the programme was broadcast before or after the 9 p.m. watershed.

Results

We recorded 420 h of broadcasting, comprising 613 programmes and 1121 advertisements/trailer breaks, and including 25 210 part or full 1-min intervals, of which 21 996 were from programmes and 3214 from advertisements/trailers. Channel5 broadcast a total of 165 different programmes: BBC1 120, BBC2 116, Channel4 109 and ITV1 103. Documentaries (161), news programmes (139) and soap operas (72) were the most frequent genres. Documentaries also occupied the greatest amount of broadcasting time (6935 min), followed by news (2862 min), drama (2250 min) and sport (2169 min).

Any alcohol

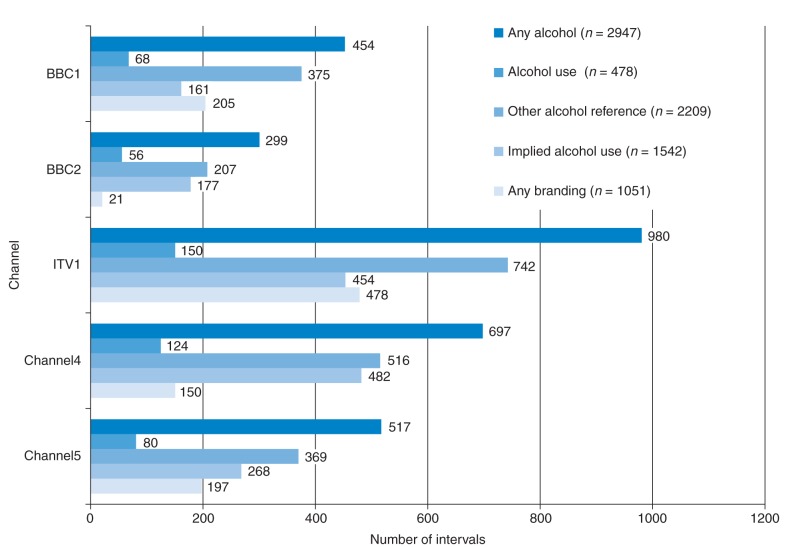

There were 2947 intervals (12% of total) containing any alcohol, this proportion being highest on ITV1 (19%) and lowest on BBC2 (6%; chi² for difference in proportions = 521.19, P < 0.05; BBC1 9%, Channel5 10%, Channel4 14%; Fig. 1). These intervals occurred in 738 separate broadcasts (43% of all broadcasts) comprising 318 programmes (52% of all programmes) and 420 advertisements/trailer breaks (37%). The proportion of broadcasts containing any alcohol was highest on ITV1 (58%) and lowest on BBC1 (27%; chi² = 60, P < 0.05; BBC2 33%, Channel4 45%, Channel5 40%). Any alcohol appeared on average every 9 min, ranging from every 5 min on ITV1 to every 11 min on BBC1. There was no difference in the proportion of intervals containing any alcohol shown before (12%; 2189/19 024.5) or after (12%; 758/6185.5) the watershed. The number of intervals containing any alcohol by coded category can be seen in Table 1. The hour of broadcasting that shows the greatest amount of alcohol content is the hour immediately before the 9 p.m. watershed.

Fig. 1.

Number of 1-min intervals that contain any alcohol on each channel, by coded category.

Table 1.

The number of intervals of alcohol content by coded category for each hour of broadcasting (18:00–22:00)

| Hour | Any alcohol | Alcohol use | Implied alcohol use | Other reference to alcohol | Alcohol brand appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18.00–18.59 | 623 | 100 | 345 | 462 | 169 |

| 19.00–19.59 | 741 | 124 | 408 | 574 | 266 |

| 20.00–20.59 | 825 | 137 | 429 | 698 | 345 |

| 21.00–22.00 | 758 | 117 | 360 | 475 | 271 |

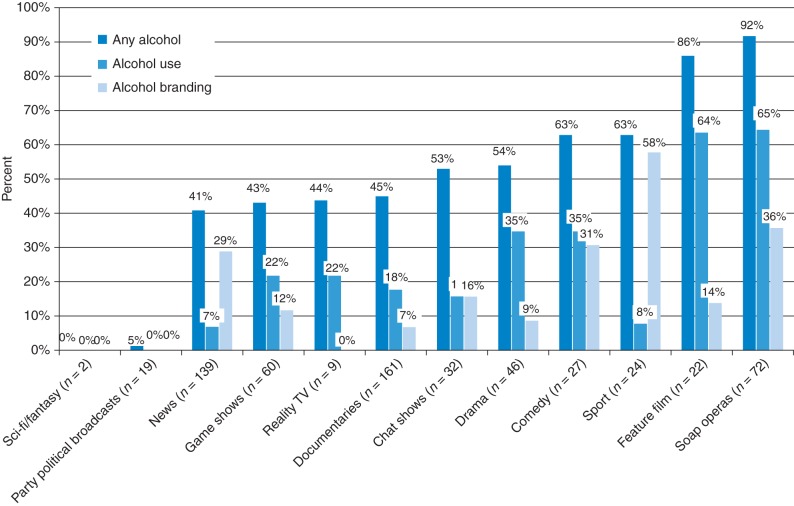

The programmes analysed included 12 genres, of which 1 (sci-fi/fantasy) contained no alcohol content. Soap operas contained the highest proportion including any alcohol (92%), followed by feature films (86%), sport (63%) and comedy (63%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The proportion of programmes in each of the 12 genres containing any alcohol (n= 613), alcohol use (n= 613) and alcohol branding (n= 613).

Alcohol use

Alcohol use occurred in 478 intervals, comprising 2% of all intervals and occurring in 147 programmes (24%) and 37 advertisements/trailer breaks (3%). Most alcohol use was the consumption of beer (31%), followed by wine or champagne (31%), spirits (20%), mixed drink types (12%), cocktails (4%) and type unknown (2%). Alcohol use occurred in 10 genres (Fig. 2), and in more than half of all soap operas (65%) and feature films (64%). The proportion of intervals containing alcohol use before the 9 p.m. watershed (2.5%) was significantly higher than the proportion after 9 p.m. (1.9%; 117/6185.5, chi² = 7.30, P < 0.05).

Implied alcohol use and other reference to alcohol

Categories of implied alcohol use intervals occurred in total 1559 times, either alone or in the same interval as another category of implied alcohol use, in 1542 intervals (6%). These intervals were present in 493 broadcasts (28%), 221 programmes (36%) and 272 advertisements/trailer breaks (24%). Categories of other reference to alcohol occurred in total 2934 times, either alone or in the same interval as another category of other reference to alcohol, in 2209 intervals (359 in advertisements/trailer breaks and 1850 in programmes); 9% of all broadcast intervals, 8% of all programme intervals and 11% of all advertising/trailer intervals. Intervals of other alcohol reference were present in 563 broadcasts (32%), 287 programmes (47%) and 276 advertisements/trailer breaks (25%). Other reference to alcohol was more frequently a verbal or written comment or discussion (1518) either alone or with the presence of alcohol products where no use or implied use occurred (1416).

Brand appearances

There were 1579 alcohol brand appearances which occurred in 1051 intervals (4%), comprising 3% of programme and 9% of advertising/trailer intervals (chi² = 211.6, P < 0.05). The proportion of programme genres, depicting brand appearances is shown in Fig. 2. Twenty-one per cent of programmes (21%) and 20% of advertising/trailer breaks contained alcohol branding.

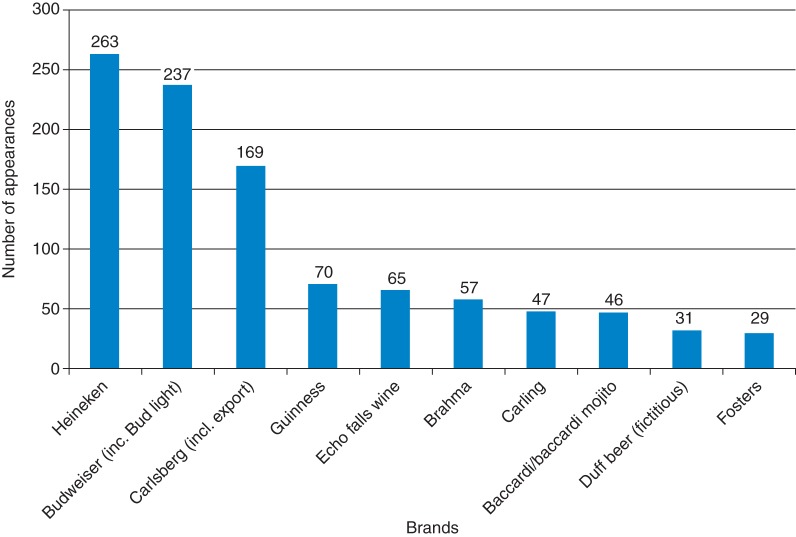

Episodes of alcohol branding comprised advertising, such as billboards (668), branded products such as bottles visible behind a bar (343) or held or used (104) in a scene and branded items such as umbrellas or clothing (146). There were nine other brand representations, all of them verbal, such as an offer of a branded drink that was not visible on-screen. The proportion of alcohol brands in programmes ranged from 0% (Sci-fi/fantasy; Reality TV; Party Political Broadcasts) to 58% of sport (Fig. 2). The brands that appeared most frequently were Heineken (263) Budweiser (237) and Carlsberg (169), which together accounted for 41% of all brand appearances. The 10 most frequently depicted alcohol brands are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The 10 most frequently depicted brands that appeared and the number of times that they appeared (n= 1014).

Discussion

Main findings of the study

This study demonstrates that alcohol appears frequently on UK terrestrial television, on average once in every 9-min of broadcasting, and in more than half of all programmes and more than a third of all advertisements/trailer breaks. Alcohol content was more common in certain programme genres, particularly soap operas, feature films, sport and comedy. The frequency of any alcohol content did not differ before and after the 9 p.m. watershed but alcohol use, predominantly beer drinking was more common before the watershed. Alcohol branding occurred in about a fifth of all programmes, over half of all sports programmes, a third of soap operas and comedies and a fifth of all advertisements/trailer breaks. The most commonly appearing brands were Heineken, Budweiser and Carlsberg, which together accounted for ∼40% of all brand appearances. Although we do not have access to data on individual brand sales in the UK, secondary reporting suggests that these three brands were ranked, respectively, at 19th, 5th and 4th most popular brands for off-trade (that is, for consumption off the sale premises) at the time of the study.26

What is already known on the topic

Previous studies from outside the UK have shown that alcohol is frequently shown on television,17,18,27–29 occurring about twice an hour in US programmes in the 1970's18 and over four times per hour in US West Coast television broadcasting in the 1980's.27 In 2000 alcohol was evident in 77% of popular prime-time episodes in top-rated prime-time US television programmes and was actually consumed in 71%,17 while in 2009 in top-rated prime-time television series in the USA, alcohol was commonly depicted in dramas and comedies, appearing in at least 1 episode of the 18 series studied.28 In New Zealand broadcasting it has been shown that the programme containing the greatest number of alcohol scenes was the British soap opera Coronation Street. 29 A 1992 comparison of television programme alcohol content in three countries (USA, Canada and UK) found that British television fiction depicted three times more alcohol consumption than US or Canadian television.22 Studies from the 1980's and 1990s19,21 have also found alcohol to be commonly shown on British television; in 1988 a reference to alcohol occurred on average every 6 min,19 while in 1997 popular British soap operas made reference to alcohol every 3.2 min21 and at least once in 86% of soap episodes.21 A more recent UK study (2004)23 found an alcohol-related scene occurred ∼12 times every hour in the top 10 programmes most frequently watched by British young people. Alcohol advertising has also been shown to be common in televised sporting events in the USA.30,31

What this study adds

This is the first study for nearly two decades to document alcohol content in a comprehensive sample of prime-time terrestrial UK television broadcasting. Unlike the only recent study of UK programming,23 the present study included advertisement and programme trailer breaks, both of which have been shown elsewhere to include alcohol.20,21,27,30–34 Our findings demonstrate similar frequencies of alcohol use to that of US programming in the 1970s,18 and less frequent occurrences of any imagery than in British television in 1988,19 but confirm the high frequency of alcohol imagery in British soap operas20,21,23 including Eastenders,20,23 Emmerdale Farm21,23 and Coronation Street,22 all of which feature public houses (such as the Rovers Return Inn in Coronation Street). What is surprising however is although most of these pubs show fictitious branding (e.g. Ephraim Monk beer in Emmerdale and Jenkins beer in Eastenders), they also show real brands (e.g. Corona beer bottles visible in the background of a bar in Eastenders).

A 1982 US study found that alcohol imagery was common in films broadcast on television,27 a finding replicated in the present study. All of the films containing alcohol in our study were rated by UK film classifiers as suitable for viewing by people aged under 18.35,36 This finding reflects the fact that alcohol imagery is common in films popular at the UK box office.37 However, the genre for which the highest proportion of programmes, and the highest proportion of intervals, contained alcohol branding was sport. Previous studies also found alcohol advertising and promotion, and particularly beer branding, to be common in sporting broadcasts.30,31 The most depicted brands in any broadcast here were also beer brands.

Television programming in the UK is regulated by Ofcom,24 an independent regulator which under the provisions of the 2003 Communications Act38 publishes standards for the content of programmes.39 Ofcom requires only alcohol abuse to not feature in programmes specifically targeted at children, and in other programmes alcohol should ‘generally be avoided and in any case must not be condoned, encouraged or glamorised in […] programmes broadcast before the watershed […] unless there is editorial justification’ (section 1.1039,40). No reference is made to other forms of alcohol portrayal or content or generic or branded alcohol appearances; the only reference is to alcohol abuse. Ofcom has been aware of high levels of alcohol content in UK soap operas and their popularity amongst young people at least since 2005.23 It is unlikely that the real brands appearing are the result of product placement (paid-for or other valuable consideration41), as product placement was not permitted on UK television when this study was conducted. Brands are permitted to appear if they can be ‘editorially justified’,41 and prop placement, defined as ‘references to products or services acquired at no, or less than full, cost, where their inclusion within the programme is justified editorially, will not be considered to be product placement’ (p. 4939) was and remains permitted in UK television.

Alcohol advertising has been linked to underage drinking,42 and televised advertisements are regulated by the Advertising Standards Authority43 through the Committee of Advertising Practice,44 which comprises advertisers, agencies and media owners,45 and are expected to conform to Broadcast CAP46 rules. These rules state that alcohol ‘may not be advertised in or adjacent to children's programmes or programmes commissioned for, principally directed at or likely to appeal particularly to audiences below the age of 18’,47 and that advertisements must not ‘appeal strongly to people under 18, especially by reflecting or being associated with youth culture or showing adolescent or juvenile behaviour’.46 However, programmes can be popular with young people without being principally directed at them, and the definition of advertising does not appear to include sponsorship of programmes (such as Zamaretto branding in programme trailers for James Corden's World Cup Live chat show) that young people watch, or sponsorship such as pitch side advertisements at televised football or rugby. Sponsorship is subject to a code of practice on naming, packaging and promotion of alcohol48 published and developed by the Portman Group,49 established by leading alcohol producers in 198950 and representing nine major UK companies including Ab InBev, Carlsberg UK and Heineken UK. Their code states that in the case of sponsorship, ‘those under 18 years of age should not comprise more than 25% of the participants, audience or spectators’ (p. 7)48; exposure of large numbers of children if part of a much larger audience across a wide age-range is therefore not prevented by this approach.

Alcohol branding was frequently coupled in our study with sporting broadcasts, with Heineken, Budweiser and Carlsberg brands being the most common. Heineken,51 who claim on their webpage to being the UK's leading beer and cider business with a market share of almost 30%, state in their corporate responsibility strategy that their brands ‘will not be placed in, or on, media directed primarily at under 18's’ and they will ‘not promote…[Heineken brands]…in media, events or programmes where the majority of the audience are known to be under 18’.52 Both Budweiser, owned by InBev in the UK,53 and Carlsberg Group54 make similar claims. Despite each of the companies advocating they do not promote their products to children and young people, their brands are still appearing in programmes that have previously been shown to be popularly viewed by youth, before the watershed, and at times of the day that children and young people frequently view television.

Our findings thus demonstrate that prime-time television is a major source of exposure to alcohol imagery among children, and as such is likely to be contributing to uptake and consumption of alcohol among young people in the UK.55 Tighter regulation of advertising and promotion of alcoholic drinks, including promotion through sporting events, has been proposed as a means to reduce consumption56–58 among children and young people; our findings suggest that such measures should include television programme content as well as advertising, particularly before the 9 p.m. watershed.

Limitations of this study

As we recorded 3 weeks of television broadcasting over a 3-month period, there is the potential, due to seasonal variation in broadcasting, for the sample to not be representative of television broadcast throughout the year. However, with the exception of sporting broadcasts, which are only aired during certain times of the year, the programme genres in which alcohol content was most commonly found (feature films, soap operas and comedy) are broadcast throughout the year.

We coded terrestrial channels only, as these are accessible to the vast majority of households, and consistently dominate television viewing in the UK.25 Although we felt, given their large audiences, that these channels would be frequently viewed by young audiences, it is additionally likely that young people have access to, and frequently watch, other channels broadcast on subscription channels. We limited recording and coding to prime-time broadcasting only, between the hours of 6 and 10 p.m. Monday to Sunday, as this is the time period when the vast majority of television is watched, and in which the most watched programmes are broadcast.59 While it would be useful to gain information on programmes broadcast outside of these times, this was not possible given the time-consuming nature of the data collection, and the time available to us for the work. The authors acknowledge a need for further research into the way in which young people consume different types of media, particularly how television programmes and films are accessed and watched, including the role of on-demand television and catch-up viewing services (e.g. Sky+), internet television software applications (e.g. BBC i-player) and piracy (e.g. illegal downloaded content), as well as where (e.g. bedroom, living room) and how television content is viewed (e.g. on television, computer, tablet, phone); all of which was beyond the intention and scope of this study.

Funding

This research was conducted as part of the research undertaken by Ailsa Lyons for her PhD. The PhD was funded by the UK Centre for Tobacco Control Studies, which is a UKCRC Centre of Public Health Research Excellence. Funding from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, the Economic and Social Research Council, the Medical Research Council and the Department of Health, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by The University of Nottingham.

References

- 1.Smith L, Foxcroft DR. The effects of alcohol advertising, marketing and portrayal on drinking behaviour in young people: systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(51):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson P, de Bruijn A, Angus K, et al. Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44(3):229–43. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyons A, McNeill A, Gilmore I, et al. Alcohol imagery and branding, and age classification of films popular in the UK. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(5):1411–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dal Cin S, Worth KA, Dalton MA, et al. Youth exposure to alcohol use and brand appearances in popular contemporary movies. Addiction. 2008;103(12):1925–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanewinkel R, Tanski SE, Sargent JD. Exposure to alcohol use in motion pictures and teen drinking in Germany. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(5):1068–77. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aina O, Olorunshola DA. Alcohol and substance use portrayals in Nigerian video tapes: an analysis of 479 films and implications for public drug education. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2007;28(1):63–71. doi: 10.2190/IQ.28.1.f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sargent J, Wills TA, Stoolmiller M, et al. Alcohol use in motion pictures and its relation with early-onset teen drinking. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2006;67(1):54–65. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engels R, Hermans R, van Baaren RB, et al. Alcohol portrayal on television affects actual drinking behaviour. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44(3):244–9. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broadcasters' Audience Research Board. London: 2011. Television ownership in private domestic households 1956–2011. http://www.webcitation.org/query?Url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.barb.co.uk%2Ffacts%2FtvOwnershipPrivate%3F_s%3D4&date=2011-10-07. (1 August 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 10.UKFC. London: 2010. 2009 statistical yearbook; pp. 1–192. http://sy09.ukfilmcouncil.ry.com/action/downloads/?Id=41091. (10 December 2010, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Childwise. Norwich: Childwise; 2012. Childwise monitor trends report 2012. http://www.childwise.co.uk/childwise-published-research-detail.asp?PUBLISH=53. (5 June 2012, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ofcom. London: Ofcom; 2010. Public service broadcasting annual report 2010. http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/binaries/broadcast/reviews-investigations/psb-review/psb2010/psbreport.pdf. (12 December 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Foe JR, Breed W. The mass media and alcohol education: a new direction. J Alcohol Drug Educ. 1980;25(3):48–58. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singer DG. Alcohol, television, and teenagers. Pediatrics. 1985;76(4 Pt 2):668–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stacy AW, Zogg JB, Unger JB, et al. Exposure to televised alcohol ads and subsequent adolescent alcohol use. Am J Health Behav. 2004;28(6):498–509. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.6.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Congress. Senate committee on labor and public welfare. Subcommittee on Alcoholism and Narcotics. Media images of alcohol: the effects of advertising and other media on alcohol abuse. U.S. Govt. Print. Off; Washington: 1976. http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?Id=mdp.39015077925728. (7 June 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christenson P, Henriksen L, Roberts DF. Substance Use in Popular Prime-Time Television, in Office of National Drug Control Policy. Washington, DC: 2000. Office of National Drug Control Policy and Mediascope, Macro International, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenberg B, Fernandez-Collardo C, Graef D, et al. Trends in use of alcohol and other substances on television. Drug Educ. 1979;9:243–53. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith C, Roberts JL, Pendleton LL. Booze on the box, the portrayal of alcohol on British television: a content analysis. Health Educ Res. 1988;3(3):267–72. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pendleton L, Smith C, Roberts JL. Drinking on television: a content analysis of recent alcohol portrayal. Br J Addict. 1991;86(6):769–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb03102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furnham A, Ingle H, Gunter B, et al. A content analysis of alcohol portrayal and drinking in British television soap operas. Health Educ Res. 1997;12(4):519–29. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waxer PH. Alcohol consumption in television programming in three English-speaking cultures. Alcohol Alcohol. 1992;27(2):195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cumberbatch G, Gauntlett S. London: Ofcom; 2005. Smoking, alcohol, and drugs on television: A content analysis. http://www.webcitation.org/query?Url=http%3A%2F%2Fstakeholders.ofcom.org.uk%2Fbinaries%2Fresearch%2Fradio-research%2Fsmoking.pdf&date=2011-10-07. (10 November 2008, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ofcom. London: 2011. Ofcom. http://www.ofcom.org.uk. (8 August 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Broadcasters' Audience Research Board (BARB) London: 2011. Channel viewing share. http://www.webcitation.org/query?Url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.barb.co.uk%2Fgraph%2FviewingShare%3F_s%3D4&date=2011-10-07. (26 May 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielson. London: Nielson; 2012. Off licence news, the voice of drinks retailing: beer report 2010. http://www.butcombebottles.com/reports/Off%20Licence%20News%20Beer%20Report%202010.pdf. (9 November 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cafiso J, Goodstadt MS, Garlington WK, et al. Television portrayal of alcohol and other beverages. J Stud Alcohol. 1982;43(11):1232–43. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1982.43.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell C, Russell DW. Alcohol messages in prime-time television series. J Consumer Affairs. 2009;43(1):108–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6606.2008.01129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGee R, Ketchel J, Reeder AI. Alcohol imagery on New Zealand television. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2007;2 doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-2-6. ArtID 6.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madden P, Grube JW. The frequency and nature of alcohol and tobacco advertising in televised sports, 1990 through 1992. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(2):297–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.2.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zwarun L. Ten years and 1 master settlement agreement later: the nature and frequency of alcohol and tobacco promotion in televised sports, 2000 through 2002. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(8):1492–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Hoof JJ, de Jong MDT, Fennis BM, et al. There's alcohol in my soap: portrayal and effects of alcohol use in a popular television series. Health Educ Res. 2009;24(3):421–29. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fielder L, Donovan RJ, Ouschan R. Exposure of children and adolescents to alcohol advertising on Australian metropolitan free-to-air television. Addiction. 2009;104(7):1157–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diener B. The frequency and context of alcohol and tobacco cues in daytime soap opera programs: fall 1986 and fall 1991. J Public Policy Mark. 1993;12(2):252–57. [Google Scholar]

- 35.BBFC. The British Board of Film Classification. 2009. http://www.bbfc.co.uk. (8 October 2009, date last accessed)

- 36.Internet Movie Database (IMDb) http://www.webcitation.org/query?Url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.imdb.com%2F&date=2011-10-07. (1 February 2009, date last accessed) http://www.imdb.com .

- 37.Lyons A, McNeill A, Gilmore I, et al. Alcohol imagery and branding, and age classification of films popular in the UK. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:1411–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Communications Act. London: 2003. HMSO http://www.webcitation.org/query?Url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.legislation.gov.uk%2Fukpga%2F2003%2F21%2Fcontents&date=2011-10-07. (3 April 2009 date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ofcom. London: Ofcom; 2009. The Ofcom Broadcasting Code (incorporating the cross-promotion code) http://www.webcitation.org/query?Url=http%3A%2F%2Fstakeholders.ofcom.org.uk%2Fbinaries%2Fbroadcast%2Fcode09%2Fbcode09.pdf&date=2011-10-07. (21 July 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ofcom. London: 2011. What is the watershed? http://www.webcitation.org/query?Url=http%3A%2F%2Fconsumers.ofcom.org.uk%2F2011%2F06%2Fwhat-is-the-watershed%2F&date=2011-10-07. (9 September 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ofcom. London: Ofcom; 2011. Broadcasting Code guidance notes: Section 9: commercial references in television programming. http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/binaries/broadcast/guidance/831193/section9.pdf. (28 September 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Booth A, Meier P, Stockwell T, et al. London: Department of Health; 2008. Independent review of the effects of alcohol pricing and promotion; pp. 1–243. http://www.shef.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.95617!/file/PartA.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 43.Advertising Standards Authority. Advertising standards authority. 2010. http://www.asa.org.uk. (2 June 2010, date last accessed)

- 44.Committee of Advertising Practice. Committee of advertising practice. 2010. http://bcap.org.uk .

- 45.Ofcom/VASA. London: Ofcom/VASA; 2007. Young people and alcohol advertising: an investigation of alcohol advertising following changes to the advertising code; pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Broadcast Committee of Advertising Practice. BCAP code. 2010. http://www.cap.org.uk/The-Codes/BCAP-Code/BCAP-Code-Item.aspx?Q=Test_Specific%20Category%20Sections_19%20Alcohol#c674,CAP .

- 47.Broadcast Committee of Advertising Practice. BCAP rules on the scheduling of television advertisements. http://www.cap.org.uk/The-Codes/BCAP-Code.aspx?Q=Test_Specific%20Category%20Sections_19%20Alcohol_Rules_Rules%20that%20apply%20to%20all%20advertisements#c678. (2010, date last accessed)

- 48.The Portman Group. London: 2011. Code of practice on the naming, packaging, and promotion of alcoholic drinks; pp. 1–24. http://www.portmangroup.org.uk/assets/documents/Code%20of%20practice%204th%20Edition.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 49.The Portman Group. London: 2011. The Portman Group. http://www.portmangrouorg.uk/?Pid=1&level=1. (29 September 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 50.The Portman Group. London: 2011. About us http://www.portmangroup.org.uk/?Pid=2&level=1. (2 September 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heineken UK. 2011. http://www.heineken.co.uk. (28 September 2011, date last accessed)

- 52.Heineken UK. Corporate responsibility: responsible consumption: rules on responsible commercial communication. 2011. http://www.heeken.co.uk/resp_respconsumption-resp_rules_commercial.php. (28 September 2011, date last accessed)

- 53.InBev. Corporate responsibility: code of commercial communications. 2011. pp. 1–12. http://www.inbev.co.uk/Brands_UK_and_Ireland.htm. (28 September 2011, date last accessed)

- 54.Carlsberg Group. Marketing communication: marketing communication policy, in corporate social responsibility. 2011. pp. 1–4. http://www.carlsberggroup.com/csr/map/Pages/Responsibledrinkingatfestivals.aspx. (28 September 2011, date last accessed)

- 55.Department of Health. London: Department of Health; 2012. The government's alcohol strategy; pp. 1–32. http://www.dh.gov.uk/health/2012/03/alcohol-strategy-published . [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hastings G, Brooks O, Stead M, et al. Failure of self regulation of UK alcohol advertising. Br Med J. 2010;340:b5650. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hastings G, Brooks O, Stead M, et al. Alcohol advertising: the last chance saloon. Br Med J. 2010;340:184–86. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klein EG, Jones-Webb RJ. Tobacco and alcohol advertising in televised sports: time to focus on policy change. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(2):198. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.102566. author reply 198–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Broadcasters' Audience Research Board (BARB) London: 2011. Weekly top 10 programmes. http://www.webcitation.org/query?Url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.barb.co.uk%2Freport%2Fweekly-viewing%3F_s%3D4&date=2011-10-07. (26 July 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]