Abstract

Background

The power to influence many social determinants of health lies within local government sectors that are outside public health's traditional remit. We analyse the challenges of achieving health gains through local government alcohol control policies, where legal and professional practice frameworks appear to conflict with public health action.

Methods

Current legislation governing local alcohol control in England and Wales is reviewed and analysed for barriers and opportunities to implement effective population-level health interventions. Case studies of local government alcohol control practices are described.

Results

Addressing alcohol-related health harms is constrained by the absence of a specific legal health licensing objective and differences between public health and legal assessments of the relevance of health evidence to a specific place. Local governments can, however, implement health-relevant policies by developing local evidence for alcohol-related health harms; addressing cumulative impact in licensing policy statements and through other non-legislative approaches such as health and non-health sector partnerships. Innovative local initiatives—for example, minimum unit pricing licensing conditions—can serve as test cases for wider national implementation.

Conclusions

By combining the powers available to the many local government sectors involved in alcohol control, alcohol-related health and social harms can be tackled through existing local mechanisms.

Keywords: alcohol, government and law, public health

Introduction

In common with many non-communicable diseases, alcohol-related health harms result from a broad range of social, economic and political determinants that are affected by policies made in a number of non-health sectors.1 Recognizing this, the Health in All Policies movement calls for health professionals to work synergistically with non-health sectors to negotiate policy changes that enhance health and well-being.2 A range of non-health sectors share concerns regarding alcohol-related harms—in particular crime, disorder and lost economic productivity3—presenting an opportunity for incorporating health goals across alcohol control policies. Yet broadly similar aims belie differences in how sectors prioritize alcohol control interventions,1 in particular the relative policy importance of targeting acute intoxication or chronic overconsumption. While many determinants impact on both acute and chronic harms—for example alcohol outlet density is associated with violence,4 assault5 and health6—the relative magnitude of this impact may differ. Whether a government body is concerned with the immediate or long-term effects of alcohol consumption not only influences its policy preferences, but also leads to distinct operating principles and practices that may be at odds with population health considerations.

Alcohol consumption is regulated by a complex mix of government institutions that act within country-specific legal and political contexts.7 In England and Wales, local governments are directly responsible for controlling alcohol provision through licensing, planning and trading standards.8 However, local government powers are limited to activity within a national framework of prescribed legal considerations and policy objectives.9 This legal framework focuses predominantly on balancing individual liberties and economic considerations with immediate societal harms resulting from acute alcohol intoxication.10

Systematic reviews,6,11,12 national13 and international guidelines14 consistently emphasize the health importance of reducing the affordability and physical availability of alcohol. The most effective interventions from a health perspective include reducing licensed alcohol outlet density,6 their opening days and times,6 increasing taxation12 and minimum unit pricing.15 Conversely, standalone server or design interventions for on-premises are less consistently effective16–18 and less likely to impact on chronic consumption. In keeping with this evidence, the UK Government's 2012 alcohol strategy included pledges to introduce national minimum unit pricing and to consult on proposals to ban off-trade multi-buy promotions and introduce a cumulative impact health licensing objective for local alcohol policy.19 However, despite positive progress in Scotland,20 recent government statements suggest these policies are no closer to becoming a reality in England.21

Public health practitioners tackling alcohol-related health harms are therefore faced with a paradox: interventions with the most evidence supporting their effectiveness often appear the least feasible to implement. Individual-level interventions, despite good evidence for the effectiveness of brief interventions in reducing alcohol consumption,22 are unlikely to be sufficient in isolation to reduce the 31% of women and 44% of men in England who drink more than recommended weekly alcohol limits.23 Supported by a government focus on the value of ‘localism’, the best opportunities to intervene on the physical availability and affordability of alcohol currently appear to be at the local government level.

This article analyses the implications for local alcohol control of recent changes in alcohol licensing laws and practice in England and Wales. We present UK case studies to show how alcohol-related health harms can be tackled through licensing, planning and local partnerships. While this legal framework is specific to England and Wales, the challenge of reconciling population health needs with the legal and political principles governing alcohol regulation is internationally relevant.24

Methods

A focused search was conducted in April 2013 to identify laws, legal rulings and government policy documents relevant to current English local government alcohol control policies, processes or practices. Lexis and Westlaw UK database searches identified the legislative framework for local alcohol control in England and Wales, drawing on legal commentary and secondary sources including Halsbury's Laws of England.25 Policy articles were identified from Medline, Web of Science and Google Scholar database searches; hand-searching relevant non-governmental and local government websites and contacting key experts from local government and non-governmental organizations.

Documents were reviewed and analysed for their implications for the ability of local government practitioners to enact effective policies to address alcohol-related health harms. Policy implementation processes were analysed by drawing on the authors' prior legal, public health and policy experiences, combined with contacting key informants known to the researchers for non-audio recorded discussions of policy implementation to ensure the accuracy of our process descriptions. Case studies are presented as exemplars to highlight key aspects of current legislation.

Results

Current English National Legislation

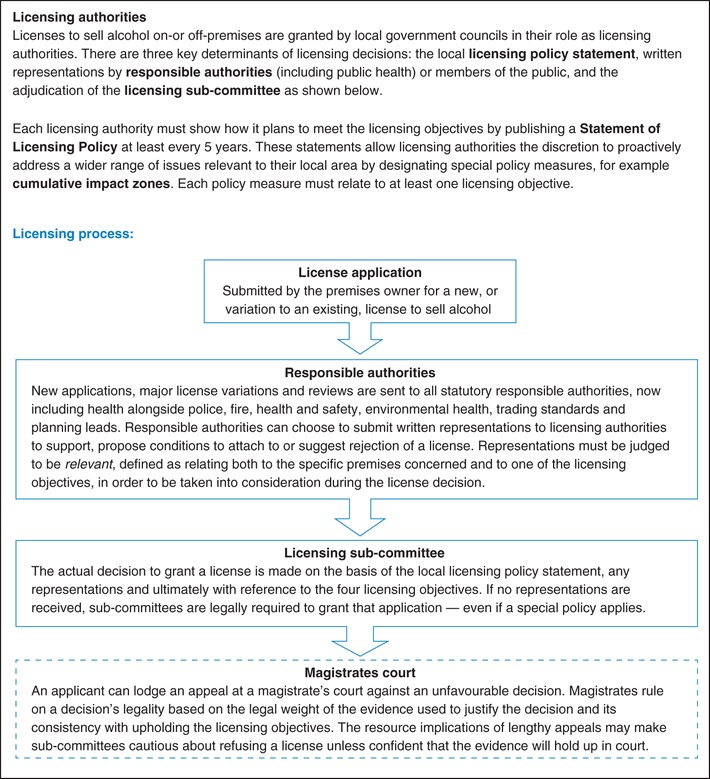

Powers to control local alcohol supply and consumption are established by the Licensing Act 2003,26 which transferred authority for granting and reviewing licenses from magistrate courts to local authorities. Implemented in 2005, the Act sets out the licensing process (Box 1) and defines the statutory licensing objectives that legally underpin all licensing activities (Box 2). The Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011 granted health leads a statutory role in the licensing process for the first time27 and gave local authorities additional powers to address the cumulative impact of alcohol sales.28 The recent return of public health to local authorities presents additional opportunities for cross-sector collaboration on shared objectives.29 In contrast with Scotland, potential health opportunities arising from this new legislation in England and Wales must contend with the absence of a statutory health licensing objective.30

Box 1 Overview of the process and legal framework governing licensing decisions in England and Wales

Box 2 Licensing objectives in England and Wales as defined by the Licensing Act (2003)

Prevention of crime and disorder: based on police advice concerning, preventing crime and maintaining order.

Public safety: physical safety of people using a premises, immediate harms, e.g. accidents, injuries, unconsciousness.

Prevention of public nuisance: noise nuisance, light pollution, noxious smells, litter and where an ‘effect is prejudicial to health’.

Protection of children from harm: moral, psychological and physical harm, including underage sale of alcohol.

Health and alcohol licensing

Local health leads in England and Wales have, as Responsible Authorities, a recognized role in commenting on all licensing applications, yet evidence they present must legally be framed in terms of non-health objectives. The licensing process (Box 1) is primarily a method for controlling immediate harms associated with alcohol sales at a particular premises.31 All license decisions must relate specifically to the premises in question and the promotion of the four statutory licensing objectives (Box 2). Government guidance explicitly states that public health should not be the primary consideration for a licensing decision, although health considerations can support concerns regarding a statutory licensing objective.28 Alcohol-related injury rates, for example, are considered relevant to public safety. Rates of chronic conditions, on the other hand, are harder to link directly with any of the four licensing objectives, despite accounting for 75% of alcohol-related hospital admissions in England.32

Licensing authorities can only consider health-related evidence that directly links the premises in question to a threat to one of the named licensing objectives (Box 2).28 The more specifically evidence relates to the premises or location of concern, the greater its legal weight and the less vulnerable it is to appeal. Routine health data, rarely collected in a way that can be linked to individual premises, are unlikely to be considered relevant.8 Representations are weighed against supporting ‘evidence’ produced by applicants—an area where pub or supermarket chains hold an advantage, since evidence of good operating practice by their company elsewhere is considered relevant to new applications.

The practical challenges of acquiring sufficiently detailed health data to support licensing decisions must be weighed against the potential consequences of submitting weakly justified health representations. Repeated submissions based on health evidence that is unrelated to the licensing objectives, or not deemed ‘relevant’ to the applicant, may weaken the credibility of future representations to the licensing sub-committee. Conversely, and somewhat paradoxically, not submitting a health representation for an application may be interpreted as evidence that the application holds no health threat. A 2008 high court decision suggests that the absence of expert representation—in this case by the police—signified that there were no serious concerns about the impact on licensing objectives within that responsible authority's domain of expertise.33

Despite these limitations, there remain a number of opportunities for addressing population health through licensing.

Statements of licensing policy

Licensing policy statements can be powerful tools to support and coordinate local government actions against alcohol-related harms. Licensing statements, open to challenge on appeal or by way of judicial review, must still be consistent with promoting the four licensing objectives.28 They do, however, allow for broader responses to alcohol consumption above the individual premises level34 by designating special policies or establishing the local relevance of particular licensing approaches.

Special policies can be implemented to address area-wide impacts of alcohol consumption, namely: cumulative impact zones (CIZs), early morning restriction orders and late night levies. Policy statements can also document population-level data, including health impacts, at a higher spatial scale than individual license decisions allow. Using policy statements to clearly set out a licensing authority's reasoning and justification for a licensing approach, backed up by appropriate local evidence, can make individual representations more legally robust while reducing the time needed to write them.34 This could include, for example, establishing a health rationale for limiting the density of alcohol premises using rates of local alcohol-related hospital admissions.

Addressing cumulative impact

Local authorities can designate CIZs to control new on- or off-premises alcohol outlets in areas where the cumulative stress caused by existing overprovision of alcohol outlets demonstrably threatens the licensing objectives.28,35 Licensing decisions are normally made with a presumption in favour of the applicant. Under a CIZ, the burden of proof is reversed and it is the applicant who must demonstrate how they will avoid threatening the licensing objectives. CIZs do not, however, affect existing license holders and decisions are still made on a case-by-case basis. For example, an initial refusal to grant a license within a CIZ in Leeds was overturned on appeal due to the applicant's short opening hours, clientele and history of running trouble-free premises.36

Although yet to be implemented by any local authority, early morning restriction orders (EMRO) and late night levies (LNL) offer additional mechanisms for controlling alcohol sales from both on- and off-premises between 12 and 6 a.m. EMROs are designed to address recurrent licensing objective infringements that are not attributable to a single premises, such as night time anti-social behaviour.28 They impose a blanket closing time by prohibiting alcohol provision at specified hours. LNLs recoup financial costs associated with late night alcohol provision by levying a charge on any premises licensed to sell alcohol between specified night hours.37 Acting outside of the licensing process, EMROs and LNLs are decided on an area rather than individual-premises basis. LNLs must apply to the whole of a licensing authority's area, while EMROs can apply to selected parts of this area.

Developing relevant local health evidence

The absence of a health licensing objective does not preclude addressing health needs where they concern other licensing objectives. Producing specific evidence linking local alcohol consumption practices with licensing objectives does, however, require a change of approach from traditional local health data analysis, demonstrated by the ongoing difficulties Scottish licensing boards face in reflecting health evidence in licensing decisions (Box 3) even since the introduction of an explicit public health licensing objective.38 More successfully, the Cardiff Model39 has pioneered the production of detailed local health data for use by non-health sectors. Linking anonymized data on alcohol-related injuries with the precise location of where the injury occurred provides evidence that is highly relevant to the public safety objective.40

Box 3 Case study: Scotland's experience of a public health licensing objective

Licensing policy in Scotland

In contrast to England and Wales, Scottish licensing decisions have been required to promote a fifth licensing objective—‘protecting and improving public health’—as set out in the Licensing (Scotland) Act 2005,38 implemented in 2009. Two years after implementation, a report by Alcohol Focus Scotland concluded that the potential to tackle alcohol-related health harms through this objective had not been met.34

A major barrier identified was the discrepancy between the population perspective of public health considerations and the case-by-case perspective of licensing decisions. In practice, the public health objective in most Scottish licensing statements has most commonly equated to the provision of health information in licensed premises. The few licensing boards who did recognize population-level health determinants, including the overprovision of alcohol, justified their policy positions using systematically gathered and analysed evidence that they documented in policy statements.

What international lessons can be learnt from Scotland's experience of a health licensing objective? First, broadening the scope of alcohol control frameworks to explicitly address health concerns does not change the underlying legal principles governing individual licensing decisions. Health evidence needs to be legally relevant as well as scientifically valid. Secondly, population-level evidence can nevertheless be used to justify local policy positions and, to a degree, mitigate legal uncertainty regarding individual licensing decisions.

Even without a health licensing objective, there are examples of licensing authorities in England and Wales establishing the relevance of certain health indicators to current licensing objectives within their policy statements, including child protection cases, domestic violence, alcohol-related injuries and under-18 health attendances associated with alcohol.50 While not fully reflecting the health harms caused by alcohol consumption, such indicators—if linked specifically enough with a particular area or premises—can be used to justify licensing decisions even without further national legislative changes.

Innovations by a number of local authorities demonstrate that the existing licensing objectives in England and Wales can promote health needs even in the absence of a legal public health objective. While isolated licensing rulings on individual premises are unlikely to impact considerably on health, case studies give an indication of what the licensing process allows and examples of how local authorities can implement innovative policy ahead of national regulation.

Local government collaboration

Arguably the greatest strengths of recent legislative and organizational changes are the new opportunities for collaboration within local government to address a broad range of alcohol-related harms. Box 4 gives an example of where a commitment across Newcastle City Council to tackle alcohol-related harms has led, among other initiatives, to the introduction of minimum unit pricing license conditions for certain premises. Planning processes and strategic partnerships are two opportunities to align strategic alcohol goals across sectors including planning, trading standards, police and community safety as well as public health.

Box 4 Case studies: local authority interventions addressing alcohol affordability in Newcastle and Westminster

As part of a pro-active council-wide approach to tackling alcohol harms, Newcastle City Council have recently granted new licenses for a small number of premises on the condition that they agree to a minimum unit pricing policy.49 The MUP condition is one of a number of cross-sectoral initiatives addressing alcohol overprovision and overconsumption. Set at £1.25/unit, significantly higher than the MUP level proposed nationally, this condition has been introduced for bars applying for licenses in one street covered by one of a number of cumulative impact policies.51

So far, this condition has only been applied to high-end on-premises licensees who would probably have priced their drinks above the minimum level even without the condition—the impetus behind these conditions was precautionary to protect against the future transfer of the license to owners with business models based around large volume sales of heavily price-promoted drinks.

Nevertheless, this example joins cases elsewhere of licensing authorities implementing health-relevant policies despite the absence of a health objective. For example, Westminster Council have granted a supermarket license with a condition banning drinks promotions.52 These demonstrate the potential for health leads to use existing statutory powers available to local governments to address population-level determinants of alcohol-related health harms.

New alcohol outlets must hold planning permission in addition to an alcohol license. In contrast to licensing, the legal framework governing planning is broad enough to include the goal of health promotion. Furthermore, there is precedence for using spatial planning to improve health through regulating the concentration and proximity of takeaway food outlets.41 Where licensing and planning conditions differ, a premises must comply with both, for example by observing whichever specified closing time is earliest. There is therefore scope for addressing long-term population health impacts by controlling local alcohol availability through local development frameworks and development plans.

Partnership working has formed an important part of local alcohol control policy for many years42 and is encouraged in the government's alcohol strategy.19 Where individual partners' interests conflict with the partnership's overall aims, however, such collaborations may not be effective.42 Alcohol industry partnerships, including Community Alcohol Partnerships, may prioritize individual-focused interventions such as health information campaigns over more effective population-level regulation.43 Joint Strategic Needs Assessments or strategic partnerships led by local government, for example the Safer Newham Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnership,44 may offer more effective ways of simultaneously addressing a broad range of alcohol harms.

Discussion

Main findings of this study

This article describes the mechanisms currently available for addressing alcohol-related health harms at a local level in England and Wales. While decisions regarding specific policy interventions depend on the particular needs and context of the target population, our analysis clarifies which interventions local practitioners can feasibly implement. Although the current licensing framework imposes a number of constraints on public health, local government interventions continue to be one of the most important ways of addressing alcohol-related health harms.

At present, licensing decisions must be framed around non-health arguments and processes. Local alcohol policy currently focuses on criminal justice and the immediate management of drunkenness.31 This holds important implications for addressing alcohol-related diseases caused by chronic overconsumption. In contrast to the routine public health data and evidence reviews that public health practitioners are more commonly familiar with, licensing committees need data and arguments specific to the individual geography of the premises or circumstances of the applicant. Although it is important to recognize and respect individual rights within the licensing legal framework, public health needs to find ways to highlight the considerable burden of alcohol harms in licensing processes.

Local public health efforts can be supported nationally in a number of ways. Developing resources including evidence reviews, evaluation tools and case studies of best practice will strengthen local representations. Providing evidence linking local contexts to alcohol harm will support appropriate licensing policy statements by, for example, justifying how alcohol outlet density influences drinking behaviour. Advocating for the addition of a health licensing objective would allow licensing decisions to reflect the growing evidence for alcohol-related health harms and make health representations less burdensome on already overstretched health leads. Without a public health licensing objective, health leads face the prospect of being responsible for addressing the potential health harms of granting a license without the clear legal authority to do so.

What is already known on this topic

Licensing has largely confined its focus to on-premises45 and immediate harms associated with alcohol consumption.31 Recent alcohol legislation emphasizes personal freedom over population-level regulation.10 The UK Government's 2012 alcohol strategy19 marks a shift towards public health-oriented alcohol policy;30 however, the majority of this strategy's content has yet to be enacted. The challenges faced by local governments responsible for local alcohol control without appropriate powers to address important health determinants have been described in New Zealand46 and Australia.47

What this study adds

This article adds to the international literature by analysing legal as well as policy frameworks for local alcohol control within England and Wales. Alcohol health concerns can be addressed within the current alcohol control framework by utilizing the potential for cross-sector collaboration within local government. Pre-emptive data collection to support representations and identify priority areas can improve effectiveness while reducing costs. Such data can justify cumulative impact policies and support license policy statements. Aligning local planning policy with licensing can improve the long-term control of alcohol availability. Finally, local partnerships can harness mechanisms from across local government to address shared concerns related to alcohol consumption. Joint Strategic Needs Assessments and Joint Health and Well-being Strategies are two mechanisms for public health to collaborate with non-health sectors, but it is important to work with other powerful allies including the police and community safety.

Limitations

Our legal analysis is specific to England and Wales; details of our findings cannot be assumed to apply directly to other legal contexts. However, the challenges of overcoming the tensions between tackling acute and chronic, social and health harms caused by alcohol consumption while respecting individual freedoms are likely to apply to alcohol policy-making in all contexts. Our findings should be interpreted alongside other country-specific policy analyses46 and international alcohol policy comparisons.7,48

Conclusion

Despite health not being a legally recognized licensing objective, our analysis demonstrates how public health practitioners can address local health consequences of alcohol consumption in England through non-health sector policies. Important barriers to working collaboratively across sectors include differences in prioritizing interventions and the types of evidence that can be used to justify policy decisions. Collaborations with non-health sectors are more likely to succeed if these differences are understood and addressed.

There is, however, a limit to what can be achieved at a local level. An effective alcohol policy requires action at the individual, local and national levels. This includes using the greater fiscal control available to the national government to upholding pledges to reduce alcohol affordability, for example by introducing minimum unit pricing and multi-buy promotion bans.45 Successful local implementation of minimum unit pricing as a licensing condition49 or across a province15 could act as test cases for the introduction of similar national policies, thus embedding health objectives more robustly in alcohol policies.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)'s School for Public Health Research (SPHR). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. Funding to pay for the open access charges was provided by the NIHR School for Public Health Research.

References

- 1.Anderson P, Casswell S, Parry C, et al. Chapter 11: Alcohol. In: Leppo K, Ollila E, Peña S, et al., editors. Health in All Policies Seizing Opportunities, Implementing Policies. Finland: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sihto M, Ollila E, Koivusalo M. Principles and challenges of health in all policies. In: Ståhl T, Wismar M, Ollila E, et al., editors. Health in All Policies Prospects and Potentials. Finland: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu L, Gorman DM, Horel S. Alcohol outlet density and violence: a geospatial analysis. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39:369–75. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Livingston M. Alcohol outlet density and assault: a spatial analysis. Addiction. 2008;103:619–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popova S, Giesbrecht N, Bekmuradov D, et al. Hours and days of sale and density of alcohol outlets: impacts on alcohol consumption and damage: a systematic review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:500–16. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brand DA, Saisana M, Rynn LA, et al. Comparative analysis of alcohol control policies in 30 countries. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Local Government Association. London: Local Government Association; 2013. Public health and alcohol licensing in England. LGA and Alcohol Research UK briefing. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson D, Game C. Local Government in the United Kingdom. 4th edn. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicholls J. Time for reform: alcohol policy and cultural change in England since 2000. Br Polit. 2012;7:250–71. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martineau F, Tyner E, Lorenc T, et al. Population-level interventions to reduce alcohol-related harm: an overview of systematic reviews. Prev Med. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.06.019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.06.019. (27 June 2013, date last accessed) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagenaar AC, Tobler AL, Komro KA. Effects of alcohol tax and price policies on morbidity and mortality: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2270–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.186007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Excellence NIfHaC. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2010. NICE public health guidance 24. Alcohol-use disorders: preventing the development of hazardous and harmful drinking. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babor T, Caetano R, Casswell S, et al. Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity. Research and Public Policy. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stockwell T, Zhao J, Giesbrecht N, et al. The raising of minimum alcohol prices in Saskatchewan, Canada: impacts on consumption and implications for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:e103–10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolier L, Voorham L, Monshouwer K, et al. Alcohol and drug prevention in nightlife settings: a review of experimental studies. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46:1569–91. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.606868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brennan I, Moore SC, Byrne E, et al. Interventions for disorder and severe intoxication in and around licensed premises, 1989–2009. Addiction. 2011;106:706–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones L, Hughes K, Atkinson AM, et al. Reducing harm in drinking environments: a systematic review of effective approaches. Health Place. 2011;17:508–18. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Home Office. London: HM Government; 2012. The government's alcohol strategy. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Judiciary of Scotland. Scotland: Outer House, Court of Session; 2013. Petition for judicial review of the alcohol (minimum pricing) (Scotland) Act 2012 and of related decisions. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scally G. Crunch time for the government on alcohol pricing in England. BMJ. 2013;346:f1784. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD004148. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boniface S, Shelton N. How is alcohol consumption affected if we account for under-reporting? A hypothetical scenario. Eur J Public Health. 2013 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt016. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckt016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang Y-L, Xiang X-J, Wang X-Y, et al. Alcohol and alcohol-related harm in China: policy changes needed. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:270–6. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.107318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halsbury's Laws of England. 5th edn. London: LexisNexis; [Google Scholar]

- 26.London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office; 2003. Licensing Act England and Wales. [Google Scholar]

- 27.London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office; 2011. Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Home Office. London: The Stationary Office; 2012. Amended guidance issued under Section 182 of the Licensing Act 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Department of Health. London: Department of Health; 2011. Public Health in local government. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicholls J. The government alcohol strategy 2012: alcohol policy at a turning point? Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 2012;19:355–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hadfield P, Mesham F. London: The Portman Group; 2011. Lost orders? Law enforcement and alcohol in England and Wales. Final Report. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lifestyle Statistics HaSCIC. London: Government Statistical Service; 2013. Statistics on alcohol: England, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33.2008. R (Daniel Thwaites PLC) v Wirral Borough Magistrates Court. Sect. 55 EWHC 838 (Admin)

- 34.MacNaughton P, Gillan E. 2011. Re-thinking alcohol licensing: alcohol focus Scotland/Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems.

- 35.Department for Culture, Media, and Sport. London: Department for Culture, Media and Sport; 2007. Guidance issued under section 182 of the Licensing Act 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.2012. R (Brewdog Bars Limited) v Leeds City Council. Note of decision of District Judge Anderson 6th September 2012.

- 37.Home Office. London: Home Office; 2012. Amended guidance on the late night levy. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scottish Executive. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive; 2007. Licensing (Scotland) Act 2005—Section 142—guidance for licensing boards. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shepherd J. Cardiff, Wales: Cardiff University; 2007. Effective NHS contributions to violence prevention—The Cardiff Model. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Home Office Alcohol Policy Team. London: Home Office; 2012. Additional guidance for health bodies on exercising new functions under the Licensing Act 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.London Borough of Barking and Dagenham. London: London Borough of Barking and Dagenham; 2010. Saturation point: addressing the health impacts of hot food takeaways. Supplementary Planning Document. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thom B, Herring R, Bayley M, et al. Partnerships: A Mechanism for Local Alcohol Policy Implementation. London: Alcohol Research UK (formerly the Alcohol Education and Research Council); 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hawkins B, Holden C, McCambridge J. Alcohol industry influence on UK alcohol policy: a new research agenda for public health. Crit Public Health. 2012;22:297–305. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2012.658027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newham Borough Council. London: Newham Borough Council; 2012. Safer Newham Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnership Strategic Assessment 2011–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45.University of Stirling. Stirling, UK: University of Stirling; 2013. Health First. An evidence-based alcohol strategy for the UK. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maclennan B, Kypri K, Room R, et al. Local government alcohol policy development: case studies in three New Zealand communities. Addiction. 2013;108:885–95. doi: 10.1111/add.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Livingston M, Chikritzhs T, Room R. Changing the density of alcohol outlets to reduce alcohol-related problems. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26:557–66. doi: 10.1080/09595230701499191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crombie IK, Irvine L, Elliott L, et al. How do public health policies tackle alcohol-related harm: a review of 12 developed countries. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:492–9. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newcastle City Council. Newcastle Leads Way on Minimum Pricing, 2012 (22/3/2013). http://www.newcastle.gov.uk/news-story/newcastle-leads-way-minimum-pricing. (22 March 2013, date last accessed)

- 50.Newcastle City Council Licensing Committee. Newcastle, UK: Newcastle City Council; 2013. A review of the statement of licensing policy, 2013 to 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Newcastle City Council. Premises License: 13/00021/PREM, 77 Grey Street. 2013 http://publicaccess.newcastle.gov.uk/online-applications/licencingDetails.do?ActiveTab=conditions&keyVal=MG0B5XBS00M00. (22 March 2013, date last accessed)

- 52.2009. Licencing Sub-Committee No. 5. Licensing reference 08/10057/LIPV, 15 January 2009. Westminster City Council.