Abstract

Objectives

To review neurological complications after the influenza A (H1N1) pdm09, highlighting the clinical differences between patients with post-vaccine or viral infection.

Design

A search on Medline, Ovid, EMBASE, and PubMed databases using the keywords “neurological complications of Influenza AH1N1” or “post-vaccine Influenza AH1N1.”

Setting

Only papers written in English, Spanish, German, French, Portuguese, and Italian published from March 2009 to December 2012 were included.

Sample

We included 104 articles presenting a total of 1636 patient cases. In addition, two cases of influenza vaccine-related neurological events from our neurological care center, arising during the period of study, were also included.

Main outcome measures

Demographic data and clinical diagnosis of neurological complications and outcomes: death, neurological sequelae or recovery after influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 vaccine or infection.

Results

The retrieved cases were divided into two groups: the post-vaccination group, with 287 patients, and the viral infection group, with 1349 patients. Most patients in the first group were adults. The main neurological complications were Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) or polyneuropathy (125), and seizures (23). All patients survived. Pediatric patients were predominant in the viral infection group. In this group, 60 patients (4.7%) died and 52 (30.1%) developed permanent sequelae. A wide spectrum of neurological complications was observed.

Conclusions

Fatal cases and severe, permanent, neurological sequelae were observed in the infection group only. Clinical outcome was more favorable in the post-vaccination group. In this context, the relevance of an accurate neurological evaluation is demonstrated for all suspicious cases, as well as the need of an appropriate long-term clinical and imaging follow-up of infection and post-vaccination events related to influenza A (H1N1) pdm09, to clearly estimate the magnitude of neurological complications leading to permanent disability.

Keywords: AH1N1 pandemic, influenza, neurological events

Introduction

In 2009, a new strain of swine-originated influenza A (H1N1) caused the first pandemic of the 21st century.1 Clinical manifestations of influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 infection ranged from mild symptoms to severe illness and death. Most patients with severe or fatal disease were reported to have underlying medical conditions, including chronic lung disease, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, neurological disease, and pregnancy;2–4 nevertheless, some individuals developed neurological complications without having underlying comorbidity. In fact, neurological complications associated with either vaccination or infection events are well described in influenza.5–7

Here, we present a literature review of influenza-related neurological complications related to influenza A (H1N1) pdm09, highlighting the different clinical outcomes between those patients who developed neurological complications after vaccination and viral infection, respectively. Additionally, two vaccine-related neurological complications observed in our own neurological care center in Mexico are reported.

Methods

Literature review from March 2009 to December 2012

We conducted systematic searches in Ovid, Medline, EMBASE, and PubMed databases using the keywords “neurological complications of Influenza AH1N1” or “post-vaccine Influenza AH1N1” to identify published papers on this topic. Two clinical neurologists (C.G. and D.-A.A.) performed a full-text review of the papers and extracted all relevant data. Inclusion criteria for this review included studies reporting basic clinical data on influenza-related neurologically defined events, laboratory data confirming influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 infection and at least age-group information (adults versus pediatrics), because in most cases, a precise age was missing. In those cases reporting the age, pediatric patients were considered as <16 years old, both for infection and post-vaccine events. Only papers written in English, Spanish, German, French, Portuguese, and Italian were included. Those papers written in other languages or poorly written because of lacking relevant clinical and epidemiological data were excluded. Additionally, two adult patients with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) post-influenza A H1N1 vaccination studied at a Mexican neurological care center are reported.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS statistics 20 Inc., Somers, NY, USA). Qualitative variables were expressed in percentages and compared using chi-square test with Yates correction. Differences between continuous variables were evaluated using a Student's t-test. A P < 0·05 was considered as significant. Charts were created using the R platform. http://www.r-project.org/

Results

A total of 115 articles were initially retrieved, but eleven of them were eliminated according to our exclusion criteria. Finally, considering our inclusion criteria, only 104 articles (1636 patients) were included and divided into two groups, according to the origin of neurological complications: influenza vaccine-related (287 patients) or viral infection-related (1349 patients) (Tables S1 and S2).5–108 The main characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Neurological complications due to Influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 post-vaccination and infection

| Post-vaccine (%) | Infection (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | |||

| Pediatric | 37 (2.9) | 1256(97.1) | 0.0001* |

| Adult | 250 (72.9) | 93 (27.1) | |

| Time of clinical symptoms (days) | 8.73 ± 7.8 | 3.17 ± 2.8 | 0.06** |

| Clinical manifestations | |||

| GBS or cranial neuropathy | 125 (64.1) | 70 (35.9) | 0.0001* |

| Seizures and status epilepticus | 23 (5.9) | 369 (94.1) | 0.0001* |

| ADEM | 20 (71.4) | 8 (28.6) | 0.0001* |

| Encephalitis-Encephalopathy | 41 (8.0) | 471 (92) | 0.0001* |

| Stroke | 7 (36.8) | 12 (63.2) | 0.1* |

| Myelitis | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | 0.1* |

| Others | 68 (12.7) | 469 (87.3) | 0.0001* |

| Clinical outcome | |||

| Improvement | 287 (19.1) | 1218 (80.9) | 0.0001* |

| Death | 0 | 60 (100) | |

| Total of patients registering clinical outcome | 287 | 1349 | |

GBS, Guillain-Barré syndrome; ADEM, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Statistically significant differences are in bold.

Chi-square test with Yates correction,

Student's t-test.

Neurological complications related to post-vaccine events

Post-vaccine-related neurological complications were observed in 287 patients. From these, 54 were male and 14 female, and there was no information on gender for the remaining patients (219). Mean age was 30·16 ± 25 years. Neurological complications consisted mainly of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) or, polyneuropathy (125), seizures (23), acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) (20), encephalopathy-encephalitis (41), stroke (7), transverse myelitis (3), and others (68). All patients survived and permanent sequelae were reported in 2 (0·69%). CSF-cytochemical characteristics showed 23·55 ± 31·8 cell/μl, 88 ± 28·8 mg/dl of glucose, and 45·97 ± 23·7 mg/dl of protein. While few reports and series provided a neuroimaging pattern, demyelinating lesions were predominant in this group.

Neurological complications related to infection events

Infection-related neurological complications were observed in 1349 patients. Mean age was 12·75 ± 14·6 years. Two hundred and ninety-four were male and 196 female; there was no gender information on the 855 remaining patients. One-thousand two hundred and fifty-six patients (93%) were pediatric and 93 were adults. Forty-nine patients showed previous co-morbidity, mostly previous neurologic disease such as anoxo-ischemic cerebral sequelae, febrile seizures, and myasthenia. In this group, 60 patients (4·7%) died and 52 (30·1%) developed permanent sequelae. CSF-cytochemical characteristics were 67·99 ± 253·5-cells/μl, 63·62 ± 27·5 mg/dl of glucose, and 118·75 ± 381·3 mg/dl of proteins. In 49 patients, previous co-morbidity factors such as obesity, asthma, or other chronic diseases were present. A wide spectrum of neurological complications was observed: encephalopathy-encephalitis (464), seizures or epileptic status (369), stroke (12), ADEM (8), transverse myelitis (4), and others (469).

Comparison between vaccine-related and infection-related events

Some important clinical features registered in both groups were pregnancy, obesity, asthma, and other chronic diseases in 170 patients. Adults were more frequently affected in the post-vaccine group, 250 (72·9%), while children predominated in the infection group, 1256 (97·1%), chi-square value = 914, P = 0·0001. Clinical outcome was less severe in the post-vaccine group than in the infectious group, where more cases of permanent sequels and deadly events were recorded. GBS was prevalent in the post-vaccine group (64·1% versus 35·9%) chi-square value = 328, P = 0·0001), whereas the encephalopathy-encephalitis spectrum predominated in the infection group (92% versus 8%) chi-square value = 45·8, P = 0·0001). It is important to note that deaths were recorded in the viral infection group only, most of them in pediatric age band, 50 of 60 (83·3%). Neuroimaging analysis revealed two main patterns: demyelinating and vascular. The main differences between both groups are summarized in Table 1.

Illustrative cases

Patient 1

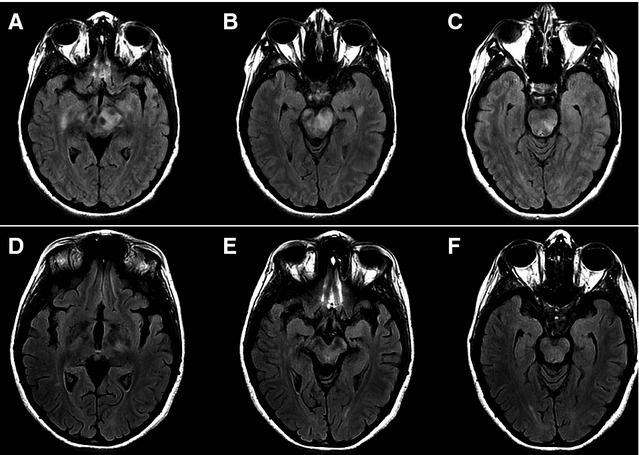

A 27-year-old woman with a history of atopic dermatitis received monovalent inactivated influenza A (H1N1) vaccination on December 2009; 4 weeks later, she presented cephalgia, generalized weakness, progressive left-sided hemiparesis, and hypersomnia. She was evaluated at another institution. CT scan revealed brain edema. CSF-cytochemical analysis showed 81 mg/dl of glucose and 31 mg/dl of proteins without cells. Bacterial and tuberculosis cultures were negative. Serological test against Coxsackie virus, CMV, and cysticerci, as well as CSF-PCR for herpesvirus, were negative. Acute phase reactants were normal. She was treated with acyclovir and corticosteroids for 21 days, with some clinical improvement. Four weeks later, she showed abrupt changes in social behavior and dromomania (an uncontrollable psychological urge to wander). Clinical deterioration progressed with disarthria, paresthesias, and consciousness impairment. Upon admission to our Institution, neurological examination revealed stupor, left-central facial paralysis, hypertonic reflexes, grasp reflexes, persistent postures, generalized rigidity, and a left Babinski sign, making up a catatonic syndrome. MRI scan showed demyelinating lesions involving bilateral basal ganglia and brainstem (Fig.1A–C). A new evaluation with cultures and serological tests was not contributory. The patient received corticosteroids, olanzapine, and lorazepam, with slow improvement. She was discharged 3 weeks later. As an outpatient, complex neuropsychiatric symptoms appeared with hyperorality, hypermetamorphosis (an irresistible impulse to notice and react to everything within sight), and hypersexuality, also known as Klüver-Bucy syndrome. A control MRI scan performed 15 months later showed radiological improvement (Fig.1D–F). During a 27-month follow-up, the patient required multiple hospitalizations at a psychiatric ward for depression and impulsivity with suicidal ideation. She is still under antipsychotic treatment and requires continuous supervision by relatives.

Figure 1.

(A–C) MRI on axial Fast-FLAIR sequence shows demyelinating areas involving gyri rectus, mesencephalon, and pons. (D–F). Control MRI performed 15 months after initial symptoms shows improvement in demyelinating lesions and secondary cortical atrophy.

Patient 2

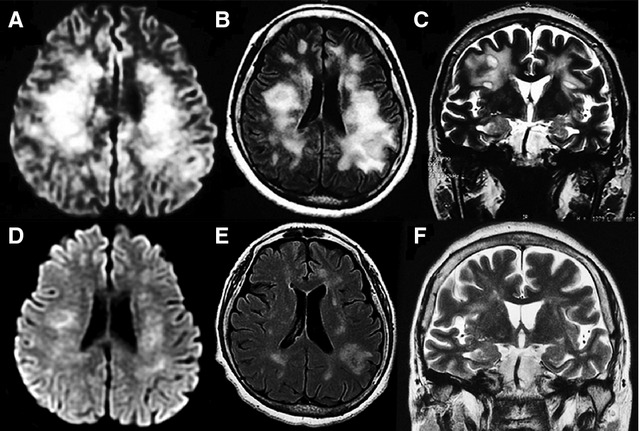

A 64-year-old woman was referred with a 2-month history of treated arterial hypertension and vitiligo, diagnosed 6 months before. She received trivalent inactivated A (H1N1) influenza vaccination on November 2011. One month later, she developed irritability, semantic paraphasias, and memory impairment. Upon neurological examination she was alert, oriented with euthymic mood, low fluent spontaneous speech, and increased latency of verbal responses. She was unable to keep or focus attention; constructional praxis and calculation-abstraction were seriously affected. Clinical findings were consistent with a frontal lobe syndrome. Electroencephalogram showed mild generalized dysfunction. CSF-cytochemical analysis rendered 82 mg/dl of glucose and 26 mg/dl of proteins without cells. PCR-viral panel for herpesvirus family was negative, as well as VDRL, cryptococcal antigen, bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures. Other evaluations, including HIV serology, IgM serology for EBV, CMV, antinuclear antibodies, and antineuronal antibodies, were all negative. A first MRI scan taken 1 month after the initial symptoms showed diffuse cortico-subcortical white matter involvement and edema (Fig.2A–C). Patient was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone for 3 days, followed by oral tapering corticosteroids. On a control MRI scan, 4 months after the symptoms onset (Fig.2D–E), a significant reduction in white matter abnormalities was seen. Neurological improvement has been progressive, and at 6 months of follow-up, the patient still receives rehabilitation and psychotherapy).

Figure 2.

(A–C) MRI on diffusion, Fast-FLAIR, and T2-weighted sequences show extensive demyelinating areas involving subcortical white matter (bilateral centrum semi oval). (D–F) Control MRI performed 4 months after initial symptoms shows ostensible improvement of lesions and secondary subcortical atrophy.

Discussion

Although influenza virus A (H1N1) pdm09 has become a public health threat of global concern,109,110 there are no accurate data regarding the worldwide frequency of neurological complications related to this disease. Here, we reviewed the reported neurological complications from this disease from pandemic onset until December 2012; we found more reports of neurological complications due to the infection itself than to vaccination. The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System estimated that from October 2009 through January 2010, 82·4 million doses of 2009 H1N1 vaccine were administered; death, GBS, and anaphylaxis reports after 2009-H1N1 vaccination were rare (<2 per million doses administered, each).111

On the other hand, WHO aimed to provide access to A (H1N1) pdm09 vaccine for all countries as soon as the vaccine was available and approved. Each recipient country established its vaccination programs, with some degree of variation depending on national priorities. Some chose to vaccinate only specific priority groups, including at least some children and younger adults (including pregnant women), and healthcare workers.112–118 According to our review, fatal cases and permanent neurological sequelae were reported in about 11% of patients with influenza-related neurological complications. With respect to vaccination, aging appears to be related to a higher risk of having neurological sequelae, as in our two reported cases. The clinical outcome was generally more favorable in post-vaccine neurological complications. In fact, no fatalities occurred in this group, but permanent sequelae were observed in 2/287 patients, our two ADEM post-vaccine cases, patients were female and developed severe and complex neuropsychiatric sequelae.

Most patients with neurological complications related to influenza A H1N1 infection developed necrotizing or non-necrotizing encephalopathy; an antecedent of chronic diseases was found in some of these patients.8,9,14,23,31,37,47,48,50,62,64 A number of individual factors such as the patient's age may be involved; children and elderly are the groups with the highest risk of having neurological complications, but also are those suffering underlying immune disorders, chronic diseases, or obesity.119,120 In our review, most neurological complications occurred in the population younger than 16 years (1297 versus 342 cases) Graph.1. This result, along with the pivotal role of the young in spreading the infection, highlights the relevance of enforcing vaccination in this population group, where severe post-vaccination complications are infrequent. There are insufficient details in the published reports about neurological complications related to influenza A (H1N1) infection or vaccination to reveal other individual and circumstantial factors that may participate in the susceptibility or development of such complications, and their optimal management is unknown.

Large population studies of risk factors for influenza have been conducted in both seasonal and influenza A (H1N1) pdm09.119,120 The highest hospitalization rates were found in children; in contrast, higher mortality rates were found in persons over 64 years old. Even though aged population may have a lower risk of infection, they showed a higher risk of death when infected.121

With respect to pathogenesis, while influenza viruses do not seem to show a direct tropism to the nervous system, virus detection within both retina and the olfactory bulb has been described in animal models.121,122 Influenza virus has been also detected by isolation or nested RT-PCR in human cerebrospinal fluid59,74,123,124 on brain tissue in neuropil, ependyma, Purkinje cells, and other neurons.125 Although in most influenza cases, no virus has been detected in CSF, the reported information stresses the relevance of searching for the virus in the central nervous system in different infection stages, particularly when neurological symptoms are present.

On the other hand, other pathogenesis factors may be linked with neurological disorders related to influenza vaccination. As it is reported, the vaccine itself may promote an exacerbated peripheral inflammatory response,126 the extension of which may be modulated by individual biological factors, that is, age, sex, and genetic background. Furthermore, an increased systemic or peripheral inflammatory response may promote neuroinflammation, which may underlie the neurological symptoms observed in the two cases reported herein, and in those published elsewhere.127

In this regard, the severity of brain dysfunction even in cases with non-clinical neurological findings may be correlated with high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in blood and CSF (cytokine storm).128 However, in some cases of CNS involvement, no cytokine storm or tissue inflammatory infiltrate has been found.63,129 It is also possible that both the viral infection and the vaccination promote blood–brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction,130 producing neuroinflammation and neurological disorders. With respect to neurological diseases related to the infection, it is important to consider the higher prevalence of encephalopathy or encephalitis in the pediatric population. The size of the influenza viral particle may prevent it from crossing the barrier in adults, but an immature BBB may be prone to virus invasion.103

Even though our analyses show clear limitations due to the incomplete information in most of the case reports retrieved from medical literature, and also to their descriptive nature, the information reviewed in this article highlights the relevance of an accurate neurological evaluation in all suspicious cases and of an appropriate long-term clinical and imaging follow-up of infection and post-vaccination events related to influenza A (H1N1)pdm09, to clearly estimate the magnitude of neurological complications that could lead to permanent disability.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Juan Francisco Rodriguez for copyediting the English version of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest exists.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Graphic S1. References included in the review Neurological events related to Influenza A (H1N1) pdm09.

Table S1. Description of the different neurological symptoms related to influenza vaccination.

Table S2. Description of the different neurological symptoms related to influenza infection.

References

- 1.Abdel-Haq NM, Asmar BI. Novel swine-origin influenza A: the 2009 H1N1 influenza virus. Indian J Pediatr. 2011;78:74–80. doi: 10.1007/s12098-010-0251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Riordan S, Barton M, Yau Y, et al. Risk factors and outcomes among children admitted to hospital with pandemic H1N1 influenza. CMAJ. 2010;182:39–44. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain S, Kamimoto L, Bramley AM, et al. Hospitalized patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza in the United States, April-June 2009. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1935–1944. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dominguez-Cherit G, Lapinsky SE, Macias AE, et al. Critically I11 patients with 2009 influenza A (H1N1) in Mexico. J Am Med Assoc. 2009;302:1880–1887. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kedia S, Stroud B, Parsons J, et al. Pediatric neurological complications of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) Arch Neurol. 2011;68:455–462. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lapphra K, Huh L, Scheifele DW. Adverse neurologic reactions after both doses of pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine with optic neuritis and demyelination. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:84–86. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181f11126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for disease control and prevention (CDC) Neurologic complications associated with novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in children-Dallas, Texas, May 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:773–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akins PT, Belko J, Uyeki TM, Axelrod Y, Lee KK, Silverthorn J. H1N1 encephalitis with malignant edema and review of neurological complications from influenza. Neurocrit Care. 2010;13:396–406. doi: 10.1007/s12028-010-9436-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yildizdaş D, Kendirli T, Arslanköylü AE, et al. Neurological complications of pandemic influenza (H1N1) in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;170:779–788. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1352-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitcharoen S, Pattapongsin M, Sawayawisuth K, et al. Neurological manifestations of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:569–570. doi: 10.3201/eid1603.091699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen YC, Lo PC, Chang TP. Novel influenza A (H1N1)-associated encephalopathy/encephalitis with severe neurological sequelae and unique image features- A case report. J Neurol Sci. 2010;298:110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park YJ, Suh ES. Guillain-Barré syndrome caused by swine influenza (H1N1) vaccination: a case report. J Korean Child Neurol Soc. 2010;18:108–111. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ormitti F, Ventura E, Summa A, et al. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy in a child during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemia: MR imaging in diagnosis and follow-up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:396–400. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mariotti P, Iorio R, Frisullo G, et al. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy during influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:111–114. doi: 10.1002/ana.21996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webster RI, Hazelton B, Suleiman J, et al. Severe encephalopathy with swine origin influenza A H1N1 infection in childhood: case reports. Neurology. 2010;74:1077–1078. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d6b113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin A, Reade EP. Acute Necrotizing encephalopathy progressing to brain death in a pediatric patient with novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:e50–e52. doi: 10.1086/651501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang J, Wang YG, Xu YL, et al. A(H1N1) influenza pneumonia with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a case report. Biomed Environ Sci. 2010;23:323–326. doi: 10.1016/S0895-3988(10)60071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi SY, Jang SH, Kim JO, et al. Novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) viral encephalitis. Yonsei Med. 2010;51:291–292. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2010.51.2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Citerio G, Sala F, Patruno A, et al. Influenza A (H1N1) encephalitis with severe intracranial hypertension. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010;76:459–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fugate JE, Lam EM, Rabinstein AA, et al. Acute hemorragic leukoencephalitis and hypoxic brain injury associated with H1N1 influenza. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:756–758. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Germán-Díaz M, Pavo-García R, Díaz-Díaz J, et al. Adolescent with neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:570–571. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181d411a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denholm JT, Neal A, Yan B, et al. Acute encephalomyelitis syndromes associated with H1N1 09 influenza vaccination. Neurology. 2010;75:2246–2248. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182020307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noriega LM, Verdugo RJ, Araos R, et al. Pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 with neurological manifestations, a case series. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2010;4:117–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2010.00131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baltagi SA, Shoykhet M, Felmet K, et al. Neurological sequelae of 2009 influenza A (H1N1) in children: a case series observed during a pandemic. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:179–184. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181cf4652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulkarni R, Kinikar A. Encephalitis in a child with H1N1 infection: first case report from India. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2010;5:157–159. doi: 10.4103/1817-1745.76119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez-Torrent L, Triviño-Rodriguez M, Suero-Toledano R, et al. Novel influenza A (H1N1) encephalitis in a 3-month-old infant. Infection. 2010;38:227–229. doi: 10.1007/s15010-010-0014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sachedina N, Donaldson LJ. Paediatric mortality related to pandemic influenza A H1N1 infection in England: an observational population-based study. Lancet. 2010;376:1846–1852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan K, Prerma A, Leo YS. Surveillance of H1N1-related neurological complications. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:142–143. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buccoliero G, Romanelli C, Lonero G, et al. Encephalitis associated to novel influenza A virus infection (H1N1) in two young adults. Recenti Prog Med. 2010;101:307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bedard Marrero V, Osorio Figueroa RL, Vázquez Torres O. Guillain-Barre syndrome after influenza vaccine administration: two adult cases. Bol Asoc Med PR. 2010;102:39–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calitri C, Gabiano C, Garazzino S, et al. Clinical features of hospitalized children with 2009 H1N1 influenza virus infection. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:1511–1515. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1255-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaari A, Bahloul M, Dammak H, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome related to pandemic influenza A (H1N1) infection. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1275. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1895-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kutlesa M, Santini M, Krajinoć V, et al. Acute motor axonal neuropathy associated with pandemic H1N1 influenza A infection. Neurocrit Care. 2010;13:98–100. doi: 10.1007/s12028-010-9365-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyon JB, Remigio C, Milligan T, et al. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy in a child with H1N1 influenza infection. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:200–205. doi: 10.1007/s00247-009-1487-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ekstrand JJ, Herbener A, Rawling J, et al. Heightened neurologic complications in children with pandemic H1N1 influenza. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:762–766. doi: 10.1002/ana.22184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iwata A, Matsubara K, Nigami H, et al. Reversible splenial lesion associated with novel influenza A (H1N1) viral infection. Pediatr Neurol. 2010;42:447–450. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Omari I, Breuer O, Kerem E, et al. Neurological complications and pandemic influenza A (H1N1) vírus infection. Acta Pediatr. 2011;100:e12–e16. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng A, Kuo KH, Yang CJ. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 encephalitis in woman, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1925–1927. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J, Duan S, Zhao J, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis associated with influenza A H1N1 infection. Neurol Sci. 2011;32:907–909. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0500-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choe YJ, Cho H, Bae GR, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome following receipt of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccine in Korea with an emphasis on Brighton Collaboration case definition. Vaccine. 2011;29:2066–2070. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Almeida DF, Teodoro AT, Radaeli Rde F. Transient oculomotor palsy after influenza vaccination: short report. ISRN Neurol. 2011;2011:849757. doi: 10.5402/2011/849757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams SE, Pahud BA, Donofrio PD, et al. Causality assessment of serious neurologic adverse events following 2009 H1N1 vaccination. Vaccine. 2011;29:8302–8308. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Özdemir H, Karbuz A, Çiftçi E, et al. Aseptic meningitis in a child due to 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) infection. Turk J Pediatr. 2011;53:91–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernandes AF, Marchiori PE. Bithalamic compromise in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following H1N1 influenza vaccine. Arq Neuropsiatr. 2011;69:571. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2011000400035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arcondo MF, Wachs A, Zylberman M. Mielitis transversa relacionada con vacunacion anti-influenza A (H1N1) Medicina (Buenos Aires) 2011;71:161–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee ST, Choe YJ, Moon WJ, et al. An adverse event following 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccination: a case of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Korean J Pediatr. 2011;54:422–424. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2011.54.10.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Surana P, Tang S, McDougall M, et al. Neurological complications of pandemic influenza A H1N1 2009 infection: European case series and review. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:1007–1015. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1392-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Willi B, Fahnenstich H, Weber P. Encephalitis after vaccination against H1N1 influenza virus. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2011;15:276–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hasegawa S, Matsushige T, Inoue H, et al. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid cytokine profile of patients with 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus-associated encephalopathy. Cytokine. 2011;54:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kahle KT, Walcott BP, Nahed BV, et al. Cerebral edema and a transtentorial brain herniation syndrome associated with pandemic swine influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:1245–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nowak DA, Griebl G, Bock A. Acute Myelopathy associated with H1N1 virus infection. J Neurol. 2011;258:34–36. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5676-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsai CK, Lai YH, Yang FC, et al. Clinical and radiologic manifestations of H1N1 virus infection associated with neurological complications: a case report. Neurologist. 2011;17:228–231. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e3182173599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Al-Baghli F, Al-Ateeqi Q. Encephalitis –associated pandemic A (H1N1) 2009 in a kuwaiti girl. Med Princ Pract. 2011;20:191–195. doi: 10.1159/000321276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lonchindarat S, Bunnang T. Clinical presentations of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in hospitalized Thai children. J Med Assoc Thai. 2011;94(Suppl 3):S107–S112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McMullan B, Dabscheck G, Robertson P, et al. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza with neurological complications diagnosed using specific serology with the haemagglutinin inhibition assay. Pathology. 2011;43:512–513. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e3283486b46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Augarten A, Aderka D. Alice in Wonderland syndrome in H1N1 influenza: case report. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27:120. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318209af7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fearnley RA, Lines SW, Lewington AJ, et al. Influenza A-induced rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury complicated by posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:738–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lung DC, Lui WY, Ng HL, et al. Hemorrhagic shock and encephalopathy syndrome in a child with pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza virus. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:998–999. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182273c64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sandoval-Gutierrez JL, Arcos M, Alva L, et al. A 22-year-old girl positive for 2009 A H1N1 pandemic influenza. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:217. doi: 10.1002/ana.22293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thampi N, Bitnum A, Banner D, et al. Influenza-associated encephalopathy with elevated antibody titers to pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza. J Child Neurol. 2011;26:501–506. doi: 10.1177/0883073810381128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spalice A, Del Balzo F, Nicita F, et al. Teaching neuroimages: acute necrotizing encephalopathy during novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Neurology. 2011;77:e121. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318238ee56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rellosa N, Bloch KC, Shane AL, et al. Neurologic manifestations of pediatric novel H1N1 influenza infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:165–167. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181f2de6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mukherjee A, Peterson JE, Sandberg G, et al. Central nervous system pathology in fatal swine-origin influenza A H1N1 virus infection in patients with and without neurological symptoms: an autopsy study of 15 cases. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122:371–373. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0854-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Frobert E, Sarret C, Billaud G, et al. Pediatric neurological complications associated with the A (H1N1) pdm09 influenza. J Clin Virol. 2011;52:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Komur M, Okuyaz C, Arslankoylu AE, et al. A. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy associated with novel influenza A (H1N1) virus in Turkey. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61:1237–1239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Launay E, Ovetchkine P, Saint-Jean M, et al. Novel influenza A (H1N1): clinical features of pediatric hospitalizations in two successive waves. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vilà de muga M, Torre Monmany N, Asensio Carretero S, et al. Clinical features of influenza A H1N1 2009: a multicentre study. An Pediatr (Barc) 2011;75:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.anpedi.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Blumental S, Huisman E, Cornet MC, et al. Pandemic A/H1N1 v influenza 2009 in hospitalized children: a multicenter Belgian survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:313. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Linden K, Moser O, Simon A, et al. Transient splenial lesion in influenza A H1N1 2009 infection. Radiologe. 2011;51:220–222. doi: 10.1007/s00117-011-2131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cheng XW, Lu J, Wu CL, et al. Three fatal cases of pandemic 2009 influenza A virus infection in Shezhen are associated with cytokine storm. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;175:185–187. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Poeppl W, Hell M, Herkner H, et al. Clinical aspects of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in Austria. Infection. 2011;39:341–352. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0121-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.del Rosal T, Baquero-Artigao F, Calvo C, et al. Pandemic H1N1 influenza-associated hospitalizations in children in Madrid, Spain. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2011;5:e544–e551. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kwon S, Kim S, Cho MH, et al. Neurologic complications and outcomes of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 of Korean children. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:402–407. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.4.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Honorat R, Tison C, Sevely A, et al. Influenza A (H1N1)-associated ischemic stroke in a 9-month-old child. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:368–369. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31824dcaa4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Okumura A, Tsuji T, Kubota T, et al. Acute encephalopathy with 2009 pandemic flu: comparison with seasonal flu. Brain Dev. 2012;34:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Athauda D, Andrews TC, Holmes PA, et al. Multiphasic acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) following influenza type A (swine specific H1N1) J Neurol. 2012;259:775–778. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6258-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cortese A, Baldanti F, Tavazzi E, et al. Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with D222E variant of the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus: case report and review of the literature. J Neurol Sci. 2012;312:173–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Elliott EJ, Zurynski YA, Walls T, et al. Novel inpatient surveillance in tertiary paediatric hospitals in New South Wales illustrates impact of first-wave pandemic influenza A H1N1 (2009) and informs future health service planning. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012;48:325–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Glaser C, Winter K, Dubray K, et al. A population-based study of neurologic manifestations of severe influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 in California. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:514–520. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vasconcelos A, Abecasis F, Monteiro R, et al. A 3-month-old baby with H1N1 and Guillain Barre syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5462. doi: 10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yeo LL, Paiwal PR, Tambyah PA, Olszyna DP, Wilder-Smith E, Rathakrishnan R. J Complex partial status epilepticus associated adult H1N1 infection. Clin Neurosci. 2012;19:1728–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burad J, Bhakta P, George J, Kiruchennan S. Development of acute ischemic stroke in a patient with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) resulting from H1N1 pneumonia. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2012;50:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.aat.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sugaya N, Shinjoh M, Mitamura K, Takahashi T. Very low pandemic influenza A (H1N1) mortality associated with early neuraminidase inhibitor treatment in Japan: analysis of 1000 hospitalized children. J Infect. 2011;63:288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tokuhira N, Shime N, Inoue M, et al. Writing Committee of AH1N1 Investigators: Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Network. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:e294–e298. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31824fbb10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Khandaker G, Zurynski Y, Buttery J, et al. Neurologic complications of influenza A (H1N1) pdm09: surveillance in 6 pediatric hospitals. Neurology. 2012;79:1474–1481. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826d5ea7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Davis LE. Neurologic and muscular complications of the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2010;10:476–483. doi: 10.1007/s11910-010-0135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Haktanir A. MR imaging in novel influenza A (H1N1) associated meningoencephalitis. Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:394–395. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lister P, Reynolds F, Parslow R, et al. Swine-origin influenza virus H1N1, seasonal influenza virus, and critical illness in children. Lancet. 2009;374:605–607. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61512-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.O'Leary MF, Chappell JD, Stratton CW, Cronin RM, Taylor MB, Tang YW. Complex febrile seizures followed by complete recovery in an infant with high titer 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3830–3835. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00825-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.D'Silva D, Hewagama S, Doherty R, Korman TM, Buttery J. Melting muscles: novel H1N1 influenza A associated rhabdomyolysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:1138–1139. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181c03cf2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Samuel N, Attias O, Tatour S, Brik R. Novel influenza A (H1N1) and acute encephalitis in a child. Isr Med Assoc J. 2010;12:446–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Apok V, Alamri A, Qureshi A, Donaldson-Hugh B. POI02 Fulminant cerebellitis related to H1N1: a first case report. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:e53. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bustos BR, Andrade YF. Acute encephalopathy and brain death in a child with influenza A (H1N1) during the 2009 pandemic. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2010;27:413–416. doi: 10.4067/s0716-10182010000600007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li D, Li XQ. Childhood hemiplegia associated with influenza A (H1N1) infection: a case report. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2010;12:840–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.González-Duarte A, Magaña Zamora L, Cantú Brito C, García-Ramos G. Hypothalamic abnormalities and Parkinsonism associated with H1N1 influenza infection. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:47. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Asadi-Pooya AA, Yaghoubi E, Nikseresht A, Moghadami M, Honarvar B. The neurological manifestations of H1N1 influenza infection; Diagnostic challenges and recommendations. Iran J Med Sci. 2011;36:36–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ozkan M, Tuygun N, Erkek N, Aksoy A, Yildiz YT. Neurologic manifestations of novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in childhood. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;45:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rifkin L, Schaal S. H1N1-associated acute retinitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2012;20:230–232. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2012.674611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Campanharo FF, Santana EF, Sarmento SG, Mattar R, sun SY, Moron AF. Guillain-Barré Syndrome after H1N1 Shot in pregnancy: maternal and Fetal Care in the Third Trimester-Case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:323625. doi: 10.1155/2012/323625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kawashima H, Morichi S, Okumara A, Nakagawa S, Morishima T Collaborating study group on influenza-associated encephalopathy in Japan. National survey of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009-associated encephalopathy in Japanese children. J Med Virol. 2012;84:1151–1156. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Alsanosi AA, Influenza A. (H1N1): a rare cause of deafness in two children. J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126:1274–1275. doi: 10.1017/S0022215112002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pula JH, Issawi A, Desanto JR, Kattah JC. Cortical vision loss as a prominent feature of H1N1 encephalopathy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2012;32:48–50. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e31823fd913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Blum A, Simsolo C. Acute unilateral sensorineural hearing loss due to H1N1 infection. Isr Med Assoc J. 2010;12:450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Li X, Influenza A. (H1N1) virus infection associated with hemiplegia. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:1338–1339. doi: 10.1007/s12098-010-0182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Locuratolo N, Mannarelli D, Colonnese C, et al. Unusual posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in a case of influenza A/H1N1 infection. J Neurol Sci. 2012;321:114–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kumakura A, Iida C, Saito M, et al. Pandemic influenza A-associated acute necrotizing encephalopathy without neurologic sequelae. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;45:344–346. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Farooq O, Faden HS, Cohen ME, et al. Neurologic complications of 2009 influenza-a H1N1 infection in children. J Child Neurol. 2012;27:431–438. doi: 10.1177/0883073811417873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Costiniuk CT, Le Saux N, Sell E, et al. Miller Fisher syndrome in a toddler with influenza A (pH1N1) infection. J Child Neurol. 2011;26:385–388. doi: 10.1177/0883073810382660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Khanna M, Gupta N, Gupta A, et al. Influenza A (H1N1) 2009: a pandemic alarm. J Biosci. 2009;34:481–489. doi: 10.1007/s12038-009-0053-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sejvar JJ. Neurological infections: influenza in the spotlight. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:16–18. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Vellozzi C, Broder KR, Haber P, et al. Adverse events following influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccines reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, United States, October 1, 2009-January 31, 2010. Vaccine. 2010;28:7248–7255. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Australian Government Department of Health. Review of Australia's Health Sector Response to Pandemic (H1N1) 2009: Lessons Identified. Available at: http://www.flupandemic.gov.au/internet/panflu/publising.nsf/content/review-2011/$File/lessons identified-oct11.pdf (Accessed 7 April 2010)

- 113.Department of Health-GOV.UK. UK Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Strategy 2011. Available at: http://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213717/dh_131040.pdf (Accessed 10 November 2011)

- 114. Ministère de la Santé et des Sports, France. Quel vaccine utilizer contre le virus A (H1N1) 2009? December 14, 2009. Available at: http://www.sante-sports.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Dispositions_vaccinales_100129.pdf (Accessed 5 April 2010)

- 115.US Goverment. Use of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccine. recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2009. MMWR. 2009;58:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Government of Sweden. Final summary of adverse drug reaction reports in Sweden with Pandemrix through October 2009- mid April 2010. Available at: http://www.lakemedelsverket.se/upload/engmpa-se/pandemrix ADRs in Sweden 15 april 2010. pdf (Accessed 7 April 2010)

- 117.Kendal AP, MacDonald NE. Influenza pandemic planning and performance in Canada, 2009. Can J Public Health. 2010;101:447–453. doi: 10.1007/BF03403962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Stroud C, Altevogt BM, Butler JC, et al. The Institute of Medicine's Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Catastrophic Events: regional workshop series on the 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccination campaign. Disaster. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2011;5:81–86. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2011.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kwong JC, Campitelli MA, Rosella LC. Obesity and respiratory hospitalizations during influenza seasons in Ontario, Canada: a cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:413–421. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Van Kerkhove MD, Vandemaele KA, Shinde V, et al. Risk factors for severe outcomes following 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection: a global pooled analysis. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001053. (Epub 2011 Jul 5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Belser JA, Wadford DA, Xu J, et al. Ocular infection of mice with influenza A (H7) viruses: a site of primary replication and spread to the respiratory tract. J Virol. 2009;83:7075–7084. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00535-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Majde JA, Bohnet SG, Ellis GA, et al. Detection of mouse-adapted human influenza virus in the olfactory bulbs of mice within hours after intranasal infection. J Neurovirol. 2007;13:399–409. doi: 10.1080/13550280701427069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Morishima T, Togashi T, Yokota S, et al. Encephalitis and encephalopathy associated with an influenza epidemic in Japan. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:512–517. doi: 10.1086/341407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Togashi T, Matsuzono Y, Narita M, et al. Influenza-associated acute encephalopathy in Japanese children in 1994-2002. Virus Res. 2004;103:75–78. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Takahashi M, Yamada T, Nakashita Y, et al. Influenza virus-induced encephalopathy: clinicopathologic study of an autopsied case. Pediatr Int. 2000;42:204–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2000.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Christian LM, Franco A, Iams J, Sheridan J, Glaser R. Depressive symptoms predict exaggerated inflammatory responses to an in vivo immune challenge among pregnant women. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Henry CJ, Huang Y, Wynne AM, Godbout JP. Peripheral lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge promotes microglial hyperactivity in aged mice that is associated with exaggerated induction of both pro-inflammatory IL-1beta and anti-inflammatory IL-10 cytokines. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.To KK, Hung IF, Li IW, et al. Delayed clearance of viral load and marked cytokine activation in severe cases of pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection. Clin Infec Dis. 2010;50:850–859. doi: 10.1086/650581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ito Y, Ichiyama T, Kimura H, et al. Detection of influenza virus RNA by reverse transcription-PCR and proinflammatory cytokines in influenza-virus associated encephalopathy. J Med Virol. 1999;58:420–425. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199908)58:4<420::aid-jmv16>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ichiyama T, Morishima T, Kajimoto M, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase 1 in influenza-associated encephalopathy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:542–544. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31803994a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Graphic S1. References included in the review Neurological events related to Influenza A (H1N1) pdm09.

Table S1. Description of the different neurological symptoms related to influenza vaccination.

Table S2. Description of the different neurological symptoms related to influenza infection.