Abstract

Background

Biomarkers predicting tumor response are important to emerging targeted therapeutics. Complimentary methods to assess and understand genetic changes and heterogeneity within only few cancer cells in tissue will be a valuable addition for assessment of tumors such as prostate cancer that often have insufficient tumor for next generation sequencing in a single biopsy core.

Methods

Using confocal microscopy to identify cell-to-cell relationships in situ, we studied the most common gene rearrangement in prostate cancer (TMPRSS2 and ERG) and the tumor suppressor CHD1 in 56 patients who underwent radical prostatectomy. Contingency tables and the chi-square test were used to determine associations between mutation status of the genes and tumor phenotype.

Results

Wild type ERG was found in 22 of 56 patients; ERG copy number was increased in 10/56, and ERG rearrangements confirmed in 24/56 patients. In 24 patients with ERG rearrangements, the mechanisms of rearrangement were heterogeneous, with deletion in 14/24, a split event in 7/24, and both deletions and split events in the same tumor focus in 3/24 patients. Overall, 14/45 (31.1%) of patients had CHD1 deletion, with the majority of patients with CHD1 deletions (13/14) correlating with ERG-rearrangement negative status (p< 0.01).

Conclusions

These results demonstrate the ability of confocal microscopy and FISH to identify the cell-to-cell differences in common gene fusions such as TMPRSS2–ERG that may arise independently within the same tumor focus. These data support the need to study complimentary approaches to assess genetic changes that may stratify therapy based on predicted sensitivities.

Keywords: Prostate Cancer, ERG, TMPRSS2, Heterogeneity, confocal microscopy, CHD1

Introduction

Efforts to develop targeted therapies based on genomic findings are complicated by the polygenic nature of drug resistance and genetic heterogeneity (1). In addition to the importance of assessment of heterogeneity between separate tumor foci, we hypothesize that the use of complimentary approaches that assess heterogeneity within a single microscopic focus have important implications for predicting targeted drug therapy response and resistance (2) (3). Therefore, we studied the genetic heterogeneity of cells in microscopic foci within single biopsy cores using a confocal microscopy approach to precisely define local cell-to-cell variation, using the commonly found ERG rearrangements in prostate cancer as a model. In fact, the characterization of prostate cancer genomic changes has identified TMPRSS2-ERG fusions as the most frequent chromosomal rearrangement that, with recent studies, has been found to be strongly associated with the presence of the chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 1 (CHD1) gene (4). As studies are underway to understand the functional significance of these findings, data supporting an association of TMPRSS2-ERG and sensitivity to DNA damage has already led to clinical trials to determine if agents targeting DNA damage have differential activity for tumors with TMPRSS2-ERG fusions (5). Similarly, studies of CHD1 have demonstrated it to be a tumor suppressor with its deletion associated with high Gleason score and absence of ERG fusion (6) (7).

Taken together, the identification of these important genomic changes such as TMPRSS2-ERG fusion and CHD1 deletion and the question of tumor heterogeneity supports a thorough analysis of these potentially treatment stratifying biomarkers in biopsy cores. As a complimentary approach to the current literature, we used FISH analysis with confocal microscopy to carefully assess ERG rearrangements and CHD1 to assess local cell-to-cell clonal variation.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Tissues

Using the TMA slides and confocal microscopy, we analyzed a common prostate cancer specific gene rearrangements (TMPRSS2-ERG fusion; CHD1 deletion) in neighboring single cells in a tumor focus. We evaluated 56 patients who underwent radical prostatectomy at the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey with assessment of grading, ERG, TMPRSS2, and CHD1, with institutional review board approval. Tumor foci were identified within prostate cancer cores by pathology, and subjected to Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization and Confocal Microscopy. The average age of patients was 59.1 years (range from 49 to 73).

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

TMA sections (4 mm) were cut onto SuperFrostPlus glass slides. ERG gene rearrangement was assessed using break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization assay as described previously (8) (9). Bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) were obtained from the BACPAC Resource Center (Oakland, CA, USA). For detection of ERG rearrangement and TMPRSS2-ERG fusion, we used the following probes: RP11-95I21 (Alexa Fluor® 555 -labeled; 5′ to ERG) and RP11-476D17 (Alexa Fluor® 488 -labeled; 3′ to ERG) and RP11-35C4 (Alexa Fluor® 647 -labeled; 5′ to TMPRSS2). For detection of CHD1 deletion we utilized a gene-specific DNA probe (RP11-432N19, Alexa Fluor®647-labeled) and reporter probe that corresponded to pericentromeric sequence on human chromosome 5 (RP11-929P16, Alexa Fluor® 555- labeled).

Confocal Microscopy

Labeled samples were scanned using a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510 META, 100x objective). Image stacks of 300 nm z-step size were captured and analyzed using Imaris Software (Bitplane). Gene rearrangement and copy number were evaluated by scoring spots in morphologically intact, non-overlapping interphase nuclei. Assessment was made for ERG, TMRSS2, and CHD1 only in nuclei well defined in which both chromosomes were identified for each gene (mean of 49 nuclei per tumor TMA core for ERG and TMPRSS2 and mean of 74 nuclei per core for CHD1) as described previously (10). Expression of ERG gene in prostate cancer cells were confirmed by IHC using a monoclonal rabbit anti-human ERG antibody (clone EP111, dilurion 1:50, Dako).

Transcriptome Sequencing

Libraries were constructed using the Illumina TruSeq™ RNA Sample Prep Kit v2 (Cat. No. RS-122-2001) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and 100bp paired-end sequencing was performed on the Illumina Hiseq2500. Raw reads from an Illumina HiSeq2500 in fastq format were aligned to a “filter” reference using bowtie to remove adaptor/primer, poly-A, poly-T, rRNA, tRNA, snRNA, and mitochondrial sequence. Reads were then aligned using BWA (version 0.5.9) against the genomic reference sequence for Homo sapiens (Build 37.2). The Homo sapiens (Build 37.2) reference sequence and annotation were pulled from RefSeq database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/).

Statistical Analysis

Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the correlation of ERG rearrangements and CHD1 status (Table 1) and correlation of ERG copy number changes in T2 compared to T3 tumors (Table 2). Assessment of ERG status and CHD1 deletion were compared to Gleason score using the standard Cochran-Armitage trend test and also using an exact version of this trend test, using a permutation test implemented in the “independence_test” function in the “coin” package (http://ww.jstatsoft.org/v28/i08/). Both the standard trend test, which uses the function “prop.trend.test”, and the permutation “coin” package, are software programs implemented in the R statistical system (http://www.R-project.org).

Table 1.

Relationship of ERG and CHD1 gene status in patient tumor assessed by FISH and confocal microscopy

| ERG | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Copy number gain | Rearranged | ||

| CHD1 | Wild type | 7 | 1 | 13 |

| Copy number gain | 0 | 3 | 7 | |

| Deletion | 9 | 4 | 1 | |

Table 2.

Relationship of CHD1 and ERG status with pathological stage*

| CHD1 wt | CHD1 copy | CHD1 del | ERG wt | ERG copy | ERG rearrang | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pT2a unilateral | 1 | 1 | 0 | pT2a unilateral | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| pT2c bilateral | 12 | 3 | 6 | pT2c bilateral | 11 | 1 | 11 |

| pT3a extra prostatic extension | 7 | 4 | 7 | pT3a extra prostatic extension | 11 | 7 | 8 |

| pT3b seminal vesicle invasion | 0 | 1 | 2 | pT3b seminal vesicle invasion | 0 | 2 | 2 |

Number of Patients with identified genomic status in each pathological stage

Results

Confocal Microscopy Identifies Heterogeneity of ERG Rearrangements in Tumor Foci

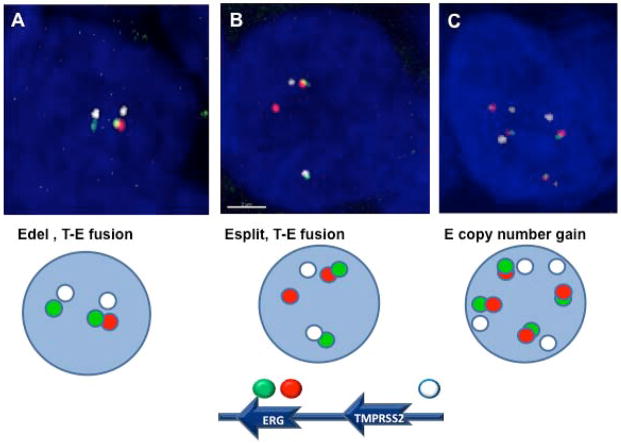

Prostate cancer was assessed in 56 patients treated at the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey. The status of ERG rearrangements in adjacent nuclei of cancer cells was assessed using a combination of break-apart assay for ERG gene and additional FISH probe for conformation fusion with TMPRSS2 gene within each nucleus by confocal microscopy. As shown in Figure 1A and 1B, the status of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion was identified within each single nucleus, and whether the mechanism of fusion was through either ERG deletion (Edel) or a split with translocation of the ERG gene (Esplit). Increased ERG copy number without associated fusion was also characterized, as shown in Figure 1C.

Figure 1. FISH and confocal microscopy assessment of ERG rearrangements.

For detection of ERG rearrangements and TMPRSS2-ERG (T-E) fusion, we utilized multicolor interphase FISH and confocal microscopy. The intact ERG allele is designated by juxtaposition of red and green signals. The T-E gene fusion through deletion (Figure 1A: Edel, T-E fusion) was detected as the absence of a red signal and juxtaposition remaining green (3′ to ERG) and white (TMPRSS2) signals. The split of red and green signals represents rearrangement of ERG gene through split and translocation (Figure 1B: Esplit, T-E fusion). Copy number gain of ERG gene represent polysomy of intact ERG and TMPRSS2 alleles (Figure 1C).

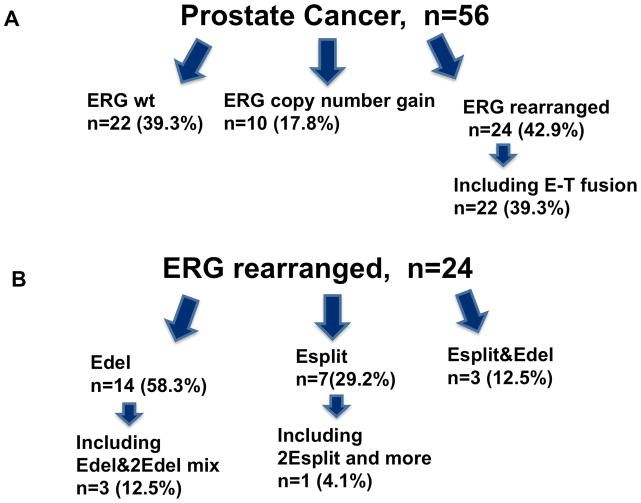

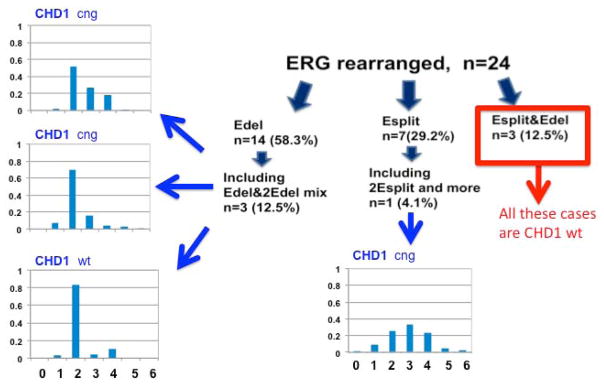

To assess for cell-to-cell clonal variation, multiple adjacent cells (mean of 49 nuclei) were visualized individually within each tumor focus. As shown in Figure 2A, 56 patients with localized prostate cancer were assessed by FISH and confocal microscopy with wild type ERG found in only 22 of 56 patients (39.3%); ERG copy number increased in 10 (17.9%), and ERG rearrangements confirmed in 24 (42.9%), of which 22 resulted in a TMPRSS2-ERG fusion. The remaining two with ERG rearrangement without TMPRSS2-ERG fusion included a case with a split of 3′ and 5′ ERG signals and no evidence of fusion between ERG and TMPRSS2 gene (the distance between green and white signals was more then 2 um), and the other case represents joint deletion of an ERG and TMPRSS2 loci. In the 24 patients with ERG rearrangements (Figure 2B), the mechanisms of rearrangement were variable, with deletion in 14/24 (58.3%), a split event in 7/24 (29.2%), and both deletions and a split event in the same tumor focus in 3/24 (12.5%) patients. More specifically, regarding actual well defined nuclei of the three patients with both deletions and a split event in the same focus (Figure 2B, Esplit&Edel), the first patient had a deletion and a split event in 46.3% and 39% respectively of 41 nuclei analyzed; the second had a deletion and a split event in 58.1% and 35% respectively of 62 nuclei analyzed; and the third patient had a deletion and a split event in 22.6% and in 63.1% respectively of 57 nuclei analyzed. Figure 3C shows a picture of an example of the heterogeneity in patients with both ERG deletions and ERG split events that occurred in adjacent cells of the same tumor foci and resulted in TMPRSS2-ERG fusions.

Figure 2. Results of assessment of ERG rearrangements.

Figure 2A: Distribution of ERG status in 56 patients. ERG wild-type (wt) was found in 22, ERG copy number gain in 10, and ERG rearrangement in 24 patients, with 22 patients demonstrating TMPRSS2-ERG fusion (E-T fusion). Figure 2B: ERG rearrangements occurred in 24 of 56 patients. The most frequent mechanism of rearrangements in micro-foci were deletion in 14/24 (58.3%), a split event and translocation in 7/24 (29%), and a heterogeneous mix of ERG deletions and translocations in 3/24 (12.5%) of patients.

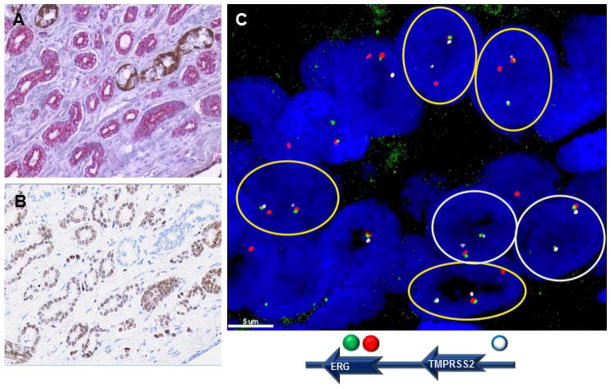

Figure 3. Heterogeneity of ERG rearrangement.

Figure 3A: FFPE sections of prostate cancer stained for AMACR expression (magenta) and expression of p63 (brown), which stains benign basal cells of the prostate. Figure 3B: Expression of ERG (brown), which was associated T-E fusion. Figure 3C: FISH analysis demonstrating intra-tumor heterogeneity with a combination of ERG deletion and ERG split/translocation within the same tumor focus.

Assessment with H&E (Figure 3A) and ERG immunohistochemistry (Figure 3B) demonstrated ERG expression in all 22 analyzed cases with TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion and absence of ERG expression in all 32 cases without rearrangements, including the 10 cases with ERG copy number gain. One case with joint deletion of one ERG and TMPRSS2 locus was also ERG expression negative. The case with a split of ERG and TMPRSS2 loci was ERG positive, probably because of the ERG fusion with another gene partner that might drive the ERG gene expression. Although only a descriptive assessment, mean staining intensity was 1.78, 1.41, and 2.0 (scored 1–3) with a mean of 77.1%, 82.4%, and 89.1% of cells staining in patients with ERG deletion only, ERG split events only, and patients with both deletion and split events in the same foci respectively.

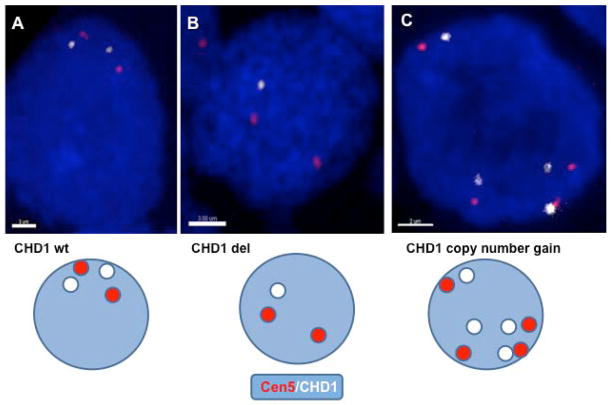

CHD1 deletion is associated with lack of ERG rearrangements in clones within Foci

Given prior studies demonstrating the dependence of ERG rearrangements on CHD1, we assessed CHD1 in patient tumor using FISH and confocal microscopy to precisely assess adjacent nuclei (mean nuclei assessed 74 per tumor core) for CHD1 deletions and copy number changes. As shown in Figure 4, using a DNA probe that corresponds to the peri-centromeric region on human chromosome 5 as a reporter (red), CHD1 deletion (Figure 4B) and copy number changes (Figure 4C) can be accurately identified in adjacent nuclei. As reported in Table 1, ERG rearrangement was significantly associated with normal CHD1 gene status or copy number gain (using Fisher’s exact test, P=0.000188). Specifically, of 45 patients in which both ERG status and CHD1 could be accurately assessed, 14/45 (31.1%) of patients had CHD1 deletion, with the majority of the CHD1 deletions 13/14 (92.9%) correlating with ERG-rearrangement negative status (Table 1).

Figure 4. Assessment of CHD1.

FISH assay that included the specific BAC probe for CHD1 gene (White) and the probe-reporter of the pericentromeric region of human chromosome 5 (Cen5), (Red). CHD1 wild type (Figure 4A), deletion (Figure 4B), and increased copy number (Figure 4C) are shown.

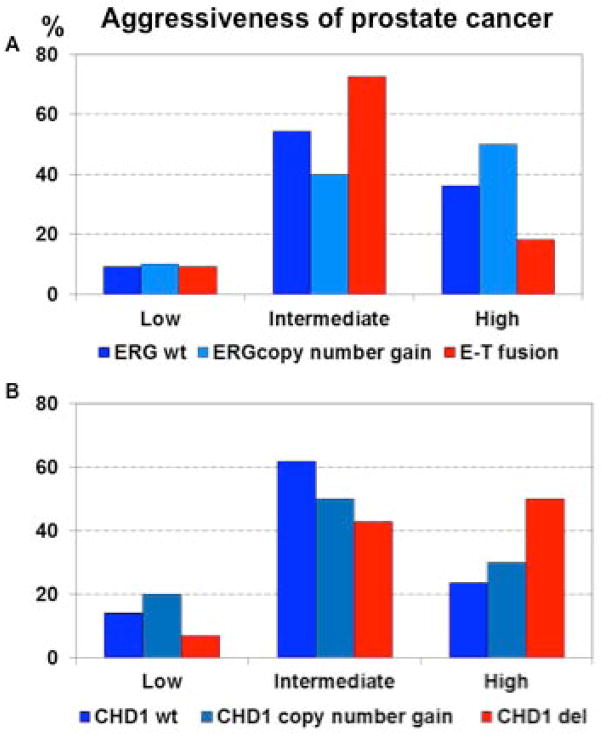

CHD1 and ERG relationship to Tumor Aggressiveness and Stage

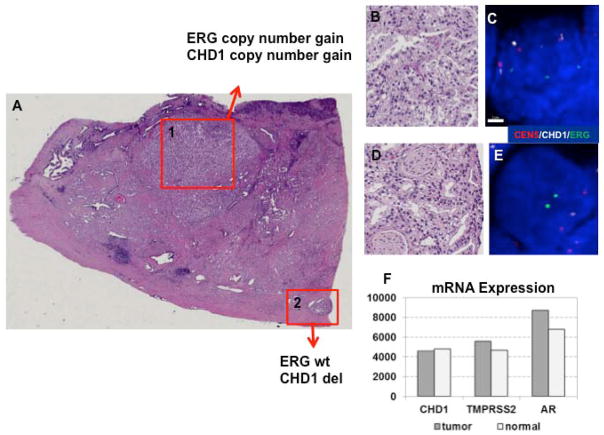

As shown in Table 2, a correlation between ERG copy number gain with T2 vs. T3 stage tumors was noted (p=0.04963). In contrast, ERG copy number gain did not correlate with tumor aggressiveness defined by Gleason Score (p=0.256). CHD1 deletion (Figure 5B, red bars) also had a trend to correlate with more aggressive disease defined by Gleason score that was not statistically significant in this small data set (P=0.115), possibly defining an aggressive subset of tumors without TMPRSS2-ERG fusion. Clearly these data are only hypothesis generating, given the small sample size and the relevance copy number variations will require further studies. Additionally, a descriptive assessment demonstrates even more complexity for efforts to define copy number with heterogeneity of CHD1 copy number within a single foci of some patients. Figure 6 shows copy number variation within tumor foci from patients known to have complex ERG rearrangements (shown in Figure 6 for the subgroup of 24 patients with ERG rearrangement). As shown in Figure 6, copy number changes in CHD1 are noted for patients with heterogeneity of deletion or split events, but not in the three patients with a combination of split events and deletion in the same focus. Figure 7 shows assessment of one patient noted to have an ERG copy number gain and CHD1 copy number gain in one focus (foci 1 of Figure 7A and Figure 7B and C) and wild type ERG with CHD1 deletion in another focus (foci 2 of Figure 7A and Figure 7D and 7E), despite no clear evidence of CHD1 deletion by RNA sequencing, as shown in Figure 7F.

Figure 5. Correlation of ERG and CHD1 status with Tumor aggressiveness.

ERG (Figure 5A) and CHD1 (Figure 5B) rearrangement status is shown relative to tumor Gleason score with low (Gleason Score 6), intermediate (Gleason Score 7), and high aggressiveness (Gleason Score 8–10).

Figure 6. Variation of CHD1 copy number in patients with complex ERG rearrangements.

The subgroup of 24 patients with ERG rearrangement are shown with associated assessment of CHD1 (mean of 74 nuclei assessed per tumor core). Copy number changes in CHD1 are noted for patients with heterogeneity of deletion (three graphs on left demonstrating percentage of nuclei with various copy numbers) or split events (single bar graph demonstrating most nuclei with 3 or more copies of CHD1), but not in the three patients with a combination of split events and deletion in the same focus.

Figure 7. Assessment of ERG, CHD1, and RNA sequencing.

Figure 7A: Region 1 represents a focus of cancer cells with combination ERG gene and CHD1 gene copy number gain, while in region 2 the cells with intact ERG alleles and mono-allelic deletion of CHD1 gene. Figure 7B and C: H&E and FISH of focus 1, demonstrating increased ERG and CHD1 copy number. Figures 7D and E: H&E and FISH of focus 2, demonstrating wild type ERG and CHD1 deletion. Figure 7F: RNA sequencing using microdissection of multiple foci of tumor tissue demonstrating lack of recognition of heterogeneity of foci, with differences in CHD1 in second focus.

Discussion

We found ERG rearrangement heterogeneity in patients with localized prostate cancer assessed by FISH and confocal microscopy, as a complimentary approach to assess local cell-to-cell clonal variation. We found heterogeneity in the mechanism of TMPRSS2-ERG fusions with variability in ERG deletions or translocations. CHD1 deletion, which occurred in approximately 1/3 of patients, correlated with a distinct subset of higher grade tumors without ERG rearrangements.

Using a careful assessment of individual nuclei with FISH and confocal microscopy in patients with localized prostate cancer, we found TMPRSS2-ERG fusion rearrangements occurred in 39%. These data are similar to prior studies that have generally found approximately 40–50% of patients with TMPRSS2-ERG fusions (3). Prior studies using FISH alone (without confocal microscopy to identify each specific nucleus) also found homogeneity of types of ERG rearrangements within a given focus, and only heterogeneity between individual separate tumor foci (8) (10). In fact, Mehra et al. found 10% of 43 patients with both deletions and split events in the same patient, but in separate foci (8). Extending these observations, using confocal microscopy along with FISH to precisely assess cell-to-cell variations in each single foci, we now found marked heterogeneity in copy number, deletions and translocations even within a single focus of tumor. In fact, using confocal microscopy, we identified 29% of patients with ERG rearrangement with heterogeneity with either a variable number of deletions, variable number of split events, or a combination of split events and deletions in a single focus (Figure 2B).

In line with this hypothesis that tumors exhibit significant intra-focal heterogeneity, Minner et al. recently studied ERG expression by immunohistochemistry and found both inter-focal and intra-focal staining heterogeneity, with general overall concordance between ERG positivity and FISH detected TMPRSS2-ERG fusions (11). Mertz et al. also found heterogeneous staining of ERG by immunohistochemistry in biopsy cores in 10 to 15% of patients (12). Our study using FISH and confocal microscopy to carefully assess individual foci (intra-focal heterogeneity) extends the assessments by Minner and Mertz et al. that used immunohistochemistry, providing genetic mechanisms for the heterogeneity present by these prior studies, confirming clonal variability even within a single focus of tumor. Assessment of ERG by IHC was not additionally informative to genetic assessments by FISH and confocal microscopy, as general intensity and percentage of cells staining was similar regardless of the type of ERG rearrangement in this subset. Future correlations within larger numbers of patients may be helpful for future comparison of methodologies. Future assessments will also be important to determine if these clonal differences detected by FISH and confocal microscopy that would be present in a single focus of a single biopsy core meaningfully relate to drug resistance and prognosis (13).

Given prior studies that have demonstrated TMPRSS2-ERG fusion generation in specific clones is dependent on CHD1, a putative TSG that codes for an ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling enzyme, we also assessed CHD1 using FISH and confocal microscopy. Prior studies using FISH analysis with a threshold of 60% loss of CHD1 signal to define deletion and centromere 10 probe as control demonstrated 8.7% of prostate tumors with deletion (6). We demonstrated CHD1 deletion to occur more frequently in 14/45 (31.1%) patients, possibly due to different technical approaches. In contrast to the approach by Burkhardt et al., we used FISH as well as confirmation of actual nuclei with both chromosomes using confocal microscopy and a chromosome 5 centromere probe (CHD1 is located on 5q21) vs. Burkhardt who used a chromosome 10 control. Given the importance of CHD1 and frequent finding of deletions in this small cohort, our data along with those by Burkhardt et al. warrants assessment in larger studies in which long term outcome is measured. Our data also demonstrated that CHD1 deletion correlated with both a lack of ERG rearrangement and a non-significant trend with Gleason score, along with heterogeneity in copy number changes within foci. Although these data are only hypothesis generating given small numbers, these data are in agreement with prior studies that have also demonstrated that CHD1 regulates genomic stability and its deletion is associated with high Gleason score and absence of ERG fusion (3) (6) (7). Liu et al. also demonstrated that CHD1 is a tumor suppressor gene and knockdown has resulted in increased invasiveness (14). Baca et al. identified translocations and deletions to occur in an interdependent manner, or chromoplexy, coupled to transcriptional processes in tumors with ETS fusions; in contrast, tumors with CHD1 deletion were associated with tumors without ETS fusions and a distinctive patterns of genomic instability, or chromothripsis (7). Given the association of CHD1 and ERG status, as well as implications to tumor behavior in our study and these prior studies, larger prospective studies with CHD1 assessment are warranted to under stand its role and mechanism as a predictive bio-marker.

Conclusions

Taken together, the identification of these important genomic changes such as TMPRSS2-ERG fusion and CHD1 deletion and the question of tumor heterogeneity supports a thorough analysis of these potentially treatment stratifying biomarkers in even single tumor foci with few cancer cells in a biopsy core, in addition to efforts to attempts at multiple biopsies. These results also support the notion that TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusions may arise independently within the same tumor focus and that additional heterogeneity may be present even in a focus of a single biopsy core. Moreover, complex pattern of ERG and CHD1 genes represents regional intra-tumor heterogeneity. These data support the study of complimentary approaches with NGS especially in tumors such as prostate cancer in which there is often limited tissue available. These data also require further study to understand heterogeneity of genetic changes, especially because clinical studies have already been launched, or are being designed, using genetic changes such as in a single core biopsy to direct a specific therapy.

References

- 1.Burrell RA, McGranahan N, Bartek J, Swanton C. The causes and consequences of genetic heterogeneity in cancer evolution. Nature. 2013;501(7467):338–45. doi: 10.1038/nature12625.. Epub 2013/09/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366(10):883–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205.. Epub 2012/03/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beltran H, Yelensky R, Frampton GM, Park K, Downing SR, MacDonald TY, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of advanced prostate cancer identifies potential therapeutic targets and disease heterogeneity. European urology. 2013;63(5):920–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.08.053. Epub 2012/09/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grasso CS, Wu YM, Robinson DR, Cao X, Dhanasekaran SM, Khan AP, et al. The mutational landscape of lethal castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7406):239–43. doi: 10.1038/nature11125. Epub 2012/06/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner JC, Ateeq B, Li Y, Yocum AK, Cao Q, Asangani IA, et al. Mechanistic rationale for inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in ETS gene fusion-positive prostate cancer. Cancer cell. 2011;19(5):664–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.04.010. Epub 2011/05/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burkhardt L, Fuchs S, Krohn A, Masser S, Mader M, Kluth M, et al. CHD1 is a 5q21 tumor suppressor required for ERG rearrangement in prostate cancer. Cancer research. 2013;73(9):2795–805. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1342.. Epub 2013/03/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baca SC, Prandi D, Lawrence MS, Mosquera JM, Romanel A, Drier Y, et al. Punctuated evolution of prostate cancer genomes. Cell. 2013;153(3):666–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.021. Epub 2013/04/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehra R, Tomlins SA, Shen R, Nadeem O, Wang L, Wei JT, et al. Comprehensive assessment of TMPRSS2 and ETS family gene aberrations in clinically localized prostate cancer. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2007;20(5):538–44. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800769.. Epub 2007/03/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark J, Attard G, Jhavar S, Flohr P, Reid A, De-Bono J, et al. Complex patterns of ETS gene alteration arise during cancer development in the human prostate. Oncogene. 2008;27(14):1993–2003. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210843.. Epub 2007/10/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshimoto M, Ding K, Sweet JM, Ludkovski O, Trottier G, Song KS, et al. PTEN losses exhibit heterogeneity in multifocal prostatic adenocarcinoma and are associated with higher Gleason grade. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2013;26(3):435–47. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.162.. Epub 2012/09/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minner S, Gartner M, Freudenthaler F, Bauer M, Kluth M, Salomon G, et al. Marked heterogeneity of ERG expression in large primary prostate cancers. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2013;26(1):106–16. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.130.. Epub 2012/08/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mertz KD, Horcic M, Hailemariam S, D’Antonio A, Dirnhofer S, Hartmann A, et al. Heterogeneity of ERG expression in core needle biopsies of patients with early prostate cancer. Human pathology. 2013;44(12):2727–35. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.07.019.. Epub 2013/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perner S, Demichelis F, Beroukhim R, Schmidt FH, Mosquera JM, Setlur S, et al. TMPRSS2:ERG fusion-associated deletions provide insight into the heterogeneity of prostate cancer. Cancer research. 2006;66(17):8337–41. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1482.. Epub 2006/09/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu W, Lindberg J, Sui G, Luo J, Egevad L, Li T, et al. Identification of novel CHD1-associated collaborative alterations of genomic structure and functional assessment of CHD1 in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31(35):3939–48. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.554. Epub 2011/12/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]