Abstract

Importance

Epidemiologic data on dementia with Lewy bodies (LBD) and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) remain limited in the US and worldwide. These data are essential to guide research and clinical or public health interventions.

Objective

To investigate the incidence of DLB among residents of Olmsted County, MN, and compare it to the incidence of PDD.

Design

The medical records-linkage system of the Rochester Epidemiology Project was used to identify all persons who developed parkinsonism and, in particular, DLB or PDD from 1991 through 2005 (15 years). A movement disorders specialist reviewed the complete medical records of each suspected patient to confirm the diagnosis.

Setting

Olmsted County, MN, from 1991 through 2005 (15 years).

Main Outcome Measure

Incidence of DLB and PDD.

Participants

All the residents of Olmsted County, MN who gave authorization for medical record research.

Results

Among 542 incident cases of parkinsonism, 64 had DLB and 46 had PDD. The incidence rate of DLB was 3.5 per 100,000 person-years overall, and it increased steeply with age. Similarly, the incidence of PDD was 2.5 overall and also increased steeply with age. The incidence rate of DLB and PDD combined was 5.9. Patients with DLB were younger at onset of symptoms than patients with PDD and had more hallucinations and cognitive fluctuations. Men had a higher incidence of DLB than women across the age spectrum. The pathology was consistent with the clinical diagnosis in 24 of 31 patients who underwent autopsy (77.4%).

Conclusions

The overall incidence rate of DLB is lower than the rate for Parkinson’s disease. DLB risk increases steeply with age and is markedly higher in men. This men-to-women difference may suggest different etiologic mechanisms.

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by parkinsonism and cognitive impairment but may also manifest with dysautonomia, sleep disorders, hallucinations, and cognitive fluctuations. Although first described several decades ago,1,2 DLB is still considered a diagnostic challenge because of the clinical and pathological overlap with other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and frontotemporal lobar degeneration.

The temporal sequence distinguishes DLB from another related condition, Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD). The term DLB is used when dementia develops before, or within one year after, parkinsonism onset. The term PDD is used when dementia appears more than one year after the onset of otherwise typical Parkinson’s disease. However, PDD and DLB may be manifestations of the same neurodegenerative disorder, possibly related to the abnormal accumulation of a-synuclein.3,4

Limited information is available about the incidence of DLB or PDD in the general population and their distribution by age and sex.5,6 To better characterize these two disorders, we investigated the incidence of DLB and PDD in a well-defined population over a 15-year period. In addition, we compared the clinical characteristics in patients with DLB versus PDD. For some of the subjects, we were able to validate our clinical diagnosis as compared with autopsy results.

METHODS

CASE ASCERTAINMENT

We studied the geographically-defined population of Olmsted County, Minnesota (MN) from January 1, 1991 through December 31, 2005 (15 years). Extensive details about the Olmsted County population were reported elsewhere.7–10 In brief, the total population of Olmsted County was 110,780 in 1991 and grew to 138,098 in 2005. The population of age 65 years and older was 10,603 in 1991 and grew to 14,911 in 2005. The percent of women was 52.3% in 1991 and 52.4% in 2005.

We ascertained cases of parkinsonism through the medical records-linkage system of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP). This system provides the infrastructure for indexing and linking essentially all medical information of the county population.7–10 All medical diagnoses, surgical interventions, and other procedures are entered into computerized indexes using the Hospital Adaptation of the International Classification of Diseases – Eighth Revision (H-ICDA)11 or the International Classification of Diseases – Ninth Revision (ICD-9).12

We ascertained cases of parkinsonism using a computerized screening phase and a clinical confirmation phase, as described in detail elsewhere.13 In phase 1, we searched the electronic indexes of the records-linkage system for 38 diagnostic codes related to parkinsonism. This set of codes was previously validated.13,14 In phase 2, a movement disorders specialist (R.S.) defined the type of parkinsonism using specified diagnostic criteria and determined the approximate date of onset of parkinsonism. Onset of parkinsonism was defined as the approximate date in which one of the four cardinal signs of parkinsonism was first noted by the patient, by a family member, or by a care provider (as documented in the medical record). To be included in our study, patients were required to reside in Olmsted County at the time of onset of symptoms, and we excluded subjects who denied authorization to use their medical records for research.7,13

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

Our diagnostic criteria included two steps: the definition of parkinsonism as a syndrome and the definition of the different types of parkinsonism within the syndrome. Parkinsonism was defined as the presence of at least two of four cardinal signs: rest tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and impaired postural reflexes.13,14 Among subjects with parkinsonism, we defined DLB according to the criteria of the 2005 Consensus Conference as presence of parkinsonism and dementia; dementia was defined as a progressive cognitive decline.15 As stated in the consensus criteria, DLB may be diagnosed when dementia occurs within the first year of the onset of parkinsonism. By contrast, PDD was diagnosed in those patients initially meeting the diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease, who developed dementia more than one year after parkinsonism onset.14,15 In addition, we abstracted from medical records information on clinical manifestations such as the presence of hallucinations, cognitive fluctuations, myoclonus, and response to L-Dopa therapy.

RELIABILTY AND VALIDITY OF DIAGNOSIS

To study the reliability of our case-finding procedure, the records of 40 subjects reviewed by the primary movement disorders specialist (R.S.) were independently reviewed by a second specialist (B.F.B) who was kept unaware of the initial diagnosis. The 40 subjects were selected randomly among those classified by the primary neurologist as DLB (10 persons), as PDD (10 persons), as other types of parkinsonism (10 persons), and parkinsonism excluded after screening positive (10 persons). Agreement on presence of parkinsonism of any kind (including DLB and PDD) was 96.7% (29 out of 30). The one disagreement involved a person classified as DLB by the first specialist but excluded by the second specialist. Agreement on exclusion of parkinsonism of any kind in subjects who screened positive was 80.0% (8 out of 10). Of the 29 subjects classified as parkinsonism by both neurologists, the agreement for DLB or PDD versus other types of parkinsonism was 93.1% (27 out of 29). Overall, 17 of the 20 subjects classified as DLB or PDD by the first neurologist were also classified as DLB or PDD by the second neurologist (85.0% agreement). Finally, for the 17 patients found to be affected by DLB or PDD by both neurologists, the agreement on the year of oonset of symptoms was within 1 year in 14 subjects (82.4%) and within 5 years for the remaining 3 subjects (intra-class correlation coefficient = 0.82; 95% CI 0.69–0.92). To validate the clinical diagnosis, we reviewed the autopsy reports for all the patients who died during the study and for whom an autopsy was available. Detailed results of the validation study are reported in the Results section.

DATA ANALYSIS

All individuals who met criteria for DLB or PDD, with symptom-onset between January 1, 1991 and December 31, 2005, and who were residents of Olmsted County at the time of onset of symptoms were included as incident cases. We calculated incidence rates using incident cases as the numerator and population counts from the REP Census as denominators.7 The denominators were corrected by removing prevalent cases of parkinsonism imputed using prevalence figures from several European populations.16 Details about the denominator correction were published elsewhere.14

We computed age- and sex-specific incidence rates of DLB, PDD, and DLB and PDD combined. Because our study was descriptive and involved the entire Olmsted County population, no sampling procedures were involved and confidence intervals and statistical tests were not necessary for the interpretation of incidence rates.17 By contrast, when comparing the clinical characteristics of patients with DLB and PDD and of men and women, we used statistical testing (chi-square tests or Wilcoxon’s rank sum tests). All analyses were completed using SAS v. 9.2 (SAS, Cary, NC) and tests of significance were performed at the conventional two-tailed alpha level of 0.05.

RESULTS

INCIDENCE OF DLB AND PDD

We identified 5,505 individuals with at least one screening diagnostic code related to parkinsonism during the study years. First, we excluded 400 individuals because they were not residents of Olmsted County at the time of onset of symptoms and 136 subjects because they did not give permission to use their medical records for research. Of the 4,969 remaining subjects, 3,877 were found to be not affected by parkinsonism; 12 subjects lacked sufficient clinical documentation to determine their parkinsonism status; 374 subjects had onset of parkinsonism before January 1, 1991, and 164 subjects had onset after December 31, 2005. In summary, we identified 542 incident cases of parkinsonism with onset between January 1, 1991 and December 31, 2005, of whom 64 cases had DLB and 46 cases had PDD.13

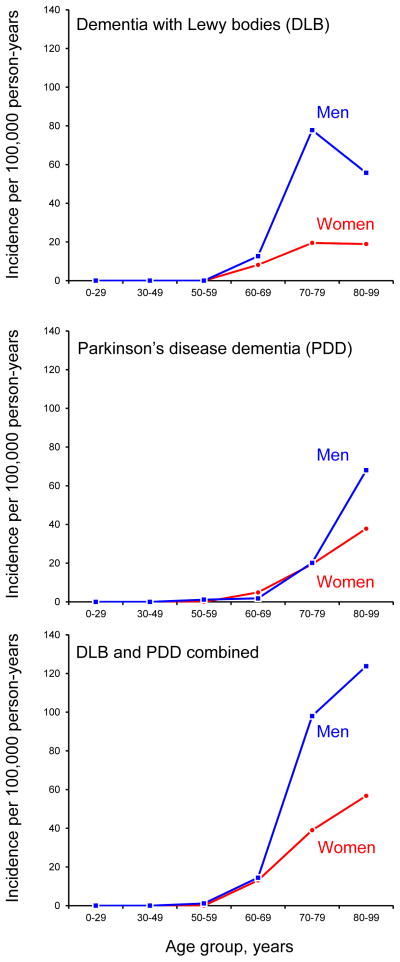

Table 1 shows the age- and sex-specific incidence rates (new cases per 100,000 person-years) of DLB, PDD, and DLB and PDD combined. The incidence of DLB was 3.5 per 100,000 person-years overall and was higher in men than in women (4.8 vs. 2.2). The incidence of DLB increased with age ranging from 10.3 in persons age 60–69 years, peaking at 44.5 in persons age 70–79 years, and remaining high at 30.1 in persons age 80–99 years. The incidence rate in men was markedly higher than in women after age 60 years (Figure 1, upper panel).

TABLE 1.

Age- and sex-specific incidence rates of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia (per 100,000 person-years) in Olmsted County, MN from 1991 to 2005a

| Type of Parkinsonism | Age group, yearsb

|

All ages (0–99)c

|

All ages (65+)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50–59

|

60–69

|

70–79

|

80–99

|

|||||||||

| n | Rate | n | Rate | n | Rate | n | Rate | n | Rate | n | Rate | |

| Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) | 0 | 0.0 | 12 | 10.3 | 36 | 44.5 | 16 | 30.1 | 64 | 3.5 | 59 | 31.6 |

| Men | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 12.7 | 27 | 77.8 | 9 | 55.7 | 43 | 4.8 | 41 | 54.2 |

| Women | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 8.2 | 9 | 19.5 | 7 | 18.9 | 21 | 2.2 | 18 | 16.2 |

| Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) | 1 | 0.6 | 4 | 3.4 | 16 | 19.8 | 25 | 47.0 | 46 | 2.5 | 43 | 23.0 |

| Men | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.8 | 7 | 20.2 | 11 | 68.1 | 20 | 2.3 | 18 | 23.8 |

| Women | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 4.9 | 9 | 19.5 | 14 | 37.9 | 26 | 2.7 | 25 | 22.5 |

| DLB and PDD combined | 1 | 0.6 | 16 | 13.7 | 52 | 64.3 | 41 | 77.2 | 110 | 5.9 | 102 | 54.6 |

| Men | 1 | 1.2 | 8 | 14.5 | 34 | 98.0 | 20 | 123.8 | 63 | 7.1 | 59 | 78.0 |

| Women | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 13.1 | 18 | 39.0 | 21 | 56.8 | 47 | 4.9 | 43 | 38.7 |

Numbers to the left of the rates indicate the actual number of cases. Incidence rates can be computed by dividing the number of cases by the corresponding denominator and multiplying by 100,000. Denominators in person-years for men and women combined were as follows: 0–29 = 843,999; 30–49 = 577,614; 50–59 = 180,689; 60–69 = 116,489; 70–79 = 80,829; 80–99 = 53,142; all ages = 1,852,762; 65+ = 186,663. Denominators for men were as follows: 0–29 = 418,326; 30–49 = 277,387; 50–59 = 86,452; 60–69 = 55,288; 70–79 = 34,695; 80–99 = 16,155; all ages = 888,303; 65+ = 75,652. Denominators for women were as follows: 0–29 = 425,673; 30–49 = 300,227; 50–59 = 94,237; 60–69 = 61,201; 70–79 = 46,134; 80–99 = 36,987; all ages = 964,459; 65+ = 111,011.

We did not observe any incident case of DLB or of PDD with onset before age 50. Therefore, all the numerators for rates in the 0–29 and 30–49 years groups were zero (data not shown).

Overall incidence rate for all ages (0–99 years), including the age groups 0–29 and 30–49 years.

Figure 1.

Age- and sex-specific incidence rates per 100,000 person-years for dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB; upper panel), Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD; middle panel), and both diseases combined (DLB and PDD; lower panel).

The incidence of PDD was 2.5 per 100,000 person-years overall and was similar in men and women (2.3 vs. 2.7). The overall incidence of PDD increased consistently with age ranging from 0.6 in persons age 50–59 years to 47.0 in persons age 80–99 years. Even though the overall incidence was similar in men and women, the incidence was markedly higher in men than in women in the oldest age group (68.1 in men vs. 37.9 in women at age 80–99 years; Figure 1, middle panel).

The combined incidence of DLB and PDD was 5.9 overall and was higher in men than in women (7.1 vs. 4.9). The incidence rate increased exponentially with increasing age overall and in men and women separately. Men had consistently higher incidence rates than women across the age spectrum (Figure 1, lower panel).

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF DLB AND PDD

Table 2 summarizes the clinical characteristics of patients diagnosed with DLB and PDD overall and for men and women separately. There were no statistically significant differences between men and women affected by DLB or by PDD for any of the clinical characteristics investigated. By contrast, patients with DLB were younger at onset of symptoms than patients with PDD (median 76.3 vs. 81.4 years) and had a higher frequency of hallucinations (62.5% vs. 20.0%) and cognitive fluctuations (25.0% vs. 8.9%). Although not reaching statistical significance, patients with DLB also had higher frequency of myoclonus (12.5% vs. 4.4%) and were treated less frequently with L-Dopa than patients with PDD (60.9% vs. 76.1%).

TABLE 2.

Clinical characteristics of incident cases of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia in Olmsted County, MN from 1991 to 2005

| Clinical characteristics | Men and women

|

DLB vs. PDD | Men

|

Women

|

Men vs. women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | p-valuea | n | % | n | % | p-valuea | |

| Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) | ||||||||

| Age of onset, years, median (IQR) | 76.3 | (71.4, 80.2) | 0.002 | 75.2 | (71.2, 79.6) | 78.1 | (70.8, 81.9) | 0.52 |

| Follow-up, years, median (IQR)b | 5.3 | (3.7, 7.9) | 0.03 | 5.2 | (3.7, 7.9) | 5.4 | (4.4, 8.0) | 0.88 |

| Education, years, median (IQR) | 13 | (12, 16) | 0.23 | 14 | (12, 17) | 12 | (12, 14) | 0.17 |

| L-Dopa ever treated | 39 | 60.9 | 0.09 | 27 | 62.8 | 12 | 57.1 | 0.66 |

| L-Dopa responsive (% of treated) | 23 | 59.0 | 0.55 | 16 | 59.3 | 7 | 58.3 | 0.96 |

| Hallucinations | 40 | 62.5 | <0.0001 | 25 | 58.1 | 15 | 71.4 | 0.30 |

| Cognitive fluctuations | 16 | 25.0 | 0.03 | 10 | 23.3 | 6 | 28.6 | 0.64 |

| Myoclonus | 8 | 12.5 | 0.15 | 7 | 16.3 | 1 | 4.8 | 0.19 |

| Total | 64 | 100.0 | -- | 43 | 100.0 | 21 | 100.0 | -- |

| Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) | ||||||||

| Age of onset, years, median (IQR) | 81.4 | (76.4, 87.4) | -- | 81.2 | (76.2, 86.3) | 81.9 | (76.9, 87.7) | 0.60 |

| Follow-up, years, median (IQR)b | 4.2 | (1.8, 6.4) | -- | 4.8 | (2.2, 6.6) | 3.9 | (1.3, 6.8) | 0.36 |

| Education, years, median (IQR) | 12 | (12, 16) | -- | 12 | (12, 16) | 12 | (9, 15) | 0.17 |

| L-Dopa ever treated | 35 | 76.1 | -- | 14 | 70.0 | 21 | 80.8 | 0.40 |

| L-Dopa responsive (% of treated) | 23 | 65.7 | -- | 8 | 57.1 | 15 | 71.4 | 0.38 |

| Hallucinationsc | 9 | 20.0 | -- | 4 | 21.1 | 5 | 19.2 | 0.88 |

| Cognitive fluctuationsc | 4 | 8.9 | -- | 1 | 5.3 | 3 | 11.5 | 0.47 |

| Myoclonusc | 2 | 4.4 | -- | 1 | 5.3 | 1 | 3.8 | 0.82 |

| Total | 46 | 100.0 | -- | 20 | 100.0 | 26 | 100.0 | -- |

Abbreviations: DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; IQR, interquartile range (25th percentile, 75th percentile); PDD, Parkinson’s disease dementia.

Frequencies were compared using chi-square tests and medians using Wilcoxon rank sum tests.

Follow-up refers to the number of years the patient was captured in the records-linkage system between diagnosis and death, last contact with the system, or end of study (time of medical record abstraction).

Of the 46 persons with PDD, only 45 had information available regarding hallucinations, cognitive fluctuations, and myoclonus

NEUROPATHOLOGICAL VALIDATION OF CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS

Among the 542 incident cases of parkinsonism of any type, 343 (63.3%) had died at the time of the study and 65 had a brain autopsy (19.0% of deceased patients). Among these 65 patients, 31 were classified using our clinical criteria as DLB or PDD, and 24 of them had Lewy body pathology (77.4% agreement). The agreement of the clinical diagnosis with pathology was 94.1% for DLB (16 patients out of 17); the single discrepant case had Alzheimer’s disease pathology without Lewy bodies or tau inclusions. However, the agreement was only 57.1% for PDD (8 patients out of 14). All of the discrepant cases without Lewy bodies had mild to moderate brain atrophy, 4 had mild depigmentation of substantia nigra, 3 had Alzheimer’s disease pathology, and 1 had tau inclusions.

COMMENT

There is a paucity of published incidence data relating to DLB despite the fact that DLB is presumed to be the second leading cause of neurodegenerative dementia after Alzheimer’s disease. The overall incidence rate of DLB in our population-based study was 3.5 cases per 100,000 person-years. To put this into context, Parkinson’s disease incidence was four-fold higher with an incidence rate of 14.2 cases per 100,000 person-years.13 In fact, the overall incidence of Parkinson’s disease in our county was 2.4 times higher than the incidence of DLB and PDD combined (14.2 versus 5.9).13 The lower incidence of DLB than Parkinson’s disease in our study may reflect ascertainment bias. First, some patients may not have had sufficiently distinctive features to allow the diagnosis of DLB and they remained diagnosed as dementia. Second, our criteria required the presence of parkinsonism to qualify as DLB, and we may have missed those patients with Lewy body pathology in whom parkinsonism remained minimal. Unfortunately, the percent of subjects found to have Lewy body pathology at autopsy despite having minimal or unrecognized symptoms of parkinsonism varied in the literature, but may be sizeable.18–20 Therefore, our DLB incidence rates should be regarded as minimum estimates. On the other hand, our access to longitudinal medical records covering the entire duration of medical care should have allowed parkinsonism to surface in all but a small subset of patients with dementia.

There was a striking predominance of DLB incidence in men across all ages, as illustrated in Figure 1. During the peak incidence decade (ages 70–79), there was approximately a four-fold incidence rate difference between men and women (77.8 versus 19.5). This exceeds the men to women differences observed for Parkinson’s disease incidence rate in the same age group (181.6 versus 69.4).13 These sex differences may provide important etiologic clues for Parkinson’s disease and for DLB. The different risk in men and women suggests several lines of further research focusing on genetic (chromosomes X and Y),21 endocrinological,22,23 environmental,24 or social and cultural factors (gender related factors).25,26

The incidence of PDD was substantially lower than that of DLB (overall incidence rate of 2.5 versus 3.5 cases per 100,000 person-years). However, our PDD incidence findings likely underestimated the true occurrence of this condition. A defining feature of PDD is the development of dementia among patients previously diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. In clinical practice, mild dementia may be overshadowed by Parkinson’s disease problems requiring medication adjustments such as fluctuating motor symptoms, dyskinesias, sleep problems, or dysautonomia. Therefore, only patients with moderate or severe dementia were likely identified.

We included PDD in this study because of the overlap with DLB, both clinically and pathologically. The distinction between DLB and PDD is somewhat arbitrary, although necessary for clinical research, and is based on the time-lag between onset of motor symptoms and onset of dementia. DLB and PDD share the same neuropathology, and it is often impossible to differentiate DLB from PDD at autopsy.4 However, there is a frequent coexistence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology with DLB,27,28 which tends to be modest in typical PDD.29 Among the patients who underwent autopsy, we had robust neuropathological confirmation of the clinical diagnosis of DLB (94.1%); however, this was not the case for PDD (57.1%). Among the 14 autopsied PDD cases, six did not have Lewy bodies. This contrasts with the Parkinson’s disease cases from our autopsy series where there was confirmation of Lewy bodies in 85.0% of the brains.13

One prior population-based study of DLB incidence was conducted in southwestern France (the PAQUID Study).5 The investigators reported an overall DLB incidence rate of 112.3 cases per 100,000 person-years in subjects age 65 and older. This estimate was based on a total of 29 incident cases of DLB identified using a two-phase survey involving screening questions and collection of data from general practitioners and specialists.5 The incidence of DLB in persons age 65 years and older was lower in our study at 31.6 per 100,000 person-years. However, in both studies, the risk increased steeply with age and was higher in men.

Our study has a number of strengths. First, taking advantage of the medical records-linkage system of the REP, we studied a well-defined population over 15 years.7–10 Although our population was relatively small for rare conditions such as DLB and PDD (14,911 subjects older than age 65 years in 2005), we accumulated 1,852,762 person-years of observation. Because we covered the Olmsted County population entirely, we elected not to use confidence intervals for the incidence rates.17 However, confidence intervals can be computed from the data provided in Table 1.

Second, virtually all medical providers in Olmsted County, MN are included in the REP;7–10 and it is unlikely that a patient would have had neurological care exclusively outside of the county while living in the county. Third, our study included 542 cases of parkinsonism, which allowed us to explore less common types of parkinsonism such as DLB and PDD. Fourth, 63.3% of cases were followed from the onset of the disease to the time of death, and 94.3% were followed through death or for at least five years after onset. Fifth, all of the cases were adjudicated by a movement disorders specialist at the time of records abstraction to reduce differences in the diagnostic criteria over time or across the different care providers. In addition, we compared the initial diagnosis with the diagnosis given independently by another specialist (B.F.B.) in a subsample of subjects and found good agreement. Finally, the agreement of clinical diagnosis with autopsy findings was good, particularly for DLB, suggesting that our clinical classification of patients was valid.

Our study also has a number of limitations. First, it is possible that some patients with mild symptoms went unrecognized and, hence, undiagnosed. However, our data collection spanned across 20 years, and we collected data for an additional five years after the study period (2006 - 2010). This allowed us to appropriately retro date the time of onset of symptoms when needed.13 Second, some of the clinical features (e.g., cognitive fluctuations) were not systematically recorded in the medical records and, thus, certain clinical features may have gone unrecognized. Third, because cognitive status was not systematically studied in all patients with parkinsonism, some patients with cognitive complaints may have been overlooked. Indeed, in clinical practice, if patients have already been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, they may not receive an additional diagnosis of dementia. On the other hand, when dementia is the first symptom or the major manifestation, such as in DLB, cognitive symptoms are specifically evaluated and diagnosed; however, an additional diagnosis of parkinsonism may not be given especially in older subjects with severe non-neurological comorbidities (Figure 1, upper panel). Finally, Olmsted County is a primarily white community of persons with European descent, and our findings may not be generalizable to other populations with different ethnic, social, and economic characteristics; however, the population is similar to a large portion of the U.S. population.8

In conclusion, our study provides unique population-based data on the incidence of DLB and PDD in Olmsted County, MN. Similar to Parkinson’s disease, the risk of DLB increases with older age and is more frequent in men. Interestingly, the men predominance for DLB risk was greater than for Parkinson’s disease. The men-to-women difference in risk of DLB may suggest different etiologic mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AG034676 and by the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

Role of the Sponsors: The funding organizations had no involvement in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and in the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Data access and Responsibility: Dr. Rocca, who is independent of any commercial funder or sponsor, declares that he had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Additional contributions: We thank Ms. Lori Reinstrom and Carol Greenlee, BA for their assistance with typing and formatting the manuscript.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Savica, Rocca, Grossardt. Acquisition of data: Savica, Bower, Ahlskog, Boeve. Analysis and interpretation of data: Savica, Grossardt, and Rocca. Drafting of the manuscript: Savica and Rocca. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Savica, Grossardt, Bower, Boeve, Ahlskog, and Rocca. Statistical analysis: Grossardt. Obtained funding: Savica and Rocca. Administrative, technical, and material support: Savica and Rocca. Study supervision: Savica.

References

- 1.Kosaka K, Yoshimura M, Ikeda K, Budka H. Diffuse type of Lewy body disease: progressive dementia with abundant cortical Lewy bodies and senile changes of varying degree--a new disease? Clin Neuropathol. 1984 Sep-Oct;3(5):185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okazaki H, Lipkin LE, Aronson SM. Diffuse intracytoplasmic ganglionic inclusions (Lewy type) associated with progressive dementia and quadriparesis in flexion. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1961 Apr;20:237–244. doi: 10.1097/00005072-196104000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovari E, Horvath J, Bouras C. Neuropathology of Lewy body disorders. Brain Res Bull. 2009 Oct 28;80(4–5):203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKeith I, Mintzer J, Aarsland D, et al. Dementia with Lewy bodies. Lancet Neurol. 2004 Jan;3(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez F, Helmer C, Dartigues JF, Auriacombe S, Tison F. A 15-year population-based cohort study of the incidence of Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies in an elderly French cohort. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010 Jul;81(7):742–746. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.189142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miech RA, Breitner JC, Zandi PP, Khachaturian AS, Anthony JC, Mayer L. Incidence of AD may decline in the early 90s for men, later for women: The Cache County study. Neurology. 2002 Jan 22;58(2):209–218. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011 May 1;173(9):1059–1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Generalizability of Epidemiologic Findings and Public Health Decisions: An Illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(2):151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rocca WA. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a United State population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1202–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, et al. Data Resource Profile: The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system. Int J Epidemiol. 2012 Nov 18;41:1614–1624. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Commission on Professional and Hospital Activities, National Center for Health Statistics. H-ICDA, hospital adaptation of ICDA. 2. Ann Arbor, MI: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Manual of the international classification of diseases, injuries, and causes of death, based on the recommendations of the ninth revision conference, 1975, and adopted by the twenty-ninth World Health Assemby; Geneva. 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savica R, Grossardt BR, Bower JH, Ahlskog JE, Rocca WA. Incidence and pathology of synucleinopathies and tauopathies related to parkinsonism. JAMA Neurol. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.114. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bower JH, Maraganore DM, McDonnell SK, Rocca WA. Incidence and distribution of parkinsonism in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976–1990. Neurology. 1999 Apr 12;52(6):1214–1220. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.6.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005 Dec 27;65(12):1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Rijk MC, Tzourio C, Breteler MM, et al. Prevalence of parkinsonism and Parkinson’s disease in Europe: the EUROPARKINSON Collaborative Study. European Community Concerted Action on the Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997 Jan;62(1):10–15. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson DW, Mantel N. On epidemiologic surveys. Am J Epidemiol. 1983 Nov;118(5):613–619. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mega MS, Masterman DL, Benson DF, et al. Dementia with Lewy bodies: reliability and validity of clinical and pathologic criteria. Neurology. 1996 Dec;47(6):1403–1409. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.6.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickson DW, Braak H, Duda JE, et al. Neuropathological assessment of Parkinson’s disease: refining the diagnostic criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2009 Dec;8(12):1150–1157. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gnanalingham KK, Byrne EJ, Thornton A, Sambrook MA, Bannister P. Motor and cognitive function in Lewy body dementia: comparison with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997 Mar;62(3):243–252. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.3.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saunders-Pullman R, Stanley K, San Luciano M, et al. Gender differences in the risk of familial parkinsonism: beyond LRRK2? Neurosci Lett. 2011 Jun 1;496(2):125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.03.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung SJ, Armasu SM, Biernacka JM, et al. Variants in estrogen-related genes and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011 Jun;26(7):1234–1242. doi: 10.1002/mds.23604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rocca WA, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, et al. Increased risk of parkinsonism in women who underwent oophorectomy before menopause. Neurology. 2008 Jan 15;70(3):200–209. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000280573.30975.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frigerio R, Sanft KR, Grossardt BR, et al. Chemical exposures and Parkinson’s disease: A population-based case-control study. Movement Disorders. 2006;21(10):1688–1692. doi: 10.1002/mds.21009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frigerio R, Elbaz A, Sanft KR, et al. Education and occupations preceding Parkinson disease: a population-based case-control study. Neurology. 2005 Nov 22;65(10):1575–1583. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000184520.21744.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Savica R, Grossardt BR, Bower JH, Ahlskog JE, Rocca WA. Risk factors for Parkinson’s disease may differ in men and women: an exploratory study. Horm Behav. 2013 Jun 8;63(2):308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.05.013. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lippa CF, McKeith I. Dementia with Lewy bodies: improving diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 2003 May 27;60(10):1571–1572. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000066054.20031.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merdes AR, Hansen LA, Jeste DV, et al. Influence of Alzheimer pathology on clinical diagnostic accuracy in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2003 May 27;60(10):1586–1590. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000065889.42856.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apaydin H, Ahlskog JE, Parisi JE, Boeve BF, Dickson DW. Parkinson disease neuropathology: later-developing dementia and loss of the levodopa response. Archives of neurology. 2002 Jan;59(1):102–112. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]