Abstract

Lactoperoxidase is a member of the family of the mammalian heme peroxidases which have a broad spectrum of activity. Their best known effect is their antimicrobial activity that arouses much interest in in vivo and in vitro applications. In this context, the proper use of lactoperoxidase needs a good understanding of its mode of action, of the factors that favor or limit its activity, and of the features and properties of the active molecules. The first part of this review describes briefly the classification of mammalian peroxidases and their role in the human immune system and in host cell damage. The second part summarizes present knowledge on the mode of action of lactoperoxidase, with special focus on the characteristics to be taken into account for in vitro or in vivo antimicrobial use. The last part looks upon the characteristics of the active molecule produced by lactoperoxidase in the presence of thiocyanate and/or iodide with implication(s) on its antimicrobial activity.

1. Introduction

Mammalian peroxidases are distinct from plant peroxidases in size, amino acid homologies, nature of the prosthetic group, and binding of the prosthetic group to the protein. Plant peroxidases consist of approximately 300 amino acids with a noncovalently bound heme moiety, while mammalian peroxidases have 576 to 738 amino acids with a covalently bound heme moiety [1]. Animals' peroxidases display high sequence homology compared to plant peroxidases [2, 3]. Mammalian peroxidases can detoxify peroxide, protect against pathogens, and induce the production of thyroid hormones, while plant peroxidases trigger defense reactions against pathogens and stress, remove hydrogen peroxide, and are involved in the metabolism of lignin and auxin and in the oxidation of toxic reductors [1].

Based on amino acids homologies, peroxidases are now classified into two superfamilies. The first superfamily clusters peroxidases from plant, archea bacteria, and fungi and is classified into three classes. Class I is composed of intracellular peroxidases such as yeast cytochrome c peroxidase, ascorbate peroxidase, and catalase peroxidase, Class II is formed by secretory fungal peroxidases such as manganese and lignin peroxidases, and Class III consists in secretory plant peroxidases including one of the most studied peroxidases, the horseradish peroxidase [4, 5]. The second one is called the peroxidase-cyclooxygenase superfamily and clusters mammalian peroxidases together with protein from invertebrate, bacterial, plant, and fungal species and other metalloproteins such as cyclooxygenase [5]. This latter superfamily originally called “the myeloperoxidase family” shares a domain of about 500 amino acids corresponding to the catalytic site [6] and is classified into several subfamilies; one of them is the chordata peroxidases in which the mammalian peroxidases are found [5]. The main clades are the myeloperoxidases (MPO), eosinophil peroxidases (EPO), and the lactoperoxidase (LPO) branch. Another clade consists in thyroid peroxidase (TPO) which is distantly related to MPO, EPO, and LPO [5].

MPO is a lysosomal constituent in neutrophils and macrophages and displays antimicrobial activity during the postinfection inflammatory process but is also involved in acute inflammatory diseases and in other pathologies such as atherosclerosis [7–10]. EPO is secreted in eosinophils and displays cytotoxic activity against parasites, bacteria, and fungi. It could be associated to allergic eosinophilic inflammatory disease pathologies [1, 10, 11]. LPO and salivary peroxidase are found in secretions of exocrine glands and are associated to antibacterial and antifungal activity [12–14]. Finally, TPO is a membrane enzyme localized in thyroid follicle cells that takes part in the synthesis of thyroid hormones [1].

This review summarizes present knowledge on the mode of action of lactoperoxidase which can be extended to the mammalian peroxidases mode of action and on the specific interaction of LPO with thiocyanate and iodide, together or alone, with implications on its antimicrobial activity.

2. Mode of Action of Lactoperoxidase

LPO is a calcium- and iron-containing glycoprotein arranged in a single polypeptide chain of about 80 kDa [15, 18, 19]. Human LPO is moderately cationic with a pI of ca. 7.5 but bovine LPO is more cationic with a pI of ca. 9.6 [18, 19]. MPO is a highly cationic (pI of ca. 10) dimeric protein of 146 kDa, each monomer containing one calcium and iron and joined together by a disulfide bridge [18]. The ion calcium plays an important role in the stability of both enzymes [19, 20]. The active site in LPO, MPO, EPO, and TPO is the heme which consists in a protoporphyrin IX derivative fixed covalently through two ester linkages via a conserved distal aspartate and glutamate residues, a third link being present in MPO and consisting in a thioether sulfonium bond with a methionine [4, 15, 19, 21]. These covalent bonds, which are specific for vertebrate peroxidases, result in a distortion of the symmetry and planarity of the prosthetic group and give the unique spectroscopic and redox properties of these proteins [4, 20, 21]. The proximal heme ligand is a highly conserved histidine residue which is hydrogen bonded to a conserved asparagine residue that acts as hydrogen-bond acceptor [20, 22]. On the distal heme site, a conserved histidine-arginine couple plays a role in the proton transfer during the formation of Compound I, and a conserved glutamine residue and several conserved water molecules are involved in a hydrogen-bond network acting in halide delivery and binding [4, 18, 20]. A conserved asparagine residue in LPO, EPO, and MPO located close to the distal histidine seems also critical for the catalysis mechanism [18, 20]. The substrate channel in LPO is narrower, longer, and more hydrophobic compared to MPO with the consequence that the LPO-active site seems to be less exposed to surrounding media [22, 23].

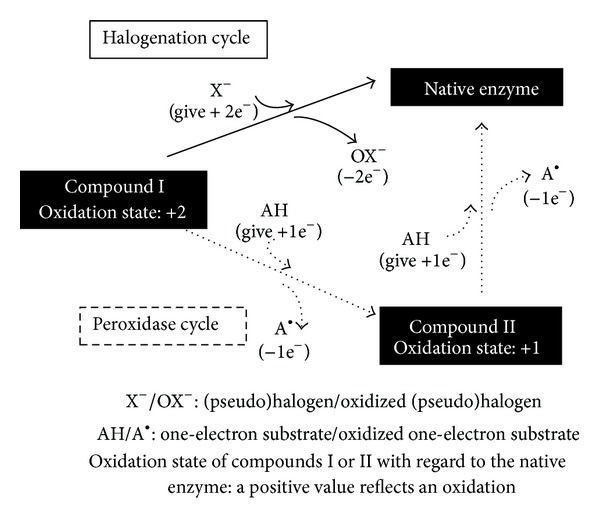

Heme peroxidases are oxidoreductase enzymes that act through different reaction mechanisms. Although some characteristics are specific to a member of the family, the same global procedure is followed by all members. The cycle begins with the transformation of the native enzyme into Compound I. Afterwards, and depending mainly on substrate concentrations, Compound I enters the halogenation cycle or the peroxidase cycle which both end by the enzyme returning to its native state (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Halogenation or peroxidase cycle of peroxidases Compound I.

2.1. Formation of Compound I

The first reaction of the native enzyme starts in the presence of hydrogen peroxide, which acts as a relatively specific electron acceptor [24]. Other substrates have been described, such as ethyl hydroperoxide, peroxyacetic acid, cumene hydroperoxide, and 3-chloroperoxybenzoic acid [20, 25]. Compound I is formed as follows:

| (1) |

The native enzyme undergoes a two-electron oxidation. Two electrons are transferred from the enzyme to hydrogen peroxide which is reduced into water. Compound I is two oxidizing equivalents above the native enzyme: one is in the oxyferryl heme center and the other is present as an organic cation located on the porphyrin ring [4, 26, 27]. Compound I is not specific regarding the electron donor [24] and the composition of the medium determines its subsequent cycle (see Figure 1). As Compound I is very unstable, an amino acid residue of the apoprotein is oxidized in the absence of an exogenous electron donor [14]. This reaction yields Compound I isomer that is very similar to Compound II regarding its iron redox state and its incapability to react with halogens [20].

2.2. The Halogenation Cycle

In the presence of a halogen (Cl−, Br−, or I−) or a pseudohalogen (SCN−), Compound I is reduced back to its native enzymatic form through a two-electron transfer while the (pseudo)halogen is oxidized into a hypo(pseudo)halide (see Figure 1). Hypo(pseudo)halides (OX−) are powerful oxidants with antimicrobial activity [14, 28–32]. The halogenation cycle is described by the following reaction:

| (2) |

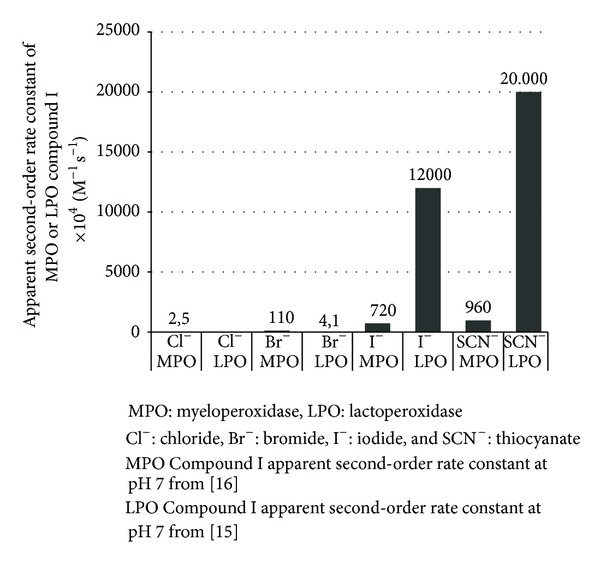

The oxidation rate of halogens by peroxidase-derived Compound I depends on various factors. One of these factors is the standard reduction potential of the enzyme, which differs among peroxidases and plays a role in their capacity to oxidize specific (pseudo)halides. The redox reaction can occur only if the reduction potential of the enzyme is equal or superior to the reduction potential of the substrate. The standard reduction potential at pH 7 of Compound I peroxidases and the couple of two-electron reduction HOX/X− is ranking in the following ascending rank: LPO Compound I < EPO Compound I < MPO Compound I; HOSCN/SCN− < HOI/I− ≪ HOBr/Br− < HOCl−/Cl− [17, 18, 33, 34]. This involves that only the MPO Compound I is able to oxidize Cl− with appropriate rates, LPO being able to oxidize with high rates I− and SCN− and slowly Br− [16, 17, 20, 33, 34]. Interestingly, although LPO Compound I has the lowest reduction potential compared to EPO Compound I and MPO Compound I, it catalyzes the oxidation of I− and SCN− with the highest rates (Figure 2) [15–17, 20]. This suggests that other factors play a role, such as anion size, anion access, and anion binding as well as structural and amino acid differences in the active and binding site between enzymes [17, 18, 20].

Figure 2.

Apparent second-order rate constant at pH 7 (×104 M−1 s−1) of the reaction between myeloperoxidase Compound I or lactoperoxidase Compound I with (pseudo)halides [15, 16].

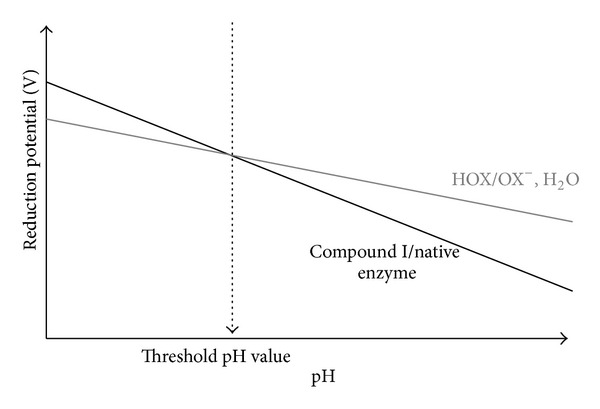

The reduction potential of the Compound I/native enzyme and HOX/X− redox couples depends on reactant concentrations and pH values. At a specific reactant concentration, it decreases with increasing pH values, but slopes differ (Figure 3) [17]. This means that there exists a threshold pH value above which the oxidation of halides becomes thermodynamically unfavorable, especially for halides with high reduction potential such as Cl− and Br− [17].

Figure 3.

Illustration (according to [17]) of the pH threshold value above which the oxidation of the halogen by mammalian heme peroxidase will be thermodically unfavorable. The reduction potential of the couple Compound I/native enzyme and the couple halogen (X = chloride, bromide) HOX/OX− is expressed with an illustrative function of the pH, at a specific concentration of enzyme and substrates.

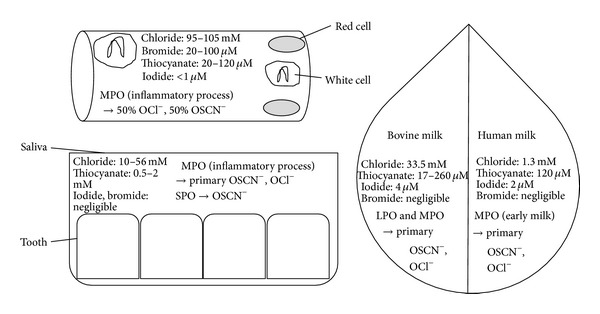

Concentrations of (pseudo)halogens also affect their affinity to Compound I (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Illustration of the interaction between the biodisponibility of a peroxidase, the (pseudo)halogen concentration in plasma, in saliva, and in milk, and the production of oxidant molecules. MPO: myeloperoxidase; SPO: salivary peroxidase; LPO: bovine lactoperoxidase; OCl−: hypochlorite; and OSCN−: hypothiocyanite. Although chloride is the most available substrate compared to thiocyanate, bromide, and iodide, thiocyanate is the most effective substrate for the Compound I and hypothiocyanite could be produced at equal or superior levels compared to hypohalides.

Although plasma Cl− concentrations are 1,000-fold higher than Br− and SCN−, MPO Compound I oxidizes similar amounts of SCN− and Cl− [35]. EPO Compound I preferentially oxidizes SCN− in the presence of physiological concentrations of SCN−, Br−, and I− [36]. In the saliva of healthy adults, where Cl− concentrations are only about 25-fold higher than SCN−, SPO Compound I and MPO Compound I primarily generate hypothiocyanite [37, 38]. The levels of I− in human milk, saliva, blood, and tissues except the thyroid gland are below 1 μM and its in vivo oxidation by Compound I is negligible [17, 38]. In human milk, peroxidase activity is only derived from leucocytes. As MPO is able to oxidize Cl− and Cl− milk concentration is high, oxidation of Cl− is possible although it has never been reported [14]. In bovine milk, lactoperoxidase is an abundant enzyme, and with mean concentrations of I− and SCN− of 310 μg/kg and 0.2–15 mg/kg, respectively, oxidation is possible [19, 39]. Nevertheless, the relative abundance of SCN− in all secretions, blood, and tissues and its better capacity as an electron donor make it one of the main in vivo substrates of Compound I lactoperoxidase and myeloperoxidase for 2-electron oxidation compared to halides [15]. In in vitro applications, the ratio between (pseudo)halides regulates the ratio of hypohalides generated by the reaction. However, as SCN− is the most effective substrate for Compound I, its presence, even in small quantities, enhances its oxidation [14, 35, 36].

2.3. The Peroxidase Cycle

Alternatively, Compound I can shift to the peroxidase cycle, which consists of two sequential one-electron transfers back to the enzyme that yield (i) Compound II and (ii) the native enzyme, while the substrate is oxidized into a radical (Figure 1) [40–42]. The peroxidase cycle is summarized in the following equations:

| (3) |

Compound I is not specific regarding the one-electron donor; it can be exogenous or endogenous, and a lot of candidates have been described [18, 20, 43]. Hydrogen peroxide can undergo a one-electron oxidation only with MPO Compound I, with the formation of superoxide [16, 20, 44, 45].

During the first step of the peroxidase cycle, the cation located in the porphyrin ring undergoes a one-electron reduction with formation of Compound II and concomitant oxidizing of one one-electron substrate [4, 24]. Compound II maintains one oxidizing equivalent in the oxyferryl center [4, 24]. Finally, this latter is reduced back to the native enzyme with the oxidation of a second one-electron donor.

The standard reduction potential of the couple Compound I/Compound II is high and allowed the one-electron oxidation by Compound I of a wide range of substrates [18, 20]. In contrast, the standard reduction potential of the couple Compound II/native enzyme is low and restrains the numbers of possible substrates for Compound II [18, 20]. With the result that (i) the Compound II/native enzyme standard reduction potential is too low to react with halogens and (ii) the nature of substrates strongly influenced their ability to be oxidized by mammalian peroxidase compound II [2, 14, 20], therefore, when the enzyme is in this state, it has to be first reduced to the ground state before possibly participating to the halogenation cycle and producing antimicrobial molecules [14]. Moreover, the reduction of Compound II to the ground state is the rate-limiting step [45, 46]; that is, the peroxidase cycle interferes with the halogenation cycle and slows down antimicrobial activity [47].

The peroxidase cycle has been described as a possible catalytic sink for nitric oxide (NO) [46] but also for hydrogen peroxide in the case of a moderate excess of H2O2 relative to LPO [24]. Increase of NO removal from media, even in presence of Cl−, after addition of MPO, EPO, or LPO and accelerated rates of Compound I and Compound II reduction in presence of NO show that peroxidases may regulate the bioavailability of NO [46]. In conditions of high excess of hydrogen peroxide relative to LPO and in the absence of an exogenous electron donor, Compound II is transformed into Compound III which is 3 oxidative equivalents above the native enzyme. In moderate excess conditions, Compound III can be partially reconverted into Compound II and can reenter the peroxidase cycle [24, 40]. Otherwise, the enzyme is irreversibly inactivated; the heme fraction is cleaved and iron is released [48]. In the presence of an exogenous two-electron donor, the enzyme is largely protected from hydrogen peroxide because the halogenation cycle is favored. Furthermore, protection is higher with iodide because oxidized iodide consumes H2O2 to produce oxygen and iodide in a reaction called the pseudocatalytic activity of peroxidase [24, 40, 49].

However, thiocyanate can act as a one-electron donor and be part of the peroxidase cycle, with the sequential formation of two thiocyanate radicals [47]. With 200 μM SCN−, LPO is predominantly in its native form; this indicates that the halogenation cycle prevails [47].

In the presence of both one- and two-electron donors, competition for oxidation can occur and favor the halogenation or the peroxidase cycle. The presence of EDTA inhibits the oxidation of iodide due to competition for binding to Compound I [50]. The standard reduction potential between the donors favors the molecule with the lowest reduction potential. Thereby, the respective reduction potentials of the one- and two-electron oxidation of thiocyanate at very low pH are 1.65 V and 0.82 V and promote the halogenation cycle [51]. In the case of low concentrations of halides or thiocyanate, below 10 μM I− or 3 μM SCN−, Compound I reacts with any suitable exogenous or endogenous one-electron donor, with the subsequent formation of Compound II and a negligible oxidation rate of halides and thiocyanate [14].

2.4. Inhibition of the Function of Mammalian Heme Peroxidase

The function of heme peroxidases can be inhibited in several ways that could be classified into three categories. The first one could represent an inhibition of the enzyme by (i) molecules or proteins and (ii) external conditions such as pH and temperature. For example, cyanide, azide, nitrite, mercaptomethylimidazole, thiourea, superoxide, high levels of nitric oxide, and high levels of thiocyanate bind to the native enzyme and alter Compound I formation [20, 46, 47, 52–54]. With thiocyanate, inhibition is linked to the restriction of the binding site to hydrogen peroxide and the interaction of SCN− with a water molecule [23]. High concentration of H2O2 or I− will inactivate irreversibly LPO with liberation of free iron [48, 55]. Temperature between 73°C and 83°C, depending on the heating time, results in unfolding and inactivation of LPO [19]. Extreme pH is inactivating enzymes and at low pH an amino acid group, probably histidine, is protonated which prevents the binding of H2O2 [56]. Some proteases such as pepsin and pronase are able to inactivate LPO by proteolysis but chymotrypsin did it very slowly and trypsin and thermolysin are not active against LPO [19].

The second group of inhibitors could concern substances or proteins which are able to interfere with the catalytic mechanism. For example, catalase consumes H2O2 and will stop the formation of Compound I [30, 52]. Competition between substrates can also interfere with the reaction cycle such as SCN− which competes very effectively with Cl−, Br−, and I− [52, 53]. HOCl has the capacity to bind to LPO native enzyme and convert it into Compound I. Above 100 μM, HOCl mediates the destruction of the LPO heme center [57].

The third class could be related to substances or proteins which are buffering active molecules produced during the catalytic reaction. For example, presence of thiosulfate, thioglycolate, glutathione, dithiothreitol, cysteine, NAD(P)H, and tyrosine will reduce the antimicrobial activity through reacting with OCl−, OBr−, OI−, or OSCN− [52, 53, 58, 59]. The enzyme NADH-OSCN oxidoreductase is able to reduce OSCN− in SCN− [60].

3. Activity of Lactoperoxidase with Thiocyanate and/or Iodide

LPO concentrations in cow's milk are around 30 mg L−1 depending on season, diet, and calving and breeding season [61]. LPO extraction from whey or milk is based on a well-developed industrial process [62]. Compared to MPO and EPO, LPO is easily isolated and manufactured in large quantities. As a result, cow's milk peroxidase is the favorite molecule for in vitro or in vivo applications such as conservation of raw and pasteurized milk, storage of emulsions and cosmetics, moisturizing gel and toothpaste in human dry mouth, veterinary products, and preservation of foodstuffs [19, 61, 63, 64].

3.1. Activity of LPO Related to Hypothiocyanite

3.1.1. Mode of Action of Hypothiocyanite

Thiocyanate is oxidized in a two-electron reaction that yields hypothiocyanite. Hypothiocyanite has a pKa of 5.3 [65]. It is more acidic than hypohalides that have pKas of 7.5 (HOCl), 8.6 (HOBr), and 10.6 (HOI) [14, 66]. All hypo(pseudo)halides (OX−) are in an acid-base equilibrium association with their corresponding acid hypo(pseudo)halide (HOX). For example, in the case of hypothiocyanite,

| (4) |

The acid form has a higher oxidation potential and is more soluble in nonpolar media so that it passes through hydrophobic barriers such as cell membranes more easily but it is less stable than the basic form (OX−) [14, 66]. Hypohalide acids are predominant in acidic to neutral media and even in basic conditions for HOBr and HOI, whereas hypothiocyanite needs a pH below 5.3 to be predominant in the acid form [66, 67].

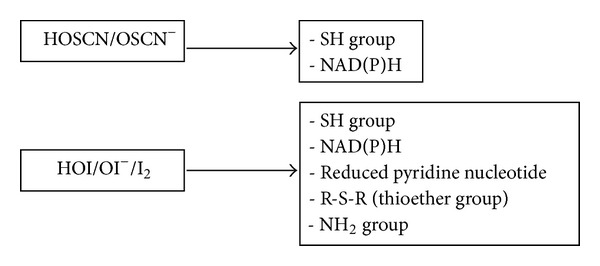

SCN− is the two-electron donor with the lowest reduction potential and therefore forms the hypothiocyanite acid with the lowest oxidative power compared to hypohalous acids. Hypohalous acids rank as follows, with increasing oxidative strength: OSCN− < OI− < OBr− < OCl− [28, 66]. These characteristics make hypothiocyanite relatively specific regarding its molecular target (Figure 5), that is, a thiol moiety [28, 59, 68].

Figure 5.

Target group of hypothiocyanite, hypoiodite, and iodine. Due to its low oxidation power, hypothiocyanite is relatively specific and is not reactive against all thiols. In vivo, hypoiodite seems to be selectively directed against reduced pyridine nucleotide because even the presence of excess glutathione and methionine does not thoroughly inhibit their oxidation. HOSCN/OSCN−: acidic or basic form of hypothiocyanite; HOI/OI−: acidic or basic form of hypoiodite; and I2: iodine.

Sulfhydryl oxidation by OSCN− generates sulfenyl thiocyanate, in equilibrium with sulfenic acid [68]:

| (5) |

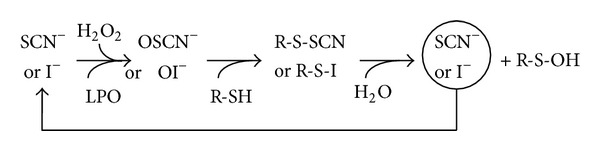

The cycle of reactions shows that thiocyanate acts like a cofactor for LPO (Figure 6) so that the total number of oxidized sulfhydryls is independent of SCN− as long as (i) thiocyanate is not exhausted, (ii) thiocyanate is not in competition with other substrates for the binding to Compound I, (iii) thiocyanate is not incorporated into an aromatic amino acid, (iv) enough H2O2 is present, and (v) thiol moiety is still available [68, 69].

Figure 6.

Illustration of the cofactor role of SCN− or I−. When the necessary conditions are fulfilled, that is, (i) no substrate competitor for SCN− or I− for binding to lactoperoxidase, (ii) enough peroxidase, H2O2 and SCN− or I−, (iii) enough R-SH, and (iv) no incorporation of SCN− or I− in stable byproducts, the quantity of OSCN− or OI− produced depends only on the amount of H2O2. SCN−: thiocyanate; I−: iodide; H2O2: hydrogen peroxide; LPO: lactoperoxidase; R-SH: peptide or protein with a thiol moiety; R-S-SCN or R-S-I sulfenyl thiocyanate or iodide; R-SOH: sulfenic acid; OSCN−: hypothiocyanite; and OI−: hypoiodite.

Although the target of OSCN− is a thiol moiety, not all sulfhydryls are equally sensitive to OSCN−; albumin, cysteine, mercaptoethanol, dithiothreitol, glutathione, and 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoic acid are all oxidized but β-lactoglobulin is poorly oxidized, probably due to a limited accessibility of sulfhydryls to OSCN− [68]. In some conditions, that is, the joint presence of LPO, enough H2O2 and SCN−, and after the oxidation of available sulfhydryls, modification of tyrosine, tryptophan, and histidine protein residues can occur and that could be linked to the formation of a labile powerful oxidant such as sulfur dicyanide [68].

Some authors suggest that (SCN)2 is formed during the enzymatic reaction and then chemically hydrolyzed into hypothiocyanite [14, 69, 70]. However, a recent publication demonstrates that (SCN)2 cannot be a precursor during the enzymatic oxidation of SCN− at neutral pH in mammals [71].

Hypothiocyanite is less stable in acid conditions, with high concentrations of SCN− and in the presence of (SCN)2, and it is thought to break down via the following net reaction [14]:

| (6) |

A recent study, based notably on spectroscopic and chromatographic methods, proposes the following net equation within the 4–7 pH range:

| (7) |

The proportions of end anions were different at pH 4 and pH 7; at pH 7, the proportion of CNO− was higher, SCN− formation was slower, and no CN− was detected [71].

It might seem easier to produce hypothiocyanite chemically in in vitro applications, but producing hypothiocyanite chemically from the oxidation of SCN− by a halogen (Cl2 or Br2) or by a hypohalous acid (HOCl or HOBr) in basic media is tricky due to overoxidation of SCN− [66]. The reference method in the literature to produce 1- to 2-day stable OSCN− is by hydrolyzing (SCN)2 in basic conditions [72–74].

Hypothiocyanite inhibitors have been described. For example CN−, a weak acid buffer, dissolved carbonate, excess hydrogen peroxide, hydrofluoric acid, metallic ions, glycerol, or ammonium sulfate accelerates the decomposition of OSCN−, whereas sulfonamide stabilizes it [67, 72].

Appropriate concentrations of substrates induce enhanced activity [75].

3.1.2. Biological Activity of Hypothiocyanite

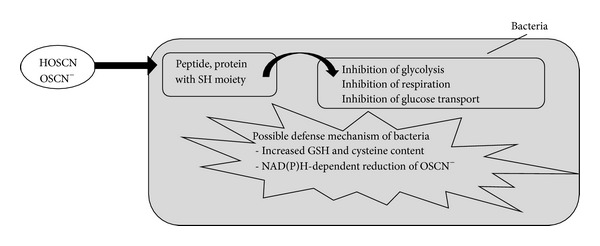

The biological activity of hypothiocyanite is summarized in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Biological activity of hypothiocyanite on bacteria and possible defense mechanism of the bacteria. Reversible inhibition is observed in that (i) hypothiocyanite is not reactive against all thiols and (ii) if hypothiocyanite is removed or diluted, the pathogen recovers. Irreversible inhibition is linked to (i) long period of incubation, (ii) the bacterial species, and (iii) hypothiocyanite concentration. HOSCN/OSCN−: acidic or basic form of hypothiocyanite and GSH: glutathione.

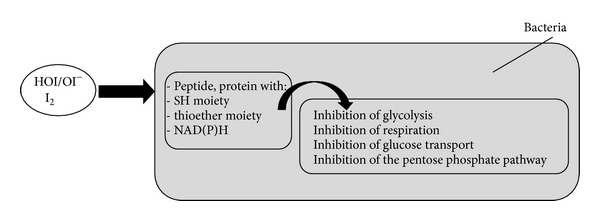

The sulfhydryl moiety is essential for the activity of numerous enzymes and proteins. Inhibition of bacterial glycolysis through the oxidation of hexokinase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), aldolase, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase has been observed [14, 51, 65, 70, 76]. Inhibition of respiration and glucose transport is associated with the alteration of cell membranes or transporters [14, 51, 65, 77]. Irreversible inhibition is linked to long periods of incubation and bacterial sensitivity depends on the bacterial species and on hypothiocyanite concentrations [14, 51, 59]. Increased concentrations of reducing agents such as glutathione and cysteine can reverse the inhibition through buffering hypothiocyanite and converting the reduced thiol back into sulfhydryl [14, 78]. This defense mechanism is used by Escherichia coli; it induces the CysJ promoter during the stress response to the lactoperoxidase system [79]. Another resistance mechanism could be the NAD(P)H-dependent reduction of OSCN− without any loss of the sulfhydryl compound [14, 72, 78]. Alteration of the bacterial membrane increases the efficacy of hypothiocyanite [80].

Furthermore, the activity of the entire system (enzyme + substrates) is known to be more effective than hypothiocyanite alone, whether enzymatically or chemically produced. This has been explained by the production of short-lived, highly reactive intermediates such as O2SCN− and O3SCN− by the enzyme or by the oxidation of OSCN− in conditions of excess H2O2 [65, 73, 81]. The activity of hypothiocyanite has been described against bacteria such as Actinomyces spp., Bacillus cereus, Lactobacillus spp., Staphylococcus albus, S. aureus, Streptococcus spp., Escherichia coli, Legionella pneumophila, Salmonella typhimurium, Pseudomonas fluorescens, P. aeruginosa, Campylobacter jejuni, C. coli, and Listeria monocytogenes [14, 32]. Reversible inhibition is observed when cells recover after OSCN− is depleted [14, 59]. Irreversible inhibition is obtained with long-term incubation and high level of OSCN− [59]. Higher concentration of SCN− compared to I− is necessary to obtain inhibition against E. coli and accumulation of OSCN− is observed as it is not reactive against all thiols [59]. Therefore, the activity of the SCN−-LPO system appears to be more bacteriostatic than bactericidal.

3.2. Activity of LPO Related to Oxidized Iodide

3.2.1. Chemistry of Oxidized Iodide

Iodide is oxidized by Compound I through a single two-electron transfer that yields oxidized I− in the form of I2 or HOI [14, 24, 82–85]. The active agent is composed of a mixture of species that are not yet formally detailed due to the very complex behavior and stability of I2 and HOI in aqueous environments that strongly depend on pH values and iodide concentrations [66, 82, 83, 86].

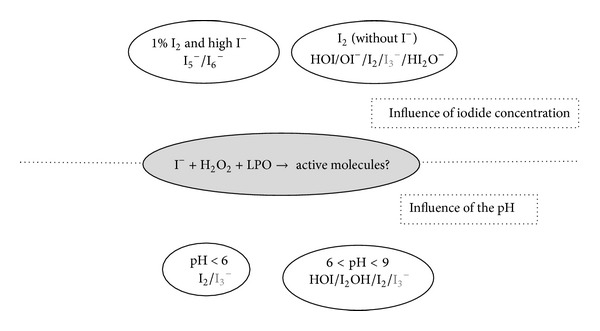

Based on the inorganic chemistry of iodine in water and literature on enzymatic oxidation of iodide, the active molecules have been described as follows (Figure 8).

-

(i)Under pH 6 and in the presence of iodide, only I2, I−, and I3 − are present and the only active molecule is I2. I2 concentrations decrease with increasing concentrations of I−. At an initial 1 mM I2, with I− concentrations ranging from 1 mM to 100 mM, I2 concentrations fall from almost 1 mM to 0,01 mM, as described by the following association reaction [24, 82, 83, 86]:

(8) -

(ii)In solution within a 6–9 pH range and with a maximum 1 mM iodide, a mixture of HOI/I2OH/I2/I3 − is formed in which I3 − is not active and I2OH is probably less reactive than HOI or I2 [86, 87]. If I− concentrations are above 10 mM, I3 − represents the main species formed and the concentration of active molecules relatively drops. The mechanism is summarized in the following net equations:

(9) -

(iii)In iodine solution, without iodide or when available iodide has been oxidized, the number of I2-derived molecules decreases with decreasing I2 concentrations. At 1,000 μM I2, with pH-related ratios, five relevant species are observed (I2, HOI, I3 −, HI2O−, and OI−). At 10 μM I2, the main species are only I2, HOI, and OI−, and HOI could represent up to 90% of the active oxidant molecules at pH 8-9 [86]. Below a pH of 10.6, the following reactions are involved:

(10) -

(iv)At high I− and 1% I2 concentrations as in Lugol solution, I5 − and I6 − are formed and represent 8.2% of the active oxidative agents [86], after the following reaction:

(11)

Figure 8.

Illustration of the molecules that can be present after oxidation of iodide by lactoperoxidase in presence of H2O2. The active species depend mainly on the concentration of iodide (upper part) and the pH (lower part). The species with an oxidant power are represented in bold.

The stability of HOI and I2 is linked to their disproportionation in iodate, which has no oxidative activity in neutral and basic pH conditions [86]. The disproportionation reactions read as follows:

| (12) |

I2 stability increases at higher pH values and higher iodide concentrations [86]. In drinking water, HOI disproportionation is slow and varies substantially; HOI has a half-life of 4 days to 3.5 years depending on (i) the initial level of HOI that speeds its decomposition and (ii) the presence of borate, phosphate, or carbonate that catalyzes its decomposition [88, 89].

3.2.2. Mode of Action of Oxidized Iodide

The oxidative strength of I2 is between that of the corresponding hypohalous acid HOI and the hypoiodite ion OI− and ranks as follows: 0.485 V (OI−) < 0.536 V (I2) < 0.987 V (HOI) [66].

HOI reacts through very rapid oxidation of thiol groups, oxidation of NAD(P)H, oxidation of β-nicotinamide mononucleotide, direct reaction with thioether groups through sulfoxidation, and slow oxidation of the amine moiety (Figure 5) [87, 90, 91]. At low I− concentrations, iodination of tyrosine residues is catalyzed by the enzyme [14]. In a cellular environment, HOI seems to be more selectively directed against the degradation of reduced pyridine nucleotides than HOCL and HOBr because even the presence of excess glutathione, methionine, or oxidized glutathione does not thoroughly inhibit their oxidation [87].

In some conditions, that is, (i) enough iodide, H2O2, and peroxidase, (ii) no accumulation of oxidized iodide, and (iii) no incorporation of iodide into stable byproducts such as tyrosine residues, iodide acts as a cofactor (Figure 6) and the proportion of oxidized sulfhydryls is proportional to the amount of H2O2 as described below [85, 92]:

| (13) |

In the case of high concentrations of I− and/or H2O2, inhibition of tyrosine iodation has been observed [83] and related to the pseudocatalytic redox degradation of H2O2 with formation of O2 when excessive H2O2 is present (reaction 1) and production of I3 − when excessive amounts of I− are present (reaction 2):

| (14) |

Both reactions deplete the amount of the active oxidizing agent I2. In the absence of tyrosine, oxidized iodide reacts with nucleophilic molecules such as I−, Cl−, or OH− to form I2, I3 −, ICl, ICl2, IOH, and I2OH [82]. Some anions such as Cl−, HPO4 −, or OH− reduce the amount of I2/I3 − but this effect is inversely proportional to the concentration of I−; above pH 9, I2 is hydrolyzed and IO3 − is formed [82].

HOI can be produced chemically through oxidation of I− by Cl2 or O3, with a short half-life due to overoxidation of HOI by Cl2 and O3 [89] and through oxidation of I− by HOCl, HOBr, or NH2Cl with a longer half-life [87, 89].

3.2.3. Biological Action of Oxidized Iodide

The biological action of oxidized iodide (Figure 9) is similar to that of hypothiocyanite but differs in that (i) the reactivity of oxidized iodide is complete against thiol group and (ii) cells did not recover after removing of oxidized iodide [59].

Figure 9.

Biological activity of hypoiodite or iodine on bacteria. Irreversible inhibition is observed and could be linked to (i) oxidation of thiol groups, NAD(P)H, and thioether groups, (ii) high reactivity of HOI/I2 against thiol and reduced nicotinamide nucleotides, and (iii) the incorporation of iodide in tyrosine residue of protein (iodination of protein). HOI/OI−: acid or basic form of hypoiodite and I2: iodine.

Due to the cofactor role of I−, inhibition of respiration in Escherichia coli in the presence of LPO, H2O2, and I− is complete with only 10 μM NaI, whereas 100 μM of solely I2 is necessary to obtain complete inhibition. This is directly related to the oxidation of sulfhydryls, not to the percentage of iodine incorporation [92, 93].

E. coli seems to be more sensitive if the bacteria are incubated together with the entire system (enzyme, H2O2, and iodide) rather than adding several minutes after mixing the enzyme with its substrates. This could be linked to the formation of an unstable reactive intermediate [52].

The activity of the I− peroxidase system is more effective against E. coli than the SCN− system, in that lower I− concentrations are necessary, all sulfhydryls are oxidized, and cells do not recover even if the amount of I2 is not sufficient to oxidize all SH groups [59, 80]. Against L. acidophilus, high non physiological amounts of I− are necessary to obtain inhibition whereas small concentrations of SCN− are effective [70].

CN−, azide, EDTA, and SCN− inhibit the formation of oxidized iodide [50, 52]. Increased pH values and increased amounts of thiol and NAD(P)H compounds reduce the activity of the iodide peroxidase system [52].

LPO-H2O2-I− in presence of Streptococcus mitis is active against Staphylococcus aureus and E. coli [94]. LPO-H2O2-I− is active against Micrococcus, S. aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, Bacillus cereus, E. coli, and Candida albicans [12, 19, 80]. In the presence of other peroxidases, the I− peroxidase system is active against Schistosoma mansoni, Fusarium nucleatum, and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans [31, 95, 96]. Compared to SCN−, I−-LPO shows bactericidal activities [14, 19, 80].

3.3. Activity of LPO Related to Hypoiodite and Hypothiocyanite

The combination of SCN− with I− in the lactoperoxidase system has been poorly studied. Tackling the enzymatic mechanism is tricky, and contradictory results have been found about microbial activity in the concomitant presence of SCN− and I−.

In the presence of SCN− and I−, there is competition between the two substrates for oxidation by lactoperoxidase [14, 36]. I− alone exhibits bactericidal activity, but an SCN−/I− ratio of 0.1 inhibits that bactericidal effect, and an SCN−/I− ratio of 1 antagonizes it due to competition for oxidation and faster decomposition of HOSCN in the presence of I− [14]. Against A. actinomycetemcomitans, the peroxidase system with I−, Cl−, or a combination of I− and Cl− is effective but addition of SCN− cancels the antibacterial effect [96]. On the other hand, a synergistic or unaffected effect of iodide in the SCN−-H2O2-LPO system has been shown against Candida albicans, E. coli, S. aureus, Aspergillus niger, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [19, 97].

4. Conclusion

The molecular evolution of heme peroxidases and the preservation of their catalytic domain [6] show that the production of strong oxidants is a powerful part of the nonimmune defense mechanisms against pathogenic bacteria, fungi, or parasite which made the use of those enzymes in practical applications worthwhile.

The enzymatic reactions involving mammalian peroxidases are complex and various molecules can promote or reduce dramatically the antibacterial activity of the peroxidase system. In order to favor the halogenation cycle required in in vitro and in vivo antimicrobial applications, several points have to be taken into account: (i) to avoid the presence of competitors to iodide or thiocyanate for binding to Compound I and to avoid the presence of inhibitors of the enzyme or of active molecules, (ii) to avoid excess H2O2 concentration which is able to destruct the enzyme and to react with iodine or hypoiodite with loosing of active molecules, (iii) to favor the presence of hypoiodite instead of iodine due to the association reaction of iodine with iodide, (iv) to avoid excess concentration of thiocyanate which can inhibit formation of Compound I, (v) to use the entire system (enzyme + substrates) instead of active molecules alone, (vi) to favor moderate acid pH when hypothiocyanite is the active molecule, (vii) for bactericidal, fungicidal, or parasitical applications, the use of iodide has to be preferred, (viii) the use of combined presence of iodide and thiocyanate has to be checked carefully for efficacy, and (ix) to favor the cofactor role of iodide or thiocyanate.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.O'Brien PJ. Peroxidases. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2000;129(1-2):113–139. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jantschko W, Furtmüller PG, Allegra M, et al. Redox intermediates of plant and mammalian peroxidases: a comparative transient-kinetic study of their reactivity toward indole derivatives. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2002;398(1):12–22. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimura S, Ikeda-Saito M. Human myeloperoxidase and thyroid peroxidase, two enzymes with separate and distinct physiological functions, are evolutionarily related members of the same gene family. Proteins: Structure, Function and Genetics. 1988;3(2):113–120. doi: 10.1002/prot.340030206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battistuzzi G, Bellei M, Bortolotti CA, Sola M. Redox properties of heme peroxidases. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2010;500(1):21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zamocky M, Jakopitsch C, Furtmüller PG, Dunand C, Obinger C. The peroxidase-cyclooxygenase superfamily: reconstructed evolution of critical enzymes of the innate immune system. Proteins: Structure, Function and Genetics. 2008;72(2):589–605. doi: 10.1002/prot.21950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daiyasu H, Toh H. Molecular evolution of the myeloperoxidase family. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 2000;51(5):433–445. doi: 10.1007/s002390010106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serteyn D, Grulke S, Franck T, Mouithys-Mickalad A, Deby-Dupont G. Neutrophile myeloperoxidase, protective enzyme with strong oxidative activities. Annales de Medecine Veterinaire. 2003;147(2):79–93. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitman SC, Hazen SL, Miller DB, Hegele RA, Heinecke JW, Huff MW. Modification of type III VLDL, their remnants, and VLDL from apoE- knockout mice by p-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, a product of myeloperoxidase activity, causes marked cholesteryl ester accumulation in macrophages. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 1999;19(5):1238–1249. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.5.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrett TJ, Hawkins CL. Hypothiocyanous acid: benign or deadly? Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2012;25(2):263–273. doi: 10.1021/tx200219s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lloyd MM, van Reyk DM, Davies MJ, Hawkins CL. Hypothiocyanous acid is a more potent inducer of apoptosis and protein thiol depletion in murine macrophage cells than hypochlorous acid or hypobromous acid. Biochemical Journal. 2008;414(2):271–280. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Slungaard A. Role of eosinophil peroxidase in host defense and disease pathology. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2006;445(2):256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahariz M, Courtois P. Candida albicans susceptibility to lactoperoxidase-generated hypoiodite. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dentistry. 2010;2:69–78. doi: 10.2147/cciden.s10891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welk A, Meller C, Schubert R, Schwahn C, Kramer A, Below H. Effect of lactoperoxidase on the antimicrobial effectiveness of the thiocyanate hydrogen peroxide combination in a quantitative suspension test. BMC Microbiology. 2009;9, article 134 doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pruitt KM, Tenovuo JO, editors. The Lactoperoxidase System: Chemistry and Biological Significance. Vol. 27. New York, NY, USA: Marcel Dekker; 1985. (Immunology Series). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furtmüller PG, Jantschko W, Regelsberger G, Jakopitsch C, Arnhold J, Obinger C. Reaction of lactoperoxidase compound I with halides and thiocyanate. Biochemistry. 2002;41(39):11895–11900. doi: 10.1021/bi026326x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furtmuller PG, Burner U, Obinger C. Reaction of myeloperoxidase compound I with chloride, bromide, iodide, and thiocyanate. Biochemistry. 1998;37(51):17923–17930. doi: 10.1021/bi9818772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnhold J, Monzani E, Furtmüller PG, Zederbauer M, Casella L, Obinger C. Kinetics and thermodynamics of halide and nitrite oxidation by mammalian heme peroxidases. European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2006;(19):3801–3811. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies MJ, Hawkins CL, Pattison DI, Rees MD. Mammalian heme peroxidases: from molecular mechanisms to health implications. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2008;10(7):1199–1234. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Wit JN, van Hooydonk ACM. Structure, functions and applications of lactoperoxidase in natural antimicrobial systems. Nederlands melk en Zuiveltijdschrift. 1996;50(2):227–244. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furtmüller PG, Zederbauer M, Jantschko W, et al. Active site structure and catalytic mechanisms of human peroxidases. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2006;445(2):199–213. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zederbauer M, Furtmüller PG, Brogioni S, Jakopitsch C, Smulevich G, Obinger C. Heme to protein linkages in mammalian peroxidases: impact on spectroscopic, redox and catalytic properties. Natural Product Reports. 2007;24(3):571–584. doi: 10.1039/b604178g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Battistuzzi G, Bellei M, Vlasits J, et al. Redox thermodynamics of lactoperoxidase and eosinophil peroxidase. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2010;494(1):72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheikh IA, Singh A, Singh N, et al. Structural evidence of substrate specificity in mammalian peroxidases: structure of the thiocyanate complex with lactoperoxidase and its interactions at 2.4 å 2.4 Å resolution. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(22):14849–14856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807644200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohler H, Jenzer H. Interaction of lactoperoxidase with hydrogen peroxide. Formation of enzyme intermediates and generation of free radicals. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1989;6(3):323–339. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furtmüller PG, Burner U, Jantschko W, Regelsberger G, Obinger C. Two-electron reduction and one-electron oxidation of organic hydroperoxides by human myeloperoxidase. FEBS Letters. 2000;484(2):139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taurog A, Dorris ML, Doerge DR. Mechanism of simultaneous iodination and coupling catalyzed by thyroid peroxidase. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1996;330(1):24–32. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erman JE, Vitello LB, Matthew Mauro J, Kraut J. Detection of an oxyferryl porphyrin π-cation-radical intermediate in the reaction between hydrogen peroxide and a mutant yeast cytochrome c peroxidase. Evidence for tryptophan-191 involvement in the radical site of compound I. Biochemistry. 1989;28(20):7992–7995. doi: 10.1021/bi00446a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashby MT. Inorganic chemistry of defensive peroxidases in the human oral cavity. Journal of Dental Research. 2008;87(10):900–914. doi: 10.1177/154405910808701003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chandler JD, Day BJ. Thiocyanate: a potentially useful therapeutic agent with host defense and antioxidant properties. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2012;84(11):1381–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jong EC, Henderson WR, Klebanoff SJ. Bactericidal activity of eosinophil peroxidase. Journal of Immunology. 1980;124(3):1378–1382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jong EC, Mahmoud AAF, Kelbanoff SJ. Peroxidase-mediated toxicity to schistosomula of Schistosoma mansoni. Journal of Immunology. 1981;126(2):468–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolfson LM, Sumner SS. Antibacterial activity of the lactoperoxidase system: a review. Journal of Food Protection. 1993;56(10):887–892. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-56.10.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnhold J, Furtmüller PG, Regelsberger G, Obinger C. Redox properties of the couple compound I/native enzyme of myeloperoxidase and eosinophil peroxidase. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2001;268(19):5142–5148. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furtmüller PG, Arnhold J, Jantschko W, Zederbauer M, Jakopitsch C, Obinger C. Standard reduction potentials of all couples of the peroxidase cycle of lactoperoxidase. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2005;99(5):1220–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Dalen CJ, Whitehouse MW, Winterbourn CC, Kettle AJ. Thiocyanate and chloride as competing substrates for myeloperoxidase. Biochemical Journal. 1997;327(2):487–492. doi: 10.1042/bj3270487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slungaard A, Mahoney JR., Jr. Thiocyanate is the major substrate for eosinophil peroxidase in physiologic fluids: implications for cytotoxicity. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266(8):4903–4910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tenovuo J. Antimicrobial function of human saliva—how important is it for oral health? Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 1998;56(5):250–256. doi: 10.1080/000163598428400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ihalin R, Loimaranta V, Tenovuo J. Origin, structure, and biological activities of peroxidases in human saliva. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2006;445(2):261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rooke JA, Flockhart JF, Sparks NH. The potential for increasing the concentrations of micro-nutrients relevant to human nutrition in meat, milk and eggs. Journal of Agricultural Science. 2010;148(5):603–614. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kohler H, Taurog A, Dunford HB. Spectral studies with lactoperoxidase and thyroid peroxidase: interconversions between native enzyme, compound II, and compound III. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1988;264(2):438–449. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90309-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamazaki I, Mason HS, Piette L. Identification, by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, of free radicals generated from substrates by peroxidase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1960;235:2444–2449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chance B. The kinetics and stoichiometry of the transition from the primary to the secondary peroxidase peroxide complexes. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1952;41(2):416–424. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(52)90470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pruitt KM, Mansson-Rahemtulla B, Baldone DC, Rahemtulla F. Steady-state kinetics of thiocyanate oxidation catalyzed by human salivary peroxidase. Biochemistry. 1988;27(1):240–245. doi: 10.1021/bi00401a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bolscher BGJM, Wever R. A kinetic study of the reaction between human myeloperoxidase, hydroperoxides and cyanide: inhibition by chloride and thiocyanate. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta: Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology. 1984;788(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(84)90290-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marquez LA, Huang JT, Brian Dunford H. Spectral and kinetic studies on the formation of myeloperoxidase compounds I and II: roles of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide. Biochemistry. 1994;33(6):1447–1454. doi: 10.1021/bi00172a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abu-Soud HM, Hazen SL. Nitric oxide is a physiological substrate for mammalian peroxidases. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(48):37524–37532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.48.37524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tahboub YR, Galijasevic S, Diamond MP, Abu-Soud HM. Thiocyanate modulates the catalytic activity of mammalian peroxidases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(28):26129–26136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jenzer H, Jones W, Kohler H. On the molecular mechanism of lactoperoxidase-catalyzed H2O2 metabolism and irreversible enzyme inactivation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261(33):15550–15556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Magnusson RP, Taurog A, Dorris ML. Mechanism of iodide-dependent catalatic activity of thyroid peroxidase and lactoperoxidase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1984;259(1):197–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhattacharyya DK, Bandyopadhyay U, Banerjee RK. EDTA inhibits lactoperoxidase-catalyzed iodide oxidation by acting as an electron-donor and interacting near the iodide binding site. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 1996;162(2):105–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00227536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hawkins CL. The role of hypothiocyanous acid (HOSCN) in biological systems HOSCN in biological systems. Free Radical Research. 2009;43(12):1147–1158. doi: 10.3109/10715760903214462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klebanoff SJ. Iodination of bacteria: a bactericidal mechanism. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1967;126(6):1063–1078. doi: 10.1084/jem.126.6.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klebanoff SJ. Myeloperoxidase-halide-hydrogen peroxide antibacterial system. Journal of Bacteriology. 1968;95(6):2131–2138. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.6.2131-2138.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Banerjee RK, Datta AG. Salivary peroxidases. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 1986;70(1):21–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00233801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huwiler M, Jenzer H, Kohler H. The role of compound III in reversible and irreversible inactivation of lactoperoxidase. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1986;158(3):609–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wever R, Kast WM, Kasinoedin JH, Boelens R. The peroxidation of thiocyanate catalysed by myeloperoxidase and lactoperoxidase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)/Protein Structure and Molecular. 1982;709(2):212–219. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(82)90463-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Souza CEA, Maitra D, Saed GM, et al. Hypochlorous acid-induced heme degradation from lactoperoxidase as a novel mechanism of free iron release and tissue injury in inflammatory diseases. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027641.e27641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carlsson J. Bactericidal effect of hydrogen peroxide is prevented by the lactoperoxidase-thiocyanate system under anaerobic conditions. Infection and Immunity. 1980;29(3):1190–1192. doi: 10.1128/iai.29.3.1190-1192.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas EL, Aune TM. Lactoperoxidase, peroxide, thiocyanate antimicrobial system: correlation of sulfhydryl oxidation with antimicrobial action. Infection and Immunity. 1978;20(2):456–463. doi: 10.1128/iai.20.2.456-463.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carlsson J, Iwami Y, Yamada T. Hydrogen peroxide excretion by oral streptococci and effect of lactoperoxidase-thiocyanate-hydrogen peroxide. Infection and Immunity. 1983;40(1):70–80. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.1.70-80.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kussendrager KD, van Hooijdonk ACM. Lactoperoxidase: physico-chemical properties, occurrence, mechanism of action and applications. The British Journal of Nutrition. 2000;84(supplement 1):S19–S25. doi: 10.1017/s0007114500002208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perraudin JP. Protéines à activités biologiques: lactoferrine et lactoperoxydase. Connaissances récemment acquises et technologies d'obtention. Lait. 1991;71(2):191–211. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boots J-W, Floris R. Lactoperoxidase: From catalytic mechanism to practical applications. International Dairy Journal. 2006;16(11):1272–1276. [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Hooijdonk ACM, Kussendrager KD, Steijns JM. In vivo antimicrobial and antiviral activity of components in bovine milk and colostrum involved in non-specific defence. British Journal of Nutrition. 2000;84, supplement 1:S127–S134. doi: 10.1017/s000711450000235x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hogg DM, Jago GR. The antibacterial action of lactoperoxidase. The nature of the bacterial inhibitor. Biochemical Journal. 1970;117(4):779–790. doi: 10.1042/bj1170779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ashby MT. Hypothiocyanite. In: van Eldik R, Ivana I-B, editors. Advances in Inorganic Chemistry. chapter 8. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 2012. pp. 263–303. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thomas EL. Lactoperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation of thiocyanate: equilibria between oxidized forms of thiocyanate. Biochemistry. 1981;20(11):3273–3280. doi: 10.1021/bi00514a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aune TM, Thomas EL. Oxidation of protein sulfhydryls by products of peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation of thiocyanate ion. Biochemistry. 1978;17(6):1005–1010. doi: 10.1021/bi00599a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aune TM, Thomas EL. Accumulation of hypothiocyanite ion during peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation of thiocyanate ion. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1977;80(1):209–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oram JD, Reiter B. The inhibition of streptococci by lactoperoxidase, thiocyanate and hydrogen peroxide. The effect of the inhibitory system on susceptible and resistant strains of group N streptococci. Biochemical Journal. 1966;100(2):373–381. doi: 10.1042/bj1000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kalmár J, Woldegiorgis KL, Biri B, Ashby MT. Mechanism of decomposition of the human defense factor hypothiocyanite near physiological pH. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133(49):19911–19921. doi: 10.1021/ja2083152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hoogendoorn H, Piessens JP, Scholtes W, Stoddard LA. Hypothiocyanite ion; the inhibitor formed by the system lactoperoxidase thiocyanate hydrogen peroxide. I. Identification of the inhibiting compound. Caries Research. 1977;11(2):77–84. doi: 10.1159/000260252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bjorck L, Claesson O. Correlation between concentration of hypothiocyanate and antibacterial effect of the lactoperoxidase system against Escherichia coli . Journal of Dairy Science. 1980;63(6):919–922. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nagy P, Alguindigue SS, Ashby MT. Lactoperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation of thiocyanate by hydrogen peroxide: a reinvestigation of hypothiocyanite by nuclear magnetic resonance and optical spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2006;45(41):12610–12616. doi: 10.1021/bi061015y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Adolphe Y, Jacquot M, Linder M, Revol-Junelles A-M, Millière J-B. Optimization of the components concentrations of the lactoperoxidase system by RSM. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2006;100(5):1034–1042. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adamson M, Pruitt KM. Lactoperoxidase-catalyzed inactivation of hexokinase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1981;658(2):238–247. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(81)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mickelson MN. Glucose transport in Streptococcus agalactiae and its inhibition by lactoperoxidase-thiocyanate-hydrogen peroxide. Journal of Bacteriology. 1977;132(2):541–548. doi: 10.1128/jb.132.2.541-548.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thomas EL, Pera KA, Smith KW, Chwang AK. Inhibition of Streptococcus mutans by the lactoperoxidase antimicrobial system. Infection and Immunity. 1983;39(2):767–778. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.2.767-778.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sermon J, Vanoirbeek K, De Spiegeleer P, Van Houdt R, Aertsen A, Michiels CW. Unique stress response to the lactoperoxidase-thiocyanate enzyme system in Escherichia coli . Research in Microbiology. 2005;156(2):225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thomas EL, Aune TM. Susceptibility of Escherichia coli to bactericidal action of lactoperoxidase, peroxide, and iodide or thiocyanate. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1978;13(2):261–265. doi: 10.1128/aac.13.2.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pruitt KM, Tenovuo J, Andrews RW, McKane T. Lactoperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation of thiocyanate: polarographic study of the oxidation products. Biochemistry. 1982;21(3):562–567. doi: 10.1021/bi00532a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huwiler M, Kohler H. Pseudo-catalytic degradation of hydrogen peroxide in the lactoperoxidase/H2O2/iodide system. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1984;141(1):69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huwiler M, Burgi U, Kohler H. Mechanism of enzymatic and non-enzymatic tyrosine iodination. Inhibition by excess hydrogen peroxide and/or iodide. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1985;147(3):469–476. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-2956.1985.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Morrison M, Bayse GS, Michaels AW. Determination of spectral properties of aqueous I2 and I3- and the equilibrium constant. Analytical Biochemistry. 1971;42(1):195–201. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Thomas EL, Aune TM. Peroxidase catalyzed oxidation of protein sulfhydryls mediated by iodine. Biochemistry. 1977;16(16):3581–3586. doi: 10.1021/bi00635a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gottardi W. Iodine and disinfection: theoretical study on mode of action, efficiency, stability, and analytical aspects in the aqueous system. Archiv der Pharmazie. 1999;332(5):151–157. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-4184(19995)332:5<151::aid-ardp151>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Prütz WA, Kissner R, Koppenol WH, Rüegger H. On the irreversible destruction of reduced nicotinamide nucleotides by hypohalous acids. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2000;380(1):181–191. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bichsel Y, Von Gunten U. Hypoiodous acid: kinetics of the buffer-catalyzed disproportionation. Water Research. 2000;34(12):3197–3203. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bichsel Y, von Gunten U. Oxidation of iodide and hypoiodous acid in the disinfection of natural waters. Environmental Science and Technology. 1999;33(22):4040–4045. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Prütz WA, Kissner R, Nauser T, Koppenol WH. On the oxidation of cytochrome c by hypohalous acids. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2001;389(1):110–122. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Virion A, Michot JL, Deme D, Pommier J. NADPH oxidation catalyzed by the peroxidase/H2O2 system. Iodide-mediated oxidation of NADPH to iodinated NADP. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1985;148(2):239–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb08831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Thomas EL, Aune TM. Cofactor role of iodide in peroxidase antimicrobial action against Escherichia coli . Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1978;13(6):1000–1005. doi: 10.1128/aac.13.6.1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Thomas EL, Aune TM. Oxidation of Escherichia coli sulfhydryl components by the peroxidase-hydrogen peroxide-iodide antimicrobial system. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1978;13(6):1006–1010. doi: 10.1128/aac.13.6.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hamon CB, Klebanoff SJ. A peroxidase-mediated, streptococcus mitis-dependent antimicrobial system in saliva. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1973;137(2):438–450. doi: 10.1084/jem.137.2.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ihalin R, Nuutila J, Loimaranta V, Lenander M, Tenovuo J, Lilius E-M. Susceptibility of Fusobacterium nucleatum to killing by peroxidase-iodide-hydrogen peroxide combination in buffer solution and in human whole saliva. Anaerobe. 2003;9(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/S1075-9964(03)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ihalin R, Loimaranta V, Lenander-Lumikari M, Tenovuo J. The effects of different (pseudo)halide substrates on peroxidase-mediated killing of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Journal of Periodontal Research. 1998;33(7):421–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1998.tb02338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bosch EH, van doorne H, de Vries S. The lactoperoxidase system: the influence of iodide and the chemical and antimicrobial stability over the period of about 18 months. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2000;89(2):215–224. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]