Abstract

Objective

To determine if negative social interactions are prospectively associated with hypertension among older adults.

Methods

This is a secondary analysis of data from the 2006 and 2010 waves of the Health and Retirement Study, a survey of community-dwelling older adults (age >50). Total average negative social interactions were assessed at baseline by averaging the frequency of negative interactions across four domains (partner, children, other family, friends). Blood pressure was measured at both waves. Individuals were considered to have hypertension if they reported use of antihypertensive medications, had measured average resting systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, or measured average resting diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg. Analyses excluded those hypertensive at baseline and controlled for demographics, personality, positive social interactions, and baseline health.

Results

Twenty-nine percent of participants developed hypertension over the four-year follow-up. Each one-unit increase in the total average negative social interaction score was associated with a 38% increased odds of developing hypertension. Sex moderated the association between total average negative social interactions and hypertension, with effects observed among women but not men. The association of total average negative interactions and hypertension in women was attributable primarily to interactions with friends, but also to negative interactions with family and partners. Age also moderated the association between total average negative social interactions and hypertension, with effects observed among those ages 51–64, but not those ages ≥65.

Conclusion

In this sample of older adults, negative social interactions were associated with increased hypertension risk in women and the youngest older adults.

Keywords: negative interactions, social conflict, older adults, hypertension, Health and Retirement Study

Numerous studies have evaluated the role of social relationships in cardiovascular outcomes. Most have focused on structural aspects of social ties, such as social network size (number of social ties), social network diversity (number of different types of social ties), or marital status. For example, individuals who are more socially isolated (i.e. have fewer types of social ties) demonstrate higher resting blood pressure (Bland, Krogh, Winkelstein, & Trevisan, 1991), greater cardiovascular mortality risk (Eng, Rimm, Fitzmaurice, & Kawachi, 2002; Kaplan, Salonen, Cohen, Brand, Syme, & Puska, 1988; Kawachi, Colditz, Ascherio, Rimm, Giovannucci, Stampfer, & Willett, 1996), poorer prognosis following myocardial infarction (Ruberman, Weinblatt, Goldberg, & Chaudhary, 1984; Williams, Barefoot, Califf, Haney, Saunders, Pryor et al., 1992) and poorer post-stroke recovery (Colantonio, Kasl, Ostfeld, & Berkman, 1993) than their less isolated counterparts. Several studies also link marital status with cardiovascular mortality, with unmarried persons demonstrating greater mortality risk than married individuals (e.g., De Leon, Appels, Otten, & Schouten, 1992; Malyutina, Bobak, Simonova, Gafarov, Nikitin, & Marmot, 2004).

Fewer studies, however, have focused on qualitative aspects of social relationships. Of these, most have concentrated on the positive aspects. For example, individuals who perceive that they have more social support available from their social networks demonstrate greater survival after myocardial infarction (Berkman, Leo-Summers & Horwitz,1992), lower incidence of coronary heart disease (Orth-Gomer, Rosengren, & Wilhelmsen,1993), lower resting blood pressure (Dressler, Dos Santos, & Viteri, 1986; Uchino, Cacioppo, Malarkey, Glaser, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 1995; Uchino, Uno, & Holt-Lunstad, 1999), and less cardiovascular reactivity to acute stress (Kamarck, Manuck, & Jennings, 1990; Lepore, Allen & Evans, 1993; Uchino & Garvey, 1997).

The effects of negative aspects of social relationships on cardiovascular outcomes, however, have received less attention. By negative social interactions, we mean exchanges or behaviors that involve excessive demands, criticism, disappointment, or other unpleasantness. Here we focus on the role of negative interactions in risk for hypertension. Up until now, support for an association of negative interactions with elevated blood pressure has been limited to a cross-sectional study (de Gaudemaris, Levant, Ehlinger, Hérin, Lepage, Soulat, et al. 2011), a prospective study predicting self-reported hypertension (Wickrama, Lorenz, Wallace, Peiris, Conger, & Elder, 2001) and several experimental studies (e.g., Ewart, Taylor, Kraemer, & Agras, 1991).; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Smith, Uchino, MacKenzie, Hicks, Campo, Reblin et al., 2012). Cross-sectional studies provide evidence for an association between negative interactions and blood pressure, but leave the temporal ordering uncertain. The study of self-reported disease suffers in that, at best, self-report is a weak marker of objectively verified hypertension. Finally, experimental studies are limited in that they do not reflect negative interactions as they are experienced in natural social networks and assess short-term changes in blood pressure that quickly return to baseline.

The purpose of the current study was to examine the effects of negative social interactions on the incidence of hypertension, a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, stroke, and mortality among older adults. Negative social interactions may be especially relevant for older adults, since they have smaller social networks and fewer types of social relationships (Fung, Carstensen, & Lang, 2001), as well as greater (age-related) vulnerability to cardiovascular disease. The study is prospective, uses objective assessments of blood pressure, pursues a range of potential mechanisms that may link negative interactions to hypertension, tests whether the association of negative interactions and onset of hypertension are moderated by sex or by age, and evaluates whether associations are independent of stable individual differences in social personality traits (e.g., extraversion, agreeableness, hostility, neuroticism) or by levels of positive interaction.

Mechanisms Linking Negative Interactions to Hypertension

One possible mechanism through which negative social interactions might be linked to hypertension among older adults is through their effects on psychological well-being. Exposure to relationships with high levels of adverse exchange and conflict may induce psychological distress, which has adverse effects on health (Cohen, 2004). Negative social interactions have been linked to poor psychological outcomes, including greater depressed mood (Ingram, Jones, Fass, Neidig, & Song, 1999; Lincoln, 2008; Schuster, Kessler, & Aseltine, 1990), decreased psychological well-being (Finch, Okun, Barrera, Zautra, & Reich, 1989; Rook, 1984; Rook, 1998), and greater risk of major depressive disorder (Lincoln & Chae, 2012; Wade & Kendler, 2000). Depressed mood (Davidson, Jonas, Dixon, & Markovitz, 2000; Rutledge & Hogan, 2002), well-being (Levenstein, Smith, & Kaplan, 2001; Rutledge & Hogan, 2002) and major depressive disorder (Patten, Williams, Lavorato, Campbell, Eliasziw, & Campbell, 2009) have all been found to predict hypertension.

Negative social interactions may also be linked to increased hypertension risk through their effects on health behaviors. By increasing psychological stress, negative social interactions may promote harmful coping behaviors, including increased tobacco and alcohol use and physical inactivity (Cohen, 2004. Tobacco use (Bowman, Gaziano, Buring, & Sesso, 2007; Halperin, Gaziano, & Sesso, 2008); alcohol consumption (Witteman, Willett, Stampfer, Colditz, Kok, Sacks et al., 1990), and physical inactivity (Paffenbarger, Wing, Hyde, & Jung, 1983) are established risk factors for hypertension.

Effects of Negative Interactions may be Modified by Sex and Age

We were particularly interested in the possibility that negative social interactions might be most harmful for women. Women are thought to be more sensitive to the quality of their social interactions, particularly to negative ones. For example, women have more negative psychological responses to social stress than men (Bakker, Ormel, Verhulst, & Oldehinkel, 2010; Rudolph, Ladd & Dinella, 2007; Shih, Eberhart, Hammen, & Brennan, 2006), are more bothered by negative social exchanges than men (Newsom, Rook, Nishishiba, Sorkin, & Mahan, 2005), demonstrate more cortisol and cardiovascular reactivity to interpersonal laboratory stress (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Stroud, Salovey, & Epel, 2002) and have greater parasympathetic withdrawal in response to interpersonal conflict (Bloor, Uchino, Hicks & Smith,2004; Smith, Uchino, Berg, Florsheim, Pearce, Hawkins et al., 2009; Smith, Cribbet, Nealey-Moore, Uchino, Williams, MacKenzie et al., 2011).

We also expected that age might moderate the association between negative social interactions and hypertension risk. As people age, they decrease the size of their social networks, possibly to devote more time, attention and emotional resources to relationships with close friends and family (Carstensen, 1992; Carstensen, 1993; Carstensen, Gotman, & Levenson, 1995; Fung, Carstensen, & Lang, 2001). Having fewer social relationships may exacerbate the effects of negative interactions, since there would be fewer other network members with whom one may have positive interactions to buffer the effects of aversive ones.

Alternatively, increasing age may provide protection from the deleterious effects of negative interactions. As people get older, they adapt to negative aspects of their relationships and perceive them as less problematic (Akiyama, Antonucci, Takahashi, & Langfahl, 2003; Hansson, R. O., Jones, W. H., & Fletcher, 1990). There are also age differences in the strategies that individuals use for handling interpersonal difficulties that make older adults less vulnerable to the adverse effects of negative interactions. For example, Birditt & Fingerman (2005) found that older adults were more likely to report loyalty strategies (e.g. doing nothing) in response to interpersonal conflict, while younger adults were more likely to report exit strategies (e.g. yelling). Similarly, Diehl and colleagues (1996) observed that older people demonstrated more impulse control, less outward aggression, and more positive appraisals of conflict situations than younger people.

Alternative Explanations

We include a group of standard control variables because of the possibility that they may cause or contribute to both the occurrence of negative interactions and risk for hypertension. These include demographic characteristics (age, sex, marital status, race/ethnicity, education, employment status), and markers of baseline health (history of chronic illnesses, baseline systolic/diastolic blood pressure). We also consider the possibility that associations between negative interactions and health may be attributable to personality characteristics that contribute to both the quality of interactions and to health outcomes. For example, low extraversion and agreeableness and high hostility and neuroticism have been associated with both higher levels of conflictive social relationships (Berry, Willingham, and Thayer, 2000; Brondolo, Rieppi, Erickson, Bagiella, Shapiro, McKinley, & Sloan, 2003; Lincoln, 2008) and dysregulated cardiovascular function (extraversion: Miller, Cohen, Rabin, Skoner & Doyle, 1999; Shipley, Weiss, Der, Taylor & Deary, 2007; agreeableness: Miller, Cohen, Rabin, Skoner, & Doyle, 1999; hostility: Suls & Bunde, 2005; Steptoe & Chida, 2009; Tindle, Chang, Kuller, Manson, Robinson, Rosal et al., 2009; neuroticism: Shipley, Weiss, Der, Taylor & Deary, 2007).

Finally, those with higher levels of negative interactions are likely to also have lower levels of positive ones (e.g., Okun & Keith, 1998). This inverse correlation leaves the possibility that what appears to be an association with more negative experiences may in fact be attributable to having fewer positive ones. Thus, we conduct additional analyses to evaluate the association between negative social interactions and hypertension controlling for positive interactions.

Methods

Participants and Design

This study is a secondary analysis of data from the 2006 and 2010 waves of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a large-scale longitudinal study of community-dwelling older adults (aged > 50 years). The HRS sampling methods and study design have been previously documented (Heeringa, & Connor, 1995; Juster & Suzman, 1995). Briefly, the HRS uses a national area probability sample of U.S. households; the sample includes individuals aged >50 years and (when applicable) their partners. A total of 18,469 individuals provided data at baseline (2006 wave). Fifty percent of this sample was randomly selected to participate in enhanced face-to-face interviews including questions assessing demographics, health status, health behaviors, negative interactions and psychological well-being. The interview period also included a blood pressure assessment. Of the participants invited to be interviewed, 7,144 provided interview and blood pressure data at baseline (2006 wave). Of these 6,817 also provided blood pressure data at the 4-year follow-up. The mean follow-up time was 50.18 months (SD 4.06; range 39–61 months).

From the sample with blood pressure data at both assessments, we excluded all participants who were hypertensive at baseline, which included those using antihypertensive medications (n=3,778) and those with baseline blood pressure readings in the hypertensive range (average resting systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or average resting diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg; n=1023). Then, we excluded 371 individuals who were missing data on at least one of our control variables and 1 individual who provided incomplete negative interaction data. Finally, we excluded 142 individuals who died during the follow-up period. Our final sample included 1502 participants (Table 1) who were 84.8% Non-Hispanic White, 6.8% Hispanic, 6.5% Non-Hispanic Black, and 1.9% other racial/ethnic backgrounds. Participants were 59.8% female and ages 51–91 years at baseline (mean age 64.28; SD 8.95). When comparing our sample to those who provided blood pressure data during the 2006 wave but were excluded, our sample tended to be younger, employed, more educated, more likely to be nonsmokers, and married (Table 1). These variables are all well-established associates of hypertension, the screening variable responsible for over 90% of those not meeting criteria for inclusion in our analysis. Our sample included a mixture of individuals (80.6%) and of couples who both participated in the study (19.4%).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the study sample

| Variable | Study Sample (n=1502) |

Excluded Participants with Blood Pressure Data at Baseline (n=5930) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years (SD) | 64.28 (8.95) | 68.07 (10.99) | <0.0001 |

| Sex | |||

| Female, n (%) | 899(59.9) | 3448 (58.1) | 0.23 |

| Male, n (%) | 603 (40.1) | 2482 (41.9) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White, n (%) | 1274 (84.8) | 4394(74.4) | <0.0001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black, n (%) | 97 (6.5) | 860(14.6) | <0.0001 |

| Hi s panic, n (%) | 102 (6.8) | 507 (8.6) | 0.02 |

| Non-Hispanic Other, n (%) | 29(1.9) | 134 (2.3) | 0.43 |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school, n (%) | 168 (11.2) | 1243 (21.0) | <0.0001 |

| GED, n (%) | 69 (4.6) | 282 (4.8) | 0.78 |

| High school graduate, n (%) | 442 (29.4) | 1871(31.6) | 0.10 |

| Some college, n (%) | 378 (25.2) | 1355 (22.9) | 0.06 |

| College and above (n, %) | 445(29.6) | 1168 (19.7) | <0.0001 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married, n (%) | 1072 (71.4) | 3749 (63.2) | <0.0001 |

| Annulled, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2(0.0) | 0.48 |

| Never married, n (%) | 52 (3.5) | 193(3.3) | 0.70 |

| Separated, n (%) | 17 (1.1) | 119(2.0) | 0.02 |

| Divorced, n (%) | 171 (11.4) | 629 (10.6) | 0.39 |

| Widowed, n (%) | 190 (12.6) | 1224(20.7) | <0.0001 |

| Employment Status | |||

| Employed, n (%) | 771 (51.3) | 2042(34.4) | <0.0001 |

| Not Employed, n (%) | 731 (48.7) | 3887(65.6) | |

| Smoking Status | |||

| Non-Smoker | 701 (46.8) | 2530 (42.9) | 0.02 |

| Former Smoker | 595 (39.7) | 2550 (43.2) | |

| Current Smoker | 201 (13.4) | 820(13.9) | |

| Average Baseline Systolic Blood Pressure, Mean (SD) | 118.34 (11.81) | 134.81 (21.30) | <0.0001 |

| Average Baseline Diastolic Blood Pressure, Mean (SD) | 74.26 (7.98) | 80.99 (12.26) | <0.0001 |

Negative Social Interactions

Negative social interactions were assessed in the self-administered psychosocial questionnaire across four domains: relationships with spouse/partner, children, other family, and friends (adapted from Krause, 1995). Four questions were used to evaluate negative interactions in each domain: 1) How often do they make too many demands on you?; 2) How much do they criticize you?; 3) How much do they let you down when you are counting on them?; and 4) How much do they get on your nerves? Responses for each question were coded on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot). We calculated mean scores for each of the 4 domains [friends (n=1437; mean=1.43; SD 0.48; range 1–4), partner (n=1141; mean=1.98; SD 0.66; range 1–4), children (n=1360; mean=1.75; SD 0.63; range 1–4), and other family (n=1441; mean=1.62; SD 0.62; range 1–4)] by averaging across item scores within each domain. A domain score was set to missing if more than two items had missing values in accordance with the scoring guidelines established by the HRS coordinating center (Clarke, Fisher, House, & Weir, 2008). To create a total average negative interaction score (range from 1 to 4), we averaged the scores across the four domains. Total scores were calculated using only scored domains, and only for those with a score for at least one of the 4 domains. This method for calculating an average score for this questionnaire has been commonly used in studies of negative social interactions and health (Friedman, Karlamangla, Almeida, & Seeman, 2012; Newsom, Mahan, Rook, & Krause, 2008; Seeman, Berkman, Blazer, & Rowe, 1994; Tun, Miller-Martinez, Lachman, & Seeman, 2013) and reflects the average level of negativity across interaction domains.

Outcome Measure

Blood pressure assessments were performed in both 2006 and 2010 by study staff who underwent repeated training (Crimmins, Guyer, Langa, Ofstedal, Wallace, & Weir, 2008). Resting blood pressure values were based on the average of the 3 blood pressure measurements, 45 seconds apart, taken on the respondent’s left arm using an automated blood pressure monitor (Crimmins et al., 2008). Hypertension was defined as either self-reported use of antihypertensive medications, or an average resting systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, or average resting diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg (Chobanian, Bakris, Black, Cushman, Green, Izzo et al., 2003).

Control Variables

Demographics, baseline blood pressure and health, personality variables and positive social interactions were included as “standard” controls in all analyses. Hours of volunteering (related to hypertension in previous analysis of this data set [Sneed & Cohen, 2013]), also assessed at baseline, were added in separate analyses. All categorical breakdowns were based on the original categories from the HRS dataset and were dummy coded in the analyses.

Baseline blood pressure assessments are described in the section on outcome variables.

Demographic controls included age (continuous), sex (male/female), self-reported race (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Non-Hispanic Other), education (less than high school, high school diploma, General Equivalency Diploma [GED], some college, college and above), marital status (married, annulled, never married, divorced, separated, widowed), and employment status (employed/not employed).

Self-reported history of illness included 7 separate dummy coded variables evaluating history of diabetes (yes/no), cancer (yes/no), heart problems (yes/no), stroke (yes/no), memory problems (yes/no), arthritis (yes/no) and lung problems (yes/no).

Personality characteristics included cynical hostility, neuroticism, extraversion, and agreeableness. All were continuous variables assessed at baseline via self-report questionnaire. Cynical hostility was measured by 5 items from the Cook-Medley Hostility Inventory (Cook & Medley, 1954) as per HRS protocol. Participants rated the extent to which they agreed with each item on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). An index of cynical hostility was created by averaging the scores across all items. Neuroticism, extraversion, and agreeableness were assessed using 16 adjectives (6 for neuroticism, 5 for extraversion, 5 for agreeableness) from the Midlife Development Inventory (MIDI) personality scales (Lachman & Weaver, 1997). Participants rated the extent to which each adjective described them on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot). Scores for each of these personality characteristics were created by averaging the scores across the corresponding items.

Positive social interactions were assessed as social support and measured in each of the 4 social domains (partner, children, other family, friends). Within each domain, participants answered the following 3 items on a scale from 1 (never) to 4 (a lot): 1) How much do they really understand the way you feel about things?; 2) How much can you rely on them if you have a serious problem?; and 3) How much can you open up to them if you need to talk about your worries? We created a total average positive social interaction score by averaging responses to these items across domains. Total scores were calculated using only scored domains, and only for those with a score for at least one of the 4 domains.

Finally, we assessed self-reported hours of volunteer work in the 12 months prior to baseline (none, 1 to 49 hours, 50 to 99 hours, 100 to 199 hours, 200 or more). The categories for volunteerism were pre-established by HRS study staff.

Potential Mediating Variables

The following variables were assessed at baseline and follow-up and tested as potential mediating variables: alcohol use, tobacco use, physical activity, body mass index, and 9 measures of psychological well-being.

Alcohol use (Witteman et al., 1990), tobacco use (Bowman et al., 2007; Halperin et al., 2008), and physical activity (Paffenbarger et al., 1983) are all typically associated with blood pressure. The measures used for evaluating these variables are based on standard instruments typically used in large-scale epidemiological studies. Alcohol use was based on participant responses to the following 3 questions: 1) Do you ever drink any alcoholic beverages such as beer, wine, or liquor?; 2) In the last three months, on average, how many days per week have you had any alcohol to drink?; and 3) In the last three months, on the days you drink, about how many drinks do you have? The average number of drinks per week for each participant was determined by multiplying average number of days per week drinking by average number of drinks per day. Similarly, tobacco use was based on participant responses to the following 2 questions: 1) Do you smoke cigarettes now?; and 2) About how many cigarettes or packs do you usually smoke in a day now? Responses were used to calculate the average number of cigarettes per day for each participant, with each pack of cigarettes corresponding to 20 cigarettes.

Physical activity was assessed by questions regarding frequency of participation in vigorous or moderate sports or activities using these categories: more than once a week, once a week, one to three times a month, or hardly ever/never. Vigorous activities included the following examples: running, jogging, swimming, cycling, aerobics, a gym workout, tennis, or digging with a spade or shovel. Moderate activities included the following examples: gardening, cleaning the car, walking at a moderate pace, dancing, or floor or stretching exercises. We used a summary physical activity variable previously used in the English Longitudinal Study of Aging (McMunn, Hyde, Janevic, & Kumari, 2003) to organize vigorous and moderate physical activity into 5 ordinal categories ranging from 0 (sedentary) to 4 (active).

We also included body mass index as a potential mediator because it is a marker of adiposity (Keys, Fidanza, Karvonen, Kimura, & Taylor, 1972) and a risk factor for adverse cardiovascular outcomes (Wilson, D'Agostino, Sullivan, Parise, & Kannel, 2002). We hypothesized that negative social interactions may cause changes in health behaviors (e.g. poor diet, physical inactivity) that might lead to greater adiposity. Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Standard scales representing nine individual psychological constructs (Table 2) were used to measure psychological well-being at baseline and four-year follow-up: personal control, purpose in life, life satisfaction, positive affect, optimism, loneliness, hopelessness, negative affect, and pessimism. Scores on each measure were determined by averaging the scores across the individual items. Scores were set to missing if more than 50% of individual items for each respective measure had missing values.

Table 2.

Measures Used to Evaluate Psychological Well-Being in the 2006 (baseline) and 2010 Waves of the Health and Retirement Study.

| Construct | Measure |

|---|---|

| Hopelessness | Beck Hopelessness Scale (2 items; Beck, Weissman, Lester, & Trexler, 1974) Selected hopelessness items (2 items; Everson, Kaplan, Goldberg, Salonen, & Salonen, 1997) |

| Life Satisfaction | Satisfaction with Life Scale (5 items; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) |

| Loneliness |

2006:UCLA Loneliness Scale (3 items; Hughes, Waite, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, 2004) 2010:UCLA Loneliness Scale (11 items; Hughes, Waite, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, 2004) |

| Negative Affect |

2006:Negative Affect Scale from the Midlife in the United States study (MIDUS; 6 items; Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998) 2010: Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form (PANAS-X; 12 items; Watson & Clark, 1994) |

| Optimism | Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R; 3 items; Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994) |

| Personal Control | Sense of Control Scales of the Midlife Developmental Inventory (5 items; Lachman & Weaver, 1998a; Lachman & Weaver, 1998b) |

| Pessimism | Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R; 3 items; Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994) |

| Positive Affect | Positive Affect Scale from the Midlife in the United States study (MIDUS; 6 items; Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998) |

| Purpose in Life | Purpose Scale of Ryff Measures of Psychological Well-Being (7 items; Ryff 1995; Keyes, Shmotkin, & Ryff, 2002) |

Statistical Analyses

Our primary analytic strategy focused on evaluating the association between total average negative social interactions and hypertension risk and on determining the extent to which age and sex modified the association between negative social interactions and hypertension. A secondary objective was to identify factors that might mediate the association between negative social interactions and hypertension. Finally, we performed additional exploratory analyses based on our initial primary analyses in order to better understand associations between total average negative social interactions and hypertension risk.

Logistic regression was used to evaluate the relationship between total average negative social interactions (across all 4 domains) and hypertension. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to estimate the risk for each one-unit of increase in the total average negative interaction score. We also calculated domain-specific odds ratios and 95% CIs to determine if effects were driven by any particular domain. All odds ratios reflect a change in the likelihood of developing hypertension for every one-unit increase in the negative interactions scale (range 1 to 4).

To evaluate the extent to which the potential mediating variables linked negative social interactions with hypertension, we used the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013), a computational tool for path analysis-based mediation analysis with dichotomous outcomes. This analytical method uses a logistic regression-based approach to estimate direct and indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Bootstrap methods are used to draw inferences about indirect effects. We standardized the average scores for all of the psychological variables, and tested for mediation in three ways: 1) using baseline values of each individual mediator, 2) using values of each individual mediator at follow-up, and 3) evaluating residual change (entering both baseline and follow-up) in each potential mediator from baseline to follow-up. With each approach, the potential mediators were entered into the model both individually and simultaneously. Mediation was supported if addition of these covariates substantially reduced the association of negative social interactions with hypertension (Sobel, 1982).

To determine if either age or sex moderate the associations observed between negative social interactions (across all 4 domains and within each domain) and hypertension, we used first-order cross product terms for total average negative social interactions and these proposed modifier variables. Interaction terms were entered into individual regression equations with the corresponding main effects and control variables.

Finally, since our sample included a mixture of individuals and couples, it is possible that interdependence of data for partners might bias the results. To address this, we reanalyzed our data including all individual participants in addition to a randomly selected member of each couple (selected using a random sequence generator). This resulted in a reduction of power (decreased sample size from 1502 to 1356) but eliminated the possibility of correlated partner responses. We then repeated the analyses using the other member of each couple in the sample.

Results

Control Variables and Hypertension

Of the 1502 study participants included in our analyses, 445 (29.6%) were hypertensive at follow-up. When entered into the logistic regression model simultaneously, the following standard control variables were related to increased hypertension risk: older age: (B=.03, p=<.001), Hispanic ethnicity (compared to Non-Hispanic Whites; B=0.79; p=.001), self-reported history of diabetes (B=0.52; p=.008), greater average baseline systolic (B=0.04; p<.001) and diastolic blood pressure (B=0.03; p=.003) and higher levels of agreeableness (B=0.38; p=.03). Having less than a high school education was associated with decreased hypertension risk (B=−0.75; p=0.04). The other covariates were not related to hypertension risk.

Negative Interactions and Hypertension

The mean total average negative interaction score for study participants was 1.67 (SD=0.45; Table 3). In a regression including the standard covariates, total average negative interactions across the 4 domains predicted greater hypertension risk (Table 4; OR: 1.38; 95% CI: 1.00–1.89). Given that hours of volunteer work were related to hypertension risk in a previous analysis of this data set (Sneed & Cohen, 2013), we performed additional analyses simultaneously entering volunteerism and total average negative social interactions into a regression model, adjusting for our standard controls. Here, total average negative social interactions were independently associated with greater hypertension risk (OR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.01–1.91). Further, even after adjusting for negative interactions, those who volunteered at least 200 hours per year were less likely to develop hypertension than nonvolunteers (OR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.36–0.89).

Table 3.

Logistic Regression for Association of Negative Social Interactions with Hypertension Across Domains and Within Each Social Domain

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Total Average Negative Social Interactions (Average of 4 Domains) | 1.38 (1.00–1.89) | ||||

| Negative Interactions with Partner | 1.15 (0.90–1.48) | ||||

| Negative Interactions With Children | 1.01 (0.80–1.28) | ||||

| Negative Interactions With Children with Other Family | 1.33 (1.07–1.65) | ||||

| Negative Interactions with Friends | 1.36 (1.04–1.78) |

All models adjust for age, race/ethnicity, sex, employment status, marital status, education, baseline systolic blood pressure, baseline diastolic blood pressure, extraversion, agreeableness, cynical hostility, neuroticism and self-reported history of diabetes, cancer, heart problems, arthritis, memory problems, lung problems, or stroke.

We were also interested in whether the association between negative interactions and hypertension was driven by negative interactions in any particular social domain. Domain-specific analyses demonstrated that negative interactions were associated with increased hypertension risk when examining relationships with one’s friends (Table 5; OR 1.36; 95% CI: 1.04–1.78), and family other than children or partner (Table 5; OR: 1.33; 95% CI: 1.07–1.65). There were no main effects of negative interactions with children (Table 5; 1.01; 95% CI: 0.80–1.28) or partner (Table 5; OR 1.15; 95% CI: 0.90–1.48) on hypertension.

Sex and Age as Modifiers

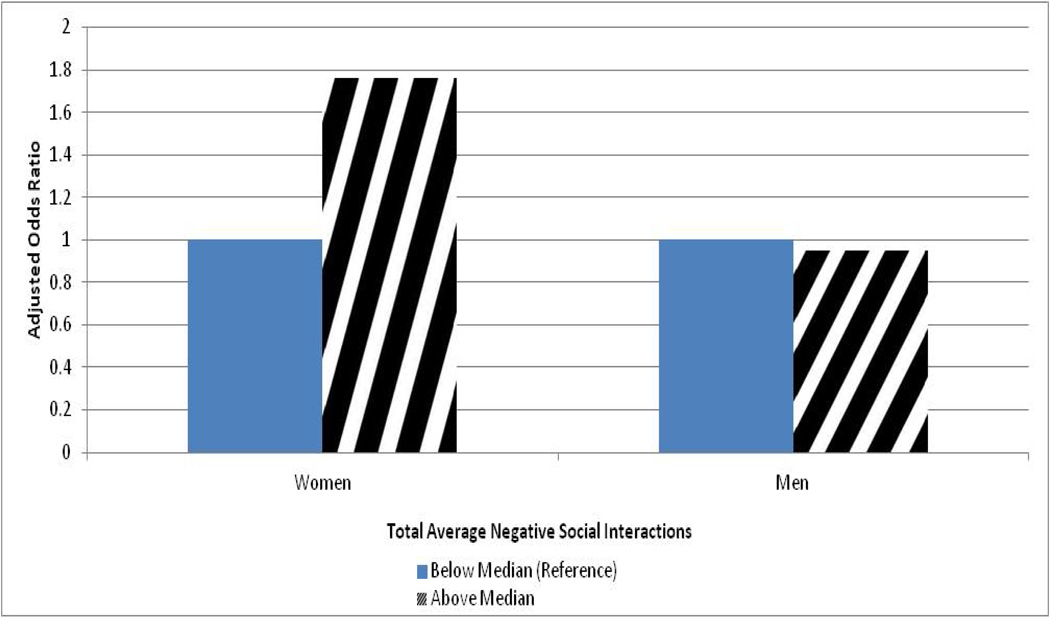

We also evaluated how sex and age might modify the association between total average negative interactions and hypertension risk. We found that sex moderated the association between the total average negative interaction score and hypertension (Figure 1; B=0.7; p=.02). The relationship between the total average negative interaction score and hypertension was not observed among men (OR: 0.88; 95% CI=0.50–1.53), but was pronounced among women (OR: 1.87; 95% CI: 1.25–2.79). In domain-specific analyses, we observed that sex moderated the association between negative interactions with friends and hypertension (B=0.93; p<.001). Among men, there was no association between negative friend interactions and hypertension (OR: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.43–1.12). Among women, however, negative interactions with friends predicted increased hypertension risk (OR: 2.15; 95% CI: 1.51–3.08). Similar, but nonsignificant patterns were found for the interactions of sex and negative interactions with partner (B=0.31; p=0.15) and family (0.37; p=.07), but not children (B=.11; p=.61).

Figure 1.

Association of Total Average Negative Social Interaction Scores With Hypertension By Sex.

Age also moderated the association between total average negative social interactions and hypertension (B=−0.03; p=.02). There was no association between total average negative social interactions and hypertension among participants aged ≥ 65 years (OR: 1.16; 95% CI: 0.72–1.86). Among those ages 51–64, however, total average negative social interactions were associated with increased hypertension risk (OR: 1.67; 95% CI: 1.06–2.62). In domain-specific analyses, we observed that age moderated the association between negative partner interactions and hypertension (B=−0.03; p<.01). Further analyses suggest that the effects of negative partner interactions were most potent for the youngest participants. Similar, but nonsignificant patterns were found for the interactions of sex and negative interactions with children (B=−0.02; p=0.08) and family (−0.12; p=.18), but not friends (B=−.006; p=.71).

Finally, we tested the three way interaction of age, sex, and negative interactions by entering it into a model with all the main effects and 2-way interactions. There was no three-way interaction of these variables in predicting hypertension (B=.009; p=0.31).

We considered the possibility that blood pressure measurements from study participants might be artificially inflated due to the white coat effect (i.e. spuriously high blood pressure readings in response to the clinical environment; Mancia, Grassi, Pomidossi, Gregorini, Bertinieri, Parati et al., 1983; Mancia, Parati, Pomidossi, Grassi, Casadei, & Zanchetti, 1987). To account for this, we repeated our main analyses by dropping the first blood pressure reading and averaging the last 2 readings. In doing so, there is no longer a main effect of total average negative interactions (OR: 1.15; 95% CI: 0.83–1.59) or friend interactions (OR 0.81; 95% CI 0.61–1.06)..The remaining results were the same for negative family interactions (OR 0.80; 95% 0.64–1.00), and there was still no association between negative partner (OR 0.87; 95% CI 0.68–1.11) or child (OR 1.07; 95% CI 0.85–1.36) interactions. The effects of negative social interactions were still similarly modified by sex (B=0.66; p=0.03) and age (B=−0.03; p=0.03).

Accounting for Partners in Same Analysis

To address the issue of interdependence of date for partners, we reanalyzed our data including all individual participants in addition to a randomly selected member of each couple. We observed virtually identical results with total average negative interactions associated with increased hypertension risk (OR: 1.42; 95% CI: 1.02–1.98) and statistical interactions of negative social interactions by sex (B=0.72; p=.02) and age (B=−.03; p=.04). As in the analysis of the entire sample, total average negative social interactions were associated with hypertension risk among women (OR: 1.93 ; 95% CI: 1.27–2.94) but not men (OR: 0.90; 95% CI: 0.49–1.63) and among those ages 51–64 (OR: 1.76; 95% CI: 1.09–2.84) but not those 65 and older (1.11; 95% CI: 0.68–1.81). We repeated the analyses using the other member of each couple in the sample and again found that total average negative interactions predicted greater risk for hypertension (OR: 1.42; 95% CI: 1.02–1.96) and that age (B=−.04; p=.02) and sex (B=0.71; p=0.02) interacted with negative interactions in the same manner as described above. Total average negative social interactions were associated with increased hypertension risk among women (OR: 1.86; 95% CI: 1.23–2.81) but not men (OR: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.52–1.66) and among those ages 51–64 (OR: 1.64; 95% CI: 1.03–2.61) but not those 65 and older (OR: 1.22; 95% CI: 0.75–1.98).

Mediation

Finally, we explored factors that might mediate the association between negative interactions and hypertension risk, conducting separate mediation analyses for the entire sample, for women and for participants ages 51–64. There were no indirect effects of negative social interactions on hypertension through any of our potential mediators (body mass index, alcohol use, tobacco use, physical activity, or the 9 individual measures of psychological well-being).

Discussion

We found that total average negative social interaction scores were associated with increased hypertension risk in a sample of community-dwelling adults aged >50 years. Specifically, each one-unit increase in an individual’s score resulted in a 38% increased odds of hypertension over a 4-year follow-up. This association persisted even after controlling for demographics, personality variables, and positive social interactions. Importantly, this association was independent of volunteerism, which had been associated with decreased hypertension risk in a previous analysis of this dataset (Sneed & Cohen, 2013). Both negative social interactions and volunteerism exerted distinct, independent effects on hypertension risk when evaluated simultaneously. Our findings are consistent with literature linking acute negative social interactions to short-term elevated blood pressure responses in younger adults (Ewart et al., 1991; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Smith et al., 2012) and suggest that negative interactions may contribute to long-term alterations in blood pressure regulation.

Total average negative interaction scores predicted hypertension risk among women, but not among men. This association was driven primarily by women’s negative interactions with friends, and to a lesser degree, partners and family. There are several possible reasons why women but not men were more impacted by negative relationships. There is evidence that women care more about and pay more attention to their social interactions (Coriell & Cohen, 2005) and have greater expectations of their social relationships than men. In a study of older adults ages 50–97 years, Felmlee & Muraco (2009) observed that women demonstrated greater disapproval of behavior that violated friendship rules, such as betrayal of confidence, failure to confide in them, or not standing up for them when someone criticized them. These greater expectations may lead to greater distress among women when such relationship expectations are not met. Further, women report more intimacy, closeness and self-disclosure in their social relationships than men (Sheets & Lugar, 2006; Singleton & Vacca, 2007). This greater intimacy may intensify reactions to conflict when it arises (Crick, 1995; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). Finally, women and men often have different strategies for responding to and resolving conflict. In laboratory marital conflict discussions, for example, women are more likely to confront the conflict directly, whereas men tend to withdraw (Carstensen, Gottman & Levenson, 1995). This difference in conflict management style may also have implications for cardiovascular response to aversive social situations.

We also found that age moderated the association between negative social interactions and hypertension risk, with effects observed among younger (approximately 51 to 64 years) but not older (≥65 years) participants. These findings suggest that negative social interactions are particularly potent for the “sandwiched generation”, those within the later years of midlife who typically bear responsibility for both their own children as well as aging parents. Negative social interactions may only exacerbate the adverse effects of existing life stressors among individuals in this age group. Our observation that negative social interactions were not related to hypertension risk among the oldest participants (≥65 years) is consistent with evidence that, as people get older, they may adapt to negative aspects of their relationships and perceive them as less problematic (Akiyama et al., 2003). It is also possible that the oldest adults have more adaptive strategies for handling interpersonal difficulties that render such interactions less potent with respect to hypertension risk.

We also found no main or interaction effects linking negative interactions with children to hypertension. This is consistent with recent evidence from the MacArthur Study on Successful Aging where regular interactions with spouse and other family members were associated with pulmonary health in older adults, but interactions with children were not (Crittenden, Pressman, Cohen, Smith, & Seeman, unpublished manuscript). It is possible that individuals in this age group have lower expectations of their children than they do of other members of their social networks. Studies have shown that adult children are willing to provide more support to their parents than their parents expected (Hamon & Blieszner, 1990; Silverstein, Chen, & Heller, 1996). Parents may also have schemas about the nature of the parent/child relationship that lead them to expect more difficult relationships with their children. They may also have greater insight into their children’s behaviors and use this to justify negative interactions in ways that reduce psychological distress. Finally, parents may simply have less face-to-face contact (or contact of any kind) with their children than with other members of their social networks, thus limiting the potential impact of any negative social interactions.

We found no psychological or behavioral explanations for the association between negative interactions and hypertension risk. It is possible that our findings may be explained by factors that were not measured in this study. For example, negative social interactions may increase maladaptive health behaviors linked to hypertension risk, such as poor sleep quality (Gangwisch, Heymsfield, Boden-Albala, Buijs, Kreier, Pickering et al., 2006) or unhealthy nutritional habits (Reddy & Katan, 2004). Our measure of physical activity also may not have been ideal for evaluating activity levels among the participants. Self-report questionnaires gauging moderate and vigorous activity may not be adequate measures of physical activity among elderly individuals, since most physical activity performed by older adults involves walking in the context of regular daily activities rather than a formal exercise regimen (Walsh, Rogot, Pressman, Cauley, & Browner, 2004). More sensitive, objective measures of physical activity (e.g. accelerometry) might be more useful in this population. There may also be physiological explanations for our findings. For example, acute conflictive social interactions are associated with short-term increases in blood pressure, greater parasympathetic withdrawal, activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis, and increased production of inflammatory cytokines (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001). Sustained negative social interactions may cause long-term wear and tear in these physiological systems (allostatic load), leading to an inability to effectively regulate blood pressure (McEwen, 1998). Future research should explore how additional behavioral factors (e.g. sleep habits, physical activity, diet) and physiological indicators (e.g increased sympathetic nervous system activity) may mediate the association between negative social interactions and hypertension.

This study is not without limitations. Although the study sample is drawn from a larger, nationally representative sample of older adults, the individuals who met the inclusion criteria for this study were, in some ways, demographically different from the larger HRS sample. Consequently, we do not employ the weighting and sampling design adjustments often used to analyze HRS data (Heeringa & Connor, 1995). Thus, these findings should not be interpreted as being representative of the U.S. population of older adults. Our findings, however, are consistent with other work linking negative social interactions to adverse health outcomes (De Vogli, Chandola, & Marmot, 2007; Krause, 2005). Further, the main effects of negative social interactions were no longer significant when we reanalyzed the data by dropping the first blood pressure reading. These analyses, however, reinforce the importance of negative social interactions with family (irrespective of participant sex) and suggest that negative interactions with friends mostly matter for women.

The negative interaction questionnaire assesses four social domains (partner, friends, children, other family members) that are all traditionally considered to be close relationships. People maintain fewer peripheral relationships as they grow older (e.g., Fung, Carstensen & Lang, 2001), devoting more attention to relationships with close friends and family. Hence, the measure used here reflects the largest and closest components of the social network in this age group, making negative social interactions in these domains particularly salient.

This study is the first to prospectively evaluate negative social interactions as a predictor of the onset of hypertension. The negative interactions reflect experiences in natural social networks. The work includes controls for multiple alternative explanations for the results, including the first test of the role of stable individual differences that could contribute to both the occurrence of negative interactions and the onset of hypertension. It is also the first study of negative interactions and hypertension to control for the potential overlap with positive social interactions. Finally, it suggests that a range of predicted mediators do not play a role in this association for this older sample.

Our sample included individuals ages 51–91 at baseline (mean age 64.28; SD 8.95). Hypertension risk increases with age, with rates reaching 70% by age 65 (McDonald, Hertz, Unger & Lustik, 2009). Thus, individuals from our sample were particularly at risk for developing hypertension during the follow-up period. In fact, 29% of the sample developed hypertension over the four-year follow-up. Given that hypertension is a major risk factor for diseases of aging, including cardiovascular disease (the number one cause of death in the United States), stroke, and mortality, the association of negative social interactions with increased hypertension risk has important public health significance. Further, interpersonal conflict is one of the most frequently reported types of chronic stress; thus, it is particularly important to understand the role of interpersonal strain in health outcomes such as hypertension.

Acknowledgments

Ms. Sneed’s participation in this research was partly supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (AT006694).

These analyses use data from the Health and Retirement Study, (HRS 2006 Core [Final V2.0)]; HRS 2010 Core [Final V1.0]) sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and conducted by the University of Michigan.

References

- Akiyama H, Antonucci T, Takahashi K, Langfahl ES. Negative interactions in close relationships across the life span. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2003;58:P70–P79. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.2.p70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker MP, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Oldehinkel AJ. Peer stressors and gender differences in adolescents' mental health: the TRAILS study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42:861–865. doi: 10.1037/h0037562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry DS, Willingham JK, Thayer CA. Affect and personality as predictors of conflict and closeness in young adults' friendships. Journal of Research in Personality. 2000;34:84–107. [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Fingerman KL. Do we get better at picking our battles? Age group differences in descriptions of behavioral reactions to interpersonal tensions. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60:P121–P128. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.3.p121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloor LE, Uchino BN, Hicks A, Smith TW. Social relationships and physiological function: The effects of recalling social relationships on cardiovascular reactivity. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;28:29–38. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2801_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman TS, Gaziano JM, Buring JE, Sesso HD. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and risk of incident hypertension in women. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;50:2085–2092. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Rieppi R, Erickson SA, Bagiella E, Shapiro PA, McKinley P, Sloan RP. Hostility, interpersonal interactions, and ambulatory blood pressure. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65:1003–1011. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000097329.53585.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7:331–338. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. Motivation for social contact across the life span: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. In: Jacobs JE, editor. Nebraska symposium on motivation: 1992, Developmental Perspectives on Motivation. Vol. 40. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1993. pp. 209–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Gottman JM, Levenson RW. Emotional behavior in long-term marriage. Psychology and Aging. 1995;10:140–149. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Rocella EJ. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke P, Fisher G, House J, Weir D. Guide to content of the HRS Psychosocial Leave-Behind Participant Lifestyle Questionnaires: 2004 & 2006. University of Michigan. Survey Research Center. 2008 Available at http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/userg/HRS2006LBQscale.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Social relationships and health. American Psychologist. 2004;59:676–684. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook WW, Medley DM. Proposed hostility and pharisaic-virtue scales for the MMPI. The Journal of Applied Psychology. 1954;38:414–418. [Google Scholar]

- Coriell M, Cohen S. Concordance in the face of a stressful event: When do members of a dyad agree that one person supported the other? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:289–299. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR. Relational aggression: The role of intent attributions, feelings of distress, and provocation type. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66:710–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM, Guyer H, Langa KM, Ofstedal MB, Wallace RB, Weir DR. Documentation of Physical Measures, Anthropometrics and Blood Pressure in the Health and Retirement Study. 2008 Retrieved from http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/userg/dr-011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden CN, Pressman SD, Cohen S, Smith BW, Seeman TE. Social Integration, Specific Social Roles and Pulmonary Function in the Elderly. doi: 10.1037/hea0000029. (Unpublished Manuscript) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson K, Jonas BS, Dixon KE, Markovitz JH. Do depression symptoms predict early hypertension incidence in young adults in the CARDIA study? Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160:1495–1500. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vogli R, Chandola T, Marmot MG. Negative aspects of close relationships and heart disease. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:1951–1957. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.18.1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Coyle N, Labouvie-Vief G. Age and sex differences in strategies of coping and defense across the life span. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11:127–139. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson SA, Kaplan GA, Goldberg DE, Salonen R, Salonen JT. Hopelessness and 4-year progression of carotid atherosclerosis: The Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 1997;17:1490–1495. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.8.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart CK, Taylor CB, Kraemer HC, Agras WS. High blood pressure and marital discord: not being nasty matters more than being nice. Health Psychology. 1991;10:155–163. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.3.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felmlee D, Muraco A. Gender and friendship norms among older adults. Research on Aging. 2009;31:318–344. doi: 10.1177/0164027508330719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch JF, Okun MA, Barrera M, Zautra AJ, Reich JW. Positive and negative social ties among older adults: Measurement models and the prediction of psychological distress and well-being. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1989;17:585–605. doi: 10.1007/BF00922637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman EM, Karlamangla AS, Almeida DM, Seeman TE. Social strain and cortisol regulation in midlife in the US. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung HH, Carstensen LL, Lang FR. Age-related patterns in social networks among European Americans and African Americans: Implications for socioemotional selectivity across the life span. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2001;52:185–206. doi: 10.2190/1ABL-9BE5-M0X2-LR9V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, Buijs RM, Kreier F, Pickering TG, Malaspina D. Short Sleep Duration as a Risk Factor for Hypertension Analyses of the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hypertension. 2006;47:833–839. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000217362.34748.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin RO, Gaziano JM, Sesso HD. Smoking and the risk of incident hypertension in middle-aged and older men. American Journal of Hypertension. 2008;21:148–152. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2007.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamon RR, Blieszner R. Filial responsibility expectations among adult child–older parent pairs. Journal of Gerontology. 1990;45:P110–P112. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.3.p110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson RO, Jones WH, Fletcher WL. Troubled relationships in later life: Implications for support. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1990;7:451–463. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SG, Connor J. Technical Description of the Health and Retirement Study Sample Design. 1995 Retrieved from http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/userg/HRSSAMP.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging. 2004:655–672. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram KM, Jones DA, Fass RJ, Neidig JL, Song YS. Social support and unsupportive social interactions: Their association with depression among people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 1999;11:313–329. doi: 10.1080/09540129947947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juster FT, Suzman R. An overview of the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Human Resources. 1995;30:S7–S56. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan GA, Salonen JT, Cohen RD, Brand RJ, Syme SL, Puska P. Social connections and mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular disease: prospective evidence from eastern Finland. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1988;128:370–380. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM, Shmotkin D, Ryff CD. Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:1007–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keys A, Fidanza F, Karvonen MJ, Kimura N, Taylor HL. Indices of relative weight and obesity. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1972;25:329–343. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(72)90027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Negative interaction and satisfaction with social support among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1995;50:P59–P73. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.2.p59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Negative Interaction and Heart Disease in Late Life Exploring Variations by Socioeconomic Status. Journal of Aging and Health. 2005;17:28–55. doi: 10.1177/0898264304272782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Weaver SL. Brandeis University; 1997. Midlife Development Inventory (MIDI) personality scales: Scale construction and scoring. Unpublished Technical Report. Retrieved from http://www.brandeis.edu/projects/lifespan/scales.html. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Weaver SL. Sociodemographic variations in the sense of control by domain: Findings from the MacArthur studies of midlife. Psychology and Aging. 1998a;13:556–562. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.13.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Weaver SL. The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998b;74:763–773. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenstein S, Smith MW, Kaplan GA. Psychosocial Predictors of Hypertension in Men and Women. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2001;161:1341–1346. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.10.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chae DH. Emotional support, negative interaction and major depressive disorder among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks: findings from the National Survey of American Life. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2012:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0347-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD. Personality, negative interactions, and mental health. The Social Service Review. 2008;82:223–251. doi: 10.1086/589462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancia G, Grassi, Pomidossi G, Gregorini L, Bertinieri G, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood-pressure measurement by the doctor on patient's blood pressure and heart rate. The Lancet. 1983;322:695–698. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92244-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancia G, Parati G, Pomidossi G, Grassi G, Casadei R, Zanchetti A. Alerting reaction rise in blood pressure during measurement by physician and nurse. Hypertension. 1987;9:209–215. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.9.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald M, Hertz RP, Unger AN, Lustik MB. Prevalence, awareness, and management of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes among United States adults aged 65 and older. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2009;64:256–263. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338:171–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMunn A, Hyde M, Janevic M, Kumari M. Health (Chapter 6) In: Marmot M, Banks J, Blundell R, Lessof C, Nazroo, J J, editors. Health, Wealth and Lifestyles of the Older Population: The 2002 English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies; 2003. pp. 207–230. Retrieved from http://www.ifs.org.uk/ELSA/reportWave1. [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Cohen S, Rabin BS, Skoner DP, Doyle WJ. Personality and Tonic Cardiovascular, Neuroendocrine, and Immune Parameters. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 1999;13:109–123. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1998.0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Kolarz CM. The effect of age on positive and negative affect: a developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1333–1349. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.5.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JT, Mahan TL, Rook KS, Krause N. Stable negative social exchanges and health. Health Psychology. 2008;27:78. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JT, Rook KS, Nishishiba M, Sorkin DH, Mahan TL. Understanding the relative importance of positive and negative social exchanges: Examining specific domains and appraisals. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60:P304–P312. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.6.p304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun MA, Keith VM. Effects of positive and negative social exchanges with various sources on depressive symptoms in younger and older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1998;53B:4–20. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.1.p4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paffenbarger RS, Wing AL, Hyde RT, Jung DL. Physical activity and incidence of hypertension in college alumni. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1983;117:245–257. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Campbell NR, Eliasziw M, Campbell TS. Major depression as a risk factor for high blood pressure: epidemiologic evidence from a national longitudinal study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:273–279. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181988e5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KS, Katan MB. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Public Health Nutrition. 2004;7:167–186. doi: 10.1079/phn2003587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS. The negative side of social interaction: Impact on psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46:1097–1108. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.5.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS. Investigating the positive and negative sides of personal relationships: Through a glass darkly? In: Spitzberg BH, Cupach WR, editors. The dark side of close relationships. Mahwah, N. J.: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 369–393. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Ladd GW, Dinella L. Gender differences in the interpersonal consequences of early-onset depressive symptoms. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2007;53:461–488. [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge T, Hogan BE. A Quantitative Review of Prospective Evidence Linking Psychological Factors With Hypertension Development. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64:758–766. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000031578.42041.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Keyes CLM. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:719–727. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster TL, Kessler RC, Aseltine RH. Supportive interactions, negative interactions, and depressed mood. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1990;18:423–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00938116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Berkman LF, Blazer D, Rowe JW. Social ties and support and neuroendocrine function: The MacArthur studies of successful aging. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;16:95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Sheets VL, Lugar R. Sources of conflict between friends in Russia and the United States. Cross-cultural Research. 2005;39:380–398. [Google Scholar]

- Shih JH, Eberhart NK, Hammen CL, Brennan PA. Differential exposure and reactivity to interpersonal stress predict sex differences in adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:103–115. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley BA, Weiss A, Der G, Taylor MD, Deary IJ. Neuroticism, extraversion, and mortality in the UK Health and Lifestyle Survey: a 21-year prospective cohort study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:923–931. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815abf83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Chen X, Heller K. Too much of a good thing? Intergenerational social support and the psychological well-being of older parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996:970–982. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton RA, Vacca J. Interpersonal competition in friendships. Sex Roles. 2007;57:617–627. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW, Cribbet MR, Nealey-Moore JB, Uchino BN, Williams PG, MacKenzie J, Thayer JF. Matters of the variable heart: Respiratory sinus arrhythmia response to marital interaction and associations with marital quality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100:103–119. doi: 10.1037/a0021136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW, Uchino BN, Berg CA, Florsheim P, Pearce G, Hawkins M, Olsen-Cerny C. Conflict and collaboration in middle-aged and older couples cardiovascular reactivity during marital interaction. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:274–286. doi: 10.1037/a0016067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW, Uchino BN, MacKenzie J, Hicks A, Campo RA, Reblin M, Light KC. Effects of Couple Interactions and Relationship Quality on Plasma Oxytocin and Cardiovascular Reactivity: Empirical Findings and Methodological Considerations. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Chida Y. The association of anger and hostility with future coronary heart disease: a meta-analytic review of prospective evidence. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;53:936–946. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneed RS, Cohen S. A Prospective Study of Volunteerism and Hypertension Risk in Older Adults. Psychology and Aging. 2013;28:578–586. doi: 10.1037/a0032718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud LR, Salovey P, Epel ES. Sex differences in stress responses: social rejection versus achievement stress. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:318–327. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suls J, Bunde J. Anger, anxiety, and depression as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: the problems and implications of overlapping affective dispositions. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:260–300. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tindle HA, Chang YF, Kuller LH, Manson JE, Robinson JG, Rosal MC, Matthews KA. Optimism, cynical hostility, and incident coronary heart disease and mortality in the Women’s Health Initiative. Circulation. 2009;120:656–662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.827642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tun PA, Miller-Martinez D, Lachman ME, Seeman T. Social strain and executive function across the lifespan: The dark (and light) sides of social engagement. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2013;20:320–338. doi: 10.1080/13825585.2012.707173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade TD, Kendler KS. The Relationships between Social Support and Major Depression: Cross-Sectional, Longitudinal, and Genetic Perspectives. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2000;188:251–258. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200005000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh JM, Rogot Pressman A, Cauley JA, Browner WS. Predictors of Physical Activity in Community-dwelling Elderly White Women. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:721–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00506.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule - Expanded Form. 1994 Retrieved from http://www.psychology.uiowa.edu/faculty/clark/panas-x.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Sullivan L, Parise H, Kannel WB. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: the Framingham experience. Archives of internal medicine. 2002;162:1867–1872. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witteman J, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Kok FJ, Sacks FM, Hennekens CH. Relation of moderate alcohol consumption and risk of systemic hypertension in women. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1990;65:633–637. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)91043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]