Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to describe employment by mental illness severity in the U.S. during 2009-2010.

Methods

The sample included all working-age participants (age 18 to 64) from the 2009 and 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (N = 77,326). Two well-established scales of mental health distinguished participants with none, mild, moderate, and serious mental illness. Analyses compared employment rate and income by mental illness severity and estimated logistic regression models of employment status controlling for demographic characteristics and substance use disorders. In secondary analyses, we assessed how the relationship between mental illness and employment varied by age and education status.

Results

Employment rates decreased with increasing mental illness severity (none = 75.9%, mild = 68.8%, moderate = 62.7%, serious = 54.5%, p<0.001). Over a third of people with serious mental illness, 39%, had incomes below $10,000 (compared to 23% among people without mental illness p<0.001). The gap in adjusted employment rates comparing serious to no mental illness was 1% among people 18-25 years old versus 21% among people 50-64 (p < .001).

Conclusions

More severe mental illness was associated with lower employment rates in 2009-2010. People with serious mental illness are less likely to be employed after age 49 than people with no, mild, or moderate mental illness.

INTRODUCTION

Mental disorders are associated with diminished labor market activity: people with mental illness are less likely to work (1-10), and those who do work earn less than workers without mental illness (1, 9). In studies of the general population, work has been associated with improvements in health and socioeconomic domains (11-14). Among people with mental illness, work has a positive association with economic (15), psychosocial (16-21), and clinical (22, 23) improvements. In many studies, employment also correlates with short-term reductions in mental health costs (24-30). Thus, monitoring disparities in employment by mental health status is a public health priority.

Three recent national phenomena are likely to have influenced labor participation in the U.S.: the large influx of people with mental illness enrolling onto disability (31); high unemployment rates associated with the recent recession (32); and evidence-based psychosocial services that support the employment goals of people with more severe mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia) (32-34).

Disability Enrollment

Economists estimate that $276 billion federal and state dollars were spent on working age beneficiaries of Social Security programs in 2002 (35). Mental illness is now the primary diagnosis for one in three persons receiving disabled worker benefits under the age of 50 (36). Beneficiaries with psychiatric impairments are often younger than other SSDI beneficiaries and therefore incur costs over a longer period of time (37, 38). As the number of disability beneficiaries with mental illness grows exponentially, policy makers have an increased interest in monitoring employment rates by mental health status.

Economic Recession

The most recent national recession in the United States was a period of substantially reduced economic activity. Unemployment changed dramatically, from an historic low of 4.4% before the recession in 2006, to a peak of 9.5% in 2009, with a slow recovery (32). Unemployment rates in 2010 remained well above 9%, even though the recession ended officially in June of 2009 (32, 39). The youth labor force (16- to 24-year-olds) and minorities were particularly vulnerable to unemployment during this period (40). Previous epidemiological studies describing associations between mental health and labor market outcomes may not generalize to the current period of high unemployment.

Evidence-based Interventions

Employment rates among individuals with severe mental disorders such as schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, or bipolar disorder more than double when they receive evidence-based supported employment services (i.e., Individual Placement and Support) (34). Evidence-based supported employment increases labor force participation among people with severe psychiatric illnesses through individualized services that focus on integrating vocational specialists into the mental health team and rapid job placement (41). This model represents a paradigmatic shift from previous employment interventions (e.g., day treatment) that offered sheltered experiences in preparation for work; these segregating models of care are slowly being defunded in the United States (43). Services that support integrated jobs may make employment more likely among people with severe mental illness than in the past.

Using data from the 2009 and 2010 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), this paper describes a comprehensive overview of the current employment situation of people in the United States by mental health status.

METHODS

Data source and study population

To study the link between employment and mental illness severity since the 2007-2009 recession, survey responses of all 77,326 working age adults (18-64 years old) from the 2009 and 2010 NSDUH public use files were analyzed (See: http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/SAMHDA/browse). The NSDUH is an annual survey of the civilian, non-institutionalized U.S. population aged 12 or older based on an independent, multistage area probability sample. The weighted response rate for all ages was 75.68% in 2009 and and 74.66% in 2010 (44).

Measures

Employment status and related outcomes

Employment served as the primary outcome variable. Respondents were asked whether they worked in the week prior to the interview and, among those who worked, whether they usually worked 35 or more hours per week. Following the practice used by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Full-time” refers to respondents who usually worked 35 or more hours per week, and “part-time” refers to other working respondents. “Unemployed” respondents did not have a job, were looking for a job, or were laid off. “Out of labor force” respondents were not in the labor force, which included students, persons caring for children full time, retired or disabled persons, or other persons not in the labor force. Additionally, the NSDUH collected information on each respondent’s total income in increments of $10,000, absenteeism (which we define as missed or skipped at least one day of work in the past year), occupation categories (using 2003 U.S. Census codes), and benefits status (family member received Social Security or Rail Road payments in past year and family member received Supplemental Security Income payment in past year). Less than 0.3% of Social Security payments are Rail Road payments (45). Hereafter we describe them as just “Social Security” payments, which, among this sample of adults aged 18-64 describes the population receiving disability payments.

Past-year mental illness severity

This paper focuses on four categories of mental illness severity: people with no mental illness; people with mild mental illness; people with moderate mental illness; and people with serious mental illness based on two assessments available in the NSDUH. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration developed models to predict mental illness severity based on responses to two short self-assessments, the K6 assessment of non-specific psychological distress (46, 47), and a shortened, eight-item version of the WHODAS assessment of functional impairment (48, 49). In 2008, 1,506 adults were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition (DSM-IV; SCID) via telephone by mental health clinicians. In years since, NSDUH reported four categories of mental illness severity based on parameter estimates from a model of scores on the clinician administered SCID as a function of the K6 and WHODAS scores (50, 51).

Selection of Adjustment Factors

We elected potential adjustment factors based on past labor supply studies. A meta-analysis of 62 studies of employment among people with schizophrenia found that cognitive functioning, education, negative symptoms, social support and skills, age, work history, and rehabilitation services predicted better employment outcomes, while positive symptoms, substance abuse, gender and hospitalization history did not; martial status was marginally significant (52). Relevant covariates among people with none or mild to moderate mental disorders were determined by referring to a review of studies conducted in industrialized nations (1) and census data. Among people with mild mental illness, gender (10, 53), age (10, 53, 54), education (10, 53, 54), marital status (55), race/ethnicity (10, 54), substance use (56), general health (10), children in household (53), criminal justice involvement (57), and a measure of the local community context (53) (urbanicity) were associated with work status.

Past-year substance use disorder

The NSDUH provides measures of substance abuse or dependence based on criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV). Alcohol, marijuana, hallucinogens, inhalants, tranquilizers, cocaine, heroin, pain relievers, stimulants (including methamphetamine), and sedatives were all directly covered by questions in the survey. Participants were categorized as having no substance use disorder, alcohol abuse only, alcohol dependence only, drug abuse only, drug dependence only, or abuse or dependence of both alcohol and drugs.

Health status

Self-reported general health was captured by asking, “Would you say your health in general is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” Due to the low frequency of responses indicating poor health, “fair” and “poor” categories were collapsed.

Sociodemographic characteristics

This study also included the following sociodemographic variables: age categories (18-25, 26-34, 35-49, 50-64), sex (female, male), race (White, Black, Hispanic, Other), educational attainment (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate or higher), marital status (never married, ever married), number of children less than 18 years of age in the household (zero, one, two, or at least three), number of times arrested and booked in the past year (none, once, twice or at least three times), and county type of residence (large metropolitan area, small metropolitan area, or nonmetropolitan area).

Analytic strategy

Descriptive analyses were conducted to compute employment rates, sociodemographic characteristics, and the remaining employment outcomes across mental illness severity categories. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with any employment stratified by mental illness severity. We ran all models twice: using the validated mental illness severity for the NSDUH based on WHODAS, K6, and a clinically-validated subsample, and again with just the K6 symptom score based on approximate mental illness percentile cutoffs (none versus mild/80th, mild versus moderate/90th, moderate versus serious/95th). The models based on only the K6 measure tested the sensitivity of our results to items in the WHODAS that may be too close to our outcome variables describing employment.

Given differences in the association between mental illness severity and education, and those between mental illness and age, we tested interactions of age and education by mental illness status in the final multivariate logistic regression model. All proportions and other estimates were computed using sample weights to reflect the target population of the study, working age adults in the US. In addition, variance estimates account for the complex stratified sampling design in the NSDUH using standard approaches (i.e. Taylor series approximations). STATA SE version 12 was used to conduct all analyses. The Dartmouth College Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects deemed these analyses, using publicly available, de-identified secondary data, exempt from review.

RESULTS

Demographics

Table 1 displays demographic information for 77,326 working-age adults by mental illness severity. The age distribution of respondents was similar across categories, with most of the population falling between ages 26 and 49. In contrast, more educated respondents were concentrated among the group without mental illness (30.7% versus 20.6% graduated from college in the “no mental illness” and “serious mental illness” categories, respectively)., The share of individuals without a substance use disorder was highest among respondents without mental illness (92.8%) compared with the serious mental illness group (75.6%). Self-reported fair or poor general health was also much more common in the group with serious mental illness (27.8%) relative to the group without mental illness (8.7%). Over 8% of the sample with serious mental illness reported an arrest in the past year, compared with only 2.6% in the group without mental illness. All differences above were statistically significant (p < .001).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of adults 18-64 by mental health status, 2009-2010

| Past Year | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Mental Illness | Mild Mental Illness | Moderate Mental Illness | Serious Mental Illness | |||||

| 57,283 | 10,643 | 4,170 | 5,230 | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 26647 | 48.1 | 6069 | 57.0 | 2524 | 58.9 | 3589 | 66.7 |

| Age | ||||||||

| 18-25 | 26604 | 15.9 | 6229 | 25.0 | 2474 | 24.4 | 3013 | 23.8 |

| 26-34 | 8506 | 18.5 | 1587 | 21.4 | 634 | 22.0 | 807 | 21.3 |

| 35-49 | 12655 | 33.8 | 1847 | 32.1 | 718 | 29.5 | 1019 | 32.6 |

| 50-64 | 5749 | 31.7 | 642 | 21.4 | 262 | 24.1 | 331 | 22.4 |

| Education | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 8384 | 13.3 | 1745 | 14.1 | 775 | 17.1 | 909 | 15.5 |

| High school graduate | 17496 | 30.0 | 3308 | 29.6 | 1358 | 28.7 | 1758 | 33 |

| Some college | 15508 | 26.0 | 3166 | 28.2 | 1262 | 29.4 | 1709 | 30.9 |

| College graduate | 12126 | 30.7 | 2086 | 28.1 | 713 | 24.8 | 794 | 20.6 |

| Ever Been Married | ||||||||

| Yes | 24960 | 28.8 | 3669 | 40.7 | 1453 | 41.8 | 2031 | 38.5 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 33120 | 64.8 | 6629 | 68.7 | 2652 | 68.3 | 3532 | 73.0 |

| Black | 6882 | 12.5 | 1270 | 12.0 | 468 | 11.3 | 470 | 9.5 |

| Hispanic | 8961 | 15.9 | 1433 | 12.4 | 593 | 14.4 | 684 | 12.1 |

| Other | 4551 | 6.8 | 973 | 6.9 | 375 | 6.1 | 484 | 5.5 |

| Substance Use | ||||||||

| No Substance Use Disorder | 47851 | 92.8 | 7880 | 82.5 | 2942 | 78.4 | 3487 | 75.6 |

| Abuse Alcohol Only | 2727 | 3.7 | 771 | 6.0 | 312 | 5.2 | 343 | 4.9 |

| Alcohol Dependent Only | 1374 | 2.2 | 748 | 6.3 | 340 | 8.1 | 525 | 9.8 |

| Abuse Drugs Only | 304 | .3 | 121 | .9 | 66 | 1.6 | 72 | 1.1 |

| Drug Dependent Only | 624 | .7 | 368 | 2.4 | 172 | 4.0 | 316 | 5.3 |

| Abuse or Dependent Alcohol & Drugs | 357 | .3 | 250 | 1.8 | 149 | 2.7 | 277 | 3.4 |

| General Health | ||||||||

| Excellent | 15952 | 27.7 | 2188 | 19.3 | 699 | 14.0 | 741 | 11.6 |

| Very Good | 21365 | 38.5 | 4037 | 35.8 | 1521 | 32.7 | 1759 | 30.1 |

| Good | 12717 | 25.1 | 2905 | 29.3 | 1269 | 32.0 | 1614 | 30.5 |

| Fair/Poor | 3474 | 8.7 | 1175 | 15.6 | 598 | 21.3 | 1056 | 27.8 |

| N Children < 18 in Household | ||||||||

| 0 | 35028 | 62.0 | 7210 | 63.8 | 2868 | 68.0 | 3590 | 66.9 |

| 1 | 8272 | 15.9 | 1445 | 15.0 | 611 | 14.8 | 753 | 14.6 |

| 2 | 6477 | 14.0 | 1041 | 13.5 | 382 | 10.9 | 500 | 11.2 |

| 3+ | 3680 | 8.1 | 603 | 7.7 | 224 | 6.3 | 325 | 7.3 |

| N Times Arrested and Booked in Past Year | ||||||||

| None | 50594 | 97.4 | 9470 | 95.1 | 3688 | 94.5 | 4626 | 91.9 |

| 1 | 1712 | 2.0 | 523 | 3.7 | 223 | 3.7 | 338 | 5.8 |

| 2 | 337 | .4 | 108 | .7 | 74 | 1.1 | 88 | 1.4 |

| 3+ | 192 | .2 | 68 | .4 | 37 | .8 | 60 | .9 |

| County Type | ||||||||

| Large Metro | 23860 | 54.7 | 4557 | 53.2 | 1759 | 53.1 | 2096 | 48.9 |

| Small Metro | 18526 | 29.9 | 3651 | 31.3 | 1479 | 32.5 | 1922 | 31.9 |

| Nonmetro | 11128 | 15.4 | 2097 | 15.5 | 850 | 14.3 | 1152 | 19.2 |

Source: National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 2009-2010.

Notes: Persons ages 18-64; crude N’s and adjusted percentages. All p-values for X2 test of differences across mental illness severity groups were statistically significant with p-values <.001

Employment Rates

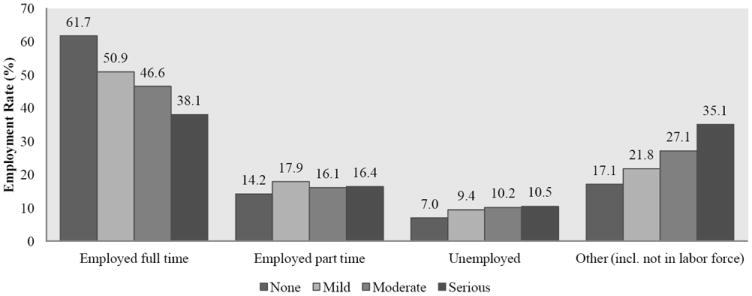

Table 2 presents (and Figure 1 highlights) nationally representative employment rates among working age adults by mental health status. Employment falls sharply as mental illness severity increases. Full time employment in 2009-2010 was 61.7% among people with no mental illness versus 38.1% among people with serious mental illness. Rates of part-time employment and unemployment were similar across severity categories. Rates of being out of the labor force were twice as high comparing adults with serious mental illness (35.1%) to adults without mental illness (17.1%). Differences in employment across mental illness severity groups were statistically significant (p < .001).

Table 2.

Employment and income of adults 18-64 by mental health status, 2009-2010

| Observations | Past Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Mental Illness | Mild Mental Illness | Moderate Mental Illness | Serious Mental Illness | |||||

| 57,283 | 10,643 | 4,170 | 5,230 | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Employment Rate | ||||||||

| Employed full time | 28100 | 61.7 | 4394 | 50.9 | 1576 | 46.6 | 1777 | 38.1 |

| Employed part time | 10300 | 14.2 | 2428 | 17.9 | 944 | 16.1 | 1149 | 16.4 |

| Unemployed | 5149 | 7.0 | 1211 | 9.4 | 548 | 10.2 | 660 | 10.5 |

| Other (including not in labor force) | 9965 | 17.1 | 2272 | 21.8 | 1020 | 27.1 | 1584 | 35.1 |

| Respondent’s Total Income | ||||||||

| Less than $10,000 (Including Loss) | 19812 | 23.1 | 4778 | 32.0 | 2014 | 35.5 | 2596 | 38.5 |

| $10,000 - $19,999 | 10625 | 16.3 | 2207 | 18.9 | 913 | 21.1 | 1230 | 23.2 |

| $20,000 - $29,999 | 6912 | 13.6 | 1223 | 13.4 | 451 | 12.4 | 546 | 12.1 |

| $30,000 - $39,999 | 5013 | 11.9 | 761 | 10.8 | 298 | 10.1 | 299 | 8.2 |

| $40,000 - $49,999 | 3489 | 9.2 | 456 | 6.7 | 157 | 7.6 | 194 | 5.8 |

| $50,000 - $74,999 | 4295 | 13.2 | 554 | 10.3 | 151 | 6.9 | 190 | 7.5 |

| $75,000 or more | 3368 | 12.8 | 326 | 7.8 | 104 | 6.3 | 115 | 4.8 |

| Past Year Family Receive Social Security | 5050 | 12.8 | 1186 | 14.7 | 531 | 18.2 | 786 | 20.8 |

| Past Year Family Receive SSI Payments | 2925 | 5.8 | 818 | 8.6 | 380 | 11.5 | 567 | 13.2 |

| Respondent’s Total Income* | ||||||||

| Less than $10,000 (Including Loss) | 9130 | 12.3 | 2241 | 19.1 | 874 | 20.1 | 1017 | 21.4 |

| $10,000 - $19,999 | 8296 | 15.7 | 1655 | 18.7 | 654 | 20.2 | 816 | 23.0 |

| $20,000 - $29,999 | 5989 | 15.0 | 1035 | 15.6 | 358 | 15.5 | 429 | 16.3 |

| $30,000 - $39,999 | 4488 | 13.8 | 666 | 13.5 | 256 | 14.0 | 242 | 11.8 |

| $40,000 - $49,999 | 3222 | 11.0 | 419 | 8.9 | 142 | 10.7 | 166 | 8.3 |

| $50,000 - $74,999 | 4062 | 16.2 | 503 | 13.9 | 138 | 9.9 | 153 | 11.1 |

| $75,000 or more | 3213 | 16.0 | 303 | 10.4 | 98 | 9.6 | 103 | 8.1 |

| Missed or Skipped Work (1+ Day in Past Week)* | 9559 | 21.5 | 2304 | 30.5 | 997 | 37.9 | 1239 | 40.7 |

| Occupation Category* | ||||||||

| Executive/Administrative/Managerial/Financial | 4053 | 14.5 | 578 | 13.6 | 199 | 12 | 5062 | 11.4 |

| Professional (not Education/Entertainment/Media) | 3696 | 12.8 | 586 | 11.4 | 194 | 11.9 | 4688 | 10.3 |

| Education and Related Occupations | 2166 | 6.2 | 401 | 7.1 | 154 | 6.5 | 2886 | 8.1 |

| Entertainers, Sports, Media, and Communications | 805 | 2.2 | 196 | 3.1 | 60 | 2.2 | 1141 | 3.6 |

| Technicians and Related Support Occupations | 2216 | 5.2 | 457 | 5.9 | 173 | 5.3 | 3075 | 6.9 |

| Sales Occupations | 4574 | 9.9 | 953 | 11.6 | 392 | 14.3 | 6352 | 11.4 |

| Office & Administrative Support Workers | 4937 | 12.4 | 973 | 14.2 | 369 | 14.3 | 6722 | 14.5 |

| Protective Service Occupations | 930 | 2.5 | 125 | 1.9 | 43 | 2.5 | 1143 | 2.2 |

| Service Occupations, Except Protective | 6648 | 11.7 | 1485 | 15.5 | 547 | 14.3 | 9368 | 18.1 |

| Farming, Fishing, & Forestry Occupations | 375 | .7 | 45 | .3 | 15 | .2 | 447 | .3 |

| Installation, Maintenance & Repair Workers | 1386 | 4 | 154 | 2.5 | 53 | 2.5 | 1653 | 1.5 |

| Construction Trades & Extraction Workers | 2426 | 5.9 | 319 | 4.4 | 101 | 4.7 | 2925 | 2.5 |

| Production, Machinery Setters/Operators/Tenders | 2199 | 5.9 | 286 | 4.0 | 117 | 5.4 | 2734 | 4.9 |

| Transportation & Material Moving Workers | 2283 | 6.0 | 334 | 4.7 | 131 | 3.9 | 2883 | 4.2 |

Source: National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 2009-2010.

Notes:

among persons employed full- or part-time in the past year; crude N’s and adjusted percentages reports; All p-values forX2 test of differences across mental illness severity groups were statistically significant with p-values <.001

Figure 1.

Employment rates among adults 18-64 by mental health status

Note:Figure 1 presents estimated rates of employment outcomes. Employment rates based on logistic regression models that adjust for confounding are presented in table 3, with full model results shown in Appendix 1.

Other Employment Outcomes

Table 2 also provides detail about occupation, income, and absenteeism among workers by mental illness severity. Employment rates by occupation were largely consistent across mental illness severity categories, although individuals with mental illness were slightly more likely to be in sales or service occupations. In spite of these similarities, people with serious mental illness who work earned far less than employed people without a serious mental illness. For example, 38.5% of individuals with moderate or serious mental illness earned under $10,000, compared with only 23.1% of those without mental illness. Among families of respondents with serious mental illness, 20.8% received Social Security, and 13.2% received Supplemental Security Income in the past year. People with serious mental illness were more likely to miss or skip a day of work (40.7%) than people with no mental illness (21.5%), mild mental illness (30.5%), or moderate mental illness (37.9%). All differences shown in Table 3 across mental illness severity groups were statistically significant (p < .001).

Table 3.

Employment rates among adults 18-64 by mental illness severity, 2009-2010

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Observations | No Mental Illness | Mild Mental Illness | Moderate Mental Illness | Serious Mental Illness | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| % | OR | CI | % | OR | CI | % | OR | CI | % | OR | CI | |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 18-25 | 65 | --- | --- | 66 | --- | --- | 65 | --- | --- | 64 | --- | --- |

| 26-34 | 77 | 1.92 | 1.75-2.12 | 70 | 1.23 | .99-1.52 | 72 | 1.41 | 1.04-1.92 | 61 | .90 | .69-1.16 |

| 35-49 | 80 | 2.25 | 2.04-2.48 | 74 | 1.47 | 1.15-1.87 | 71 | 1.36 | .95-1.94 | 64 | 1.00 | .76-1.33 |

| 50-64 | 69 | 1.22 | 1.08-1.38 | 65 | .93 | .69-1.27 | 52 | .56 | .36-.86 | 48 | .50 | .34-.72 |

| Race | ||||||||||||

| White | 71 | --- | --- | 70 | --- | --- | 70 | --- | --- | 62 | --- | --- |

| Black | 69 | .87 | .78-.97 | 61 | .66 | .51-.85 | 57 | .59 | .43-.81 | 58 | .83 | .56-1.22 |

| Hispanic | 71 | 1.00 | .87-1.14 | 70 | 1.02 | .81-1.29 | 71 | 1.16 | .83-1.62 | 63 | 1.04 | .75-1.43 |

| Other | 68 | .84 | .71-.98 | 64 | .76 | .56-1.04 | 61 | .71 | .42-1.20 | 66 | 1.22 | .62-2.41 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 58 | --- | --- | 54 | --- | --- | 46 | --- | --- | 46 | --- | --- |

| High school graduate | 69 | 1.64 | 1.46-1.83 | 65 | 1.61 | 1.29-2.00 | 64 | 2.17 | 1.58-3.00 | 59 | 1.67 | 1.20-2.33 |

| Some college | 75 | 2.26 | 2.02-2.52 | 73 | 2.48 | 1.94-3.18 | 70 | 2.88 | 2.00-4.15 | 65 | 2.26 | 1.69-3.03 |

| College graduate | 77 | 2.60 | 2.25-3.01 | 78 | 3.17 | 2.45-4.09 | 79 | 4.69 | 3.02-7.28 | 74 | 3.44 | 2.28-5.18 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 76 | --- | --- | 72 | --- | --- | 76 | --- | --- | 76 | --- | --- |

| Female | 65 | .55 | .52-.59 | 65 | .73 | .61-.87 | 65 | .97 | .77-1.22 | 65 | .82 | .64-1.05 |

| Ever Been Married | ||||||||||||

| No | 69 | --- | --- | 66 | --- | --- | 65 | --- | --- | 58 | --- | --- |

| Yes | 73 | 1.22 | 1.10-1.34 | 71 | 1.31 | 1.05-1.63 | 67 | 1.09 | .78-1.52 | 67 | 1.52 | 1.10-2.09 |

| General Health | ||||||||||||

| Excellent | 73 | --- | --- | 71 | --- | --- | 71 | --- | --- | 68 | --- | --- |

| Very Good | 74 | 1.07 | .97-1.18 | 72 | 1.03 | .87-1.22 | 67 | .82 | .57-1.17 | 65 | .90 | .67-1.20 |

| Good | 69 | .82 | .74-.91 | 67 | .83 | .70-.99 | 67 | .82 | .54-1.24 | 59 | .67 | .51-.88 |

| Fair/Poor | 51 | .34 | .30-.39 | 48 | .35 | .26-.45 | 45 | .30 | .19-.46 | 36 | .25 | .18-.34 |

| N Children < 18 in Household | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 71 | --- | --- | 69 | --- | --- | 65 | --- | --- | 62 | --- | --- |

| 1 | 74 | 1.20 | 1.10-1.31 | 69 | 1.02 | .81-1.27 | 70 | 1.28 | .87-1.88 | 59 | .85 | .63-1.16 |

| 2 | 71 | 1.03 | .94-1.13 | 69 | 1.04 | .81-1.34 | 72 | 1.43 | .95-2.16 | 62 | 1.00 | .71-1.42 |

| 3+ | 63 | .67 | .60-.76 | 62 | .73 | .55-.98 | 60 | .80 | .46-1.37 | 61 | .92 | .61-1.39 |

| N Times Arrested and Booked in Past Year | ||||||||||||

| None | 71 | --- | --- | 69 | --- | --- | 67 | --- | --- | 62 | --- | --- |

| 1 | 62 | .65 | .52-.80 | 60 | .67 | .50-.89 | 62 | .78 | .51-1.21 | 51 | .59 | .38-.92 |

| 2 | 55 | .46 | .29-.72 | 46 | .34 | .20-.60 | 56 | .59 | .31-1.12 | 59 | .87 | .42-1.82 |

| 3+ | 59 | .55 | .31-.95 | 55 | .52 | .24-1.14 | 50 | .45 | .14-1.44 | 53 | .66 | .27-1.65 |

| County Type | ||||||||||||

| Large Metro | 71 | --- | --- | 68 | --- | --- | 68 | --- | --- | 63 | --- | --- |

| Small Metro | 70 | .98 | .91-1.06 | 69 | 1.03 | .88-1.21 | 64 | .79 | .62-1.02 | 62 | .94 | .77-1.14 |

| Nonmetro | 70 | .97 | .87-1.08 | 68 | 1.02 | .83-1.25 | 66 | .92 | .68-1.23 | 59 | .84 | .61-1.15 |

| Substance Use | ||||||||||||

| No Substance Use Disorder | 70 | --- | --- | 68 | --- | --- | 66 | --- | --- | 61 | --- | --- |

| Abuse Alcohol Only | 74 | 1.23 | 1.01-1.49 | 72 | 1.20 | .87-1.65 | 69 | 1.17 | .73-1.88 | 65 | 1.19 | .77-1.82 |

| Alcohol Dependent Only | 71 | 1.01 | .83-1.24 | 69 | 1.04 | .72-1.49 | 72 | 1.33 | .93-1.90 | 68 | 1.37 | 1.01-1.86 |

| Abuse Drugs Only | 72 | 1.07 | .75-1.51 | 61 | .70 | .41-1.20 | 63 | .86 | .41-1.80 | 59 | .92 | .34-2.45 |

| Drug Dependent Only | 71 | 1.04 | .75-1.44 | 59 | .63 | .44-.89 | 52 | .52 | .31-.87 | 57 | .83 | .57-1.21 |

| Abuse or Dependent Alcohol & Drugs | 64 | .74 | .45-1.21 | 60 | .67 | .42-1.06 | 60 | .74 | .44-1.23 | 68 | 1.4 | .92-2.19 |

Source: National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 2009-2010.

Notes: Persons ages 18-64; rates (%) are adjusted predicted probabilities based on logistic regression models stratified by mental illness severity groups; CI = 95 percent confidence intervals; Odds ratios and confidence intervals for the adjusted relationship between mental illness severity and employment status are reported in Appendix 1.

Associations with Full- or Part-Time Employment

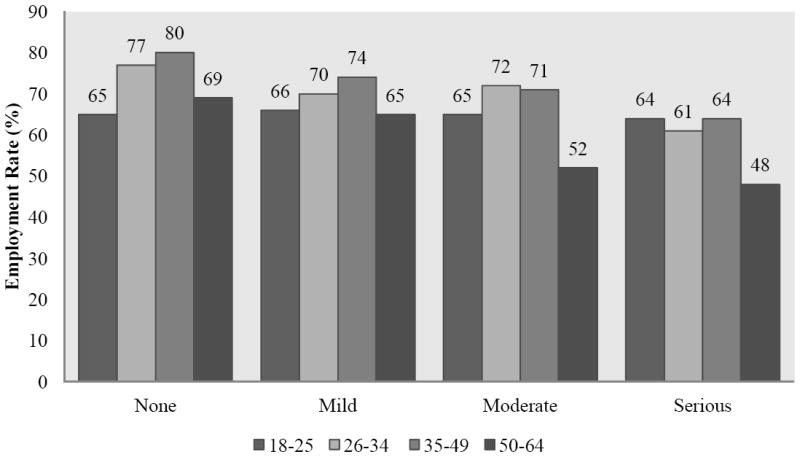

Table 3 provides estimates from logistic regression analyses that identified variables associated with employment status. The likelihood of employment generally increased from young adulthood (18-25) to middle age (26-34), except among individuals with serious mental illness. After reaching age 50, people with moderate and serious mental illness were far less likely to work than those with mild or no mental illness (p < 0.001 for a test of joint significance of age interacted with mental illness severity). Education status was strongly associated with employment, within all categories of mental illness severity. (Appendix Figure 2).

Overall models where mental illness severity was defined using the validated NSDUH model versus the symptom-only classification (K6) showed strikingly similar patterns (Appendix Table 1).

DISCUSSION

In a nationally representative sample of working age adults in 2009-2010, people with moderate and serious mental illness were employed less often than adults with no reported mental illness. Like national data from the 1990s, we found that people with mental illness are represented in all occupation categories (10). Yet, income disparities remained. Nearly 40% of people with serious mental illness had income under $10,000 per year, well below substantial gainful activity thresholds that determine eligibility for federal disability payments. Mental illness had a much weaker relationship to employment among people under 50 years of age.

People with more serious mental illness were less likely to report full time employment than people without, although this estimate is nearly double the full-time employment rates reported in an earlier study (38% in the current study versus 24% in a previous study) (10). The previous study analyzed data from the 1994-1995 National Health Interview Survey on Disability, which used a more stringent definition of serious mental illness that excludes undiagnosed individuals (self-reported diagnosis of schizophrenia, paranoid states, mood disorders, other nonorganic psychoses, or psychosis with origins specific to childhood in the past twelve months). One possible explanation is that undiagnosed individuals may not access services that would result in diagnostic assessment because they have fewer functional limitations.

Compared with the large differences in full-time work by mental illness severity, differences in unemployment and part-time employment were much smaller in magnitude. Rather than working part-time or seeking work, people with mental illness who are not working full-time appear to be displaced from the labor force entirely (out of the labor force). Most people with mental illness, even the most severely disabled, are capable of part-time work when provided appropriate supports (58). There are several explanations for why so many individuals with mental illness are out of the labor force entirely. People with more serious mental health issues have fewer incentives to seek work because disability policies often restrict eligibility to those not working in any significant capacity (59); employers are reluctant to hire individuals with psychiatric disabilities (60); and people with serious mental illness may be unaware of or unable to access job supports (34).

Variation in the age-employment relationship across mental illness severity groups was substantial. Among older adults, half with moderate or serious mental illness worked part-time or full-time, substantially less than their peers with mild or no mental illness, replicating an earlier study (10).Many older non-working adults with moderate to serious mental illness were out of the labor force, rather than unemployed, a comparison not examined in prior research. Adults over 50 years of age with moderate and serious mental illness may be more likely to drop out of the workforce due to social acceptability (supply), but discrimination against older workers with mental illness (demand) is a more likely explanation because many older people with serious mental illness want to work (61). In contrast, younger workers living with mental illness do not experience the same decrement to labor force participation, suggesting opportunities to prevent exits from the labor force in younger populations.

Education status, known to facilitate employment opportunities (62), was the strongest predictor of employment even among people with serious mental illness. This finding is consistent with previous research in clinical and community samples (10, 63, 64), and suggests that facilitating educational achievement may facilitate job placement. Longitudinal research is needed to test alternative explanations: educational achievement may be a proxy for later illness onset, less serious illness, or more intensive service use.

Several limitations warrant consideration. This cross-sectional, descriptive study does not permit causal interpretation of any association between mental illness and employment outcomes. Even without the ability to draw causal inference from the results, these descriptive data fill a gap in evidence. Most psychiatric epidemiological studies of workforce participation focus on a single diagnostic group, use simplistic vocational outcomes (e.g., employment versus no employment), or fail to compare samples with mental illness to mentally well controls. Mechanic et al. (2002) provided a richer overview, describing employment rates by work intensity and occupational category among people with none, any, or serious mental illness, though this study presented data from the 1990s when the economic circumstances differed considerably from those since the most recent recession lasting from 2007 to 2009 (10).

Additionally, the study sample did not include people in institutional settings (prisons, hospitals, treatment centers), where individuals with the greatest illness burden are likely to reside, although institutionalized individuals are not generally participating in the labor force. Third, short-form diagnostic surveys commonly used in the NSDUH are limited in their ability to distinguish between individuals with moderate affective illness and individuals with serious mental illness (typically defined as psychotic disorders with at least 2 years of illness burden).Although steps were taken to validate these self-reported measures of illness (50, 51), self-report bias may have over or under estimated the prevalence of mild, moderate, or serious mental illness. Lack of information on date of illness onset significantly limited possible inferences (1). Finally, participation in the national survey was high, but incomplete, which may have resulted in an under-or over-estimation of mental illness.

CONCLUSION

Employment rates varied substantially by mental illness severity in 2009-2010. Even during times of high unemployment seriously mentally ill college graduates had relatively strong employment outcomes. Unemployment rates spike among people with serious mental illness over age 50, even compared to age-matched peers.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Full- or part-time employment rates among adults 18-64 by age within mental health status groups

Note:Figure 2 presents employment rates adjusted for age, gender, education, marital status, race/ethnicity, substance use disorders, self-reported general health, number of children in household, arrests in last year, and county type. The decrement to employment for older workers with serious mental illness is significantly larger compared with younger workers with serious mental illness, based on an interaction term between mental illness severity and age in a logistic regression model predicting full- or part-time employment.

Acknowledgments

National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant # DAR01DA030391

Footnotes

Disclosure of Interest: None

Contributor Information

Alison Luciano, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Psychiatry, alison.luciano.gr@dartmouth.edu.

Ellen Meara, Dartmouth - Health Care Policy, New Hampshire; National Bureau of Economic Research -1050 Massachusetts Ave. , Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, United States.

References

- 1.Frank RG, Koss C. Mental health and labor markets productivity loss and restoration. 2005 Contract No.: 38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, Ball DE, Kessler RC, Moulis M, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66(9):1122–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldwin ML, Marcus SC. Labor market outcomes of persons with mental disorders. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society. 2007;46(3):481–510. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Heeringa S, Lakoma MD, Petukhova M, Rupp AE, Schoenbaum M, et al. The individual-level and societal-level effects of mental disorders on earnings in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(6):703–11. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08010126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blyler CR. Employment and Major Depressive Episode. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowell AJ, Luo Z, Masuda YJ. Psychiatric disorders and the labor market: an analysis by disorder profiles. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 2009;12(1):3–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnett-Zeigler I, Ilgen MA, Bohnert K, Miller E, Islam K, Zivin K. The Impact of Psychiatric Disorders on Employment: Results from a National Survey (NESARC) Community Ment Health J. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9510-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pratt LA. Characteristics of adults with serious mental illness in the United States household population in 2007. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(10):1042. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levinson D, Lakoma MD, Petukhova M, Schoenbaum M, Zaslavsky AM, Angermeyer M, et al. Associations of serious mental illness with earnings: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;197(2):114–21. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.073635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mechanic D, Bilder S, McAlpine DD. Employing persons with serious mental illness. Health Affairs. 2002;21(5):242–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warr P. Work unemployment and mental health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blustein DL. The role of work in psychological health and well-being: A conceptual, historical, and public policy perspective. American Psychologist. 2008;63:228–40. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.4.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fogg NP, Harrington PE, McMahon BT. The impact of the Great Recession upon the unemployment of Americans with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2010;33:193–202. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barr B, Taylor-Robinson D, Scott-Samuel A, McKee M, Stuckler D. Suicides associated with the 2008-10 economic recession in England: time trend analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e5142. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5142. (Published 14 August 2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook JA, Blyler CR, Leff HS, McFarlane WR, Goldberg RW, Gold PB, et al. The employment intervention demonstration program: major findings and policy implications. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2008;31(4):291–5. doi: 10.2975/31.4.2008.291.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fabian ES. Work and the quality of life. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1989;12:39–49. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fabian ES. Supported employment and the quality of life: does a job make a difference? Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arns PG, Linney JA. Work self and life satisfaction for persons with severe and persistent mental disorders. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1993;17(2):63–79. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arns PG, Linney JA. The relationship of service individualization to client functioning in programs for severely mentally ill persons. Community Mental Health Journal. 1995;31(2):127–37. doi: 10.1007/BF02188762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthews WC. Effects of a work activity program on the self concept of chronic schizophrenics. ProQuest Information & Learning. 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Dongen CJ. Self-esteem among persons with severe mental illness. Issues in mental health nursing. 1998;19(1):29–40. doi: 10.1080/016128498249196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook JA, Razzano L. Vocational rehabilitation for persons with schizophrenia: Recent research and implications for practice. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2000;26(1):87–103. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaebel W, Pletzcker A. Prospective Study of Course of Illness in Schizophrenia: Part II. Prediction of Outcome. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1987;13(2):299. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bond GR, Dietzen LL, Vogler KM, Katuin CH, McGrew JH, Miller LD. Toward a framework for evaluating costs and benefits of psychiatric rehabilitation: Three case examples. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 1995;5:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burns J, Catty J, White S, Becker T, Koletsi M, Fioritti A, et al. The impact of supported employment and working on clinical and social functioning: results of an international study of individual placement and support. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;5:949–58. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark RE. Supported employment and managed care: can they coexist? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 1998;22(1):62–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henry AD, Lucca AM, Banks SM, Simon L, Page S. Inpatient hospitalizations and emergency service visits among participants in an Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model program. Mental Health Services Research. 2004;6:227–37. doi: 10.1023/b:mhsr.0000044748.24924.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Latimer E. Economic impacts of supported employment for the severely mentally ill. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;46:496–505. doi: 10.1177/070674370104600603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perkins DV, Born DL, Raines JA, Galka SW. Program evaluation from an ecological perspective: Supported employment services for pesons with serious psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2005;28:217–4. doi: 10.2975/28.2005.217.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider J, Boyce M, Johnson R, Secker J, Slade J, Grove B, et al. Impact of supported employment on service costs and income of people with mental health needs. Journal of Mental Health. 2009;18:533–42. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burkhauser RV, Daly M. The Declining Work and Welfare of People with Disabilities. Washington, D. C.: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor force statistics from the Current Population Survey. United States Department of Labor; 2013. Available from: http://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Autor DH, Duggan MG. The growth in the social security disability rolls: a fiscal crisis unfolding. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006;20:71–96. doi: 10.1257/jep.20.3.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drake RE, Bond GR, Becker DR. Individual Placement and Support: An Evidence-Based Approach to Supported Employment. USA: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodman N, Stapleton D. Federal program expenditures for working-age people with disabilities: Research Report. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barrett CL. Number of SSDI beneficiaries under age-50 with a primary impairment of mental disorder in payment in July 2006, from the Social Security Administration Continuing Disability Review Selection File FY 2008. 2007 unpublished raw data. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McAlpine DD, Warner L. Barriers to employment among persons with mental illness: A review of the literature. Center for Research on the Organization and Financing of Care for the Severely Mentally Ill, Institute for Health, Health Care Policy and Aging Research, Rutgers University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hennessey JC, Dykacz JM. Projected outcomes and length of time in the disability insurance program. Social Security Bulletin. 1989;52:2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Business Cycle Dating Committee. [2013];National Bureau of Economic Research. 2010 Available from: http://www.nber.org/cycles/sept2010.html.

- 40.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employment status of the civilian noninstitutional population 16 to 24 years of age by sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, July 2010-2013. Washington, DC: United States Department of Labor; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Becker DR, Swanson SJ, Bond GR, Merrens MR. Evidence-based supported employment fidelity review manual 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peterson AE, Drake RE, Bond GR, Becker DR, Carpenter-Song E, Lord S, et al. Evidence-based Supported Employment for People with Severe Mental Illness: Past, Current, and Future Research. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cimera RE. The cost-effectiveness of supported employment and sheltered workshops in Wisconsin (FY 2002 - FY 2005) Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2007;26(3):153–8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011. Contract No.: NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Social Security Administration. Number of Social Security Beneficiaries. 2012 Available from: http://www.ssa.gov/oact/progdata/icpGraph.html.

- 46.Furukawa TA, Kessler RC, Slade T, Andrews G. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33(2):357–62. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rehm J, Üstün TB, Saxena S, Nelson CB, Chatterji S, Ivis F, et al. On the development and psychometric testing of the WHO screening instrument to assess disablement in the general population. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1999;8(2):110–22. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Novak SP, Colpe LJ, Barker PR, Gfroerer JC. Development of a brief mental health impairment scale using a nationally representative sample in the USA. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2010;19(S1):49–60. doi: 10.1002/mpr.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Colpe LJ, Barker PR, Karg RS, Batts KR, Morton KB, Gfroerer JC, et al. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health Mental Health Surveillance Study: calibration study design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2010;19(S1):36–48. doi: 10.1002/mpr.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aldworth J, Colpe LJ, Gfroerer JC, Novak SP, Chromy JR, Barker PR, et al. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health Mental Health Surveillance Study: calibration analysis. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2010;19(S1):61–87. doi: 10.1002/mpr.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsang HW, Leung AY, Chung RC, Bell M, Cheung WM. Review on vocational predictors: a systematic review of predictors of vocational outcomes among individuals with schizophrenia: an update since 1998. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;44(6):495–504. doi: 10.3109/00048671003785716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamilton VH, Merrigan P, Dufresne É. Down and out: Estimating the relationship between mental health and unemployment. Econometrics and Health Economics. 1997;6:397–406. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(199707)6:4<397::aid-hec283>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frank R, Gertler P. An assessment of measurement error bias for estimating the effect of mental distress on income. The Journal of Human Resources. 1991;26(1):154–64. [Google Scholar]

- 55.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Participation Rates by Marital Status, Sex, and Age: 1970 to 2010. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alexandre PK, French MT. Labor supply of poor residents in metropolitan Miami, Florida: The role of depression and the co-morbid effects of substance use. The journal of mental health policy and economics. 2001;4:161–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Apel R, Sweeten G. The impact of incarceration on employment during the transition to adulthood. Social Problems. 2010;57:448–79. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR. Generalizability of the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model of supported employment outside the US. World Psychiatry. 2012;11:32–9. doi: 10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Social Security Administration. Disability Benefits. 2012 Contract No.: 05-10029. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kinn LG, Holgersen H, Aas R, Davidson L. “Balancing on Skates on the Icy Surface of Work”: A metasynthesis of work participation for persons with psychiatric disabilities. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10926-013-9445-x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Auslander LA, Jeste DV. Perception of problems and needs for services among older outpatients with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Community Mental Health Journal. 2002;38:391–402. doi: 10.1023/a:1019808412017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eide ER, Showalter MH. Human Capital. In: Peterson P, Baker E, McGaw B, editors. International Encyclopedia of Education. Third Edition. Oxford: 2010. pp. 282–7. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Michon HW, van Weeghel J, Kroon H, Schene AH. Person-related predictors of employment outcomes after participation in psychiatric vocational rehabilitation programmes: A systematic review. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2005;40:408–16. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0910-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bond GR, Drake RE. Predictors of competitive employment among patients with schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2008;21:362–9. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328300eb0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.