Abstract

Background

The decision to continue medical therapy or recommend endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) can be challenging in patients with refractory chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS). The objective of this study was to evaluate continued medical therapy versus ESS for patients with refractory CRS who have severe reductions in baseline diseasespecific quality of life (QoL).

Methods

This was a prospective longitudinal crossover study between August 2011 and June 2013. All patients were > 18 years old, diagnosed with CRS based on guideline recommendations, failed initial medical therapy and elected ESS. While waiting for ESS, all patients received continued medical therapy. The preoperative waiting period outcomes (continued medical therapy) were compared to the postoperative outcomes. The primary outcome was change in disease-specific QoL (SNOT-22). Secondary outcomes were change in endoscopic grading (Lund-Kennedy score), medication consumption, and work-days missed in the preceding 90 days.

Results

31 patients were enrolled. Mean baseline SNOT-22 score was 57.6. Following a mean of 7.1 months of continued medical therapy, there was a worsening in SNOT- 22 score (57.6 to 66.1; p=0.006). After ESS, with a mean postoperative follow-up of 14.6 months, there was a significant improvement in SNOT-22 score (66.1 to 16.0; <0.001). There was also a significant improvement in endoscopic grading (<0.001) coupled with a reduction in both work days lost (<0.001) and medication consumption (<0.01).

Conclusions

Results from the study suggest that ESS is a more effective intervention compared to continued medical therapy for patients with refractory CRS who have severe reductions in their baseline disease-specific QoL.

Keywords: chronic rhinosinusitis, sinusitis, medical therapy, quality of life, endoscopic sinus surgery

Introduction

When patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) have persistent symptoms despite initial medical therapy, the decision to recommend continued medical therapy or endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) can be challenging. Evidence suggests that the primary driver of patients’ choice to pursue ESS is the degree of their baseline disease-specific quality of life (QoL) [1]. However, in an economic climate where physicians need to critically assess the benefit of their recommended interventions, patients often depend on physicians to recommend the most appropriate options while taking effectiveness, risk, and cost into consideration. Therefore, in order to increase the value of care, it is important to elucidate which patients with refractory CRS would most benefit from continued medical therapy versus ESS.

Several studies have already begun evaluating continued medical therapy versus ESS for patients with refractory CRS. A prospective multi-institutional study by Smith et al. demonstrated that patients with less reduction in their baseline disease-specific QoL received significant clinical improvements with continued medical therapy. In comparison, patients with large reductions in their baseline QoL received significant improvements with ESS [2]. Furthermore, patients with large reductions in their baseline QoL who initially elected continued medical therapy failed to receive improvement which promoted them to cross over to receive ESS at which point they obtained significant QoL improvements after surgery. This finding was confirmed in a study by Smith and Rudmik which demonstrated that patients with severe reductions in their baseline QoL who were treated with continued medical therapy resulted in a worsening QoL and increased missed work days after 6 months of best medical therapy [3].

The purpose of this study was to evaluate continued medical therapy versus ESS in patients with refractory CRS who have severely reduced baseline QoL and who elected ESS. The primary outcome was change in disease-specific QoL and secondary outcomes included changes in endoscopic grading, medication consumption, and work days missed in the preceding 90 days. We hypothesize that ESS would be a more effective intervention for patients with refractory CRS who have severe reductions in their baseline QoL compared to continuing with medical therapy alone.

Methods

I. Study Design

This was a prospective longitudinal crossover study that enrolled patients between August 2011 and June 2013 (clinicaltrials.gov # NCT01332136). Eligible patients were recruited at a tertiary level rhinology clinic by the principle investigator (LR) at the University of Calgary. Institutional ethics review board approval was obtained (ID: #24208) and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

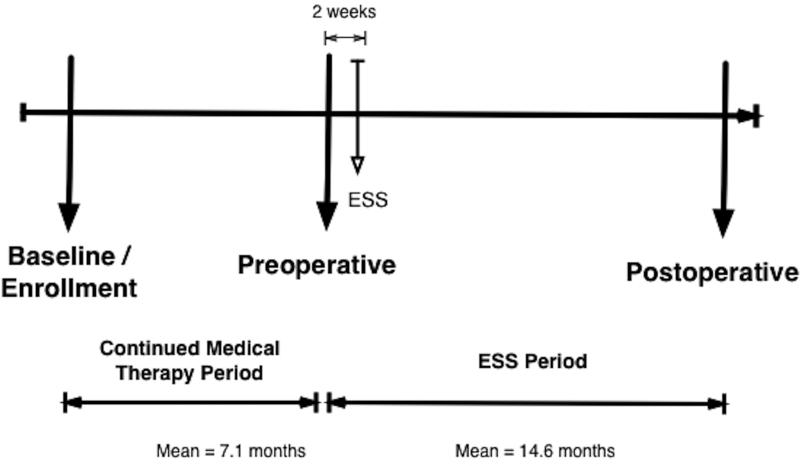

All patients elected ESS for the indication of refractory CRS after failed initial medical therapy. Failure of medical therapy was defined as persistent symptoms and reduced disease-specific QoL despite a 3 month minimum of high-volume saline irrigations and topical intranasal steroid therapy with a minimum of 7 days of systemic corticosteroid +/− a 2 week course of broad spectrum systemic antibiotic. Due to limited health care resources and the use of rationing cost control strategies in Canada, prolonged surgical waitlists often result in patients waiting 6 to 12 months for ESS. This provided a unique opportunity to evaluate the impact of continued medical therapy alone in patients electing ESS. For this study, all patients received appropriate continued medical therapy prior to ESS and then crossed over to receive ESS (Figure 1). The longitudinal crossover methodology enabled patients to act as their own controls.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram outlining data collection time points

II. Patient Sample

Inclusion criteria included age >18 years, diagnosis of CRS based on the 2007 Adult Sinusitis Guidelines, failure of initial medical management, and elected ESS[4]. Exclusion criteria included the inability to complete questionnaires or clinical evaluations in English, contraindication to medical therapy, or the presence of any of the following: systemic inflammatory disease, ciliary dysmotility or cystic fibrosis.

III. Intervention: Continued Medical Therapy

All enrolled patients continued medical treatment until the day of their ESS. A pragmatic approach to continued medical therapy was adopted to reflect common clinical practice. Continued medical therapy included appropriately prescribed sinonasal irrigations, topical steroid sprays, high-volume budesonide-saline irrigations, rescue systemic antibiotics and systemic corticosteroids for acute exacerbations, systemic antihistamines, and leukotriene receptor antagonists [5-7].

IV. Intervention: Endoscopic Sinus Surgery

Prior to ESS, all patients received 7 days of prednisone 30 mg once daily and 7 days of either amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 875 mg twice daily or trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole DS twice daily. The postoperative care protocol involved starting high volume isotonic saline sinonasal irrigations one day after surgery, 7 days of the systemic antibiotic (same agent as the one prescribed preoperatively), and an in-office sinonasal debridement at 1 week and 3 weeks after surgery [8].

V. Outcomes

The primary outcome was mean change in disease-specific QoL using the Sinonasal Outcome Test-22 (SNOT-22) [9]. Secondary outcomes included endoscopic grading using the Lund-Kennedy standardized scoring system, disease-specific medication usage within the previous 90 days, and work days missed in the previous 90 days [10, 11].

All data was collected using survey evaluations. Baseline data was collected at the time of enrollment. Continued medical therapy outcomes were collected at a follow up visit 2 weeks prior to receiving ESS. ESS outcomes were collected at 6 and 12 months after ESS (Figure 1).

VI. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata statistical software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviation, ranges and frequencies) and distributions were assessed for all outcome variables. Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests were used to test for significant changes between baseline versus continued medical therapy and continued medical therapy versus ESS mean SNOT-22 scores, endoscopy scores, medication consumption and work days lost. Pooled variance estimates were used to compare the changes in the continued medical therapy and ESS outcomes. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 31 patients with refractory CRS who elected ESS were enrolled between August 2011 and June 2013. Table 1 outlines the cohort characteristics. The mean baseline SNOT-22 score was 57.6 (17.1). The mean duration of continued medical therapy prior to ESS was 7.1 months (range 3 to 11.5 months). The mean duration of post operative follow up was 14.6 months (range 5 to 21 months) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for cohort with refractory CRS

| Characteristic | n = 31 |

|---|---|

| Gender | Female – 19 (59%) Male – 12 (41%) |

| Age | Mean = 45 .3 years (Range: 20 to 65) |

| Asthma | 12 (39%) |

| Allergy | 10 (33%) |

| ASA Intolerance | 3 (10%) |

| Smoker | 3 (10%) |

| Nasal Polyposis | 4 (12.5%) |

| Primary ESS | 25 (81%) |

| Sinus CT score (Lund-MacKay) | Mean = 13.5 (Range: 4 to 24) |

ASA, acetylsalicyclic acid; ESS, endoscopic sinus surgery; CT, computed tomography

I. Continued Medical Therapy Outcomes

There was an absolute mean worsening of 8.5 points between baseline and preoperative visit SNOT-22 scores, 57.6 to 66.1 (p=0.006). Endoscopic scores also worsened by 0.8 points, 6.9 to 7.7 (p=0.001). There was an increase in work days missed by 3.6 days within the preceding 90 days, 2.5 to 6.1 (p=0.007). The only significant change in medication consumption was an increase in the use of off-label high-volume topical steroid therapy (budesonide irrigations) (p<0.001) and a decrease in the use of low-volume topical intranasal steroid sprays (p=0.004). Outcomes following continued medical therapy are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Continued medical therapy outcomes: comparison between baseline and preoperative visit

| Outcome | Mean baseline (SD) | Mean preoperative (SD) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNOT-22 | 57.6 (17.1) | 66.1 (18.4) | 0.006 |

| Endoscopic Scores | 6.9 (2.7) | 7.7 (2.9) | 0.001 |

| Work Days Missed | 2.5 (5.3) | 6.1 (9.0) | 0.007 |

| Medication Consumption | |||

| Topical Intranasal Steroid spray | 46.5 (36.3) | 22.3 (34.3) | 0.004 |

| Budesonide Irrigations | 17.4 (25.5) | 53.1 (35.1) | <0.001 |

| Decongestant | 4.8 (10.9) | 8.5 (19.9) | 0.362 |

| Systemic Antibiotics | 16.0 (21.1) | 16.4 (23.2) | 0.718 |

| Systemic steroids | 8.7 (7.6) | 8.2 (6.1) | 0.852 |

| Antihistamine | 10.4 (25.9) | 10.0 (21.6) | 0.887 |

| Leukotriene receptor antagonist | 11.6 (28.6) | 15.0 (29.7) | 0.196 |

| Sinonasal Irrigations | 46.0 (33.4) | 60.0 (33.3) | 0.021 |

SNOT, sinonasal outcome test; SD, standard deviation

II. Endoscopic Sinus Surgery Outcomes

With a mean follow-up of 14.6 months after ESS, there was a statistically significant improvement in the mean SNOT-22 score of 50.1 points, 66.1 to 16.0 (p<0.001). Endoscopic scores improved by 5.3 points, 7.7 to 2.4 (p<0.001) and there was an absolute mean reduction in work days missed of 5.9 days, 6.1 to 0.2 (p<0.001). There was a significant reduction in the consumption of topical decongestants, systemic antibiotics, systemic steroids, and systemic antihistamines (all p<0.05). Outcomes following ESS are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Endoscopic Sinus Surgery Outcomes: Comparison between preoperative visit and postoperative outcomes

| Outcome | Mean Preoperative (SD) | Mean Postoperative (SD) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNOT-22 | 66.1 (18.4) | 16.0 (13.0) | <0.001 |

| Endoscopic Scores | 7.7 (2.9) | 2.4 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Work Days Missed | 6.1 (9.0) | 0.2 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Medication Consumption | |||

| Topical Intranasal Steroid spray | 22.3 (34.3) | 7.1 (21.4) | 0.025 |

| Budesonide Irrigations | 53.1 (35.1) | 51.1 (36.1) | 0.952 |

| Decongestant | 8.5 (19.9) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.002 |

| Systemic Antibiotics | 16.4 (23.2) | 0.6 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Systemic steroids | 8.2 (6.1) | 1.2 (3.9) | <0.001 |

| Antihistamine | 10.0 (21.6) | 0.4 (1.8) | 0.008 |

| Leukotriene receptor antagonist | 15.0 (29.7) | 9.7 (27.3) | 0.066 |

| Sinonasal Irrigations | 60.0 (33.3) | 62.1 (30.6) | 0.665 |

SNOT, sinonasal outcome test; ESS, endoscopic sinus surgery; SD, standard deviation

III. Continued Medical Therapy versus Endoscopic Sinus Surgery

The mean changes in SNOT-22, endoscopic grading, and work days missed between the continued medical therapy and ESS time periods were compared to assess the comparative effect of each therapy (Table 4). Overall, patients received significant improvements in SNOT-22 scores, endoscopic scores, work days missed following ESS compared to the continued medical therapy time period (all p<0.05).

Table 4.

Comparison of mean changes in outcomes between continued medical therapy and ESS

| Outcome | Mean Change after Continued Medical Therapy (SD) | Mean change after ESS (SD) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNOT-22 | 8.5 (15.9) | −50.1 (20.0) | <0.001 |

| Endoscopic Scores | 0.8 (1.0) | −5.3 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Work Days Missed | 3.5 (8.2) | −5.9 (9.1) | <0.001 |

SNOT, Sinonasal Outcome Test; ESS, endoscopic sinus surgery; SD, Standard Deviation

Discussion

This was a prospective longitudinal crossover study examining the clinical impact of continued medical therapy compared to ESS for patients with refractory CRS who had severe reductions in their baseline disease-specific QoL. After 7.1 months of continued medical therapy this cohort received a significant worsening in QoL, endoscopy scores, and work days missed. In contrast, with a mean follow-up of 14.6 months after ESS, this same cohort received significant improvements in all outcomes including significant reductions in rescue systemic antibiotics and systemic steroid consumption. These results highlight the importance of ESS in CRS patients with severe reductions in baseline QoL and suggest that continued medical therapy in this cohort has limited benefit.

There is little debate that ESS is an effective intervention in appropriately selected patients with refractory CRS [12-15]. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that continued medical therapy is effective in appropriately selected patients [16-18]. To optimize the use of scarce health care resources and improve the value of physician recommended interventions, it is important to determine which CRS patient populations would benefit most from continued medical therapy versus ESS. This would not only reduce cost but also increase overall effectiveness, which results in increased value for money.

Recent studies have demonstrated that patients with refractory CRS self-select either continued medical therapy or ESS based on their baseline disease- specific QoL [1][2]. Patients with less reduction is their disease-specific QoL tended to opt for continued medical therapy while patients with severely reduced QoL tended to elect surgery. Results from a study by Smith et al. demonstrated that patients with less impacted baseline QoL tended to receive significant improvements with continued medical therapy [2]. Furthermore, the subset of patients with severely reduced baseline QoL who elected initial continued medical therapy failed to receive improvement and tended to crossover into ESS. However, the time to crossover was very short (< 3 months) and it is difficult to assess how they would have progressed with a longer duration of continued medical therapy. A recent study by Smith and Rudmik evaluated the impact of a longer duration of continued medical therapy (7 months) in refractory CRS patients with severely reduced baseline QoL and demonstrated significant worsening in QoL, endoscopy scores, and work days missed[3]. Evidence from these studies suggests that patients with refractory CRS who have mild reductions in their baseline QoL may benefit from a trial of continued medical therapy, however, this would likely be an ineffective strategy for patients with severely reduced baseline QoL.

Results from this prospective longitudinal crossover study have confirmed the conclusions that patients with refractory CRS who have severely reduced baseline QoL do not benefit from continued medical therapy and ESS provides significant improvements in all measured outcomes. Therefore, baseline disease-specific QoL appears to not only be an important factor for patients choice of intervention, but is also an important prognostic factor for clinical benefit following either continued medical therapy or ESS. It is important to note that there is no currently defined disease-specific QoL threshold for which patients gain more benefit from medical or surgical management compared to ESS, however, current evidence suggests that patients with a baseline SNOT-22 of 55 or higher are unlikely to receive improvements with continued medical therapy and ESS should be considered to optimize outcomes. Although disease-specific QoL is a relatively crude metric to stratify patients’ responsiveness to clinical interventions, there is ongoing research working to define CRS endotypes based on biomarkers which will likely play an important role in refining the clinical responsiveness to specific medical therapies and ESS [19, 20].

When interpreting the results from this study, there are limitations that should be considered. First, the sample size of our cohort is relatively small, due to the difficulties associated with studying this patient population, which decreases the ability to detect small changes in each group. However, since our primary end-point reached statistical significance with p<0.001 there was minimal risk of committing a type 1 error (i.e. falsely rejecting the null hypothesis). Secondly, since there is no current standardized protocol for continued medical therapy in patients with refractory CRS, therefore we adopted a pragmatic approach to best approximate current clinical practice and make the outcomes generalizable. As such, we cannot make any conclusions on any specific medical therapy approach, but merely make a conclusion that appropriate medical therapy for patients with severely affected QoL fails to provide clinical benefit. Thirdly, the length of follow up in our continued medical therapy arm was relatively short (7.1 months) and so we cannot comment on the long term effects of continued medical therapy in this cohort. Finally, the prospective design of this study did not allow for a ‘washout’ period between interventions and this raises the possibility that there may have been a carry over effect from medical therapy on some of outcomes following ESS. Ideally, this study would include a lengthy ‘washout’ period to reduce any possible influence of continued medical therapy on the outcome of ESS, but this is not ethically possible. Despite these limitations we feel the findings are strengthened by the prospective longitudinal crossover methodology and stringent data collection.

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that patient baseline disease-specific QoL is an important factor to consider when deciding to continue with medical therapy or recommend ESS. Our results suggest that when there is a severe reduction in baseline disease-specific QoL (SNOT-22 score greater than 55), continued medical therapy provides no additional benefit while ESS provides significant improvements in several important clinical outcomes. Surgeons should consider measuring disease-specific QoL in patients with refractory CRS as it might aid in the decision making-process.

Acknowledgments

Potential Conflict(s) of Interest:

Kristine A. Smith: None

Timothy L. Smith: Consultant for Intersect ENT Inc. (Menlo Park, CA). Grant support from NIH/NIDCD

Jess C. Mace: Grant support from the NIH/NIDCD

Luke Rudmik: None

References

- 1.Soler ZM, et al. Patient-centered decision making in the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(10):2341–6. doi: 10.1002/lary.24027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith TL, et al. Medical therapy vs surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis: a prospective, multi-institutional study. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1(4):235–41. doi: 10.1002/alr.20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith KA, Rudmik L. Impact of continued medical therapy in patients with refractory chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4(1):34–8. doi: 10.1002/alr.21238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenfeld RM. Clinical practice guideline on adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3):365–77. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soler ZM, et al. Antimicrobials and chronic rhinosinusitis with or without polyposis in adults: an evidenced-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3(1):31–47. doi: 10.1002/alr.21064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudmik L, et al. Topical therapies in the management of chronic rhinosinusitis: an evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3(4):281–98. doi: 10.1002/alr.21096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poetker DM, et al. Oral corticosteroids in the management of adult chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyps: an evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3(2):104–20. doi: 10.1002/alr.21072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudmik L, et al. Early postoperative care following endoscopic sinus surgery: an evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1(6):417–30. doi: 10.1002/alr.20072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopkins C, et al. Psychometric validity of the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34(5):447–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lund VJ, Kennedy DW. Staging for rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117(3 Pt 2):S35–40. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopkins C, et al. The Lund-Mackay staging system for chronic rhinosinusitis: how is it used and what does it predict? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(4):555–61. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith TL, et al. Determinants of outcomes of sinus surgery: a multiinstitutional prospective cohort study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142(1):55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macdonald KI, McNally JD, Massoud E. Quality of life and impact of surgery on patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;38(2):286–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhattacharyya N. Clinical outcomes after endoscopic sinus surgery. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;6(3):167–71. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000225154.45027.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bezerra TF, et al. Assessment of quality of life after endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;78(2):96–102. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942012000200015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ragab SM, et al. Impact of chronic rhinosinusitis therapy on quality of life: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Rhinology. 2010;48(3):305–11. doi: 10.4193/Rhin08.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ragab SM, Lund VJ, Scadding G. Evaluation of the medical and surgical treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis: a prospective, randomised, controlled trial. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(5):923–30. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200405000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khalil HS, Nunez DA. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD004458. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004458.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akdis CA, et al. Endotypes and phenotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis: a PRACTALL document of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(6):1479–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam M, et al. Clinical severity and epithelial endotypes in chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3(2):121–8. doi: 10.1002/alr.21082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]