Abstract

Tendon has a complex hierarchical structure composed of both a collagenous and a non-collagenous matrix. Despite several studies that have aimed to elucidate the mechanism of load transfer between matrix components, the roles of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) remain controversial. Thus, this study investigated the elastic properties of tendon using a modified shear-lag model that accounts for the structure and non-linear mechanical response of the GAGs. Unlike prior shear-lag models that are solved either in two dimensions or in axially symmetric geometries, we present a closed-form analytical model for three-dimensional periodic lattices of fibrils linked by GAGs. Using this approach, we show that the non-linear mechanical response of the GAGs leads to a distinct toe region in the stress-strain response of the tendon. The critical strain of the toe region is shown to decrease inversely with fibril length. Furthermore, we identify a characteristic length scale, related to microstructural parameters (e.g. GAG spacing, stiffness, and geometry) over which load is transferred from the GAGs to the fibrils. We show that when the fibril lengths are significantly larger than this length scale, the mechanical properties of the tendon are relatively insensitive to deletion of GAGs. Our results provide a physical explanation for the insensitivity for the mechanical response of tendon to the deletion of GAGs in mature tendons, underscore the importance of fibril length in determining the elastic properties of the tendon, and are in excellent agreement with computationally intensive simulations.

Keywords: Modeling, fibril length, extracellular matrix, decorin, proteoglycan

1. Introduction

Tendon is composed of collagen molecules that assemble into collagen fibrils, which then bundle to form fibers and then fascicles. In addition, collagen fibrils are surrounded by a non-collagenous matrix, which consists of water and proteoglycans with their associated protein core and glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains. Proteoglycan core proteins bind to collagen fibrils while their GAG chains span between the fibrils and can bind with other GAG chains or proteoglycan core proteins on the adjacent fibril (Scott and Hughes, 1986; Scott et al., 1981; Vesentini et al., 2005). The structural arrangement of tendon components suggests that both collagen fibrils and the non-collagenous matrix may play a role in stress transfer during uniaxial loading, though the actions of each component and their interactions are not fully established (Ansorge et al., 2012; Connizzo et al., 2013; Fessel and Snedeker, 2009; Lujan et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2012a; Miller et al., 2012b; Miller et al., 2012c; Provenzano and Vanderby, 2006).

Several studies have examined tendon's collagenous matrix as a contributor to load transfer (Chen et al., 2009; Fratzl et al., 1998; Hansen et al., 2010; Robinson et al., 2004a; van der Rijt et al., 2006; Watanabe et al., 2007). In particular, some studies have shown that collagen fibrils are functionally continuous in adult tendon (Craig et al., 1989; Parry et al., 1978; Provenzano and Vanderby, 2006), suggesting that this may be the dominant mechanism of load transfer (Provenzano and Vanderby, 2006). Others have evaluated the tendon's non-collagenous matrix, indicating the GAGs as a potential mechanism for load transfer. The structure and relative movements of stained GAGs during mechanical relaxation tests suggest interfibrillar force transfer through a ratchet mechanism (Cribb and Scott, 1995; Watanabe et al., 2007; Watanabe et al., 2012). However, studies with enzymatic removal of GAGs have provided conflicting evidence concerning the role of GAGs in tendon mechanics (Fessel et al., 2012; Fessel and Snedeker, 2009, 2011; Lujan et al., 2007; Lujan et al., 2009). Moreover, studies involving transgenic animals are controversial, with varied results in different species, tendons, and even regional variations within tendon (Connizzo et al., 2013; Dourte et al., 2012; Dunkman et al., 2013; Elliott et al., 2003; Robinson et al., 2005; Robinson et al., 2004b).

Although collagen's contribution to tendon mechanical properties has been studied extensively (Gautieri et al., 2011, 2012; Heim et al., 2007; Svensson et al., 2010; van der Rijt et al., 2006), the role of GAGs remains unclear. Thus, several studies have used computational methods to model load transfer in the interfibrillar matrix (Fessel and Snedeker, 2011; Redaelli et al., 2003; Scott, 1992; Vesentini et al., 2005). Redaelli and colleagues evaluated the contribution of GAGs to stress transfer in tendons by introducing a piecewise linear GAG stiffness term in their micromechanical tendon fiber model (Redaelli et al., 2003). In particular, a multi-scale approach was utilized where the elastic properties of the GAGs were computed using molecular dynamics simulations in a 3D computational analysis to simulate stress-strain curves, as well as shear and tension profiles along the fibrils. The stress-strain curves show a clear nonlinearity in the stress-strain curve at 2% strain. While this work provides important insights into load transfer and also considers variation of parameters, the range of fibril lengths considered (50-300nm) is smaller than the typical length of fibrils (> 1mm) in adult tendon (Craig et al., 1989; Parry and Craig, 1984; Provenzano and Vanderby, 2006). In another study, Fessel and Snedeker developed a nice model containing a microstructure with randomly distributed fibrils of different diameters (Fessel and Snedeker, 2011). Results of their study showed that deletion of 80% of GAGs has a small influence on mechanical properties. However, no physical arguments were presented for the insensitivity of the response to GAG density, and their experiments showed smaller changes than their simulations.

One computationally efficient approach that has not yet been considered is a shear-lag model (SLM), which focuses on the transfer of tensile stress from matrix to fiber via interfacial stresses and can describe tendon mechanics at many strain levels (Cox, 1952; Okabe et al., 2001; Xia et al., 2002). Given that tendon is a fiber-reinforced composite that primarily experiences uniaxial loading, the SLM may be a useful tool in predicting mechanics. The mechanical response of tendon may depend on a number of factors, including non-linear GAG mechanical properties, GAG density, and fibril geometry (length, diameter, and spacing). Running simulations to analyze this large parameter space can be time consuming, particularly for large fibril lengths. Having an analytical model that can predict the dependence of these parameters can obviate the need for expensive 3D simulations and also provide physical insights into the role of different load bearing components.

Therefore, the objective of this work was to investigate the contribution of structural elements to overall tendon mechanics using a modified SLM that accounts for 1) the piece-wise linear stiffness characteristics of GAGs (Redaelli et al., 2003), 2) three-dimensional effects, such as variations in the magnitude of load transfer that arise when a given fibril has different numbers of neighbors, and 3) changes in the length scales over which load is transferred as GAGs are deleted. By including these features that are not considered in SLMs developed to date, we aim to elucidate the mechanisms by which GAGs contribute to tendon mechanical properties, and to identify other contributors (fibril length, modulus, diameter, area fraction, nonlinear GAG mechanical properties, and GAG density) to tendon mechanics.

2. Model description and solution

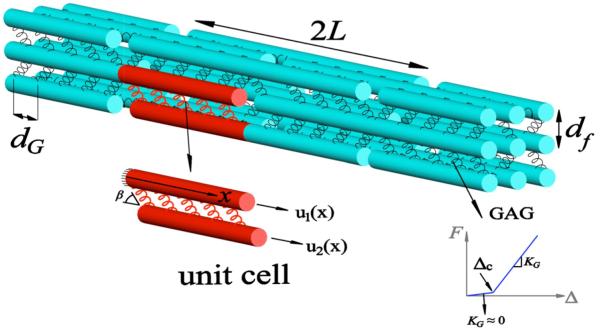

An SLM is implemented to describe the load transfer between fibrils and the GAGs. The model consists of uniform staggered fibrils interconnected with GAG cross-linkers that transfer the applied load via shear stress (Fig. 1). It is assumed that the fibrils are elastic with radius Rf (typically 75 nm (Robinson et al., 2004a; Scott et al., 1981; Watanabe et al., 2012)) and Young's modulus Ef (typically 1 GPa (Svensson et al., 2012; van der Rijt et al., 2006)). In addition, it is assumed that GAG tensile strain follows a bilinear spring-like behavior, as observed in molecular simulations (Redaelli et al. 2003). This behavior arises from the highly coiled force-free state of GAGs. When GAGs are stretched, they uncoil easily as this involves breaking of weak van der Waals/hydrogen bonds. Molecular simulations show that the stiffness associated with breaking these bonds is γG = 800% (Redaelli et al., 2003). Above this value of critical strain, the energy needed to alter the covalent bonding energies (bond length and angles) increases significantly, leading to a substantial increase in stiffness, KG = 0.031N/m (Redaelli et al., 2003). Since this stiffness is about six orders of magnitude larger than the stiffness in the coiled regime, we assume that KG ≈ 0 when the strain is less than the critical strain for uncoiling γG. Each fibril is surrounded by α near-neighbor fibrils, where an α value of 4 and 6 corresponds to square and hexagonal distributions in the 3D space, respectively. The spacing between the fibrils and GAGs are denoted by df and dG, respectively. Following Redaelli et al., dG = 68nm, corresponding to D-period length. Further, each GAG is attached to the fibril at an angle β (Fig.1). The parameters that characterize the tendon microstructure are summarized in Table 1. A uniform staggered structure of fibrils with length 2L interconnected with GAGs with α = 4 is shown in Fig. 1. The Cartesian coordinate system is placed at the center of each fibril such that the x-axis is oriented longitudinally along the fibril. A unit cell comprised of two neighbor fibrils (denoted by subscripts 1 and 2) with 0 ≤ x ≤ L is used to analyze load transfer between the fibrils and the GAGs.

Fig. 1.

The shear-lag model consists of fibrils (cyan) interconnected by GAGs (springs). A unit cell (red) with two neighboring fibrils is also shown. The force (F), elongation (Δ) behavior of the GAGs is also shown. Here, for Δ ≤ Δc, the stiffness is negligible, while KG denotes the stiffness when Δ > Δc.

Table 1.

List of symbols used in the modified shear-lag model.

| L | fibril half-length |

| Ef | fibril Young's modulus |

| df | fibril spacing |

| Rf | fibril radius |

| KG | GAG stiffness |

| dG | GAG spacing |

| γ g | GAG initial force-free elongation |

| β | GAG-fibril angle |

| l 0 | GAG- initial length |

| α | fibril number of the closest-neighbors |

| ϕ | fibril volume fraction |

The mechanical response is computed by imposing an overall strain on the structure and computing the resulting stress; specifically, we apply the boundary conditions u1(x = 0) = 0 and u2(x = L) = ε L. At the force-free ends of fibrils 1 and 2, the boundary conditions σ1(x = L) = Efdu1(x) / dx = 0 and σ2(x = 0) = Efdu2(x) / dx = 0 are applied. Since the GAGs with an initial length of l0 can stretch by an amount Δc = γGl0 without any applied force, the overall structure can sustain a critical strain below which the stress is zero. This critical strain can be obtained by equating the applied elongation, εcL, in the unit to the force-free elongation of the GAGs, which leads to the relation:

| (1) |

Note that this condition leads to a “toe” in the stress-strain curve that depends on the length of the fibrils and occurs at a larger value of overall strains when the fibrils are short. Beyond this critical level of strain, the stresses in the structure can be computed by modifying the SLM to account for the force-free elongation of the GAGs. By imposing the condition of mechanical equilibrium, the normal stress σ(x), and shear stresses τ(x) at the surface of each fibrils of the unit cell (subscripts 1 and 2) can be related through the conditions:

| (2) |

where the shear stress is determined by the extensions in the GAGs through the relation:

| (3) |

Combining Eqs. 2 and 3 and expressing σ(x) in terms of the displacements, the governing coupled ordinary differential equation(ODE) for the longitudinal displacements of the GAGs (ui(x), i = 1,2) can be obtained:

| (4) |

Here, the characteristic length over which the load is transferred from the GAGs to the fibrils (to be discussed below) is given by:

| (5) |

Note that here we have obtained this length scale in terms of the stiffness of the GAGs, their spacing, their orientation and the modulus and the size of the fibrils. The sensitivity of the mechanical response to the density of GAGs can be understood by studying the variation of this length scale with GAG spacing, dG.

Solving Eq. 4, subject to two traction-free and two displacement boundary conditions, displacement of a point x on the fibrils (Eq. 6) can be obtained as:

| (6) |

where

| (7) |

Using Eqs 6 and 2, the distributions of the normal and shear stresses on the fibril can be obtained:

| (8) |

| (9) |

These equations show that stress is transferred from the GAGs to the fibrils over a length scale of Lc. Finally, since the effective stress in the structure is the ratio of the average fibril force over the total cross-section area, the elastic modulus of the structure can be written as:

| (10) |

where ϕ denotes the area fraction of the fibrils (the ratio of the total fibril area and the total cross-sectional area). Further, Eq. 10 shows that the Young's modulus of the structure depends only on the normalized fibril length L / Lc and the critical strain εc = γGl0 / L, emphasizing that fibril length plays a crucial role in determining the mechanical response of the tendon. In the subsequent sections, the variation of each of these parameters on the overall behavior of the structure is evaluated.

3. Results

3.1: Validation of the current model with finite element simulations

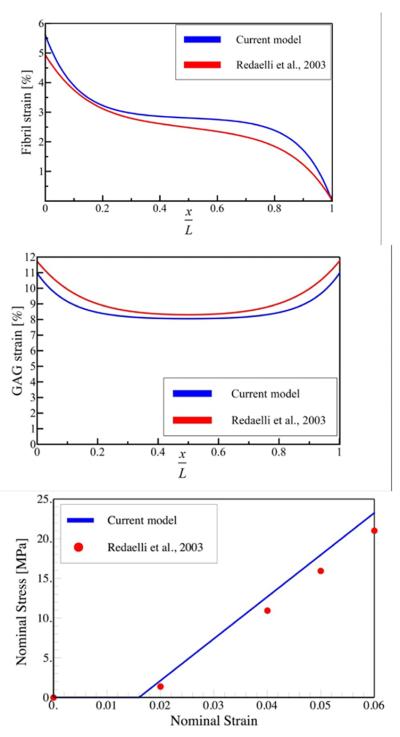

Several comparisons are made with previous studies based on finite element simulations of the tendon mechanical properties to validate our modified SLM. First, we compare our findings with the work of Redaelli and colleagues (Redaelli et al., 2003) who considered a structure similar to that shown in Fig. 1, but simulated the mechanical response by considering each GAG and fibril in their simulation unit cell (as opposed to the continuum approach we adopt here) using an energy minimization approach similar to the finite element method. For the largest unit cells used in their simulations, they had to keep track of 2200 GAGs. The strain distribution along the fibrils calculated with the numerical and analytical expressions (Fig. 2a,b) show that our closed-form expressions agrees very well with the predictions of the numerical approach. The stress-strain curves obtained from the two methods are shown in Fig. 2c. The position of the toe region observed in the simulations is captured well by our analytical approach. The small difference between stress-strain curves and stress profiles are due to the fact that the angle β varies continuously in the simulations, whereas we have assumed that it is constant. Accounting for the variation in β would make the theory nonlinear and an analytical solution would not be possible. Nonetheless, the close agreement between analytical theory and simulations suggests that our SLM is able to capture the key features of force transmission.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of the (a) normal and (b) shear strain along the fibril obtained from our modified shear-lag model and from the numerical work of Redaelli et al., 2003. x = 0 and x = L denote the center and the end of the fibril, respectively. The applied strain is ε = 0.05. The maximum normal strains at the point x = 0 from the analytical and numerical methods are 5.61% and 4.93%, respectively while minimum shear strains at point x = L / 2 are 8.05 and 8.30, respectively. (c) Stress-strain curves obtained from our modified shear-lag model and Redaelli et al., 2003. The parameters used in the simulations are l0 = df = 100 nm, Rf = 90 nm, 2L = 100 μm, α = 4, β = 60°, Ef = 2 GPa.

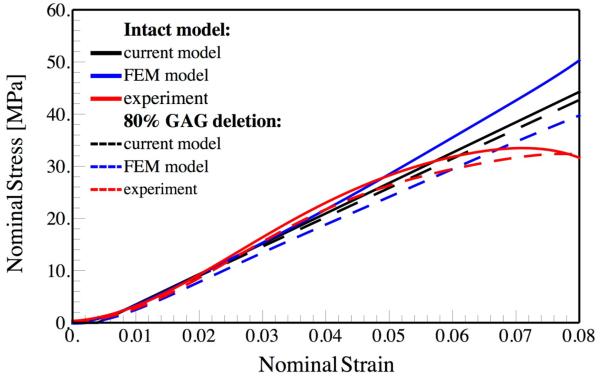

A second comparison shown in Fig. 3 is made with experimental and FEM analysis by Fessel and Snedeker in rat tail tendon fascicles, who again simulated a staggered microstructure of the tendon (similar to Fig. 1) by keeping track of each of the GAGs using FEM simulations (Fessel and Snedeker, 2011). As noted earlier, the maximum lengths of the fibrils considered in this study was 400 μm (Fessel and Snedeker, 2011), while the lengths of fibrils in mature tendons may be on the order of several millimeters (Birk et al., 1995; Provenzano and Vanderby, 2006). Note that for the case of short fibrils considered in the numerical work (Fessel and Snedeker, 2011), the authors had to keep track of 3000 GAGs, so a calculation of mechanical response of a mature tendon could require as much as ten times this number, making the computation significantly more demanding. Based on the TEM image of the cross-section of the tendon fascicle presented by Fessel and Snedeker, we have assumed that Rf = 90 nm and φ = 0.6. Our results are in excellent agreement with the experiments and the numerical simulations (Fig. 3). The experimental work shows softening in stiffness, which originates from the failure of the cross-linkers. In our current model and the numerical work presented by Fessel and Snedeker, failure of the fibrils and GAGs are not considered. Also, the toe region in the stress-strain curve is less prominent compared to that in Redaelli et al. We can understand this from our theoretical work (Eq. 1), which predicts that the toe in stress-strain curves scales inversely with the length of the fibril. Since the fibril length in the work of Fessel and Snedeker is larger than the fibril length in the work of Redaelli et al, the toe region occurs at a value of strain that is 4 times smaller, showing that our analytical theory captures the scaling of the toe region with fibril strain. In their work, Fessel and Snedeker also considered the effect of deleting GAGs, which we consider next.

Fig. 3.

Comparison between the current model, experiments and FEM analysis (Fessel and Snedeker, 2011) on both intact and 80% GAG depleted rat tail tendon samples. For the intact model, we use the parameters Rf = 90 nm, 2L = 400 μm, α = 6, Ef = 1.0 GPa, β = 60° and ϕ = 0.6 For the GAG depleted model, the spacing between GAGs has increased to dG = 340 nm.

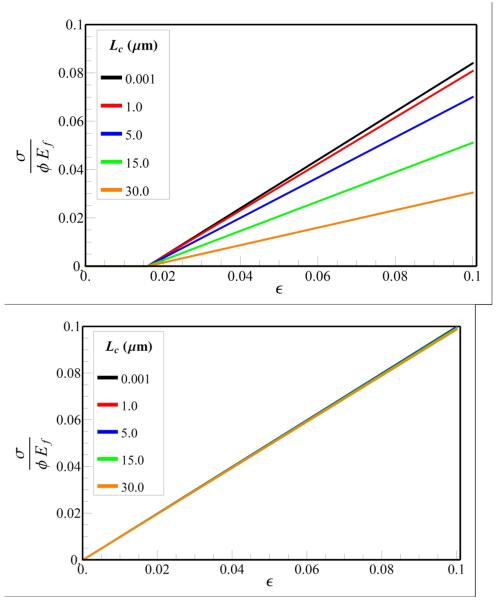

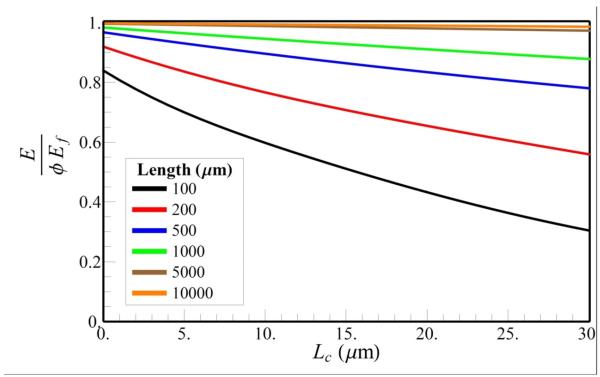

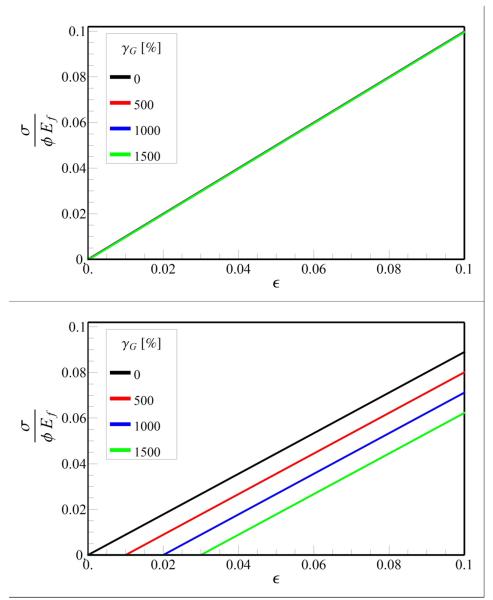

3.2: Effect of GAG digestion with different fiber lengths on the tendon Young's modulus

The effects of GAG digestion are evaluated by scaling the value of Lc by , where κ is the fraction of the GAG deletion, since the distance between the GAGs, dG, increases by this factor as GAGs are digested. Since the elastic modulus of tendon depends on Lc through the dimensionless parameter L / Lc (Eq. 10), we have plotted the stress-strain curves for tendons containing long (2L = 10000 μm) and short (2L = 100 μm) fibrils for different vales of Lc (Fig. 4). We find that when the fibril lengths are small, the stress-strain curves (Fig. 4a) are very sensitive to the value of Lc (and hence the density of GAGs), whereas the stress-strain curves are nearly independent of Lc for large fibril lengths (Fig. 4b). For example, assuming Ef = 1.0 GPa, R = 75nm, β = 60° and α = 4, Lc = 3.1 μm, by deleting 50% and 90% of GAGs (corresponding to Lc value of 5.5 and 13.5μm), the decrease in the total stiffness at strain ε = 0.1 is 7.5 and 19%, respectively for short fibril length, while for longer fibrils, GAG digestion in both cases only decreased the total stiffness by less than 0.5%. To examine the dependence of the elastic modulus of the tendon E on Lc, we varied the fibril lengths and GAGs densities (Fig 5). For fibril lengths greater than 5000 μm, the variation of E with the change in Lc (and hence the GAG density) is almost negligible (less than 2%). However, for fibrils approximately 500 μm in length, this difference ranges between10 and 40%. It should be noted that E increases with the increase in the value of L / Lc, and saturates at E /(ϕEf) = 1. For example, if Lc = 3.1 μm, then E /(ϕEf) ≥ 0.9 for a shorter fibril (L ≥ 150 μm) and, E /(E /(ϕEf) ≥ 0.99 for a longer fibril (L ≥ 2000 μm). These findings suggest that GAG digestion should have very little influence on the mechanical properties of the tendon when the fibril lengths are large. Indeed our prediction for the insensitivity of the mechanical properties of the tendon to deletion of GAGs is consistent with experimental observations of Fessel and Snedeker (Fig. 3).

Fig. 4.

Stress-strain curve for tendon with fibril lengths (a) 100 μm and (b) 10000 μm as a function of Lc (we setl0 = df = 100nm).

Fig. 5.

Variation of E / Efφ of the tendon with different fibril lengths at fixed applied strain, ε = 0.1 (we setl0 = df = 100nm).

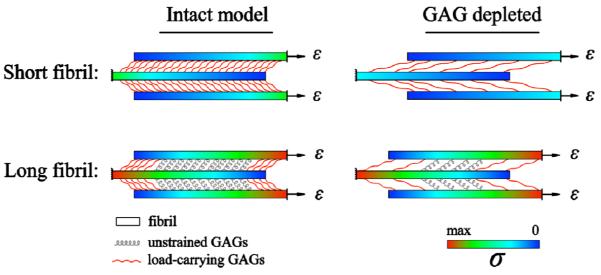

To gain a physical understanding of why the stiffness of tendons with long fibrils is insensitive to deletion of GAGs, we consider the stretch in a fibril as a function of the distance from its force-free end before and after GAG deletion in Fig 6. When the fibrils are long, the stress increases from the free end of the fibril over a length scale of Lc from a value of zero to the maximum value ~ Efε, at which points all the load is borne by the fibrils. Here the GAGs are strained only in the vicinity of the free ends of the fibrils over the same length scale, Lc. When GAGs are deleted, Lc increases but if L >> Lc, the load is still borne by the fibrils over a significant length (~ L). However, when L is comparable to or smaller than Lc, the load is primarily borne by the GAGs. Deleting the GAGs then leads to a significant drop in the elastic modulus of the tendon as the load-bearing components are digested.

Fig. 6.

The distribution of normal stress along the short and long fibrils for intact and GAG depleted models. The normal stress generated in the short fibrils is smaller compared to the in long fibrils. In addition, most of the GAGs in the long fibrils are unstrained, while for short fibrils all of the GAGs carry significant load and are elongated. As a result, deletion of GAGs in short fibrils results in removal of load-bearing elements and a reduction in the modulus, E. Alternatively, GAG deletion in long fibrils does not result in removal of significant load bearing elements over the lengths of the fibrils.

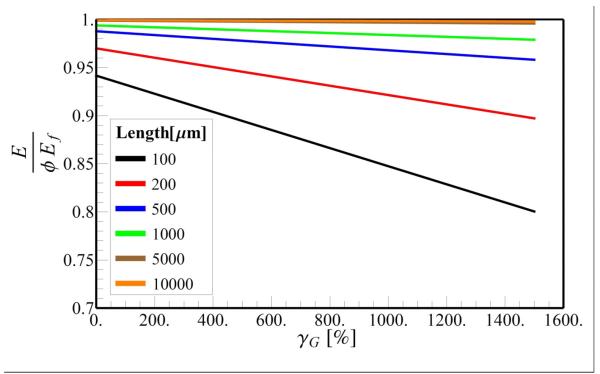

3.3: Effect of the GAG force-free elongation (γG) on the tendon Young's modulus

As noted previously, the elastic modulus of the tendon depends on two dimension-less parameters, L/Lc and εc. The latter depends on the GAG force-free elongation, which was estimated as 800 % from molecular simulations (Redaelli et al., 2003). This estimate depends on the details of the molecular interactions (which are only approximate) assumed in the simulations. Here we evaluate the importance of the force-free elongation γG on tendon mechanics. The stress-strain curves for long (2L = 10000 μm) and short fibrils (2L = 100 μm) as a function of the force-free strain are plotted in Fig. 7. The corresponding plot of the elastic modulus for different lengths of the fibrils is in Fig. 8. We find that the stress-strain curves for long fibrils are not sensitive to force-free elongation (Fig 7a), while the extent of the toe region increases with increasing values of γG for short fibrils (2L = 100 μm), (Fig 7b). Our simulations show that tendons with fibril lengths greater than 500 μm exhibit a change in E of less than 5% for 0≤γG≤1500% (Fig 8). However, for tendons containing short fibrils (2L = 100 μm), varying γG altered modulus to approximately 20%. These findings suggest that the dependence of the extent of the toe region and the Young's modulus on force-free strain γG is minimal for long fibrils and more significant for shorter fibrils.

Fig. 7.

Stress-strain curve for tendon with (a) long 2L = 10000 μm and (b) short 2L = 100 μm fibrils. The parameters Lc = 3.1 μm and l0 = df = 100nm are held fixed for all the curves.

Fig. 8.

Variation of the tendon Young's modulus for different fibril length as a function of force-free strain, γG. The parameters Lc = 3.1 μm and l0 = df = 100nm are held fixed and the applied strain is ε = 0.1.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to elucidate the mechanisms by which load is transferred in tendon using a modified SLM. Using previously reported values of fibril morphology and structure, we created a computationally efficient analytical model that approximates full tendon mechanical properties based on structural interactions, specifically between fibrils, interfibrillar matrix, and GAGs. Our model is able to predict the nonlinearity in the stress-strain curve of tendon, as well as give closed form expressions for the position of the toe region, the tension and shear stress profiles along the fibril, and the modulus, all as a function of microstructural parameters.

Results of this study agree with the findings of Fessel and colleagues that deletion of GAGs has a small influence on tensile quasi-static mechanical properties (Fessel and Snedeker, 2011). They considered a realistic microstructure with randomly distributed fibrils of different diameters, and showed that deletion of 80% of GAGs only had a small influence on mechanical properties, which was more pronounced in their experiments. Our model showed that GAG removal did not have an effect on simulations only when fibril lengths are large, providing a physical explanation for the dependence of GAG sensitivity on fibril lengths. In addition, our results (Fig. 2a,b) also agree with Redaelli and colleagues who developed a 3D computational method to simulate stress-strain curves and shear and tension profiles along fibrils (Redaelli et al., 2003). In addition, both models show nonlinearity in the stress-strain curve at 2 % strain (Fig. 2c). While the 2003 work provides insights into load transfer, the range of parameters considered (50-300nm) is smaller than the typical length of fibrils (> 1mm), which was evaluated in the current study. Finally, our results also agree with the work of Provenzano and Vanderby, which suggested fibril continuity may be the dominant role in load transfer in tendon (Provenzano and Vanderby, 2006).

Our study demonstrated that fibril length is a critical predictor of GAG sensitivity on mechanical properties. In adult tendons, collagen fibrils are very long (Provenzano and Vanderby, 2006), which could explain why several experimental studies that remove GAGs do not detect large differences in tendon mechanical properties. Our model provides a physical explanation for the insensitivity of mechanical properties in the limit of large fibril lengths. As the GAG density is reduced, load is transferred from one fibril to the other over a length scale inversely proportional with the square root of GAG density. In long fibrils, this length scale can be small compared to the fibril length even when 90% of GAGs are removed. However, when the fibrils are small, this length scale can be large compared to the fibril length, making mechanical properties sensitive to GAG removal.

While our model provides simple closed-form expressions for important parameters of tendon mechanics, this study is not without limitations. The effects of more sophisticated fibril morphology and movements, such as crimping, sliding, re-alignment, and bifurcations were not considered. Our simulation also treats the matrix as a single value, rather than the combination of a number of proteins that contribute to the tensile strength of the tissue. Finally, the primary finding that fibril length may determine the influence of GAGs on load transfer in tendon, is consistent with all available information, but has not been verified experimentally. Future studies will aim to confirm these results in development and injury, where fibrils may not be functionally continuous. In addition, we will explore other contributors to tendon mechanics such as viscoelasticity and fibril branching, re-alignment, sliding, and crimping. Yet, this is the first study to use a modified SLM to study the contributions of the collagenous and non-collagenous matrices to tensile mechanics in tendon using a realistic piece-wise linear model for the mechanical response of GAGs obtained from molecular simulations (Redaelli et al., 2003). In addition, we have provided a physical explanation to GAG insensitivity of the overall stress-strain response of the tendon that we plan to verify with future experimental studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Joseph Sarver and Dr. Mark Buckley for many valuable discussions. This study was supported by the NSF-CMMI-1312392, the NIH T32 AR556680, and the NSF GRFP.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Ansorge HL, Adams S, Jawad AF, Birk DE, Soslowsky LJ. Mechanical property changes during neonatal development and healing using a multiple regression model. J Biomech. 2012;45:1288–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birk DE, Nurminskaya MV, Zycband EI. Collagen fibrillogenesis in situ: fibril segments undergo post-depositional modifications resulting in linear and lateral growth during matrix development. Dev Dyn. 1995;202:229–243. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002020303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Wu PD, Gao H. A characteristic length for stress transfer in the nanostructure of biological composites. Composites Science and Technology. 2009;69:1160–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Connizzo BK, Sarver JJ, Birk DE, Soslowsky LJ. Effect of Age and Proteoglycan Deficiency on Collagen Fiber Re-Alignment and Mechanical Properties in Mouse Supraspinatus Tendon. J Biomech Eng. 2013 doi: 10.1115/1.4023234. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox H. The elasticity and strength of paper and other fibrous materials. British journal of applied physics. 1952;3:72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Craig AS, Birtles MJ, Conway JF, Parry DA. An estimate of the mean length of collagen fibrils in rat tail-tendon as a function of age. Connect Tissue Res. 1989;19:51–62. doi: 10.3109/03008208909016814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribb AM, Scott JE. Tendon response to tensile stress: an ultrastructural investigation of collagen:proteoglycan interactions in stressed tendon. J Anat. 1995;187(Pt 2):423–428. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dourte LM, Pathmanathan L, Jawad AF, Iozzo RV, Mienaltowski MJ, Birk DE, Soslowsky LJ. Influence of decorin on the mechanical, compositional, and structural properties of the mouse patellar tendon. J Biomech Eng. 2012;134:031005. doi: 10.1115/1.4006200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkman AA, Buckley MR, Mienaltowski MJ, Adams SM, Thomas SJ, Satchell L, Kumar A, Pathmanathan L, Beason DP, Iozzo RV, Birk DE, Soslowsky LJ. Decorin expression is important for age-related changes in tendon structure and mechanical properties. Matrix Biol. 2013;32:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DM, Robinson PS, Gimbel JA, Sarver JJ, Abboud JA, Iozzo RV, Soslowsky LJ. Effect of altered matrix proteins on quasilinear viscoelastic properties in transgenic mouse tail tendons. Ann Biomed Eng. 2003;31:599–605. doi: 10.1114/1.1567282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessel G, Gerber C, Snedeker JG. Potential of collagen cross-linking therapies to mediate tendon mechanical properties. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2012;21:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessel G, Snedeker JG. Evidence against proteoglycan mediated collagen fibril load transmission and dynamic viscoelasticity in tendon. Matrix Biol. 2009;28:503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessel G, Snedeker JG. Equivalent stiffness after glycosaminoglycan depletion in tendon--an ultra-structural finite element model and corresponding experiments. J Theor Biol. 2011;268:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratzl P, Misof K, Zizak I, Rapp G, Amenitsch H, Bernstorff S. Fibrillar structure and mechanical properties of collagen. J Struct Biol. 1998;122:119–122. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.3966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautieri A, Vesentini S, Redaelli A, Buehler MJ. Hierarchical structure and nanomechanics of collagen microfibrils from the atomistic scale up. Nano Lett. 2011;11:757–766. doi: 10.1021/nl103943u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautieri A, Vesentini S, Redaelli A, Buehler MJ. Viscoelastic properties of model segments of collagen molecules. Matrix Biol. 2012;31:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen P, Haraldsson BT, Aagaard P, Kovanen V, Avery NC, Qvortrup K, Larsen JO, Krogsgaard M, Kjaer M, Peter Magnusson S. Lower strength of the human posterior patellar tendon seems unrelated to mature collagen cross-linking and fibril morphology. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:47–52. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00944.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim AJ, Koob TJ, Matthews WG. Low strain nanomechanics of collagen fibrils. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:3298–3301. doi: 10.1021/bm061162b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lujan TJ, Underwood CJ, Henninger HB, Thompson BM, Weiss JA. Effect of dermatan sulfate glycosaminoglycans on the quasi-static material properties of the human medial collateral ligament. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:894–903. doi: 10.1002/jor.20351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lujan TJ, Underwood CJ, Jacobs NT, Weiss JA. Contribution of glycosaminoglycans to viscoelastic tensile behavior of human ligament. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:423–431. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90748.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K, Connizzo B, Soslowsky L. Collagen Fiber Re-Alignment in a Neonatal Developmental Mouse Supraspinatus Tendon Model. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2012a;40:1102–1110. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0490-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KS, Connizzo BK, Feeney E, Soslowsky LJ. Characterizing local collagen fiber re-alignment and crimp behavior throughout mechanical testing in a mature mouse supraspinatus tendon model. J Biomech Eng. 2012b;45:2061–2065. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KS, Connizzo BK, Feeney E, Tucker JJ, Soslowsky LJ. Examining differences in local collagen fiber crimp frequency throughout mechanical testing in a developmental mouse supraspinatus tendon model. J Biomech Eng. 2012c;134:041004. doi: 10.1115/1.4006538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okabe T, Takeda N, Kamoshida Y, Shimizu M, Curtin WA. A 3D shear-lag model considering micro-damage and statistical strength prediction of unidirectional fiber-reinforced composites. Composites Science and Technology. 2001;61:1773–1787. [Google Scholar]

- Parry DA, Craig AS. Growth and development of collagen fibrils in connective tissue. In: Ruggeri A, Motta PM, editors. Ultrastructure of the Connective Tissue Matrix. Martinus Nijhoff; Boston: 1984. pp. 34–64. [Google Scholar]

- Parry DA, Craig AS, Barnes GR. Tendon and ligament from the horse: an ultrastructural study of collagen fibrils and elastic fibres as a function of age. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1978;203:293–303. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1978.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzano PP, Vanderby R., Jr. Collagen fibril morphology and organization: implications for force transmission in ligament and tendon. Matrix Biol. 2006;25:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redaelli A, Vesentini S, Soncini M, Vena P, Mantero S, Montevecchi FM. Possible role of decorin glycosaminoglycans in fibril to fibril force transfer in relative mature tendons--a computational study from molecular to microstructural level. J Biomech. 2003;36:1555–1569. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PS, Huang T-F, Kazam E, Iozzo RV, Birk DE, Soslowsky LJ. Influence of Decorin and Biglycan on Mechanical Properties of Multiple Tendons in Knockout Mice. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2005;127:181–185. doi: 10.1115/1.1835363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PS, Lin TW, Jawad AF, Iozzo RV, Soslowsky LJ. Investigating tendon fascicle structure-function relationships in a transgenic-age mouse model using multiple regression models. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004a;32:924–931. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000032455.78459.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PS, Lin TW, Reynolds PR, Derwin KA, Iozzo RV, Soslowsky LJ. Strain-rate sensitive mechanical properties of tendon fascicles from mice with genetically engineered alterations in collagen and decorin. J Biomech Eng. 2004b;126:252–257. doi: 10.1115/1.1695570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE. Supramolecular organization of extracellular matrix glycosaminoglycans, in vitro and in the tissues. FASEB J. 1992;6:2639–2645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE, Hughes EW. Proteoglycan-collagen relationships in developing chick and bovine tendons. Influence of the physiological environment. Connect Tissue Res. 1986;14:267–278. doi: 10.3109/03008208609017470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE, Orford CR, Hughes EW. Proteoglycan-collagen arrangements in developing rat tail tendon. An electron microscopical and biochemical investigation. Biochem J. 1981;195:573–581. doi: 10.1042/bj1950573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson RB, Hansen P, Hassenkam T, Haraldsson BT, Aagaard P, Kovanen V, Krogsgaard M, Kjaer M, Magnusson SP. Mechanical properties of human patellar tendon at the hierarchical levels of tendon and fibril. J Appl Physiol. 2012;112:419–426. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01172.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson RB, Hassenkam T, Hansen P, Peter Magnusson S. Viscoelastic behavior of discrete human collagen fibrils. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2010;3:112–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Rijt JA, van der Werf KO, Bennink ML, Dijkstra PJ, Feijen J. Micromechanical testing of individual collagen fibrils. Macromol Biosci. 2006;6:697–702. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200600063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesentini S, Redaelli A, Montevecchi FM. Estimation of the binding force of the collagen molecule-decorin core protein complex in collagen fibril. J Biomech. 2005;38:433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Imamura Y, Hosaka Y, Ueda H, Takehana K. Graded arrangement of collagen fibrils in the equine superficial digital flexor tendon. Connect Tissue Res. 2007;48:332–337. doi: 10.1080/03008200701692800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Imamura Y, Suzuki D, Hosaka Y, Ueda H, Hiramatsu K, Takehana K. Concerted and adaptive alignment of decorin dermatan sulfate filaments in the graded organization of collagen fibrils in the equine superficial digital flexor tendon. J Anat. 2012;220:156–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2011.01456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z, Okabe T, Curtin WA. Shear-lag versus finite element models for stress transfer in fiber-reinforced composites. Composites Science and Technology. 2002;62:1141–1149. [Google Scholar]