Abstract

Introduction

Each SAARC nation falls in the zone of high incidence of pneumococcal disease but there is a paucity of literature estimating the burden of pneumococcal disease in this region.

Objective

To identify the prevalent serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease in children of SAARC countries, to determine the coverage of these serotypes by the available vaccines, and to determine the antibiotic resistance pattern of Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Methods

We searched major electronic databases using a comprehensive search strategy, and additionally searched the bibliography of the included studies and retrieved articles till July 2014. Both community and hospital based observational studies which included children aged ≤12 years as/or part of the studied population in SAARC countries were included.

Results

A total of 17 studies were included in the final analysis. The period of surveillance varied from 12–96 months (median, 24 months). The most common serotypes country-wise were as follows: serotype 1 in Nepal; serotype 14 in Bangladesh and India; serotype 19F in Sri Lanka and Pakistan. PCV-10 was found to be suitable for countries like India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, whereas PCV-13 may be more suitable for Pakistan. An increasing trend of non-susceptibility to antibiotics was noted for co-trimoxazole, erythromycin and chloramphenicol, whereas an increasing trend of susceptibility was noted for penicillin.

Conclusion

Due to paucity of recent data in majority of the SAARC countries, urgent large size prospective studies are needed to formulate recommendations for specific pneumococcal vaccine introduction and usage of antimicrobial agents in these regions.

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae or Pneumococcus claims 1 million child deaths every year worldwide [1]. Approximately 90% of these deaths occur in developing countries. A recent systematic analysis reported that, of 7.6 million deaths in children younger than 5 years in 2010, pneumonia accounted for 1.071 million (14·1%) deaths [2]. For every 1 child that dies of pneumonia in a developed country, more than 2000 children die of pneumonia in developing countries [3]. Besides pneumonia, S. pneumoniae causes a wide spectrum of diseases including pharyngitis, acute otitis media, joint effusions, meningitis, bacteremia and/or septicemia.

The SAARC (The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation) includes 8 countries: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, Maldives, and Afghanistan. The under-five mortality rates (per 1000 live-births) are high in these regions (ranging from 10 for Sri Lanka to 99 for Afghanistan) compared to the western countries (UK = 5, and USA = 7) as per the 2012 WHO data. The share of under-five deaths due to pneumonia in these regions is as follows: 20.4% in Afghanistan; 15% in India, 14.6% in Pakistan, 13.6% each in Nepal and Bhutan; 11% in Bangladesh, 8.8% in Maldives, and 5.7% in Sri Lanka [2], [4]. The SAARC nations also fall in the zone with high incidence of pneumococcal disease [1], but there is a dearth of studies reporting prevalent serotypes in these regions.

Different pneumococcal serotypes show different antibiotic sensitivity, and most of them are now resistant to the commonly prescribed antibiotics. Both, overuse of antibiotics and their over-the-counter availability have contributed to the increasing antibiotic resistance. In order to combat the increasing incidence of resistance as well as increasing disease prevalence, pneumococcal vaccines were made available as preventive tools. Since the availability of the first 23-valent-polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine (PPV-23) in 1977, many new conjugate vaccines (PCV-7, PCV-10, PCV-13) have been introduced and tested, but no single vaccine covers all 90 known pneumococcal serotypes [5]. These vaccines constitute those strains that cause 80% of the invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) and are resistant to antibiotics [5].

WHO-GAVI (World Health Organization & Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation) alliance has approved 3 conjugate vaccines PCV-7; PCV-10, and PCV-13 for use in children. These vary in the serotypes contained and the proteins used for conjugation. Vaccine serotypes are categorized based on the following vaccine preparations: 7 valent — 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F; 10 valent — 1, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F; and 13 valent — 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F, and 23F. The introduction of these vaccines in The United States (US) and Western Europe has decreased the incidence of vaccine strain associated invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) significantly. The GAVI alliance has also identified 75 low & middle-income countries that include the SAARC countries, to aid in vaccine introduction. The dilemma faced by SAARC countries is “which pneumococcal vaccine to introduce?” Pakistan is the only country from SAARC, where PCV-10 has been introduced with the help of GAVI alliance [6]. Both, estimates of pneumococcal disease burden along with antibiotic resistance pattern as well as knowledge about the prevalent serotypes are needed, to utilize the resources for child survival such as available vaccines and antibiotic therapy in other SAARC countries.

Methods

Types of studies

Observational studies (prospective, retrospective) reporting data on different S. pneumoniae serotypes obtained from normally sterile sites (e.g. blood, cerebrospinal fluid, pleural fluid) after at least 12 months of surveillance to avoid seasonal variation in reporting of the serotypes were included. The studies, commenting only on antibiotic resistance, without isolating the causative organism, were excluded. We also excluded case reports, editorials, vaccine studies, literature reviews and the studies in which nasopharyngeal aspirates, throat swabs or oro-pharyngeal swabs were the only samples to determine the causative organism.

Types of participants

Participants were children of both sexes and ≤12 years of age (excluding the neonates or young infants <2 months) as studied population in the SAARC countries.

Outcome measures

We intended to analyze the serotype distribution and pattern of antimicrobial resistance among S. pneumoniae isolates causing IPD in SAARC countries so as to provide guidance regarding immunization. So, the following outcomes of interest were measured.

Primary outcome

Prevalence of different invasive pneumococcal serotypes

Secondary outcome

Antibiotic resistance pattern of S. pneumoniae

Vaccine serotype coverage rate with currently available pneumococcal vaccines

Search methodology

We performed a systematic search of the published literature and also tried to acquire information about the unpublished literature from various investigators of the region. The searches were conducted from year 1970 to July 2014, and we identified articles with information on IPD among children ≤12 years of age. We searched following databases: Medline via Ovid, Pubmed, Embase and The Cochrane library (details of search strategy has been provided in Appendix S1). Non English articles were not included. Searches were carried out by two authors (NJ, RRD). After the search, each author was advised to screen the titles and abstracts for eligibility, and to retrieve full text articles. In case of any disagreement, a consensus was reached after discussion with the third author (MS). If the required data was not available we contacted the authors and tried to resolve discrepancies.

Data extraction

Authors abstracted data separately from the included studies in a predesigned proforma that included author, date of publication, country of study, study setting, population studied, type of study, source of isolates, serotypes isolated, time period of study, antibiotic susceptibility testing method, and antibiotic non-susceptibility rates. Susceptibility data were extracted for the following antibiotics where available: penicillin/ampicillin/amoxicillin, erythromycin, co-trimoxazole, chloramphenicol, ceftriaxone/cefotaxime, and ciprofloxacin. Non-susceptibility comprised of both intermediate and high level non-susceptibility. The proforma was pilot tested before extracting any study data following which data was abstracted separately for hospital-based and population-based studies. To resolve the discrepancies regarding the abstracted data, a consensus was made after discussion with the arbitor (MS).

Data analysis

After data extraction, all the relevant data was entered into Microsoft Excel. The percentages (%) of each serotype from similar studies of a country were combined together to find the ‘percentage incidence’ of that serotype for that country. We also combined the result from all the SAARC countries to find the most common serotype distribution and the most suitable of the three pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern was studied overall as well as in subgroups with respect to the country, age group, and time period of study, by taking an average estimate of the recent data from similar studies of a particular or all the SAARC countries.

Results

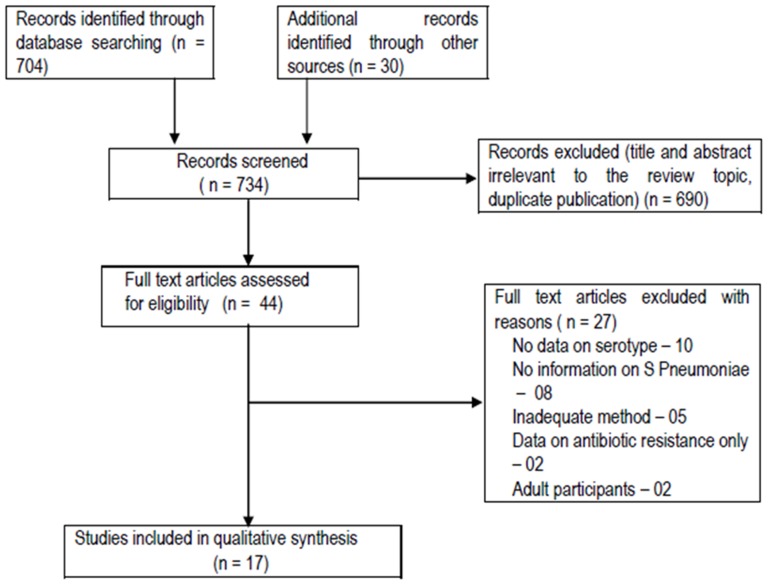

A total of 734 articles were retrieved, of which 44 articles were found eligible ( Figure 1 ). After going through the full text, we were able to include 17 studies ( Table 1 ) [7]–[23]. The reasons for exclusion of studies are mentioned in Table 2 . The data from two Indian studies [10], [11] were not included in the analysis of serotype data as they reported S. pneumoniae serogroups instead of serotypes. But the data from these two studies were included in other analyses. The studies included children ≤12 years of age, and spanned over a period of 22 years (1991–2013) with the surveillance period varying from 12 to 96 months (median, 24 months). Of the 17 included studies, 6 were from Bangladesh, 4 from Nepal, 4 from India, and 2 from Pakistan, and 1 from Sri Lanka. Thirteen were hospital based [7]–[11], [15]–[20], [22], [23], two (conducted in Bangladesh) were population based [13], [14], and two ware combined hospital and population based prospective studies [12], [21]. All the studies used culture and/or antigen detection method for isolation of the organism either from blood, CSF or both, and one study also used pleural fluid. We could not find any eligible studies from three other SAARC countries (Bhutan, Afghanistan and Maldives) to be included in the analysis.

Figure 1. Flow of study in the review.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

| Study ID | Settings | Country | Study period (year), duration (months) | Total children studied | No of S. Pneumoniae positive cases | Diagnosis method | Serotypes isolated | Sample used |

| Mastro et al, 1991 [7] | Hospital based prospective study | Pakistan | 1986–1989, 12 months | NA | 87 | Culture | 1, 5, 6a, 6B, 9V, 15C, 16, 19A, 19F, 31 | Blood |

| Saha et al, 1997 [8] | Hospital based prospective study | Bangladesh | 1992–1995, 36 months | NA (<5 yr age) | 165 | Culture and antigen testing | 1, 4, 7F, 12F, 14, 15B, 23F,18, 22A, 25, 16F, 6A, non-typeable | Blood and CSF |

| Saha et al, 1999 [9] | Hospital based prospective study | Bangladesh | 1993–1997, 48 months | NA (<5 yr age) | 362 | Culture and antigen testing | 1, 2, 5, 6, 7F, 9V, 12, 14, 15, 18, 19, 20, 33, 45 | Blood, CSF, ear, eye and pus swabs |

| IBIS Phase-I, 1999 [10] | Hospital based prospective study | India | 1993–1997, 48 months | 4348 (<12 yr age) | 156 (<12 yr age); 103 (<5 yr age) | Culture and antigen testing | 1, 6, 15, 7, 19, 5, 18,4, 23, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 29, 45, 24, 33, 2 | Blood and CSF |

| IBIS Phase-II, 2002 [11] | Hospital based prospective study | India | 2000–2001, 21 months | 1764 (<12 yr age) | 183 | Culture and antigen testing | 1, 6, 7, 19, 5, 4, 14, 18, 3 | Blood and CSF |

| Saha et al, 2003 [12] | Hospital and Population based prospective study | Bangladesh | 1999–2000, months | 2839 (<5 yr age) | 1301 (invasive = 91) | Culture and antigen testing | 2, 1, 14, 45, 5, 7, 12, 18, 19, 33, 6, 46 | CSF |

| Brooks et al, 2007[13] | Population based prospective study | Bangladesh | 2004–2006, 24 months | 6167 (<5 yr age) | 34 | Culture | 1, 10F, 12A, 12F, 14, 18A, 18C, 18F, 19A, 19F, 2, 23F, 25, 38, 4, 45, 5, 6B, 9V | Blood |

| Arifeen et al, 2009 [14] | Population based prospective study | Bangladesh | 2004–2007, 36 months | 22,378 (<5 yr age) (hospitalized = 2596) | 26 | Culture | 1, 5, 10F, 12A, 14, 18B, 18C, 19A, 35B, 38, 45 | Blood and CSF |

| Shah et al, 2009 [15] | Hospital based prospective study | Nepal | 2004–2007, 29 months | 2528 (<5 yr age) | 51 | Culture and antigen testing | 1, 5, 2, 7F, 12A, 14, 16, 18F, 19, 19B, 19F, 23F, 32, 39, 6B, non-typeable | Blood and CSF |

| Willams et al, 2009 [16] | Hospital based prospective study | Nepal | 2005–2006, 21 months | 885 (<5 yr age) | 17 | Culture and antigen testing | 1, 2, 5, 8, 12A, 16, 18C, 19A, 33, 35,42, non-typeable | Blood and CSF |

| Batuwanthudawe et al, 2009 [17] | Hospital based prospective study | Srilanka | 2005–2007, 26 months | 3642 (<5 yr age) | 23 | Culture and antigen testing | 19F, 14, 23F, 6B, 3, 16, 20, 29, 15B, 35, 42, non-typeable | Blood and CSF |

| Saha et al, 2009 [18] | Hospital based prospective study | Bangladesh | 2004–2007, 36 months | 17,969 (<5 yr age) | 139 | Culture and antigen testing | 2, 1, 14, 45, 5, 7F, 12A, 18C, 19A, 23F, 6A, 6B, 19F, 18F, 18A, 23A, 24, 29, 4, 20, 33F, 12F, 15B, 15A, 18A, 21, 23B, 3, 33B, 35F, 35A, 48, 8, 9V, 16F, 10F | Blood and CSF |

| Rijal B et al, 2010 [19] | Hospital based prospective study | Nepal | 2004–2008, 50 months | 3774 | 60 | Culture and antigen testing | 1, 39, 5, 16, 32, 2, 14, 18F, 23F, 7F, 19B, 12A, 19F, 6B, 25F | Blood, CSF and pleural fluid |

| Kelly et al, 2011 [20] | Hospital based prospective study | Nepal | 2005–2006, 21 months | 2039 (≤12 yr age) | 22 | Culture and antigen testing | 1, 12A, 5, 9A, 9V, 2, 8, 15A, 16, 18C, 19A, 19C, 23B, 25F, 33, non-typeable | Blood and CSF |

| Manoharan et al, 2013 [21] | Hospital/community based prospective study | India | 2-11-2013,? 24 months | 3572 (<5 yr age) | 225 | Culture and antigen testing | 14, 5, 1, 19F, 6B, 2, 7B, 7C, 8, 9A, 10A, 10F, 12F, 15A, 15B, 15C, 15F, 16F, 17F, 18A, 18B, 18F, 19B, 21, 23A, 24A, 24F, 25A, 27, 28F, 31, 33A, 33B, 33F, 34, 35A, 35B, 35F, 36, 38, 45, 6C | Blood, CSF and pleural fluid |

| Shakoor et al, 2013 [22] | Hospital/community based prospective study | Pakistan | 2005–2013,? 96 months | 72 (<5 yr age) | 111 | Culture and antigen testing, PCR | 18A, 18B, 18C, 18F, 14, 19F, 23B, 12F, 12A, 44, 46, 5, 9V, 9A, 1, 15B, 15C, 10A, 6A, 6B, 6C, 4, 23F, 19A, 17, 8, 24A, 24B, 24F, 33F, 33A, 37, 35B, 11A, 11D, 22A, 22F, 5, 23A, 23F, 3, 10F, 10C, 33C, 35B, 7A, 7F, 13, 38, 25F, 25A; no-typeable | Blood, CSF and pleural fluid |

| Kumar et al, 2013 [22] | Hospital/community based prospective study | India | 2-11-2013,? 24 months | 3572 (<5 yr age) | 225 | Culture and antigen testing | 1,; 3; 4; 5; 6; 9; 10; 14; 15; 18; 19 | Blood, CSF and pleural fluid |

NA: Not available, CSF: Cerebro-spinal fluid, Numbers in brackets includes references

Table 2. Excluded studies.

| Study name | Reasons for exclusion |

| Patwari et al, 1988 | No available data on causative organism |

| Mastro et al, 1993 | Study period is <1 year; Nasopharyngeal aspirates only |

| Awasthi et al, 1997 | No data on S. pneumoniae |

| Saha et al, 1999 | Mentions about antibiotic resistance only |

| Jebaraj et al, 1999 | Nasopharyngeal colonization study |

| Bansal et al, 2002 | Study on adults |

| Acharya et al, 2003 | Does not report for S. pneumoniae |

| Mehta et al, 2003 | Tells about Antibiotic resistance only does not give the details of S. pneumoniae and other causative organism |

| Bansal et al, 2006 | Not reported S. pneumoniae so cannot be included |

| Bharti et al, 2006 | No information on S. pneumoniae |

| Hussain et al, 2006 | Cost of treatment study |

| Nizami et al, 2006 | Oropharyngeal aspirate only |

| SPEAR study, 2008 | Study does tell only about India but has included other regions which are not a part of SAARC. Randomized Control Trial |

| Agarwal et al, 2009 | Short report; No data for S. pneumoniae |

| Mathisen et al 2010 | Study on viruses |

| Zaidi et al, 2009 | No data on serotyping |

| Naheed et al, 2009 | No serotype data |

| Vishwanath et al, 2007 | No serotype data |

| Kabra et al, 2003 | No serotype data |

| Sahai et al, 2001 | No serotype data |

| Shameem et al, 2008 | No serotype data |

| Patwari et al, 1996 | No serotype data |

| Bahl et al, 1995 | No serotype data |

| Deivnayagam, 1992 | No serotype data |

| John et al, 1991 | Study on viruses |

| Thomas et al, 2013 | Included patients>18 yrs age |

| Saha et al, 2009 | No data on serotype |

| Owais et al, 2010 | No data on serotype |

Overall distribution of serotypes

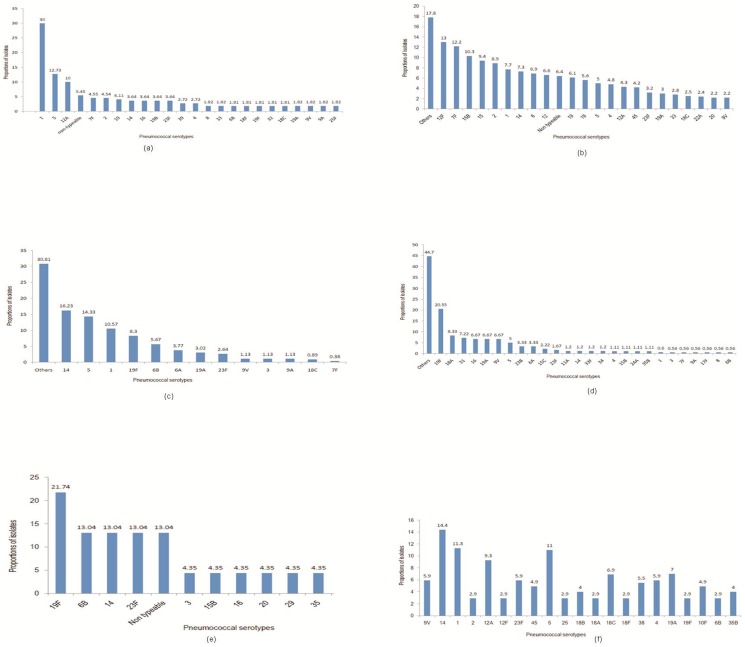

The combined result from all the SAARC countries showed the most common serotypes to be as follows: serotype 1 in Nepal; serotype 14 in Bangladesh and India; serotype 19F in Sri Lanka and Pakistan.

Hospital based studies

The combined data of the 4 studies from Nepal showed serotype 1 was most common followed by 5, and 12A ( Figure 2a ). Other vaccine serotypes 4, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F, and 23F were less common. Vaccine serotype 3 was not reported.

Figure 2. Combined serotype data from (a) Nepal; (b)Bangladesh (hospital based); (c): India; (d): Pakistan; (e): Sri Lanka (f): Bangladesh (population based).

The combined data of the 4 Bangladesh studies showed that “other serotypes” were most common. Among the identified ones, 12F, 7F, 15B, 15, 2, 1, and 14 were more common ( Figure 2b ). Other vaccine serotypes 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 9V, 18C, 19A, 19F, and 23F were less common. Vaccine serotype 3 was not reported.

The data from 2 Indian studies showed that “other serotypes” were most common. Among the identified ones, 14 was the most common followed by 5, 1, 19F, and 6B ( Figure 2c ). Other vaccine serotypes 6A, 19A, 23F, and 9V were less common. Only the vaccine serotype 4 was not reported.

The data from 2 Pakistan studies showed that “other serotypes” were most common. Among the identified ones, 19F was the most common followed by 18A, 31, 16, 19A, 9V, and 5 ( Figure 2d ). Other vaccine serotypes 1, 5, 6B, 14, and 23F were less common. Vaccine serotype 2 was not reported.

The data from 1 Sri Lankan study showed serotype 19F to be the most common followed by 6B, 14, 23F, and non-typeable ( Figure 2e ). Other vaccine serotypes 3, 15B, 16, 20, 29, and 35 were less common. Serotypes 1, 2, 4, 5, 6A, 7F, 9V, 18C, and 19A were not reported.

Population based studies

There were two population based prospective studies from Bangladesh [13], [14]. The combined data showed serotype 14 to be the most common, followed by 1, 5, 12A, 19A, and 18C ( Figure 2f ). Other vaccine serotypes 4, 6B, 23F, 9V, and 19F were less common. Vaccine serotypes 3, 6A, and 7F were not reported.

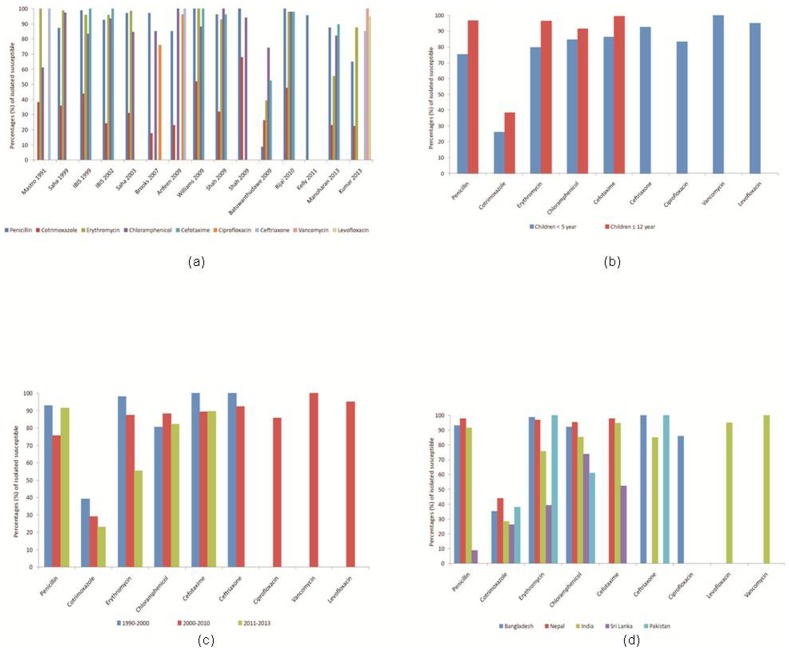

Antimicrobial susceptibility

Fifteen studies reported antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of various pneumococcal serotypes. Antimicrobial susceptibility rate of 100% was noted to vancomycin, 95% to levofloxacin, 85–100% to ceftriaxone; 9–98% to penicillin, 40–100% to erythromycin, 53–98% to cefotaxime; 61–95% to chloramphenicol, and 86% to ciprofloxacin. Resistance to co-trimoxazole varied from 56–74% in different studies ( Figure 3a ). Subgroup analysis was done according to the age and the period of study. The mean susceptibility rate was slightly less in children <5 years compared to ≤12 years ( Figure 3b ). We compared the mean susceptibility rate for three different time periods (1990–2000, 2001–2010, and 2011–2013). A decreasing trend (increased non-susceptibility) was noted for co-trimoxazole, erythromycin, and ceftriaxone; cefotaxime showed no change, whereas an increasing trend was noted for penicillin, and chloramphenicol ( Figure 3c ).

Figure 3. Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of S Pneumoniae (a) isolated from all the included studies; (B) Age wise; (C) Year wise; (d) Country wise.

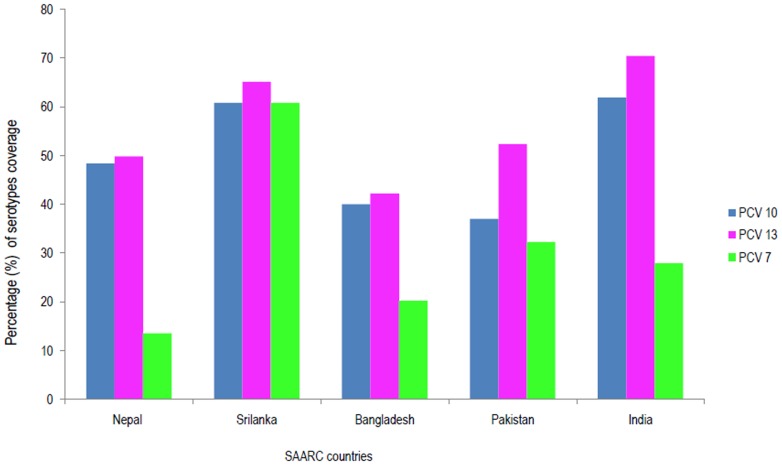

Vaccine serotype coverage

Based on the prevalent serotypes, we tried to estimate the percentage coverage of various pneumococcal vaccine serotypes in the SAARC countries ( Figure 4 ). PCV 13 (13-valent) was found to be more suitable for most of the SAARC countries as it covered three extra serotypes (3, 6A, and 19A) causing IPD compared to PCV 10 (10-valent) and six extra serotypes causing IPD compared to PCV 7 (7-valent). But if we take into account all the parameters including the prevalence of three vaccine serotypes covered by PCV-13 along with the cost as well as cross-protection against related serotypes, then the true difference between PCV-13 and PCV-10 will be minimal. The same has been discussed below in detail.

Figure 4. Pneumococcal vaccine coverage as per the serotype isolated (country-wise data).

Discussion

Summary of evidence

In the present study, we found the most common serotypes (country-wise) as follows: serotype 1 in Nepal; serotype 14 in Bangladesh and India; serotype 19F in Sri Lanka and Pakistan. Our results show that the cumulative burden of common non-vaccine serotypes (12A, 7, non-typeable, 12F, 15, 31, 2, 19B, 12, 9, 38, 15B, 16, 10F, 45, 35, 29, 18, and 18B) is equal or more than the cumulative burden of the vaccine serotype causing IPD in the SAARC countries. Our results are consistent with the previous systematic review in which the authors found 7 serotypes (1, 5, 6A, 6B, 14, 19F, 23F) to be the most common globally as per the data till July 2007 [24].

It is always a better idea to report the burden of pneumococcal disease separately for each country, so that a particular vaccine can be employed to target the common serotypes prevalent in that region. As shown in the result section, the hospital based data varied from country to country. From all these data, it is assumed that only 13-valent vaccine can cover most of the serotypes depending upon the country setting in SAARC region. Actually the difference between PCV-10 and PCV-13 would not be much if we consider the following points. First, PCV-13 covers three extra vaccine serotypes (3, 6A, and 19A). Serotype 3 has not been reported from two countries (Nepal, and Bangladesh), whereas the prevalence is less common in Pakistan (around 1%), India (1.8%) and Sri Lanka (4.3%). Second, there is substantial evidence for cross-reactivity among serotypes 6A and 6B. Third, emerging evidence also suggests cross-reactivity among serotypes 19A and 19F [25], [26]. The prevalence of serotype 19A is less common in three of the SAARC countries (Nepal = 1.8%, India = 4.8%, Bangladesh = 5%). Pakistan reports a prevalence of 12.5%, whereas Sri Lanka does not report it. Fourth, the cost of each dose of PCV-10 is almost half of that of PCV-10. But there is no published literature regarding the cost-effective analysis of PCVs in the SAARC region. Studies from other developing countries and developed countries conclude differently with some studies finding either PCV-10 [27] or PCV-13 [28], [29] or both [30]–[33] to be cost-effective. By taking into account of all these points, it seems that PCV-10 would be suitable for countries like India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan.

In a previous systematic review [24], combined data from Asian countries showed that the PCV-10 coverage is 70% (95% CI, 64%–75%), and the PCV-13 coverage is 75% (67%–79%). But the figures differ in the SAARC region. The strains covered in PCV-10 contribute on an average 50% of the IPD (varying from 37% in Pakistan to 62% in India), whereas the strains covered in PCV-13 contribute on an average 55% of the IPD (varying from 42% in Bangladesh to 70% in India), in the SAARC region, as per the present systematic review.

Although antibiotics play a crucial role in the management of pneumococcal infections, data on antibiotic susceptibility is limited in the SAARC region [24], [34]. In the present systematic review, we found a 100% susceptibility rate to vancomycin, and 95% to levofloxaicn. The sensitivity to ceftriaxone was around 92.5%. Resistance to co-trimoxazole varied from 56–74% in different studies. Sri Lanka was the only SAARC country reporting a high non-susceptibility rate of almost 90% to penicillin, 60% to erythromycin, 50% to cefotaxime, and 26% to chloramphenicol ( Figure 3d ). We also studied the mean antibiotic susceptibility rates in different subgroups. The mean susceptibility rate was slightly less in children <5 years compared to ≤12 years ( Figure 3b ). When we compared the mean susceptibility rates during three different time periods (1990–2000, 2001–2010, and 2011–2013), a decreasing trend (increased non-susceptibility) was noted for co-trimoxazole, chloramphenicol, and erythromycin; cefotaxime and ceftriaxone showed no change; whereas an increasing trend was noted for penicillin ( Figure 3c ).

Strengths & Limitations

The strength of present systematic review is the inclusion of a large number of studies spanning over more than 22 years period to estimate the average serotype distribution and pattern of antimicrobial resistance. Studies of short duration risk over- or underestimating serotype coverage due to inability to take into account the periodicity of serotypes [35]. Some of the limitations are common or inherent in systematic reviews in general, such as the potential for selection bias due to inclusion and exclusion criteria. In an effort to minimize the selection bias, we defined inclusion and exclusion criteria a priori to create a final data set aligned with our primary question of interest. We could not find any study from the three SAARC countries (Afghanistan, Maldives, and Bhutan), and only a single study was conducted each in Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Finally, some of the included studies were conducted almost a decade back during which the epidemiology of S. pneumoniae might have changed to a great extent.

Conclusions

Streptococcus pneumoniae causes substantial disease burden in the children of SAARC countries with a wide variation in prevalent serotypes and antibiotic resistance patterns. Due to paucity of recent data outlining serotypes causing IPD and pattern of antimicrobial resistance in majority of the SAARC countries, urgent large size prospective studies are needed to formulate recommendations for specific pneumococcal vaccine introduction and usage of antimicrobial agents in these regions. PCV-10 may be suitable for countries like India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, whereas PCV-13 may be more suitable for Pakistan.

Ethical Approval

An ethics statement was not required for this work.

Supporting Information

Details of searches for pubmed and embase.

(DOCX)

PRISMA Checklist.

(DOC)

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The review was supported and funded by ICMR, New Delhi (grant number 5/7/592/11-RHN). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. O'Brien KL, Wolfson LJ, Watt JP, Henkle E, Deloria-Knoll M, et al. (2009) Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet 374: 893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, Scott S, et al. (2012) Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 379: 2151–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (2006) World health statistics 2006. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available: http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat2006.pdf. Accessed: 2014 Aug 1.

- 4.Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group (CHERG). Underlying causes of child death. Available: http://cherg.org/projects/underlying_causes.html. Accessed: 2014 Aug 1.

- 5. Giebink GS (2001) The prevention of pneumococcal disease in children. N Engl J Med 345: 1177–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.GAVI Alliance. Pakistan tackles top child killer - Pneumonia. Available: http://www.gavialliance.org/library/audio-visual/videos/pakistan-tackles-top-child-killer---pneumonia/. Accessed: 2014 Jan 31.

- 7. Mastro TD, Ghafoor A, Nomani NK, Ishaq Z, Anwar F, et al. (1991) Antimicrobial resistance of pneumococci in children with acute lower respiratory tract infection in Pakistan. Lancet 337: 156–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saha SK, Rikitomi N, Biswas D, Watanabe K, Ruhulamin M, et al. (1997) Serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae causing invasive childhood infections in Bangladesh, 1992 to 1995. J Clin Microbiol 35: 785–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saha SK, Rikitomi N, Ruhulamin M, Masaki H, Hanif M, et al. (1999) Antimicrobial resistance and serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains causing childhood infections in Bangladesh, 1993 to 1997. J Clin Microbiol 37: 798–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thomas K (1999) IBIS group, INCLEN (1999) Prospective multicentre hospital surviellance of Streptococcus pneumoniae disease in India. The Lancet 353: 1216–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas K, IBIS Group, INCLEN. Prospective multicentre hospital surveillance of Streptococcus pneumoniae disease in India. Invasive Bacterial Infection Surveillance (IBIS) Group. Available: http://www.inclentrust.org/uploadedbyfck/file/publication/the%20inclen/Annex%201-IBISI%202 final. pdf. Accessed: 2013 Dec 24. [PubMed]

- 12. Saha SK, Baqui AH, Darmstadt GL, Ruhulamin M, Hanif M, et al. (2003) Comparison of antibiotic resistance and serotype composition of carriage and invasive pneumococci among Bangladeshi children: implications for treatment policy and vaccine formulation. J Clin Microbiol 41: 5582–5587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brooks WA, Breiman RF, Goswami D, Hossain A, Alam K, et al. (2007) Invasive pneumococcal disease burden and implications for vaccine policy in urban Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg 77: 795–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arifeen SE, Saha SK, Rahman S, Rahman KM, Rahman SM, et al. (2009) Invasive pneumococcal disease among children in rural Bangladesh: results from a population-based surveillance. Clin Infect Dis 48: S103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shah AS, Knoll MD, Sharma PR, Moisi JC, Kulkarni P, et al. (2009) Invasive pneumococcal disease in Kanti Children's Hospital, Nepal, as observed by the South Asian Pneumococcal Alliance network. Clin Infect Dis 48: S123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Williams EJ, Thorson S, Maskey M, Mahat S, Hamaluba M, et al. (2009) Hospital-based surveillance of invasive pneumococcal disease among young children in urban Nepal. Clin Infect Dis 48: S114–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Batuwanthudawe R, Karunarathne K, Dassanayake M, de Silva S, Lalitha MK, et al. (2009) Surveillance of invasive pneumococcal disease in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Clin Infect Dis 48: S136–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saha SK, Naheed A, El Arifeen S, Islam M, Al-Emran H, et al. (2009) Surveillance for invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae disease among hospitalized children in Bangladesh: antimicrobial susceptibility and serotype distribution. Clin Infect Dis 48: S75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rijal B, Tandukar S, Adhikari R, Tuladhar NR, Sharma PR, et al. (2010) Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern and serotyping of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated from Kanti Children Hospital in Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 8: 164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kelly DF, Thorson S, Maskey M, Mahat S, Shrestha U, et al. (2011) The burden of vaccine-preventable invasive bacterial infections and pneumonia in children admitted to hospital in urban Nepal. Int J Infect Dis 15: e17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manoharan A, et al. (2013) Surveillance of Invasive Disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae or Haemophilus influenzae or Neisseria meningitidis in Children (<5 years) in India. Abstract presented at the 31st meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Disease (ESPID). Available: www.asipindia.org/ESPID2013.pdf

- 22. Shakoor S, Kabir F, Khowaja AR, Qureshi SM, Jehan F, et al. (2014) Pneumococcal Serotypes and Serogroups Causing Invasive Disease in Pakistan, 2005–2013. PLoS ONE 9: e98796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kumar KLR, Ganaie F, Ashok V (2013) Circulating Serotypes and Trends in Antibiotic Resistance of Invasive Streptococcus Pneumoniae from Children under Five in Bangalore. J Clin Diagn Res 7: 2716–2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnson HL, Deloria-Knoll M, Levine OS, Stoszek SK, Freimanis Hance L, et al. (2010) Systematic evaluation of serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease among children under five: the pneumococcal global serotype project. PLoS Med 7: e1000348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hausdorff WP, Hoet B, Schuerman L (2010) Do pneumococcal conjugate vaccines provide any cross-protection against serotype 19A? BMC Pediatr 10: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Domingues CM, Verani JR, Montenegro Renoiner EI, de Cunto Brandileone MC (2014) Brazilian Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Effectiveness Study Group, et al (2014) Effectiveness of ten-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease in Brazil: a matched case-control study. Lancet Respir Med 2: 464–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gomez JA, Tirado JC, Navarro Rojas AA, Castrejon Alba MM, Topachevskyi O (2013) Cost-effectiveness and cost utility analysis of three pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in children of Peru. BMC Public Health 13: 1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Klok RM, Lindkvist RM, Ekelund M, Farkouh RA, Strutton DR (2013) Cost-effectiveness of a 10- versus 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Denmark and Sweden. Clin Ther 35: 119–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Earnshaw SR, McDade CL, Zanotti G, Farkouh RA, Strutton D (2012) Cost-effectiveness of 2 + 1 dosing of 13-valent and 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in Canada. BMC Infect Dis 12: 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Urueña A, Pippo T, Betelu MS, Virgilio F, Giglio N, et al. (2011) Cost-effectiveness analysis of the 10- and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in Argentina. Vaccine 29: 4963–4972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Castañeda-Orjuela C, Alvis-Guzmán N, Velandia-González M, De la Hoz-Restrepo F (2012) Cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines of 7, 10, and 13 valences in Colombian children. Vaccine 30: 1936–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ayieko P, Griffiths UK, Ndiritu M, Moisi J, Mugoya IK, et al. (2013) Assessment of Health Benefits and Cost-Effectiveness of 10-Valent and 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccination in Kenyan Children. PLoS ONE 8: e67324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim SY, Lee G, Goldie SJ (2010) Economic evaluation of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in The Gambia. BMC Infect Dis 10: 260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim SH, Song JH, Chung DR, Thamlikitkul V, Yang Y, et al. (2012) Changing trends in antimicrobial resistance and serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in Asian countries: an Asian Network for Surveillance of Resistant Pathogens (ANSORP) study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56: 1418–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ampofo K, Bender J, Sheng X, Korgenski K, Daly J, et al. (2008) Seasonal invasive pneumococcal disease in children: role of preceding respiratory viral infection. Pediatrics 122: 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Details of searches for pubmed and embase.

(DOCX)

PRISMA Checklist.

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.