Abstract

Neuropathological symptoms of Alzheimer's disease appear in advances stages, once neuronal damage arises. Nevertheless, recent studies demonstrate that in early asymptomatic stages, ß-amyloid peptide damages the cerebral microvasculature through mechanisms that involve an increase in reactive oxygen species and calcium, which induces necrosis and apoptosis of endothelial cells, leading to cerebrovascular dysfunction. The goal of our work is to study the potential preventive effect of the lipophilic antioxidant coenzyme Q (CoQ) against ß-amyloid-induced damage on human endothelial cells. We analyzed the protective effect of CoQ against Aβ-induced injury in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) using fluorescence and confocal microscopy, biochemical techniques and RMN-based metabolomics. Our results show that CoQ pretreatment of HUVECs delayed Aβ incorporation into the plasma membrane and mitochondria. Moreover, CoQ reduced the influx of extracellular Ca2+, and Ca2+ release from mitochondria due to opening the mitochondrial transition pore after β-amyloid administration, in addition to decreasing O2 .− and H2O2 levels. Pretreatment with CoQ also prevented ß-amyloid-induced HUVECs necrosis and apoptosis, restored their ability to proliferate, migrate and form tube-like structures in vitro, which is mirrored by a restoration of the cell metabolic profile to control levels. CoQ protected endothelial cells from Aβ-induced injury at physiological concentrations in human plasma after oral CoQ supplementation and thus could be a promising molecule to protect endothelial cells against amyloid angiopathy.

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) is a chronic neurodegenerative pathology characterized by the proteolytic processing of the amyloid precursor protein to form amyloid peptide (Aβ), which aggregates into extracellular amyloid plaques to cause neurotoxicity and the progressive cognitive decline typical of the disease in a process known as the “amyloid cascade” [1]. However, evidence indicates that circulating soluble Aβ exerts biological effects in AD patients prior to neuronal injury, much earlier than the onset of cognitive deficits. Indeed, soluble circulating Aβ damages endothelial cells in asymptomatic Alzheimer's stages preceding Aβ deposition [2]. In this sense, circulating Aβ affects the blood brain barrier to compromise its permeability and integrity [3] while also impairing blood supply by damaging small blood vessels, weakening oxygen exchange and nutrient delivery [4].

The concept of endothelial injury preceding neuronal damage is reinforced, first, by the fact that endothelial cells are the first line of contact with circulating Aβ, second, by the observation that oxidative stress in cerebral blood vessels occurs when there is no evidence of Aβ deposition in cerebral parenchyma and blood vessels, and third, by the observation that endothelial cells are more sensitive to Aβ and its active fragment Aβ25–35 than neurons or smooth muscle cells [2], [5]–[7]. Indeed, both Aβ and Aβ25–35, exert a prominent pro-apoptotic and necrotic effect on endothelial cells by mechanisms that involve an increase in free cytosolic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) and reactive oxygen species such as O2 .− and H2O2 [5], [8]–[11]. Although the exact mechanism of Aβ-mediated [Ca2+]i entry into endothelial cells is not completely understood, there is evidence in neurons pointing to the formation of pores that cause instability at the plasma membrane and produce ion leakiness, thus mediating a robust calcium influx into the cell [12]–[14]. Furthermore, Aβ increases the level of free oxygen radicals that react with nitric oxide (NO) and produces oxidative/nitrosative stress that alters vascular function [15]. Increased O2 .− and H2O2 produced by dismutation of these radicals also induces the opening of the permeability transition pore (mPTP), a mitochondrial membrane channel involved in cell death, thus damaging mitochondria and inducing necrosis and apoptosis [16]–[18]. This damage is further reinforced by trafficking and accumulation of the Aβ peptide into mitochondrial cristae [19].

Recently, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in cardiovascular diseases, which are risk factors for AD in the elderly [20], provided evidence for effective treatment with the lipophilic antioxidant coenzyme Q10 (CoQ) to improve endothelial cell function [21]–[23]. Moreover, CoQ also prevented oxidative stress and calcium-mediated necrosis and apoptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) exposed to damaging and pro-oxidizing stimuli such as high glucose concentration, oxidized LDL or angiotensin II [24]–[27]. Finally, it is known that a ubiquinone binding site regulates the aperture of the mPTP [28] and that CoQ is effective at inhibiting mPTP opening triggered by H2O2 in epithelial cells [29].

Based upon these observations, here we explored the role of CoQ against Aβ injury in endothelial cells using microscopy, biochemistry and metabolomic approaches. Our results show that pretreatment of endothelial cells with physiological concentrations of CoQ delays Aβ incorporation into the plasma membrane and its trafficking to mitochondria, reduces ROS production and calcium influx while increasing NO levels. Moreover, CoQ treatment impedes mPTP opening and reduces necrosis and apoptosis, while also restoring cell migration, wound healing and cell tube formation to control conditions. CoQ blocks Aβ-induced changes in the endothelial metabolic profile. In sum, CoQ could be a promising molecule to treat endothelial dysfunction associated with early, asymptomatic AD stages in high-risk populations.

Results

CoQ prevents β-amyloid-induced endothelial cell death and restores migration and angiogenesis in vitro

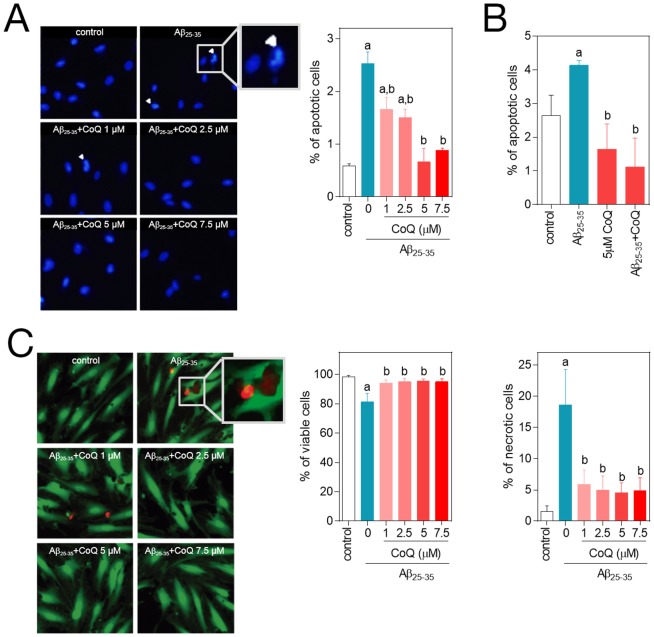

It was previously reported that cellular exposure to the amyloid fragment Aβ25–35 results in endothelial cell toxicity similar to β1–42, via inducing cell apoptosis and necrosis [5]. In our experiments we explored the effect of the Aβ25–35 fragment on cell death and the possible cytoprotective role of CoQ. The addition of 5 µM Aβ25–35 to HUVECs for 24 h increased the percentage of apoptotic nuclei from 0.5% to 2.6% (Figure 1A) and the percentage of Annexin V positive cells from 2.7% to 4.2%, (Figure 1B), indicating a modest but significant increase in apoptosis. A 12 h preincubation with CoQ resulted in a dose-dependent decrease of apoptotic nuclei, reaching control levels at 5 µM CoQ (Figure 1A), which was confirmed by flow cytometry determination of Annexin V (Figure 1B). The action of CoQ was cytoprotective, as cells needed to be pre-treated with the lipophilic antioxidant prior to Aβ25–35 addition for an observable effect. Simultaneous treatment with 5 µM Aβ25–35 and CoQ did not affect the percentage of apoptotic cells (Figure S1A). On the other hand, treatment with 5 µM Aβ25–35 produced an 18% decrease of HUVECs viability, which was mirrored by a similar increase in necrosis (Figure 1C). Preincubation with CoQ restored cell viability to control levels and prevented Aβ25–35 induced necrosis at all doses of CoQ tested (Figure 1C). We assayed the putative Aβ activation of neutral sphyngomielinase (nSMase), as previously described in neurons [30]. CoQ is also a potent antioxidant in plasma membrane [31] and we had previously demonstrated that higher CoQ levels in liver plasma membrane enhanced anti-oxidant protection by a mechanism involving the inhibition of nSMase [32]. However, Aβ did not activate nSMase in HUVECs (Figure S2).

Figure 1. CoQ protects endothelial cells from β-amyloid-induced apoptosis and necrosis.

HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with vehicle alone or with increasing CoQ concentrations (1 to 7.5 µM) and then treated for additional 24 h with 5 µM Aβ25–35. A) Apoptosis was determined by DAPI staining and morphological analysis of nuclei. White arrows indicate typical apoptotic nuclei. Results are expressed as the percentage of apoptotic vs. total nuclei (300 cells/treatment, n = 3). B) Apoptosis was also evaluated by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as percentage of cells positive for Annexin V vs. total (n = 3). Viability and necrosis (C, left and right, respectively) were determined by cell co-staining with calcein-AM (green) and ethidium bromide (orange) and evaluated by qualitative fluorescence microscopy. Results are expressed as percentage of viable/necrotic cells vs. total (n = 3). a, p<0.05 vs. control; b, p<0.05 vs. Aβ25–35.

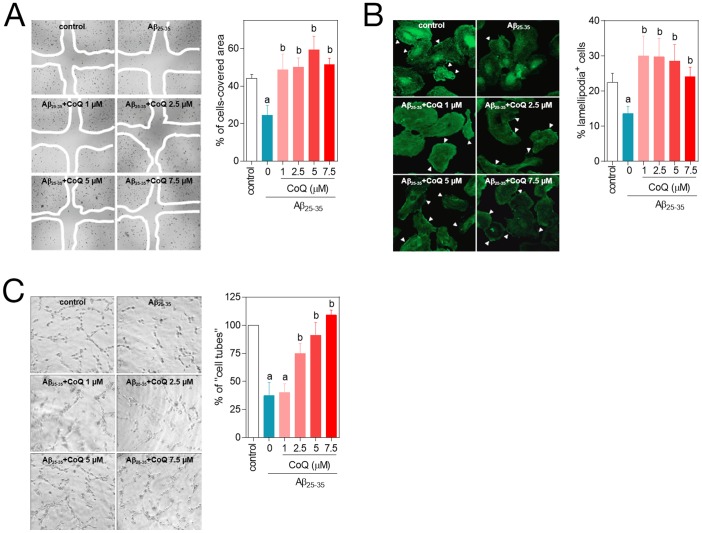

Aβ damages small blood vessels and impairs the blood supply in early Alzheimer's stages [4], while also increasing the permeability of the blood brain barrier [3] which reinforces the concept of an early endothelial degeneration in asymptomatic stages. There is also evidence suggesting that Aβ inhibits neovascularization in vitro [33], [34]. Thus, we tested the effect of CoQ on Aβ impaired angiogenesis in vitro, and also assaying effects on cell migration, a key step in vessel formation. Addition of Aβ resulted in a strong decrease in HUVECs migration, evaluated by a standard wound healing assay (Figure 2A), and similar results were obtained by quantifying lamellipodia positive (migrating) cells (Figure 2B). Pretreatment with CoQ completely abrogated the inhibitory effect of Aβ on HUVECs migration at all doses tested (Figures 2A,B). Similarly, Aβ produced a 60% reduction in the ability of HUVECs to form capillary-like cell tubes, and this effect was prevented by pretreatment with CoQ in a dose-dependent manner, (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. CoQ hinders β-amyloid inhibition of endothelial cells migration and tubes formation.

HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with vehicle or increasing CoQ concentrations (1 to 7.5 µM) and treated for additional 24 h with 5 µM Aβ25–35. A) Cell migration was evaluated with the wound healing assay. Results show the percentage of wound recovered after 12 h for the indicated treatments (n = 3). B) Migrating cells were identified with fluorescence microscopy by immunostaining of lamellipodia structures with an anti-actin antibody. Results are expressed as percentage of lamellipodia+ cells (white arrows) cells vs. total (n = 3). C) Angiogenesis in vitro was determined by “cell tube” formation assays in Matrigel-coated wells. Results show the percentage of cell tubes vs. control after 6 h incubation with the indicated treatments (n = 3). a, p<0.05 vs. control; b, p<0.05 vs. Aβ25–35.

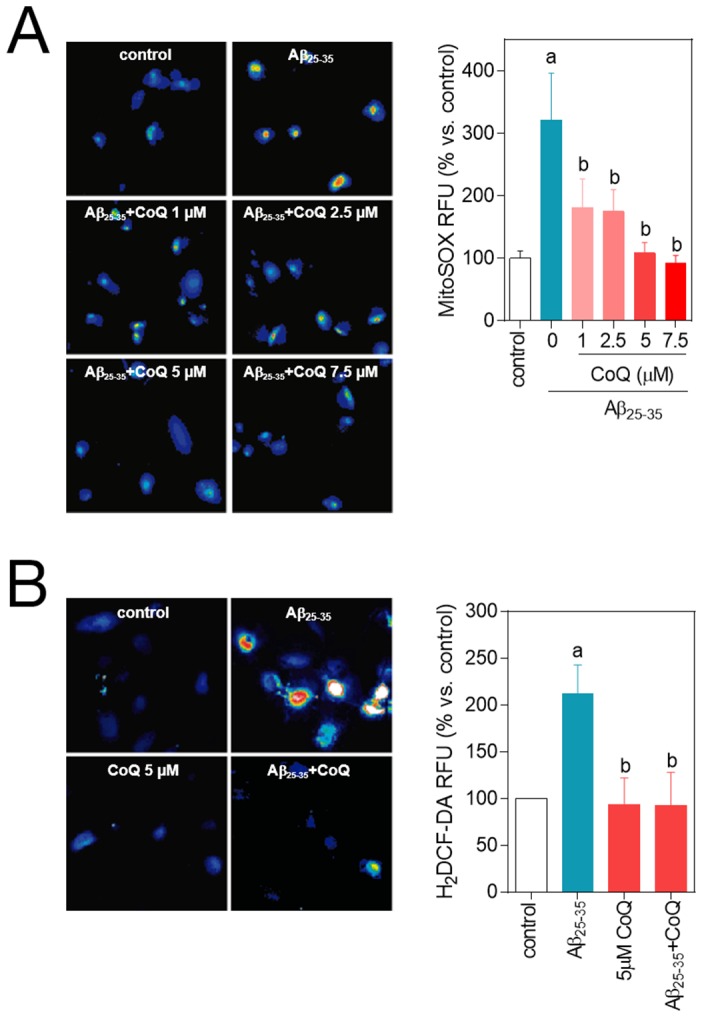

CoQ prevents β-amyloid-dependent increase of O2 .−, H2O2 and Ca2+ in endothelial cells

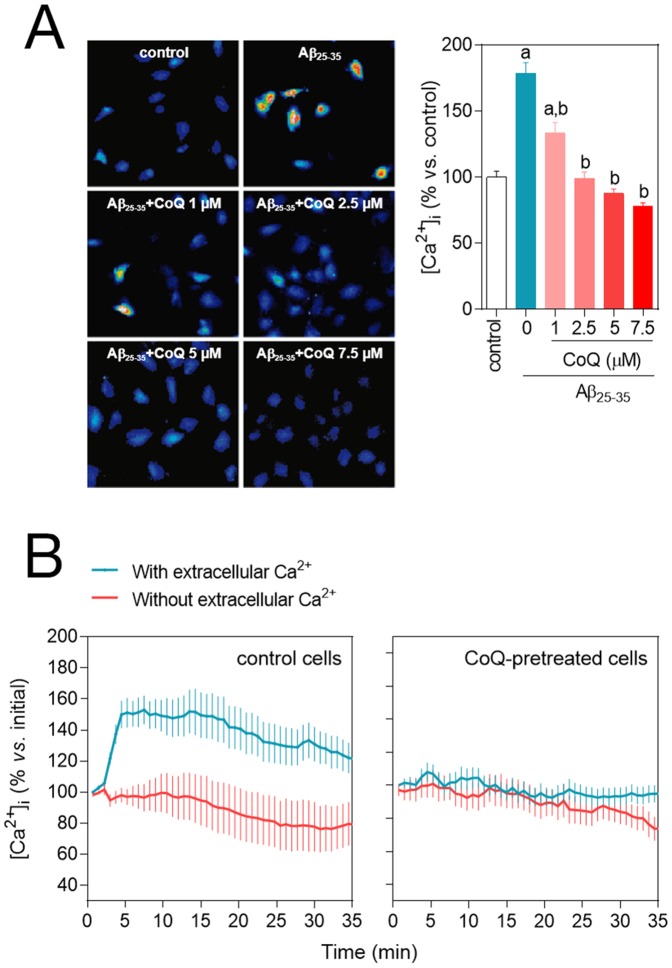

The deleterious effect of Aβ in endothelial cells is due to an excess of O2 .− and H2O2 and altered calcium homeostasis [1], [5], [35], [36]. Thus, our results demonstrated that administration of 5 µM Aβ25–35 to HUVECs increased O2 .− (3-fold) and H2O2 (2-fold) levels vs. the untreated controls (Figure 3A,B). CoQ alone did not affect the basal levels of reactive oxygen species or free cytosolic Ca2+. However, preincubation with CoQ abated Aβ25–35–dependent increase of O2 .− at all doses tested, reaching control levels at 5–7.5 µM CoQ (Figure 3A). Similarly, Aβ failed to increase H2O2 levels in HUVECs preincubated with 5 µM CoQ (Figure 3B). In parallel, we tested the effect of CoQ pretreatment on Aβ-induced changes of Ca2+ homeostasis in HUVECs. Administration of 5 µM Aβ25–35 for 3 h produced a 75% increase of Ca2+ levels compared with basal conditions. Preincubation with CoQ reduced Aβ-dependent Ca2+ increase at all tested doses (Figure 4A). Simultaneous treatment with 5 µM Aβ25–35 and CoQ resulted in a similar Ca2+ increase than that induced by Aβ alone (Figure S1B), indicating that CoQ needs to be previously incorporated into the cell to impede Aβ action.

Figure 3. CoQ prevents β-amyloid-mediated increase in O2 .− and H2O2 levels in endothelial cells.

HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with vehicle or increasing CoQ concentrations (1 to 7.5 µM) and treated for additional 24 h with 5 µM Aβ25–35. A) O2 .− levels were determined by fluorescence microscopy using the probe MitoSOX-AM. B) H2O2 level was determined by fluorescence microscopy with the probe H2DCF-DA. Results show the percentage of variation of fluorescence vs. control cells (n = 4). a, p<0.05 vs. control; b, p<0.05 vs. Aβ25–35.

Figure 4. CoQ blocks β-amyloid-induced raise in the free cytosolic Ca2+ level in endothelial cells.

HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with vehicle or CoQ (1 to 7.5 µM) and treated with 5 µM Aβ25–35. Ca2+ levels were determined by fluorescence microscopy with the probe Fluo-4-AM. A) Ca2+ was quantified after 3 h treatment with 5 µM Aβ25–35 in cells preincubated with CoQ. Results show the percentage of variation of fluorescence vs. control cells (n = 4). a, p<0.05 vs. control; b, p<0.05 vs. Aβ25–35. B) Changes in Ca2+ were monitored by time-lapse microscopy every 30 sec in cells pretreated with PBS (left graph) or 5 µM CoQ (right graph) in the presence (black line) or absence (grey line) of extracellular Ca2+. Aβ25–35 was added in min 1. Results show the averaged percentage of fluorescence variation vs. baseline before Aβ25–35 addition (n = 3).

CoQ prevents β-amyloid-induced entry of extracellular Ca2+ in endothelial cells

Though Aβ-mediated Ca2+ increase is well documented [5], [12], there is little study of the kinetics of this secondary messenger dynamics. To this end, we tested the effect of Aβ in control and CoQ pretreated cells using a real time approach. This technique revealed that the addition of 5 µM Aβ25–35 to control HUVECs induced a rapid Ca2+ increase from the extracellular media, reaching a maximum (150% above baseline) at 5 min from peptide administration (Figure 4B left, blue line). This Ca2+ increase was abolished by incubating the cells in Ca2+ free media (Figure 4B left, red line). Of note, extracellular Ca2+ entry induced by Aβ25–35 action was completely prevented in cells preincubated with 5 µM CoQ, as Ca2+ levels remained unaltered, with or without extracellular calcium (Figure 4B, right).

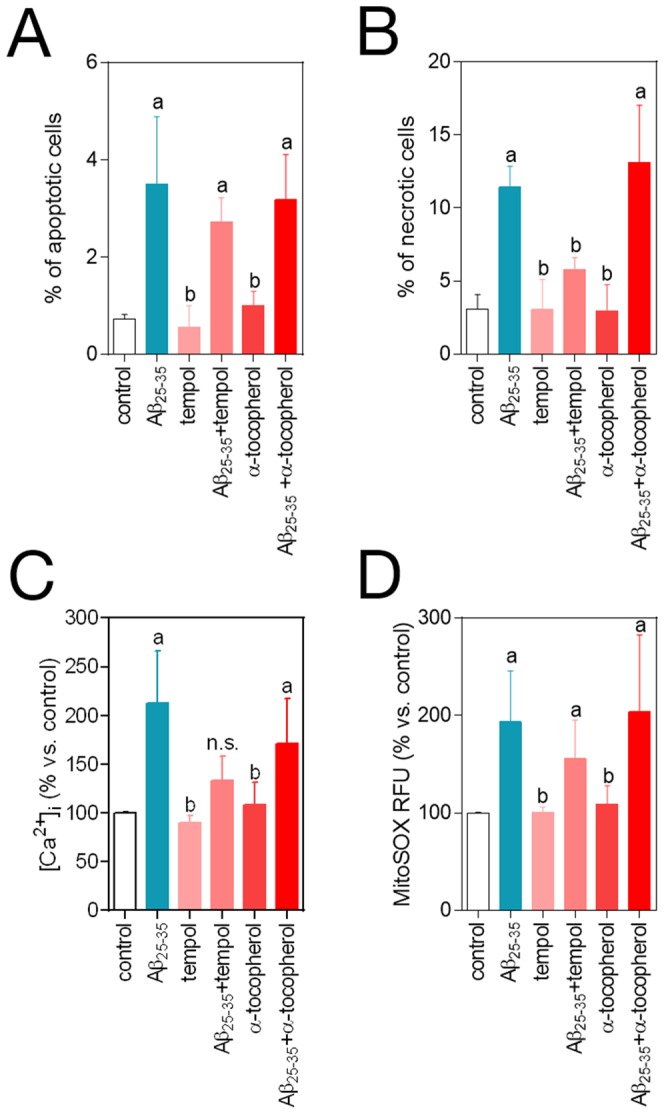

β-amyloid cytotoxic effects are not prevented by the antioxidants tempol and α-tocopherol

In order to test if the protective effects of CoQ were imparted by its antioxidant properties, we studied the action of the antioxidants tempol and α-tocopherol on cell death, Ca2+ and O2 .− levels. Preincubation with 1 mM tempol or 100 µM α-tocopherol did not inhibit apoptosis triggered by 5 µM Aβ25–35 (Figure 5A), whereas only tempol was able to inhibit necrosis without reaching control levels (Figure 5B). Preincubation with any of the compounds was unable to restore Ca2+ and O2 .−, obtaining only partial but not significant reductions in the case of tempol (Figure 5C, D).

Figure 5. Effects of tempol and α-tocopherol on β-amyloid-induced apoptosis, necrosis, free cytosolic Ca2+ and O2 .−.

HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with vehicle, 1 mM tempol or 100 µM α-tocopherol, and then treated for additional 3–24 h with 5 µM Aβ25–35. A) Apoptosis was determined by DAPI staining and morphological analysis of nuclei. Results are expressed as the percentage of apoptotic vs. total nuclei (300 cells/treatment, n = 3). B) Necrosis was determined by staining with ethidium bromide and evaluated by qualitative fluorescence microscopy. Results are expressed as percentage of necrotic vs. total cells (n = 3). a, p<0.05 vs. control; b, p<0.05 vs. Aβ25–35. HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with vehicle, 1 mM tempol or 100 µM α-tocopherol and treated for additional 3 h with 5 µM Aβ25–35. C) Ca2+ levels were determined by fluorescence microscopy with the probe Fluo-4-AM. D) O2 .− levels were determined by fluorescence microscopy using the probe MitoSOX-AM. Results show the percentage of variation of fluorescence vs. control cells (n = 3). a, p<0.05 vs. control; b, p<0.05 vs. Aβ25–35.

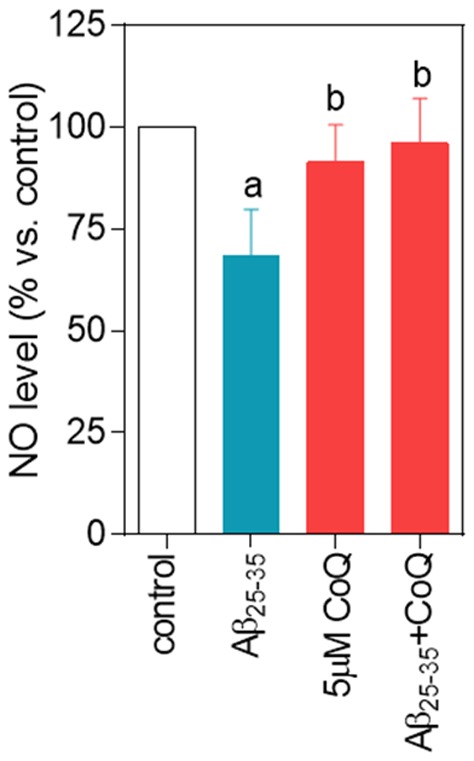

CoQ impedes NO decrease by β-amyloid in endothelial cells

NO is dampened under oxidative stress conditions, due to its reaction with O2 .−, resulting in the formation of peroxynitrite, and a subsequent increase in oxidative and nitrosative stress that alters endothelial cells function [35]. Our results, obtained with the Griess method, showed that a 24 h treatment of HUVECs with 5 µM Aβ25–35 decreased the production of NO by 40%. Pretreatment with 5 µM CoQ avoided this inhibitory effect of Aβ on NO production (Figure 6), which compares with the reduction in O2 .− and H2O2 by CoQ pretreatment, as shown above.

Figure 6. Nitric oxide decrease is prevented by CoQ treatment.

HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with vehicle or 5 µM CoQ and treated for additional 24 h with 5 µM Aβ25–35. NO was determined in the supernatant by the Griess method. Results are expressed as percentage of NO vs. control (n = 4). a, p<0.05 vs. control; b, p<0.05 vs. Aβ25–35.

CoQ prevents β-amyloid opening of the mPTP in endothelial cells

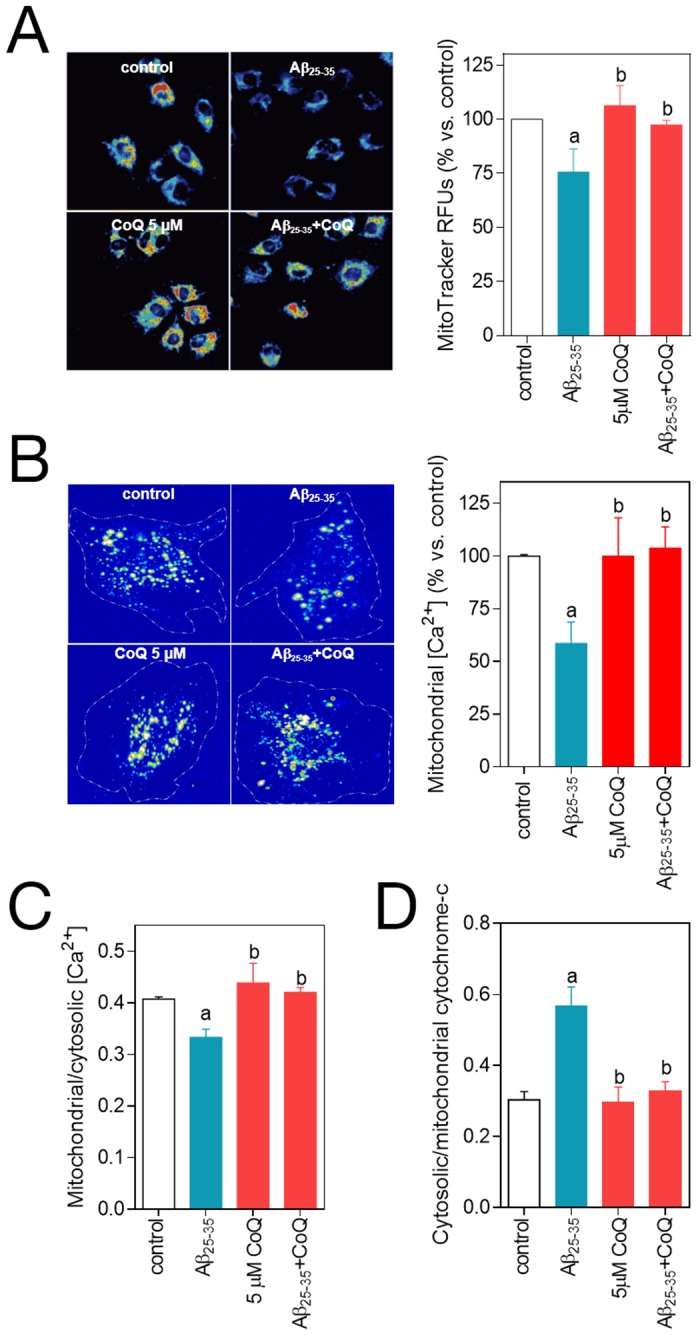

Aβ-mediated rise in O2 .−, H2O2 and Ca2+ is linked to the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, which releases mitochondrial content into the cytosol, including the cytochrome c from the inter-membrane space, and initiates cell death. As CoQ inhibits mPTP opening in neurons [16], [17], we speculated a similar mechanism could operate in endothelial cells injured by Aβ. We evaluated the mPTP by different strategies. We tested the effect of 5 µM Aβ25–35 on MitoTracker fluorescence and the level of mitochondrial Ca2+ in HUVECs. MitoTracker staining revealed a 25% reduction in the signal after 24 h treatment with 5 µM Aβ25–35 peptide (Figure 7A, Figure S3), which indicates a change in mitochondrial membrane potential, as MitoTracker intensity depends on mitochondrial membrane polarization. The 3 h treatment with 5 µM Aβ25–35 peptide was accompanied by a significant decrease in mitochondrial Ca2+ (Figure 7B,C, Figure S3), which supports an alteration in mitochondrial permeability. Both MitoTracker intensity signal and mitochondrial Ca2+ levels remained unaltered in HUVECs pretreated with 5 µM CoQ (Figure 7A,B,C, Figure S3). Furthermore, mPTP opening is reinforced by the release of cytochrome c to the cytosol. Addition of 5 µM Aβ25–35 to control HUVECs resulted into a strong release of cytochrome c, reaching a 2-fold increase in the cytosolic/mitochondrial ratio vs. untreated cells (Figure 7D; Figure S4). Cytochrome c release was completely abolished in HUVECs preloaded with 5 µM CoQ (Figure 7D, Figure S4).

Figure 7. CoQ impedes β-amyloid-induced mPTP opening.

HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with vehicle or 5 µM CoQ and treated for additional 3–24 h with 5 µM Aβ25–35. The effect of the treatments on mPTP opening was quantified indirectly by measuring MitoTracker Deep Red fluorescence, mitochondrial Ca2+ and cytochrome c release. After treatment with 5 µM Aβ25–35, mitochondria were loaded with MitoTracker Deep Red A), Calcein-AM and CoCl2 B) and MitoTracker Deep Red plus Fluo-4 C). Fluorescence intensity for each probe was determined by fluorescence microscope in living cells (n = 3/4). Mitochondrial Ca2+ levels were calculated by quenching the cytosolic Calcein-AM signal with CoCl2 B) and by colocalization of Fluo-4 and MitoTracker and furfher image processing with ImageJ C). Cells were loaded with Mitotracker Deep Red and immunostained with an anti-cytochrome c D). The amount of cytochrome c in cytosol was calculated by colocalization and image processing with ImageJ (n = 3). Results show the percentage of relative fluorescence units (RFUs) vs. control cells or the ratio between cytosolic/mitochondrial Fluo-4-AM or cytochrome c RFUs level. a, p<0.05 vs. control; b, p<0.05 vs. Aβ25–35.

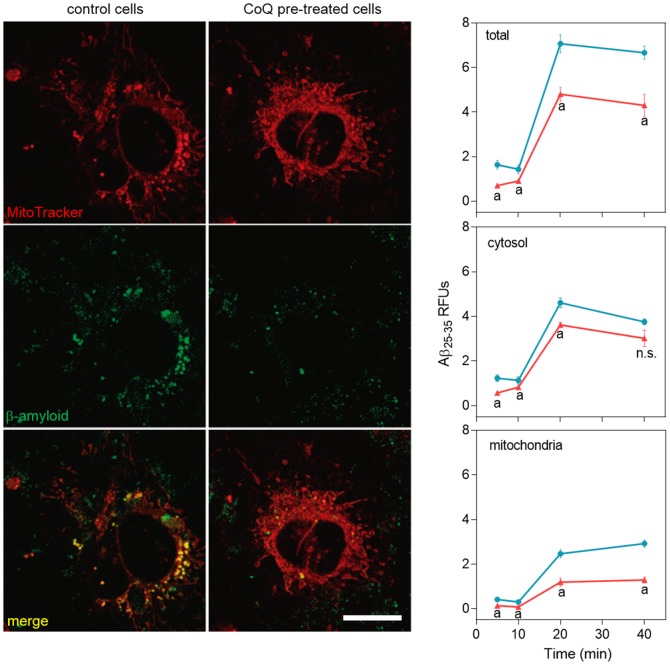

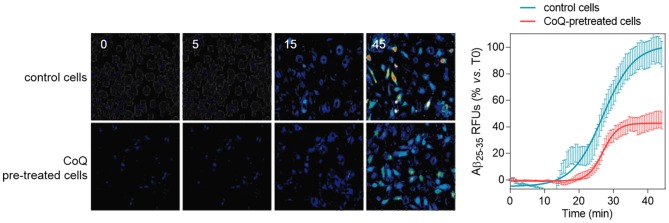

CoQ reduces β-amyloid entry and accumulation into endothelial cell mitochondria

We next tested the effect of CoQ on the incorporation of fluorescent Aβ25–35 peptides into HUVECs and its trafficking and accumulation into mitochondria, using fluorescence and confocal microscopy in living cells. Our results showed that fluorescent Aβ25–35 signal surpassed the control cells threshold 15 m after peptide administration, reaching a plateau at 40 min (Figure 8, blue line). Preincubation of HUVECs with 5 µM CoQ resulted in a 10 m delay in the incorporation, accompanied by a 60% reduction in the maximum signal as compared with control cells (Figure 8, red line). These epifluorescence results were reproduced by confocal microscopy, which showed a 45% reduction in the level of fluorescent Aβ25–35 accumulation in whole CoQ pretreated HUVECs 40 m after peptide administration (Figure 9, upper graph). Co-staining with MitoTracker revealed that this difference was not due to an inhibition of Aβ entry into the cytosol (Figure 9, middle graph), but to its accumulation into the mitochondria (Figure 9, bottom graph). Nevertheless, cytosolic Aβ fluorescence was reduced in CoQ treated cells up to 20 m after Aβ addition, whereas differences to control cells lacked statistical significance after 40 min (Figure 9, middle graph). On the other hand, fluorescent Aβ was significantly decreased in the mitochondrial compartment at only 5 m after Aβ addition to CoQ pretreated cells, and this difference increased 3-fold at longer incubation times (Figure 9, bottom graph). Confocal microscopy images depicted in Figure 9 are representative cells incubated for 40 min with fluorescent Aβ. Taken together, these results demonstrate that CoQ delays and reduces the entry of Aβ into HUVECs and also significantly dampens trafficking and incorporation into the mitochondria.

Figure 8. CoQ delays and decreases β-amyloid incorporation into endothelial cells.

HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with vehicle or 5 µM CoQ. Changes in HiLyte Fluor-labeled Aβ25–35 were monitored by time-lapse microscopy every 30 sec in cells pretreated with PBS or 5 µM CoQ. Fluorescent peptide (5 µM) was added in min 1. Pictures show the variation of fluorescence at different time points, from 0 to 45 min. Graph shows fluorescence dynamics, expressed as normalized relative fluorescence units (RFUs), (n = 3).

Figure 9. CoQ lessens β-amyloid incorporation into endothelial cells mitochondria.

HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with vehicle or 5 µM CoQ, loaded with Mitotracker Deep Red, and then treated with 5 µM HiLyte Fluor-labeled Aβ25–35 for 0, 10, 20 and 40 min. Pictures were immediately acquired by confocal microscopy in living cells and show the staining with Mitotracker Deep Red, HiLyte Fluor-labeled Aβ25–35 (green) and merges, in control (left) and CoQ incubated cells (right) at 40 min from Aβ25–35 addition. Colocalization and image processing were performed with ImageJ. Graphs show HiLyte Fluor-labeled Aβ25–35 relative fluorescence units (RFUs) vs. time in the whole cell (total; upper graph), cyotosol (middle graph) and mitochondria (bottom graph) in control (black line) and CoQ incubated cells (grey line). n = 3; a, p<0.005 vs. Aβ25–35.

CoQ restores the metabolic profile altered by β-amyloid in endothelial cells

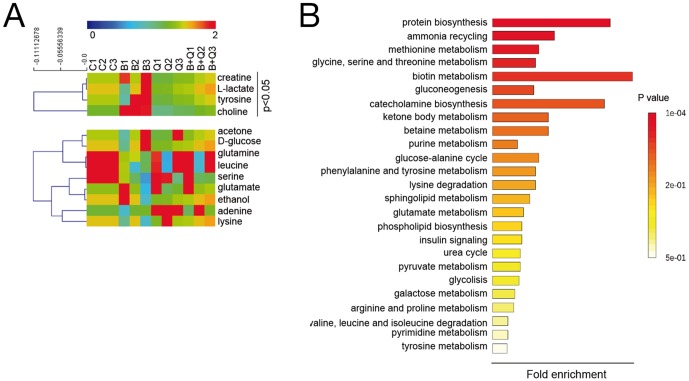

Recent studies using murine models of Alzheimer's disease revealed a profound alteration in brain metabolite profiles, which occurs prior to the deposition of Aβ plaques and the appearance of early behavioral changes [37]. Indeed, these changes reflect an increased mitochondrial stress and are related to alterations in Krebs cycle, energy transfer, carbohydrate, neurotransmitter, and amino acid metabolic pathways [37]. On this rationale and based on our previous results (see above), we questioned, first, if Aβ exerts a similar action in endothelial cells and, second, if CoQ could restore those possible Aβ-induced changes to control levels. Using a RMN-based metabolomic approach, we identified 13 metabolites (Figure 10A). Enrichment analysis revealed the alteration of several pathways including those related to protein biosynthesis, biotin metabolism and catecholamine biosynthesis, among others (Figure 10B). Indeed, addition of 5 µM Aβ25–35 to HUVECs for 24 h resulted in an increase in adenine, tyrosine, L-lactate, creatine and choline levels in 1.3, 1.4, 1.6, 1.4 and 1.75 fold of control, respectively (Figure 10A). Preincubation with 5 µM CoQ abolished the effect of Aβ, lowering metabolite levels to control levels, with the exception of adenine (Figure 10A).

Figure 10. CoQ prevents metabolic changes induced by β-amyloid in endothelial cells.

HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with vehicle or 5 µM CoQ and treated with 5 µM Aβ25–35. Samples were sonicated, lyophilized and dissolved in 40 µl D2O. 1H NMR spectra were registered with a Nanoprobe at 400 MHz resonance frequency. Metabolites were identified with Chenomx Profiler and by means of 2D homo- and heteronuclear NMR experiments. Differential analysis and classification was performed with MEV4 and pathways enrichment with MetaboAnalist. A) Heatmap and clustering of metabolites identified in HUVECs (n = 3). p<0.05 where indicated. B) Pathways enrichment based on the identified metabolites. Results show the averaged fold change vs. vehicle-treated cells (n = 3). a, p<0.05 vs. control; b, p<0.05 vs. Aβ25–35.

Discussion

Vascular degeneration is initiated by soluble Aβ in early, asymptomatic, Alzheimer's disease stages [2]. The deleterious effect of soluble Aβ in endothelial cells involves its incorporation into the membranes, uptake and trafficking to the mitochondria. This process results in an excess of superoxide free radicals and H2O2 plus the deregulation of calcium homeostasis, inducing cell death by apoptosis and necrosis. This damage impairs endothelial cell migration, thus creating gaps that compromise microvessel function [1], [35], [36]. In this study, we show that the lipophilic antioxidant CoQ emerges as an attractive candidate to prevent the deleterious effects of Aβ on endothelial cells in early Alzheimer's disease stages, which could significantly delay the progression of the pathology. Importantly, we found that CoQ effects are cytoprotective and should be administered before endothelial damage is irreversible.

CoQ cytoprotection involves the blockade of Aβ action at several steps, some of them shared by other antioxidant molecules, but others unique or not described to date. Indeed, previous investigations demonstrated that free radical scavengers prevented, at least in part, Aβ-induced toxicity [2]. Similarly, we have found that the antioxidants tempol and α-tocopherol at high doses only partially reversed Aβ-induced apoptosis and necrosis (Figure 5). On the other hand, CoQ cytoprotective effects are robust and maximal at 5 µM, a concentration which lies within a range reached in vivo after oral supplementation [38].

Our results show, for the first time, that CoQ reduces and delays Aβ incorporation and accumulation into the cell, which is paralleled by a reduction in the influx of extracellular Ca2+. It is known that soluble Aβ incorporates into the plasma membrane forming channels that produce ion leakiness, thus mediating Ca2+ entry into the cytosol [12]–[14], [39]. It is noteworthy that the protective effect of CoQ is not mediated by a simple chemical interaction with Aβ, because the simultaneous addition of CoQ and Aβ did not result in protection of HUVECs from Aβ toxicity. Rather, HUVECs should be preincubated with CoQ for this protective effect to be observed. Treatment of HUVEC with CoQ (1–10 µM) for 12 h increased its intracellular levels in a concentration-dependent manner [27]. Exogenous CoQ is initially accumulated in the endo-lysosomal compartment, and then rapidly becomes incorporated mainly to mitochondria-associated membranes and mitochondria, whereas its distribution among endomembranes and the plasma membrane is a late event, requiring 12 hours [40]. In addition, a functional intracellular vesicular trafficking is needed for CoQ to reach various cellular compartments [40]. This suggest that its inhibitory effect on Aβ uptake in endothelial cells does not involve the impairment of endocytic mechanisms. Moreover, the 25–35 fragment and the Aβ are highly hydrophobic peptides which are inserted into the membrane hydrocarbon core, and their incorporation depends on the lipid composition of the bilayer [39], [41]. CoQ is incorporated into all cell membranes [40] and disposes the long isoprenoid tail in the hydrophobic midplane of the lipid bilayer in such a way that phospholipid polar heads are in tight contact with the last isoprenoid unit of the CoQ hydrophobic tail [42]. Based on this, we hypothesize that CoQ could block, via steric hindrance, Aβ incorporation into the plasma membrane and Ca2+ entry, acting as a “cellular armor” and reducing the formation of channels.

The inhibition of the extracellular calcium influx by the addition of verapamil or pimozide (two calcium channels blockers) to endothelial cell culture medium only partially prevented the Aβ toxicity [5], indicating that Aβ also can release calcium from intracellular stores to increase the cytosolic calcium level. Mitochondria are major intracellular calcium stores and we demonstrated here that Aβ is quickly driven to mitochondria in HUVECs, deregulating calcium homeostasis. Preincubation of HUVECs with CoQ reduced Aβ uptake and mainly the Aβ accumulation into mitochondrion, which is paralleled by a blockade of the intracellular calcium influx induced by Aβ and the reestablishment of the mitochondrial calcium to control levels, which was otherwise significantly decreased under Aβ insult.

It has been demonstrated, both in vitro and in vivo, that Aβ is localized to the mitochondrial cristae of neurons [19] and that the sole mitochondria-specific Aβ accumulation is sufficient to cause ROS elevation and mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to mPTP opening and cytochrome c release, and causing cellular toxicity and death [16]–[18]. In this sense, a CoQ binding site regulates the aperture of the mPTP [28], and it has been reported that CoQ is effective at inhibiting mPTP opening induced by H2O2 in epithelial cells [29] or by Aβ in neurons [16], [17]. Our results show that CoQ protection from Aβ-induced deleterious effects in endothelial cells also involves these mechanisms. CoQ pretreatment reduced Aβ trafficking and accumulation into the mitochondria (Figure 9), impeding both mPTP opening and cytochrome c release, which was accompanied by a reduction in O2 .− and H2O2 levels. Furthermore, O2 .− and H2O2 reduction resulted in an increase of NO levels. As previously described in neurons, Aβ trafficking to the mitochondria increases ROS levels, which react with NO to produce peroxynitrite, inactivating MnSOD by nitration and generating additional free radicals that over-damage mitochondria [35], [43]. Furthermore, CoQ located in extra-mitochondrial membranes, such as in the Golgi compartment, may be an important cofactor to maintain eNOS in a coupled conformation required to produce physiological NO and, eventually, quench leaking-uncoupled electrons [44].

Metabolomics data reinforce the CoQ improvement of Aβ-impaired mitochondrial function. Indeed, Aβ treatment resulted in an increase of creatine levels (Figure 10), which, as reported previously, could be due to an inhibition of creatine kinase by oxidative stress-mediated carbonylation, thus disturbing mitochondrial bioenergetics [45]. Aβ also increased L-lactate level (Figure 10), which indicates a shift to fermentative metabolism, reinforcing Aβ-induced mitochondrial damage [37]. Our results show that pretreatment of endothelial cells with CoQ restored both creatine and L-lactate to control levels, indicating a normalization of mitochondrial function.

Aβ-increased ROS and Ca2+ levels in endothelial cells are translated into increased necrosis and apoptosis. Thus, we found an increased level of choline in Aβ-treated cells which, as indicated previously for retina pericytes, could be consequence of a high phosphatidylcholine hydrolysis due to the pro-oxidant effect of Aβ peptide that drives to necrotic cell death [46]. Pretreatment with CoQ restored choline to control levels, and also inhibited endothelial necrosis and apoptosis. In an in vivo setting, endothelial cell death in microvessels increases permeability and compromises oxygen delivery and nutrient exchange. Moreover, our results show that Aβ also interfered with the ability of endothelial cells to promote wound repair, as manifested by decreased motility and impaired tube-like structure formation. These processes are implicated in the disturbance of the endothelial integrity because, endothelial cells extruded lamellipodia to move and rapidly close the wound during repair processes [47]. Aβ25–35 addition to HUVECs resulted in a marked decrease in lamellipodia extrusion and a significant delay in wound closure, but preincubation with CoQ reversed the inhibition of the cellular motility. These findings suggest that CoQ can protect microvasculature against the Aβ25–35-induced endothelial cell death, but can also improve the restoration of the endothelial function by re-endothelization in pathological conditions associated to AD, reducing blood draining and improving oxygenation and nutrients delivery, thus, impacting on neuronal function.

Although AD is, by definition, a non-vascular dementia, vascular comorbidity may be present in the 30-60% of AD patients [20], making compounds that halt vascular oxidative stress putative candidates for therapeutical interventions. Augmented levels of ROS are common factors in all major vascular diseases [48]. Oral CoQ supplementation has been used recently in clinical trials to improve the endothelial function in type II diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [21], [22], [49], [50], and a meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials concluded that CoQ supplementation is associated with significant improvement in endothelial function [22]. It has been proposed a plasma threshold of 2.5 µM, above which positive effects can be observed [51]. Reported plasma CoQ in healthy people ranged from 0.40 to 1.91 µM, but after daily oral supplementation with 200–300 mg of CoQ, plasma CoQ concentration increase up to 3–5 µM [38], the same CoQ concentration range used in our experiments. These data suggest that CoQ supplementation could be useful in therapy to protect endothelial cells in vivo against Aβ injury.

In conclusion, our results reported herein provide the first in vitro evidence that CoQ inhibits the uptake and mitochondrial trafficking of Aβ peptide in human endothelial cells, also alleviating Aβ-induced oxidative injury, cell death and decreased motility. CoQ emerges as an attractive molecule to prevent AD-associated endothelial dysfunction in high risk populations during early asymptomatic stages of the disease.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Coenzyme Q10 was generously provided by Kaneka Corporation. Human Aβ25–35 and tempol were purchased from Tocris. Human Aβ25–35 labelled with HiLyte Fluor 488 was obtained from Anaspec. The fluorescent probes, Fluo-4 AM, H2DCF-DA, MitoSOX-AM, MitoTracker Deep Red, Calcein-AM and Hoescht were obtained from LifeSicences. Alpha tocopherol was acquired from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; Clonetics, Lonza) were maintained in complete EGM-2 medium (Clonetics, Lonza) containing 20% FBS and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic, at 37°C and 5% CO2. Experiments were performed in DMEM containing 20% FBS. All cells used in this study were up to the 15th passage.

Determination of apoptosis, necrosis and viability

Cells were seeded in 96 well plates and incubated for 12 h with vehicle (controls), CoQ ranging from 1 to 7.5 µM, 1 µM tempol or 100 µM α-tocopherol. The medium was removed and Aβ25–35 was added to 5 µM. Where indicated, CoQ and Aβ25–35 where added simultaneously to the cultures. After 24 h, cells were incubated with 10 µg/ml EtBr and 1 µM Calcein-AM. Viable (green) and necrotic cells (red) were determined by fluorescence microscopy with a Nikon TiU microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) using a 20× objective. Immediately after image acquisition, cells were fixed and permeabilized for 2 min in ice-cold methanol and stained with 1 µg/ml Hoescht. Apoptotic nuclei were determined according morphological criteria. For necrosis, viability and apoptosis, results are expressed as percentage vs. total (n = 4). Additionally, apoptosis was determined by cell flow cytometry. To this end, cells were plated onto 6-well plates and treated as described above. Then, cells were labeled with an anti-annexin V antibody (Bender MedSystems) and apoptotic cells were quantified with a cell flow cytometer FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) following the manufacturer's instructions. Results are shown as percentage of apoptotic cells vs. total (n = 4).

Assays for migration and cell tube formation

HUVECs were plated in 12-well plates, cultured to confluence and then serum starved for 12 h in medium containing vehicle (control) or 5 µM CoQ. A cross-scratch was done in the monolayer with a 10 µl pipet tip and the medium was replaced by a fresh medium containing 5 µM Aβ25–35. Percentage of wound closure was calculated by measuring on each image, with ImageJ, the open area free of cells immediately after doing the scratch and at 24 h. Results shown are average of n = 3.

To analyze cytoskeleton reorganization, cells were treated as indicated above and then fixed for 5 min in cold methanol, incubated for 30 min in blocking buffer, stained with the monoclonal antibody for β-actin (Sigma) and detected with an AlexaFluor488-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Life Sciences). Images were obtained using a Nikon TiU microscope (20× objective). To quantify the effects of the treatments on actin reorganization and thus, on cell mobility, cells with a static and a migratory (lamellipodia positive) phenotype were counted in a double blind procedure. At least 200 cells in 4 independent experiments were counted for each group, and cells with migratory phenotype were considered positive. Results are expressed as percentage of positive cells normalized vs. control.

For in vitro angiogenesis, HUVECs incubated for 12 h with vehicle (control) or CoQ in 24 well plates were detached and plated onto GFR Matrigel-precoated 96-well plates, adding 5 µM Aβ25–35 to the culture medium. Cells were incubated for 6 h and then, the number of cell-tubes was counted from phase-contrast microscopy images. Results were calculated as percentage of cell-tubes vs. control (with neither CoQ nor Aβ, n = 4).

Determination of O2 .−, H2O2 and Ca2+ in single cells

Mitochondrial O2 .−, total H2O2 and free cytosolic Ca2+ levels were determined with the fluorescent probes MitoSox, H2DCF-DA and Fluo-4 (Life Sciences), respectively. Cells were seeded in 96 well plates and incubated for 12 h with vehicle (controls) or CoQ ranging from 1–7.5 µM, 1 mM tempol or 100 µM α-tocopherol. Medium was removed and cells were incubated for 3 h in fresh medium containing 5 µM Aβ25–35 peptide. Cells were then loaded for 30 m with 1 µM of the fluorescent probe (one independent probe per assay), washed in fresh medium and imaged in a Nikon TiU microscope (20× objective). Images were analyzed and processed with ImageJ. Results show the percentage of cell signal vs. control (n = 4).

The effect of CoQ on Aβ25–35-induced Ca2+ level was determined using a real time epifluorescence approach. Cells were grown onto 35 mm plates and treated for 12 h with vehicle (control) or 5 µM CoQ. Then, cells were loaded for 30 min with 1 µM Fluo-4 and media was replaced by Hank's balanced solution with/without Ca2+, to assess whether Aβ25–35 effect was due to Ca2+ entry or release from intracellular stores. Cells where imaged in a Nikon TiU microscope (20x objective). The baseline was established within the first minute of recording and after that, 5 µM Aβ25–35 was added to the plate. Epifluorescence images were recorded every 15 s up to 35 m. Series were analyzed with ImageJ. Results show the percent of averaged profiles vs. baseline, for each treatment (n = 3).

NO determination

NO level was assessed by the quantification of nitrite accumulation in the culture medium. Cells were seeded in 12 well plates and incubated for 12 h with vehicle (control) or 5 µM CoQ. Total nitrite accumulated was measured using the modified Griess reagent, according the indications of the manufacturer (Sigma-Aldrich). Results were evaluated by spectrophotometry (BioRad iMark) at 540 nm and expressed as percentage vs. control (n = 4).

Mitochondrial Ca2+ and cytochrome c levels

Mitochondrial Ca2+ was determined by staining the cells with Calcein-AM and quenching the cytosolic Calcein signal with CoCl2. To this end, cells were seeded in 8 well μ-slides (Ibidi) and incubated for 12 h with vehicle (control) or 5 µM CoQ. The medium was removed and cells were incubated for 3 h in fresh medium containing 5 µM Aβ25–35 peptide. Then, cells were loaded for 30 min with 1 µM Calcein-AM and 1 mM CoCl2, washed in fresh medium and imaged in a Nikon TiU microscope (60x objective). Results, calculated with ImageJ, are expressed as the percentage of mitochondrial Calcein signal vs. control (n = 3). Alternatively, mitochondrial Ca2+ was evaluated by co-staining cells with Fluo-4 and the fluorescent mitochondrial probe Mitotracker DeepRed (Life Sciences), which signal is sensitive to mitochondrial potential changes. To this end, cells were seeded in 96 well plates and incubated for 12 h with vehicle (control) or 5 µM CoQ. The medium was removed and cells were incubated for 3 h in fresh medium containing 5 µM Aβ25–35 peptide. Then, cells were loaded for 30 min with Fluo-4 and Mitotracker DeepRed (1 µM each), washed in fresh medium and imaged in a Nikon TiU microscope (20× objective). Mitotracker DeepRed signal was directly quantified with ImageJ. Results show the percentage of cell signal vs. control (n = 4). The amount of mitochondrial Ca2+ was calculated by image analysis, subtracting the Fluo-4 signal colocalizing with Mitotracker to the whole cell Fluo-4 signal. This processing was done with ImageJ. Results are expressed as the ratio between mitochondrial and total Ca2+ for each treatment (n = 4).

Cytochrome c subcellular localization was assessed by labeling mitochondria with Mitotracker DeepRed and immunolabeling cytochrome c with a specific monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences). Briefly, cells seeded in 96 well plates were incubated for 12 h with vehicle (control) or 5 µM CoQ. Medium was removed and cells were incubated for 24 h in fresh medium containing 5 µM Aβ25–35 peptide. Then, cells were loaded for 30 min with 1 µM Mitotracker DeepRed, fixed for 2 min in cold methanol, and stained for 30 min with fluorescein labeled anti-cytochrome c antibody (1∶200). Cells were washed and immediately imaged in a Nikon TiU microscope (20× objective). The amount of mitochondrial cytochrome c was calculated by image analysis, subtracting the whole cell cytochrome c signal to the cytochrome c signal colocalizing with Mitotracker. Image processing was performed with ImageJ. Results are expressed as the ratio between cytosolic and mitochondrial cytochrome c level for each treatment (n = 4).

sMASE activity

Cells were seeded in 12 well plates and incubated for 24 h with vehicle (controls) or 5 µM CoQ and then incubated for 24 h in fresh medium containing 5 µM Aβ25–35 peptide. Cells were detached and nSMAse activity was determined from cell extracts as described in earlier studies [32].

Aβ25–35 incorporation into HUVECs

The effect of CoQ on Aβ25–35 incorporation into HUVECs was determined by both fluorescence and confocal approaches. In a first approach, cells were grown onto 35 mm plates and treated for 24 with vehicle (controls) or 5 µM CoQ. Then, plates were mounted onto the stage of a Nikon TiU microscope under a 20x objective. A concentration of 5 µM Aβ25–35 peptide labeled with HiLyte Fluor 488 was added and fluorescence was recorded every 30 sec up to 45 min. Time-series were analyzed with ImageJ. Results show averaged cell-fluorescence profiles vs. baseline (n = 3) and data fit to exponential growth curves. For confocal studies, cells were grown onto gelatin-coated glass-bottom 35 mm plates and treated for 24 with vehicle (controls) or 5 µM CoQ. Then, cells were stained with 1 µM Mitotracker DeepRed and incubated with 5 µM Aβ25–35 labeled with HiLyte Fluor 488 for 5, 10, 20 and 40 min. After incubation, cells were washed and plates mounted onto the stage of a Zeiss LSM5 confocal microscope under a 40x objective. Images were sequentially acquired for green (Aβ25–35 peptide) and red (Mitotracker DeepRed) channels and processed with ImageJ to calculate the signal of fluorescent Aβ25–35 in the whole cell, cytosol and mitochondria. Results show the averaged cell Aβ25–35 fluorescence (n = 3).

Metabolomics

Cells were grown onto 25 cm2 flasks and treated for 12 with vehicle (control) or 5 µM CoQ and then incubated for 24 h in fresh medium containing 5 µM Aβ25–35 peptide. Cells were detached, rinsed twice in PBS and homogenized by sonication in deuterated D2O (99.98% atom % D) (Sigma-Aldrich). Extracts were lyophilized and resuspended again in 40 µl of deuterated water (99.994 atom % D) (Sigma-Aldrich). NMR spectra were performed on a Varian VNMRS-400 NMR system using a nanoprobe with rotors of 40 µl. 1D and 2D NMR spectra were recorded for peak identification. The NMR spectra were processed with Mestrenova (Mestrelab Research) and peaks were also identified with Chenomx Profiler (Chenomx Inc.). Clustering and paired analysis for changes in the metabolites profile were assessed with the free software MEV 4.9 (http://www.tm4.org/mev.html). Pathways enrichment was analyzed using the platform MetaboAnalist 2.0 (http://www.metaboanalyst.ca/MetaboAnalyst/faces/Home.jsp).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. obtained from, at least, three separate, independent experiments carried out on different days with different cell preparations. Statistical analysis was carried out with Graphpad Prism 6, using Student's t-test followed by a Mann–Whitney statistical test or one-way ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis test) followed by a statistical test for multiple comparisons (Dunn's test). Differences were considered significant at p<0.05.

Supporting Information

Co-administration of CoQ affects neither free cytosolic Ca2+ nor apoptosis increase by β-amyloid. A) HUVECs were co-incubated for 12 h with CoQ and Aβ25–35 (5 µM each). Apoptosis was determined by DAPI staining and morphological analysis of nuclei. Results are expressed as the percentage of apoptotic vs. total nuclei (300 cells/treatment, n = 3). B) HUVECs were co-incubated for 3 h with vehicle and CoQ and Aβ25–35 peptide (5 µM each). Ca2+ levels were determined by fluorescence microscopy with the probe Fluo-4-AM. Results show the percentage of variation of fluorescence vs. control cells (n = 3). a, p<0.05 vs. control.

(TIF)

Effect of β-amyloid peptide and CoQ on n-SMase activity. HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with 5 µM CoQ, treated for additional 24 h with 5 µM Aβ25–35 peptide and then washed and pelleted. Neutral SMase activity was assayed as described in [32]. (n = 4).

(TIF)

Representative pictures of mitochondrial Ca2+ quantification. HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with vehicle or 5 µM CoQ and treated for additional 3 h with 5 µM Aβ25–35. Ca2+ levels were measured with Fluo-4-AM. Mitochondria were labeled with MitoTracker Deep Red. Images were acquired with an inverted fluorescence microscope and processed with ImageJ. For each picture, a mask corresponding to mitochondria was subtracted from total Ca2+ image to obtain a value of total-mitochondrial Ca2+.

(TIF)

Representative pictures of cytosolic cytochrome c quantification. HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with 5 µM CoQ and treated for additional 24 h with 5 µM Aβ25–35. Cytochrome c was determined by ICC (green). Mitochondria were labeled with MitoTracker Deep Red. Images were acquired with an inverted fluorescence microscope and processed with ImageJ. For each picture, a mask corresponding to mitochondria was subtracted to total cytochrome c image, to obtain a value of the cytosolic fraction.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Kaneka Corporation, who generously provided the CoQ used in these experiments. M.V.G. acknowledges Albacete Science and Technology Park.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

The authors' work is supported by Grants: Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha GE20112221. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Mattson MP (2004) Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer's disease. Nature 430: 631–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Park L, Anrather J, Forster C, Kazama K, Carlson GA, et al. (2004) Abeta-induced vascular oxidative stress and attenuation of functional hyperemia in mouse somatosensory cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 24: 334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Biron KE, Dickstein DL, Gopaul R, Jefferies WA (2011) Amyloid triggers extensive cerebral angiogenesis causing blood brain barrier permeability and hypervascularity in Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One 6: e23789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marchesi VT (2011) Alzheimer's dementia begins as a disease of small blood vessels, damaged by oxidative-induced inflammation and dysregulated amyloid metabolism: implications for early detection and therapy. The FASEB Journal 25: 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Suo Z, Fang C, Crawford F, Mullan M (1997) Superoxide free radical and intracellular calcium mediate A beta(1–42) induced endothelial toxicity. Brain Res 762: 144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Behl C, Davis JB, Lesley R, Schubert D (1994) Hydrogen peroxide mediates amyloid beta protein toxicity. Cell 77: 817–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Akiyama H, Ikeda K, Kondo H, McGeer PL (1992) Thrombin accumulation in brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett 146: 152–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rizzo MT, Leaver HA (2010) Brain endothelial cell death: modes, signaling pathways, and relevance to neural development, homeostasis, and disease. Mol Neurobiol 42: 52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hsu M-J, Hsu CY, Chen B-C, Chen M-C, Ou G, et al. (2007) Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 in amyloid beta peptide-induced cerebral endothelial cell apoptosis. J Neurosci 27: 5719–5729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blanc EM, Toborek M, Mark RJ, Hennig B, Mattson MP (1997) Amyloid beta-peptide induces cell monolayer albumin permeability, impairs glucose transport, and induces apoptosis in vascular endothelial cells. J Neurochem 68: 1870–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xu J, Chen S, Ku G, Ahmed SH, Chen H, et al. (2001) Amyloid beta peptide-induced cerebral endothelial cell death involves mitochondrial dysfunction and caspase activation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 21: 702–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bhatia R, Lin H, Lal R (2000) Fresh and globular amyloid beta protein (1–42) induces rapid cellular degeneration: evidence for AbetaP channel-mediated cellular toxicity. FASEB J 14: 1233–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kawahara M (2010) Neurotoxicity of β-amyloid protein: oligomerization, channel formation, and calcium dyshomeostasis. Cur Pharm Des 16: 2779–2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lal R, Lin H, Quist AP (2007) Amyloid beta ion channel: 3D structure and relevance to amyloid channel paradigm. Biochim Biophys Acta 1768: 1966–1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park L, Anrather J, Zhou P, Frys K, Pitstick R, et al. (2005) NADPH-oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species mediate the cerebrovascular dysfunction induced by the amyloid beta peptide. J Neurosci 25: 1769–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Belliere J, Devun F, Cottet-Rousselle C, Batandier C, Leverve X, et al. (2012) Prerequisites for ubiquinone analogs to prevent mitochondrial permeability transition-induced cell death. J Bioenerg Biomembr 44: 207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li G, Zou LY, Cao CM, Yang ES (2005) Coenzyme Q10 protects SHSY5Y neuronal cells from beta amyloid toxicity and oxygen-glucose deprivation by inhibiting the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Biofactors 25: 97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cha MY, Han SH, Son SM, Hong HS, Choi YJ, et al. (2012) Mitochondria-specific accumulation of amyloid beta induces mitochondrial dysfunction leading to apoptotic cell death. PLoS One 7: e34929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hansson Petersen CA, Alikhani N, Behbahani H, Wiehager B, Pavlov PF, et al. (2008) The amyloid beta-peptide is imported into mitochondria via the TOM import machinery and localized to mitochondrial cristae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 13145–13150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grammas P (2011) Neurovascular dysfunction, inflammation and endothelial activation: implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflammation 8: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dai YL, Luk TH, Yiu KH, Wang M, Yip PM, et al. (2011) Reversal of mitochondrial dysfunction by coenzyme Q10 supplement improves endothelial function in patients with ischaemic left ventricular systolic dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. Atherosclerosis 216: 395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gao L, Mao Q, Cao J, Wang Y, Zhou X, et al. (2012) Effects of coenzyme Q10 on vascular endothelial function in humans: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Atherosclerosis 221: 311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tiano L, Belardinelli R, Carnevali P, Principi F, Seddaiu G, et al. (2007) Effect of coenzyme Q10 administration on endothelial function and extracellular superoxide dismutase in patients with ischaemic heart disease: a double-blind, randomized controlled study. Eur Heart J 28: 2249–2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tsai KL, Chen LH, Chiou SH, Chiou GY, Chen YC, et al. (2011) Coenzyme Q10 suppresses oxLDL-induced endothelial oxidative injuries by the modulation of LOX-1-mediated ROS generation via the AMPK/PKC/NADPH oxidase signaling pathway. Mol Nutr Food Res 55 Suppl 2: S227–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tsai KL, Huang YH, Kao CL, Yang DM, Lee HC, et al. (2012) A novel mechanism of coenzyme Q10 protects against human endothelial cells from oxidative stress-induced injury by modulating NO-related pathways. J Nutr Biochem 23: 458–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tsuneki H, Sekizaki N, Suzuki T, Kobayashi S, Wada T, et al. (2007) Coenzyme Q10 prevents high glucose-induced oxidative stress in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol 566: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tsuneki H, Tokai E, Suzuki T, Seki T, Okubo K, et al. (2013) Protective effects of coenzyme Q10 against angiotensin II-induced oxidative stress in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol 701: 218–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fontaine E, Ichas F, Bernardi P (1998) A ubiquinone-binding site regulates the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J Biol Chem 273: 25734–25740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Naderi J, Somayajulu-Nitu M, Mukerji A, Sharda P, Sikorska M, et al. (2006) Water-soluble formulation of Coenzyme Q10 inhibits Bax-induced destabilization of mitochondria in mammalian cells. Apoptosis 11: 1359–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Barth BM, Gustafson SJ, Kuhn TB (2012) Neutral sphingomyelinase activation precedes NADPH oxidase-dependent damage in neurons exposed to the proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Neurosci Res 90: 229–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arroyo A, Navarro F, Gomez-Diaz C, Crane FL, Alcain FJ, et al. (2000) Interactions between ascorbyl free radical and coenzyme Q at the plasma membrane. J Bioenerg Biomembr 32: 199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bello RI, Gomez-Diaz C, Buron MI, Alcain FJ, Navas P, et al. (2005) Enhanced anti-oxidant protection of liver membranes in long-lived rats fed on a coenzyme Q10-supplemented diet. Exp Gerontol 40: 694–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Patel NS, Quadros A, Brem S, Wotoczek-Obadia M, Mathura VS, et al. (2008) Potent anti-angiogenic motifs within the Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide. Amyloid 15: 5–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Folin M, Baiguera S, Tommasini M, Guidolin D, Conconi MT, et al. (2005) Effects of beta-amyloid on rat neuromicrovascular endothelial cells cultured in vitro. Int J Mol Med 15: 929–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Iadecola C (2004) Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 347–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kandimalla KK, Scott OG, Fulzele S, Davidson MW, Poduslo JF (2009) Mechanism of neuronal versus endothelial cell uptake of Alzheimer's disease amyloid beta protein. PLoS One 4: e4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trushina E, Nemutlu E, Zhang S, Christensen T, Camp J, et al. (2012) Defects in Mitochondrial Dynamics and Metabolomic Signatures of Evolving Energetic Stress in Mouse Models of Familial Alzheimer's Disease. PLoS ONE 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Villalba JM, Parrado C, Santos-Gonzalez M, Alcain FJ (2010) Therapeutic use of coenzyme Q10 and coenzyme Q10-related compounds and formulations. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 19: 535–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Simakova O, Arispe NJ (2011) Fluorescent analysis of the cell-selective Alzheimer's disease aβ Peptide surface membrane binding: influence of membrane components. Int J Alzheimer's Dis 2011: 917629–917629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fernandez-Ayala DJ, Brea-Calvo G, Lopez-Lluch G, Navas P (2005) Coenzyme Q distribution in HL-60 human cells depends on the endomembrane system. Biochim Biophys Acta 1713: 129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mason RP, Estermyer JD, Kelly JF, Mason PE (1996) Alzheimer's disease amyloid beta peptide 25–35 is localized in the membrane hydrocarbon core: x-ray diffraction analysis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 222: 78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Genova ML, Lenaz G (2011) New developments on the functions of coenzyme Q in mitochondria. Biofactors 37: 330–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Anantharaman M, Tangpong J, Keller JN, Murphy MP, Markesbery WR, et al. (2006) Beta-amyloid mediated nitration of manganese superoxide dismutase: implication for oxidative stress in a APPNLH/NLH X PS-1P264L/P264L double knock-in mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol 168: 1608–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mugoni V, Postel R, Catanzaro V, De Luca E, Turco E, et al. (2013) Ubiad1 is an antioxidant enzyme that regulates eNOS activity by CoQ10 synthesis. Cell 152: 504–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burklen TS, Schlattner U, Homayouni R, Gough K, Rak M, et al. (2006) The Creatine Kinase/Creatine Connection to Alzheimer's Disease: CK Inactivation, APP-CK Complexes, and Focal Creatine Deposits. J Biomed Biotechnol 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46. Lupo G, Anfuso CD, Assero G, Strosznajder RP, Walski M, et al. (2001) Amyloid beta(1–42) and its beta(25–35) fragment induce in vitro phosphatidylcholine hydrolysis in bovine retina capillary pericytes. Neurosci Lettr 303: 185–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wong MK, Gotlieb AI (1984) In vitro reendothelialization of a single-cell wound. Role of microfilament bundles in rapid lamellipodia-mediated wound closure. Lab Invest 51: 75–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Drummond GR, Selemidis S, Griendling KK, Sobey CG (2011) Combating oxidative stress in vascular disease: NADPH oxidases as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 10: 453–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hamilton SJ, Chew GT, Watts GF (2009) Coenzyme Q10 improves endothelial dysfunction in statin-treated type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 32: 810–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lim SC, Lekshminarayanan R, Goh SK, Ong YY, Subramaniam T, et al. (2008) The effect of coenzyme Q10 on microcirculatory endothelial function of subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis 196: 966–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Langsjoen PH (2000) Lack of effect of coenzyme Q on left ventricular function in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 35: 816–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Co-administration of CoQ affects neither free cytosolic Ca2+ nor apoptosis increase by β-amyloid. A) HUVECs were co-incubated for 12 h with CoQ and Aβ25–35 (5 µM each). Apoptosis was determined by DAPI staining and morphological analysis of nuclei. Results are expressed as the percentage of apoptotic vs. total nuclei (300 cells/treatment, n = 3). B) HUVECs were co-incubated for 3 h with vehicle and CoQ and Aβ25–35 peptide (5 µM each). Ca2+ levels were determined by fluorescence microscopy with the probe Fluo-4-AM. Results show the percentage of variation of fluorescence vs. control cells (n = 3). a, p<0.05 vs. control.

(TIF)

Effect of β-amyloid peptide and CoQ on n-SMase activity. HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with 5 µM CoQ, treated for additional 24 h with 5 µM Aβ25–35 peptide and then washed and pelleted. Neutral SMase activity was assayed as described in [32]. (n = 4).

(TIF)

Representative pictures of mitochondrial Ca2+ quantification. HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with vehicle or 5 µM CoQ and treated for additional 3 h with 5 µM Aβ25–35. Ca2+ levels were measured with Fluo-4-AM. Mitochondria were labeled with MitoTracker Deep Red. Images were acquired with an inverted fluorescence microscope and processed with ImageJ. For each picture, a mask corresponding to mitochondria was subtracted from total Ca2+ image to obtain a value of total-mitochondrial Ca2+.

(TIF)

Representative pictures of cytosolic cytochrome c quantification. HUVECs were incubated for 12 h with 5 µM CoQ and treated for additional 24 h with 5 µM Aβ25–35. Cytochrome c was determined by ICC (green). Mitochondria were labeled with MitoTracker Deep Red. Images were acquired with an inverted fluorescence microscope and processed with ImageJ. For each picture, a mask corresponding to mitochondria was subtracted to total cytochrome c image, to obtain a value of the cytosolic fraction.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper.