Abstract

Little research has explored parental engagement in schools in the context of adoptive parent families or same-sex parent families. The current cross-sectional study explored predictors of parents’ self-reported school involvement, relationships with teachers, and school satisfaction, in a sample of 103 female same-sex, male same-sex, and heterosexual adoptive parent couples (196 parents) of kindergarten-age children. Parents who reported more contact by teachers about positive or neutral topics (e.g., their child’s good grades) reported more involvement and greater satisfaction with schools, regardless of family type. Parents who reported more contact by teachers about negative topics (e.g., their child’s behavior problems) reported better relationships with teachers but lower school satisfaction, regardless of family type. Regarding the broader school context, across all family types, parents who felt more accepted by other parents reported more involvement and better parent–teacher relationships; socializing with other parents was related to greater involvement. Regarding the adoption-specific variables, parents who perceived their children’s schools as more culturally sensitive were more involved and satisfied with the school, regardless of family type. Perceived cultural sensitivity mattered more for heterosexual adoptive parents’ relationships with their teachers than it did for same-sex adoptive parents. Finally, heterosexual adoptive parents who perceived high levels of adoption stigma in their children’s schools were less involved than those who perceived low levels of stigma, whereas same-sex adoptive parents who perceived high levels of stigma were more involved than those who perceived low levels of stigma. Our findings have implications for school professionals, such as school psychologists, who work with diverse families.

Keywords: adoption, gay, kindergarten, lesbian, parent–teacher relationships, school involvement, school satisfaction

Individuals, including children, are profoundly impacted by the settings in which they live (e.g., home, school, neighborhood, and community) as well as the relationships among these systems (Bronfenbrenner, 1995). In particular, the dynamic relationship between family and school greatly contributes to child development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). Parents’ engagement with their children’s schools is widely recognized as one important way in which the family–school relationship may shape child outcomes. In fact, school engagement is the main focus of family–school relationship standards established by leading national organizations, such as the National Parent Teacher Association (2014). School professionals recognize that when parents develop strong relationships with teachers and seek involvement in schools, such relationships may (a) model for children the importance of relationships with teachers, thus affecting their academic experience, and (b) provide teachers with a more thorough understanding of children’s developmental needs and strengths, via the information that they gain from parents (Dearing, Kreider, & Weiss, 2008; Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 1995). Parents’ engagement in school (e.g., via volunteering) may also benefit child–teacher relationships indirectly, as such involvement can promote positive family–teacher interactions (Dearing et al.; Hornby, 2011). In turn, school psychologists can play a valuable role in promoting parent engagement through home–school collaborations and providing appropriate assessment and interventions for parents, teachers, and other school professionals (Beveridge, 2005).

The kindergarten period in particular is often recognized as an optimal time to foster and promote school engagement (Powell, Son, File, & San Juan, 2010), insomuch as parents’ early school engagement may set the stage for long-term patterns of school-based involvement and relationships with the educational system (Beveridge, 2005; Malsch, Green, & Kothari, 2011). Indeed, parents’ school engagement during preschool and kindergarten has been linked to children’s later academic and achievement outcomes, such that parents who demonstrate more school-based involvement and connection early on have children with better grades, attendance, homework completion, and state test results (Castro, Bryant, Peisner-Feinberg, & Skinner, 2004; Clements, Reynolds, & Hickey, 2004; Powell et al., 2010). Parents who have regular and direct contact with their children’s schools and teachers, and who therefore model an appreciation for school engagement and learning, are more likely to have children who demonstrate positive engagement with learning and their schools (McWayne, Hampton, Fantuzzo, Cohen, & Sekino, 2004). Thus, parental engagement in children’s education clearly benefits children's school success (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 1997; McWayne et al.).

There are several dimensions of parent engagement in children’s education, including school-based involvement (e.g., volunteering), the parent–teacher relationship, and home-based involvement (e.g., help with homework; Waanders, Mendez, & Downer, 2007). In this paper, we focus on parents’ involvement in the school context, as well as their relationships with teachers; we do not assess parents’ home-based involvement, in part because of the young age of the sample. We also examine parents’ overall endorsement of their child’s school (i.e., school satisfaction). We examine these outcomes in 103 adoptive parent couples: 35 female same-sex, 28 male same-sex, and 40 heterosexual adoptive couples, based on data from 68 sexual minority women, 54 sexual minority men, 35 heterosexual men, and 39 heterosexual women.

Although parents’ school engagement is widely recognized as a crucial component of successful family-school partnerships, and is often examined in the literature (see Powell et al., 2010), no work has examined parent–school relationships in adoptive families, and little work has explored parent–school relationships in same-sex parent families (Fedewa & Clark, 2009; Kosciw & Diaz, 2008). Such work is important, in order to identify whether established predictors of school engagement hold up in these understudied family forms, as well as to identify unique predictors of school engagement. Same-sex parent families and adoptive families represent understudied family forms that are vulnerable to marginalization and exclusion in society and in the school setting, which may in turn have implications for their perspectives on and relationships with their children’s schools (Goldberg & Smith, 2014). Many aspects of the school environment assume a biological relationship between parent and child, and the language of teachers and parents, class assignments, and school forms may serve to stigmatize or exclude adoptive families. These problems can be further compounded for same-sex parent families, who not only encounter—––and often violate––—the assumption of biological relatedness between parents and children in the school context but also face heterosexist language, curricula, and school forms that assume the existence of different-sex parents (Byard, Kosciw, & Bartkiewicz, 2013). Understanding predictors of, and processes related to, parent engagement in adoptive and same-sex parent families is highly relevant to the field of school psychology, as such families become increasingly common and visible. As with any cultural competency, understanding the concerns and interests of adoptive and same-sex parents should inform the work that school psychologists engage in, including assessment, consultation, intervention, and systems change (Nastasi, 2006). School psychologists, as well as other school personnel, will be more effective if they can understand, anticipate, and ideally prevent barriers to school engagement among same-sex and heterosexual adoptive parent families. Indeed, strong and healthy parent-school relationships have the capacity to benefit parents, children, and schools (Beveridge, 2005).

The Parent Context

Parents’ personal characteristics are important to take into account in considering parent– school relationships. For example, parents’ sexual orientation and gender may have implications for how they approach their children’s schooling (e.g., their level of engagement) as well as how schools respond to them (e.g., their receptivity and openness).

Sexual orientation

Although all adoptive families may face marginalization in schools, same-sex parent families face additional issues, insomuch as they violate several assumptions about families. Namely, they violate the assumptions of both parent–child (biological) relatedness and parental heterosexuality (Byard et al., 2013). Their deviation from heteronormative family ideals, in turn, renders them highly visible and thus vulnerable to marginalization, exclusion, and stigmatization.

Some research suggests same-sex parents may actually be more involved in their children’s education, on average, as compared to heterosexual parents. Namely, a survey of over 500 same-sex parents by the Gay, Lesbian, Straight Education Network (GLSEN) found that the parents surveyed—who had children ranging from kindergarten through 12th grade—were more likely to have volunteered at their child’s school (67% vs. 42%) and to have attended events such as Back-to-School night or parent–teacher conferences (94% vs. 77%), compared to a national sample (Kosciw & Diaz, 2008). Such findings suggest that same-sex parents are, as a group, concerned about the quality of their children’s education and the schools of which they are part. Notably, their involvement in schools may be driven by their desire to ensure that their children are not discriminated against. That is, they may feel that their presence makes it harder for the school to ignore, marginalize, or discriminate against their children or families (Goldberg, 2010).

Contrasting data, however, have been reported by Fedewa and Clark (2009), who used the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K) dataset to compare same-sex parent and heterosexual-parent families in terms of their self-reported level of parent communication with the school and the strength of their home-school partnerships. Fedewa and Clark—who, unlike Kosciw and Diaz (2008), focused specifically on parents of young children—found no evidence for differences in parent–school relationships by family type. Thus, a central question is whether same-sex parents will report higher levels of parent involvement in their children’s schools than heterosexual parents.

Also of interest is whether parents’ relationships with teachers and school satisfaction vary by parent sexual orientation. The GLSEN survey—which provides some of the only data on this topic—found that a small number (7%) of parents reported negative treatment or comments related to being lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ) by teachers; those who reported negative treatment also felt less comfortable talking to school personnel about their families (Kosciw & Diaz, 2008). Perhaps these low numbers reflect same-sex parents’ efforts to place their children in diverse, affirming school settings, when possible (e.g., when they have sufficient resources); indeed, same-sex parents have been found to consider the school’s gay-friendliness and overall approach to diversity in choosing schools (Goldberg & Smith, 2014; Mercier & Harold, 2003). To the extent that they are able to place their children in affirming environments, this environment may result in few homophobic incidents and generally strong family–school relationships.

Parent gender

The sexual orientation of parents may also moderate differences in engagement based on gender. Indeed, the literature on parents’ school-based engagement has historically focused on heterosexual mothers. Thus, the finding that mothers are more involved in children's education appears to be related to, and a reflection of, traditional beliefs about gender roles and gender-based patterns of power in society (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, 1997; Palm & Fagan, 2008). Whether this finding holds up in same-sex parent families—who tend to be more egalitarian in terms of parental roles (Goldberg, 2010)—is unknown. In a review of the parenting literature, Biblarz and Stacey (2010) found that parent gender was stronger predictor of parenting than sexual orientation, suggesting that gender may emerge as a significant predictor of parental engagement regardless of parental sexual orientation. It is also possible that gender interacts with sexual orientation, such that, for example, sexual minority mothers and heterosexual mothers may be similarly involved, but sexual minority fathers may be more involved than heterosexual fathers.

The School Context

In considering parents’ relationships with their children’s schools, it is important to consider the dynamic nature of the parent–school relationship, as well as the multiple intersecting contexts within the broader school community (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Mercier & Harold, 2003). In particular we examine parents’ perceptions of their interactions with different aspects of the school community. Thus, we consider parents’ perceptions of how schools relate to them (i.e., what type of contact parents receive from schools about their child) as well as their perceptions of and interactions with other parents at their children’s schools (i.e., the broader school context). Finally, we consider whether parents’ perceptions of the school’s integration of, and sensitivity to, cultural and adoption issues, are related to school engagement.

Perceptions of school initiated contact

Feuerstein (2000) observed that many studies of parents’ school engagement have been ineffective in providing a clear understanding of what factors encourage parents to be engaged in their children’s education. He suggested that one reason for this is that scholars “overemphasize static, individual-level variables like SES, ethnicity, and family structure” (p. 29). These types of variables “do not acknowledge the dynamic aspects of the parent-school relationship and are not easily influenced by educational or social policy” (p. 29). Thus, school-related factors, such as school efforts to contact parents, may be more important to explore as contributors to parents’ school engagement. For example, Feuerstein found that parents’ involvement in the school was significantly influenced by level of school contact, such that parents who reported more school contact about their children’s grades and behavior volunteered more.

Few studies differentiate between school contact about “positive” versus “negative” issues. One exception is a study of school-initiated contact by Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta (1999), which differentiated among topics about which contact was being made (academic problems, behavior problems, health, positive issues, and family support) and found that kindergarten families received more contact about negative topics (e.g., behavior and academic problems) than preschool families, which in part reflected a general trend towards increased school contact between preschool to kindergarten. Unknown is how contact about negative versus positive topics may be differentially related to parent engagement. Perhaps contact about negative topics negatively influences parent–teacher relationships and school satisfaction but positively influences involvement, whereas contact about positive or neutral topics is positively related to all three dimensions of engagement (involvement, relationships, and satisfaction).

Little research has examined same-sex parents’ experiences of being contacted by their children’s schools. One exception is the GLSEN study conducted by Kosciw and Diaz (2008), which found that same-sex parents reported more contact about both positive or neutrally charged issues (e.g., volunteer opportunities; 58% vs. 40%) and negatively charged issues (e.g., their child’s behavior problems: 21% vs. 12%), compared to a national sample. The authors, however, did not examine whether these different types of contact were related to parents’ school involvement.

Acceptance by other parents at the school

Feeling accepted by and connected to other parents, as well as socializing with other parents, may affect parent engagement, such that parents who form ties with other parents feel more connected to and are more involved at their children’s schools (Malsch et al., 2011). By extension, parents who feel disconnected from their community in general and the other parents at their children’s schools may be less engaged (Hindman, Miller, Froyen, & Skibbe, 2012; McKay, Atkins, Hawkins, Brown, & Lynn, 2003), especially in minority (e.g., racial minority) communities (Simoni & Perez, 1995; Turney & Kao, 2009). The absence of a community of other parents who share a central feature of one’s identity can inhibit a sense of connection to the school (Hindman et al.); in turn, parents who feel excluded by the other parents at the school may detach from the school community (Levine-Rasky, 2003).

Some scholars (e.g., Durand, 2011) have conceptualized parent–parent relationships as a form of social capital that affects parents’ school engagement. In a study of Latino families, Durand found that stronger communication with other parents helped to increase parents’ school involvement, thus creating a possible avenue through which Latino parents might develop a collective voice within the school. Not all studies, however, find that perceived social support from parents is related to school involvement. For example, in a study of African American parents, support from other parents was unrelated to school involvement (McKay et al., 2003).

Same-sex parents’ perceptions of acceptance and inclusion by other parents have rarely been examined. One exception is the GLSEN survey (Kosciw & Diaz, 2008), which found that a quarter of the same-sex parents surveyed reported mistreatment (e.g., being whispered about or ignored) by other parents at school. No research has systematically examined adoptive parents’ sense of connection to other parents, although qualitative work has reported feelings of alienation from biological parents in this population (Goldberg, Downing, & Richardson, 2009; Miall, 1987). Unknown is how perceived connection to other parents is related to same-sex and adoptive parents’ school engagement (i.e., their involvement, relationships, and satisfaction).

Perceptions of schools’ sensitivity to diversity

Misinformation and stigma related to adoption are still pervasive in the broader society (Goldberg et al., 2009; Miall, 1987) and may trickle down into the attitudes and practices of school personnel. Teachers, for example, may fail to attend to the multiple dimensions of difference that may impinge upon the identity or experiences of adopted children (Enge, 1999). They may also neglect to discuss racial or family diversity in the classroom, perhaps because they believe that young children are too young to understand these issues (Husband, 2012), despite evidence to the contrary (Park, 2011). Thus, from the perspective of adoptive parents, their children’s schools’ inclusiveness of adoptive, racial, and cultural issues may be salient and have implications for parents’ level of involvement in the school, their relationships with teachers, and their overall assessment of and satisfaction with the school.

Little research has examined adoptive parents’ perceptions of teachers’ sensitivity to issues of adoption, culture, and race. One exception is a study by Nowak-Fabrykowski, Helinski, and Buchstein (2009), which surveyed 23 heterosexual foster parents. They found that most parents reported their children’s teachers and classrooms did not have materials related to adoption and felt that schools could be doing more than they were to incorporate the experiences of adopted individuals and their families into their curricula. In a study of 11 White heterosexual parents with adopted Chinese daughters (ranging in age from 2 to 9 years old), Tan and Nakkula (2004) observed that parents often felt that their children’s schools could be more culturally sensitive.

Some research suggests that same-sex parents may be particularly attuned to schools’ sensitivity to cultural, racial, and family diversity. Mercier and Harold (2003) interviewed 15 female same-sex parent families with children age 6 months to 18 years and found that parents emphasized the importance of sending their children to schools that valued diversity, as they believed that “schools that value diversity of any type are more likely to respond well to lesbian-parent families” (p. 39). Goldberg and Smith (2014) found that racial diversity in particular mattered to same-sex parents when choosing preschools: Female and male same-sex adoptive parents were more likely to consider the racial diversity of the school than heterosexual adoptive parents, regardless of their child’s race. However, this study also found that heterosexual parents perceived higher levels of adoption stigma in their children’s preschools than same-sex parents. The authors suggest that this differential rate of perceived adoption stigma may reflect their greater sensitivity to this form of bias, compared to same-sex parents, who encounter multiple forms of stigma and who thus may be less sensitive to adoption-related insensitivities or more likely to attribute bias to their sexual orientation.

None of the above studies examined how perceived inclusiveness regarding culture, adoption, and diversity are related to parental engagement. Also, the literature is conflicting with regard to whether same-sex parents and heterosexual parents are differentially attuned to or affected by such perceptions, and the implications of such perceptions for school engagement.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

Based on the previously described literature, we pose the following research questions and hypotheses regarding same-sex and heterosexual adoptive parents’ school engagement:

Parents’ School-Based Involvement: We expect that same-sex adoptive parents will be more involved than heterosexual adoptive parents (Hypothesis 1A); women will be more involved than men, regardless of family type (Hypothesis 1B); parents who report more school contact about both positive or neutral topics and negative topics will be more involved, regardless of family type (Hypothesis 1C); parents who report greater acceptance by other parents, and who socialize with other parents, will be more involved, regardless of family type (Hypothesis 1D); and parents who perceive the school as more culturally sensitive and less stigmatizing of adoption will be more involved, regardless of family type (Hypothesis 1E).

Parents’ Relationships With Teachers: We expect that parents who report more school contact about positive or neutral topics will report better parent–teacher relationships, and parents who report more contact about negative topics will report poorer relationships, regardless of family type (Hypothesis 2A). Parents who view the school as more culturally sensitive and less stigmatizing of adoption will report better relationships, regardless of family type (Hypothesis 2B).

School Satisfaction: We expect that parents who report more school contact about positive or neutral topics will be more satisfied with the school, whereas parents who report more contact about negative topics will be less satisfied, regardless of family type (Hypothesis 3A). Parents who perceive their schools as more culturally sensitive and less stigmatizing of adoption will be more satisfied, regardless of family type (Hypothesis 3B).

We do not have hypotheses about how (a) sexual orientation, (b) perceived acceptance by parents, and (c) socializing with parents, may be related to parent–teacher relationships or school satisfaction. As there is not sufficient literature in these areas to speculate about such associations, our examination of these associations was exploratory. We also conducted a series of exploratory interactions. We examined the interaction between sexual orientation and gender in predicting involvement, parent–teacher relationships, and school satisfaction, but we did not have specific hypotheses about the direction of these associations. We also conducted exploratory interactions between (a) cultural sensitivity and sexual orientation and (b) adoption stigma and sexual orientation, out of interest in whether diversity-related variables differentially affect school engagement for same-sex and heterosexual adoptive parents.

Method

Participants

Data were taken from a longitudinal study of adoptive-parent families, conducted by the first author (e.g., Goldberg et al., 2009; Goldberg, Smith, & Kashy, 2010). All 103 couples had adopted their first child 5 years earlier. Participants were included in the current study if their adopted child was in kindergarten.

We used data from members of 35 female same-sex couples, 28 male same-sex couples, and 40 heterosexual couples—all of whom who had adopted their first child 5 years earlier—to examine predictors of parents’ school engagement. Descriptive data from couples broken down by sexual orientation and gender appear in Table 1. Multilevel linear modeling (MLM, in which parents were nested within couples) revealed that parents’ average salaries differed significantly by gender but not by sexual orientation or the interaction between gender and sexual orientation. Specifically, mean annual personal income differed by gender, F(1, 173) = 16.78, p < .001, with men reporting higher personal incomes (M = $93,969, SE = $6,470) than women (M = $56,808, SE = $5,688). (For all analyses of demographic characteristics across groups, unless otherwise reported, the a priori alpha level needed for statistical significance was .05.) The sample as a whole is more affluent than national census-derived estimates for same-sex and heterosexual adoptive families, which indicate that the average household incomes for same-sex couples and heterosexual married couples with adopted children are $102,474 and $81,900, respectively (Gates, Badgett, Macomber, & Chambers, 2007). Across both same-sex and heterosexual adoptive families, there were also significant gender differences in work hours, F(1, 163) = 9.91, p = .002, such that men worked more hours per week (M = 39.24, SE = 1.64) than women (M = 31.57, SE = 1.46). The sample as a whole is well-educated, M = 4.40 (SE = 0.11), where 4 = bachelor’s degree and 5 = master’s degree. MLM revealed no differences in education level by gender or sexual orientation or their interaction.

Table 1.

Table of Descriptive, Control, Predictor, and Outcome Variables

| Same-Sex Couples | Heterosexual Couples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Variable | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) |

| Parent income | $56,928 ($36,064) | $102,891 ($76,869) | $45,077 ($40,988) | $94,816 ($53,078) |

| Parent work hours | 34.71 (14.93) | 39.84 (13.73) | 22.91 (17.89) | 45.57 (6.81) |

| Parent education | 4.38 (0.92) | 4.46 (0.51) | 4.38 (0.66) | 4.39 (0.69) |

| Positive school contact | 12.91 (3.70) | 13.29 (3.47) | 12.26 (3.25) | 11.11 (3.34) |

| Negative school contact | 5.31 (2.43) | 5.51 (1.95) | 5.08 (1.38) | 4.82 (1.19) |

| Acceptance by other parents | 4.18 (0.70) | 4.14 (0.64) | 4.28 (0.73) | 4.08 (0.64) |

| School cultural sensitivity | 3.32 (0.48) | 3.40 (0.46) | 3.19 (0.62) | 3.18 (0.57) |

| School adoption stigma | 1.77 (0.54) | 1.79 (0.59) | 1.81 (0.49) | 1.75 (0.35) |

| Child externalizing behavior | 48.48 (10.19) | 49.43 (12.01) | 49.55 (11.29) | 49.93 (9.64) |

| Parent involvement | 2.28 (0.49) | 2.14 (0.56) | 2.24 (0.44) | 1.99 (0.58) |

| Parent–teacher relationship | 3.37 (0.60) | 3.39 (0.50) | 3.18 (0.69) | 2.81 (0.84) |

| School satisfaction | 3.12 (0.45) | 3.31 (0.32) | 3.01 (0.68) | 3.10 (0.53) |

| Same-Sex Couples | Heterosexual Couples | |||

| M (SD) or % | M (SD) or % | |||

| Child age (months) | 65.45 (6.45) | 68.56 (8.37) | ||

| Parent race (of color) | 12% | 10% | ||

| Child race (of color) | 61% | 62% | ||

| Child gender (boy) | 51% | 54% | ||

| Adoption type | ||||

| Public domestic | 10% | 6% | ||

| Private domestic | 73% | 68% | ||

| International | 17% | 26% | ||

| Public school | 56% | 45% | ||

| Socialize with other parents | 63% | 70% | ||

Across same-sex and heterosexual adoptive families, the adoptive parents were mostly White (89%). Their adoptive children, in contrast, were mostly of color (i.e., non-White, including biracial children); 61% of couples adopted children of color. The racial breakdown of parents versus children in this sample is similar to prior studies of same-sex and heterosexual adoptive families (see Farr, Forssell, & Patterson, 2010). Fifty-two percent of couples adopted boys, and 48% adopted girls. Chi square tests of independence showed that the distribution of parent race did not differ by gender, sexual orientation, or their interaction; and, child race and child gender did not differ by family type (female same-sex, male same-sex, and heterosexual).

Children’s average age was 5.56 years, or 66.75 months (SD = 7.25 months); an analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that child age did not differ by family type. Fifty-one percent of children attended public school, and 49% of children attended private schools. Chi square tests of independence showed that school type did not differ by family type.

Measures

Each partner within every couple was asked to complete the following measures separately (i.e., in isolation) from their partner.

Outcome variable

There were three outcome variables employed in this study.

Dimensions of parent involvement: School-based involvement, parent–teacher relationships, and school satisfaction

Three dimensions of parent involvement were assessed using the widely-used Parent–Teacher Involvement Questionnaire (PTIQ; Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1995), which contains three subscales measuring the following: (a) the parent’s involvement in school, (b) the quality of the parent–teacher relationship; and (c) the parent’s satisfaction with the school. Parents responded to items using a 5-point scale, where 0 = never/not at all; 1 = once or twice a year/a little; 2 = almost every month/some; 3 = almost every week/a lot; and 4 = more than once per week/a great deal. The first subscale, Parent Involvement, contained 9 items (e.g., “You volunteer at your child’s school”). One item (“You have attended PTA meetings”) was dropped because it was not deemed applicable to kindergarten-age children. The second subscale, Parent-Teacher Relationship, contained 7 items (e.g., “You think your child’s teacher is interested in getting to know you”). The third subscale, School Satisfaction, contained 4 items (e.g., “Your child’s school is a good place for your child to be”).

The alpha values for the PTIQ three scales are as follows: .75 for Parent Involvement, .88 for Parent–Teacher Relationship, and .82 for School Satisfaction. The scales are intercorrelated (Parent Involvement & Parent–Teacher Relationship, .47; Parent Involvement & School Satisfaction, .34; and Parent–Teacher Relationship & School Satisfaction, .56) but represent distinct constructs with different predictors. Other studies utilizing this measure have reported similar alpha values and similar scale correlations (El Nokali, Bachman, & Votruba-Drzal, 2010; Kohl, Lengua, & McMahon, 2000).

Predictor variables

There were nine predictor variables employed in this study.

Sexual orientation

Sexual orientation refers to whether participants were in same-sex or heterosexual relationships. We examined differences by parent sexual orientation by creating a dummy variable where 1 = same-sex parent and 0 = heterosexual parent.

Parent gender

Parent gender refers to the self-reported gender of each partner in each couple. We examined differences by parent gender by creating a dummy variable where 1 = female and 0 = male.

Contact by school

Parents were asked to indicate the number of times their children’s school had contacted them about various issues, using a four point scale: 1 = none (never); 2 = once or twice (infrequently); 3 = three or four times (sometimes); or 4 = five or more times (a lot). This scale was created and used by Kosciw and Diaz (2008) in the GLSEN survey. The issues were addressed in the following items: (1) Your child's poor performance in school, (2) Your child's problem behavior in school, (3) Your child was having problems with other students, (4) Your child's poor attendance record at school, (5) Your child's school program for this year, (6) Your child's good behavior in school, (7) Participating in school fund-raising activities or doing volunteer work, (8) Information on how to help your child at home with specific skills or homework, (9) Obtaining information for school records, and (10) Your child's future education. Items 1–4 were summed to form a measure of “negative” contact by the school, and items 5–10 were summed to form a measure of “positive” (or “neutral”) contact by the school (Kosciw & Diaz). Both variables (contact about negative topics and contact about positive or neutral topics) were then mean-centered. We do not report alphas for either of these indices, as they are participants’ reports of school contacts about specific topics and thus do not represent unitary constructs.

Perceived acceptance by other parents at the school

To measure parents’ perceptions of being accepted and included by other parents at their children’s schools, we adapted a measure by Goodenow (1993), whose original measure assessed adolescents’ subjective connection to peers. Thus, the original five items assessed how connected the person feels to peers at their school, and we adapted these so that they assess parents’ perceptions of acceptance and inclusion by the other parents at their children’s school. Parents responded to five items (e.g., “Other parents at this school are friendly to me” and “Other parents at this school are not interested in people like me” [reverse scored]) on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all true; 5 = very true). Goodenow (1993) reported construct and content validity evidence and good internal consistency for the original measure (alpha = .88) from a sample of 755 adolescents. In our study, the alpha value for the scale (which was mean-centered) was .89.

Socialization with other parents at child’s school

Parents were asked whether they socialized with other parents at their children’s schools (1 = yes, 0 = no).

Cultural sensitivity

To measure parents’ perceptions of their children’s schools’ cultural consciousness, we used the cultural sensitivity subscale (4 items) from the School Receptivity Questionnaire (Sanders, 2008), which was developed to assess various dimensions of school receptivity. Items such as “My teacher makes culturally sensitive statements” and “My child’s teacher is well-trained to deal with parents and students from different ethnic and racial backgrounds” were answered on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Sanders reported construct validity evidence and acceptable internal consistency for the subscale (alpha = .80) from a sample of 339 parents of school-aged children. In our study, the alpha value for this subscale (which was mean-centered) was .79.

Perceived adoption stigma

Perceived school stigma due to adoptive status was assessed using an 8-item measure (Goldberg & Smith, 2014), the development of which was informed by empirical and popular press literature (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2012; Kosciw & Diaz, 2008). The measure assesses perceived mistreatment and exclusion by teachers, school personnel, and other parents, related to the child’s adoptive status. Parents responded to the following six items using a 5-point scale (1 = not at all true, 5 = very true): (1) I have felt that my parenting skills were questioned because I am an adoptive parent, (2) I have felt mistreated by school staff because I am an adoptive parent, (3) I have felt that staff members/school personnel treat my child differently because he/she is adopted, (4) My child’s teacher uses language that acknowledges adoptive families (reverse scored), (5) My child’s teacher sensitively handles assignments that could be hurtful to adoptive families (e.g., family trees) (reverse scored), and (6) My child’s school uses forms that allow families to identify themselves in the way that they choose (reverse scored). In addition, parents responded to the following two items using a different 5-point scale (1 = not at all excluded, 5 = very excluded): (1) To what degree do you feel excluded from your child’s school on the basis of your status as an adoptive family? and (2) To what degree do you feel excluded by the parents of your children’s peers on the basis of your status as an adoptive family? Goldberg and Smith reported acceptable internal consistency for the scale (alpha = .71) with a sample of 210 lesbian, gay, and heterosexual parents of preschool-aged children. In this sample, the alpha value for the measure (which was mean-centered) was .72.

Child behavior problems

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL/1.5-5; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) designed for children 1.5-5 years, consists of three domains: Internalizing Problems, Externalizing Problems, and Total Problems. We used the Externalizing Problems score as a predictor variable in follow-up analyses. Parents responded to 100 items regarding how often their child displayed various problems using a 3-point scale (0 = not true; 1 = somewhat/sometimes true; 2 = very/often true). We transformed the raw scores into standard T scores, which were mean-centered. Higher scores represent more symptoms. In the non-referred standardization sample of the CBCL/1.5-5, the mean T score for parent reports was 50.20 (SD = 9.90) for the Externalizing Problems scale, and the mean T score for the clinically referred sample of the CBCL/1.5-5 was 61.70 (SD = 11.10) for the Externalizing Problems scale (Achenbach & Rescorla). In our sample, the mean T score was 49.19 (SD = 10.75). The CBCL/1.5–5 has demonstrated good internal consistency and test–retest reliability in heterosexual and same-sex parent samples (Farr et al., 2010). The alpha value was .90 in the current sample.

Control variables

There were five control variables employed in this study.

Education

Parents were asked to indicate where their level of education fell on a 6-point scale, where 1 = less than high school education, 2 = high school diploma, 3 = associate’s degree or some college, 4 = bachelor’s degree, 5 = master’s degree, and 6 = Ph.D./M.D./JD. We included level of education (mean-centered) as a control variable, in that greater access to education and income contributes to a sense of investment in and entitlement to education by parents; whereas parents with fewer educational and financial resources may feel alienated by their children’s schools and teachers (Machen, Wilson, & Notar, 2005). Indeed, research is fairly consistent in finding that more educated parents tend to be more involved in children’s school lives (Hindman et al., 2012; Waanders et al., 2007) but do not necessarily have stronger relationships with teachers (Waanders et al.).

Personal income

Each parent was asked to report on his or her annual salary. We used the parents’ estimated annual salary (divided by 10,000, and mean-centered) as a control variable given its association with parents’ school involvement and engagement, whereby, for example, parents with less income are more likely to be involved in volunteering and the like (Arnold, Zeljo, Doctoroff, & Ortiz, 2008; Durand, 2011).

Work hours

Parents’ work hours per week (mean-centered) were included as a control variable, as parents’ work hours and schedule may inhibit school involvement and undermine parent–teacher relationships (Malsch et al., 2011). Both working more hours (Weiss et al., 2003) and having interfering work schedules (Hindman et al., 2012) have been linked to less school involvement, and Fantuzzo, Perry, and Childs (2006) found that parents who worked full time were less satisfied with their children’s educational programs than those who worked less than full time.

Child age

Parents were asked to indicate the age of their child at the time of the interview. We included child age in months (mean-centered) as a control variable. We suspected that parents of younger children (or children in their first year of kindergarten) might be more involved than parents of older children, in light of research showing that parents may be especially involved during the initial transition to kindergarten (McIntyre et al., 2007).

School type

Parents were asked to indicate whether their child attended a public or private preschool. School type was dummy coded such that 1 = public and 0 = private school. We controlled for type of school based on research suggesting that insomuch as parents who send their children to private school chose that school (i.e., over public school and possibly other private schools), they may in turn be more satisfied with the school (Warner, 2010) and more engaged in the schools (Goldring & Philips, 2008). Notably, some research (e.g., Hashmi & Akhter, 2013) has found few differences in parent involvement as a function of school type.

Procedures

Participants in this study were originally recruited during the pre-adoptive period (while couples were waiting for a child). Inclusion criteria were (a) couples must be adopting their first child and (b) both partners must be becoming parents for the first time. Adoption agencies throughout the United States were asked to provide study information to clients who had not yet adopted; this information was typically in the form of a brochure that invited clients to participate in a study of the transition to adoptive parenthood. We explicitly invited both same-sex and heterosexual couples to participate, because a goal of the study was to understand how same-sex couples, specifically, experienced the transition to adoptive parenthood. Toward this end, United States census data were utilized to identify states with a high percentage of same-sex couples (Gates & Ost, 2004), and effort was made to contact agencies in those states. We recruited both heterosexual and same-sex couples through these agencies, in an effort to match couples roughly on geographic status and financial resources. Over 30 agencies provided information to their clients; interested couples were asked to contact the principal investigator for details. Because some same-sex couples may not be “out” to agencies about their sexual orientation, several national LGBTQ organizations also assisted with recruitment. For example, the Human Rights Campaign posted a description of the study on their Family-Net listserv, which is sent to 15,000 people per month.

Participants in the study completed in-depth questionnaires before the adoptive placement, 3 months post-placement, 1 year post-placement, 2 years post-placement, 3 years post-placement, and 5 years post-adoptive placement. Data for the current study come from the 5 years post-adoptive placement assessment. Five years post-placement, parents were contacted and asked to complete an in-depth set of questionnaires, including closed- and open-ended items, which focused on their experiences with their children’s kindergartens. Both partners in each couple were asked to complete the packet. Of the 47 eligible heterosexual adoptive couples who were contacted, 7 declined or did not respond (15%); of the 37 eligible female adoptive couples who were contacted, 2 declined (5%); and of the 30 eligible male adoptive couples who were contacted, 2 declined (7%).

Analytic Strategy

Data were missing for 10 persons in the 103 couples: 2 sexual minority women, 2 sexual minority men, 5 heterosexual men, and 1 heterosexual woman. For all analyses, there were 196 persons nested in 103 couples. Because we examined partners nested in couples, it was necessary to use a method that would account for the within-couple correlations in the outcome scores. Multilevel modeling (MLM) permits examination of the effects of individual and dyad level variables, accounts for the extent of the shared variance, and provides accurate standard errors for testing the regression coefficients relating predictor variables to outcome scores (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). MLM adjusts the error variance for the interdependence of partner outcomes within the same dyad, which results in more accurate standard errors and associated hypothesis tests. Another methodological challenge is introduced in the study of dyads when there is no meaningful way to differentiate the two dyad members (e.g., male and female). In this case, dyad members are considered to be exchangeable or interchangeable (Kenny et al.). The multilevel models tested were two-level random intercept models such that partners (Level 1) were nested in couples (Level 2; see Smith, Sayer, & Goldberg, 2013). To deal with intracouple differences, the Level-1 model was a within-couples model that used information from both members of the couple to define one parameter—an intercept, or average score—for each couple. This intercept is a random variable that is treated as an outcome variable at Level 2. Predictor variables that differed within couples (gender, income, work hours, education, acceptance by parents, socialization with parents, cultural sensitivity, and adoption stigma) were entered at Level 1. Predictor variables that varied between couples (sexual orientation, child age, school type) were entered at Level 2. Continuous predictor variables were grand mean-centered and dichotomous variables were dummy coded (0 and 1). Each variable was tested alone and in combination with other variables to test for collinearity. Interactions were created by multiplying mean-centered continuous variables and dummy-coded dichotomous variables. For each of the outcome variables, we estimated a final set of more parsimonious models in which we trimmed nonsignificant predictor variables and included only predictor variables that were approaching statistical significance (p < .10) in either the main effects model or the model with interactions. Findings with a probability value < .05 are interpreted.

Results

In the following sections, we present (a) descriptive findings; (b) findings from our multilevel models predicting parent involvement, parent–teacher relationships, and school satisfaction; and (c) findings from our follow-up analyses.

Descriptive Findings

Descriptive statistics for all continuous and dichotomous predictor variables, control variables, and the continuous outcome variables, broken down by sexual orientation and gender, are in Table 1. As the Table shows, the sample as a whole reported relatively low levels of negative contact and moderate levels of positive contact by teachers. They also reported relatively high levels of perceived acceptance by, and moderate levels of socialization with, other parents. Further, relatively high levels of cultural sensitivity, and relatively low levels of perceived adoption stigma, were reported. Regarding the outcomes, parents reported moderate levels of involvement and relatively high levels of parent-teacher relationship quality and school satisfaction.

For individual-level variables (e.g., income and work hours), we used MLM to examine differences by sexual orientation, gender, and their interaction. As reported in the Participants section of the Method, mean annual income differed by gender, such that men reported higher personal incomes than women; and, weekly work hours differed by gender, such that men reported working more hours per week than women.

Regarding the predictor variables, parents’ reports of positive contact by teachers differed by sexual orientation, F(1, 102) = 5.07, p = .027, with same-sex adoptive parents reporting more contact (M = 13.08, SE = .36) than heterosexual adoptive parents (M = 11.74; SE = .47). Regarding the outcome variables, parents’ perceptions of their relationships with teachers differed by sexual orientation, F(1, 102) = 11.82, p = .001, with same-sex adoptive parents reporting better relationships (M = 3.38, SE = 0.07) than heterosexual adoptive parents (M = 3.01, SE = 0.09). Parents’ school satisfaction differed by gender, F(1, 170) = 2.75, p = .041, with men reporting greater satisfaction (M = 3.21, SE = 0.06) than women (M = 3.06, SE = 0.05).

Intercorrelations among predictor and outcome variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations Among Predictor and Outcome Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parent involvement | -- | |||||||||||||

| 2. Parent–teacher relationship | .47 | -- | ||||||||||||

| 3. School satisfaction | .34 | .57 | -- | |||||||||||

| 4. Child age | −.29 | −.08 | −.07 | -- | ||||||||||

| 5. Public school | −.07 | −.10 | −.14 | .22 | -- | |||||||||

| 6. Income | −.12 | .01 | .08 | −.05 | −.16 | -- | ||||||||

| 7. Work hours | −.22 | −.11 | −.03 | .08 | .03 | .59 | -- | |||||||

| 8. Parent education | .05 | .05 | .07 | −.003 | .02 | .22 | .12 | -- | ||||||

| 9. Positive school contact | .36 | .29 | .30 | .02 | .11 | −.07 | −.11 | .10 | -- | |||||

| 10. Negative school contact | −.16 | .05 | −.17 | .30 | .10 | −.12 | −.07 | .14 | .14 | -- | ||||

| 11. Acceptance by other parents | .37 | .45 | .32 | −.16 | −.16 | −.02 | −.14 | .07 | .23 | −.14 | -- | |||

| 12. Socialization with parents | .35 | .19 | .14 | −.31 | −.15 | .06 | −.02 | .10 | .12 | −.23 | .44 | -- | ||

| 13. School cultural sensitivity | .26 | .54 | .53 | −.08 | −.09 | .16 | .05 | .13 | .19 | −.12 | .43 | .18 | -- | |

| 14. School adoption stigma | −.09 | −.09 | −.13 | .13 | .01 | −.02 | .02 | .95 | −.09 | .18 | −.31 | −.20 | −.21 | -- |

Note. Hypothesis testing was not conducted for the bivariate correlations in order to limit the overall number of statistical tests. Consequently, statistical significance is not reported.

Multilevel Model Predicting Parent Involvement

In the MLM model predicting parent involvement at school, parent sexual orientation, parent gender, positive contact by the school, negative contact by the school, acceptance by other parents, socialization with other parents, school cultural sensitivity, and school adoption stigma were entered as predictor variables (Table 3). In addition, the following control variables were included: child age, school type, parent income, parent work hours, and parent education. Our hypotheses were partially supported. In this main effects model, there was, consistent with Hypothesis 1C, a significant effect of positive school contact on parent involvement, β = .04, SE = .01, t(152) = 3.50, p = .001, such that parents who reported more contact by the school about positive or neutral topics reported more involvement, regardless of family type. Consistent with Hypothesis 1D, perceived acceptance by other parents emerged as significant, β = .13, SE = .06, t(154) = 1.98, p = .049: Parents who felt more accepted by other parents reported being more involved, regardless of family type. Further, consistent with Hypothesis 1D, there was a significant effect of socializing with other parents at the school, β = .18, SE = .09, t(150) = 2.08, p = .040: Participants who reported socializing with other parents reported being more involved, regardless of family type.

Table 3.

Multilevel Models with Parent Engagement Subscales as Outcome Variables

| Predictor Variables | PI β (SE) |

PI with interact β (SE) |

PI trim β (SE) |

PTR β (SE) |

PTR with interact β (SE) |

PTR trim β (SE) |

SS β (SE) |

SS with interact β (SE) |

SS trim β (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1.95 (0.11)*** | 1.98 (0.12)*** | 2.00 (0.09)*** | 3.08 (0.12)*** | 3.07 (0.13)*** | 3.10 (0.06)*** | 3.31 (0.10)*** | 3.30 (0.11)*** | 3.26 (0.07)*** |

| Child age | −0.003 (0.001) | −0.003 (0.002) | −0.004 (0.001)* | 0.001 (0.002) | −0.004 (0.002) | 0.001 (0.002) | 0.001 (0.002) | ||

| School type | 0.03 (0.08) | −0.003 (0.08) | −0.09 (0.09) | −0.06 (0.09) | −0.08 (0.08) | −0.05 (0.08) | |||

| Parent income | −0.001 (0.008) | −0.004 (0.008) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.02 (.009) | 0.001 (0.006) | 0.004 (0.006) | |||

| Parent work hours | −0.005 (0.003) | −0.004 (0.003) | −0.006 (0.002)** | −0.005 (0.003) | −0.005 (.003) | −0.004 (0.002) | −0.003 (0.002) | −0.003 (0.002) | |

| Parent education | 0.007 (0.04) | 0.03 (0.04) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.03 (.04) | −0.02 (0.03) | −0.02 (0.03) | |||

| Parent sexual orientation | 0.09 (0.08) | 0.03 (0.12) | 0.08 (0.08) | 0.23 (0.09)* | 0.26 (.13)* | 0.26 (0.08)** | 0.09 (0.08) | 0.11 (0.11) | |

| Parent gender | 0.08 (0.08) | 0.03 (0.11) | 0.08 (0.09) | 0.12 (.14) | −0.16 (0.07)* | −0.15 (0.08)* | −0.13 (0.06)* | ||

| Positive school contact | 0.04 (0.01)** | 0.04 (0.01)** | 0.03 (0.01)*** | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (.01) | 0.02 (0.009)* | 0.02 (0.009) | 0.02 (0.008)** | |

| Negative school contact | −0.02 (0.03) | −0.03 (0.02) | 0.06 (0.03)* | 0.07 (.03)** | 0.06 (0.02)** | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.04 (0.02)** | |

| Acceptance by parents | 0.13 (0.06)* | 0.14 (0.06)* | 0.13 (0.06)* | 0.27 (0.08)** | 0.23 (.08)** | 0.27 (0.06)*** | 0.06 (0.05) | 0.05 (0.05) | |

| Socializing with parents | 0.18 (0.09)* | 0.22 (0.09)* | 0.19 (0.09)* | 0.02 (0.10) | −0.01 (0.10) | 0.12 (0.08) | 0.12 (0.08) | 0.08 (0.06) | |

| School cultural | 0.13 (0.07) | 0.20 (0.12) | 0.19 (0.07)* | 0.51 (0.09)*** | 0.63 (0.14)*** | .77 (.11)*** | 0.36 (0.06)*** | 0.39 (0.11)*** | 0.41 (0.06)*** |

| sensitivity | |||||||||

| School adoption stigma | 0.08 (0.07) | −0.30 (0.18) | −0.24 (0.16) | 0.11 (0.08) | 0.32 (0.21) | −0.08 (0.06) | 0.10 (0.16) | ||

| Sex or x gender | 0.10 (0.15) | −0.07 (0.18) | −0.02 (0.13) | ||||||

| Sex or x cultural sensitivity | 0.02 (0.16) | −0.35 (0.18) | −0.42 (0.15)** | −0.13 (0.14) | |||||

| Sex or x adoption stigma | −0.51 (0.21)* | 0.46 (0.20)* | −0.39 (0.24) | −0.29 (0.18) |

Note. PI = Parent Involvement; PTR = Parent-Teacher Relationships; SS = School Satisfaction; Interact = Interactions; Trim = Trimmed; Sex or = Sexual orientation

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Contrary to expectation, sexual orientation, gender, negative contact, perceived cultural sensitivity, and perceived adoption stigma were unrelated to involvement. Of the control variables, child age, school type, income, work hours, and education were unrelated to involvement.

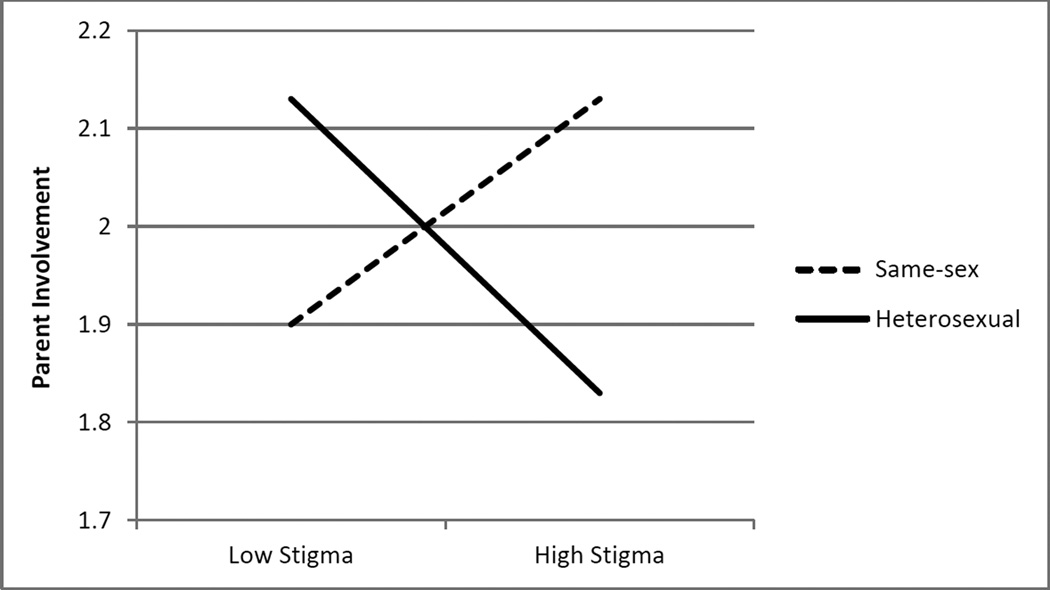

Next, we tested the interactions between sexual orientation and gender, sexual orientation and cultural sensitivity, and sexual orientation and adoption stigma (Table 3). In the model with interactions, the effect of positive school contact remained significant, β = .04, SE = .01, t(152) = 3.78, p = .001, as did the effects of perceived acceptance by other parents, β = .14, SE = .06, t(150) = 2.15, p = .033, and socializing with other parents, β = .22, SE = .09, t(149) = 2.46, p = .014. The interaction between adoption stigma and sexual orientation emerged as significant, β = .51, SE = .21, t(152) = 2.46, p = .015. Examination of this interaction (Figure 1) revealed that heterosexual adoptive parents who perceived high levels of adoption stigma reported being less involved than those who perceived low levels of stigma; perceptions of stigma had the opposite effect on the involvement of same-sex adoptive parents. Among same-sex adoptive parents, high perceived stigma was related to more involvement, whereas low perceived stigma was related to less involvement.

Figure 1.

Interaction of Sexual Orientation and Adoption Stigma Predicting Parent Involvement.

In our final trimmed model, we only included predictor variables with statistical significance levels of p < .10 in the main effects model or the model with interactions. In this model, all previously significant variables remained significant. In addition, child age (β = −.004, SE = .001, t(93) = −2.42, p = .018), work hours (β = −.006, SE = .002, t(147) = −2.84, p = .005), and cultural sensitivity (β =.19, SE = .07, t(164) = 2.52, p = .012), emerged as significant in the trimmed model, such that parents of younger children, parents who worked fewer hours, and parents who perceived their children’s schools as more culturally sensitive, reported greater involvement, regardless of family type.

Multilevel Model Predicting Parent–Teacher Relationships

In the MLM model predicting parent–teacher relationships, the same set of predictor and control variables were included (Table 3). Few of our hypotheses regarding this outcome were supported. In this main effects model, sexual orientation was significant, β = .23, SE = .09, t(95) = 2.62, p = .010, such that unexpectedly, same-sex adoptive parents reported better relationships with their children’s teachers than heterosexual adoptive parents. Also unexpected was the finding that negative school contact was positively related to parents’ relationships with teachers, β = .06, SE = .03, t(134) = 2.25, p = .026, such that parents who reported more contact by the school about negative topics reported more positive relationships with teachers, regardless of family type. Perceived acceptance by other parents was significant, β = .27, SE = .08, t(155) = 3.42, p = .001, such that parents who felt more accepted also reported better relationships with teachers, regardless of family type. Consistent with Hypothesis 2B, perceived cultural sensitivity was positively related to parent–teacher relationship quality, β = .51, SE = .09, t(155) = 5.79, p < .001, such that parents who viewed the schools as more culturally sensitive reported better relationships with teachers, regardless of family type. Contrary to expectation, positive school contact and adoption stigma were not related to parent-child relationships. Also, parent gender, child age, school type, socialization with parents, income, work hours, and education, were unrelated to the outcome.

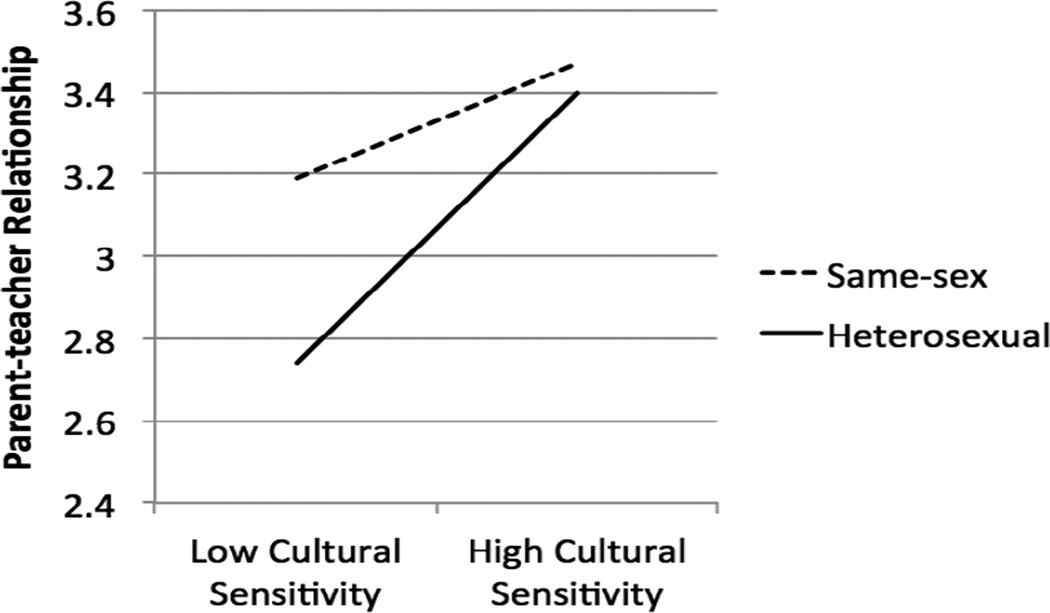

Next, we tested the same set of interactions as with parents’ school involvement. None of them emerged as significant. In the trimmed model, all previously significant variables remained significant. Further, the interaction between cultural sensitivity and sexual orientation emerged as significant, β = −.42, SE = .15, t(154) = −2.84, p = .005. Examination of this interaction (Figure 2) revealed that perceived cultural sensitivity mattered more to heterosexual adoptive parents’ reported relationships with teachers. Heterosexual adoptive parents who perceived high levels of cultural sensitivity in their children’s schools reported better relationships with teacher than those who perceived low levels of sensitivity; whereas the effect of perceived cultural sensitivity on same-sex adoptive parents’ reports of their relationships with teachers was negligible.

Figure 2.

Interaction of Sexual Orientation and Cultural Sensitivity Predicting Parent-Teacher Relationships.

Multilevel Model Predicting School Satisfaction

In the MLM model predicting school satisfaction, the same set of predictor and control variables were included (Table 3). Our hypotheses were partially supported. Namely, consistent with Hypothesis 3A, positive school contact was positively related to school satisfaction, β = .02, SE = .009, t(133) = 2.12, p = .036: Parents who reported higher levels of contact by the school about positive or neutral topics were more satisfied, regardless of family type. Additionally, consistent with Hypothesis 3B, perceived cultural sensitivity was positively related to school satisfaction, β = .36, SE = .06, t(130) = 5.96, p < .001, such that parents who perceived the school as more culturally sensitive reported greater satisfaction, regardless of family type. Regarding the control variables, gender emerged as significant, β = −.16, SE = .07, t(147) = 2.49, p = .014, such that male parents reported greater satisfaction with their children’s schools than female parents, regardless of family type. Contrary to expectation, adoption stigma was unrelated to satisfaction. The following variables were also unrelated to satisfaction: sexual orientation, negative school contact, acceptance by parents, socialization with other parents, child age, school type, income, work hours, and education.

Next, we tested the same set of interactions, but none emerged as significant. Finally, in the trimmed model for school satisfaction, all previously significant variables remained significant. Further, consistent with Hypothesis 3a, negative contact emerged as significant in the final trimmed model, β = −.04, SE = .02, t(168) = −2.69, p = .008, such that parents who reported higher levels of contact about negative topics reported feeling less satisfied with their children’s schools, regardless of family type (Table 3).

Follow-up Analyses

Our unexpected finding that more negative contact from the school was related to more positive parent–teacher relationships prompted us to wonder whether parents who are struggling with their children’s behaviors at home might appreciate hearing from their children’s teachers about the challenges that they are experiencing at school. That is, they may welcome such contact if it is delivered in a supportive way; in turn, such contact may stimulate dialogue and collaboration which fosters closer relationships with teachers. Thus, we tested the interaction between child externalizing problems, measured by the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) and negative school contact, with the expectation that parents who perceived higher levels of behavioral problems, who also reported negative contact, might report more positive relationships with teachers. We also tested this interaction in relation to the other two outcome variables for exploratory purposes. Neither child behavior, β = −.005, SE = .004, t(136) = −1.08, p = .29, nor the child behavior × negative school contact interaction, β = .002, SE = .002, t(128) = .72, p = .47, predicted involvement. Likewise, neither child behavior, β = −.004, SE = .004, t(125) = −.84, p = .40, nor its interaction with negative school contact, β = −.002, SE = .002, t(120) = −.67, p = .50, predicted parent–teacher relationships. Finally, neither child behavior, β = −.004, SE = .004, t(136) = −1.00, p =.92, nor its interaction with negative school contact, β = .003, SE = .002, t(140) = 1.65, p = .11, significantly predicted school satisfaction.

Discussion

This study is the first to examine the school-related experiences of same-sex and heterosexual adoptive parents with kindergarten-age children. We examined multiple aspects of the parent and school context in relation to parents’ school engagement. Our findings hold implications for future research as well as for early childhood educators and school personnel, such as school psychologists, who wish to cultivate learning environments that appeal to and meet the needs of diverse families.

The frequency, nature, and type of communication that schools use with parents has the capacity to shape parents’ school-based involvement, their relationships with teachers, and their overall assessment of the school (Hornby, 2011). In the current study, we observed an interesting set of findings related to school contact and parental engagement. Parents who reported higher levels of positive or neutral school contact were more involved and more satisfied with their children’s schools, a finding that is consistent with prior work (Feuerstein, 2000). Hearing positive feedback may encourage parents to contribute to their children’s school environment and to view their children’s school as a good place for their child to be—although, of course, the opposite may also be true: that is, parents who are more involved may be regarded more positively by teachers, and thus receive more positive feedback about their children.

Surprisingly, parents who reported more negative school contact reported more positive relationships with teachers. We suspected that parents who are struggling with their children’s behaviors and functioning at home might appreciate contact about their children’s negative behavior, thus stimulating greater dialogue and even closeness between parents and teachers. To examine this possibility, we tested an interaction between behavior problems and negative school contact, which was not significant. Thus, perhaps regardless of the actual level of behavior problems that they personally perceive in their children, adoptive parents are relatively open to discussing such issues if teachers raise them. That is, adoptive parents may be particularly vigilant about the potential for adjustment issues in their children (such as those that stem from attachment or loss), particularly as they grow older (Nickman et al., 2005). In turn, they may be particularly primed to discussing issues related to their children’s emotional and behavioral adaptation.

Another important aspect of the school context concerns parents’ relationships with other parents. Limited research has examined how same-sex or adoptive parents’ relationships with other parents impact their school engagement (Kosciw & Diaz, 2008). As expected, we found that when the adoptive parents in the sample felt accepted by other parents, they reported greater involvement at their children’s schools. Perceived acceptance was also related to reports of better relationships with teachers. Thus, it appears that a sense of perceived inclusion may be important to multiple aspects of school engagement—and, likewise, that adoptive parents who feel alienated and excluded by other parents are at risk for disconnection from schools and teachers. Other parents are a key aspect of the school’s atmosphere (McKay et al., 2003), and may be especially important to members of minority groups (e.g., adoptive and same-sex parents) in terms of their sense of belonging and engagement (Simoni & Perez, 1995; Turney & Kao, 2009). Of note is that feeling accepted by other parents was unrelated to school satisfaction. This lack of significant relationship makes sense, conceptually, since our measure of parents’ satisfaction is concerned with the parents’ assessment of whether the school is a good place for their child; in turn, their personal sense of connection to parents should be less important to their assessment of the school’s worth and fit for their child. Of course, as the data are cross-sectional, it is important to consider alternative explanations. Parents who are more involved at may report greater inclusion by other parents because they have had more opportunities to get to know those parents (e.g., via volunteering).

A construct that is related to but distinct from that of perceived acceptance by other parents is socialization with other parents. That is, parents’ subjective sense of being “liked” and “heard” is distinct from interacting with other parents outside of school. The latter represents a behavioral index of socialization that may come in the form of play dates, which directly involve the child. Parent socialization was also related to parents’ reported school involvement. Indeed, socializing with other families may enhance parents’ sense that their child, specifically, is liked and accepted by their peers at school, thus enhancing their willingness to volunteer and attend school events. Again, it may also be that parents’ school involvement fosters more opportunities for connection with other parents—including future play dates. However, given that we assessed parents’ socialization with a single-item measure, this finding should be viewed with caution.

It is notable that parents’ perception of the cultural sensitivity of their children’s schools was the single predictor variable that was related to all three engagement outcome variables: school involvement, parent–teacher relationships, and school satisfaction. The association between perceived cultural sensitivity and parent–teacher relationships, however, depended upon parents’ sexual orientation, such that cultural sensitivity mattered more for heterosexual adoptive parents’ relationships than it did for same-sex adoptive parents. Perhaps other factors were simply more salient to same-sex parents, and thus had more of an influence on their relationships with teachers. For same-sex parents, the cultural sensitivity of the school may be less important or pressing than how open and affirming the school is specifically regarding sexual orientation (Goldberg & Smith, 2014).

The effect of perceived adoption stigma on parent involvement also varied as a function of sexual orientation, although it was unrelated to parents’ reported relationships with teachers or school satisfaction. Heterosexual adoptive parents who perceived high levels of adoption stigma in their children’s schools were less involved than those who perceived low levels of stigma, whereas high levels of perceived adoption stigma were associated with more school-based involvement for same-sex adoptive parents. Thus, just as heterosexual adoptive parents’ reported relationships with teachers were negatively affected by perceiving the school as culturally insensitive, their reported involvement in school activities was negatively affected by perceiving adoption insensitivities and bias. In contrast, same-sex adoptive parents seemed to respond to perceived adoption stigma by increasing their involvement. That is, they may have been responding to perceptions of potential stigma and injustice by advocating for their child (Goldberg, 2010). Prior qualitative work, for example, suggests that same-sex parents often regard issues of teacher insensitivity and ignorance as a “call” for more education and involvement (Mercier & Harold, 2003). Our finding, then, provides further support for this pattern, and cautions us to avoid simplistic interpretations of high levels of parental involvement by sexual minority parents (e.g., assuming that high involvement reflect innate investment in their children’s schools).

Notably, same-sex adoptive parents were not more involved in their children’s schools, overall, as compared to heterosexual adoptive parents. This finding is consistent with some research, such as the study by Fedewa and Clark (2009) which found no evidence for differences in parent-school relationships by family type. However, it conflicts with the findings of the GLSEN survey of same-sex parents (Kosciw & Diaz, 2008). The GLSEN survey obtained data from same-sex parents of children who ranged in age from kindergarten to 12th grade; most children were in elementary or middle school. Thus, it is very possible that differences in parental involvement by sexual orientation do not surface until grade school, when bullying and harassment based on family structure may become more prominent (Goldberg, 2010; Ray & Gregory, 2001). Future, long-term follow-ups of the current sample can assess this possibility.

Unexpectedly, same-sex adoptive parents reported better relationships with their children’s teachers than heterosexual adoptive parents. Perhaps, the higher levels of involvement that Kosciw and Diaz (2008) observed in their sample of same-sex parents of older children manifests differently in the kindergarten set; that is, same-sex parents of young children may focus their energies on building high-quality relationships with teachers as opposed to involving themselves in the school community, in the service of ensuring their child’s safety and well-being.

In contrast to prior work (e.g., Hornby, 2011), women were not more involved in their children’s schools than men, which may have something to do with the adoptive nature of the sample. Adoptive parents may, as a group, tend to be relatively active in the school lives of their children, as they may be on heightened alert regarding potential challenges related to attachment, loss, and learning, which could manifest at school (Nickman et al., 2005). Alternatively, the lack of gender differences in parental involvement may also be a function of the educated, affluent nature of the sample; parents with more resources have fewer constraints on their involvement (Hornby). Surprisingly, we also found that men were more satisfied with their children’s schools, regardless of family type. Perhaps this gender difference in satisfaction reflects gender-based patterns in society, such that women have different or higher expectations for what schools should be doing, and thus their expectations are less easily met (Hornby).

Turning to the control variables, we found no significant relationships between parents’ educational and financial resources and their reports of school involvement, relationships with teachers, or school satisfaction. The lack of significant relationship may in part be related to the fact that the current sample was relatively homogenous, and advantaged, with regard to education level and financial status; indeed, many of the studies linking education and income to parental engagement have examined low-income samples, or samples with more variability in education and income (e.g., Fantuzzo et al., 2006; Waanders et al., 2007). Research on less affluent and less educated adoptive families might find very different relationships between resources and school engagement.

Parents’ work hours had some influence on parents’ school engagement. Parents who worked fewer hours reported more school-based involvement, which is consistent with some prior work (Hindman et al., 2012; Weiss et al., 2003). In general, parents who have more flexible work schedules or work fewer hours likely have more time to foster relationships with schools. Research on successful methods for engaging working parents, particularly in the context of enhancing their involvement, would be worthwhile (Hornby, 2011).

Limitations

There are several key limitations to the current study. First and foremost, the study’s cross-sectional design limits our ability to draw conclusions about causality. For example, as we suggested, it is possible that parents who seek out opportunities for, and engage in, school-based activities become better acquainted with other parents at their children’s schools, fostering greater perceived acceptance and inclusion. Second, our use of a single-item measure to assess socialization with other parents is a limitation. Findings related to this construct should be viewed with caution, and future work should employ an empirically validated measure of parent socialization. Third, our measure of school contact likely did not capture all potential areas about which contact might be made (e.g., child health; Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 1999). Fourth, our cultural sensitivity measure was very broad; future research should consider utilizing a more nuanced and multidimensional measure that taps racial, ethnic, and cultural sensitivity.

We obtained information on parents’ school involvement and parent–teacher relationships from parents only. Obtaining independent measures of these constructs from teachers, as some research has done (e.g., El Nokali et al., 2010), would have enhanced the study. Also, our sample of adoptive parents was largely affluent, well-educated, and White. Thus, although we succeeded in obtaining some aspects of diversity in our sample (i.e., with regard to sexual orientation), we did not have a very socioeconomically diverse sample, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Low-income parents are more constrained with regards to resources and thus may face additional barriers to involvement (Waanders et al., 2007). We also did not examine parents’ home-based involvement (e.g., helping with homework), a domain that is frequently examined alongside school-based involvement, and which may have implications for children’s school success (Tan & Goldberg, 2009). Future work, particularly with elementary-school age children of adoptive and same-sex parents, should consider predictors of school- and home-based involvement.

Implications for School Professionals

Our findings have implications for schools officials who wish to work effectively with diverse families (Hornby, 2011; Ortiz & Flanagan, 2002). We found similar levels of involvement by same-sex and heterosexual adoptive parents, suggesting that strategies for facilitating parents’ involvement may be used for parents of diverse sexual orientations and partnership statuses. Also, our findings indicate that feeling marginalized by other parents is connected to parents’ participation in school life, as well as their perceptions of teachers’ receptivity to their families. Thus, school personnel are advised to engage in efforts to bring parents and families together (e.g., via school picnics and other events), as a means of breaking down perceived barriers among families of different backgrounds and enabling parents to regard each other as sharing a common commitment to their children’s learning and well-being. School psychologists specifically should assess adoptive and same-sex parents’ relationships with other parents as a point of intervention for increasing school connectedness and involvement. In addition to encouraging these parents to develop meaningful relationships with other parents in the school community, school psychologists should also consider the responsibility of the school to (a) improve the school climate and (b) ensure a school environment that is inclusive of all families; and, in turn, should possibly recommend trainings (e.g., on family diversity) to school personnel in order to reach these goals (Byard et al., 2013; Herbstrith, 2014).