Abstract

Proteins self-associate to form dimers and tetramers. Purified proteins are used to study the thermodynamics of protein interactions using the analytical ultracentrifuge. In this approach, monomer – dimer equilibrium constants are directly measured at various temperatures. Data analysis is used to derive thermodynamic parameters such as Gibbs free energy, enthalpy and entropy which can predict which major forces are involved in protein association.

Keywords: sedimentation equilibrium, weak protein interaction, thermodynamics

INTRODUCTION

This unit focuses on the use of analytical ultracentrifugation to directly determine the association constant (Kd) of protein-protein interactions as a function of temperature. The dissociation constant (Kd), which characterizes the strength of protein association in multi-subunit complexes, can be precisely measured by sedimentation equilibrium. The Kd is dependent on local protein interactions and the temperature. The determination of Kd at different temperatures allows the thermodynamic forces which characterize protein association, such as Gibbs free energy, enthalpy and entropy, to be evaluated.

In this section the basic theory of protein association energetics is described followed by Basic and Support Protocols which describe analysis of the eye lens protein β-crystallin which is used as an example of a reversible monomer – dimer system. Particular care is required for sample preparation and this is detailed together with analysis of the sample by sedimentation equilibrium at different temperatures (Basic Protocol 1). The support protocol describes the data analysis of the sedimentation equilibrium profiles and the derivation of the thermodynamic parameters characterizing protein association.

Thermodynamics of Protein Association: Theory and data analysis

In the quantification of protein association using thermodynamics methods the aims are to measure the energetics of protein-protein interactions and to establish the driving forces and mechanism of protein association. In order to achieve a successful measurement of thermodynamics parameters it is necessary to have a high quality pure protein which associates reversibly under the conditions used for sedimentation equilibrium. The quality of protein determines its ability to resist to protein aggregation under the stress caused by the temperature change in the protein environment and the pressure of centrifugal forces for > 25 h.

Quantification of Protein Associations

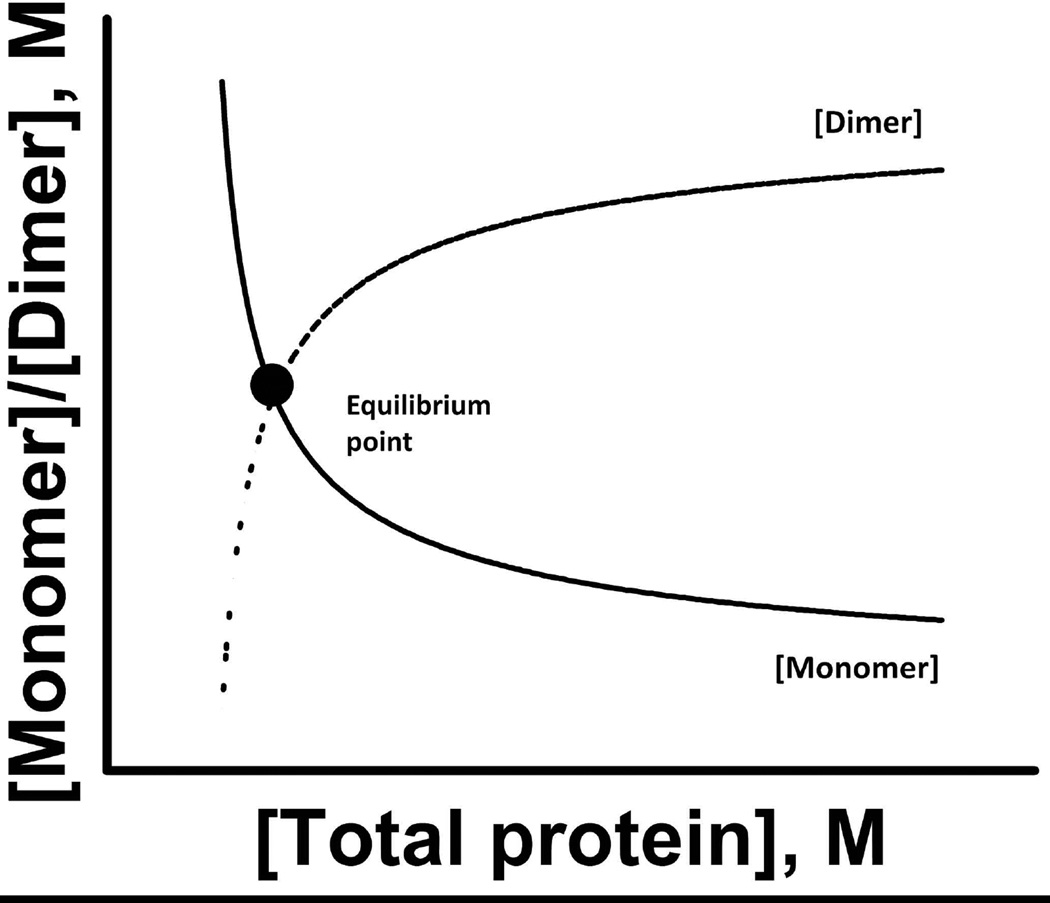

In the simplest reversible protein association, namely a monomer – dimer system, monomers (M) associate to form dimers (D) and dimers dissociate to form monomers. This equilibrium situation is characterized by either a dissociation constant Kd for the dissociation of D into M and has the units of [concentration] or for the reverse reaction, an association constant Ka (reciprocal of Kd) and has units [concentration]−1. With protein concentrations below the Kd, protein is mostly monomeric and with concentrations equal to Kd, half the protein is dimeric (Figure 1). From a physical perspective Kd, indicates the strength of interactions between monomers: the lower the value, the tighter the binding.

| (1) |

Figure 1.

An example of equilibrium between a monomer and dimer is shown. The dimer concentration will increase as the protein concentration increases. In contrast, the concentration of monomers increases as the protein solution is diluted. Changes in protein concentrations of monomers and dimers are shown by solid and dotted lines, respectively. At the equilibrium point the concentrations of monomer and dimer are equal.

Thermodynamics of protein associations can be quantified by studying the effect of temperature on K. Temperature measurements are usually performed at concentrations close to the Kd as shown for the example of monomer-dimer equilibrium (Figure 1). The reversible association and fast dissociation of monomers to dimers and any potential higher oligomeric structures are concentration dependent. These reactions usually maintained by weak interaction forces which create or break transient protein complexes under the permanent pressure of other protein and water molecules. Prior to undertaking the study of a protein association system the stoichiometry of association must be established. For example, is it a monomer – dimer system or a monomer – trimer system or a higher order complex. This can be determined by finding an association model which best fits sedimentation equilibrium curves (this is summarized in (McRorie and Voelker, P. J.1993)). As reliance on any one biophysical technique is unwise, the model should be tested by other methods including for example, gel filtration and ideally gel filtration with on-line light scattering (see UNITS 7.8, 8.3).

Thermodynamic parameters

When the association constant is measured at different temperatures using sedimentation equilibrium it is possible to evaluate thermodynamics parameters of association. Measurement of dimer formation at different temperatures allows dissection of the association free energy into contributions from changes in standard enthalpy, ΔH°, and in the entropy term −TΔS°. In general, the Gibbs free energy of association that measures the association-initiating work can be calculated from the simple relationship:

| (2) |

Here ΔS° is a standard entropy of the system. The reaction isotherm equation shows how Gibbs free energy change is related to association constant, Ka, in a form of the equation:

| (3) |

Combining these two relationships we obtain the Van’t-Hoff equation which links the natural logarithm of the association constant with standard enthalpy and entropy changes:

| (4) |

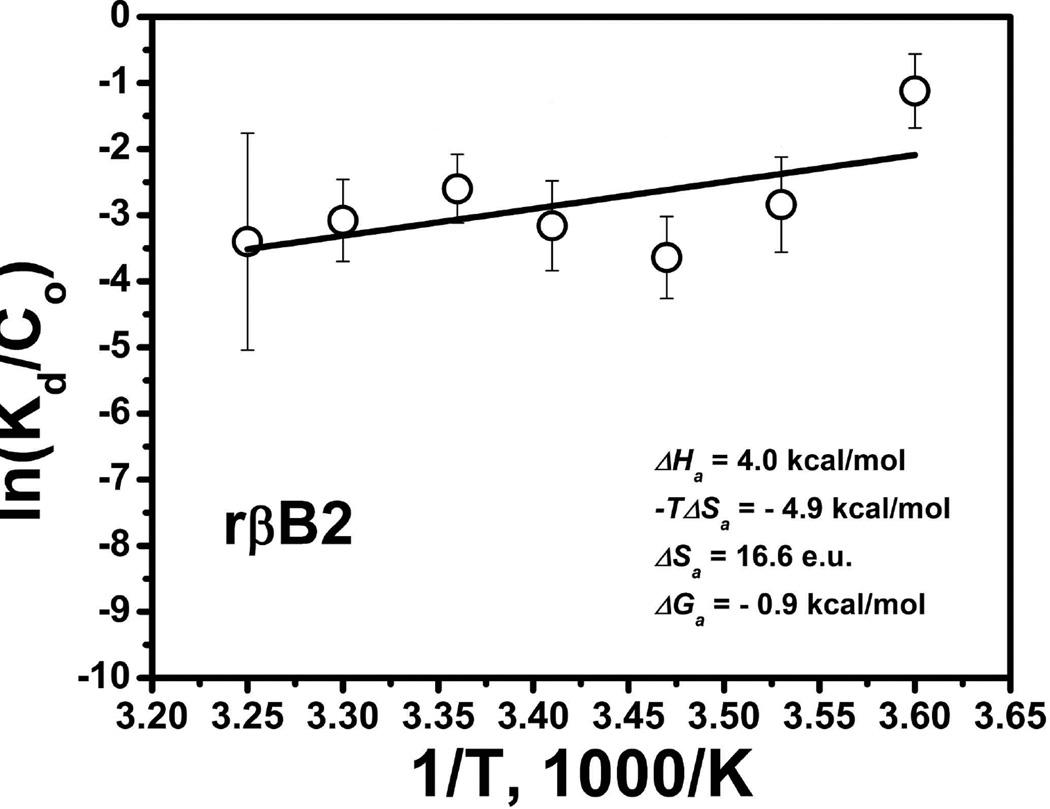

From this equation, a Van’t-Hoff plot of the natural logarithm of the association constant versus the reciprocal temperature gives a straight line. The slope of the line is equal to minus the standard enthalpy change divided by the gas constant, −ΔH°/R, and the intercept is equal to the standard entropy change divided by the gas constant, ΔS° /R. Values of the slope and the intercept could be determined using the linear fit to experimental data points, for example, by using Excel or Origin programs. From the linear fit the standard enthalpy and the entropy of association changes could be evaluated using following formulas: ΔH° = R × slope and ΔS° = R × intercept, respectively. An example of the Van’t-Hoff plot demonstrates the Origin linear fit to the association data and thermodynamics parameters which were determined for β-crystallin B2 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Graphic version of the Van’t-Hoff plot of ln(Ka/Co) as a function of the reciprocal absolute temperature, 1000/K shown in Kelvin scale. Here Ka is dissociation constant obtained from sedimentation equilibrium and Co is the molar concentration in µM. This example is showing data obtained for β-crystallin B2 (Sergeev et al., 2004). From analysis of the plot: ΔH° = 4.0 kcal/mol, −TΔS° = −4.9 kcal/mol, and ΔS° = 16.6 entropy units.

From the above analyses it can be appreciated that using the analytical ultracentrifuge to determine the association constant of a reversibly associating protein system at different temperatures, estimates of thermodynamics parameters such as enthalpy, entropy and free energy changes of protein association can be readily made.

Forces Implicated In Protein Association

Protein association is a complicated process. Stable protein complexes are formed by strong interactions between interacting subunits. Previously, hydrophobic forces were considered as a major force driving formation of stable protein complexes. However, parameters determined including free energy, enthalpy, entropy, and heat capacity changes, often have negative values. So, the stability of protein associates cannot be accounted for on the basis of hydrophobic interactions alone. Other forces such as Van-der-Waals interactions, hydrogen bonds, and salt bridges have to be involved in a stable complex formation. In the case of complexes formed at equilibrium, weak forces are involved in association and fast dissociation into monomers. Equilibrium association of proteins is concentration dependent, in the case of a simple monomer–dimer system; dissociated protein monomers are observed at low and associated dimers at high protein concentrations (Figure 1).

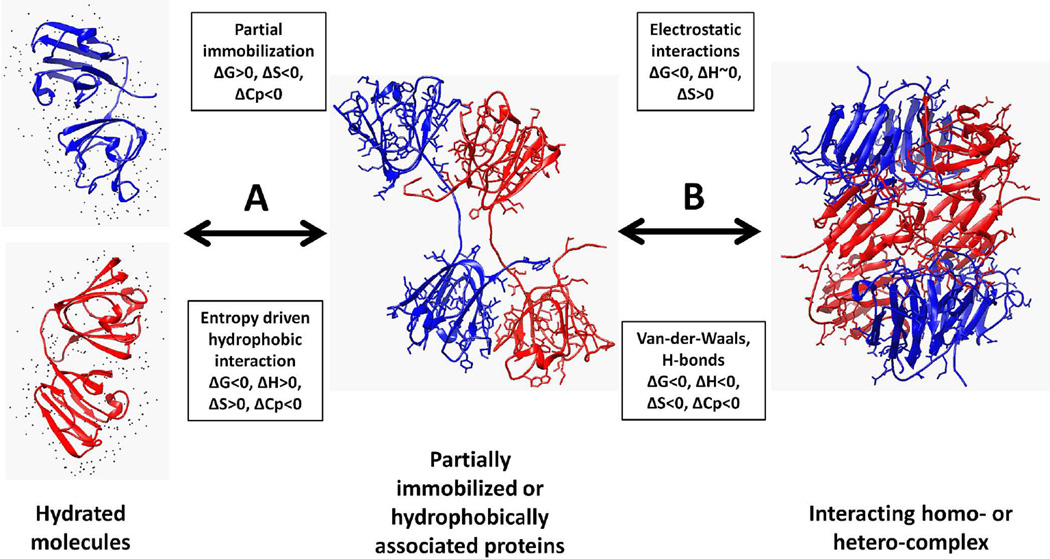

A conceptual model of protein association was suggested by Ross and Subramanian (Ross and Subramanian, S.1981). According to this model the association of two molecules in a stable protein complex is caused by the mutual penetration of hydration layers inducing the disordering of the solvent which is followed by further short-range interactions between molecules (Figure 3). For protein complex formation, the net free energy change for the complete association process is primarily determined by the positive entropy change accompanying the first step and the negative enthalpy change of the second step. In monomer-dimer equilibrium reactions, hydrophobically associated proteins (Figure 3, center panel) might reversibly dissociate into monomers without achieving the more stable quaternary structure (Figure 3, left panel). Examples of protein undergoing self-association by weak hydrophobic interactions are the dimerization β-A3 and β–B2 crystallins which readily reversibly dissociate into monomers (Sergeev et al., 2004). However, there are some homo- and hetero-molecular associations of proteins that are supported by hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, and van der Waals' interactions in the low dielectric interior of the intermolecular interface (Figure 3 right hand panel (Dolinska et al., 2009)). Energetically speaking, the formation of the less stable dimers of β-crystallins A3 and B2 is entropy dominated whereas formation of thee more stable complexes involving βB1-crystallin is enthalpy dominated.

Figure 3.

Thermodynamic view of protein association. In the model originally suggested by Ross and Subramaniam (1981) protein association involves 3 different structural states: monomers (left panel), dimers (center panel), and dimers or other higher associates such as tetramers (right panel) In the left hand panel, two hydrated monomers, either the same or different protein molecules, are shown where the black dots are water molecules which are more ordered (low entropy) compared to bulk solvent. The transition from hydrated molecules to associated dimers is represented by the reversible transition A. This is by partial immobilization (energetics top box) and /or hydrophobic interaction (energetics bottom box). The transition to more tightly associated complexes is represented by transition B and is driven by intermolecular interactions such as an electrostatic (energetics top box) and Van-der-Waal interactions and hydrogen bonds (energetics bottom box). Both transitions A and B are reversible and the signs of thermodynamic parameters in the various boxes are: free energy G, enthalpy H, entropy S and heat capacity C). Side chains for hydrophobic and charged amino acid residues are shown in middle and right panels, respectively.

BASIC PROTOCOL TITLE: Temperature dependent sedimentation equilibrium to monitor protein associate formation and determine dissociation constants

This protocol describes how to perform a temperature-dependent sedimentation equilibrium experiments to measure dissociation constants for protein self-association. As an example we have chosen a monomer – dimer protein system. Typically protein samples showing a single peak on analytical gel-filtration columns and which are greater than 95% pure as judged by SDS-PAGE are used. Prior to performing the analyses the stability of the protein should be checked to make sure it stays in solution for over 24 h at RT. If the protein contains free sulfhydryl groups then a reductant should be included and TCEP is recommended when UV-optics are used. Further, the monomer – dimer system must have a Kd within the range that be studied by the optical system(s) of the ultracentrifuge (10−3 – 10−8 M). The centrifuge is operated at a speed which allows the protein system to form a concentration gradient which is optimum for data analyses (suitable speeds for the molecular weight of the system can be easily calculated as shown in UNIT 7.5). The protein system is allowed to reach equilibrium at, for example, 10 °C, data is recorded and then the temperature is increased, for example, by 5 °C, when the system has re-equilibrated at the new temperature (no change in protein gradient) data is collected and the process repeated. It should be pointed out that the temperature system on the Beckman is very accurate within the range 0– 35 °C. The same protocol applies if dissociation constants are measured for hetero-association of two interacting proteins.

Materials

UV-Vis spectrophotometer (suppliers include Agilent and Beckman)

Stirring devices

Centrifugation was carried out using a Beckman Optima XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge.

Absorption optics, an An-60 Ti rotor, and standard double-sector centerpiece cells are used (Beckman)

Protein, purified and of known concentration (0.2 µM)

Reaction buffer (as recommended by supplier of labeling compound)

Filtered and degassed buffer solution (see UNIT 8.3.11)

Dialysis membranes Snake or Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis kits (Thermo Scientific)

Quartz cuvettes (see UNIT 7.7)

Additional reagents and equipment for dialysis (APPENDIX 3B) or buffer exchange using a desalting column (UNIT 8.3).

NOTE: The amount of protein used for sedimentation equilibrium depends mainly on the availability of the protein. Typically, 3 to 5 mg is required.

NOTE: Always make sure that the solution has reached the required temperature before starting the measurement. Extra time must be allowed for temperature equilibration if the protein solution has been on ice before the experiment.

Prepare sample

-

To prevent potential artefactual association of proteins due to sulfhydryl oxidation, incubate samples (10 µM) for 1 h at room temperature in buffer B containing 10 mM DTT and 1.5 M urea, then dialyze for 24 h at 4 °C against of 1 L of buffer A.

The urea is included to maintain solubility and is optional.

-

Apply the sample to a gel filtration column appropriate for molecule weight range of protein system. Monitor column by SDS-PAGE, pool protein fractions and adjust concentration to about 0.5 mg/ml.

Proteins in the molecular weight range 15 – 80 kD can be analyzed using a Superdex 200 column.

Prior to a centrifugation, add 50 µM of the reductant TCEP to the protein sample.

-

Prepare a reference buffer which exactly matches protein sample.

This is usually the gel filtration buffer plus TCEP. Using UV-absorbance optic in the centrifuge, TCEP is preferred to DTT as the oxidation of DTT produces additional 280 nm absorbance.

-

Samples (~ 90 µL) are subjected to centrifugation using a Beckman analytical ultracentrifuge. Details of the equipment and analytical cells used are described here (UNIT 7.5). For the analysis described here we use the standard double sector cells and duplicate protein samples. The protein samples vs matching buffers are observed using the UV-optical system.

The initial optical density of the samples should be about 0.4 – 0.6 absorption units at 280 nm.

-

Centrifuge proteins at a single temperature, for example 20 °C, prior to the temperature dependence studies. Operate the Optima XLA at a suitable speed appropriate for the molecular weight of the protein system. Data is collected over 16–20 h for the βB1-crystallin at 16, 500 rpm. Data collection is set with the highest resolution scan parameters: mode = step; radial step size = 0.001; replicates 5 – 10 (usually 5).

For the selection of speed to establish equilibrium see (McRorie and Voelker 1993). The protein gradients at equilibrium should be stable with no protein loss due to aggregation.

-

When the protein system has reached equilibrium, increase the speed to 45,000 for 3–4 h (overspeed) to move the protein to the bottom of the cell this allows a baseline absorbance to be established.

Normally all the timings are programmed using the “method” tag in the program window: typically data is collected every 4 h up to 16h then overspeed for 4h and collect data at original spin speed (for example 16,500 rpm).

-

Analyze the data using any one of the available software packages available including Beckman XL-A/ XL-I data analysis software V6.04 (runs using Origin V6.0). To determine the Kd of a monomer – dimer system the following information is required: the density of the solvent used (p) and the partial specific volume of the protein (v-bar). Both these parameters can be estimated using the program SEDNTERP (Laue et al., 1992). Also required is the molecular weight of the monomeric protein and the molar extinction coefficient (ε). The molar extinction coefficient (usually at 280 nm) can be calculated from the amino acid composition (Gill and von Hippel, P. H.1989).

When varying the temperature of the analysis, the solvent density and the partial specific volume v-bar at each temperature must be estimated. Calculation of the v-bar must also take into account addition of, examples, carbohydrate and in the case of membrane proteins, detergents. For highest accuracy the v-bar (approximately the inverse of density) is determined using a density meter, for example DMA 5000 (http://www.anton-paar.com).

-

Once it has been decided that the protein is stable enough for analysis and that the Kd is within an acceptable range (see above comments) one of two strategies are used. For very stable proteins: measure the equilibrium proteins gradients at 5 °C intervals from, for example, 5 – 35 °C. Allow about 8–12 hours for the initial equilibrium to be established (5 °C) then for each subsequent temperature point 4–6 h. At each temperature point scan at least twice to be sure equilibrium is attained as evidenced by no change in protein gradient.

Use duplicate (or triple) protein samples for each protein sample.

-

For less stable proteins the exposure to centrifugation should be limited and overlapping temperature scanning is used: for the range 5– 35 °C, scan for example at 5 – 25 °C and 15 – 35 °C.

In the overlapping scan approach it can be seen that measurements at 15, 20 and 25 °C scans are made twice.

Following the final temperature scan reset the temperature to 20 °C and establishes a baseline by overspeeding at 45,000 rpm for 3–4 h.

-

The data collected by the UV-optical system is in absorbance units and the equilibrium association constant determined (Kobs) must be converted to concentration units as the Kd is expressed in units of M. The machine value of K (Kobs) is determined from the Beckman Origin software for the determination the user is required to select appropriate association model and input the molecular weight of the monomer.

Kobs (εL/2) = Ka for a monomer – dimer and Kobs (εL2/3) = Ka for a monomer – trimer etc., where L is the path length of cell (1.2cm for standard cells) and ε the extinction coefficient (protein A280nm of 1 mg/ml 1 cm cell × molecular weight). Applying these conversions, the Ka is determined and the reciprocal is the Kd which for a monomer dimer has units of M and for a monomer - trimer system M2.

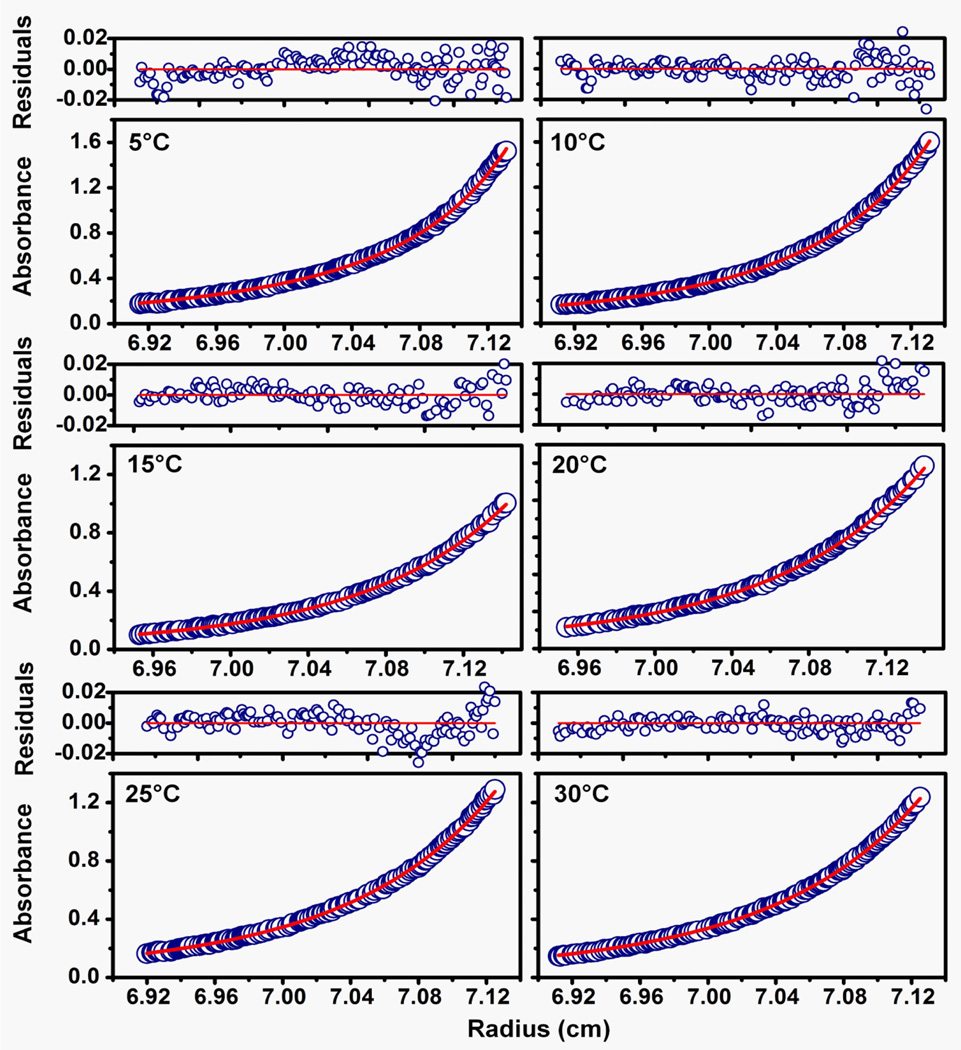

Determine the Kd for the monomer system at the various temperatures. Check data for goodness of fit: when comparing the actual data vs the data fitted to the model, in this case a monomer – dimer system, the difference or residues should be randomly distributed about the zero value (for example see Figure 4).

The most common problem is systematic errors toward the bottom of the cell and this is associated with protein aggregation. This can be minimized to some extent by limiting the data used in the analysis.

When analyzing data from overlapping data collection the first set of K values are Kd1(Tn) measured at temperatures Tn (n = 1,… 5) corresponding to 5, 10, 15 20 and 25 °C. The second group of dissociation constants Kd2(Tn) measured at temperatures Tn (n= 3,… 7) corresponding to 15, 20, 25, 30 and 35 °C. Thus, dissociation constants at temperatures 15, 20 and 25 °C (m = 3, 4, 5) were determined two times in both experiments. From these two sets of data we estimate a scale So showing the differences in two datasets as So = ∑ Kd2(Tm)/∑ Kd1(Tm), where m = 3, 4, 5. Finally, calculate corrected values of dissociation constants Kd1corr(Tm) as Kd1corr(Tn) = So Kd1(Tn), where n=1, 2,…, 5. After the scale correction, measurements from two groups in a single dataset in the temperature range 5–35 °C.

From the individual Kd values the average Kd’s are calculated by averaging the two sets of dissociation constants (or more) collected from duplicate (or triplicate) samples at a given temperature. The two datasets corresponding to overlapping temperature ranges are multiplied by scale coefficients determined from the average of the dissociation constants. Standard root-mean square errors (r.m.s.) which show variability between protein samples should be determined. This procedure corrects inaccuracies in the baseline determination.

Figure 4.

Sedimentation equilibrium data obtained for βB1-crystallin at different temperatures (5–30 °C). Panels are absorbance (bottom panel) and residuals (upper panel) plots for each temperature condition shown for βB1 crystallin. Opened circles show the protein concentration profile represented by the UV absorbance gradients in the centrifuge cell at 280 nm. The solid red lines indicate the calculated fit for monomer-dimer association. Residuals in the top panels show the difference in the fitted and experimental values as function of radial position.

SUPPORT PROTOCOL TITLE: Derivation of Thermodynamic Parameter from dissociation constants

Data manipulations and presentations can be performed with various software packages such as Origin (current version 9) and SigmaPlot (current version 12.3).

-

The linear relationship between free energy ΔG° and the equilibrium constant Ka (Van’t–Hoff) shown in the formula (3) can be used to estimate thermodynamic parameters assuming the heat capacity (Cp) has a zero value.

For nonzero heat capacity the Van’t-Hoff plot notation become more complex and is determined from equation 4 as described previously (Sergeev et al., 2004) and shown below. The temperature dependence of the dissociation constants is used to determine thermodynamic parameters for the reversible monomer-dimer association, by fitting the nonlinear function into the set of experimental dissociation constants determined at different temperatures: ln(Kd/Co)) = (1/R) [ΔCp(293.15/T − ln(293.15/T) − 1) − ΔH°d/T + ΔS°d] (4).

Here T is the temperature in degrees Kelvin (K), Co is the molar concentration of protein in µM, ΔH°d and ΔS°d are changes in enthalpy and entropy due to dissociation and ΔCp is the change in protein heat capacity in the standard state.

To convert temperature: [K] = [°C] + 273.15; the gas constant R has the units: 1.98722 cal K−1mol−1.

Usually this fitting is repeated in two different ways. First, ΔCp is constrained to be zero and formula (4) will have a notation similar to that of formula (3). Second, no constraints are imposed and changes in enthalpy and entropy (ΔH°d and ΔS°d), including possibly nonzero values of ΔCp, determined from the formula 4. If the nonzero ΔCp value is close to zero the expression (4) will become a linear function.

An example of the Van’t-Hoff plot of ln(Ka/Co) as a function of the reciprocal absolute temperature, 1000/K is shown in Figure 2.

REAGENTS AND SOLUTIONS

Filtered buffer solution for diluting protein samples, Buffer A: 50 mM TrisHCl, pH7.2

1 mM EDTA,

150 mM NaCl,

50 µM TCEP (Tris[2-carboxyethyl]-phosphine; Thermo Scientific)

Buffer B: Buffer A containing 10 mM DTT and 1.5 M urea.

Protein “A” and Protein “B” solutions, purified and of known concentration of 0.5 mg/ml.

COMMENTARY

Background Information

Understanding protein–protein interactions requires a full characterization of the thermodynamics of their association. Among the commonly used methods for the determination of thermodynamic parameters differential scanning calorimetry (UNIT 7.9) and circular dichroism as a function of temperature (UNIT 7.6) are widely used. The use of the analytical ultracentrifuge is less common due to the large capital outlay, long analyses times required and selective sample requirements. It’s main advantage that it directly measures protein molecular weights with no assumptions and is based firmly on thermodynamic principles. This means for self associating protein systems the molecular weight distribution of monomeric and associated protein can be easily determined and hence the Ka. In practice this does require the selection of the best fitting model to describe the association. For a concise discussion of model selection see (McRorie and Voelker, P. J.1993). In this unit we have focused on the simplest, and perhaps most common, system a monomer – dimer association. Prior to performing the detailed analyses we have described the mode of association would usually be established using, for example, gel filtration (Sergeev et al., 2000; Sergeev et al., 2004). For a more detailed introduction to the sedimentation equilibrium method see units (UNIT 7.5) and the web site: http://www.bbri.org/RASMB/rasmb.html (‘Reversible associations in structural and molecular biology’ hosted by The Boston Biomedical Research Institute by Walter Stafford). This site has numerous resource links including those to freeware software packages for data analysis. It should be pointed out that we have focused the protocol and discussion on the use of Beckman Optima ultracentrifuge using the UV-optical system for data collection. The Beckman machine can also optionally include interference optics and UNIT 7.5 discusses the various merits of these two systems.

Proteins which undergo self association: Lens eye crystallins

To illustrate the thermodynamic profiling of protein association we focus on a class of proteins from the human eye, the crystallins. The opacity of the eye lens is linked to the molecular associations of these proteins and we have used sedimentation equilibrium as a function of temperature to determine the thermodynamics profiles of homo- and hetero- associations of these proteins. Crystallins are divided in three classes (Bloemendal and de Jong, W. W.1991). The α-crystallins are organized in a small heat-shock protein family. The β- and γ-crystallins are conserved proteins with a common fold of their polypeptide chains and are included in a βγ-crystallins superfamily (Lubsen et al., 1988). βγ-Crystallins have two domains connected by the polypeptide linker. Each domain is composed of two similar “Greek key” motifs packed in a β-sandwich (Bax et al., 1990; Sergeev et al., 1988; Wistow et al., 1983). Mutations in βγ-crystallin genes are associated with a cataract, the disease affecting the eye lens transparency (Willoughby et al., 2005). β-Crystallins associate into dimers, tetramers, and higher-order oligomers (Lampi et al., 2001; Slingsby and Bateman, O. A.1990; Takata et al., 2009). Seven subtypes of β-crystallins have been identified including four acidic (βA1, βA2, βA3, and βA4), and three basic (βB1, βB2, and βB3). Most β-crystallins are monomer-dimer systems (Chan et al., 2008; Dolinska et al., 2009; Lampi et al., 2001; Sergeev et al., 2000).

Concept of ‘open’ and ‘closed’ conformations

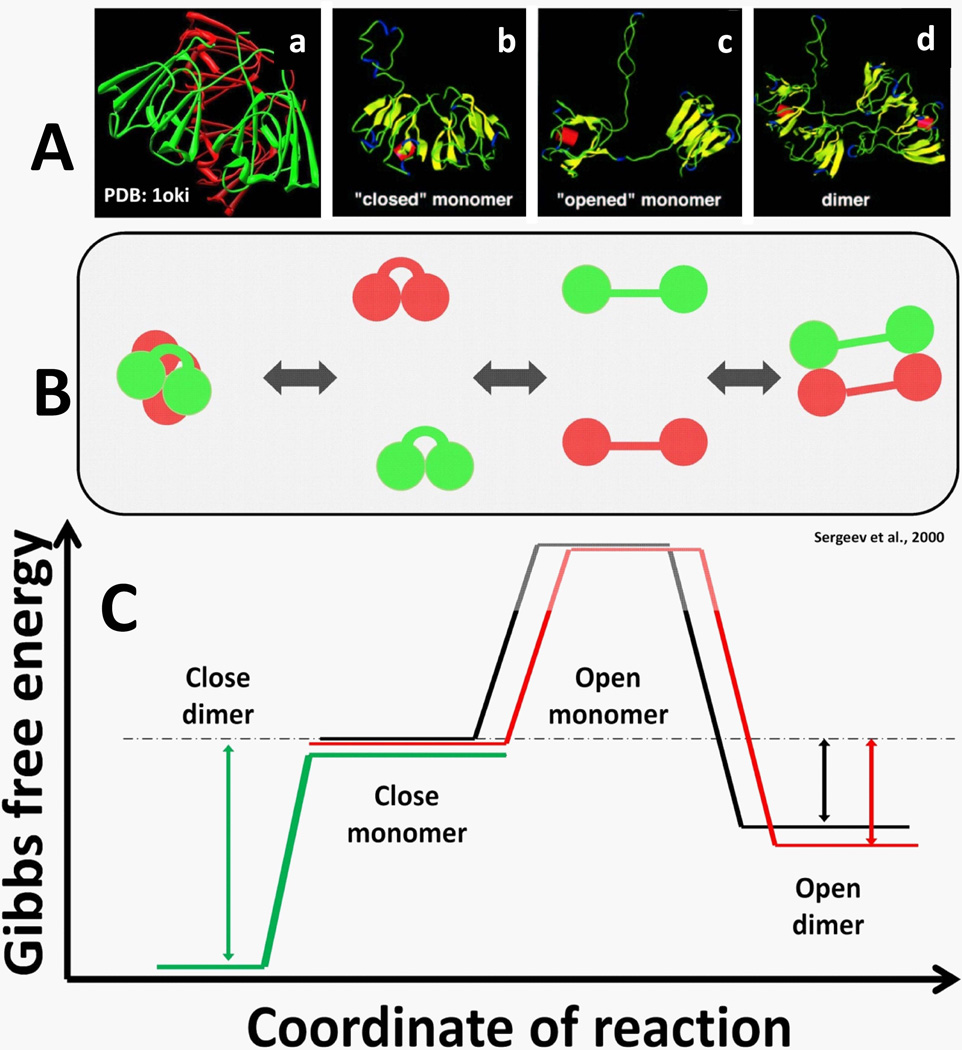

Crystallographic studies show the two domains in γB- and βB2-crystallins adopt either a “closed” conformation in a monomer or an “open” one in a dimer, respectively (Figure 5, Panel A, a–d). In both these conformations, similar surface areas form the inter-domain interfaces (Sergeev and Hejtmancik, J. F.1997). Dimerization of two β-crystallin monomers is proposed to involve their transition from a closed to an open conformation followed by dimer formation as schematically shown in Figure 5, Panel B (Sergeev et al., 2000). The kinetics, equilibrium position and balance of close and open conformers could be affected by interactions of globular domains. The dimerization of one basic β-crystallin may ‘induce’ a conformational shift which favors interaction with acidic β-crystallin (Dolinska et al., 2009).

Figure 5.

Associates of β-crystallins are formed by fast subunit exchange involving open and closed conformers. Panel A: Structures of β-crystallin conformers were determined by protein crystallography. Proteins structures from PDB are shown from left to right (a – d): the βB1-crystallin dimer formed by two closed conformers shown by red and green color (a); monomeric γB crystallin closed monomer (b); βB2-crystallin open monomer (c) and a dimer (d) formed by 2 open conformers. Panel B: A scheme shows fast exchanges to form homo- or hetero-dimer from close (left) or open (right) monomers. In contrast to closed monomers which can exist in solution, open monomers are not stable (higher energy). Two crystallins forming hetero-dimer are shown by red and green. Panel C: Gibbs free energy profiles of β-crystallins as a function of reaction coordinate is shown in the bottom panel. Trajectories for different crystallins are shown by black (βB2), red (βA3), and green (βB1). Open and close dimers show lower association energy.

Energy profile for equilibrium system

The concept of closed and open conformations suggests how homo-and hetero-dimers of β-crystallins can be formed from monomers. Structural models of monomers and dimers proposed to be involved in the equilibrium system are shown in Figure 5, Panel C with a schematic representation of the energy profile for the subunit exchange. In this scheme, monomers in a closed conformation are in equilibrium with dimers having an open conformation via an energetically unfavored monomer intermediate in an open conformation.

Enthalpy and entropy driven association of β-crystallins

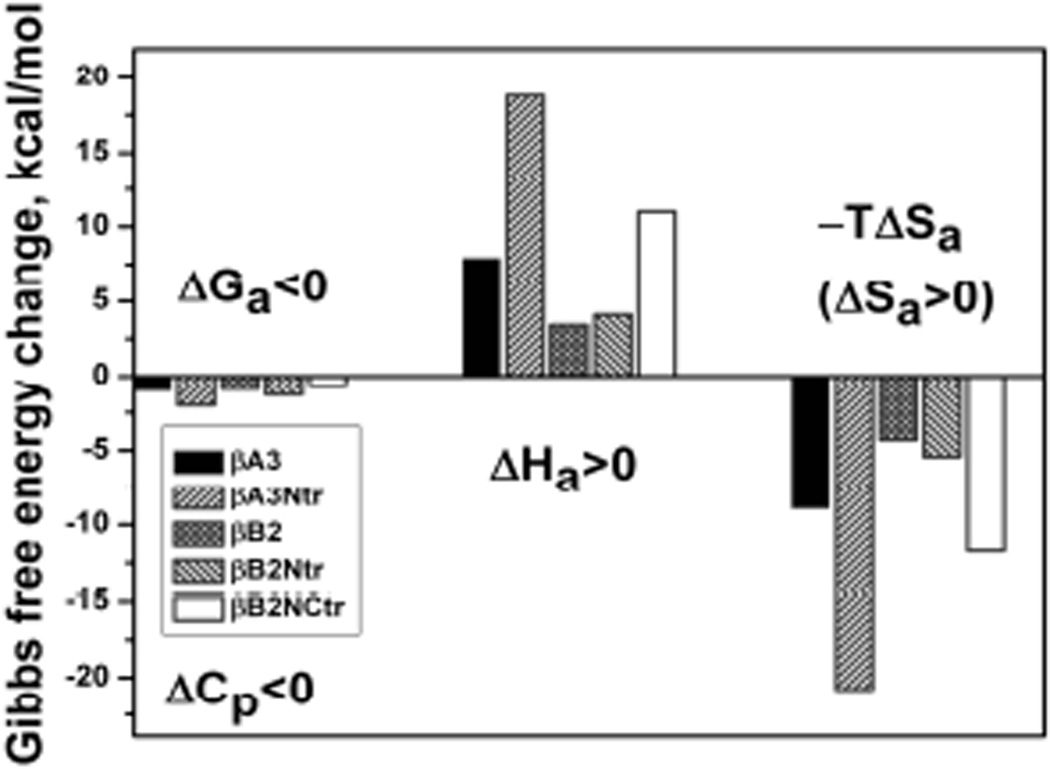

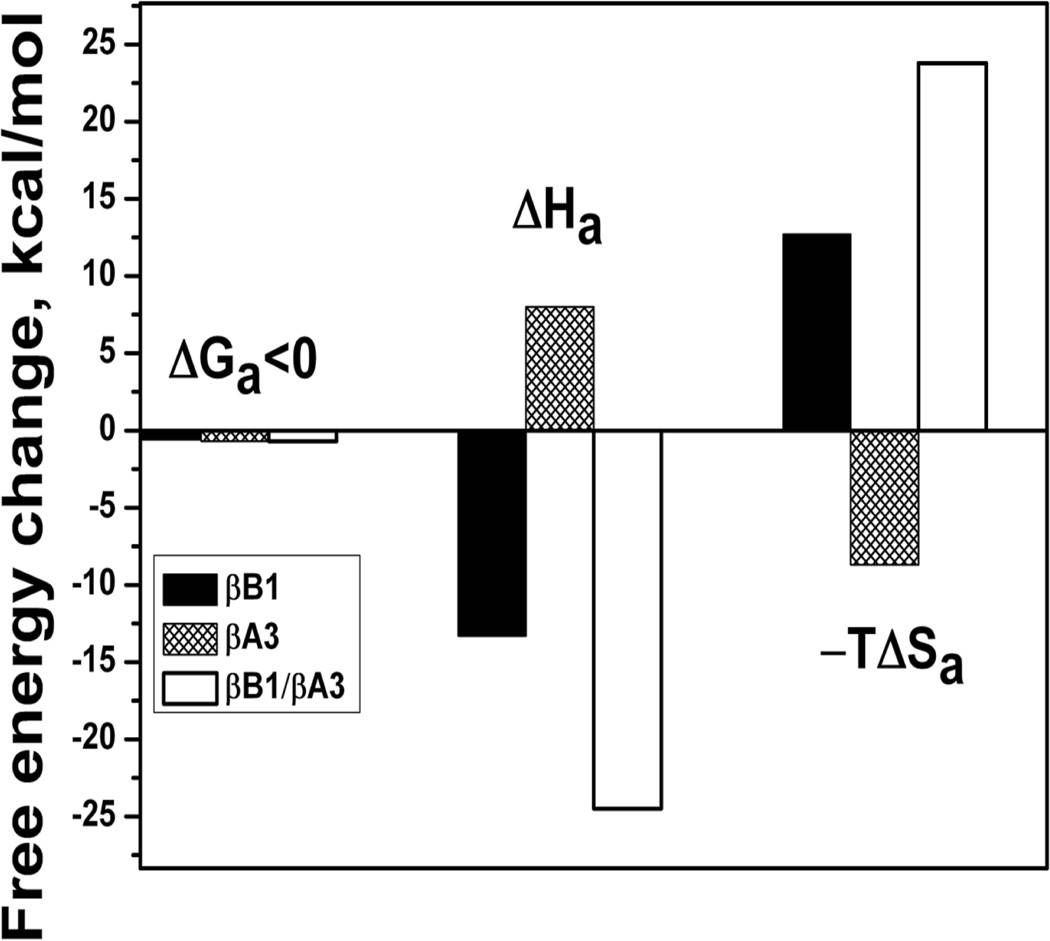

Both βA3 and βB2 crystallins are monomer – dimer systems with a tendency to form tighter dimers at higher temperatures (Sergeev et al., 2004). The self-association of these crystallins, characterized by positive enthalpy and entropy changes, is entropically driven and mediated by hydrophobic interactions. These endothermic associations (ΔH>0) are dominated by hydrophobic effects entropically driven by water as shown in Figure 6. The self-association of βB1 crystallin energetically differs from that of βA3 and βB2 in that its dimers are destabilized at higher temperatures (Dolinska et al., 2012). The thermodynamic profile indicates that both the dimerization of βB1 and formation of the tetrameric βB1/βA3 complex (an association of βB1 dimers and βA3 dimers) are exothermic processes (ΔH<0) as shown in Figure 7. With tetrameric βB1/βA3 formation, decreasing negative values of ΔG confirm that the complex is less stable at higher temperatures. Large exothermic enthalpy change ΔHa and negative entropy ΔSa are accompanied with a negative heat capacity change ΔCp<0. Thus, the profile suggests that tetramer formation is controlled by enthalpy and interactions between the subunits are mediated by van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonds, and salt bridges.

Figure 6.

The thermodynamic signature of βA3- and βB2-crystallins dimer formation shows entropy driven association mediated by hydrophobic interactions.

Figure 7.

The thermodynamic signature of βB1 dimer formation and βA3/βB1 tetramer formation suggests that these associations are enthalpy driven.

In summary:

ΔG = ΔH − TΔS

ΔG: Free energy. Energy available for work and when negative reaction spontaneous.

ΔH: Enthalpy. Bond formation (positive) and bond breaking (negative)

ΔS: Entropy. Measure of structural /conformational disorder. Increase in disorder (positive) and decrease (negative).

Entropic drive association: [ΔH (+) < TΔS (+)] < 0. Enthalpic driven association: [ΔH (−) > TΔS (−)] < 0 (see Figure 6 and 7 for detail).

It is apparent that the thermodynamic forces controlling protein association are similar to those influencing protein folding and denaturation (see Chapter 28).

Critical Parameters

The Protein Sample

To avoid nonspecific interactions, the proteins should be > 95% pure as demonstrated by size-exclusion chromatography followed by the SDS-PAGE. The protein absorbance should be checked by a UV-absorption scan, for example, from 340 – 260 nm. This will allow accurate adjustment of absorbance to required range 0.4 – 0.6 OD at 280 nm. Note: absorbance in the centrifuge will be higher due to the 1.2 cm path length of the centrifuge cell compared to the normal 1 cm path length of cells used in spectrophotometer. Performing an absorbance scan will also allow assessment of excess light scattering due to large protein aggregates. If this is case, low speed centrifugation or filtration will usually resolve the problem. Protein should be stable at the measured temperature range. Having an effective recombinant protein expression system is critical for the successful thermodynamics analysis. The crystallin proteins used were expressed in E. coli as soluble accumulations which did not require protein folding and showed significant stability over wide range of experiment temperatures. Proteins obtained from other expression systems such as, for example, Baculovirus have potential post-translation modifications which may result in protein heterogeneity and also lower protein stability. An important factor in the analysis of the crystallins is the prevention of intermolecular disulfide bond formation which can result in the gradual accumulation of aggregated protein. In some cases, cysteines can be mutated to avoid this problem but often the addition of reductant is used. In the protocol we have used the reductant TCEP (http://hamptonresearch.com/documents/product/hr002534_web.pdf) rather than the more commonly used DTT. Whereas reduced DTT has no absorbance above 270 nm the oxidized form displays a broad band with a maximum at 283 nm which will interfere with protein measurements at 280 nm (Iyer and Klee, W. A.1973).

Temperature

The protein should be stable, show no aggregation and be stable as a reversible association system at equilibrium over the required temperature range chosen for the sedimentation equilibrium experiment. In the protocol described, this temperature range is 5 – 35 °C. During the centrifugation it is essential that samples are at sedimentation equilibrium (no change in the protein gradient) before making experimental measurements. The listed operating temperature range of the Beckman XLA/I is 0 – 40 °C, however, excessive oil vapor at operating temperatures above 35 °C and difficulty maintaining temperatures below 4 °C limit the useful temperature range. Replacing the oil diffusion pump with a turbomolecular pump allows operation to 40 °C and reduces optical fouling. A kit for upgrading the XLI vacuum system is available and new machines (2013) already contain this upgrade (Beckman Coulter).

Buffers

The buffer solutions used in sedimentation equilibrium experiments have to create a stable environment for the native protein, and should not interfere with the sedimentation technique. Buffer solutions should be freshly prepared, filtered and degassed. Absorption of the buffer solution over the relevant spectral range (240–340 nm) should be exactly matched against protein solvent. This is achieved by either dialysis or gel filtration. Small PD10 columns (GE Healthcare) are useful for rapidly exchanging buffers. Buffers should be avoided with strongly absorbing components such as, for example, imidazole used to elute His-tagged proteins (note: pure imidazole is fine but most commercial grades absorb strongly at 280 nm. If high concentrations of salts, glycerol, and sugars etc., are included, the time required for proteins to reach equilibrium will be extended. As mentioned above, oxidized DTT absorbs light at a similar wavelength as tryptophan and should be used fresh or better, replaced with TCEP. If TCEP is used avoid, if possible, using phosphate – based buffers. Perhaps one of most important considerations in selection of a buffer system is the pH as it can greatly influence protein solubility and stability. This can be fairly rapidly screened and analyzing a protein, at, for example, pH 9 vs pH 7; this may make a big difference in maintaining solubility and preventing aggregation.

Troubleshooting

UV-spectroscopy shows a large amount of protein aggregation

This problem is typically due to heterogeneous sizes of proteins in solution. This causes the light scattering from large protein particles or protein aggregates. If protein is aggregating, check the protein UV spectra in the range 240–340 nm, dialyze a protein sample in a fresh buffer and/or clarify the solutions (UNIT 7.2).

UV-spectroscopy shows a poor fit between protein solution and buffer baselines

This problem is due to unsuccessful equilibration of protein sample with the buffer of interest. This problem can be resolved by repeating dialysis with fresh buffer or by using gel-filtration chromatography (rapid desalting can be achieved using Sephadex G25 -PD-10 columns supplied by GE Heathcare)

Protein quality is decreasing during the sedimentation equilibrium experiments over different temperatures

This problem directly relates to the stability of the particular protein under the study. Ideally, the protein will be thermodynamically stable over whole temperature range studied and resistant to protein aggregation during the time of centrifugation. However, with less stable proteins it might be necessary to limit the number of temperature steps measured and use fresh protein to complete the temperature range.

Anticipated Results

Sedimentation equilibrium data

Typical sedimentation equilibrium profiles for the monomer – dimer system at temperatures 5–30 °C are shown in Figure 4. In some of the plots there is a systematic deviation in the residuals at the higher protein concentration (bottom of analytical cell). This is due to small amount of aggregation and this data is usually excluded from the analysis. For a self-associating protein system the Beckman software includes a useful diagnostic treatment of equilibrium data where the apparent molecular weight (calculated at each point along protein gradient) is plotted against protein concentration (absorbance at 280 nm). The plot is basically flat for an ideal (non-associating) protein whereas for an associating system the molecular weight increases from top of cell (low absorbance) to bottom of cell (high absorbance). It is often possible to get a good idea of the stoichiometry of association from this analysis and hence the most appropriate association model to use for fitting the data (A good concise discussion of this is given in (McRorie and Voelker, P. J.1993)). After determination of the Kd values they are plotted as a function of temperature as described in the Support Protocol. An example of the Van’t-Hoff plot for monomer- dimer system is shown in Figure 2 (Sergeev et al., 2004). The thermodynamic parameters characterizing the monomer – dimer systems of various crystallins (Ntr and Ctr refer to N- and C- terminal truncated versions of the indicated crystallins) are shown in Figure 6. These proteins are characterized by entropic driven association. It can be seen that the negative values of the ΔG’s are relatively small compared to the much larger changes in entropy (−) and enthalpy (+). For comparison, we include data from the heteromolecular association of βB1 and βA3. In Figure 7 it can be seen that both the dimerization of βB1 and tetramer formation (βB1 dimers + βA3 dimers) are enthalpic processes. Here again, changes in ΔG are very small and are derived from the difference between larger changes in ΔH (−) and ΔS (+).

Time Considerations

Reducing the protein with DTT and TCEP by partial protein unfolding as descried in the basic protocol usually requires overnight dialysis of protein sample, typically 12 hours, followed by size-exclusion chromatography (~1 hr) and SDS-PAGE (30 min) analysis. Sedimentation equilibrium at different temperatures will require between 24 – 48 h depending on the number of temperature points analyzed per run.

Reference List

- Bax B, Lapatto R, Nalini V, Driessen H, Lindley PF, Mahadevan D, Blundell TL, Slingsby C. X-ray analysis of beta B2-crystallin and evolution of oligomeric lens proteins. Nature. 1990;347:776–780. doi: 10.1038/347776a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloemendal H, de Jong WW. Lens proteins and their genes. Prog. Nucleic Acid. Res Mol. Biol. 1991;41:259–281. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan MP, Dolinska M, Sergeev YV, Wingfield PT, Hejtmancik JF. Association properties of betaB1- and betaA3-crystallins: ability to form heterotetramers. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11062–11069. doi: 10.1021/bi8012438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinska MB, Sergeev YV, Chan MP, Palmer I, Wingfield PT. N-terminal extension of beta B1-crystallin: identification of a critical region that modulates protein interaction with beta A3-crystallin. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9684–9695. doi: 10.1021/bi9013984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinska MB, Wingfield PT, Sergeev YV. betaB1-crystallin: thermodynamic profiles of molecular interactions. PLoS. One. 2012;7:e29227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SC, von Hippel PH. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal. Biochem. 1989;182:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer KS, Klee WA. Direct spectrophotometric measurement of the rate of reduction of disulfide bonds. The reactivity of the disulfide bonds of bovine - lactalbumin. J. Biol. Chem. 1973;248:707–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampi KJ, Oxford JT, Bachinger HP, Shearer TR, David LL, Kapfer DM. Deamidation of human beta B1 alters the elongated structure of the dimer. Exp. Eye Res. 2001;72:279–288. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laue TM, Shah BD, Ridgeway TM, Pelletier SL. Computer-aided interpretation of analytical sedimentation data for proteins. 1992:90–125. [Google Scholar]

- Lubsen NH, Aarts HJ, Schoenmakers JG. The evolution of lenticular proteins: the beta- and gamma-crystallin super gene family. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1988;51:47–76. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(88)90010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRorie DK, Voelker PJ. Self-associating systems in the analytical ultracentrifuge. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Ross PD, Subramanian S. Thermodynamics of protein association reactions: forces contributing to stability. Biochemistry. 1981;20:3096–3102. doi: 10.1021/bi00514a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeev YV, Chirgadze YN, Mylvaganam SE, Driessen H, Slingsby C, Blundell TL. Surface interactions of gamma-crystallins in the crystal medium in relation to their association in the eye lens. Proteins. 1988;4:137–147. doi: 10.1002/prot.340040207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeev YV, Hejtmancik JF. A method for determining domain binding sites in proteins with swapped domains: implications for betaA3- and betaB2-crystallins. 1997;VIII:817–826. [Google Scholar]

- Sergeev YV, Hejtmancik JF, Wingfield PT. Energetics of Domain-Domain Interactions and Entropy Driven Association of beta-Crystallins. Biochemistry. 2004;43:415–424. doi: 10.1021/bi034617f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeev YV, Wingfield PT, Hejtmancik JF. Monomer-dimer equilibrium of normal and modified beta A3-crystallins: experimental determination and molecular modeling. Biochemistry. 2000;39:15799–15806. doi: 10.1021/bi001882h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slingsby C, Bateman OA. Qarternary interactions in eye lens beta-crystallins: basic and acidic subunits of beta-crystallins favor heterologous association. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6592–6599. doi: 10.1021/bi00480a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata T, Woodbury LG, Lampi KJ. Deamidation alters interactions of beta-crystallins in hetero-oligomers. Mol. Vis. 2009;15:241–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby CE, Shafiq A, Ferrini W, Chan LL, Billingsley G, Priston M, Mok C, Chandna A, Kaye S, Heon E. CRYBB1 mutation associated with congenital cataract and microcornea. Mol. Vis. 2005;11:587–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wistow G, Turnell B, Summers L, Slingsby C, Moss D, Miller L, Lindley P, Blundell T. X-ray analysis of the eye lens protein gamma-II crystallin at 1.9 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1983;170:175–202. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]