Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To review the history, epidemiology, etiology, gestational aspects, diagnosis and prognosis of imperfect twinning.

DATA SOURCES

Scientific articles were searched in PubMed, SciELO and Lilacs databases, using the descriptors "conjoined twins", "multiple pregnancy", "ultrasound", "magnetic resonance imaging" and "prognosis". The research was not delimited to a specific period of time and was supplemented with bibliographic data from books.

DATA SYNTHESIS:

The description of conjoined twins is legendary. The estimated frequency is 1/45,000-200,000 births. These twins are monozygotic, monochorionic and usually monoamniotic. They can be classified by the most prominent fusion site, by the symmetry between the conjoined twins or by the sharing structure. The diagnosis can be performed in the prenatal period or after birth by different techniques, such as ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging and echocardiography. These tests are of paramount importance for understanding the anatomy of both fetuses/children, as well as for prognosis and surgical plan determination.

CONCLUSIONS

Although imperfect twinning is a rare condition, the prenatal diagnosis is very important in order to evaluate the fusion site and its complexity. Hence, the evaluation of these children should be multidisciplinary, involving mainly obstetricians, pediatricians and pediatric surgeons. However, some decisions may constitute real ethical dilemmas, in which different points should be discussed and analyzed with the health team and the family.

Keywords: twins; twins, conjoined; twins, monozygotic; pregnancy, multiple; prognosis

Abstract

OBJETIVO

Revisar los aspectos históricos, epidemiológicos, etiológicos, gestacionales, diagnósticos y pronósticos de la gemelización imperfecta.

FUENTES DE DATOS

Se buscaron artículos científicos en los portales PubMed, SciELO y Lilacs, utilizando los descriptores "conjoinedtwins", "multiplepregnancy", "ultrasound", "magneticresonanceimaging" y "prognosis". La investigación no se limitó a un periodo determinado y específico de tiempo. Se complementó la revisión con material bibliográfico presente en libros.

SÍNTESIS DE LOS DATOS

La descripción de gemelos fusionados es legendaria. Se estima que la frecuencia sea alrededor de 1/45.000-200.000 nacidos vivos. Son gemelos monocigóticos, monocoriónicos y usualmente monoaminióticos, que pueden clasificarse conforme al local de fusión más prominente, con la simetría entre los gemelos fusionados o con la estructura de compartimiento. Se puede realizar el diagnóstico todavía en el periodo prenatal o después del nacimiento mediante diferentes técnicas, como ultrasonografía, resonancia magnética y ecocardiografía. Esos exámenes son de suma importancia para el entendimiento de la anatomía del feto/bebé, así como para la determinación del pronóstico y del plan quirúrgico.

CONCLUSIONES

Aunque la gemelización imperfecta sea una condición rara, el diagnóstico prenatal es muy importante para evaluar el local de fusión y su complexidad. Así, la evaluación de esos bebés debe ser multidisciplinaria, implicando principalmente a obstetras, pediatras y cirujanos pediátricos. Sin embargo, algunas decisiones pueden constituirse en verdaderos dilemas éticos, en los que distintos aspectos deben discutirse y analizarse juntamente con el equipo de salud y la familia del niño.

Introduction

The description of conjoined twins is legendary. Its earliest record occurred in 945 B.C., in Constantinople. In this case, the twins were joined at the abdomen and attempted separation occurred after the death of one of them, at age 30. However, the other twin died 3 days later( 1 ).

The most famous twins who opened the doors to a better understanding of imperfect twinning were Chang and Eng, in Siam, in 1811. Both were joined at the lower chest and shared the same liver. Because of the abnormality, the brothers went through a lot of prejudice, because it was believed that women who became pregnant of them would have babies with the same abnormalities. They were prevented from entering France and lived in North Carolina, in the United States. They lived for 63 years, married two sisters, and had 22 children, none of them with the abnormality, indicating the random nature of imperfect twinning( 1 ).

Since then, several reports of new conjoined twins are recorded, but the first published report of successful separation was described by Konig, in 1689. The surgeon, Johannes Fatio, operated the twins joined at the ischium tracking the umbilical vessels to the navel and separately linked the bridge between the two newborns with a silk chord. The bandage fell on the ninth postoperative day, and they survived( 2 ).

Thus, the OBJECTIVE of this study was to review the aspects related to history, epidemiology, etiology, pregnancy, diagnosis, and prognosis of imperfect twinning. For this purpose, scientific articles were searched in PubMed, SciELo, and Lilacs, with the descriptors "conjoined twins", "multiple pregnancy", "ultrasound", "magnetic resonance imaging" and "prognosis". The research was not limited to a specific period of time. We complemented the review with bibliographic material from books.

Epidemiology

Multiple spontaneous twinning occurs in 1.6% of all human pregnancies. Given this prevalence, 1.2% are dizygotic and 0.4%, monozygotic. Among this small percentage of monozygotic, 5% are monochorionic and monoamniotic and only 1% are imperfect pregnancies( 3 ). It is estimated that the frequency of conjoined twins (also called Siamese) is around 1/45.000-200.000 live births. However, with early diagnosis and subsequent termination of pregnancy, the incidence of live births with this condition decreased over the last decade. The proportion of girls is three times higher than that of boys( 4 ). The assisted reproduction techniques were one of the causes of the increase in the chance of monochorionicity and, consequently, in the prevalence of imperfect twinning( 5 , 6 ). With the advent of this technology, the occurrence of conjoined twins increased eight times( 6 , 7 ).

Etiology

Conjoined twins are derived from a single fertilized egg, and there are two theories to explain this phenomenon: 1) fusion theory (more accepted) - when a single fertilized egg is divided into two embryos. The phenomenon occurs between 13 and 15 days after fertilization, resulting in failure to complete division; 2) fission theory - when there is union of two embryos originally separated about 12 days after fertilization( 4 ).

Fused twins are monozygotic; therefore, they will always be of the same sex, with a single placenta, being mainly mono or, more rarely, diamniotic. The incidence of congenital abnormalities is more frequent in monozygotic when compared to dizygotic or single fetuses( 8 ). In the case of fused twins, excluding the incidence of abnormalities related to the location of the junction, there is a frequency of 10 to 20% of the occurrence of major defects. As in separated monozygotic twins, malformations in conjoined twins are often not consistent( 9 ). These include: congenital heart defects, spina bifida, cystic hygroma, changes in limbs, defects in the abdominal wall such as gastroschisis and omphalocele, besides diaphragmatic hernia( 10 ). The high frequency of associated malformations in fused twins can be related to the moment of the fusion, which is assumed to be at the primitive streak stage in the embryonic plate( 9 ). Women with history of gestation of fused twins do not have a higher change of recurrence in a future gestation, having equal chances to the population in general( 11 ).

Classification

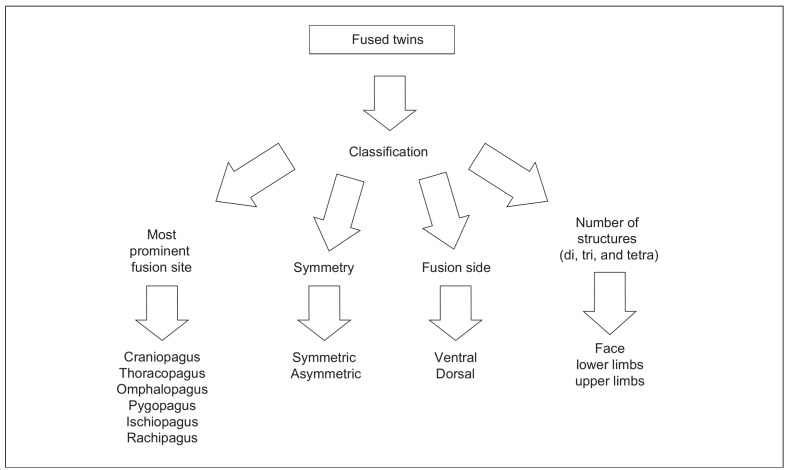

Conjoined twins are monozygotic, monochorionic, and usually monoamniotic, classified according to the most prominent fusion site: craniopagus (skull), thoracopagus (thorax), omphalopagus (abdomen), pygopagus (sacrum), ischiopagus (pelvis) and rachipagus (spine). They may still be divided as asymmetrical (heteropagus) or symmetrical( 12 ). According to Mummigatti and Shamshal( 13 ), cases are classified as symmetric when the twins are well developed and as asymmetric or unequal when a small part of the body is doubled or incomplete. These would include the cases of parasitic twins, or fetus in fetu. The later the fusion occurs, the more incomplete the separation will be, resulting thus in more complex changes.

Other additional terms used include numerals (di, tri and tetra) and the shared structure (face, upper and lower limbs). For instance, conjoined twins with two heads, four arms and both legs are called dicephalus tetrabrachius dipus( 14 ) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Picture of conjoined twins: dicephalus (two heads), tetrabrachius (four arms), dipus (two legs) type.

Spencer( 14 ) also suggests that the fusion side should be divided into two groups: ventral (union at the abdomen with a single navel) and dorsal (union at the neural tube with separate abdomen and umbilical chords). The rostral ventral group includes cephalopagus and thoracopagus. The caudal ventral group includes ischiopagus; the lateral ventral group includes the parapagus, and the dorsal group, the craniopagus, rachipagus and the pygopagus (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Classification of conjoined twins.

The most common type of conjoined twin corresponds to thoracopagus (joined at the chest), observed in 20 to 67% of cases. Fetuses are united by the chest to the navel, and may have a single or individualized heart. They may share the sternal region (20 a 40% of cases), diaphragm, and upper abdominal wall. They are characterized by presenting only one liver and pericardium in 90% of cases, common small intestine in 50% of cases, with union at the level of the duodenum and ileum, besides characteristic omphalocele( 1 ).

The second most common variation is the omphalopagus type, described in 18 to 33% of conjoined twins united by the ventral part. They may have the same union of the trunk, as the thoracopagus, but differ for having separate hearts. They may share the same liver (80%), terminal ileum and colon (33%). Besides, they may join at the level of Meckelâ€(tm)s diverticulum, with separation of the rectum and the presence of omphalocele( 1 ).

The third most frequent variant is the pygopagus type, in which fetuses are united via dorsal and represent 18 to 28% of all fused twins. They present one sacrum and one coccyx, the gastrointestinal tract may have a single or separated rectum, the bladder is described as single in 15% of cases and the spinal cord is separated and there are always sharing of the pelvic bones( 1 ).

The ischiopagus are fetuses united at the ventral part of the umbilicus to the pelvis and represent 6-11% of cases of conjoined twins. They present two sacrum or two pubic symphysis, in general they have a single gastrointestinal tract, and the number of legs may vary from two to four( 1 ).

Craniopagus twins are a rare form of imperfect twinning, with fusion of any part of the skull, excluding the face. They correspond to 2% of cases( 1 ).

The parapagus twins are fetuses with ventrolateral fusion. They may be united from the lower abdomen until the pelvis and correspond to 28% of cases. They always present pubic symphysis and a single urinary tract( 1 ).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of conjoined twins may be performed still in the prenatal period - by means of different techniques, such as ultrasound and fetal MRI - or after birth. Next, we discuss the diagnostic METHODS.

Prenatal diagnosis

The first trimester of gestation is a period of extreme importance for the expectant mother. At this stage, one can diagnose diseases and morphological abnormalities in the fetus. According to Hill( 15 ), it is possible to perform the diagnosis of conjoined twins with 7 weeks of pregnancy.

Ultrasonography

The initial screening by ultrasound allows the diagnosis of numerous conditions, including cases of perfect and imperfect twinning. The first successful diagnosis of conjoined twins was reported in 1977, with 12 weeks of gestation( 16 ).

When we observe the presence of monochorionicity and monoamniocity, the possibility of conjoined twins should be excluded. From the eighth week of gestation, fetal activity increases, which facilitates the differential diagnosis between perfect and imperfect gestation( 17 ). According to Poenaru et al( 18 ), the obstetric ultrasound can diagnose conjoined twins from 12 weeks of gestation.

The difficulty in diagnosing conjoined twins may be due to the fact that the structures are difficult to visualize. Some situations may mimic this situation, especially in very early gestational age: 1) when the membrane that divides the fetuses is thin, and is not easily visible, or may be absent, as in the case of monochorionic placentation; 2) the approximation of the fetuses, especially when they are in the same anatomical level, can give the impression that they are united. The diagnosis in the first trimester should be done with caution, because the amniotic cavity has not reached its maximum volume and fetuses that are in close proximity can create the illusion of conjoined twins( 19 ).

At the first prenatal ultrasound, there are some characteristics that may suggest imperfect twinning: the presence of a single extra-amniotic yolk sac; embryos that move simultaneously; embryo looking bifida observed before 10 weeks of gestation( 20 ). Other striking features are the presence of parallel or opposite spines and no separation of other fetal structures. Polyhydramnios may be present in 50% of cases. Color Doppler may help identify the union of visceral structures( 21 ).

Magnetic Resonance

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a complement to fetal ultrasonography, indicated for the detection of lesions that are not visible or questionable ultrasonographic findings. The MRI primarily assists in the study of cervical and cerebral structures and those complex structures, in which the organs are shared and malformations are present, as in the imperfect twinning. The fetus can be analyzed due to the excellent resolution obtained of the tissues without exposing pregnant women to radiation. The MRI can distinguish soft tissue, in addition to providing a technique such as T2, which is a sequence of short duration with a minimum damage to the image, even with fetal movements. Thus, high-quality images of the fetal organs can be obtained by MRI without sedation. However, it is usually a technique of high cost, which can make it difficult to access. The ideal period for performing it is between 24 and 40 weeks, because there is less fetal movement and organogenesis is complete. The importance of MRI is also due to the fact that it can assist in planning surgery after birth( 22 - 25 ).

When the diagnosis of conjoined twins is confirmed, it is necessary that the classification is made, and, therefore, the determination of the fusion area is essential. Thus, the detailing is important, such as visualization of the heads of twins at the same level, individualization of limbs, and determination of the number of umbilical cords and vessels( 11 ).

Echocardiography

The cardiac assessment by fetal echocardiography must be accurate, as there is a considerable increase in the incidence of congenital heart disease in cases of imperfect twinning, especially when it comes to thoracopagus, because they share the same heart. It is important to assess the degree of complexity of the heart, the presence of associated anomalies, and the probability of postnatal surgery. Fused hearts are easier to evaluate intrauterus, because the amniotic fluid acts as a buffer during the ultrasound examination. If evaluated after birth, the examination may be impaired because the lungs are filled with air( 11 ).

Gestational risks

Twinning has higher perinatal morbidity and mortality when compared to single pregnancies( 26 ). It is associated to low birth weight, pulmonary immaturity, preterm delivery, asphyxia and neurological depression( 27 ).

The risk of poor prognosis in multiple pregnancies, whether perfect or imperfect, is even higher if the maternal age is advanced, as it can be associated with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, abnormalities of labor and cesarean section( 28 , 29 ).

Postnatal diagnosis

It is of paramount importance, after birth, that conjoined twins are submitted to detailed assessment of their anatomy. The use of ultrasound for assessment of central nervous system and thoracic and abdominal organs is critical at this stage. The Doppler can be useful for evaluating the large vessels of the abdomen and the hepatic venous drainage. Echocardiography is mandatory due to the high frequency of congenital cardiopathy in all types of conjoined twins( 30 ).

MRI has also an important role in the postnatal assessment of conjoined twins, particularly those united by the head or the chest. It is the best test to evaluate the cortical fusion in craniopagus conjoined twins. MRI with cholangiopancreatography are ideal for a better evaluation of the biliary anatomy( 31 ).

Regarding the separation surgery, conjoined twins can be classified into two different categories:

Emergency operation: when surgical intervention should be immediate, as in the cases of twins who share the same heart, with cardiac instability; when the abnormality justifies immediate surgical intervention, such as diaphragmatic hernia or omphalocele; when there is a stillborn twin or there are damages on the fusion bridge( 32 ).

Elective intervention: when procedures can be performed later, within a few months of life

Emergency separations have repercussion on the lives of newborns, and the mortality rate is high, in contrast with the elective separations. In cases where there are many anomalies, due to the degree of fusion or complex cardiac connections, the treatment is considered conservative( 32 ). The ideal moment to perform elective separation is with 6 to 12 months of life. Thus, there is time for growth and tissue expansion, with the possibility of acquiring more accurate images of the union and of associated anomalies, for surgical planning.

The purpose of the separation is the survival of at least one of the twins. For the surgical procedure, it is necessary a proper planning by a multidisciplinary team. In the preoperative evaluation, updated radiological examinations are needed so that each surgeon acts on their area, with precise knowledge of anatomy and vascular supply of the twins. Once they assess all organic systems and establish the vascular territories, they decide on the form of distribution of organs between the twins and their order of separation( 33 ).

Anatomopathologic

The importance of autopsy for understanding conjoined twins was well illustrated in the case described by Asaranti et al( 34 ). It was imperfect twinning in thoraco-omphalopagus twins. The autopsy examination revealed that they were joined from below the nipple until the umbilicus. The placenta was single, with one umbilical cord, one artery, and four veins. Each fetus had two pleural cavities and two lungs, but there was a single heart. They shared the same peritoneal cavity. There were two intestines and two gallbladders. The heart and the liver were separated for histopathologic exam. The heart fusion occurred at the level of atria and ventricles, resulting in two atria and two ventricles in single heart, fitting type IV classification by Seo et al( 35 ). These authors classified the variants of heart fusion in degrees, from I to V, considering the degree of fusion and symmetry of heart and great vessels. Thus, in this case, the purpose of the autopsy was to diagnose the type of fusion of the body, the heart, and the great vessels. Such proceeding may help determine the chances of survival in future cases in which the pre-natal diagnosis can be performed with the help of imaging.

Prognosis

In a study conducted in Brazil, from 1981 to 2007, the cases of conjoined twins and their outcomes were investigated. The research found 14 cases of pregnant women with imperfect twins, and, in all cases, cesarean section was performed. Seven pairs were female and six male, and, in one pair of twins, the sex was not identified because they were ischiopagus. According to the site of fusion, seven pairs of twins were thoraco-omphalopagus and seven, omphalo-rachipagus. After birth, 10 pairs of twins died on the first day of life and three pairs survived for less than a year, and only one pair underwent surgical separation. The pair of xipho-omphalopagus, separated at 15 days of life, remained in excellent health conditions after 8 years of intervention( 36 ).

Mortality of conjoined twins remains high since the success of the surgery depends on the complexity of the fusion, extent of the junction of shared organs, severity of abnormalities, and the clinical conditions of the twins intra and postoperatively. Mortality rates are higher for separations performed in the first months of life( 10 , 32 ).

Cases of twins who do not share vital organs, e.g., heart or brain, as omphalopagus and pygopagus, have higher survival rates. For ischiopagus and parapagus twins, survival depends on the extent of the union, because pelvic, bone, and lower genitourinary tract reconstructions are necessary, being morbidity significant in the long run due to the need for additional reconstructive surgery. In craniopagus twins, the success of the surgery depends on the degree of sharing of the venous sinuses( 37 ).

Legal Aspects

The presence of conjoined twins always generates many ethical questions. The decision for surgical separation can put the twins in life danger, leading to a more conservative approach. The OBJECTIVE of the separation of conjoined twins is to make the fetuses free individuals, with the possibility of independent existence, with individual choices( 38 ). The presence of two separate brains is considered the basis for considering conjoined twins two individuals, because an independent brain is the essence of existence. However, each twin should be handled according to the bases of ethics, taking into account the principles of autonomy and obedience, non-maleficence, and justice. The well-being of each twin should be sought independently, without causing harm to any of them( 39 ). Any risk of morbidity and mortality to one of the twins must be communicated to parents and the decision is up to them to decide whether or not to perform the separation surgery.

According to the Brazilian Penal Code, the termination of a pregnancy is allowed only in two cases: risk of motherâ€(tm)s life or pregnancy arising from the crime of rape (article 128). The Brazilian Supreme Court also legalized termination of pregnancy in the case of anencephaly (law approved in April 2012). For conjoined twins without separation conditions - due to complexity of fusion, there is no law authorizing the termination of pregnancy. In these cases, it is necessary that the Judiciary authorizes the termination of pregnancy, taking into account the constitutional principle of human dignity, Article 1. Only after authorization, it is possible to perform the interruption( 40 ).

At Hospital de Clínicas de São Paulo, 30 cases from 1998 to 2010 were analyzed, which presented complex fusions, without conditions of postnatal separation, and which met the following criteria: absence of prognosis after postnatal surgical separation, lethality of fetal malformation (complex fusion of vital organs, such as heart and liver), complex cardiac malformation, gestational age lower than 25 weeks and no contraindication to vaginal delivery, since the goal would be the labor induction. In cases where parents chose to try to interrupt the pregnancy, reports of sonographic evaluation and echocardiographic reports that offered prognostic data to the fetuses, besides scientific basis showing that the condition was lethal. Among the 30 cases analyzed, in 25 the health team suggested the possibility of application for judicial authorization to interrupt the pregnancy. Among these, 19 (76%) parents chose to interrupt the pregnancy and six (24%), chose to maintain the pregnancy. In the other five cases, because the gestational age exceeded 25 weeks, the possibility of interruption was not discussed. Among the 19 cases in which the authorization for discontinuation was requested, in 12 (63.2%) the requests were accepted and abortion was authorized; in 5 (26.3%), the requests were rejected and, in two cases, data about the resolution of the cases were not obtained. Among the cases with authorization for interruption, 83.3% occurred via vaginal and, in the group that did not get authorization for interruption, cesarean section was performed in 100% of cases, and all newborn twins died after birth. The mean interval to obtain judicial authorization was of approximately 3 weeks in the 12 cases deferred( 41 ).

Conclusion

Although imperfect twinning is a rare condition, its prenatal diagnosis is very important to assess the fusion site and its complexity, for, then, defining the management and prognosis. Hence, the evaluation of fetuses with imperfect twinning should be multidisciplinary, involving mainly obstetricians, pediatricians, and pediatric surgeons, to decide the best time to interrupt pregnancy and define the chances of postnatal separation. However, such dilemmas may constitute true ethical dilemmas, in which different aspects should be discussed and analyzed, along with the health care team and the family.

Footnotes

Instituição: Hospital Materno Infantil Presidente Vargas; Tomoclínica e Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre (UFCSPA), Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil

References

- 1.McHugh K, Kiely EM, Spitz L. Imaging of conjoined twins. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:899–910. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kompanje EJ. The first successful separation of conjoined twins in 1689: some additions and corrections. Twin Res. 2004;7:537–541. doi: 10.1375/1369052042663760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Machin GA, Keith LG. An atlas of multiple pregnancy: biology and pathology. New York: CRC Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spitz L. Conjoined twins. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25:814–819. doi: 10.1002/pd.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen J, Elsner C, Kort H, Malter H, Massey J, Mayer MP, et al. Impairment of the hatching process following IVF in the human and improvement of implantation by assisting hatching using micromanipulation. Hum Reprod. 1990;5:7–13. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wenstrom KD, Syrop CH, Hammitt DG, Van Voorhis BJ. Increased risk of monochorionic twinning associated with assisted reproduction. Fertil Steril. 1993;60:510–514. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yovich JL, Stanger JD, Grauaug A, Barter RA, Lunay G, Dawkins RL, et al. Monozygotic twins from in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 1984;41:833–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seller MJ. Conjoined twins discordant for cleft lip and palate. Am J Med Genet. 1990;37:530–531. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320370420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones KL. Smith's recognizable patterns of human malformation. 6. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brizot ML, Liao AW, Lopes LM, Okumura M, Marques MS, Krebs V, et al. Conjoined twins pregnancies: experience with 36 cases from a single center. Prenat Diagn. 2011;31:1120–1125. doi: 10.1002/pd.2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barth RA, Filly RA, Goldberg JD, Moore P, Silverman NH. Conjoined twins: prenatal diagnosis and assessment of associated malformations. Radiology. 1990;177:201–207. doi: 10.1148/radiology.177.1.2204966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unal O, Arslan H, Adali E, Bora A, Yildizhan R, Avcu S. MRI of omphalopagus conjoined twins with a Dandy-Walker malformation: prenatal true FISP and HASTE sequences. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2010;16:66–69. doi: 10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.1747-08.0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mummigatti K, Shamshal A. Antenatal diagnosis of conjoined twins - parapagus dicephalus: a case report. NJOG. 2011;6:61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spencer R. Theoretical and analytical embryology of conjoined twins: part I: embryogenesis. Clin Anat. 2000;13:36–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(2000)13:1<36::AID-CA5>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill LM. The sonographic detection of early first-trimester conjoined twins. Prenat Diagn. 1997;17:961–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt W, Heberling D, Kubli F. Antepartum ultrasonographic diagnosis of conjoined twins in early pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;139:961–963. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90969-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pajkrt E, Jauniaux E. First-trimester diagnosis of conjoined twins. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25:820–826. doi: 10.1002/pd.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poenaru D, Uroz-Tristan J, Leclerc S, Murphy S, St-Vil D, Youssef S, et al. Minimally conjoined omphalopagi: a consistent spectrum of anomalies. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:1236–1238. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90811-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiss JL, Devine PC. False positive diagnosis of conjoined twins in the first trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002;20:5168–5168. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2002.00849_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuillier F, Dillon KC, Grochal F, Scemama JM, Gervais T, Cerekja A, et al. Conjoined twins: what ultrasound may add to management. J Prenat Med. 2012;6:4–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feitosa e Castro RM, Cunha SP, Feitosa e Castro PS, Pina JM, Neto, Ramos ES, Bailão LA. Diagnóstico pré-natal de gêmeos unidos. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 1994;16:141–143. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackenzie TC, Crombleholme TM, Johnson MP, Schnaufer L, Flake AW, Hedrick HL, et al. The natural history of prenatally diagnosed conjoined twins. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:303–309. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.30830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen PL, Choe KA. Prenatal MRI of heteropagus twins. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1676–1678. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.6.1811676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martínez L, Fernández J, Pastor I, García-Guereta L, Lassaletta L, Tovar JA. The contribution of modern imaging to planning separation strategies in conjoined twins. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003;13:120–124. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huisman TA, Arulrajah S, Meuli M, Brehmer U, Beinder E. Fetal MRI of conjoined twins who switched their relative positions. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:353–357. doi: 10.1007/s00247-009-1445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benirschke K, Kim CK. Multiple pregnancy. 1. N Engl J Med. 1973;288:1276–1284. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197306142882406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newton ER. Antepartum care in multiple gestation. Semin Perinatol. 1986;10:19–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sibai BM, Hauth J, Caritis S, Lindheimer MD, MacPherson C, Klebanoff M, et al. Hypertensive disorders in twin versus singleton gestations. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:938–942. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-ObstetricsSociety for Maternal-Fetal MedicineACOG Joint Editorial Committee ACOG Practice Bulletin #56: Multiple gestation: complicated twin, triplet, and high-order multifetal pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:869–883. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200410000-00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrews RE, McMahon CJ, Yates RW, Cullen S, de Leval MR, Kiely EM, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of conjoined twins. Heart. 2006;92:382–387. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.069682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norwitz ER, Hoyte LP, Jenkins KJ, van der Velde ME, Ratiu P, Rodriguez-Thompson D, et al. Separation of conjoined twins with the twin reversed-arterial-perfusion sequence after prenatal planning with three-dimensional modeling. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:399–402. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008103430604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spitz L, Kiely EM. Conjoined twins. JAMA. 2003;289:1307–1310. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spitz L. Conjoined twins. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1028–1030. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asaranti K, Pranati M, Tushar K, Jagadish B, Susmita B, Amarendra N. Autopsy findings in conjoined twin with single heart and single liver. Case Rep Pathol. 2012;2012:129323–129323. doi: 10.1155/2012/129323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seo JW, Shin SS, Chi JG. Cardiovascular system in conjoined twins: an analysis of 14 Korean cases. Teratology. 1985;32:151–161. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420320202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berezowski AT, Duarte G, Rodrigues R, Cavalli RC, Santos RO, Villela YA, et al. Conjoined twins: an experience of a tertiary hospital in Southeast Brazil. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2010;32:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanders RC, Blackman LR, Hogge WA, Wulfsberg EA, Spevak PJ. Structural fetal abnormalities: the total picture. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pellegrino ED. The relationship of autonomy and integrity in medical ethics. In: Connor SS, Fuenzalida-Puelma HL, editors. Bioethics: issues and perspectives. Washington: PAHO; 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearn J. Bioethical issues in caring for conjoined twins and their parents. Lancet. 2001;357:1968–1971. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brasil - Presidência da República [cited 2013 Jun 12];[homepage on the Internet]. Decreto-lei nº 2.848, de 7 de dezembro de 1940. Available from: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto-lei/del2848compilado.htm.

- 41.Nomura RM, Brizot Mde L, Liao AW, Hernandez WR, Zugaib M. Conjoined twins and legal authorization for abortion. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2011;57:205–210. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302011000200020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]