Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To analyze the reasons for non-adherence to follow-up at a specialized outpatient clinic for obese children and adolescents.

METHODS

Descriptive study of 41 patients, including information from medical records and phone recorded questionnaires which included two open questions and eight closed ones: reason for abandonment, financial and structural difficulties (distance and transport costs), relationship with professionals, obesity evolution, treatment continuity, knowledge of difficulties and obesity complications.

RESULTS

Among the interviewees, 29.3% reported that adherence to the program spent too much time and it was difficult to adjust consultations to patientsâ€(tm) and parentsâ€(tm) schedules. Other reasons were: childrenâ€(tm)s refusal to follow treatment (29.3%), dissatisfaction with the result (17.0%), treatment in another health service (12.2%), difficulty in schedule return (7.3%) and delay in attendance (4.9%). All denied any relationship problems with professionals. Among the respondents, 85.4% said they are still overweight. They reported hurdles to appropriate nutrition and physical activity (financial difficulty, lack of parentsâ€(tm) time, physical limitation and insecure neighborhood). Among the 33 respondents that reported difficulties with obesity, 78.8% had emotional disorders such as bullying, anxiety and irritability; 24.2% presented fatigue, 15.1% had difficulty in dressing up and 15.1% referred pain. The knowledge of the following complications prevailed: cardicac (97.6%), aesthetic (90.2%), psychological (90.2%), presence of obesity in adulthood (90.2%), diabetes (85.4%) and cancer (31.4%).

CONCLUSIONS

According to the results, it is possible to create weight control public programs that are easier to access, encouraging appropriate nutrition and physical activities in order to achieve obesity prevention.

Keywords: patient dropouts, obesity, child, adolescent

Abstract

OBJETIVO

Analizar los motivos de abandono del seguimiento, en ambulatorio especializado, por niños y adolescentes obesos.

MÉTODOS

Estudio descriptivo, con 41 pacientes, incluyendo informaciones de prontuarios y de cuestionario realizado y grabado por teléfono, con dos cuestiones abiertas y ocho cerradas: motivo del abandono, dificultades estructurales y financieras (distancia y costo de transporte), relación con profesionales, evolución de la obesidad, continuidad del tratamiento, conocimiento de las dificultades y complicaciones de la obesidad.

RESULTADOS

En las entrevistas, el 29,3% relataron tiempo elevado empleado y dificultad en adaptar los horarios de las consultas a las actividades de los pacientes y padres. Otros motivos fueron: recusa de los niños en realizar el tratamiento (29,3%), insatisfacción con el resultado (17%), seguimiento en otro servicio (12,2%), dificultad en marcar el retorno (7,3%) y demora en la atención (4,9%). Todos negaron problemas de relación individual o en grupo con profesionales. De los entrevistados, el 85,4% afirmaron que continúan con más peso que lo recomendado. Se relataron barreras para alimentación y realización de ejercicios físicos adecuados (dificultad financiera, falta de tiempo de los padres, limitación física y falta de seguridad). De los 33 entrevistados que relataron dificultades con la obesidad, el 78,8% tenían trastornos emocionales como bullying, ansiedad e irritabilidad; el 24,2% presentaron cansancio; el 15,1%, dificultades en el momento de vestirse y el 15,1%, dolor. Fue más frecuente el conocimiento de las complicaciones a continuación: cardíacas (97,6%), estéticas (90,2%), psicológicas (90,2%), permanencia de la obesidad en el adulto (90,2%), diabetes (85,4%) y cáncer (31,4%).

CONCLUSIONES

A partir de los resultados, se pueden elaborar programas públicos de control de peso que sean de más fácil acceso respecto a la localidad de la atención y con incentivo a la alimentación y actividades físicas adecuadas a la prevención de la obesidad.

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents in developed and developing countries, including Brazil, has increased significantly over the past three decades, and is now considered a chronic public health problem( 1 - 3 ).

In children and adolescents, it is important to note that obesity can impact quality of life and lead to psychosocial disorders, such as bullying, low self-esteem, lack of confidence, and worsening in body image, factors that favor greater difficulties for losing weight( 4 - 6 ). Obesity also affects life expectancy because it is related to obesity in adult life, to metabolic and cardiovascular complications, besides orthopedic disorders, sleep apnea, and higher risk of cancer, which are increasingly diagnosed in childhood and adolescence( 2 , 7 , 8 ). Such concerns increase, as the leading cause of death in adults is cardiovascular disease, directly related to overweight( 9 ).

To avoid increasing the pandemic of obesity, prevention programs, although scarce, both in healthy and in overweight children, have been recommended, with promising results. It is believed that if these programs were longer lasting, better results would be obtained( 10 ). The treatment recommended is building healthy habits, that are very dependent on family involvement, including psychosocial comprehension, eating habits, physical activity, sleep schedule and cultural considerations( 11 , 12 ). However, because obesity is an apparently asymptomatic chronic disease, difficult to accept both by the patient and the parents/guardians, it results in poor response to long-term treatment and loss to follow-up.

In this context, the present study identified reasons for the abandonment of treatment by children and adolescents followed at an outpatient obesity unit.

Method

This is a prospective, descriptive study of patients of both sexes, who abandoned follow-up at the Obese Children and Adolescents outpatient clinic at Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp), from 2005 to 2009. Based on a previous study, which followed 150 patients and observed 43% of abandonment, 25% already in the first consultation( 13 ), selected 96 patients and performed 41 interviews with parents, recorded by telephone, from March to June 2011. Other patients were not contacted due to unknown address or telephone number. The study considered the individuals who abandoned treatment, who did not receive discharge from outpatient care, and who did not attend the outpatient clinic for longer than 6 months after the last visit. This information was obtained from medical records, as well as clinical data.

At the outset of the phone call, the characteristics and OBJECTIVEs of the study were presented, and recorded verbal consent was obtained. After consent, the questionnaire was used. Patients whose parents or guardians presented deafness, mental or phonoaudiological problems that would prevent them from responding to the questionnaires were excluded.

The interview consisted of two open and eight closed questions, and many were correlated. The questions addressed different dimensions: assessment of the parent with regard to what led the son to abandon the treatment, financial and structural difficulties (distance and transportation costs), relationship with professionals working at the outpatient clinic, participation in group care, dietary and physical activity guidelines, advances regarding obesity, continuity of treatment, related disorders, and knowledge about the complications of the disease.

All data were computed on a medical record and analyzed by the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) program, version 13.0. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Unicamp, under opinion n. 555/2010.

Results

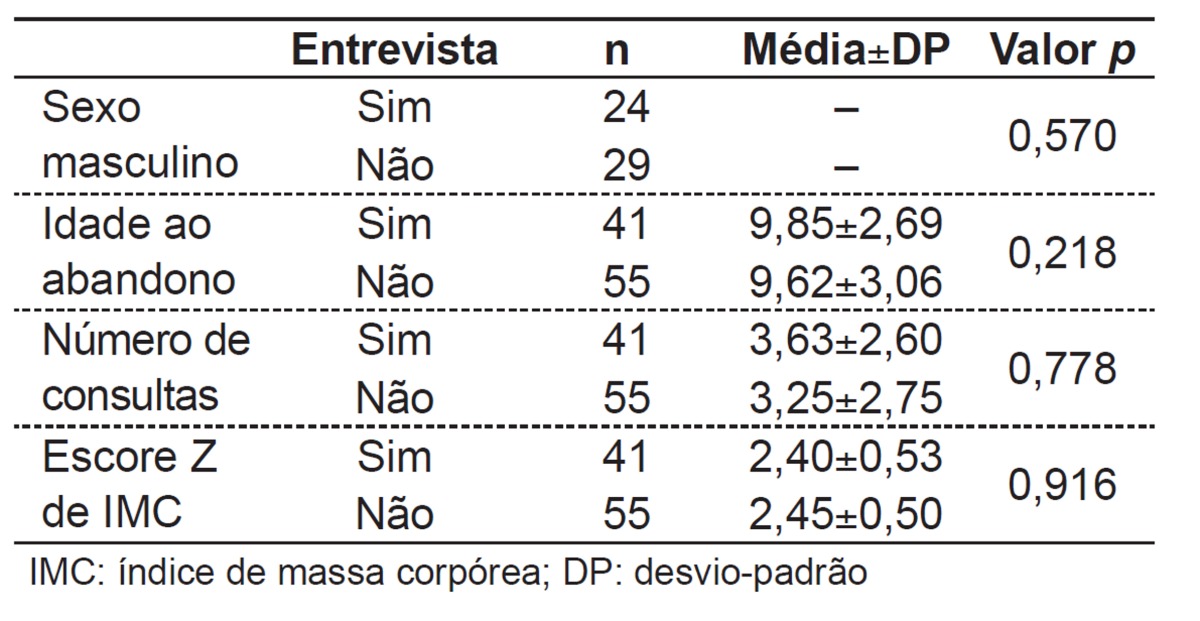

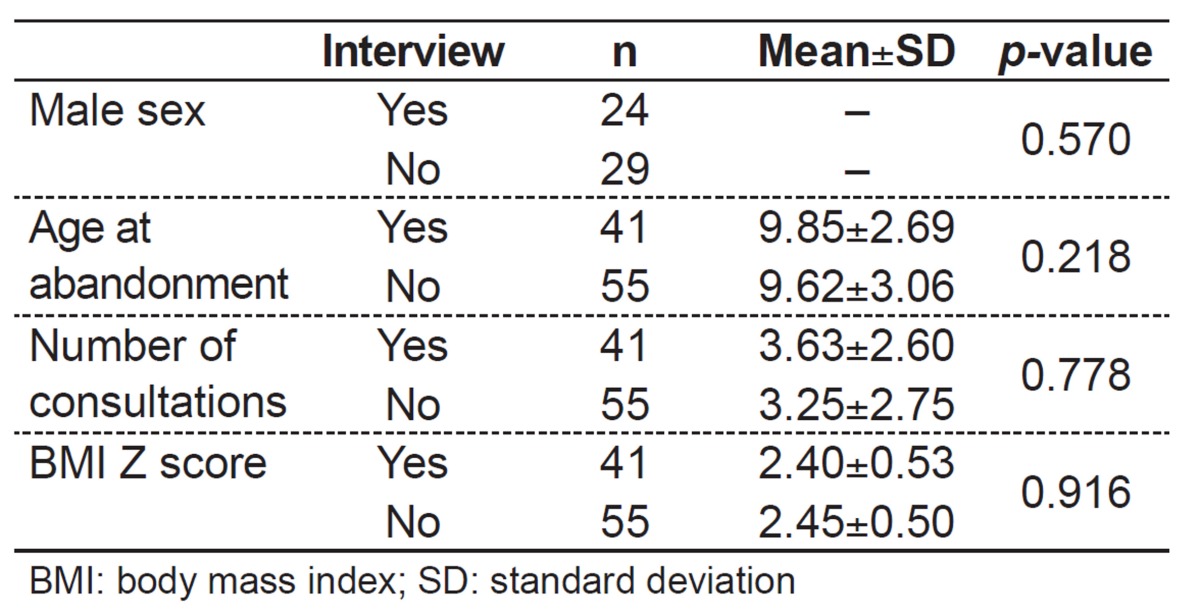

Among selected patients and interviewed patients, there was no statistically significant difference regarding sex, age at abandonment, number of consultations performed, and z score for body mass index (BMI) (Table 1). Parents were questioned, and 32 (78.1%) interviews were performed with mothers, six (14.6%) with the father, two (4.9%) with the grandmother and one (2.4%) with both parents. On average, there were 3.6 years after abandonment of treatment and the mean age of the patients was 14.0 years.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 96 patients who abandoned treatment according to whether they were interviewed or not.

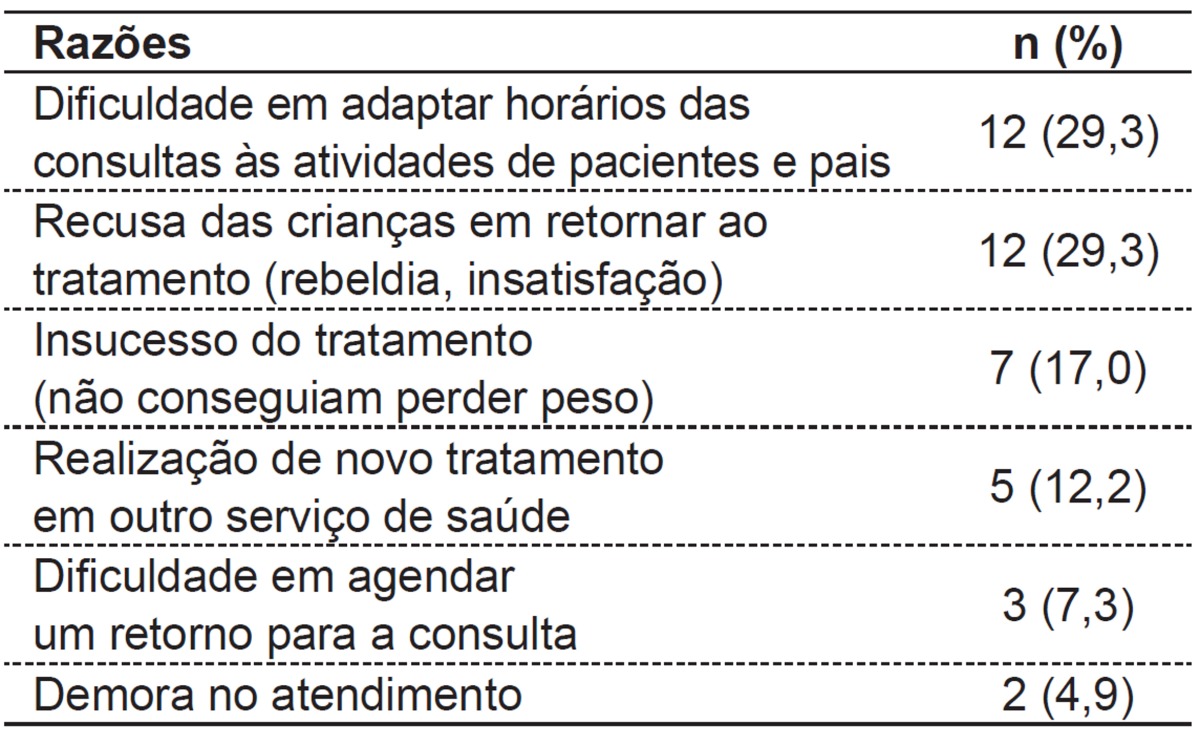

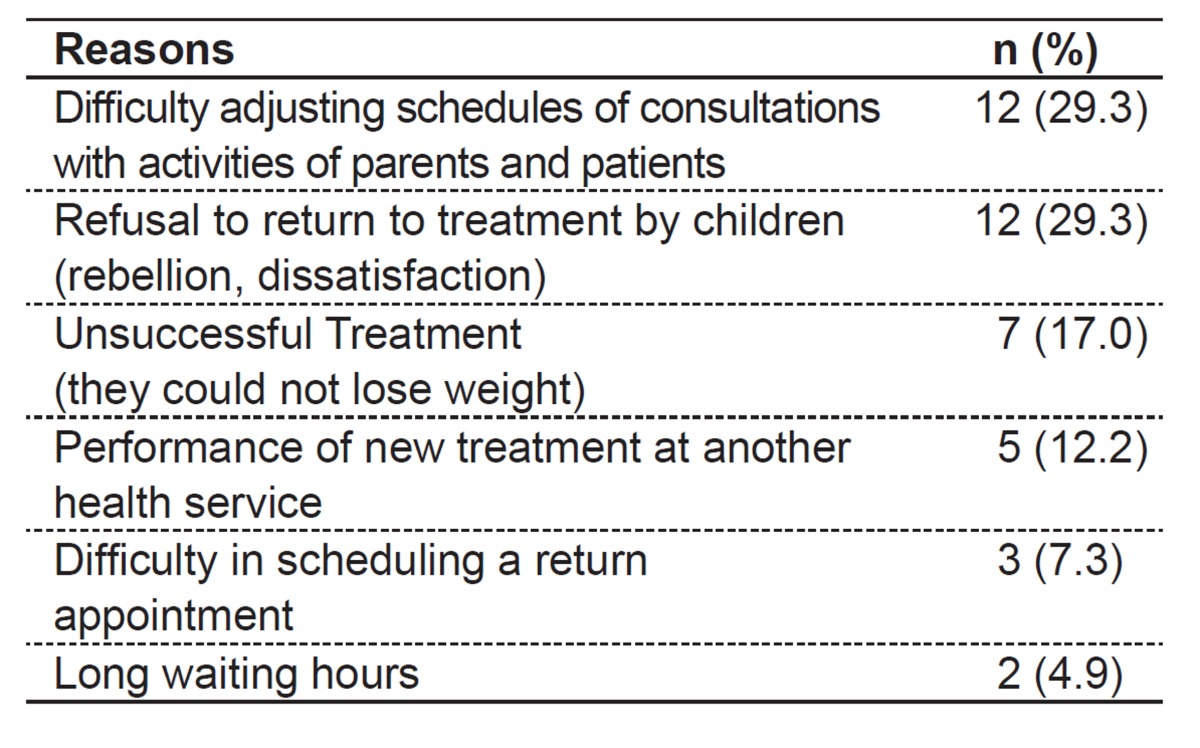

The reasons for abandonment - including difficulty adjusting scheduled appointments of parents and patients (29.3%) and refusal of children to returning to treatment, such as rebellion, dissatisfaction, etc. (29.3%) - are described in Table 2.

Table 2. Reports of the 41 parents about reasons for treatment abandonment.

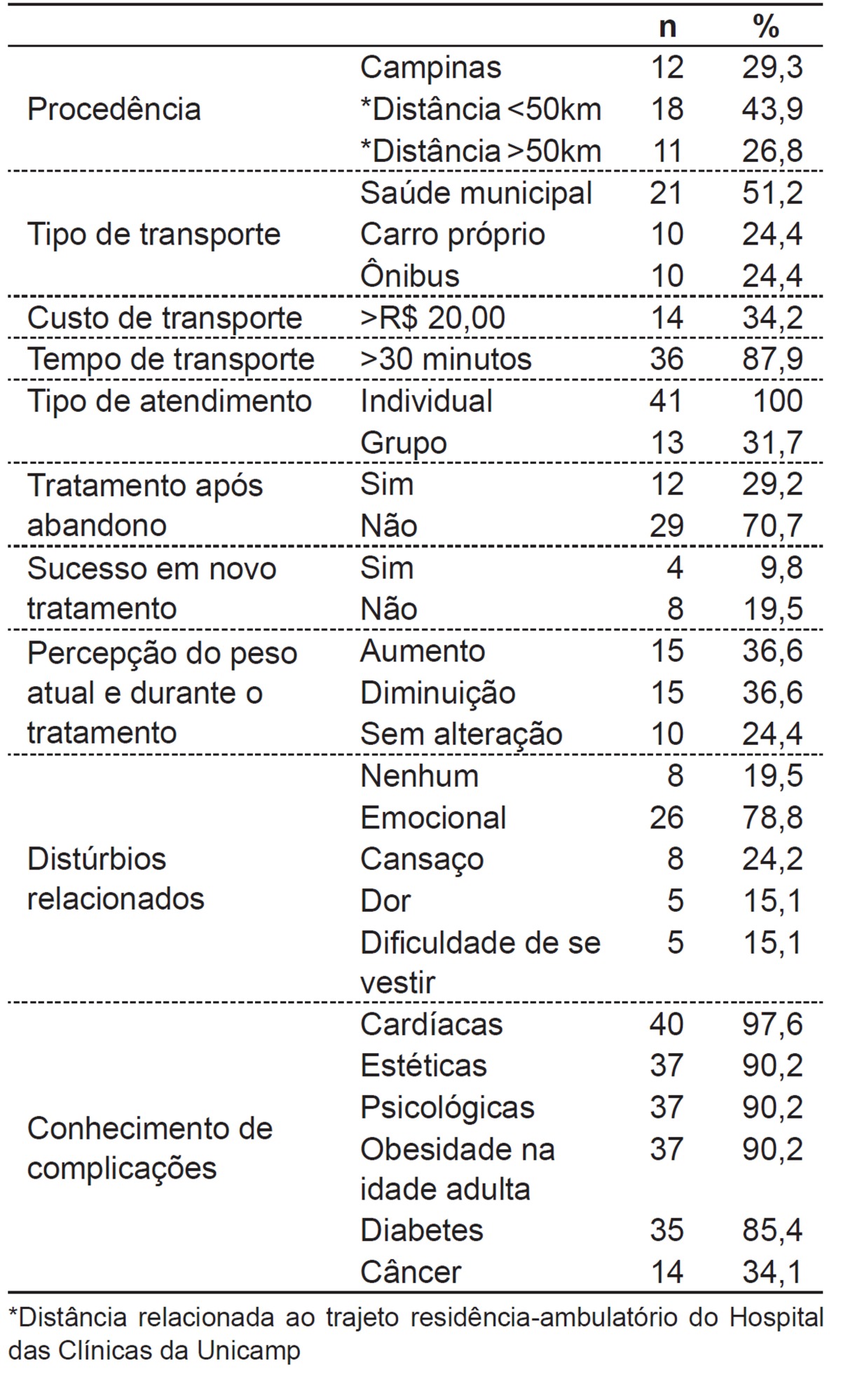

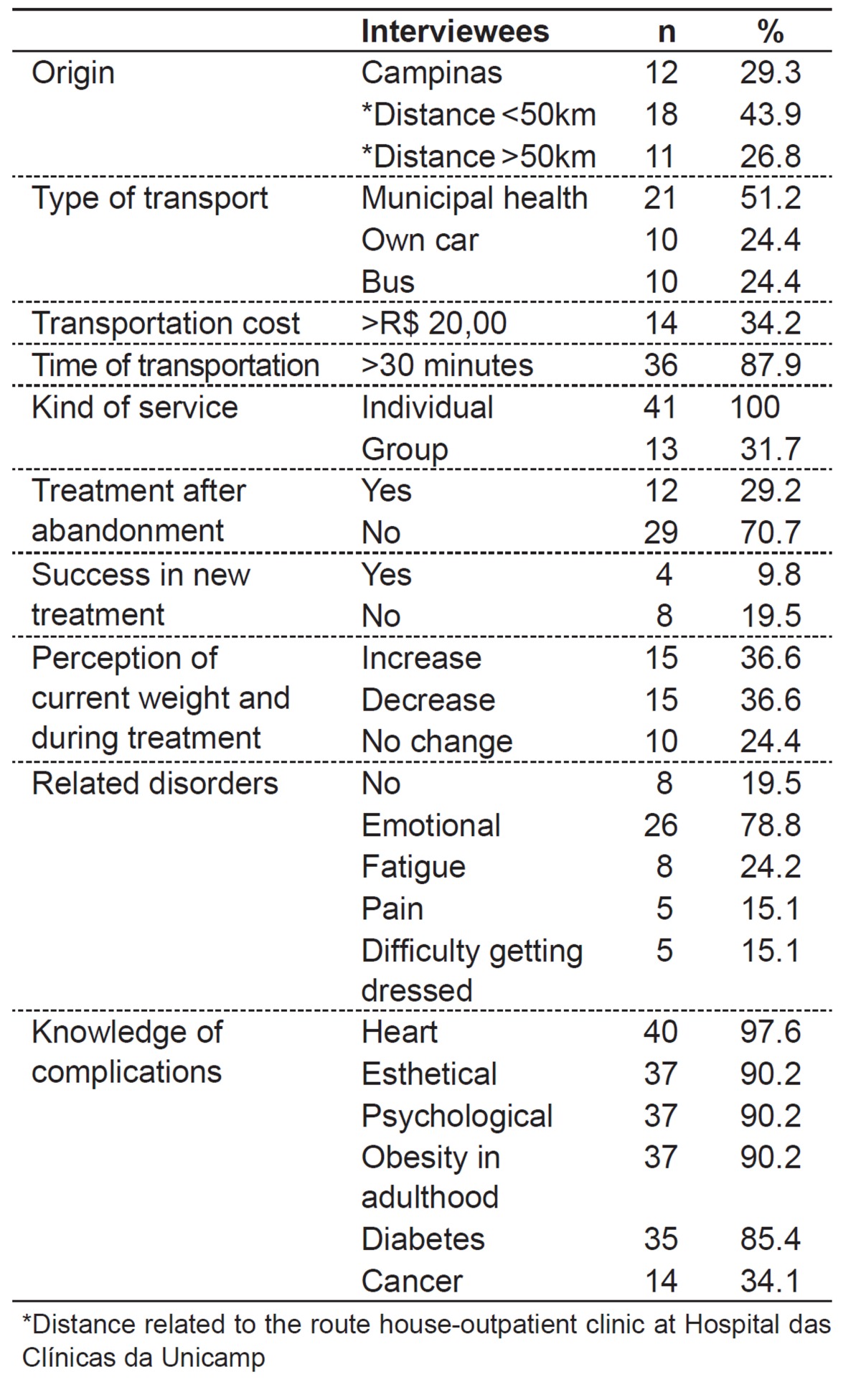

The assessment of the structural and financial difficulties (distance and cost of transportation), the type of care, the evolution regarding the treatment and obesity, the related disorders and knowledge of complications of the disease are described in Table 3.

Table 3. Exploratory questions to determine possible reasons for non-compliance to treatment, answered by the 41 parents in telephone interviews.

None of the respondents reported relationship problems with the staff at the outpatient clinic. Among the respondents, 34.1% said they participated in group care, and, of these, 35.7% considered it excellent, 42.9%, good, and 21.3%, bad.

Regarding dietary guidelines, 80.5% reported having received guidance from a nutritionist. Among these, 12.2% presented difficulty in understanding it; however, most of them reported that the main difficulty was to follow it. Among the difficulties, parents mentioned that they could not deny food to their children and that they had no control over what the kids ate, since they worked during the day and had financial difficulties to purchase appropriate foods to follow the diet. Most parents of children who followed the diet mentioned that, after the interruption, there was weight gain.

Regarding physical activities, 61% of respondents received specific guidance from a physical educator. Among these, 55.9% reported some kind of difficulty for implementation of activities; and among the most cited reasons are: financial difficulty to perform the recommended activity, such as swimming and gym; time limitation of children and parents, associated to the lack of public safety and the patientsâ€(tm) own physical limitations due to obesity. In the period of follow-up, 17.9% did not practice any kind of physical exercise, 5.1% practiced only once a week, 23.1%, twice a week, 28.2%, three, 5.1%, four, 7.7%, five and 12.8%, seven times a weeks. On the date of the interview, 24.4% said they did not practice any kind of physical exercise, 7.3% practiced physical education only once a week, 19.5%, twice a week, 7.3%, three times a week, 12.2%, four, 17.1%, five and 12.2%, seven times a week.

It was also observed that 85.4% of individuals were still overweight, and 36.6% had gained weight since treatment abandonment, 36.6% lost weight, and, 24.4%, had no change.

Among the respondents, 29.2% started treatment elsewhere. Among these, 49.8% started treatment at Health Centers, 24.9%, in private practices and 16.7%, in another hospital. Among patients who initiated new monitoring, 66.5% said they were not successful.

Regarding the difficulties that obesity causes to their children, eight (19.5%) parents denied this problem. Among the other 33 patients, 26 (78.8%) reported emotional disorders such as bullying, anxiety, and irritability; eight (24.2%), tiredness; five (15.1%), difficulties in getting dressed, and five (15.1%) reported pain, especially osteoarticular.

Regarding the risk of morbidities related to obesity, 97.6% of respondents knew the association of the disease with heart problems, 90.2%, with psychological difficulties, 90.2%, with esthetic changes, 90.2%, with permanence of obesity in adult life, 85.4%, with diabetes, and 31.4%, with cancer.

Discussion

The Clinic of Obesity in Children and Adolescents at Hospital das Clínicas da Unicamp aims to act through interventions that raise awareness of patients and their families on the risks of the disease and its consequences, besides offering treatment for complications arising from obesity, nutritional guidelines, and encouraging increased physical activity( 12 , 13 ). For this approach, the clinic has a multidisciplinary team of professors and first-year residents in Pediatrics, as well as nutritionist, physical educator, psychologist, and physiotherapist, according to what the literature recommends( 14 , 15 ). The patients are monitored once a week, and seven to ten patients are assisted per day. However, a previous study with patients in the same clinic found abandonment of follow-up in 43%, with no statistically significant differences between age, sex, age of onset, z score for weight, height, and BMI, or laboratory findings that justify this attitude( 13 ).

In interviews with the patients, it was verified that the reasons for abandonment are related mainly to the difficulty in adapting the schedules of consultations to the activities of patients and parents, the refusal to perform treatment by the children, dissatisfaction with the results, and, in a smaller number, to the change of monitoring site, difficulty in scheduling return appointments, and long waiting time for consultations. These data are similar to other findings that obtained as causes of abandonment the focus of treatment, distance, and scheduling conflicts( 16 , 17 ). A Canadian study reported physical barriers, of clinical organization and the educational program as factors related to the interruption of follow-up( 18 ).

In this study, among the structural difficulties, stand out: distance, time spent, and cost. Most interviewees were not from the municipality of Campinas, with approximately 40% living in distant cities located more than 50km from the municipality. The distance between the house and the site of care was also mentioned as a barrier in other studies( 19 , 20 ). In this research, the transportation time between home and the site of care, in most patients, was longer than 1 hour. Furthermore, as approximately 50% used municipal health transport, this meant spending the whole day at the hospital. This delay creates difficulty adjusting the schedules of consultations with activities of patients and parents, as observed in other studies( 21 ). For those who spend all day at the hospital, there is an increase in the cost of food. A similar study showed that 25% of patients abandoned treatment of obesity due to the time and difficulty adjusting the times of consultation and activities of patients and parents, 27.9% due to missing school, 23.3% because of the distance, and 10.3% because of the costs( 16 ).

Approximately 30% of respondents participated in the group care. This form of assessment has lower dropout rates, according to data from Minniti et al( 22 ). Interestingly, none of the respondents mentioned relationship problems with the clinic staff, unlike a study, which noted dissatisfaction with the team and with the focus of treatment( 16 ).

In nutritional counseling, few patients reported difficulties in understanding it, but most have trouble doing it. It was found that parents have problems for controlling the childâ€(tm)s diet, either due to financial difficulties for the purchase of recommended foods, or because most parents work and can not control the childâ€(tm)s diet, besides the difficulty in denying food to the child. These factors have also been reported by other authors( 23 ).

Regarding physical activity, it is clear that, after the abandonment of treatment, there was an increase in the number of patients who did not practice any kind of physical exercise. In addition, most reported some difficulty in doing it. Among the obstacles, financial hardship to provide appropriate treatment, little time availability of parents to supervise their children, and unsafe neighborhoods, as mentioned in other investigations( 24 - 26 ).

Interestingly, 29.3% sought a new place for treatment after the abandonment, but only 12.2% mentioned this justification. Furthermore, most patients who looked for a new service declared unsuccessful treatment as a justification, which may lead to the hypothesis that the abandonment occurs due to multiple social causes that discourage follow-up( 16 - 18 , 26 ).

Besides structural factors, in this study there were cases of abandonment due to rebellion and dissatisfaction, besides lack of success in the treatment. As the result is not immediate, on the contrary, weight loss occurs in the long term, this may discourage the patient( 23 , 27 ). The dissatisfaction of the child may influence the parents and guardians who often feel frustrated, ashamed, and guilty, because they do not know how to help their children lose weight( 5 ). Regardless of the response to treatment, 85.4% of the parents consider that their children are overweight and, even if there was some weight loss during the treatment, they start gaining weight again after the abandonment. According to the literature, only 5% of adolescents who lose weight manage to keep it after 5 years of treatment( 27 ), justifying one of the difficulties of monitoring.

As in other studies, it was observed that most parents recognize the difficulties that obesity causes, emphasizing the emotional aspect, reporting relationship problems with friends and family, as well as in daily activities (fatigue and pain), pejorative nicknames that affect self-esteem, bullying, irritability, and difficulty in getting dressed( 5 , 6 , 23 , 28 ). These problems may lead to marginalization of the child and adolescent, taking them away from recommended physical activities and increasing their time in front of the television, videogame, and computer. The psychological complications, though frequent, are difficult to characterize and it is argued whether they are causes or consequences of obesity( 5 ). In general, patients with psychological disorders seek care more often, but are also those with higher rates of failure in weight loss and treatment abandonment( 5 , 6 ). Therefore, psychological counseling is recommended, because it is a factor that influences response to the treatment of obesity( 5 , 6 ).

Parents also have information regarding clinical complications: cardiac risks, metabolic risks, and even higher risk of cancer. It is interesting to note that his knowledge did not generate stimulus for continuing the treatment. Therefore, the structural and psychological difficulties seem more influential on treatment adherence or abandonment( 23 ).

The present study, even with the small number of patients assessed, due to the difficulty of contact (approximately half of those selected) and the large interval of time for the interview, pointed out the main reasons for abandonment. Therefore, further and larger studies should be conducted. Despite this limitation, it was observed that the parents are aware that obesity is a disease, with its comorbidities, but there are physical and economic barriers that hinder changes in lifestyle, as observed in another study( 29 ). Psychological changes are relevant and recognized, which can be associated to the abandonment by dissatisfaction and rebellion and to the search for "magic solutions."

The decrease in the prevalence of obesity has achieved little success in developing and developed countries, despite the large increase in specific programs and studies for this purpose. With data from this survey, it can be suggested that the locations for weight control programs be easier to access, and dietary guidelines and physical activities be adaptable to family socioeconomic conditions( 11 , 30 ), along with the assessment of emotional aspects. Due to non-compliance with the proposed guidelines, associated with follow-up abandonment, the development of programs that act in the prevention of obesity should be done as early as possible( 10 ).

Funding Statement

Fonte financiadora: Fundo de Apoio ao Ensino, à Pesquisa e à Extensão (Faepex), nº 98.610 e Programa Institucional de Bolsas de Iniciação Científica (PIBIC)/CNPq

Footnotes

Instituição: Ambulatório de Obesidade na Criança e no Adolescente do Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp) e Departamento de Pediatria da Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Unicamp, Campinas, SP, Brasil

References

- 1.Wang Y, Monteiro CA, Popkin BM. Trends of obesity and underweight in older children and adolescents in the United States, Brazil, China, and Russia. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:971–977. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.6.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . WHO forum and technical meeting on population-based prevention strategies for childhood obesity. Geneva: WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brasil. Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Diretoria de pesquisas. Coordenação de trabalho e rendimento. Pesquisa de orçamentos familiares 2008-2009: antropometria e estado nutricional de crianças, adolescentes e adultos no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daniels SR. The consequences of childhood overweight and obesity. Future Child. 2006;16:47–67. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warder Wal JS, Mitchell ER. Psychological complications of pediatric obesity. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58:1393–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porter JS, Bean MK, Gerke CK, Stern M. Psychosocial factors and perspectives on weight gain and barriers to weight loss among adolescents enrolled in obesity treatment. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17:98–102. doi: 10.1007/s10880-010-9186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels SR. Complications of obesity in children and adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33(Suppl 1):S60–S65. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferreira JS, Aydos RD. Prevalence of hypertension among obese children and adolescents. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2010;15:97–104. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232010000100015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia VI Diretrizes Brasileiras de Hipertensão. Rev Bras Hipertens. 2010;17:1–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitka M. Programs to reduce childhood obesity seem to work, say Cochrane reviewers. JAMA. 2012;307:444–445. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenders CM, Gorman K, Lim-Miller A, Puklin S, Pratt J. Practical approaches to the treatment of severe pediatric obesity. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58:1425–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ, Brown T, Campbell KJ, Gao Y, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011: doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zambon MP, Antônio MA, Mendes RT, Barros AA., Filho Obese children and adolescents: two years of interdisciplinary follow-up. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2008;26:130–135. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria [homepage on the Internet] Obesidade na infância e adolescência: manual de Orientação. Departamento de Nutrologia. Rio de Janeiro: SBP; 2012. [2013 Jun 4]. Available from: http://www.sbp.com.br/PDFs/Man%20Nutrologia_Obsidade.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barlow SE, Expert Committee Expert Committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120:S164–S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barlow SE, Ohlemeyer CL. Parent reasons for nonreturn to a pediatric weight management program. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2006;45:355–360. doi: 10.1177/000992280604500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moroshko I, Brennan L, O'rien P. Predictors of dropout in weight loss interventions: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2011;12:912–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitscha CE, Brunet K, Farmer A, Mager DR. Reasons for non-return to a pediatric weight management program. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2009;70:89–94. doi: 10.3148/70.2.2009.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lara MD, Baker MT, Larson CJ, Mathiason MA, Lambert PJ, Kothari SN. Travel distance, age, and sex as factors in follow-up visit compliance in the post-gastric by pass population. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2004;1:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sivagnanam P, Rhodes M. The importance of follow-up and distance from centre in weight loss after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2432–2438. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0970-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart L, Chapple J, Hughes AR, Poustie V, Reilly JJ. Parents'journey through treatment for their child's obesity: a qualitative study. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:35–39. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.125146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minniti A, Bissoli L, Di Francesco V, Fantin F, Mandragona R, Olivieri M, et al. Individual versus group therapy for obesity: comparison of dropout rate and treatment outcome. Eat Weight Disord. 2007;12:161–167. doi: 10.1007/BF03327593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venturini LP. Obesidade e família - Uma caracterização de famílias de crianças obesas e a percepção dos familiares e das crianças de sua imagem corporal. Ribeirão Preto, SP: USP; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keeton VF, Kennedy C. Update on physical activity including special needs populations. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:262–268. doi: 10.1097/mop.0b013e3283292614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palma A. Atividade física, processo saúde-doença e condições sócio-econômicas: uma revisão da literatura. Rev Paul Educ Fis. 2000;14:97–106. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skelton JA, Beech BM. Attrition in paediatric weight management: a review of the literature and new directions. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e273–e281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muller RC. Obesidade na adolescência. Pediatr Mod. 2001;37:45–48. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee YS. Consequences of childhood obesity. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2009;38:75–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skelton JA, Beech BM. Attrition in paediatric weight management: a review of the literature and new directions. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e273–e281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skelton JA, DeMattia LG, Flores G. A pediatric weight management program for high-risk populations: a preliminary analysis. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1698–1701. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]