Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate, by a literature review, the Timed "Up & Go" (TUG) test use and its main methodological aspects in children and adolescents.

DATA SOURCES

The searches were performed in the following databases: PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, SciELO and Cochrane Library, from April to July 2012. Studies published from 1990 to 2012 using the terms in Portuguese and English "Timed "Up & Go", "test", "balance", "child", and "adolescent" were selected. The results were divided into categories: general characteristics of the studies, population, test implementation METHODS, interpretation of results and associations with other measurements.

DATA SYNTHESIS

27 studies were analyzed in this review and most of them used the TUG test along with other outcome measures to assess functional mobility or balance. Three studies evaluated the TUG test in significant samples of children and adolescents with typical development, and the most studied specific diagnoses were cerebral palsy and traumatic brain injury. The absence of methodological standardization was noted, but one study proposed adaptations to the pediatric population. In children and adolescents with specific clinical diagnoses, the coefficient of within-session reliability was found to be high in most studies, as well as the intra and inter-examiner reliability, which characterizes the good reproducibility of the test.

CONCLUSIONS

The TUG test was shown to be a good tool to assess functional mobility in the pediatric population, presenting a good reproducibility and correlation with other assessment tools.

Keywords: mobility limitation, postural balance, child, adolescent

Abstract

OBJETIVO

Evaluar, mediante una revisión de la literatura, la utilización de la prueba Timed "Up & Go" y sus principales aspectos metodológicos en niños y adolescentes.

FUENTES DE DATOS

Se realizaron búsquedas en las siguientes bases de datos: PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, SciELO y Cochrane Library, entre abril y julio de 2012. Se seleccionaron los estudios publicados de 1990 a 2012, utilizándose los términos "timed up and go", "prueba" ("test"), "equilibrio" ("balance"), "niño" ("child") y "adolescente" ("adolescent"). Se dividieron los resultados en categorías: características generales de los estudios, poblaciones evaluadas, metodología de aplicación de la prueba, interpretación de los resultados y asociaciones de la prueba con otras medidas.

SÍNTESIS DE LOS DATOS

Se incluyeron 27 estudios y la mayoría utilizó el TUG juntamente con otras medidas de desfecho para evaluar movilidad o equilibrio funcional. Tres trabajos evaluaron el TUG en muestras expresivas de niños y adolescentes con desarrollo típico y los diagnósticos específicos más evaluados fueron parálisis cerebral y traumatismo craneoencefálico. No existe una estandarización respecto a la metodología utilizada, pero un estudio propuso adaptaciones para la población pediátrica. En niños y adolescentes con diagnósticos clínicos específicos, el coeficiente de confiabilidad intrasesión se mostró alto en la mayoría de los estudios, así como la confiabilidad intra e inter-examinador, caracterizando buena reproductibilidad de la prueba.

CONCLUSIONES

El TUG se mostró una buena herramienta para evaluar la movilidad funcional en Pediatría, correlacionándose con otros instrumentos de evaluación y presentando buena reproductibilidad.

Introduction

The Timed "Up & Go" (TUG) test was developed by Podsiadlo and Richardson in 1991( 1 ), based on the version named Get-up and Go test, proposed by Mathias et al in 1986(2). The "Get-up and Go" test originally aimed to clinically evaluate dynamic balance in elderly people during the performance of a task, involving critical situations for falls. Podsiadlo and Richardson proposed using time in seconds to score the test, naming it Timed "Up & Go", because there was a time limitation on the score of the original scale( 1 ).

The TUG test measures, in seconds, the time required for an individual to stand up from a standard chair with armrest (height of approximately 46cm), walk 3m, turn around, walk back to the chair, and sit down again( 1 ). The test has been widely used in clinical practice as an outcome measure to evaluate functional mobility, fall risk or dynamic balance in adults, and its normative values have already been established in this population( 3 , 4 ). Several studies used the test to assess fall risk in the elderly( 5 - 8 ); other studies assessed balance and functional mobility in adults with motor limitations, such as cerebral palsy (CP)( 9 ), Parkinson disease( 1 , 10 ), stroke( 1 , 11 - 13 ), Down syndrome (DS)( 14 ), among others.

Because of its practicality, the TUG test began to be used in children and adolescents with some type of motor limitation and/or balance deficit( 15 - 17 ). In order for ambulatory children or adolescents to have functional independence, balance is required during movements performed in sitting and bipedal postures. The activities that constitute the test assess the functional mobility and the balance required to move from the sitting to the standing position, walk, turn around, and sit down again.

Thus, considering the practicality of the TUG test to assess functional mobility, its increasing use in Pediatrics, and the lack of theoretical studies critically reviewing the use of the test, this study evaluated, through a literature review, the use of the TUG test and its methodological aspects in children and adolescents.

Method

This study consisted of a bibliographical review. References for electronic research were selected in July 2012, in PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, SciELO and Cochrane Library databases. Searches used the following terms in Portuguese and English: "timed 'up and go'", "test", "balance", "child" and "adolescent". In order to obtain more specific results on the topic, searches were limited to title/abstract and to papers published from 1990 to 2012. All abstracts identified using these terms were reviewed, and those that addressed the proposed topic were fully examined. The reference list of the selected articles was also examined, in order to obtain other relevant articles. The study included only articles that evaluated or used the TUG test in children and adolescents with an observational or experimental design. Exclusion criteria consisted of abstracts from annals of events and articles using the TUG test in adults and elderly people. No review articles or case reports on the topic were found.

After studies were selected, according to the previously described criteria, they were critically read, in order to systematize test implementation and the main methodological aspects involved. To do so, the following categories were defined: general characteristics of the studies, populations, implementation METHODS, result interpretation, and associations with other measures.

Results and Discussion

Search strategies identified 56 references. According to the established inclusion and exclusion criteria, the reading of titles and abstracts allowed us to exclude 26 articles. Thus, 30 studies were reviewed in full and in more detail, of which three were excluded for not meeting the criteria and 27 were selected for this review.

General characteristics of the studies

Of the 27 studies included in the review, 17 (63%) were cross-sectional( 15 - 31 ) and 10 (37%) were clinical trials( 32 - 41 ). Only one article had the primary OBJECTIVE of evaluating the test in children and adolescents( 17 ). Fifteen studies included the TUG test as one of the outcome measures for their primary OBJECTIVE of assessing functional balance( 15 , 16 , 20 , 22 - 24 , 28 , 30 ), functional mobility(19,25-27,29,31) or activity( 18 ), according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)( 42 ). Of the remaining articles, nine used the TUG test as a secondary outcome measure for the evaluation of some type of intervention( 32 - 35 , 37 - 41 ) and two used it for the concurrent validation of other tests( 21 , 29 ).

Populations

As for the population assessed in the articles, children from different nationalities were evaluated by the TUG test. Most studies evaluated American children and adolescents( 19 , 21 , 25 - 29 , 31 , 35 , 38 , 40 ); two of them evaluated Australians( 17 , 18 ); two of them, the Chinese( 15 , 32 ); five of them, Israelis( 16 , 22 - 24 , 36 ); three of them, Spaniards( 34 , 39 , 41 ); one of them, the English( 37 ); one of them, Brazilians( 33 ); and two of them, Pakistanis( 20 , 30 ). The main clinical diagnoses identified in the study samples are shown in Table 1, with CP being the most frequent.

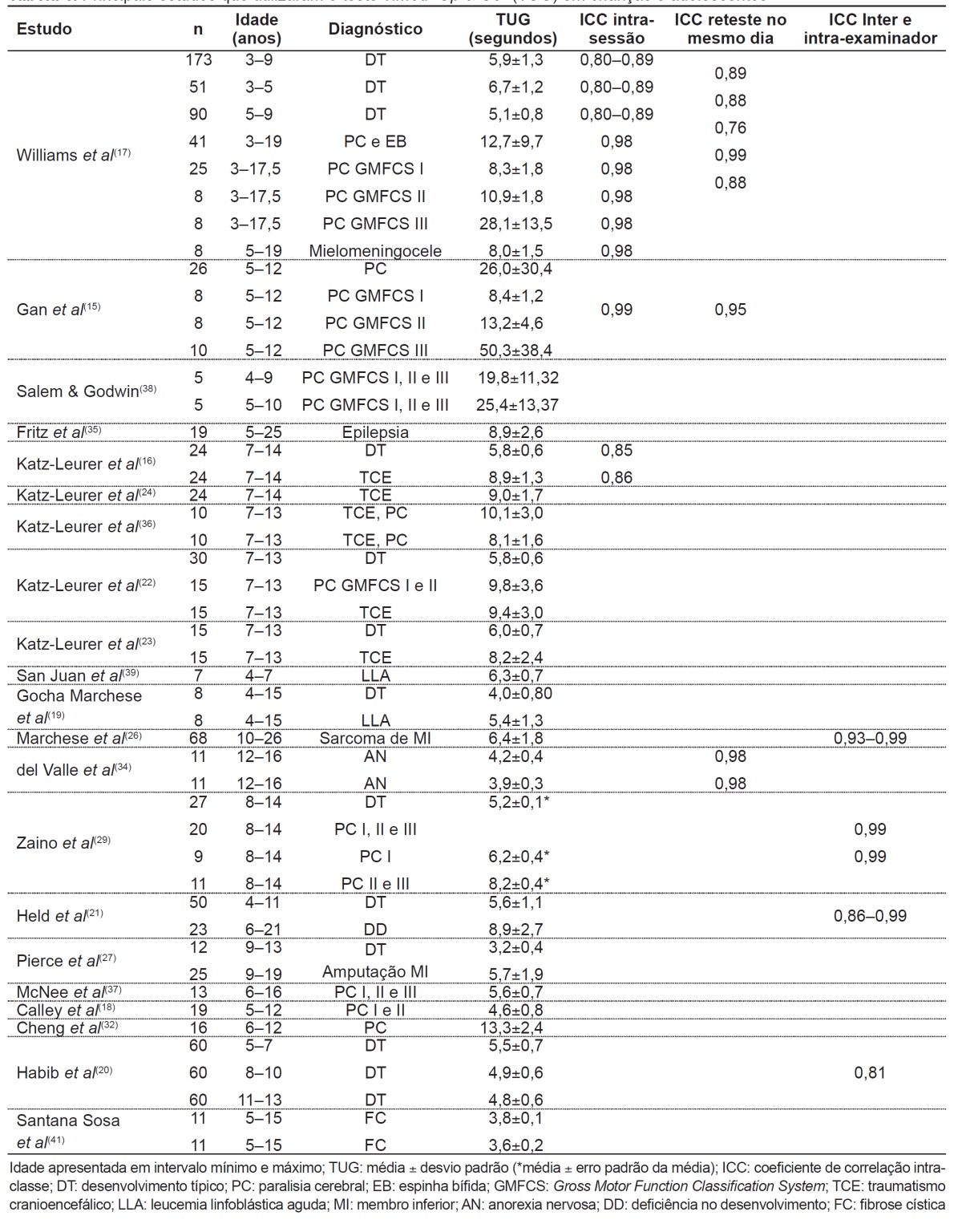

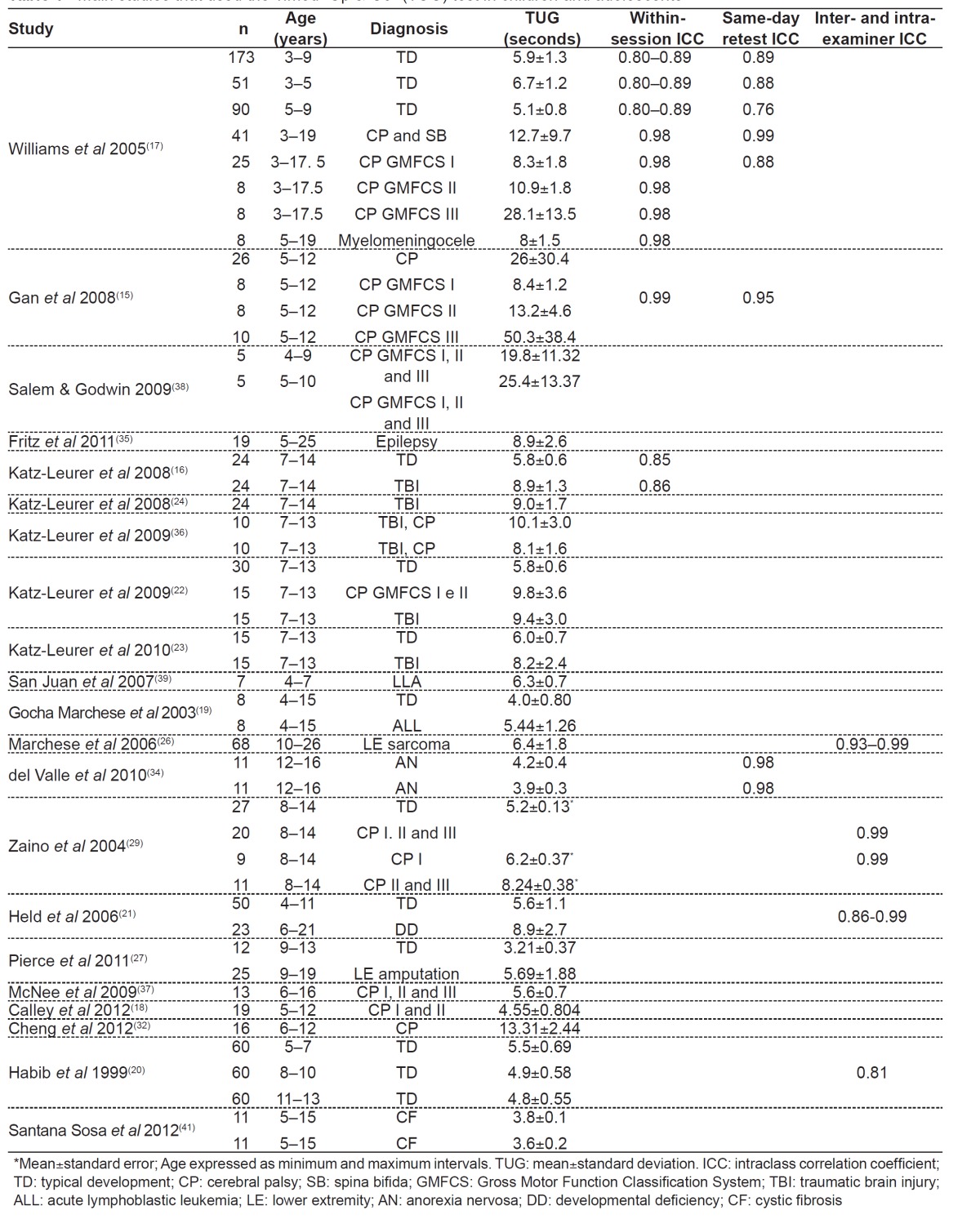

Table 1. Main studies that used the Timed "Up & Go" (TUG) test in children and adolescents.

Up to now, only one group of researchers( 20 , 30 ) evaluated the TUG test specifically in children and adolescents with typical development (TD), aiming to describe normal parameters. Another study developed reference values for the Functional Mobility Assessment tool, which includes the TUG test in one of its categories( 31 ). However, several studies included a population with these characteristics, in order to compare this population with that of children with specific conditions( 16 - 19 , 21 - 24 , 27 , 29 ).

Most studies with CP patients included children and adolescents from three to 19 years old( 15 , 17 , 18 , 22 , 29 , 32 , 33 , 36 - 38 , 40 ). On the other hand, the only studies with children and adolescents with DS evaluated four five-year old boys, seven girls from eight to 14 years( 28 ), and two subjects from six to 21 years( 21 ). Typically-developed subjects evaluated by the TUG test were aged from three to 15 years old( 16 - 20 , 22 - 24 , 27 , 29 , 30 ), and only three studies had significant samples( 17 , 20 , 30 ). CP children evaluated by the test showed the following Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) levels( 43 ): I and II( 18 , 22 , 33 , 36 ); I, II and III( 15 , 37 , 38 , 40 ).

Evaluation of the methodology used

As for the equipment used in the TUG test, some studies describe chairs with backrest and without armrest( 17 , 38 ), with backrest and armrest( 20 , 21 , 30 , 32 ), without backrest nor armrest( 15 ); in most studies, this was not described in the methodology section( 16 , 19 , 22 - 29 , 31 , 34 - 37 , 39 - 41 ). The height of the seat was described as adjustable in some studies( 16 , 20 , 22 - 24 , 29 , 30 , 33 , 36 ), was selected with the individual with feet flat on the floor and hip and knees flexed to 90°( 15 - 17 , 20 , 22 - 24 , 29 , 30 , 33 , 36 ), or was not reported( 19 , 21 , 25 - 28 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 37 - 41 ). A study used a bench and did not describe adjustments for height( 18 ). The original article by the authors of the TUG test recommended the use of a standard chair with armrest and an approximate height of 46cm( 1 ). The paper that described in more detail the methodology used to perform the test in the pediatric population was the same that had the primary OBJECTIVE of investigating the TUG test in children and recommended the use of a chair with backrest but without arms and height respecting 90° of knee flexion, measured with a goniometer( 17 ).

Most studies maintained the original route of the test, which was of 3m( 15 - 26 , 29 , 30 , 32 - 34 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 41 ), with the chair positioned at this distance from different points: a wall( 17 ), a line on the floor( 1 , 21 , 38 ), a mark on the floor( 16 , 22 - 24 , 36 ), a cone( 27 ), or a strip placed on the floor( 20 , 30 ). One study considered a distance of 9m for the route( 28 ), another used 10ft (3.048m) as the unit of measurement( 27 ), an two used another test with a distance of 10m in addition to the 3-m one, describing them as TUG 10m and TUG 3m( 34 , 39 ). Four studies did not report the route used, although providing bibliographical references for the test( 31 , 35 , 37 , 40 ). The article that adapted the test to the pediatric population maintained the distance of 3m( 17 ).

Some changes were made to the TUG test to evaluate children and adolescents. The study that adapted the test to children proposed to use the concrete task of touching their hands on a target on the wall( 17 ). Other modifications to the original TUG test were: verbal instructions repeated during the test( 17 ), demonstration of the test tasks( 17 , 21 , 38 ), and an unrecorded practice trial( 16 , 21 , 33 ). Qualitative speed instructions were provided in some studies( 15 , 20 , 33 ), such as "walk as fast as you can, but keep walking"( 15 , 20 , 30 ), or "perform the task as fast as you can"( 33 ). Other studies provided non-qualitative instructions( 17 , 32 , 38 ), e.g., "children instructed to walk at their preferred speed or pace"( 32 , 38 ), or "this is not a race, you must walk only"( 17 ). Most papers did not report this type of instruction( 16 , 18 , 19 , 21 - 29 , 31 , 34 - 37 , 39 - 41 ).

Time, measured by a chronometer, began to be recorded as children left and stopped as they returned to the chair( 17 ) or were recorded from the "go" cue to when the child sat down in the chair( 15 , 16 , 22 - 24 , 29 , 36 ), or this information was not provided( 18 - 21 , 25 - 28 , 30 - 35 , 37 - 41 ). In the original study of the test in elderly people( 1 ), timing started at the command "go" and stopped as subjects' back touched the chair again, in order to evaluate participants' cognition. In the adaptation of the test to children( 17 ), in order to measure movement time only, the chronometer started as children left the chair and stopped as they sat down again. Some studies also reported what children were wearing during the test: comfortable tennis shoes( 15 , 22 - 24 , 32 , 33 , 36 ), orthotics( 15 , 22 - 24 , 33 , 36 ), or no shoes( 29 ); other studies also reported the possibility of using gait assistive devices( 15 , 32 , 38 ), such as crutches( 17 , 25 ) and walkers( 17 ).

As for the number of trials in the test, studies performed three trials( 15 - 17 , 21 ), two trials( 17 , 20 , 22 - 24 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 36 ), a single trial( 38 ), or this information was not provided (18,19,25-28,31,33-35,37,39-41). The value considered as the test result was: the best value (i.e., the lowest) out of three trials( 15 , 17 ), the best value out of two trials( 17 , 29 ), the mean of two trials( 20 , 22 - 24 , 30 , 32 , 36 ), the only trial conducted( 38 ), or this information was not provided( 16 , 18 , 19 , 21 , 25 - 28 , 31 , 33 - 35 , 37 , 39 - 41 ). The original article in adults( 1 ) mentioned performing a trial for familiarization and another one with time recording; in turn, the article that adapted the test to Pediatrics( 17 ) recommended to perform three trials, recording the lowest score achieved by children with TD, and two trials, recording the lowest score achieved by children with CP and spina bifida (SB).

Methodological differences in test implementation are common in adult and pediatric populations, which makes it difficult to establish an universal measure. A study in adults evaluated whether changes in test methodology or in the instructions provided could interfere with results and concluded that, in elderly people, both verbal instructions and methodology affect test results. In young adults, instructions affect TUG results, but markers (line on the floor or cone) do not. In addition, it was observed that the variability in the results was smaller when instructions on speed were provided( 44 ). There are no studies evaluating the influence of these changes on the pediatric population. Thus, it can be suggested that, in order to evaluate the TUG test in children and adolescents, the proposed adaptations to Pediatrics should be used( 17 ), combined with instructions on speed, such as "walk as fast as you can".

Result interpretation

Table 1 shows the studies that evaluated children and adolescents and reported mean, standard deviation and/or intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for within-session, between-session (test-retest), intra-examiner and inter-examiner reliability. In articles that reported pre- and post-intervention measures, the pre-intervention score was considered. The time it took for children with TD to perform the TUG test had a mean variation of 3.21( 27 ) to 6.7 seconds( 17 ). Children showed improvement in balance as age increased, with a decrease in mean score( 17 , 20 , 30 ). In one study, there was no significant difference in the scores of male and female children and adolescents( 17 ); in another one, there was significant difference in the scores, with boys showing better performance in the TUG test( 20 , 30 ). Of these studies, only one used a multiple linear regression model and evaluated the effect of anthropometric variables on TUG values of individuals from five to 13 years old, with test scores being influenced by age in the general sample (R2=0.18)( 30 ). The remaining studies reported means and standard deviations( 17 , 20 ) or median and ranges( 31 ) of TUG values for children and adolescents.

On the other hand, in children and adolescents with specific clinical diagnosis, the time required to perform the TUG test had a mean variation from 3.6( 41 ) to 50.3(15) seconds. Of the two studies that evaluated children and adolescents with DS, one was not included in Table 1 because it used a route of 9m( 28 ). In addition, its results did not report TUG mean; only ICC was below 0.5 in the female group (n=7; eight to 14 years old) and in the male group (n=4; five years old)( 28 ). The other study with subjects with DS that appears in Table 1 reported the mean score and the whole sample of individuals were developmentally-disabled( 21 ).

Associations of the test with other measures

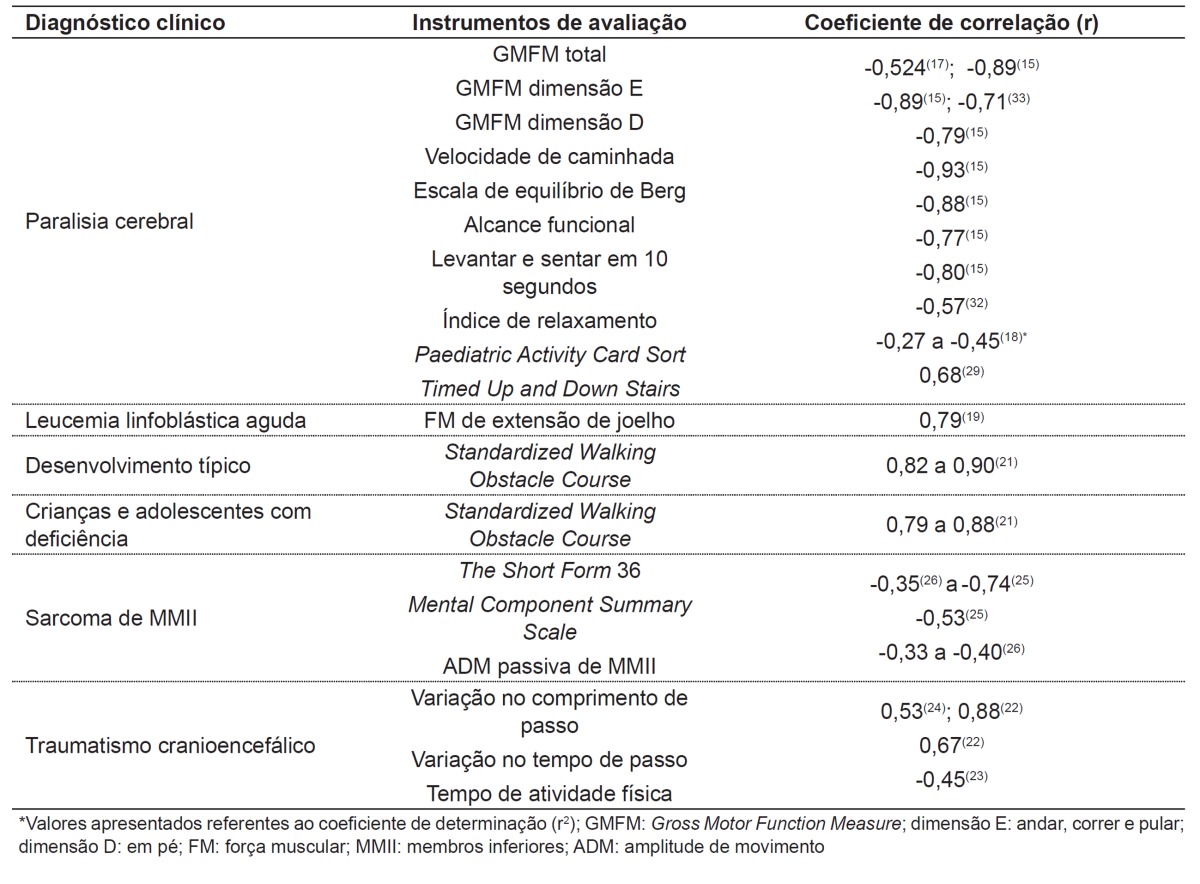

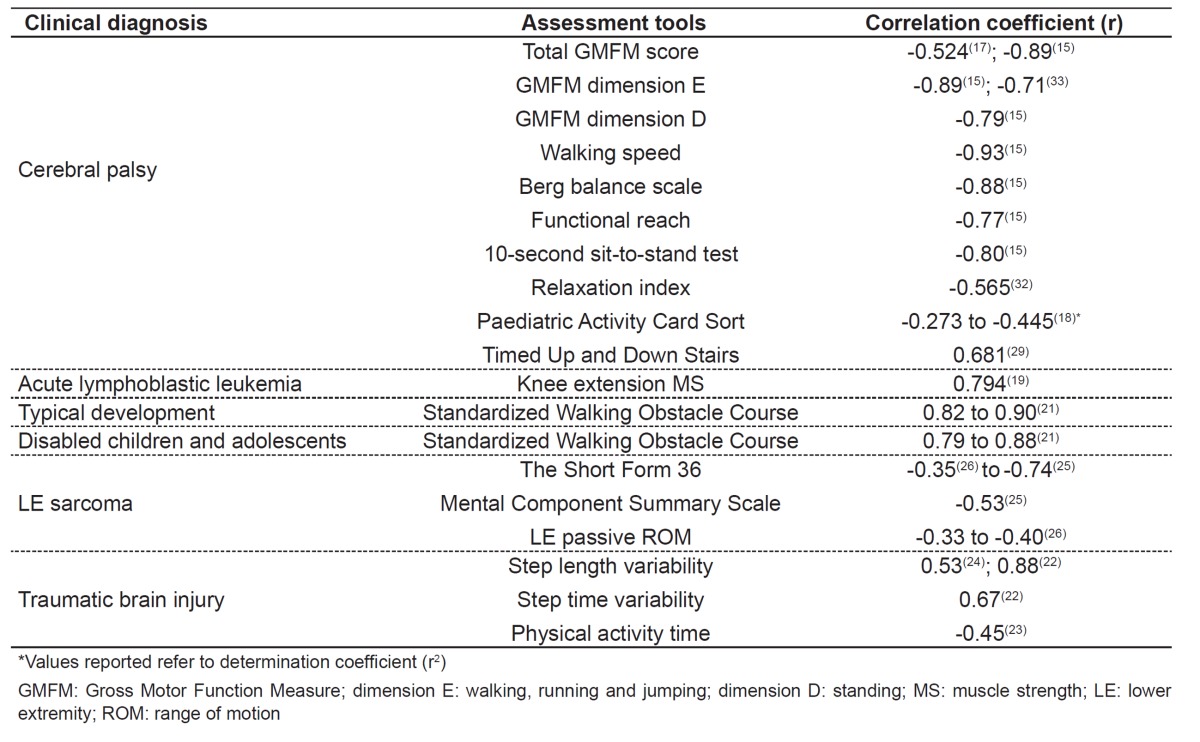

Several studies correlated the TUG test with other assessment tools, including motor function, functional mobility, range of motion (ROM), muscle strength, and quality of life. Generally speaking, these correlations are specific for certain clinical diagnoses and vary according to the tool studied. The main results for the associations between the TUG test and other measures are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Main correlations of the Timed "Up & Go" test with other assessment tools in children and adolescents.

On the other hand, only one study with sarcoma survivors used multiple and simple regression analyses to explain the result of the TUG test by other variables( 26 ). The variance in the test may be explained 5% by hip extension active ROM, 5% by knee extension passive ROM, and 16% by knee flexion active ROM. In addition, the mental and physical components summarized in the quality of life questionnaire - The Short Form 36 Health Survey, version two (SF36v2) - were significant predictors of TUG time in this population, explaining 26 (p=0.01) and 14% (p=0.01) of test variance, respectively( 26 ).

Final comments

The results of this review demonstrate that there are neither reference equations yet for the TUG test in children and adolescents with TD nor information about the influence of possible predictive variables for the test in the age group from 13 to 18 years old. In children and adolescents with specific clinical diagnoses, the within-session reliability coefficient was found to be high in most studies, as well as intra- and inter-examiner reliability, characterizing the good reproducibility of the test.

Thus, the TUG test was shown to be a good tool to assess functional mobility in the pediatric population and correlated with other tests of balance, functional mobility, gross motor function, quality of life, muscle strength, ROM, functional capacity, and physical activity level. This review may help therapists in the evaluation of functional mobility in children and adolescents by the TUG test. Future studies aiming to determine normative values for healthy children and adolescents are required to improve the evaluation of individuals with specific clinical diagnoses.

Footnotes

Instituição: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil

References

- 1.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed "Up & Go": a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathias S, Nayak US, Isaacs B. Balance in elderly patients: the "get-up and go" test. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1986;67:387–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pondal M, del Ser T. Normative data and determinants for the timed "up and go" test in a population-based sample of elderly individuals without gait disturbances. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2008;31:57–63. doi: 10.1519/00139143-200831020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohannon RW. Reference values for the timed up and go test: a descriptive meta-analysis. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2006;29:64–68. doi: 10.1519/00139143-200608000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creel GL, Light KE, Thigpen MT. Concurrent and construct validity of scores on the Timed Movement Battery. Phys Ther. 2001;81:789–798. doi: 10.1093/ptj/81.2.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giné-Garriga M, Guerra M, Marí-Dell'Olmo M, Martin C, Unnithan VB. Sensitivity of a modified version of the 'timed get up and go' test to predict fall risk in the elderly: a pilot study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:e60–e66. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shumway-Cook A, Brauer S, Woollacott M. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the Timed Up & Go Test. Phys Ther. 2000;80:896–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steffen TM, Hacker TA, Mollinger L. Age- and gender-related test performance in community-dwelling elderly people: Six-Minute Walk Test, Berg Balance Scale, Timed Up & Go Test, and gait speeds. Phys Ther. 2002;82:128–137. doi: 10.1093/ptj/82.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersson C, Grooten W, Hellsten M, Kaping K, Mattsson E. Adults with cerebral palsy: walking ability after progressive strength training. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45:220–228. doi: 10.1017/s0012162203000446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris S, Morris ME, Iansek R. Reliability of measurements obtained with the Timed "Up & Go" test in people with Parkinson disease. Phys Ther. 2001;81:810–818. doi: 10.1093/ptj/81.2.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flansbjer UB, Holmbäck AM, Downham D, Patten C, Lexell J. Reliability of gait performance tests in men and women with hemiparesis after stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37:75–82. doi: 10.1080/16501970410017215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng SS, Hui-Chan CW. The timed up & go test: its reliability and association with lower-limb impairments and locomotor capacities in people with chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1641–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faria CD, Teixeira-Salmela LF, Nadeau S. Effects of the direction of turning on the timed up & go test with stroke subjects. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2009;16:196–206. doi: 10.1310/tsr1603-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carmeli E, Kessel S, Coleman R, Ayalon M. Effects of a treadmill walking program on muscle strength and balance in elderly people with Down syndrome. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M106–M110. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.2.m106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gan SM, Tung LC, Tang YH, Wang CH. Psychometric properties of functional balance assessment in children with cerebral palsy. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008;22:745–753. doi: 10.1177/1545968308316474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz-Leurer M, Rotem H, Lewitus H, Keren O, Meyer S. Functional balance tests for children with traumatic brain injury: within-session reliability. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2008;20:254–258. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0b013e3181820dd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams EN, Carroll SG, Reddihough DS, Phillips BA, Galea MP. Investigation of the timed 'up & go' test in children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:518–524. doi: 10.1017/s0012162205001027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calley A, Williams S, Reid S, Blair E, Valentine J, Girdler S. A comparison of activity, participation and quality of life in children with and without spastic diplegia cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:1306–1310. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.641662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gocha Marchese V, Chiarello LA, Lange BJ. Strength and functional mobility in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;40:230–232. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Habib Z, Westcott S, Valvano J. Assessment of balance abilities in Pakistani children: a cultural perspective. Pediatric Physical Therapy. 1999;11:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Held SL, Kott KM, Young BL. Standardized walking obstacle course (SWOC): reliability and validity of a new functional measurement tool for children. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2006;18:23–30. doi: 10.1097/01.pep.0000202251.79000.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz-Leurer M, Rotem H, Keren O, Meyer S. Balance abilities and gait characteristics in post-traumatic brain injury, cerebral palsy and typically developed children. Dev Neurorehabil. 2009;12:100–105. doi: 10.1080/17518420902800928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz-Leurer M, Rotem H, Keren O, Meyer S. Recreational physical activities among children with a history of severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2010;24:1561–1567. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2010.523046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz-Leurer M, Rotem H, Lewitus H, Keren O, Meyer S. Relationship between balance abilities and gait characteristics in children with post-traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2008;22:153–159. doi: 10.1080/02699050801895399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchese VG, Ogle S, Womer RB, Dormans J, Ginsberg JP. An examination of outcome measures to assess functional mobility in childhood survivors of osteosarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;42:41–45. doi: 10.1002/pbc.10462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marchese VG, Spearing E, Callaway L, Rai SN, Zhang L, Hinds PS, et al. Relationships among range of motion, functional mobility, and quality of life in children and adolescents after limb-sparing surgery for lower-extremity sarcoma. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2006;18:238–244. doi: 10.1097/01.pep.0000232620.42407.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierce S, Fergus A, Brady B, Wolff-Burke M. Examination of the functional mobility assessment tool for children and adolescents with lower extremity amputations. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2011;23:171–177. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0b013e318218f0b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villamonte R, Vehrs PR, Feland JB, Johnson AW, Seeley MK, Eggett D. Reliability of 16 balance tests in individuals with Down syndrome. Percept Mot Skills. 2010;111:530–542. doi: 10.2466/03.10.15.25.PMS.111.5.530-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaino CA, Marchese VG, Westcott SL. Timed up and down stairs test: preliminary reliability and validity of a new measure of functional mobility. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2004;16:90–98. doi: 10.1097/01.PEP.0000127564.08922.6A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Habib Z, Westcott S. Assessment of anthropometric factors on balance tests in children. Pediatr Phys Ther. 1998;10:101–109. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marchese VG, Oriel KN, Fry JA, Kovacs JL, Weaver RL, Reily MM, et al. Development of reference values for the Functional Mobility Assessment. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2012;24:224–230. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0b013e31825c87e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng HY, Ju YY, Chen CL, Wong MK. Managing spastic hypertonia in children with cerebral palsy via repetitive passive knee movements. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44:235–240. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Campos AC, da Costa CS, Rocha NA. Measuring changes in functional mobility in children with mild cerebral palsy. Dev Neurorehabil. 2011;14:140–144. doi: 10.3109/17518423.2011.557611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Del Valle MF, Pérez M, Santana-Sosa E, Fiuza-Luces C, Bustamante-Ara N, Gallardo C, et al. Does resistance training improve the functional capacity and well being of very young anorexic patients? A randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fritz SL, Rivers ED, Merlo AM, Reed AD, Mathern GD, De Bode S. Intensive mobility training postcerebral hemispherectomy: early surgery shows best functional improvements. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2011;47:569–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz-Leurer M, Rotem H, Keren O, Meyer S. The effects of a 'home-based' task-oriented exercise programme on motor and balance performance in children with spastic cerebral palsy and severe traumatic brain injury. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:714–724. doi: 10.1177/0269215509335293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNee AE, Gough M, Morrissey MC, Shortland AP. Increases in muscle volume after plantarflexor strength training in children with spastic cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51:429–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salem Y, Godwin EM. Effects of task-oriented training on mobility function in children with cerebral palsy. NeuroRehabilitation. 2009;24:307–313. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2009-0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.San Juan AF, Fleck SJ, Chamorro-Viña C, Maté-Muñoz JL, Moral S, García-Castro J, et al. Early-phase adaptations to intrahospital training in strength and functional mobility of children with leukemia. J Strength Cond Res. 2007;21:173–177. doi: 10.1519/00124278-200702000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu YN, Hwang M, Ren Y, Gaebler-Spira D, Zhang LQ. Combined passive stretching and active movement rehabilitation of lower-limb impairments in children with cerebral palsy using a portable robot. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25:378–385. doi: 10.1177/1545968310388666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santana Sosa E, Groeneveld IF, Gonzalez-Saiz L, López-Mojares LM, Villa-Asensi JR, Barrio Gonzalez MI, et al. Intrahospital weight and aerobic training in children with cystic fibrosis: a randomized controlled trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:2–11. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318228c302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Organização Mundial da Saúde . Direcção-geral da Saúde.CIF: Classificação in ternacional de funcionalidade, incapacidade e saúde. São Paulo: Edusp; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palisano RJ, Kolobe TH, Haley SM, Lowes LP, Jones SL. Validity of the Peabody develop mental gross motor scale as an evaluative measure of infants receiving physical therapy. Phys Ther. 1995;75:939–948. doi: 10.1093/ptj/75.11.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bergmann JH, Alexiou C, Smith IC. Procedural differences directly affect timed up and go times. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:2168–2169. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]