Abstract

Objective:

To assess asthma among Brazilian pediatric population applying the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), an internationally standardized and validated protocol.

Data sources:

ISAAC was conceived to maximize the value of epidemiologic studies on asthma and allergic diseases, establishing a standardized method (self-applicable written questionnaire and/or video questionnaire) capable to facilitate the international collaboration. Designed to be carried out in three successive and dependent phases, the ISAAC gathered a casuistic hitherto unimaginable in the world and in Brazil. This review included data gathered from ISAAC official Brazilian centers and others who used this method.

Data synthesis:

At the end of the first phase, it has been documented that the prevalence of asthma among Brazilian schoolchildren was the eighth among all centers participating all over the world. Few centers participated in the second phase and investigated possible etiological factors, especially those suggested by the first phase, and brought forth many conjectures. The third phase, repeated seven years later, assessed the evolutionary trend of asthma and allergic diseases prevalence in centers that participated simultaneously in phases I and III and in other centers not involved in phase I.

Conclusions:

In Brazil, the ISAAC study showed that asthma is a disease of high prevalence and impact in children and adolescents and should be seen as a Public Health problem. Important regional variations, not well understood yet, and several risk factors were found, which makes us wonder: is there only one or many asthmas in Brazil?

Keywords: asthma, epidemiology, child, adolescent, risk factors

Abstract

Objetivo:

Evaluar el asma en la población pediátrica brasileña por el protocolo del International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), internacionalmente estandarizado y validado.

Fuentes de datos

: El ISAAC, idealizado para maximizar el valor de estudios epidemiológicos en asma y enfermedades alérgicas, estableció un método estandarizado (cuestionario escrito autoaplicable y/o video-cuestionario) capaz de facilitar la colaboración internacional. Concebido para realizarse en tres etapas sucesivas y dependientes, el ISAAC reunió una casuística hasta entonces inimaginable en el mundo y en Brasil. En esta visión, se reunieron los datos de centros brasileños oficiales del ISAAC y de otros que emplean su método.

Síntesis de los datos:

Finalizada la primera etapa, la prevalencia de asma entre escolares brasileños fue documentada como la octava en magnitud entre todos los centros participantes del estudio. Los pocos centros involucrados en la segunda etapa investigaron posibles factores etiológicos, especialmente aquellos sugeridos por los resultados de la primera etapa, y generaron muchas especulaciones. La tercera etapa, repetida tras siete años, evaluó la tendencia evolutiva de la prevalencia de asma y de las enfermedades alérgicas en los centros participantes simultáneamente en las etapas I y III y determinó la prevalencia en otros no involucrados en la etapa I.

Conclusiones:

En Brasil, el ISAAC demostró, de modo definitivo, que el asma es una enfermedad de alta prevalencia e impacto en niños y adolescentes, debiendo ser encarada como problema de Salud Pública. Se encontraron importantes variaciones regionales, todavía no bien aclaradas, así como diversos factores de riesgo, lo que nos hace cuestionar: ¿hay en Brasil una o muchas asmas?

Introduction

The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), created in 1990 to maximize the value of epidemiological studies of asthma and allergic diseases, established a standardized method that facilitated international collaboration, from the establishment of a protocol used worldwide( 1 ). Its specific points were: a) to describe the prevalence and severity of asthma, rhinitis, and eczema in children living at different locations and to draw comparisons between them and between countries; b) obtain baseline measures to assess future trends in the prevalence and severity of this diseases; c) provide support for further etiologic studies in genetics, lifestyle, medical care, and air pollution, that may affect these diseases( 1 ).

The ISAAC was conceived to be carried out in three successive and dependent phases. In the first phase, the study of the compulsory core was developed to assess the prevalence and severity of asthma and allergic diseases in selected populations, using a standardized questionnaire; in the second phase, possible etiological factors were investigated, especially those suggested by the results in the previous phase; in the third phase, the first phase was repeated after a minimum period of 5 years, evaluating the evolutionary trend in the prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases in a given period, including centers that participated in phases I and III simultaneously. In addition, the prevalence of other countries was determined, which, although not involved in phase I, had interest in measuring the prevalence of asthma and its severity, as well as the risk factors associated with the development of the disease, both environmental and of lifestyle, specific to each community( 1 ).

Collections instruments

The instruments of data collection are the ISAAC video questionnaire (VQ) and the written questionnaire (WQ).

The VQ consists of five scenes, where several individuals are presented with pictures of asthma in different intensities and situations, to be answered by adolescents( 1 ). The WQ is composed of three modules, which address asthma, rhinitis, and atopic eczema, respectively. The WQ is presented in two versions: one for children aged from 6 to 7 years, answered by parents and/or guardians, and another answered by the adolescents themselves. The question "wheezing in the last year" is the one that gathers higher sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of asthma, being universally used to identify individuals with active asthma( 1 ).

Originally written in English, the ISAAC WQ was validated to be used worldwide. In localities where the language was different, it was recommended that it be translated and validated for its appropriate use( 1 ). Thus, in our location, the ISAAC WQ was translated into Brazilian Portuguese, back-translated into English, and then validated by criterion and constructively, confirming that their diagnostic characteristics were not modified( 2 ). More recently, the ISAAC directive committee published a study that highlights the importance of cultural norms that must be considered in the evaluation of back-translation into English, often allowing linguistic deviations in order to maintain the original meanings( 3 ).

Although the VQ was designed to overcome barriers imposed by language and possible distortions arising from translations of the WQ, its application in the world did not supplant that of the WQ. In Brazil, the WQ was the only one to be used. However, due to the various denominations that asthma receives, some authors added questions with synonyms usually used to define the disease in the WQ, in order to improve the diagnostic power of the instrument( 4 ). Named by many as bronchitis, the inclusion of the question did not improve the diagnostic power of the ISAAC WQ in children( 4 ).

Taking as a base the structure employed in other national population surveys, for instance, the survey on weight, Valle et al validated the ISAAC WQ, as well as its reproducibility, administering it through telephone interview. Parents/caregivers of children (6-7 years old) with or without asthma were interviewed in their homes on two occasions, with an interval of 15 days, and responded to the ISAAC WQ by telephone, evaluating the reproducibility of responses to the questions, given by the same respondent. The question "wheezing in the last year" had a perfect concordance index, enhancing the reproducibility of the instrument administered via telephone( 5 ).

ISAAC Phase I

The compilation of worldwide data from ISAAC phase I gathered a significant number of children (6-7 years; n=257,800; 91 centers in 38 countries) and adolescents (13-14 years; n=463,801; 155 centers in 56 countries) never previously evaluated and showed great variability in rates between the different participating centers( 6 ).

In Brazil, the first ISAAC phase, completed in 1996, was a real watershed in knowledge of the prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases in the country. Before, the Brazilian epidemiological data available were restricted to small population samples, especially in large urban centers and educational institutions, without any standardization in their production, which made it very difficult to compare them.

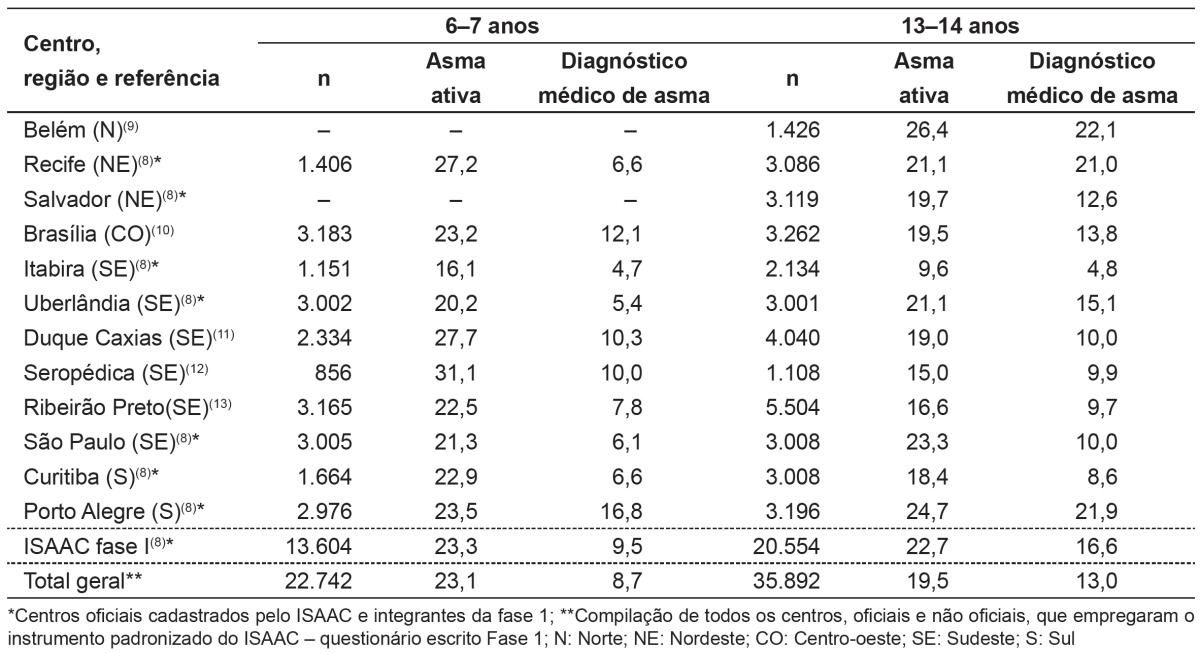

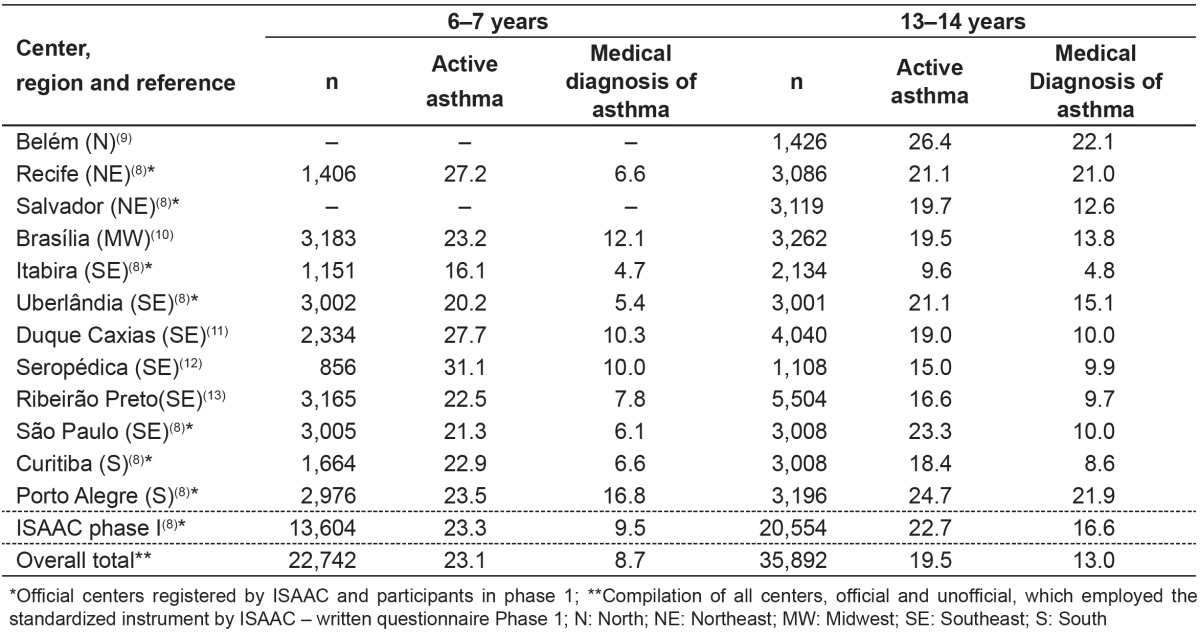

In Brazil, seven centers that enabled obtaining reliable data on the prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic eczema in children and adolescents participated in this phase. The comparative analysis with all the global data obtained showed that the average prevalence of asthma in children and adolescents is high (Table 1), being the eighth among the centers with the highest prevalence - English-speaking countries and Latin America( 7 ). As for asthma, in this first phase, it was observed that the use of the medical diagnosis as epidemiological criterion for identifying patients with asthma would induce an underdiagnosis, since the prevalence of the active disease (wheezing in the last year) reached twice as much as the medical diagnosis( 8 ). This fact is corroborated, as in the validation of the WQ, it was found that only 50% of adolescents with asthma, regularly followed in a specialized service, identified themselves as having asthma( 2 ).

Table 1. Prevalence of active asthma (wheezing in the past 12 months) and physician-diagnosed asthma in school children from official centers and other Brazilian centers that used the protocol of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) - Phase 1.

Other researchers, even without the recognition of the central committee of the ISAAC, used the standard WQ and the protocol, obtaining the prevalence data summarized in Table 1. The mean prevalence of active asthma was 23.3% for children and 22.7% for adolescents (Table 1).

Taking the data from around the world, there was a 20-fold variation in the prevalence of asthma and related symptoms (ranging between 1.8 and 36.7%), being the environmental factors the main responsible for this variation( 14 ). English-speaking countries and centers in Latin America were among those with the highest prevalence.

Next, to check the possible factors involved in differences in prevalence observed in the various centers involved in ISAAC Phase I, ecological studies were conducted. Anderson et al evaluated the relationship of national immunization rates against tuberculosis, diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus (DPT) and measles with the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis, and atopic eczema. A negative and significant association was observed between adolescents and immunization against measles and DTP, but not against tuberculosis( 15 ). In another study, we observed a significant inverse relationship between humidity and mean annual temperature variation and prevalence of symptoms of asthma and allergic diseases( 16 ).

The use of antibiotics in early life and the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic eczema were also reasons of study. These indexes, adjusted for gross domestic product showed no association between the two variables( 17 ).

Air pollution is identified as a risk factor for the development of asthma and related symptoms, especially in regards to particulate matter (PM), resulting from burning oil. Anderson et al investigated the effect of environmental PM on the prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases, analyzing satellite data by estimates and adjustments according to the gross domestic product of the countries involved. Although the data suggested a relationship, there was no statistically significant confirmation between exposure to particulate matter from 10Î1/4 (PM10) and prevalence rates( 18 ).

On the other hand, Rios et al, assessed the prevalence of asthma and related symptoms in adolescents from two localities in the state of Rio de Janeiro, with different degrees of air pollution (PM10) - the municipality of Seropédica, little polluted, and the municipality of Duque de Caxias, very polluted - and found a significant association between exposure to higher levels of PM10 and greater prevalence of active asthma, as well as its intensity( 12 ).

ISAAC phase II

Performed only by a few centers in the world, this phase investigated possible etiological factors, especially those suggested by the results of the first phase, and explored new etiological hypotheses regarding the development of asthma and allergic diseases( 19 ). Therefore, this research protocol included the ISAAC WQ, complementary questionnaires including information on disease management, child's contacts, examination for flexural dermatitis, immediate skin tests with a battery of common aero-allergens, evaluation of bronchial responsiveness to hypertonic saline, blood collection and storage for the determination of total serum IgE and genetic analysis, besides the WQ on risk factors( 19 ). The latter was translated into Portuguese and started to be used in our country by other researchers, to evaluate the possible risk factors associated with the development of asthma. In Brazil, only one center participated in the second phase of ISAAC.

ISAAC phase III

Seven years after the completion of phase I, phase III was performed( 20 ), when the number of participating centers increased significantly, both for children from 6 to 7 years (144 centers in 61 countries), and for adolescents aged 13-14 years (233 centers in 97 countries), reaching 1,187,496 students assessed. Around the world, there was a slight increase in the mean prevalence of current asthma among adolescents (13.2 to 13.7%; mean annual growth of 0.06%) and among students from 6 to 7 years (11.0 to 11.6%; mean annual increase of 0.13%). In Latin America, these mean increases were higher: 0.32% per year for adolescents and 0.07% per year for children aged from 6 to 7 years( 21 ).

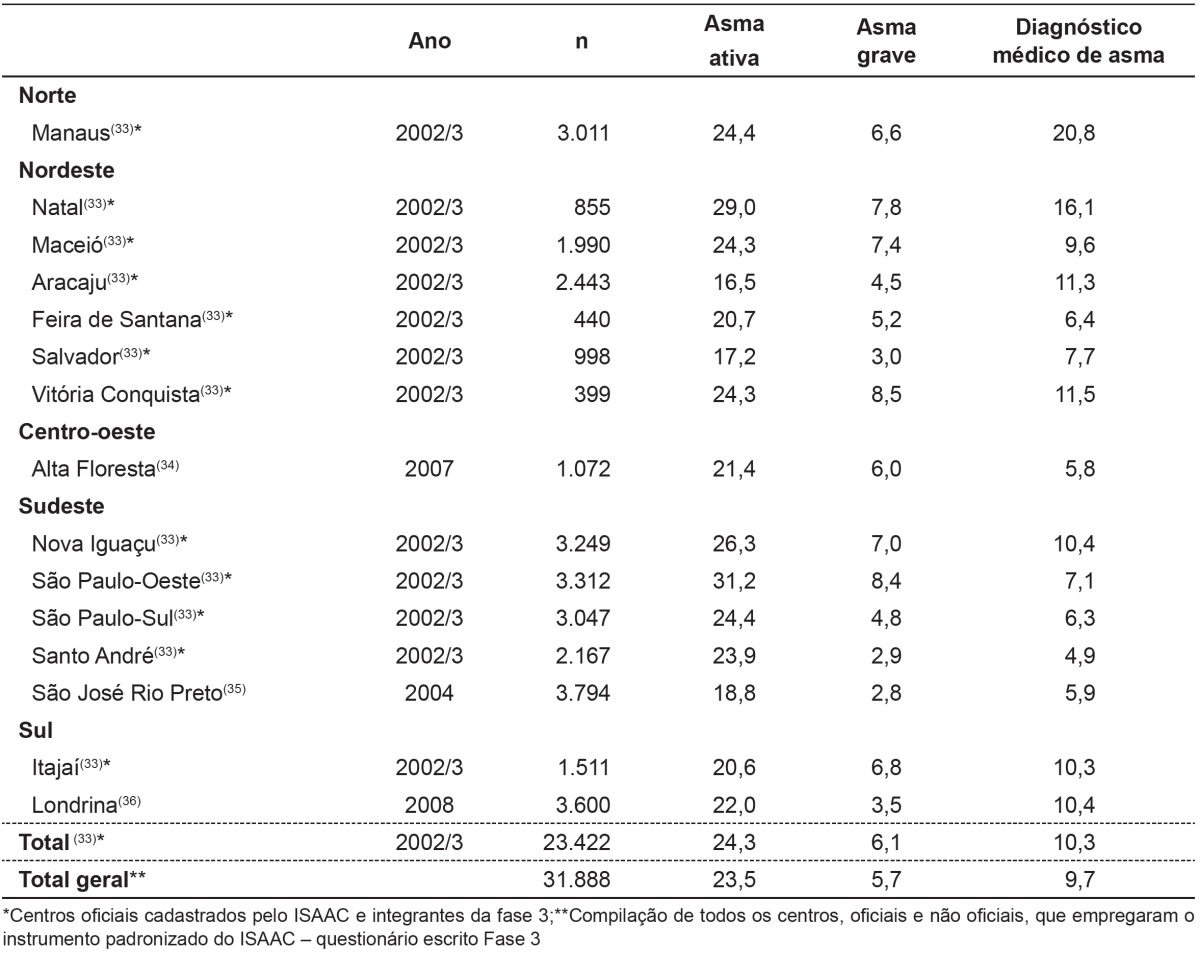

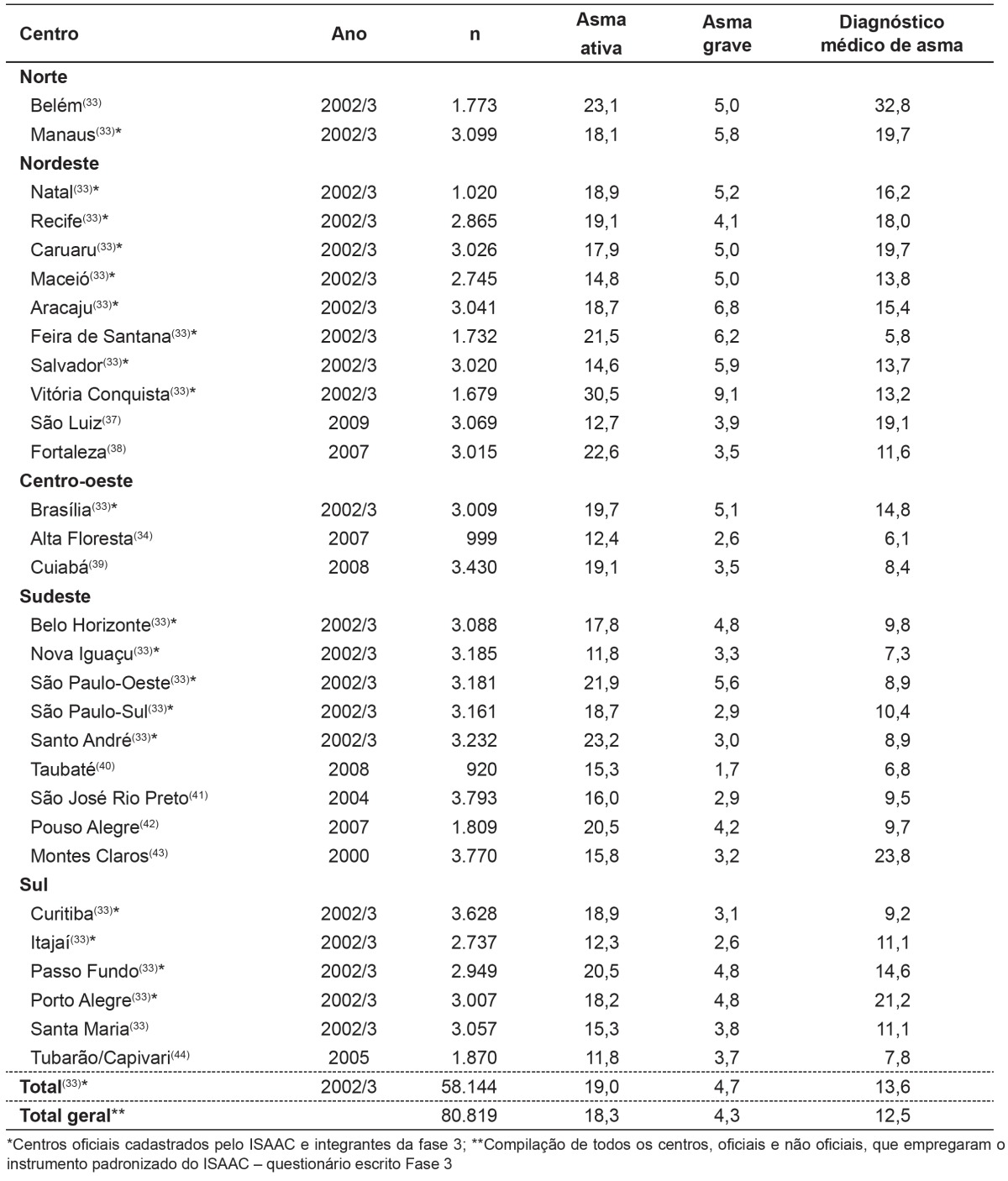

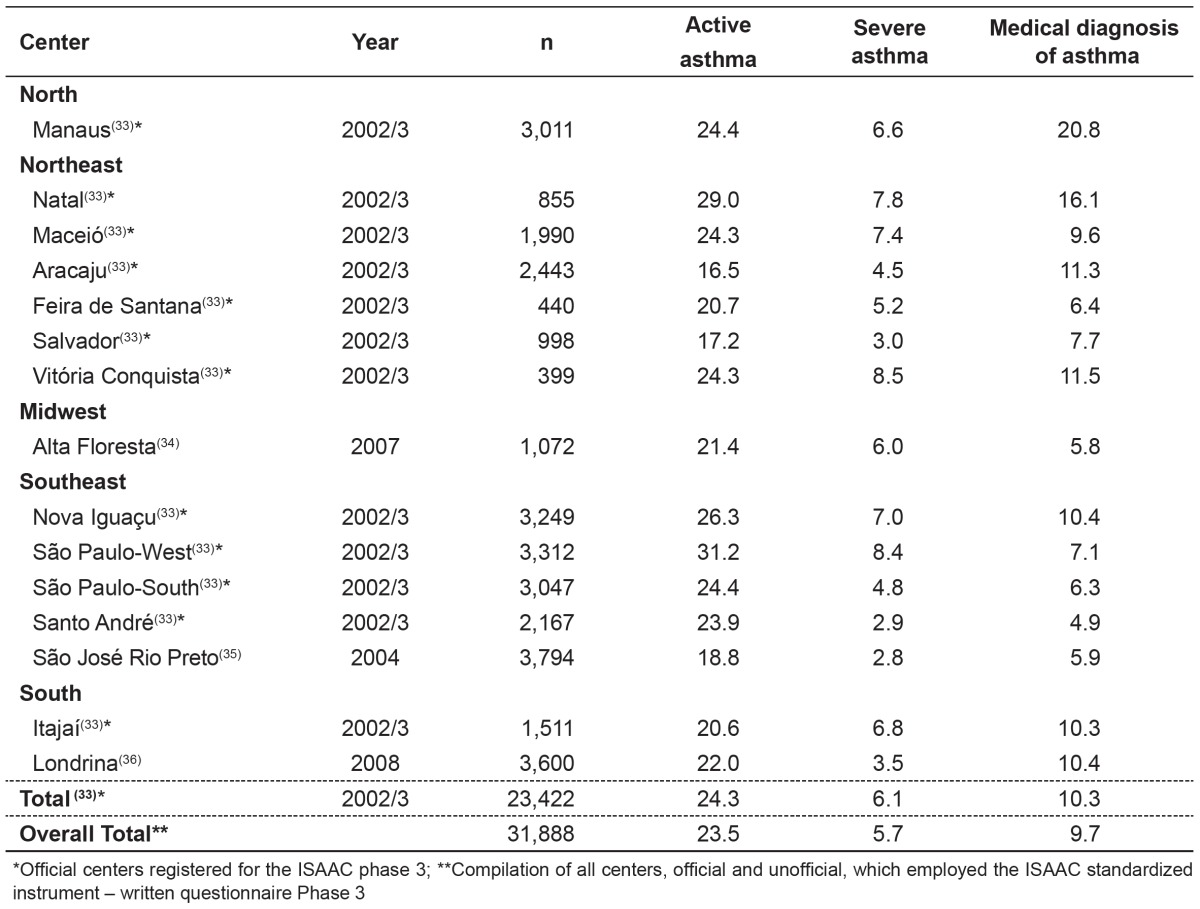

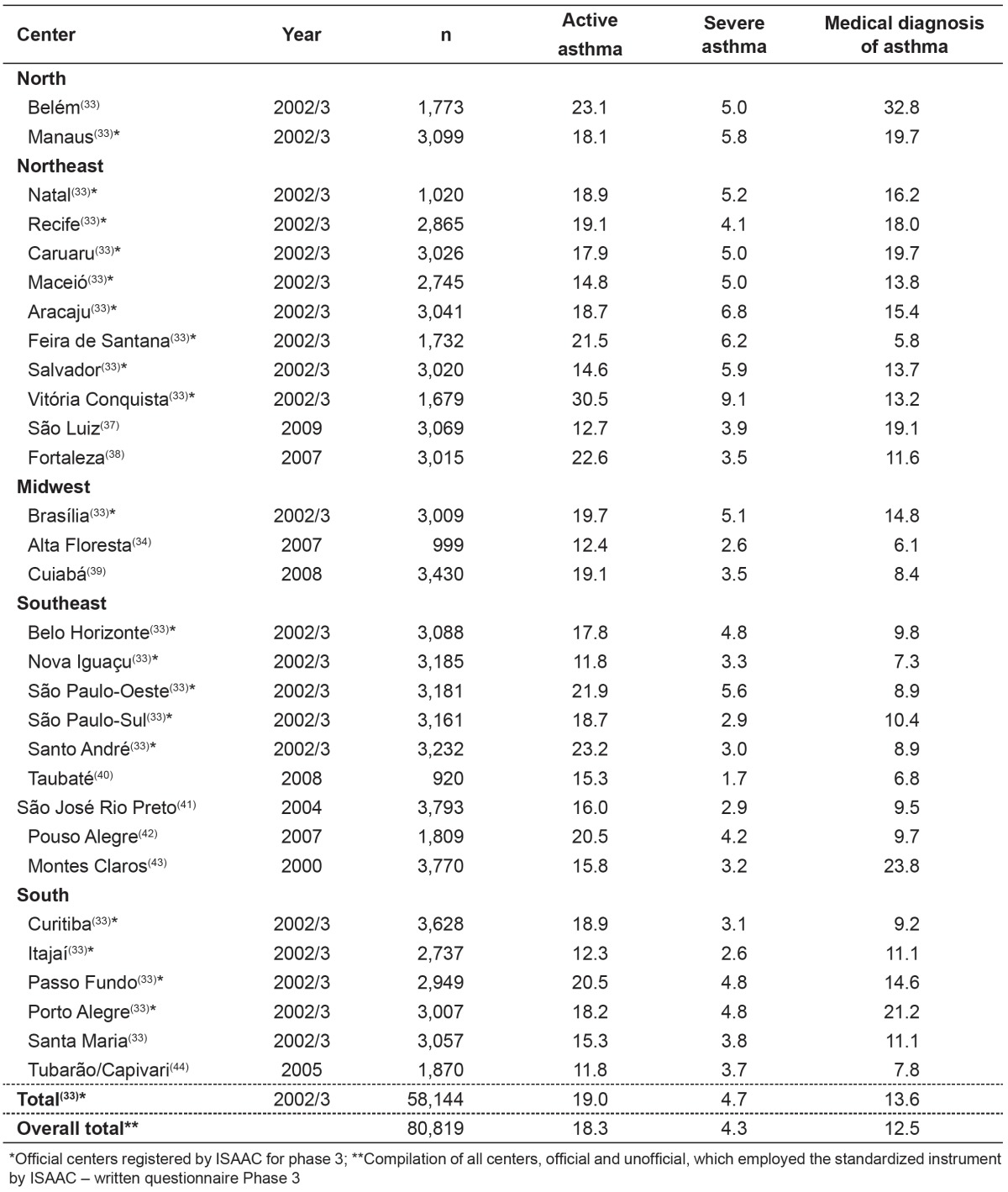

In Brazil, there was an increase in the number of participating centers to 21, as well as in the number of children (n=23,422) and adolescents (n=58,144) interviewed, with centers representing the different regions of the country( 19 ). The mean prevalence of asthma was 24.3% (ranging from 16.5 to 31.2%) for children and 19% (ranging from 11.8 to 30.5%) for adolescents, without relation with the socioeconomic status( 22 ).

To evaluate the temporal trend of prevalence of asthma's symptoms and atopic diseases, we performed the reapplication of the ISAAC WQ in centers that participated in phase I. However, some basic rules had to be followed to ensure the comparability of the method used( 23 ). The analysis of the centers involved showed that most of the participants of the two phases reapplied the ISAAC protocol properly, which was verified by the careful documentation with the use of standardized tools and checking( 23 ).

The analysis of data from the participating centers of the two phases showed that, in this range, the mean prevalence of asthma among adolescents fell from 22.7 to 19.9% (-0.4% per year). Nevertheless, it still remained among the highest averages( 24 ). Knowing the temporal evolution of allergic diseases in our location, we evaluated the interference of some infectious diseases over them, in the birth of adolescents participating in phase III of ISAAC. Thus, when assessing the possible relationship between the fall in the incidence of tuberculosis and measles, observed over the years, and the increase in allergic diseases, no relationship between them was documented( 25 ), contrary to what was observed by other investigators( 26 ).

The increase in the number of centers that participated in phase III allowed various studies to find reasons for the different rates observed in the country. One of the first ideas was to relate them to the socioeconomic status of the populations evaluated, not documenting association( 22 ), as it had already been done by the general coordinators of the projects involving data from phase I( 7 ). When evaluating the centers of the northeast region involved in phase III, there were very different levels of prevalence of asthma, i.e., 14.8% in Maceió, Alagoas, and 30.5% in Vitória da Conquista, Bahia. Would there be any reason for this difference? With this question in mind, these centers - Natal (Rio Grande do Norte), Recife and Caruaru (Pernambuco), Maceió (Alagoas), Aracaju (Sergipe), Salvador, Feira de Santana, and Vitória da Conquista (Bahia) -, evaluated the following parameters: latitude, mean annual temperature, altitude, human development index, GINI index, index of social exclusion (deprivation of water, sewer service, and garbage collection), illiteracy rate in people over 10 years and the percentage of households with minimum daily income below one U.S. dollar. The relationship between tropical climate and the high prevalence of asthma was associated with water deprivation and latitude( 27 ).

Living in a rural environment is a factor that has been identified as a protective factor for the development of asthma and allergic diseases. Evaluating two centers of different states - Rio Grande do Sul and Pernambuco - differences in prevalence rates of asthma and allergic diseases among populations inhabiting urban and rural region in these locations were confirmed( 28 ). One of the very common problems when comparing populations that inhabit rural environments is that living in a rural environment does not necessarily mean having habits of rural life. In the Amazon region, children of two islands in Belém were evaluated, one with a better standard of hygiene (Outeiro) and other located in a riparian zone (Combú), in which there is a rural lifestyle. It was found that the prevalence of asthma was significantly higher in Outeiro (30.5 versus 16.5%, respectively)( 29 ).

To be born and grow in a farm environment has been identified as a protective factor against the development of asthma and allergic diseases. However, the analysis of all data obtained with the ISAAC Phase III, regarding exposure to

farm animals during pregnancy and in the 1st year of life, documented positive association with increased symptoms of rhinoconjunctivitis, asthma and eczema in children from 6 to 7 years living in poor countries, a fact that was not observed in children living in affluent countries( 30 ). On the other hand, exposure to domestic animals such as dogs and cats, has been documented as a risk factor for the development of asthma in children of less affluent countries. In adolescents, exposure to dogs was a risk factor for asthma symptoms, worldwide( 31 ).

There is evidence that intestinal parasites, especially helminths, have a protective effect on the development of allergic diseases. In Campina Grande, Silva et al( 32 ) evaluated the prevalence of asthma in children living in a community with a low socioeconomic status and found a prevalence of 56.3% and 59.7% for ascariasis and asthma, respectively, without association between the two of them. These data were corroborated more recently by Freitas et al in Belém, while assessing children living in riparian regions( 29 ).

As the ISAAC WQ is standardized, available, and of free access, several national researchers used the protocol and increased the number of locations that had the prevalence of asthma, which were incorporated into the data centers officially recognized by ISAAC in Auckland , New Zealand. Table 2, presents the data of students from 6 to 7 years, and Table 3, the data of the adolescents( 33 - 44 ).

Table 2. Prevalence of active asthma (wheezing in the past 12 months), severe asthma (wheezing so intense able to stop to say two words in a row in the last 12 months) and asthma diagnosed by a physician in school children (6-7 years old) from official centers and other Brazilian centers that used the protocol of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) - Phase 3.

Table 3. Prevalence of active asthma (wheezing in the past 12 months), severe asthma (wheezing so intense able to stop to say two words in a row in the past 12 months) and asthma diagnosed by physician in school children (13-14 years old) of official centers and other Brazilian centers that used the protocol of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) - Phase 3.

Another controversial topic, not fully explained by the ISAAC phase I, is the influence of air pollution, especially of photochemical agents, in the prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases. In Brazilian centers West São Paulo (SPO), South São Paulo (SPS), Santo André (SA), Curitiba (CR), and Porto Alegre (PoA), where there was monitoring of gaseous pollutants - ozone (O3), carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and sulfur dioxide (SO2) -, their relationship with the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis and atopic eczema in adolescents was evaluated. The levels of O3 in SPO, SPS, and SA and of CO in SA were higher than the acceptable. Although there was not a characteristic pattern for all assessed symptoms or a specification with a given air pollutant, the data obtained suggested a relationship between greater exposure to photochemical pollutants and high prevalence or risk of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis, and atopic eczema( 45 ).

Allergic sensitization among patients identified as active asthmatic is variable. Data obtained by the ISAAC phase II in our location pointed to the prevalence of positive skin tests for immediate hypersensitivity (SPT) to aero-allergens of 13.3% in school children from the municipality of Uruguaiana, state of Rio Grande do Sul, and 5.4% were identified as having atopic asthma (wheezing in the last year with a positive skin prick test to at least one allergen) and 20.9% as having non-atopic asthma (wheezing in the last year and negative skin prick tests)( 46 ). These data are opposite to that observed by other investigators. Pastorino et al, assessing adolescents, found 46.8% of sensitization, with that by D. pteronyssinus observed in 79.1% of atopic patients. The risk of sensitization was 2.16 times higher in adolescents with asthma( 47 ). These data are consistent with those from a national study involving children and adolescents followed in specialized allergy services and evaluated by determination of specific serum IgE, verifying levels of positivity of 66.7% for D. pteronyssinus, of 64.5% for D. farinae, 55.2% for Blomia tropicalis, 32.8% for cockroach and 12% for cat( 48 ).

On the other hand, Sarinho et al, studying asthmatic and non-asthmatic adolescents from the municipality of Caruaru, state of Pernambuco, northeastern Brazil, observed a 54.0% prevalence of sensitization for asthmatics, with prevalence of sensitization to cockroach allergens( 49 ). Previous findings point to the need for local studies, with the aim of identifying the most relevant allergens and guiding more targeted therapeutic actions.

The analysis of all data from ISAAC phase III revealed that exposure to paracetamol in the 1st years of life and at present are significantly related to a higher risk of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema( 50 ), as observed by Kuschnir et al in Brazil( 51 ). In this study, multivariate analysis confirmed the association of recent and persistent use of paracetamol with increased risk of symptoms of active asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema( 50 ). Despite its widespread use in Brazil, dipyrone is the most widely used analgesic and antipyretic. Another controversial topic mentioned in several studies is the use of antibiotics in the 1st year of life. These data were examined taking all centers participating in the ISAAC phase III, including Brazil, complementing the work done with centers of phase I( 17 ). There was an association between the use of antibiotics in the 1st years of life and current symptoms of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in children from 6-7 years old. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that more research is needed to determine whether the observed associations are real, casual, indication bias or reverse causality( 52 ).

According to the initiative Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA), asthma and rhinitis should be viewed as a single disease, considering the high frequency of association between them( 53 ). Studies show rhinitis as a risk factor for asthma. Analyzing Brazilian data obtained in ISAAC Phase III in Brazilian adolescents, it was found that the association between asthma and rhinitis was high (r=0.82), as well as with rhinoconjunctivitis (r=0.75). The presence of current rhinitis and rhinoconjunctivitis was associated with increased risk of developing asthma and severe asthma( 54 ). This fact becomes more evident when atopic dermatitis is associated with rhinitis( 55 ).

The association between asthma and overweight/obesity is also increasingly common. The systemic inflammation determined by obesity, due to the production of adipokines, the triggering of symptoms during physical activity, and dietary shifts culminate into an inappropriate physical conditioning that accentuates a sedentary lifestyle, which, alone, aggravates the functional conditions of these patients. In the southern region of the country, obesity was evaluated as a risk factor for higher prevalence of asthma and related symptoms in adolescents. The analysis of nutritional parameters showed, for girls, a positive and significant relationship between the prevalence of obesity and the diagnosis of asthma, as well as severe asthma( 56 ).

A controversial topic regarding asthma in adults is its relationship with cardiovascular disease, especially hypertension. In adolescents in the municipality of Aracaju, state of Sergipe, there was a relationship between blood pressure levels and the prevalence of asthma and related symptoms; however, such association was not confirmed( 57 ).

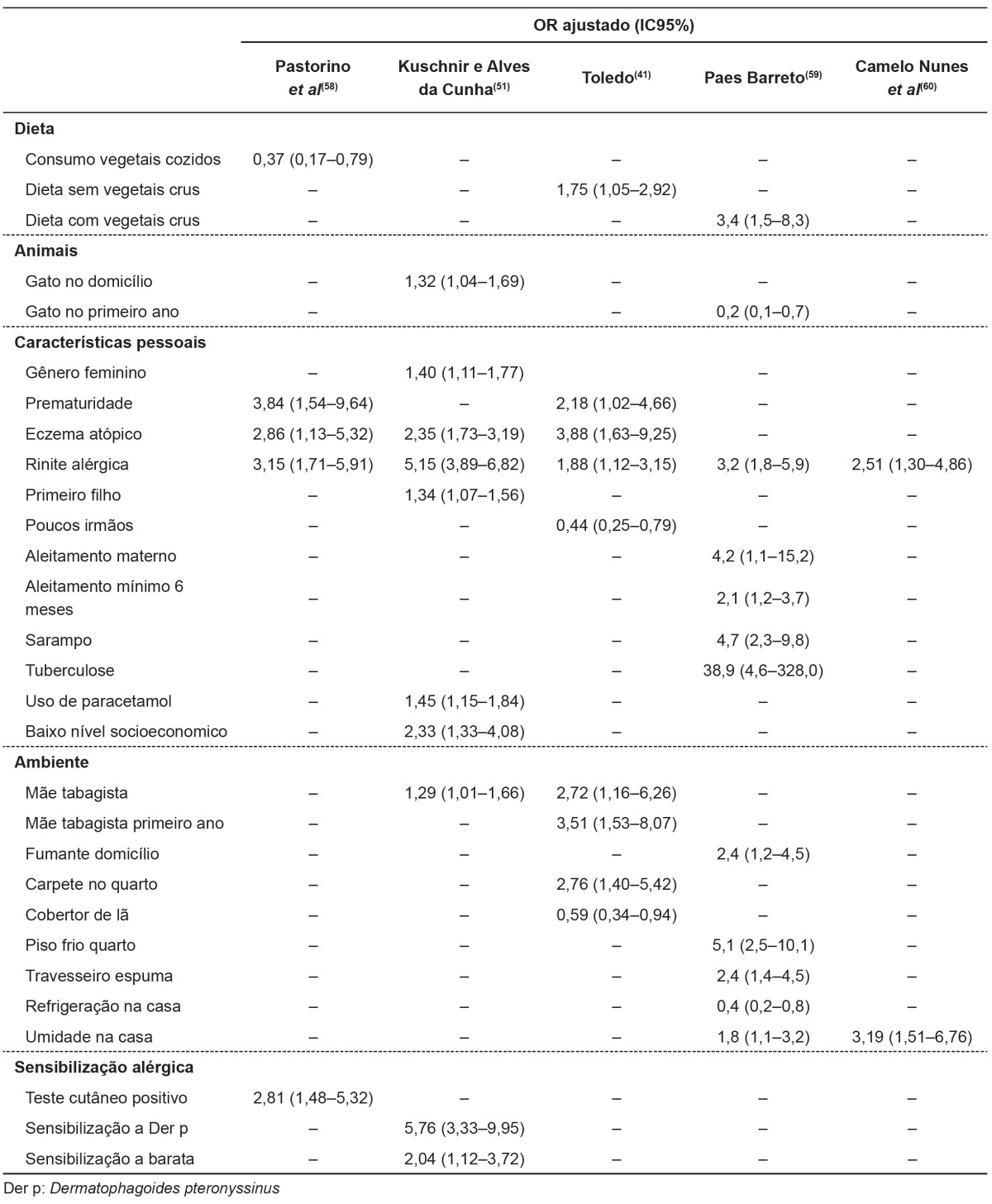

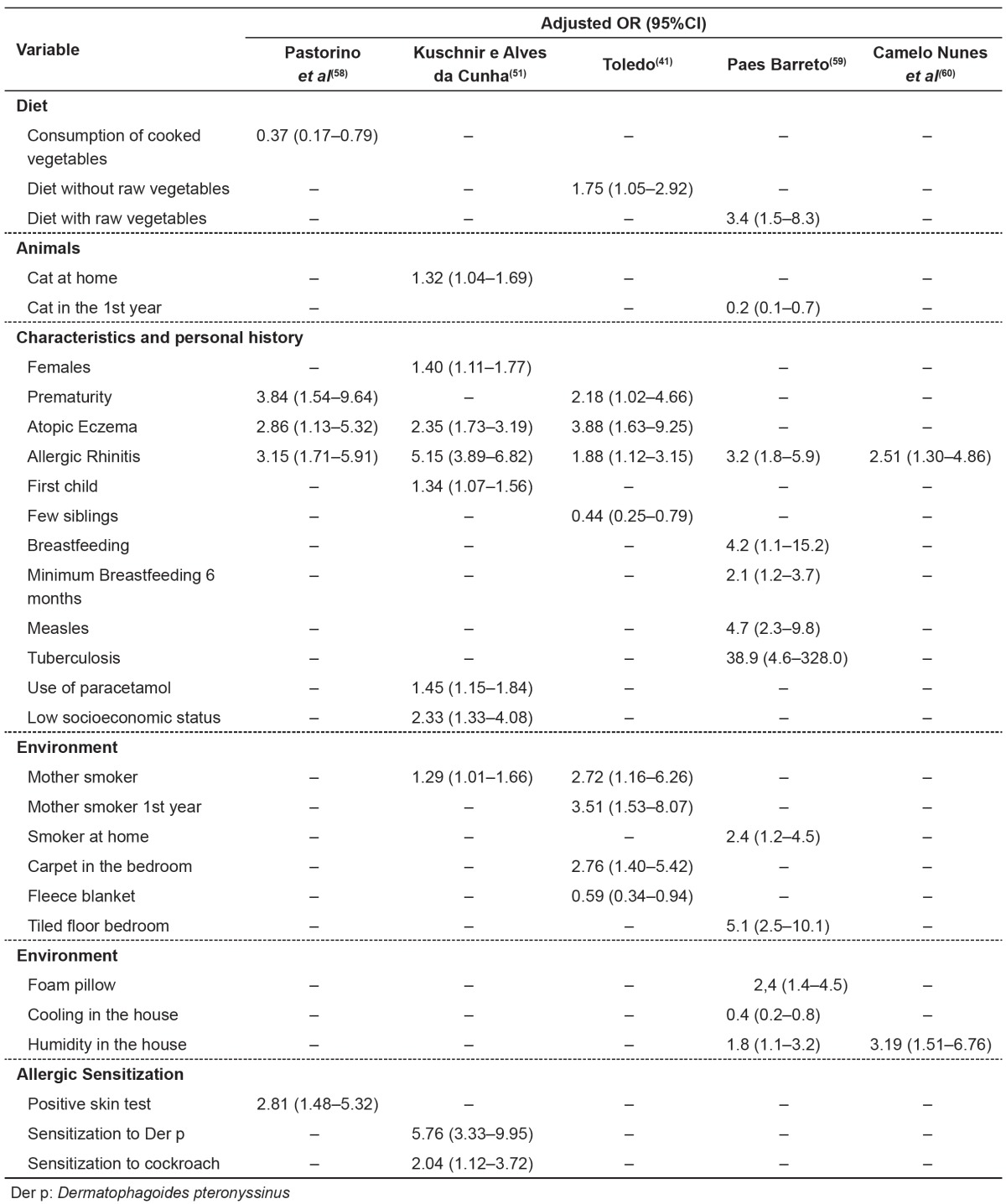

Using a similar method, the study of possible risk factors associated especially with asthma and related symptoms was

performed in some Brazilian centers, using the complementary questionnaire of the ISAAC phase II( 32 , 35 - 38 ). The risk/ protective factors( 4 , 58 - 60 ) are shown in Table 4, in which it can be verified that being preterm, having a smoker mother, living in a house with humidity, and having a history of other allergic diseases were common factors in at least two of the population samples evaluated.

Table 4. Risk/protection factors associated to asthma and related symptoms in adolescents from different Brazilian centers: logistic regression analysis.

Conclusions

The ISAAC has definitely demonstrated that asthma is a disease of high prevalence and impact in Brazilian children and adolescents, and it should be seen as a real problem of public health. In the present analysis there were important regional variations, not yet fully understood, as well as various risk factors. The serial assessments conducted by the study suggested that the prevalence of asthma is stable in Brazil, but additional measurements are needed to confirm this trend.

Despite the numerous studies performed since its inception, there is still much to investigate about asthma and allergic diseases in Brazil. The great miscegenation of the Brazilian population is certainly one of the factors that interfere with the clarity of the results and the relations between the studied variables. Do we have in Brazil, one or many asthmas?

Footnotes

Instituição: Escola Paulista de Medicina da Universidade Federal de São Paulo (Unifesp), São Paulo, SP, Brasil

References

- 1.Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, Beasley R, Crane J, Martinez F, et al. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:483–491. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08030483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solé D, Vanna AT, Yamada E, Rizzo MC, Naspitz CK. International study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC) written questionnaire: validation of the asthma component among Brazilian children. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 1998;8:376–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellwood P, Williams H, Aït-Khaled N, Björkstén B, Robertson C, ISAAC Phase III Study Group Translation of questions: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) experience. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:1174–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wandalsen NF, Gonzalez C, Wandalsen GF, Solé D. Evaluation of criteria for the diagnosis of asthma using an epidemiological questionnaire. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35:199–205. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132009000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valle SO, Kuschnir FC, Solé D, Silva MA, Silva RI, Da Cunha AJ. Validity and reproducibility of the asthma core International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) written questionnaire obtained by telephone survey. J Asthma. 2012;49:390–394. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.669440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Autoria não referida. Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee. Lancet. 1998;351:1225–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart AW, Mitchell EA, Pearce N, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, ISAAC Steering Committee International study for asthma and allergy in childhood. The relationship of per capita gross national product to the prevalence of symptoms of asthma and other atopic diseases in children (ISAAC) Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:173–179. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solé D, Yamada E, Vana AT, Werneck G, Solano de Freitas L, Sologuren MJ, et al. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): prevalence of asthma and asthma-related symptoms among Brazilian schoolchildren. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2001;11:123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prestes EX, Rozov T, Silva EM, Kopelman BI. Prevalence of asthma in 13 to 14 old school children of Belém -Pará, Brazil. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2004;22:131–136. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felizola ML, Viegas CA, Almeida M, Ferreira F, Santos MC. Prevalence of bronchial asthma and related symptoms in schoolchildren in the Federal District of Brazil: correlations with socioeconomic levels. J Bras Pneumol. 2005;31:486–491. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boechat JL, Rios JL, Sant'Anna CC, França AT. Prevalence and security of asthma symptoms in school-age children in the city of Duque de Caxias, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2005;31:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rios JL, Boechat JL, Sant'Anna CC, França AT. Atmospheric pollution and the prevalence of asthma: study among schoolchildren of 2 areas in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;92:629–634. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61428-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costa SR, Ferriani VP. Prevalence of asthma and related symptoms in children and adolescents from public and private schools an ISAAC study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:S55–S55. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee. Lancet. 1998;351:1225–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson HR, Poloniecki JD, Strachan DP, Beasley R, Björkstén B, Asher MI, et al. Immunization and symptoms of atopic disease in children: results from the International study of asthma and allergies in childhood. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1126–1129. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiland SK, Hüsing A, Strachan DP, Rzehak P, Pearce N, ISAAC Phase One Study Group Climate and the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic eczema in children. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61:609–615. doi: 10.1136/oem.2002.006809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foliaki S, Nielsen SK, Björkstén B, von Mutius E, Cheng S, Pearce N, et al. Antibiotic sales and the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis, and eczema: The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:558–563. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson HR, Ruggles R, Pandey KD, Kapetanakis V, Brunekreef B, Lai CK, et al. Ambient particulate pollution and the world-wide prevalence of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema in children: Phase One of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Occup Environ Med. 2010;67:293–300. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.048785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiland SK, Björkstén B, Brunekreef B, Cookson WO, von Mutius E, Strachan DP, et al. Phase II of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC II): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:406–412. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00090303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellwood P, Asher MI, Beasley R, Clayton TO, Stewart AW, ISAAC Steering Committee The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): phase three rationale and methods. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:10–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368:733–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solé D, Camelo-Nunes IC, Wandalsen GF, Mallozi MC, Naspitz CK, Brazilian ISAAC's Group Is the prevalence of asthma and related symptoms among Brazilian children related to socioeconomic status. J Asthma. 2008;45:19–25. doi: 10.1080/02770900701496056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellwood P, Asher MI, Stewart AW, Aït-Khaled N, Mallol J, Strachan D, et al. The challenges of replicating the methodology between Phases I and III of the ISAAC programme. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:687–693. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solé D, Melo KC, Camelo-Nunes IC, Freitas LS, Britto M, Rosário NA, et al. Changes in the prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases among Brazilian schoolchildren (13-14 years old): comparison between ISAAC Phases One and Three. J Trop Pediatr. 2007;53:13–21. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fml044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solé D, Camelo-Nunes IC, Wandalsen GF, Sarinho E, Sarinho S, Britto M, et al. Ecological correlation among prevalence of asthma symptoms, rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic eczema with notifications of tuberculosis and measles in the Brazilian population. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005;16:582–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2005.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flohr C, Nagel G, Weinmayr G, Kleiner A, Williams HC, Aït-Khaled N, et al. Tuberculosis, bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccination, and allergic disease: findings from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase Two. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:324–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franco JM, Gurgel R, Sole D, Lúcia França V, Brabin B, Brazilian Group ISAAC. Socio-environmental conditions and geographical variability of asthma prevalence in Northeast Brazil. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2009;37:116–121. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0546(09)71722-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solé D, Cassol VE, Silva AR, Teche SP, Rizzato TM, Bandim LC, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis, and atopic eczema among adolescents living in urban and rural areas in different regions of Brazil. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2007;35:248–253. doi: 10.1157/13112991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freitas MS, Monteiro JC, Camelo-Nunes IC, Solé D. Prevalence of asthma symptoms and associated factors in schoolchildren from Brazilian Amazon islands. J Asthma. 2012;49:600–605. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.692419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunekreef B, Von Mutius E, Wong GK, Odhiambo JA, Clayton TO, ISAAC Phase Three Study Group Early life exposure to farm animals and symptoms of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema: an ISAAC Phase Three Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:753–761. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brunekreef B, Von Mutius E, Wong G, Odhiambo J, García-Marcos L, Foliaki S, et al. Exposure to cats and dogs, and symptoms of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema. Epidemiology. 2012;23:742–750. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318261f040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silva MT, Andrade J, Tavares-Neto J. Asthma and ascariasis in children aged two to ten living in a low income suburb. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2003;79:227–232. doi: 10.2223/jped.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solé D, Wandalsen GF, Camelo-Nunes IC, Naspitz CK, ISAAC - Brazilian Group Prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis, and atopic eczema among Brazilian children and adolescents identified by the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) - Phase 3. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2006;82:341–346. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Col de Farias MR, Rosa AM, Hacon SS, de Castro HA, Ignotti E. Prevalence of asthma in schoolchildren in Alta Floresta - a municipality in the southeast of the Brazilian Amazon. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2010;13:49–57. doi: 10.1590/s1415-790x2010000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menin AM. Prevalência e gravidade dos sintomas de asma, rinite e eczema, em escolares de 6 a 7 anos, na cidade de São José do Rio Preto, SP, avaliados pelo ISAAC . Ribeirão Preto, SP: USP; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castro LK, Cerci A, Neto, Ferreira OF., Filho Prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis and atopic eczema among students between 6 and 7 years of age in the city of Londrina, Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2010;36:286–292. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132010000300004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lima WL, Lima EV, Costa Mdo R, Santos AM, Silva AA, Costa ES. Asthma and associated factors in students 13 and 14 years of age in São Luís, Maranhão State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2012;28:1046–1056. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2012000600004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luna MF, Almeida PC, Silva MG. Asthma and rhinitis prevalence and comorbidity in 13-14-year-old schoolchildren in the city of Fortaleza, Ceará State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2011;27:103–112. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2011000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jucá SC, Takano OA, Moraes LS, Guimarães LV. Asthma prevalence and risk factors in adolescents 13 to 14 years of age in Cuiabá, Mato Grosso State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2012;28:689–697. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2012000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toledo MF, Rozov T, Leone C. Prevalence of asthma and allergies in 13to 14-year-old adolescents and the frequency of risk factors in carriers of current asthma in Taubaté, São Paulo, Brazil. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2011;39:284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Toledo EC. Prevalência e fatores de risco associados à asma em adolescentes residentes em São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo . São José do Rio Preto, SP: Famerp; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maia JG, Marcopito LF, Amaral AN, Tavares BF, Lima e Santos FA. Prevalence of asthma and asthma symptoms among 13 and 14-year-old schoolchildren, Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2004;38:292–299. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102004000200020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Magalhães EF, Toporovski MS, Solé D, Kiertsman B. Prevalence and risk factors for asthma in adolescents of a town from the south part of the State of Minas Gerais. Arq Med Hosp Fac Cienc Med Santa Casa São Paulo. 2011;56:12–18. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Breda D, Freitas PF, Pizzichini E, Agostinho FR, Pizzichini MM. Prevalence of asthma symptoms and risk factors among adolescents in Tubarão and Capivari de Baixo, Santa Catarina state, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25:2497–2506. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009001100019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Solé D, Camelo-Nunes IC, Wandalsen GF, Pastorino AC, Jacob CM, Gonzalez C, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis, and atopic eczema in Brazilian adolescents related to exposure to gaseous air pollutants and socioeconomic status. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2007;17:6–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weinmayr G, Weiland SK, Björkstén B, Brunekreef B, Büchele G, Cookson WO, et al. Atopic sensitization and the international variation of asthma symptom prevalence in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:565–574. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-994OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pastorino AC, Kuschnir FC, Arruda LK, Casagrande RR, de Souza RG, Dias GA, et al. Sensitisation to aeroallergens in Brazilian adolescents living at the periphery of large subtropical urban centres. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2008;36:9–16. doi: 10.1157/13115665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naspitz CK, Solé D, Jacob CA, Sarinho E, Soares FJ, Dantas V, et al. Sensitization to inhalant and food allergens in Brazilian atopic children by in vitro total and specific IgE assay. Allergy Project - PROAL. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2004;80:203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarinho EC, Mariano J, Sarinho SW, Medeiros D, Rizzo JA, Almerinda RS, et al. Sensitisation to aeroallergens among asthmatic and non-asthmatic adolescents living in a poor region in the Northeast of Brazil. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2009;37:239–243. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beasley RW, Clayton TO, Crane J, Lai CK, Montefort SR, Mutius E, et al. Acetaminophen use and risk of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in adolescents: International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase Three. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:171–178. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201005-0757OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuschnir FC, Alves da Cunha AJ. Environmental and socio-demographic factors associated to asthma in adolescents in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007;18:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2006.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Foliaki S, Pearce N, Björkstén B, Mallol J, Montefort S, von Mutius E, et al. Antibiotic use in infancy and symptoms of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in children 6 and 7 years old: International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase III. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:982–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brozek JL, Bousquet J, Baena-Cagnani CE, Bonini S, Canonica GW, Casale TB, et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines: 2010 revision. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:466–476. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Solé D, Camelo-Nunes IC, Wandalsen GF, Rosário NA, Sarinho EC, Brazilian Group ISAAC. Is allergic rhinitis a trivial disease. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:1573–1577. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000900012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Solé D, Camelo-Nunes IC, Wandalsen GF, Melo KC, Naspitz CK. Is rhinitis alone or associated with atopic eczema a risk factor for severe asthma in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005;16:121–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2005.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cassol VE, Rizzato TM, Teche SP, Basso DF, Centenaro DF, Maldonado M, et al. Obesity and its relationship with asthma prevalence and severity in adolescents from southern Brazil. J Asthma. 2006;43:57–60. doi: 10.1080/02770900500448597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roelofs R, Gurgel RQ, Wendte J, Polderman J, Barreto-Filho JA, Solé D, et al. Relationship between asthma and high blood pressure among adolescents in Aracaju, Brazil. J Asthma. 2010;47:639–643. doi: 10.3109/02770901003734306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pastorino AC, Rimazza RD, Leone C, Castro AP, Solé D, Jacob CM. Risk factors for asthma in adolescents in a large urban region of Brazil. J Asthma. 2006;43:695–700. doi: 10.1080/02770900600925544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paes Barreto BA. Prevalência e fatores de risco para asma e doenças alérgicas em adolescentes moradores de Belém, Pará. São Paulo, SP: Unifesp; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Camelo Nunes IC, Yamada R, Pimentel LG, Sano F, Solé D, Naspitz CK. Prevalence and risk factors for asthma in Brazilian and Japanese schoolchildren living in the city of São Paulo Brazil. Abstracts of the XXI World Allergy Congress; São Paulo: 120-Dec. 2009. [Google Scholar]