Abstract

Lysine acetylation regulates many eukaryotic cellular processes, but its function in prokaryotes is largely unknown. We demonstrated that central metabolism enzymes in Salmonella were acetylated extensively and differentially in response to different carbon sources, concomitantly with changes in cell growth and metabolic flux. The relative activities of key enzymes controlling the direction of glycolysis versus gluconeogenesis and the branching between citrate cycle and glyoxylate bypass were all regulated by acetylation. This modulation is mainly controlled by a pair of lysine acetyltransferase and deacetylase, whose expressions are coordinated with growth status. Reversible acetylation of metabolic enzymes ensure that cells respond environmental changes via promptly sensing cellular energy status and flexibly altering reaction rates or directions. It represents a metabolic regulatory mechanism conserved from bacteria to mammals.

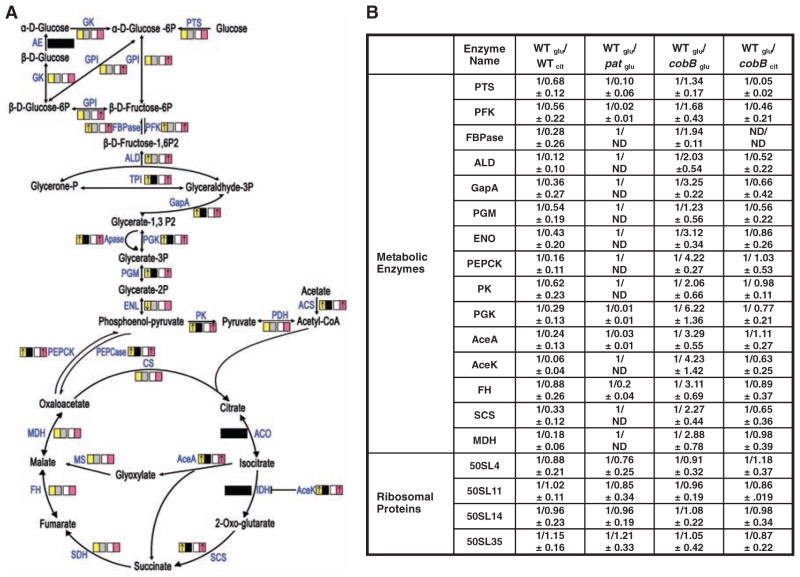

Protein lysine acetylation regulates wide range of cellular functions in eukaryotes, especially transcriptional control in the nucleus (1, 2). It also plays an extensive role in regulation of metabolic enzymes through various mechanisms in human liver (3). In prokaryotes such as Salmonella enterica, reversible lysine acetylation is known to regulate the activity of acetyl–coenzyme A (CoA) synthetase (4). To determine how lysine acetylation globally regulates the metabolism in prokaryotes, we determined the overall acetylation status of S. enterica proteins under either fermentable glucose-based glycolysis or under oxidative citrate-based gluconeogenesis. By immunopurification of acetylated peptides with antibody to acetyllysine and peptide identification by mass spectrometry analyses, we identified a total of 235 acetylated peptides that matched to 191 proteins in S. enterica. About 50% of the acetylated proteins participated in multiple metabolic pathways (tables S1 and S2), and about 90% of the enzymes of central metabolism were acetylated (Fig. 1A). Stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) quantitative analysis showed that, among 15 enzymes that had altered acetylation in response to different carbon sources, all showed greater acetylation in cells grown in glucose than in cells grown in citrate (Fig. 1B), consistent with our estimations based on numbers of repetitive detection of acetylated fragments (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Acetylation of central metabolic enzymes in S. enterica. (A) Global acetylation of S. enterica enzymes of central metabolism. Colored boxes represent both genetic and growth status with arrows inside to indicate changes in acetylation estimated by counting number of positive hits from MS analyses. Comparisons were made for wild-type (WT) cells grown with either glucose (red box) or citrate (white) as the sole carbon source, and for WT cells (yellow) and Δpat (gray), both grown on LB. Black boxes indicate that acetylated peptide was not detected. (B) SILAC quantification of relative acetylation. Acetylation of WT cells grown with glucose (WTglu) or citrate (WTcit), Δpat grown with glucose (patglu), and ΔcobB grown with glucose (cobBglu) or citrate (cobB cit) were quantified by SILAC. Relative acetylation is presented with the top mean value (n = 3) of each pair set as 1 arbitrarily. ND indicates not detectable. Full names of abbreviations used in this figure are available in supporting online material (SOM) text.

The abundant acetylation of metabolic enzymes and the concerted changes in acetylation dependent on carbon source indicate that acetylation may mediate adaptation to various carbon sources in S. enterica, which has only one major bacterial protein acetyltransferase, Pat, and one nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)–dependent deacetylase, CobB (4, 5) (fig. S1). Acetylation of central metabolic enzymes in a pat null mutant (Δpat) was reduced, whereas acetylation of these enzymes was elevated in a cobB null mutant (ΔcobB) compared with that of the wild-type strain when grown in glucose (Fig. 1B). When grown in citrate, the acetylation of metabolic enzymes in ΔcobB cells was also increased over the wild-type cells (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, there was no change in acetylation of ribosomal proteins in either ΔcobB or Δpat cells (Fig. 1B), supporting the notion that Pat and CobB are the major enzymes responsible for the reversible acetylation of central metabolic enzymes in S. enterica.

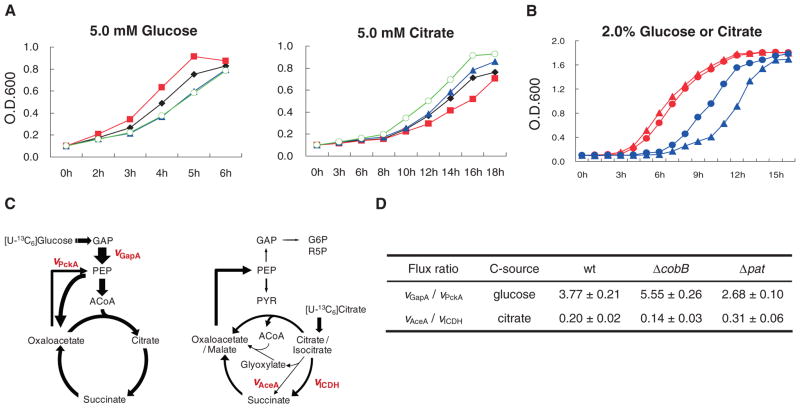

A physiological role of enzyme acetylation in mediating cellular adaptation to different metabolic fuels was suggested by the different growth properties of wild-type, Δpat, or ΔcobB strains grown on different carbon sources (Fig. 2). The ΔcobB cells (with increased acetylation) grew faster than wild-type cells in minimal glucose medium but grew slower than wild-type cells in minimal citrate medium (Fig. 2A), whereas the Δpat cells (with decreased acetylation) had the opposite growth properties (Fig. 2A). The Δpat/ΔcobB double mutant behaved similarly to the Δpat strain, consistent with the notion that the CobB deacetylase would have no effect on target proteins if they were not acetylated by Pat (Fig. 2A). Treatment of wild-type cells with nicotinamide (NAM), an inhibitor for CobB (6), like cobB mutation, suppressed cell growth in the citrate-containing minimal medium but had little effect on cell growth in minimal medium containing glucose (Fig. 2B), consistent with the fact that metabolic enzyme acetylation is higher in S. enterica when cells grow on glucose (Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

Growth phenotypes of Δpat and ΔcobB. (A) WT (black), Δpat (blue), ΔcobB (red), or Δpat/ΔcobB (green) strains were grown in minimal medium with indicated concentrations of glucose (left) or citrate (right). O.D. indicates optical density. (B) Growth curves of WT S. enterica in minimal medium containing glucose (red) or citrate (blue) with (▲) or without (●) NAD+. (C) In vivo metabolic flux profiles in S. enterica during growth on glucose or citrate. Intracellular flux distribution was determined by 13C labeling and GC-MS analysis. Arrows indicate the direction of net fluxes, and their widths are scaled to the flux values. (D) Altered metabolic flux ratio of Δpat and ΔcobB. Flux profiles through glycolysis (represented by vGapA), gluconeogenesis (vPckA), glyoxylate bypass (vAceA), and TCA flux (vICDH) were quantitated and used for calculating vGapA/vPckA and vAceA/vICDH flux ratio. Data shown are mean values of three independent measurements with SD.

We tested the regulatory role of Pat and CobB in coordinating carbon source adaptation by measuring in vivo metabolic flux profiles with 13C-labeled glucose or citrate as the tracer followed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis (7, 8). The overall metabolic flux profiles in S. enterica showed distinct patterns during growth on glucose or citrate (Fig. 2C). The glyoxylate bypass was activated, and the carbon flow favored gluconeogenesis when cells were grown on citrate. We also quantitatively compared the flux profiles through glycolysis (vGapA), gluconeogenesis (vPckA), tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (vICDH), and glyoxylate bypass (vAceA) of the wild-type, Δpat, and ΔcobB strains to assess the relation between metabolic flux profiles and acetylation status. When cells were grown in the presence of glucose, the ΔcobB strain had 2.07-fold greater glycolysis/gluconeogenesis flux ratio than the Δpat strain had (Fig. 2D), whereas the glycolysis/gluconeogenesis flux ratio of the wild-type strain was 47% lower than that of the ΔcobB strain but 40.7% higher than that of the Δpat strain (Fig. 2D). When cells were grown in the presence of citrate, the Δpat strain had 2.21-fold greater glyoxylate bypass/TCA flux ratio than that of the ΔcobB strain (Fig. 2D), whereas the glyoxylate/TCA flux ratio of the wild-type strain was 55% lower than that of the Δpat strain but 43% higher than that of the ΔcobB strain (Fig. 2D). These results and the effect of glucose on acetylation of metabolic enzymes (Fig. 1) indicate that carbon source–associated acetylation may affect the relative activities of metabolic enzymes and thus modulate metabolic flux profiles.

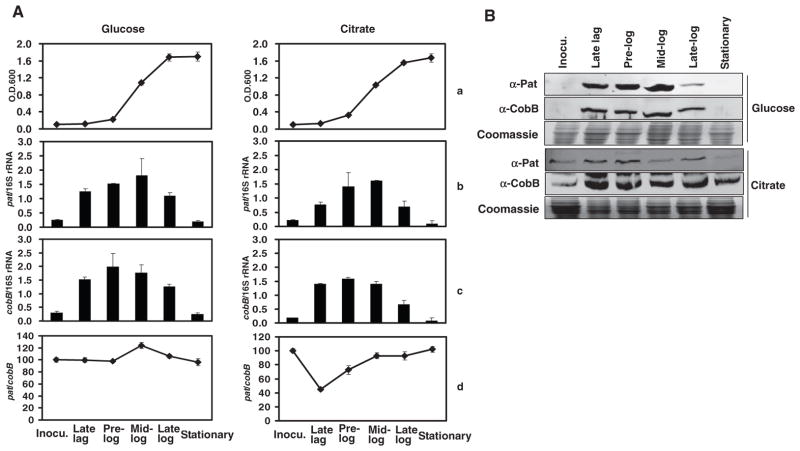

Direct evidence of acetylation-mediated regulation for central metabolic enzymes was derived from biochemical studies with three enzymes (table S1): the glyceraldehyde phosphate de-hydrogenase (GapA), which channels glycolysis or gluconeogenesis flux bidirectionally, as well as the isocitrate lyase (AceA) and the isocitrate dehydrogenase (ICDH) kinase/phosphatase (AceK), both of which control the flux distribution of isocitrate between the energy-generating TCA cycle and the gluconeogenesis-requiring glyoxylate pathway when only an oxidative carbon source (such as citrate) is available (9). Anti-acetylysine immunoblot showed that all three enzymes had increased acetylation in the ΔcobB strain (Fig. 3A). Acetylation of these three enzymes decreased to various degrees in the Δpat strain. The remaining acetylation detected in the Δpat strain may reflect the presence of other acetyltransferases (fig. S1). All these enzymes were more heavily acetylated in cells grown in minimal media with glucose than those grown with citrate (fig. S4). These observations confirmed that GapA, AceA, and AceK are under regulation of Pat and CobB.

Fig. 3.

Regulation of central metabolic enzymes by acetylation. (A) Acetylation of metabolic enzymes expressed in ΔcobB and Δpat strains. His-tagged GapA, AceA, or AceK proteins were over-expressed in the WT, ΔcobB, and Δpat strains and purified to homogeneity. Equal amounts of each protein were used and acetylation was determined. SDS PAGE indicates SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. (B and C) GapA, AceA, and AceK activities by Pat-mediated acetylation and CobB-mediated deacetylation. His-tagged GapA, AceA, and AceK proteins were purified from WT S. enterica and subjected to in vitro acetylation by Pat or deacetylation by CobB. (B) Reciprocal regulation of glycolytic and gluconeogenic activities of GapA by Pat and CobB. (C) Reciprocal regulation of AceA activity and AceK-controlled ICDH activities by Pat and CobB in vitro. Error bars indicate SD of three measurements.

To demonstrate a direct effect of acetylation on enzyme activity, we purified recombinant Pat and CobB protein and treated GapA, AceK, and AceA enzymes in vitro (fig. S2). Increasing GapA acetylation by Pat acetylase treatment increased its glycolysis activity by 100%, whereas its activity in promoting gluconeogenesis was inhibited by more than 30% (Fig. 3B), supporting the notion that acetylation stimulates glycolysis but inhibits gluconeogenesis. Consistently, in vitro deacetylation of GapA by CobB caused a 30% increase in gluconeogenic activity but a 27% decrease in glycolytic activity (Fig. 3B). The increase of AceA acetylation by in vitro treatment with Pat (Fig. 3C) or acetylation-mimicked mutation (fig. S3) led to 30% and 20% loss in AceA-specific activity, respectively. In vitro deacetylation of AceA by CobB, on the other hand, led to a 24% increase in AceA-specific activity (Fig. 3C). The activity of AceK was measured by its ability to inactivate its native substrate, ICDH, which catalyzes the conversion of isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate. In vitro acetylation of AceK by Pat led to a 60% reduction of its ability to inactivate ICDH (by phosphorylating ICDH), whereas in vitro deacetylation of AceK by CobB increased AceK’s ability to inactivate ICDH (Fig. 3C), suggesting that acetylation may activate the phosphatase activity of AceK toward ICDH, consistent with the fact that both acetylation and the acetylation mimetic mutation of AceK activated the phosphorylated ICDH (figs. S4 and S5). Together, these results demonstrate that activities of GapA, AceA, and AceK enzymes are regulated through acetylation, which in turn may direct the flux direction toward glycolysis or gluconeogenesis or the distribution of isocitrate between the TCA cycle and glyoxylate bypass.

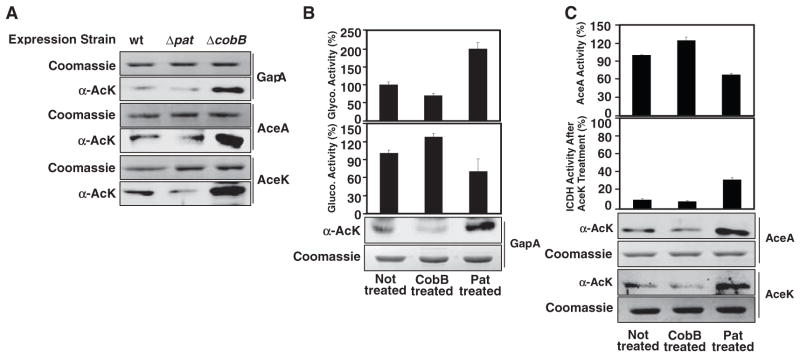

We also investigated the expression of pat and cobB genes in cells grown on different carbon sources. Real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis, using 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) as the internal control, revealed that both pat and cobB genes were more actively transcribed during log phase growth than other growth phases when cells were grown in the presence of either glucose or citrate (Fig. 4A). Accordingly, the concentrations of Pat and CobB proteins were increased (fig. S6 and Fig. 4B). During the stationary phase, cells that grew in the presence of either glucose or citrate had similar ratios of pat mRNA/cobB mRNA. However, when rich medium–incubated cells were transferred to minimal medium containing glucose, acetylation peaked at mid-log phase (Fig. 4A), whereas if they were transferred to minimal medium containing citrate, acetylation decreased in both prelog and early log phases before it returned to basal level in late log and stationary phases (Fig. 4A). The lower amount of cellular acetylation was apparently needed for efficient utilization of citrate. These results indicate that the expression (and probably total cellular activities) of Pat and CobB are regulated differentially in response to different carbon sources, although its underlying mechanism is yet to be revealed.

Fig. 4.

Differential transcription of pat and cobB in response to metabolic status and various carbon sources. S. enterica cells were incubated in LB and then washed and transferred into minimal medium containing 50 mM glucose or citrate. Cells were sampled at indicated growth phases. (A) Growth curve (a); pat and cobB mRNA amounts normalized against 16S rRNA (b and c); ratio of pat mRNA/cobB mRNA (d). (B) Changes of Pat and CobB protein concentrations at different growth phases in glucose- or citrate-containing medium.

The central metabolic pathways constitute the backbone of cell metabolism. Such pathways use various carbon sources to provide building blocks, cofactors, and energy for cell growth. For cells to respond flexibly and promptly to availability of environmental carbon sources, the directions and/or rates of the metabolic reactions need to be modulated concomitantly and globally. Transcription regulations merely adjust the amount of metabolic enzymes in a unidirectional manner, whereas allosteric effects only modulate the catalytic activities of individual enzymes responsible for specific reactions of metabolic pathways (10). We have found a potential regulatory circuit coordinating the carbon flow of S. enterica central metabolism by reversible acetylation. Acetylation uses acetyl-CoA and NAD+, two molecules that directly involved both in metabolism and energy sensing, as substrates, provides unparallel advantages in sensing cellular energy status, and thus could fit the role for global metabolic modulation. The identification of extensively acetylated metabolic enzymes in both human and prokaryotes and reports of broad metabolic regulatory roles of this modification (11–16) indicate that reversible lysine acetylation may represent an evolutionarily conserved mechanism of metabolic regulation in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of Fudan Molecular Cell Biology laboratory for their inputs throughout this work. L. Wang of Nankai University, China, provided the S. Enterica G2466 for this study. This work is supported by state key development programs of basic research of China (2009CB918401 and 2006CB806700), national high technology research and development program of China (2006AA02A308), National Natural Science Foundation of China (30830002), and Shanghai key basic research project, China (08JC1400900).

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Grunstein M. Nature. 1997;389:349. doi: 10.1038/38664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang XJ, Seto E. Oncogene. 2007;26:5310. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao S, et al. Science. 2010;327:1000. doi: 10.1126/science.1179689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Starai VJ, Celic I, Cole RN, Boeke JD, Escalante-Semerena JC. Science. 2002;298:2390. doi: 10.1126/science.1077650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starai VJ, Escalante-Semerena JC. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:1005. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bitterman KJ, Anderson RM, Cohen HY, Latorre-Esteves M, Sinclair DA. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205670200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hua Q, Yang C, Baba T, Mori H, Shimizu K. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:7053. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.24.7053-7067.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zamboni N, Fischer E, Sauer U. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:209. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cozzone AJ. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:127. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neidhardt FC. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. 2. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J, et al. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:215. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800187-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choudhary C, et al. Science. 2009;325:834. doi: 10.1126/science.1175371. published online 16 July 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin YY, et al. Cell. 2009;136:1073. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bereshchenko OR, Gu W, Dalla-Favera R. Nat Genet. 2002;32:606. doi: 10.1038/ng1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landry J, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110148297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallows WC, Lee S, Denu JM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604392103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.