Abstract

Purpose

Hispanic women living on the US-México border experience health disparities, are less likely to access cervical cancer screening services, and have a higher rate of cervical cancer incidence compared to women living in non-border areas. Here we investigate the effects of an intervention delivered by community health workers (CHWs, known as lay health educators or Promotores de Salud in Spanish) on rates of cervical cancer screening in Hispanic women who were out of compliance with recommended screening guidelines.

Methods

Hispanic women out of compliance with screening guidelines, attending clinics in southern New México (NM), were identified using medical record review. All eligible women were offered the intervention. The study was conducted between 2009 and 2011, and data were analyzed in 2012. Setting/participants - 162 Hispanic women, resident in NM border counties, aged 29-80 years, who had not had a Pap test within the past 3 years. Intervention - A CHW-led, culturally appropriate, computerized education intervention. Main outcome measures - The percentage of women who underwent cervical cancer screening within 12 months of receiving the intervention. Change in knowledge of, and attitudes towards cervical cancer and screening as assessed by a baseline and follow-up questionnaire.

Results

76.5% of women had a Pap test after the intervention. Women displayed increased knowledge about cervical cancer screening and about HPV.

Conclusions

A culturally appropriate promotora-led intervention is successful in increasing cervical cancer screening in at-risk Hispanic women on the US-México border.

Keywords: cervical cancer screening, community health workers, education intervention, health disparities, health promotion

The United States-México border region includes parts of 4 US states (including 44 counties) and 6 Mexican states (including 80 municipios) that lie within 100 kilometers north or south of the US-México border. The population of this area is estimated to be approximately 13 million, and it is expected to double by the year 2025.1 In 2010, the United States-México Border Health Commission identified the region as rapidly growing, with a young population, where 52% of the population is Hispanic. The population is characterized by lower educational attainment, lower income status, and higher poverty rates, with poverty almost twice as high in this region compared to the US as a whole.1 The region also has higher rates of uninsured people: In 2007, 23% of border residents lacked health insurance coverage, compared to 14.7% nationally, and the region has an inadequate number of health care providers. All of these issues contribute to diminished health, well-being, and access to health care. Health disparities are predicted to worsen in this region.2,3

Barriers to receiving needed health care can include cost, language or knowledge barriers, and structural or logistical factors, such as long waiting times and not having transportation.4 Barriers to care contribute to socioeconomic, racial and ethnic, and geographic differences in health care utilization and health status. Women are more likely than men to live in poverty, and Hispanic women are more than twice as likely to be living in poverty than non-Hispanic white women (23.8% vs. 10.1%),5 and they are more likely to be uninsured and to experience health disparities. Women were more likely than men to report having delayed care due to logistical barriers in the past year (13.0% vs. 9.6%, respectively). Unmet needs for health care also varied by race and ethnicity. Eleven to twelve percent of Hispanic and non-Hispanic black women had an unmet need for health care due to cost, compared to 8.5% of non-Hispanic whites.5

Hispanic women in the US have the highest cervical cancer incidence with an age-adjusted incidence of 12.5 cases/100,000 women for 2004-2008, compared to an incidence of 7.0 in the non-Hispanic white population.6 With an age-adjusted incidence rate of 9.7/100,000 women for 1998-2003, the US border region exhibits a higher incidence of cervical cancer than non-border counties in border states (9.3/100,000, all counties combined), or non-border states overall (8.7/100,000).7 In addition, rates of cervical cancer diagnosed at a late stage were higher in border counties and in other counties in border states, as compared with the rates for non-border states.7 While the US Preventative Task Force guidelines for Pap testing are every 3 years for routine screening by women over the age of 21, or from 3 years after the age of initiation of sexual activity, whichever is earlier,8 Hispanic women are less likely than non-Hispanic whites to have a Pap test. Data from the National Health Interview Survey show that 74.6% of Hispanic women had a Pap test in the past 3 years compared to 81.4% of non-Hispanic white women.9 Similarly, Hispanic non-adherence with recommended follow-up has been reported in several regional studies to range from 20%to 90%,10,11 and women living in the US border region report lower rates of recent screening than other US women.7 Thus low-cost, easily adaptable interventions to increase Pap test screening in vulnerable populations are needed.

Successful programs aimed at increasing cancer screening behaviors for Hispanic women have used a variety of methods including Spanish-language media, health fairs and community health workers (CHWs, known as lay health educators or Promotores de Salud in Spanish),12 where CHWs educate community peers in a culturally appropriate manner.13 Systematic reviews have identified one-on-one education as an effective method to increase cervical cancer screening.14 Pap test self-efficacy, perceived benefits of having a Pap test, subjective norms, and perceived survivability of cancer have significantly increased when CHWs were involved in interventions to motivate Hispanic women aged ≥50 years, and living in the border region to receive a Pap test.15 However, a limited number of studies have tested interventions using CHWs in the border region, an area where Hispanic women experience significant barriers to care.12,16

In this paper, we describe the effect of a CHW-led tailored, culturally appropriate (as ascertained by focus groups of border women) computerized educational intervention, aimed at increasing uptake of cervical screening (Papanicolaou (Pap) tests) in Hispanic women on the US-México border who were non-compliant with recommended Pap test guidelines (3 years or more since a Pap test).

METHODS

Setting

A health clinic system in southern New Mexico (NM), which serves border communities, participated in this study. The border communities were in the southern part of Doña Ana county in New Mexico; the southern part of the county is designated as a rural area by the US Census Bureau. Data were collected between 2009 and 2011 and were analyzed in 2012.

Participant Recruitment

Eligibility criteria were that the participant be female, Hispanic, non-compliant with Pap screening (did not have a Pap test in the past 3 years), and able to complete a verbally administered questionnaire. Systematic medical record review identified 200 Hispanic women who had not had a Pap test for 3 or more years, and who were residents of NM. Medical record review was carried out by the clinic under the direction of author Vilchis. Of the Hispanic women listed, 198 women were successfully contacted to take part in the study. Two women were unreachable. At baseline, 34 women reported that they had a Pap test within the last 3 years. They received the intervention, but their data were not included in the analysis. Two participants were excluded from the analysis as they had incomplete data. The final study sample size for this paper is 162 women. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was approved by both the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC) and the New Mexico State University (NMSU) Institutional Review Boards.

Intervention

It was important for this study to develop an intervention that was culturally appropriate for the Hispanic population. A culturally appropriate intervention is one that meets the needs of a specific population group as opposed to other population groups. We conducted 3 focus groups with Hispanic women to ensure that the content of the intervention as well as the barriers addressed were consistent with Latino culture.

Three CHWs were recruited from the clinic system and were trained to deliver the intervention, and administer both a baseline and final survey. An educational intervention was developed by the researchers at FHCRC and NMSU. The curriculum was developed using the principles of intervention mapping.17 Intervention mapping is a strategy for developing an intervention based on theoretical and empirical needs. It uses an iterative process for identifying the components of an intervention that will be best suited to the population and health behavior being addressed. The intervention materials included a PowerPoint presentation that illustrated and described Pap screening, Pap results, cervical cancer, and the human papillomavirus (HPV). Colorful pictures and a video of a Pap test were included in the PowerPoint presentation. The presentation was translated to Spanish by a native speaker. Following development, the intervention was given to a focus group of Hispanic border women (N=6) who responded to the cultural relevance of the intervention. Their suggestions were integrated into the intervention.

The CHWs also encouraged women to obtain cervical screening and facilitated the women in making an appointment. They were trained by 2 of the scientific team (BT and HV). A training handbook included baseline and follow-up questionnaires in English and Spanish and the PowerPoint presentation. A 3-day training period included training in knowledge of cervical cancer and screening, role playing, and practice in delivering the intervention. A booster training session was held some 6 months later (by HV) to refresh the CHWs in the intervention and questionnaire administration.

Intervention presentations, as well as the questionnaires, were conducted in English or Spanish depending on the wishes of the participant. The trained CHW approached women on the non-compliant list at their homes and assessed eligibility and interest. They obtained informed consent from interested participants, and they administered a baseline survey. The survey was developed by the investigators and included both validated and original questions. The survey was translated into Spanish and pre-tested in a pilot group of Hispanic border women. The survey consisted of 50 close-ended questions, including questions on prior knowledge of Pap tests, experience with Pap tests, attitudes toward Pap test, attitudes and beliefs about HPV and the HPV vaccine, and sociodemographic questions. The latter assessed age, health insurance coverage, educational level, years lived in the US, and country of birth. The CHWs then delivered the intervention (a PowerPoint presentation) and the final questionnaire was administered immediately after the intervention. At that point, the CHW answered any questions that the woman may have had, encouraged the woman to receive a Pap test, and offered to assist her in making an appointment.

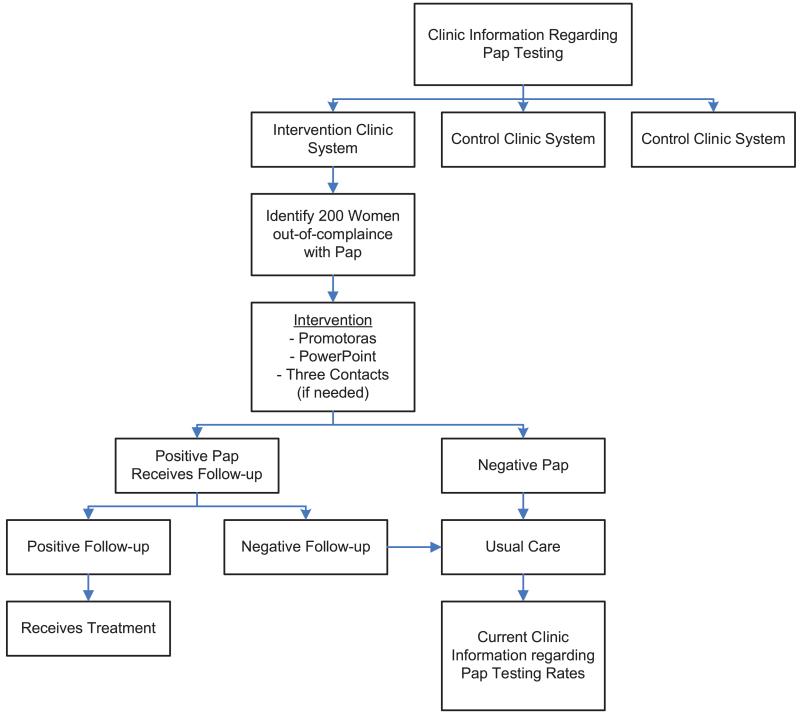

Special clinic hours were offered to accommodate the participant in keeping her appointment for Pap screenings. Women who had an abnormal Pap test (N = 5) were encouraged by CHWs to receive a follow-up Pap test (N=5), a colposcopy, or treatment (N = 1), while a normal Pap result ended the study for that particular participant. The participant was encouraged to have regular Pap tests in the future (Figure 1). The intervention period was 12 months, with women expected to receive a Pap test within 6 months of intervention.

Figure 1.

Study Design

Statistical Analysis

We categorized the following variables: years resident in the US (≤ 5; >5 and ≤ 10; >10 years); last year of schooling completed (0-12 and >12 years); time since last Pap test (<3 years ago; 3 years ago; >3 and ≤5 years ago; >5 and ≤10 years ago; never had a Pap test; don’t know; and had a Pap but don’t remember when). We tested for baseline differences in categorical variables between participants who went on to have a Pap test, vs those that did not using the Fisher’s exact test. We used McNemar’s test with matched pairs of subjects to determine whether row and column marginal frequencies were equal in responses to questions administered pre- and post-intervention. As this test is dichotomous, we re-coded responses “Agree” and “Strongly Agree” together, and “Disagree” and “Strongly Disagree” together. All P values are 2-sided. Analyses were performed using STATA 11 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). The primary outcome was the percentage of women who had a Pap test within 1 year of receiving the intervention, as identified by medical record review.

RESULTS

The mean age of participants was 45.3 years (Table 1), and they were predominantly Spanish speakers (90.0%). The majority of participants received fewer than 12 years of education (93.2%), were non-smokers (69.7%), and had been born in México (88.3%). Finally 87.6% of participants had no health insurance at baseline. The rate of prior Pap testing was high, with 97.5% of women reporting that they ever had a Pap test. The principal reasons for not having a Pap test within the past 3 years included “I kept putting it off” (27.2%) and “Too expensive/No insurance” (21.6%). A further 29 participants reported 2 more reasons for non-compliance: “I kept putting it off” (N=5), “Too expensive” (N=14), “No insurance” (N=5), “Too embarrassing” (N=3), and “Afraid of results” (N=2). A further 19 of these 29 reported a third reason: “Too expensive” (N=2), “No insurance” (N=16), and “Too painful/unpleasant” (N=1). Finally, 3 participants gave a fourth reason: “No insurance” (N=2) and “Too painful/unpleasant” (N=1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics (N=162).

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 45.3 (9.2) |

|

| |

| Language | |

| Both | 1 (0.6%) |

| English | 15 (9.4%) |

| Spanish | 144 (90.0%) |

|

| |

| Education | |

| < 12 years of education | 150 (93.2%) |

| >12 years of education | 11 (6.8%) |

|

| |

| Country of Birth | |

| México | 143 (88.3%) |

| U.S. | 19 (11.7%) |

|

| |

| Smoking History | |

| Ever | 49 (30.3%) |

| Never | 113 (69.7%) |

|

| |

| Health Insurance | |

| Yes | 10 (6.2%) |

| No | 141 (87.6%) |

| Don’t Know | 7 (4.4%) |

| Refused | 3 (1.9%) |

|

| |

| Ever Had a Pap test | |

| Yes | 158 (97.5%) |

| No | 3 (1.9%) |

| Don’t know | 1 (0.6%) |

|

| |

| Time since last Pap test | |

| ≥3 ≤5 years ago | 98 (59.8%) |

| >5 ≤10 years ago | 44 (27.2%) |

| >10 years ago | 13 (8.0%) |

| Never had a Pap test | 3 (1.9%) |

| Don’t know | 1 (0.6%) |

| Had a Pap but can’t remember when | 3 (1.9%) |

|

| |

| Reasons for non-compliance | |

| I never thought about it | 2 (1.2%) |

| I didn’t know that I needed one | 4 (2.5%) |

| My Doctor didn’t tell me that I needed one | 1 (0.6%) |

| I haven’t had any problems | 10 (6.2%) |

| I kept putting it off | 44 (27.2%) |

| Too expensive | 18 (11.1%) |

| No insurance | 17 (10.5%) |

| Too painful/unpleasant | 1 (0.6%) |

| Too embarrassing | 5 (3.1%) |

| I’m not sexually active | 2 (1.2%) |

| I’m a virgin | 1 (0.6%) |

| I am afraid of the results | 2 (1.2%) |

| No reason | 3 (1.9%) |

| Other | 3 (1.9%) |

| No response | 49 (30.3%) |

|

| |

| Received a Pap test after the intervention | |

| Yes | 124 (76.5%) |

| No | 38 (23.5%) |

Of the 162 participants who took part in the study, 124 (76.5%) received a Pap test post-intervention. Baseline characteristics such as years resident in the US, education, country of birth, smoking history, language preferred, whether or not a participant had insurance coverage, and age were not observed to differ between participants who received a Pap test post-intervention and those who did not (data not shown).

We next examined knowledge of, and attitudes towards cervical cancer and Pap test screening at baseline and post-intervention (Table 2). There was no observed change relating to knowledge of the importance of Pap tests for post-menopausal women, with more than 90% of women at both time points aware of its importance in older women. Similarly, there was no observed change in knowledge of whether Pap tests were blood tests; whether they can only detect advanced cancer; if Pap tests were only required when bleeding or pain were present (over 90% of women disagreed at both time points); that all women regardless of how many partners she may have had should have a Pap test; or if the HPV vaccine can prevent cervical cancer.

Table 2. Knowledge and Attitudes Towards the Pap Test and HPV Before and After the Intervention.

| Question | Scale | Baseline Survey |

Final Survey |

P (McNemar’ stest) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

|

Pap testing is a blood test

(N=159) |

True | 4 (2.5) | 4 (2.5) | |

| False | 145 (91.2) | 158 (97.5) | .56 | |

| Don’t know | 10 (6.3) | 0 | ||

|

| ||||

|

Post-menopausal women

need to have a Pap test (N=161) |

True | 146 (90.2) | 162 (100) | .05 |

| False | 4 (2.5) | 0 | ||

| Don’t know | 12 (7.4) | 0 | ||

|

| ||||

|

Only women who have many

partners need to get a Pap test (N=162) |

True | 8 (5.0) | 5 (3.1) | .26 |

| False | 153 (95.0) | 157 (96.9) | ||

|

| ||||

|

A Pap test can only detect

(advanced) (invasive) cervical cancer (n=161) |

True | 32 (19.9) | 32 (19.8) | .75 |

| False | 114 (70.8) | 128 (79.0) | ||

| Don’t know | 14 (8.7) | 2 (1.2) | ||

| Refused | 1(0.6) | 0 | ||

|

| ||||

|

I need a Pap test only when I

experience problems like pain or abnormal vaginal bleeding (n=162) |

True | 6 (3.7) | 5 (3.1) | .74 |

| False | 153 (94.4) | 156 (96.3) | ||

| Don’t know | 3 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | ||

|

| ||||

|

It is too embarrassing to have

a Pap test (N=162) |

Strongly Agree | 6 (3.7) | 53 (32.7) | .0001 |

| Agree | 70 (43.2) | 107 (66.1) | ||

| Disagree | 81 (50.0) | 2 (1.2) | ||

| Strongly Disagree |

5 (3.1) | 0 | ||

|

| ||||

|

If cancer of the cervix is

detected early, a person is more likely to be cured (N=162) |

Strongly Agree | 54 (33.3) | 125 (77.2) | .0001 |

| Agree | 94 (58.0) | 37 (22.8) | ||

| Disagree | 10 (6.2) | 0 | ||

| Strongly Disagree |

4 (2.7) | 0 | ||

|

| ||||

|

A woman can usually tell if

she has HPV |

True | 23 (14.4) | 13 (8.0) | .01 |

| False | 101 (63.1) | 144 (88.9) | ||

| Don’t know | 34 (21.3) | 5 (3.1) | ||

| Refused | 2 (1.3) | 0 | ||

|

| ||||

|

Women who get the HPV

vaccine should continue to get Pap tests. |

Strongly Agree | 44 (27.3) | 124 (76.5) | .001 |

| Agree | 91 (56.5) | 37 (22.8) | ||

| Disagree | 13 (8.1) | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Strongly Disagree |

0 | 0 | ||

| Don’t know | 13 (8.1) | 0 | ||

|

| ||||

|

The HPV vaccine can

prevent cervical cancer |

Strongly Agree | 29 (18.2) | 102 (63.0) | .81 |

| Agree | 96 (60.4) | 42 (25.9) | ||

| Disagree | 12(7.6) | 13 (8.1) | ||

| Strongly Disagree |

22 (13.8) | 16 (9.9) | ||

| Don’t know | 0 | 2 (1.2) | ||

|

| ||||

|

I would get the HPV vaccine

if my doctor or nurse recommended it. |

Strongly Agree | 33 (20.6) | 106 (65.4) | <.0001 |

| Agree | 92 (57.5) | 52 (32.1) | ||

| Disagree | 23 (14.4) | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Strongly Disagree |

1 (0.6) | 0 | ||

| Don’t know | 11 (6.9) | 3 (1.9) | ||

In contrast, we observed statistically significant changes when we asked whether post-menopausal women need to have a Pap test (P = .05). Approximately 10% more women agreed with the statement post-intervention. Similarly, 43.1% more women appeared to be aware of the importance of early detection to effect a cure post-intervention, and differences were statistically significant between pre- and post-intervention (P < .0001). We also observed a statistically significant change in the response to the statement: “It is too embarrassing to have a Pap test” (P < .0001). However, post-intervention, more study participants agreed or strongly agreed with this statement (98.8%), compared to only 46.9% at baseline. The intervention was also associated with changes in knowledge about the HPV vaccine, with statistically significant changes between pre- and post-intervention for “A woman can usually tell if she has HPV” and “Women who get the HPV vaccine should continue to get Pap tests” (P = .01 and P = .001, respectively). Finally, more women agreed/strongly agreed with the statement that they would get the HPV vaccine if their doctor or nurse recommended it post-intervention (P < .0001 for changes between pre- and post-intervention).

We next examined whether baseline attitudes and knowledge differed between women who went on to have a Pap test, compared to those who did not (Table 3). All participants had heard of a Pap test. Among women who answered “a Pap test can find a problem even before it develops into cancer,” there was a statistically significant difference between those who received compared to those who did not receive a Pap test post-intervention (P = .05). The frequencies among participants in the study showed that women who were aware of this fact were more likely to get a Pap test post-intervention. In reporting level of agreement to the statement “Getting a Pap test would only make me worry,” there was a statistically significant difference between women who received or did not receive a Pap test post-intervention (P = .03). Specifically, the study participants were more likely to agree if they did not receive a Pap test post-intervention.

Table 3. Attitudes Towards and Knowledge of Cervical Cancer Screening at Baseline.

| All | Did not receive Pap test post intervention N=38 (%) |

Received Pap test post intervention N=124 (%) |

P Fisher’s exact test |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Have you ever heard of a Pap test? | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 162 | 38 (100.0) | 124 (100) | - |

| No | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

|

| ||||

| Do you think it’s necessary to have a Pap test? | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 160 | 37 (97.4) | 123 (99.2) | .42 |

| No | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.8% | |

| Don’t Know | 1 | 1 (2.6) | 0 | |

|

| ||||

| A Pap test can find a problem even before it develops into cancer. | ||||

|

| ||||

| True | 97 | 17 (44.7) | 80 (64.5) | .05 |

| False | 61 | 20 (52.6) | 41 (33.1) | |

| Don’t know | 3 | 0 | 3 (2.4) | |

|

| ||||

| A Pap test is necessary even if there is no family history of cancer | ||||

|

| ||||

| True | 88 | 16 (42.1) | 72 (58.1) | .15 |

| False | 73 | 22 (57.9) | 51 (41.1) | |

| Don’t know | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.8) | |

|

| ||||

| Having regular Pap tests would give me peace of mind about my health | ||||

|

| ||||

| Strongly Agree | 69 | 13 (34.2) | 56 (45.2) | .44 |

| Agree | 92 | 25 (65.8) | 67 (45.0) | |

| Don’t know | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.8) | |

|

| ||||

| Getting a Pap test would only make me worry | ||||

|

| ||||

| Strongly Agree | 9 | 1 (2.6) | 8 (6.5) | .03 |

| Agree | 42 | 15 (39.5) | 27 (21.8) | |

| Disagree | 96 | 16 (42.1) | 80 (64.4) | |

| Strongly disagree | 14 | 6 (15.8) | 8 (6.5) | |

| Don’t know | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.8) | |

|

| ||||

| The Pap test is painful | ||||

|

| ||||

| Strongly Agree | 0 | 0 | 0 | .06 |

| Agree | 23 | 10 (26.3) | 13 (10.5) | |

| Disagree | 125 | 24 (63.2) | 101 (81.5) | |

| Strongly disagree | 10 | 3 (7.9) | 7(5.7) | |

| Don’t know | 4 | 1 (2.6) | 3 (2.4) | |

|

| ||||

| Only women who have had many partners need to get a Pap test | ||||

|

| ||||

| True | 8 | 4 (10.5) | 4 (3.2) | .09 |

| False | 153 | 34 (89.5) | 119 (95.8) | |

| Don’t know | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

|

| ||||

| I don’t know where I could go if I wanted a Pap test | ||||

|

| ||||

| Strongly Agree | 5 | 1 (2.6) | 4 (3.2) | .96 |

| Agree | 50 | 12 (31.6) | 38 (30.6) | |

| Disagree | 99 | 23 (60.5) | 76 (61.3) | |

| Strongly disagree | 6 | 2 (5.3) | 4 (3.2) | |

| Don’t know | 2 | 0 | 2 (1.6) | |

|

| ||||

| My partner (boyfriend/husband) would not want me to have a Pap test. | ||||

|

| ||||

| Agree | 8 | 2 (5.3) | 6 (4.8) | .78 |

| Disagree | 137 | 34 (89.5) | 103 (83.1) | |

| Strongly disagree | 15 | 2 (5.3) | 13 (10.5) | |

| Don’t know | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.8) | |

|

| ||||

| A Pap test is not important for a woman my age. | ||||

|

| ||||

| Strongly Agree | 6 | 1 (2.6) | 5 (4.1) | .82 |

| Agree | 22 | 6 (15.8) | 16 (12.9) | |

| Disagree | 121 | 30 (79.0) | 91 (73.3) | |

| Strongly disagree | 11 | 1 (2.6) | 10 (8.1) | |

| Don’t know | 2 | 0 | 2(1.6) | |

DISCUSSION

This project demonstrated that a culturally appropriate, CHW-led intervention is successful at encouraging non-compliant Hispanic women, resident in the US-México border region, to have a Pap test. More than three-quarters (76.5%) of previously non-compliant women had a Pap test post-intervention. The intervention was also successful at educating women about cervical cancer and the importance of screening. There were few differences at baseline between women who did and did not have a Pap test post-intervention. Women who did not have a Pap test were more likely to agree or strongly agree with the statement that a Pap test would make them worry.

Cervical cancer screening detects pre-cancerous changes in the cervix, such as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or cervical dysplasia. Introduction of the test screening programs to women in all populations reduces cervical cancer rates by 60%-90% within 3 years of implementation, with the reduction of mortality and morbidity consistent across populations.18,19 In the US, the US Preventative Task Force guidelines for Pap testing are every 3 years for routine screening for women over the age of 21, or from 3 years after the age of initiation of sexual activity, whichever is earlier.8

In the US, 12,410 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer each year, and of these Hispanic women have the highest incidence rate with an age-adjusted incidence of 12.5 cases/100,000 women for 2004-2008, compared to an incidence of 7.0 in the non-Hispanic white population.6 In addition, more than 60% of cases occur in areas of underserved, under-screened populations of women.20 Mortality from cervical cancer is also higher among Hispanics compared to non-Hispanic whites (estimates for age-adjusted US mortality rates for 2008: 2.9 per 100,000 vs 2.1 per 100,000).6 The disproportionate burden of cervical cancer among Hispanic women is thought to be attributable in part to both low rates of screening and poor adherence to recommended diagnostic follow-up after an abnormal Pap test.

Sociodemographic factors associated with non-adherence to cervical cancer screening in Hispanic women include low income, lack of health insurance, limited access to health care services, length of residency in the United States, limited English language proficiency, acculturation, and lack of awareness of risks associated with non-participation in cervical cancer screening programs.20-23 Low utilization of screening leads to delayed detection of disease and an increased burden on health care systems. Each year, an estimated $4.6 billion is spent in the US on the treatment of new cases of cervical neoplasia or cancer.24 Timely detection and treatment of pre-cancerous lesions and the early detection of cancers could substantially reduce this cost.

Culturally appropriate interventions have the potential to enhance cancer screening and to encourage cervical health. The US Preventive Task Force identified one-on-one education as an effective strategy for increasing cervical cancer screening.25 Several studies enrolling Hispanic participants have used such strategies, and many have enlisted CHW.12,26-28 CHWs are generally of the same cultural background as the target population and serve as connectors between health care providers and groups who have traditionally lacked access to adequate care.29

The US-México border region is an area characterized by poverty and health disparities, especially among Hispanic women; thus, implementing cervical cancer screening programs, and encouraging women to meet recommended screening guidelines, presents a distinct set of challenges in this population. A limited number of studies have investigated the effects of culturally appropriate CHW-led interventions among Hispanic women residing along the US-México border. One randomized clinical trial (RCT) in 381 post-menopausal women randomized women to a group-based educational intervention, or to usual care. Women in the intervention group were 1.5-times more likely to have a Pap test compared to those in the usual care arm of the study, although this was not statistically significant (odds ratio 1.5, 95% confidence interval 0.90-2.6).16

Another CHW-led educational intervention educated 366 Hispanic women in breast, cervical and colorectal cancer prevention and screening and emphasized social support among class members; 39% of previously non-compliant women went on to have a Pap test.28 Finally, a similar intervention in 243 non-compliant Hispanic women resulted in 39.5% of the participants having a Pap test, compared to 23.6% in the control (where intervention and control groups were randomly selected communities from the border areas).12

This study contributes to the findings that CHW-led, educational one-on-one interventions are an effective means of increasing uptake of cervical cancer screening in a vulnerable community, specifically Hispanic women resident on the US-México border.

The women who participated in this study appeared to have much knowledge about cervical cancer and the need for screening. For example, 90% of women at baseline knew that older women, those who were post-menopausal, should continue to be screened and this increased to 100% at follow-up. In addition, at follow-up, all women knew that cervical cancer could be cured if detected early; the level of agreement went from simply “agree” at baseline to “strongly agree” at follow-up.

Women who participated were quite knowledgeable about HPV, with close to a majority at baseline recognizing that a woman could not tell if she had HPV; at follow-up, 89% of women stated that they knew this was the case. Further, the proportion of women agreeing or strongly agreeing that they would get the HPV vaccine if recommended by a health care provider increased significantly after the intervention to 97.5%.

The results raise a question about the perception of Pap tests as “too embarrassing” post-intervention. The intervention contained a brief video of a Pap test; the video may have contributed to the embarrassment of women. Although 97.5% of women reported having had a Pap test in the past, over a third (Table 1) of participants had their last test more than 5 years ago. It is not clear to what degree “embarrassment” over the procedure had been a deterrent to subsequent Pap testing. However, 76.5% of participants went on to have a Pap test; thus, we conclude that when delivered in the appropriate intervention context, this unexpected result from the intervention did not prevent women from having a Pap test. However, targeted informational interventions in similar populations may need to take this into account when designing interventions, and provide reassurance on this point. Perceptions identified in young Hispanic women from another study on the US-México border were that the test would be painful. This was negatively associated with ever having a Pap test.30

Limitations of the current study include the fact that we do not have any controls. In future studies, we would like to recruit control clinics and administer questionnaires to non-complaint women in these clinics, and track their compliance with recommended Pap testing during the same time period, compared to compliance in intervention clinics. We did not fully evaluate the influence of each of the components of the intervention. For example, having more flexible clinic opening hours, and assisting women with making appointments, may be of equal importance as the intervention itself. However, the increase in knowledge may have future beneficial effects on behavior; for example significantly more women reported that they were likely to get an HPV vaccine if their health care provider recommended it, post-intervention. Finally, participants were recruited from a single country within the Border region, and our findings may not be generalizable to other settings. While it was outside the scope of the study, repeated contact with the participants would be of interest to collect information on long-term behavior change.

In conclusion, our CHW-led intervention was successful in encouraging Hispanic women to have a Pap test. Future research should focus on a randomized, controlled trial that seeks to increase cervical cancer screening among Hispanic women. Further, it is important to establish how much minority women know about HPV and its relationship to cervical cancer. Finally, this study showed that a CHW-led intervention was successful; future studies should evaluate this approach for other diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the women who participated in this project.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute to Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (U54 CA132381) and to New México State University (U54 CA 132383).

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.United States-México Border Health Commission [Accessed June 25, 2013];Health Disparities and the U.S.-México Border: Challenges and Opportunities. 2010 Available at: http://www.borderhealth.org/files/res_1719.pdf.

- 2.United States-México Border Health Commission [Accessed June 25, 2013];The U.S./Mexico Border: Health Care Access and Resource Profile II. 2006 Available at: http://www.borderhealth.org/files/res_1719.pdf.

- 3.Bastida E, Brown HS, 3rd, Pagan JA. Persistent disparities in the use of health care along the US-Mexico border: an ecological perspective. Am J Public Health. 2008 Nov;98(11):1987–1995. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrillo JE, Carrillo VA, Perez HR, Salas-Lopez D, Natale-Pereira A, Byron AT. Defining and targeting health care access barriers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(2):562–575. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services HRaSA, Maternal and Child Health Bureau . Women’s Health USA 2011. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, Maryland: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.US National Institute of Health . SEER Incidence and U.S. Mortality Age-Adjusted Rates and Trends, 1973-2008. National Center for Health Statistics, CDC; Atlanta, GA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coughlin SS, Richards TB, Nasseri K, et al. Cervical cancer incidence in the United States in the US-Mexico border region, 1998-2003. Cancer. 2008 Nov 15;113(10 Suppl):2964–2973. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Department of Health and Human Services . US Preventive Services Task Force: Screening for Cervical Cancer. Recommendations and Rationale. US Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Cancer Society . Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2009. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engelstad LP, Stewart SL, Nguyen BH, et al. Abnormal Pap smear follow-up in a high-risk population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001 Oct;10(10):1015–1020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones HW., 3rd Clinical treatment of women with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance cervical cytology. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Jun;43(2):381–393. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200006000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez ME, Gonzales A, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Effectiveness of Cultivando la Salud: a breast and cervical cancer screening promotion program for low-income Hispanic women. Am J Public Health. 2009 May;99(5):936–943. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.136713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez LM, Martinez J. Community health workers: social justice and policy advocates for community health and well-being. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):11–14. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabatino SA, Lawrence B, Elder R, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to increase screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers: nine updated systematic reviews for the guide to community preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2012 Jul;43(1):97–118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez ME, Diamond PM, Rakowski W, et al. Development and validation of a cervical cancer screening self-efficacy scale for low-income Mexican American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009 Mar;18(3):866–875. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nuno T, Martinez ME, Harris R, Garcia F. A Promotora-administered group education intervention to promote breast and cervical cancer screening in a rural community along the U.S.-Mexico border: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Causes Control. 2011 Mar;22(3):367–374. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9705-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou SI, Fernandez ME, Parcel GS. Development of a cervical cancer educational program for Chinese women using intervention mapping. Health Prom Behavior. 2004;5(1):80–87. doi: 10.1177/1524839903257311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Working Group The Evaluation of Cervical Cancer Screening Programmes. Screening for squamous cervical cancer: duration of low risk after negative results of cervical cytology and its implication for screening policies. Br Med J. 1986;293(6548):659–664. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6548.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sasieni PD, Cuzick J, Lynch-Farmery E. Estimating the efficacy of screening by auditing smear histories of women with and without cervical cancer. The National Co-ordinating Network for Cervical Screening Working Group. Br J Cancer. 1996;73(8):1001–1005. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scarinci IC, Garcia FA, Kobetz E, et al. Cervical cancer prevention: new tools and old barriers. Cancer. 2010 Jun 1;116(11):2531–2542. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bazargan M, Bazargan SH, Farooq M, Baker RS. Correlates of cervical cancer screening among underserved Hispanic and African-American women. Prev Med. 2004 Sep;39(3):465–473. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson CE, Mues KE, Mayne SL, Kiblawi AN. Cervical cancer screening among immigrants and ethnic minorities: a systematic review using the Health Belief Model. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2008 Jul;12(3):232–241. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31815d8d88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harmon MP, Castro FG, Coe K. Acculturation and cervical cancer: knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors of Hispanic women. Women Health. 1996;24(3):37–57. doi: 10.1300/j013v24n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith JS. Ethnic disparities in cervical cancer illness burden and subsequent care: a prospective view in managed care. Am J Manag Care. 2008 Jun;14(6 Suppl 1):S193–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guide to Community Preventive Services. Available at: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html. Page last updated: March 29, 2012.

- 26.Navarro AM, Senn KL, McNicholas LJ, Kaplan RM, Roppe B, Cambo MC. Por La Vida model enhances uses of cancer screening tests among Latinas. Am J Prev Med. 1998;15:32–41. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansen LK, Feigl P, Modiano MR, et al. An educational program to increase cervical and breast cancer screening in Hispanic women: a Southwest Oncology Group study. Cancer Nursing. 2005 Jan-Feb;28(1):47–53. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200501000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larkey L. Las mujeres saludables: reaching Latinas for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer prevention and screening. J Community Health. 2006 Feb;31(1):69–77. doi: 10.1007/s10900-005-8190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunter JB, de Zapien JG, Papenfuss M, Fernandez ML, Meister J, Giuliano AR. The impact of a promotora on increasing routine chronic disease prevention among women aged 40 and older at the U.S.-Mexico border. Health Education & Behavior. 2004 Aug;31(4 Suppl):18S–28S. doi: 10.1177/1090198104266004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Byrd TL, Peterson SK, Chavez R, Heckert A. Cervical cancer screening beliefs among young Hispanic women. Prev Med. 2004 Feb;38(2):192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]