SUMMARY

In a unique longitudinal study of teen driving, risky driving behavior and the occurrence of crashes or near crashes are measured prospectively over the first 18 months of licensure. Of scientific interest is relating the two processes and developing a predictor of crashes from previous risky driving behavior. In this work, we propose two latent class models for relating risky driving behavior to the occurrence of a crash or near crash event. The first approach models the binary longitudinal crash/near crash outcome using a binary latent variable which depends on risky driving covariates and previous outcomes. A random effects model introduces heterogeneity among subjects in modeling the mean value of the latent state. The second approach extends the first model to the ordinal case where the latent state is composed of K ordinal classes. Additionally, we discuss an alternate hidden Markov model formulation. Estimation is performed using the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm and Monte Carlo EM. We illustrate the importance of using these latent class modeling approaches through the analysis of the teen driving behavior.

Keywords: driving study, latent class modeling, Monte Carlo EM

1 INTRODUCTION

Modeling events using latent variables to account for the correlation among outcomes has been widely used in a number of areas including educational testing, sociological analysis, and health outcomes. Several models have been developed where the latent variable is categorical (known as a latent class model). Lazarsfeld and Henry (1968) introduced these models to perform sociological analysis. Models where the latent variable is continuous (known as a latent trait model) are also well known and have been of particular use in educational testing as shown by Rasch (1966). Each of these latent variable models is focused on determination of the minimum number of latent variables needed to account for the correlation among observed outcomes. Our interest in this work was motivated by the prediction of crash and near crash events of newly licensed teenage drivers. As one might imagine, there are characteristics that are not observed which describe these events, most notably risky driving. In this paper we first propose a binary latent variable model for analysis of crash and near crash events and extend this model in two ways. First, the latent state describing driving ability is expanded to account for multiple, ordered latent classes (an ordinal latent variable model). In doing this we provide an intermediary between latent class and latent trait models. Second, we allow for heterogeneity among subjects’ latent class membership by introducing a random effect in the latent state.

We developed this class of models based on the work of Legler and Ryan (1997) and Hu, et al. (2004). Legler developed a construct where multiple birth defects are treated as binary outcomes and modeled using a Poisson latent variable which was helpful in simplifying the computation of parameter estimates. Hu, et al. (2004) propose a binary latent variable modelling approach for analysis of respiratory symptoms associated with air pollution. We extend their approach by allowing the latent class to be ordered in multiple categories as well allowing heterogeneity among subjects’ latent class membership. The models presented are two-stage models. In the first stage, covariates describe latent class membership and in the second stage the latent variable describes the binary outcome. Application of these models is made to a first of its kind teenage driving study.

There are also alternative approaches that are appealing because they can give insight into the hidden process. Using a hidden Markov model, one could describe the transition probabilities with the kinematic data as well as the previous crash/near crash outcomes. Bartolucci and Pennoni (2007) present a class of latent Markov models for the analysis of capture-recapture data that takes into account the previous capture behavior. In Bartolucci, et al. (2009), the authors present a method of estimating the effect of nursing homes on the transition probabilities between states in a hidden Markov chain. The latter approach was appealing for our study because understanding the hidden process might yield additional insights into teenage driving behavior and serves as a nice extension of our modeling approach. This approach is also quite flexible as it allows the investigator to evaluate several conditional distributions of interest when making predictions that are readily available as a byproduct of using this approach as discussed in Mac-Donald and Zucchini (1997). There are detractors to this approach in that extension to multiple hidden classes is not as straightforward, especially if random effects are necessary to adequately describe heterogeneity in the transition matrix for the hidden states. We include results for the hidden Markov approach for those interested in this model. In terms of predictive power, the hidden Markov approach performed similarly to the other models we propose.

The paper is outlined as follows: we first discuss the driving study followed by our different modeling approaches. Estimation procedures for each of these models is presented along with simulation results for each of the models. As a comparison, we present an alternative approach using a hidden Markov model. We close with a presentation and discussion of our model results.

2 TEENAGE DRIVING STUDY

Studies have shown that crash rates among teenagers are several times greater than those experienced by middle-age drivers NHTSA (2000). Several studies such as the one discussed by Simons-Morton, et. al. (2005) have evaluated crash rates for 16- or 17-year-old drivers in the presence of teen passengers , but very little is understood about the association between risky driving behavior and crash outcomes of teenage drivers. Understanding the association between risky driving behavior and crash or near crash outcomes would give greater insight to teenage driving behavior and assist in the development of safer teenage drivers by educating these drivers on specific risky behaviors as they relate to vehicle operation during driver training.

The motivation for development of these models was to provide insights into the driving behavior of newly licensed teenage drivers using the data gathered from the Naturalistic Teenage Driving Study (NTDS). The study, sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) was conducted to evaluate the effects of experience on teen driving performance under various driving conditions. Researchers recruited forty-two novice teen drivers at the time of licensure and equipped their vehicles with cameras, g-force meters, Global Positioning System (GPS), and other equipment to provide detailed information about driving performance during the first eighteen months of driving experience. The dataset is particularly interesting in that incredible detail is provided for each driver by way of analyzing each trip the participant takes throughout the study period for a variety of measurements. The focus for this research is on prediction of crash/near crash outcomes and their association with risky driving behavior.

In the models that follow, certain kinematic measures evaluated during each trip serve as a proxy for risky driving. A lateral accelerometer captured driver steering control by measuring g-forces the automobile experiences. These recordings provide two kinematic measures: lateral accelerations during left (– acceleration) and right (+ acceleration) turns. A longitudinal accelerometer captured driving behavior along a straight path and records accelerations or decelerations. Another measure for steering control is the vehicle’s yaw rate which can be thought of as the vehicle’s angular deviation from the longitudinal direction of the automobile’s path after making a course correction. Each of these kinematic measures was recorded as count data during each trip as they crossed specified thresholds that represent normal driving behavior. Crash and near crash outcomes (CNCs) were recorded in several different ways. First, the driver of each vehicle has the ability to self report these events. Second, video cameras provided front and rear views from the car. Trained technicians analyzed each trip the driver took during the eighteen month period using the video to determine crash/near crash events. Data for each of the kinematic measures in the study are aggregated monthly due to a relatively small number of crash or near crash events and are shown in Table 1. The driving kinematic measures enter the model as the number of kinematic events per mile driven during a particular month to accurately represent risky behavior across all drivers. More information on the driving study can be found at the Virginia Tech Center for Automotive Safety Research website at http://www.vtti.vt.edu/casrresearch/Naturalistic Teenage Driving Study.php.

Table 1.

Kinematic measures and their correlation with CNCs, Naturalistic Teenage Driving Study, 1 correlation computed between the CNC and elevated g-force events based on monthly rates.

| Category | Gravitation Force | Frequency | % Total Events | Correlation with CNCs1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid starts | > 0:35 | 8747 | 39.6 | 0.28 |

| Hard stops | ≤ −0:45 | 4228 | 19.1 | 0.76 |

| Hard left turns | ≤ −0:05 | 4563 | 20.6 | 0.53 |

| Hard right turns | ≥ 0:05 | 3185 | 14.4 | 0.62 |

| Yaw | 6 deg in 3 seconds | 1367 | 6.2 | 0.46 |

| Total | 22090 | 100 | 0.60 |

The methods presented perform several roles in the context of the NTDS. First, they help gain insight to understanding the relationship between driving behavior and CNCs. Second, they provide a means of predicting CNCs from certain driving behavior characteristics. Third, they lend an understanding as to how driving behavior among these newly licensed teenagers changes over the course of their first 18 months of licensure.

3 THE MODELS

If we consider a longitudinal data set where we observe binary and count outcomes for individuals and assume that there exists some unobservable underlying process representing the ‘risky driving’ state that influences these outcomes, then we can elicit a summary measure for each individual’s ‘state’ probability that will give insight into the variability of poor driving over time. The model can be thought of as consisting of two stages whereby the latent state describes the observed outcome. In the first stage, a binary latent state models a binary outcome and in the second stage, the count outcomes and previous binary outcomes describe the state of the individual at a particular time point. Let (yi1, yi2,…,yini) be the sequence of ni crash/near crash binary outcomes for the ith teenage driver and xi,j–1 be a vector consisting of kinematic measures for individual i during month j–1.

Model 1: Binary Latent Variable

| (1) |

where bij is a binary latent variable describing the hidden state at a particular time point and follows a Bernoulli distribution (πij). Choosing to model the latent variable in this manner allows for easy interpretation with bij = 0,1 representing a latent class of high or low risk as the outcome of interest might dictate. Using this latent model construct, it is assumed that the latent variable describing the binary outcome accounts for any correlation between observations; so given this latent variable, the observations on the outcome are independent. We induce a correlation between the latent states by including the previous month’s crash/near crash outcome, yi,j–1. A unique aspect to this model is the offset term log(mij) where mij is the number of miles driven by a driver during a month. This offset term represents driver exposure during each time period.

In the Section 6 we discuss an alternative formulation where the bij follow a hidden Markov model where the transition probabilities depend on the xi,j–1. However, extension to higher numbers of latent states while accounting for heterogeneity is more diffcult to incorporate under the hidden Markov model framework than in Model 1. The extension of Model 1 to incorporate K latent classes is easily achieved. For this model bijk reflects the probability of latent class membership k for individual i during the jth time period. The second logit in (2) preserves the appropriate range of values for the hidden state. Incorporating a proportional odds model Agresti (2002) for the second logit we are able to satisfy the requirements that bijk ∈ (0, 1) as well as for any time period. Thus an ordinal model for K classes is

Model 2: Ordinal Latent Variable

| (2) |

We extend each of these models by incorporating heterogeneity among subjects in the latent state. In doing this we account for any variation that is not explained using the previous month’s outcome yi,j–1 and kinematic measures xi,j–1 using a normal distribution for the random effect. We refer to these as latent random effects models shown here:

Model 1R: Binary Latent Variable with Random Effect

| (3) |

Model 2R: Ordinal Latent Variable with Random Effect

| (4) |

where ui ~ N(0,λ)

Interpretation of parameters is straightforward with the coefficients of the latent state describing latent state influence on the predicted outcome in addition to an odds-ratio for the poor (bij = 1) versus good (bij = 0) driving state. Similarly, an odds-ratio for the latent state can be computed based on the previous crash or near crash outcome yi,j–1 given all other kinematic measures are held fixed. The odds-ratio for a one unit increase in a specific kinematic measure βk given all other measures held fixed is also available. For the random effects models, λ indicates the degree of heterogeneity among subjects.

4 ESTIMATION

In this section, we present an implementation of the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm Dempster, et al. (1977) for estimating model parameters for the models without random effects (Models 1 and 2) and an implementation of the Monte-Carlo EM algorithm for the models with random effects (Models 1R and 2R).

4.1 Estimation for Models 1 and 2

The expectation maximization algorithm for Model 1 and Model 2 consist of taking the expectation of the complete data log-likelihood with respect to the conditional distribution of the latent variable b given the observed data and the previous parameter estimates. The EM algorithm implementation here iterates between an E-step where the the posterior density values are computed {bij|yi} and an M-step where the expectations are maximized with respect to the model parameters using a weighted regression analysis approach. Since b is a Bernoulli random variable, this calculation is fairly straightforward simply requiring us to sum over bij = 0, 1. For our model the expectation step is:

| (5) |

where Ψ represents all of the parameters in the model presented in section 3 and Ψt are the parameters values from the previous iteration and l(Ψ; Y, b) represents the complete data log-likelihood. Summing over the values of b, the expectation step for Model 1 becomes:

| (6) |

where g is the conditional distribution of the latent variable given the observed data. Note that the parameters associated with logit Pr(Yij = 1), denoted by α, and logit Pr(bij = 1), denoted by (θ, β) are separate in equation (6). This implies that the expression can now be maximized by separately maximizing

| (7) |

with respect to α, and maximizing

| (8) |

with respect to θ and β where is Pr(bij = 1|yi, Ψt). Both of the above functions can be handled as weighted log-likelihoods in the following manner. If we augment the data matrix by duplicating in row (Xij, Yij) into an augmented form with (Xijl, Yijl) with l = 0, 1 and Xij0 = Xij1 = Xij and Yij0 = Yij1 = Yij and add a column bijl = l and another column then maximization of (7) can be carried out as a weighted regression analysis of Yijl on bijl with weight wijl under the model logit(Pr(Yijl = 1|bijl)) and maximization of (8) can be carried out as a weighted regression analysis of bijl on Xijl with weight wijl under the model logit(Pr(bijl = 1|Xijl)). Once the augmented dataset is constructed, only the weights need to be updated at each iteration. Parameter estimates are not sensitive to initial values as demonstrated in the simulation section. Computations were implemented in R (2009) in the manner shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Procedure for finding estimates to Model 1

| 1. Choose initial parameter values p0 |

| 2. Establish initial weight for each observation |

| 3. Perform logistic regression of the latent variable according to the model |

| 4. Update parameter estimates for (θ, β) |

| 5. Update weights wij |

| 6. Perform logistic regression of the response according to the model |

| 7. Update parameter estimates for α |

| 8. Update weights and repeat the procedure until parameter estimates converge |

Estimation of Model 2 proceeds in a similar fashion, the only difference being taking account of all possible latent class possibilities for each subject. The complete data log-likelihood for Model 2 is given by:

| (9) |

where πbk is the probability of membership in latent class k. In equation (9) we see the same situation as encountered in the binary latent variable model where parameters associated with each logit in Model 2 are separate, therefore proceeding along a weighted regression approach is justified as in the binary latent model in the previous section. In the E-step, we take the conditional expectation of the complete data log-likelihood given the current parameter estimates Ψt with respect to the conditional distribution of bijk|yi, Ψt which is denoted by πijk. For both Models 1 and 2, Pr(yi1 = 1) was common to all subjects and estimated using the first month crash/near crash outcomes. As in the binary case, we augment the data matrix by duplicating each element to represent each of the three categories. Each duplication is then matched with a value for bijk = k as well as its assigned weight wijk which is the posterior probability for that latent class so . Maximization can then be carried out as a weighted proportional odds logistic regression of bijk on Xijk with weight wijk and a weighted logistic regression analysis of Yijk on bijk with weight wijk. At each iteration, the weights wijk are updated according to the results given by the separate regression analyses.

4.2 Estimation for Models 1R and 2R

In this section we discuss the estimation procedure for the binary latent variable random effects model (Model 1R). Maximum likelihood estimation for this model involves maximizing the likelihood shown here:

| (10) |

where πbij denotes Pr(bij = 1) as directed by Model 1R. The above expression cannot be evaluated in closed form and includes an integral taken over a product of each subject. So an alternative approach is needed. The expectation of the complete data log-likelihood is taken with respect to the conditional distribution (bi, ui|yi). A Monte Carlo EM algorithm is used to maximize the likelihood with a similar approach to that used in Albert, et al. (2002) accounting for both latent variables and presented in this section. The Monte Carlo EM (MCEM) algorithm is a modication of the EM algorithm where the expectation in the E-step is computed numerically through Monte Carlo simulations Levine and Casella (2001).

To generate random draws from the conditional distribution of (bi, ui|yi) we use an implementation of the Metropolis algorithm as described in McCulloch (1997). The algorithm produces random draws from the conditional distribution of the missing data given the observed data without having to discern the joint distribution of (yi, bi, ui). A candidate distribution is specified from whom new potential values are drawn. The acceptance function determines whether or not a current draw from the conditional distribution is accepted or if the previous value is kept and the next draw is taken. The acceptance function for the latent model is given by:

| (11) |

If hb,u is based on the distribution of the random effect as shown in McCulloch (1997), then the acceptance function takes on a simplified form:

| (12) |

where f(bi, u) is a function for each individual whose argument is a vector of values generated by evaluating the second stage logit model for a randomly generated ui then evaluated as

| (13) |

Implementing the EM algorithm using the Metropolis step gives a Monte-Carlo EM algorithm, the procedures for its implementation are shown here:

1. Select initial values for (α0, β0, λ0). 2. Generate N values of from the posterior distribution of , by first generating a random draw from f(ui), then for i = 1,…,I implementing the Metropolis algorithm as discussed earlier. 3. Maximize the Monte Carlo estimate of which is

by performing a regression on the first two components of the log-likelihood shown in the following manner: (a) Assign a value of 0 or 1 to each realization of bij by generating a value from a Bernoulli distribution with parameter determined using the Metropolis algorithm. In accordance with maximizing the Monte-Carlo estimate, each observation is assigned a weight of 1/N. (b) Perform logistic regression of the bij onto the covariates using the generated random effect ui as an offset. (c) Update parameters associated with this second stage of the model . Note that the parameter associated with the variance component is updated separately using its maximum likelihood estimate. (d) Generate N vectors of the posterior distribution using the Metropolis algorithm for each subject. (e) Perform logistic regression of the yij onto the bij with each observation assigned a weight of 1/N as in the previous regression. (f) Update parameters associated with the first stage of the model . (g) Generate N vectors of the posterior distribution using the Metropolis algorithm and return to (a). 4. Iterate from (a) to (g) until stable estimates are obtained.

One diffculty in implementing the MCEM algorithm is determining when the parameters have converged. In the analysis for this model, 50 iterations are performed with the total number of values (N) of the posterior distribution beginning low and increasing. This approach is recommended by McCulloch in McCulloch (1997). For this model’s application, N = 500 for iterations 1-10, N = 1000 for iterations 11-20, N = 2500 for iterations 21-30, N = 5000 for iterations 31-40, and N = 10000 for iterations 41-50. The plausibility of this model is examined in the next section. Standard error estimates were obtained using the nonparametric bootstrap. Estimation for the ordinal model with random effects (Model 2R) proceeds in the same fashion, accounting for the K latent classes in implementing the Metropolis algorithm and proportional-odds regression in the M-step.

5 SIMULATION

To verify the performance of our estimation approach, simulation studies were conducted for each of the models.

For each simulation a total of I = 42 and ni = 18 observations were generated (the same size found in the naturalistic driving study) and random covariate values generated using R with a total of 1000 simulations conducted. For each model the true parameter θ, the average parameter estimate for the 1000 simulations , the average asymptotic standard error for the estimates , the sample standard deviation of the estimates , the bias and % bias were computed. Standard error estimates for the marginal models were obtained using Louis (1982) and for the random effects models using the nonparametric bootstrap (Efron and Tibrishani, 1993). True parameter values selected for each model were similar to those found in the analysis to evaluate the robustness of our estimation procedures. The results for the binary latent variable model (Model 1) are shown in Table 4. The majority of model estimates showed very little bias with the exception being the coe cient for the number of acceleration events per mile driven which exhibited slightly higher bias. The results for the ordinal latent variable model (Model 2) and ordinal latent variable model with random effects (Model 2R) are shown in Table 5 and Table 7. These estimates were consistent with true parameter values, exhibiting similar behavior found with the binary latent variable model.

Table 4.

Parameter estimates for Model 1 simulation (N=1000)

| Parameters | θ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α 0 | −7.0 | −6.99 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| α 1 | 2.0 | 2.006 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

| β 0 | −3.0 | −3.04 | 0.20 | 0.19 |

| β 1 | 1.0 | 1.006 | 0.18 | 0.20 |

| β 2 | 3.0 | 3.355 | 2.85 | 2.58 |

| β 3 | 80.0 | 81.80 | 10.30 | 10.65 |

| β 4 | 50.0 | 50.88 | 4.24 | 4.44 |

| β 5 | 5.0 | 5.08 | 1.23 | 1.21 |

| β 6 | 18.0 | 17.79 | 2.61 | 2.20 |

Table 5.

Parameter estimates for Model 2 simulation (N=1000)

| Parameters | θ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α 0 | −7.0 | −6.99 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| α 1 | 2.0 | 2.01 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| α 2 | 4.5 | 4.47 | 0.52 | 0.51 |

| β 01 | 1.3 | 1.27 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| β 02 | 1.8 | 1.79 | 0.18 | 0.17 |

| β 1 | 1 | 1.02 | 0.32 | 0.31 |

| β 2 | 0.0 | 0.07 | 3.72 | 3.73 |

| β 3 | 80.0 | 80.14 | 10.02 | 10.01 |

| β 4 | 45.0 | 46.41 | 4.78 | 4.75 |

| β 5 | 5.0 | 5.09 | 1.91 | 1.93 |

| β 6 | 18.0 | 17.97 | 4.61 | 4.58 |

Table 7.

Parameter estimates for Model 2R simulation (N=200)

| Parameters | θ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α 0 | −7.0 | −7.04 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| α 1 | 2.0 | 2.05 | 0.71 | 0.70 |

| α 2 | 4.5 | 4.46 | 0.58 | 0.56 |

| β 01 | 1.3 | 1.25 | 0.17 | 0.15 |

| β 02 | 1.8 | 1.84 | 0.21 | 0.23 |

| β 1 | 1 | 0.97 | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| β 2 | 0.0 | 0.09 | 3.79 | 3.78 |

| β 3 | 80.0 | 78.37 | 9.98 | 9.95 |

| β 4 | 45.0 | 43.72 | 4.47 | 4.49 |

| β 5 | 5.0 | 4.96 | 1.87 | 1.88 |

| β 6 | 18.0 | 18.10 | 4.65 | 4.67 |

| λ | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.13 |

Simulation results for Model 1R are shown in Table 6. Model run times were several days and limited the number of iterations that could be performed in a reasonable amount of time and required the use of the Biowulf cluster at the National Institutes of Health. A total of 200 simulations were performed), selecting different starting values at the beginning of each simulation. Some small biases exist, but in general the model performed quite well similar to the other models.

Table 6.

Parameter estimates for Model 1R simulations (N=200).

| Parameters | θ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α 0 | −7.0 | −6.97 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| α 1 | 3.0 | 2.98 | 0.24 | 0.23 |

| θ 0 | −3.0 | −2.99 | 0.18 | 0.19 |

| β 1 | 7.0 | 6.89 | 1.11 | 1.10 |

| β 2 | 85.0 | 83.98 | 12.51 | 12.53 |

| β 3 | 50.0 | 51.52 | 6.34 | 6.35 |

| β 4 | 4.0 | 4.16 | 2.10 | 2.10 |

| β 5 | 15.0 | 15.19 | 4.45 | 4.43 |

| λ | 1.0 | 0.98 | 0.22 | 0.22 |

6 AN ALTERNATIVE APPROACH: HIDDEN MARKOV MODEL

An alternative approach to the random effects model is to use a hidden Markov model. The inclusion of the random effect in the previously discussed approaches induces a correlation between latent states bi,j–1 and bi,j. This persistence of the latent state could also be addressed using a hidden Markov approach incorporating covariates in the hidden process. In this section, we outline the hidden Markov approach and its estimation. Results are presented in the following section.

Let (bi1,…,bin) ∈ bi be a binary random vector for an individual where each element of this vector follows a two state Markov Chain (1-‘risky’ driving, 0-‘good’ driving) with no prior knowledge of the transition probabilities = (p01, p10) or the initial state probability distribution ro = {Pr(bij = 0), Pr(bij = 1)}’. A Bernoulli random variable describes the binary CNC outcome Yij and given bi, the following logistic model describes the observed outcomes (Yi1,…,Yin)

Similarly, the transition probabilities are described using the logit transform:

where xij is a vector comprised of kinematic features of interest. We impose a restriction that the initial state be common to all drivers:

Thus, the likelihood we seek to maximize is given by

We evaluate the likelihood above using the forward-backward algorithm A (Baum, et al., 1970) for the E-Step and maximize this result (M-step) using ‘nlm’ in the R package, {stats}.

7 RESULTS

Models 1, 2 and 1R were applied to the NTDS data and are shown in Table 8. In each of the models, we can think of the latent variable as an underlying classification for risky driving behavior. Model 2 is an ordinal model with three latent classes, which in the context of the NTDS represent good, average and poor driving. Intercepts in the proportional odds model for Model 2 result in very little probability in assignment in the middle latent class. Extension to more than three latent classes yielded similar results with the great majority of latent class membership residing in the good or poor classifications and are not shown. Model 1R showed some evidence of heterogeneity in latent class membership (λ = 0.44). This small amount of variation combined with the fixed effects model results and the computational requirement for fitting the random effects model did not warrant investigation of the ordinal random effects model.

Table 8.

Parameter estimates for all models

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1R | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE |

| α0(int) | −8.30 | 0.17 | −10.22 | 0.52 | −8.27 | 0.18 |

| α1(bij) | 2.68 | 0.23 | * | * | 2.77 | 0.20 |

| α2(bij2) | * | * | 1.93 | 0.68 | * | * |

| α3(bij3) | * | * | 4.41 | 0.55 | * | * |

| θ0(int) | −3.27 | 0.21 | * | * | −2.89 | 0.18 |

| θ1 (yi,j–1) | 1.11 | 0.22 | 0.73 | 0.27 | 1.89 | 0.33 |

| γ1(int good/avg) | * | * | 1.38 | 0.16 | * | * |

| γ2(int avg/poor) | * | * | 1.87 | 0.18 | * | * |

| β1 (accel) | 1.26 | 4.54 | −0.01 | 3.77 | 7.76 | 16.84 |

| β2 (decel) | 86.23 | 10.97 | 86.28 | 12.21 | 84.38 | 12.62 |

| β3 (yaw) | 47.39 | 5.67 | 43.48 | 4.99 | 49.29 | 6.32 |

| β4 (lat neg) | 5.72 | 2.16 | 7.32 | 2.12 | 4.11 | 2.09 |

| β5 (lat pos) | 19.08 | 4.80 | 17.52 | 4.53 | 14.42 | 4.41 |

| λ N(0; λ) | * | * | * | * | 0.44 | 0.21 |

Most driving kinematic measures were found to be highly significant in describing the latent state, with the coefficient for accelerations (β1) being the lone exception. For all models, the latent class membership (α1, α2, α3) was highly significant. Kinematic measures for decelerations (β2) and yaw events (β3) had the greatest impact on describing the latent state followed by positive lateral acceleration events (β5) and negative lateral acceleration events (β4). The significance of deceleration, yaw, and lateral acceleration events together shows a strong association exists between risky driving and CNCs for teenage drivers. The previous CNC was positive (θ1) indicating a higher probability of classification in the poor latent state. While somewhat surprising, this result is consistent with most drivers CNCs in that drivers appear to experience several months in succession where a CNC result occurred.

Because prediction was a focus of these models, of particular interest are the posterior mean values {bij = 1|yi} as they relate to crash/near crash events. Figure 1 displays posterior mean values for two drivers: one who exhibits very little driving risk (left side Figure 1) and one with quite risky driving behavior (right side of Figure 1). These results were typical of the drivers in the study; some appeared quite cautious while others took greater risks. The posterior mean values seem to reflect the crash/near crash outcomes appropriately giving us confidence that our predictor is performing well. Given the implementation of MCEM for Model 1R, a likelihood comparison of the three models is not readily available, although a simulated likelihood approach would a ord this. However, models can easily be compared in terms of the differences between observed outcomes and their predictions given by . Latent state probabilities for Model 1R were determined using adaptive Gaussian quadrature. We prefer this method of comparison since our primary interest is the prediction of crash/near crash outcomes. Specifically, the mode for the joint sequence of observations for each individual was determined and quadrature points applied to this model using the determined in the MCEM procedure to adequately capture the likelihood. Model 1R performed best for this measure with a value of (99.87), followed by Model 1 (102.06) and Model 2 (104.56). Models closely followed this ordering with regards to AIC with Model 1 (374.64), and Model 2 (405.96). In terms of prediction, the models performed favorably compared to similar modeling constructs. A similar Markov regression model given by Zeger and Qaqish (1988) is used for comparison, specifically for the driving study

The area under the curve (AUC) for the binary (Model 1) and the binary random effects model (Model 1R) were best with AUC = 0.78(0.041) followed by the three class ordinal model (Model 2) AUC = 0.77(0.040). The Zeger-Qaqish comparison model had an AUC = 0.75(0.038). The ROC curves were constructed using a cross-validation approach where the model is fit leaving one individual out. Standard errors for each of the AUCs (shown in parenthesis) were found using the bootstrap. Figure 2 shows the ROC curves for the binary and ordinal latent variable models compared to the Zeger Qaqish model. The ROC curve for Model 1R was nearly exact to that of Model 1.

Figure 1.

Posterior mean values (∘) and crash/near crash events (+) for two drivers.

Figure 2.

Cross-validated ROC curves for the latent variable models compared to Zeger and Qaqish

Standard error estimates were obtained inverting the numerical approximation to the Hessian matrix of the log-likelihood found using ‘nlm.’ The results shown in Table 9 satisfy our intuition in that the probability of transitioning from a ‘good’ to a ‘poor’ driving state increases with an increase in kinematic measure counts. Similar results hold when the previous crash/near crash outcome is included in describing the transition probabilities. The extended model shown in Table 10 shows that both the latent state bi,j–1 and yi,j–1 play a role in predicting CNC outcomes. This follows since a test of is rejected (p = 0.016).

Table 9.

Hidden Markov model results using composite kinematic measure The hidden Markov model results are shown in Table 9.

| Parameter | Estimate | Std Err |

|---|---|---|

| α 0 | −8.24 | 0.31 |

| α 1 | 2.76 | 0.47 |

| γ 0 | −3.36 | 0.92 |

| γ 1 | 15.15 | 8.70 |

| −0.36 | 0.71 | |

| γ 2 | −7.11 | 12.65 |

| λ | −0.32 | 0.20 |

Table 10.

Hidden Markov model results using composite kinematic measure with previous CNC outcome where logitand logit .

| Parameter | Estimate | Std Err |

|---|---|---|

| α 0 | −8.17 | 0.35 |

| α 1 | 2.72 | 0.45 |

| γ 0 | −3.51 | 0.54 |

| γ 1 | 14.76 | 8.22 |

| −0.78 | 1.03 | |

| β 1 | 2.01 | 0.76 |

| β 2 | −0.50 | 0.31 |

| γ 2 | −9.11 | 12.65 |

| λ | −0.32 | 0.20 |

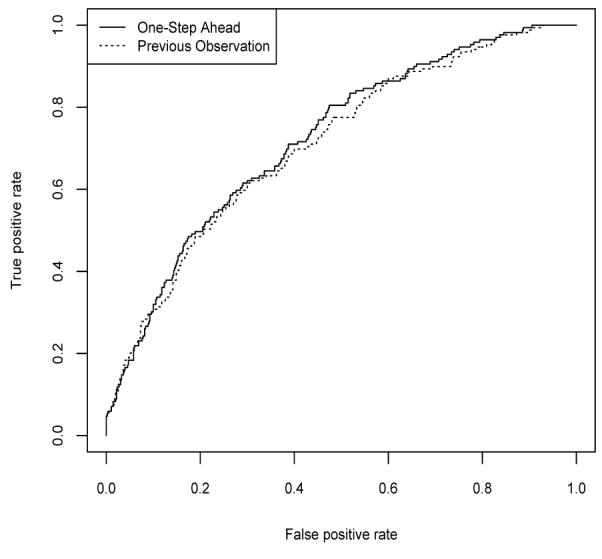

Finally, one can obtain a broad class of predictors using the hidden Markov model approach by conditioning as far into the past as desired. Figure 3 shows the ROC curves based on the previous month’s outcome and all prior outcomes also known as the one-step ahead prediction. The AUC values were similar for both of these predictors with a value of 0.761 (0.032) for the predictor based on the prior month’s outcome and 0.752 (0.034) for the one-step ahead predictor.

Figure 3.

ROC curves for crash/near crash events given the previous CNC outcome Pr(yij = 1|yi,j–1) and the one-step ahead prediction Pr(yij = 1|yi1,…,yi,j–1) using a hidden Markov model.

8 Discussion

In this paper we present a binary latent variable model for predicting binary outcomes in a longitudinal setting. This model was extended to account for multiple ordered latent classes using an ordinal latent variable model. Heterogeneity among subjects’ propensity to be in a particular latent class was introduced for both models. These models were applied to the NTDS data to perform prediction of crash/near crash outcomes as well as determine their association with certain kinematic measures.

The approach used in this paper is useful in several ways. The extent to which risky driving behavior predicts crash likelihood is not well established and our methods better characterize this relationship. They allow us to quantify a persons driving behavior over time using their set of posterior probabilities and in doing so, gives us the potential to detect trends of driving behavior for novice teenage drivers or perhaps more appropriately, their tolerance for risk. This is a significant advantage over models that implement covariates in a direct way such as a traditional conditional model where no such summary measure of driving behavior over time is readily available as part of the analysis. Choosing a binary latent variable construct allows for an analysis in terms of an odds-ratio. Had a continuous latent variable been selected, analysis of this estimate becomes more problematic. It is also not clear that a latent trait model would help with prediction, but this may be the subject of future investigations. Our models’ predictive power compares similarly to the hidden Markov model. However, our approach has the advantage of extending the number of latent classes more easily while still incorporating heterogeneity among subjects. Such an extension to the hidden Markov model is a much more challenging problem requiring implementation of advanced numerical integration techniques. Additionally, the latent model extension to multiple classes can be used to stratify subjects in future intervention studies.

The extension of the binary latent variable model to a model composed of k classes allows the investigator an alternative approach to modeling this type of data. The extension to multiple classes helps in determining the best model for the data (i.e. is the “best” latent state binary, continuous, or somewhere in between). The ordinal latent variable model represents an intermediary between binary and continuous latent variable models. Estimation of the binary and ordinal models (fixed effects) was accomplished using the EM algorithm where, in the maximization step, a weighted regression analysis was used on the factored likelihood. To account for heterogeneity among subjects with regards their propensity to be in a particular latent state, random effects models were introduced for both the binary and ordinal models. The estimation of the random effects model required the use of Monte Carlo EM, which proved to be computationally expensive. A fixed number of iterations were done (50) where a Monte Carlo expectation step and a maximization step using a weighted regression approach were iterated, increasing the number of Monte Carlo samples with each iteration. The suitability of all approaches was examined through simulations performed on each model.

Table 3.

Procedure for finding estimates to Model 2

| 1. Choose initial parameter values α0, θ0, β0 |

| 2. Establish initial weight for each observation |

| 3. Perform proportional odds logistic regression of the latent variable onto the xij according to the model |

| 4. Update parameter estimates for (γ1, γ2, θ1, β1, β2, β3, β4, β5)’ |

| 5. Update weights wijk |

| 6. Perform logistic regression of the response Yij according to the model |

| 7. Update parameter estimates for α0, α1, α2 |

Acknowledgement

We thank the Center for Information Technology, National Institutes of Health, for providing access to the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf cluster computing system. The research of Paul S. Albert, Zhiwei Zhang and Bruce Simons-Morton was supported by the Intramural Research program of the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. We would also like to thank the referees for their thoughtful comments and suggestions which improved our manuscript.

References

- Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Albert PS, Follman DA, Wang SA, Suh EB. A Latent Autoregressive Model for Longitudinal Binary Data Subject to Informative Missingness. Biometrics. 2002;58:631–642. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2002.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolucci F, Lupparelli M, Montanari G. Latent Markov model for longitudinal binary data: an application to the performance evaluation of nursing homes. Annals of Applied Statistics. 2009;3:611–636. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolucci F, Pennoni F. A Class of Laten Markov Models for Capture-Recapture Data Allowing for Time Heterogeneity, and Behavior E ects. Biometrics. 2007;63:568–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2006.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum LE, Petrie T, Soules G, Weiss N. A maximization technique occurring in the statistical analysis of probabilistic functions of Markov chains. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1970;41:164171. [Google Scholar]

- Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum Likelihood Estimation from Incomplete Data via the EM Algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistics Society, Series B. 1977;39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibrishani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman and Hall; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hu ZG, Wong CM, Thach TQ, Lam TH, Hedley AH. Binary latent variable modelling and it application in the study of air pollution in Hong Kong. Statistics in Medicine. 2004;23:667–684. doi: 10.1002/sim.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld PF, Henry NW. Latent Structure Analysis. Houghton Mifflin; New York: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Legler JM, Ryan LM. Latent variable models for teratogenesis using multiple binary outcomes. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1997;92:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Levine RA, Casella G. Implementations of the MCEM algorithm. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2001;10:422439. [Google Scholar]

- Louis Thomas A. Find the Observed Information Matrix when using the EM Algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistics Society. 44:226–233. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald IL, Zucchini W. Hidden Markov and Other Models for Discrete-valued Time Series. Chapman & Hall; London: 1997. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch CE. Maximum Likelihood Algorithms for Generalized Linear Models. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1997;92:162–170. [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration . Traffic Safety Facts 2000: Young Drivers. DOT HS 809 336. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2009. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, URL http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Rasch G. An item analysis which takes individual di erences into account. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 1966;19:48–57. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1966.tb00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, Lerner N, Singler J. The observed e ects of teenage passengers on the risky driving behavior of teenage drivers. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2005;37:973–982. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Qaqish B. Markov Regression Models for Time Series: A Quasi-Likelihood Approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:1019–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]