Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The safety and feasibility of fenestrated/branched endovascular repair of acute visceral aortic disease in high risk patients is unknown. The purpose of this report is to describe our experience with surgeon-modified endografts(sm-EVAR) for the urgent or emergent treatment of pathology involving the branched segment of the aorta in patients deemed to have prohibitively high medical and/or anatomic risk for open repair.

METHODS

A retrospective review was performed on all patients treated with sm-EVAR for acute indications. Planning was based on 3D-CTA reconstructions and graft configurations included various combinations of branch, fenestration, or scallop modifications.

RESULTS

Sixteen patients [mean age(±SD)68±10 years; 88% male] deemed high risk for open repair underwent urgent or emergent repair using sm-EVAR. Indications included: degenerative suprarenal or thoracoabdominal aneurysm (6), presumed or known mycotic aneurysm(4), anastomotic pseudoaneurysm (3), false lumen rupture of type B dissection(2), and penetrating aortic ulceration(1). Nine (56%) had previous aortic surgery and all patients were either ASA class IV(N=9) or IV-E(N=7). A total of 40 visceral vessels (celiac=10, SMA=10, RRA=10, LRA=10) were revascularized with a combination of fenestrations (33), directional graft branches (6), and graft scallops (1). Technical success was 94% (N=15/16), with one open conversion. Median contrast use was 126mL (range 41–245) and fluoroscopy time was 70 minutes(range 18–200). Endoleaks were identified intra-operatively in 4 patients [type II(N=3); IV(N=1)] but none have required remediation. Mean LOS was 12±15 days (median 5.5; range 3–59).

Single complications occurred in 5(31%) patients: brachial sheath hematoma (1), stroke(1), ileus(1), respiratory failure(1), and renal failure(1). An additional patient experienced multiple complications including spinal cord ischemia(1) and multi-organ failure resulting in death(N=1;in-hospital mortality 6.3%). The majority of patients were discharged to home (63%;N=10) or short term rehabilitation units (25%;N=4) while one patient required admission to a long-term acute care (LTAC) setting. There were no re-interventions at a median follow-up of 6.2(range 1–16.1) months. Postoperative CTA was available for all patients and demonstrated 100% branch vessel patency, with 1 type III endoleak pending intervention. There were two late deaths at 1.4 and 13.4 months due to non-aortic related pathology.

CONCLUSIONS

Urgent or emergent treatment of acute pathology involving the visceral aortic segment with fenestrated/branched endograft repair is feasible and safe in selected high-risk patients; however the durability of these repairs is yet to be determined.

Introduction

Despite the evolution of aortic stent graft design, 30–45% of all patients who present with AAA will have unfavorable anatomy to undergo elective endovascular repair with commercially available devices,1, 2 often due to proximity or involvement of the visceral aorta. Good risk patients may tolerate elective, open repair of complex aneurysmal disease extending into the visceral aorta; however, patients with poor cardiac, pulmonary, and/or renal function have >40–70% morbidity and 40–60% peri-operative mortality in the emergent setting3–8. Although significant advancements in anesthetic care, operative technique and post-operative management have occurred, these results have not substantially changed over the past 3 decades8, 9.

Outcomes for thoracoabdominal aortic (TAAA) repair are largely determined by the clinical presentation, with procedures performed emergently being highly correlated with perioperative mortality3, 10–12. The use of “chimney”, “snorkel,” and “periscope” techniques, as well as fenestrated and branched endografts have greatly broadened the management options for patients with aortic disease extending to the visceral segment2, 13–16. As evidenced by the growing body of literature, the use of these techniques is becoming increasingly common, with promising outcomes being reported for patients with highly lethal conditions17–20.

Clinical trials are currently underway for pre-fabricated, customized devices for the visceral aorta, but these require weeks to months to manufacture and thus cannot be used in the emergent setting. Moreover, devices designed for “off-the-shelf” use are also being developed and currently entering clinical trials, but are likely many years from widespread availability21, 22. Due to these limitations, surgeons have used device modification to facilitate treatment of patients who are deemed to be prohibitively high risk for open repair23. The application of these techniques in the urgent or emergent setting remains unproven and poorly represented in the current literature.

This study was performed to determine our outcomes with surgeon-modified, fenestrated and branched endovascular (sm-EVAR) devices in high-risk patients with acute visceral aortic disease.

Methods

Subjects and Database

A retrospective review of our endovascular aortic registry was queried for patients treated with acute pathology approximating or involving the visceral segment of the aorta. Patients treated with sm-EVAR were identified and those treated with “chimney” stents or debranching procedures were excluded. Between January 2010 and July 2012, 16 patients were identified. Indications included symptomatic or ruptured presentations of the following pathologies: TAAA, anastomotic pseudoaneurysm, dissection-related and mycotic aneurysm, as well as penetrating aortic ulceration. Urgent patients were categorized by presence of symptoms defined by a presentation of abdominal, flank and/or back pain that was not attributable to a non-aortic pathology. Emergent presentations were defined by evidence of radiographic rupture and/or hemodynamic lability. This study was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board (#161-2012).

All subjects were initially considered for open repair but subsequently judged to be prohibitively high risk due to the predicted likelihood of experiencing profound morbidity or death with open repair based on a combination of medical co-morbidities24–26 and/or anatomic complexity. Although individualized to each scenario, high-risk anatomic criteria generally included acute complicated dissection, visceral patch pseudoaneurysm and mycotic aneurysm. Medical high risk was defined as patients anticipated being unable to tolerate aortic cross-clamping or open thoracotomy (due to a combination of multiple advanced medical co-morbidities). Significant medical comorbidities were defined based on the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) reporting guidelines26.

Due to the unique constellation of medical and anatomic factors that defined high risk for each patient, there was consensus opinion obtained regarding risk for open repair in each case among the members of the group (Vascular Surgery and/or Cardiovascular Surgery) that open repair was prohibitively high risk. Patients were anticipated to have a reasonable probability of successful endovascular repair, and the patients and/or their families were thoroughly informed of the “off label” nature of this type of repair.

Patient records were reviewed to obtain demographic and medical history, as well as details of case conduct and technical outcome. Pre-operative computed tomograms (CTA) and operative angiograms were reviewed to evaluate aortic anatomy. Although a variety of aortic pathologies were treated, lesion extent was categorized into the Crawford classification according to the reporting standards for thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR)27 in an effort to further highlight the magnitude of the type of open surgical reconstruction that would be required if not completed with endovascular repair, as well as to risk stratify patients for spinal cord ischemia events related to the boundaries of the aortic treatment zones. Patient records were reviewed to capture peri-procedural morbidity. Preoperative SVS comorbidity risk scores were calculated in a manner previously reported (≥8 considered high medical risk)26, 28. The Social Security Death Master File was queried to determine survival.

Pre-operative Planning and Operative Technique

All patients were able to be hemodynamically stabilized at presentation, and admitted to the ICU for resuscitation and patient/family counseling prior to operative intervention. Those with contained rupture were managed with permissive hypotension with a goal mean pressure above 50mmHg, similar to reported descriptions of ruptured aneurysm management29. When time allowed, prophylactic spinal drains were placed selectively based on described guidelines from our group30, and surgeon preference. Subjects were treated using modified Cook (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN,) endografts and customized in the operating room using plans based on a preoperative 3-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of axial imaging (TeraRecon Inc., San Mateo, Calif).

All patients remained hemodynamically stable during induction, and anesthetic preparation was performed concomitantly with graft modification. A two-team approach was used to achieve vascular access while the graft was prepared. Patients were repaired with a variety of endograft configurations including fenestrated/branched “composite” grafts (non-modified Endologix Powerlink at the bifurcation with a surgeon-modified Cook TX2 proximally, N = 1), modified bifurcated grafts(N=1), and fenestrated/branched tube grafts(N=14) with or without a distal bifurcated Zenith device (Figure 1).

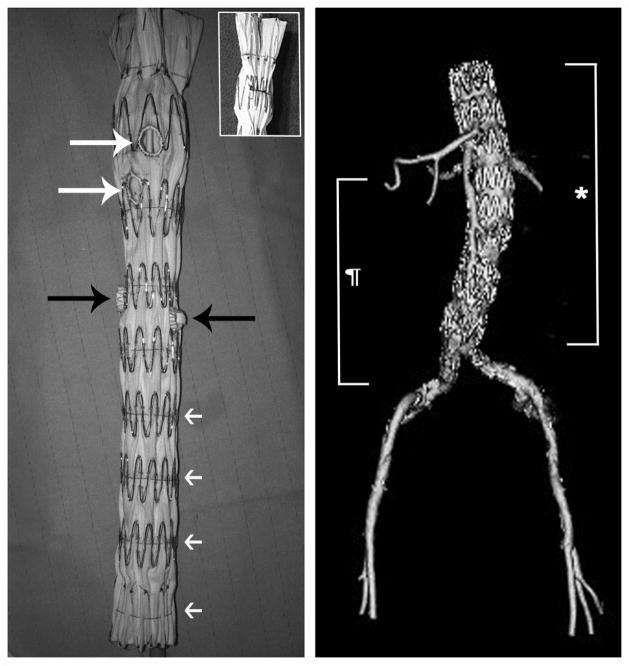

Figure 1.

This image demonstrates a graft used for repair of a suprarenal aneurysm. The graft was modified with two fenestrations (white arrows) for the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries and 2 straight graft branches (black arrows) for the renal arteries. Note the fenestration configuration with a PTFE grommet (Atrium Advanta SST graft) sewn together with a radiographic marker around the perimeter of the fenestration using a Gore suture. The straight graft branches are ~3mm long branches created from a 7mm Gore Viabahn stentgraft and sewn in place with a Gore suture incorporating the base of the branch along with a radiographic marker. Also note the temporary diameter-reducing sutures located at each stent ring, which allows flow through and around the graft during branch vessel catheterization.

This report is not intended to be a technical description of how to perform graft modification, and each graft was highly customized to the patient’s anatomy, so a detailed narrative of each case is beyond the scope and purpose of this analysis. However, various methods of modification were employed in order to accommodate individual anatomy, including combinations of scallops, fenestrations and directional graft branches (Figure 1). As a general rule, fenestrations and scallops were placed in segments of the device that would approximate the aortic wall diameter with full main body deployment, and branches were used when the target vessel was in an aneurysmal segment of the aorta.

The following principles were applied to all modified grafts. The single scallop in this series was made at the distal aspect of a TX2 graft, and was 12mm in depth and 15mm wide. Fenestrations were reinforced with a thin (~1mm) PTFE cuff created from a 6 or 7mm Atrium SST bypass graft (Atrium USA, Hudson, NH) and sewn in place with a CV6 Gore suture (W.L. Gore & Associates, Newark, DE) along with a radiographic marker created from the end of a 0.014 Boston Scientific Thruway™ wire (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA). Directional graft branches were made with their orientation in-line with the direction of the target branch vessel (straight or downward orientations). They were created using a portion of a 6–8mm Gore Viabahn stent-graft (based on the target vessel diameter). Downward branches were secured with a CV6 Gore suture with a radiographic marker at the base, and were oriented such that they would approximate the orientation of the target vessel. Straight branches were typically ~3mm length and placed directly over the site of the target vessel.

Temporary diameter-reducing sutures were placed to allow perfusion through and around the graft into the branch vessels during catheterization. This was achieved using a combined method of a posterior diameter-reducing wire (similar to that described by Oderich31) proximally, and circumferential diameter reduction distally using 5-0 chromic sutures. The proximal sutures were deployed by wire removal, and the distal sutures were opened using a compliant balloon (Cook CODA or Medtronic Reliant), prior to deployment of the stent-grafts used for branch vessel revascularization (Figure 2). Using both the wire-released diameter reduction proximally and the balloon-released reduction distally allowed staged deployment of the endografts to ensure successful branch-vessel revascularization. Cook Zenith infrarenal endografts were also modified in some patients, with posterior diameter reduction achieved using the top cap wire passed through and through the graft in a similar manner as described above.

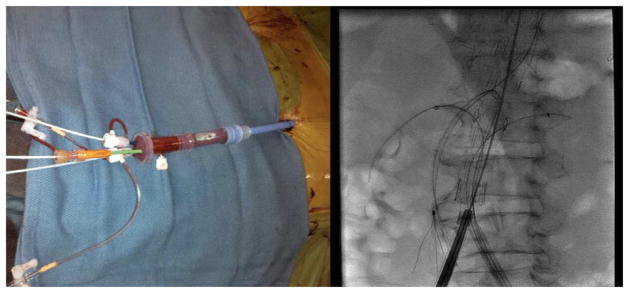

Figure 2.

The left image demonstrates a Gore TAG sheath with multiple smaller sheaths placed through the hub of the device for revascularization of 4 branch vessels. The image on the right demonstrates an endograft within an Extent IV TAAA with 4 target vessels catheterized.

The procedures were performed in a hybrid operating room, and the technique for deployment depended on the strategy of branch vessel revascularization that was employed. For grafts with downward branches, the vessels were revascularized from brachial or axillary access, and generally revascularized one at a time. For fenestrations and straight branches, revascularization was performed via femoral access, and typically access to all of the branch vessels was achieved prior to full graft deployment.

In this series of patients (N=15/16), the majority of femoral access was obtained percutaneously using a “Preclose” technique as described previously32. In selected cases, iliac angioplasty and stent-graft placement were used to create an endovascular conduit to facilitate device entry based on a previously published report33. Branch vessel location was noted with intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and/or aortography. After unsheathing the device, access to the inner portion of the graft was usually obtained from the contralateral femoral artery. In some cases, ipsilateral access was obtained after deployment of the proximal portion of the endograft and removal of the delivery system. In either case, in the event that branches were revascularized from the femoral access, a Gore TAG sheath (20 or 22Fr) was placed within the body of the endograft and used to allow branch vessel access with multiple smaller sheaths (Figure 2).

The preferred visceral branch stent grafts were Atrium iCAST (Atrium Medical Corporation, Hudson, NH). Stent graft length varied and depended on whether the endograft was directly opposed to the aortic wall or not. Stent grafts through fenestrations were deployed such that 3–4mm remained within the lumen of the endograft. The portion of the stent-graft within the target vessel was dilated to the vessel size, and the portion within the aortic lumen was flared using a 10 or 12mm balloon.

Technical success was defined as successful graft deployment into the intended aortic segment(s), with revascularization of all visceral branch vessels, no evidence of extra-anatomic contrast extravasation, and absence of Type I or III endoleak at case completion.

Surveillance Protocol

All patients underwent in-hospital CT angiography postoperatively with images obtained in 2mm increments (including a non-contrasted, arterial-phase, and delayed venous phase) and then followed with a CTA performed using the same protocol at one month. If the patients had no renal dysfunction, follow-up CTAs were performed with the same imaging protocol at 6-months, 12-months and annually thereafter. In the case of non-dialysis dependent renal dysfunction (eGFR<30 mL/min/1.73m2), a non-contrasted CT was performed and supplemented with visceral/renal duplex. CTA was only performed in these patients if aneurysm growth or findings on duplex warranted. Reintervention was defined as any secondary procedure that was performed to treat the initial intended aortic pathology or procedure/device related complications and required a return trip to the operating room.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA software (version 9.2, College Station, Texas). Categorical factors were summarized using frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were described using means, medians, and standard deviations. Categorical variables and continuous measures were compared between groups using Fischer’s exact test or two-sampled t-tests when indicated. Overall patient survival was estimated using Kaplan-Meier methodology. A significance level of 0.05 was assumed for all tests.

Results

Subjects and preoperative characteristics

Between January 2010 and June 2012, 236 patients underwent TEVAR and 125 patients underwent EVAR at the University of Florida. Of those, 16 patients[mean age(±SD) 68±10 years; 88% male(N=14)] were treated with sm-EVAR for acute visceral aortic pathology. All patients remained stable perioperatively and no procedures were abandoned due to hemodynamic lability. Patient demographics, co-morbidities, and pre-operative medication history are shown in Table 1. The mean SVS co-morbidity severity score25, 26 was 12.8±6.3 (≥8 considered high medical risk28).

Table 1. Patient Demographics, Comorbidities and Preoperative Medical Therapy History.

Patient demographics and co-morbid conditions. Note that the mean SVS/AAVS co-morbidity score is 12.8+/− 6.3

| Demographics | N = 16 | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age (±SD) | 68±10 | |

| Gender (male) | 14 | |

|

| ||

| Co-morbidities | ||

|

| ||

| Hypertension | 15 | |

| Smoking/COPD | 11 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 10 | |

| Coronary artery disease | 6 | |

| Chronic renal insufficiency* | 4 | |

| Diabetes | 3 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 3 | |

| Congestive heart failure, EF<40% | 2 | |

| Mean SVS/ISCVS Comorbidity scoreψ | 12.8±6.3 | |

|

| ||

| Medication History | ||

|

| ||

| Antiplatelet therapy | 10 | |

| β-blocker therapy | 4 | |

| Statin therapy | 3 | |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease;

estimated glomerular filtration rate < 50;

Society for Vascular Surgery Reporting Standards22

Anatomic extent of disease is depicted in Table 2. Mean aneurysm diameter was 7.5±1.9cm and indications included a variety of suprarenal or thoracoabdominal aortic pathologies as follows: mycotic paravisceral aneurysm (4), symptomatic and/or ruptured juxta/suprarenal aneurysm (6) or symptomatic and/or ruptured degenerative thoracoabdominal aneurysm (6), and all patients were ASA class IV (N=9) or IV-E (N=7). The majority of patients (56%; N=9) had undergone previous open or endovascular aortic repair at a preoperative median time of 24.1 months(range 1–71). Three patients had undergone prior TEVAR or EVAR and presented with Type Ia/b endoleak.

Table 2. Preoperative Anatomy, Prior Aortic Related Procedures and Clinical Presentation.

Aneurysm extent, prior aortic procedures and patient presentation. Note that 10/16 patients had aneurysms involving both the thoracic and abdominal aorta.

| TAAA Extent | N = 16 | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| II | 1 | |

| III | 4 | |

| IV | 5 | |

| Suprarenal | 5 | |

| Juxtarenal | 1 | |

|

| ||

| Mean aneurysm size (cm) | 7.5±1.9 | |

| Prior Aortic Operations | 9 | |

|

| ||

| TEVAR/EVAR | 3 | |

| TAA/TAAA | 2 | |

| Asc/Arch | 2 | |

| Hybrid (debranching/TEVAR) | 1 | |

| Open AAA | 1 | |

|

| ||

| Operative Indication | ||

|

| ||

| Urgent/Symptomatic | 9 | |

| Rupture | 7 | |

TAA, Crawford thoracoabdominal aneurysm extent23; TEVAR, thoracic aortic endograft repair; EVAR, endovascular infrarenal abdominal aortic repair; Asc/Arch, ascending or transverse arch repair

Operative characteristics and branch vessel data

Details of the branch vessels and specific types of device modifications are outlined in Table 3. Technical success for endograft implantation and branch vessel revascularization was 94%(N=15/16). There were a total of 44 intended target branch vessels with 40 successfully revascularized(91%) including 10 celiac arteries, 10 superior mesenteric arteries, 10 right renal arteries and 10 left renal arteries. One patient accounted for all four failed revascularizations and required conversion to a hybrid debranching procedure, described in detail below.

Table 3. Branch Vessel and Graft Modification Characteristics.

Branch vessel description and revascularization strategies. Of 44 intended target vessels, 40 were successfully revascularized as one patient required open conversion to a hybrid visceral debranching procedure. In general, graft fenestrations were used for vessels in a portion of the aorta where the endograft would approximate the wall of the aorta, and branches were used for vessels in aneurysmal aorta. Permanent diameter reduction was used on grafts landing in significantly smaller distal aorta when compared to the proximal landing zone.

| Branch Vessels Revascularized | N = 40* |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Celiac artery | 10 |

| Superior mesenteric artery | 10 |

| Right renal artery | 10 |

| Left renal artery | 10 |

|

| |

| Type of Graft Modification | |

|

| |

| Fenestration branches | 33 |

| Directional graft branches | 6 |

| Permanent diameter reducing ties | 2 |

| Graft scallop | 1 |

| Stent ring excision | 1 |

44 total vessels were intended to be revascularized; however, one patient required open surgical conversion with an attempted 4-vessel surgeon modified endograft

All procedures were completed under general anesthesia, and preoperative spinal drainage was used in 8(50%) cases. Main body device TX-2 stent graft diameter components ranged from 28–42mm (N=7, 28–34mm;N=9, 36–42mm) and 4 patients required iliac angioplasty and stent graft placement to facilitate endograft delivery. One patient failed percutaneous access, and required an iliofemoral endarterectomy and patch angioplasty.

Median contrast use was 126mL(range 41–245), and median fluoroscopy and procedure times were 70(range 18–200) and 240 minutes(range 134–900), respectively. Comparison of urgent-symptomatic and emergent-ruptured procedures is demonstrated in Table 4, with significant differences noted in time from admission to the operating room, as well as fluoroscopy and contrast exposure. Endoleaks were identified intra-operatively in 3 patients [type II(N=2); IV(N=1)], with none of these requiring remediation to date.

Table 4. Operative Characteristics for Urgent-Symptomatic and Emergent-Ruptured Indications of Suprarenal and Thoracoabdominal Acute Aortic Pathology treated with Surgeon-modified Fenestrated Endografts.

This table demonstrates operative data for urgent versus emergent indications. Not surprisingly, there was a significantly longer admission to repair time in the urgent versus emergent patients.

| Variable | Mean ± SD or No. (%) | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Urg-Symp (n =9) | Emer-Rupt (n =7) | ||

|

|

|||

| Time admission to OR, hrs | 28±11 | 12±9 | .008 |

| Cerebrospinal fluid drain | 6 | 2 | 0.3 |

| OR time, min | 373±225 | 217±86 | 0.1 |

| Flouroscopy time, min | 104±50 | 50±23 | 0.02 |

| Estimated blood loss, mL | 617±900 | 229±57 | 0.3 |

| Crystalloid, liters | 2.0±1.2 | 1.6±0.8 | 0.5 |

| Colloid, mL | 388±253 | 321±345 | 0.7 |

| Packed red blood cells, units | 1.3±1.5 | 0.7±1.2 | 0.4 |

| Contrast exposure, mL | 148±49 | 98±39 | 0.05 |

P-value determined using unpaired t-test and Fischer’s exact test when applicable

Post-operative outcomes

Mean length of stay was 12±15 days (median 5.5; range 3–59). The majority (63%;N=10) of patients were discharged home or short-term rehab (25%;N=4) while one patient required transfer to a long-term acute care(LTAC) facility. There were no 30-day post-operative deaths, but 1 patient died during hospitalization 1.2 months (POD#38) after repair due to multi-system organ failure (in-hospital mortality 6.3%). Table 5 outlines the various complications that occurred. Six patients (38%;N=2, urgent-symptomatic; N=4, emergent-ruptured) had a post-operative complication with one person suffering multiple complications.

Table 5.

Postoperative Outcomes and ¶ Complications

| Feature | N = 16 |

|---|---|

| Length of stay (median, days) | 5.5 |

| In-hospital deathψ | 1 |

| Any complication | 6 |

|

| |

| Open conversion | 1 |

| Brachial sheath hematoma (return to OR) | 1 |

| Retroperitoneal hematoma (return OR) | 1 |

| Stroke (OR for PMTβ) | 1 |

| Iliac dissection (return to OR)ψ | 1 |

|

| |

| Urinary retention | 2 |

| Respiratory failureψ | 2 |

| Renal failure | |

| Without hemodialysis* | 2 |

| Hemodialysis-dependentψ | 1 |

| Spinal cord ischemia (permanent)ψ | 1 |

| Multi-organ failureψ | 1 |

| Colonic ischemiaψ | 1 |

| Any cardiac complication | 0 |

Multiple complications occurred with individual patients;

PMT, pharmacomechanical thrombectomy on POD#0;

Defined as a 25% decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate;

These series of complications occurred in a single patient.

One conversion to a hybrid repair was required while attempting a 4-vessel branched repair of a symptomatic, degenerative Type III TAAA. Due to severe aortic tortuosity, the endograft was inadvertently deformed during placement of a contralateral femoral sheath, effectively closing the branches and making catheterization impossible, and attempts at endovascular salvage were unsuccessful. Of note, the endograft deformation resulted in no visceral or renal malperfusion, and did not complicate the hybrid repair. The patient had a prolonged ICU stay complicated by respiratory failure and ultimately was discharged to a LTAC setting.

The patient who died in-hospital had a symptomatic TAAA associated with a Debakey type IIIb dissection and a SVS comorbidity score of 23. The procedure required a 3-vessel fenestration to revascularize his visceral aortic segment, re-expand his true lumen and seal off a large fenestration in this region of the aorta. Although the aneurysm was repaired successfully, the patient developed multiple complications including spinal cord ischemia, left colon ischemia, multi-system organ failure (including respiratory and hemodialysis dependent renal failure) and eventually care was withdrawn by the family on post-operative day 38.

Follow-up and re-intervention

At a median clinical follow-up time of 6.2(range 1.2–16.1) months one patient required reintervention for a Type III endoleak at an SMA branch graft. This was successfully treated with repeat angioplasty and stent graft extension. Postoperative CTA was available for all patients and demonstrated 100% branch vessel patency. There were no migrations, component separations, fractures, or aneurysm ruptures. For cases of mycotic aneurysm presentations, blood culture positivity was confirmed in 3 of 4 cases (Serratia, E.coli, S.aureus) and all 4 patients were treated with 6 weeks of broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics and then species specific oral suppressive antibiotics for life.

Six patients have reached ≥6 months of follow-up and have imaging available for review. Of these six, aneurysm diameter reduction (≥ 5mm) was noted in 5 of 6 (83%). Three patients had complete aortic remodeling around the stent-graft (Figure 3) and one has a significant type III endoleak at the site of an SMA fenestration now pending endovascular reintervention (Table 6; on-line appendix highlights individual patient outcomes for renal function and aneurysm diameter over the follow-up interval). Estimated 12-month survival after smFEVAR for AAS is 88±0.08% (Figure 4). There were two late deaths (separate from the previously described in-hospital death) at 1.4 and 13.4 months due to non-aortic related pathology (pneumonia resulting in respiratory failure and myocardial infarction).

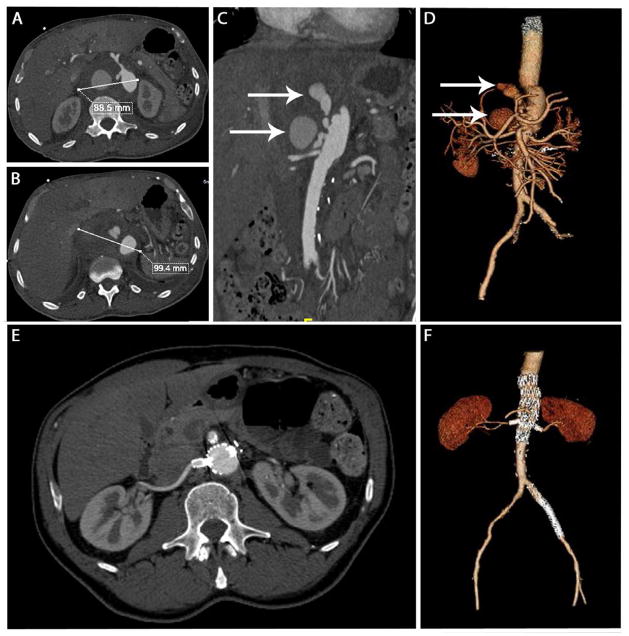

Figure 3.

This panel of images demonstrates pre-operative (top panels) and post-operative images of a patient with a ruptured pseudoaneurysm adjacent to the visceral vessels 4 weeks after an open Extent IV TAAA repair at an outside institution. Panels A, B and C demonstrate images of the preoperative CT demonstrating a large pseudoaneurysm. Panel D is a 3D reconstruction demonsrating the same, with the white arrows in Panels C and D demonstrating the opacified blush within the pseudoaneurysm. The lower panels are corresponding post-operative images at 15 months after repair, which demonstrate complete resolution of the pseudoaneurysm and healing around the stentgraft.

Table 6.

Change in renal function and aortic diameter after surgeon modified fenestrated endovascular repair for acute visceral aortic pathology

| Patient | Clinical Follow-up Time (months) | eGFR change | Change Aneurysm Diameter |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 1 | 13.5 | −9 | −30 |

| 2 | 4.5 | 0 | −2 |

| 3 | 6.9 | 0 | −31 |

| 4 | 14.6 | 0 | −4 |

| 5 | 6.2 | 0 | −1 |

| 6 | 0.2 | −33 | N/A |

| 7 | 2.1 | 0 | −2 |

| 8 | 1.4 | 0 | N/A |

| 9 | 16.1 | −7 | −68 |

| 10 | 4.8 | 0 | −22 |

| 11 | 8.7 | −7 | −4 |

| 12 | 13.1 | −22 | v8 |

| 13 | 2.0 | 0 | N/A |

| 14 | 1.2 | −26 | N/A |

| 15 | 1.8 | 0 | N/A |

| 16 | 1.1 | 0 | N/A |

Only 10 patients had contrasted imaging beyond 6 months postoperatively; Patients highlighted in grey are ones that died; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; N/A, not available; if patients who survived to discharge are analyzed, the average decrease in eGFR after smFEVAR for acute visceral aortic pathology was 5.2±9.8 mL/min/1.73m2. For all patients, the mean±SD decrease in maximal aortic diameter change was 17±21mm.

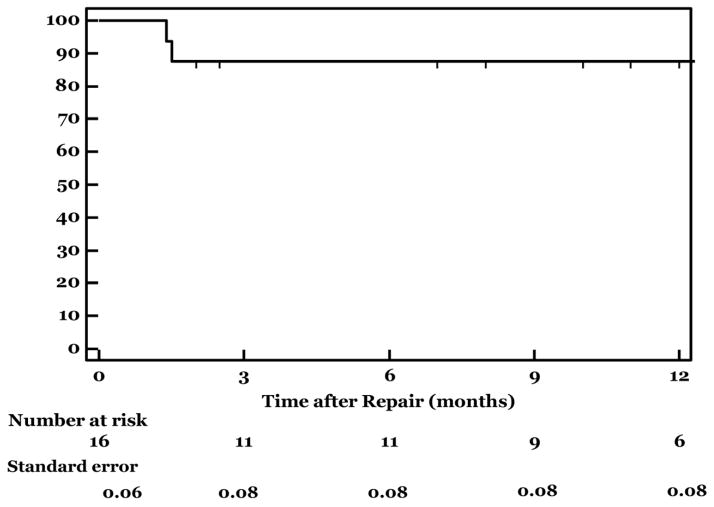

Figure 4. Survival after Surgeon-modified Fenestrated Endograft Repair of Acute Visceral Aortic Emergencies.

This graph demonstrates 12 months survival after smEVAR, which was 88%. One patient died during hospitalization after multiple complications following repair, and 2 patients died of non-aneurysm related conditions at 1.4 and 13.4 months after repair.

Discussion

Although this is a highly selected series of patients, this report demonstrates that branched and fenestrated endografts can be used in urgent or emergent settings with a high degree of technical and clinical success in treatment of complex visceral aortic pathology. Despite these patients being deemed prohibitively high medical/anatomic risk for open repair, a majority not only survived, but were discharged without major morbidity.

Aneurysms involving the visceral segment of the aorta present a challenging clinical scenario, especially in the acute setting in high-risk patients. Historically, patients managed with intact TAAA have been reported to have 10–25% peri-operative mortality9, 34. Despite some improvement in outcomes with elective operations due to advancements in anesthesia, operative techniques, and use of a variety of adjuncts to minimize post-operative morbidity35, these results have not translated into the acute setting. Emergent treatment of ruptured TAAA has a reported mortality in excess of 50% 8, 36, 37. Due to these poor results, surgeons have sought other methods of repair in high-risk patients, such as hybrid debranching procedures. Despite the initial enthusiasm, these techniques have not consistently delivered better outcomes, and many continue to advocate conventional open repair.38–40 Indeed, because of these reports and our own sobering results, we have largely abandoned the use of hybrid visceral debranching as a method to treat high-risk patients.

Although our series is a highly selected patient population given their hemodynamic stability at presentation, they have multiple medical and anatomic factors that make them high-risk. This is evidenced by the patients’ preoperative SVS comorbidity scores, the fact that many had undergone previous open repair, and that all were felt to be prohibitively high risk by a group of experienced surgeons at a tertiary care medical center with a practice that collectively treats approximately 600 aortic patients per year. Notably, 7 of our patients in this series had ruptured thoracoabdominal aortic pathology, and 6 of these 7 (85%) not only survived repair, but were discharged to home or a short-term rehabilitation facility. Despite these promising results, we emphasize that because of the questionable durability of modified stent-grafts, we continue to offer open repair to those patients who are not felt to be prohibitively high risk.

It is anticipated that as fenestrated/branched endograft technology continues to develop, and “off-the-shelf” devices become available, surgeons will be able to treat even good-risk patients with symptomatic or ruptured suprarenal and thoracoabdominal aneurysms. Our results demonstrate that these technologies may provide an excellent alternative to emergent open repair in the future. This correlates well with the literature that has emerged regarding endovascular management of aortic emergencies involving the infrarenal and descending thoracic aorta37, 41. Unfortunately, widespread non-trial availability of these devices is years away, and even with adoption of this technology, there will continue to be patients whose anatomy precludes endovascular repair.

Historically, necessity has encouraged surgeons to develop innovative techniques for treatment of their patients, and many of these methods were initially developed without FDA oversight. Examples of this span surgical history, and include the treatment of emergent aortic disease by Drs. Vorhees and Blakemore with an aortic graft crafted on a sewing machine to treat a ruptured aneurysm42. More recently, Parodi and colleagues43, fashioned “homemade” endovascular devices for the treatment of infrarenal aneurysms43–45. Further examples include the use of “chimney” and “snorkel” techniques to treat aneurysms involving the visceral aorta14, 46, 47, as well as the modification of commercially available devices31, 45. These novel strategies offer promising solutions for high risk patients with complex aortic pathology; however, the modular nature of the fenestrated strategies lends itself to inter-component (e.g. Type III) endoleak while the various snorkel or chimney techniques are at risk of peri-graft ‘gutter’ (e.g. Type I) leak. Given these limitations and we do not advocate the widespread use of these off-label techniques outside of an FDA-approved trial with an investigational device exemption (IDE). However, one can easily imagine various scenarios where patients may benefit from use of off-label techniques, especially in emergent situations where patients are deemed ‘no option’ or prohibitively high open surgical risk. Patients and/or their families in our series were all thoroughly informed of the off-label nature of the repair, and the surgeon took full responsibility for the success or failure of the operation.

There are several important limitations to this study including the fact that this effectively represents an extended case series of a small clinically and anatomically heterogeneous group of patients. Also, this is essentially a single-surgeon, single-center experience, and the results cannot universally be applied. The extensive endovascular experience, inventory and postoperative ancillary support required to successfully treat these patients are unlikely to reproducible in many centers. The significant risk of Type II error, as well as potential over-enthusiasm engendered for graft modification cannot be overstated. The focus of this report is to detail the outcomes of a complex group of patients managed urgently with complex endovascular techniques. The selection bias introduced by procedural planning, methods for intra-operative graft construction and implantation techniques selects for hemodynamically stable patients which undoubtedly facilitates the promising results in this study and further limits procedural applicability. This study was completed without an FDA approved investigational device exemption for graft modification, however the evolution in practice and different types of unique graft modifications (e.g. using fenestration, temporary and permanent diameter reduction sutures and branch grafts within the same device) required to complete repair in a diverse group of aortic pathologies with variable presentations would not necessarily be possible within the constraints of this type of mandate. Despite these limitations, we feel that our results demonstrate that these techniques can be applied selectively with acceptable outcomes.

In conclusion, fenestrated/branched endograft repair can be safely performed for a variety of acute peri-visceral aortic conditions. Longer follow-up and greater patient numbers are needed to determine durability and guide application of these techniques.

Footnotes

Presented at the 25th Annual Meeting of the Florida Vascular Society, Naples, Florida, May 4th, 2012

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Resch TA, Sonesson B, Dias N, Malina M. Chimney grafts: Is there a need and will they work? Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2011;23:149–153. doi: 10.1177/1531003511408339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pecoraro F, Pfammatter T, Mayer D, Frauenfelder T, Papadimitriou D, Hechelhammer L, Veith FJ, Lachat M, Rancic Z. Multiple periscope and chimney grafts to treat ruptured thoracoabdominal and pararenal aortic aneurysms. J Endovasc Ther. 2011;18:642–649. doi: 10.1583/11-3556.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cambria RP, Davison JK, Zannetti S, L’Italien G, Atamian S. Thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair: Perspectives over a decade with the clamp-and-sew technique. Ann Surg. 1997;226:294–303. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199709000-00009. discussion 303-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svensson LG, Crawford ES, Hess KR, Coselli JS, Safi HJ. Experience with 1509 patients undergoing thoracoabdominal aortic operations. J Vasc Surg. 1993;17:357–368. discussion 368–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coselli JS. Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms: Experience with 372 patients. J Card Surg. 1994;9:638–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.1994.tb00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rigberg DA, McGory ML, Zingmond DS, Maggard MA, Agustin M, Lawrence PF, Ko CY. Thirty-day mortality statistics underestimate the risk of repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms: A statewide experience. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.10.070. discussion 223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mastroroberto P, Chello M. Emergency thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair: Clinical outcome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;118:477–481. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70185-6. discussion 481-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowan JA, Jr, Dimick JB, Wainess RM, Henke PK, Stanley JC, Upchurch GR., Jr Ruptured thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm treatment in the united states: 1988 to 1998. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:319–322. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowan JA, Jr, Dimick JB, Henke PK, Huber TS, Stanley JC, Upchurch GR., Jr Surgical treatment of intact thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms in the united states: Hospital and surgeon volume-related outcomes. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:1169–1174. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coselli JS, LeMaire SA, de Figueiredo LP, Kirby RP. Paraplegia after thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair: Is dissection a risk factor? Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:28–35. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(96)01029-6. discussion 35-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox GS, O’Hara PJ, Hertzer NR, Piedmonte MR, Krajewski LP, Beven EG. Thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair: A representative experience. J Vasc Surg. 1992;15:780–787. doi: 10.1067/mva.1992.37087. discussion 787–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conrad MF, Crawford RS, Davison JK, Cambria RP. Thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair: A 20-year perspective. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:S856–861. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.096. discussion S890-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verhoeven EL, Tielliu IF, Bos WT, Zeebregts CJ. Present and future of branched stent grafts in thoraco-abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: A single-centre experience. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruen KJ, Feezor RJ, Daniels MJ, Beck AW, Lee WA. Endovascular chimney technique versus open repair of juxtarenal and suprarenal aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:895–904. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.10.068. discussion 904-895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg RK, Haulon S, Lyden SP, Srivastava SD, Turc A, Eagleton MJ, Sarac TP, Ouriel K. Endovascular management of juxtarenal aneurysms with fenestrated endovascular grafting. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2003.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muhs BE, Verhoeven EL, Zeebregts CJ, Tielliu IF, Prins TR, Verhagen HJ, van den Dungen JJ. Mid-term results of endovascular aneurysm repair with branched and fenestrated endografts. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chuter TA. Branched and fenestrated stent grafts for endovascular repair of thoracic aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43 (Suppl A):111A–115A. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reilly LM, Rapp JH, Grenon SM, Hiramoto JS, Sobel J, Chuter TA. Efficacy and durability of endovascular thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair using the caudally directed cuff technique. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lachat M, Frauenfelder T, Mayer D, Pfiffner R, Veith FJ, Rancic Z, Pfammatter T. Complete endovascular renal and visceral artery revascularization and exclusion of a ruptured type iv thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm. J Endovasc Ther. 2010;17:216–220. doi: 10.1583/09-2925.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rancic Z, Pfammatter T, Lachat M, Hechelhammer L, Frauenfelder T, Veith FJ, Criado FJ, Mayer D. Periscope graft to extend distal landing zone in ruptured thoracoabdominal aneurysms with short distal necks. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:1293–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.11.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nordon IM, Hinchliffe RJ, Manning B, Ivancev K, Holt PJ, Loftus IM, Thompson MM. Toward an “off-the-shelf” fenestrated endograft for management of short-necked abdominal aortic aneurysms: An analysis of current graft morphological diversity. J Endovasc Ther. 2010;17:78–85. doi: 10.1583/09-2895R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ricotta JJ, 2nd, Oderich GS. Fenestrated and branched stent grafts. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2008;20:174–187. doi: 10.1177/1531003508320491. discussion 188-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oderich GS. Reporting on fenestrated endografts: Surrogates for outcomes and implications of aneurysm classification, type of repair, and the evolving technique. J Endovasc Ther. 2011;18:154–156. doi: 10.1583/10-3274C.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jean-Baptiste E, Hassen-Khodja R, Bouillanne PJ, Haudebourg P, Declemy S, Batt M. Endovascular repair of infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms in high-risk-surgical patients. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rutherford RB, Baker JD, Ernst C, Johnston KW, Porter JM, Ahn S, Jones DN. Recommended standards for reports dealing with lower extremity ischemia: Revised version. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26:517–538. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaikof EL, Fillinger MF, Matsumura JS, Rutherford RB, White GH, Blankensteijn JD, Bernhard VM, Harris PL, Kent KC, May J, Veith FJ, Zarins CK. Identifying and grading factors that modify the outcome of endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:1061–1066. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.123991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fillinger MF, Greenberg RK, McKinsey JF, Chaikof EL. Reporting standards for thoracic endovascular aortic repair (tevar) J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:1022–1033. 1033 e1015. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faizer R, DeRose G, Lawlor DK, Harris KA, Forbes TL. Objective scoring systems of medical risk: A clinical tool for selecting patients for open or endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:1102–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Vliet JA, van Aalst DL, Schultze Kool LJ, Wever JJ, Blankensteijn JD. Hypotensive hemostatis (permissive hypotension) for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: Are we really in control? Vascular. 2007;15:197–200. doi: 10.2310/6670.2007.00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feezor RJ, Martin TD, Hess PJ, Jr, Daniels MJ, Beaver TM, Klodell CT, Lee WA. Extent of aortic coverage and incidence of spinal cord ischemia after thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:1809–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.09.022. discussion 1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oderich GS, Ricotta JJ., 2nd Modified fenestrated stent grafts: Device design, modifications, implantation, and current applications. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2009;21:157–167. doi: 10.1177/1531003509351594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee WA, Brown MP, Nelson PR, Huber TS. Total percutaneous access for endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (“preclose” technique) J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:1095–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson BG, Matsumura JS. Internal endoconduit: An innovative technique to address unfavorable iliac artery anatomy encountered during thoracic endovascular aortic repair. Journal of vascular surgery. 2008;47:441–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rectenwald JE, Huber TS, Martin TD, Ozaki CK, Devidas M, Welborn MB, Seeger JM. Functional outcome after thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:640–647. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.119238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conrad MF, Ergul EA, Patel VI, Cambria MR, Lamuraglia GM, Simon M, Cambria RP. Evolution of operative strategies in open thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:1195–1201. e1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crawford ES, Hess KR, Cohen ES, Coselli JS, Safi HJ. Ruptured aneurysm of the descending thoracic and thoracoabdominal aorta. Analysis according to size and treatment. Ann Surg. 1991;213:417–425. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199105000-00006. discussion 425-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehta M, Kreienberg PB, Roddy SP, Paty PS, Taggert JB, Sternbach Y, Hnath J, Ozsvath KJ, Chang BB, Shah DM, Darling RC., 3rd Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: Endovascular program development and results. Semin Vasc Surg. 2010;23:206–214. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel R, Conrad MF, Paruchuri V, Kwolek CJ, Chung TK, Cambria RP. Thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair: Hybrid versus open repair. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiesa R, Tshomba Y, Melissano G, Marone EM, Bertoglio L, Setacci F, Calliari FM. Hybrid approach to thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms in patients with prior aortic surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:1128–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Resch TA, Greenberg RK, Lyden SP, Clair DG, Krajewski L, Kashyap VS, O’Neill S, Svensson LG, Lytle B, Ouriel K. Combined staged procedures for the treatment of thoracoabdominal aneurysms. J Endovasc Ther. 2006;13:481–489. doi: 10.1583/05-1743MR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jonker FH, Trimarchi S, Verhagen HJ, Moll FL, Sumpio BE, Muhs BE. Meta-analysis of open versus endovascular repair for ruptured descending thoracic aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:1026–1032. 1032 e1021–1032 e1022. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.10.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blakemore AH, Voorhees AB., Jr The use of tubes constructed from vinyon n cloth in bridging arterial defects; experimental and clinical. Ann Surg. 1954;140:324–334. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195409000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parodi JC, Palmaz JC, Barone HD. Transfemoral intraluminal graft implantation for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg. 1991;5:491–499. doi: 10.1007/BF02015271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parodi JC, Marin ML, Veith FJ. Transfemoral, endovascular stented graft repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Arch Surg. 1995;130:549–552. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430050099017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jim J, Sanchez LA, Rubin BG. Use of a surgeon-modified branched thoracic endograft to preserve an aortorenal bypass during treatment of an intercostal patch aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:730–733. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hiramoto JS, Chang CK, Reilly LM, Schneider DB, Rapp JH, Chuter TA. Outcome of renal stenting for renal artery coverage during endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:1100–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.11.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee JT, Greenberg JI, Dalman RL. Early experience with the snorkel technique for juxtarenal aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:935–946. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.11.041. discussion 945-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]