Abstract

Diabetic neuropathies consist of a variety of syndromes resulting from different types of damage to peripheral or cranial nerves. Although distal symmetric polyneuropathy is most common type of diabetic neuropathy, there are many other subtypes of diabetic neuropathies which have been defined since the 1800’s. Included in these descriptions are patients with proximal diabetic, truncal, cranial, median, and ulnar neuropathies. Various theories have been proposed for the pathogenesis of these neuropathies. The treatment of most of these requires tight and stable glycemic control. Spontaneous recovery is seen in most of these conditions with diabetic control Immunotherapies have been tried in some of these conditions but are quite controversial.

Keywords: Diabetic, Asymmetric, Neuropathies

INTRODUCTION

Distal symmetric polyneuropathy is most common type of neuropathy associated with diabetes. However, many subtypes of diabetic neuropathies were defined even as early as in the 1800’s.1–4 Included in these descriptions are patients with proximal diabetic neuropathy, truncal neuropathy, limb mononeuropathies and cranial neuropathies (Table 1). Bruns focused further on the entity of proximal diabetic neuropathy.5 Various theories have been proposed for the pathogenesis of these neuropathies. Treatment in most cases tight and stable glycemic control and pain management. A practical approach to the diagnosis and management of asymmetric and focal diabetic neuropathies will be reviewed in this chapter.

TABLE 1.

Clinical Classification of Asymmetric Diabetic Neuropathies

| Asymmetric/Focal and Multifocal Diabetic Neuropathies: |

| Diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexopathy (DLSRP; Bruns-Garland syndrome; diabetic amyotrophy; proximal diabetic neuropathy) |

| Truncal neuropathies (thoracic radiculopathy) |

| Cranial neuropathies |

| Limb mononeuropathies |

Asymmetric/Focal Neuropathies

1. Diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexopathy (DLSRP; diabetic amyotrophy; Bruns-Garland Syndrome; proximal diabetic neuropathy)

The most common, and often misdiagnosed, multifocal asymmetric diabetic neuropathy is the lumbosacral radiculoplexopathy syndrome (DLSRP).6 This disorder has been referred to by many names including proximal diabetic neuropathy, ischemic mononeuropathy multiplex, femoral or femoral-sciatic neuropathy, and most often, diabetic amyotrophy and the “Bruns- Garland syndrome” after the two physicians who first reported this entity.5–21 Bruns first described diabetic patients with asymmetric proximal weakness and pain in 1890.5 Later Garland in the 1950’s used the term diabetic amyotrophy due to the muscle atrophy in the thighs.13 But this term can falsely imply that the primary lesion is on the muscle and therefore we use the term DLSRP.

Clinical Presentation

DLSRP syndrome affects an older group of diabetics, more frequently males, usually over age 50, but occasionally we have seen the syndrome in middle-aged diabetics. Most patients have type 2 diabetes mellitus, however this can occur even in type 1 diabetics. In a series of 27 patients reported by Coppack, 24 patients had type 2 DM and 3 had type 1 diabetes mellitus.22 The development of this neuropathy is often unrelated to glucose control or the duration of glucose intolerance. DLSRP can be the presenting manifestation leading to the initial diagnosis of diabetes.

This neuropathy begins with severe unilateral pain in the back, hip, or thigh which subsequently spreads to the other side within weeks to months.6, 19,22 Patients are frequently misdiagnosed as having a compressive lumbosacral radiculopathy. Some patients undergo unnecessary lumbar surgery despite minor changes on lumbar MRI scan. Given the associated weight loss, patients are often suspected to have a pelvic tumor. Within days to weeks of the pain onset, patients develop weakness in typically proximal and to la lesser extent distal leg muscles.

On examination, there is weakness of hip flexors, adductors and extensors, knee flexors and extensors, and ankle dorsiflexors and plantar flexors of varying degree. Profound atrophy of the thigh and at times distal lower extremity muscles develops. Weakness usually encompasses multiple root or plexus levels and is rarely isolated to an individual root or peripheral nerve. Thus, in cases in which knee extension weakness is prominent and the possibility of a diabetic "femoral neuropathy" is considered, if one looks closely at other L2-L4 muscles either on the neurologic examination or with needle EMG, the disease process can usually be found in these adjacent areas. Similarly, if there is a significant foot drop, there is also usually evidence of involvement in tibial or other L5 innervated muscles, and the process is actually not confined to the peroneal nerve. There is usually distal sensory loss, but this is often indistinguishable from the sensory abnormalities of DSPN, which often is present prior to the development of the radiculoplexopathy. Loss of knee and ankle reflexes is common.

While the condition usually begins in one leg, spread to the other leg within weeks or months is rather frequent. The disorder worsens in a gradually progressive or step-wise manner. Cases have been documented in which there is worsening for 18 months.6 Eventually, the process stabilizes and gradually improves, although the recovery may take many months. In many cases, some degree of permanent weakness may persist (Figure 1) 6.

Figure 1.

From Barohn RJ et al The Bruns-Garland syndrome (diabetic amyotrophy): Revisited 100 years later. Arch Neurol 1991; 48:1130-1135.

In about one third of the cases, weakness spreads to proximal arm muscles and is attributed to cervicobrachial radiculoplexopathy .11,19,23 Approximately 12 % of patients develop thoracic radiculopathy, leading to radiating pain in the chest or abdomen and intercostal muscle weakness.24,25 Respiratory weakness have also been described with this neuropathy.26

Diagnostic workup

Electrophysiologically, nerve conduction study findings may not differentiate DLSRP neuropathy from DSPN except for an asymmetric reduction of the femoral compound muscle action potential amplitudes in unilateral cases. However, the needle EMG reveals abundant fibrillation potentials in weak proximal and distal leg muscles as well as in the lumbosacral paraspinous muscles.6 The CSF protein is often elevated, usually between 60–100 mg/dl, but occasionally as high as 400 mg/dl. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate may be elevated as well, but usually less than 50 mm/hr. MRI with gadolinium may show nerve root enhancement.27

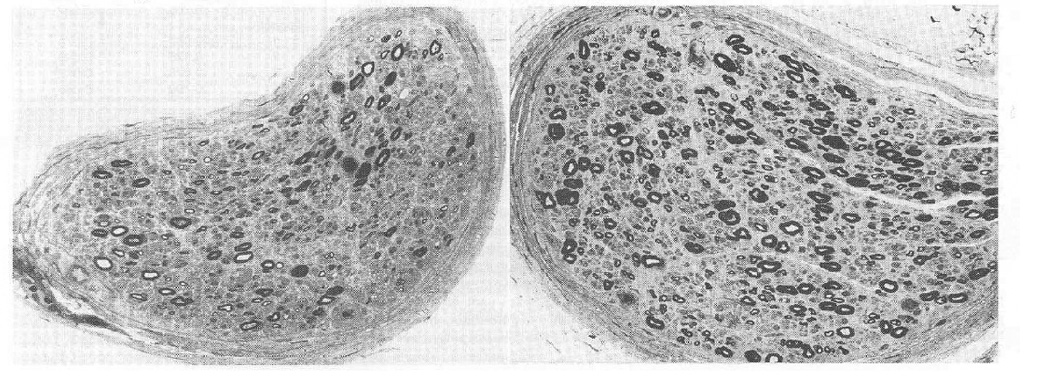

Sural nerve biopsy is not essential to the diagnosis of DLSRP syndrome. When done to exclude mimics, it shows significant fiber loss, often in an asymmetric fashion within and between fascicles, resembling focal ischemia (Figure 2).6,9–11 An ischemic pathogenesis was documented by Raff and colleagues in an autopsy study showing infarcts of proximal nerve trunks of the leg and lumbosacral plexus.7,8 Asymmetric fiber loss in sural nerve may support this theory, however it should be remembered that even patients with typical DSPN may show this multifocal pattern at times. The presence of occasional thinly myelinated fibers on plastic embedded sections or short, thin segments on teased nerve fiber preparations should not lead the physician to diagnose a demyelinating neuropathy as these findings can be seen in DSPN as well. However, it should be emphasized that the electrophysiologic, biopsy, and laboratory features are often not particularly helpful, and the diagnoses of DLSRP is primarily clinically based on the history and neurologic examination

Figure 2.

Cross sections of sural nerve fascicles. 1μm thick. Non random fiber loss is more apparent and more severe in the left than in the right.

From Barohn RJ et al The Bruns-Garland syndrome (diabetic amyotrophy): Revisited 100 years later. Arch Neurol 1991; 48:1130-1135.

There is probably a small subset of diabetic patients with amyotrophy who develop a painless, symmetric proximal neuropathy involving the lower extremities. Ashbury, favoring the term proximal diabetic neuropathy, considered that there was a spectrum ranging from asymmetrical cases with a rapid onset to patient with symmetrical proximal weakness of insidious onset.28 Chokroverty emphasized insidious bilateral onset of proximal weakness29,30. Pascoe et al from published a Mayo clinic series of 44 patients with symmetrical proximal weakness that has a more restricted distribution and seem to be monophasic and self-limiting, differentiating from CIDP. 11. However, the symmetrical presentation seems to be uncommon and tends to occur more often in young Type 1 diabetics who are having poor glycemic control. Therefore, we have divided the proximal diabetic amyotrophies (DAM) into two forms: DAM-1 and DAM-2 (Table 2).31

TABLE 2.

Diabetic Amyotrophy - Two Presentations

| DAM-1 | DAM-2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of DM | Type 1 > 2 | Type 2 > 1 |

| Onset in Legs and Progression | Bilateral/Insidious | Unilateral/Acute |

| Distribution | Symmetric Proximal | Asymmetric Proximal and Distal |

| Pain | No | Yes |

| Sensory Symptoms | No | Yes |

| Poor DM Control | Yes | Yes |

| Weight Loss | Yes | Yes |

| Spontaneous Improvement | Yes | Yes |

| Frequency | Very, very rare | Uncommon -~1% |

| Spread to Arm | Yes -?Common | Yes -10% |

If asymmetric diabetic neuropathies occur in only about 1% of the diabetic population, we think the painless, symmetric form of diabetic amyotrophy (DAM-1) is even more uncommon. This form superficially resembles idiopathic CIDP. We believe that for every 10 – 20 asymmetric/painful amyotrophy patients (DAM-2) seen at a tertiary care neuromuscular centers, only one DAM-1 patient will be seen. Whether or not the pathogenesis of DAM-1 is different from DAM-2 and is more in line with metabolic dysfunction is unknown.

Management

Treatment is centered around pain control and strict glycemic control. Both groups spontaneously improve over a period of months. Physical therapy can assist in improving functional mobility.

Controversy involving DLSRP is whether or not there is an immune-mediated pathogenesis component and if patients respond favorably to immunomodulating therapy. This concept was first introduced by Bradley in 1984 in their report of 6 patients with a painful lumbosacral plexopathy, elevated sedimentation rate, mild perivascular inflammation on sural nerve biopsy, and asymmetric nerve fiber loss.32 Five were treated with immunosuppressive drugs (prednisone alone or prednisone and cyclophosphamide) and 4 improved or stopped progressing. They did not believe the diabetics had typical DLSRP because "they continued to deteriorate and to have pain for several months despite careful control of the diabetes, and only began to improve following treatment with prednisone, although this therapy worsened their diabetes". Thus, Bradley felt the diabetes in their patients was incidental. Of course, others have also reported idiopathic lumbosacral plexitis in non-diabetic patients (analogous to idiopathic brachial plexitis).33,34 Interestingly, in the earlier reports of idiopathic lumbosacral plexitis, patients improved spontaneously. Dr. Bradley's group has advocated the use of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) for idiopathic lumbosacral plexitis.35

Krendal et al (in 1995) reported their experience using immunotherapy in 21 patients with diabetic neuropathy.36 They divided their patients in two groups: Group A consisted of 15 patients who had "multifocal axonal inflammatory vasculopathy" and most of these patients seemed to correspond to what we described above as DLSRP. Group B patients consisted of 6 diabetics who had both arm and leg involvement, and while in 3 the process was asymmetric, the authors stated this group had "demyelinating" neuropathy by electrophysiologic criteria. Group A patients had perivascular inflammation on nerve biopsy and group B patients had "onion bulbs" but no inflammation. All patients received some form of immunomodulatory therapy (15-IVIG; 13-prednisone; 5-cyclophosphamide; 3-plasma exchange, 1-azathioprine) in various combinations, and all improved. Their conclusion was that there are two forms of immunemediated neuropathy in diabetic patients that responds to treatment. Younger and colleagues reported their experience finding evidence of inflammation in 20 patients with diabetic neuropathy - 4 had DSPN, 12 had "proximal diabetic neuropathy", and 4 had mononeuropathy multiplex.37 All patients with proximal diabetic neuropathy and mononeuropathy multiplex had asymmetric features and we would currently consider them as having DLSRP. As noted in the pathogenesis section of the previous chapter, 12/20 had some evidence of inflammatory cells, including 2 with DSPN. They treated 8 patients with IVIG (2 DSPN, 1mononeuropathy multiplex, 5 proximal diabetic neuropathy), all whom had perivascular inflammation, and they reported that all improved.

In the Mayo Clinic group series by Pascoe11, three out of 9 patients undergoing sural nerve biopsy had a multifocal distribution of fiber loss, and 2 had perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates. Twelve were treated with IVIG, and 9 improved. Of the 29 untreated patients, 17 spontaneously improved. They concluded that the "efficacy of immunotherapy is unproven but such intervention may be considered in the severe progressive cases or ones associated with severe neuropathic pain".

The experience of the French group led by Gerard Said is important to note. In a paper published in 1994, they reported inflammatory and ischemic lesions in nerve biopsy specimens of the intermediate cutaneous nerve of the thigh in patients with DLSRP.9 Three patients with "severe and prolonged painful disability" improved dramatically with corticosteroid treatment.

In a subsequent report in 1997 of 4 patients with DLSRP, they described patients who had symptoms for 4, 6 12, and 18 months prior to biopsy.10 While all patients showed perivascular inflammation on nerve biopsy, to the authors surprise, all became pain free with subsequent improvement of their weakness shortly following the biopsy. They concluded that despite the treatment with prednisone they employed in their initial paper, that DLSP "is self-limited and does not require the use of corticosteroids or immunomodulators". In a series by Dyck all 33 DLSRP patients had some evidence of microvasculitis on nerve biopsy, and nearly all improved spontaneously.38 A report by the group from Houston found 18 of 19 DLSRP patients had substantial improvement without immunomodulating therapy.39

Despite many months of persistent symptoms or progression in some patients with DLSRP, eventually all patients spontaneously have resolution of pain and slow improvement of weakness (Figure 1)6. Treatment with IVIG or other immunosuppressive drugs is controversial. In a prospective case series, five patients with severe pain received IVIG after having no response to symptomatic therapy for pain and corticosteroids.40 Four had a decrease in pain. In contrast, Zochodne in 2003 reported a patient who developed DLSRP while on immunosuppressive regimen consisting of cyclosporine and myophenolate mofetil for an allograft cardiac transplant and 2 DLSRP patients who did not response to IVIG treatment,41 arguing that immunosuppressive therapy did not prevent onset of DLSRP. In our opinion, we do not believe IVIG should be used in patients with DLSRP. At this time, we are not convinced that this form of immunomodulating therapy is indicated. Perhaps this question can be resolved with a controlled trial, but such a trial will be difficult as each center sees a handful of patients annually and it will be difficult to get the pharmaceutical industry and the FDA to support a large multi-center IVIG trial in this rare disorder.

On the other hand, the experience of Said and Bradley with the improvement of pain with prednisone should not be ignored. According to recent Cochrane review of immunotherapy for diabetic amyotrophy (DA) only one completed controlled trial using IV methyprednisolone in DA was found.42,43 High doses of corticosteroids may lead to improvement of severe pain in some patients with DLSRP, and this may be analogous to the improvement of neuropathic pain in patients who are believed to have reflex sympathetic dystrophy.44,45 Perhaps breaking the pain syndrome in this manner may subsequently allow patients to begin moving their weak extremities easier. Presently, there is no convincing evidence from randomized trial to support any recommendation on the use of any immunotherapy treatment in DLSRP.42

We believe one should be cautious about jumping to the conclusion that finding mild perivascular inflammation on biopsy, or demyelination features on either electrophysiology or pathology suggest that DLSRP is a disease that is primarily immune-mediated and will respond to immunomodulating therapy. We cautioned above about the danger of heavily relying on electrophysiologic evidence of demyelination on NCS of diabetic patients as some will fulfill research electrophysiologic criteria for CIDP even though the clinical pattern does not correspond to CIDP, but actually is that of DLSRP. Similar caution should be used with data from nerve biopsies of DLSRP patients in concluding these patients have either vasculitis or a demyelinating neuropathy. In routine clinical practice we do not recommend either nerve biopsy or immunomodulating therapy in typical DLSRP patients. Finally, we would also caution clinicians about splitting patients with otherwise typical DLSRP because of nerve root enhancement on lumbar MRI scan.27 If other etiologies are excluded by CSF analysis, the mere finding of root enhancement on MRI in DLSRP should not necessarily lead to the initiation of immunomodulating therapy.

Other DLSRP Caveats

1) Cervical brachial radiculoplexopathy

While cervical/brachial plexus involvement is uncommon, it does occur.11,23 In the classic early Mayo Clinic series of "diabetic polyradiculopathy" reported by Bastron and Thomas in 1981 of 105 patients, 81 had lower extremity involvement, 15 had upper extremity involvement, and 12 had thoracic/abdominal involvement.19 Obviously, a few patients had involvement of more than one region. As mentioned above, in the Mayo Clinic series of Pascoe, all 44 patients had (by definition) leg weakness, and 12 of these also had arm weakness (7 bilateral, 5 unilateral).11 Occasionally, DLSRP patients develop arm pain and weakness days to weeks after the initial leg symptoms.46,47 The arm involvement is usually proximal and distal, similar to the pattern of weakness seen in the legs. Interestingly, the arm symptoms can begin or continue to progress after the leg symptoms have plateaued or begun to improve.

Thus, while cervical/brachial root and plexus involvement has not been emphasized a great deal in diabetic radiculoplexopathy, the clinician should be aware of this possibility. We do believe that in this setting, a more extensive work-up probably is in order to exclude other disease entities. All of these patients should have a CSF examination for infectious and neoplastic diseases, and nerve biopsy is probably warranted to exclude true vasculitic neuropathy.

2) CIDP in diabetic patients

Diabetic patients can develop typical CIDP but as mentioned previously there is no increased risk of CIDP in diabetic patients. 48–51 The clinical features of gradually progressive, usually painless, proximal and distal symmetric weakness and numbness in the arms and legs should be sufficient to distinguish CIDP from the typical symmetric and asymmetric diabetic neuropathies. However, the laboratory results in this setting may not be particularly helpful, especially the CSF protein. If there is an underlying diabetic DSPN on NCS and needle EMG, electrophysiologic results can also be relatively unhelpful unless clear-cut and ample features of an acquired, markedly demyelinating neuropathy are present. In addition, nerve biopsy in many diabetic neuropathies can show thinly myelinated fibers, and therefore we usually do not pursue nerve biopsy in this setting. Diagnosis is usually based on the clinical presentation and it is reasonable to proceed with immunomodulating therapy when CIDP is strongly suspected.

3) True mononeuritis multiplex in diabetes - Does it exist?

Finally, a comment should be made regarding "mononeuritis multiplex" in diabetic patients. We suspect that most of these patients have diabetic radiculoplexopathy, usually lumbosacral, but rarely cervical-brachial. It is uncommon for diabetic patients to develop a true mononeuritis multiplex in which individual distal peripheral nerves (e.g., femoral, peroneal, tibial, ulnar, median or radial) are "picked-off" in a subacute or acute fashion. It is difficult to find good documentation of this in the literature. While the early papers by Raff use the term "mononeuropathy multiplex", if one reads of clinical description of their seven cases, they all had typical DLSRP with proximal and distal involvement not confined to an individual nerve.7, 8 If a diabetic patients develops a true mononeuritis multiplex, the usual causes need to be pursued (vasculitis, infectious, and hereditary). We believe that if one wants to include diabetes mellitus in the differential diagnosis of true mononeuritis multiplex, it should be at the bottom of such a list.

Other Asymmetric Neuropathies

2. Truncal radiculopathy

Another common focal form of diabetic radiculopathy involves isolated thoracic roots.52–55 This is presumably a focal diabetic radiculopathy that is similar to DLSRP except for the location on the trunk - thorax or abdomen.

Clinical presentation

Patients develop abrupt pain over days to weeks with severe dysesthesias in a dermatomal pattern. In some patients, the pain may not radiate entirely around the trunk in a full radicular pattern, but the symptoms and signs may occur in smaller, restricted regions that imply damage of the dorsal or ventral rami or their medial or lateral branches.25 Multiple thoracic dermatomes can be involved. While the majority of cases are unilateral at onset, it can evolve bilaterally, much like DLSRP. In fact, in our experience, it is not uncommon during the evaluation of a patient with typical DLSRP to uncover that at some point over the last year or two the patient had an episode of truncal pain and dysesthesias, or were diagnosed with truncal "shingles" without a rash. Patients can occasionally develop weakness of the rectus abdominus muscles. Some patients may present with pseudohernia due to weakening of the abdominal musculature.52,56

On the other hand, while most patients do not demonstrate obvious motor involvement, needle EMG can reveal abnormalities in the paraspinous or abdominal wall muscles.

Diagnostic workup

Nerve conductions may reveal abnormalities related to distal symmetric polyneuropathy. Needle EMG findings include fibrillations in the paraspinous or abdominal wall muscles.54,57,58

Management

Treatment is directed at symptomatic pain management as discussed in the previous article on DSPN, in this volume. Truncal radiculopathy should be distinguished from the wedge-shaped midline area of symmetric truncal sensory loss that can occur in advanced DSPN53 and from rare discogenic thoracic radiculopathy.

Prognosis

The natural history is similar to DLSRP with persistence of sensory symptoms for weeks to months, with gradual resolution.

3. Cranial neuropathies

Diabetic can suddenly develop a unilateral third, fourth, sixth or seventh cranial nerve palsy. The oculomotor nerve was found to be most frequently affected in one study by Greco looking at 61 patients with diabetic cranial nerve palsies.59 The hallmark of diabetic third nerve palsy is pupillary sparing in most cases.

Clinical presentation

Retro-orbital pain accompanies about half of the cases. Sparing of the pupil in diabetic third nerve palsies is due to sparing of axons at the periphery of the nerve involved in pupillary function. Pathologic evidence supports the concept that the process is probably due to an ischemic watershed phenomenon in the central part of the nerve.60–63

It has been suggested that patients with diabetes are more likely to develop a seventh cranial nerve palsy.64 However, Bell's palsy is a common event and it is difficult to substantiate if it is indeed more prevalent in diabetes.65 It is interesting to note that in the Rochester Diabetic Neuropathy Study, neither cranial mononeuropathies or truncal radiculopathies were more common in the diabetic patients compared to controls66

Diagnostic workup

Imaging studies may be necessary to rule out stroke in some cases. However, history alone without additional testing is sufficient in the majority of these patients.

Management and Prognosis

The main risk factors for the development of cranial neuropthies are duration of diabetes and patient’s age.67 Treatment should be mainly focused on management of diabetes. Most patients make a full recovery, with some early evidence of improvement within 2 to 3 months.

4. Isolated mononeuropathies

Clinical presentation

It is generally believed and established in studies that diabetic individuals are more susceptible to compression injuries compared to non-diabetic individuals.68 This would include the median nerve at the carpal tunnel, ulnar nerve at the elbow, the peroneal (fibular) nerve at the fibular head, and perhaps the lateral cutaneous femoral nerve (meralgia paresthetica) at the hip. In the early study by Mulder69 in 103 cases of diabetes, 16 had mononeuropathies affecting 29 nerves as follows: common peroneal 13; median nerve (carpal tunnel)-9; ulnar nerve - 5; lateral femoral cutaneous nerve - 1; femoral nerve – 1, the latter being likely due to DLSRP. Meralgia Paresthetica (mononeuropathy of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is associated with diabetes mellitus irrespective of obesity and advanced age. 70

In a study from Rochester, Minnesota, there was evidence that carpal tunnel syndrome is more common in diabetes mellitus than in the general population.71 In another Rochester Diabetic Neuropathy Study, approximately one-quarter of patients had subclinical carpal tunnel syndrome on NCS, but only 7.7% were symptomatic.66

Diagnostic workup

Diagnosis is usually established with electrophysiologic testing. However, electrophysiologic diagnosis of carpal tunnel or other mononeuropathies is sometimes difficult in individuals with diabetic polyneuropathy. One study showed segmental and comparative median nerve conduction tests in combination with standard nerve conduction resulted in more accurate diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome in diabetic polyneuropathy patients.72

DIABETIC MUSCLE INFARCTION

In the context of discussing the various diabetic neuropathies, it is relevant to review another neuromuscular complication of diabetes in which the muscle itself is the target organ rather than the nerve. It is an underdiagnosed complication of long standing diabetes.73

Clinical presentation

Diabetic muscle infarction (DMI) begins with the abrupt onset of thigh pain, tenderness, and swelling.74–79 Over a period of days, a firm mass develops in nearly half of cases. The muscles most frequently involved are the vastus lateralis and medialis, thigh adductors, and biceps femoris. Calf involvement is reported in up to 20% of cases and bilateral involvement 8% of cases.80 Compared to 130 cases, there are 5 case reports of DMI affecting muscles of the upper limb of patients particularly in type 2 diabetics with end-stage renal disease.81 Edema from the swelling can extend to the knee and mimic a joint effusion.73 DMI tends to occur in younger, poorly controlled diabetic patients with other end-organ complications. There are no associated systemic symptoms or signs indicative of infection and no skin discoloration suggesting cellulitis or thrombophelebitis. The painful mass persists for weeks, occasionally with exacerbation of symptoms, and then spontaneously resolves over weeks to several months. Contralateral involvement of the other thigh can occur, even after the initial episode resolves. Up to 50% of cases will recur mostly involving previously unaffected muscle groups.80

Diagnostic workup

Creatine kinase can be normal or modestly elevated. Needle EMG demonstrates fibrillation potentials in the involved muscles with a loss of voluntary motor unit potentials in the most affect areas. Remaining motor unit potentials may be brief and short reflecting fragmentation of the motor unit. MRI scan of the limb muscle reveals increased signal on T2- weighted images in the involved thigh muscles indicative of marked muscle edema extending into the perifascicular and subcutaneous tissues (Figure 3).,82,75,76 Gadalonium contrast administration is contraindicated in those with renal impairment. Radionuclide imaging with Technetium-99 demonstrates radiopharmaceutical accumulation and muscle ultrasound shows hyperechoic signal in the mass.76

Figure 3.

From Barohn RJ et al. Case-of-the-month: Painful thigh mass in a young woman: diabetic muscle infarction. Muscle Nerve 1992;15:850-855.

Biopsy of the region consists of large confluent areas of muscle necrosis and edema, with loss of the normal architectural pattern. A muscle biopsy is often not needed because it may prolong recovery and is indicated only when the presentation is atypical, response is poor, or diagnosis is uncertain. Biopsy when performed shows pale muscle on gross examination and areas of muscle necrosis and edema surrounded by muscle fibers in various stages of degeneration and regeneration, with hyalinosis and thickening of arterioles.74

The differential diagnosis of DMI includes in addition to DLSRP, infection (abscess, pyomyositis, necrotizing fasciitis), focal myositis, venous thrombosis, and tumor. Both DMI and DLSRP syndromes begin with the abrupt onset of lower extremity pain that can ultimately involve the opposite side. In DLSRP the pain is usually localized to the low back, hip, or buttocks with radiation into the thigh; while, in DMI, the pain is more focal and associated with swelling and a firm mass. DLSRP patients develop dramatic weakness and atrophy in proximal, and usually distal lower extremity muscles. Sensory symptoms (other than pain) do not result from DMI unless there is a prior distal symmetric polyneuropathy. Whereas the imaging studies of the thigh will be focally abnormal with swelling and infarction in DMI, they may show diffuse denervating changes and atrophy on T2 sequences of the hip, thigh and leg muscles in DLSRP. The EMG in DLSRP is different in that it is characterized by widespread fibrillations in many muscles (usually including the paraspinous muscles), with long-duration, polyphasic motor unit potentials and decreased recruitment pattern. NCS may not be helpful in distinguishing the disorders, as both may show evidence of a distal symmetric polyneuropathy.

While there are obvious differences between DMI and DLSRP (Table 3), the abrupt onset of both syndromes, and pathologic evidence for probable focal ischemia in the muscle (DMI) and nerve (DLSRP) supports the theory that both entities have a primary vascular microangiopathic etiology.

TABLE 3.

Diabetic Lumbosacral Radiculoplexopathy (DLSRP) vs Diabetic Muscle Infarction (DMI)

| DLSRP | DMI | |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | + | + |

| Focally tender | − | + |

| Swelling/mass | − | + |

| Progression | + | + |

| Bilaterally | + | + |

| Atrophy | + | − |

| Distal weakness | + | +/− |

| Sensory symptoms | +/− | − |

| MRI muscle | normal | abnormal |

| EMG | neuropathic | myopathic |

Management and Prognsosis

The treatment of DMI is supportive. No evidence based recommendations are available on management of this condition. However, a retrospective analysis supports conservative management with bed rest, leg elevation and adequate analgesia. Activities should be avoided to avoid increasing the pain. There is no evidence to support the use of corticosteroids or surgery. Short term prognosis is good, but the recurrence rate is high (40%), and recurrences may not affect the same muscle group.83

KEY POINTS.

Diabetic neuropathy presents with varied manifestations including proximal and asymmetric types

Except for entrapments, diabetic amyotrophy is the most common form of asymmetric diabetic neuropathy.

Diabetic amyotrophy can present asymmetrically or symmetrically, with a rapid or insidious onset.

Symmetric form of diabetic amyotrophy can be indistinguishable from CIDP

Treatment of diabetic amyotrophy with IVIG or immunosuppressive drugs is controversial

Truncal radiculopathy can cause abdominal muscle weakness

Diabetics can develop third, fourth, sixth and seventh cranial nerve palsies

Diabetics are more susceptible to compression mononeuropathies than nondiabetics

Muscle infarction can also be seen in diabetics and is clinically distinct from diabetic amyotrophy

Treatment is mostly strict diabetic control and supportive in most of these conditions

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Mamatha Pasnoor, Department of Neurology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS.

Mazen M. Dimachkie, Director, Neuromuscular Section, Department of Neurology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS.

Richard J. Barohn, Department of Neurology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS.

References

- 1.Althaus J. On sclerosis of the spinal cord, including locomotor ataxy, spastic spinal paralysis and other system diseases of the spinal cord: their pathology, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. London: Green & Company; 1885. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leyden E. Entzundung der peripheren Nerven. Deut Militar Zeitsch. 1887;17:49. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auche M. Des alterations des nerfs périphériques. Arch Med Exp Anat Pathol. 1890;2:635. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pryce TD. On diabetic neuritis with a clinical and pathological description of three cases of diabetic pseudo-tabes. Brain. 1893;16:416. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruns L. Ueber neuritische Lahmungen beim Diabetes mellitus. Berl Klin Wochensher. 1980;27:509–515. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barohn RJ, Sahenk Z, Warmolts JR, Mendell JR. The Bruns-Garland syndrome (diabetic amyotrophy): revisited 100 years later. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:1130–1135. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530230038018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raff M, Asbury AK. Ischemic mononeuropathy and mononeuropathy multiplex in diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1968;279:17–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196807042790104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raff MC, Sangalang V, Asbury AK. Ishemic mononeuropathy multiplex associated with diabetes mellitus. Arch Neurol. 1968;18:487–499. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1968.00470350045004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Said G, Goulon-Goeau C, Lacroix C, Moulonguet A. Nerve biopsy findings in different patterns of proximal diabetic neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:559–569. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Said G, Elgrably F, Lacroix C, et al. Painful proximal diabetic neuropathy: inflammatory nerve lesions and spontaneous favorable outcome. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:762–770. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pascoe MK, Low PA, Windebank AJ, Litchy WJ. Subacute diabetic proximal neuropathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:1123–1132. doi: 10.4065/72.12.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garland H, Taverner D. Diabetic myelopathy. Br Med J. 1953;1:405–408. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4825.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garland H. Diabetic amyotrophy. Br Med J. 1955;2:1287–1290. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4951.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Locke S, Lawrence DG, Legg MA. Diabetic amyotrophy. Am J Med. 1963;34:775–785. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(63)90086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calverley JR, Mulder DW. Femoral neuropathy. Neurology. 1960;10:963–967. doi: 10.1212/wnl.10.11.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chokroverty S, Reyes MG, Rubino FA, Tonaki H. The syndrome of diabetic amyotrophy. Ann Neurol. 1977;2:181–194. doi: 10.1002/ana.410020303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chokroverty S. AAEE Case Report #13: Diabetic amyotrophy. Muscle Nerve. 1987;10:679–684. doi: 10.1002/mus.880100803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramony SH, Wilbourn AJ. Diabetic proximal neuropathy. J Neurol Sci. 1982;53:293–304. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(82)90014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bastron JA, Thomas JE. Diabetic polyradiculopathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 1981;56:725–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams IR, Mayer RF. Subacute proximal diabetic neuropathy. Neurology. 1976;26:108–116. doi: 10.1212/wnl.26.2.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asbury AK. Proximal diabetic neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 1977;2:179–180. doi: 10.1002/ana.410020302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coppack SW, Watkins PJ. The natural history of diabetic femoral neuropathy. Q J Med. 1991 Apr;79(288):307–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz JS, Saperstein DS, Wolfe G, et al. Cervicobrachial involvement in diabetic radiculoplexopathy. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:794–798. doi: 10.1002/mus.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Streib EW, Sun SF, Paustian EF, et al. Diabetic thoracic radiculopathy: electrodiagnostic study. Muscle Nerve. 1986;9:548–553. doi: 10.1002/mus.880090612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stewart JD. Diabetic truncal neuropathy: topography of the sensory deficit. Ann Neurol. 1989;25:233–238. doi: 10.1002/ana.410250305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brannagan TH, Promisloff RA, McCluskey LF, Mitz KA. Proximal diabetic neuropathy presenting with respiratory weakness. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:539–541. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.4.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Neil BJ, Flanders AE, Escandon S, Tahmoush AJ. Treatable lumbosacral polyradiculitis masquerading as diabetic amyotrophy. J Neurol Sci. 1997;151:223–225. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)00114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asbury AK. Proximal diabetic neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 1977;2:179–180. doi: 10.1002/ana.410020302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chokroverty S, Reyes MG, Rubino FA, Tonaki H. The syndrome of diabetic amyotrophy. Ann Neurol. 1977;2:181–194. doi: 10.1002/ana.410020303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chokroverty S. AAEE Case Report #13: Diabetic amyotrophy. Muscle Nerve. 1987;10:679–684. doi: 10.1002/mus.880100803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amato AA, Barohn RJ. Diabetic lumbosacral polyradiculoneuropathies. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2001 Mar;3(2):139–146. doi: 10.1007/s11940-001-0049-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bradley WG, Chad D, Verghese JP, et al. Painful lumbosacral plexopathy with elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate: a treatable inflammatory syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1984;15:457–464. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans BA, Stevens JC, Dyck PJ. Lumbosacral plexus neuropathy. Neurology. 1981;31:1327–1330. doi: 10.1212/wnl.31.10.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sander JE, Sharp FR. Lumbosacral plexus neuritis. Neurology. 1981;31:470–473. doi: 10.1212/wnl.31.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verma A, Bradley WG. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in chronic progressive lumbosacral plexopathy. Neurology. 1994;44:248–250. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krendel DA, Costigan DA, Hopkins LC. Successful treatment of neuropathies in patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:1053–1061. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540350039015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Younger DS, Rosoklija G, Hays AP, et al. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of sural nerve biopsies. Muscle Nerve. 1996;19:722–727. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199606)19:6<722::AID-MUS6>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dyck PJB, Novell JE, Dyck PJ. Microvasculitis and ischemia in diabetic lumbosacral radiculopexus neuropathy. Neurology. 1999;53:2113–2121. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lovitt SM, Pleitez MY, Copeland KJ, De Saibro L, Machkas H, Harati Y. Proximal diabetic neuropathy improves spontaneously without expensive and dangerous treatment. Neurology. 2000;54:A212–A213. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tamburin S, Zanette G. Intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy. Med. Pain. 2009 Nov;10(8):1476–1480. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zochodne DW, Isaac D, Jones C. Failure of immunotherapy to prevent, arrest or reverse diabetic lumbosacral plexopathy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003 Apr;107(4):299–301. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.02107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan YC, Lo YL, Chan ES. Immunotherapy for diabetic amyotrophy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Jun;13(6):CD006521. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006521.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dyck PJB, O’Brien P, Bosch EP, Grant I, Burns T, Windebank, et al. The multi-center, double-blind controlled trial of IV methylprednisolone in diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy. Neurology. 2006;66(5 Suppl 2):A191. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kozin F, Ryan LM, Carerra GF, et al. The reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome (RSDS). III. Scitigraphic studies, further evidence for the therapeutic efficacy of systemic corticosteroids, and proposed diagnostic criteria. Am J Med. 1981;70:23–30. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90407-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barohn RJ. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy due to peripheral neuropathy and the threephase bone scan: case series and review. Adv Clin Neurosci (India) 1997;7:129–115. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katz JS, Wolfe GI, Burns D, Bryan WW, Amato AA, Barohn RJ. Diabetic radiculoplexopathy with cervicobrachial involvement. Neurology. 2000;54:A367. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riley DE, Shields RW. Diabetic amyotrophy with upper extremity involvement. Neurology. 1984;34(suppl 1):216. (abs) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cornblath DR, Drach DB, Griffin JW. Demyelinating motor neuropathy in patients with diabetic polyneuropathy. Ann Neurol. 1987;22:126S. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stewart JD, McKelvey R, Durcan L, Carpenter S, Karpati G. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) in diabetics. J Neurol Sci. 1996;142:59–64. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(96)00126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uncini A, De Angelis MV, Di Muzio A, et al. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy in diabetics: motor conductions are important in the differential diagnosis with diabetic polyneuropathy. Clin Neurophys. 1999;110:705–711. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(98)00028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laughlin RS, Dyck PJ, Melton LJ, et al. Incidence and prevalence of CIDP and the association of diabetes mellitus. Neurology. 2009 Jul 7;73(1):39–45. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181aaea47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chiu HK, Trence DL. Diabetic neuropathy, the great masquerader: truncal neuropathy manifesting as abdominal pseudohernia. Endocr Pract. 2006 May-Jun;12(3):281–283. doi: 10.4158/EP.12.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waxman SG, Sabin TD. Diabetic truncal polyneuropathy. Arch Neurol. 1981;38:46–47. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1981.00510010072013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun SF, Streib EW. Diabetic thoracoabdominal neuropathy: clinical and electrodiagnostic features. Ann Neurol. 1981;9:75–79. doi: 10.1002/ana.410090114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Longstretch GF, Newcomer AD. Abdominal pain caused by diabetic radiculopatly. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86:166–186. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-86-2-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parry GJ, Floberg J. Diabetic truncal neuropathy presenting as abdominal hernia. Neurology. 1989;39:1488–1490. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.11.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boulton AMJ, Angus E, Ayyar DR. Diabetic thoracic polyradiculopathy presenting as an abdominal swelling. Br Med J. 1984;289:798–799. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6448.798-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kikta DG, Breuer AC, Wilbourn AJ. Thoracic root pain in diabetes: the spectrum of clinical and electromyographic findings. Ann Neurol. 1982;11:80–85. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Greco D, Gambina F, Pisciotta M, Abrignani M, Maggio F. Clinical characteristics and associated comorbidities in diabetic patients with cranial nerve palsies. J Endocrinol Invest. 2012 Feb;35(2):146–149. doi: 10.3275/7574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Asbury AK, Aldredge H, Herschberg R, Fisher CM. Oculomotor palsy in diabetes mellitus: A clinicopathological study. Brain. 1970;93:555–566. doi: 10.1093/brain/93.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weber RB, Daroff RB, Mackey EA. Pathology of oculomotor nerve palsy in diabetics. Neurology. 1970;20:835–838. doi: 10.1212/wnl.20.8.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dreyfus PM, Hakim S, Adams RD. Diabetic ophthalmoplegia. Arch Neurol Psychiat. 1957;77:337–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith BE, Dyck PJ. Subclinical histopathological changes in the oculomotor nerve in diabetes mellitus. Ann Neurol. 1992;32:376–385. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Korczyn AD. Bell's palsy and diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1971;1:108–109. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)90842-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aminoff MJ, Miller AL. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus inpatients with Bell's palsy. Acta Neurol Scand. 1972;48:381–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1972.tb07558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dyck PH, Kratz KM, Karnes JL, et al. The prevalence by staged severity of various types of diabetic neuropathy, retinopathy, and nephropathy in a population-based cohort: the Rochester diabetic neuropathy study. Neurology. 1993;43:817–824. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ostrić M, Vrca A, Kolak I, Franolić M, Vrca NB. Cranial nerve lesion in diabetic patients. Coll Antropol. 2011 Sep;35(Suppl 2):131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilbourn AJ. Diabetic entrapment and compression neuropathies. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, editors. Diabetic neuropathy. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1999. pp. 481–508. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mulder DW, Lambert EH, Bastrom JA, Sprague RG. The neuropathies associated with diabetes mellitus; a clinical and electromyographic study of 103 unselected diabetic patients. Neurology. 1961;11:275–284. doi: 10.1212/wnl.11.4.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Parisi TJ, Mandrekar J, Dyck PJ, Klein CJ. Meralgia paresthetica: relation to obesity, advanced age, and diabetes mellitus. Neurology. 2011;77(16):1538–1542. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318233b356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stevens JC, Sun S, Beard CM, O'Fallon, Kurland LT. Carpal tunnel syndrome in Rochester, Minnesota, 1961-1980. Neurology. 1988;38:134–138. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gazioglu S, Boz C, Cakmak VA .Electrodiagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome in patients with diabetic polyneuropathy. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011 Jul;122(7):1463–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Trujillo-Santos AJ. Diabetes muscle infarction: an underdiagnosed complication of longstanding diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:211–215. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.1.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Angervall L, Stener B. Tumoriform focal muscle degeneration in two diabetic patients. Diabetologica. 1965;1:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Barohn RJ, Kissel JT. Case-of-the-month: Painful thigh mass in a young woman: diabetic muscle infarction. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15:850–855. doi: 10.1002/mus.880150715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Barohn RJ, Bazan C, Timmons JH, Tegeler C. Bilateral diabetic thigh muscle infarction. J Neuroimaging. 1994;4:43–44. doi: 10.1111/jon19944143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Banker B, Chester S. Infarction of the thigh muscle in the diabetic patient. Neurology. 1973;23:667–677. doi: 10.1212/wnl.23.7.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chester S, Banker B. Focal infarction of muscle in diabetes. Diabetic Care. 1986;9:623–630. doi: 10.2337/diacare.9.6.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Case Records of the MGH. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:839–845. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709183371208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mathew Antony, Sreenath Reddy I, Archibald Colin. Diabetic muscle infarction. Emerg Med J. 2007 Jul;24(7):513–514. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.040071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Joshi R, Reen B, Sheehan H. Upper extremity diabetic muscle infarction in three patients with end-stage renal disease: a case series and review. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009 Mar;15(2):81–84. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31819b9610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jelinek JS, Murphey MD, Aboulafia AJ, Dussault RG, Kaplan PA, Snearly WN. Muscle infarction in patients with diabetes mellitus: MR imaging findings. Radiology. 1999;211:241–247. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.1.r99ap44241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kapur S, McKendry RJ. Treatment and outcomes of diabetic muscle infarction. J Clin Rheumatol. 2005;11:8–12. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000152142.33358.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]