Abstract

Background

Heavy alcohol consumption during pregnancy negatively impacts the physical growth of the fetus. Though the deleterious effects of alcohol exposure during late gestation on fetal brain development are well documented, little is known about the effect on fetal bone mechanical properties or the underlying mechanisms. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of late gestational chronic binge alcohol consumption and alcohol-induced acidemia, a critical regulator of bone health, on functional properties of the fetal skeletal system.

Methods

Suffolk ewes were mated and received intravenous infusions of saline or alcohol (1.75 g/kg) over 1 hour on 3 consecutive days per week followed by 4 days without treatment beginning on gestational day (GD) 109 and concluding on GD 132 (term= 147 days). The acidemia group was exposed to increased inspired fractional concentrations of CO2 to closely mimic the alcohol-induced decreases in maternal arterial pH seen in the alcohol group.

Results

Fetal femurs and tibias from the alcohol and acidemia groups were ~3-7% shorter in length compared to the control groups (P<0.05). Three point bending procedure demonstrated that fetal femoral ultimate strength (MPa) for the alcohol group was decreased (P<0.05) by ~24% and ~29% while the acidemia group exhibited a similar decrease (P<0.05) of ~32% and 37% compared to the normal control and saline control groups, respectively. Bone extrinsic and intrinsic mechanical properties including maximum breaking force (N) and normalized breaking force (N/kg) of fetal bones from the alcohol and acidemia groups were significantly decreased (P<0.05) compared to both control groups.

Conclusions

We conclude that late gestational chronic binge alcohol exposure reduces growth and impairs functional properties of the fetal skeletal system and that the repeated episodes of alcohol-induced maternal acidemia may be at least partially responsible for these effects.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, Teratogenicity, Acidemia, Bone strength

1. Introduction

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) is an umbrella term encompassing the full range of effects that can occur in an individual whose mother consumed alcohol during pregnancy. These include effects on physical, behavioral or cognitive development that can persist as lifelong disabilities, with the most severe end of the spectrum being fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) (Abel, 1984; Streissguth et al., 1980; Warren et al., 2001). Facial abnormalities, growth deficits (whole body and bone), and central nervous system abnormalities are the primary defining diagnostic features of FAS (Riley et al., 2011). In spite of efforts to educate women about the teratogenic effect of alcohol, the prevalence of alcohol consumption in women of child-bearing age remains essentially unchanged over the last four decades (Caetano et al., 2006; CDC, 2004; NIAAA, 2000).

Alcohol is not only a neurotoxic teratogen and has the potential to cause damage in many regions of the brain but also has major detrimental effects on fetal bone development (Simpson et al., 2005; Snow and Keiver, 2007). in rats, maternal alcohol consumption (36% alcohol derived calories) throughout gestation increases maternal bone resorption (Keiver and Weinberg, 2003; Sawant et al., 2012; Washburn et al., 2012), decreases the fetal tibial diaphysis length, disrupts organization of the histological zones within the fetal tibial ephiphyses, decreases the length of the resting zone, and increases the length of the hypertropic zone (Snow and Keiver, 2007). Further, alcohol exposure throughout gestation decreases ovine fetal but not maternal bone strength (Ramadoss et al., 2006), and hampers rat fetal skeletal ossification independent of overall fetal growth restriction (Simpson et al., 2005). No study has yet quantified the effect of late gestational chronic binge alcohol exposure on fetal skeletal extrinsic and intrinsic properties such as maximum bone breaking force (N), normalized maximum bone breaking force (N/kg), cross sectional moment of inertia (CSMI) and ultimate bone strength (MPa). In essence, there is a paucity of studies on the cortical bone mechanical properties during critical windows of vulnerability.

We also wished to address the role of acidemia in alcohol-induced altered fetal cortical bone development, as alcohol exposure in human clinical cases is known to result in mixed respiratory and metabolic acidosis (Lamminpää and Vilska, 1990; 1991; Sahn et al., 1975; Zehtabchi et al., 2005). In animal models, acidemia has been described as a candidate mechanism for alcohol-induced developmental neuronal injury and altered amino acid homeostasis (Cudd et al., 2001; Horiguchi et al., 1971; Ramadoss et al., 2007; 2008b). Although the consequence of these repeated bouts of alcohol-induced acidemia on the skeletal growth of the offspring is unknown, acid base imbalance is known to hamper bone development by altering the bone minerals in order to maintain a stable physiological pH (Arnett, 2003; Barzel, 1995; Bergstrom and Ruva, 1960; Bettice and Gamble, 1975; Bushinsky et al., 1986; 1996; 1999; Green and Kleeman, 1991). Therefore, we hypothesized that late gestation chronic binge alcohol exposure alters bone development as measured by mechanical properties and that these alterations are mediated by acidemia. The beginning of endochondral ossification, an initial process of appendicular bone chondrification, starts during the early gestational period whereas bone remodeling, a lifelong process of simultaneous bone formation and resorption, begins during the mid to late gestational period. This study will specifically evaluate the effect of late gestational chronic binge alcohol-induced acidemia on fetal body growth, and the physical and mechanical properties of the fetal bones.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

The experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Texas A&M University. Suffolk ewes (aged 2–6 years) were mated on gestational day (GD) 0 and maintained outdoors until GD 90 as previously described (Cudd et al., 2001; West et al., 2001). Pregnancies of known date of conception were confirmed, as previously described (Cudd et al., 2001; Ramadoss et al., 2006). On GD 90, the ewes were transferred to an environmentally regulated facility (22°C and a 12:12 light-dark cycle), and they remained there for the duration of the experiments. Animals in all treatment groups were fed 2 kg/day of a “complete” ration (Sheep and Goat Pellet, Producers Cooperative, Bryan, TX) and complete ration was consumed each day by all subjects.

2.2. Surgery protocol

On GD 102 the ewes underwent surgery to implant femoral arterial and venous poly-vinyl chloride catheters (0.05” inner diameter, 0.09” outer diameter) as previously described (Cudd et al., 2001). In brief, anesthesia was induced by administering diazepam (0.2mg/kg intravenously; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) and ketamine (4 mg/kg intravenously, Ketaset®; Fort Dodge, IA). The ewes were intubated and a surgical plane of anesthesia was maintained using isoflurane (0.5% to 2.5% IsoFlo®; Abbott Laboratories) and oxygen. Arterial and venous catheters were advanced into the aorta and vena cava via the femoral artery and vein, respectively. At the end of surgery, the ewe received an injection of flunixin meglumine (1.1 mg/kg intramuscularly, Banamine®; Scherring-Plough, Union, NJ), a prostaglandin synthase inhibitor to reduce postoperative pain. Ewes also received postoperative antibiotics (ampicillin trihydrate, Polyflex® (25 mg/kg administered subcutaneously for 5 days); Aveco, Fort Dodge, IA and gentamicin sulfate, Gentavet® (2 mg/kg administered intramuscularly twice daily for 5 days); Velco, St. Louis, MO.

2.3. Treatment groups

Four treatment groups were used in this study: 1. untreated normal control group (N= 13), 2. saline control group (received 0.9% saline; N= 7), 3. an alcohol group that received alcohol at a dosage of 1.75 g/kg body weight (40% w/v diluted in 0.9% saline; peak blood alcohol concentration 166.64 ± 12.45 mg/dl; N= 15), 4. an acidemia group, where the magnitude and pattern of decreases in maternal arterial pH produced by alcohol was mimicked for the whole exposure period, independent of alcohol by manipulating the inspired fractional concentration of carbon dioxide (received saline in lieu of alcohol; N= 9). Normoxemic conditions were maintained throughout the experiment in the acidemic group. As we have previously reported that third trimester binge alcohol exposure at the dose used in the current study (1.75 g/kg) does not result in fetal hypoxemia (Cudd et al., 2001).

2.4. Experiment protocol

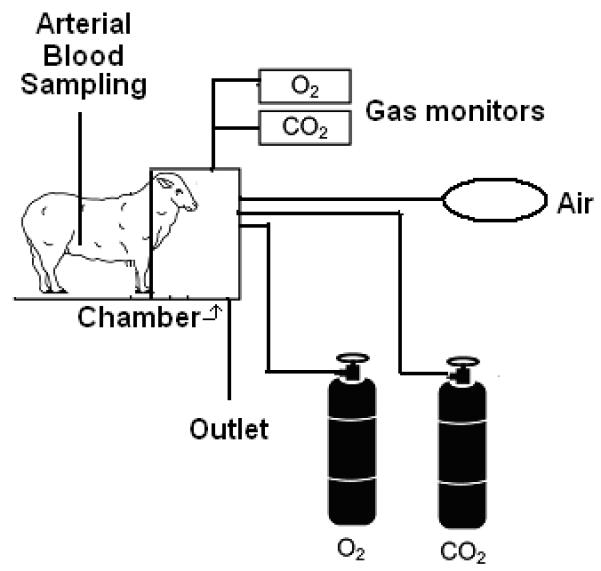

The experiment was conducted on three consecutive days per week, followed by 4 days without treatment, beginning on GD 109 until GD 132 to mimic a weekend binge drinking pattern common in women who abuse alcohol during pregnancy (Maier and West, 2001; Ramadoss et al., 2008a). In all treatment groups, the infusion solutions were delivered intravenously over one hour by peristaltic pump (Masterflex, model 7014-20 Cole Parmer, Niles, IL) and pumps were calibrated before each infusion. On the day of experiment, ewes in all treatment groups were placed in a modified metabolism cart, so that the animal’s head was inside a Plexiglas chamber (Figure 1). A vinyl diaphragm attached to the open side of the chamber was drawn around the animal’s neck to isolate the atmosphere in the chamber from ambient air (Ramadoss et al., 2011). In the acidemia group, subjects were exposed to increased inspired fractional concentrations of carbon dioxide for 6 hours, to create a similar pattern of reduction in maternal arterial pH (pHa) as that produced by alcohol (Table 1) (Cudd et al., 2001). In all other groups, the bottom of the chamber was removed to allow them to breathe room air. Blood was drawn from the maternal femoral arterial catheter on all experiment days at 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 hours from the start of the infusion for pHa analysis using a blood gas analyzer (ABL 5; Radiometer, Weslake, OH). Fold change in the maternal pHa from the baseline (baseline pHa, saline control, 7.47 ± 0.00; alcohol, 7.50 ± 0.00; acidemia, 7.48 ± 0.01) is shown in Table 1. The saline control group was significantly different from the alcohol and acidemia groups at all the time points (P<0.001). There were no differences between the alcohol and acidemia groups at any time point except at 1 and 4 hours. Previously we have shown that late gestational binge alcohol exposure from GD 109 to GD 132 results in maternal as well as fetal acidemia (Cudd et al., 2001), and hence we did not instrument the fetuses in the current study. Maternal blood alcohol concentrations (BACs) were determined as described previously (Cudd et al., 2001; Penton, 1985). On GD 133, the ewes were euthanized using pentobarbital sodium (75 mg/kg IV, Beuthanasia®; Schering-Plough Animal Health). Fetuses were removed from the uterus and fetal body weights and crown-rump lengths were measured and recorded. Fetal femurs and tibias were collected, cleaned, and stored at -20°C. Femoral and tibial lengths, anterior-posterior (AP) and mediolateral diameters (AP) were measured at middiaphyseal region using a precision caliper.

Figure 1. Illustration of the ventilation chamber.

Maternal blood gases in the acidemia group were manipulated by placing the ewe in a chamber and manipulating the inspired gases to mimic the change in maternal arterial pH produced by alcohol. The front half of the subject was confined inside the plexiglass chamber, while the rear half was accessible to the investigator for sampling blood. The fractional concentrations of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the chamber were measured using gas monitors.

Table 1.

Mean (±SEM) fold change in maternal arterial pH at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 hours from the baseline (saline control, 7.47 ± 0.00; alcohol, 7.50 ± 0.00; acidemia, 7.48 ± 0.01).

| Time (hour) | Saline | Alcohol | Acidemia |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1.003 ± 0.002 | 0.990 ± 0.001 a | 0.991 ± 0.001 a |

| 1.0 | 1.004 ± 0.001 | 0.986 ± 0.001 a | 0.979 ± 0.001 a b |

| 1.5 | 1.000 ± 0.001 | 0.987 ± 0.001 a | 0.989 ± 0.001 a |

| 2.0 | 1.006 ± 0.001 | 0.988 ± 0.001 a | 0.988 ± 0.001 a |

| 3.0 | 1.002 ± 0.001 | 0.989 ± 0.001 a | 0.989 ± 0.001 a |

| 4.0 | 1.003 ± 0.001 | 0.992 ± 0.001 a | 0.988 ± 0.001 a b |

| 5.0 | 0.998 ± 0.001 | 0.991 ± 0.001 a | 0.990 ± 0.001 a |

| 6.0 | 1.004 ± 0.001 | 0.995 ± 0.001 a | 0.992 ± 0.001 a |

2.5. Mechanical Testing

Prior to the mechanical testing using a three-point bending procedure, bones were thawed overnight to room temperature. For femur tests, the bones were placed on two lower stationary supports separated by 50 mm distance with the posterior surface of the bone contacting the upper moving contact; for tibia tests the supports were 65 mm apart. The upper moving contact was advanced at a slow, quasistatic displacement rate of 5.08 mm/min (0.2 in/min) until complete fracture of the bone specimen occurred. Three-point bending procedures were conducted on an Instron (Norwood, MA, USA) 1125 load frame with force measured by a load cell attached to the upper contact. The maximum breaking force (N) during the test was recorded for each bone. Maximum breaking force for the individual fetus was normalized by the fetal weight on GD 133 (N/kg). After the three-point bending procedure, a thin cross section of bone was cut adjacent to the point of fracture and a digital image was made. Cross-sectional moment of inertia (CSMI) was calculated from these images using SigmaScan software (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Rectangular CSMI was taken about the ML axis through the centroid of the cross-section and perpendicular to the plane of loading for the bending tests. Ultimate bone strength was estimated using classical beam bending theory equation. Ultimate bone strength (MPa) is S = (FLd)/(8I) where F is the maximum breaking force (N), L the distance between two stationery supports (50 or 65 mm), d is the middiaphysis AP diameter (mm), and I is the rectangular CSMI (mm4).

2.6 Data Analysis

Physical and mechanical properties of the bones were measured using a one-way ANOVA. Further pairwise comparisons were done using Student-Newman-Keuls method. Statistical significance was determined a priori to be P<0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Fetal Growth parameters

There was no significant effect of treatment on fetal whole body weight (kg) on GD 133 (Table 2). Fetal crown-rump length (cm) was significantly different among groups (ANOVA P<0.001). The alcohol and acidemia groups had significantly shorter fetal crown-rump length than the saline control group (↓9%, P=0.003 and ↓11.5%, P<0.001 respectively) but not the normal control group.

Table 2.

Mean (±SEM) fetal whole body weight (kg) and crown-rump length (cm) on GD 133. a and/or b indicate that group is statistically different than the normal control group and/or the saline control group, respectively.

| Group | Fetal Body Weight (kg) |

Fetal Crown-Rump Length (cm) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal Control | 4.83 ± 0.14 | 52.27 ± 0.65 b |

| Saline Control | 4.96 ± 0.62 | 55.50 ± 0.98 a |

| Alcohol | 4.78 ± 0.52 | 50.50 ± 0.86 b |

| Acidemia | 4.19 ± 0.2 | 49.12 ± 0.71 a b |

3.2 Bone Dimensions

3.2.1 Bone Length

Fetal femoral lengths were significantly different among groups (ANOVA, P<0.001) (Table 3). Fetal femurs from the alcohol and acidemia groups were shorter than the normal control (↓4%, P=0.004 and ↓5%, P=0.003 respectively) and the saline control groups (↓6%, P=0.002 and ↓7%, P=0.001 respectively). Fetal tibial lengths were significantly different among groups (ANOVA, P=0.004). Fetal tibias from the alcohol and acidemia groups were shorter than the normal control (↓3%, P=0.043 and ↓5%, P=0.010 respectively) and the saline control groups (↓4%, P=0.056 and ↓6%, P=0.013 respectively) groups. No differences were noted between the normal and saline control groups.

Table 3.

Mean (±SEM) fetal femoral and tibial length, mediolateral (ML) and anterior620 posterior (AP) diameter. a and/or b indicate that group is statistically different than the normal control group and/or the saline control group, respectively.

| Femoral | Tibial | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Group | Length (mm) |

ML Diameter (mm) |

AP Diameter (mm) |

Length (mm) |

ML Diameter (mm) |

AP Diameter (mm) |

| Normal Control | 95.49 ± 0.62 | 10.59 ± 0.12 | 10.11 ± 0.09 | 112.33 ± 0.91 | 10.00 ± 0.09 | 8.49 ± 0.09 |

| Saline Control | 97.59 ± 1.79 | 10.62 ± 0.26 | 9.76 ± 0.25 | 114.08 ± 1.37 | 10.27 ± 0.18 | 8.80 ± 0.16 |

| Alcohol | 91.64 ± 0.75 a b | 9.73 ± 0.15 a b | 9.34 ± 0.14 a | 109.34 ± 1.12 a | 9.14 ± 0.13 a b | 7.84 ± 0.11 a b |

| Acidemia | 90.35 ± 1.59 a b | 9.76 ± 0.18 a b | 9.19 ± 0.22 a | 106.99 ± 1.50 a b | 9.64 ± 0.16 b | 8.18 ± 0.14 b |

3.2.2 Bone Diameters

Fetal femoral mediolateral (ML) and anterior-posterior (AP) diameters (mm) were significantly different among groups (ANOVA, P<0.001) (Table 3). Fetal femoral ML diameter for the alcohol and acidemia groups were smaller than the normal control group (↓8%, P<0.001 and ↓8%, P=0.001 respectively) and the saline control group (↓8%, P=0.009 and ↓8%, P=0.015 respectively). Fetal femoral AP diameter for the alcohol and acidemia groups were smaller than the normal control group (↓8%, P<0.001 and ↓9%, P=0.001 respectively). Fetal tibial ML and AP diameters were significantly different among groups (ANOVA, P<0.001) (Table 3). Fetal tibial ML diameter for the alcohol and acidemia groups were smaller than the normal control group (↓9%, P<0.001 and ↓4%, P=0.064 respectively) and the saline control group (↓11%, P<0.001 and ↓6%, P=0.033 respectively). Fetal tibial AP diameter for the alcohol and acidemia groups were smaller than the normal control group (↓8%, P<0.001 and ↓4%, P=0.082 respectively) and the saline control group (↓11%, P<0.001 and ↓7%, P=0.019 respectively). Fetal tibial ML and AP diameters for the alcohol group were thinner than the acidemia group (↓5%, P=0.011 and ↓4%, P=0.048 respectively). No differences were noted between the normal and saline control groups.

3.2.3 Bone Cross Sectional Moment of Inertia (CSMI)

Neither fetal femoral nor tibial CSMI showed any significant changes among groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean (±SEM) fetal femoral and tibial cross sectional moment of inertia (CSMI). No differences were noted among groups.

| Group | Femoral CSMI (mm4) |

Tibial CSMI (mm4) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal Control | 310.54 ± 15.40 | 197.53 ± 7.71 |

| Saline Control | 303.87 ± 13.92 | 156.93 ± 8.37 |

| Alcohol | 278.38 ± 17.19 | 177.28 ± 12.06 |

| Acidemia | 293.25 ± 15.51 | 208.77 ± 15.98 |

3.3 Mechanical Properties

3.3.1 Extrinsic Properties

3.3.1.1 Maximum Breaking Force

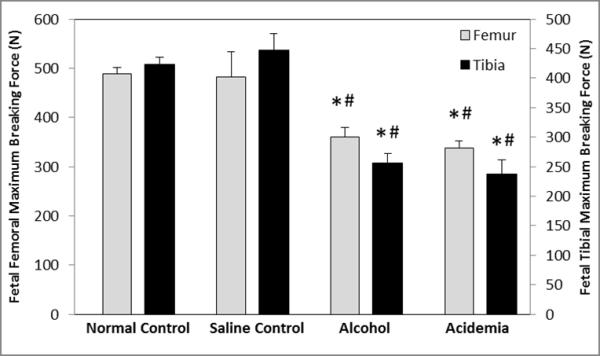

There were significant differences among groups for the fetal femoral and tibial maximum breaking force (ANOVA P<0.001) (Figure 2). Fetal femoral maximum breaking forces for the alcohol and acidemia groups were lower compared to the normal control group (↓26%, P<0.001 and ↓31%, P<0.001 respectively) and the saline control group (↓25%, P=0.001 and ↓30%, P=0.001 respectively). Fetal tibial maximum breaking forces for the alcohol and acidemia groups were lower than the normal control (↓40%, P<0.001 and ↓44%, P<0.001 respectively) and saline control groups (↓43%, P<0.001 and ↓47%, P<0.001 respectively). No differences were noted between the normal and saline control groups.

Figure 2. Binge alcohol and acidemia exposure effects on Fetal Femoral and Tibial Maximum Breaking Force (N).

Fetal femoral and tibial maximum breaking force (N) was significantly reduced in the alcohol and acidemia groups compared to the normal control (*) and saline control (#) groups. Values are means ±SEM.

3.3.2 Intrinsic Properties

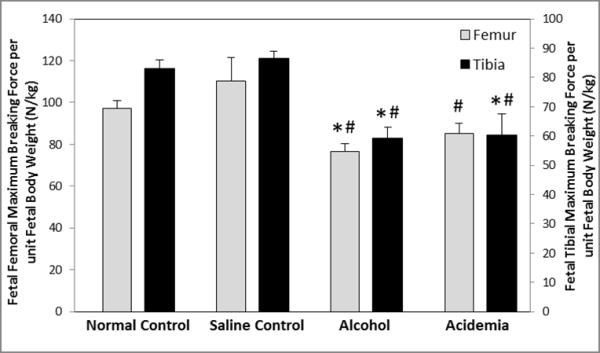

3.3.2.1 Maximum breaking force per unit fetal body weight

Upon normalization by fetal body weight, fetal femoral and tibial maximum breaking force per unit fetal body weight (N/kg) showed significant differences among groups (ANOVA, P<0.001) (Figure 3). Normalized fetal femoral breaking force for the alcohol and acidemia groups were lower than the normal control group (↓21%, P=0.003 and ↓13%, P=0.078 respectively) and were also reduced compared to the saline control group (↓30%, P<0.001 and ↓23%, P=0.017 respectively). Normalized fetal tibial maximum breaking force for the alcohol and acidemia groups were observed to be lower than the normal control group (↓29%, P<0.001 and ↓27%, P=0.002 respectively) and the saline control group (↓32%, P<0.012 and ↓30%, P=0.018 respectively). No differences were noted between the normal and saline control groups.

Figure 3. Binge alcohol and acidemia exposure effects on Fetal Femoral and Tibial Max Breaking Force per Unit Fetal Body Weight (N/kg).

Fetal femoral and tibial maximum breaking force per unit fetal body weight for the alcohol group was significantly lower than the normal control (*) and saline control (#) groups. For the acidemia group, fetal femoral maximum breaking force per unit fetal body weight was significantly lower than the saline control (#) group, and tibial maximum breaking force per unit fetal body weight was significantly lower than the normal control (*) and saline control (#) groups. Values are means ±SEM.

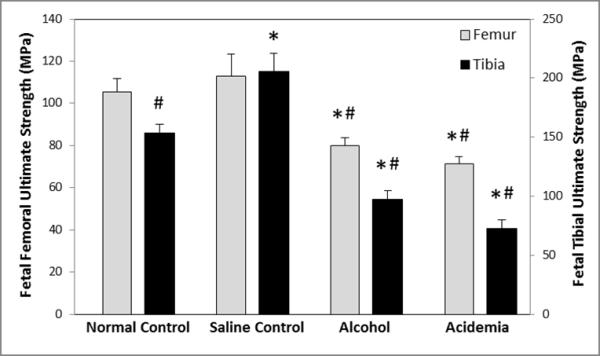

3.3.2.2 Ultimate Bone Strength

Fetal femoral and tibial ultimate strengths (MPa) were significantly different among groups (ANOVA, P<0.001) (Figure 4). Fetal femoral ultimate strengths for the alcohol and acidemia groups were lower than the normal control group (↓24%, P<0.001 and ↓32%, P<0.001 respectively) and the saline control group (↓29%, P=0.003 and ↓37%, P<0.001 respectively). Similar analysis indicated that the fetal tibial ultimate strength for the alcohol and acidemia groups were lower than the normal control (↓37%, P<0.001 and ↓53%, P<0.001 respectively) and saline control groups (↓53%, P<0.001 and ↓65%, P<0.001 respectively). The normal control group exhibited lower fetal tibial strength than the saline control group (↓25%, P=0.001). No differences were noted between the normal and saline control groups for the fetal femoral ultimate strength.

Figure 4. Binge alcohol and acidemia exposure effects on Fetal Femoral and Tibial Ultimate Strength (MPa).

Fetal femoral and tibial bone strength was significantly lower in the alcohol and acidemia group compared to the normal control (*) and saline control (#) groups. Fetal tibial bone strength was significantly different between the normal control and saline control groups. Values are means ±SEM.

4. Discussion

The current study clearly demonstrates the detrimental effects of late gestational chronic binge alcohol consumption on mechanical properties and growth of the fetal bones. Four major findings can be gleaned from this study, the first being that late gestational chronic binge alcohol exposure decreased fetal femoral and tibial ultimate strength. The second notable finding from this study is that developmental alcohol exposure targets both intrinsic and extrinsic bone mechanical properties, leading to decreased fetal femoral and tibial maximum bone breaking force and normalized bone breaking force. Third, the fetal bone growth parameters were compromised after late gestational chronic binge alcohol exposure. Fourth, a decrease in pH in the acidemia group similar to that produced by alcohol results in comparable deficits in growth, extrinsic and intrinsic properties of fetal bones.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively evaluate the mechanical properties of fetal bones after late gestational in-utero chronic binge alcohol exposure. We observed significant decreases in both extrinsic and intrinsic properties of fetal skeletal system including fetal femoral and tibial ultimate strength and normalized maximum breaking force after prenatal binge alcohol consumption during late gestation. In the context of this study, extrinsic properties refer to the whole bone structural properties and intrinsic properties refer to the tissue level material properties (Hogan et al., 1997; Ramadoss et al., 2006). Maximum breaking force and ultimate strength represent different physical attributes of the fetal bones such as, load carrying capacity and material (tissue) level integrity, respectively. Decrease in these mechanical properties of functional fetal bones indicates that alcohol is responsible for disturbing the cortical tissue quality. We did not observe an effect of alcohol on CSMI. These findings support our earlier report that chronic binge alcohol consumption throughout gestation reduces fetal ultimate bone strength and normalized maximum breaking force but not CSMI (Ramadoss et al., 2006).

While the present study evaluate the effect of prenatal alcohol exposure on the functional properties of the fetal bones after in utero alcohol exposure during late gestation, studies in the rodent model highlight potential causes by which alcohol exposure during the developmental period might affect tissue integrity in fetal bones. Alcohol exposure in non-pregnant, four-week-old actively growing rats decreased ultimate femoral cortical strength and maximum breaking force (Hogan et al., 1997), reduced bone density and bone mass in femora and tibiae (Sampson et al., 1996) and stopped tibial epiphyseal growth rate and proliferation (Sampson et al., 1997). Broulik et al. administered alcohol to eight week old rat pups daily for three months, then tested femoral strength and found an approximate 12% reduction (Broulik et al., 2010). Maternal alcohol exposure throughout gestation in the rat disrupted organization of fetal tibial histological zones within the epiphysis (Snow and Keiver, 2007) and a decreased number of ossification centers in the fetal skeleton (Keiver et al., 1997; Simpson et al., 2005). Similarly, In another study, maternal alcohol exposure both prior to and during gestation caused a deprivation in the number of ossification centers in the fetal skull, sternum, limbs and vertebral centra on day 20 of gestation in the rat (Lee and Leichter, 1983). The findings from our study add to this body of works in the rodent model by evaluating the functional properties of fetal bone and a candidate mechanism for damage from in-utero alcohol exposure using a highly translational animal model in which all three human trimester-equivalents of pregnancy occur in utero.

Chronic prenatal binge alcohol consumption paradigm used in this study during late gestation hampered fetal body and bone growth as evidenced by the reduction in fetal crown-rump length, femoral length, femoral Ml diameter, and tibial ML and AP diameters in the alcohol and acidemia groups compared to the saline control group. Our findings are consistent with human clinical cases in which prenatal alcohol exposure leads to a delay in mean bone age (Habbick et al., 1998) and growth restriction in children up to 14 years of age (Day et al., 2002). Studies in rats have also demonstrated that prenatal alcohol exposure reduces fetal body weight and length (Abel and Dintcheff, 1978; Keiver et al., 1997; Keiver and Weinberg, 2004; Simpson et al., 2005). Our results are also in agreement with previous findings in sheep (Ramadoss et al., 2006) and with reports that maternal alcohol consumption throughout the 21 days of gestation in the rat decreases fetal bone and diaphysis length (Snow and Keiver, 2007). In addition, McMechan et al. (2004) observed a decrease in rat forepaw digit length on postnatal day 31 following prenatal alcohol exposure from GD 8 to 20. Collectively, all of these studies in the human, sheep and rat support our current findings that prenatal alcohol exposure during late gestational period decreases fetal crown rump length and bone growth parameters. Our findings show that a decrease in pH in the acidemia group similar to that produced by alcohol leads to comparable deficits in mechanical properties of the fetal skeletal system. Bone dimensions, and extrinsic as well as intrinsic parameters of the fetal bones from the acidemia group were reduced compared to both the saline and normal control groups, but no differences were observed between the alcohol and acidemia group. Both in-vivo and in-vitro studies have demonstrated that in response to acidosis, bones play a vital role in the maintenance of a stable pH, but it is at the expense of bone mineral content (Arnett and Spowage, 1996; Barzel, 1995; Bushinsky et al., 1996; Green and Kleeman, 1991). In response to an extracellular acidic environment, the bone surface loses intracellular sodium and potassium in exchange for hydrogen ions to restore normal extracellular H+ concentration (Bergstrom and Ruva, 1960; Bettice and Gamble, 1975; Bushinsky et al., 1986). Metabolic acidosis also causes the loss of calcium, phosphate and bicarbonate from femoral midcortical region in exchange for H+ to exhibit the proton buffering capacity of bone, as demonstrated in postweanling mice (Bushinsky et al., 1999). Renal tubular acidosis affects bone development in infants and children (McSherry, 1978; McSherry and Morris, 1978), and inhibition of growth hormone secretion may be one of the mechanisms underlying acidosis-induced restriction of bone development (Challa et al., 1993). Acidosis also increases the osteoclast activity by stimulating the release of osteoclastic enzyme β- glucuronidase and inhibits osteoblastic activity by inhibiting osteoblastic collagen synthesis and blocking alkaline phosphatase (Krieger et al., 1992). The findings from these studies on the effects of acidemia on bone together with the results from our study make a compelling case that acidemia is an important candidate mechanism for prenatal alcohol-induced bone deficits.

Perspectives and Significance

Although the overall conformation of adult bone is determined by number of factors, fetal programming during gestation may affect bone adaptation during adulthood in response to the mechanical stress of weight and applied load. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the long-term biomechanical properties of human bones are unknown. The current report demonstrates that late gestational binge alcohol exposure hampers growth and mechanical properties of the fetal skeletal system and these alterations are mediated, at least in part, by alcohol-induced decreases in pH. In addition to shedding light on the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the developing bone functional properties, these data also guide further scientific exploration of early developmental origins of adult bone disorders.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the important role of the late Dr. Timothy Cudd in starting this study and making significant contributions.

We would like to thank Emilie Lunde, Brittney Kramer, Justin Box and Yasaman Shirazi for their assistance in this study.

This research was supported by NIAAA Grant AA10940 and K08AA18166 (SEW), and AA19446 (JR).

Footnotes

All authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abel EL. Prenatal effects of alcohol. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1984;14:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(84)90012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel EL, Dintcheff BA. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on growth and development in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1978;207:916–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett T. Regulation of bone cell function by acid-base balance. Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62:511–520. doi: 10.1079/pns2003268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett TR, Spowage M. Modulation of the resorptive activity of rat osteoclasts by small changes in extracellular pH near the physiological range. Bone. 1996;18:277–279. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzel US. The skeleton as an ion exchange system: implications for the role of acid-base imbalance in the genesis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:1431–1436. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650101002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom WH, Ruva FD. Changes in bone sodium during acute acidosis in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1960;198:1126–1128. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1960.198.5.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettice JA, Gamble JL., Jr Skeletal buffering of acute metabolic acidosis. The Am J Physiol. 1975;229:1618–1624. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1975.229.6.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broulík PD, Vondrová J, Růzicka P, Sedlácek R, Zíma T. The effect of chronic alcohol administration on bone mineral content and bone strength in male rats. Physiol Res. 2010;59:599–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushinsky DA, Chabala JM, Gavrilov KL, Levi-Setti R. Effects of in vivo metabolic acidosis on midcortical bone ion composition. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:F813–819. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.5.F813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushinsky DA, Gavrilov K, Stathopoulos VM, Krieger NS, Chabala JM, Levi-Setti R. Effects of osteoclastic resorption on bone surface ion composition. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C1025–1031. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.4.C1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushinsky DA, Levi-Setti R, Coe FL. Ion microprobe determination of bone surface elements: effects of reduced medium pH. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:F1090–1097. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1986.250.6.F1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Floyd LR, McGrath C. The epidemiology of drinking among women of child-bearing age. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1023–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Alcohol consumption among women who are pregnant or who might become pregnant—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:1178–1181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challa A, Krieg RJ, Jr, Thabet MA, Veldhuis JD, Chan JC. Metabolic acidosis inhibits growth hormone secretion in rats: mechanism of growth retardation. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:E547–553. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.265.4.E547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudd TA, Chen WJ, Parnell SE, West JR. Third trimester binge ethanol exposure results in fetal hypercapnea and acidemia but not hypoxemia in pregnant sheep. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:269–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day NL, Leech SL, Richardson GA, Cornelius MD, Robles N, Larkby C. Prenatal alcohol exposure predicts continued deficits in offspring size at 14 years of age. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1584–1591. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000034036.75248.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J, Kleeman CR. Role of bone in regulation of systemic acid-base balance. Kidney Int. 1991;39:9–26. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habbick BF, Blakley PM, Houston CS, Snyder RE, Senthilselvan A, Nanson JL. Bone age and growth in fetal alcohol syndrome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1312–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan HA, Sampson HW, Cashier E, Ledoux N. Alcohol consumption by young actively growing rats: a study of cortical bone histomorphometry and mechanical properties. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:809–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi T, Suzuki K, Comas-Urrutia AC, Mueller-Heubach E, Boyer-Milic AM, Baratz RA, Morishima HO, James LS, Adamsons K. Effect of ethanol upon uterine activity and fetal acid-base state of the rhesus monkey. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;109:910–917. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(71)90806-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiver K, Ellis L, Anzarut A, Weinberg J. Effect of prenatal ethanol exposure on fetal calcium metabolism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:1612–1618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiver K, Weinberg J. Effect of duration of alcohol consumption on calcium and bone metabolism during pregnancy in the rat. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1507–1519. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000086063.71754.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiver K, Weinberg J. Effect of duration of maternal alcohol consumption on calcium metabolism and bone in the fetal rat. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:456–467. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000118312.38204.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger NS, Sessler NE, Bushinsky DA. Acidosis inhibits osteoblastic and stimulates osteoclastic activity in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:F442–448. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.262.3.F442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamminpää A, Vilska J. Acute alcohol intoxications in children treated in hospital. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1990;79:847–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1990.tb11564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamminpää A, Vilska J. Acid-base balance in alcohol users seen in an emergency room. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1991;33:482–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Leichter J. Skeletal development in fetuses of rats consuming alcohol during gestation. Growth. 1983;47:254–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier SE, West JR. Drinking Patterns and Alcohol-Related Birth Defects. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25:7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMechan AP, O’Leary-Moore SK, Morrison SD, Hannigan JH. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on forepaw digit length and digit ratios in rats. Dev Psychobiol. 2004;45:251–258. doi: 10.1002/dev.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSherry E. Acidosis and growth in nonuremic renal disease. Kidney Int. 1978;14:349–354. doi: 10.1038/ki.1978.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSherry E, Morris RC., Jr Attainment and maintenance of normal stature with alkali therapy in infants and children with classic renal tubular acidosis. J Clin Invest. 1978;61:509–527. doi: 10.1172/JCI108962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIAAA . Tenth Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, MD: 2000. Underlying mechanisms of alcohol-induced damage to the fetus; pp. 285–322. [Google Scholar]

- Penton Z. Headspace measurement of ethanol in blood by gas chromatography with a modified autosampler. Clin Chem. 1985;31:439–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadoss J, Hogan HA, Given JC, West JR, Cudd TA. Binge alcohol exposure during all three trimesters alters bone strength and growth in fetal sheep. Alcohol. 2006;38:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadoss J, Lunde ER, Ouyang N, Chen WJ, Cudd TA. Acid-sensitive channel inhibition prevents fetal alcohol spectrum disorders cerebellar Purkinje cell loss. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008a;295:R596–603. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90321.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadoss J, Lunde ER, Piña KB, Chen WJ, Cudd TA. All three trimester binge alcohol exposure causes fetal cerebellar purkinje cell loss in the presence of maternal hypercapnea, acidemia, and normoxemia: ovine model. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1252–1258. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadoss J, Stewart RH, Cudd TA. Acute renal response to rapid onset respiratory acidosis. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;89:227–231. doi: 10.1139/Y11-008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadoss J, Wu G, Cudd TA. Chronic binge ethanol-mediated acidemia reduces availability of glutamine and related amino acids in maternal plasma of pregnant sheep. Alcohol. 2008b;42:657–666. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley EP, Infante MA, Warren KR. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: an overview. Neuropsychol Review. 2011;21:73–80. doi: 10.1007/s11065-011-9166-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahn SA, Lakshminarayan S, Pierson DJ, Weil JV. Effect of ethanol on the ventilatory responses to oxygen and carbon dioxide in man. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1975;49:33–38. doi: 10.1042/cs0490033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson HW, Chaffin C, Lange J, DeFee B., 2nd Alcohol consumption by young actively growing rats: a histomorphometric study of cancellous bone. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:352–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson HW, Perks N, Champney TH, DeFee B., 2nd Alcohol consumption inhibits bone growth and development in young actively growing rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1375–1384. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawant OB, Lunde ER, Washburn SE, Chen WJ, Goodlett CR, Cudd TA. Different patterns of regional Purkinje cell loss in the cerebellar vermis as a function of the timing of prenatal ethanol exposure in an ovine model. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2012 Nov 26; doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2012.11.001. pii: S0892-0362(12)00174-2. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2012.11.001. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson ME, Duggal S, Keiver K. Prenatal ethanol exposure has differential effects on fetal growth and skeletal ossification. Bone. 2005;36:521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow ME, Keiver K. Prenatal ethanol exposure disrupts the histological stages of fetal bone development. Bone. 2007;41:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.04.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Landesman-Dwyer S, Martin JC, Smith DW. Teratogenic effects of alcohol in humans and laboratory animals. Science. 1980;209:353–361. doi: 10.1126/science.6992275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren KR, Calhoun FJ, May PA, Viljoen DL, Li TK, Tanaka H, Marinicheva GS, Robinson LK, Mundle G. Fetal alcohol syndrome: an international perspective. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:202S–206S. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200105051-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn SE, Tress U, Lunde ER, Chen WA, Cudd TA. The role of cortisol in chronic binge alcohol-induced cerebellar injury: Ovine model. Alcohol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West JR, Parnell SE, Chen WJ, Cudd TA. Alcohol-mediated Purkinje cell loss in the absence of hypoxemia during the third trimester in an ovine model system. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1051–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehtabchi S, Sinert R, Baron BJ, Paladino L, Yadav K. Does ethanol explain the acidosis commonly seen in ethanol-intoxicated patients? Clin Toxicol. 2005;43:161–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]