Abstract

Purpose

To improve smoking prevention efforts, better methods for identifying at-risk youth are needed. The widely used measure of susceptibility to smoking identifies at-risk adolescents; however, it correctly identifies only about one third of future smokers. Adding curiosity about smoking to this susceptibility index may allow us to identify a greater proportion of future smokers while they are still pre-teens.

Methods

We use longitudinal data from a recent national study on parenting to prevent problem behaviors. Only oldest children between 10-13 years of age were eligible. Participants were identified by RDD survey and followed for 6 years. All baseline never smokers with at least one follow-up assessment were included (n=878). The association of curiosity about smoking with future smoking behavior was assessed. Then, curiosity was added to form an enhanced susceptibility index and sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value were calculated.

Results

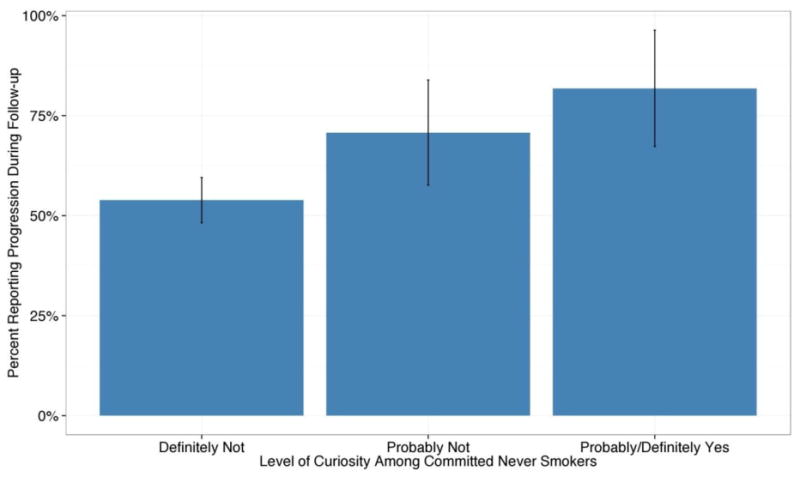

Among committed never smokers at baseline, those who were ‘definitely not curious’ were less likely to progress towards smoking than both those who were ‘probably not curious’ (ORadj =1.89; 95% CI=1.03-3.47) or ‘probably/definitely curious’ (ORadj=2.88; 95% CI=1.11-7.45). Incorporating curiosity into the susceptibility index increased the proportion identified as at-risk to smoke from 25.1% to 46.9%., The sensitivity (true positives) for this enhanced susceptibility index for both experimentation and established smoking increased from 37-40% to over 50%., although the positive predictive value did not improve.

Conclusion

The addition of curiosity significantly improves the identification and classification of which adolescents will experiment with smoking or become established smokers.

Keywords: curiosity, susceptibility to smoking, smoking experimentation, adolescent smoking

1. Introduction

Despite considerable public health action to prevent smoking initiation over the past 50 years (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012), in 2013, 38% of high school seniors had previously smoked and 16.3% were current smokers (Johnston, O'Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2014). A recent Surgeon General's report (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012) called for a renewed focus on increasing efforts to prevent smoking initiation. The success of this approach will depend on both improved identification of at risk adolescents before they have experimented and developing effective prevention interventions (Biglan, Brennan, Foster, & Holder, 2004).

The susceptibility to smoking index (Pierce, Choi, Gilpin, Farkas, & Merritt, 1996) is a widely used measure of risk among never smokers that assesses both intention to smoke and self-efficacy about refusing a cigarette. While this index consistently identifies teens with double the risk of starting to smoke (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012), the proportion of true positives (sensitivity) over the subsequent four years is a low one third of future smokers (Choi, Gilpin, Farkas, & Pierce, 2001; Gritz et al., 2003). This at-risk measure index would be more useful for the development of effective population interventions if it identified more than half of future smokers.

Tobacco marketing is widely recognized as an influence on future initiation (National Cancer Institute, June 2008; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012) and a number of marketing theories specify curiosity as a critical mediating variable through which marketing can affect consumer behavior (Ray, 1982; Smith & Swinyard, 1988; Wells, Burnett, & Moriarty, 2000). Curiosity would appear to be a good candidate variable to improve the susceptibility to smoking index.

Previously, in a three year follow-back to a sample of 12-15 year old teens in California, (Pierce, Distefan, Kaplan, & Gilpin, 2005) we demonstrated that curiosity was independently predicted initiation among baseline never smokers with the additive effect coming mainly from predicting which committed never smokers would experiment in the time period. In both this original study and a more recent international study (Guo, Unger, Palmer, Chou, & Johnson, 2013), curiosity about smoking was associated with receptivity to tobacco industry marketing messages, suggesting that it could be a mediator variable through which marketing influences initiation.

Categorizing smoking risk in the pre-teen years before many major influences on smoking will have occurred will necessarily result in a lower rate of true positives. For example, adolescents are more likely to become smokers if they have friends who smoke (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012), this is especially true with increasing age (Gilpin, Choi, Berry, & Pierce, 1999). Academic achievement is also negatively associated with smoking initiation throughout adolescence (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012), and this effect is enhanced by friend smoking. Part of this increased risk may come from more free time to socialize with friends who smoke, especially when a single parent has limited time to implement recommended parenting practices (Hoeve et al., 2009). These and other influences on smoking result in higher rates among those with lower socio-economic status and among non-Hispanic whites compared to other race-ethnic groups (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012).

In this study we examine whether curiosity can increase the predictive validity of the susceptibility to smoking index. We use data from a US national randomized study of parenting to prevent problem behaviors where participants entered their teen years well after the restrictions on tobacco marketing that followed the Master Settlement Agreement (Pierce & Gilpin, 2004). We hypothesize that the addition of curiosity will differentially increase the proportion of the identified teen population who will initiate smoking.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Study participants and survey methods

In 2003, a random digit dialed (RDD) telephone methodology was used to identify US families with an oldest child between 10 and 13 years old. Parents were invited by mail and telephone interview to join a study on parenting to prevent problem behaviors through adolescence, the protocol for which has been published (Pierce et al., 2008). Both adolescents and parents were enrolled and interviewed by phone (n=1036 pairs). Our analysis used the six adolescent interviews that occurred at approximately 8-12 month intervals after completion of the study baseline assessment. We used only adolescents that reported they had never tried cigarettes – even a puff – and had at least one follow-up assessment (n=878).

2.2 Survey measures

Sociodemographics

At baseline, adolescents self-reported their age, gender, race/ethnicity, and whether or not they lived in a single parent household. The initial telephone number was used to categorize participants by region of the country (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West).

Tobacco use

To determine if the adolescent had initiated tobacco use they were asked, “Have you ever smoked a cigarette?” and, if not, “Have you ever tried or experimented with cigarette smoking, even a few puffs?” A ‘no’ response to both questions classified the adolescent as a never smoker. Established smokers were those who responded positively to the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your life?”

Social Smoking Environment

At baseline, adolescents were asked: “Have any people that you live with now smoked cigarettes in the last year?” with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response; and “How many of your best friends smoke?” with responses ‘none’, ‘some’, ‘most’ or ‘all’ and re-coded dichotomously as either ‘none’ or ‘some/most/all’.

Perceived School Performance

At baseline, adolescents ranked their performance in school as ‘much better than average,’ ‘better than average,’ ‘average,’ or ‘below average’. As the lowest category had few responses, we combined it with the ‘average’ response category.

Receptivity to Tobacco Advertising

At baseline, receptivity to tobacco advertising was measured with two sets of questions: “Think back to the cigarette advertisements you have recently seen. What is the name of the cigarette brand of your favorite cigarette advertisement?” Respondents who did not name a brand were also asked, “Of all the cigarette advertisements you have seen, which do you think attracts your attention the most?” and “If you were given a tee-shirt or a bag that had a tobacco industry cigarette brand image on it, would you use it?”; Those who responded ‘Probably Yes’ or ‘Definitely Yes’ that they would use an item with a tobacco logo were classified as ‘Highly Receptive’. Those who named a favorite cigarette brand only were classified as ‘Moderately Receptive’. Everyone else was classified as ‘Low Receptivity.’

Susceptibility to Smoking

At baseline, susceptibility to smoking was assessed with three items: “Do you think that in the future you might experiment with cigarettes?”; “At any time during the next year do you think you will smoke a cigarette?” and “If one of your best friends were to offer you a cigarette, would you smoke it?” Response options included ‘Definitely Not’, ‘Probably Not’, ‘Probably Yes’, and ‘Definitely Yes’. Adolescents reporting ‘Definitely Not’ to all three questions were classified as ‘committed never smokers.’ Adolescents who responded ‘Probably Not’ to all three questions were classified as having level 1 susceptibility. Those reporting ‘Probably Yes’ or ‘Definitely Yes’ to any question were classified with Level 2 susceptibility.

Curiosity

As in previous studies, curiosity about smoking was assessed using the single item: “Have you ever been curious about smoking a cigarette?” Response options included: ‘Definitely Not’, ‘Probably Not’, ‘Probably Yes’, and ‘Definitely Yes.’ Our results showed low response rates to the highest category, so we collapsed ‘Probably Yes’ and ‘Definitely Yes’ prior to analysis.

2.3 Analysis plan

We used logistic regression models to replicate previous research that curiosity, measured at baseline, predicted which committed never smokers progressed to any higher level of susceptibility or experimentation at any follow-up assessment (coded ‘yes’/‘no’). Of the 658 committed never smokers at baseline, 494 completed all 6 assessments, 172 completed five, 107 completed 4, 52 completed 3, and 53 completed only 2 assessments. All models were adjusted for study design characteristics (i.e. region of US, and single parent households, treatment allocation,), sociodemographic variables, social smoking environment, school performance, and level of receptivity to advertising. We included planned covariates associated with missing outcomes and used logistic regression models that provide adequate representation of relationships with smoking experimentation over repeated assessments. By using the incremental validity perspective, we examine what curiosity can add to the existing measures of the susceptibility index and report a diagnostic classification analysis for both the original susceptibility index and for the enhanced index. We report a) sensitivity, defined as the percent of adolescent experimenters identified as “At Risk” at age 10-13, who achieved the designated smoking level (e.g. experimentation, established) during the study, b) specificity, defined as the percent of adolescents identified as “committed never smokers” who remained never smokers during the study, and c) positive predictive value which is the percentage of the ‘At Risk’ category at baseline who went on to experiment, or became established smokers, by follow-up.

3. Results

3.1 Population Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the 878 never smokers are presented by curiosity status in Table 1. Overall, 75% were committed never smokers, 20% were classified with level 1 susceptibility and 5% with level 2 susceptibility. Two thirds self-identified as non-Hispanic White, with one quarter living in a single parent home. One third lived with a smoker in the house. As expected from their young age, only 10% had a friend who smoked. Slightly less than two thirds (61%) reported that their school performance was better, or much better, than average. Some 37% were receptive to tobacco industry advertising. Of the committed never smokers, 15.2% reported being curious about smoking. Overall, 37% of never smokers aged 10-13 at baseline reported having experimented during the 6-year follow-up period and 12.4% reported becoming established smokers.

Table 1. Baseline sociodemographic, receptivity, and susceptibility characteristics by curiosity for never smoking adolescents who returned for follow-up (n=878).

| Not Curious n | (%) | Curious n | (%) | Total n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| 10-11 | 242 | (36%) | 36 | (18%) | 278 | (32%) |

| 12 | 282 | (42%) | 96 | (47%) | 380 | (43%) |

| 13 | 147 | (22%) | 73 | (36%) | 220 | (25%) |

| Female | 342 | (51%) | 95 | (46%) | 438 | (50%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 434 | (65%) | 123 | (60%) | 559 | (64%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 103 | (15%) | 25 | (12%) | 128 | (15%) |

| Race - Other | 125 | (19%) | 57 | (28%) | 182 | (21%) |

| Missing | 9 | 0 | 9 | |||

| Single Parent | 159 | (24%) | 43 | (21%) | 202 | (23%) |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 113 | (17%) | 25 | (12%) | 138 | (16%) |

| Midwest | 167 | (25%) | 49 | (24%) | 216 | (25%) |

| South | 263 | (39%) | 85 | (41%) | 349 | (40%) |

| West | 128 | (19%) | 46 | (22%) | 175 | (20%) |

| Lives with smoker | 223 | (33%) | 88 | (43%) | 311 | (35%) |

| Friends Smoke | 45 | (7%) | 39 | (19%) | 84 | (10%) |

| School Performance | ||||||

| Average | 225 | (34%) | 84 | (41%) | 310 | (35%) |

| Better than average | 240 | (36%) | 78 | (38%) | 318 | (36%) |

| Much better than average | 185 | (28%) | 37 | (18%) | 223 | (25%) |

| Missing | 21 | 6 | 27 | |||

| Receptivity to Tobacco Advertising | ||||||

| High | 28 | (4.0%) | 36 | (18%) | 64 | (7%) |

| Moderate | 184 | (27%) | 77 | (38%) | 262 | (30%) |

| Low | 452 | (67%) | 91 | (44%) | 544 | (62%) |

| Missing | 1 | 7 | 8 | |||

| Susceptibility | ||||||

| High | 11 | (2%) | 32 | (16.0%) | 43 | (5%) |

| Moderate | 103 | (15%) | 73 | (36.0%) | 177 | (20%) |

| Committed Never | 557 | (83%) | 100 | (49.0%) | 658 | (75%) |

Note: The total column reflects a sample of 878 and the curious/not curious columns reflect a sample of 876 which excludes 2 cases with a missing response to the curiosity question.

3.2 Progression to Smoking

Thirty (30) percent of adolescents who reported that they were definitely not curious at baseline later reported experimenting with cigarettes. Rates of experimentation were 56% and 66% among adolescents who reported they were ‘probably not’ or ‘probably/definitely (yes)’ curious about smoking, respectively A multivariable logistic regression model on 830 adolescents with data on both covariates and outcome was used to evaluate significant predictors for smoking experimentation during the 6-wave follow-up period. Consistent with previous studies, we observed lower rates of experimentation among Non-Hispanic Black adolescents when compared to White adolescents (ORadj=0.56; 95% CI=0.34-0.90). Adolescents with better than average (ORadj=0.52; 95% CI=0.36-0.74) and much better than average (ORadj=0.56; 95% CI=0.38-0.84) school performance were significantly less likely to experiment with tobacco than students with average/below average school performance. Compared to adolescents who said they had no friends that smoked, those with some friends that smoked were significantly more likely to experiment (ORadj=3.25; 95% CI=1.82-5.77). Adolescents at higher risk for experimentation included those who were moderately receptive (ORadj=1.56; 95% CI=1.10-2.20) and highly receptive (ORadj=2.59; 95% CI=1.35-4.97) to tobacco advertising. Experimentation was unrelated to living with a current tobacco smoker (p > 0.30).

The results for the susceptibility index and the curiosity variable, adjusted for the above covariates, are presented in Table 2. Adolescents who were categorized with level 1 susceptibility at baseline were 63% more likely to experiment than committed never smokers (ORadj =1.63; 95% CI=1.10-2.40). The small proportion of adolescents with level 2 susceptibility appeared to be more than twice as likely to experiment as committed never smokers; however, it only reached borderline significance (ORadj =2.24; 95% CI=0.93-5.42). These results suggest that susceptibility should be a dichotomous index.

Table 2. Predictors of experimentation with smoking during the 6-wave follow-up period among adolescents identified as never smokers at baseline (n=830).

| Effect | S.E. | AOR1 | L95CI | U95CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | ||||||

| Susceptibility | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Committed Never Smoker | 1.00 | -- | -- | |||

| Susceptible | 0.49 | 0.20 | 1.63 | 1.10 | 2.40 | 0.014 |

| Highly Susceptible | 0.81 | 0.45 | 2.24 | 0.93 | 5.42 | 0.073 |

|

| ||||||

| Curiosity | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Definitely Not | 1.00 | -- | -- | |||

| Probably Not | 0.71 | 0.23 | 2.04 | 1.29 | 3.21 | 0.002 |

| Probably Yes/Definitely Yes | 0.89 | 0.29 | 2.43 | 1.37 | 4.32 | 0.002 |

Adjusted for study group, age, gender, race/ethnicity, region, single parent household, school performance, lives with a smoker, friends who smoke, receptivity to tobacco advertising.

The curiosity variable was also an independent predictor of experimentation. Compared to those who were definitely not curious at baseline, those who were probably not curious were significantly more likely to experiment (ORadj=2.04; 95% CI=1.29-3.21), as were those who said they were probably/definitely curious (ORadj=2.43; 95% CI=1.37-4.32). The similarity in these adjusted OR's suggested that curiosity also should be collapsed into a dichotomous variable.

3.4 Does adding Curiosity improve the Susceptibility Index?

To create the enhanced index, we categorized committed never smokers as those who answered ”definitely not” to all susceptibility questions as well as to the curiosity question. All other responses were classified as susceptible. The performance of both the original susceptibility index and the new index is presented in Table 4. The original index classified 25.1% of baseline never smokers as ‘at risk’ compared to 36.4% for the enhanced index. For predicting experimentation, the sensitivity (true positive rate) of the original index was 37.2% and this was increased markedly to 51.5% for the enhanced index. Specificity (true negative rate) of the original index was 82.2% which decreased to 72.4% for the enhanced index. Thus, the proportion of those categorized as at risk who progressed to experiment within the study period (positive predictive value) decreased slightly from 55.5% to 52.8%. When the outcome was progression to established smoking, the sensitivity for the original index was 40.2% which increased markedly to 54.6% with the enhanced index. The specificity decreased from 76.8% to 65.7% while the positive predictive value remained stable with values of 17.7% and 16.6%.

Table 4. Classification accuracy when identifying US adolescents who go on to experiment with smoking and those who become established smokers. Included are the susceptibility, curiosity, and an Enhanced Susceptibility Index which combined the two.

| Baseline | Sensitivity1 | Specificity2 | PPV3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment with smoking (328/878) | |||

| Original Susceptibility Index | 37.2% | 82.2% | 55.5% |

| Enhanced Susceptibility Index | 51.5% | 72.4% | 52.8% |

| Established Smoking (97/878) | |||

| Original Susceptibility Index | 40.2% | 76.8% | 17.7% |

| Enhanced Susceptibility Index | 54.6% | 65.7% | 16.6% |

Sensitivity: Percent of young adult experimenters identified as “At Risk” at age 10-13.

Specificity: Percent of young adult never smokers identified as “committed never smokers” at age 10-13 years.

Positive Predictive Value: Percent identified as ‘At Risk’ who experimented

4. Discussion

This paper set out to improve the identification of future smokers while they were still pre-teenagers. In this national sample, compared to the current susceptibility index, the enhanced index identified many more 10-13 year old never smokers as at risk to smoke, from a quarter of the population to almost half. Importantly, the sensitivity of the index – the proportion of true positives in the following 6 years – increased markedly from 37-40% to over 50%. This was observed whether the outcome was experimentation with cigarettes or smoking as much as 100 cigarettes (established smoking). Given that a major purpose of categorizing young teens as ‘at risk’ is to develop interventions targeted towards them that aim to prevent experimentation and progression to addiction, the sensitivity of the index (true positive rate) is the most important characteristic of the susceptibility index. While still lower than desirable, this enhanced index identifies over half of pre-teens who will progress during their teen years. As the interventions are educational or policy based, there will be little harm in exposing adolescents who will not become smokers to these interventions. Thus, the small decline in specificity (true negative rate) with the enhanced index is less important than the considerable improvement in sensitivity. Thus, a large improvement in correctly identifying at risk youth was accomplished without substantially increasing the false positive rate, or degrading the positive predictive value of the index.

Previously, we identified numerous reasons why such an improvement in the index might be expected by the addition of this variable (Pierce et al., 2005). Curiosity is widely recognized as a motivational force that moves people to experiment with many new behaviors (Opdal, 2001). Building curiosity is a focus for many educational endeavors (Day, 1982; Simon, 2001), as well as the target for marketers promoting experimentation with their particular consumer behavior (Smith & Swinyard, 1988). As such, multiple studies have reported that the majority of smokers, when asked to reflect on why they started to smoke, cite curiosity about smoking (Cronan, Conway, & Kaszas, 1991; Guo et al., 2013). In this study, as in previous studies, pre-teens who were receptive to tobacco industry marketing messages that are known to encourage smoking, were also likely to develop curiosity cognitions.

Despite major limitations on tobacco marketing to youth included in the Master Settlement Agreement (Gilpin, Distefan, & Pierce, 2004), this paper notes that a high proportion of pre-teens already had a favorite cigarette advertisement. As previously noted, (Pierce et al., 2010) this proportion will increase with additional exposure to tobacco marketing throughout adolescence. The introduction of alternate cigarette products such as snus, hookah and most recently e-cigarettes, along with their own marketing campaigns, could also have a carry-over effect and increase susceptibility to cigarette smoking. (Agaku, Ayo-Yusuf, Vardavas, Alpert, & Connolly, 2013; Choi, Fabian, Mottey, Corbett, & Forster, 2012; Cobb, Ward, Maziak, Shihadeh, & Eissenberg, 2010; Hill, Larcombe, & Refshauge; Pepper et al., 2013).

Further, as teens progress through adolescence, they are known to change friendship groups frequently (Steinberg, 2002). When changing friends increases exposure to smoking, then teens will be more likely to be susceptible to smoking. More research is necessary to identify the effect of changing influences throughout adolescence and the large national Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) cohort study (National Institutes of Health & Food and Drug Administration, 2014) has questions that should advance the science in these areas.

Using a susceptibility index to identify adolescents at high risk to start smoking is only important if it leads to actions that can reduce that risk level. Some approaches that have been suggested include the use of school curricula focused on decoding media messages (Bier, Zwarun, & Fehrmann Warren, 2011) as well as educating parents on how to monitor their child's potential curiosity about smoking so that early preventive action may be taken (Pierce et al., 2005). Increased excise taxes (Chaloupka & Wechsler, 1995) and smoke-free schools and colleges (Pierce et al., 1991) are populations level interventions that have been associated with reductions in smoking behavior national (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2009).

In addition to curiosity and susceptibility, other variables were found to be associated with progression toward smoking. These included average/below average school performance, exposure to friends who smoked, and living in a single parent household. Poor school performance in the middle school years is a well-known powerful predictor of future smoking (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). Students with poor middle school academic preparation have great difficulty recovering to become quality performers in high school (Simons-Morton et al., 1999). It is more likely that they put much less time into their studies throughout their high school years and spend that time with friendship groups comprised of other low performers, many of whom may have already experimented with smoking (Mounts & Steinberg, 1995; Steinberg, Delnevo, Foulds, & Pevzner, 2004). As expected (Mrug, Gaines, Su, & Windle, 2010), the few adolescents who were exposed to peer smokers were also much more likely to experiment with smoking over the duration of the study. Adolescents who came from single parent households had a greater probability of future smoking. There are a number of reasons why this might be the case. Single parents are more likely to be smokers, more likely to have low income (Jun & Acevedo-Garcia, 2007), and more likely to have limited time with their children. Yet, even when parents follow recommended practices (Hoeve et al., 2009), tobacco marketing messages and promotions targeted to youth appear to be able to undermine the effectiveness of these practices (Pierce, Distefan, Jackson, White, & Gilpin, 2002).

Our findings are based on a representative US sample, which is a major strength; however, the study recruited parents who were interested in the issue of parenting practices to prevent adolescent problem behaviors. Thus, the low rate of smoking experimentation over the six years of the study suggests that those who volunteered had children who were less likely to have influences encouraging them to smoke. This enables us to investigate in considerable detail early movement in the process of becoming a smoker. In this study, we focused on classifying risk during the pre-adolescent years. Future work will use the multiple surveys in this study to explore the contextual dynamics of influences on smoking behavior throughout adolescence. Although the study retained 74% of the sample through wave 5 (~5 years), there was a considerable attrition between waves 5 and 6 (57% response rate) as many adolescents turned 18 and left home, many for college and were harder to reach. Particularly in the early years, attrition was more likely to occur in families with teens who were at higher risk to start smoking. While we included covariates associated with risk for smoking, in all evaluative models, our attrition level is a limitation of the study.

5. Conclusions

The currently accepted susceptibility index is limited to assessing intentions and self-efficacy expectations about smoking and while it identifies many future smokers during the early adolescent years, it also misclassifies others as being at low risk. The addition of curiosity significantly improves the identification and classification of which adolescents will experiment with smoking. We propose that such a measure should be included in adolescent tobacco surveillance systems and the results should trigger interventions designed to reduce this early warning of future smoking behavior. The recently launched longitudinal Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, which will include participants as young as 12 years old, will help to further explore curiosity and the utility of an enhanced susceptibility index.

Figure 1. Curiosity About Smoking. Curiosity among adolescent Committed Never Smokers at baseline and progression toward smoking 5 years later.

Table 3. Predictors of progression in level of susceptibility or smoking experimentation at follow-up among committed never smokers at baseline (n=614).

| Effects | Effect | S.E. | AOR1 | L95CI | U95CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Parent household | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| No | 1.00 | -- | -- | |||

| Yes | 0.48 | 0.22 | 1.62 | 1.05 | 2.48 | 0.03 |

|

| ||||||

| School Performance | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Average/Below | 1.00 | -- | -- | |||

| Better Than Average | -0.60 | 0.21 | 0.55 | 0.37 | 0.83 | <0.01 |

| Much Better Than Average | -0.77 | 0.22 | 0.46 | 0.30 | 0.71 | <0.01 |

|

| ||||||

| Friends who Smoke | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| None/Some/Most/All | 1.00 | -- | -- | |||

| Some | 1.11 | 0.40 | 3.05 | 1.38 | 6.72 | 0.01 |

|

| ||||||

| Receptivity to Tobacco Advertising | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Low | 1.00 | -- | -- | |||

| Moderate | 0.31 | 0.20 | 1.37 | 0.93 | 2.02 | 0.12 |

| High | 0.68 | 0.46 | 1.97 | 0.81 | 4.82 | 0.14 |

|

| ||||||

| Curiosity | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Definitely Not | 1.00 | -- | -- | |||

| Probably Not | 0.64 | 0.31 | 1.89 | 1.03 | 3.47 | 0.04 |

| Probably Yes/Definitely Yes | 1.06 | 0.49 | 2.88 | 1.11 | 7.45 | 0.03 |

Adjusted for study group, age, gender, race/ethnicity, region, lives with a smoker.

Highlights.

Identifying who is at risk to smoke is critical to programs to prevent smoking.

Current susceptibility index identifies 30% of future experimenters.

Adding curiosity improves the sensitivity of the susceptibility index to over 50%.

Preventing pre-teens from becoming curious about smoking is an important goal.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources: Funding for the primary data collection was provided by National Cancer Institute grant CA093982, an American Legacy Foundation grant, and Tobacco Related Disease Research Program grants 17RT-0088 and 15RT-0238 from the University of California. Funding for this analysis and manuscript preparation has been funded with Federal funds from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, and the Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN271201100027C, and Tobacco Related Disease Research Program grant 21RT-01335.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this presentation are those of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views, official policy or position of the US Department of Health and Human Services or any of its affiliated institutions or agencies.

Contributors: Jesse Nodora, DrPH concept design, manuscript writing and review

Sheri J. Hartman, PhD manuscript development and review

David R. Strong, PhD, MPH, concept design, data analysis, manuscript writing and review

Karen Messer, PhD, concept design, data analysis

Lisa James, data collection, manuscript review

Martha M. White, MS, data preparation and analysis, manuscript review

David B. Portnoy, PhD, MPH, manuscript development and review

Conrad J. Choiniere, PhD, manuscript development and review

Genevieve C. Vullo, manuscript development and review

John P. Pierce, PhD project funding, data collection, concept design, manuscript development and review

Conflict of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agaku IT, Ayo-Yusuf OA, Vardavas CI, Alpert HR, Connolly GN. Use of conventional and novel smokeless tobacco products among US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):e578–586. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bier MC, Zwarun L, Fehrmann Warren V. Getting universal primary tobacco use prevention into priority area schools: a media literacy approach. Health Promot Pract. 2011;12(6) Suppl 2:152S–158S. doi: 10.1177/1524839911414887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Brennan P, Foster S, Holder H. Helping Adolescents at Risk: Prevention of Multiple Problem Behaviors. New York: The Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chaloupka F, Wechsler H. Price, tobacco control policies and smoking among young adults. NBER Working Paper Series(5012) 1995 doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(96)00530-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Fabian L, Mottey N, Corbett A, Forster J. Young adults' favorable perceptions of snus, dissolvable tobacco products, and electronic cigarettes: findings from a focus group study. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(11):2088–2093. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Pierce JP. Determining the probability of future smoking among adolescents. Addiction. 2001;96(2):313–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96231315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb C, Ward KD, Maziak W, Shihadeh AL, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: an emerging health crisis in the United States. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34(3):275–285. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.34.3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan TA, Conway TL, Kaszas SL. Starting to smoke in the Navy: when, where and why. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33(12):1349–1353. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90278-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day HI. Curiosity and the interested explorer. Performance & Instruction. 1982;21(4):19–22. doi: 10.1002/pfi.4170210410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin EA, Choi WS, Berry C, Pierce JP. How many adolescents start smoking each day in the United States? J Adolesc Health. 1999;25(4):248–255. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin EA, Distefan JM, Pierce JP. Population receptivity to tobacco advertising/promotions and exposure to anti-tobacco media: effect of Master Settlement Agreement in California: 1992-2002. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5(3 Suppl):91S–98S. doi: 10.1177/1524839904264601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritz ER, Prokhorov AV, Hudmon KS, Mullin Jones M, Rosenblum C, Chang CC, de Moor C. Predictors of susceptibility to smoking and ever smoking: a longitudinal study in a triethnic sample of adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(4):493–506. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000118568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Unger JB, Palmer PH, Chou CP, Johnson CA. The role of cognitive attributions for smoking in subsequent smoking progression and regression among adolescents in China. Addict Behav. 2013;38(1):1493–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill D, Larcombe I, Refshauge JG. Smoking and impairment of performance. Med J Aust. 1978;2(2):60–63. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1978.tb131346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve M, Dubas JS, Eichelsheim VI, van der Laan PH, Smeenk W, Gerris JR. The relationship between parenting and delinquency: a meta-analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2009;37(6):749–775. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Evaluating the effectiveness of smoke-free policies. Vol. 13. Lyon: IARC Handbook of Cancer Prevention, Tobacco Control; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use: 1975-2013: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2014. p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Jun HJ, Acevedo-Garcia D. The effect of single motherhood on smoking by socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(4):653–666. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounts NS, Steinberg L. An ecological analysis of peer influences on adolescent grade point average and drug use. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:7. [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, Gaines J, Su W, Windle M. School-level substance use: effects on early adolescents' alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71(4):488–495. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use. Tobacco Control Monograph No. 19. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: Jun, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health, & Food and Drug Administration; Feb 3, 2014. PATH Population of Tobacco and Health. 2014. Retrieved from http://www.pathstudyinfo.nih.gov/UI/HomeMobile.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Opdal P. Curiosity, Wonder and Education seen as Perspective Development. Studies in Philosophy and Education. 2001;20:13. [Google Scholar]

- Pepper JK, Reiter PL, McRee AL, Cameron LD, Gilkey MB, Brewer NT. Adolescent males' awareness of and willingness to try electronic cigarettes. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(2):144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Merritt RK. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol. 1996;15:355–361. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Distefan JM, Jackson C, White MM, Gilpin EA. Does tobacco marketing undermine the influence of recommended parenting in discouraging adolescents from smoking? Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(2):73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Distefan JM, Kaplan RM, Gilpin EA. The role of curiosity in smoking initiation. Addict Behav. 2005;30(4):685–696. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Gilpin EA. How did the Master Settlement Agreement change tobacco industry expenditures for cigarette advertising and promotions? Health Promot Pract. 2004;5(3 Suppl):84S–90S. doi: 10.1177/1524839904264600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, James LE, Messer K, Myers MG, Williams RE, Trinidad DR. Telephone counseling to implement best parenting practices to prevent adolescent problem behaviors. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29(3):324–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.09.006. doi:S1551-7144(07)00151-6 [pii] 10.1016/j.cct.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Messer K, James LE, White MM, Kealey S, Vallone DM, Healton CG. Camel 9 cigarette-marketing campaign targeted young teenage girls. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):619–626. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0607. doi:peds.2009-0607 [pii] 10.1542/peds.2009-0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Naquin M, Gilpin E, Giovino G, Mills S, Marcus S. Smoking initiation in the United States: a role for worksite and college smoking bans. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83(14):1009–1013. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.14.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray ML. Advertising and communication management. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Simon HA. “Seek and ye shall find”: How curiosity engenders discovery. In: Crowley Kevin D, Schunn Christian D, Okada Takeshi., editors. Designing for science: Implications from everyday classroom and professional settings. Mahwah, NJ Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates; 2001. pp. 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, Crump AD, Haynie DL, Saylor KE, Eitel P, Yu K. Psychosocial, school, and parent factors associated with recent smoking among early-adolescent boys and girls. Preventive Medicine. 1999;28(2):138–148. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RE, Swinyard WR. Cognitive responses to advertising and trial: Belief strength, belief confidence and product curiosity. Journal of Advertising. 1988;17(3):3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Adolescence. 6th. McGraww-Hill; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg MB, Delnevo CD, Foulds J, Pevzner E. Characteristics of smoking and cessation behaviors among high school students in New Jersey. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(3):231–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Georgia: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wells W, Burnett J, Moriarty S. Advertising: principles & practice. 5, illustrated. Prentice Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]