Abstract

G protein coupled receptor 55 (GPR55) is expressed throughout the body, and although its exact physiological function is unknown, studies have suggested a role in the cardiovascular system. In particular, GPR55 has been proposed as mediating the haemodynamic effects of a number of atypical cannabinoid ligands; however this data is conflicting. Thus, given the incongruous nature of our understanding of the GPR55 receptor and the relative paucity of literature regarding its role in cardiovascular physiology, this study was carried out to examine the influence of GPR55 on cardiac function. Cardiac function was assessed via pressure volume loop analysis, and cardiac morphology/composition assessed via histological staining, in both wild-type (WT) and GPR55 knockout (GPR55−/−) mice. Pressure volume loop analysis revealed that basal cardiac function was similar in young WT and GPR55−/− mice. In contrast, mature GPR55−/− mice were characterised by both significant ventricular remodelling (reduced left ventricular wall thickness and increased collagen deposition) and systolic dysfunction when compared to age-matched WT mice. In particular, the load-dependent parameter, ejection fraction, and the load-independent indices, end-systolic pressure-volume relationship (ESPVR) and E max, were all significantly (P<0.05) attenuated in mature GPR55−/− mice. Furthermore, GPR55−/− mice at all ages were characterised by a reduced contractile reserve. Our findings demonstrate that mice deficient in GPR55 exhibit maladaptive adrenergic signalling, as evidenced by the reduced contractile reserve. Furthermore, with age these mice are characterised by both significant adverse ventricular remodelling and systolic dysfunction. Taken together, this may suggest a role for GPR55 in the control of adrenergic signalling in the heart and potentially a role for this receptor in the pathogenesis of heart failure.

Introduction

G protein coupled receptor 55 (GPR55) belongs to a group of rhodopsin-like seven transmembrane/g-protein coupled receptors and was originally isolated in human striatum [1]. GPR55 has since been shown to be widely distributed in a variety of cell types and in the central nervous, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular systems, in both humans [2] and rodents [3]. The downstream signalling mechanisms following activation of GPR55 remain unclear although activation of Gαq/11 or Gα13 culminating in an eventual elevation of intracellular calcium (Ca2+) and phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and/or nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) has been implicated [4], [5], [6]. Furthermore, while the exact physiological/pathophysiological function of GPR55 remains to be determined, studies have suggested a role in pain, bone development, carcinogenesis, pregnancy, metabolism (reviewed by [2]), and finally in the control of cardiac haemodynamics.

In terms of the cardiovascular system, a role for GPR55 was proposed on the basis of accumulating evidence from a series of studies investigating the profound haemodynamic (hypotension and bradycardia) effects of cannabinoid ligands, which were initially believed to be mediated primarily through the classic cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2, (reviewed by [7]). However, combined evidence from studies using mice deficient in either CB1 or CB2 and from experiments employing various pharmacological agonist/antagonist combinations, have revealed that many cannabinoid-induced haemodynamic responses are mediated by non-CB1/CB2 receptors [8], [9]. Moreover, cannabinoids that have little or no affinity for the CB1/CB2 receptors have also been shown to exert cardiovascular effects, further suggesting a role for additional receptor(s) in mediating these effects [10], [11]. Based on the findings that some vasoactive cannabinoids (e.g. abnormal cannabidiol and O-1602) are potent agonists of GPR55 [3], [5], [12], [13], the latter has been proposed as a possible third cannabinoid receptor [14], [15]. However, a more recent study investigating an array of cannabinoids as possible ligands for GPR55 demonstrated that only lysophosphatidylinositol (LPI), rimonabant, and AM251 are agonists for this receptor, and that neither abnormal cannabidiol nor O-1602 activate GPR55 [16]. Thus, given the incongruous nature of our understanding of the GPR55 receptor and the relative paucity of literature regarding its role in cardiovascular physiology we conducted a study using the previously described homozygous GPR55-deficient (GPR55−/−) mouse [12], [17], to examine the influence of GPR55 on cardiac physiology/function (assessed via pressure volume loop analysis).

Methods

Breeding and genotyping of GPR55 mice

Heterozygous GPR55 knockout mice were intermated to produce F1 mice homozygous for the GPR55 mutation (GPR55−/−) and wild-type (WT) littermate controls and genotyped as previously described [12]. Both male and female WT and GPR55−/− were bred and housed in the University of Aberdeen Medical Research Facility. Animals were maintained at a temperature of 21±2°C, with a 12 h light/dark cycle and with free access to food and tap water. Animals were obtained on a daily basis and allowed to acclimatize before commencing the study. All studies were performed under an appropriate Project License authorized under the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. All in vivo work is reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines [18].

Measurement of ventricular function

Mice were anaesthetised with a mixture of ketamine (120 mg kg−1; Vetalar, Pfizer, Dublin, Ireland) and xylazine (16 mg kg−1; Rompun, Bayer, Dublin, Ireland) via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection and the trachea cannulated to allow artificial respiration when required. The right jugular vein was cannulated with flame-stretched Portex polythene tubing (0.58 mm ID×0.96 mm OD; Smiths Medical International Ltd., Hyde, Kent, UK) for drug administration and the mice ventilated on room air (130–140 strokes min−1 and tidal volume 150–210 µL calculated based on individual animal weight; Harvard small animal respiration pump; Edenbridge, Kent, UK). Ventricular function was measured in mice via pressure volume analysis using a method adapted from Pacher et al. [19]. Briefly, the chest was opened, the pericardium removed, the apex of the left ventricle punctured with a 27 g needle, and a 1.4-Fr pressure conductance catheter (SPR-839; Millar Instruments, Houston, Texas, US) inserted into the ventricle to record cardiac function via the MPVS-Ultra Single Segment Foundation System (Millar Instruments, US). A steel thermistor probe (Fisher Scientific Ltd., Loughborough, Leicestershire, UK) was inserted into the rectum to measure core temperature, which was maintained at 37–38°C with the aid of a Vetcare heated pad (Harvard Apparatus Ltd.). Anaesthesia was maintained throughout by administration of 50 µl 25 g−1 (b.w.) of the ketamine and xylazine mixture via i.p. injection every 40 min or as required. After a stabilisation period of approximately 20 min baseline cardiac function was recorded and then a bolus dose of dobutamine (10 µg kg−1) administered to mice to examine contractile reserve. To obtain measurements of load-independent contractility (time varying elastance; E max) and the slopes of both the end-systolic pressure-volume relationship (ESPVR) and end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship (EDPVR), venous return (left ventricular preload) was varied via transient occlusion of the inferior vena cava. Finally, to enable correction of pressure volume loops during data analysis the parallel conductance (Vp) was calculated via the administration of a small volume of hypertonic saline (15%; i.v.) to mice. Following completion of the in vivo protocol, animals were euthanised via an overdose of anaesthetic and blood collected to allow volume calibration of the catheter using heparinized blood-filled calibration cuvettes. Finally, the heart was removed and the ventricular tissue fixed in 10% formal buffered saline for histological studies.

In vivo experimental protocols

Young male/female (10 week old) WT (n = 15; 8 males & 7 females) and GPR55−/− (n = 15; 8 males & 7 females) mice were used to investigate the role of GPR55 in the control of basal cardiac function. As preliminary data had demonstrated that 8 month old GPR55−/− mice had elevated blood pressure compared to WT mice (unpublished findings from AstraZeneca) an additional series of experiments was carried out using mature mice (8 months old; WT (n = 14; 7 males & 7 females) and GPR55−/− (n = 14; 7 males & 7 females)) to investigate whether any observed changes in cardiac function were influenced by advancing age. As there were no gender-related differences in either cardiac function or structure the data presented represents the pooled data from both males and females within each group.

Histological assessment of cardiac morphology

For haemotoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, fixed ventricular tissue was embedded in paraffin wax (Thermo Scientific) and 5 µm sections cut. Sections were dehydrated through a series of histosolve (Thermo Scientific) and graded alcohols and incubated in haematoxylin to stain nuclei, and subsequently incubated in 0.5% acid alcohol, Scott's tap water substitute, and finally eosin to stain the remaining cellular material. After staining, sections were mounted with a xylene substitute mountant (Thermo Scientific) and covered with a cover slip. Analysis of the tissue was carried out with the use of a Leica DMLB light microscope (Leica Microsystems, Milton Keynes, Bucks, UK) at a magnification of ×25 for gross morphological measurements and ×400 for cardiomyocyte analysis and nuclei quantification. For gross morphology, multiple measurements of the right ventricular free wall, the interventricular septal wall, and the left ventricular free wall were made using computerised planimetry (ImageJ software, National Institute of Health (NIH), Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD). In addition, left ventricular chamber area was calculated as a percentage of total left ventricle area. For cardiomyocyte measurements, the cross-sectional area of 5–10 cardiomyocytes with a centrally located nucleus and circular shaped cell membrane was measured in the left ventricular free wall of each animal using ImageJ. Finally, to detect any changes in myocardial cellular populations, the number of positively stained nuclei within 10 fields randomly selected from the left ventricle was quantified.

Quantification of cardiac collagen deposition

For Masson Trichrome (MT) staining, paraffin embedded ventricular sections (5 µm) were dehydrated through a series of histosolve (Thermo Scientific) and graded alcohols and incubated in biebrich scarlet-acid fuchsin solution to stain cellular material, and subsequently incubated in a phosphomolybdic–phosphotungstic acid solution, aniline blue, and finally 1% acetic acid to stain the collagen fibers. After staining, sections were mounted with a xylene substitute mountant (Thermo Scientific) and covered with a cover slip. Photomicrographs (×400) were taken with the use of a Leica DMLB light microscope (Leica Microsystems, Milton Keynes, Bucks, UK) and collagen volume fraction (CVF) was calculated by determining the percentage area of blue (collagen) stained tissue within 10 fields randomly selected from the left ventricle using computerised planimetry (ImageJ software, National Institute of Health (NIH), Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD). Briefly, images were converted to RGB stacks, separated into a montage, and the red channel thresholded to detect the stained collagen (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/docs/examples/stained-sections/index.html). For continuity, the same threshold was used on images from all animals and the measurement of collagen restricted to the left ventricle to correspond with the functional pressure volume loop data.

Immunostaining for GPR55

Immunohistochemical staining for GPR55 was performed in fixed heart sections from all groups. Paraffin embedded myocardial tissue sections were cut (4 µm) and mounted onto polysine coated slides. Following dehydration and deparaffinization, antigen retrieval was performed by pressure cooking using Diva (Biocare, USA). Immunohistochemical staining was carried out using the Intellipath Immunostainer (Biocare) and involved the following steps. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked via incubation with Peroxidize 1 (Biocare, USA), followed by Background sniper (Biocare, USA). The primary antibody, GRP55-A162T750 (MBL International Corporation) was diluted 1∶500 using DaVinci Green Diluent (Biocare, USA) and incubated on the slides for 1 hour. Sections were then incubated with a two-step biotin free micro-polymer detection system (MACH3; Biocare, USA), counterstained with Tachas hematoxylin prior to incubation with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Betazoid DAB, Biocare, USA). Sections were then finally dehydrated and cleared through a series of graded alcohols and xylene and mounted in Mountex mounting medium (HistoLAb AB, Sweden). Two negative control methods were used to verify the specificity of the antibody reaction. The first negative control was performed by replacing the MACH3 system with buffer to exclude unspecific binding of the secondary antibody to the tissue. Secondly, a dilution test was performed, where the primary antibody was diluted to a concentration that did not give rise to positive staining. Photomicrographs of sections were taken at a magnification of ×200 with the use of a Sony progressive 3CCD colour video camera.

Solutions and chemicals

All chemicals were purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich (Dorset, UK) or Fisher Scientific UK Ltd. (Loughborough, UK) unless otherwise stated. Scott's tap water substitute contained (in mM): 81 MgSO4.7H2O and 42 NaHCO3.

Statistical analysis

For haemodynamic and morphological data a one-way ANOVA and bonferroni post-hoc test was used to compare selected experimental groups. All data was expressed as the mean±s.e.m and significance was determined as P<0.05.

Results

Effect of gene deletion for GPR55 on baseline cardiac function in young mice

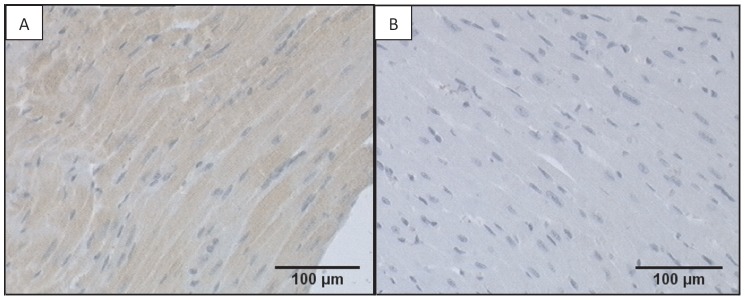

Positive staining for GPR55 was detected in ventricular tissue from WT (Figure 1A) but not GPR55−/− mice (Figure 1B). Furthermore, image analysis revealed diffuse staining for GPR55 throughout the cardiomyocytes, suggestive of a role for this receptor in the control of contractile function. However, pressure volume loop analysis revealed that, with the exception of heart rate (HR), which was significantly elevated in 10 week old GPR55−/− mice, none of the other load-dependent indices of left ventricular (LV) systolic and diastolic function; end systolic pressure (ESP), end systolic volume (ESV), stroke volume (SV), cardiac output (CO), ejection fraction (EF), maximum (dP/dt max) and minimum (dP/dt min) derivatives of pressure, arterial elastance (E a; an index of LV afterload and reflective of peripheral vascular resistance), end diastolic pressure (EDP) and volume (EDV), recorded in this study differed significantly when compared to 10 week old WT mice (Table 1). Furthermore, none of the load-independent measurements of LV function, ESPVR, EDPVR, and E max, differed significantly between both groups of mice (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Expression of GPR55 in ventricular tissue from WT and GPR55−/− mice.

Photomicrographs taken at ×200 demonstrate positive staining for GPR55 in ventricular tissue (localised to the cardiomyocytes) from WT mice (A), but not GPR55−/− mice (B).

Table 1. Load-dependent haemodynamic parameters in control (WT) mice and those with a genetic deletion for GPR55 (GPR55−/−).

| Young Mice (10 week old) | Mature Mice (8 month old) | |||

| WT (n = 15) | GPR55−/− (n = 15) | WT (n = 14) | GPR55−/− (n = 14) | |

| Body weight (g) | 21±0.5 | 23±0.5 | 30.5±0.5 | 30.7±0.7 |

| HR (BPM) | 395±7 | 420±7* | 406±8 | 425±10 |

| ESP (mmHg) | 91.8±2.2 | 93.4±3.5 | 111.8±3.5* | 101.9±3.7 |

| EDP (mmHg) | 4.5±0.4 | 5.1±0.3 | 5.2±0.3 | 5.3±0.3 |

| ESV (µL) | 11.9±0.4 | 13.2±0.8 | 16.2±0.7* | 22.7±0.7# † |

| EDV (µL) | 21.8±0.8 | 23.1±0.6 | 29.3±0.8* | 35.1±0.9# † |

| SV (µL) | 11.2±0.4 | 11.3±0.5 | 15.1±0.8* | 14.2±0.8# |

| SW (mmHg*µL) | 910±76 | 939±66 | 1377±67* | 1278±103 |

| CO (µL/min) | 4430±214 | 4768±265 | 6092±382* | 5994±353 |

| E a (mmHg/µL) | 7.3±0.7 | 8.1±0.6 | 8.1±0.5 | 6.7±0.4 |

| EF (%) | 51.7±1.9 | 50.9±1.7 | 51.5±2 | 40.1±1.6# † |

| dP/dtmax (mmHg/s) | 7800±339 | 7800±486 | 8760±563 | 8399±457 |

| dP/dtmin (mmHg/s) | −7773±452 | −7290±453 | −8448±578 | −8643±714 |

Cardiac function is unaffected by age in WT mice, but undergoes a significant deterioration in GPR55 deficient mice. Data is expressed as mean±s.e.m. (n = 14–15).

*P<0.05 vs. WT (Young);

P<0.05 vs. GPR55−/− (Young);

P<0.05 vs. WT (Mature).

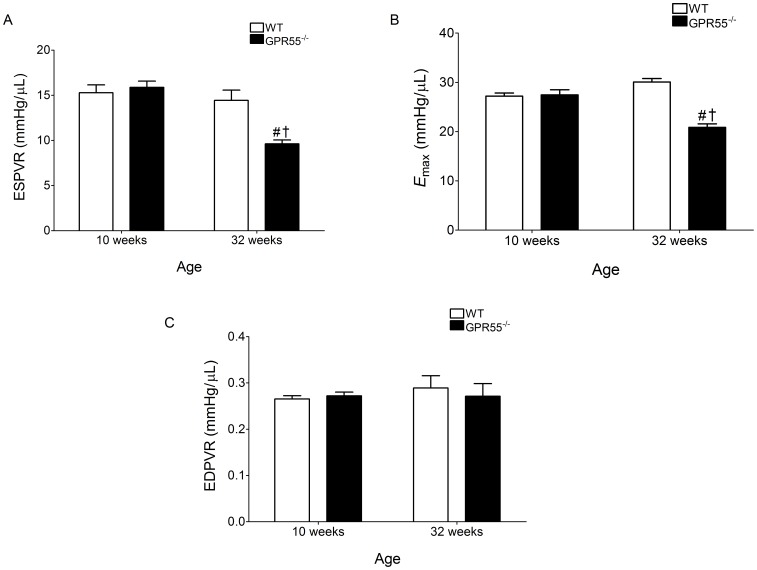

Figure 2. Load-independent (ESPVR, EDPVR, and E max) haemodynamic parameters in both WT and GPR55−/− mice.

In mature mice with a genetic deletion for GPR55 (GPR55−/−), baseline systolic function, but not diastolic function, was adversely affected. In particular, significant reductions in both ESPVR (A) and E max (B) indicate attenuated cardiac contractility, while EDPVR (indicative of relaxation rate) was unaffected (C) in mature GPR55−/− mice. Data is expressed as mean±s.e.m. (n = 14–15) *P<0.05 vs. WT (Young); #P<0.05 vs. GPR55−/− (Young); †P<0.05 vs. WT (Mature).

Age dependent changes of GPR55 gene deletion on baseline cardiac function

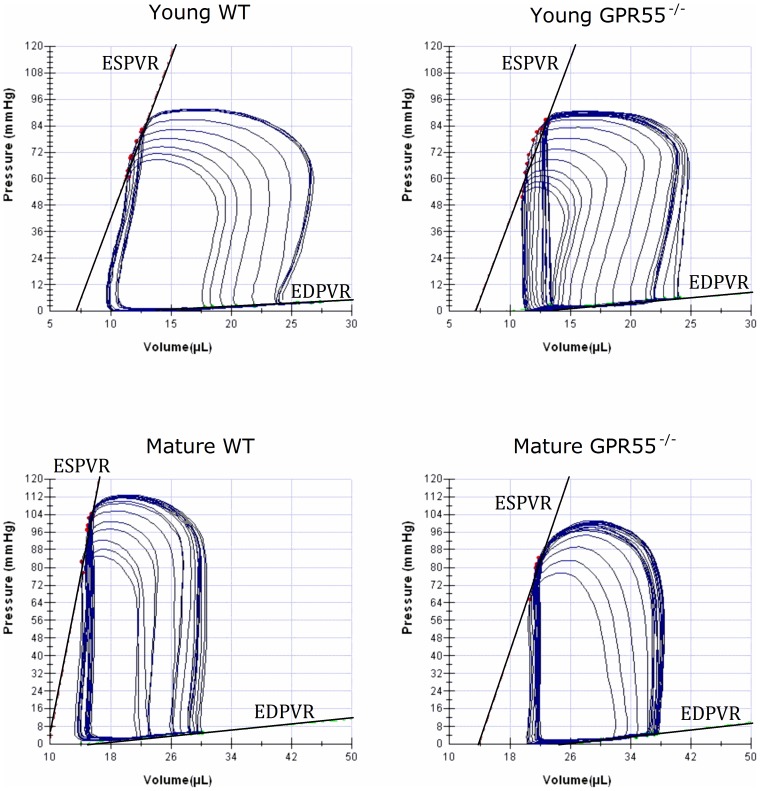

In terms of load-dependent cardiovascular variables, both indices of systolic and diastolic function were significantly altered with age in both WT and GPR55−/− mice (Table 1). In particular, ESP, ESV, EDV, SV, SW, and CO were all significantly elevated in mature WT mice compared with young mice (Table 1), which in part may be due to the increased circulating blood volume in these larger animals. In contrast, only SV, EDV, and ESV were significantly increased in mature GPR55−/− mice, and in terms of the latter two indices they were also significantly elevated in comparison to age-matched WT mice. Furthermore, mature GPR55−/− mice also exhibited compromised systolic function as EF was significantly decreased in these mice when compared to both young GPR55−/− mice and age-matched WT controls (P<0.001; Table 1). This emerging systolic dysfunction appeared to be due to the significant increase in EDV (P<0.001) recorded in the mature GPR55−/− mice, which was not accompanied by a sufficient increase in SV (to maintain EF), when compared to age-matched WT controls (Table 1). Furthermore, load-independent measurements obtained during transient occlusion of the inferior vena cava (to alter preload), demonstrated a significant downward shift in both the ESPVR slope (P<0.001; Figure 2A) and the time varying elastance (E max; P<0.0001; Figure 2B) in the mature GPR55−/− mice indicative of decreased contractility/inotropy. In contrast, the slope of the EDPVR (indicative of an increase in LV chamber stiffness; Figure 2C) did not differ significantly between any of the experimental groups examined and thus load-independent diastolic function did not appear to be altered following deletion of the GPR55 gene. Taken together, the changes in both load-dependent and load-independent indices of cardiac function observed in the mature GPR55−/− mice suggest that the emerging systolic dysfunction appears to be due to the deleterious combination of both GPR55 gene deletion and advancing age in these animals (representative pressure volume loops of this cardiac dysfunction are illustrated in Figure 3).

Figure 3. Representative left ventricular pressure volume loops from all experimental groups are included and illustrate the emerging systolic dysfunction (i.e. downward and rightward shift in the ESPVR curve) associated with mature GPR55−/− mice.

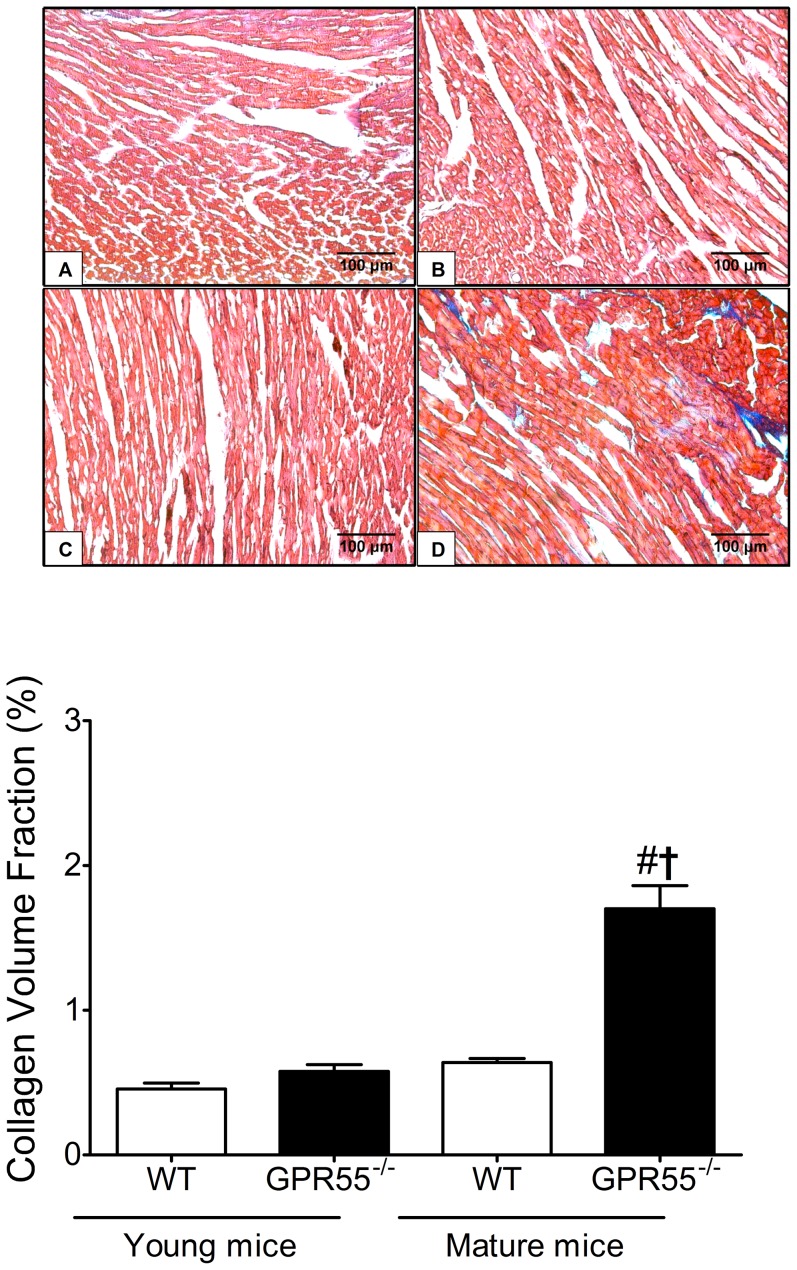

Morphological measurements of cardiac dimensions revealed several significant age-related differences in WT mice. In particular, heart weight∶body weight ratio (HW∶BW; mg/g), cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area (CSA), and left ventricular (LV) wall thickness were all significantly increased in 8 month old WT mice compared to 10 week old WT mice (all P<0.05; Table 2). In contrast, HW∶BW, LV wall thickness, and nuclei number were all significantly decreased in the mature GPR55−/− mice compared to age-matched WT mice (both P<0.05) and CSA was not significantly altered in comparison to young GPR55−/− mice (Table 2). Furthermore, mature GPR55−/− mice were characterised by significant increases in both interstitial and perivascular cardiac collagen deposition when compared to both the younger knockout mice and age-matched WT controls (P<0.05; Figure 4). While the latter may suggest significant ventricular remodelling (at least at the level of cardiac extracellular matrix composition), as this cardiac ‘fibrosis’ was not coupled with a significant upward shift in the EDPVR slope (Figure 2C) it seems unlikely that this ventricular remodelling influenced LV compliance and/or diastolic function in these mice. Finally, right ventricular wall thickness, interventricular septal wall thickness, and LV chamber area were all unchanged between all four groups of WT and GPR55−/− mice (Table 2).

Table 2. Measurement of ventricular dimensions in WT and GPR55−/− mice.

| Young Mice (10 week old) | Mature Mice (8 month old) | |||

| WT (n = 15) | GPR55−/− (n = 15) | WT (n = 14) | GPR55−/− (n = 14) | |

| HW∶BW (mg/g) | 3.07±0.06 | 3.19±0.1 | 3.98±0.06* | 3.59±0.02† |

| LV Wall Thickness (mm) | 1.68±0.04 | 1.79±0.11 | 1.92±0.05* | 1.65±0.07† |

| RV Wall Thickness (mm) | 0.39±0.02 | 0.38±0.04 | 0.36±0.04 | 0.40±0.01 |

| Interventricular Septal Thickness (mm) | 1.25±0.04 | 1.22±0.06 | 1.31±0.01 | 1.35±0.02 |

| Chamber Area (% of LV) | 13.9±0.9 | 15.5±1.3 | 12.8±0.7 | 13.2±0.8 |

| Cardiomyocyte CSA (µm2) | 89±9 | 94±8 | 145±5* | 144±7 |

| Nuclei number (nuclei/mm2) | 6726±284 | 6456±169 | 6471±393 | 4983±405# † |

Ventricular dimensions did not differ significantly between young WT and GPR55−/− mice, however mature GPR55−/− mice were characterised by significant myocardial remodelling; including a reduction in left ventricular (LV) free wall thickness, myocardial nuclei number, and HW∶BW, and increased collagen deposition. Data is expressed as mean±s.e.m. (n = 14–15).

*P<0.05 vs. WT (Young);

P<0.05 vs. GPR55−/− (Young);

P<0.05 vs. WT (Mature).

Figure 4. Influence of GPR55 gene deletion on cardiac collagen deposition.

Representative photomicrographs (×400) demonstrating cardiac collagen deposition in young WT (A), young GPR55−/− (B), mature WT (C), and mature GPR55−/− (D) mice. Collagen deposition was significantly increased in the left ventricle of mature GPR55−/− mice (E). Data is expressed as mean±s.e.m. (n = 14–15) #P<0.05 vs. GPR55−/− (Young); †P<0.05 vs. WT (Mature).

Effect of GPR55 gene deletion on contractile reserve in young and aged mice

Contractile reserve, assessed by the change from baseline cardiac function in response to the α1/β1-adrenoceptor agonist dobutamine, was significantly attenuated in both young and mature GPR55−/− mice (Table 3). In young GPR55−/− mice, the dobutamine induced increase in dP/dt max was significantly attenuated compared to WT mice with a resultant reduction in the change in SV and consequently CO and EF (all P<0.01; Table 3). In addition, adrenoceptor mediated changes in dP/dt min were also significantly decreased in the young GPR55−/− mice (P<0.01; Table 3), suggesting an impaired lusitropic effect of dobutamine. The mature GPR55−/− mice were also characterised by a decreased response to dobutamine in terms of increases in SV, CO, EF and dP/dt max when compared to age-matched controls (P<0.001; Table 3). These changes occurred concomitant with a somewhat preserved lusitropic effect in terms of the rate of relaxation (i.e. dP/dt min), however EDV did not increase to a similar extent as that seen in the control group (P<0.001; Table 3). While mature GPR55−/− were characterised by reduced contractile reserve, this was no worse than that observed in young GPR55−/− mice.

Table 3. Effect of GPR55 gene deletion on contractile reserve in young (10 week old) and mature (8 month old) mice.

| Δ from baseline | 10 week old Mice | 8 month old Mice | ||

| WT (n = 15) | GPR55−/− (n = 15) | WT (n = 14) | GPR55−/− (n = 14) | |

| HR (BPM) | 111±4 | 95±4* | 94±10 | 101±8 |

| ESP (mmHg) | 19±5 | 2±3* | 15±2 | 8±5 |

| EDP (mmHg) | 0.9±0.5 | −0.4±0.3 | 0.1±0.3 | −0.2±0.3 |

| ESV (µL) | −1.3±0.6 | −2.5±0.8 | −3.8±0.9 | −0.4±0.3† |

| EDV (µL) | 3.7±0.6 | −0.1±0.9 | 5.5±1.3 | 1.6±0.6† |

| SV (µL) | 5.2±0.7 | 1.4±0.4* | 8.9±0.9* | 2.8±0.5† |

| SW (mmHg*µL) | 571±71 | 98±40* | 934±104* | 294±89† |

| CO (µL/min) | 2949±354 | 1810±245* | 5893±443* | 1541±278† |

| E a (mmHg/µL) | −2±0.5 | −1.2±0.3 | −0.9±0.2 | −2.5±1.4 |

| EF (%) | 14±2 | 8±2* | 14±1 | 7±1† |

| dP/dtmax (mmHg/s) | 6705±698 | 2098±306* | 5934±681 | 2586±738† |

| dP/dtmin (mmHg/s) | −2389±489 | −838±424* | −2384±247 | −1233±529 |

Contractile reserve, assessed by the change from baseline cardiac function in response to the α1/β1-adrenoceptor agonist dobutamine, was significantly attenuated in both young and mature mice with a gene deletion for GPR55. Data is expressed as mean±s.e.m. (n = 14–15).

*P<0.05 vs. WT (Young);

P<0.05 vs. WT (Mature).

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that genetic deletion of GPR55 in mice leads to the development of cardiac dysfunction with age and cardiac decompensation in response to adrenoceptor stimulation. While basal cardiac function was unaffected in young mice with a genetic deletion for GPR55, mature GPR55−/− mice, which would still be considered young adult mice and unlikely to be affected by senescent heart dysfunction [20], were characterised by significantly comprised systolic function. In particular, both load-independent (ESPVR & E max) and load-dependent (ejection fraction) indices of systolic function are significantly decreased in the mature GPR55−/− mice. Furthermore, mature GPR55−/− mice were also characterised by significant myocardial remodelling; including reductions in left ventricular free wall thickness, HW∶BW and ventricular cell number, and increased collagen deposition. Taken together, these changes are indicative of the presence of some form of cardiomyopathy (an all-encompassing term referring to alterations in both cardiac structure and function, that lead to a deterioration in cardiac function and ultimately heart failure), and possibly one that possesses several of the features of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) i.e. LV wall thinning, comprised systolic function, and reduced contractile reserve.

Possible explanations for the emerging systolic dysfunction observed in the mature GPR55−/− mice may include either impaired Ca2+ signalling in cardiomyocytes and/or altered central control of cardiac function. Studies have demonstrated GPR55 induced elevations in intracellular Ca2+ in both endothelial cells [21], and more recently cardiomyocytes [22]. In the latter study, Yu et al. [22] demonstrated that LPI applied both extra- and intracellularly induced elevations in [Ca2+]i in a GPR55 dependent manner. Furthermore, these findings led them to suggest that the receptor was expressed both at the sarcolemma and endo-lysosomal compartment, which may explain the extensive expression of GPR55 observed in ventricular tissue in the present study. As the previous study has demonstrated a role for GPR55 in Ca2+ signalling in the cardiomyocyte [22], it is possible that GPR55 gene deletion could adversely affect excitation-contraction coupling in the cardiomyocyte, and consequently the contractile ability of both the cell and myocardium as a whole. However, as none of the Ca2+ dependent indices of contractility (dP/dtmax, ESPVR or E max) differed between young GPR55−/− and WT mice this seems unlikely.

An alternative explanation may be an affect on the central control of cardiac contractility. It is well established that in the early stages of systolic dysfunction, compensatory mechanisms are initiated to maintain systolic function and meet metabolic demands, including sympathoexcitation (reviewed by [23]). In particular, catecholamines acting on β1-adrenoceptors on pacemaker cells of the sinoatrial node, serve to increase action potential firing rate and induce a positive chronotropic response [24], [25]. In the present study, mature GPR55−/− mice were not characterised by positive chronotropy (in an attempt to maintain systolic function), which may suggest impaired sympathetic control of the myocardium. In support of this, previous studies have demonstrated that activation of GPR55 leads to both increased excitability of dorsal root ganglion neurons [4], and enhanced pre-synaptic signalling in the hippocampus [26]. Although GPR55 expression in the nucleus tractus solitarius has yet to be demonstrated, it is possible that GPR55 may have a role in the regulation of synaptic transmission between preganglionic and postganglionic sympathetic efferents, and thus deletion of this GPCR may adversely affect sympathetic outflow. However, as basal systolic dysfunction appeared to be due to a chronic effect of GPR55 gene deletion (i.e. only evident at 8 months) and associated with significant ventricular remodelling it seems unlikely that GPR55 has a direct role in the control of cardiac function.

In the absence of a direct role for GPR55 in the control of cardiac contractility it is possible that this GPCR regulates the activity of another cardiac receptor responsible for regulating systolic function. Cardiac adrenoceptors, and β-adrenoceptors in particular, are the predominant GPCR in the heart and the chief modulators of both cardiac chronotropy and inotropy (reviewed by [27]). In the present study, all GPR55−/− mice exhibited significantly attenuated positive inotropic responses to (±)-dobutamine (an agonist which directly stimulates cardiac adrenoceptors) when compared to WT mice, suggesting a pivotal role for GPR55 in the regulation of adrenoceptor activity in the myocardium. This proposed maladaptive adrenergic signalling may in part explain the progressive cardiac dysfunction associated with these GPR55−/− mice. Accumulating evidence has shown that chronic stimulation of cardiac β-adrenoceptors activation leads to receptor phosphorylation via GPCR kinases i.e. βARK1 (desensitization), subsequent internalization of desensitized receptors via β-arrestin (downregulation), a loss of β-adrenoceptor mediated signalling, and finally the development of systolic heart failure (reviewed by [28]). Indeed, preservation of β-adrenergic signalling, via gene delivery of a βARK1 inhibitor, can reverse and/or prevent the development of cardiac dysfunction [29], [30]. Thus it's possible that the systolic dysfunction evident in the mature GPR55−/− mice may be due to the progressive loss of cardiac adrenoceptors. In line with this it might have been expected that the impaired positive inotropy to dobutamine observed in the young GPR55−/− mice would be further attenuated in the mature knockout mice, however this was not the case.

A possible explanation for this may involve α1-adrenoceptors, as although β1-adrenoceptors are thought to be primarily responsible for catecholamine induced increases in cardiomyocyte contractility, α1-adrenoceptors have been shown to induce cardiac contraction [31], [32], [33]. Furthermore, they have previously been shown to mediate part of the (±)-dobutamine induced positive inotropy in the rodent heart [34]. Although α1-adrenoceptor expression in healthy murine and human hearts is considerably less than that of the β-adrenoceptor subtypes [35], β-adrenoceptors are downregulated in heart failure whereas α1-adrenoceptors are not [36], [37]. Thus α1-adrenoceptor-mediated responses may contribute substantially to the compensatory positive inotropy in failing hearts.

In addition to altered cardiac function, mature GPR55−/− mice were also characterised by significant ventricular remodelling including decreased HW∶BW, a thinning of the LV wall, a reduction in myocardial cell number, and increased collagen deposition. While there is currently no direct evidence for a functional role for GPR55 in the control of fibroblast activity, a recent study has demonstrated that this receptor is expressed on cells, which likely include fibroblasts, in the adventitial layer of rodent vasculature [38], and that LPI is synthesised by transformed mouse BALB/3T3 fibroblasts [39], thus it is possible GPR55 may play a role in fibrogenesis. Indirectly, GPR55 may regulate fibrogenesis by altering the activity of another GPCR i.e. CB1, as it has recently been demonstrated that GPR55 can form a heteromer with CB1 allowing the former to alter the signalling mechanisms/activity of the latter, and vice versa [40]. Therefore it is possible that the profibrogenic effect of CB1, previously documented in an experimental model of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy [41], may be unimpeded in the mature mice lacking GPR55 thus resulting in the development of mild cardiac fibrosis. Finally, if mature GPR55−/− mice are in fact characterised by increased cardiac α1-adrenoceptor activity (as discussed in the previous section) then this may account for the increased myocardial collagen deposition as cardiac fibrosis has previously been demonstrated in mice overexpressing α1-adrenoceptors [42].

The observation that mature GPR55−/− mice are characterised by cardiac fibrosis seems somewhat incongruous with the significant reductions in both HW∶BW and LV wall thickness (indicative of a ‘lighter’ heart) observed in these animals. Therefore rather then increased fibrogenesis being the culprit for the increased cardiac collagen deposition, the latter may simply be ‘increased’ in the face of increased cell death/loss from the heart. In the present study, the left ventricles of mature GPR55−/− were characterised by a signficant reduction in stained nuclei indicating an increase in myocardial cell loss. However, as this data was acquired from H&E stained tissue, which is not specific for cardiomyocytes, we cannot conclusively say that all of the cell loss was due to cardiomyocyte apoptosis and additional studies are required. Previous work has suggested both anti-inflammatory [43] and anti-oxidant [44] roles for GPR55, thus loss of the receptor may lead to a chronic upregulation of both inflammation and oxidative stress in the mature GPR55−/−, both of which are chief instigators of cardiomyocyte cell death. However as the present study did not examine either the inflammatory or oxidative status of these animals these proposed mechanisms remain to be confirmed.

Exactly how the deletion of the GPR55 gene affects cardiac adrenoceptor signalling/function in the present study is unclear. However, accumulating evidence has demonstrated that co-localised GPCRs, not limited to adrenoceptor subtypes alone [45], [46], [47], but adrenoceptors and other GPCRs, can interact and regulate surface expression of each other via a process termed dimerization (reviewed by [48]). In particular, data from isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes has demonstrated cross-regulation between adrenergic and adenosinergic receptors, where stimulation of one inhibited the activity of the other and vice versa [49]. Furthermore, as previously discussed GPR55 can form heteromers with CB1 enabling both GPCR's to alter the signalling mechanisms/activity of the other [40]. In heart failure, the crosstalk between α-adrenoceptors and β-adrenoceptors is well established, in that expression of the former is elevated in the response to the downregulation of the latter as a means of sustaining positive inotropism of the contractile apparatus [50], [51]. While studies have yet to demonstrate co-expression of GPR55 and adrenoceptors within the same cardiomyocytes (as was demonstrated in murine vascular cells [38]), it is possible that there is some level of co-localisation in the myocardium that may facilitate crosstalk between these GPCRs influencing their function/expression, although this requires investigation. Finally, as the present study only examined the impact of GPR55 gene deletion on the function of adrenoceptors, we cannot rule out the possibilty that other GPCR's are similarly adversely affected. Furthermore, rather than GPR55 having a direct effect in terms of modulating other GPCR's function it is possible that the absence of this receptor may result in a more generalised adverse effect i.e. defective G protein-coupled signalling, culminating in the dysfunction of numerous GPCRs particularly those involved in stress-sensitive pathways. Thus the effect of GPR55 gene deletion on other GPCRs capable of inducing both inotropic and chronotropic responses should also be investigated in the future.

Conclusions

The present study has demonstrated that mature GPR55−/− mice are characterised by a progressive ventricular dysfunction. This intrinsic inability of the heart to maintain systolic function appears to be due to maladaptive adrenergic signalling, which may suggest some interplay/crosstalk between GPR55 and adrenoceptors and a possible role for GPR55 in the pathogenesis and/or progression of heart failure.

Acknowledgments

Heterozygous GPR55 knockout mice breeding pairs were kindly provided by AstraZeneca.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by a pump-priming grant from the Institute for Health & Wellbeing Research, the Robert Gordon University. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Sawzdargo M, Nguyen T, Lee DK, Lynch KR, Cheng R, et al. (1999) Identification and cloning of three novel human G protein-coupled receptor genes GPR52, ψGPR53 and GPR55: GPR55 is extensively expressed in human brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 64: 193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Henstridge CM, Balenga NA, Kargl J, Andradas C, Brown AJ, et al. (2011) Minireview: recent developments in the physiology and pathology of the lysophosphatidylinositol-sensitive receptor GPR55. Mol Endocrinol 25: 1835–1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ryberg E, Larsson N, Sjögren S, Hjorth S, Hermansson NO, et al. (2007) The orphan receptor GPR55 is a novel cannabinoid receptor. Br J Pharmacol 152: 1092–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lauckner JE, Jensen JB, Chen HY, Lu HC, Hille B, et al. (2008) GPR55 is a cannabinoid receptor that increases intracellular calcium and inhibits M current. PNAS 105: 2699–2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Waldeck-Weiermair M, Zoratti C, Osibow K, Balenga N, Goessnitzer E, et al. (2008) Integrin clustering enables anandamide-induced Ca2+ signaling in endothelial cells via GPR55 by protection against CB1-receptor-triggered repression. J Cell Sci 121: 1704–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Henstridge CM, Balenga NA, Schröder R, Kargl JK, Platzer W, et al. (2010) GPR55 ligands promote receptor coupling to multiple signalling pathways. Br J Pharmacol 160: 604–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pacher P, Bátkai S, Kunos G (2005) Cardiovascular pharmacology of cannabinoids. Handb Exp Pharmacol 168: 599–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. White R, Hiley CR (1997) A comparison of EDHF-mediated and anandamide-induced relaxations in the rat isolated mesenteric artery. Br J Pharmacol 122: 1573–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wagner JA, Varga K, Járai Z, Kunos G (1999) Mesenteric vasodilation mediated by endothelial anandamide receptors. Hypertension 33: 429–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Járai Z, Wagner JA, Varga K, Lake KD, Compton DR, et al. (1999) Cannabinoid-induced mesenteric vasodilation through an endothelial site distinct from CB1 or CB2 receptors. PNAS 96: 14136–14141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kunos G, Járai Z, Bátkai S, Goparaju SK, Ishac EJN, et al. (2000) Endocannabinoids as cardiovascular modulators. Chem Phys Lipids 108: 159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johns DG, Behm DJ, Walker DJ, Ao Z, Shapland EM, et al. (2007) The novel endocannabinoid receptor GPR55 is activated by atypical cannabinoids but does not mediate their vasodilator effects. Br J Pharmacol 152: 825–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Whyte LS, Ryberg E, Sims NA, Ridge SA, Mackie K, et al. (2009) The putative cannabinoid receptor GPR55 affects osteoclast function in vitro and bone mass in vivo. PNAS 106: 16511–16516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baker D, Pryce G, Davies WL, Hiley CR (2006) In silico patent searching reveals a new cannabinoid receptor. Trends Pharmacol Sci 27: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pertwee RG (2007) GPR55: a new member of the cannabinoid receptor clan? Br J Pharmacol 152: 984–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kapur A, Zhao P, Sharir H, Bai Y, Caron MG, et al. (2009) Atypical responsiveness of the orphan receptor GPR55 to cannabinoid ligands. J Biol Chem 284: 29817–29827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Romero-Zerbo SY, Rafacho A, Díaz-Arteaga A, Suárez J, Quesada I, et al. (2011) A role for the putative cannabinoid receptor GPR55 in the islets of Langerhans. J Endocrinol 211: 177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010) Animal research: Reporting in vivo experiments: The ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pacher P, Nagayama T, Mukhopadhyay P, Bátkai S, Kass DA (2008) Measurement of cardiac function using pressure-volume conductance catheter technique in mice and rats. Nat Protoc 3: 1422–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang B, Larson DF, Watson R (1999) Age-related left ventricular function in the mouse: analysis based on in vivo pressure-volume relationships. Am J Physiol 277: H1906–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bondarenko A, Waldeck-Weiermair M, Naghdi S, Poteser M, Malli R, et al. (2010) GPR55-dependent and -independent ion signalling in response to lysophosphatidylinositol in endothelial cells. Br J Pharmacol 161: 308–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yu J, Deliu E, Zhang XQ, Hoffman NE, Carter RL, et al. (2013) Differential activation of cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes by plasmalemmal vs intracellular G protein-coupled receptor 55. J Biol Chem 288: 22481–22492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krum H, Abraham WT (2009) Heart failure. Lancet 373: 941–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heubach JF, Rau T, Eschenhagen T, Ravens U, Kaumann AJ (2002) Physiological antagonism between ventricular beta 1-adrenoceptors and alpha 1-adrenoceptors but no evidence for beta 2- and beta 3-adrenoceptor function in murine heart. Br J Pharmacol 136: 217–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu J, Sirenko S, Juhaszova M, Ziman B, Shetty V, et al. (2011) A full range of mouse sinoatrial node AP firing rates requires protein kinase A-dependent calcium signaling. J Mol Cell Cardiol 51: 730–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sylantyev S, Jensen TP, Ross RA, Rusakov DA (2013) Cannabinoid- and lysophosphatidylinositol-sensitive receptor GPR55 boosts neurotransmitter release at central synapses. PNAS 110: 5193–5198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hata JA, Williams ML, Koch WJ (2004) Genetic manipulation of myocardial beta-adrenergic receptor activation and desensitization. J Mol Cell Cardiol 37: 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. White DC, Hata JA, Shah AS, Glower DD, Lefkowitz RJ, et al. (2000) Preservation of myocardial beta-adrenergic receptor signaling delays the development of heart failure after myocardial infarction. PNAS 97: 5428–5433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shah AS, White DC, Emani S, Kypson AP, Lilly RE, et al. (2001) In vivo ventricular gene delivery of a beta-adrenergic receptor kinase inhibitor to the failing heart reverses cardiac dysfunction. Circulation 103: 1311–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lin F, Owens WA, Chen S, Stevens ME, Kesteven S, et al. (2001) Targeted alpha(1A)-adrenergic receptor overexpression induces enhanced cardiac contractility but not hypertrophy. Circ Res 89: 343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Du XJ, Gao XM, Kiriazis H, Moore XL, Ming Z, et al. (2006) Transgenic alpha1A-adrenergic activation limits post-infarct ventricular remodeling and dysfunction and improves survival. Cardiovasc Res 71: 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mohl MC, Lismaa SE, Xiao X-H, Friedrich O, Wagner S, et al. (2011) Regulation of murine cardiac contractility by activation of α1A-adrenergic receptor-operated Ca2+ entry. Cardiovasc Res 91: 310–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ruffolo RR Jr, Messick K (1985) Effects of dopamine, (+/−)-dobutamine and the (+)- and (−)-enantiomers of dobutamine on cardiac function in pithed rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 235: 558–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Steinfath M, Chen YY, Lavický J, Magnussen O, Nose M, et al. (1992) Cardiac alpha 1-adrenoceptor densities in different mammalian species. Br J Pharmacol 107: 185–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bristow MR, Minobe W, Rasmussen R, Hershberger RE, Hoffman BB (1988) Alpha-1 adrenergic receptors in the nonfailing and failing human heart. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 247: 1039–1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jensen BC, Swigart PM, De Marco T, Hoopes C, Simpson PC (2009) α1-Adrenergic receptor subtypes in nonfailing and failing human myocardium. Circ Heart Fail 2: 654–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Daly CJ, Ross RA, Whyte J, Henstridge CM, Irving AJ, et al. (2010) Fluorescent ligand binding reveals heterogenous distribution of adrenoceptors and ‘cannabinoid-like’ receptors in small arteries. Br J Pharmacol 159: 787–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hong SL, Deykin D (1981) The activation of phosphatidylinositol-hydrolyzing phos-pholipase A2 during prostaglandin synthesis in transformed mouse BALB/3T3 cells. J Biol Chem 256: 5215–5219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kargl J, Balenga N, Parzmair GP, Brown AJ, Heinemann A, et al. (2012) The cannabinoid receptor CB1 modulates the signalling properties of the lysophosphatidylinositol receptor GPR55. J Biol Chem 287: 44234–44248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mukhopadhyay P, Rajesh M, Batkai S, Patel V, Kashiwaya Y, et al. (2010) CB1 cannabinoid receptors promote oxidative stress and cell death in murine models of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy and in human cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res 85: 773–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chaulet H, Lin F, Guo J, Owens WA, Michalicek J, et al. (2006) Sustained augmentation of cardiac α1A-adrenergic drive results in pathological remodelling with contractile dysfunction, progressive fibrosis and reactivation of matricellular protein genes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 40: 540–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cantarella G, Scollo M, Lempereur L, Saccani-Jotti G, Basile F, et al. (2011) Endocannabinoids inhibit release of nerve growth factor by inflammation-activated mast cells. Biochem Pharmacol 82: 380–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Balenga NAB, Aflaki E, Kargl J, Platzer W, Schröder R, et al. (2011) GPR55 regulates cannabinoid 2 receptor-mediated responses in human neutrophils. Cell Res 21: 1452–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Uberti MA, Hague C, Oller H, Minneman KP, Hall RA (2005) Heterodimerization with beta2-adrenergic receptors promotes surface expression and functional activity of alpha1D-adrenergic receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 313: 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhu WZ, Chakir K, Zhang S, Yang D, Lavoie C, et al. (2005) Heterodimerization of beta1- and beta2-adrenergic receptor subtypes optimizes beta-adrenergic modulation of cardiac contractility. Circ Res 97: 244–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ufer C, Germack R (2009) Cross-regulation between beta 1- and beta 3-adrenoceptors following chronic beta-adrenergic stimulation in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Br J Pharmacol 158: 300–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Milligan G (2009) G protein-coupled receptor hetero-dimerization: contribution to pharmacology and function. Br J Pharmacol 158: 5–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Komatsu S, Dobson JG Jr, Ikebe M, Shea LG, Fenton RA (2012) Crosstalk between adenosine A1 and β1-adrenergic receptors regulates translocation of PKCε in isolated rat cardiomyocytes. J Cell Physiol 227: 3201–3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dzimiri N (1999) Regulation of beta-adrenoceptor signaling in cardiac function and disease. Pharmacol Rev 51: 465–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Copik AJ, Ma C, Kosaka A, Sahdeo S, Trane A, et al. (2009) Facilitatory interplay in alpha 1a and beta 2 adrenoceptor function reveals a non-Gq signaling mode: implications for diversification of intracellular signal transduction. Mol Pharmacol 75: 713–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper.