Abstract

Small-molecule inhibitors that target bromodomains outside of the bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) sub-family are lacking. Here, we describe highly potent and selective ligands for the bromodomain module of the human lysine acetyl transferase CBP/p300, developed from a series of 5-isoxazolyl-benzimidazoles. Our starting point was a fragment hit, which was optimized into a more potent and selective lead using parallel synthesis employing Suzuki couplings, benzimidazole-forming reactions, and reductive aminations. The selectivity of the lead compound against other bromodomain family members was investigated using a thermal stability assay, which revealed some inhibition of the structurally related BET family members. To address the BET selectivity issue, X-ray crystal structures of the lead compound bound to the CREB binding protein (CBP) and the first bromodomain of BRD4 (BRD4(1)) were used to guide the design of more selective compounds. The crystal structures obtained revealed two distinct binding modes. By varying the aryl substitution pattern and developing conformationally constrained analogues, selectivity for CBP over BRD4(1) was increased. The optimized compound is highly potent (Kd = 21 nM) and selective, displaying 40-fold selectivity over BRD4(1). Cellular activity was demonstrated using fluorescence recovery after photo-bleaching (FRAP) and a p53 reporter assay. The optimized compounds are cell-active and have nanomolar affinity for CBP/p300; therefore, they should be useful in studies investigating the biological roles of CBP and p300 and to validate the CBP and p300 bromodomains as therapeutic targets.

Introduction

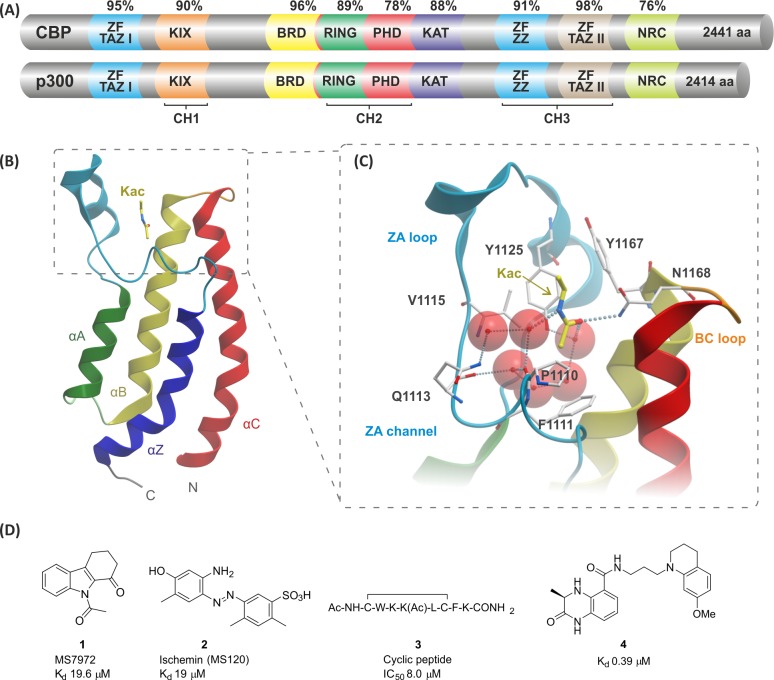

CBP and p300

The CREB (cyclic-AMP response element binding protein) binding protein (CBP) and E1A binding protein (p300) are ubiquitously expressed pleiotropic lysine acetyl transferases that play a key role as transcriptional co-activators in human cells.1−5 CBP and p300 possess nine conserved functional domains which bind to general and gene-specific transcription factors such as the hypoxia-inducible transcription factor (HIF) and the human tumor suppressor protein p53 (Figure 1A).6−15 Both CBP and p300 possess a single bromodomain (BRD) and a lysine acetyltransferase (KAT) domain, which are involved in the post-translational modification (PTM) and recruitment of histones and non-histone proteins.16−20 The BRD is an acetyl-lysine (Kac)-selective recognition module, whereas the KAT domain transfers an acetyl group from acetyl co-enzyme A to unmodified lysine side chains. These processes enable CBP/p300 to exert context-dependent regulation of transcriptional control. The sequence similarity between CBP and p300 is high in the conserved functional domains, with the BRD having 96% similarity (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Percent conservation and domain organization of human CBP (accession no. Q92793) and p300 (accession no. Q09472). Abbreviations: ZF TAZ 1 and 2, zinc finger transcription adaptor putative zinc finger-type; KIX, kinase-inducible domain interacting domain; BRD, bromodomain; RING, really interesting new gene; PHD, plant homeodomain; KAT, lysine acetyltransferase domain; ZF ZZ, zinc finger, ZZ-type; NRC, nuclear receptor co-activator interlocking domain; CH1–3, cysteine–histidine-rich regions 1–3. (B) CBP BRD-fold depicting the four α-helices (αZ, αA, αB, αC) and the ZA and BC loops that form the Kac binding pocket (derived from PDB 3P1C).27 (C) Structure of an acetyl lysine (yellow, only partial structure shown) and CBP BRD complex. Key interactions are shown, including the hydrogen bond (dotted lines) from the Kac carbonyl to N1168 and a water-mediated hydrogen bond from the Kac carbonyl to Y1125 (PDB 3P1C).27 (D) CBP BRD ligands with reported affinities.28−31

CBP and p53

Mutations of the p53 gene are common, with around 50% of human cancers encoding such mutations.21−23 In response to cellular stress, p53 undergoes PTMs of the C- and N-terminal regions, including acetylation at the C-terminal region, which results in changes in the p53-dependent activation of target genes leading to cell cycle arrest, senescence, or apoptosis.23−25 Lysine acetylation at lysine 382 (K382) of p53 is responsible for recruitment of CBP via its BRD, as shown by NMR titration of the CBP BRD with acetylated p53 peptides, and transfection of p53–/– cells with mutated p53.12 Additionally, in a p21 luciferase assay, the CBP-Kac interaction was shown to be crucial for p53-induced p21-mediated G1 cell cycle arrest.

Additionally, chemo- and radio-therapy can cause p53-mediated tissue damage of non-cancerous tissue, implying that p53 inhibition could be used to protect healthy tissue during these therapies.26 Thus, inhibition of the CBP BRD, and therefore p53-mediated p21 activation, has potential clinical applications.

In addition to its important tumor suppressor role, hyperactive p53 is implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord diseases, multiple sclerosis, ischemic brain injury, infectious and auto-immune diseases, and myocardial ischemia.32−37 Thus, inhibitors of p53 activity represent potential points of intervention in multiple diseases.

The CBP/p300 Bromodomain

Bromodomains are made up of ∼110 residues arranged in a characteristic structure made up of four α-helices (αZ, αA, αB, αC) connected by interhelical loops, termed the BRD fold (Figure 1B). Two loop regions (ZA and BC) form the largely hydrophobic Kac side-chain binding pocket, which in most BRDs binds the Kac N-acetyl group via a hydrogen bond between the acetyl carbonyl and the NH2 of a well-conserved asparagine residue (N1168 in CBP) and a water-mediated hydrogen bond from the acetyl carbonyl to the phenolic hydroxyl group of a conserved tyrosine (Y1125 in CBP) (Figure 1C).27,38−42

The 61 known BRDs encoded by the human genome can be clustered into sub-families on the basis of sequence and structural similarity.27 Selective inhibitors of these sub-families could serve as tools to elucidate the function of these proteins, and these have started to emerge in recent years. In particular, potent and selective inhibitors of the BRD and extra-terminal (BET) sub-family are now available from several different structural classes.43−49

Pioneering work on the inhibition of the CBP BRD emerged from the Zhou group, which reported several compounds with micromolar affinities (Figure 1D).28−30 The N-acetylindole MS7972 (compound 1, Kd = 19.6 μM) was shown to block the p53–CBP interaction at 50 μM in a competition assay.28 Ischemin (compound 2, Kd = 19 μM) inhibited p53-induced p21 activation in a luciferase reporter-gene assay (IC50 = 5 μM) and down-regulated p53 target gene expression under oxidative stress conditions.29 The cyclic peptide 3 has also been shown to bind the CBP BRD (Kd = 8 μM) and to inhibit p53 in the reporter assay.30 These compounds demonstrated the potential of CBP BRD inhibitors to modulate p53-mediated expression; however, they are not very potent or well characterized in terms of selectivity against other BRD-containing proteins. Recent reports also describe potent but non-selective or moderately selective CBP BRD inhibitors, including the sub-micromolar dihydroquinoxalinone inhibitor 4.31,50 We now report on the discovery of a series of potent and selective CBP/p300 BRD inhibitors, and we demonstrate their inhibition of the CBP–p53 interaction in cells. In addition, we demonstrate how compounds from the series bind in the Kac binding pocket using X-ray crystallography.

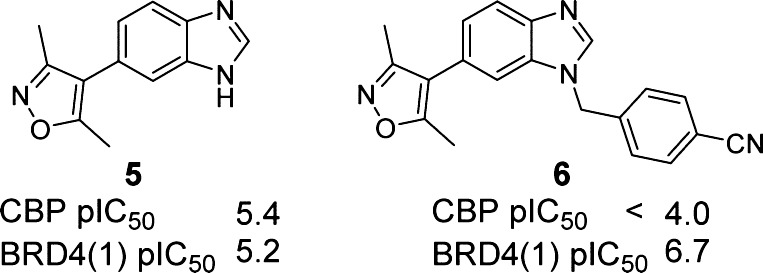

Our starting point for developing selective CBP/p300 inhibitors was the reported non-selective 3,5-dimethylisoxazole BRD inhibitor, 5 (Figure 2).43 Compound 5 was considered to be an attractive fragment to develop CBP BRD-selective inhibitors because it has a low molecular weight (213 Da) and reasonable LipE51 (3.5) and ligand efficiency (0.45)52,53 for CBP, and because it has various points useful for the introduction of diversity to the core scaffold. Our aim was to develop the scaffold of compound 5 with the goal of achieving potent compounds (Kd ≤ 0.1 μM) with selectivity over other BRD sub-families (≥30-fold) in vitro and displaying target-based cellular activity (IC50 ≤ 1 μM) to enable functional studies in cellular systems.47,54

Figure 2.

Starting point for this project. Compound 5 is a non-selective CBP and BRD4(1) inhibitor.43

Several reports describe 1,3-dimethylisoxazoles as potent inhibitors of the BET BRDs, including the benzimidazole compound 6.43,45,46,55 Therefore, it was recognized that obtaining selectivity for CBP/p300 over the BET BRDs could represent a substantial challenge. Compounds would therefore initially be screened against both CBP and BRD4(1) BRDs as representative examples of their respective sub-families. All in vitro screening and X-ray crystallography was carried out using recombinant BRDs as surrogates of full-length protein.

Results and Discussion

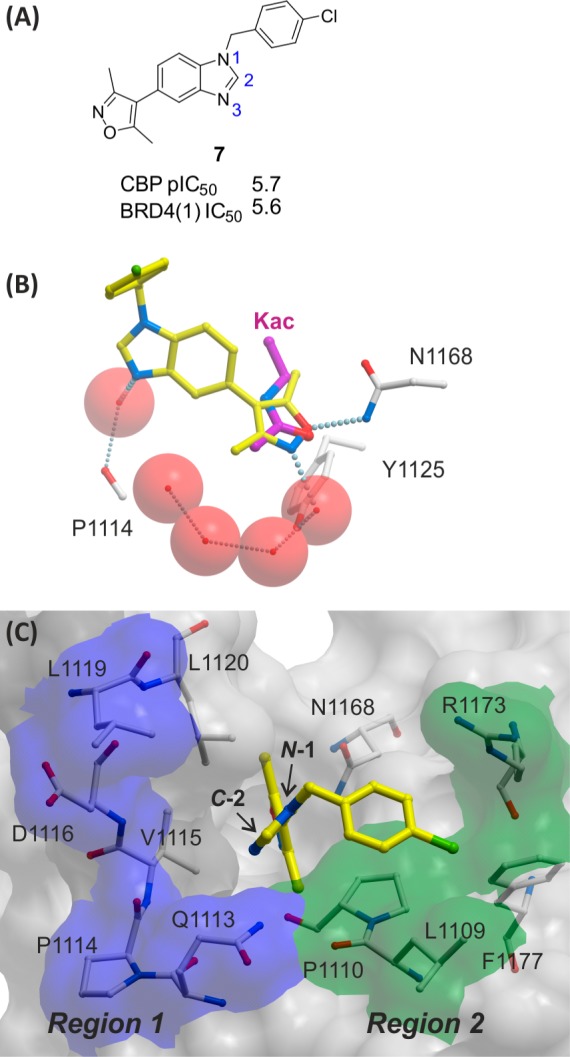

An X-ray crystal structure of the reported dimethylisoxazole compound 7 in complex with the CBP BRD illustrated two potential regions which substituted analogues of 5 could interact with, potentially leading to improvements in potency and selectivity (Figure 3).43 Figure 3B shows how the dimethylisoxazole of compound 7 mimics the key Kac binding interactions of the CBP BRD with an H-bond to N1168 and a water-mediated H-bond to Y1125. Figure 3C highlights the two regions targeted for analogues of 5. Region 1 is comprised of part of the “ZA-channel” and is largely hydrophobic, except for backbone carbonyls and the carboxamide of Q1113. Region 2 is analogous to the WPF shelf of BRD4(1).56 The surface is mostly hydrophobic but also has the side-chain of R1173 as a potential site for ligand interactions that could give selectivity for CBP over BRD4(1). On the basis of this analysis, it was anticipated that analogues of compound 5 which possessed substitution on the N-1 and C-2 may be able to interact with regions 1 and 2, with the aim of improving potency and selectivity. However, in initially library chemistry, other substitution patterns were also included in anticipation that unexpected interactions may occur.

Figure 3.

(A) Compound 7.43 (B) View from an X-ray crystal structure of compound 7 (carbon = yellow) bound to CBP BRD showing key H-bond interactions (PDB 4NR4). Kac (carbon = magenta) from PDB 3P1C is overlaid for reference. The dimethylisoxazole group is positioned to form an H-bond (gray dotted lines) to N1168 and a water-mediated H-bond to Y1125. The N-3 of the benzimidazole is positioned to form a water-mediated H-bond to the carbonyl of P1114. (C) Surface representation of CBP complexed with compound 7 with two shaded regions marked as potential areas to introduce functionality onto the benzimidazole scaffold in order to enhance potency and selectivity. Region 1 (blue) comprises the ZA channel which has points for interaction with polar functionality, such as the carbonyl on P1114, or the carboxamide of Q1113. Region 2 (green) is analogous to the “WPF shelf” in BRD4(1). R1173 was identified as a potential residue to interact with in an otherwise hydrophobic region.

Library Chemistry

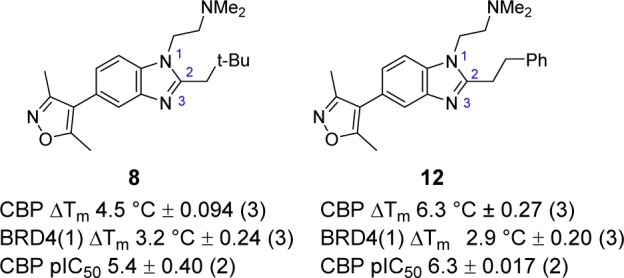

In order to identify more potent and selective leads for the CBP/p300 BRD, a set of Suzuki couplings was carried out in parallel with a commercially acquired 3,5-dimethylisoxazole-4-boronic acid pinacol ester and a set of heteroaryl bromides (Scheme 1). The heteroaryl bromides were chosen from the Pfizer compound collection and were selected so that products obtained would have Lipinski rule of 5 compliant properties (e.g., clog P < 5 and MW < 500), with the majority of the compounds targeted at around clog P = 2–4 and MW = 300–400.57 The set chosen consisted of 101 heteroaryl bromides, which had a variety of substituents on the heterocyclic core in order to maximize diversity. Reactions and workups were carried out in parallel, and products were purified by automated preparative HPLC. Product purity was assessed by UV, evaporative light scattering detection, and MS. The 101 reactions delivered 83 target compounds in sufficient yield and purity for biochemical testing using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF, ΔTm), a high-throughput assay used as a surrogate for displacement assays.47 From this initial library, compound 8 emerged as a promising hit, with ΔTm = 4.5 °C against CBP and 3.2 °C against BRD4(1) at a compound concentration of 10 μM (Figure 4).

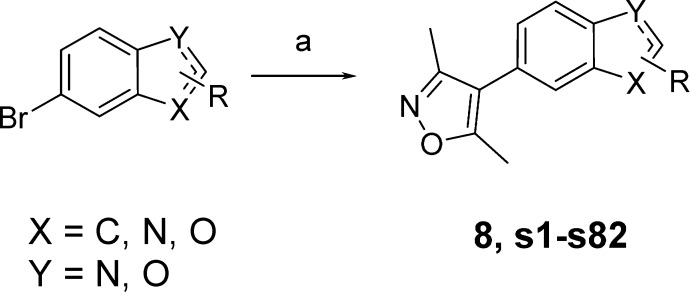

Scheme 1. Parallel Suzuki Couplings.

Reagents and conditions: 3,5-dimethylisoxazole-4-boronic acid pinacol ester, Pd(dppf)Cl2 [dppf = 1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene], NaHCO3, 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME)/H2O, 100 °C, 5–93%. See Supporting Information (SI) for specific structures of products s1–s82.

Figure 4.

CBP-selective hits from initial parallel chemistry. Mean values ± SEM (number of measurements).

To improve potency and selectivity for CBP, analogues of compound 8 varied in the C-2 position were then prepared using parallel synthesis for the coupled reduction/cyclization step (Scheme 2). Dithionite-mediated reduction of the aryl nitro group of compound 11 in the presence of R-aldehydes efficiently afforded the desired benzimidazole targets which were purified by automated HPLC. The most promising compound from this set was compound 12, with an increased ΔTm = 6.3 °C (4.5 °C for compound 8) against CBP while maintaining BRD4(1) potency at ΔTm = 2.9 °C (3.2 °C for compound 8) (Figure 4). A pIC50 = 6.3 was measured for compounds 8 and 12, using a peptide displacement AlphaScreen (amplified luminescent proximity homogeneous assay screen).58 The CBP potency represents a significant improvement on compound 5 (pIC50 = 5.4). These results implied that differential 1,2,-disusbtitution of benzimidazoles could lead to compounds with improved potency and selectivity. It was therefore decided to optimize the substituents on this template via focused synthesis to further improve potency and selectivity.

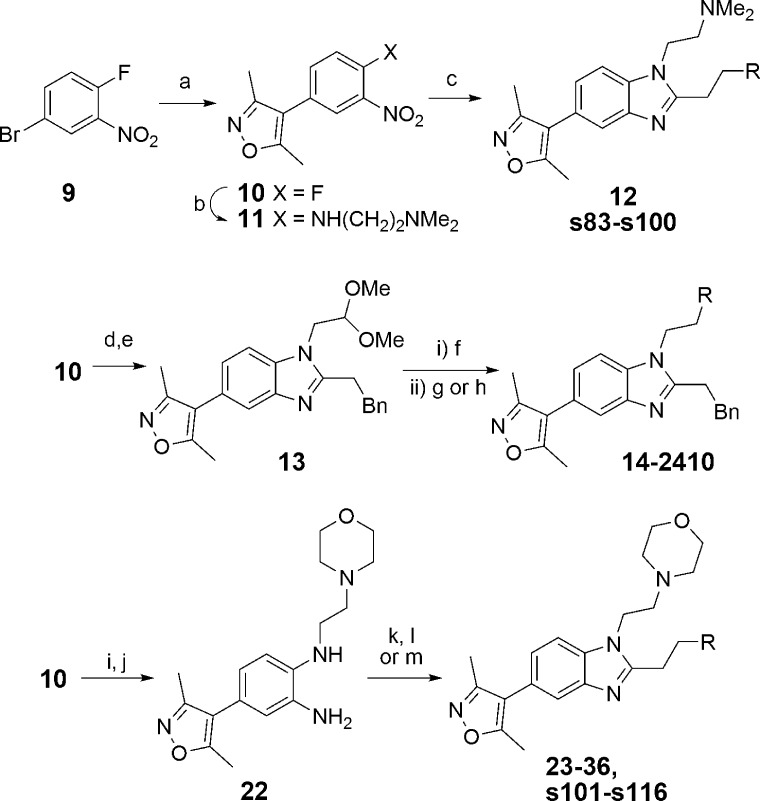

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Trisubstituted Benzimidazoles.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 3,5-dimethylisoxazole-4-boronic acid pinacol ester, Pd(dppf)Cl2, NaHCO3, DME/H2O, 73%; (b) N,N-dimethylethylenediamine, N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), tetrahydrofuran (THF), 86%; (c) RCH2CH2CHO, Na2S2O4, H2O, EtOH, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 80 °C, 8–54% (see SI for specific structures of products s83–s100); (d) NH2CH2CH(OMe)2, DMSO; (e) PhCH2CH2CHO, Na2S2O4, H2O, MeOH, 65% (two steps); (f) CF3CO2H, H2O, CH2Cl2, microwave 150 °C, 99%; (g) amine (RH), NaBH(OAc)3, THF, 35–86%; (h) Amine (RH), NaCNBH3, AcOH, MeOH, 42%; (i) 4-(2-aminoethyl)morpholine, DIPEA, THF, 94%; (j) Na2S2O4, H2O, EtOH, 80 °C, 87%; (k) RCH2CH2CO2H, T3P, DIEPA, EtOAc, microwave, 150 °C, 31–62% (l) RCH2CH2CO2H, T3P, DIPEA, EtOAc, reflux, 15–63%; (m) RCH2CH2CO2H, 6 M aq. HCl, microwave 210 °C, 16–55% (see SI for specific structures of s101–s116).

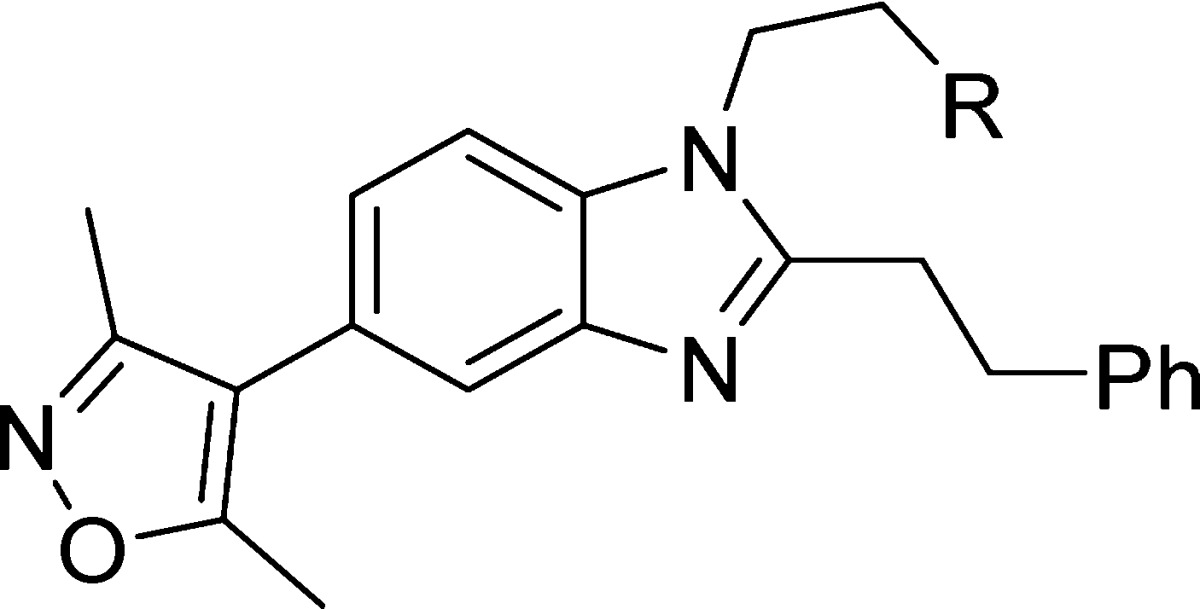

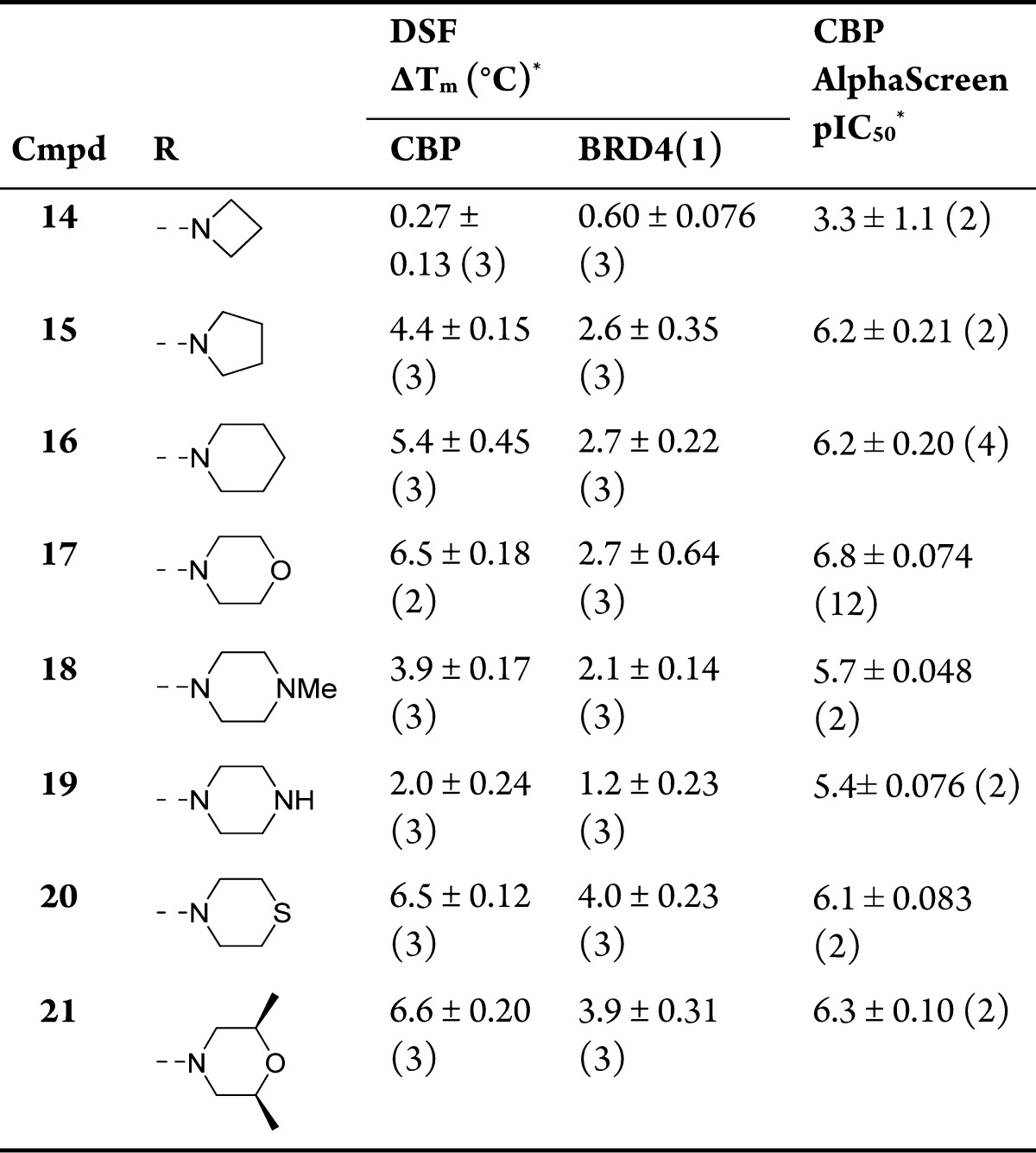

N-1 Amine Optimization

Late-stage variation of the amino moiety was achieved by reductive amination of an aldehyde, obtained from the dimethyl acetal 13 (Scheme 2). The compounds obtained were screened by DSF and AlphaScreen (Table 1). Comparison of the screening techniques confirmed that DSF was an effective tool for ranking the potency of compounds.59 The correlation was high enough that the general and operationally simple DSF assay was felt to be a useful surrogate for the more complex AlphaScreen in further efforts to increase the potency of the compounds. The results suggest that simple cyclic amino analogues 14–16 (CBP ΔTm = 0.27–5.4 °C, pIC50 = 3.3–6.2) are not as potent as the dimethylamino variant 12 (CBP ΔTm = 6.3 °C, pIC50 = 6.3). However, the morpholine-containing analogue 17 gave a slight improvement with ΔTm values of 6.5 and 2.7 °C for CBP and BRD4(1) respectively and was potent in CBP AlphaScreen (pIC50 = 6.8). Piperazines 18 and 19, thiomorpholine 20, and substituted morpholine derivative 21 were less potent and/or less selective for CBP over BRD4(1). With the best balance of CBP potency and BRD4(1) selectivity in the primary assays, the binding constants (Kd) of compound 17 were then determined using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) (Table 2). The Kd value of 17 was measured at 0.32 μM against CBP, 0.35 μM against p300, and 0.94 μM against BRD4(1). These results indicate that the ITC measured selectivities of compound 17 with respect to BRD4(1) were only 3.0-fold and 2.7-fold for CBP and p300, respectively. This showed that further work needed to be done in order to obtain sufficient selectivity for CBP/p300.

Table 1. Structure–Activity Relationships for CBP and BRD4(1) Binding As Determined by DSF and AlphaScreen for N-1 Analoguesa.

Values are given as mean ± SEM (number of measurements).

Table 2. ITC Results for Compound 17.

| CBP | p300 | BRD4(1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kd (μM) | 0.32 ± 0.094 | 0.35 ± 0.082 | 0.95 ± 0.044 |

Selectivity Optimization

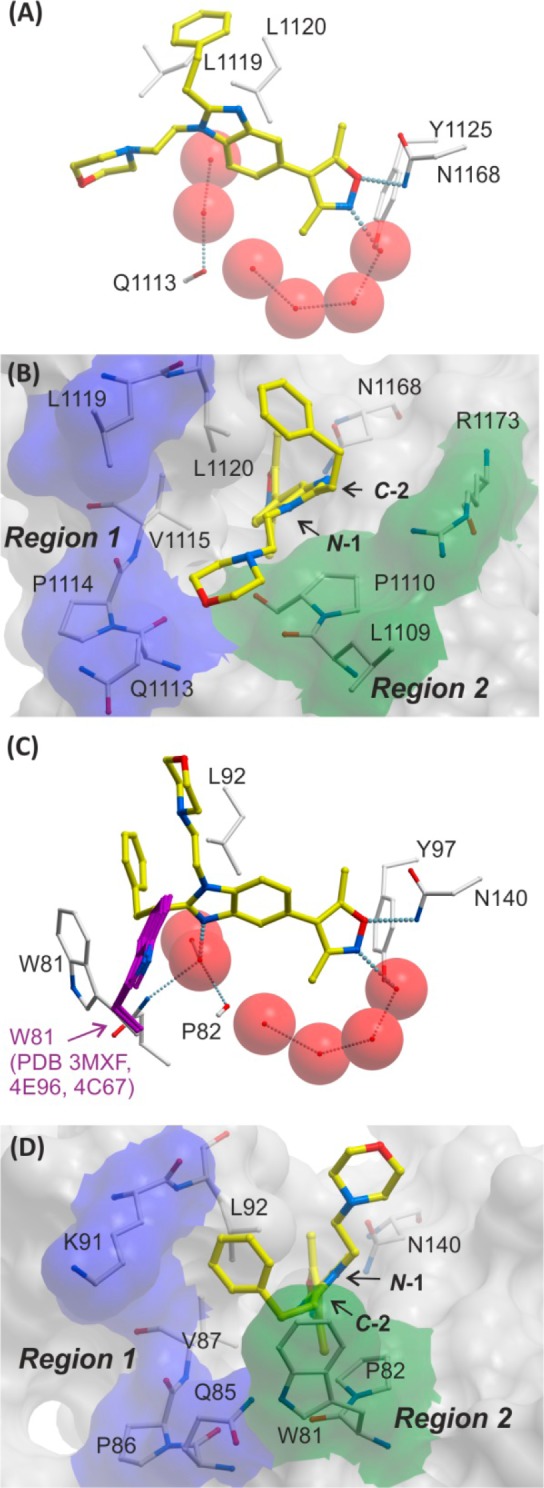

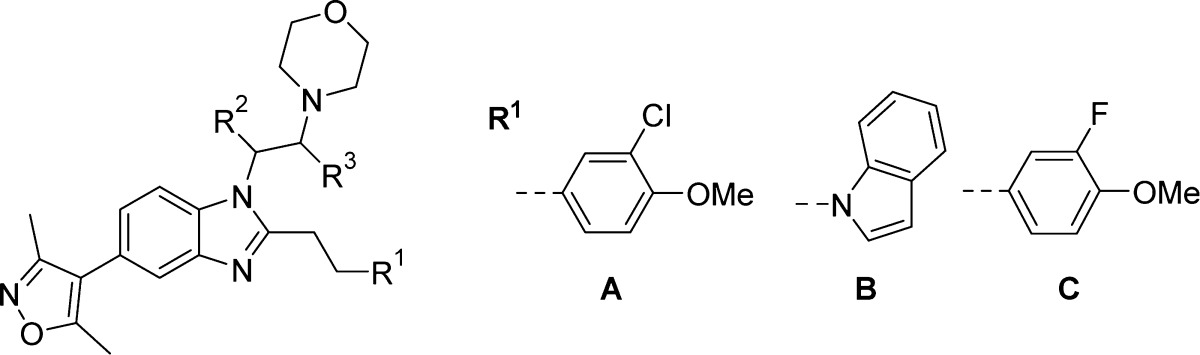

In order to identify potential avenues for improving the selectivity of the series, high-resolution crystal structures were determined for compound 17 in complex with CBP and BRD4(1) (Figure 5). The results suggested that differences in the observed binding modes could be exploited to improve selectivity. In the CBP complex, the morpholine moiety of compound 17 occupies an area in the ZA channel, between the targeted regions 1 and 2. The phenethyl group of compound 17 appears to be in a hydrophobic region on the edge of the pocket. In BRD4(1), compound 17 adopts a flipped binding mode with respect to side-chain orientation; notably, a water-mediated hydrogen bond from the NH2 of the Q85 carboxamide to the benzimidazole N-3 nitrogen is apparent. The morpholine moiety points out toward solvent, whereas the phenethyl group fits into a hydrophobic region comprising the WPF shelf and ZA channel of BRD4(1).

Figure 5.

Views from X-ray crystal structures of compound 17 complexed to CBP (PDB 4NR5) and BRD4(1) (PDB 4NR8) BRDs. For CBP: (A) view showing the H-bond interactions between the oxygen of the isoxazole of 17 and N1168 (3.02 Å), and between the nitrogen of the isoxazole and a water (2.75 Å) (water = red spheres), and (B) surface view with shaded regions indicating regions targeted by N-1 and C-2 benzimidazole substitution according to Figure 3. For BRD4(1): (C) view showing the H-bond interactions between the oxygen of the isoxazole of 17 and N140 (3.08 Å), and between the nitrogen of the isoxazole and a water (2.91 Å); the H-bond between the benzimidazole N-3 of 17 and a water molecule is also shown (2.71 Å), and W81 from other ligand-bound structures (carbon = magenta) is overlaid to illustrate the shift in W81 side-chain position (PDB 3MXF, 4E96, 4C67),47,49,60 and (D) surface view.

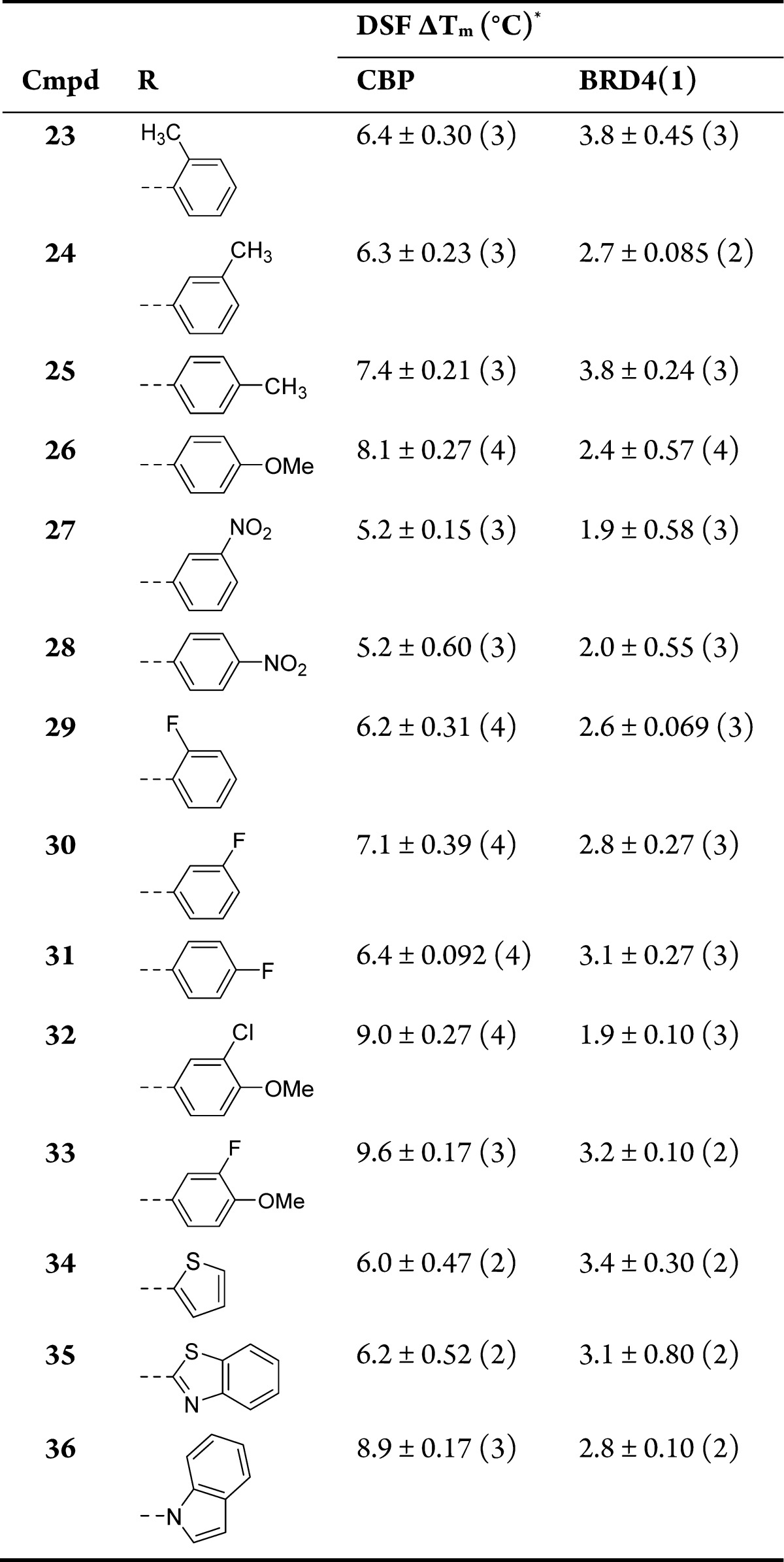

C-2 Aryl Optimization

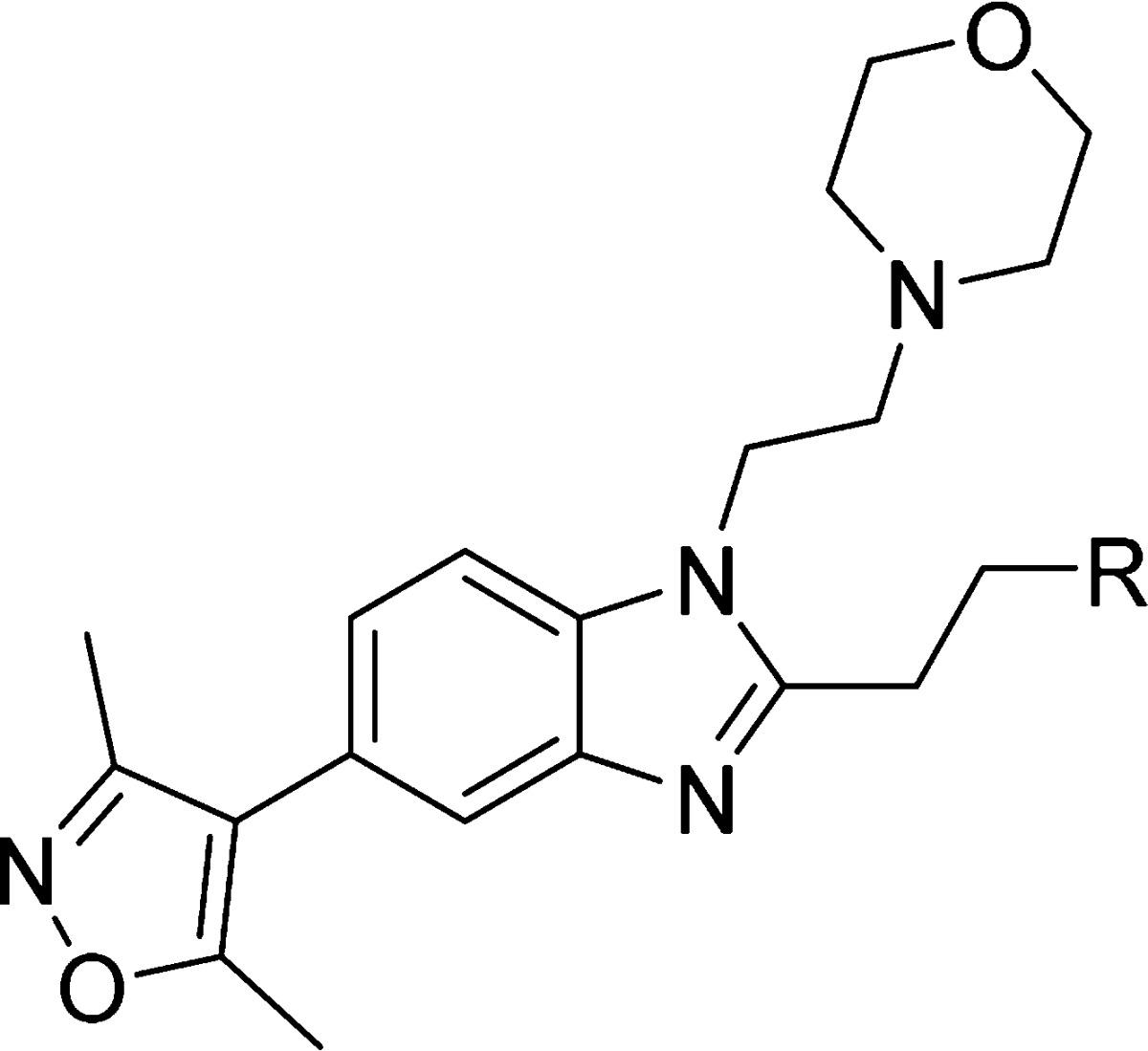

As the phenylethyl moiety of compound 17 was observed to occupy different regions in the CBP and BRD4(1) structures, it was decided to explore the synthesis of a diverse set of compounds with substituted aryl rings to test effects on selectivity. Additionally, it was considered that the C-2 linked aryl group would be amenable to late-stage variation, allowing for an efficient synthesis of analogues. The targeted compounds were synthesized according to Scheme 2. Thus, the phenylenediamine compound 22 was formed by an SNAr reaction of compound 10 followed by dithionite-mediated nitro reduction. Precursor 22 was then reacted with substituted carboxylic acids under dehydrating conditions (propylphosphonic anhydride (T3P) or 6 M aqueous HCl) to yield the target compounds 23–36 (Table 3) and s101–s116 (see SI).

Table 3. Structure–Activity Relationships for CBP and BRD4(1) Binding As Determined by DSF Assay for a Selection of the C-2 Analoguesa.

Values are given as mean ΔTm ± SEM (number of measurements).

The DSF results for compounds 23–25 (Table 3) suggest that an electron-donating methyl group on the aryl ring is tolerated, with the para-methyl analogue 25 showing an increased ΔTm for CBP of 7.4 °C. The more strongly electron-donating para-methoxy group in compound 26 gave a further increase with ΔTm = 8.1 °C, and showed a larger window over BRD4(1). Conversely, the strongly electron-withdrawing nitro groups in compounds 27 and 28 were detrimental to CBP binding. The results for compounds 29–31 indicated that halogens are tolerated on the phenyl ring, with the meta-substituted fluorine analogue 30 appearing optimal, with ΔTm = 7.1 °C against CBP. Compounds 32 and 33 combined the para-methoxy and meta-halogen moieties, resulting in a further increase in CBP ΔTm to 9.0 and 9.6 °C, respectively. Analogues 34–36 demonstrated that the phenyl group can be substituted for a heteroaryl group, with the electron-rich indole-containing compound 36 representing the optimal compound from this set with ΔTm = 8.9 °C against CBP. It was encouraging that increases in CBP potency for the best compounds in Table 3 were not accompanied by increases in BRD4(1) potency.

Since the four aryl analogues 26, 32, 33, and 36 all indicated improved potency in the ΔTm assay, the pIC50 against CBP was determined using AlphaScreen (Table 4). The results were in the range of 7.0–7.3, indicating that these were all promising analogues warranting more detailed biophysical investigations on their selectivity for CBP over BRD4(1). Thermodynamic parameters for binding to CBP and BRD4(1) were therefore determined by ITC for this set of compounds. The results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Determination of pIC50 and Kd of Selected C-2 Analogues by AlphaScreen and ITC.

| ITC

Kd (μM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | CBP AlphaScreen pIC50a | CBP | BRD4(1) | Selectivity |

| 26 | 7.0 ± 0.17 (4) | 0.050 ± 0.0039 | 0.55 ± 0.0033 | 11-fold |

| 32 | 7.2 ± 0.0080 (2) | 0.028 ± 0.0024 | 0.48 ± 0.038 | 17-fold |

| 33 | 7.0 ± 0.69 (2) | 0.022 ± 0.0017 | 0.44 ± 0.025 | 20-fold |

| 36 | 7.3 ± 0.18 (2) | 0.030 ± 0.0021 | 0.66 ± 0.055 | 22-fold |

Values are given as mean pIC50 ± SEM (number of measurements).

Gratifyingly, the substituted aryl analogues are more potent against CBP than compound 17, with Kd in the range of 0.022–0.050 μM. Additionally, the selectivity for CBP over BRD4(1), as determined by ITC Kd values, had improved to 11–22-fold for these analogues, with the best results being those of compound 36, which had a CBP Kd = 30 nM and was 22-fold selective over BRD4(1). Although the selectivity had improved, efforts continued in order to achieve a greater window over BRD4(1). To achieve this objective, the obtained crystal structures (Figure 5) were employed in order to further guide design.

Indole Analogue

The structure of compound 17 complexed to BRD4(1) reveals a water-mediated hydrogen bond from the benzimidazole N-3 to the protein backbone (P82) and to the carboxamide side chain of Q85; analogous interactions are absent in the equivalent CBP structure (Figure 5A,C). These observations imply that, in the absence of other effects, replacing the benzimidazole ring with an indole that does not contain the nitrogen in compound 17 should negatively impact BRD4(1) binding, but not CBP.

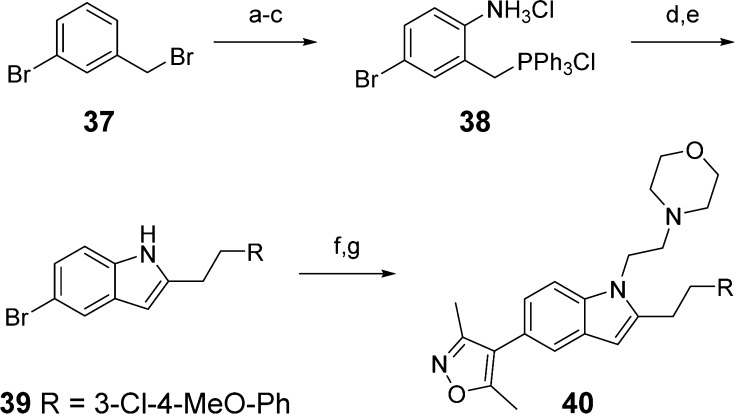

The synthesis of the targeted indole analogue 40 is shown in Scheme 3. Aminophosphonium salt 38 was synthesized according to known procedures61 and then acylated. Base-promoted cyclization yielded the indole intermediate 39, which was alkylated and cross-coupled to give the target molecule 40.

Scheme 3.

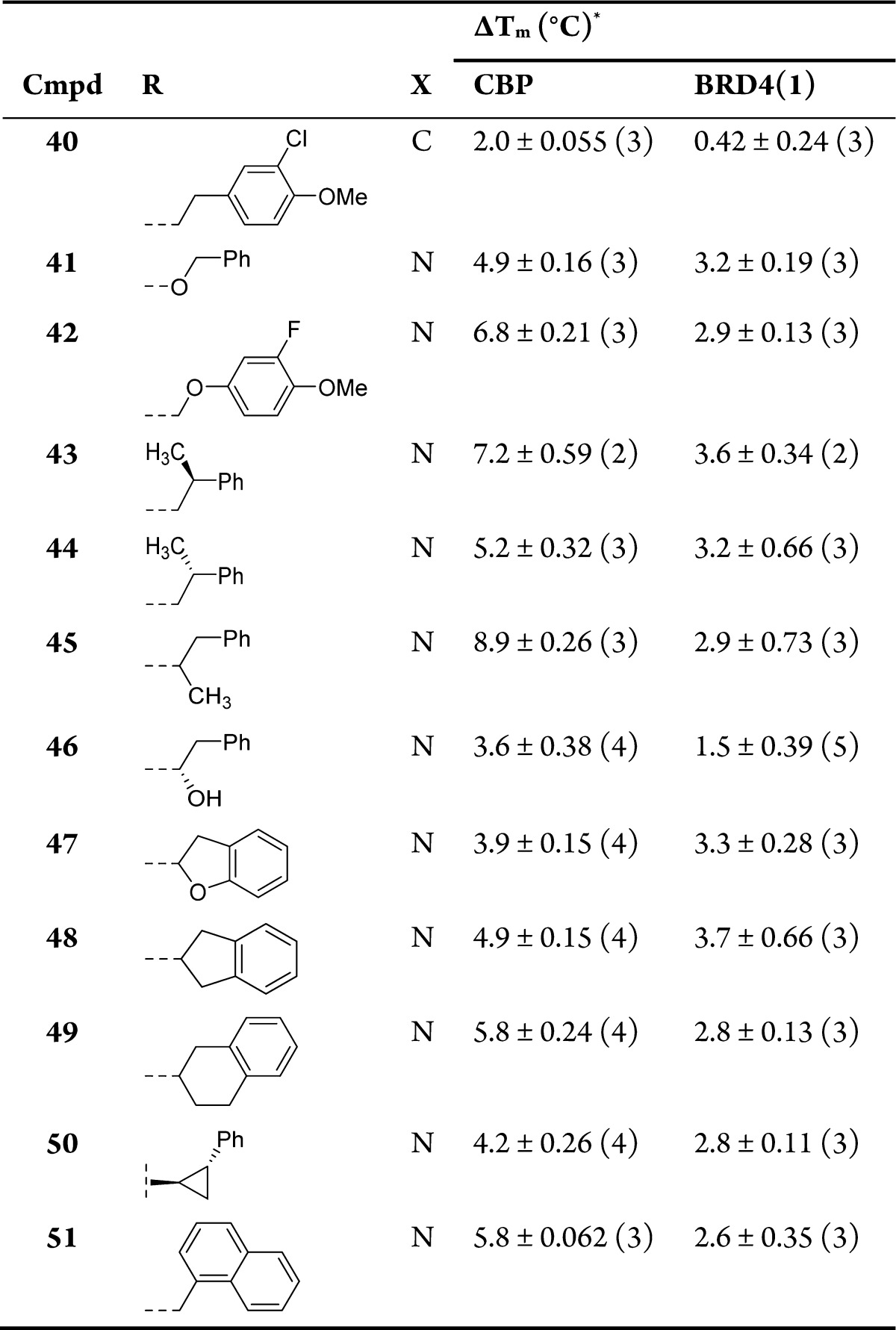

As hoped, indole 40 was completely inactive against BRD4(1) with a ΔTm < 1 °C (Table 5). Disappointingly, it also gave a significantly lower ΔTm for CBP (2.0 °C) than the equivalent benzimidazole analogue 32. This implies that although the crystal structure of compound 17 bound to CBP shows no H-bond to the protein backbone, interaction of the electron-poor benzimidazole with the CBP protein is favored over that of the electron-rich indole.

Table 5. Structure–Activity Relationships for CBP and BRD4(1) Binding As Determined by ΔTm Assay for the Indole Target and Conformationally Constrained/Polar C-2 Analogues.

Values are given as mean ΔTm ± SEM (number of measurements).

Conformationally Constrained Analogues

The ethylene moiety of compound 17, which links the benzimidazole C-2 and phenyl groups, sits in a hydrophobic region in BRD4(1) and partly occupies the space termed the WPF shelf, which contains a tryptophan residue protruding out of the pocket (Figure 5C,D). The orientation of W81 in BRD4(1) in the complex with compound 17 is unusual when compared to other BRD4(1) ligand-bound structures (Figure 5C) and shows how BRD4(1) can accommodate hydrophobic groups in orientations other than those that occupy the typical WPF shelf.47,48,55 It was envisaged that polar and/or constrained linkers could reduce the affinity for BRD4(1). An increase in polarity may disfavor binding in the hydrophobic WPF region, while BRD4(1) may be less able to accommodate conformationally constrained linkers with reduced degrees of freedom, as they would be less able to avoid a steric clash with the WPF shelf by bond rotation.

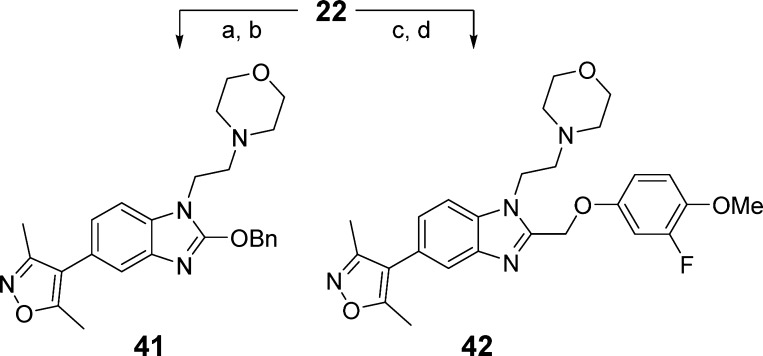

Synthesis of the oxygen-linked targets is shown in Scheme 4. 1,1′-Carbonyldiimidazole (CDI)-mediated cyclization of phenyleneiamine 22 gave a 2-oxo precursor. Alkylation tended to favor N-substitution, but use of Ag2CO3 as base gave a mixture of N- and O-alkylated isomers, which could be separated to yield the desired target 41. Compound 22 was also used to prepare a hydroxymethyl precursor, which was reacted with a phenol using Tsunodu’s Mitsunobu conditions to yield target compound 42.62 Analogues 43–51, which possess additional substitution or conformational constraints on the ethylene moiety linking the benzimidazole and aryl groups, were synthesized by methodology analogous to that described in Scheme 2 (see SI).

Scheme 4. Synthesis of O-Linked Targets.

Reagents and conditions: (a) CDI, THF, reflux, 78%; (b) BnBr, Ag2CO3, toluene, 80 °C (18%); (c) 2-hydroxyacetic acid, 6 M aq. HCl, microwave 180 °C, 62%; (d) 3-fluoro-4-methoxyphenol, 1,1′-(azodicarbonyl)dipiperidine, P(n-Bu)3, CH2Cl2, 67%.

Disappointingly, screening using DSF showed no improvement in potency and selectivity for the O-linked analogues (41, 42) or conformational constrained compounds (43–51) over the analogous ethylene linked compounds (Table 5). With no indication of an improvement in selectivity, attention shifted to modification of the N-1 ethylene linker between the morpholine moiety and the N-1 position of the benzimidazole ring. It was again proposed that by constraining the conformation of the linker it would force unfavorable interactions in BRD4(1) due to steric interactions with the WPF shelf or by changing the orientation of the phenethyl group (Figure 5).

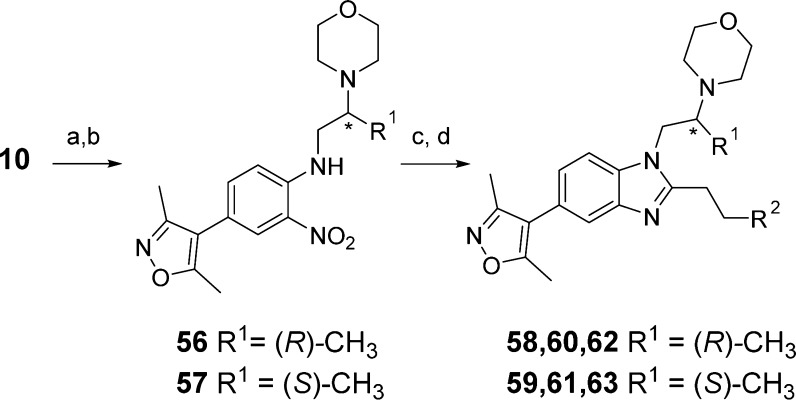

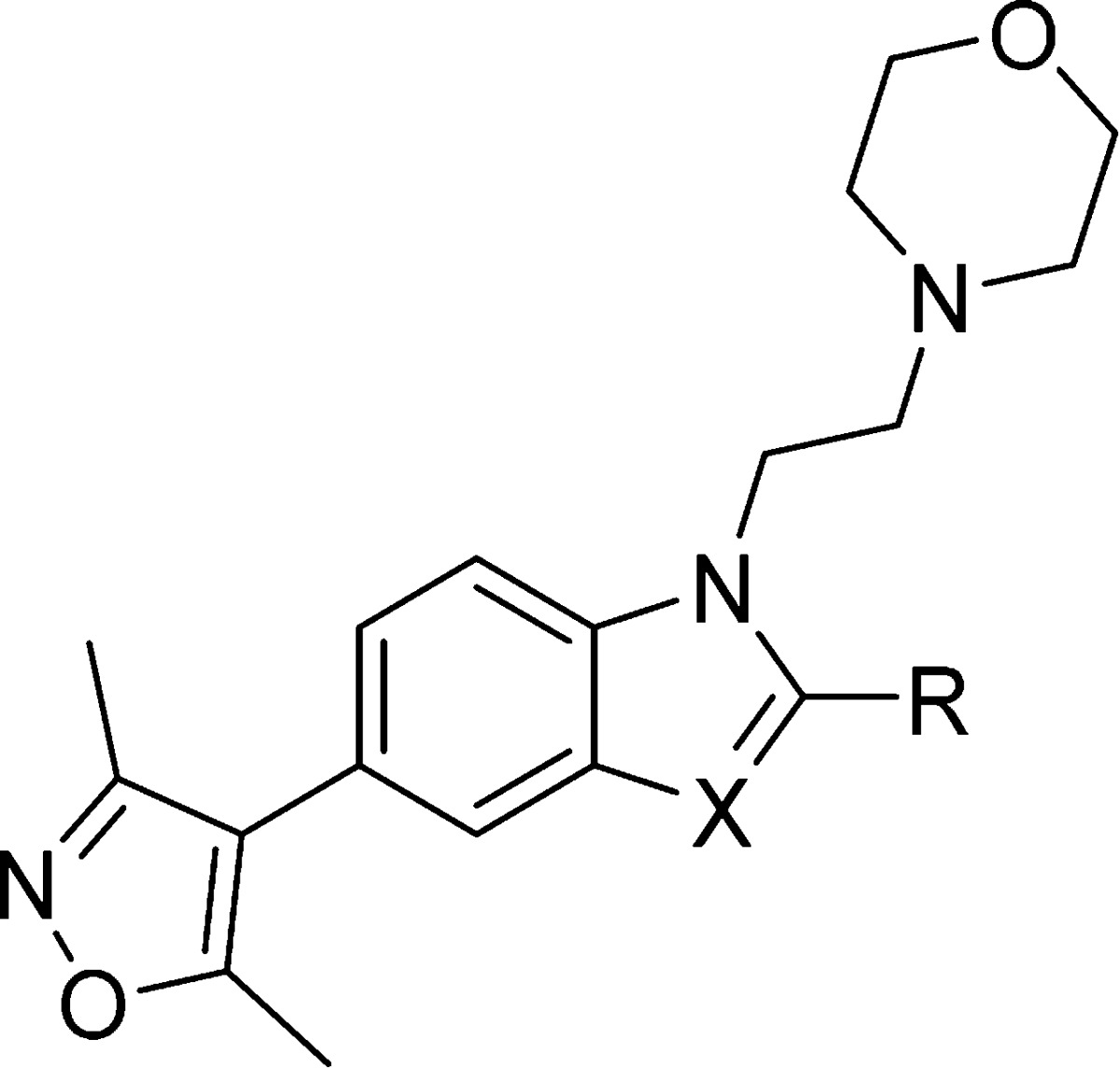

Racemic analogues containing methyl groups on the N-1 ethylene linker (compounds 52–55) were prepared according to the methodology in Scheme 2. Screening results for these compounds are shown in Table 6. While methyl groups were not well tolerated next to the benzimidazole ring (compounds 52 and 54), they were tolerated next to the morpholine ring (compounds 53 and 55). The ΔTm and AlphaScreen values for the racemic compounds were encouraging enough to prompt synthesis of the single enantiomers, according to the route shown in Scheme 5. Commercially acquired chiral (R)- and (S)-1,2-diaminopropane reacted via SNAr with 10, predominantly at the less sterically hindered 1-amino group. This reaction gave an inseparable 4:1 mixture of isomers in favor of the desired compound. The morpholine ring was formed by alkylation with 2-bromoethyl ether. At this stage, the isomeric compounds could be separated by chromatography. Nitro-reduction and benzimidazole formation yielded the target compounds 58–63 in >99% ee, as determined by chiral HPLC.

Table 6. Structure–Activity Relationships for CBP and BRD4(1) Binding As Determined by DSF and AlphaScreen for Conformationally Constrained N-1 Linkers.

| R | ΔTm (°C)a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | 1 | 2 | 3 | CBP | BRD4(1) | CBP AlphaScreen pIC50a |

| 52 | A | CH3 | H | 5.8 ± 0.092 (3) | 1.9 ± 0.27 (2) | ND |

| 53 | A | H | CH3 | 9.4 ± 0.58 (5) | 2.0 ± 0.33 (3) | 7.6 ± 0.046 (2) |

| 54 | B | CH3 | H | 5.6 ± 0.29 (3) | 1.2 ± 0.070 (2) | ND |

| 55 | B | H | CH3 | 9.1 ± 0.44 (5) | 2.4 ± 0.25 (3) | 7.0 ± 0.15 (2) |

| 58 | A | H | (R)-CH3 | 7.5 ± 0.10 (3) | 2.0 ± 0.040 (2) | 6.3 ± 0.10 (2) |

| 59 | A | H | (S)-CH3 | 9.7 ± 0.31 (4) | 1.8 ± 0.71 (4) | 7.1 ± 0.049 (2) |

| 60 | B | H | (R)-CH3 | 7.2 ± 0.21 (3) | 2.3 ± 0.25 (2) | 6.3 ± 0.054 (2) |

| 61 | B | H | (S)-CH3 | 11 ± 0.17 (3) | 3.3 ± 0.57 (2) | 7.3 ± 0.050 (2) |

| 62 | C | H | (R)-CH3 | 7.3 ± 0.058 (3) | 3.4 ± 0.54 (2) | 6.7 ± 0.065 (2) |

| 63 | C | H | (S)-CH3 | 10 ± 0.11 (3) | 2.3 ± 0.25 (2) | 7.2 ± 0.033 (2) |

Compounds are racemic except where indicated. Values are given as mean ± SEM (number of measurements).

Scheme 5. Route to Single Enantiomers.

Reagents and conditions: (a) (R)- or (S)-1,2-diaminopropane dihydrochloride, K2CO3, DMF, 80 °C, 38–41%; (b) 2-bromoethyl ether, K2CO3, DMF, 70 °C, 27–37%; (c) Na2S2O4, H2O, EtOH, 80 °C; (d) R2CH2CH2CO2H, T3P, EtOAc, reflux, 38–52%.

Gratifyingly, the (R)- and (S)-enantiomers displayed clearly different affinities for CBP, with the (S)-form giving a large ΔTm of around 10 °C and high potency (pIC50 > 7.0) in AlphaScreen for the three aryl variants tested (compounds 59, 61, and 63). The (S)-enantiomers were therefore analyzed by ITC, and the results are shown in Table 7. The Kd for these analogues indicated high potency (0.021–0.039 μM). The most selective compound, 59, was shown to be 40-fold selective for CBP over BRD4(1) and 250-fold over BRD4(2). Compound 59 was also potent against p300, with Kd = 0.032 μM (see SI for details). Introducing a chiral methyl onto the morpholino-ethylene moiety had the desired effect of improving selectivity over BRD4(1) while maintaining CBP/p300 potency, and validated the design strategy of introducing conformational restraints into the ethylene linker of the target compounds.

Table 7. ITC Determination of Kd for the Binding of (S)-Methyl Analogues to CBP and BRD4(1).

| ITC Kd (μM) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | CBP | BRD4 | CBP selectivity |

| 59 | 0.021 ± 0.0022 | 0.85 ± 0.096a | 40-fold |

| 5.2 ± 0.14b | 250-fold | ||

| 61 | 0.026 ± 0.0026 | 0.53 ± 0.074a | 20-fold |

| 63 | 0.039 ± 0.0029 | 0.61 ± 0.054a | 16-fold |

BRD4(1).

BRD4(2).

Compound 59 was crystallized with CBP (Figures 6). Although the binding mode is similar to that observed for compound 17 (Figure 5A,B), the orientation of the ethylene-linked aryl group is different. In the complex with CBP and 59, there is an apparent cation−π interaction between the guanidino group of R1173 and the aryl ring. This is made possible because the R1173 side chain moves with respect to the conformation observed in the complex with compound 17, forming an induced binding pocket for the aryl ring (Figure 6B). This is consistent with the observation that electron-donating groups on the aryl ring were preferred for CBP binding, as these should have a stronger interaction with the positively charged R1173. The chlorine atom on the aryl ring of 59 sits in a hydrophobic section of the induced pocket between V1174 and F1177. The chiral methyl group sits below the aryl ring, possibly helping to lock the ring in position. The induced pocket has been reported for another series of CBP inhibitors which also form cation−π interactions between the inhibitors and the R1173 side chain. The combined findings perhaps suggest that the interaction of aromatic groups with R1173 represents an important feature of potent CBP inhibitors.31

Figure 6.

(A) View from X-ray crystal structure of compound 59 (carbon = yellow) complexed to CBP, showing the H-bond interaction between the oxygen of the isoxazole of 59 and N1168 (3.08 Å), and the nitrogen of the isoxazole and a water molecule (2.83 Å) (water molecules are red spheres) (PDB 4NR7). (B) Surface view from same with shaded regions indicating regions which were targeted by N-1 and C-2 benzimidazole substitution according to the strategy described in Figure 3. Overlaid with crystal structure of compound 17 (carbon = magenta) complexed to CBP. The aryl group of compound 59 and R1173 form an apparent cation−π interaction.

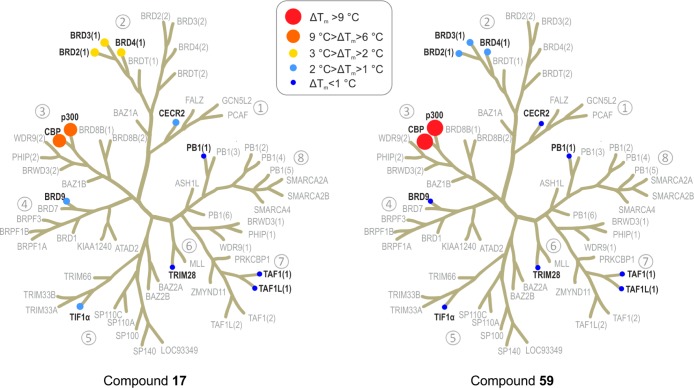

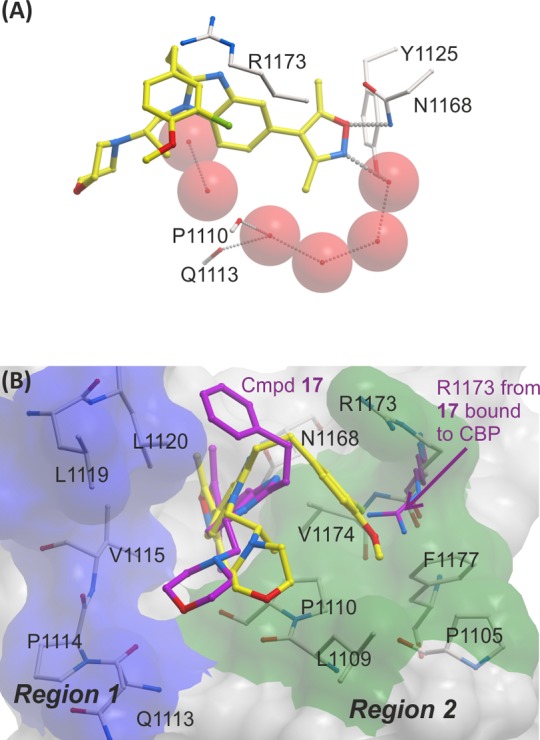

In order to investigate the wider selectivity of inhibitors in the series, compounds 17 and 59, were screened against representative members of the other BRD sub-families using DSF (Figure 7). The values obtained correlated well with available AlphaScreen IC50 values (Spearman rank correlation, ρ 0.94, see SI). In the DSF panel, both compounds were selective for CBP/p300 BRDs. Compound 59 was particularly selective, with no significant ΔTm (>2 °C) against any other BRDs apart from the BETs: BRD2(1), BRD3(1), and BRD4(1) with ΔTm between 1 and 2 °C.

Figure 7.

Selectivity assessment of compounds 17 and 59 against human BRD families using DSF (ΔTm) binding assays. The 10 screened targets are labeled in black on the phylogenetic tree of the human BRD family; BRDs that were not part of the screening panel are in gray.

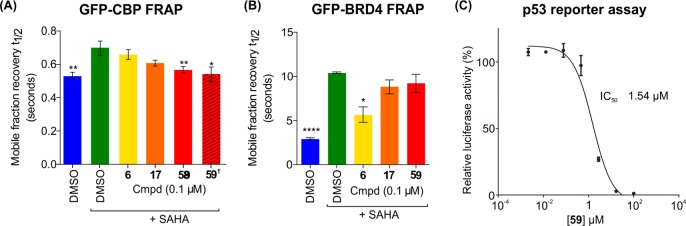

Cellular Assays

On-target cellular efficacy for the CBP BRD was investigated using a fluorescence recovery after photo-bleaching (FRAP) assay (Figure 8A).63 HeLa cells transfected with a construct encoding a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged multimerized (3×) CBP BRD showed a rapid recovery time (t1/2 = 0.59 s) upon photobleaching of a small area of the nucleus. The broad-spectrum histone deacetylase inhibitor, SAHA, was used to increase the extent of global lysine acetylation, so increasing recovery time (t1/2 = 0.79 s) and expanding the assay window. An equivalent increase in the recovery time was not observed in cells transfected with a CBP BRD construct carrying the N1168F mutation, (see SI, Figure S1), consistent with the critical role of N1168 in Kac binding, and supporting the proposal that the increase in assay window due to SAHA addition is due to BRD binding. Treatment of SAHA-treated cells with compound 59 at 0.1 μM was sufficient to reduce FRAP recovery times back to unstimulated levels (t1/2 = 0.60 s), equivalent to the N1168F mutant. The effect is indicative of displacement of the CBP BRD from acetylated chromatin. The weaker and less selective CBP inhibitor, compound 17 and the BRD4(1)-selective inhibitor 6 were unable to significantly alter the FRAP at this concentration (t1/2 = 0.66 and 0.74 s, respectively). Conversely, in an equivalent assay using GFP-tagged BRD4, only the BRD4-selective inhibitor 6 significantly affected FRAP recovery times, with CBP inhibitors 17 and 59 showing no significant effect at 0.1 μM (Figure 8B) demonstrating the specificity of the compounds on their respective targets.

Figure 8.

Time dependence of fluorescent recovery in the bleached area in Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) assays with GFP-tagged 3 × CBP BRD construct (A) and full-length BRD4 (B). Half-times of fluorescence recovery (t1/2) are shown as bars, which are color-coded: blue, DMSO control; green, DMSO + SAHA; yellow, 0.1 μM BRD4(1)-selective inhibitor 6; orange, 0.1 μM compound 17; and red, 0.1 μM compound 59. †N1168F mutant (red hashed). Bars represent the mean ± SEM t1/2 calculated from two or three independent experiments. Significance of groups compared with the control was determined by t-tests: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. (C) Inhibition of p53-driven luciferase activity by compound 59. RKO cells were transfected with p53 reporter plasmid. Cells were treated with compound 59 at the indicated concentrations for 24 h and subsequently with doxorubicin at 0.3 μM for 16 h. Each value is the mean ± SEM of a representative experiment done in eight replicates.

To investigate the effect of compound 59 on the CBP–p53 association in a cellular context, a luciferase reporter assay for p53 induction was used. Doxorubicin induced p53 activity was effectively inhibited by compound 59 in a dose-dependent manner (IC50 = 1.5 μM) (Figure 8C). These results suggest that the CBP BRD inhibitor 59 inhibits the CBP co-activation of p53 target genes in cells and demonstrate the utility of 59 in a cellular context. The effect on p53 regulation by compound 59 is most likely due to its CBP inhibition, not its weaker BRD4 inhibition, as the much more potent BRD4 inhibitor, JQ1, shows p53-mediated effects at similar concentrations.64,65 However, it was not possible to analyze the effects of less selective CBP inhibitors in the p53 reporter gene assay due to the confounding effects of BRD4 inhibition on p53.64,66

To test if CBP BRD inhibition was cytotoxic at the concentrations where on-target efficacy was observed, U2OS osteosarcoma cells were treated with compound 59 for 24 h, and cell viability was determined using a standard 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) turnover assay (see SI, Figure S2). This showed that compound 59 had modest cytotoxicity (CC50 = 80 μM), well above the levels where on-target efficacy was observed in the FRAP and p53 reporter gene assays. After 72 h of treatment with compound 59, cytotoxicity in U2OS cells increased (CC50 = 8.1 μM), consistent with the effect of BRD4 inhibition at higher concentration as previously reported.67

In order to investigate if compound 59 could also serve as a probe in animals, it was tested in in vitro ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) assays (see SI, Table S6). In a human liver microsome (HLM) stability assay, no compound was detected after 60 min, implying that the metabolism of compound 59 may be too rapid for it to be useful as an oral in vivo probe.

The selectivity of compound 59 against other target classes was assessed using wide ligand profiling (see SI, Table S7).68 When tested against 136 GPCR, ion channel, enzyme, and kinase targets, compound 59 showed IC50 < 1 μM only for the adrenergic receptors α2C (0.11 μM) and α2A (0.57 μM), phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) (0.15 μM), and platelet-activating factor (PAF) (0.54 μM).

Conclusions

In summary, potent, selective, and cell-active inhibitors of the CBP/p300 BRD have been described. There is a lack of potent and selective inhibitors that target bromodomains outside the BET sub-family. The optimal compound, 59, is a highly potent inhibitor of the CBP and p300 BRDs (Kd = 0.021 and 0.032 μM, respectively) and is 40-fold selective for CBP over BRD4(1), and highly selective over the other BRD sub-family members screened. In cells, 59 inhibits CBP-mediated p53 activity in a luciferase-based reporter assay and has low cytotoxicity. Compound 59 is expected to be useful in furthering the understanding of the role of the CBP/p300 BRD in transcriptional regulation. In the context of p53, compound 59 could serve to validate the potential of CBP BRD inhibitors as a clinical approach in the treatment of disorders related to hyperactive p53 transcription and could serve as a starting point for developing bioavailable in vivo probes and clinical candidates.

Acknowledgments

The SGC is a registered charity (number 1097737) that receives funds from AbbVie, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, Genome Canada, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Lilly Canada, the Novartis Research Foundation, the Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Innovation, Pfizer, Takeda, and the Wellcome Trust [092809/Z/10/Z]. P.F. and S.P. are supported by a Wellcome Trust Career-Development Fellowship (095751/Z/11/Z). The authors thank the European Union, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), and the British Heart Foundation for funding. We also thank Diamond Light Source for beamtime (proposals mx8421 and mx6391), and the staff of beamlines I02 and I24 for assistance with crystal testing and data collection; Cerep for ligand profiling and ADME assays; Prof. Darren Dixon and Peter Clark for help with ee determinations; and Yue Zhu at Changchun Discovery Sciences Ltd for synthesis of selected monomers.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures and characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Goodman R. H.; Smolik S. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 1553–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo N.; Goodman R. H. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 13505–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkhoven E. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004, 68, 1145–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan H. M.; La T. N. B. J. Cell Sci. 2001, 114, 2363–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford D. C.; Kasper L. H.; Fukuyama T.; Brindle P. K. Epigenetics 2010, 5, 9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arany Z.; Huang L. E.; Eckner R.; Bhattacharya S.; Jiang C.; Goldberg M. A.; Bunn H. F.; Livingston D. M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996, 93, 12969–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert B. L.; Bunn H. F. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998, 18, 4089–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallio P. J.; Okamoto K.; O’Brien S.; Carrero P.; Makino Y.; Tanaka H.; Poellinger L. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 6573–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ema M.; Hirota K.; Mimura J.; Abe H.; Yodoi J.; Sogawa K.; Poellinger L.; Fujii-Kuriyama Y. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 1905–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrero P.; Okamoto K.; Coumailleau P.; O’Brien S.; Tanaka H.; Poellinger L. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 402–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung A. L.; Wang S.; Klco J. M.; Kaelin W. G.; Livingston D. M. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 1335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujtaba S.; He Y.; Zeng L.; Yan S.; Plotnikova O.; Sachchidanand; Sanchez R.; Zeleznik-Le N. J.; Ronai Z.; Zhou M. M. Mol. Cell 2004, 13, 251–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman S. R. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 2773–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avantaggiati M. L.; Ogryzko V.; Gardner K.; Giordano A.; Levine A. S.; Kelly K. Cell 1997, 89, 1175–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delvecchio M.; Gaucher J.; Aguilar-Gurrieri C.; Ortega E.; Panne D. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013, 20, 1040–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister A. J.; Kouzarides T. Nature 1996, 384, 641–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogryzko V. V.; Schiltz R. L.; Russanova V.; Howard B. H.; Nakatani Y. Cell 1996, 87, 953–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W.; Roeder R. G. Cell 1997, 90, 595–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.; Scolnick D. M.; Trievel R. C.; Zhang H. B.; Marmorstein R.; Halazonetis T. D.; Berger S. L. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 1202–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi K.; Herrera J. E.; Saito S.; Miki T.; Bustin M.; Vassilev A.; Anderson C. W.; Appella E. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 2831–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B.; Lane D.; Levine A. J. Nature 2000, 408, 307–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A. J. Cell 1997, 88, 323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prives C.; Hall P. A. J. Pathol 1999, 187, 112–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutts A. S.; La Thangue N. B. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 331, 778–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon-Vargas D.; Ronai Z. Carcinogenesis 2002, 23, 541–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudkov A. V.; Komarova E. A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 331, 726–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippakopoulos P.; Picaud S.; Mangos M.; Keates T.; Lambert J.-P.; Barsyte-Lovejoy D.; Felletar I.; Volkmer R.; Müller S.; Pawson T.; Gingras A.-C.; Arrowsmith C. H.; Knapp S. Cell 2012, 149, 214–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachchidanand; Resnick-Silverman L.; Yan S.; Mutjaba S.; Liu W.-j.; Zeng L.; Manfredi J. J.; Zhou M.-M. Chem. Biol. 2006, 13, 81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borah J. C.; Mujtaba S.; Karakikes I.; Zeng L.; Muller M.; Patel J.; Moshkina N.; Morohashi K.; Zhang W.; Gerona-Navarro G.; Hajjar R. J.; Zhou M.-M. Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 531–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerona-Navarro G.; Yoel-Rodriguez; Mujtaba S.; Frasca A.; Patel J.; Zeng L.; Plotnikov A. N.; Osman R.; Zhou M. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 2040–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney T. P. C.; Filippakopoulos P.; Fedorov O.; Picaud S.; Cortopassi W. A.; Hay D. A.; Martin S.; Tumber A.; Rogers C. M.; Philpott M.; Wang M.; Thompson A. L.; Heightman T. D.; Pryde D. C.; Cook A.; Paton R. S.; Müller S.; Knapp S.; Brennan P. E.; Conway S. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6126–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak S. K.; Panesar P. S.; Kumar H. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 2627–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. D.; Ghiani C. A.; Kim J. Y.; Liu A. X.; Sandoval J.; DeVellis J.; Casaccia-Bonnefil P. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 6118–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan W.; Zhu X.; Ladenheim B.; Yu Q.-S.; Guo Z.; Oyler J.; Cutler R. G.; Cadet J. L.; Greig N. H.; Mattson M. P. Ann. Neurol. 2002, 52, 597–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong L.-Z.; Zhao X.-Y.; Zhang H.-L. Neurosci. Bull. 2010, 26, 232–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro J.; Kikuchi S.; Shinpo K.; Kishimoto R.; Tsuji S.; Sasaki H. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007, 85, 395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrancosta N.; Garino C.; Laras Y.; Quéléver G.; Pierre P.; Clavarino G.; Kraus J.-L. Drug Dev. Res. 2005, 65, 43–9. [Google Scholar]

- Filippakopoulos P.; Knapp S. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 2692–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidler L. R.; Brown N.; Knapp S.; Hoelder S. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 7346–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez R.; Zhou M.-M. Curr. Opin. Drug Discovery Dev. 2009, 12, 659–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L.; Zhang Q.; Gerona-Navarro G.; Moshkina N.; Zhou M.-M. Structure 2008, 16, 643–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L.; Zhou M. M. FEBS Lett. 2002, 513, 124–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay D.; Fedorov O.; Filippakopoulos P.; Martin S.; Philpott M.; Picaud S.; Hewings D. S.; Uttakar S.; Heightman T. D.; Conway S. J.; Knapp S.; Brennan P. E. MedChemComm 2013, 4, 140–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinjha R. K.; Witherington J.; Lee K. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 33, 146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamborough P.; Diallo H.; Goodacre J. D.; Gordon L.; Lewis A.; Seal J. T.; Wilson D. M.; Woodrow M. D.; Chung C. W. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 587–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewings D. S.; Wang M. H.; Philpott M.; Fedorov O.; Uttarkar S.; Filippakopoulos P.; Picaud S.; Vuppusetty C.; Marsden B.; Knapp S.; Conway S. J.; Heightman T. D. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 6761–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippakopoulos P.; Qi J.; Picaud S.; Shen Y.; Smith W. B.; Fedorov O.; Morse E. M.; Keates T.; Hickman T. T.; Felletar I.; Philpott M.; Munro S.; McKeown M. R.; Wang Y. C.; Christie A. L.; West N.; Cameron M. J.; Schwartz B.; Heightman T. D.; La Thangue N.; French C. A.; Wiest O.; Kung A. L.; Knapp S.; Bradner J. E. Nature 2010, 468, 1067–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewings D. S.; Fedorov O.; Filippakopoulos P.; Martin S.; Picaud S.; Tumber A.; Wells C.; Olcina M. M.; Freeman K.; Gill A.; Ritchie A. J.; Sheppard D. W.; Russell A. J.; Hammond E. M.; Knapp S.; Brennan P. E.; Conway S. J. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 3217–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish P. V.; Filippakopoulos P.; Bish G.; Brennan P. E.; Bunnage M. E.; Cook A. S.; Federov O.; Gerstenberger B. S.; Jones H.; Knapp S.; Marsden B.; Nocka K.; Owen D. R.; Philpott M.; Picaud S.; Primiano M. J.; Ralph M. J.; Sciammetta N.; Trzupek J. D. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 9831–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov O.; Lingard H.; Wells C.; Monteiro O. P.; Picaud S.; Keates T.; Yapp C.; Philpott M.; Martin S. J.; Felletar I.; Marsden B. D.; Filippakopoulos P.; Muller S.; Knapp S.; Brennan P. E. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 462–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckmans T.; Edwards M. P.; Horne V. A.; Correia A. M.; Owen D. R.; Thompson L. R.; Tran I.; Tutt M. F.; Young T. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 4406–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz M. D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 5980–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins A. L.; Groom C. R.; Alex A. Drug Discovery Today 2004, 9, 430–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards A. M.; Bountra C.; Kerr D. J.; Willson T. M. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 436–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson M. A.; Prinjha R. K.; Dittmann A.; Giotopoulos G.; Bantscheff M.; Chan W. I.; Robson S. C.; Chung C. W.; Hopf C.; Savitski M. M.; Huthmacher C.; Gudgin E.; Lugo D.; Beinke S.; Chapman T. D.; Roberts E. J.; Soden P. E.; Auger K. R.; Mirguet O.; Doehner K.; Delwel R.; Burnett A. K.; Jeffrey P.; Drewes G.; Lee K.; Huntly B. J. P.; Kouzarides T. Nature 2011, 478, 529–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicodeme E.; Jeffrey K. L.; Schaefer U.; Beinke S.; Dewell S.; Chung C. W.; Chandwani R.; Marazzi I.; Wilson P.; Coste H.; White J.; Kirilovsky J.; Rice C. M.; Lora J. M.; Prinjha R. K.; Lee K.; Tarakhovsky A. Nature 2010, 468, 1119–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C. A.; Lombardo F.; Dominy B. W.; Feeney P. J. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2001, 46, 3–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpott M.; Yang J.; Tumber T.; Fedorov O.; Uttarkar S.; Filippakopoulos P.; Picaud S.; Keates T.; Felletar I.; Ciulli A.; Knapp S.; Heightman T. D. Mol. BioSyst. 2011, 7, 2899–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compounds in Table 1 were screened by AlphaScreen and DSF against a number of BRD targets. Spearman analysis shows a good rank correlation between the two assay formats (ρ = 0.91). See Supporting Information, Table S1, for assay details

- Mirguet O.; Gosmini R.; Toum J.; Clement C. A.; Barnathan M.; Brusq J.-M.; Mordaunt J. E.; Grimes R. M.; Crowe M.; Pineau O.; Ajakane M.; Daugan A.; Jeffrey P.; Cutler L.; Haynes A. C.; Smithers N. N.; Chung C.-w.; Bamborough P.; Uings I. J.; Lewis A.; Witherington J.; Parr N.; Prinjha R. K.; Nicodeme E. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 7501–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasitpan N.; Patel J. N.; Decroos P. Z.; Stockwell B. L.; Manavalan P.; Kar L.; Johnson M. E.; Currie B. L. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1992, 29, 335–41. [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda T.; Nagino C.; Oguri M.; Itô S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 2459–62. [Google Scholar]

- French C. A.; Ramirez C. L.; Kolmakova J.; Hickman T. T.; Cameron M. J.; Thyne M. E.; Kutok J. L.; Toretsky J. A.; Tadavarthy A. K.; Kees U. R.; Fletcher J. A.; Aster J. C. Oncogene 2008, 27, 2237–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart H. J. S.; Horne G. A.; Bastow S.; Chevassut T. J. T. Cancer Med. 2013, 2, 826–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmore J. E.; Issa G. C.; Lemieux M. E.; Rahl P. B.; Shi J.; Jacobs H. M.; Kastritis E.; Gilpatrick T.; Paranal R. M.; Qi J.; Chesi M.; Schinzel A. C.; McKeown M. R.; Heffernan T. P.; Vakoc C. R.; Bergsagel P. L.; Ghobrial I. M.; Richardson P. G.; Young R. A.; Hahn W. C.; Anderson K. C.; Kung A. L.; Bradner J. E.; Mitsiades C. S. Cell 2011, 146, 904–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In order to minimize the possibility of interference from BRD4 inhibition, it is recommended that compound 58 is used at relatively low concentrations in cellular studies, i.e., ≤2 μM, which are sufficient to inhibit p53 effects.

- Lamoureux F.; Baud’huin M.; Rodriguez Calleja L.; Jacques C.; Berreur M.; Rédini F.; Lecanda F.; Bradner J. E.; Heymann D.; Ory B. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broader selectivity profiling was done in the CEREP BioPrint Full Panel (www.cerep.fr).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.