Abstract

New phospholipid analogues incorporating sn-2-peptide substituents have been prepared to probe the fundamental structural requirements for phospholipase A2 catalyzed hydrolysis of PLA2-directed synthetic substrates. Two structurally different antiviral oligopeptides with C-terminal glycine were introduced separately at the sn-2-carboxylic ester position of phospholipids to assess the role of the α-methylene group adjacent to the ester carbonyl in allowing hydrolytic cleavage by the enzyme. The oligopeptide-carrying phospholipid derivatives were readily incorporated into mixed micelles consisting of natural phospholipid (dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine, DPPC) and Triton X-100 as surfactant. Hydrolytic cleavage of the synthetic peptidophospholipids by the phospholipase A2 occurred slower, but within the same order of magnitude as the natural substrate alone. The results provide useful information toward better understanding the mechanism of action of the enzyme, and to improve the design and synthesis of phospholipid prodrugs targeted at secretory PLA2 enzymes.

Keywords: Phospholipid synthesis, antiviral prodrugs, phospholipase A2 catalysis, lipid-prodrug design

1. Introduction

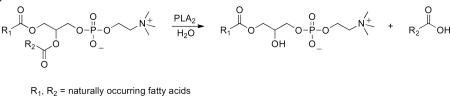

Phospholipases A2 (PLA2s) comprise a superfamily of intracellular and secreted enzymes that catalyze the hydrolysis of the sn-2-ester bond of glycerophospholipids to yield fatty acids such as arachidonic acid and lysophospholipids (Dennis et al., 2011, Eq. (1))

|

(1) |

The products are precursors of signaling molecules with a wide range of biological functions (Murakami and Lambeau, 2013). Along these lines arachidonic acid is converted to eicosanoids that have been shown to be involved in immune response, inflammation, pain perception and sleep regulation (Funk, 2001; Murakami et al., 2011a), while lysophospholipids are precursors of lipid mediators such as lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and platelet activating factor (PAF). Specifically, LPA is involved in cell proliferation, survival and migration (Rivera and Chun, 2008; Zhao and Natarajan, 2009), while PAF is involved in inflammatory processes (Prescott et al., 2000).

Secretory phospholipases A2 (sPLA2s) occur widely in nature (Murakami et al.; 2011b). The members of the sPLA2 family were first isolated from insects and snake venoms, and subsequently they were found in plants, bacteria, fungi, viruses and mammals as well. To date more than 30 isozymes have been identified in mammals, and they have been classified based on their structures, catalytic mechanisms, localization, and evolutionary relationships (Schaloske and Dennis, 2006). The mammalian PLA2 family includes 10 catalytically active isoforms (Lambeau and Gelb, 2008). Secretory PLA2s isolated from a variety of sources share a series of common structural features. They are low molecular weight (14-18 kDa) secreted proteins, with a compact structure stabilized by six conserved disulfide bonds and two additional disulfides that are unique to each member (Dennis et al., 2011). Studies focusing on their mechanism of action have shown that an active site histidine and a highly conserved neighboring aspartate form a catalytic dyad involved in the reaction, requiring Ca2+ for activation (Murakami, 2011b).

Mammalian sPLA2s have been implicated in a variety of physiological and pathophysiological processes including lipid digestion, cell-proliferation, neurosecretion, antibacterial defense, cancer, tissue injury, and atherosclerosis (Murakami, and Lambeau, 2013). Furthermore, it has become apparent that individual secretory phospholipase A2 enzymes play important and diverse roles in biological events by acting through multiple mechanisms: 1) involving production of lipid mediators, and 2) executing their own unique action on their specific extracellular targets in lipid mediator-independent processes (Murakami, 2011b). In this context sPLA2s can also act on non-cellular phospholipids, such as those in microvesicles, lipoproteins, microbial membranes and nutrient phospholipids.

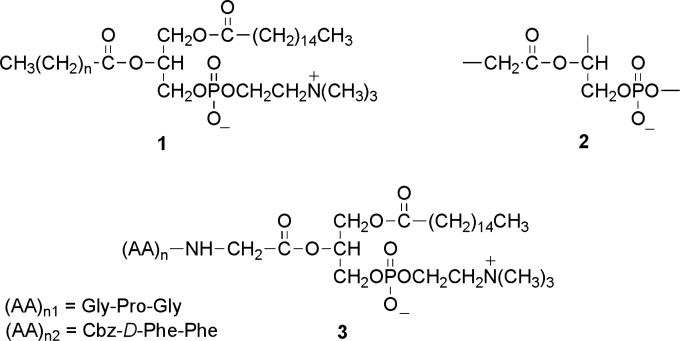

Secretory PLA2s are present extensively in a number of mammalian tissues including pancreas, kidney, and cancer (Arouri et al., 2013). In addition, it has been found that sPLA2 enzymes, particularly subtype IIA, are overexpressed in several cancer types, specifically in prostate, pancreas, breast, and colon cancers (Yamashita et al., 1994), and that they may also be associated with tumorigenesis and tumor metastasis (Tribler et al., 2007, Scott, et al., 2010). Thus, with the recognition that phospholipase A2 activity has been demonstrated in a number of pathological conditions, the idea of designing sPLA2-targeted prodrugs seemed a promising approach to improve the pharmacodynamic properties of tissue-directed drugs (Arouri et al., 2013). The concept was originally based upon replacement of the sn-2-ester group of the natural phospholipid 1, (Figure 1), by an ester group carrying the pharmacophore, directed at the tissue specific sPLA2 isozyme, with the objective that hydrolysis by the enzyme will release the drug. Along these lines a number of sPLA2-targeted prodrugs have been prepared, with the main emphasis on incorporation of pharmacophores with anticancer activities (Andresen et al., 2005, Arouri et al., 2013). One of the recently developed methods of delivery involved the use of phospholipid prodrugs capable of liposome formation, that were pre-mixed with natural phospholipids to provide enhanced formulation stability and performance (Arouri and Mouritsen, 2012), This strategy has been developed as an improved alternative to conventional liposome delivery that circumvents issues of limited efficiency of drug loading, and premature and uncontrolled drug release. However, a significant percentage of these PLA2-targeted prodrugs turned out to be “PLA2 resistant”, (i.e., failed to undergo hydrolysis by the enzyme, Arouri, et al. 2013).

Fig. 1.

Design of the phospholipase A2-directed peptidophospholipids: the naturally occurring phosphatidylcholine 1; the proposed minimum structural requirement for PLA2 catalysis 2, and the designed phosphatidylcholine conjugates carrying oligopeptides 3.

In comparing the structures of the “PLA2-labile” vs. “PLA2-resistant” variants of the prodrugs, it becomes apparent, that in the course of designing the compounds rather limited attention was directed towards one key substrate requirement for efficient PLA2 hydrolysis, i.e., the need for the presence of an α-methylene group adjacent to the sn-2-ester carbonyl of the substrate (Bonsen, et al., 1972). Specifically, among the PLA2 resistant series, the anticancer prodrug derived from ATRA (all-trans-retinoic acid; Christensen, et al., 2010) has a carbon-carbon double bond, and the one targeting RAR (retinoic acid receptor; Pedersen, et al., 2010) carries an aromatic ester group at the sn-2-position. The phospholipid derivative of the NSAID ibuprofen (Kurz and Scriba, 2000) carries a methyl group in place of one of the α-methylene hydrogens, and the acyl chain of valproic acid (an anticonvulsant; Kurz and Scriba, 2000, Dahan et al., 2008) has a branching propyl group at the α-position adjacent to the sn-2-ester carbonyl. Indeed, due to the structural differences between these prodrugs and the requirements for PLA2 catalysis none of these compounds was hydrolyzed by the enzyme.

In this communication we set out to test the working hypothesis that sPLA2 enzymes can hydrolyze phospholipid-based prodrugs equipped with an intact α-methylene group at the sn-2-ester function. Based on the minimum structural requirements for PLA2 catalysis 2 (Figure 1), we have designed two structurally modified phosphatidylcholine analogues 3 incorporating antiviral oligopeptides (Callebaut, et al., Epand et al., 1993, Epand, 2003) at the scissile sn-2-position of the substrate. Replacement of the naturally occurring fatty acyl chain with a membrane fusion inhibitory peptidyl group appeared to yield promising new prodrug candidates to test the feasibility of the release of their pharmacophores by a secretory PLA2 enzyme.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Syntheses

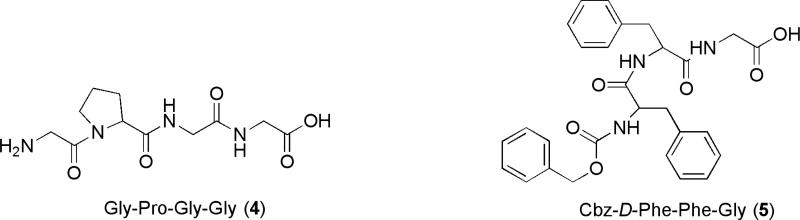

For construction of the PLA2-directed prodrugs we selected peptides 4 and 5, shown in Figure 2, as two antiviral peptides to prepare the target peptidophospholipids.

Fig. 2.

The structures of the selected antiviral peptides 4 and 5.

Specifically, compound 4 is an inhibitor of dipeptidyl peptidase IV, and it has been shown to inhibit entry of HIV-1 and HIV-2 into T limphoblastoid and monocytoid cell lines (Callebaut, et al., 1993), while compound 5 is an antiviral peptide blocking viral infection by inhibiting membrane fusion, a required step in viral entry to the cell (Epand, 2003). While the structures of the two peptides are quite different, what they have in common is the α-methylene group adjacent to the C-terminal carboxyl group, that when incorporated into the phospholipid skeleton at the sn-2-position, makes them suitable to test the working hypothesis regarding the role of the methylene group in the hydrolytic cleavage of PLA2-targeted prodrugs.

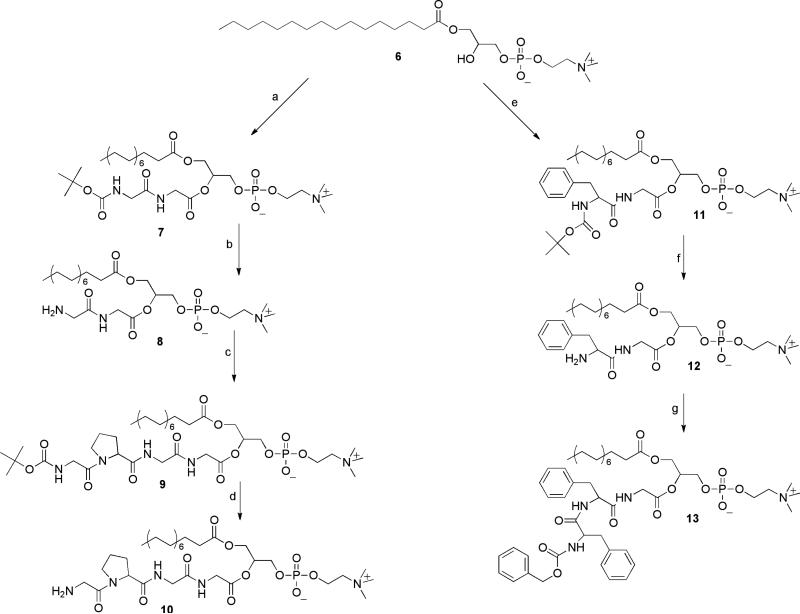

Our strategy for the synthesis of the target prodrugs relied on introducing the peptidyl ester group at the sn-2-position in a stepwise chain-extension sequence, shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) BOC-gly-gly/DCC/DMAP, CHCl3 25°C 4 h; (b) (i) 4.0 M HCl/dioxane, 40 min; (ii) Et3N; (c) BOC-gly-pro-p-nitrophenyl ester /DMAP, CHCl3, rt, 36 h; (d) 4.0 M HCl/dioxane, 30 min; (e) BOC-phe-gly/DCC/DMAP, CHCl , 25°C, 3 h; (f) 4.0 M HCl/dioxane, 2.5 h; (g) N-Cbz-D-phe-p-nitrophenyl ester/DMAP, CHCl3, rt 72 h.

In the first step of the sequence palmitoyl lysophosphatidylcholine 6 was acylated at the sn-2-hydroxyl group with the respective BOC-protected dipeptides using dicyclohexyl carbodiimide (DCC) with 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) as catalyst. In order to achieve efficient and migration-free acylation, we employed the conditions that we have developed for acylation of lysophospholipids (Rosseto and Hajdu, 2005): 1) increasing the glass-surface of the reaction vessel, where the reaction is believed to take place, by addition of glass-beads, while using sonication rather than stirring the reaction mixture, and 2) keeping the temperature below 25°C to prevent intramolecular acyl migration. Under these conditions the reactions reached completion in 3-4 h. The products 7, and 11, were readily isolated and purified on silica gel chromatography eluted with a stepwise gradient of CHCl3-MeOH, followed by CHCl3-MeOH-H2O (65:25:4). We found that using the acid-labile BOC protection of the amino group produced the sn-2-substituted phospholipids in substantially higher yield (90-96%) than the method employing the respective FMOC-derivatives (i.e., 11’ was obtained in 58% yield). Subsequent acid catalyzed cleavage of the tert.butoxycarbonyl group in anhydrous dioxane, followed by freeze-drying of the product solution was carried out in close to quantitative yield.

Chain-extension of the dipeptidyl phospholipid derivatives was carried out using the active ester method. Specifically, the p-nitrophenyl ester of BOC-glycylproline was allowed to react with phospholipid conjugate 8 in chloroform, in the presence of DMAP as catalyst, producing compound 9 in 96% yield. Next, acid catalyzed removal of the BOC protecting group yielded the amine hydrochloride of the peptidophospholipid prodrug 10 (96%). Similarly, the sn-2-phenylalanylglycyl chain of compound 12 was extended in a reaction with p-nitrophenyl Cbz-D-phenylalanine in chloroform, catalyzed by DMAP, to afford the corresponding target prodrug 13 in 81% isolated yield.

2.2 Enzymatic hydrolysis

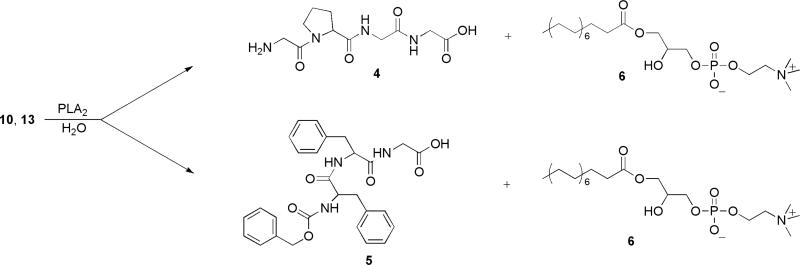

Catalytic hydrolysis of the antiviral phospholipid prodrugs 10 and 13 was carried out with bee-venom phospholipase A2, a widely used, readily available representative of secreted PLA2 enzymes (Arouri and Mouritsen, 2012, Arouri et al., 2013, Valentin et al., 2000) in an assay system containing Triton X-100-phospholipid mixed micelles (Roodsari, et al., 1999) in the presence of the catalytically essential Ca2+ ions. Specifically, the phospholipid component of the micelles included a combination of the antiviral phospholipid prodrugs mixed with the natural phospholipid dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine (DPPC) in molar ratios of 1-to-4, and 1-to-3 respectively, using Triton X-100 as the surfactant. Both synthetic phospholipid analogues were completely hydrolyzed by the enzyme yielding lysophatidylcholine 6, and the antiviral peptides 4 and 5. The products were readily identified by thin layer chromatography. The disappearance of the synthetic substrates occurred slower, but within the same order of magnitude as the PLA2 catalyzed hydrolysis of diplamitoyl phosphatidylcholine (DPPC) in the mixed micelles in the absence of the synthetic peptidophospholipids (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Catalytic hydrolysis of the peptidophospholipids by bee-venom phospholipase A2.

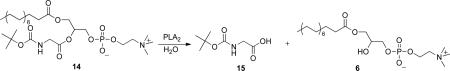

Finally, we tested the prediction of the idea presented earlier as our working hypothesis, focusing on the need for the α-methylene group adjacent to the sn-2-ester function of the substrate to achieve PLA2 catalyzed hydrolysis, by following the PLA2 catalyzed hydrolysis of the aminoacyl analogue 14 carrying BOC-protected glycyl ester at the sn-2-position of the substrate 14. (Eq.2)

|

(2) |

Specifically, we found that compound 14 was readily hydrolyzed by bee-venom PLA2 to yield the BOC-protected glycine 15 and lysophosphatidylcholine 6, under similar assay conditions as those used for the enzymatic hydrolysis of the antiviral peptidophospholipids. Preliminary studies, using mixed micellar substrates composed of compound 14 and palmitoyl phosphatidylcholine in 1-to-1 molar ratio with Triton X-100, indicate that hydrolysis of the synthetic analogue 14 occurred slower, by a factor of two, compared to the rate of PLA2 catalyzed hydrolysis of mixed micelles containing dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine and Triton X-100, in absence of the synthetic compound 14.

3. Conclusions

In addition to the synthesis of a series of sPLA2 targeted antiviral prodrugs the significance of the work here presented is in its contribution to advance the design principles of secretory phospholipase A2 directed substrates, including the preparation of phospholipid prodrugs. The principle that emerged from the work is the prediction that successful design of PLA2 directed prodrugs should include an α-methylene group at the sn-2-ester carbonyl to achieve efficient catalytic hydrolysis by the enzyme. The results also explain why some of the previously prepared phospholipid prodrugs turned out to be “PLA2-resistant”, and opens the way to design new “PLA2-labile” analogues. For example, oligopeptides with aspartic and glutamic acid side-chains that carry the required methylene groups are likely candidates to form PLA2-cleavable sn-2-ester linkages as well, to incorporate new peptide-based pharmacophores built on a phospholipid scaffold.

The principle, however, does not limit the scope of the design and synthesis of successful PLA2-directed prodrugs, by excluding drugs that lack the critical α-methylene group next to the carboxylic function, to attach the pharmacophore at the sn-2-position. Specifically, in that case, a suitable short-chain “spacer” equipped with a methylene bridged carboxylate might be used to link the drug molecule to the phospholipid skeleton (Pedersen, et al., 2010, Rosseto and Hajdu, 2010, Arouri and Mouritsen, 2012). The use of such “linkers,” can effectively target secretory PLA2 enzymes, that will release the drug in the form of the respective conjugated prodrug.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. 1-Palmitoyl-2- (BOC-gly-gly)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (7)

To a suspension of 1-palmitoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (0.5002 g, 1 mmol) in 25 mL of CHCl3 was added BOC-gly-gly (0.7012 g, 3 mmol), followed by DCC (0.6189 g, 3 mmol), DMAP (0.3665 g, 3 mmol) and 1g of glass beads. The reaction was sonicated for 4 h at 25 °C. The mixture was then filtered to remove DCC-urea and glass beads, the solvent collected was evaporated under reduced pressure to one third of its volume and loaded on a silica gel column, eluted with a stepwise gradient of CHCl3/MeOH (5:1 and 5:2) to remove DMAP and the impurities, followed by CHCl3/MeOH/H2O (65:25:4). The fractions corresponding to the product were combined, evaporated, re-dissolved in benzene and freeze-dried to give a white solid 7 (0.6702 g, 0.94 mmol, 94.4%). IR (Nujol): 3300 br m , 1744 vs, 1709 s, 1686 vs, 1248 m cm−1. 1H- NMR (CDCl3, 200 MHz) δ 0.87 (br t, 3H), 1.24 (br s, 24H), 1.41 (s, 9H), 1.56 (m, 2H), 2.29 (t, 2H, J= 7 Hz), 3.31 (br s, 9H), 3.37-3.83 (m, 4H), 4.01 (m, 4H), 4.22-4.26 (m, 4H), 4.57 (m, 1H), 5.22 (m, 1H), 5.73 (m, 1H). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 14.09, 22.66, 24.78, 27.93, 28.38, 29.16, 29.33, 29.52, 29.68, 31.89, 33.93, 41.17, 43.65, 54.18, 59.47, 62.22, 63.93, 66.01, 71.84, 79.49, 156.23, 169.80, 170.51, 173.56. Rf (CHCl3/MeOH/H2O 65:25:4) 0.44. Anal. Cald for C33H64N3O11P•2.5H2O: C, 52.50; H, 9.21; N, 5.57; Found: C, 52.57; H, 8.88; N, 5.58. HRMS MH+ C33H64N3O11PH Cald: 710.4351, Found: 710.4320. [δ]D +6.03 (c 0.96, CHCl3/MeOH 4:1).

4.2. 1-Palmitoyl-2-(BOC-N-gly-pro-gly-gly)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (9)

To a solution of 7 (0.3012 g, 0.42 mmol) in 20 mL of 1,4-dioxane was added 4 M HCl in dioxane solution dropwise at room temperature. After 40 min stirring the mixture became cloudy and a pale yellow precipitate formed, while 7 completely disappeared as observed by TLC (CHCl3/MeOH/H2O, 65:25:4 / Rf 0.44). The precipitate was separated from solution and was freeze-dried from a suspension of 30 mL of benzene. The pale yellow product obtained was washed with CHCl3, yielding a white solid (8). 1H NMR (CD3OD, 200 MHz) δ 0.85 (br t, 3H), 1.25 (br s, 24H), 1.55 (m, 4H), 2.32 (br t, 2H), 3.36 (br s, 9H), 3.40-4.55 (br m), 5.35 (m, 1H). To this white precipitate dispersed in 15 mL CHCl3 was added triethylamine until the pH of solution reached 8. When pH 8 was reached, the mixture became clear. To this solution was added BOC-gly-pro-p-nitrophenyl ester (0.2532 g, 0.64 mmol) followed by DMAP (97 mg, 0.8 mmol). After 36 h stirring at room temperature, to the mixture was added of Dowex-H+ (10 mL) and it was stirred for an additional 15 min. The suspension was then filtered and the resin was washed with 30 mL CHCl3/MeOH (1:1). The solvents were collected, evaporated under reduced pressure to one third of the volume and loaded on silica gel column, eluted first with CHCl3/MeOH (3:1) followed by CHCl3/MeOH/H2O (65:25:4). The fractions corresponding to the product were combined, evaporated, re-dissolved in benzene and freeze-dried to give a white solid 9 (0.3472 g, 0.4 mmol, 95.7%). IR (Nujol): 3298 br m, 1743 br s, 1655 vs, 1534 w, 1245 m cm−1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 200 MHz) δ 0.85 (t, 3H, J= 6.7 Hz), 1.23 (br s, 29H), 1.40 (s, 9H), 1.51 (m, 2H), 2.09 (m, 2H), 2.28 (t, 2H, 6.7 Hz), 3.26 (br s, 9H), 3.65 (m, 3H), 3.82-4.10 (m, 6H), 4.25 (m, 3H), 4.40-4.60 (m, 3H), 5.20 (m, 1H), 5.80 (m, 1H), 8.25 (m, 1H). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 14.05, 22.61, 24.74, 28.34, 29.14, 29.29, 29.50, 29.64, 31.84, 33.89, 42.70, 46.59, 54.10, 59.49, 60.78, 62.18, 63.96, 65.99, 71.75, 79.47, 156.05, 168.76, 169.64, 170.57, 172.60, 173.49. Rf (CHCl3/MeOH/H2O 65:25:4) 0.41. Anal. Cald for C40H74N5O13P•2.5H2O C, 52.85; H, 8.76; N, 7.70; Found: C, 53.04; H, 8.41; N, 7.74. HRMS MH+ C40H74N5O13PH Calcd: 864.5094, Found: 864.5094. [δ]D25 –12.06 (c 0.95, CHCl3/MeOH 4:1).

4.3. 1-Palmitoyl-2-(gly-pro-gly-gly)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine hydrochloride (10)

Compound 10 was obtained from the analytical pure 7 by acid catalyzed deprotection. To a solution of 9 (0.28 g, 0.28 mmol) in 15 mL 1,4-dioxane was added dropwise a solution of 4 M HCl in 1,4-dioxane (3mL) at room temperature. After 30 min stirring the mixture became cloudy and an oily precipitate formed. To the precipitate was added 20 mL benzene followed by freeze-drying. The freeze-dried product was washed with chloroform, and then dried in vacuum to give8 as a white solid (215 mg, 0.26 mmol, 96%). The 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 200 MHz) was identical to the spectrum of 7, except for the absence of the signal of the protons at δ 1.40 (s, 9H) assigned to the removed tBOC protecting group.

4.4. 1-Palmitoyl-2-(BOC-phe-gly)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (11)

To a suspension of 6 (0.5002 g, 1 mmol) in 25 mL of CHCl3 was added BOC-phe-gly-OH (1.0021g, 3 mmol), followed by DCC (0.6408 g, 3 mmol), DMAP (0.3798 g, 3 mmol), and 1g of glass beads. The reaction was sonicated for 3 h at 25 °C. After 3 h, the sonication was stopped and to the mixture was added 10 mL of Dowex-H+ and the suspension was stirred for 10 min. The mixture was then filtered and the resin was washed with 40 mL of CHCl3/MeOH (1:1). The solvents collected were evaporated under reduced pressure to one third of the volume and then directly loaded on a silica gel column for chromatography, using CHCl3/ MeOH (7:3) eluent, followed by CHCl3/MeOH/H2O (65:25:4). The fractions corresponding to the product were combined, evaporated, re-dissolved in benzene and freeze-dried to give an off-white pale-yellow solid 11 (0.7194 g, 0.90 mmol, 90%). IR (Nujol): 3188 br w, 1742 vs, 1680 br vs, 1250 m cm−1. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 200 MHz) δ 0.84 (br t, 3H), 1.25 (br s, 24H), 1.31 (br s, 9H), 1.54 (m, 2H), 2.25 (t, 2H, J= 6.7 Hz), 2.78 (m, 2H), 3.27 (br s, 9H), 3.76 (m, 2H), 4.14 (m, 3H), 4.21-4.71 (m, 4H), 4.76 (m, 2H), 5.25 (m, 1H), 5.47 (m, 1H), 7.22 (br s, 5H), 8.62 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 14.08, 22.64, 24.74, 28.25, 29.12, 29.28, 29.32, 29.50, 29.62, 29.67, 31.88, 33.89, 39.07, 41.21, 54.22, 55.06, 59.44, 62.32, 63.95, 66.17, 71.79, 79.43, 126.60, 128.29, 129.48, 136.95, 155.33, 169.65, 172.30, 173.52. Rf (CHCl3/MeOH/H2O 65:25:4) 0.40. Anal. Cald for C40H70N3O11P•0.5H2O C, 59.39; H, 8.85; N, 5.19; Found: C, 59.07; H, 8.80; N, 5.33. FAB-MS MH+ C40H70N3O11PH Calcd: 800.4821, Found: 800.4827. [δ]D25 +1.44 (c 1.04, CHCl3/MeOH 4:1)

4.5. 1-Palmitoyl-2-(CBZ-D-phe-phe-gly)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (13)

To a solution of 9 (0.3850 g, 0.48 mmol) in 20 mL 1,4-dioxane was added 4 M HCl in 1,4-dioxane (7 mL) dropwise at room temperature. The reaction mixture was stirred for 2.5 h, followed by the addition of 30 mL benzene and it was freeze-dried to give the deprotected amine 10 as a white solid. The 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 200 MHz) spectrum of the compound 12 showed the same pattern as the spectrum of compound 11, except for the absence of the signal assigned to the protons at δ 1.40 (s, 9H) of the removed BOC protecting group. To the white precipitate of12 dissolved in 20 mL of CHCl3 was added DMAP (0.2987 g, 2.5mmol) until pH of solution reached 8, followed by the active ester p-nitrophenyl N-Cbz-D-phenylalanine (0.2652g, 0.63 mmol) at room temperature. After 24 h more active ester (0.1802 g, 0.43 mmol) was added. After 48 h stirring at room temperature, to the mixture was added 15 mL Dowex-H+ and it was stirred for 10 min. The suspension was filtered and the resin was washed with 30 mL CHCl3/MeOH (1:1). The solvents collected were evaporated under reduced pressure to one third of the volume and loaded on a silica gel column, eluted first with CHCl3/MeOH (3:1), followed by CHCl3/MeOH/H2O (65:25:4). The fractions corresponding to the product were combined, evaporated, re-dissolved in benzene and freeze-dried to give a white solid 13 (0.3815 g, 0.39 mmol, 81.3%). IR (Nujol): 3292 w, 1728 s, 1693 m, 1643 vs, 1540 m, 1301 w cm−1. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 200 MHz) δ 0.85 (br t, 3H), 1.25 (br s, 24H), 1.52 (m, 2H), 2.23 (t, 2H, J= 6.7 Hz), 2.73 (m, 2H), 3.05 (m, 2H), 3.17 (br s, 9H), 3.71 (m, 2H), 4.05-4.20 (m, 4H), 4.35 (m, 2H), 4.62 (m, 2H), 4.81-5.02 (m, 4H), 5.25 (m, 1H), 6.03 (m, 1H), 6.90-7.26 (m, 15H), 8.01 (m, 1H), 8.32 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 14.10, 22.65, 24.74, 29.12, 29.33, 29.51, 29.63, 29.68, 31.89, 33.86, 37.69, 38.43, 41.32, 54.21, 54.70, 55.89, 59.85, 62.08, 64.43, 65.93, 66.58, 71.52, 126.66, 126.83, 127.65, 128.02, 128.33, 128.48, 129.33, 129.46, 136.47, 137.05, 155.97, 169.54, 171.60, 172.27, 173.55. Rf (CHCl3/MeOH/H2O 65:25:4) 0.55. Anal. Cald for C52H77N4O12P•4H2O C, 59.30; H, 8.13; N, 5.32; Found: C, 59.75; H, 7.78; N, 5.51. FAB-MS MH+ C52H77N4O12PH Calcd: 981.5348, Found: 981.5375. [δ]D25-6.57 (c 0.97, CHCl3/MeOH 4:1).

4.6. 1-Palmitoyl-2-(FMOC-phe-gly)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (11’)

To a suspension of 1-palmitoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine 6 (0.5002 g, 1 mmol) in 25 mL of CHCl3 were added FMOC-phe-gly-OH (0.5393 g, 1.2 mmol), DCC (0.2498 g, 1.2 mmol), DMAP (0.1479 g, 1.2 mmol) and 1g of glass beads. The reaction was sonicated for 48 h at 25 °C, the mixture was then filtered to remove DCC-urea and glass beads. The solvent was evaporated to one third of the volume and then loaded on a silica gel column for chromatography. A stepwise gradient of CHCl3/MeOH (5:1 and 5:2) was applied to elute DMAP and some impurities, followed by CHCl3/MeOH/H2O (65:25:4). The fractions corresponding to the product were combined, evaporated, re-dissolved in benzene and freeze-dried to give 11’ as a white solid (0.5352 g, 0.58 mmol, 58%). IR (Nujol): 3297 br m, 1728 vs, 1693 s, 1654 vs, 1536 m, 1252 w cm−1. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 200 MHz) δ 0.85 (br t, 3H), 1.25 (br s, 24H), 1.50 (m, 2H), 2.20 (t, 2H, J=6.7 Hz), 2.95 (m, 2H), 3.17 (br s, 9H), 3.67 (br s, 2H), 3.95-4.30 (br m, 10H), 4.44 (m, 2H), 5.36 (m, 1H), 6.15 (m, 1H), 7.21-7.47 (m, 11H), 7.72 (d, 2H, J= 7.4 Hz), 8.66 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 14.28, 22.85, 24.92, 29.31, 29.52, 29.71, 29.83, 29.87, 32.08, 34.04, 38.94, 41.47, 47.13, 54.34, 55.90, 59.63, 62.44, 64.18, 66.28, 67.07, 71.96, 120.08, 125.27, 125.47, 126.94, 127.26, 127.86, 128.57, 129.63, 137.05, 141.30, 143.90, 156.17, 169.83, 172.39, 173.72. Rf (CHCl3/MeOH/H2O 65:25:4) 0.48. Anal. Cald for C50H72N3O11P•2.5H2O C, 62.09; H, 8.02; N, 4.34; Found: C, 62.33; H, 8.03; N, 4.04. FAB-MS MH+ C50H72N3O11PH Calcd: 922.4977, Found: 922.4981. [δ]D25°C –6.73 (c 0.98, CHCl3/MeOH 4:1).

4.7. 1-palmitoyl-2-(N-BOC-glycyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (14)

To a suspension of 1-palmitoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine 6 (0.3704 g, 0.7 mmol) in 25 mL of CHCl3 was added N-BOC-gly (0.5305 g, 3 mmol), followed by DCC (0.6204 g, 3 mmol), DMAP (0.3704 g, 3 mmol) and 1g of glass beads. The reaction was sonicated for 1 h at 25 °C. Next, to the mixture were added 8 mL of Dowex-H+ and stirred for 10 min. The resin was filtered and washed with 30 mL of CHCl3:MeOH (1:1). The combined solution was evaporated under reduced pressure to one third of volume and then was promoted the chromatographic purification on silica gel using as eluent. and then was loaded on a silica gel column, eluted first with CHCl3/MeOH (7:3), folloed by CHCl3/MeOH/H2O (65:25:4). The fractions corresponding to the product were combined, evaporated, re-dissolved in benzene and freeze-dried to give a white solid 14 (0.4325 g, 0.66 mmol, 94.5%). IR (Nujol): 3364 br m, 1746 vs, 1714 vs, 1253 m, 1168 m cm−1. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 200 MHz) δ 0.85 (br t, 3H), 1.23 (br s, 24H), 1.40 (s, 9H), 1.52 (m, 2H), 2.26 (t, 2H, J= 6.7 Hz), 3.26 (br s, 9H), 3.75-4.01 (m, 6H), 4.10-4.18 (m, 2H), 4.25 (m, 2H), 5.22 (m, 1H), 6.21 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 50 MHz) δ 14.01, 22.58, 24.71, 28.33, 29.08, 29.22, 29.25, 29.44, 29.56, 29.60, 31.82, 33.89, 42.31, 54.16, 59.36, 62.43, 63.62, 65.98, 71.50, 79.39, 156.04, 170.36, 173.47. Rf (CHCl3/MeOH/H2O 65:25:4) 0.38. Anal. Cald for C31H61N2O10P•H2O C, 55.50; H, 9.47; N, 4.18, Found: C, 55.50; H, 9.49; N, 4.04. FAB-MS MH+ C31H61N2O10PH Calcd: 653.4137, Found: 653.4165. [δ]D25°C +8.80 (c 1.00, CHCl3/MeOH 4:1).

4.8. Enzymatic hydrolysis of the phospholipids

4.8.1

In a typical experiment prodrug 10 (4.7 mg, 5.8 μmol) was added to a mixture containing dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine (DPPC, 17.9 mg, 23.4 μmol), in 4.1 mL Tris buffer (0.05 M, pH 8.50), with 0.1 mL Triton X-100 and CaCl2 (7.2 mg, 0.049 mmol) The mixture was vortexed, for 5 min, followed by incubation of the resulting dispersion at 40°C for 10 min in a constant-temperature water-bath. To the optically clear dispersion that resulted was added bee-venom phospholipase A2 (40 μg in 200 μL buffer) to initiate the reaction. The reaction mixture was kept at 40°C, and formation of the products was analyzed by thin layer chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH/H2O, 65:25:4). The compounds were visualized by iodine adsorption, molybdic acid spray and ninhydrin spray. TLC analysis showed complete hydrolysis of the phospholipids (DPPC and the synthetic phospholipid prodrug 10) by PLA2 within 90 min, leading to the formation of lysophosphatidylcholine 6, and the oligopeptide 4. PLA2 catalyzed hydrolysis of DPPC under the same conditions in absence of compound 10 was completed in 10 min.

4.8.2

In a somewhat similar experimental setup, prodrug 13 (3.4 mg, 0.5 μmol) was added to a mixture containing DPPC (15 mg, 1.5 μmol), in 4.1 mL Tris buffer (0.05 M, pH 8.50), with 0.1 mL Triton X-100 and 50 mM CaCl2. The mixture was vortexed, for 5 min, kept at 40°C for 10 min in a constant-temperature water-bath. To the resulting dispersion was added bee-venom phospholipase A2 (16 μg in 80 μL 0.05 M Tris buffer, pH 8.5) to initiate the reaction. The reaction mixture was kept at 40°C, and formation of the products was analyzed by thin layer chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH/H2O, 65:25:4). The compounds were visualized by UV-absorption, iodine adsorption, and molybdic acid spray. TLC analysis showed complete hydrolysis of the DPPC and the synthetic phospholipid prodrug 13 within 90 min, producing lysophosphatidylcholine 6, and the oligopeptide 5.

4.8.3

The synthetic phospholipid analogue with sn-2-N-BOC-gly 14, was hydrolyzed by bee-venom PLA2 under similar experimental conditions to those used for the catalytic hydrolysis of the peptide substituted analogues. TLC showed that the reaction was completed in 20 min, while the hydrolysis of DPPC in the same assay mixture without the aminoacyl phospholipid 14 was completed in 10 min.

The prodrugs did not change in the absence of the enzyme.

Highlights.

Peptide conjugates of phospholipids have been prepared for the first time.

The synthesis provides access to PLA2-directed prodrugs.

The α-methylene group next to the sn-2-carboxyl is essential for PLA2-catalysis.

New design principles developed for the synthesis of PLA2-targeted substrates.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health, grant 1SC3GM096878 for financial support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andresen TL, Jensen SS, Jorgensen K. Advanced strategies in liposomal cancer therapy; problems and prospects of active and tumor specific drug release. Prog. Lipid Res. 2005;44:68–97. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arouri A, Hansen AH, Rasmussen TE, Mouritsen OG. Lipases, liposomes, and lipid-prodrugs. 2013. Curr. Opin. Coll.Int. Sci. 2013;18:419–431. [Google Scholar]

- Arouri A, Mouritsen OG. Phospholipase-A2-susceptible liposomes of anticancer double lipid-prodrugs Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012;45:408–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonsen PPM, Haas G. H. de, Pieterson WA, Deenen L. L. M. van. Studies on phospholipase A and its zymogen from porcine pancreas IV. The influence of chemical modification of the lecithin structure on substrate properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1972;270:364–382. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(72)90200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callebaut C, Krust B, Jacotot E, Hovanessian AG. Cell activation antigen, CD26, as a cofactor for entry of HIV in CD4+ cells. Science. 1993;262:2045–2050. doi: 10.1126/science.7903479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen MS, Pedersen PJ, Andersen TL, Madsen R, Clausen MH. Isomerization of all-(E)-retinoic acid mediated by carbodiimide activation – Synthesis of ATRA ether lipid conjugates. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010;2010:719–724. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis EA, Cao J, Hsu HY, Magrioti V, Kokotos G. Phospholipase A2 enzymes: physical structure, biological function, disease implication, chemical inhibition, and therapeutic intervention. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:6130–6185. doi: 10.1021/cr200085w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan A, Duvdevani R, Shapiro I, Ellman A, Finkelstein E, Hoffman A. The oral absorption of phospholipid prodrugs: in vivo and in vitro mechanistic investigation of trafficking of a lecithin-valproic acid conjugate following oral administration J. Control Release. 2008;126:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong O, Patel M, Scott KF, Graham GG, Russell PG, Sved P. Oncogenic action of phospholipase A2 in prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 2006;240:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand RM, Epand RF, Richardson CD, Yeagle PL. Structural requirements for the inhibition of membrane fusion by carbobenzoxy-D-Phe-Phe-Gly. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1993;1152:128–134. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(93)90239-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand RM. Fusion peptides and the mechanism of viral fusion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1614:116–121. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka D, Kugiyama K. Novel insights of secretory phospholipase A2 action in cardiology. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2009;19:100–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294:1871–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz M, Scriba GKE. Drug-phospholipid conjugates as potential prodrugs: synthesis, characterization, and degradation by phospholipase A2. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2000;107:143–157. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(00)00167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambeau G, Gelb MH. Biochemistry and physiology of mammalian secreted phospholipase A2. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:495–520. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.062405.154007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Lambeau G. Emerging roles of secreted phospholipase A2 enzymes: An update. Biochimie. 2013;95:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Taketonmi Y, Sato H, Yamamoto K. Secreted phospholipase A2 revisited. J. Biochem. 2011a;150:233–255. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Taketomi Y, Miki Y, Sato H, Hirabayashi T, Yamamoto K. Recent progress in phospholipase A2 research: from cells, to animals, to humans. Prog. Lipid Res. 2011b;50:152–192. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen PJ, Adolph SK, Subramanian AK, Arouri A, Andresen TL, Mouritsen OG, Madsen R, Madsen MW, Peters GH, Clausen MH. Liposomal formulation of retinoids designed for enzyme triggered release. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:3782–3792. doi: 10.1021/jm100190c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott SA, Zimmerman GA, Stafforini DM, McIntire TM. Platelet-activating factor and related lipid mediators. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:419–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera D, Chun J. Biological effect of lysophospholipids. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008;160:25–46. doi: 10.1007/112_0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roodsari FS, Wu D, Pum GS, Hajdu J. A new approach to the stereospecific synthesis of phospholipids. The use of L-glyceric acid for the preparation of diacylglycerols, phosphatidylcholines, and related derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:7727–7737. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseto R, Hajdu J. A rapid and efficient method for migration-free acylation of lysophospholipids: synthesis of phosphatidylcholines with sn-2-chain-terminal reporter groups. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:2941–2944. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseto R, Hajdu J. Synthesis of oligo(ethylene glycol) substituted phosphatidylcholines: Secretory PLA2-targeted precursors of NSAID prodrugs. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2010;163:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaloske RH, Dennis EA. The phospholipase A2 superfamily and its group numbering system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1761:246–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KF, Sajinovic M, Hein J, Nixdorf S, Galettis P, Liauw W. Emerging roles for phospholipase A2 in cancer. Biochimie. 2010;92:601–610. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaug MJ, Longo ML, Faller R. The impact of Texas Red on lipid bilayer. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:8500–8505. doi: 10.1021/jp203738m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribler L, Jensen IT, Jorgensen K, Brunner N, Gelb MH, Nielsen HJ. Increased expression and activity of group IIA and X phospholipase A2 in peritumoral versus central colon carcinoma tissue. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:3179–3185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin E, Ghomashchi F, Gelb M, H., Ladzunski M, Lambeau C. Novel human secreted phospholipase A2 with homology to the group III bee venom enzyme J. Biol Chem. 2000;275:7492–7496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita S, Yamashita J, Ogawa M. Overexpression of group II phospholipase A2 In human breast cancer tissues is closely associated with their malignant potency. Br. J. Cancer. 1994;69:1166–1170. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Natarajan V. Lysophosphatidic acid signaling in airway epithelium: role in airway inflammation and remodeling. Cellular Signaling. 2009;21:367–377. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]