Abstract

Recent studies in both rodents and humans suggest that elevated serum phosphorus, in the context of normal renal function, potentiates or exacerbates pathologies associates with cardiovascular disease, bone metabolism, and cancer. Our recent microarray studies identified the potent stimulation of pro-angiogenic genes such as Forkhead box protein C2 (FOXC2), osteopontin, and Vegfα, among others in response to elevated inorganic phosphate (Pi). Increased angiogenesis and neovascularization are important events in tumor growth and the progression to malignancy and FOXC2 has recently been identified as a potential transcriptional regulator of these processes. In this study we addressed the possibility that a high Pi environment would increase the angiogenic potential of cancer cells through a mechanism requiring FOXC2. Our studies utilized lung and breast cancer cell lines in combination with the human umbilical vascular endothelial cell (HUVEC) vessel formation model to better understand the mechanism(s) by which a high Pi environment might alter cancer progression. Exposure of cancer cells to elevated Pi stimulated expression of FOXC2 and conditioned medium from the Pi-stimulated cancer cells stimulated migration and tube formation in the HUVEC model. Mechanistically, we define the requirement of FOXC2 for Pi-induced OPN expression and secretion from cancer cells as necessary for the angiogenic response. These studies reveal for the first time that cancer cells grown in a high Pi environment promote migration of endothelial cells and tube formation and in so doing identify a novel potential therapeutic target to reduce tumor progression.

Keywords: inorganic phosphate, angiogenesis, migration, FOXC2, osteopontin

INTRODUCTION

There is a growing appreciation that changes in serum phosphorus levels influence age-associated disease progression, as seen in cancer [1–3], bone metabolism [4–8], and cardiovascular function [9–11] even in the context of normal renal function. High serum phosphorus, usually in the form of inorganic phosphate (Pi) has also been suggested to accelerate mammalian aging in mouse models [12,13]. Recent studies in mice have demonstrated that a diet high in Pi increased tumorigenesis in the two-stage skin carcinogenesis model as well as the Kras lung cancer model [1,2]. The mechanisms by which high Pi consumption and serum levels might influence tumor growth remain to be fully elucidated, but likely involve a combination of cell autonomous as well as autocrine, paracrine, and/or endocrine signals [1,14].

A number of events are required for tumor growth leading to malignancy and angiogenesis is considered an important step in this progression [15–17]. Our recent studies, using large scale transcriptomics and proteomics, identified a number of pro-angiogenic genes and proteins upregulated by elevated Pi in pre-osteoblasts cells [14] including, among others, Vegfα, OPN, and FOXC2. FOXC2 is a forkhead box (Fbox) transcription factor that is required for vasculogenesis during development [18] and represents a potential novel target in modulating tumor mediated angiogenesis. Our previous studies also have identified OPN (spp1) as strongly upregulated, at both the RNA and protein levels, in response to elevated Pi [14,19,20]. OPN, a secreted cytokine like factor, is strongly linked to malignant transformation and metastasis [21–23] and has recently been associated with tumor angiogenesis [24].

To date, most studies investigating the cell autonomous effects of Pi on cell behavior have focused on non-transformed mineralizing cell types and therefore the effects of a high Pi environment on cancer cell behavior are relatively unknown. Here we investigated the potential effects of elevated extracellular Pi on cancer cell lines with a focus on angiogenesis and the role of FOXC2 and OPN. Towards this end, we have used conditioned medium (CM) from Pi-treated A549 lung cancer cells and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells in combination with HUVECs to test the hypothesis that a high Pi environment increases the propensity of cancer cells to recruit blood supply. Taken together, our results define elevated Pi as a strong influencing factor in cancer cell driven chemotaxis of endothelial cells and vessel formation and identify FOXC2 and OPN as mechanistically involved.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell culture

A549 and MDA-MB-231 cells were kindly provided by Nancy Colburn (NCI, Frederick, MD). Cells were grown in DMEM (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA), 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. DMEM contains 1mM Pi and added Pi was in the form of NaHPO4 (pH6.8) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Plasmids and siRNA constructs

The human FOXC2 expression plasmid was purchased from Openbiosystems-Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA) and subcloned into PcDNA3.1(+) (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) and sequence verified. The FOXC2 or empty vector control constructs were transfected using Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen). The three Stealth siRNAs (Invitrogen) and a Medium GC Duplex (negative control) were used and were transfected using RNAiMAX (Invitrogen).

Quantitative real time PCR

RNA and qRT-PCR was performed as described previously [14]. Primers were designed by website qPrimerDepot (http://primerdepot.nci.nih.gov/) and purchased from IDT (Coralville, IA). Sequences for 18S (CAGCCACCCGAGATTGAGCA, TAGTAGCGACGGGCGGTGTG); FOXC2 (CTCAACGAGTGCTTCGTCAA, ACATGTTGTAGGAGTCCGGG); OPN (CATCACCTGTGCCATACCAG, AGATGGGTCAGGGTTTAGCC); and VEGFα (CTACCTCCACCATGCCAAGT, AGCTGCGCTGATAGACATCC). All qRT-PCR results were calculated using the ΔΔCT method.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were washed twice with cold 0.9%NaCl and then lysed in M-PER reagent supplemented with Halt Protease & Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Whole cell lysate was separated by electrophoresis on a NuPAGE Bis-Tris Mini Gel (Life Technologies; Grand Island, NY) and electro-transferred to PVDF membrane Hybond-P (GE Health Sciences, Piscataway, NJ). All antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies Inc., (Santa Cruz, CA).

Tube formation Assay

HUVECs were purchased from Life Sciences (Invitrogen) and cultured in Medium 200 with Low Serum Growth Supplement at 37°C and 5% CO2. The concentrated conditioned medium (CM) was generated from cancer cells treated with Pi (or control) for 3 or 6 days (the medium was changed every 2–3 days). The medium was then removed and replaced with serum free-phenol free DMEM plus pen/strep and glutamine (containing 1mM Pi) for 24h. The resulting CM from 3–10cm plates was concentrated using Amicon Ultra filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA), resulting in the concentration of ~15ml to ~300μl. The concentrated CM (5ul) was added to HUVEC cultures (3×104 cells) in 96-well plates and cells were photographed after 6h. Tube formation was quantified by Wimasis GmbH software (Munich, Germany).

Migration Assay

The CM from Pi-treated cells (not concentrated) was harvested as described for Tube Formation Assays. HUVECs were cultured in growth medium on ThinCertTM cell culture inserts-8um pore (Greiner Bio-one; Monroe, NC) and migration to the lower chamber (CM) was measured. For antibody neutralization assays, antibodies to OPN and VEGFα (Santa Cruz) were incubated with CM at room temperature for 1 hour before the CM was used for migration. Recombinant mouse OPN (R&D systems; Minneapolis, MN) or BSA (control) was added to A549 CM (untreated) for 24 hours and migration assay performed.

Luciferase promoter reporter assay

The 2kb mouse OPN promoter reporter luciferase plasmid was constructed by PCR using primers: Forward 5′-TACCTCCCTAATTCGTGTTGA-3′ and Reverse 5′-CCTTGGCTGGTTTCCTCCGAGA-3′ and cloned into PGL3 (Promega). The plasmids were transfected with Lipofectamine LTX kit (Invitrogen) and 48h later the cells were treated with Pi for 24h. Luciferase activity was measured as described previously [14].

ELISA

The concentration of OPN in the condition medium was measured using Quantikine Human Osteopontin ELISA kit purchased from R&D Systems according to manufacturer’s protocol.

RESULTS and DISCUSSION

Elevated Pi increases expression of pro-angiogenic genes in cancer cells

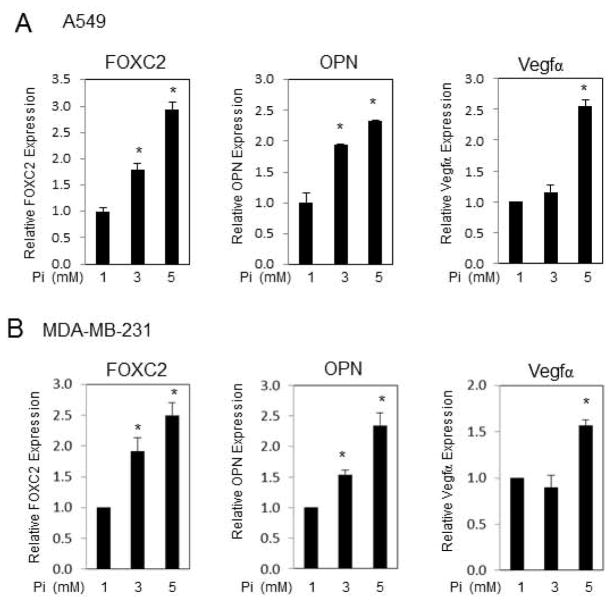

Our previous microarray results suggested that elevated Pi increased expression of key pro-angiogenic genes such as FOXC2, OPN (spp1), and Vegfα in a pre-osteoblast cell line [14]. To determine if elevated Pi induced a similar response in human cancer cells we treated A549 human lung adenocarcinoma and MDA-MB-231 breast adenocarcinoma cells with increasing Pi (1, 3, or 5mM final) for varying times up to 6 days. Results revealed that increasing medium Pi dose dependently increased FOXC2, OPN, and Vegfα gene expression in A549 cells with optimal expression at 6 days and in MDA-MB-231 cells at 3 days (Fig. 1A,B). These times points were therefore used for the respective cell line throughout subsequent studies. The increased expression of these known pro-angiogenic, chemotactic factors suggested that exposure of cancer cells to an environment with increased Pi availability might increase the ability of these cells to attract endothelial cells and/or induce an angiogenic response.

Figure 1. Pi increases FOXC2, OPN, and Vegfα mRNA levels in A549 and MDA-MB-231 cells.

(A) A549 and (B) MDA-MB-231 were cultured in the normal growth medium (10%FBS and 1mM Pi) and Pi added to a final concentration of 1, 3, or 5mM for 6 days (A549) and 3 days (MDA-MB-231). Cells were harvested for total RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR. 18S rRNA was used for normalization. *P<0.05 (Student’s t-test). Results expressed as mean±SD (n=3).

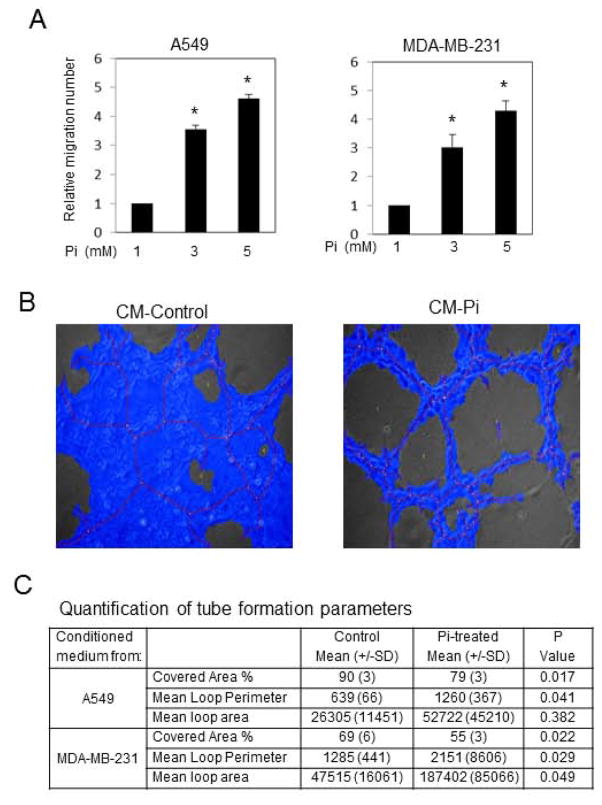

Conditioned medium from cancer cells grown in a high Pi environment stimulates HUVEC migration and tube formation

An important event in angiogenesis and neovascularization is the migration of endothelial cells. To determine if conditioned medium (CM) from Pi-treated cancer cells increased migration of HUVECs we utilized a two chamber porous membrane “Boyden” assay [25]. CM from Pi-treated cells, A549 at 6 days and MDA-MB-231 at 3 days, was used in the lower chamber and the number of HUVEC cells migrating from the upper chamber was counted after 20h. Results revealed a significant dose-dependent increase in migration in response to conditioned medium from A549 and MDA-MB-231 Pi-treated cells (Fig. 2A). To determine the effects of a high Pi environment on cancer cell stimulation of angiogenesis, we used CM in combination with the HUVEC tube formation assay. A549 and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with elevated Pi and the medium was replaced with serum free-phenol free medium for 24h. The conditioned medium (containing 1mM Pi) was collected, concentrated by filter centrifugation, and added to the HUVEC cells in tube forming medium. The resulting cell layers were photographed under light microscopy and analyzed with WIMASIS software in an unbiased manner (Fig. 2B). CM from cancer cell lines grown in elevated Pi (5mM) significantly increased tube formation parameters relative to CM from the same cancer cells grown in 1mM Pi (Fig. 2C). Taken with the results from the migration assay the data suggest that cancer cell lines grown in a high Pi environment secrete factors capable of increasing both endothelial cell migration and tube formation, key events in angiogenesis and neovascularization.

Figure 2. Conditioned medium from Pi-treated cancer cells increases HUVEC migration and tube formation.

A549 and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with Pi (1, 3, or 5mM final) for 6 or 3 days respectively, at which point medium was replaced with serum free-phenol free medium for 24h and collected as conditioned medium (CM). (A) CM was used to determine the effects of HUVEC migration using a two chamber porous membrane “Boyden” assay. Cells in the lower chamber were counted after 20h. *P<0.05 compared with 1mM Pi treatment. N=3–5. (B) Cancer cells were treated with Pi (1 or 5mM final) and the medium was replaced with serum free-phenol free, collected, and concentrated by filter centrifugation and added to a HUVEC tube formation assay. The resulting cells were photographed and results quantified by Wimasis GmbH (Munich, Germany) software (C). *P<0.05 (Student’s t-test). Results expressed as mean±SD (n=3).

FOXC2 is required for Pi-stimulated migration

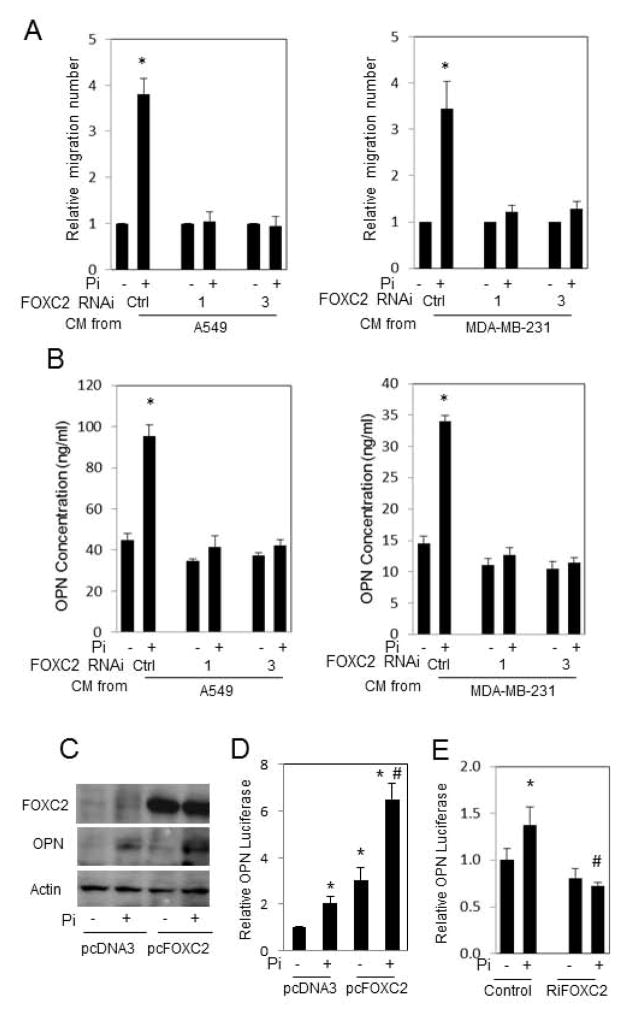

FOXC2 is involved in tumor angiogenesis and is induced by elevated Pi (Fig. 1); therefore, we hypothesized that FOXC2 represents an important mediator of the Pi-induced endothelial cell migration response. To determine if FOXC2 is a required mechanism for Pi-induced HUVEC migration we knocked down FOXC2 using siRNA. Three different siRNAs targeting FOXC2 or scrambled control were transiently transfected into A549 and MDA-MB-231 cells and knockdown of FOXC2 expression was confirmed by qRT-PCR. Knockdown or control cells were treated with Pi or not (control), and the resulting CM was used in the two chamber migration assays. CM from Pi-treated control cells resulted in significantly increased migration; however, CM from FOXC2 knockdown cells resulted in no increase in migration (Fig. 3A). This result supports the idea that FOXC2 is a necessary mediator of the cellular response to elevated Pi resulting in increased chemotaxis of endothelial cells. Emerging data suggest that deregulation of members of the evolutionarily conserved forkhead box (Fox) transcription factor family [26] is associated with cancer [27]. FOXC2 is highly expressed in human breast and colon tumors as well as tumor endothelium in human and mouse melanoma [28], and linked to cancer through increased metastasis and invasion of breast cancer cells [29] with increased epithelial-mesenchymal transition [30]. Our findings support the concept that FOXC2 plays an important role in angiogenesis and vessel formation, and identify extracellular Pi as a novel modulator of FOXC2 in cancer cell types from different tissues, which also suggests a potential broad significance of FOXC2 for tumor induced angiogenesis.

Figure 3. Knockdown of FOXC2 blocks Pi-induced conditioned medium mediated HUVEC migration and Pi-induced OPN expression.

(A) A549 and MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with two different RNAi’s targeting FOXC2 (RNAi-“1” and RNAi-“3”), or siControl (Ctrl) followed by stimulation with Pi or not (1 and 5mM final). Conditioned medium was collected and used in the two-chamber HUVEC migration assay. Results expressed as mean±SD (n=3–5). * P<0.05, compared with 1mM Pi treatment. (B) A549 and MDA-MB-231 were transfected with two different siRNA’s targeting FOXC2 (1 and 3), or siControl (Ctrl) and left untreated (1mM Pi) or treated with 4mM Pi (5mM final) and medium collected and secreted OPN protein levels measured by ELISA. (C) HCT116 cells were transfected by pcDNA3.1 vector or pcDNA3.1-FOXC2 expression plasmid and the cells treated by 4mM of Pi for 2 days (1 and 5mM final). The harvested samples were analyzed by western blotting. (D) HCT116 cells were co-transfected with a 2 kb OPN promoter reporter and either pcDNA3.1 empty vector plasmid or the pcDNA3.1-FOXC2 expression plasmid. The luciferase activities were measured after 24h. Results expressed as mean±SD (n=4). (E) MDA-MB-231 cells were co-transfected with the OPN reporter and RNAi targeting FOXC2 and treated with 4mM Pi as indicated. Luciferase activity was measured after 24 hours. Results expressed as mean±SD (n=3). *P<0.05, compared with control plasmid and no added Pi (1mM Pi); # P<0.05, compared to control plasmid+Pi (5mM).

FOXC2 is required for OPN expression in response to elevated Pi

The above results identify the coordinated regulation of FOXC2 and OPN suggestive of a potential regulatory relationship in response to elevated Pi and the subsequent requirement of this regulation for the elevated Pi-induced increase in HUVEC migration. To test this hypothesis we knocked down FOXC2 expression with siRNA and examined OPN expression in response to Pi treatment. Knockdown was confirmed by qRT-PCR and Western blotting (not shown). Pi-induced OPN secretion was measured in the medium by ELISA which identified a significant increase in response to treatment with elevated Pi (Fig. 3B). Further, the increase in response to Pi was blocked in cells transfected with siRNA targeting FOXC2 (Fig. 3B). These results demonstrate the requirement of FOXC2 expression for Pi-induced OPN secretion. To confirm the functional requirement of FOXC2 for Pi-induced OPN expression we overexpressed FOXC2 in HCT116 colon carcinoma cells, which have low endogenous OPN levels. Overexpression of FOXC2 resulted in increased OPN protein levels but only in the presence of elevated Pi (Fig. 3C) suggesting the requirement of Pi-specific co-factors. To confirm the direct regulation of OPN expression by FOXC2 we used a reporter luciferase construct containing 2kb of the murine OPN (spp1) promoter region. The luciferase construct was stimulated by Pi and further enhanced by overexpression of FOXC2 (Fig. 3D). We used siRNA targeting FOXC2 in combination with the OPN luciferase assay to further confirm the functional requirement for Pi-induced OPN expression. The knockdown of FOXC2 in MDA-MB-231 cells eliminated the Pi-induced stimulation of OPN promoter activity (Fig. 3E). Collectively the results identify FOXC2 as a novel regulator of OPN expression. Given the significance of OPN in cancer promotion and metastasis this regulatory relationship may be a key event in the progression stage of cancer etiology.

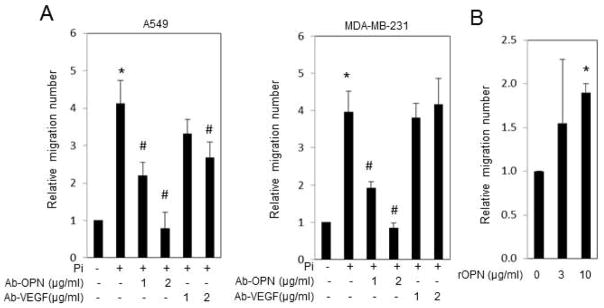

OPN and Vegfα are required for high Pi-induced angiogenesis

OPN and Vegfα are both secreted factors. To determine if they are required for the increased HUVEC migration mediated by cancer cell CM, we used antibodies to neutralize the proteins. A549 and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with Pi and CM collected and incubated with increasing amounts of OPN or Vegfα antibodies for 1h prior to addition to the HUVEC migration assay. Results revealed that an antibody targeting OPN dose dependently inhibited the Pi-induced increase in migration whereas an antibody targeting Vegfα only partially inhibited the response in A549 and did not alter migration induced by MDA-MB-231 CM (Fig. 4A). These results suggest that OPN, secreted from cancer cells in response to a high Pi environment, is an important factor in HUVEC cell migration. We confirmed the significance of OPN in the migration response by spiking untreated A549 CM with recombinant OPN and performing the migration assay. Indeed, increasing the OPN concentration increased HUVEC migration (Fig. 4B), in agreement with previous studies using recombinant or overexpressed OPN [31–33].

Figure 4. Antibody neutralization of OPN blocks Pi-conditioned medium mediated HUVEC migration.

(A) A549 and MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in the growth medium (1mM Pi) and treated with 4mM of Pi (5mM final) for 6 or 3 days respectively. The medium was changed to serum free-phenol free for 24h and collected as conditioned medium (CM). The conditioned medium was incubated with antibodies to OPN or Vegfα for 1 hour prior to addition to the two-chamber HUVEC migration assay. Cells in the lower chamber were counted after 20h. Results expressed as mean±SD (n=3–5). (*P<0.05, compared with 1mM Pi treatment or control; # P<0.05, compared with +Pi treatment; Student’s t-test). (B) A549 CM (untreated) was spiked with recombinant OPN (BSA was used in the control) and two-chamber HUVEC migration assay performed. Results expressed as mean±SD (n=3). (*P<0.05, compared with control (0μg/ml); Student’s t-test).

OPN functions as a cytokine affecting a range of cell types, and is associated with immune response, bone metabolism and cancer metastasis [34,35]. Although the mechanisms are not clear, OPN has been demonstrated to directly act on endothelial cells to promote angiogenesis [31–33] and to act in an autocrine/paracrine manner on the tumor cell to induce expression of Vegfα [36]. Our results identified the requirement of cancer cell secreted OPN and Vegfα for the stimulation of endothelial migration although there was variation between cell types. Whereas the stimulatory effect of CM from Pi-stimulated A549 cells on migration was partially blocked by addition of a Vegfα antibody, MDA-MB-231 conditioned medium was not affected (Fig. 4A). The inhibition by both antibodies in A549 cells also suggests the possibility that there are multiple compensatory factors involved in cancer cell mediated endothelial cell migration which differ between cell types. Although our current in vitro studies have focused on potential paracrine signaling, a previous study has identified an increase in serum OPN in response to a high Pi diet [1] suggesting the possibility that Pi availability might alter tumorigenesis in an endocrine manner as well.

Our in vitro results suggest that targeting Pi consumption by growing tumors might reduce or block progression to a metastatic phenotype. This could be accomplished by two means. If tumors require increased Pi, relative to normally functioning cells, limiting the available Pi systemically through diet could alter growth of these more metabolically active cells while preserving less metabolically active healthy cells. Secondly, one could target the upstream membrane event required for initiation of Pi-signaling events. Previous studies have identified discrete signaling events stimulated by cell exposure to increased Pi such as activation of N-ras, ERK1/2, Akt and resulting in changes in transcription and protein translation [1,14,19,37–40]. These downstream signaling events require both Pi-transport and FGF receptor signaling [14,41] suggesting potential targets to limit Pi-induced signaling. Whether these membrane proteins can be selectively targeted in cancer cells remains to be determined.

Pi is critical to cell function and involved in varied processes including DNA formation and lipid function as well as a key component of energy metabolism in the form of ATP and therefore completely starving a cell of Pi could be detrimental. However, the importance of Pi in cellular processes and growth suggests that rapidly dividing and highly metabolic active cells have an increased requirement for Pi, in addition to numerous other nutrients. This is supported by in vivo studies that found increased Pi uptake, metabolism, and retention in tumors relative to the corresponding normal tissue controls [42–44]. Taken with our results presented here one could speculate that it is advantageous for a rapidly dividing cell to coordinate increased cellular Pi consumption with increased nutrient supply through angiogenesis or neovascularization. This would be beneficial to certain tissues under normal conditions such as the skeleton in response to bone remodeling or fracture repair but also pathological conditions such as tumor growth. In support of a coordination of Pi-transport and angiogenesis, a recent study investigating the knockout of the specific sodium dependent Pi-transporter Slc20A1 (Pit-1) identified anemic yolk sacs that lack mature vasculature relative to wild type [45]. Whether cancer cells develop a higher propensity or efficacy towards this coordinated relationship relative to healthy cells is still to be determined.

In summary, we have identified a novel mechanism by which a common dietary element, Pi, influences cancer cell behavior. Cancer cells exposed to elevated extracellular Pi stimulated increased tube formation and endothelial cells migration in vitro. We defined FOXC2 as Pi-responsive and as a required transcriptional regulator in the response. We additionally identified OPN as a regulatory secreted effector protein. Importantly, this mechanism was defined in two different cancer cell lines suggesting the results might be generally applicable to the cancer etiology and produces the hypothesis that modifying Pi availability to transformed, pre-cancerous cells might represent a novel therapeutic target to stop progression to malignancy.

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute CA136716 and by Award Number I01BX002363 from the Biomedical Laboratory Research & Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development. We thank Dr. Oskar Laur of The Emory DNA Custom Cloning Core Facility for expert technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- Pi

inorganic phosphate

- FOXC2

Forkhead box protein C2

- OPN

osteopontin

- Vegf

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- CM

conditioned medium

- HUVEC

human umbilical vascular endothelial cell

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Camalier CE, Young MR, Bobe G, Perella CM, Colburn NH, Beck GR., Jr Elevated phosphate activates N-ras and promotes cell transformation and skin tumorigenesis. Cancer prevention research. 2010;3(3):359–370. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin H, Xu CX, Lim HT, et al. High dietary inorganic phosphate increases lung tumorigenesis and alters Akt signaling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(1):59–68. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-306OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wulaningsih W, Michaelsson K, Garmo H, et al. Inorganic phosphate and the risk of cancer in the Swedish AMORIS study. BMC cancer. 2013;13:257. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calvo MS. Dietary phosphorus, calcium metabolism and bone. The Journal of nutrition. 1993;123(9):1627–1633. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.9.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kemi VE, Karkkainen MU, Karp HJ, Laitinen KA, Lamberg-Allardt CJ. Increased calcium intake does not completely counteract the effects of increased phosphorus intake on bone: an acute dose-response study in healthy females. The British journal of nutrition. 2008;99(4):832–839. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507831783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huttunen MM, Pietila PE, Viljakainen HT, Lamberg-Allardt CJ. Prolonged increase in dietary phosphate intake alters bone mineralization in adult male rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2006;17(7):479–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huttunen MM, Tillman I, Viljakainen HT, et al. High dietary phosphate intake reduces bone strength in the growing rat skeleton. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2007;22(1):83–92. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Draper HH, Sie TL, Bergan JG. Osteoporosis in aging rats induced by high phosphorus diets. J Nutr. 1972;102(9):1133–1141. doi: 10.1093/jn/102.9.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giachelli CM. The emerging role of phosphate in vascular calcification. Kidney international. 2009;75(9):890–897. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Onufrak SJ, Bellasi A, Shaw LJ, et al. Phosphorus levels are associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in the general population. Atherosclerosis. 2008;199(2):424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tonelli M, Sacks F, Pfeffer M, Gao Z, Curhan G. Relation between serum phosphate level and cardiovascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2627–2633. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.553198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohnishi M, Razzaque MS. Dietary and genetic evidence for phosphate toxicity accelerating mammalian aging. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2010;24(9):3562–3571. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-152488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuro-o M. A potential link between phosphate and aging--lessons from Klotho-deficient mice. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2010;131(4):270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camalier CE, Yi M, Yu LR, et al. An integrated understanding of the physiological response to elevated extracellular phosphate. Journal of cellular physiology. 2013;228(7):1536–1550. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zetter BR. Angiogenesis and tumor metastasis. Annual review of medicine. 1998;49:407–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ausprunk DH, Folkman J. Migration and proliferation of endothelial cells in preformed and newly formed blood vessels during tumor angiogenesis. Microvascular research. 1977;14(1):53–65. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(77)90141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seo S, Fujita H, Nakano A, Kang M, Duarte A, Kume T. The forkhead transcription factors, Foxc1 and Foxc2, are required for arterial specification and lymphatic sprouting during vascular development. Developmental biology. 2006;294(2):458–470. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck GR, Jr, Knecht N. Osteopontin regulation by inorganic phosphate is ERK1/2-, protein kinase C-, and proteasome-dependent. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(43):41921–41929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck GR, Jr, Zerler B, Moran E. Phosphate is a specific signal for induction of osteopontin gene expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(15):8352–8357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140021997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Tanani MK, Campbell FC, Kurisetty V, Jin D, McCann M, Rudland PS. The regulation and role of osteopontin in malignant transformation and cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17(6):463–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Craig AM, Bowden GT, Chambers AF, et al. Secreted phosphoprotein mRNA is induced during multi-stage carcinogenesis in mouse skin and correlates with the metastatic potential of murine fibroblasts. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 1990;46(1):133–137. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910460124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rittling SR, Chambers AF. Role of osteopontin in tumour progression. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(10):1877–1881. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirama M, Takahashi F, Takahashi K, et al. Osteopontin overproduced by tumor cells acts as a potent angiogenic factor contributing to tumor growth. Cancer letters. 2003;198(1):107–117. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(03)00286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyden S. The chemotactic effect of mixtures of antibody and antigen on polymorphonuclear leucocytes. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1962;115:453–466. doi: 10.1084/jem.115.3.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaestner KH, Knochel W, Martinez DE. Unified nomenclature for the winged helix/forkhead transcription factors. Genes & development. 2000;14(2):142–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myatt SS, Lam EW. The emerging roles of forkhead box (Fox) proteins in cancer. Nature reviews Cancer. 2007;7(11):847–859. doi: 10.1038/nrc2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sano H, LeBoeuf JP, Novitskiy SV, et al. The Foxc2 transcription factor regulates tumor angiogenesis. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2010;392(2):201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mani SA, Yang J, Brooks M, et al. Mesenchyme Forkhead 1 (FOXC2) plays a key role in metastasis and is associated with aggressive basal-like breast cancers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(24):10069–10074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703900104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollier BG, Tinnirello AA, Werden SJ, et al. FOXC2 Expression Links Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Stem Cell Properties in Breast Cancer. Cancer research. 2013;73(6):1981–1992. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asou Y, Rittling SR, Yoshitake H, et al. Osteopontin facilitates angiogenesis, accumulation of osteoclasts, and resorption in ectopic bone. Endocrinology. 2001;142(3):1325–1332. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.3.8006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi F, Akutagawa S, Fukumoto H, et al. Osteopontin induces angiogenesis of murine neuroblastoma cells in mice. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2002;98(5):707–712. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dai J, Peng L, Fan K, et al. Osteopontin induces angiogenesis through activation of PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 in endothelial cells. Oncogene. 2009;28(38):3412–3422. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giachelli CM, Steitz S. Osteopontin: a versatile regulator of inflammation and biomineralization. Matrix biology: journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 2000;19(7):615–622. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Denhardt DT, Giachelli CM, Rittling SR. Role of osteopontin in cellular signaling and toxicant injury. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:723–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chakraborty G, Jain S, Kundu GC. Osteopontin promotes vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent breast tumor growth and angiogenesis via autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. Cancer research. 2008;68(1):152–161. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beck GR, Jr, Moran E, Knecht N. Inorganic phosphate regulates multiple genes during osteoblast differentiation, including Nrf2. Exp Cell Res. 2003;288(2):288–300. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang SH, Yu KN, Lee YS, et al. Elevated inorganic phosphate stimulates Akt-ERK1/2-Mnk1 signaling in human lung cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35(5):528–539. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0477OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin H, Hwang SK, Yu K, et al. A high inorganic phosphate diet perturbs brain growth, alters Akt-ERK signaling, and results in changes in cap-dependent translation. Toxicological sciences: an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2006;90(1):221–229. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Julien M, Khoshniat S, Lacreusette A, et al. Phosphate-dependent regulation of MGP in osteoblasts: role of ERK1/2 and Fra-1. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2009;24(11):1856–1868. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamazaki M, Ozono K, Okada T, et al. Both FGF23 and extracellular phosphate activate Raf/MEK/ERK pathway via FGF receptors in HEK293 cells. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111(5):1210–1221. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elser JJ, Kyle MM, Smith MS, Nagy JD. Biological stoichiometry in human cancer. PloS one. 2007;2(10):e1028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas CI, Harrington H, Bovington MS. Uptake of radioactive phosphorus in experimental tumors. III. The biochemical fate of P32 in normal and neoplastic ocular tissue. Cancer research. 1958;18(9):1008–1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones HB, Chaikoff IL, Lawrence JH. Phosphorus metabolism of neoplastic tissues (mammary carcinoma, lymphoma, lymphosarcoma) as indicated by radioactive phosphorus. Cancer research. 1940;40:243–250. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Festing MH, Speer MY, Yang HY, Giachelli CM. Generation of mouse conditional and null alleles of the type III sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporter PiT-1. Genesis. 2009;47(12):858–863. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]