Background: Aberrantly elevated integrin-linked kinase (ILK) activity is associated with inflammatory diseases and tumors.

Results: In response to bacterial stimulus and infection, ILK modulates pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α production and activates nuclear factor κB signaling via p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation.

Conclusion: ILK promotes pro-inflammatory signaling during immune responses to diverse stimuli.

Significance: ILK is a potential therapeutic target for inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Inflammation, Innate Immunity, Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), NF-kappa B, Phosphatidylinositide 3-Kinase (PI 3-Kinase), Small Molecule, Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF), Integrin-linked Kinase (ILK), p65

Abstract

Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is a ubiquitously expressed and highly conserved serine-threonine protein kinase that regulates cellular responses to a wide variety of extracellular stimuli. ILK is involved in cell-matrix interactions, cytoskeletal organization, and cell signaling. ILK signaling has also been implicated in oncogenesis and progression of cancers. However, its role in the innate immune system remains unknown. Here, we show that ILK mediates pro-inflammatory signaling in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Pharmacological or genetic inhibition of ILK in mouse embryonic fibroblasts and macrophages selectively blocks LPS-induced production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α). ILK is required for LPS-induced activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and transcriptional induction of TNF-α. The modulation of LPS-induced TNF-α synthesis by ILK does not involve the classical NF-κB pathway, because IκB-α degradation and p65 nuclear translocation are both unaffected by ILK inhibition. Instead, ILK is involved in an alternative activation of NF-κB signaling by modulating the phosphorylation of p65 at Ser-536. Furthermore, ILK-mediated alternative NF-κB activation through p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation also occurs during Helicobacter pylori infection in macrophages and gastric cancer cells. Moreover, ILK is required for H. pylori-induced TNF-α secretion in macrophages. Although ILK-mediated phosphorylation of p65 at Ser-536 is independent of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway during LPS stimulation, upon H. pylori infection this event is dependent on the PI3K/Akt pathway. Our findings implicate ILK as a critical regulatory molecule for the NF-κB-mediated pro-inflammatory signaling pathway, which is essential for innate immune responses against pathogenic microorganisms.

Introduction

Chronic inflammation and associated disorders are major health problems worldwide. One of the potent inducers of chronic inflammation and septic shock is lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a major component of the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria. LPS activates host cells to produce various pro-inflammatory mediators, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-8, and nitric oxide (NO) (1, 2). These mediators secreted by macrophages constitute innate immune responses by counteracting the effects of pathogenic stimuli. However, excessive or unregulated production of pro-inflammatory mediators may lead to acute phase endotoxemia leading to organ failure, shock, tissue injury, and even death (2, 3). Among the pro-inflammatory mediators, TNF-α is well known for its crucial role in the regulation of normal immunity, as well as the pathological inflammatory response seen in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn disease (4). Therefore, therapeutic approaches to regulate the production of pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α can be beneficial for the treatment of patients suffering from these chronic inflammatory disorders (5).

LPS-stimulated signaling events leading to the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators include the activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NF-κB).4 The prototypical form of NF-κB is a ubiquitously expressed heterodimeric complex consisting of a DNA binding subunit (p50) and a transactivation subunit (p65/RelA). In unstimulated cells, this complex is retained in the cytoplasm by IκB-α, a classical (or canonical) inhibitor of NF-κB activation. Upon stimulation, NF-κB signaling is initiated by activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, which phosphorylates IκB-α at two N-terminal serine residues. The phosphorylation of IκB-α subsequently triggers its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, thereby facilitating nuclear translocation of the NF-κB complex. Given the broad spectrum of biological outcomes of NF-κB signaling, its activation is subject to tight regulation. Apart from the classical NF-κB signaling pathway, several studies have identified the existence of multiple additional pathways; however, the molecular mechanisms for many of them remain to be fully characterized (6–8). In addition to the events regulating the nuclear translocation of the NF-κB complex, post-translational modifications of NF-κB proteins have emerged as critical regulators of transcriptional activities (9–12). For example, the transcriptional activity of p65, the main effector subunit of the classical NF-κB pathway, is regulated by the post-translational modifications phosphorylation and acetylation (13), of which phosphorylation is by far the most studied (14). Despite considerable effort, the signaling events that culminate in the modification of p65 are less well characterized. Recent findings have shown that phosphorylation of the p65 subunit at Ser-536 is an alternative to classical NF-κB activation (15–19). In this pathway, IκB-α-independent nuclear translocation of pp65Ser-536 is critical for the regulation of target genes. The phosphorylation status of p65 Ser-536 has also been described as a critical factor for diverse biological functions, ranging from fine-tuning of NF-κB transcriptional activity (20) to modulating neurite growth in the nervous system (21) and cancer cell survival (22). These observations suggest that the phosphorylation of p65 at Ser-536 serves as an integrator for multiple signaling pathways during NF-κB activation. Because the earlier reports showing that IKKα/β plays an essential role in LPS-induced p65 phosphorylation at Ser-536 (19, 23), three other protein kinases, IKKϵ, TBK1 (TANK-binding kinase 1), and RSK1 (ribosomal S6 kinase 1), have been shown to phosphorylate p65 Ser-536 under certain physiological conditions and stimuli (14). Nevertheless, given the versatile nature of the NF-κB transcriptional activity, a signaling cascade defining the critical role of these kinases is not well defined and suggests that other, as yet unidentified, kinases are involved.

Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is a multifunctional serine/threonine kinase that was originally discovered as an integrin-interacting protein localizing in focal adhesions (24). ILK is highly conserved and widely expressed in mammalian tissues, also localizing in multiple subcellular compartments. It plays a central role in transducing multiple signaling pathways linked to cell-matrix interactions, and it regulates different cellular processes such as growth, proliferation and mitosis, migration, invasion, vascularization, apoptosis, angiogenesis, embryonic development, and tissue homeostasis (25, 26). In contrast, overexpression of ILK is often associated with human malignancies. Abundant evidence has demonstrated that both ILK protein levels and corresponding activity are enhanced in many cancers, such as colon, gastric, prostate, breast, as well as melanoma (27, 28), indicating its potential as an attractive therapeutic target for cancer treatment. Despite considerable studies, the mechanism underlying the role of ILK in the progression of cancer is incompletely understood. Interestingly, a number of reports indicated a connection between ILK and NF-κB activation, a signaling pathway that is often dysregulated in inflammation and cancers. First, NF-κB reporter activity and LPS-induced NO synthesis are both suppressed by the dominant-negative ILK or a small molecule ILK inhibitor KP-392 (29). LPS-induced IκB-α degradation was also inhibited by a high concentration of KP-392 (50 μm) in J774 macrophages. Second, IKK(α/β) up-regulation and NF-κB activation by the receptor tyrosine kinase HER2/neu involved ILK-induced Akt activity (30). The same study also showed that TNF-α-induced IκB-α degradation was also suppressed by the dominant-negative ILK (30). ILK was shown to be important for human renal carcinoma cell survival through its involvement in Akt and NF-κB activation (31), and collagen I-induced epithelial mesenchymal transition is mediated by ILK-dependent IκB-α phosphorylation and p65 nuclear translocation (32). In human lung cancer cells, ILK-induced epithelial mesenchymal transition was also shown to be dependent on NF-κB activation (33). In human mesangial cells, collagen I-induced pro-survival NF-κB activation was also regulated by ILK, suggesting a link between the ILK-NF-κB axis and glomerular dysfunction (34). In melanoma cell lines, ILK was required for IL-6 expression through NF-κB activation as ILK silencing not only decreased IL-6 synthesis but also reduced IκB-α degradation, p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation, and nuclear translocation (35). These studies largely suggest a role for ILK in classical NF-κB signaling. However, the role of ILK in Toll-like receptor (TLR)-mediated NF-κB signaling has not been thoroughly investigated. In this study, using ILK-specific genetic knockdown and a selective small molecule inhibitor, we have shown that ILK is not required for the LPS-induced classical NF-κB signaling pathway involving IκB-α degradation and nuclear translocation of p65. Rather, ILK modulates LPS-stimulated NF-κB transcription activity through p65 phosphorylation at Ser-536 and is required for LPS-induced transactivation of p65 through Ser-536. Using an in vitro model of Helicobacter pylori infection, we show that ILK is required for H. pylori-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation and TNF-α secretion. Finally, we show that the regulation of p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation by ILK is a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt-independent process in response to LPS, but in response to H. pylori, the infection is dependent on PI3K/Akt.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Ethics Statement

All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the protocols approved by the Monash University Animal Ethics Committee. All animal work was conducted under the following animal ethics approval numbers assigned by the Monash University Animal Ethics Committee: MMCA/2009/43/BC (for maintaining ILKflox/flox C57BL6/J mice); MMCA/2012/32/BC (for maintaining ILKflox/flox;LysM-Cre C57BL6/J mice); and MMCA/2012/45 (for the use of both ILKflox/flox and ILKflox/flox;LysM-Cre C57BL6/J mice for scientific research purposes). All animal care and use protocols adhered to the national guidelines provided by the Bureau of Animal Welfare, Victoria, Australia.

Cell Culture and Treatments

Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (freshly isolated cells) and immortalized mouse spleen macrophages were grown in culture with DMEM (supplied with l-glutamine) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin, and streptomycin (100 units/ml) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. RAW264.7 cells (obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC)), THP-1 (ATCC), AGS (ATCC), and primary bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) (freshly isolated) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (supplied with l-glutamine) supplemented with 10% FCS, penicillin, and streptomycin (100 units/ml) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. All cell lines were grown for no more than 10 passages, and cells at logarithmic growth phase were used for the experiments. The following inhibitors were used: ILK inhibitor QLT-0267 (36), Akt1/2 kinase inhibitor (Sigma), and PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (Calbiochem). For inhibitor treatment, cell culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing inhibitor at the indicated concentration(s) and incubated for 1 h prior to and during LPS (100 ng/ml) treatment or for 1 h prior to H. pylori infection.

Mouse Handling and Isolation of Primary Cells

All mice were housed in specific pathogen-free facilities at the Monash Medical Centre Animal Facility, Melbourne, Australia. Primary MEFs were isolated from 12.5 to 13.5 embryos from C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) and ilkloxP/loxP mice using the standard protocol. Cells were expanded as a monolayer in culture dishes and used for experiments within five passages. Primary BMDMs were isolated from 6- to 8-week-old mice (C57BL/6 WT, ilkloxP/loxP, ilkloxP/loxP;LysMCre and TNF-α KO) using the standard protocol. TNF-α KO mice were kindly provided by Associate Prof. John Silke, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Melbourne, Australia. Bone marrow cells were differentiated to macrophages in culture dishes using L929-conditioned medium for 5 days.

Adeno-Cre Virus Infection

ilkloxP/loxP (and WT control) MEFs were infected with adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase (Ad5CMVCre-eGFP, BCM Cell and Gene Therapy Centre). MEFs were cultured in 10-cm dishes to 60–70% confluence and then infected with 5 × 108 viral particles for 4 h in 5 ml of DMEM containing 10% FCS. After 4 h, cells were washed once with fresh DMEM with FCS and incubated for 3 days prior to analysis.

H. pylori Culture and Infection

H. pylori bacteria strain 251 (37) was grown under microaerophilic conditions at 37 °C. H. pylori strain was cultured in blood agar plates supplemented with FCS as described earlier (38). Briefly, following 2 days of incubation at 37 °C under microaerophilic conditions on blood agar, bacteria were harvested from the plate and cultured in brain heart fusion broth (Oxoid) containing 10% FCS at 37 °C under microaerophilic conditions for 1 day prior to being used for infection. For in vitro infection experiments, AGS cells and primary BMDMs were grown overnight in 12-well plates at 3 × 105 cells per well. Freshly cultured H. pylori was added to the cells in a ratio of 10 H. pylori bacterial cells/cell (m.o.i. = 10) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with FCS and l-glutamine without antibiotics for 1 h. Following infection for 1 h, the medium was removed, and complete RPMI 1640 medium was added. For H. pylori infection in THP-1 macrophages, THP-1 monocytes were plated in either 96-well plates at 4 × 104 cells/well or 12-well plates at 3 × 105 cells/well in complete RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 50 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate to induce the differentiation of monocytes to macrophages overnight. The following day, culture medium was replaced with RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS) and l-glutamine without antibiotics, and H. pylori infection was carried out by adding bacteria to the cells in a ratio of five H. pylori bacterial cells/cell (m.o.i. = 5) for 1 h followed by the replacement of medium with complete RPMI 1640 medium. Following 1 h infection, cells in 96-well plates were further incubated for 4 h prior to the collection of supernatant for human TNF-α detection by ELISA, and cells in 12-well plates were immediately harvested for total protein extraction for Western blot analysis.

Transfection

RAW264.7 and AGS cells were transfected with plasmid DNAs using Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. Transient transfections in RAW264.7 and NIH3T3 cells were carried out in 96-well plates, and cells were seeded overnight at 2 × 104 and 1.5 × 104 cells per well, respectively. For NF-κB luciferase assay in RAW264.7 cells, cells in each well were transfected with 40 ng of NF-κB-Luc and 5 ng of Renilla-luc vector using Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen). For p65-Gal4 transactivation assay in RAW264.7 and NIH3T3 cells, 20 ng of p65-Gal4 or p65S536A-Gal4 (kind gifts from Prof. Luke O'Neill, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland), 20 ng of Gal4-Luc, 40 ng of Renilla-luc vector, and the indicated amount of ILK-expressing plasmid were used for transfection. In all cases, the amounts of DNA transfected were kept constant by adding an appropriate amount of empty vector. For transfection in AGS cells, cells were seeded overnight in 12-well plates at 1.5 × 105 cells per well and transfected with 300 ng of mCherry expression vector containing either ILKWT or ILKR211A. 60–70% transfection efficiency was achieved in these cells, as indicated by mCherry-positive cells on the day after transfection. All transfections were carried out in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) medium. Cells were incubated for 18–24 h after transfection prior to analysis.

Luciferase Reporter Assays

Following transfection with luciferase reporter vector for 18–24 h, cells were either left untreated or treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 6 h. To measure firefly luciferase activity, cells were lysed in 1× passive lysis buffer (Promega) and incubated at −80 °C until analysis. Firefly luciferase activity was measured with a luminometer (FLUOstar OPTIMA, BMG Labtech) and normalized against the Renilla luciferase activity by using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). Total luciferase activities were expressed as units based on a ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase. Samples were assayed in triplicate for each condition in these experiments.

ELISA

Cells were treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) or infected with H. pylori (m.o.i. = 5 or 10) for the indicated periods, and the supernatants were collected and stored in −80 °C until analysis. The amount of TNF-α in the supernatant was assessed using a commercially available mouse or human TNF-α-specific ELISA kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the RNA mini columns (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The concentration and purity of the RNA samples were determined based on the absorbance ratio at 260/280 (nm). An equal amount of RNA (1000 ng) from each sample was reverse-transcribed in a total volume of 20 μl for complementary DNA synthesis using SuperScript First Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative real time PCRs were performed in 20 μl of reaction mixture containing 10 μl of Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems), 0.5 μm of each primer (forward and reverse), and 1–2 μl of cDNA template. Reactions were performed in Bio-Rad real time PCR detection system (iQ5 Multicolor Real Time PCR Detection System). All reactions were carried out at 90 °C for 8 min 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 1 min. A melting curve was generated at the end to ensure uniformity of the product. GAPDH was used as an internal control to normalize samples, and all data were analyzed using the standard comparative threshold cycle (CT) method. The following primers were used: TNF-α forward primer, 5′-GAAAAGCAAGCCAGCCAACCA-3′, and TNF-α reverse primer, 5′-CGGATCATGCTTTCTGTGCTC-3′; GAPDH forward primer, 5′-CATCTTCCAGGAGCGAGATCCC-3′, and GAPDH reverse primer, 5′-TTCACACCCATGACGAACAT-3′.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed on ice in RIPA buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics). Protein lysates were kept at −20 °C until used for Western analysis. Protein concentrations were measured using a Bradford Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts of protein samples were denatured at 95 °C for 5 min in SDS sample buffer (3× composition: 188 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 3% SDS, 30% glycerol, 0.01% bromphenol blue, 15% β-mercaptoethanol) and subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis. Separated proteins on the gel were electrotransferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore), blocked in 25% Odyssey blocking buffer in PBS for 1 h at room temperature, and immunoblotted overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody. Membranes were washed (three times for 5 min) in PBS with 0.01% Tween 20 (PBST) and incubated with Alexa 680- or Alexa 760-conjugated secondary antibody for 45 min at room temperature. Membranes were washed again (three times for 5 min) in PBST prior to scanning in an Odyssey Infrared Imaging system. The following primary antibodies directed against proteins of both human and mouse origin were used at 1:1000 dilution: ILK rabbit polyclonal antibody (4G9, Cell Signaling); p65 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Cell Signaling); phospho-p65 (Ser-536) rabbit polyclonal antibody (Cell Signaling); IκB-α rabbit polyclonal antibody (Cell Signaling); phospho-Akt (Ser-473) rabbit polyclonal (Cell Signaling); Akt rabbit polyclonal (Cell Signaling); and pan-actin mouse monoclonal antibody (NeoMarker, Fremont, CA). The following secondary antibodies were used at 1:2500 dilution: anti-rabbit secondary Alexa 680-conjugated antibody (Invitrogen) and anti-mouse secondary Alexa 760-conjugated antibody (Invitrogen).

Immunofluorescence

Cells were grown in 24-well plates on coverslips. Following treatments, cells on coverslips were fixed with 10% buffered formalin (Orion) for 20 min followed by three washes in PBS. Cells were permeabilized by treating with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min followed by three washes in PBS. Cells were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in Odyssey blocking buffer (diluted 1:4 in PBS), followed by primary antibody treatment (rabbit polyclonal p65 at 1:500 dilution in blocking buffer) for 1 h at room temperature. Following secondary antibody treatment (goat anti-rabbit Alexa 568 at 1:100 dilution in blocking buffer) for 30 min, cells were washed three times, mounted in SlowFade® Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen), and sealed with nail polish prior to microscopic observations.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± S.E. Statistical analysis between two samples was performed using Student's t test using GraphPad Prism 5.0.

RESULTS

ILK Modulates LPS-induced TNF-α Production in Mouse and Human Cells

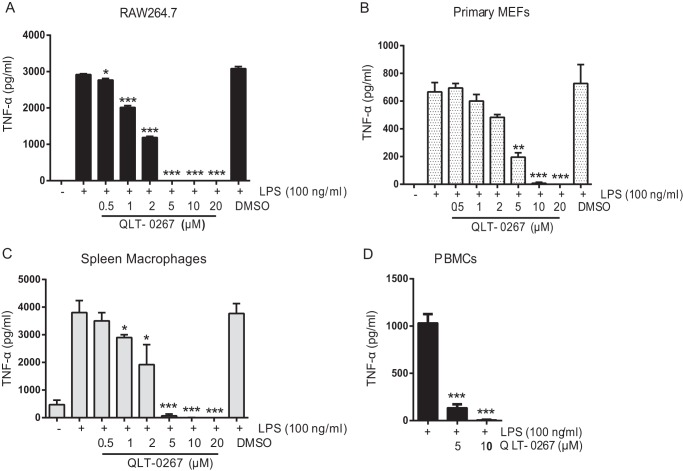

To test involvement of ILK in LPS-induced inflammatory responses, we utilized two approaches as follows: either a selective small molecule ILK inhibitor QLT-0267 (36) or Cre-lox technology was used to inhibit activity or delete ILK from cells, respectively. QLT-0267 has been characterized as a highly selective ILK inhibitor among a variety of other protein kinases (39). Pretreatment with QLT-0267 inhibits ILK kinase activity in a broad range of cells and in animal models (40–44). Based on reported IC50 of QLT-0267 in the range of 2–5 μm depending on cell types (39, 45–47), we treated primary MEFs, spleen macrophages, and the RAW264.7 macrophage cell line with 1–20 μm QLT-0267 for 1 h prior to and during 24 h of stimulation with LPS (100 ng/ml). QLT-0267 significantly inhibited LPS-induced TNF-α production in a dose-dependent manner, in all three mouse cell types (Fig. 1, A–C). Similarly, QLT-0267 pretreatment of freshly isolated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells significantly inhibited LPS-induced TNF-α production at similar concentrations (Fig. 1D). QLT-0267 treatment for 24 h did not affect the viability of the cells tested as confirmed by Alamar Blue assay (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

ILK inhibitor QLT-0267 prevents LPS-induced TNF-α production. RAW264.7 cells (A), primary MEFS (B), and immortalized spleen macrophages (C) were pretreated with a range of concentrations of QLT-0267 from 0.5 to 20 μm, followed by LPS (100 ng/ml) stimulation for 24 h. TNF-α production in the supernatants was measured by ELISA. D, TNF-α production in the supernatants of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 24 h with and without QLT-0267 (5 and 10 μm) pretreatment. Data are representative of three different experiments. p values were calculated by two-tailed t test and were relative to LPS stimulation alone: *, 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05; **, 0.001 < p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001.

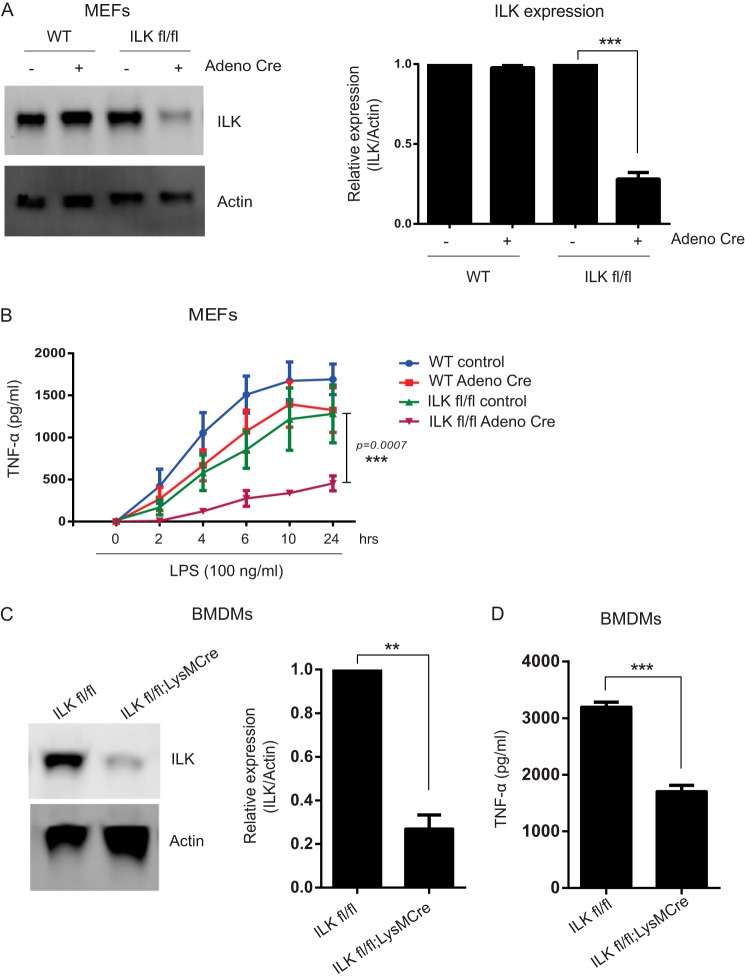

To confirm that blocking ILK inhibited LPS-induced TNF-α production, we wanted to investigate whether genetic knockdown of ILK also had an inhibitory effect. To accomplish this, we isolated MEFs from ilkloxP/loxP mice and infected these cells with Adeno-Cre. Using this method, we achieved 70–80% depletion of ILK protein in ilkloxP/loxP MEFs relative to untreated MEFs or to Adeno-Cre-treated WT MEFs (Fig. 2A). This level of ILK depletion resulted in a significant reduction in LPS-induced TNF-α production by the ILK-deficient MEFs (Fig. 2B). Thus, inhibiting ILK by two independent methods resulted in a significant inhibition of LPS-induced TNF-α production in mouse and human cells.

FIGURE 2.

ILK is required for LPS-induced TNF-α production. A, left panel, representative Western blot analysis showing Adeno-Cre-mediated ILK knockdown in ILKfl/fl MEFs. Right panel, densitometric analysis showing the differences in ILK protein bands against actin in MEFs over more than three different experiments. B, time course of LPS-induced TNF-α production in WT and ILKfl/fl MEFs with and without Adeno-Cre virus infection. C, left panel, representative Western blot analysis showing LysM-Cre-mediated ILK deletion in BMDMs. Right panel, densitometric analysis showing the differences in ILK protein bands against actin in BMDMs over more than three different experiments. D, TNF-α production in the supernatants of BMDMs (ILKfl/fl and ILKfl/fl;LysMCre) treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 h. Data are representative of three different experiments. p values were calculated by two-tailed t test and were relative to LPS stimulation alone: **, 0.001 < p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001.

Our results with small molecule- and Cre-mediated ILK inhibition in cultured cells prompted us to investigate the effect of in vivo ILK deletion on TNF-α induction. To delete ILK selectively from inflammatory cells, we crossed ilkloxP/loxP mice with a LysM-Cre strain, which selectively expresses Cre recombinase in the myeloid cell lineage (notably monocytes and mature macrophages). BMDMs were isolated from ilkloxP/loxP;LysMCre mice and cultured ex vivo as described under “Experimental Procedures.” We found that ILK protein levels in ilkloxP/loxP;LysMCre BMDMs were decreased by 70–80% compared with ilkloxP/loxP BMDMs (Fig. 2C). We stimulated cultured BMDMs of each genotype and measured TNF-α production as above. LPS induction of TNF-α was markedly inhibited in ilkloxP/loxP;LysMCre BMDMs relative to ilkloxP/loxP controls, corroborating our in vitro results (Fig. 2D).

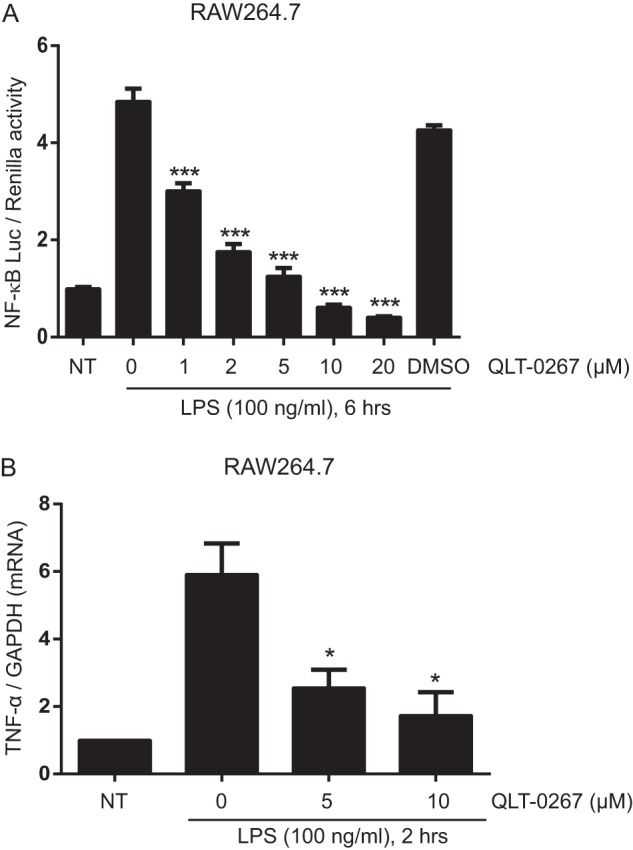

Inhibiting ILK Suppresses LPS/TLR4-induced NF-κB Activity and TNF-α Transcription

As NF-κB plays a crucial role in TLR-induced transcriptional responses, we investigated whether ILK plays a role in TLR-induced NF-κB activation. Accordingly, the effect of QLT-0267 on TLR-mediated activation of an NF-κB reporter gene was assessed. RAW264.7 cells were transiently transfected with an NF-κB-luciferase reporter, and after 24 h cells were either left untreated or treated with vehicle or QLT-0267 at 1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 μm for 1 h prior to stimulation with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 6 h. The results (Fig. 3A) show that QLT-0267 pretreatment effected dose-dependent inhibition of LPS-induced luciferase activity, with over 80% inhibition at a concentration of 5 μm inhibitor. These results support a role for ILK in activating NF-κB transcriptional programs downstream of TLR4. The inhibitory effect of QLT-0267 on LPS-induced NF-κB transcriptional activation suggests that QLT-0267-mediated inhibition of TNF-α production in response to LPS occurs at the transcriptional level. To confirm this, quantitative RT-PCR was employed to measure levels of LPS-induced TNF-α mRNA expression in RAW264.7 macrophages that had been pretreated with QLT-0267 inhibitor or vehicle, prior to stimulation with 100 ng/ml LPS for 2 h. Pretreatment with 5 μm ILK inhibitor suppressed induction of TNF-α mRNA, by over 50% relative to vehicle controls (Fig. 3B). Together, these results suggest that inhibition of ILK suppresses LPS-induced TNF-α expression at the transcriptional level through the inhibition of NF-κB activation.

FIGURE 3.

ILK inhibitor QLT-0267 inhibits LPS-induced NF-κB-Luc activation and LPS-induced TNF-α transcription in RAW264.7 cells. A, RAW264.7 cells were transfected with plasmids containing NF-κB-Luc reporter (40 ng) and Renilla-Luc (5 ng). 18 h after transfection, cells were left untreated or treated with QLT-0267 (1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 μm) or vehicle (DMSO) for 1 h, followed by LPS treatment for 6 h. B, RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with QLT-0267 (5, 10 μm) followed by LPS treatment for 2 h. mRNAs were extracted, and TNF-α and GAPDH mRNA expressions were measured by real time PCR as described under “Experimental Procedures.” TNF-α mRNA expression was normalized against GAPDH. Data are representative of three different experiments. p values were calculated by two-tailed t test and were relative to LPS stimulation alone: *, 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05; ***, p ≤ 0.001; NT, not treated.

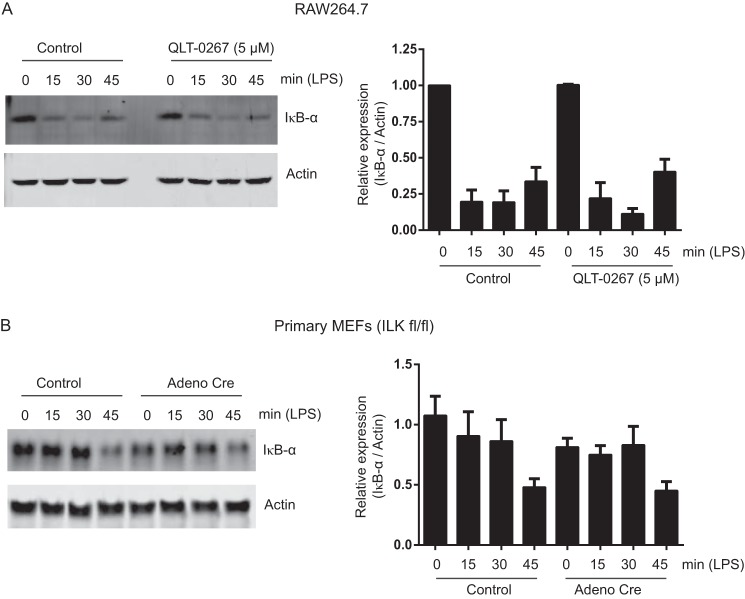

ILK Does Not Affect Classical NF-κB Pathway

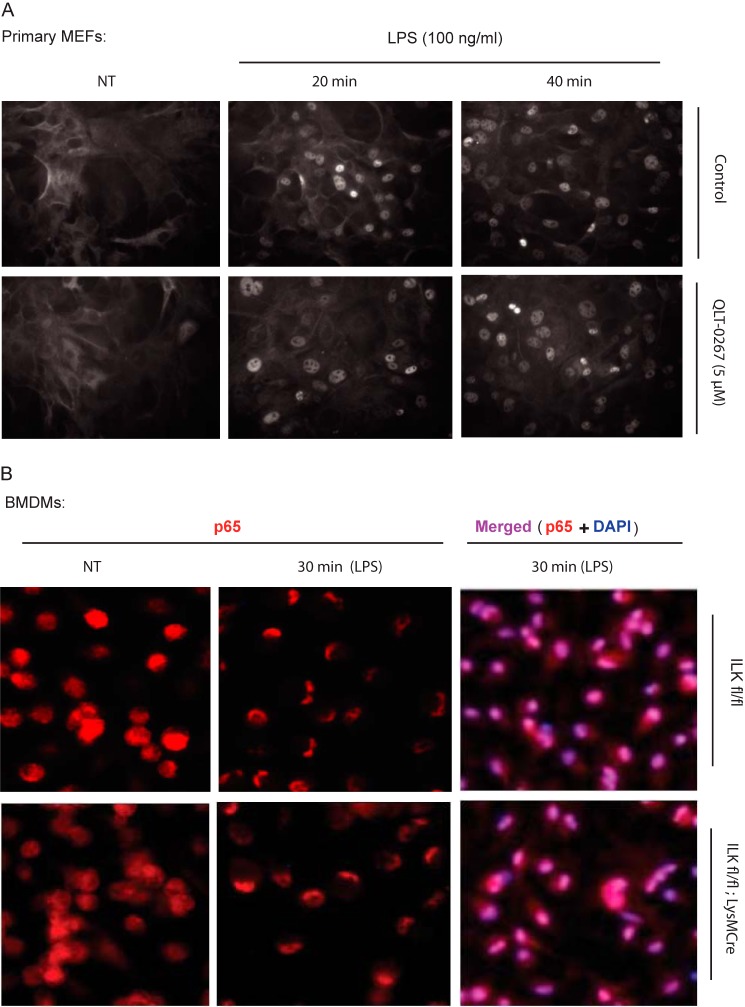

The classical NF-κB activation pathway is initiated by IκB-α phosphorylation and degradation, facilitating nuclear translocation of NF-κB complex p65-p50. Therefore, we examined the effect of ILK inhibition on LPS-induced IκB-α degradation and NF-κB nuclear translocation in RAW264.7 cells and ilkloxP/loxP MEFs. Pretreating RAW264.7 macrophages with a TNF-α-inhibitory concentration of QLT-0267 (see Fig. 1) had no effect on LPS-induced IκB-α degradation (Fig. 4A). Similarly, LPS-induced IκB-α degradation was unaffected in Adeno-Cre-infected, ilk-deleted MEFs, relative to uninfected or Adeno-Cre-infected WT MEF controls (Fig. 4B). These results suggested that ILK does not mediate nuclear translocation of p65 during NF-κB activation. To test this, we stimulated primary MEF cultures with LPS for 0, 20, or 40 min, with and without pretreatment with 5 μm QLT-0267. As shown in Fig. 5A, nuclear translocation of p65 was unaffected by 5 μm QLT-0267 at a concentration that inhibits LPS-induced TNF-α production by about 50% (see Fig. 1). Similarly, we treated both ilkloxP/loxP and ilkloxP/loxP;LysMCre BMDMs with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 30 min. LPS-induced p65 nuclear translocation was normal in both ilkloxP/loxP and ilkloxP/loxP;LysMCre (ILK-deficient, see Fig. 2) BMDMs (Fig. 5B). Collectively, these results show that ILK does not mediate NF-κB signaling via LPS-induced IκB-α degradation or p65 nuclear translocation.

FIGURE 4.

ILK is not required for LPS-induced IκB-α degradation during NF-κB activation. A, left panel, representative Western blot analysis showing IκB-α degradation in RAW264.7 cells treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 15, 30, and 45 min with or without pretreatment with QLT-0267 (5 μm). Right panel, densitometric analysis showing the differences in Iκβ-α protein bands against actin in RAW264.7 cells over more than three different experiments. B, left panel, representative Western blot analysis showing LPS-induced IκB-α degradation in ILKfl/fl primary MEFs infected with or without Adeno-Cre virus as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Right panel, a densitometric analysis showing the differences in IκB-α protein bands against actin in ILKfl/fl primary MEFs over more than three different experiments.

FIGURE 5.

ILK is not required for LPS-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65. A, WT primary MEFs were grown overnight on coverslips in 24-well plates and left untreated or treated with QLT-0267 (5 μm) for 1 h followed by LPS (100 ng/ml) treatment for 20 and 40 min. Cells were immediately fixed and processed for immunostaining NF-κB p65 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, primary BMDMs (ILKfl/fl and ILKfl/fl;LysMCre) were extracted and differentiated into macrophages ex vivo as described under “Experimental Procedures” and were treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 30 min. Cells were immediately fixed and processed for immunostaining NF-κB p65 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” NT, not treated.

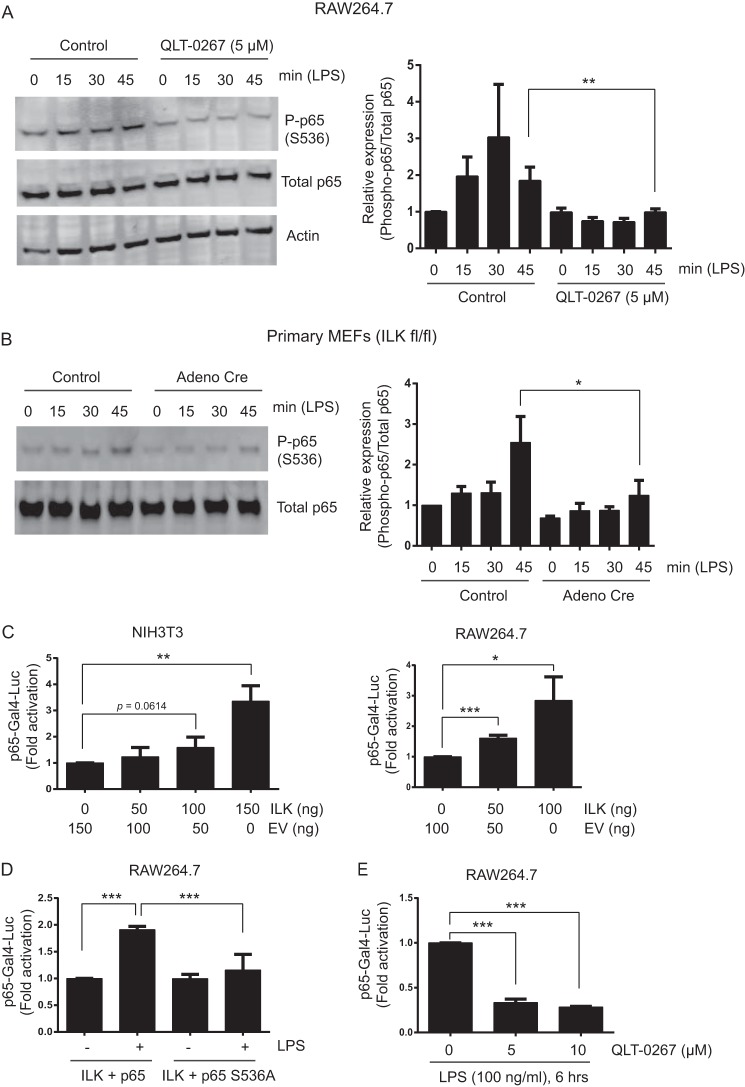

ILK Mediates Activating Phosphorylation of p65 on Ser-536

The inhibition of NF-κB luciferase activity by QLT-0267 and the lack of a role of ILK in Iκβ-α degradation and p65 nuclear translocation in response to LPS suggested a role for ILK in an alternative NF-κB activation pathway. Because LPS stimulates p65 phosphorylation at Ser-536, which is essential for NF-κB transcriptional activity, and recent findings have demonstrated p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation as an alternative to classical NF-κB activation (15–19), we investigated whether ILK played any potential role in the regulation of LPS-induced phosphorylation of p65 at Ser-536. LPS-induced Ser-536 phosphorylation of p65 was inhibited in RAW264.7 cells treated with QLT-0267 (Fig. 6A). This inhibitory role of QLT-0267 on p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation correlates with its effects on LPS-induced NF-κB luciferase activity and TNF-α secretion in RAW264.7 cells. Similarly, Cre-mediated ILK deletion in ilkfl/fl MEFs demonstrates that LPS-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation was inhibited by ILK deficiency (Fig. 6B). These results suggest a role of ILK on the p65-mediated transactivation pathway of NF-κB. To address this, we utilized a p65-Gal4 trans-reporting system (48, 49). Briefly, this assay employs a plasmid encoding the transactivation domain of p65 encompassing Ser-536, fused to the DNA-binding domain of Gal4. This plasmid, when co-transfected with a Gal4-responsive reporter Gal4-Luc, is used as a reporter system to monitor luciferase activity in response to p65 transactivation. As shown in Fig. 6C, overexpression of ILK modulates p65 transactivation in a dose-dependent manner in NIH3T3 and RAW264.7 cells. To examine the effect of ILK on p65 transactivation through Ser-536 phosphorylation, the p65(S536A)-Gal4 mutant was utilized in which serine 536 is mutated to alanine. When co-transfected in RAW264.7 cells along with ILK, cells expressing p65(S536A)-Gal4 showed little or no effect of LPS on p65 transactivation function compared with cells expressing p65-Gal4 (Fig. 6D). In accordance with our finding showing an inhibitory effect of QLT-0267 on LPS-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation, LPS-induced p65-Gal4 transactivation function was inhibited by QLT-0267 treatment in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 6E). Collectively, these results demonstrate that ILK modulates LPS-induced p65 transactivation function by regulating phosphorylation at Ser-536.

FIGURE 6.

ILK regulates LPS-induced NF-κB p65 phosphorylation at Ser-536. A, left panel, representative Western blot analysis showing phospho-p65 (Ser-536), total p65, and actin in RAW264.7 cells treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 15, 30, and 45 min following (or without) QLT-0267 (5 μm) treatment. Right panel, densitometric analysis showing the differences in phospho-p65 (Ser-536) protein bands against total p65 in RAW264.7 cells over more than three different experiments. B, left panel, representative Western blot analysis showing phospho-p65 (Ser-536) and total p65 in primary ILKfl/fl MEFs treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 15, 30, and 45 min following (or without) Adeno-Cre virus infection, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Right, densitometric analysis showing the differences in phospho-p65 (Ser-536) protein bands against total p65 in primary ILKfl/fl MEFs over more than three different experiments. C, NIH3T3 (left) and RAW264.7 (right) cells were transfected with plasmids containing p65-Gal4 (20 ng), Gal4-Luc (20 ng), Renilla luciferase (40 ng), and ILK expression vector along with empty vector (EV) (as indicated). 24 h after transfection, cells were harvested, and luciferase activity was measured as described under “Experimental Procedures.” D, RAW264.7 cells were transfected with plasmids containing p65-Gal4 or p65 S536A-Gal4 (20 ng), Gal4-Luc (20 ng), Renilla luciferase (40 ng), and ILK (100 ng). 18 h after transfection, cells were either left untreated or treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 6 h, and luciferase activity was measured. E, RAW264.7 cells were transfected with plasmids containing p65-Gal4 (20 ng), Gal4-Luc (20 ng), and Renilla luciferase (40 ng). 18 h after transfection, cells were either left untreated or treated with QLT-0267 (5 and 10 μm) for 1 h followed by LPS (100 ng/ml) for 6 h, and luciferase activity was measured. Data are representative of three different experiments. p values were calculated by two-tailed t test: *, 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05; **, 0.001 < p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001.

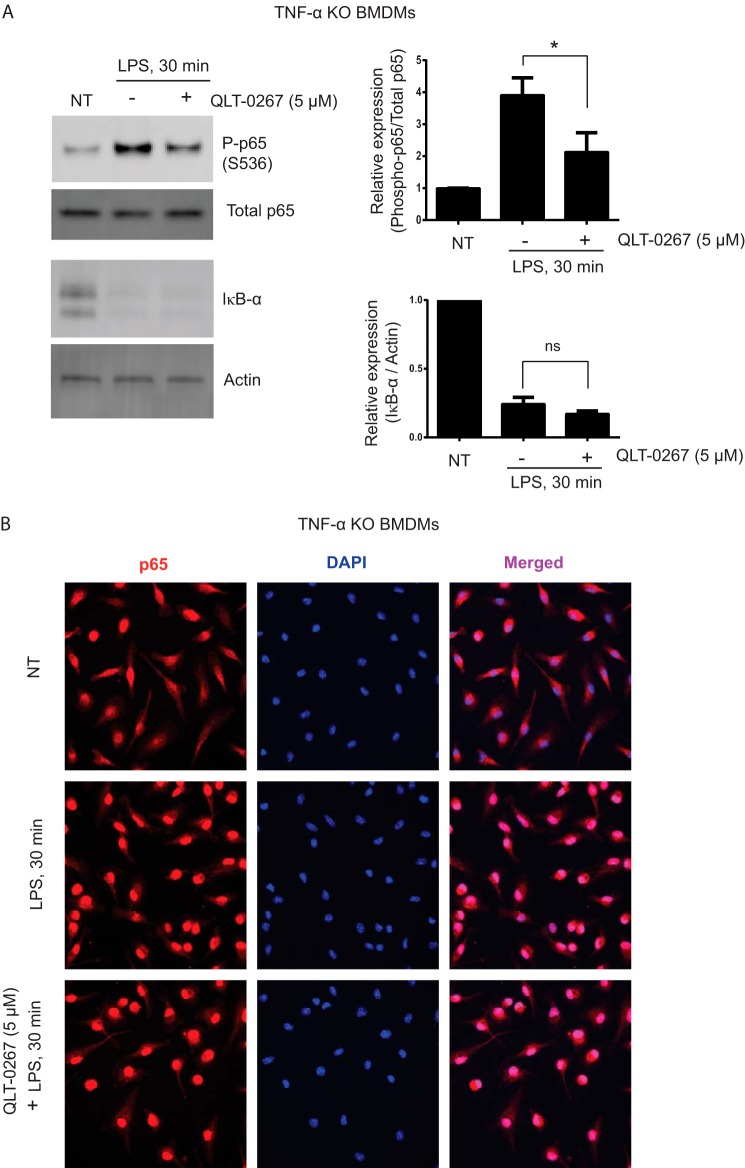

ILK-mediated Phosphorylation of p65 Ser-536 during LPS Stimulation Is Not Regulated by TNF-α

Because LPS stimulation induces TNF-α secretion and TNF-α is known to induce both NF-κB activation and p65 phosphorylation (23), we investigated whether TNF-α is a contributing factor in ILK-mediated p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation in response to LPS. To address this, we utilized BMDMs isolated from TNF-α KO mice. As shown in Fig. 7A, LPS stimulation causes a strong induction of p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation in TNF-α KO BMDMs, which is significantly reduced by QLT-0267 pretreatment. The inhibitory effect of QLT-0267 on LPS-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation in TNF-α KO BMDMs suggests that the ILK-mediated role in LPS-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation is not regulated by TNF-α. Consistent with our observations in RAW264.7 and MEFs (Figs. 4 and 5), both LPS-induced IκB-α degradation and p65 nuclear translocation remain unaffected in TNF-α KO BMDMs by QLT-0267 pretreatment (Fig. 7, A and B), suggesting that the lack of a role for ILK in classical NF-κB activation is consistent throughout cell types.

FIGURE 7.

TNF-α is not required for ILK-mediated NF-κB p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation and ILK-independent IκB-α degradation and p65 nuclear translocation in response to LPS. A, left panel, representative Western blot analyses showing phospho-p65 (Ser-536), total p65, IκB-α, and actin in TNF-α KO BMDMs untreated and treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 30 min with or without QLT-0267 (5 μm) pretreatment. Right panel, densitometric analyses showing the differences in phospho-p65 (Ser-536) protein bands against total p65 and Iκβ-α protein bands against actin in TNF-α KO BMDMs over three different experiments. B, TNF-α KO BMDMs were grown overnight on coverslips in 24-well plates and left untreated or treated with QLT-0267 (5 μm) for 1 h followed by LPS (100 ng/ml) treatment for 30 min. Cells were immediately fixed and processed for immunostaining of NF-κB p65 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” p values were calculated by two-tailed t test: *, 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05; NT, not treated.

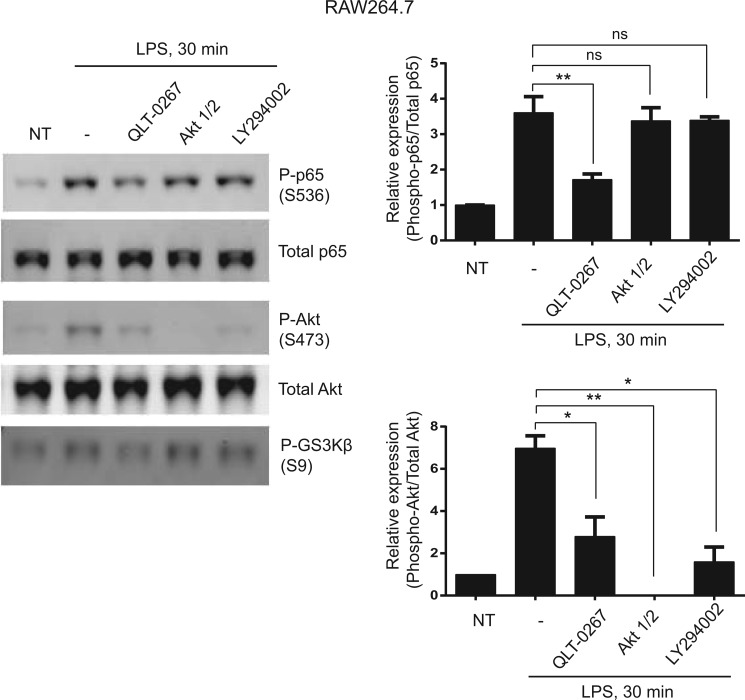

ILK-mediated Phosphorylation of p65 Ser-536 during LPS Stimulation Is a PI3K/Akt-independent Process

ILK has been shown to be an upstream regulator of the phosphorylation of Akt at Ser-473, an integral component of the PI3K pathway. By mediating phosphorylation of Akt at Ser-473, ILK regulates PI3K signaling governing cell survival, proliferation, and growth of cancer cells. Because Akt is involved in the regulation of NF-κB activation, we determined whether ILK mediates phosphorylation of p65 at Ser-536 through the PI3K/Akt pathway. The results (Fig. 8) show that LPS-induced phosphorylation of p65 at Ser-536 in RAW264.7 macrophages was significantly inhibited by ILK inhibitor QLT-0267 treatment, whereas both Akt inhibitor (Akt1/2 kinase inhibitor) and PI3K inhibitor (LY294002) have no effect. Even though QLT-0267 inhibited LPS-induced Akt phosphorylation at Ser-473 in RAW264.7 macrophages, Akt phosphorylation seems to be dispensable for LPS-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation. Thus, our results demonstrate that the kinase activity of ILK is required for LPS-induced phosphorylation of p65 at Ser-536, as QLT-0267 inhibits not only p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation but also GSK3β Ser-9 phosphorylation, which is known to be regulated by the kinase activity of ILK (36). Overall, these results suggest that, during LPS stimulation, ILK-mediated phosphorylation of p65 at Ser-536 is a PI3K/Akt-independent process.

FIGURE 8.

ILK-mediated phosphorylation of p65 at Ser-536 in response to LPS is a PI3K/Akt-independent process. Left panel, representative Western blot showing phospho-p65 (Ser-536), total p65, phospho-Akt (Ser-473), total Akt, and phospho-GSK3β (Ser-9) in RAW264.7 cells that were pretreated with QLT-0267 (10 μm), Akt1/2 kinase inhibitor (10 μm), and LY294002 (10 μm) followed by LPS (100 ng/ml) treatment for 30 min. Right panel, densitometric analyses showing the differences in either phospho-p65 (Ser-536) protein bands against total p65 or phospho-Akt (Ser-473) protein bands against total Akt in RAW264.7 cells over more than three different experiments. Data are representative of three different experiments. p values were calculated by two-tailed t test: *, 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05; **, 0.001 < p ≤ 0.01; NT, not treated.

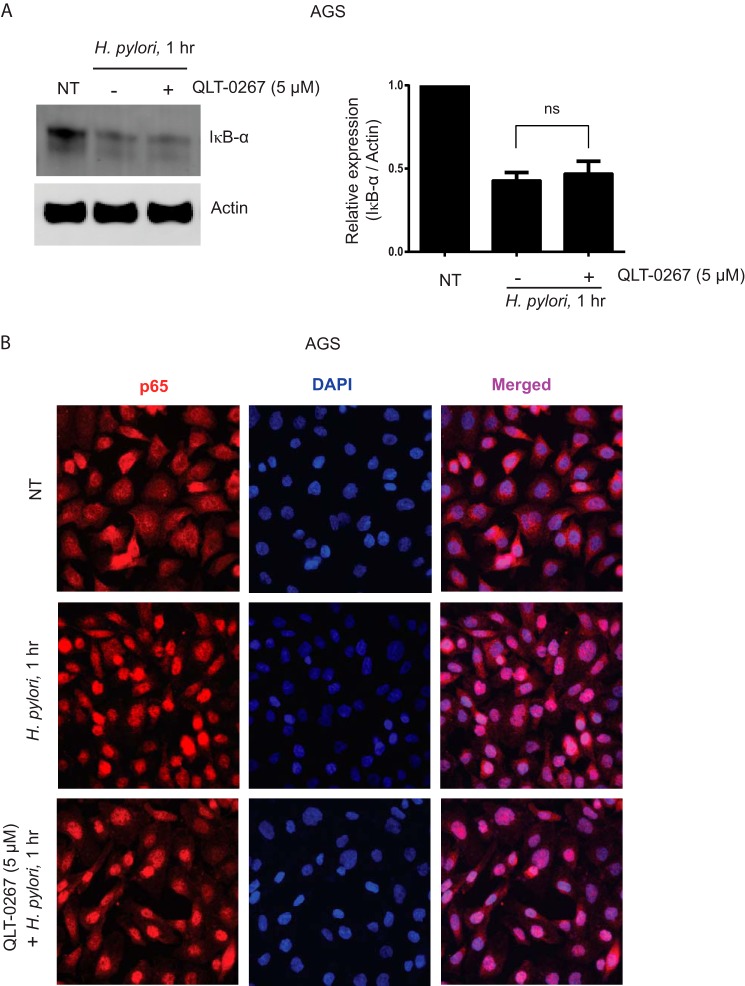

ILK Is Not Involved in H. pylori-induced IκB-α Degradation and p65 Nuclear Translocation

Based on our findings demonstrating a role for ILK in NF-κB activation, p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation, and TNF-α production, we were prompted to ask whether the ILK-mediated phenomenon mentioned above also exist in a host-pathogen interaction model using bacterial infection. To address this question, we focused on H. pylori infection in gastric cancer cells. H. pylori is a spiral-shaped and Gram-negative bacterium, which infects about 50% of the world's population and attaches to the gastric epithelium in the human stomach. H. pylori is the most prevalent cause of chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer worldwide, and ∼75% of all gastric cancer cases globally are directly associated with H. pylori infection. H. pylori infection results in the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α through NF-κB activation (50, 51). To address the question of whether ILK is involved in H. pylori-induced NF-κB activation, we carried out H. pylori infection in gastric cancer cell line AGS with and without QLT-0267 pretreatment. As shown in Fig. 9, A and B, H. pylori induces both IκB-α degradation and p65 nuclear translocation in AGS cells, and QLT-0267 pretreatment has no effect on them. Like LPS stimulation, our results demonstrate that ILK is not required for IκB-α degradation and p65 nuclear translocation in response to H. pylori infection.

FIGURE 9.

ILK is not required for H. pylori-induced IκB-α degradation and p65 nuclear translocation. A, left panel, representative Western blot analysis showing IκB-α and actin loading control in gastric cancer cell line AGS cells, either left untreated or treated with QLT-0267 (5 μm) followed by H. pylori infection at m.o.i. = 10 for 1 h. Right panel, densitometric analysis shows the differences in IκB-α bands against actin in AGS cells over three different experiments. B, AGS cells were grown overnight on coverslips in 24-well plates and left untreated or treated with QLT-0267 (5 μm) for 1 h followed by H. pylori infection at m.o.i. = 10 for 1 h. Cells were immediately fixed and processed for immunostaining of NF-κB p65 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” NT, not treated.

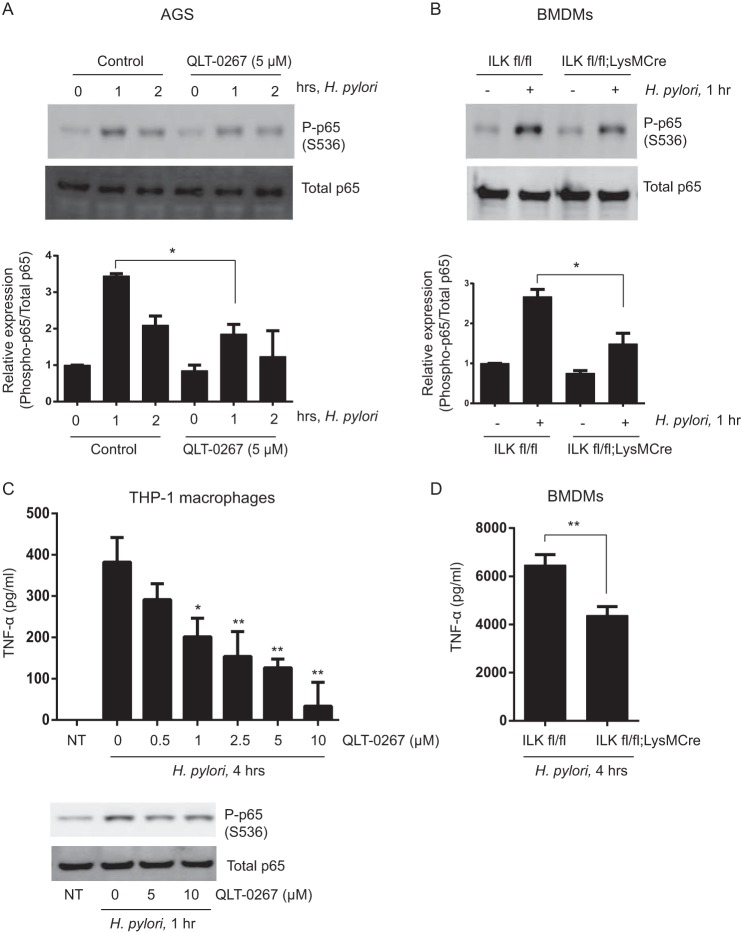

ILK Modulates H. pylori-induced Phosphorylation of p65 Ser-536 and TNF-α Secretion

Because H. pylori infection has been shown to induce phosphorylation of p65 in gastric epithelial cells (52), we were prompted to investigate whether ILK is required for H. pylori-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation and TNF-α production in infected cells. As shown in Fig. 10A, QLT-0267 pretreatment in gastric cancer AGS cells resulted in a significant reduction in H. pylori-induced phosphorylation of p65 at Ser-536. Similarly, Cre-mediated genetic knockdown of ILK in BMDMs (ilkfl/fl;LysMCre) was also associated with significantly less phosphorylation of p65 Ser-536 in response to H. pylori infection (Fig. 10B). Furthermore, QLT-0267 inhibited H. pylori-induced TNF-α secretion in THP-1 macrophages in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 10C). Genetic deletion of ILK in BMDMs (ilkfl/fl;LysMCre) was also associated with reduced TNF-α production in response to H. pylori infection relative to controls (Fig. 10D). Collectively, these results implicate ILK in H. pylori-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation and TNF-α production.

FIGURE 10.

ILK mediates H. pylori-induced p65 phosphorylation at Ser-536 and TNF-α production. A, representative Western blot showing phospho-p65 (Ser-536) and total p65 in gastric cancer cell line AGS cells pretreated with or without QLT-0267 (10 μm) followed by H. pylori infection at m.o.i. = 10 for 1 or 2 h. A densitometric analysis below shows the differences in phospho-p65 (Ser-536) protein bands against total p65 in AGS cells over three different experiments. B, representative Western blot showing phospho-p65 (Ser-536) and total p65 BMDMs (ILKfl/fl and ILKfl/fl;LysMCre) infected with H. pylori at m.o.i. = 10 for 1 or 2 h. A densitometric analysis below shows the differences in phospho-p65 (Ser-536) protein bands against total p65 in BMDMs over three different experiments. C, TNF-α production in the supernatants of THP-1 macrophages pretreated with QLT-0267 (0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, and 10 μm) followed by H. pylori infection at m.o.i. = 10 for 4 h. A representative Western blot below shows phospho-p65 (Ser-536) and total p65 in THP-1 macrophages pretreated with QLT-0267 (5 and 10 μm) followed by H. pylori infection at m.o.i. = 10 for 1 h. D, TNF-α production in the supernatants of BMDMs (ILKfl/fl and ILKfl/fl;LysMCre) infected with H. pylori at m.o.i. = 10 for 4 h. Data are representative of three different experiments. p values were calculated by two-tailed t test: *, 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05; **, 0.001 < p ≤ 0.01; NT, not treated.

ILK Modulates H. pylori-induced Phosphorylation of p65 Ser-536 through the PI3K/Akt Pathway

Because our findings demonstrate that ILK-mediated phosphorylation of p65 at Ser-536 in response to LPS is a PI3K/Akt-independent process, we investigated whether the role of ILK in H. pylori-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation is dependent on the PI3K/Akt pathway. To test this hypothesis, the effect of Akt (Akt1/2 kinase inhibitor) and PI3K (LY294002) inhibitors was assessed on H. pylori-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation in AGS cells. As shown in Fig. 11A, pretreatment with QLT-0267 or Akt1/2 kinase inhibitor significantly reduced H. pylori-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation in AGS cells. Even though H. pylori-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation was not significantly affected by the PI3K inhibitor LY294002, our observation suggests that ILK may regulate H. pylori-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation by activating Akt. To address this, AGS cells were transfected with WT and a dominant-negative variant of ILK, ILKR211A, containing a point mutation in the pleckstrin homology-like domain. Through the pleckstrin homology-like domain, ILK interacts with phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate synthesized by the PI3K pathway, thereby facilitating the activation of Akt. Consequently, ILKR211A is insensitive to phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate activation upon PI3K activation (53, 54). ILKWT and ILKR211A cDNAs were cloned into mCherry expression vectors for transfection into AGS cells. Achieving 60–70% transfection efficiency in these cells, we observed around 50% reduction in H. pylori-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation in ILKR211A-transfected cells, relative to ILKWT controls (Fig. 11B). The effect of ILKR211A on PI3K/Akt activation was also verified by demonstration that H. pylori-induced Akt Ser-473 phosphorylation was also significantly reduced in ILKR211A-transfected cells compared with that in ILKWT-transfected cells (Fig. 11C). Moreover, the differences in Akt Ser-473 phosphorylation between ILKWT- and ILKR211A-transfected cells were also similar to those in p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation in response to H. pylori infection. Overall, these results suggest that ILK modulates H. pylori-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation through the PI3K/Akt pathway.

FIGURE 11.

ILK mediates H. pylori-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation through PI3K/Akt pathway. A, left panel, representative Western blot showing phospho-p65 (Ser-536), total p65, phospho-Akt (Ser-473), and total Akt in AGS cells that were pretreated with QLT-0267 (10 μm), Akt1/2 kinase inhibitor (10 μm), and LY294002 (10 μm) followed by H. pylori infection at m.o.i. = 10 for 1 h. Right panel, densitometric analyses showing the differences in phospho-p65 (Ser-536) protein bands against total p65 and phospho-Akt (Ser-473) protein bands against total Akt in AGS cells in response to H. pylori infection over more than three different experiments. B, representative Western blot showing phospho-p65 (Ser-536) and total p65 in AGS cells transfected with either WT ILK or ILK R211A followed by H. pylori infection at m.o.i. = 10 for 1, 2, and 4 h. A densitometric analysis below shows the differences in phospho-p65 (Ser-536) protein bands against total p65 in AGS cells in response to H. pylori infection over three different experiments. C, representative Western blot showing phospho-Akt (Ser-473) and total Akt in AGS cells transfected with either WT ILK or ILK R211A followed by H. pylori infection at m.o.i. = 10 for 1 h. A densitometric analysis below shows the differences in phospho-Akt (Ser-473) protein bands against total Akt in AGS cells in response to H. pylori infection over three different experiments. p values were calculated by two-tailed t test: *, 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05; **, 0.001 < p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001; NT, not treated; ns, not significant.

DISCUSSION

Among the TLRs, TLR4 was the first to be described as the key sensor for microbial products (55), and the importance of TLR4 has drawn immense attention because it has been known as the prime receptor involved in LPS-induced sepsis. The emerging evidence has suggested that the regulation of TLR4 signaling is far more complex than originally thought. In addition to the existence of different adaptor proteins leading to diverse signaling cascades, the TLR4 signaling pathway is also subject to additional layers of regulation. In resting cells, TLR4 cycles between the Golgi and the plasma membrane. TLR4 in the plasma membrane activates early responses (MyD88-dependent) to LPS (56, 57). Following LPS stimulation, TLR4 is also subject to ubiquitination and tyrosine phosphorylation, which triggers translocation of TLR4 from the plasma membrane to lysosomes for degradation to prevent its prolonged activation (58). LPS stimulation also triggers maturation and trafficking of TLR4 from the Golgi to the plasma membrane, processes that are regulated by chaperones such as gp96 and PRAT4A (59, 60). The association between TLR4 and chaperones can only take place under certain calcium concentrations in the endoplasmic reticulum, suggesting the endoplasmic reticulum calcium signaling as a critical regulator for TLR4 activation (59). Despite all the evidence on the regulation of TLR4 signaling, the exact molecular mechanisms underlying the LPS-induced signal transduction and the control of gene expression have not been completely elucidated.

Integrins, a family of heterotrimeric transmembrane receptors that link the extracellular matrix to intracellular signaling molecules for the regulation of a number of cellular processes, have recently been implicated in the regulation of TLR signaling. An inhibitory effect of β1 integrin on TLR (including TLR4)-triggered inflammatory responses has clearly been demonstrated (61–63). Conversely, several studies have also revealed a positive role of integrins in the activation of NF-κB and pro-inflammatory pathways (64–66). Despite the significant influence on TLR signaling, the exact molecular mechanism underlying an integrin-mediated role remains largely unknown. The extracellular matrix-integrin contacts induce the formation of multiprotein structures called focal adhesion points. ILK, which directly interacts with the cytoplasmic subunits of β1 and β3 integrins, is involved in focal adhesions and, being regulated in a PI3K-dependent manner, can regulate the integrin-stimulated phosphorylation and activation of Akt. Therefore, ILK has been implicated in integrin-mediated gene expression through the activation of transcription factors such as NF-κB. Involvement of ILK in NF-κB activation has been suggested by different studies (29–35), via the classical NF-κB signaling pathway. However, the exact role of ILK in TLR-mediated NF-κB signaling has not been determined. In this study, using a combination of a Cre-LoxP-dependent knockdown ILK and a small molecule ILK inhibitor, we have shown that ILK is not required for LPS-induced classical NF-κB signaling involving IκB-α degradation and nuclear translocation of p65. Rather, it modulates LPS-stimulated NF-κB transcription activity through p65 phosphorylation at Ser-536. Using a reporter-based assay, we have demonstrated that ILK is required for LPS-induced transactivation of p65 through Ser-536. Interestingly, focal adhesion kinase has also been shown to be dispensable for flow-stimulated IκB-α degradation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB but essential for flow-stimulated p65 phosphorylation on Ser-536 during flow-stimulated NF-κB activation (67). Alternative activation of NF-κB via p65 Ser-536 appears to be a fully functional and integral part of the TLR signaling pathway. For instance, although IRAK-4 appears to be critical for the classical NF-κB activation pathway, IRAK-1 is selectively involved in enhancing transcriptional activity of p65 through Ser-536 phosphorylation (68).

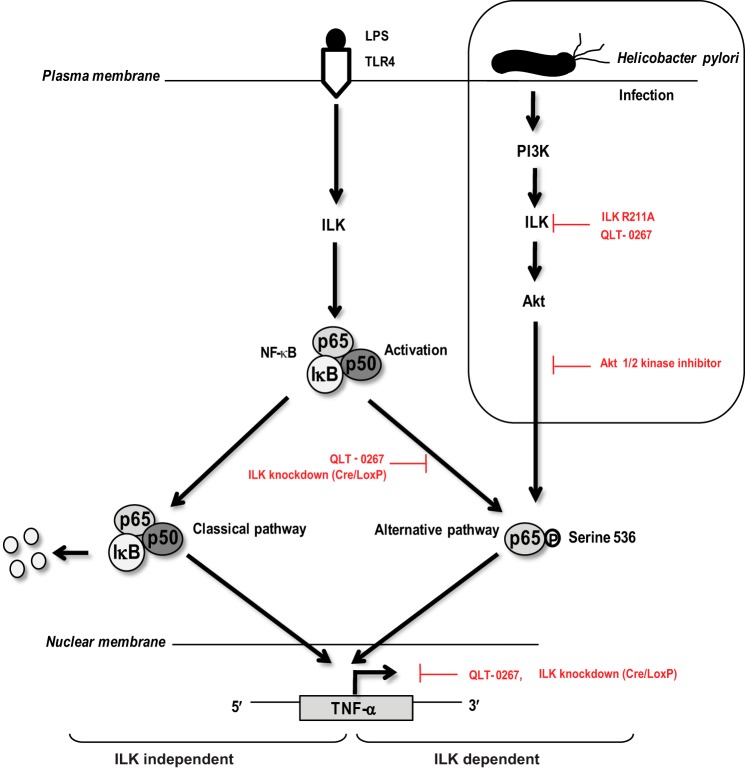

The functional relevance of our findings is evident from our observation that ILK-mediated signaling also participates in H. pylori infection in gastric epithelial cells and macrophages. The immune response to H. pylori infection is mediated by numerous signal transduction cascades resulting in the activation of NF-κB, MAPK enzyme family, and AP-1 (activator protein-1) (69). NF-κB is the key regulator of H. pylori-induced inflammatory microenvironments in the stomach, which is activated by the physical contact between H. pylori and gastric epithelial cells, and results in the induction of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-8, IL-6, and IL-1. Activated NF-κB is therefore a common feature of gastric biopsy associated with H. pylori infection (50). The major disease-associated feature of H. pylori is the presence of a pathogenicity island, which encodes proteins involved in a type IV secretion system (T4SS). Published reports have demonstrated that T4SS can induce NF-κB activation in epithelial cells through two likely mediators. First, the bacterial peptidoglycan is injected into the host cells by T4SS of H. pylori, which is recognized by the NOD1 receptor molecules leading to NF-κB activation (70). Second, the effector protein cytotoxin-associated gene product A can activate NF-κB after being translocated into the host cells by T4SS and tyrosine-phosphorylated by Src family kinases (71). However, a complete mechanism of H. pylori-induced NF-κB activation through T4SS has yet to be revealed. Alternatively, the involvement of TLRs in H. pylori-induced NF-κB activation cannot be ignored, because the recognition of H. pylori by TLR2 and TLR5 followed by NF-κB activation in epithelial cells has also been demonstrated (69). A potential involvement of H. pylori LPS in gastric inflammation is also highlighted by studies showing that H. pylori LPS alone can cause gastric mucosal responses similar to those observed in acute gastritis, as well as its critical role in enhancing TNF-α production, which is associated with gastric mucosal inflammatory responses (72, 73). A gene product of H. pylori, TNF-α-inducing protein (Tipα), has also been shown to be a key mediator of TNF-α gene expression in host cells through NF-κB activation (50). Last but not least, it has been demonstrated that the integrin receptor and focal adhesion kinase activation are instrumental for the delivery of cytotoxin-associated gene product A into host cells by T4SS of H. pylori and the phosphorylation of cytotoxin-associated gene product A by Src, respectively (74), indicating a role of integrin-mediated signal transduction during H. pylori infection. Our results indicate a novel role for ILK in H. pylori-induced NF-κB p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation and TNF-α production. Like LPS stimulation, ILK is not required for IκB-α degradation and p65 nuclear translocation in response to H. pylori infection. We have shown that ILK regulates p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation in both PI3K/Akt-independent and -dependent manners in response to LPS stimulation and H. pylori infection, respectively (see proposed model, Fig. 12). Even though QLT-0267 has been shown to also inhibit FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) (47), we have used both QLT-0267 and genetic knockdown to alter ILK expression to draw the major conclusion of our work illustrating an ILK-mediated role in NF-κB p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation and TNF-α production in response to both LPS and H. pylori infection. Our observations suggest a conserved role for ILK in NF-κB activation and innate immune responses across diverse signaling pathways.

FIGURE 12.

Schematic representation of ILK-mediated signaling events in LPS- and H. pylori-induced NF-κB p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation. A model of the role of ILK in p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation during NF-κB activation in innate immune responses to LPS stimulation and H. pylori infection is shown. LPS stimulates ILK kinase activity, which is required for NF-κB activation. The nature of ILK activation by LPS is currently unknown. ILK mediates NF-κB activation through p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation, but it is not required for classical activation of NF-κB, which is initiated by Iκβ-α degradation and nuclear translocation of p65. Phosphorylation of p65 Ser-536 by ILK in response to LPS is a PI3K/Akt-independent process. H. pylori-induced p65 Ser-536 phosphorylation is also mediated by ILK, but in a PI3K/Akt-dependent manner. Based on both pharmacological inhibition (using QLT-0267) and Cre-mediated genetic knockdown of ILK, our results suggest that NF-κB activation can be categorized as ILK-independent (classical activation) and ILK-dependent (p65 transactivation through Ser-536).

Based on the published reports, it is well known that the roles of the signaling molecules involved in focal adhesion are diverse and go well beyond the need for only cellular adhesion. As recent studies have started to uncover the influence of integrins in TLR responses, it would also be interesting to understand the cross-talk between cellular adhesions and TLR signaling at the molecular level. Our data demonstrate a novel function of the focal adhesion protein ILK in TLR-induced NF-κB signaling and highlight a therapeutic potential for this molecule in inflammatory diseases. Future investigations will be required to determine whether the involvement of ILK in TLR signaling is an integrin-dependent or -independent process. Because the overexpression of ILK is a common feature of a wide range of human cancers, it would be important to understand the detailed molecular mechanism underlying how ILK promotes inflammation and cancer. As ILK is a druggable target, future pre-clinical investigations can potentially address ILK as a therapeutic target to treat inflammation and cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jonathan Ferrand and Lorinda Turner (Centre for Innate Immunity and Infectious Diseases, MIMR-PHI Institute of Medical Research, Clayton, Victoria, Australia) for providing Helicobacter pylori bacterial cultures.

This work was supported in part by the Operational Infrastructure Support Program of the Government of Victoria.

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor κB

- IKK

- IκB kinase

- ILK

- integrin-linked kinase

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- BMDM

- bone marrow-derived macrophage

- Adeno-Cre

- adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase

- T4SS

- type IV secretion system

- m.o.i.

- multiplicity of infection.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pålsson-McDermott E. M., O'Neill L. A. (2004) Signal transduction by the lipopolysaccharide receptor, Toll-like receptor-4. Immunology 113, 153–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ulevitch R. J., Tobias P. S. (1995) Receptor-dependent mechanisms of cell stimulation by bacterial endotoxin. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 13, 437–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laskin D. L., Pendino K. J. (1995) Macrophages and inflammatory mediators in tissue injury. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 35, 655–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beutler B., Cerami A. (1989) The biology of cachectin/TNF–a primary mediator of the host response. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 7, 625–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sandborn W. J., Hanauer S. B. (1999) Antitumor necrosis factor therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a review of agents, pharmacology, clinical results, and safety. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 5, 119–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gilmore T. D., Wolenski F. S. (2012) NF-κB: where did it come from and why? Immunol. Rev. 246, 14–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kanarek N., Ben-Neriah Y. (2012) Regulation of NF-κB by ubiquitination and degradation of the IκBs. Immunol. Rev. 246, 77–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sun S. C. (2012) The noncanonical NF-κB pathway. Immunol. Rev. 246, 125–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ashburner B. P., Westerheide S. D., Baldwin A. S., Jr. (2001) The p65 (RelA) subunit of NF-κB interacts with the histone deacetylase (HDAC) corepressors HDAC1 and HDAC2 to negatively regulate gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 7065–7077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen Lf., Fischle W., Verdin E., Greene W. C. (2001) Duration of nuclear NF-κB action regulated by reversible acetylation. Science 293, 1653–1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marshall H. E., Hess D. T., Stamler J. S. (2004) S-Nitrosylation: physiological regulation of NF-κB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 8841–8842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marshall H. E., Stamler J. S. (2002) Nitrosative stress-induced apoptosis through inhibition of NF-κB. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34223–34228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dai Y., Chen S., Wang L., Pei X. Y., Funk V. L., Kramer L. B., Dent P., Grant S. (2011) Disruption of IκB kinase (IKK)-mediated RelA serine 536 phosphorylation sensitizes human multiple myeloma cells to histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 34036–34050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Neumann M., Naumann M. (2007) Beyond IκBs: alternative regulation of NF-κB activity. FASEB J. 21, 2642–2654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Douillette A., Bibeau-Poirier A., Gravel S. P., Clément J. F., Chénard V., Moreau P., Servant M. J. (2006) The proinflammatory actions of angiotensin II are dependent on p65 phosphorylation by the IκB kinase complex. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 13275–13284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mandrekar P., Jeliazkova V., Catalano D., Szabo G. (2007) Acute alcohol exposure exerts anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting IκB kinase activity and p65 phosphorylation in human monocytes. J. Immunol. 178, 7686–7693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nicholas C., Batra S., Vargo M. A., Voss O. H., Gavrilin M. A., Wewers M. D., Guttridge D. C., Grotewold E., Doseff A. I. (2007) Apigenin blocks lipopolysaccharide-induced lethality in vivo and proinflammatory cytokines expression by inactivating NF-κB through the suppression of p65 phosphorylation. J. Immunol. 179, 7121–7127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sasaki C. Y., Barberi T. J., Ghosh P., Longo D. L. (2005) Phosphorylation of RelA/p65 on serine 536 defines an IκBα-independent NF-κB pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34538–34547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang F., Tang E., Guan K., Wang C. Y. (2003) IKKβ plays an essential role in the phosphorylation of RelA/p65 on serine 536 induced by lipopolysaccharide. J. Immunol. 170, 5630–5635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ghosh C. C., Ramaswami S., Juvekar A., Vu H. Y., Galdieri L., Davidson D., Vancurova I. (2010) Gene-specific repression of proinflammatory cytokines in stimulated human macrophages by nuclear IκBα. J. Immunol. 185, 3685–3693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gutierrez H., O'Keeffe G. W., Gavaldà N., Gallagher D., Davies A. M. (2008) Nuclear factor κB signaling either stimulates or inhibits neurite growth depending on the phosphorylation status of p65/RelA. J. Neurosci. 28, 8246–8256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adli M., Baldwin A. S. (2006) IKK-ι/IKKϵ controls constitutive, cancer cell-associated NF-κB activity via regulation of Ser-536 p65/RelA phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 26976–26984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sakurai H., Chiba H., Miyoshi H., Sugita T., Toriumi W. (1999) IκB kinases phosphorylate NF-κB p65 subunit on serine 536 in the transactivation domain. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30353–30356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hannigan G. E., Leung-Hagesteijn C., Fitz-Gibbon L., Coppolino M. G., Radeva G., Filmus J., Bell J. C., Dedhar S. (1996) Regulation of cell adhesion and anchorage-dependent growth by a new β1-integrin-linked protein kinase. Nature 379, 91–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hannigan G. E., McDonald P. C., Walsh M. P., Dedhar S. (2011) Integrin-linked kinase: not so 'pseudo' after all. Oncogene 30, 4375–4385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Legate K. R., Montañez E., Kudlacek O., Fässler R. (2006) ILK, PINCH and parvin: the tIPP of integrin signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 20–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hannigan G., Troussard A. A., Dedhar S. (2005) Integrin-linked kinase: a cancer therapeutic target unique among its ILK. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 51–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McDonald P. C., Fielding A. B., Dedhar S. (2008) Integrin-linked kinase–essential roles in physiology and cancer biology. J. Cell Sci. 121, 3121–3132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tan C., Mui A., Dedhar S. (2002) Integrin-linked kinase regulates inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 expression in an NF-κB-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 3109–3116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Makino K., Day C. P., Wang S. C., Li Y. M., Hung M. C. (2004) Upregulation of IKKα/IKKβ by integrin-linked kinase is required for HER2/neu-induced NF-κB antiapoptotic pathway. Oncogene 23, 3883–3887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Agouni A., Sourbier C., Danilin S., Rothhut S., Lindner V., Jacqmin D., Helwig J. J., Lang H., Massfelder T. (2007) Parathyroid hormone-related protein induces cell survival in human renal cell carcinoma through the PI3K Akt pathway: evidence for a critical role for integrin-linked kinase and nuclear factor κB. Carcinogenesis 28, 1893–1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Medici D., Nawshad A. (2010) Type I collagen promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition through ILK-dependent activation of NF-κB and LEF-1. Matrix Biol. 29, 161–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen D., Zhang Y., Zhang X., Li J., Han B., Liu S., Wang L., Ling Y., Mao S., Wang X. (2013) Overexpression of integrin-linked kinase correlates with malignant phenotype in non-small cell lung cancer and promotes lung cancer cell invasion and migration via regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-related genes. Acta Histochem. 115, 128–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. del Nogal M., Luengo A., Olmos G., Lasa M., Rodriguez-Puyol D., Rodriguez-Puyol M., Calleros L. (2012) Balance between apoptosis or survival induced by changes in extracellular-matrix composition in human mesangial cells: a key role for ILK-NFκB pathway. Apoptosis 17, 1261–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wani A. A., Jafarnejad S. M., Zhou J., Li G. (2011) Integrin-linked kinase regulates melanoma angiogenesis by activating NF-κB/interleukin-6 signaling pathway. Oncogene 30, 2778–2788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maydan M., McDonald P. C., Sanghera J., Yan J., Rallis C., Pinchin S., Hannigan G. E., Foster L. J., Ish-Horowicz D., Walsh M. P., Dedhar S. (2010) Integrin-linked kinase is a functional Mn2+-dependent protein kinase that regulates glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) phosphorylation. PLoS One 5, e12356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Philpott D. J., Belaid D., Troubadour P., Thiberge J. M., Tankovic J., Labigne A., Ferrero R. L. (2002) Reduced activation of inflammatory responses in host cells by mouse-adapted Helicobacter pylori isolates. Cell. Microbiol. 4, 285–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Allison C. C., Kufer T. A., Kremmer E., Kaparakis M., Ferrero R. L. (2009) Helicobacter pylori induces MAPK phosphorylation and AP-1 activation via a NOD1-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 183, 8099–8109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Troussard A. A., McDonald P. C., Wederell E. D., Mawji N. M., Filipenko N. R., Gelmon K. A., Kucab J. E., Dunn S. E., Emerman J. T., Bally M. B., Dedhar S. (2006) Preferential dependence of breast cancer cells versus normal cells on integrin-linked kinase for protein kinase B/Akt activation and cell survival. Cancer Res. 66, 393–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fielding A. B., Dobreva I., McDonald P. C., Foster L. J., Dedhar S. (2008) Integrin-linked kinase localizes to the centrosome and regulates mitotic spindle organization. J. Cell Biol. 180, 681–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fielding A. B., Lim S., Montgomery K., Dobreva I., Dedhar S. (2011) A critical role of integrin-linked kinase, ch-TOG and TACC3 in centrosome clustering in cancer cells. Oncogene 30, 521–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kalra J., Anantha M., Warburton C., Waterhouse D., Yan H., Yang Y. J., Strut D., Osooly M., Masin D., Bally M. B. (2011) Validating the use of a luciferase labeled breast cancer cell line, MDA435LCC6, as a means to monitor tumor progression and to assess the therapeutic activity of an established anticancer drug, docetaxel (Dt) alone or in combination with the ILK inhibitor, QLT0267. Cancer Biol. Ther. 11, 826–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee D. F., Kuo H. P., Liu M., Chou C. K., Xia W., Du Y., Shen J., Chen C. T., Huo L., Hsu M. C., Li C. W., Ding Q., Liao T. L., Lai C. C., Lin A. C., Chang Y. H., Tsai S. F., Li L. Y., Hung M. C. (2009) KEAP1 E3 ligase-mediated down-regulation of NF-κB signaling by targeting IKKβ. Mol. Cell 36, 131–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Oloumi A., Syam S., Dedhar S. (2006) Modulation of Wnt3a-mediated nuclear β-catenin accumulation and activation by integrin-linked kinase in mammalian cells. Oncogene 25, 7747–7757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kalra J., Sutherland B. W., Stratford A. L., Dragowska W., Gelmon K. A., Dedhar S., Dunn S. E., Bally M. B. (2010) Suppression of Her2/neu expression through ILK inhibition is regulated by a pathway involving TWIST and YB-1. Oncogene 29, 6343–6356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kalra J., Warburton C., Fang K., Edwards L., Daynard T., Waterhouse D., Dragowska W., Sutherland B. W., Dedhar S., Gelmon K., Bally M. (2009) QLT0267, a small molecule inhibitor targeting integrin-linked kinase (ILK), and docetaxel can combine to produce synergistic interactions linked to enhanced cytotoxicity, reductions in P-AKT levels, altered F-actin architecture and improved treatment outcomes in an orthotopic breast cancer model. Breast Cancer Res. 11, R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Muranyi A. L., Dedhar S., Hogge D. E. (2010) Targeting integrin linked kinase and FMS-like tyrosine kinase-3 is cytotoxic to acute myeloid leukemia stem cells but spares normal progenitors. Leuk. Res. 34, 1358–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Doyle S. L., Jefferies C. A., O'Neill L. A. (2005) Bruton's tyrosine kinase is involved in p65-mediated transactivation and phosphorylation of p65 on serine 536 during NFκB activation by lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 23496–23501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Madrid L. V., Mayo M. W., Reuther J. Y., Baldwin A. S., Jr. (2001) Akt stimulates the transactivation potential of the RelA/p65 subunit of NF-κ B through utilization of the IκB kinase and activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase p38. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18934–18940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Suganuma M., Kuzuhara T., Yamaguchi K., Fujiki H. (2006) Carcinogenic role of tumor necrosis factor-α inducing protein of Helicobacter pylori in human stomach. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Suganuma M., Watanabe T., Yamaguchi K., Takahashi A., Fujiki H. (2012) Human gastric cancer development with TNF-α-inducing protein secreted from Helicobacter pylori. Cancer Lett. 322, 133–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Huang X., Lv B., Zhang S., Dai Q., Chen B. B., Meng L. N. (2013) Effects of radix curcumae-derived diterpenoid C on Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation and nuclear factor κB signal pathways. World J. Gastroenterol. 19, 5085–5093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Huang J., Mahavadi S., Sriwai W., Hu W., Murthy K. S. (2006) Gi-coupled receptors mediate phosphorylation of CPI-17 and MLC20 via preferential activation of the PI3K/ILK pathway. Biochem. J. 396, 193–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lu H., Fedak P. W., Dai X., Du C., Zhou Y. Q., Henkelman M., Mongroo P. S., Lau A., Yamabi H., Hinek A., Husain M., Hannigan G., Coles J. G. (2006) Integrin-linked kinase expression is elevated in human cardiac hypertrophy and induces hypertrophy in transgenic mice. Circulation 114, 2271–2279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Poltorak A., He X., Smirnova I., Liu M. Y., Van Huffel C., Du X., Birdwell D., Alejos E., Silva M., Galanos C., Freudenberg M., Ricciardi-Castagnoli P., Layton B., Beutler B. (1998) Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science 282, 2085–2088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kagan J. C., Su T., Horng T., Chow A., Akira S., Medzhitov R. (2008) TRAM couples endocytosis of Toll-like receptor 4 to the induction of interferon-β. Nat. Immunol. 9, 361–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tanimura N., Saitoh S., Matsumoto F., Akashi-Takamura S., Miyake K. (2008) Roles for LPS-dependent interaction and relocation of TLR4 and TRAM in TRIF-signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 368, 94–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chuang T. H., Ulevitch R. J. (2004) Triad3A, an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase regulating Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 5, 495–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Randow F., Seed B. (2001) Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone gp96 is required for innate immunity but not cell viability. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 891–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Takahashi K., Shibata T., Akashi-Takamura S., Kiyokawa T., Wakabayashi Y., Tanimura N., Kobayashi T., Matsumoto F., Fukui R., Kouro T., Nagai Y., Takatsu K., Saitoh S., Miyake K. (2007) A protein associated with Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 (PRAT4A) is required for TLR-dependent immune responses. J. Exp. Med. 204, 2963–2976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Han C., Jin J., Xu S., Liu H., Li N., Cao X. (2010) Integrin CD11b negatively regulates TLR-triggered inflammatory responses by activating Syk and promoting degradation of MyD88 and TRIF via Cbl-b. Nat. Immunol. 11, 734–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wang L., Gordon R. A., Huynh L., Su X., Park Min K. H., Han J., Arthur J. S., Kalliolias G. D., Ivashkiv L. B. (2010) Indirect inhibition of Toll-like receptor and type I interferon responses by ITAM-coupled receptors and integrins. Immunity 32, 518–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yee N. K., Hamerman J. A. (2013) β2 integrins inhibit TLR responses by regulating NF-κB pathway and p38 MAPK activation. Eur. J. Immunol. 43, 779–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kagan J. C., Medzhitov R. (2006) Phosphoinositide-mediated adaptor recruitment controls Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell 125, 943–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Medvedev A. E., Flo T., Ingalls R. R., Golenbock D. T., Teti G., Vogel S. N., Espevik T. (1998) Involvement of CD14 and complement receptors CR3 and CR4 in nuclear factor-κB activation and TNF production induced by lipopolysaccharide and group B streptococcal cell walls. J. Immunol. 160, 4535–4542 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Perera P. Y., Mayadas T. N., Takeuchi O., Akira S., Zaks-Zilberman M., Goyert S. M., Vogel S. N. (2001) CD11b/CD18 acts in concert with CD14 and Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 to elicit full lipopolysaccharide and taxol-inducible gene expression. J. Immunol. 166, 574–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Petzold T., Orr A. W., Hahn C., Jhaveri K. A., Parsons J. T., Schwartz M. A. (2009) Focal adhesion kinase modulates activation of NF-κB by flow in endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 297, C814–C822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Li L., Su J., Xie Q. (2007) Differential regulation of key signaling molecules in innate immunity and human diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 598, 49–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Smith M. F., Jr., Mitchell A., Li G., Ding S., Fitzmaurice A. M., Ryan K., Crowe S., Goldberg J. B. (2003) Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR5, but not TLR4, are required for Helicobacter pylori-induced NF-κB activation and chemokine expression by epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 32552–32560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Viala J., Chaput C., Boneca I. G., Cardona A., Girardin S. E., Moran A. P., Athman R., Mémet S., Huerre M. R., Coyle A. J., DiStefano P. S., Sansonetti P. J., Labigne A., Bertin J., Philpott D. J., Ferrero R. L. (2004) Nod1 responds to peptidoglycan delivered by the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island. Nat. Immunol. 5, 1166–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Brandt S., Kwok T., Hartig R., König W., Backert S. (2005) NF-κB activation and potentiation of proinflammatory responses by the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 9300–9305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Piotrowski J., Piotrowski E., Skrodzka D., Slomiany A., Slomiany B. L. (1997) Induction of acute gastritis and epithelial apoptosis by Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 32, 203–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Slomiany B. L., Piotrowski J., Slomiany A. (1999) Involvement of endothelin-1 in up-regulation of gastric mucosal inflammatory responses to Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 258, 17–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]