Key Points

Platelet 12-LOX modulates FcγRIIa signaling and presents a viable therapeutic target in the prevention of immune-mediated thrombosis.

This novel therapeutic approach is supported by pharmacologic inhibition and genetic ablation of 12-LOX in human and mouse platelets.

Abstract

Platelets are essential in maintaining hemostasis following inflammation or injury to the vasculature. Dysregulated platelet activity often results in thrombotic complications leading to myocardial infarction and stroke. Activation of the FcγRIIa receptor leads to immune-mediated thrombosis, which is often life threatening in patients undergoing heparin-induced thrombocytopenia or sepsis. Inhibiting FcγRIIa-mediated activation in platelets has been shown to limit thrombosis and is the principal target for prevention of immune-mediated platelet activation. In this study, we show for the first time that platelet 12(S)-lipoxygenase (12-LOX), a highly expressed oxylipin-producing enzyme in the human platelet, is an essential component of FcγRIIa-mediated thrombosis. Pharmacologic inhibition of 12-LOX in human platelets resulted in significant attenuation of FcγRIIa-mediated aggregation. Platelet 12-LOX was shown to be essential for FcγRIIa-induced phospholipase Cγ2 activity leading to activation of calcium mobilization, Rap1 and protein kinase C activation, and subsequent activation of the integrin αIIbβ3. Additionally, platelets from transgenic mice expressing human FcγRIIa but deficient in platelet 12-LOX, failed to form normal platelet aggregates and exhibited deficiencies in Rap1 and αIIbβ3 activation. These results support an essential role for 12-LOX in regulating FcγRIIa-mediated platelet function and identifies 12-LOX as a potential therapeutic target to limit immune-mediated thrombosis.

Introduction

Platelet activation is essential for maintaining normal hemostasis following vascular insult or injury.1 While formation of the platelet plug is a required step in primary hemostasis, under certain conditions, activation of platelets with the surrounding environment results in the formation of an occlusive thrombus resulting in myocardial infarction and stroke.2 One mode of platelet activation involves the platelet signaling through an immune response via immunoreceptors on the platelet surface.2-6 Human platelets express a number of receptors containing or associated with immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) containing transmembrane receptors, including glycoprotein VI (GPVI),7 C-type lectin-like receptor 2,8 and the IgG immune complex receptor, FcγRIIa.9 Ligation of ITAM-containing receptors on the platelet has been previously shown to lead to a shared downstream signaling pathway resulting in platelet activation.8,10,11 Although activation of each of these receptors contributes in distinct ways to physiological hemostasis and thrombosis,12-16 they have nonredundant pathophysiological functions. In particular, FcγRIIa, which is present on the surface of human but not mouse platelets,17 is best known for its pathophysiological role in immune-mediated thrombocytopenia and thrombosis, a family of disorders including thrombocytopenia associated with sepsis, thrombosis due to certain therapeutic monoclonal antibodies, and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT).5,18,19 Selectively inhibiting the FcγRIIa signaling pathway in platelets for prevention of immune-mediated thrombocytopenia and thrombosis has been a long sought approach for the prevention of HIT.20

Platelet 12(S)-lipoxygenase (12-LOX), an oxygenase highly expressed in platelets, has been shown to potentiate the activation of select signaling pathways, including protease-activated receptor 4 (PAR4) and an ITAM-containing receptor complex (GPVI-FcRγ).21-24 The most well understood function of 12-LOX is the production of oxylipins, most notably the conversion of arachidonic acid (AA) to 12-hydroxyeicosatretraenoic acid (12-HETE) upon agonist stimulation of platelets through both G protein-coupled receptor- and non-G protein-coupled receptor-mediated pathways.23 The oxylipin 12-HETE has been shown to be prothrombotic in platelets.25,26 Although the mechanism by which 12-LOX regulates platelet activity is not fully understood, previous publications have demonstrated the ability of 12-LOX activity to augment key signaling components of platelet activation, including Rap1, Ca2+ mobilization, αIIbβ3 activation, and dense granule secretion.21,22,24,26 As 12-LOX activity was recently shown to be required for normal GPVI-mediated platelet activation,21,22 we sought to determine if 12-LOX activity is an essential component of FcγRIIa signaling in platelets.10

In this study, human platelets were treated with the selective 12-LOX inhibitor, ML-355,27 or vehicle control prior to FcγRIIa stimulation to determine if 12-LOX plays a role in the FcγRIIa signaling pathway. Pharmacologic inhibition of 12-LOX activity in human platelets attenuated FcγRIIa-mediated platelet aggregation. Consistent with our human studies, murine platelets isolated from mice expressing human FcγRIIa in their platelets and deficient in 12-LOX had an attenuated response to FcγRIIa stimulation compared with littermates expressing 12-LOX. The activity of 12-LOX was further demonstrated to be essential for a number of biochemical steps known to be essential for FcγRIIa signaling in the platelet. Hence, this study is the first to identify 12-LOX activity as a critical component of normal FcγRIIa signaling in platelets. Further, the results of this study suggest for the first time that 12-LOX may represent a novel therapeutic target to treat immune-mediated thrombocytopenia and thrombosis.

Methods

Preparation of washed human platelets

Prior to blood collection, written informed consent was obtained under approval of the Thomas Jefferson University’s (TJU) Institutional Review Board, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Washed platelets were resuspended in Tyrode’s buffer as previously described21 at a concentration of 3 × 108 platelets/mL unless otherwise indicated.

Mice and platelet preparation

FcγRIIA transgenic mice (humanized FcγRIIa [hFcR]/ALOX12+/+) on C57BL/6J background28 were bred with platelet 12-lipoxygenase knockout (ALOX12−/−) mice21,29 on C57BL6/129S2 background to generate FcγRIIA transgenic mice deficient in platelet 12-lipoxygenase (hFcR/ALOX12−/−). The newly generated hFcR/ALOX12−/− mice appeared phenotypically normal compared with hFcR/ALOX12+/+ mice with similar body size, platelet counts, white blood cell, and red blood cell profiles (see supplemental Table 1 on the Blood Web site). All mice were housed in the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International-approved mouse facility of TJU and the Animal Care and Use Committee of TJU approved experimental procedures. Blood was drawn from the inferior vena cava of 12-week-old anesthetized mice using a syringe containing sodium citrate. Mouse platelet preparation was prepared as previously described.21 Murine platelets of 2.5 × 108 platelets/mL were resuspended in Tyrode’s buffer containing human fibrinogen (75 μg/mL) and CaCl2 (1 mM).

Reagents

Biological materials and reagents used were as follows: human FcγRIIa (IV.3 [CD32]; Stemcell Technologies), human fibrinogen (type I) (Sigma-Aldrich), goat anti-mouse (GAM) IgG (Fab′2; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-CD9 (BD Biosciences), Fluo-4-AM (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), PAC1-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (BD Biosciences), P-selectin-PE (CD62P; BD Biosciences), antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), adenosine triphosphate (ATP) standard (Chrono-Log, Havertown, PA), Chrono-lume (Chrono-Log), Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences), secondary rabbit and mouse antibodies (LI-COR Biosciences), Y759 phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2) antibody (Cell Signaling), and glutathione beads for Rap1 pull down (GE Healthcare).

FcγRIIa-mediated platelet activation

FcγRIIa-mediated platelet activation was initiated by 1 of the following 2 distinct models: 1) FcγRIIa antibody crosslinking, or 2) CD9 monoclonal antibody stimulation. To crosslink FcγRIIa, washed platelets were incubated with IV.3, an FcγRIIa mouse monoclonal antibody for 1 minute, followed by the addition of a GAM IgG antibody to crosslink FcγRIIa. The concentration of FcγRIIa crosslinking antibodies used for each experiment is indicated in the study. Alternatively, washed human platelets were stimulated with an anti-CD9 monoclonal antibody to activate FcγRIIa. Due to inter-individual variability in anti-CD9 response, a range of anti-CD9 concentrations (0.25 to 1 μg/mL) was used to achieve aggregation at each donor’s EC80. In studies using the 12-LOX inhibitor (ML355), washed platelets were incubated with either ML355 (20 μM) or dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (vehicle control) for 15 minutes prior to FcγRIIa stimulation.

Platelet aggregation

Platelet aggregation was measured with a lumi-aggregometer (Model 700D; Chrono-Log) under stirring conditions at 1100 rpm at 37°C.

Quantification of 12-HETE

As an internal standard, 12(S)-HETE-d8 (1 ng) was added to the samples. Platelets pretreated with DMSO or ML355 were stimulated with FcγRIIa crosslinking and quenched with 1% formic acid in acetonitrile at the indicated time points. To prepare the sample for liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) injection, the sample was extracted twice with hexane, dried under N2 gas, reconstituted with acetonitrile/water (1:1, volume/volume), and centrifuged at 20 000g for 5 minutes at 4°C.

LC/MS/MS analysis of the samples was performed on an ACQUITY UPLC System coupled to a Xevo TQ-S MS/MS (Waters Corp.), an electrospray ionization triple quadrupole mass analyzer system. The instrument was operated in the negative mode. The ion source voltage was set at −2.0 kilovolts and desolvation temperature was set at 550°C; 12-HETE was quantified by monitoring specific multiple reaction monitoring transitions. The multiple reaction monitoring transitions of 12-HETE and 12(S)-HETE-d8, the internal standard, were m/z 319 to m/z 179 and m/z 327 to m/z 184, respectively. Chromatographic analysis was performed on the ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (1.7 μm, 100 × 2.1 mm internal diameter). LC mobile phase was composed of 0.25% acetic acid in water solution (solvent A) and isopropanol/acetonitrile (90:10, volume/volume) (solvent B). Solvent B was increased from 30% to 44% at 1 minute, 60% at 6.3 minutes and 7.3 minutes, and 30% at 8 minutes. The detection limit of 12-HETE was 0.2 pg/μL. The linear range of 12-HETE was from 0.5 pg/μL to 50 pg/μL.

PLCγ2 phosphorylation

Washed human platelets were adjusted to 5 × 108 platelets/mL and stimulated in an aggregometer by antibody crosslinking of FcγRIIa, and lysed at designated times with 5× Laemmli reducing buffer (1.5 M Tris-Cl pH 6.8, glycerol, β-mercaptoethanol, 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], and 1% bromophenol blue) to stop the reaction. Samples were separated on a 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gel. Antibodies to PLCγ2 and phospho-Y759 PLCγ2 (Cell Signaling Technology), a marker of PLCγ2 activation, were used to evaluate the relative levels of total and active PLCγ2, respectively.

Calcium mobilization

Intracellular calcium release was measured as previously described.22 Briefly, washed human platelets were resuspended at 1.0 × 106 platelets/mL in Tyrode’s buffer containing 1 mM calcium. Platelets were incubated with Fluo-4-AM (Life Technologies), a cell permeable calcium sensitive dye for 10 minutes prior to stimulation. Platelets were stimulated by FcγRIIa antibody crosslinking, and fluorescence intensity was measured in real-time by flow cytometry in an Accuri C6 flow cytometer. Data are reported as the fold change in the fluorescence intensity comparing maximum fluorescence intensity relative to fluorescence intensity prior to platelet stimulation.

Rap1 activation

Washed human platelets were stimulated by FcγRIIa antibody crosslinking for 5 minutes and aggregation was stopped with 2× platelet lysis buffer. Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator (RalGDS)-Rap binding domain, a truncated form of RalGDS (788-884 aa) that contains the Rap1 binding domain specific for the guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-bound form of Rap1, was used to selectively precipitate the active conformation of Rap1 from the platelet lysate as previously described.30 Total platelet lysate and Rap1 pull-down samples were run on a SDS-PAGE gel and identified by western blot with a Rap1 antibody. The levels of active Rap1-GTP were normalized to the amount of total Rap1 contained in each sample.

Protein kinase C (PKC) activation assay

Washed platelets were stimulated by FcγRIIa antibody crosslinking under stirring conditions (1100 rpm) in an aggregometer at 37°C. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 5× Laemmli sample buffer at the indicated times. As a positive control, platelets were treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (1 mM), a direct PKC agonist, for 1 minute. Samples were run on an SDS-PAGE gel and western blots were performed using antibodies specific for PKC substrate phosphorylation and pleckstrin.

Dense granule secretion

ATP release was measured from washed platelets as surrogate for dense granule secretion. Prior to activation, washed platelets were incubated with Chrono-Lume reagent, an ATP-sensitive dye, for 1 minute. Platelets were stimulated with an FcγRIIa antibody under stirring conditions and fluorescence was measured in real-time using a lumi-aggregometer.

α-Granule release and αIIbβ3 activation

Prior to stimulation, human washed platelets were preincubated with either FITC-conjugated P-selectin antibody or FITC-conjugated PAC-1, an antibody specific for the active conformation of αIIbβ3. Platelets were stimulated with an FcγRIIa antibody and reactions were stopped by the addition of 2% formaldehyde at indicated times. Fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. Results are reported as mean fluorescence intensity.

Western blotting

Standard western blots for Rap1 activation, PKC substrates, and PLCγ2 phosphorylation was used and band intensity was quantified with the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Where applicable, the data represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined with unpaired 1-tailed Student t test using GraphPad Prism software. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

12-LOX regulates FcγRIIa-mediated platelet aggregation

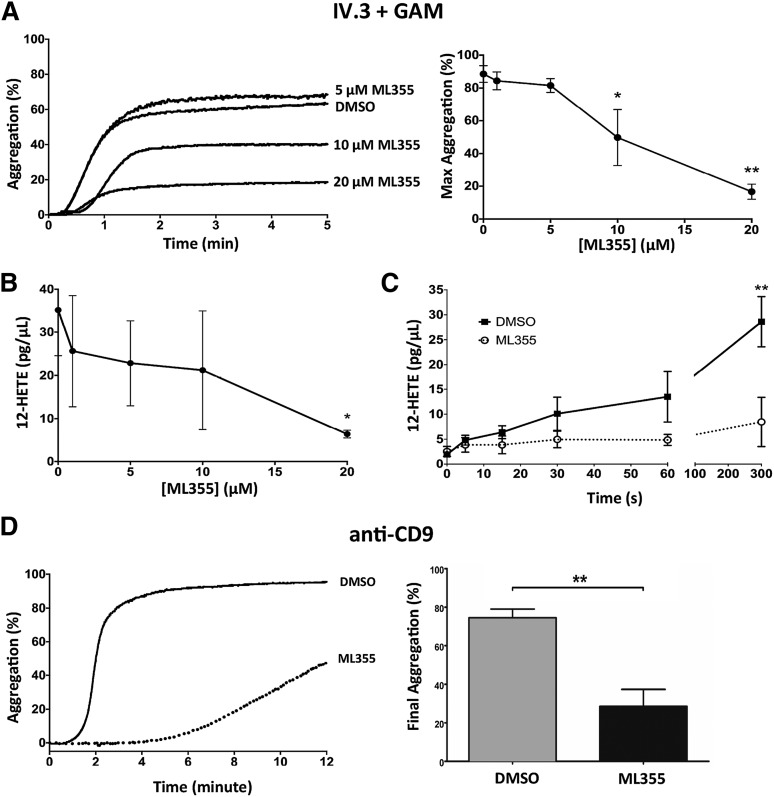

Our study previously showed that pharmacologic inhibition of 12-LOX activity resulted in attenuation of GPVI- or PAR4-mediated platelet activation.21,22 In platelets, FcγRIIa utilizes many of the same downstream signaling effectors as GPVI-FcRγ.10 To determine if 12-LOX plays a role in FcγRIIa-mediated platelet aggregation, washed human platelets were treated with increasing concentrations of ML355, a recently identified highly selective 12-LOX inhibitor,27 or DMSO (vehicle control) prior to FcγRIIa stimulation. Treatment of platelets with ML355 at a concentration of 10 or 20 μM resulted in significant attenuation of FcγRIIa-mediated platelet aggregation via FcγRIIa antibody crosslinking (Figure 1A). To assess if the attenuation of aggregation observed in Figure 1A correlated with the ability of ML355 to inhibit 12-LOX activity, 12-HETE production (ie, the predominant 12-LOX product) was measured in FcγRIIa-stimulated platelets pretreated with DMSO or ML355. Stimulation of FcγRIIa with GAM + IV.3 stimulated platelets with ML355 (20 μM) significantly decreased 12-HETE production (Figure 1B). We observed 20 μM of ML355 as the lowest concentration that efficiently blocked both FcγRIIa-induced platelet aggregation and 12-HETE production, independent of inter-individual variability in response to the inhibitor. Therefore, this concentration of inhibitor was used in all subsequent assays in this study. The kinetics of 12-HETE production in PAR-stimulated platelets was previously determined31; however, the kinetics of 12-HETE production in FcγRIIa-stimulated platelets remains unknown. Therefore, we sought to determine the kinetics of 12-HETE production in FcγRIIa-stimulated platelets. At 15 seconds, 12-HETE formation was significantly enhanced in DMSO-treated platelets stimulated with FcγRIIa agonist (P = .0143) and continued to increase through all times measured (Figure 1C). The production of 12-HETE in FcγRIIa-stimulated platelets was significantly attenuated by ML355 (20 μM) (Figure 1C). FcγRIIa-mediated platelet aggregation in response to a second agonist for FcγRIIa, anti-CD9, was also found to be attenuated in the presence of 20 μM of ML355 (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

12-LOX modulates FcγRIIa-mediated platelet aggregation. (A) The aggregation of washed human platelets was measured following FcγRIIa crosslinking (IV.3 + GAM) in the presence of increasing concentrations of ML355, a 12-LOX inhibitor, ranging from 1 to 20 μM (n = 5) or DMSO (vehicle control, n = 5). The left panel shows the representative dose response of ML355 affecting FcγRIIa-induced aggregation. The right panel is a composite of ML355 doses. (B) Following FcγRIIa crosslinking (IV.3 + GAM), the production of 12-HETE, the predominant 12-LOX oxylipin, was measured in platelets pretreated with concentrations of ML355 ranging from 1 to 20 μM (n = 4) or DMSO (n = 4). (C) 12-HETE production was measured in FcγRIIa crosslinked platelets at increasing time points in the presence of DMSO or ML355 (20 μM) (n = 4). (D) Washed human platelets were pretreated with DMSO (n = 4) or ML355 (20 μM) (n = 8) and platelet aggregation was measured following FcγRIIa stimulation (anti-CD9). Error bars indicate SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01.

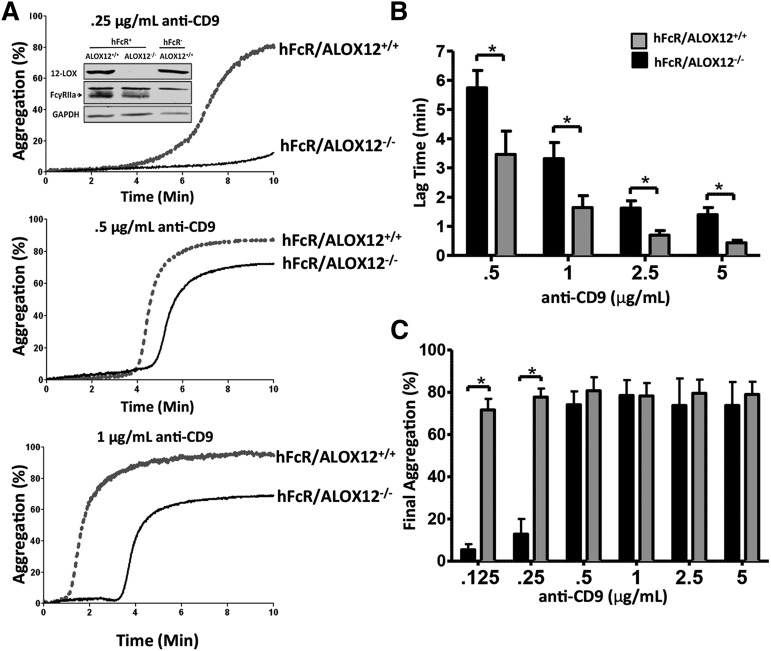

To confirm that the decrease in FcγRIIa-mediated platelet aggregation was due to pharmacologic inhibition of 12-LOX and not a potential off-target effect of the ML355, ex vivo platelet aggregation was measured following anti-CD9 stimulation in hFcR transgenic mice expressing 12-LOX (ALOX12+/+) or a deficiency in 12-LOX (ALOX12−/−). Platelets from mice deficient in 12-LOX (hFcR/ALOX12−/−) showed a delayed (Figure 2A-B) and attenuated (Figure 2C) aggregation in response to anti-CD9 stimulation (0.125 and 0.25 μg/mL) when compared with platelets from mice expressing functional 12-LOX (hFcR/ALOX12+/+). These data suggest that platelets lacking 12-LOX activity through pharmacologic or genetic ablation exhibit a significantly attenuated platelet aggregation response to FcγRIIa activation.

Figure 2.

Murine platelets require 12-LOX for normal FcγRIIa-induced platelet aggregation. A dose response of anti-CD9–induced platelet aggregation was performed with washed platelets from hFcR/ALOX12+/+ or hFcR/ALOX12−/− mice. Prior to aggregation, fibrinogen (75 μg/mL) and CaCl2 (1 mM) were added to platelets. (A) Washed platelets from hFcR/ALOX12+/+ (gray tracings) and hFcR/ALOX12−/− (black tracings) were measured for aggregation in response to 0.25, 0.5, and 1 μg/mL of mouse anti-CD9 for 10 minutes. Inset: western blots for 12-LOX, FcγRIIa, and GAPDH were performed with platelet lysate from hFcR/ALOX12+/+ or hFcR/ALOX12−/− mice. The lag time (B) and final aggregation (C) was measured in hFcR/ALOX12+/+ (gray bars) and hFcR/ALOX12−/− (black bars) washed platelets stimulated with increasing doses of anti-CD9 (n = 3 to 6 per group). Error bars indicate SEM. *P < .05.

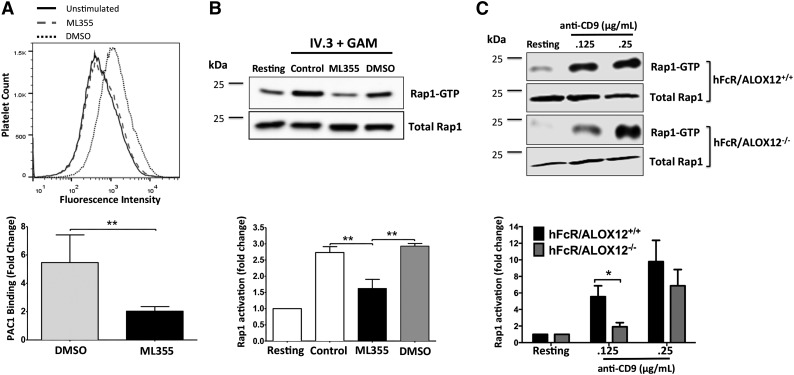

12-LOX regulates αIIbβ3 and Rap1 activity in FcγRIIa-stimulated platelets

Figures 1 and 2 suggest 12-LOX is essential for normal FcγRIIa-mediated platelet aggregation; however, the component(s) in the FcγRIIa pathway regulated by 12-LOX remain unclear. Because the activation of integrin αIIbβ3 is required for platelet aggregation,32,33 the potential role of 12-LOX in mediating αIIbβ3 activation in FcγRIIa-stimulated platelets was investigated. αIIbβ3 activation was measured by PAC1-FITC binding to FcγRIIa-stimulated platelets treated with DMSO or ML355 in flow cytometry. FcγRIIa activation resulted in a large increase in active αIIbβ3 on the platelet surface. Treatment with ML355 prior to stimulation resulted in a significant reduction in PAC1 binding to platelets (Figure 3A), relative to the DMSO control.

Figure 3.

FcγRIIa-mediated Rap1 and integrin αIIbβ3 activation are potentiated by 12-LOX. (A) Washed human platelets pretreated with ML355 or DMSO were stimulated by FcγRIIa crosslinking (IV.3 + GAM) and αIIbβ3 integrin activation (DMSO, n = 3; ML355, n = 6) and (B) Rap1 activation (n = 4) were assessed. (C) hFcR/ALOX12+/+ and hFcR/ALOX12−/− platelets were stimulated with 0.125 and 0.25 μg/mL of mouse anti-CD9 and replicates of n = 5 were assessed for Rap1 activation. PAC1-FITC was used to measure αIIbβ3 activation by flow cytometry. A composite bar graph of PAC1-FITC fold changes relative to the unstimulated PAC1-FITC fluoresence is shown. Activated Rap1 was pulled down using Ral-GDS and blotted with a Rap1 antibody. Active Rap1 was measured using LI-COR and then normalized to total Rap1 and unstimulated for fold change in Rap1 activity. Error bars indicate SEM. **P < .01.

Although αIIbβ3 activation is under the control of a complex milieu of signaling proteins including Talin, RIAM1, and Rap1,34 the latter, a small G protein regulated by calcium and PKC, is known to play a central role in inside-out activation of αIIbβ3.11,35-38 Therefore, Rap1 activation was measured following FcγRIIa stimulation for 5 minutes in washed human platelets treated with or without ML355 (Figure 3B). FcγRIIa stimulation of platelets (control) resulted in a significant increase in active Rap1-GTP. However, platelets treated with ML355, and subsequently stimulated through FcγRIIa, failed to activate Rap1. To confirm that the inhibition of Rap1 was not due to the vehicle, platelets were treated with DMSO and stimulated with FcγRIIa. Treatment with DMSO did not result in attenuation in Rap1 activation compared with untreated control.

While unlikely, it is possible that ML355 inhibits Rap1 in a 12-LOX-independent manner. To determine if this is the case, Rap1 activation was measured in platelets from mice expressing human FcγRIIa and 12-LOX (hFcR/ALOX12+/+) or deficient in 12-LOX (hFcR/ALOX12−/−). FcγRIIa-mediated Rap1 activation in the platelet was measured following stimulation with anti-CD9 (Figure 3C). Rap1 activity was significantly increased in mouse platelets expressing both human FcγRIIa and endogenous 12-LOX. However, the genetic ablation of 12-LOX (hFcR/ALOX12−/−) resulted in a significant attenuation of anti-CD9–mediated Rap1 activation, thereby, confirming the importance of 12-LOX in this process.

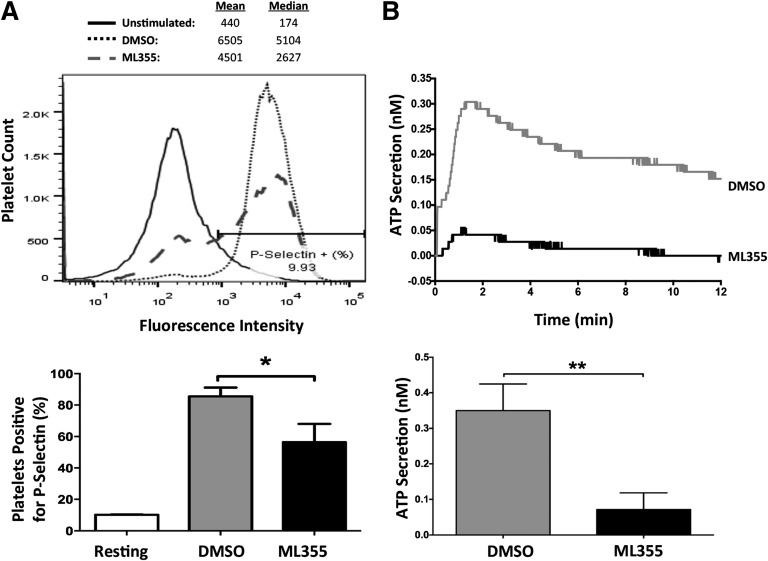

12-LOX regulates dense and α-granule secretion in FcγRIIa-activated platelets

The release of α and dense granules from activated platelets serves to amplify platelet aggregation39-42 and is an important component in normal agonist-induced platelet activation. To determine if 12-LOX plays a role in FcγRIIa-mediated granule secretion, surface expression of P-selectin was used as a surrogate marker to measure α-granule secretion in FcγRIIa-stimulated platelets, and measurement of ATP release was assessed as a measure of agonist-induced dense granule secretion. FcγRIIa-stimulated platelets treated with ML355 showed a significant decrease in the percentage of platelets that expressed P-selectin on their surface compared with DMSO-treated platelets (Figure 4A). Additionally, FcγRIIa-stimulated platelets treated with ML355 showed a significant attenuation in ATP release compared with DMSO-treated platelets (Figure 4B). The data strongly supports a role for 12-LOX regulation of FcγRIIa-mediated platelet secretion through release of dense and partial regulation of α-granule secretion.

Figure 4.

Granule secretion mediated by FcγRIIa activation is regulated by 12-LOX. Washed human platelets treated with DMSO or ML355 were stimulated by FcγRIIa crosslinking in which IV.3 (2 μg/mL) + GAM (10 μg/mL) were used for (A) α-granule secretion. α-granule secretion was measured by using P-selectin-PE conjugated antibody in a flow cytometer. To obtain the percentage of platelets that were positive for P-selectin, approximately 10% of the unstimulated platelet population was gated (as shown in histogram), and then applied to ML355- and DMSO-treated platelets in order to quantify the percentage of platelets that were positive for P-selectin. A composite bar graph shows the percentage of platelets positive for P-selectin in ML355- and DMSO-treated platelets (n = 5). (B) IV.3 (2 μg/mL) + GAM (5 μg/mL) were used to stimulate ATP secretion as a surrogate marker for dense granule secretion in a lumi-aggregometer. A bar graph of DMSO- or ML355-treated platelets measured for ATP secretion following FcγRIIa crosslinking (n = 4) is shown. Error bars indicate SEM. **P < .01.

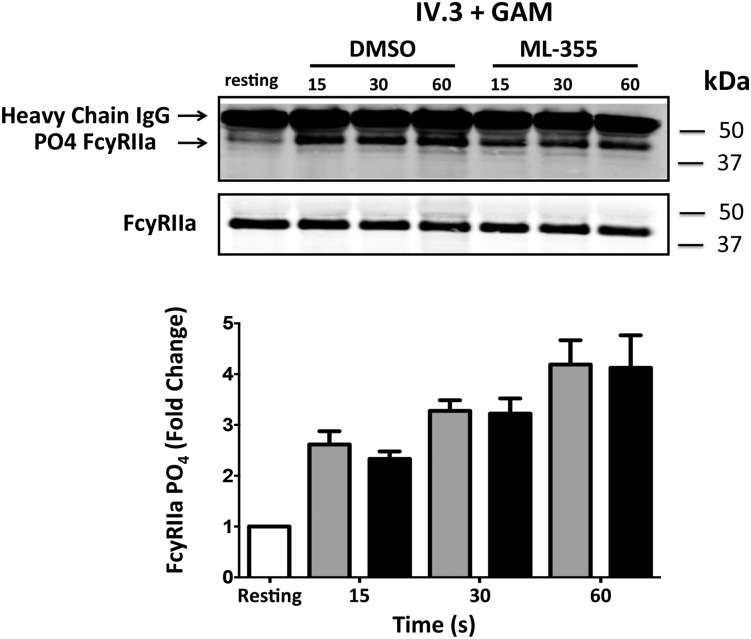

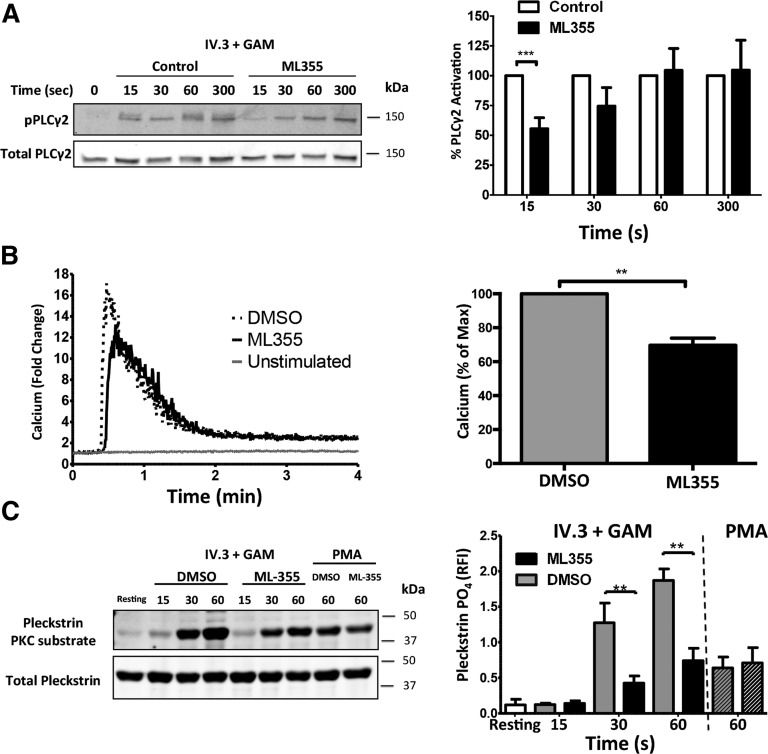

12-LOX modulates proximal signaling components of the FcγRIIa pathway in human platelets

As shown in Figures 1-3, 12-LOX activity is required for the normal activation of distal signaling components of the FcγRIIa pathway (Rap1, αIIbβ3, and platelet aggregation). We sought to identify the earliest biochemical steps in the FcγRIIa pathway that are regulated by 12-LOX. The earliest signaling observed following FcγRIIa activation is ITAM phosphorylation, which has been shown to result in Syk activation.43-46 Syk activation leads to activation of PLCγ2 resulting in calcium release and PKC activation, both of which are critical for platelet activation.47,48 To determine where in this complex signaling milieu 12-LOX plays an essential role in FcγRIIa signaling in the platelet, a number of the signaling components directly downstream of FcγRIIa activation were assessed in the presence or absence of ML355. To investigate whether 12-LOX directly regulated phosphorylation of the FcγRIIa receptor, the first step in FcγRIIa-mediated platelet activation, FcγRIIa was immunoprecipitated from IV.3 + GAM-stimulated platelets treated with ML355 or DMSO and immunoblotted for phosphorylation of FcγRIIa. Stimulation of FcγRIIa resulted in a noticeable increase in receptor phosphorylation. Treatment with ML355 failed to cause a reduction in FcγRIIa phosphorylation (Figure 5). This data suggests that 12-LOX activity is not required for phosphorylation of FcγRIIa itself.

Figure 5.

The role of 12-LOX in regulating the FcγRIIa signaling complex. Washed human platelets were treated with ML355 (20 μM) or vehicle control prior to stimulation by crosslinking (IV.3 + GAM). Immunoprecipitation of FcγRIIa was conducted at 15, 30, and 60 seconds post-crosslinking, and phosphorylation of FcγRIIa was measured via western blot. The bar graph shows immunoprecipitated FcγRIIa that had been treated with DMSO or ML355 following FcγRIIa crosslinking and was assessed for phosphorylation (n = 7). Error bars indicate SEM.

To assess if 12-LOX regulates PLCγ2 activation downstream of FcγRIIa, phosphorylation of PLCγ2 was measured in washed human platelets in the presence or absence of ML355. Platelets stimulated through FcγRIIa were phosphorylated within 15 seconds following stimulation. Platelets treated with ML355, however, showed significantly attenuated PLCγ2 phosphorylation at 15 seconds compared with control conditions (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

12-LOX modulates early signaling components of the FcγRIIa pathway in human platelets. Washed human platelets were treated with ML355 (20 μM) or vehicle control prior to stimulation by crosslinking (IV.3 + GAM). (A) A time course of PLCγ2 phosphorylation at site Y759 was assessed by western blot analysis. All samples were normalized to total PLCγ2 and fold changes were quantified relative to the unstimulated condition. The bar graph comprised of n = 7 individuals. (B) Following crosslinking (IV.3 + GAM), calcium mobilization was measured by flow cytometry. Representative curves were quantitated in fold change of free calcium relative to the unstimulated condition over 4 minutes. Bar graphs represent the ratio of the fold change in calcium mobilization (n = 5). (C) N = 7 stimulated human platelets with or without ML355 were analyzed for PKC activity following CD32 crosslinking, and PMA rescue comprised of n = 3. A PKC substrate was blotted as a surrogate for PKC activation and pleckstrin phosphorylation. Data represents mean ± SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Because 12-LOX attenuated FcγRIIa-mediated PLCγ2 activation, its effects on intracellular calcium release were measured. FcγRIIa was stimulated in washed human platelets treated with or without ML355 and calcium release was measured. Platelets treated with ML355 exhibited a decrease in intracellular calcium following platelet stimulation, compared with DMSO-treated platelets (Figure 6B), supporting a physiological role for both PLCγ2 and calcium in 12-LOX regulation of FcγRIIa. Because PLCγ2 activation leads to activation of PKC in platelets through calcium mobilization, the potential regulation of FcγRIIa-mediated PKC activity by 12-LOX was also evaluated. Platelets stimulated through the FcγRIIa pathway showed a high level of PKC-mediated phosphorylation as measured by a phospho-substrate PKC antibody. A significant decrease in PKC activation was observed in platelets treated with ML355 at 30 and 60 seconds, compared with platelets treated with the vehicle control (Figure 6C). This regulation of PKC by ML355 was determined to be indirect since PKC activation by PMA, a direct PKC activator, showed no difference in its ability to activate PKC either in control or in ML355-treated platelets.

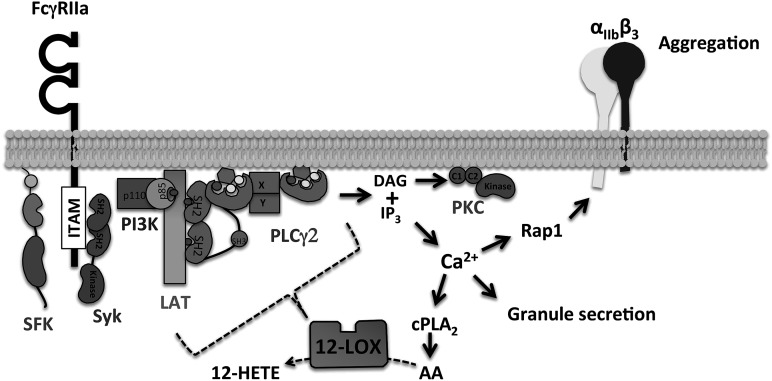

Discussion

It has been recently shown that 12-LOX is an important regulator of GPVI-mediated platelet activation.21,22 As FcγRIIa and GPVI are purported to signal via a conserved pathway, we postulated that 12-LOX may play an essential role in the regulation of FcγRIIa signaling in human platelets. This study is the first to demonstrate that 12-LOX is an essential component of FcγRIIa immune-mediated platelet activation. Human platelets treated with a highly selective 12-LOX inhibitor, ML355,27 or FcγRIIa transgenic mouse platelets deficient in 12-LOX, showed significantly attenuated aggregation in response to FcγRIIa-mediated activation. To investigate the underlying mechanism by which 12-LOX regulates FcγRIIa-mediated platelet activation, the activity of multiple signaling intermediates in the FcγRIIa pathway were assessed in the presence of the 12-LOX inhibitor, ML355. Following stimulation, platelets treated with ML355 were significantly attenuated along multiple signaling steps in the immune-mediated FcγRIIa activation pathway, including αIIbβ3, Rap1, Ca2+, PLCγ2, PKC, and granule secretion (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Schematic model of 12-LOX role in the regulation of FcγRIIa pathway. 12-LOX regulates early PLCγ2 activation mediated by FcγRIIa stimulation, which is essential for full calcium release in the platelets. Calcium flux is required for cPLA2 activity to generate free fatty acids, such as AA. Subsequently, Rap1 activation is also dependent on 12-LOX activity in order to activate integrin αIIbβ3 for platelet aggregation.

The most studied function of 12-LOX is to produce oxylipins, such as 12(S)-HETE from free fatty acids in the cell membrane. Although previous work has showed that selective 12-LOX inhibitors significantly reduced oxylipin production and were associated with reduced platelet-mediated reactivity, the role of these bioactive metabolites in platelet activation remains unclear. Our study demonstrates that a significant increase in 12-HETE formation is reproducibly observed within 15 seconds following FcγRIIa crosslinking-mediated 12-LOX oxidation of AA (P = .0143) (Figure 1C). Our data also suggests that 12-LOX may partially regulate FcγRIIa-induced platelet activation either through oxylipin formation, and subsequent metabolite signaling,49,50 or directly through a protein complex formation within the cell.51-53 Although both of these regulatory mechanisms are plausible, the kinetics by which 12-LOX inhibition attenuates FcγRIIa signaling may favor a direct role for 12-LOX in regulating the FcγRIIa pathway through nonenzymatic regulation of the FcγRIIa signaling cascade.

Although 12-LOX activity is required for normal FcγRIIa-mediated platelet activation, the direct molecular component by which 12-LOX activity is required has yet to be determined. For instance, 12-LOX was not required for FcγRIIa phosphorylation, suggesting 12-LOX activity is not directly regulating Src family kinase activity. However, 12-LOX activity was shown to be important for early PLCγ2 activation, indicating that 12-LOX may be an important regulator in the kinetics of PLCγ2 activation affecting downstream effectors. The delay in PLCγ2 activation due to 12-LOX inhibition may be attributed to direct regulation of PLCγ2 or regulation of upstream effectors such as linker of activation of T cells, or Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. The data presented here narrows the scope of where 12-LOX impinges on the FcγRIIa pathway to a proximal point in the signaling pathway between the receptor and PLCγ2.

The role of FcγRIIa signaling is well established in the pathogenesis of immune-mediated thrombosis such as HIT and thrombosis, an iatrogenic disorder characterized by immune-mediated platelet activation that can lead to life-threatening thrombosis. HIT is a paradigm of the immune tolerance therapy disorders, immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, and thrombosis. Alternative therapeutic interventions, such as direct thrombin inhibitors, have been considered for anticoagulation therapy; however, complications of bleeding remains a primary concern.54 Even with this potentially fatal complication, heparin remains the standard anticoagulant for prevention and treatment of thrombosis. Therefore, there is a need for novel therapeutic approaches that directly treat the pathogenesis of HIT. The activation of platelets by pathogenic HIT immune complexes requires FcγRIIa signaling, which makes it an attractive target. Although the pathogenesis of HIT is complex, we have provided strong evidence supporting 12-LOX as a key regulator of FcγRIIa-mediated platelet activation. Hence, this study has delineated for the first time, a novel approach in the regulation of HIT, and potentially other immune tolerance therapy disorders through inhibition of human platelet 12-LOX.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Johnny Yu for his work in preparation of platelet samples for 12-HETE measurements by LC/MS/MS.

This study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of General Medical Sciences; R01 GM105671) (M.H.), (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; R01 HL114405) (M.H. and S.E.M.), and (National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; R01 MD007880) (M.H.), the American Heart Association (12BGIA11890000) (M.H.), the Parenteral Drug Association Foundation for Pharmaceutical Sciences (M.H.), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; (P01 HL110860) (S.E.M.), and the Cardeza Foundation for Hematologic Research (M.H. and S.E.M.). D.K.L., A.J., A.S., and D.J.M. were supported by the intramural research program of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the Molecular Libraries Initiative of the National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research (U54MH084681).

Footnotes

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: J.Y. and B.E.T. equally designed, performed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data/results, and wrote the manuscript; P.F.-P. and J.V. performed mouse Rap1 and calcium mobilization experiments and analyzed the data; J.R. performed the LC/MS/MS experiments and edited the manuscript; C.J.S., D.K.L., A.J., A.S., D.J.M., and T.R.H. designed, produced, validated and provided the inhibitor ML355, and edited the manuscript; S.E.M. provided the FcγRIIa mice, designed experiments and interpreted data, and edited the manuscript; M.H. designed experiments and interpreted data, wrote, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael Holinstat, Department of Medicine, Cardeza Foundation for Hematologic Research, Thomas Jefferson University, 1020 Locust St, Suite 394, Jefferson Alumni Hall, Philadelphia, PA 19107; e-mail: michael.holinstat@jefferson.edu.

References

- 1.Zucker MB, Nachmias VT. Platelet activation. Arteriosclerosis. 1985;5(1):2–18. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.5.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furie B, Furie BC. Mechanisms of thrombus formation. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(9):938–949. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng CM, Hawiger J. Affinity isolation and characterization of immunoglobulin G Fc fragment-binding glycoprotein from human blood platelets. J Biol Chem. 1979;254(7):2165–2167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Looney RJ, Anderson CL, Ryan DH, Rosenfeld SI. Structural polymorphism of the human platelet Fc gamma receptor. J Immunol. 1988;141(8):2680–2683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelton JG, Sheridan D, Santos A, et al. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: laboratory studies. Blood. 1988;72(3):925–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hauch TW, Rosse WF. Platelet-bound complement (C3) in immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 1977;50(6):1129–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuji M, Ezumi Y, Arai M, Takayama H. A novel association of Fc receptor gamma-chain with glycoprotein VI and their co-expression as a collagen receptor in human platelets. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(38):23528–23531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki-Inoue K, Fuller GL, García A, et al. A novel Syk-dependent mechanism of platelet activation by the C-type lectin receptor CLEC-2. Blood. 2006;107(2):542–549. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenfeld SI, Looney RJ, Leddy JP, Phipps DC, Abraham GN, Anderson CL. Human platelet Fc receptor for immunoglobulin G. Identification as a 40,000-molecular-weight membrane protein shared by monocytes. J Clin Invest. 1985;76(6):2317–2322. doi: 10.1172/JCI112242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergmeier W, Stefanini L. Platelet ITAM signaling. Curr Opin Hematol. 2013;20(5):445–450. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283642267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasirer-Friede A, Kahn ML, Shattil SJ. Platelet integrins and immunoreceptors. Immunol Rev. 2007;218:247–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhi H, Rauova L, Hayes V, et al. Cooperative integrin/ITAM signaling in platelets enhances thrombus formation in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2013;121(10):1858–1867. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-443325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugiyama T, Okuma M, Ushikubi F, Sensaki S, Kanaji K, Uchino H. A novel platelet aggregating factor found in a patient with defective collagen-induced platelet aggregation and autoimmune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 1987;69(6):1712–1720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moroi M, Jung SM, Okuma M, Shinmyozu K. A patient with platelets deficient in glycoprotein VI that lack both collagen-induced aggregation and adhesion. J Clin Invest. 1989;84(5):1440–1445. doi: 10.1172/JCI114318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arai M, Yamamoto N, Moroi M, Akamatsu N, Fukutake K, Tanoue K. Platelets with 10% of the normal amount of glycoprotein VI have an impaired response to collagen that results in a mild bleeding tendency. Br J Haematol. 1995;89(1):124–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb08900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki-Inoue K, Inoue O, Ozaki Y. Novel platelet activation receptor CLEC-2: from discovery to prospects. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(suppl 1):44–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takai T. Roles of Fc receptors in autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(8):580–592. doi: 10.1038/nri856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer T, Robles-Carrillo L, Robson T, et al. Bevacizumab immune complexes activate platelets and induce thrombosis in FCGR2A transgenic mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(1):171–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox D, Kerrigan SW, Watson SP. Platelets and the innate immune system: mechanisms of bacterial-induced platelet activation. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(6):1097–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reilly MP, Sinha U, André P, et al. PRT-060318, a novel Syk inhibitor, prevents heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis in a transgenic mouse model. Blood. 2011;117(7):2241–2246. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-274969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeung J, Apopa PL, Vesci J, et al. 12-lipoxygenase activity plays an important role in PAR4 and GPVI-mediated platelet reactivity. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110(3):569–581. doi: 10.1160/TH13-01-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeung J, Apopa PL, Vesci J, et al. Protein kinase C regulation of 12-lipoxygenase-mediated human platelet activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;81(3):420–430. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.075630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coffey MJ, Jarvis GE, Gibbins JM, et al. Platelet 12-lipoxygenase activation via glycoprotein VI: involvement of multiple signaling pathways in agonist control of H(P)ETE synthesis. Circ Res. 2004;94(12):1598–1605. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000132281.78948.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nyby MD, Sasaki M, Ideguchi Y, et al. Platelet lipoxygenase inhibitors attenuate thrombin- and thromboxane mimetic-induced intracellular calcium mobilization and platelet aggregation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278(2):503–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan LT, Thomas CP, Kühn H, O’Donnell VB. Thrombin-activated human platelets acutely generate oxidized docosahexaenoic-acid-containing phospholipids via 12-lipoxygenase. Biochem J. 2010;431(1):141–148. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katoh A, Ikeda H, Murohara T, Haramaki N, Ito H, Imaizumi T. Platelet-derived 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid plays an important role in mediating canine coronary thrombosis by regulating platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa activation. Circulation. 1998;98(25):2891–2898. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.25.2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luci DK, Jameson JB, II, Yasgar A, et al. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship studies of 4-((2-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzyl)amino)benzenesulfonamide derivatives as potent and selective inhibitors of 12-lipoxygenase. J Med Chem. 2014;57(2):495–506. doi: 10.1021/jm4016476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKenzie SE, Taylor SM, Malladi P, et al. The role of the human Fc receptor Fc gamma RIIA in the immune clearance of platelets: a transgenic mouse model. J Immunol. 1999;162(7):4311–4318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson EN, Brass LF, Funk CD. Increased platelet sensitivity to ADP in mice lacking platelet-type 12-lipoxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(6):3100–3105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Triest M, de Rooij J, Bos JL. Measurement of GTP-bound Ras-like GTPases by activation-specific probes. Methods Enzymol. 2001;333:343–348. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)33068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holinstat M, Boutaud O, Apopa PL, et al. Protease-activated receptor signaling in platelets activates cytosolic phospholipase A2α differently for cyclooxygenase-1 and 12-lipoxygenase catalysis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(2):435–442. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.219527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bledzka K, Smyth SS, Plow EF. Integrin αIIbβ3: from discovery to efficacious therapeutic target. Circ Res. 2013;112(8):1189–1200. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips DR, Agin PP. Platelet membrane defects in Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia. Evidence for decreased amounts of two major glycoproteins. J Clin Invest. 1977;60(3):535–545. doi: 10.1172/JCI108805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee HS, Lim CJ, Puzon-McLaughlin W, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH. RIAM activates integrins by linking talin to ras GTPase membrane-targeting sequences. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(8):5119–5127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807117200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe N, Bodin L, Pandey M, et al. Mechanisms and consequences of agonist-induced talin recruitment to platelet integrin alphaIIbbeta3. J Cell Biol. 2008;181(7):1211–1222. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Smyth SS, Schoenwaelder SM, Fischer TH, White GC., II Rap1b is required for normal platelet function and hemostasis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(3):680–687. doi: 10.1172/JCI22973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bertoni A, Tadokoro S, Eto K, et al. Relationships between Rap1b, affinity modulation of integrin alpha IIbbeta 3, and the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(28):25715–25721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202791200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brass LF, Manning DR, Shattil SJ. GTP-binding proteins and platelet activation. Prog Hemost Thromb. 1991;10:127–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holmsen H, Weiss HJ. Secretable storage pools in platelets. Annu Rev Med. 1979;30:119–134. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.30.020179.001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukami MH, Salganicoff L. Human platelet storage organelles. A review. Thromb Haemost. 1977;38(4):963–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Israels SJ, McNicol A, Robertson C, Gerrard JM. Platelet storage pool deficiency: diagnosis in patients with prolonged bleeding times and normal platelet aggregation. Br J Haematol. 1990;75(1):118–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1990.tb02626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McNicol A, Israels SJ. Platelet dense granules: structure, function and implications for haemostasis. Thromb Res. 1999;95(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(99)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asselin J, Gibbins JM, Achison M, et al. A collagen-like peptide stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of syk and phospholipase C gamma2 in platelets independent of the integrin alpha2beta1. Blood. 1997;89(4):1235–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blake RA, Schieven GL, Watson SP. Collagen stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of phospholipase C-gamma 2 but not phospholipase C-gamma 1 in human platelets. FEBS Lett. 1994;353(2):212–216. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gibbins J, Asselin J, Farndale R, Barnes M, Law CL, Watson SP. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the Fc receptor gamma-chain in collagen-stimulated platelets. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(30):18095–18099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.18095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yanaga F, Poole A, Asselin J, et al. Syk interacts with tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins in human platelets activated by collagen and cross-linking of the Fc gamma-IIA receptor. Biochem J. 1995;311(Pt 2):471–478. doi: 10.1042/bj3110471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strehl A, Munnix IC, Kuijpers MJ, et al. Dual role of platelet protein kinase C in thrombus formation: stimulation of pro-aggregatory and suppression of procoagulant activity in platelets. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(10):7046–7055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611367200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yacoub D, Théorêt JF, Villeneuve L, et al. Essential role of protein kinase C delta in platelet signaling, alpha IIb beta 3 activation, and thromboxane A2 release. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(40):30024–30035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo Y, Zhang W, Giroux C, et al. Identification of the orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR31 as a receptor for 12-(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(39):33832–33840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.216564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomas CP, Morgan LT, Maskrey BH, et al. Phospholipid-esterified eicosanoids are generated in agonist-activated human platelets and enhance tissue factor-dependent thrombin generation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(10):6891–6903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.078428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jankun J, Aleem AM, Malgorzewicz S, et al. Synthetic curcuminoids modulate the arachidonic acid metabolism of human platelet 12-lipoxygenase and reduce sprout formation of human endothelial cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(5):1371–1382. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kandouz M, Nie D, Pidgeon GP, Krishnamoorthy S, Maddipati KR, Honn KV. Platelet-type 12-lipoxygenase activates NF-kappaB in prostate cancer cells. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2003;71(3-4):189–204. doi: 10.1016/s1098-8823(03)00042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nie D, Krishnamoorthy S, Jin R, et al. Mechanisms regulating tumor angiogenesis by 12-lipoxygenase in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(27):18601–18609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601887200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Greinacher A, Althaus K, Krauel K, Selleng S. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Hamostaseologie. 2010;30(1) 17-18, 20-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]