Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a serious threat to public health, causing 2 million deaths annually world-wide. The control of TB has been hindered by the requirement of long duration of treatment involving multiple chemotherapeutic agents, the increased susceptibility to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in the HIV-infected population, and the development of multi-drug resistant and extensively resistant strains of tubercle bacilli. An efficacious and cost-efficient way to control TB is the development of effective anti-TB vaccines. This measure requires thorough understanding of the immune response to M. tuberculosis. While the role of cell-mediated immunity in the development of protective immune response to the tubercle bacillus has been well established, the role of B cells in this process is not clearly understood. Emerging evidence suggests that B cells and humoral immunity can modulate the immune response to various intracellular pathogens, including M. tuberculosis. These lymphocytes form conspicuous aggregates in the lungs of tuberculous humans, non-human primates, and mice, which display features of germinal center B cells. In murine TB, it has been shown that B cells can regulate the level of granulomatous reaction, cytokine production, and the T cell response. This chapter discusses the potential mechanisms by which specific functions of B cells and humoral immunity can shape the immune response to intracellular pathogens in general, and to M. tuberculosis in particular. Knowledge of the B cell-mediated immune response to M. tuberculosis may lead to the design of novel strategies, including the development of effective vaccines, to better control TB.

Keywords: Myocobacterium tuberculosis, Humoral immunity, B cells, Antibodies, T cell responses, Antigen presentation, Cytokines, Cytokine production, Fcγ receptors, Macrophages, Neutrophils, Granuloma, Immunopathology

1 Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB), is a major global health threat, resulting in over 2 million deaths each year [1]. M. tuberculosis is a remarkably successful pathogen due to its ability to modulate and to evade immune responses [2–4]. Cell-mediated immunity effectively regulates bacterial containment in granulomatous lesions in the lungs, usually without completely eradicating the bacteria, which persist in a latent state [5]. However, reactivation of TB can occur when the host immune system is compromised by various factors, such as HIV infection and the use of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockade therapy for a variety of inflammatory diseases [6–8]. The ability of M. tuberculosis to manipulate and evade immune responses presents a major challenge for the development of efficacious therapies and anti-TB vaccines [3, 4, 9–11]. Bacillus Calmette-Guèrin (BCG), an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis, is the only anti-TB vaccine that is currently administered [12]. Although BCG protects adequately against pediatric TB meningitis, its protective effect for adult pulmonary TB, a most common form of the disease, is inconsistent at best [13–16]. A more thorough understanding of protective immunity and the ways by which M. tuberculosis manipulates these responses will aid in the control of TB [12, 17, 18].

It has been well established that cell-mediated immunity plays critical roles in defense against M. tuberculosis [3, 4, 11]; by contrast, B cells and antibodies generally have been considered unimportant in providing protection [19–21]. This notion has derived, at least in part, from inconsistent efficacy of anti-TB passive immune therapies tested in the late nineteenth century, which possibly could be due to the varied treatment protocols and reagents employed [20, 22]. In the late nineteenth century, the development of the concept of cell-mediated immune response based on Elie Metchnikoff starfish larvae observation as well as antibody-mediated immunity derived from Ehrlich’s side-chain theory [23–25] set the stage for the subsequent emergence of the view that defense against intracellular and extracellular pathogens are mediated by cell-mediated and humoral immune responses, respectively [26, 27]. Guided by this concept of division of immunological labor, the role of humoral immune response in defense against M. tuberculosis, a prominent intracellular pathogen, is generally thought of as insignificant [19, 28, 29]. However, accumulating experimental evidence derived from studying intracellular and extracellular pathogens suggest that the dichotomy of niche-based defense mechanisms is not absolute [19, 28, 29]. A more comprehensive unbiased approach to evaluate the contribution of both the cell-mediated immune response and B cells and humoral immunity to protection against pathogens regardless of their niche could further advance our knowledge of host defense that may eventually influence on the development of efficacious vaccines. The importance of this comprehensive approach is further reinforced by the advancement of our knowledge in immunology and vaccine development that highlights the significance of the interactions between innate and adaptive immunity, as well as those between various immune cells and subsets in the development of effective immune response against microbes [30]. This approach may be particularly important for pathogens, such as M. tuberculosis, for which consistently protective vaccines are still lacking.

2 Do B Cells and Humoral Immunity Contribute to Defense Against Intracellular Pathogens?

Based on the concept of division of labor by the cell-mediated and the humoral arm of the immune response in controlling pathogens, protection against intracellular microbes is generally thought to be mediated exclusively by cell-mediated immunity [28]. This has led to the use of highly T cell-centric strategies for the development of vaccines against intracellular pathogens including M. tuberculosis [31]. Complete exclusion of a role for B cell and humoral immune response in defense against microbes that gravitate to an intracellular locale is, however, problematic. Indeed, emerging evidence supports a role for B cells and the humoral response in protection and in shaping the immune response to pathogens whose life cycle requires an intracellular environment such as Chlamydia trachomatis, Salmonella enterica, Leishmania major, Francisella tularensis, Plasmodium spp., and Ehrlichia chaffeensis [32–38]. Interestingly, humoral immunity has been shown to contribute to protection against E. chaffeensis, a bacterium classified as an obligate intracellular pathogen [34]. This observation has led to the discovery of an extracellular phase in the life cycle of E. chaffeensis [34]. The Ehrlichia study suggests that even a brief extracellular sojourn may expose an obligate intracellular organism to antibody-mediated defense mechanisms operative in extracellular milieu. Indeed, it is likely that many intracellular pathogens exist in the extracellular space at some point in the infection cycle, making them vulnerable to the actions of antibodies [28]; and evidence exists that this notion is applicable to M. tuberculosis [39–41]. In the control of viruses, the quintessential class of obligatory intracellular pathogen, antibodies have been shown to play an important role in disease control and virion clearance from infected tissues involving mechanisms that are independent of neutralization resulting from direct interaction of immunoglobulins with viral particles. For examples, binding of antibodies to membrane-associated viral antigens of infected cells have been shown to attenuate transcription and replication of the virus [42–44]. Additionally, immunoglobulins (e.g., certain anti-DNA [45] and anti-viral IgA antibodies [46, 47]) have been shown to be able to enter cells.

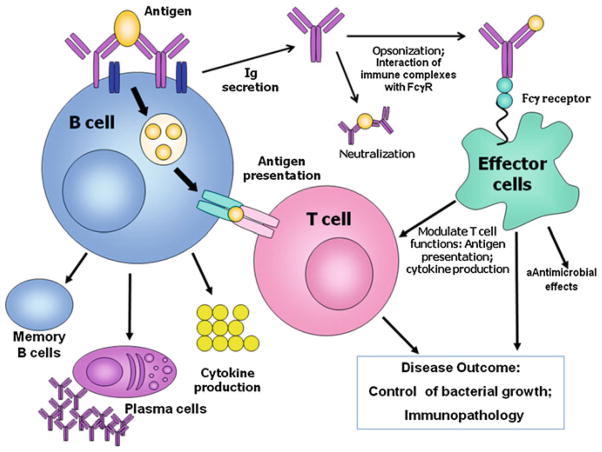

B cells can shape the immune response by modulating T cells via a number of mechanisms based on antigen presentation and the production of antibodies and cytokines [21, 48] (Fig. 1). B cells and humoral immunity contribute to the development of T cell memory [49–57] and vaccine-induced protection against a secondary challenge [21, 48] (two components critical to development of effective vaccines) with intracellular bacteria such as Chlamydia [58] and Fransicella [59]. Thus, infections with intracellular microbes where cell-mediated immunity is central to protection may also require humoral immunity for optimal clearance and vaccine efficacy. This dual requirement for both the cell-mediated and humoral immunity also applies to the development of optimal immune response to extracellular pathogens. For example, it has been reported that cellular immunity contributes to defense against Streptococcus pneumoniae [60] and T cells shapes the host response to Escherichia coli infection [61]; furthermore, the antigen-presenting attribute of B cells plays an important role in host defense against extracellular helminthes [57]. Together, these observations have provided evidence that, regardless of the preferred niche of the pathogens in the host, the immune response against invading microbes is shaped by the collaborative effects of cellular immunity and the B cell and humoral immunity. In the context of intracellular microbes such as M. tuberculosis, and particularly those for which efficacious vaccines are lacking, understanding how B cells regulate the immune response to the pathogens, and how these immune cells and antibody-dependent immunity interact with the cellular arm of the host response to mediate protective effectors will likely aid in the development of strategies to enhance anti-microbial immunity and vaccine efficacy.

Fig. 1. How do B cells modulate the immune responses to M. tuberculosis.

Production of M. tuberculosis-specific antibodies can mediate the formation of immune complex that can modulate the functions of effector cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages. It remains to be demonstrated whether specific neutralizing antibodies exist. B cells can serve as antigen presenting cells to influence T cell activation, polarization, and effector functions and the establishment of T cell memory. B cells can also modulate the functions of granulomatous immune cells. In concert, these antibody-dependent and independent functions of B cells play an important role in determining disease outcome in terms of the elimination of control of bacteria, as well as the development of immunopathology that could damage tissues and promote dissemination

3 B Cells Can Influence T Cell Responses

The interaction of T cells and B cells in response to an antigenic challenge has been well studied. These studies, however, have mostly focused on the characterization the mechanisms by which T cells provide help to B cells [62]. It has been firmly established that T cells play an important role in modulating the response of B cells to antigens, affecting biological functions as diverse as antibody production and cytokine secretion [62]. In contrast, the role of B cells in regulating T cell responses is less well-defined; and this is particularly the case for CD8+ T cells. This line of investigation has yielded conflicting results [48, 63], which are likely due, at least partially, to the complexity of the experimental systems employed, which use varied antigens and mouse models. For example, a much used model involves mice rendered deficient in B cells genetically, although non-B cell immunological aberrancy is known to exist in these strains [48]. The use of the B cell-depleting agent Rituximab in the treatment of a variety of human diseases have provided an excellent opportunity to study the role of B cells in shaping immune responses [64, 65]. These studies have provided compelling evidence that B cells regulate CD4+ T cell responses [48]. Although less well studied, accumulating evidence suggests a role for B cells in regulating CD8+ T cell responses including through antigen presentation [54, 66–68], even though, as in the case for CD4+ T cells, the results derived from these studies are not entirely congruent [69, 70].

Antigen presentation

Evidence that B cells and T cells cooperate in an immune response to induce the production of antibodies began to emerge in the late 1960s [71, 72]. Following up on this discovery, subsequent investigations revealed that this collaboration is mediated by the MHCII-restricted antigen presentation by antigen-experienced B cells to antigen-specific T cells [73, 74]. The T cells provide help to the interacting B cells, leading to B cell activation, high-affinity antibody responses, the development of B cell memory and antibody-producing plasma cells [62] (Fig. 1). These studies established B cells as professional antigen presenting cells, thus revealing one of the many mechanisms by which these lymphocytes can influence T cell responses [48, 63]. Antigen-specific B cells are capable of presenting antigens to T cells with exceptionally high efficiency by capturing and internalizing antigens via surface immunoglobulins; these antigens are then processed and presented on the surface as peptide:MHC class II complexes [63, 73–75]. While It is generally believed that dendritic cells are the most efficient antigen presenting cell subset for priming na CD4+ T cells [76–78], ample evidence, derived from mouse models, supports a role for B cells as effective antigen presenting cells that participate in T cell priming [79–81]; and it has been reported that B cells have the ability to prime na CD4+ T cells in the absence of other competent antigen presenting cells [82]. A role for B cells in priming na T cells by virtue of their ability to present antigens is, however, not uniformly observed—this inconsistency suggests that the significance of this function of B cells in T cell priming likely depends on antigen types and specific immunological conditions [83]. The observation that B cells in lymph node follicles acquire injected soluble antigens within minutes post-inoculation strongly suggests the B cells have the ability to participate in early events of an immune response including antigen presentation and priming of T cells [63, 84, 85].

Vaccination strategies have exploited the potential antigen-presenting property of B cells for T cell activation [86, 87]: indeed, one such scheme has been shown to be effective in boosting BCG primed immunity against M. tuberculosis [88]. Data derived from a chronic virus infection model suggest that B cells can protect against disease reactivation through antigen presentation to T cells [89]. Activated B cells as antigen-presenting cells have been exploited to augment anti-tumor immunity [90]. The antigen-presenting property of activated B cells has been linked to the perpetuation of autoimmunity [91]; by contrast, resting B cells are noted for their ability to induce immune tolerance [92, 93]. Thus, it appears possible to target the antigen-presenting property of B cells to augment specific immune response as well as to suppress autoimmunity [94]. Accumulating evidence indicate that B cells regulate T cell proliferation early on in response to antigens, and affect the subsequent development of T cell memory responses [48, 63, 95]. In infectious diseases models, it has been observed that B cells are required for the development of memory T cell response to intracellular pathogens such as F. tularensis and Listeria monocytogenes [49, 54]. These observations underscore the importance of going beyond the concept of niche-based division of labor of cellular and humoral immunity in vaccine design to include strategies that target both arms of the immune response.

Priming of T cells to clonally expand requires two signals [96, 97]. The first is provided through the engagement of T cell receptor and with peptide:MHC complex of antigen presenting cells. The second signals derive from interaction of co-stimulatory molecules on the surface of T cells (such as CD28) and antigen presenting cells (such as the B7 family proteins) [98]. The two signals combine to initiate the adaptive immune response. Absence of the second signal results in tolerance [97]. During the innate phase of the immune response, antigen presenting cells, destined to prime T cells to initiate the development of adaptive immunity, undergo maturation and upregulate the expression of surface co-stimulatory molecules [99]. By virtue of their ability to produce antibodies and cytokines, B cells can modulate the maturation process of antigen presenting cells, thereby regulating the ensuing adaptive immune response [100–105]. Natural antibodies can bind to and alter the activity of the costimulatory molecules B7 and CD40, thereby affecting the antigen presentation process [106, 107]. Finally, cytokines produced by B cells can polarize T cell responses [108]; for example, it has been shown that IL-10 produced by B cells in mice can promote a Th2 response [109].

Cytokine production

The composition of the immunological environment in which na CD4+ T cells interact with antigen presenting cells to clonally expand plays a critical role in determining the path of lineage development [110]. The cytokine milieu at the site of T cell-antigen presenting cell interaction strongly influences CD4+ T cell development. B cells produce a wide variety of cytokines either constitutively or in the presence of antigens, Toll-like receptor ligands, or T cells [108, 111–113]. Based on the pattern of cytokines they produce, B cells have been classified into different effector subsets: B effector-1 (Be1), B effector-2 (Be2), and regulatory B10 cells [48, 108, 113, 114]. During their initial interaction with T cells and antigen, B cells primed in a Th1 cytokine environment become an effector cell subset (Be1) that produces interferon (IFN)-γ and interleukin (IL)-12, as well as TNF, IL-10, and IL-6. B cells primed in the presence of Th2 cytokines produce IL-2, lymphotoxin, IL-4, and IL-13 and can secrete TNF, IL-10, and IL-6 as well [48, 108, 113–115]; these are designated the Be2 subset. Through differential cytokine production, these B cell effector subsets can influence the development of the T cell response. Thus, Be1 and Be2 cells can bias the differentiation of na CD4+ T cells into Th1 and Th2 effector T cells, respectively [57, 108]. Studies looking at cytokine production by human B cells have shown that B cells that produce IL-12 can stimulate a Th1 response in vitro [116], and, in contrast, B cells that produce IL-4 stimulate a Th2 response [117]. The ability of B cell-derived cytokines, notably IFNγ and IL-10 to regulate T cell differentiation provides a cross-regulatory link between B and T cells [108, 113, 115]. In a murine infectious disease model of Heligomosomoides polygyrus, a rodent intestinal parasite, it has been shown that B cells regulate both the humoral and cellular immune response to this nematode in multiple ways, including the production of antibodies, presentation of antigens, and the secretion of specific cytokines [57]. Cytokine-producing effector B cells are required for protection against H. polygyrus. Specifically, B cell-derived TNF is required for sustained antibody production and IL-2 is essential for Th2 cell expansion and differentiation [57]. In addition, the data revealed that specific functions of B cells might affect one particular phase of the immune response and not others [57]. This is a most comprehensive study designed to characterize the role of various effector functions of B cells modulating the development of the host response to a pathogen, providing compelling evidence to support a complex role for B cells during infection [57] (Fig. 1). We have recently observed that B cells immunomagnetically procured from lungs of M. tuberculosis-infected mice produce a variety of cytokines (L. Kozakiewicz and J Chan, unpublished). The functions of these B cell-derived cytokines in TB remain to be evaluated.

It is clear from the above discussion that the ability of B cells to augment T cell immunity plays an important in the development of immune responses. Equally important is the ability of B cells to negatively affect T cell responses by a subset termed regulatory B cells [48, 114, 118]. Critical to this regulatory effect is the production of IL-10 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β by this B cell subset [48, 114, 118]. These B cells downregulate T cell function either directly via IL-10 or TGF-β production or by augmentation of the regulatory T cell pathway [48, 114, 118]. Importantly, the regulatory B cells have been shown to play a role in the control of autoimmunity, inflammation, and cancer. Whether regulatory B cells modulate the development of immune responses to M. tuberculosis is currently unknown.

Fcγ receptor (FcγR) engagement

A most studied area of humoral immunity is perhaps the mechanisms by which antibodies regulate antigen-presentation through engagement of FcγR by antigen–antibody complexes [119]. The FcγR-immune complex engagement has been an area of active investigation for the development of vaccines against intracellular pathogens [58]. This interaction could be via engagement of the complex with stimulatory and/or inhibitory FcγRs, whose functions are determined by the presence of ITAM or ITIM motifs in the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor, respectively [120, 121]. Engagement of FcγRIIB, the sole inhibitory Fcγ receptor, negatively influences T cell activation by attenuating the process of dendritic cell maturation and subsequent antigen-presentation; interaction through the stimulatory FcγR’s promotes both processes [101, 104]. The inhibitory property of FcγRIIB bestows upon this receptor a significant role in mediating peripheral T cell tolerance [122]. In murine models, blockade of FcγRIIB results in enhancement of T cell anti-tumor activity [100, 101, 104]. By contrast, the stimulatory FcγRs promote the development of Th1 or Th2 T cell response, the polarization direction being determined by the in situ inflammatory environment [123].

Due to the preferential engagement of specific immunoglobulin subclasses to FcγR [124], immunization protocols can be rationally designed to target stimulatory receptors to enhance cellular immunity against intracellular pathogens [58, 125]. Interestingly, the ITAM-containing FcγRIII exhibits immune suppressive effects in an IVIG model, suggesting that the ensuing inflammatory response upon engagement of FcγR is complex [126]. The availability of specific FcγR-deficient mouse strains has facilitated the evaluation of the importance of these receptors in various infectious disease models [127]. Disruption of the shared stimulatory Fcγ-chain results in suboptimal immune response to a variety of intracellular pathogens such as influenza virus, Leishmania species, Plasmodium berghei, and S. enterica [37, 128–132]. Passive immunization using IgG1 monoclonal antibodies against Cryptococcus neoformans requires functional stimulatory FcγR’s [133]. These observations implicate the stimulatory FcγR in cellular defense against intracellular pathogens. We have recently shown that signaling through FcγRs can modulate immune responses to M. tuberculosis [134]. Together, these data suggest the possibility of enhancing efficacy of vaccines against intracellular pathogens by targeting specific FcγRs [58, 125]. Indeed, it has been proposed that recombinant Sindbis virus-based vectors engineered to target FcγR-bearing cells through expression of a bacterial component that bind the variable region of the kappa light chain, coupled with antibody-dependent infection enhancement, can be exploited to manipulate antigen-presenting cells for activation and immunization [135]. In mice, the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein MSP2 harbors a T cell epitope that can be exploited to preferentially induce isotype class-switching to IgG2b [116], a cytophilic immunoglobulin subclass with preferential affinity for stimulatory FcγRs [124].

4 B Cell Regulation of Effector Cells: The Influence on Macrophages

The distinct effector B cell subsets described earlier can polarize T cell development [48, 108, 111, 112]. Emerging evidence indicate that macrophages exist in distinct subsets with characteristic immunological functions [136, 137]. In mice, macrophages with the alternatively activated phenotype (M2) are conducive to persistence of certain pathogens [138] and contribute to the progression of tumor [139, 140]. The differentiation of macrophages into specific subsets can be modulated by B cells. For example, B1 cells have been shown to promote the polarization of macrophages into the M2 subset, with unique phenotypes characterized by upregulation of LPS-induced IL-10 production, downregulation of LPS-induced production of TNF, IL1β, and CCL3, and the expression of typical M2 markers including Ym1 and Fizz1 [141]. IL-10 plays a major role in promoting M2 polarization [141]. The significance of the B1 cell-mediated M2 polarization has been shown in a melanoma tumor model [141], providing evidence supporting the in vivo relevance of the ability of B cells to modulate macrophage functions. As macrophages are a major host cell for M. tuberculosis, and exist in close proximity to B cells in tuberculous granulomas [142], it is possible that B cells can affect the immune response to the tubercle bacillus by regulating macrophage functions.

The significance of the interaction by immune complex with FcγRs in modulating immune responses has been well established (discussed in previous section). One outcome of this interaction, as illustrated in a Leishmania infection model, is that ligation of FcγR with antibody-coated parasites leads to enhanced IL-10 and decreased IL-12 production by macrophages [143], thereby providing a cellular niche that allows leishmanial growth. This phenomenon is termed “antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) of microbial infection” [144]. The ADE phenomenon, originally observed with viral pathogens, can be dependent on the nature of the immune complex [145]. In M. tuberculosis infection, mice infected with monoclonal antibodies-coated bacilli exhibited improved disease outcome relative to those infected with uncoated organisms [146]. Further, the FcγRIIB-deficient strain, compared to wild-type mice, displays enhanced ability to control M. tuberculosis infection [134]. In addition, although immune complex engagement of activating FcγR has been reported to be a major mechanism underlying IL-10 enhancing ADE, we have observed that immune complex-treated M. tuberculosis-infected FcγRIIB KO macrophages produce enhanced IL-12p40 [134]. These data suggest that ADE may not be operative in vivo during M. tuberculosis infection. The precise mechanisms by which mycobacteria-IgG antibody complexes modulate disease outcome during M. tuberculosis infection in mice remain to be characterized. It is perhaps most appropriate to study such mechanisms in non-human primates, a species whose granulomas closely resemble the structure of that in humans, given the predicted relevance of the nature of the in situ conditions (the granuloma) in which IgG interacts with M. tuberculosis and/or its antigens (this issue will be discussed below). In sum, it is becoming clear that B cells can modulate macrophage functions through the production of antibodies and cytokines. In addition, B cells can indirectly influence macrophage biology through its ability to modulate T cell functions. Gaining insights into how B cells regulate macrophage functions in the course of M. tuberculosis infection should further illuminate the mechanisms underlying the immune responses to this pathogen.

5 Are Antibodies Effective in Defense Against M. tuberculosis?

Despite reports since the late nineteenth century that serum therapy can be effective against tuberculous infection, humoral immunity is generally considered insignificant in contributing to the immune response against the tubercle bacillus [20]. The latter notion derives from the inconsistent efficacy of passive immune therapy [20, 147], the discovery of effective anti-mycobacterial drug therapies in the mid-twentieth century [148], as well as the concept of the division of labor between humoral and cellular immunity in the control, respectively, of extracellular versus intracellular pathogens [19, 28, 29]. The history and the development of antibody-mediated immunity to M. tuberculosis have been discussed recently in excellent reviews [20, 149].

Accumulating evidence suggests a significant role for antibody-mediated response to intracellular pathogens [19, 21, 48]. Indeed, monoclonal antibodies specific for a number of mycobacterial components including arabinomannan, lipoarabinomannan, heparin-binding hemagglutinin and 16 kDa α-crystallin, have been shown to protect mice against M. tuberculosis to varying degrees [146, 150–153]. The protective effects of these antibodies manifest as either decreased in tissue mycobacterial loads or alteration of the inflammatory response [149]. Of note, serum therapy using polyclonal antibodies against M. tuberculosis is effective in protection against relapse of infection in SCID mice after treatment with anti-tuberculous drugs [154]. In addition, protective effects of IVIG in a mouse model of tuberculosis further suggest that humoral immune response contribute to the development of anti-tuberculous immunity in TB [155]. However, a vaccine comprising an M. tuberculosis arabinomannan–protein conjugate, while engendering an antibody response superior to that elicited by BCG in mice, was ineffective in improving survival of challenged animals [156]. These apparently discrepant results with regard to the significance of the humoral immune response in defense against M. tuberculosis can be due to multiple factors. First, the multifunctionality of B cells and humoral immunity predicts that analysis of this arm of the immune response is likely not straightforward. Second, the mouse may not be the most suitable species for these studies because of the dissimilarities of granulomatous response in this species and humans [157, 158], and because of the fact that anti-tuberculous responses in the mouse appears to be more robust than is needed for effective control of the infection [157]. This overly robust resistance of the mouse to M. tuberculosis could mask the significance of certain immunological factors that otherwise contribute substantially to defense against this pathogen. Demonstration of a correlation between antibody response and protection in human tuberculosis and in animal models should afford novel in vivo systems in which anti-TB vaccines that are based on B cells and humoral immunity can be effectively tested. Finally, a component of humoral immunity that has hardly been evaluated during tuberculous infection is the innate or natural antibody responses [159–161]. Given that complex lipids and polysaccharides constitute a major components of the M. tuberculosis cell envelope, the significance of T-independent antibody responses mediated by B1 and marginal zone B cells in defense against M. tuberculosis warrants examination [160–164].

Antibody-mediated immunity can shape the host response to pathogens in a number of ways (Fig. 1). These include antigen-specific neutralization, regulation of the inflammatory reaction through complement activation, FcγR cross-linking, release of microbial products due to direct anti-microbial activity, and impact on microbial gene expression upon binding of the organisms [19, 29]. Relevant to the local lung immune response during tuberculous infection, antibodies have been shown in a mycoplasma model to be able to modulate architectural changes in airway epithelium and vessels [165]. We have shown that adoptive transfer of B cells ameliorates the enhanced inflammatory response observed in B cell-deficient mice upon airborne challenge with virulent M. tuberculosis [166]. This B cell-mediated attenuation of exacerbated inflammatory response is associated with detectable levels of immunoglobulins in the recipient B cell-deficient mice but does not require the presence of B cell locally in the infected lungs [166], suggesting a role for immunoglobulin-mediated endocrine immune regulation during M. tuberculosis infection. It is thus apparent that antibodies, in addition to neutralizing and opsonizing microbes, can also be protective during microbial challenge by limiting inflammatory pathology [19, 29], the latter a well established function of immunoglobulins [167].

6 The Role of B Cells in the Development of the Immune Response to M. tuberculosis

Successful rational design of effective vaccines against M. tuberculosis has been hampered by the lack of definitive immunological correlates of protection, although strong evidence supports an important role for T cell-mediated responses in eliciting protective immunity [11]. As a result, TB vaccine development has focused predominantly on enhancing cellular immune responses against M. tuberculosis [12, 17]. A recent failed T cell vaccine trial against HIV should, however, caution against taking too narrow an approach in vaccine design [168]. Thus, it is possible that eliciting protective antibody responses may be required for successful immunization against M. tuberculosis [18]. Research effort directed at revealing how humoral immunity can be harnessed to enable protection against the tubercle bacillus is needed. Being that B cells are multifunctional, the mechanisms underlying how these lymphocytes modulate the immune response to M. tuberculosis are likely complex. For example, immunoglobulins, acting upon FcγRs, can influence the maturation process and functions of antigen-presenting cells, whose role in T cell activation and development has been well established [96, 97, 99]. B cells can conceivably shape anti-tuberculous immunity through direct effects of antibody on the pathogen, antigen-presentation, production of cytokines at the site of infection and by modulating intracellular killing mechanisms of leukocytes (Fig. 1).

B cell-deficient mice infected aerogenically with M. tuberculosis, compared to the parental wild-type C57BL/6 strain, display suboptimal defense against the pathogen (as assessed by tissue bacterial burden and mortality), as well as enhanced lung IL-10 expression, neutrophil infiltration, and inflammation [166]. These B cell-deficiency phenotypes are all reversible by adoptive transfer of B cells from M. tuberculosis-infected wild-type mice [166]. We have also shown that mice deficient in the inhibitory FcγRIIB are more resistant to M. tuberculosis compared to wildtype controls [134], with enhanced pulmonary Th1 responses, evidenced by increased IFNγ+ CD4+ T cells. Upon M. tuberculosis infection and immune complexes engagement, FcγRIIB−/− macrophages produced more p40 component of IL-12, a Th1-promoting cytokine. These data suggest that FcγRIIB signaling can dampen the Th1 response to M. tuberculosis, at least partially by attenuating IL-12 production, and that B cells can regulate CD4 Th1 response in acute TB through engagement of FcγRs by immune complexes. In contrast to the FcγRIIB−/− strain, mice lacking the common γ-chain of activating FcγRs are more susceptible to low dose M. tuberculosis infection with exacerbated immunopathology, increased mortality, and enhanced production of IL-10 [134]. These observations suggest that antibodies can significantly modulate host immune responses by mediating antigen–antibody complex engagement of FcγRs during M. tuberculosis infection. In addition, the data indicate that signaling through specific FcγRs can divergently affect disease outcome, suggesting that it is possible to enhance anti-mycobacterial immunity by targeting FcγRs.

In two different murine TB models involving mice with B cell deficiency, we and others have provided evidence that B cells can regulate IL-10 production in the lungs of M. tuberculosis- infected mice [166, 169]. We have also observed enhanced lung cell production of IL-10 in M. tuberculosis-infected mice deficient in the common γ chain of stimulatory FcγRs [134]. A wide variety of immune cells—B-cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and T cells—produce IL-10, whose anti-inflammatory functions have been well recognized [170]. The cellular source of this IL-10 increase remains to be determined. A feature of incompletely activated dendritic cells that have not undergone full maturation is IL-10 production [171]. Therefore, it is possible that B cells may indirectly influence the production of IL-10 by antigen-presenting cells through modulation of cellular activation via immune complex engagement of FcγRs. B cells can also activate or inhibit regulatory T cells, a significant cellular source of IL-10 [172, 173]. IL-10 has been reported to adversely affect disease outcome in murine TB [174]. It is possible that excess IL-10 production observed in the B cell- and γ chain-deficient mice can contribute to the inability of these strains to optimally control M. tuberculosis infection [134, 166]. Finally, this increased production of IL-10 may be a compensatory mechanism to counter the exacerbated immunopathology that develops in M. tuberculosis-infected B cell−/− and Fcγ-chain−/− mice [134, 166]. Much work needs to be done to characterize the mechanisms by which B cells and humoral immunity regulate the production of cytokines in general, and IL-10 in particular, at the site of tuberculous infection. The regulatory mechanisms are likely to be complex given the multiple immunological functions of B cells, which include the production of a wide variety of cytokines including IFN-γ [108], a critical anti-mycobacterial factor; and IL-10, which has been shown to attenuate resistance in murine TB [174].

As discussed in the previous sections, it is clear that the interaction of immune complexes with FcγRs plays an important role in immune regulation [120, 121]. Our FcγR knockout mouse studies suggest that the interaction of FcγRs with immune complexes during the course of M. tuberculosis infection can influence disease outcome [134]. The precise mechanisms by which this interaction modulates the infection in mice remain to be defined. Gallo et al. [175] has suggested a mechanism of regulation of macrophage FcγR signaling upon interaction with antibody–antigen immune complexes that might be pertinent during M. tuberculosis infection in humans or a species granuloma structure resembles that of humans. This mechanism proposes that macrophage FcγR signaling depends on the density of IgG within the immune complex. Immune complexes with high IgG densities promote anti-inflammatory responses, particularly the release of IL-10, while that of moderate densities tend to induce pro-inflammatory cytokine release by macrophages. The FcγR signaling pathway in a cell depends on cell surface receptor recruitment and cross-linking by the antigen–antibody immune complexes. The summation of FcγR members recruited and cross-linked is then translated as an inhibitory or activating signal to the cell. Whether the density of IgG within immune complexes can determine the recruitment of activating versus inhibitory class of receptors, a potential mechanism underlying the IgG density phenomenon, is presently unknown. The macrophage population is unique as these cells express both the inhibitory and activating forms of FcγR, although there may be different ratios on the various types of differentiated macrophages that exist in the granuloma [176, 177]. Furthermore, the ratio of expression of inhibitory and activating FcγR can be influenced by the cytokine environment [177, 178]. Thus, macrophage behavior can become highly versatile depending on the composition of the immune complex.

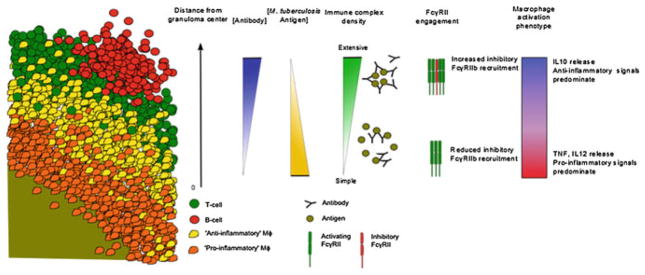

The formation of immune complexes depends on the concentration of antigen and antibody. Conditions that favor the formation of complexes with high IgG densities can potentially direct macrophages to produce IL-10. Considering that M. tuberculosis bacilli are theoretically confined towards the center of a granuloma, antigen concentration would be the highest at the granuloma center and decrease towards the periphery (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, B cells and plasma cells are confined at the periphery meaning that antibody concentration should be highest at the lymphocytic cuff and lowest in the center (Fig. 3). Along this antibody–antigen gradient, we hypothesize that the immune complexes that form would have different in IgG densities and would signal the macrophage to behave differently. Thus, macrophages closest to the granuloma center would encounter immune complexes with lower IgG densities and can be predicted to be more pro-inflammatory than macrophages at the periphery, whose interaction with immune complexes with high IgG densities should result in the production of IL-10 (Fig. 3).

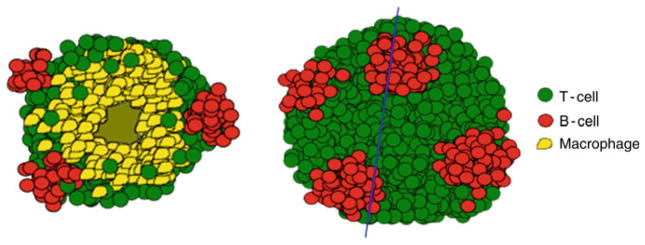

Fig. 2.

A schematic representation of a granuloma showing how the B cell clusters (red) would be organized with respect to macrophages (yellow) and T-cells (green). The blue line denotes the cross-sectional area. B cell clusters would be located within the lymphocytic cuff on the surface of the granuloma analogous the black spots on a white soccer ball

Fig. 3.

The proposed mechanism of how antibody–antigen immune complexes can influence macrophage activation phenotypes with respect to distance from the granuloma center, antibody and antigen concentration, immune complex composition, and inhibitory receptor recruitment. A segment of a granuloma cross-section is used to illustrate how the proposed mechanism of immune complex interaction with macrophages would result in different modes of activation

Given the highly stratified nature of the non-human primate and human granuloma, which is much different from the murine granuloma, B cells together with antibody production and immune complex formation may orchestrate targeted responses locally within specific regions of the granuloma (Figs. 2 and 3). Hence, antibody-mediated signaling would theoretically contribute towards control of M. tuberculosis by confining pro-inflammatory responses towards the center of the granuloma and thus increase bacterial killing. At the same time, bystander tissue damage at the peripheral areas of the granuloma is reduced as anti-inflammatory responses are dominant. Since control of M. tuberculosis relies on adequate balancing of pro- and anti-inflammatory responses within the granuloma, the proposed mechanism of how the humoral immune system influences macrophage function can possibly explain how such balance is achieved within the granuloma to realize disease resolution. Associated scenarios where inadequate control of disease occurs due to excess antibody responses or even treatment can potentially be addressed. The validity of the model requires a highly organized stratified granulomatous structure that exists in humans and non-human primates but not in the mouse. Verification of this model in non-human primates should underscore the importance of the choice of animal models in the study of TB.

An important aspect we would like to address before leaving this section is the effect of B cells and humoral immunity on the development of immunopathology in the course of M. tuberculosis infection. In the absence of B cells, mice with acute M. tuberculosis infection exhibit suboptimal anti-tuberculous immunity associated with exacerbated pulmonary pathology [166]. In a similar mouse model (albeit using a different strain of M. tuberculosis), it was observed that B cell-deficiency resulted in a delay in inflammatory progression during the chronic phase of tuberculous infection [179]. This paradox suggests that B cell functions during the course of TB are infection phase-specific: In acute infection, B cells are required for an optimal granulomatous response and effective immunity against M. tuberculosis aerosol infection; deficiency of these lymphocytes leads to dysregulation of granuloma formation and increased pulmonary inflammation is required to contain the growth of tubercle bacilli. In contrast, in the chronic phase of infection, the immunologically active B cell aggregates [54, 61, 62] (see below) likely play a role in promoting the perpetuation of effective local immunity so as to contain persistent bacilli and prevent disease reactivation. It is possible that a trade-off for the perpetuation of this local control of M. tuberculosis is the development of tissue-damaging immunopathology. As T cells exist within the B cell aggregates in the tuberculous lungs of both human and mice ([142], P. Maglione and J. Chan, unpublished), the perpetuation of inflammation in chronic TB may occur in part through B cells acting as antigen-presenting cells. Thus, the inflammatory paradox observed in B cell-deficient mice may be due to the role of B cells shifting from optimizing host defense during acute challenge to perpetuating the potentially tissue-damaging chronic inflammatory response during persistent infection.

For those most severely affected by TB, morbidity and mortality of the infection is, at least in part, the result of a tissue-damaging host response [28, 180]: one with an excessive pathologic inflammatory reaction yet ultimately is ineffective in controlling the pathogen. Such an outcome may be due to an ineffective immune containment of the tubercle bacillus leading to excessive compensatory recruitment of leukocytes into the site of infection in the lungs. This is perhaps best exemplified in patients with reactivation TB. By mechanisms yet poorly defined, dormant bacilli reactivate to cause diseases that are associated with areas of intense pulmonary infiltrate [180]. In the active cases, neutrophils can be a dominant cell type in tuberculous pulmonary infiltrates [181]. The neutrophil is generally considered to be an innate immune cell that mediates early protection but can induce inflammatory damage in a variety of acute pulmonary diseases [182]. In mice, as in humans, susceptibility phenotype to M. tuberculosis is often associated an enhanced neutrophilic response [183]. Clearly, severe tissue-damaging host response can be observed in certain hosts in TB, however, the restricted Ghon complex pathology in humans indicate that successful containment of the tubercle bacillus needs not be associated with significant immunopathology. Emerging experimental results strongly suggest that B cells and humoral immunity may play a role in modulating the inflammatory response in TB [166, 179], and that this B cell-based modulation may be infection phase specific.

7 B Cells in Germinal Center-Like Structures in the Tuberculous Granuloma

B cells are a prominent component of the tuberculous granulomatous inflammation in the lungs of mice [142, 184], non-human primates (Y. Phuah and J. Flynn, unpublished) and human [142, 181], forming conspicuous aggregates. In the lungs of humans with TB, cellular proliferation is detected primarily in these B cell aggregates [181]. The B cell nodules are also characteristics of the progression of tuberculous granulomatous inflammation [142, 184, 185]. B cell nodules have been observed in many chronic inflammatory diseases such as multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis [186, 187]. Similar to TB, B cell clusters have been observed at the site of infection caused by a number of microbes such as influenza virus and Helicobacter [188, 189]. The ability of certain pathogens to promote expansion and inhibit apoptosis of B cells may contribute to the existence of aggregates of these lymphocytes during infection [190, 191].

The granulomas formed in M. tuberculosis-infected non-human primates are highly stratified, and represent the full range of granuloma types seen in humans [192, 193] (Figs. 2 and 3). The granuloma center generally contains the infected macrophages and can be cellular, infiltrated with neutrophils, necrotic with caseous cellular debris, or mineralized. Surrounding the granuloma center is a layer of epithelioid macrophages, which is in turn surrounded by a layer of lymphocytes interspersed with macrophages. Both T and B cells are found within the lymphocytic cuff of the granuloma but whereas the CD3+ T cells are generally homogenously spread throughout the cuff, the B cells are present in very discrete clusters (J. Phuah and J. Flynn, unpublished). These B cell clusters sit on the surface of the granuloma and are spaced away from other B clusters. A close analogy in the positioning of these B cell clusters would be like the black spots on a white soccer ball. Unlike T-cells, which can be seen infiltrating into the granuloma beyond the lymphocytic cuff, B cells are confined within the lymphocytic cuff (Fig. 2).

What are the effects of these ectopic B cell nodules on the local lung immune response in a tuberculous host? TB is a chronic condition that once established requires a long time to be successfully contained and resolved. It is possible that by forming these germinal centers in situ of the granuloma, antigen presentation and lymphocyte activation can occur with greater efficiency. The localization of cellular proliferation in the proximity of these B cell aggregates has led to the hypothesis that these structures function to perpetuate local host responses [181]. As discussed above, perpetuation of these local immune responses by the granulomatous B cell aggregates could contribute to the development of tissue-damaging immunopathology. T cells have been observed embedded within these B cell clusters [142], suggesting the possibility that antigen-presentation and B-cell maturation can occur in these aggregates. Indeed, experimental evidence suggests that the B-cell aggregates observed in tuberculous lungs represent tertiary lymphoid tissues [194], displaying cellular markers typical of germinal centers [166]. Our observation that B cell-deficient mice exhibit aberrant granulomatous reaction with exacerbated pulmonary pathology suggests that the B-cell aggregates may regulate the local lung immune response [166]. It has been reported that in the absence of secondary lymphoid organs, in situ lymphoid nodules can prime protective immunity in the lungs and memory responses against pulmonary influenza virus challenge [188, 195]. The significance of lymphoid neogenesis in the regulation of immune responses in TB remains to be defined.

8 Concluding Remarks

Only 10 % of those infected with M. tuberculosis develop disease; the remainder can apparently contain the infection without symptoms. Individuals in this latter group, generally thought to harbor dormant bacilli, run a 10 % lifetime risk of subsequent reactivation of the infection, often as a result of acquired immunodeficiency [11]. These epidemiological data attest to the tenacity of M. tuberculosis: this pathogen is well-adapted to persist even in a host that can mount a disease-preventing immunity. This, together with the occurrence of exogenous reinfection in a previously infected host, suggests that effective preventive TB vaccines must elicit an immune response superior to that induced by natural infection [18]. This is a daunting task, and implies that rational design of effective vaccines should perhaps take a more comprehensive approach, going beyond the T cell-focused strategy to characterize the protective immunity in TB. In this respect, the vaccine effort may benefit from gaining insight into immune mechanisms that may not be immediately obvious in engendering major protection during natural infection, and how such pathways can be harnessed to optimize immunization protocols. One such pathway is the understudied B cell and humoral immunity. It is clear, as discussed in this review, that B cells and humoral immunity have a significant effect on the development of immune response against M. tuberculosis. How the B cell-mediated immunological pathways modulate the immune response to M. tuberculosis is just beginning to be understood and much remains to be learnt. For example, what are the mechanisms by which B cells regulate anti-mycobacterial T cell responses? What is the nature of the B cell memory that develops upon BCG vaccination or natural M. tuberculosis infection (are they one and the same?), and does it contribute to protection upon secondary challenge? Are there memory B cells that are specific for T-independent non-protein M. tuberculosis antigens (this is of relevance given the chemical composition of the mycobacterial cell envelop)? Are such antigens viable vaccine targets? What roles do natural antibodies play in defense against M. tuberculosis and can this pathway be a target for effective vaccines? Do protective antibodies against the tubercle bacillus exist and if so, how can they be targeted to develop more effective vaccines? What are the functions of the germinal center-like B cell clusters in the lungs of a chronically infected host—do they play a role in orchestrating local containment of M. tuberculosis or in the development of tissue-damaging immunopathology or both? If they do serve such functions, can B cells be manipulated to prevent reactivation and/or to ameliorate immunopathology (the latter an important means to prevent dissemination of infection)? Finally, are there B cell responses that adversely affect anti-TB immunity? Answers to these questions should illuminate the roles of B cells and humoral immune responses in TB. These will ultimately help develop strategies by which the humoral arm of immunity can be harnessed to optimize immune responses against M. tuberculosis. Given the global public burden of TB, it is not unreasonable to take a comprehensive approach to explore all possibilities that may lead to the development of novel TB control measures including vaccines. For decades, B cells have been relegated toward irrelevance in immune responses to M. tuberculosis, recent studies have provided evidence to suggest otherwise. Revisiting the role of B cells in anti-TB immunity may lead to better understanding of the mechanisms underlying the host response to M. tuberculosis infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grants R01 AI094745, R01 AI098925, R01 AI50732, R01 HL106804, P01 AI063537, P30 AI051519 (The Einstein/Montefiore Center for AIDS Research), and T32 AI070117 (The Einstein Geographic Medicine and Emerging Infections Training Grant) and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. We thank the members of the Chan and Flynn laboratories for helpful discussion.

Contributor Information

Lee Kozakiewicz, Departments of Medicine and Microbiology and Immunology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Jack and Pearl Resnick Campus, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Forchheimer Building, Room 406, Bronx, NY 10461, USA.

Jiayao Phuah, Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, Center for Vaccine Research, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

JoAnne Flynn, Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, Center for Vaccine Research, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

John Chan, Email: john.chan@einstein.yu.edu, Departments of Medicine and Microbiology and Immunology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Jack and Pearl Resnick Campus, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Forchheimer Building, Room 406, Bronx, NY 10461, USA.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control: epidemiology, strategy, financing. WHO Report. 2009;2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flynn JL, Chan J. Immune evasion by Mycobacterium tuberculosis: living with the enemy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15(4):450–455. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper AM. Cell-mediated immune responses in tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol X. 2003;27:393–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.North RJ, Jung YJ. Immunity to tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:599–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufmann SH. Protection against tuberculosis: cytokines, T cells, and macrophages. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(suppl 2):ii54–ii58. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.suppl_2.ii54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sperber SJ, Gornish N. Reactivation of tuberculosis during therapy with corticosteroids. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15(6):1073–1074. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.6.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keane J, et al. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(15):1098–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selwyn PA, et al. A prospective study of the risk of tuberculosis among intravenous drug users with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(9):545–550. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198903023200901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flynn JL. Immunology of tuberculosis and implications in vaccine development. Tuberculosis. 2004;84(1–2):93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dye C. Doomsday postponed? Preventing and reversing epidemics of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(1):81–87. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flynn JL, Chan J. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:93–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaufmann SH. Future vaccination strategies against tuberculosis: thinking outside the box. Immunity. 2010;33(4):567–577. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaufmann SH. How can immunology contribute to the control of tuberculosis? Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1(1):20–30. doi: 10.1038/35095558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colditz GA, et al. Efficacy of BCG vaccine in the prevention of tuberculosis. Meta-analysis of the published literature. J Am Med Assoc. 1994;271(9):698–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corbett EL, et al. The growing burden of tuberculosis: global trends and interactions with the HIV epidemic. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(9):1009–1021. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.9.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dye C, et al. Consensus statement. Global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. WHO Global Surveillance and Monitoring Project. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282(7):677–686. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersen P. Tuberculosis vaccines—an update. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5(7):484–487. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaufmann SH. The contribution of immunology to the rational design of novel antibacterial vaccines. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5(7):491–504. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. A new synthesis for antibody-mediated immunity. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(1):21–82. doi: 10.1038/ni.2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glatman-Freedman A, Casadevall A. Serum therapy for tuberculosis revisited: reappraisal of the role of antibody-mediated immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11(3):514–532. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maglione PJ, Chan J. How B cells shape the immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(3):676–686. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumararatne DS. Tuberculosis and immunodeficiency of mice and men. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;107(1):11–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.d01-910.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufmann SH. Elie Metchnikoff’s and Paul Ehrlich’s impact on infection biology. Microbes Infect/Institut Pasteur. 2008;10(14–15):1417–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silverstein AM. Darwinism and immunology: from Metchnikoff to Burnet. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(1):3–6. doi: 10.1038/ni0103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan SY, Dee MK. Elie Metchnikoff (1845–1916): discoverer of phagocytosis. Singap Med J. 2009;50(5):456–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins FM. Cellular antimicrobial immunity. CRC Crit Rev Microbiol. 1978;7(1):27–91. doi: 10.3109/10408417909101177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackaness GB. Cellular resistance to infection. J Exp Med. 1962;116:381–406. doi: 10.1084/jem.116.3.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casadevall A. Antibody-mediated immunity against intracellular pathogens: two-dimensional thinking comes full circle. Infect Immun. 2003;71(8):4225–4228. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4225-4228.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. A reappraisal of humoral immunity based on mechanisms of antibody-mediated protection against intracellular pathogens. Adv Immunol. 2006;91:1–44. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)91001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pulendran B, Ahmed R. Immunological mechanisms of vaccination. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(6):509–517. doi: 10.1038/ni.2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seder RA, Hill AV. Vaccines against intracellular infections requiring cellular immunity. Nature. 2000;406(6797):793–798. doi: 10.1038/35021239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Culkin SJ, Rhinehart-Jones T, Elkins KL. A novel role for B cells in early protective immunity to an intracellular pathogen, Francisella tularensis strain LVS. J Immunol. 1997;158(7):3277–3284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langhorne J, et al. A role for B cells in the development of T cell helper function in a malaria infection in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(4):1730–1734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li JS, Winslow GM. Survival, replication, and antibody susceptibility of Ehrlichia chaffeensis outside of host cells. Infect Immun. 2003;71(8):4229–4237. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4229-4237.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mastroeni P, et al. Igh-6(−/−) (B-cell-deficient) mice fail to mount solid acquired resistance to oral challenge with virulent Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium and show impaired Th1 T-cell responses to Salmonella antigens. Infect Immun. 2000;68(1):46–53. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.46-53.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su H, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection of antibody-deficient gene knockout mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65(6):1993–1999. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.1993-1999.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woelbing F, et al. Uptake of Leishmania major by dendritic cells is mediated by Fcgamma receptors and facilitates acquisition of protective immunity. J Exp Med. 2006;203(1):177–188. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang X, Brunham RC. Gene knockout B cell-deficient mice demonstrate that B cells play an important role in the initiation of T cell responses to Chlamydia trachomatis (mouse pneumonitis) lung infection. J Immunol. 1998;161(3):1439–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grosset J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the extracellular compartment: an underestimated adversary. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(3):833–836. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.3.833-836.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoff DR, et al. Location of intra- and extracellular M. tuberculosis populations in lungs of mice and guinea pigs during disease progression and after drug treatment. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(3):e17550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wayne LG, Sohaskey CD. Nonreplicating persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:139–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujinami RS, Oldstone MB. Antiviral antibody reacting on the plasma membrane alters measles virus expression inside the cell. Nature. 1979;279(5713):529–530. doi: 10.1038/279529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Griffin DE, Metcalf T. Clearance of virus infection from the CNS. Curr Opin Virol. 2011;1(3):216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Metcalf TU, Griffin DE. Alphavirus-induced encephalomyelitis: antibody-secreting cells and viral clearance from the nervous system. J Virol. 2011;85(21):11490–11501. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05379-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yanase K, et al. A subgroup of murine monoclonal anti-deoxyribonucleic acid antibodies traverse the cytoplasm and enter the nucleus in a time-and temperature-dependent manner. Lab Investig J Tech Methods Pathol. 1994;71(1):52–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mazanec MB, Coudret CL, Fletcher DR. Intracellular neutralization of influenza virus by immunoglobulin A anti-hemagglutinin monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1995;69(2):1339–1343. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.1339-1343.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mazanec MB, et al. Intracellular neutralization of virus by immunoglobulin A antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(15):6901–6905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lund FE, Randall TD. Effector and regulatory B cells: modulators of CD4(+) T cell immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(4):236–247. doi: 10.1038/nri2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elkins KL, Bosio CM, Rhinehart-Jones TR. Importance of B cells, but not specific antibodies, in primary and secondary protective immunity to the intracellular bacterium Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain. Infect Immun. 1999;67(11):6002–6007. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.6002-6007.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Esser MT, et al. Memory T cells and vaccines. Vaccine. 2003;21(5–6):419–430. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Linton PJ, Harbertson Bradley LM. A critical role for B cells in the development of memory CD4 cells. J Immunol. 2000;165(10):5558–5565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lund FE, et al. B cells are required for generation of protective effector and memory CD4 cells in response to Pneumocystis lung infection. J Immunol. 2006;176(10):6147–6154. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schultze JL, et al. Human non-germinal center B cell interleukin (IL)-12 production is primarily regulated by T cell signals CD40 ligand, interferon gamma, and IL-10: role of B cells in the maintenance of T cell responses. J Exp Med. 1999;189(1):1–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen H, et al. A specific role for B cells in the generation of CD8 T cell memory by recombinant Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 2003;170(3):1443–1451. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stephens R, Langhorne J. Priming of CD4+ T cells and development of CD4+ T cell memory; lessons for malaria. Parasite Immunol. 2006;28(1–2):25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whitmire JK, et al. Requirement of B cells for generating CD4+ T cell memory. J Immunol. 2009;182(4):1868–1876. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wojciechowski W, et al. Cytokine-producing effector B cells regulate type 2 immunity to H. polygyrus. Immunity. 2009;30(3):421–433. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Igietseme JU, et al. Antibody regulation of T cell immunity: implications for vaccine strategies against intracellular pathogens. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2004;3(1):23–34. doi: 10.1586/14760584.3.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rawool DB, et al. Utilization of Fc receptors as a mucosal vaccine strategy against an intracellular bacterium, Francisella tularensis. J Immunol. 2008;180(8):5548–5557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weber SE, Tian H, Pirofski LA. CD8+ cells enhance resistance to pulmonary serotype 3 Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in mice. J Immunol. 2011;186(1):432–442. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Schaik SM, Abbas AK. Role of T cells in a murine model of Escherichia coli sepsis. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(11):3101–3110. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vinuesa CG, et al. Follicular B helper T cells in antibody responses and autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(11):853–865. doi: 10.1038/nri1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gray D, Gray M, Barr T. Innate responses of B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(12):3304–3310. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Czuczman MS, Gregory SA. The future of CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in B-cell malignancies. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51(6):983–994. doi: 10.3109/10428191003717746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Townsend MJ, Monroe JG, Chan AC. B-cell targeted therapies in human autoimmune diseases: an updated perspective. Immunol Rev. 2010;237(1):264–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Castiglioni P, Gerloni M, Zanetti M. Genetically programmed B lymphocytes are highly efficient in inducing anti-virus protective immunity mediated by central memory CD8 T cells. Vaccine. 2004;23(5):699–708. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heit A, et al. CpG-DNA aided cross-priming by cross-presenting B cells. J Immunol. 2004;172(3):1501–1507. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jiang W, et al. Presentation of soluble antigens to CD8+ T cells by CpG oligodeoxynucleotide-primed human naive B cells. J Immunol. 2011;186(4):2080–2086. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Asano MS, Ahmed R. CD8 T cell memory in B cell-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1996;183(5):2165–2174. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Di Rosa F, Matzinger P. Long-lasting CD8 T cell memory in the absence of CD4 T cells or B cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183(5):2153–2163. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Britton S, Mitchison NA, Rajewsky K. The carrier effect in the secondary response to hapten-protein conjugates. IV. Uptake of antigen in vitro and failure to obtain cooperative induction in vitro. Eur J Immunol. 1971;1(2):65–68. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830010203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mitchison NA. T-cell-B-cell cooperation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(4):308–312. doi: 10.1038/nri1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lanzavecchia A. Antigen-specific interaction between T and B cells. Nature. 1985;314(6011):537–539. doi: 10.1038/314537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lanzavecchia A. Receptor-mediated antigen uptake and its effect on antigen presentation to class II-restricted T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:773–793. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.004013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vascotto F, et al. Antigen presentation by B lymphocytes: how receptor signaling directs membrane trafficking. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19(1):93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Itano AA, Jenkins MK. Antigen presentation to naive CD4 T cells in the lymph node. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(8):733–739. doi: 10.1038/ni957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cassell DJ, Schwartz RH. A quantitative analysis of antigen-presenting cell function: activated B cells stimulate naive CD4 T cells but are inferior to dendritic cells in providing costimulation. J Exp Med. 1994;180(5):1829–1840. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature. 2007;449(7161):419–426. doi: 10.1038/nature06175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Weber MS, et al. B-cell activation influences T-cell polarization and outcome of anti-CD20 B-cell depletion in central nervous system autoimmunity. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(3):369–383. doi: 10.1002/ana.22081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu Y, et al. Gene-targeted B-deficient mice reveal a critical role for B cells in the CD4 T cell response. Int Immunol. 1995;7(8):1353–1362. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.8.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kurt-Jones EA, et al. The role of antigen-presenting B cells in T cell priming in vivo. Studies of B cell-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1988;140(11):3773–3778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rodriguez-Pinto D, Moreno J. B cells can prime naive CD4+ T cells in vivo in the absence of other professional antigen-presenting cells in a CD154-CD40-dependent manner. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35(4):1097–1105. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rodriguez-Pinto D. B cells as antigen presenting cells. Cell Immunol. 2005;238(2):67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Catron DM, et al. Visualizing the first 50 hr of the primary immune response to a soluble antigen. Immunity. 2004;21(3):341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pape KA, et al. The humoral immune response is initiated in lymph nodes by B cells that acquire soluble antigen directly in the follicles. Immunity. 2007;26(4):491–502. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Helgeby A, et al. The combined CTA1-DD/ISCOM adjuvant vector promotes priming of mucosal and systemic immunity to incorporated antigens by specific targeting of B cells. J Immunol. 2006;176(6):3697–3706. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hon H, et al. B lymphocytes participate in cross-presentation of antigen following gene gun vaccination. J Immunol. 2005;174(9):5233–5242. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Andersen CS, et al. The combined CTA1-DD/ISCOMs vector is an effective intranasal adjuvant for boosting prior Mycobacterium bovis BCG immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2007;75(1):408–416. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01290-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McClellan KB, et al. Antibody-independent control of gamma-herpesvirus latency via B cell induction of anti-viral T cell responses. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2(6):e58. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schultze JL, Grabbe S, von Bergwelt-Baildon MS. DCs and CD40-activated B cells: current and future avenues to cellular cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(12):659–664. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chan OT, et al. A novel mouse with B cells but lacking serum antibody reveals an antibody-independent role for B cells in murine lupus. J Exp Med. 1999;189(10):1639–1648. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.10.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen X, Jensen PE. Cutting edge: primary B lymphocytes preferentially expand allogeneic FoxP3 + CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179(4):2046–2050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tsitoura DC, et al. Critical role of B cells in the development of T cell tolerance to aeroallergens. Int Immunol. 2002;14(6):659–667. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hackett CJ, et al. Immunology research: challenges and opportunities in a time of budgetary constraint. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(2):114–117. doi: 10.1038/ni0207-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pepper M, Jenkins MK. Origins of CD4(+) effector and central memory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(6):467–471. doi: 10.1038/ni.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu Y. Janeway CA Jr (1992) Cells that present both specific ligand and costimulatory activity are the most efficient inducers of clonal expansion of normal CD4 T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(9):3845–3849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Janeway CA., Jr A trip through my life with an immunological theme. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.080801.102422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. The B7-CD28 superfamily. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(2):116–126. doi: 10.1038/nri727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Medzhitov R, Janeway CA., Jr Innate immunity. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(5):338–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008033430506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dhodapkar KM, et al. Selective blockade of inhibitory Fcgamma receptor enables human dendritic cell maturation with IL-12p70 production and immunity to antibody-coated tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(8):2910–2915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500014102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kalergis AM, Ravetch JV. Inducing tumor immunity through the selective engagement of activating Fcgamma receptors on dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195(12):1653–1659. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mauri C, et al. Prevention of arthritis by interleukin 10-producing B cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197(4):489–501. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mizoguchi A, et al. Dependence of intestinal granuloma formation on unique myeloid DC-like cells. J Clin Investig. 2007;117(3):605–615. doi: 10.1172/JCI30150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rafiq K, Bergtold A, Clynes R. Immune complex-mediated antigen presentation induces tumor immunity. J Clin Investig. 2002;110(1):71–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI15640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sugimoto K, et al. Inducible IL-12-producing B cells regulate Th2-mediated intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(1):124–136. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bayry J, et al. Natural antibodies sustain differentiation and maturation of human dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(39):14210–14215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402183101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bayry J, et al. Modulation of dendritic cell maturation and function by B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2005;175(1):15–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Harris DP, et al. Reciprocal regulation of polarized cytokine production by effector B and T cells. Nat Immunol. 2000;1(6):475–482. doi: 10.1038/82717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]