Abstract

Summary: We present bammds, a practical tool that allows visualization of samples sequenced by second-generation sequencing when compared with a reference panel of individuals (usually genotypes) using a multidimensional scaling algorithm. Our tool is aimed at determining the ancestry of unknown samples—typical of ancient DNA data—particularly when only low amounts of data are available for those samples.

Availability and implementation: The software package is available under GNU General Public License v3 and is freely available together with test datasets https://savannah.nongnu.org/projects/bammds/. It is using R (http://www.r-project.org/), parallel (http://www.gnu.org/software/parallel/), samtools (https://github.com/samtools/samtools).

Contact: bammds-users@nongnu.org

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Population structure plays an important role in determining the evolutionary history of a group. A great deal has been learned from single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array technology providing unmatched information of the population structure of several species [for humans, see (Novembre and Ramachandran, 2011)]. The advent of new sequencing platforms, which can deliver millions to billions of sequencing reads within days, has shifted the focus from SNP array data to whole-genome shotgun (WGS) data. While the cost has steadily decreased (Sboner et al., 2011), obtaining many high-depth genomes remains prohibitive for many laboratories, in particular when working with ancient DNA (aDNA) samples where it is often desirable to screen many samples of potential interest while keeping the cost at a minimum.

Methods based on non-parametric multidimensional statistics (more specifically principal components analysis, PCA) were first applied to genetic data more than 30 years ago (Menozzi et al., 1978). PCA has since become a standard tool in population genetics (Patterson et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2014) owing in particular to (i) the low computational demand of such analyses, (ii) the appealing graphical result and (iii) its ease of use.

Here, we describe a tool that allows to assign an ancestry to low-depth mapped WGS data when compared with an existing reference panel of genotype data using multidimensional scaling (MDS) based on genetic distances, a related method that provides results similar to those of PCA (Cox and Cox, 2000).

2 METHODS

In what follows, we assume that WGS data have been mapped to a reference genome and that files in BAM format are available (Li et al., 2009). Calling genotypes for low-depth data is a challenging task (Nielsen et al., 2011), particularly for aDNA, as ancient damage (Briggs et al., 2007) and contamination are not incorporated into sequence data error models.

To avoid calling genotypes, we sample a read at every position for the WGS data, similar in spirit to previous aDNA approaches (Green et al., 2010). Specifically, for the reference set of individuals, we randomly sample one of the alleles from each individual, and for the WGS data, we choose an allele from a randomly selected read covering that site. If no read covers that site or if the sampled allele is not the minor or the major allele in the reference panel, we then assume that the data for this site are missing for that sample. In other words, the data in both the reference panel and the WGS samples become either one allele (A, C, G or T) or missing data.

For site k, let = 1 if individuals i and j have a different randomly chosen allele and 0 if that allele is the same or if one of the individuals has missing data. Assume that the number of sites in the reference panel is K. Denote as the number of sites where neither of individual i and j have missing data. Then, the allele-sharing distance between individuals i and j is as follows:

A matrix of allele-sharing distances between all pairs of individuals is computed. We then apply classical MDS to this matrix [e.g. (Cox and Cox, 2000)].

Our implementation has three major features:

it is user friendly and is intended to be used by biologists with limited familiarity with a UNIX system,

it is flexible in terms of formats of the reference panel and in terms of the visual output,

it runs in ∼20 min on a machine with four 2.2 GHz cores with a reference panel including >600 000 SNPs and ∼950 individuals, making it practical to screen samples of an ongoing experiment progressively as additional data are produced.

We first tested bammds through simulations using publicly available modern and ancient human data. For the WGS data, we used 10 modern human genomes from HGDP cell lines, published in Meyer et al. (2012), an Australian aboriginal genome (Rasmussen et al., 2011) and the Anzick-1 genome (Rasmussen et al., 2014). We mapped and processed the data identically for all genomes (see Supplementary data). We used a public reference panel that we make available in the Supplementary data, i.e. HGDP (Li et al., 2008), which includes > 600 000 SNPs and ∼950 individuals subdivided into 53 populations and 7 geographic regions (Africa, Eastern-, Western-, Central- and South Asia, Europe, Oceania and Native America). For each genome, we sampled , , , , and reads (which corresponds to a depth of coverage around 0.001×, 0.01×, 0.1×, 0.5×, 1× and 5×, assuming ∼100 bp sequence reads). For each sub-sampled genome, we ran bammds with the HGDP reference panel.

We summarized the simulation results using dimension 1 and 2 only of the MDS output, as we expect this to be the common usage. For each population in HGDP, we defined its centroid (or center of gravity) based on the coordinates of its members for those two dimensions. We then evaluated the results using two criteria: (i) by assessing which population was the closest when comparing the position of the WGS sample with the population centroid, and (ii) by determining if the position of the genome is within a two-dimensional 99% confidence region. We built the confidence region by assuming that the points follow a bivariate normal distribution centred around the centroid of the population to which it belongs (‘population ellipse’).

We present a practical example on how to use the tool to determine whether a library is heavily contaminated by processing a newly sequenced ∼10 000 year BP old phalange (‘Gus’) from Argentina that clusters with the Europeans (Supplementary data).

3 RESULTS

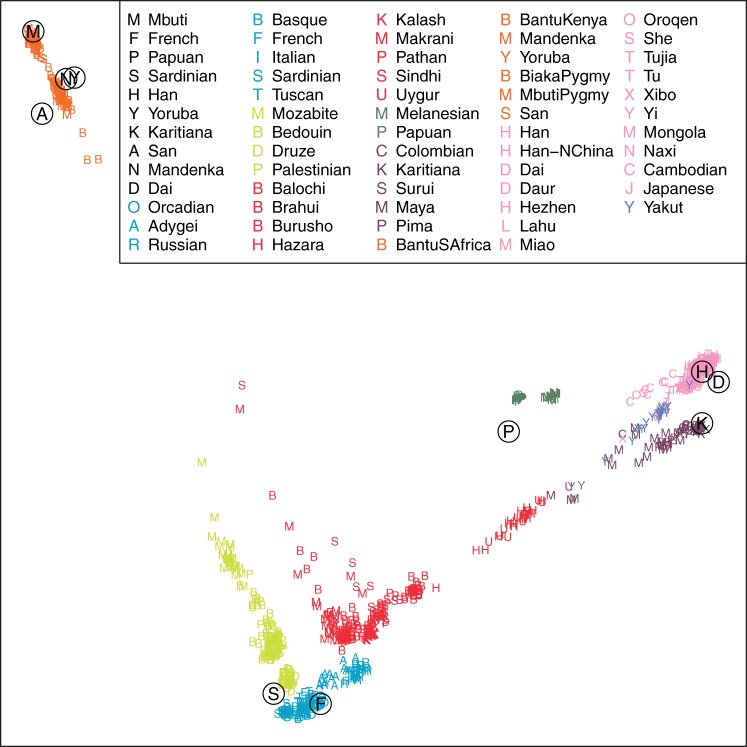

The graphical result with all 10 modern individuals at a depth of 0.1× can be seen on Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

First two dimensions of an MDS plot including the ten 0.1X modern human genomes and the HGDP SNP data

We find in the simulations that for all but two cases, we recover the geographic region as the first hit for as few as 30 000 reads (∼0.001×, Table 1). In the remaining two cases, the Sardinian and the Karitiana individual, a depth of 0.1× and 0.01×, respectively, is enough. The true nearest population was also identified in most cases within the three closest centroids for a depth above 0.01 (7/10 cases). For the second criteria, we find that in 9/10 of the cases, the WGS sample was within the population ellipse at 0.5× and above. Only in one case (San individual) was a depth of 1× necessary to be placed within the population ellipse.

Table 1.

Summary of the simulation results for the ten modern genomes. For more details, see Supplementary data

| Min. approx. depth of coverage to … | … recover geographic region as closest centroid | … recover true population within three closest centroids | … be placed within population ellipse |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mbuti (Africa) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.1 |

| French (Europe) | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.1 |

| Papuan (Oceania) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.5 |

| Sardinian (Europe) | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.5 |

| Han (Eastern Asia) | 0.001 | 0.1 | 0.01 |

| Yoruba (Africa) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.1 |

| Karitiana (America) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.1 |

| San (Africa) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1 |

| Mandenka (Africa) | 0.001 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Dai (Eastern Asia) | 0.001 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

For the ancient data, we get similar results for the Aborigine, which is assigned to the correct geographic region (Oceania) as a first hit with a depth of ∼0.001× and above. At a depth higher than 0.01×, we also recover the expected population as the closest population. For the Anzick-1 individual, presumably because of increased damage, a depth of 1× is needed to recover the geographic region as the first hit. On the other hand, a Native American population is among the three closest populations from a depth of 0.1× and above. The results for Gus are given in Supplementary data.

4 CONCLUSION

The tool we present in this article is based on classical MDS, a technique that originated in the 1930s and is commonly used in other fields [see, e.g. (Borg and Groenen, 1997) and citations therein]. We present a tool that was designed to be practical to assess the ancestry of mapped WGS data for samples sequenced at low depth, assuming that a relevant reference panel in terms of ancestry is provided. We show through simulations that useful ancestry information can be recovered for as few as 30 000 reads—corresponding to a fraction (∼1/60 in early 2014) of a HiSeq 2000 lane (www.illumina.com) for a sample with 1% endogenous content (or ∼1/4800 of a lane for a typical modern sample).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank María C. Ávila-Arcos, Amhed Missael Vargas Velázquez, Morten E. Allentoft, Hannes Schroeder, Kerttu Majander, Maanasa Raghavan and Johannes Krause for helpful discussions and testing, and the National high-throughput DNA Sequencing Center for assistance with the sequencing.

Funding: A.-S.M. was supported by a Swiss NSF, J.V.M.-M. by the ‘Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología’ (Mexico) and M.D. by the US NSF (DBI-1103639). GeoGenetics members were supported by the Lundbeck Foundation and the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF94).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Borg I, Groenen PJF. Modern Multidimensional Scaling: Theory and Applications. New York: Springer; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AW, et al. Patterns of damage in genomic DNA sequences from a Neandertal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14616–14621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704665104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox TF, Cox MAA. Multidimensional Scaling. 2nd edn. Florida: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Green RE, et al. A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science. 2010;328:710–722. doi: 10.1126/science.1188021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JZ, et al. Worldwide human relationships inferred from genome-wide patterns of variation. Science. 2008;319:1100–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1153717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menozzi P, et al. Synthetic maps of human gene frequencies in Europeans. Science. 1978;201:786–792. doi: 10.1126/science.356262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer M, et al. A high-coverage genome sequence from an archaic Denisovan Individual. Science. 2012;338:222–226. doi: 10.1126/science.1224344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R, et al. Genotype and SNP calling from next-generation sequencing data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:443–451. doi: 10.1038/nrg2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novembre J, Ramachandran S. Perspectives on human population structure at the cusp of the sequencing era. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2011;12:245–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-090810-183123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson N, et al. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen M, et al. An Aboriginal Australian genome reveals separate human dispersals into Asia. Science. 2011;334:94–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1211177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen M, et al. The genome of a Late Pleistocene human from a Clovis burial site in western Montana. Nature. 2014;506:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature13025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sboner A, et al. The real cost of sequencing: higher than you think! Genome Biol. 2011;12:125. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-8-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, et al. Ancestry estimation and control of population stratification for sequence-based association studies. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:409–415. doi: 10.1038/ng.2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.