Abstract

This study examined BMI distributions among older adults in three different countries: the U.S., Japan, and Korea. The paper also explored differences in the factors predicting BMI in the three countries using three data sets: the U.S. Longitudinal Study of Aging (LSOA II, 8,589 persons), the Nihon University Japanese Longitudinal Study of Aging (NUJLSOA, 2,888 persons), and the Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing (KLoSA, 2,397 persons). Descriptive analysis and multiple regression were performed. Japanese older adults were somewhat lighter than Koreans with fewer people at the upper end of the BMI distribution. Distributions of BMI among both Koreans and Japanese are shifted leftward relative to Americans. There is less dispersion in the distribution of BMI for Koreans and Japanese than among Americans. The association between socioeconomic variables and BMI is stronger in the U.S. and Japan than in Korea. Demographic variables are strong predictors of BMI in Korea. In Japan, all health behaviors have significant effects on BMI. It is concluded that the relationships between behavioral, demographical, and socioeconomic factors and BMI are not the same across countries. Results have policy implications for the involvement of health practitioners in helping older adults to control weight.

Keywords: Body Mass Index (BMI), older adults, the U. S., Japan, Korea, LSOA II, NUJLSOA, KLoSA

I. Introduction

Increase in obesity is a worldwide issue. Research has shown a linkage between higher weight and poorer health including a higher prevalence of diseases and more functional limitations. Increasing weight is likely to adversely affect health status in the near future in all countries (Himes, 2000; Must et al., 1999; Tsugane, Sasaki, & Tsubono, 2002; Song & Sung, 2001).

Even though the prevalence of obesity is lower in Asian than Western countries, Asian countries have experienced an increased prevalence of overweight and obesity over the past decade as have other countries including the U.S. (Flegal, Carroll, Ogden, & Johnson, 2002; Yoshiike, Kaneda, & Takimoto, 2002; Yoshiike, Seino, Tajima, & Arai, 2002). However, the rate of change varies across countries, including within Asian countries such as Japan and Korea, because body weight is strongly linked to cultural factors including diet and life style.

While the U.S. and Japan are among most affluent countries in the world, they differ in terms of health and life expectancy. Japan has both the highest life expectancy and active life expectancy in the world (Crimmins, Saito, & Ingegneri, 1997; World Health Organization [WHO], 2007). Meanwhile, the U.S. is not among the top 10 countries in either average life expectancy or active life expectancy (WHO, 2007). Life expectancy in Korea was 79.6 in 2007 which ranks between Japan and the U.S. (The Korean Statistical Information Office, 2009). Differences in life expectancy in Japan, Korea, and the U.S. could be related to levels of body weight.

Thus, it is important to examine how levels of weight or Body Mass Index (BMI), an indicator of a person’s body weight relative to height, vary across the U.S., Japan, and Korea in order to better understand how health outcomes might differ across these countries. It is also interesting to examine the association of BMI with behavioral, demographic and economic factors in different cultural settings to assess the universality of relationships (Reynolds, Hagedorn, Yeom, Saito, Yokoyama, & Crimmins, 2008). If factors associated with levels of BMI are the same in countries with very different weight distributions, this would indicate a link that is more universal and not specific to the observed cohorts in specific countries. Asian countries, which tend to have markedly different weight distributions from western countries, therefore provide especially salient comparisons.

The first purpose of this study is thus to examine BMI distributions among older adults in three different countries: the U.S., Japan, and Korea. Then, the second aim is to explore differences in the factors which predict BMI in these three countries.

By developing a conceptual framework that integrates demographic, social, and behavioral factors with body weight, this study will provide a foundation for further theoretical development in the study of determinants of BMI. In addition, determining factors associated with body weight and differences in this factors in the U.S., Japan and Korea can provide clues to effective weight-control policies for older adults in the U.S., Japan, and Korea.

II. Literature Review

1. Body Mass Index (BMI) by Country and Gender

The prevalence of overweight and obesity differs across countries and by gender. Before proceeding to our analysis of the older population, we provide some descriptive information. Table 1 shows the prevalence of overweight (25.0 ≤BMI ≤29.9) and obesity (BMI ≥30.0) among the adult population in the U.S. less than 75 years of age by gender. Two-thirds of adults (aged 20-74) in the U.S. were overweight or obese in 2003-2004 (Ogden, Carroll, Curtin, McDowell, Tabak, Flegal, 2006). While the prevalence of overweight but not obese in the U.S. has increased little from the 1960s to 1990s (Flegal, Carroll, Kuczmarski, & Johnson, 1998), the prevalence of obesity increased dramatically from the 1960s through 2003-2004 (Flegal et al., 1998). The prevalence of obesity among U.S. men increased from 12% in 1976-1980, to 20% in 1988-1994, to 28% in 1999-2000, and 31% in 2003-2004. During the same period, obesity increased from 17% to 33% among women in the U.S. (Flegal et al., 1998; Ogden et al., 2006).

Table 1.

The Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in the U.S. by Gender (Age-adjusted 20-74y)

| Overweight (%) (25.0 ≤BMI ≤29.9) |

Obesity (%) (BMI ≥30.0) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Year | All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women |

| 1960-1962 | 30.5 | 37.8 | 23.6 | 12.8 | 10.4 | 15.0 |

| 1971-1974 | 32.0 | 41.1 | 23.6 | 14.1 | 11.8 | 16.2 |

| 1976-1980 | 31.5 | 39.1 | 24.3 | 14.5 | 12.3 | 16.5 |

| 1988-1994 | 32.0 | 39.4 | 24.7 | 22.5 | 20.0 | 24.9 |

| 1999-2000a | 34.0 | 39.7 | 28.5 | 30.5 | 27.5 | 33.4 |

| 2003-2004a | 34.1 | 39.7 | 28.6 | 32.2 | 31.1 | 33.2 |

Note: Combined table from different sources (Flegal et al., 1998;

Ogden et al., 2006). (Yeom, 2009, p. 9).

Although the prevalence of obesity in Asian countries is much lower than in western countries, Asian countries have also experienced increasing weight. In Japan the prevalence of obesity was 2.9% and 3.4% for men and women respectively in 2001, an increase of 1% from 1991-1995 (Table 2). While obesity is low, there has been a remarkable increase in overweight in recent decades so that more than one-fourth of Japanese men and one-fifth of Japanese women were overweight in 2001 (Yoshiike, Kaneda, et al., 2002; Yoshiike, Seino, et al.,2002). This is related to changes in diet and life style in Japan since the 1970s (Sakamoto, 2006). In both Japan and the U.S., while the prevalence of overweight is higher for men than for women, the prevalence of obesity for women is slightly higher than that of men (Reynolds et al., 2008).

Table 2.

The Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in Japan by Gender (Age-adjusted 20-74y)

| Overweight (%) (25.0 ≤BMI ≤29.9) |

Obesity (%) (BMI ≥30.0) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Year | All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women |

| 1976-1980 | 15.2 | 14.5 | 15.7 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 2.3 |

| 1981-1985 | 15.9 | 16.5 | 15.5 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 2.3 |

| 1986-1990 | 16.1 | 18.0 | 14.6 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 2.2 |

| 1991-1995 | 17.3 | 20.5 | 14.7 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.3 |

| 2001a | 21.2 | 25.1 | 18.2 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 3.4 |

Note: Combined table from different sources

(Sakamoto, 2006; Yoshiike, Seino, et al., 2002). (Yeom, 2009, p. 9)

Korea has a higher prevalence of overweight than Japan but lower than the U.S. (see Table 3). Almost one-third of Korean adults had weight above the normal range in 2001 (Kim, Ahn, & Nam, 2005). The obesity level in Korea is similar to that of Japan. As in the U.S. and Japan, the prevalence of obesity for women is slightly higher than that for men in Korea while the prevalence of overweight for women is lower than that for men in 2001.

Table 3.

The Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in Korea by Gender (Age-adjusted 20 years and older)

| Overweight (%) (25.0 ≤BMI ≤29.9) |

Obesity (%) (BMI ≥30.0) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Year | All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women |

| 1998 | 24.2 | 23.4 | 24.9 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 3.2 |

| 2001 | 27.6 | 29.7 | 25.9 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 3.5 |

Note: Combined table from different sources (Kim, Ahn, & Nam, 2005; Ministry of Health and Welfare & Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, 2002)

The increase in the prevalence of overweight since the mid 1990’s is thought to be due to a dietary shift from carbohydrates to animal fat in Korea (Kim et al., 2005).

Table 4 shows the prevalence of overweight and obesity in the U.S. by age in 2003-2004. Almost two-thirds of adults aged 20 to 39 years, and three-fourths of persons aged 40 and older in the U.S. were above the normal range of weight (Ogden et al., 2006). As Americans get older, they have a higher prevalence of overweight, but the highest prevalence of obesity in both men and women occurs among middle-aged Americans, perhaps reflecting mortality among those with the highest weight.

Table 4.

The Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in the U.S. by Gender and Age Group in 2003-2004

| Overweight (%) (25.0 ≤BMI ≤29.9) |

Obesity (%) (BMI ≥30.0) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Age | All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women |

| 20-39 | 28.6 | 34.2 | 22.8 | 28.5 | 28.0 | 28.9 |

| 40-59 | 36.3 | 43.4 | 29.3 | 36.8 | 34.8 | 38.8 |

| ≥60 y | 40.0 | 43.3 | 37.4 | 31.0 | 30.4 | 31.5 |

Note: This table was made by recalculating prevalence from different tables of Ogden et al. (2006). (Yeom, 2009, p. 11)

The prevalence of obesity in Japan is about one tenth that in the U.S. at each age (see Table 5). In Japan, the highest prevalence of obesity is in the oldest of the three age groups. The percent of overweight is highest at the oldest age among Japanese women, but this is not true for men who are more likely to be overweight in 40-59 age group.

Table 5.

The Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in Japan by Gender and Age Group in 2001

| Overweight (%) (25.0 ≤BMI ≤29.9) |

Obesity (%) (BMI ≥30.0) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Age | All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women |

| 20-39 | 14.2 | 20.8 | 9.1 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 2.2 |

| 40-59 | 22.8 | 28.9 | 17.9 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 3.5 |

| ≥60 y | 24.4 | 22.9 | 25.6 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 4.1 |

Note: This table was made by recalculating prevalence from a table of Sakamoto (2006). (Yeom, 2009, p. 11)

The prevalence of overweight in each age group in Korea is higher than that in Japan, but lower than in the U.S. for both men and women (see Table 6). In Korea, as Japan, middle-aged men have the highest prevalence in overweight in 2001. For Korean women, the prevalence of overweight in the 40-59 age group is more than twice as high as in the 20-39 age group. The prevalence of obesity in Korea is quite low relative to the U.S. and similar to that in Japan. The age pattern for men is somewhat different in Korea with the lowest prevalence in the oldest age group. For women, the pattern of increasing obesity with age is similar to that in Japan.

Table 6.

The Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in Korea by Gender and Age Group in 2001

| Overweight (%) (25.0 ≤BMI ≤29.9) |

Obesity (%) (BMI ≥30.0) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Age | All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women |

| 20-39 | 20.6 | 28.6 | 14.6 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 1.9 |

| 40-59 | 33.0 | 33.9 | 32.3 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 3.9 |

| ≥60 y | 30.3 | 24.4 | 34.4 | 4.1 | 2.0 | 5.6 |

Note: This table was made by recalculating prevalence of Table 17 and 18 in 2001 National Health and Nutrition Survey: Health Examination (Ministry of Health and Welfare & Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, 2002).

2. Determinants of Body Mass Index

1) Body Mass Index and Demographic and Socioeconomic Factors

Weight is associated with a number of demographic and socioeconomic factors. Research has shown that BMI increases with age (Ogden et al., 2006; Sakamoto, 2006). The prevalence of overweight and obesity is higher among rural residents in Japan (Yoshiike, Kaneda, et al., 2002; Yoshiike, Seino, et al., 2002) and Korea (Health Policy Group & Chronic Disease Research Group, 2006).

Married adults have higher rates of overweight and obesity and never married or the divorced the lowest rates in the U.S. (Jeffery & Rick, 2002; Schoenborn, 2004). Among American women, the widowed were more likely to be obese than married women in middle-age. However, significant differences in body weight by marital status were not present among older adults (Sobal & Rauschenbach, 2003). In Korea, married men and women were more likely to be overweight or obese than their counterparts (Ministry of Health and Welfare & Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, 2002).

Numerous studies in the U.S. have reported BMI to be inversely associated with socioeconomic status (SES) (Jeffery, French, Forster, & Spry, 1991; Smith, 1999; Zhang & Wang, 2004a) although the relationship between BMI and education has weakened over time (Zhang & Wang, 2004b). Interactions among demographic factors have also been reported in the U.S. Among women, there is a stronger inverse association between SES and obesity than among men. There is also evidence of smaller socioeconomic inequality among older adults compared to other age groups including middle-age adults (Zhang & Wang, 2004a).

It has been thought that socioeconomic differentials in health outcomes were almost nonexistent in Japan due to the relatively equal income distribution (Marmot & Smith, 1989; Wilkinson, 1994). Gini coefficients reflecting income inequality in the U.S. and Japan reveal the lower level of income inequality in Japan than the U.S. and Korea (Xiaobin, Li, & Kelvin, 2004). Research has shown socioeconomic differentials in health outcomes including mortality in Korea (Khang & Kim, 2005; Khang & Kim, 2006). BMI has also been shown to be related to SES, particularly education and occupation in Korea (Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Chronic Disease Research Group, 2008). However, there has been only limited research examining cross-cultural relationships between socioeconomic status and BMI (Reynolds et al., 2008).

2) Body Mass Index and Behavioral Factors

The inverse associations between SES and BMI in the U.S. may be caused by socioeconomic differences in health behaviors such as drinking, diet and exercise. As Jeffery et al. (1991) have found, higher SES is also associated with health behaviors that contribute importantly to energy balance. Jeffery et al. have shown that those who have higher SES are more likely to report a lower fat diet, more exercise, and a higher prevalence of dieting to control weight.

Some research has linked smoking cessation to increased body mass index (John, Meyer, Rumpf, Hapke, & Schumann, 2006; Kadowaki, Watanabe, Okayama, Hishida, Okamura, Miyamatsu, Hayakawa, Kita, & Ueshima, 2006). In the U.S. lower SES men and women are more likely to smoke. Smoking is linked to lower rates of overweight and obesity in Japan (Mizoue, Kasai, Kubo, & Tokunaga, 2006).

Drinking is linked to higher BMI among middle-aged women in Korea (Song, Ha, & Sung, 2007). The lightest drinkers who consumed alcohol most frequently were likely to have lower BMI, but those who consumed high quantities but were infrequent drinkers were likely to have higher BMI (Breslow, & Smothers, 2005). Higher levels of BMI were associated with stress-related drinking which was predicted by being single or divorced, a long history of unemployment, and a lower level of education (Laitinen, Ek, & Sovio, 2002).

It has also been found that lower physical activity and sedentary lifestyle are strongly associated with higher BMI in many countries (Kruger, Venter, Vorster & Margetts, 2002; Martinez-Gonzalez, Martinez, Hu, Gibney, & Kearney, 1999; Monda & Popkin, 2005; Sharma, 2007; Song et al., 2007). Life style may have become more sedentary in rich countries because of increasing television viewing, white-collar jobs, computers, videos, labor-saving devices, decreased use of public transportation and increased automobile use (Sharma, 2007). Thus, the increase in overweight and obese people may result from insufficient physical activity and/or excess calorie intake (Ravussin, Fontveille, Swinburn, & Bogardus, 1993).

Examining factors associated with BMI may provide some clues to understanding why people have different levels of BMI, how socioeconomic status is associated with BMI, and how people might control body weight in different countries.

Because of limited research comparing the relationship of BMI to other factors across countries, this study seeks to answer the following research questions.

(1) How does BMI vary in the U.S., Japan, and Korea? Is the variability in BMI among Korean older adults the same as those for Japanese and American older adults?

(2) How similar are the associations of behavioral, demographic, and socioeconomic factors with BMI among older adults in the U.S., Japan, and Korea?

III. Methods

1. Data

This study uses three data sets: The U.S. Longitudinal Study of Aging (1994 Second Supplement on Aging, LSOA II), the Nihon University Japanese Longitudinal Study of Aging (NUJLSOA), and the Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing (KLoSA). All three data are from longitudinal studies, but we use only the baseline data from each study, i.e., cross-sectional data are used in this study.

LSOA II is a nationally representative sample of the U.S. population aged 70 years and older conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) beginning in 1994. LSOA II was designed to provide information on temporal changes in health and functioning among community dwelling older Americans, including background demographic characteristics, health behaviors, attitudes, preexisting illness, and social and environmental support (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007). The sample for the LSOA II was drawn from individuals who participated in the 1994 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) core interview who completed additional questions for the Second Supplement on Aging (SOA II). These participants were followed through two follow up surveys that became known as the Longitudinal Study of Aging II.

Details of sampling and design for the LSOA have been published elsewhere, and will not be repeated here (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007). The sample consists of 9,447 older Americans who were age 70 years and over at the time of the first LSOA II interview. Due to missing cases, the final sample for this study included 8,589 persons. Because the sample is based on a complex sample design, weights are used to reflect a national sample.

The NUJLSOA is a nationally representative sample of 4,997 Japanese older adults who were aged 65 and over at the baseline 1999 survey. This survey was conducted by the Nihon University Center for Information Networking as one of their research projects. The NUJLSOA sample was selected using a multistage stratified sampling method, stratifying the 47 prefectures throughout Japan into 11 regions. Approximately 3,000 municipalities were then stratified by population size within the regions and prefectures, and a systematic sample selected 340 primary sampling units (PSUs). The NUJLSOA sample members in 298 PSUs were selected based on the National Residents Registry of Japan. In another 41 units, sample members were drawn from the Eligible Voters List, which is based on, but not as regularly updated, as the National Residents Registry. From each of the 340 PSUs, 6-11 persons aged 65-74 and 8-12 persons at age 75 and over were selected for the sample. The population aged 75 and older was oversampled, and appropriate weighting systems are used in this analysis to ensure that the total sample was nationally representative of those 70 and older. More information is available at the home page of the USC/UCLA Center of Biodemography and Population Health (USC/UCLA Center of Biodemography and Population Health, 2004).

The primary purpose of the NUJLSOA was to investigate the health status and changes in health over time of the Japanese older adults. A specific aim of the NUJLOSA survey is to provide data comparable to that collected in the United States and other countries. The format of questions in the initial questionnaire was designed with attention to the format of the LSOA II.

To compare with the U.S. sample in this study Japanese persons 70 and over at baseline were selected and the sample was 2,888 persons.

The KLoSA, conducted by the Korea Labor Institute (KLI) in 2006, also aimed to build data comparable to similar studies in other countries. The purpose of the KLoSA is to provide data about the economic and social activities of the middle-aged and older population. The topics of the KLoSA include demographics, family, health, employment, income, assets, and subjective expectations and satisfaction. The KLoSA sample reflects persons 45 years and older living in community households. Thus, it excluded institutionalized residents in the first wave. Also, Jeju island was excluded for interviewing convenience (The Korea Labor Institute, 2008).

For sampling, the population was first stratified by urban or rural and housing type, i. e. apartment or house. The sampling frame for KLoSA consists of 261,237 enumeration districts (EDs) identified by the 2005 Census conducted by the National Statistics Office of Korea. From the total EDs, 1,000 sample EDs were selected. Fifteen cities and provinces were allocated first with 15 sample EDs for each city and province out of the total 1,000 sample EDs. The remaining 775 EDs were then allocated in proportion to the population of the 15 cities and provinces. Subsequently, EDs were allocated by areas, i. e. urban and rural. The final numbers of apartment EDs and ordinary housing EDs were 409 and 591 for each. Of the 409 apartment EDs, 363 EDs were in urban areas and 46 EDs were in rural areas while, of 591 ordinary housing EDs, 440 EDs and 151 EDs were in urban and rural areas, respectively. To be comparable across the three surveys, we selected Korean adults aged 70 and over at baseline for a sample of 2,397 persons after removing cases with missing data (The Korea Labor Institute, 2008). Due to the complex sampling design, the suggested sampling weight was applied to reflect a Korean national sample in the analysis.

2. Measures

1) Body Mass Index (BMI)

Self-reports of weight and height are collected in the LSOA II, the NUJLSOA and the KLoSA. Self-reports have been shown to provide relatively reliable measurement in surveys. BMI is calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2), and used as a continuous variable in analysis (See Table 7).

Table 7.

Variables and Definition of the LSOA II, NUJLSOA, and KLoSA

| Variables | Definition |

|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | |

| BMI | BMI= weight/(height)2= (kg/m2), continuous variable |

| Independent Variables | |

| Demographic variables | |

| Age | Continuous variable (70-99) |

| Gender | 0=male; 1=female |

| Marital Status | 0=not married (widowed, divorced, separated, never married); 1=married(married, married-spouse not in household-NUJLSOA, living with a partner-KLoSA) |

| Rural/Urban area | 0=living in urban area; 1=living in rural area |

| Socioeconomic variables | |

| Education | Years of education completed: continuous variable (0-18) |

| Income | Annual income, assigned midpoint of categories, replaced missing with mean value |

| Health behaviors | |

| Smoking | 0=never smoked or former smoker; 1=current smoker |

| Drinking | 0=never drunk or light drinker (drinks per day≤2); 1=heavy drinker (3+ drinks per day) |

| Exercise | 0=active (LSOA II-regular exercise, NUJLSOA-walked 3+ per week or engaged in any sports or exercise, KLoSA-regular exercise, 1+ per week); 1=inactive |

2) Demographic and Socioeconomic Variables

Age is used as a continuous variable. Korean and Japanese older adults aged 99 and over were recoded to 99, to be comparable to LSOA II. Gender is coded so that female is equal to 1 and the reference category is male (=0).

For marital status, married (=1) included both spouse in and not in the household in the U.S. survey. In the Japanese survey, married included those separated from a spouse due to hospitalization, institutionalization, or living in another area for business reasons. To be comparable, married includes those who are currently married or living with a partner in the Korean survey. In all three surveys, widowed (or missing in Korea), divorced, separated, and never married are coded as not married, the reference category (=0). To differentiate living in a rural or urban area, living in a Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSA) including outside the central city, was recoded as the reference (=0) and not living in an MSA was coded as living in a rural area (=1) in the LSOA II. In the NUJLSOA, response to the question “what sort of community do you currently live in?” was used to code city/suburbs as the reference category (=0) and living in a farming and fishing village was coded as living in rural area (=1). In the KLoSA, living in a metropolitan area or city was recoded as the reference category (=0) and living in town was recoded as living in rural area (=1).

Indicators of socioeconomic status available in three surveys include education and annual household income. In the LSOA II, respondents are asked the number of years of formal education completed. In the NUJLSOA, education was reported using 7 categories in the first wave and by single years in the second wave, collected in 2001. This study used the Wave 2 years of education when available, and where the Wave 2 question was not answered (n=857), the midpoint of the years of education of the Wave 1 category is assigned. In the KLoSA, no schooling or illiterate was recoded as 0, no schooling but literate as 1, elementary enrollment or drop out as 3. All drop outs from middle/high school and college were recoded as the completing years of education on the level of graduation. To be comparable to the U.S. survey, 18 years or more of education completed was recoded as 18 in the NUJLSOA and the KLoSA.

Korean and Japanese incomes were converted into U.S. dollars using the exchange rate for July 15, 2006 and November 15, 1999, respectively. While incomes were reported in categories in the LSOA II and the NUJLSOA, in the KLoSA income was reported as a continuous variable which was recoded into categories to be comparable to the other surveys. The categorical midpoint is assigned as the value of income. The number and range of the income categories differs; the U.S. has 26 categories with top coding at $50,000, the Japanese has 13 categories with top coding at $140,000, and the Korean has 16 categories with top coding at $50,000. We tested the sensitivity of the results to the range of income categories by collapsing the Japanese and Korean top categories to match the top U.S. category and the results were robust, so we use the available detail on income. In addition, we include a control for missing income and a value of income at the mean in all regression models for respondents for whom income information is missing so this group is not eliminated from the analysis.

3) Indicators of Health Behaviors

This study examines three additional health behaviors potentially related to BMI. Current smokers (=1) are separated from former or never smokers (=0). Heavy drinking is consuming 3+ drinks per day in the LSOA II. In the NUJLSOA and the KLoSA, consuming 3+ drinks per day included sake, beer, wine, shochu, and whisky.

For the LSOA II and the KLoSA, physical activity was determined by reports of whether the respondent engaged in regular exercise. Direct reports were used in the LSOA II and KLoSA. In order to make the comparisons as close as possible across surveys, two questions were used to create physical activity in the NUJLSOA. Respondents were asked how often during the week they went for a walk. Another question asked whether the respondent engaged in sports or exercise recently. The respondents were coded as active (=0) if the respondent walked 3 times or more per week, or engaged in any sports or exercise; otherwise they were coded as inactive (=1).

3. Statistical Analysis

To address the first research question, descriptive analysis was used to clarify the pattern of BMI distributions in American, Japanese, and Korean adults aged 70 and over.

Multiple regression was then used to examine correlates of BMI in different countries. The model included demographic variables: age, gender, marital status, living in rural or urban area. Socioeconomic variables included education, income, and missing income. Indicators of smoking, drinking, and exercise were also added to the second model. We applied appropriate sampling weights to each data set in the analysis.

IV. Results

1. Descriptive Information of Study Participants in the Three Samples

Table 8 presents demographic and other general characteristics of the study samples. Mean age in the U.S. is highest (77.2) with the same mean age in Japan and Korea (76.4). The Korean sample has the most females (61%); and Japan the lowest (58%). The proportion married is highest in Japan (58%, 56% in Korea, and 54% in the U.S.). The proportions living in rural areas are 28%, 35%, and 38% in the U.S., Korea, and Japan, respectively.

Table 8.

Sample Characteristics in the U.S., Japan, and Korea(70+): Percents and Means(SD)

| the U.S.(LSOA II) N= 8,589 |

Japan(NUJLSOA) N=2,888 |

Korea(KLoSA) N=2,397 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Dependent Variable | |||

| BMI - mean (SD) | 25.2 (4.5) | 21.9 (3.1) | 22.4 (3.7) |

| Overweight (25.0 ≤BMI ≤29.9) | 37.3 | 15.6 | 15.7 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30.0) | 15.0 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Independent Variables | |||

| Demographic variables | |||

| age - mean (SD) | 77.2 (5.7) | 76.4 (4.8) | 76.4 (5.4) |

| female | 59.3 | 57.5 | 60.6 |

| married | 54.4 | 58.3 | 56.2 |

| living in rural area | 27.6 | 38.1 | 35.0 |

| Socioeconomic variables | |||

| education - mean (SD) | 11.2 (3.5) | 8.7 (2.5) | 4.8 (4.5) |

| income($) - mean (SD) | 26,611.1 (18933.5) | 24,441.6 (18516.7) | 10,473.4 (12793.4) |

| missing income | 23.1 | 18.6 | 12.5 |

| Health behaviors | |||

| current smoker | 9.8 | 14.9 | 13.4 |

| heavy drinker | 3.2 | 5.5 | 4.8 |

| no regular exerciser | 59.6 | 22.1 | 73.6 |

Education in the U.S. is the highest (mean 11.2 years), and lowest in Korea (mean 4.8 years). Japan falls into between the U.S. and Korea (mean 8.7 years). Income is highest in the U.S. ($26,611). The average income in Korea is less than a half of the American value. The proportion with missing income is almost 25% in the U.S. and for Japan and Korea it is 18.6% and 12.5%, respectively.

Current smokers are most common in Japan (14.9%), slightly lower in Korea (13.4%) and lowest in the U.S. (9.8%). Heavy drinking is relatively rare everywhere: Japan (5.5%), Korea (4.8%), and the U.S. (3.2%). While smoking and heavy drinking are more common in Japan, the proportion not exercising regularly is lowest among the three countries (22.1%). The proportion of those who do not exercise regularly in Korea is the highest among three countries (73.6%).

2. Weight in the Three Samples

The difference in weight of the three countries is indicated by the means of BMI in Table 8. Mean BMI among American older adults is highest (25.2) and lowest among Japanese (21.9). Korean older adults have a mean BMI (22.4) between the U.S. and Japan. However, prevalence of overweight or obesity in Korea is 17.1% which is about the same as in Japan (17.0%) while half of American older adults are overweight or obese (52.3%).

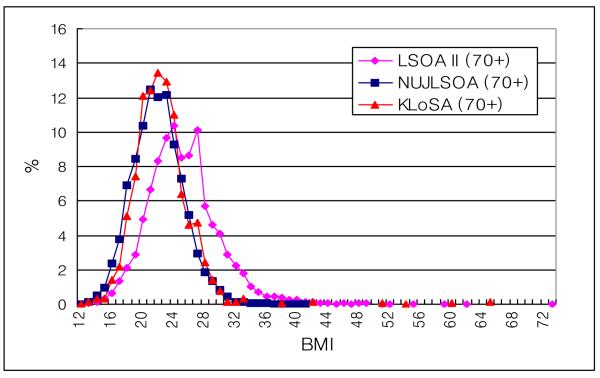

The weight distributions (BMI) of three samples capturing the full range of the groups are presented in Figure 1. The distributions of BMI for Japanese and Koreans are fairly similar.

Figure 1.

BMI Distributions in the U.S., Japan, and Korea

Japanese older adults are somewhat lighter than Koreans as indicated by the lack of a tail on their distribution. Both the Korean and Japanese distributions are shifted leftward relative to Americans. There is less dispersion in the BMI of Koreans and Japanese than among Americans.

3. Associations of Factors with Weight Based on Multiple Regressions

BMI was regressed within each sample on three sets of variables: demographic variables, socioeconomic variables, and health behaviors. Table 9 presents both standardized and unstandardized coefficients from multiple regressions on BMI for each country. The model results in a R2 of approximately .07 in the U.S., .05 in Japan, and .06 in Korea (p<.0001), a statistically significant but low value. While in the U.S. higher age (b=−.19, β=−.24), being female (b=−.44 β=−.05), and being married (b=−.31, β =−.03) are linked to significantly lower BMI; living in a rural area is not significantly associated with BMI. As years of education increases by 1 year, the level of BMI significantly decreases by .11 in the U.S. As income goes up, level of BMI significantly goes down in the U.S. (β=−.03). Among the three health behaviors, current smokers have significantly lower BMI by 2.26 compared to non current smokers. Those who do not exercise regularly have significantly higher BMI by .78 relative to regular exerciser. However, heavy drinking is not significantly linked to BMI in the U.S.

Table 9.

Unstandardized Coefficients From Multiple Regression on BMI

| variables | the U.S. (LSOA II: N=8,589) |

Japan (NUJLSOA: N=2,888) |

Korea (KLoSA: N=2,397) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| b (β) | b (β) | b (β) | |

|

| |||

| demographic variables | |||

| age | −.19(−.24)*** | −.12(−.18)*** | −.12(−.18)*** |

| female | −.44(−.05)*** | .12(.02) | .45(.06)* |

| married | −.31(−.03)** | −.10(−.01) | −.12(−.02) |

| living in rural | .10(.01) | −.15(−.02) | −.49(−.06)** |

| socioeconomic variables | |||

| education | −.11(−.08)*** | −.05(−.04)* | .05(.07)** |

| income | −.00(−.03)* | .00(.04)* | .00(.01) |

| missing income | −.04(−.00) | −.04(−.00) | .07(.01) |

| health behaviors | |||

| current smoker | −2.26(−.15)*** | −.79(−.09)*** | −.59(−.05)* |

| heavy drinker | .51(.02) | .54(.04)* | .01(.00) |

| no regular exerciser | .78(.08)*** | −.40(−.05)** | −.35(−.04) |

|

| |||

| constant | 41.31*** | 31.34*** | 31.62*** |

| R2 (Adj. R2) | .074(.075) | .048(.045) | .055(.051) |

| F (df) | F(10)=69.13*** | F(10)=16.30*** | F(10)=13.91*** |

Among demographic variables in Japan, only age (b=−.12, β=−.18) is significantly associated with BMI. While years of education is inversely associated with BMI in both the U.S. and Japan, income is differently linked to BMI in those two countries. As years of education increases, the level of BMI significantly decreases (β=−.04). Contrary to the U.S., higher income is linked to significantly higher BMI. As income increases, level of BMI significantly increases in Japan by about half as much as in the U.S. (β=.04). In Japan, all three health behavioral variables are significantly related to BMI. Current smokers have significantly .79 lower BMI compared to non current smokers. Heavy drinkers have .54 higher BMI than non heavy drinkers, but those who do not exercise regularly have .40 lower BMI than those who exercise regularly.

For Korean older adults, higher age (b=−.12, β=−.18) is linked to significantly lower BMI as is true in the other two countries. However, living in a rural area is significantly associated with BMI only for Korean older adults. Those who live in a rural area have significantly lower BMI (β=−.06). Meanwhile, being female is significantly associated with higher BMI (b=.45, β=.06), which is different from the result in the U.S. Marital status is not statistically significantly related to BMI among Korean older adults, which also differs from the U.S. Higher education, but not income, is associated with higher BMI (b=.05, β=.07), which differs from relationships between years of education and BMI in the U.S. and Japan. Among the three health behavior variables, only smoking is significantly linked to BMI in Korea. Current smokers have lower BMI than that of non current smokers among older Koreans, which is similar in direction to relationships between currently smoking and BMI in the U.S. and Japan, but the effect size is smaller in Korea. The other two health behavioral variables are not significantly associated with BMI in Korea.

V. Discussion

In this study, we examined BMI distributions and the similarity of relationships between behavioral, demographic, and socioeconomic factors with BMI among older adults in the U.S., Japan, and Korea.

Our results indicate the markedly lower levels of BMI among Japanese and Korean older adults compared to American older adults. Specifically, BMI in the U.S. is highest and Korea ranks between the U.S. and Japan. The BMI distribution in Japan has a shorter tails at the high end than that in the U.S. and Korea. This result is consistent with previous literature pointing out that the prevalence of overweight or obesity was highest in the U.S. and lowest in Japan (Flegal et al., 1998; Ogden et al., 2006; Sakamoto, 2006; Yoshiike, Seino, et al., 2002). This finding is not inconsistent with the idea that the long life expectancy in Japan could be related to levels of body weight. However, as diet and life style in Japan have changed since the 1970s and accelerated recently, we should keep looking at the trend of BMI in Japan (Sakamoto, 2006). Korea also has experienced similar change with a shift in diet from carbohydrates to animal fat and a change of lifestyle (Kim et al., 2005).

To answer the second research question, we explored the relationships between behavioral, demographic, and socioeconomic variables and levels of BMI by analyzing data from the three countries using multiple regressions. Our findings show similar directions in the relationships between age and levels of BMI across countries. Contrary to previous research (Ogden et al., 2006; Sakamoto, 2006), age is inversely associated with levels of BMI in all three countries indicating that levels of BMI decrease as age increases among older adults aged 70 and over. This may be because previous research included mainly young adults aged 20 years and older, but our research was limited to people whose age ranged from 70 to 99 years old. This may mean that young adults increase their weight as age increases and body weight peaks in middle-age, with a loss in weight at some point after that. On the other hand, our finding may result from a survival differences between overweight or obese and those of normal weight. Those with higher weight may have premature mortality among the middle-aged, particularly death from cardiovascular disease (Diehr et al., 1998; Seidell, Verschuren, van Leer, & Kromhout, 1996).

In addition, our results may reflect that older adults loose muscle mass and bone mass with increasing age (Baumgartner, Waters, Gallagher, Morley, & Garry, 1999; Hughes, Frontera, Roubenoff, Evans, & Singh, 2002). Since loss of muscle and bone mass can be linked to falls in old age, maintaining appropriate body weight is crucial for quality of later life.

Our findings indicate differences in the linkages of gender, marital status, and residential area to levels of BMI across the countries. In spite of the fact that women are conventionally more likely to have higher levels of BMI than men as in Korea, this study showed women had lower levels of BMI in the U.S. and no sex differences in Japan. Only for American older adults was being married significantly associated with lower levels of BMI although the associations between marital status and levels of BMI appeared to be in the same direction in all three countries. This result does not support the findings of previous research in the U.S. in which there was no evidence of significant differences between being married and non married in body weight among older adults (Jeffery & Rick, 2002; Schoenborn, 2004). This might be related to longer life expectancy, so that the association between being married and lower BMI in the middle-aged may appear in older adults. Regarding residential area, only Korean older adults who lived in rural area had significantly lower BMI, which is different from previous research, too (Health Policy Group & Chronic Disease Research Group, 2006). This finding may be related to the fact that Korean older adults living in rural areas are more involved in health promotion behaviors including being less likely to smoke and drink, and more likely to exercise although they have lower levels of knowledge of health behaviors than their urban counterparts (Suh, 2000).

With regard to socioeconomic variables, education is significantly linked to levels of BMI in all three countries, but the relationships differ. As expected, years of education is adversely associated with levels of BMI in the U.S. and Japan; however, it is positively related to levels of BMI in Korea. Annual household income is negatively associated with level of BMI in the U.S., but positively associated with level of BMI in Japan. Our findings for the U.S. are thus consistent with previous studies (Jeffery et al., 1991; Smith, 1999; Zhang & Wang, 2004a). In the U.S. and Japan, the fact that as years of education increase, levels of BMI go down may imply that those with higher education may recognize the importance of controlling body weight and be knowledgeable about the relationships of higher weight with negative health outcomes including illnesses, disabilities, and death (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 1998).

However, the reason why in Korea years of education is positively related to levels of BMI might be because most Korean older adults had very low levels of education. As we see a mean education of Korea (Table 8), many participants in our sample reported that they have not graduated from even elementary school. Also Korea is relatively less developed country than the U.S. and Japan, so that higher levels of education may be related to higher weight because weight may be a symbol of affluence as countries develop. Increases in income may result in increases in fat in the diet and gaining weight.

Expectedly, current smoking is negatively associated with levels of BMI in all three countries. The effect size is largest in the U.S. and smallest in Korea. Heavy drinkers, however, are more likely to have higher levels of BMI only in Japan. This may result from the fact that heavy drinkers are relatively common in Japan compared to the U.S. and Korea perhaps because Japanese more often drink with their colleagues. Interestingly, a lack of regular exercise was linked to higher levels of BMI in the U.S., but lower levels of BMI in Japan. For Japanese older adults, the linkage of no regular exerciser to lower levels of BMI may be linked to loss of muscle and bone due to no exercise (Villareal, Banks, Sinacore, Siener, & Klein, 2006). This leads to frailty, falls, and even to residence in facilities including nursing homes.

Overall, the association between socioeconomic variables and levels of BMI is stronger in the U.S. and Japan than in Korea. However, our results confirm that socioeconomic differentials in levels of BMI were smaller in Japan than in the U.S. as found in previous research (Marmot & Smith, 1989; Wilkinson, 1994). Data for Korea have shown that there appear to be some effects of demographic variables on levels of BMI with small effects of SES and health behaviors. In Japan, all three health behaviors have significant effects on levels of BMI. the effects seem strongest in the U.S.

This study suggests some research implications. First, the results of this study showed that the level of education is predictor of body weight among Japanese and American older adults. Although our findings did not find this link in Korea, it is possible that the direction of the relationship with SES changes over time and that in the future the direction of the weight and education relationship might change. This could be because the next cohorts with higher education would be able to understand how important it is to maintain proper body weight for quality of later life.

Second, results of this study have policy implications for nurses, geriatricians, and directors in facilities for older adults who need to understand different ways of weight control in different settings. Specifically, in the U.S., practitioners need to help older adults to exercise regularly in order to prevent obesity. However, in Japan, the reason to exercise regularly may be not to loose muscle and bone mass with increasing age.

Third, it is also expected that the findings are clinically relevant for health practitioners in linking weight to risk of illnesses. According to recent research (Reynolds et al., 2008), differentials in health outcomes including diabetes, heart disease, arthritis, and functioning problems between the U.S. and Japan to some extent reflect differences in body weight. Therefore, our findings bring up the importance of maintaining proper body weight to prevent older adults from having diseases.

This study has some limitations. First, it used cross-sectional data, which allow us to observe associations, however does not help allow us to determine causality between various factors and levels of BMI. All of our conclusions about national differences depend on how well variables were matched across country surveys and how accurately data are self-reported in each country. Self-reporting weight and height may lead to respondents overestimating height and underestimating weight (Rowland, 1990; Steven, Keil, Waid, & Gazed, 1990). Nevertheless, because the concordance between measured and self-reported height and weight are very high in previous studies (Gorber, Tremblay, Moher, & Gorber, 2007; Spencer, Appleby, Davey, & Key, 2007), we believe that our findings are reliable.

Second, this study compared data collected at different points of time: LSOA II was in 1994, the NUJLSOA in 1999, and the KLoSA in 2006. Thus, there are difficulties in compare some variables affected by global and domestic economic trends like household income. If we supplemented household income with other variables such as lifetime longest occupation and the year of retirement, our findings could have been more robust in clarifying the role of different economic aspects. However, we believe that our cross-country comparison has provided a unique prospective on international differences in the factors linked to weight.

A further limitation is that the explanatory power of our model is relatively low (R2). Body weight must be a consequence of various unmeasured factors, and our prediction ability is limited with only some demographic, socioeconomic, and health behavioral factors. In particular, it would be important to include dietary intake and regularity of meals in the models, but our study was not able to include them due to a lack of information. Future research adding these indicators could provide a contribution to knowledge with regards to linkage of various factors to body weight in different settings.

Footnotes

Support for this research was provided by the National Institute on Aging Grants No. R03 AG21609 and No. P30 AG17265.

References

- Baumgartner RN, Waters DL, Gallagher D, Morley JE, Garry PJ. Predictors of skeletal muscle mass in elderly men and women. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 1999;107(2):123–136. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(98)00130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow RA, Smothers BA. Drinking patterns and body mass index in never smoker: National Health Interview Survey, 1997-2001. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;161(4):368–376. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention Longitudinal Studies of Aging LSOAs: (LSOAII) [Retrieved August 15, 2007]. Jul, 2007. from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/otheract/aging/lsoa2.htm.

- Crimmins EM, Saito Y, Ingegneri DG. Trends in disability-free life expectancy in the United States, 1970-1990. Population and Development Review. 1997;23:555–572. [Google Scholar]

- Diehr P, Bild DE, Harris TB, Duxbury A, Siscovick D, Rossi M. Body mass index and mortality in nonsmoking older adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:623–629. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.4.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson CL. Overweight and obesity in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1960-1994. International Journal of Obesity. 1998;22:39–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2000. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:1723–1727. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorber SC, Tremblay M, Moher D, Gorber B. A comparison of direct vs. self-report measures for assessing height, weight and body mass index. Obesity Reviews. 2007;8:307–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Policy Group & Chronic Disease Research Group . The third Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES III). 2005: Health examination. Ministry of Health and Welfare & Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Guacheon: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Himes CL. Obesity, disease, and functional limitation in later life. Demography. 2000;37:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes VA, Frontera WR, Roubenoff R, Evans WJ, Singh MAF. Longitudinal changes in body composition in older men and women: Role of body weight change and physical activity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;76:473–481. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.2.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery RW, French SA, Forster JL, Spry VM. Socioeconomic status differences in health behaviors related to obesity: The healthy worker project. International Journal of Obesity. 1991;15:689–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery RW, Rick AM. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between body mass index and marriage-related factors. Obesity Research. 2002;10:809–815. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John U, Meyer C, Rumpf H-J, Hapke U, Schumann A. Predictors of increased body mass index following cessation of smoking. The American Journal of Additions. 2006;15:192–197. doi: 10.1080/10550490500528738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadowaki T, Watanabe M, Okayama A, Hishida K, Okamura T, Miyamatsu N, et al. Continuation of smoking cessation and following weight change after intervention in a healthy population with high smoking prevalence. Journal of Occupational Health. 2006;48:402–406. doi: 10.1539/joh.48.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khang Y-H, Kim HR. Explaining socioeconomic inequality in mortality among South Korean: An examination of multiple pathways in a nationally representative longitudinal study. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;34(3):630–637. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khang Y-H, Kim HR. Socioeconomic mortality inequality in Korea: Mortality follow-up of the 1998 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health. 2006;39(2):115–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DM, Ahn CW, Nam SY. Prevalence of obesity in Korea. Obesity Review. 2005;6:117–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Disease Research Group . National health statistics 2007: The fourth Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES IV) Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Seoul: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger HS, Venter CS, Vorster HH, Margetts BM. Physical inactivity is the major determinant of obesity in black women in the North West Province, South Africa: the THUSA study. Transition and Health During Urbanisation of South Africa. Nutrition. 2002;18:422–427. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00751-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laitinen J, Ek E, Sovio U. Stress-related eating and drinking behavior and body mass index and predictors of this behavior. Preventive Medicine. 2002;34(1):29–39. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot MG, Smith GD. Why are the Japanese living longer? British Medical Journal. 1989;299:1547–1551. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6715.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Martinez JA, Hu FB, Gibney MJ, Kearney J. Physical inactivity, sedentary life style and obesity in the European Union. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 1999;23:1192–1201. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare & Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs . 2001 national health and nutrition survey: Health examination. Ministry of Health and Welfare; Guacheon: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mizoue T, Kasai H, Kubo T, Tokunaga S. Leanness, smoking, and enhanced oxidative DNA damage. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2006;15:582–585. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monda KL, Popkin BM. Cluster analysis methods help to clarify the activity-BMI relationship of Chinese youth. Obesity Research. 2005;13:1042–1051. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1523–1529. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute . Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. U.S. Public Health Service; Washington, D.C.: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravussin E, Fontveille A, Swinburn BA, Bogardus C. Risk factors for the development of obesity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1993;683:141–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb35700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds SL, Hagedorn A, Yeom J, Saito Y, Yokoyama E, Crimmins EM. A tale of two countries-the United States and Japan: Are differences in health due to differences in overweight? Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;18(6):280–290. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE2008012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland ML. Self-reported weight and height. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1990;52:1125–1133. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.6.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto M. The situation of the epidemiology and management of obesity in Japan. International Journal of Vitamin and Nutrition Research. 2006;76:253–256. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.76.4.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn CA. Marital status and health: United States, 1999-2002. Advance Data. 2004;351:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidell JC, Verschuren WMM, van Leer EM, Kromhout D. Overweight, underweight, and mortality: A prospective study of 48,287 men and women. Archives of the Internal Medicine. 1996;156:958–963. doi: 10.1001/archinte.156.9.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M. Behavioural interventions for preventing and treating obesity in adults. Obesity Reviews. 2007;8:441–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JP. Healthy bodies and thick wallets: The dual relation between health and economic status. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1999;13:145–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobal J, Rauschenbach BS. Gender, marital status, and body weight in older U.S. adults. Gender Issues. 2003;21(3):75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Song Y-M, Ha M, Sung J. Body mass index and mortality in middle-aged Korean women. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17:556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y-M, Sung J. Body mass index and mortality: A twelve-year prospective study in Korea. Epidemiology. 2001;12:173–179. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer EA, Appleby PN, Davey GK, Key TJ. Validity of self-reported height and weight in 4808 EPIC-Oxford participants. Public Health Nutrition. 2007;5(4):561–565. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steven SJ, Keil JE, Waid R, Gazes PC. Accuracy of current, 4-year, and 28-year self-reported body weight in an elderly population. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1990;132(6):1156–1163. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh IS. Health knowledge level and health-promoting behavior of the elderly. Journal of the Korea Gerontological Society. 2000;20:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- The Korea Labor Institute Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing. [Retrieved on September 20, 2008]. 2008. from http://www.kli.re.kr.

- The Korean Statistical Information Office Statistics: population·household (life table) [Retrieved on April 4]. 2009. from http://www.kosis.kr.

- Tsugane S, Sasaki S, Tsubono Y. Under- and overweight impact on mortality among middle-aged Japanese men and women: A 10-y follow up of JPHC Study Cohort I. International Journal of Obesity. 2002;26:529–537. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USC/UCLA Center of Biodemography and Population Health Nihon University Japanese Longitudinal Study of Aging. [Retrieved August 13, 2007]. 2004. from http://www.usc.edu/dept/gero/CBPH/nujlsoa/overview.htm.

- Villareal DT, Banks M, Sinacore DR, Siener C, Klein S. Effect of weight loss and exercise on frailty in obese older adults. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:860–866. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.8.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG. The epidemiological transition: from material scarcity to social disadvantage? Daedalus. 1994;123:61–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization World Health Statistics 2007. [Retrieved on May 22, 2007]. 2007. http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat2007_10highlights.pdf.

- Xiaobin Z, Li Z, Kelvin STO. Income inequalities under economic restructuring in Hong Kong. Asian Survey. 2004;44:442–473. [Google Scholar]

- Yeom J. Doctoral dissertation. University of Southern California; 2009. The effect of body weight on mortality: Different countries and age groups. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiike N, Kaneda F, Takimoto H. Epidemiology of obesity and public health strategies for its control in Japan. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;11(suppl):S727–S731. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiike N, Seino F, Tajima S, Arai Y, Kawano M, Furuhata T, et al. Twenty-year changes in the prevalence of overweight in Japanese adults: The National Nutrition Survey 1976-1995. Obesity Reviews. 2002;3:183–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2002.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Wang Y. Socioeconomic inequality of obesity in the United States: Do gender, age, and ethnicity matter? Social Science and Medicine. 2004a;58:1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Wang Y. Trends in the association between obesity and socioeconomic status in U.S. Adults: 1971 to 2000. Obesity Research. 2004b;12:1622–1632. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]