Abstract

Postglycosylation acetylation of sialic acid imparts unique roles to sialoglycoconjugates in mammalian immune response making structural and functional understanding of these analogues important. Five partially O-acetylated Neu5Ac analogues have been synthesized. Reaction of per-O-silylated Neu5Ac ester with AcOH and Ac2O in pyridine promotes regioselective silyl ether/acetate exchange in the following order: C4 (2°) > C9 (1°) > C8 (2°) > C2 (anomeric). Subsequent hydrogenolysis affords the corresponding sialic acid analogues as useful chemical biology tools.

In nature, sialic acids are found in more than 50 forms.1 These important carbohydrates are nine carbon keto-aldonic acids typically attached to the terminal ends of glycolipids and glycoproteins in vertebrates and various pathogenic bacteria (Table 1).2 The most common form of sialic acid is Neu5Ac (Table 1),3 which plays critical roles in many biological and physiological functions such as signal transduction,3 cell–cell recognition and growth,4 and immunology.5 The structures of sialoglycoconjugates are further diversified by O-acetylation (Table 1).6 These derivatives are products of sialate O-acetyltransferases (SOATs) that selectively O-acetylate at various positions of Neu5Ac. O-Acetylation influences the biology of mammalian cells by altering the ligand properties and degradation pathways of sialoglycoconjugates.7,8 In bacteria, O-acetylation can lead to inhibition of the host immune response, thereby serving as a masking system that enables pathogenic functions.9

Table 1. Acetylated Sialic Acids: Natural Occurrence and Structural Divergence.

| compd name | abbreviation | occurrence |

|---|---|---|

| 5-N-acetylneuraminic acid | Neu5Ac | V, E, Ps, Pz, F, B |

| 5-N-acetyl-4-O-acetylneuraminic acid | Neu4,5Ac2 | V |

| 5-N-acetyl-4,9-di-O-acetylneuraminic acid | Neu4,5,9Ac3 | V |

| 5-N-acetyl-4,7,9-tri-O-acetylneuraminic acid | Neu4,5,7,9Ac4 | V |

| 5-N-acetyl-4,7,8,9-tetra-O-acetylneuraminic acid | Neu4,5,7,8,9Ac5 | V |

| 5-N-acetyl-7-O-acetylneuraminic acid | Neu5,7Ac2 | V, Pz, B |

| 5-N-acetyl-9-O-acetylneuraminic acid | Neu5,9Ac2 | V, E, Pz, F, B |

Abbreviations used: V, vertebrates; E, echinoderms; Ps, protostomes (insects and mollusks); Pz, protozoa; F, fungi; B, bacteria.

Historically, it has been suggested that O-acetylation can potentially serve as a clue to mammalian evolutionary phenomena.10 However, to date, only sialate-4-O-acetyltransferase (4-SOAT) has been identified in mammals,11 and isolation and cloning 4-SOAT have not yet been successful.

There is sufficient evidence documenting the presence of 4-O-acetyl containing Neu5Ac analogues (Table 1); however, full characterization and biological understanding of these derivatives is lacking and the limitations of current extraction methods make synthesis of these analogues important. While naturally occurring sialic acids found in mammalian cells are often conjugated to other sugars, partially acetylated monomers have been isolated from natural sources (Table 1). Moreover, synthetic standards have proven useful in monitoring degradation products of Neu5Ac lyase during sialoglycoconjugate isolation and other biochemical assays.12

With growing interest in Neu5Ac analogues and glycoside synthesis, methodologies that allow regioselective functionalization of carbohydrates in an efficient manner are of great utility to synthetic chemists. However, Neu5Ac contains several hydroxyl groups with similar reactivities that are challenging to control, and there is evidence that intramolecular hydrogen bonding creates further complexity.13 To avoid these issues, traditional chemical methods have utilized multiple protection–deprotection steps, and although enzymatic approaches do not require protecting group manipulations these methods are applicable to a limited number of substrates.14

Only a few chemical syntheses of partially O-acetylated Neu5Ac have appeared in the literature. In 1990, Hasegawa and co-workers first reported the preparation of Neu4,5(Ac)2 using isopropylidene protection of the C8 and C9 of Neu5Ac thioglucosides followed by kinetically controlled acetylation.15 More recently, Clarke and co-workers synthesized a series of monoacetylated Neu5Ac12 with an improved adaptation of the Hasegawa approach using free Neu5Ac instead of preparing Neu5Ac thioglucosides. The overall yields of both approaches were comparable.

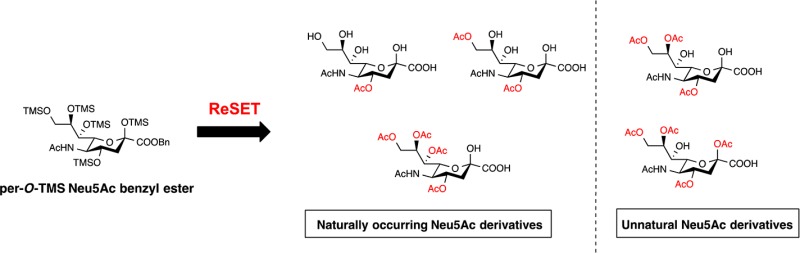

Previously in our laboratory, selective acetylation of aldose sugars was achieved using regioselective silyl-exchange technology (ReSET).16,17 Readily available per-O-silylated sugars were dissolved in pyridine and acetic anhydride, and upon addition of acetic acid the silyl protecting groups exchanged with acetate in a predictable manner, depending upon the structure of the aldose. Although Neu5Ac is a keto-aldonic sugar rather than an aldose, we were hopeful that the methodology would prove equally successful. With growing interest in step economy syntheses,18a−18c we endeavored to apply ReSET toward the synthesis of partially O-acetylated Neu5Ac natural products.

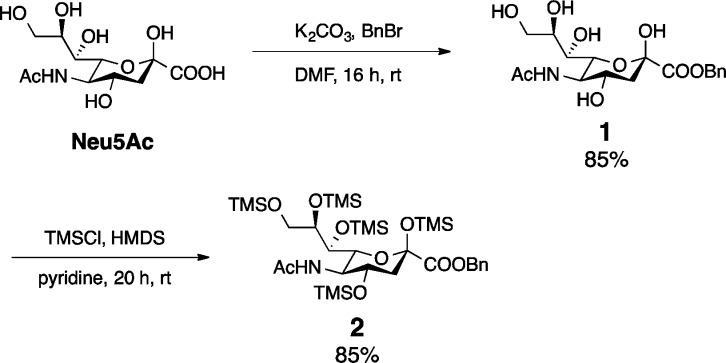

The research began with sialic acid benzyl ester formation using K2CO3 and BnBr in DMF to afford 1 in 85% yield (Scheme 1). Esterification minimized solubility issues associated with the Neu5Ac carboxylic acid. After benzyl ester formation, our focus turned to the preparation of per-O-TMS Neu5Ac benzyl ester (2). Attempts were made to prepare 2 using published protocols;19,20 however, we found that Neu5Ac benzyl ester was only partially silylated under these conditions. Gratifyingly, an ether silylation method reported by Sweeley and co-workers, using hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) and chlorotrimethylsilane (TMSCl) in pyridine, successfully afforded 2 in 85% yield (Scheme 1).21

Scheme 1. Benzylation and Silylation of Neu5Ac.

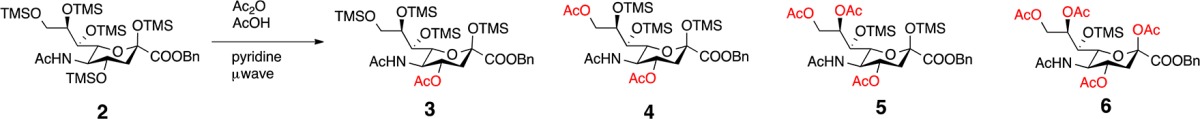

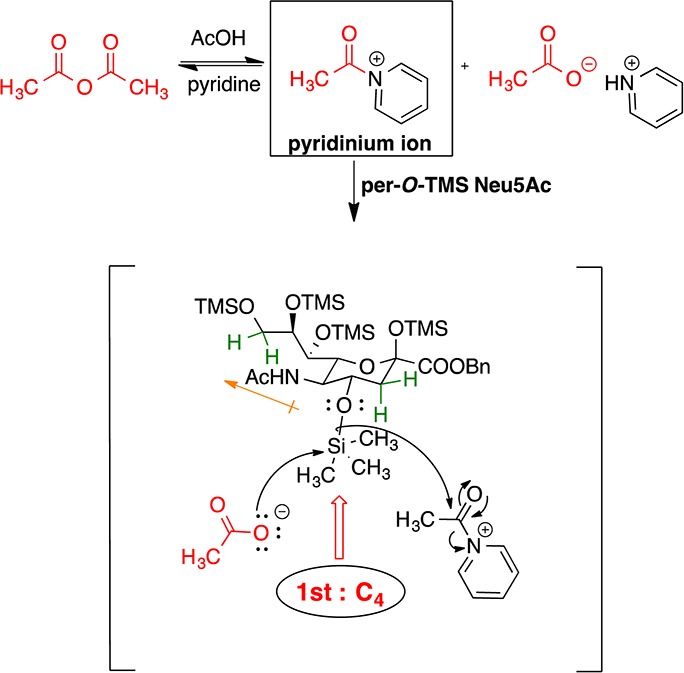

ReSET studies were initiated by diluting 2 in dry acetic anhydride and pyridine and 3 equiv of glacial acetic acid (≥99.85%) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt overnight to afford a distribution of acetylated Neu5Ac analogues (3–6) of which 6 was the major product (Table 2, entry 1). Delighted with this result, we then attempted to reduce the reaction time by subjecting the reaction mixture to microwave irradiation in a commercial CEM-microwave reactor at 60 °C and 30 W power for 30 min, which afforded 3–6 in a slightly lower overall yield (Table 2, entry 2). Reducing the amount of acetic acid to 2 equiv and heating the reaction to 70 °C with 40 W power for 30 min gave 3–6 in the most even distribution (Table 2, entry 3). To increase the scale of the reaction, the amount of 2 was nearly doubled and set up with 2 equiv of acetic acid at 58 °C and 30W power for 18 min to afford 3–6 with noticeably increased amounts of 5 and 6 (Table 2, entry 4). Likewise, we were to able to optimize for the production of 3 and 4 by reducing the amount of acetic acid to 1 equiv while running the reaction at 55 °C and 30 W power (Table 2, entry 5). Optimizing conditions for the production of compound 4 was especially important because it is a precursor to analogue 15 (see Scheme 3). To further shorten the synthesis, attempts were made to directly apply ReSET to 1; however, per-O-acetylated Neu5Ac was the only product observed after 10 min. This result illustrates the importance of the silyl protecting groups in achieving regioselective exchange.

Table 2. Various Conditions of ReSET To Afford 3-6.

| entry | scale (mg) | time (min) | T (°C) | power (W) | AcOH (equiv) | 3 (%) | 4 (%) | 5 (%) | 6 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 113 | overnight | rt | no | 3 | 4 | 11 | 20 | 43 |

| 2 | 207 | 30 | 60 | 30 | 3 | 5 | 13 | 22 | 24 |

| 3 | 234 | 30 | 70 | 40 | 2 | 11 | 20 | 17 | 28 |

| 4 | 470 | 18 | 58 | 30 | 2 | 13 | 8 | 32 | 46 |

| 5 | 196 | 45 | 55 | 30 | 1 | 28 | 31 | 16 | 11 |

Scheme 3. Alternative Synthetic Route to Neu4,5,7,8,9(Ac)5.

Each ReSET product was analyzed by heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC) and heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) NMR experiments to determine the position of the acetyl protecting groups. The HMBC NMR experiments were critical to observe the correlation between the sugar backbone C–H protons to the carbonyl carbon of the acetyl protecting groups to determine the position of the acetyl protecting group (Figure 1). A four-bond HMBC NMR experiment was performed to observe correlation between methyl protons of the acetate to the sugar carbon to characterize 6 since the anomeric carbon of Neu5Ac does not bear a proton for three-bond HMBC.

Figure 1.

Key HMBC signals for characterization.

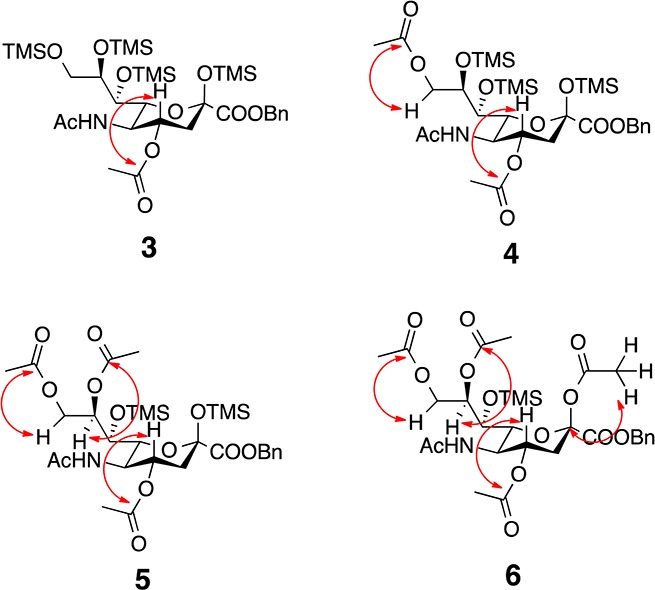

Once the products of the reactions were identified, we were able to determine the order of acetate exchange using TLC data that had been collected during the course of the reaction. The first spot to form below the starting material (2) was 3 then 4 and 5. The last spot to form on the TLC was compound 6. The C9, bearing the primary OTMS group, was expected to be the first to exchange as observed in our previous work with aldohexoses;17 instead, the secondary hydroxyl group (C4) next to the NHAc was most reactive. Upon introduction of the C4 acetate, silyl exchange next occurred at the primary C9, as evidenced by formation of 4 on the TLC. Once the C9 acetate was introduced, the C8 was acetylated in favor of exchange of the anomeric ether. Thus, the order by which regioselective silyl exchange occurred was as follows: C4 (2°) > C9 (1°) > C8 (2°) > C2 (anomeric). The C-7 TMS ether did not exchange under these conditions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Preferred silyl ether/acetate exchange of Neu5Ac: C4 (2°) > C9 (1°) > C8 (2°) > C2 (anomeric).

Neu5Ac ReSET revealed completely different regioselectivity than previous work with pyranose sugars.16,17 In aldohexoses, the primary C6 typically exchanges first followed by the anomeric C1. After C1 exchange, C2 is usually next to react then further exchange occurs in a sequential manner around the pyranose ring. Witschi and co-workers also performed ReSET on N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc), which is an aldose sugar structurally similar to Neu5Ac in terms of bearing an NHAc group. In that case, the first exchange also occurred at the primary C6 rather than the anomeric position, which was proximal to the amide.16

The presence of NHAc in 2 presumably pulls electron density from the C4 O–Si bond, which allows for exchange to occur first at C4 in favor of the primary C9 position. Moreover, the presence of methylene protons at C3 assures a less sterically hindered environment than what is found in common pyranose sugars. Once C9 is acetylated, C8 is the next to react. Again, the electronic effect of the C9 ester group makes the C8 O–Si bond most susceptible to attack. The observation of C8 exchange in favor of the anomeric silyl ether group indicates that the quaternary center is not readily accessible. These experimental findings further illustrate the remarkable balance between steric and electronic effects of ReSET (Figure 2).17

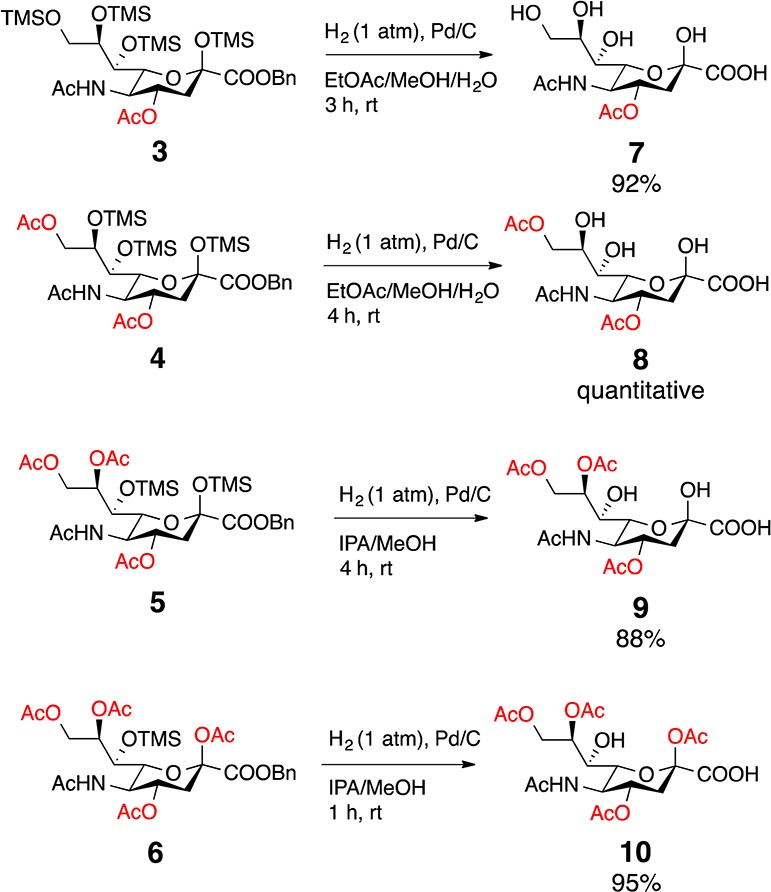

In targeting naturally occurring 7 and 8, our plan was to use methanolysis to deprotect the TMS silyl ethers first22,23 and then remove the benzyl ester. However, upon methanolysis, we observed slow reaction times in addition to transesterification. To avoid these complications, 3–6 were subjected to hydrogenation to first remove the benzyl ester. Fortuitously, the TMS groups were also deprotected under these conditions. While 3 and 4 readily reacted in a mixture of ethyl acetate, methanol and water, analogues 5 and 6 were sluggish in this solvent system. It is known that protic solvents enhance hydrogenation in comparison to aprotic organic solvents (e.g., ethyl acetate, acetonitrile), which can coordinate with the palladium metal reducing hydrogen adsorption.24 The combination of 2-propanol and methanol led to increased efficiency for TMS deprotection of 5 requiring only 4 h compared to 19 h when reacted in an ethyl acetate/methanol/water mixture. With this global deprotection protocol, we obtained the naturally occurring Neu4,5(Ac)2 (7) in 92% yield, Neu4,5,9(Ac)3 (8) quantitatively, and Neu4,5,8,9(Ac)4 (9) in 88% yield (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Deprotection of TMS and Bn Groups.

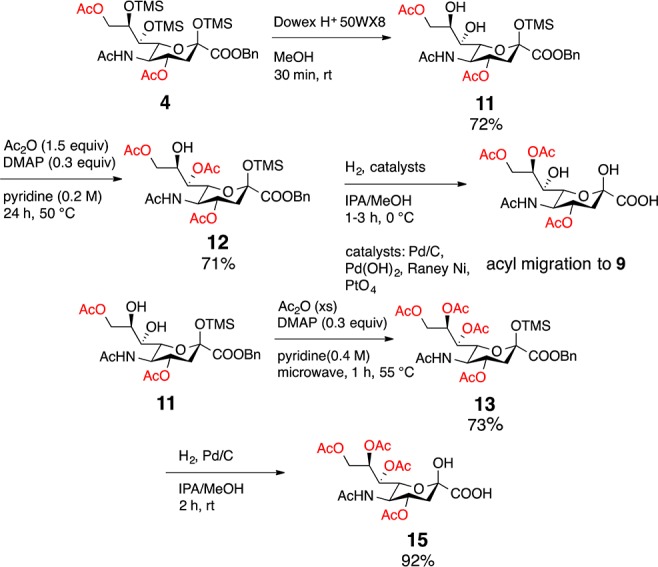

In pursuit of the synthesis of Neu4,5,7,8,9(Ac)5 (15), compound 4 was selectively deprotected to expose the C7 and C8 diol (11, Scheme 3). The anomeric silyl protecting group remained in tact presumably due to steric hindrance. Subjecting 11 to 1.5 equiv acetic anhydride gave selective acetylation of C7 (12), while excess acetic anhydride gave 13 (Scheme 3). Upon hydrogenolysis of 12, acyl migration from the 7-O-acetyl to the C8 position occurred affording compound 9. Attempts to avoid migration using various catalysts including palladium (98%), palladium hydroxide, platinum(IV) oxide, and Raney nickel were unsuccessful. C7 to C8 acyl migration occurred under all conditions, suggesting the C-8 acetate is a thermodynamic sink. Meanwhile, 13 was subjected to hydrogenation to remove the anomeric silyl and benzyl groups to afford naturally occurring 15 in 92% yield. This route allowed for an alternative synthesis of 15, which had been previously synthesized.25

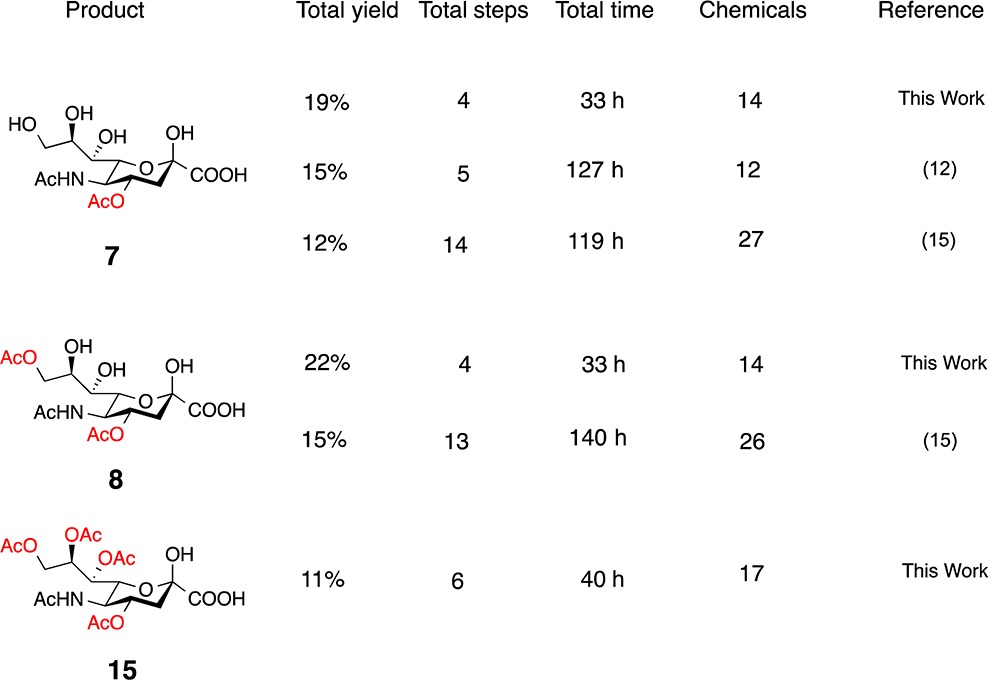

These experimental findings show unique expansion of ReSET toward structurally complex sugars like Neu5Ac while demonstrating a facile preparation of naturally occurring O-acetylated Neu5Ac analogues in the highest yields to date (Table 3). In addition to reducing the chemical reaction steps, time efficiency was increased by >75% compared to previous reports and the chemicals used for this reaction were reduced to approximately 50% (Table 3). Given our efforts to conserve valuable resources in the chemical research setting, this study validates ReSET as a step-, chemical-, and time- economical synthetic methodology. Analogues from ReSET may be used for future carbohydrate-based drug designs or as suitable standards that can expand the understanding of biology, immunology, and chemical functions.

Table 3. Summary of Previous and Current Syntheses of Naturally Occurring O-Acetylated Neu5Ac.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health, NIH Grant No. R01GM090262. NSF CRIF program (CHE - 9808183), NSF Grant No. OSTI 97-24412, and NIH Grant No. RR11973 provided funding for the NMR spectrometers used on this project. We thank Dr. Jerry Dallas (University of California, Davis) for help with the long-range HMBC NMR experiments and 2D NMR experiments.

Supporting Information Available

General experimental procedures, NMR, and mass spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Byrne G.; Donohoe G.; O’Kennedy R. Drug Discov. Today 2007, 12, 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Varki A. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010, 5, 163–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefel M.; Von Itzstein M. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 439–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M. In Molecular and Cellular Glycobiology; Oxford University Press: New York, 2000; pp 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Feizi T. Immunol. Rev. 2000, 173, 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angata T.; Varki A. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 471–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelm S.; Schauer R. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1997, 175, 137–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engstler M.; Schauer R.; Brun R. Acta. Trop. 1995, 59, 117–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer R.; Srinivasan G.; Wipfler D.; Kniep B.; Schwartz-Albiez R. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2011, 705, 525–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer R. Zoology 2004, 107, 49–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwersen M.; Dora H.; Kohla G.; Gasa S.; Schauer R. Biol. Chem. 2003, 384, 1035–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke P.; Mistry N.; Thomas G. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Meo C.; Priyadarshani U. Carbohydr. Res. 2008, 1540–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khedri Z.; Muthana M.; Li Y.; Muthana S.; Yu H.; Cao H.; Chen X. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 3357–3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa A.; Murase T.; Ogawa M.; Ishida H.; Kiso M. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 1990, 9, 415. [Google Scholar]

- Witschi M.; Gervay-Hague J. Org. Lett. 2010, 12194312–4315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H.-W.; Schombs M.; Witschi M.; Gervay-Hague J. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 9677–9688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wender P.; Verma V.; Paxton T.; Pillow T. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 40–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Newhouse T.; Baran P.; Hoffmann R. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 3010–3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wender P.; Miller B. Nature 2009, 460, 197–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat A.; Gervay-Hague J. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 2081–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schombs M.; Park F.; Du W.; Kulkarni S.; Gervay-Hague J. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeley C.; Bentley R.; Makita M.; Wells W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 2497–2507. [Google Scholar]

- Du W.; Kulkarni S.; Gervay-Hague J. Chem. Commun. 2007, 2336–2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R.; Lin C.; Gervay-Hague J. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 9083–9085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikawa T.; Sajiki H.; Hirota K. Tetrahedron 2004, 6901–6911. [Google Scholar]

- Kenkyusho N. Japanese patent 09-249682, Sep 22, 1997.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.