Abstract

Key Clinical message

Midgut volvulus can rarely present with acute chylous peritonitis. Common etiologies for chylous ascites need to be excluded before this diagnosis is made. Correction of the volvulus and peritoneal lavage suffice as treatment.

Keywords: Chylous ascites, ileum, intestinal volvulus, laparoscopy

Introduction

Acute chylous peritonitis is an extremely rare condition and since its first description by Renner [1] in 1910, there have been only a few anecdotal reports in literature. The occurrence of midgut volvulus in adults is also very uncommon and the presentation of a small bowel volvulus as an acute abdomen with chylous peritonitis has been reported only four times in English literature. We present a patient with volvulus of the small bowel with copious chylous ascites producing an aseptic chemical peritonitis and discuss the management of this rare and fascinating condition.

Case History/Examination

A 67-year-old man presented with a 1-day history of crampy central abdominal pain and obstipation. Clinically he was distended and tender. He had undergone a laparoscopic sigmoid colectomy for volvulus 10 years ago. He underwent emergent exploration laparoscopically.

Laparoscopy revealed copious milky white fluid in the abdomen (Fig.1) occupying both supra and infracolic compartments and both paracolic gutters. One liter of chyle was drained. A loop of ileum was attached by a band to the descending colon and had twisted on itself. This is seen on the CT scan (Fig.2). A thorough exploration of the abdomen was performed, running the entire bowel from duodeno-jejunal flexure to the rectum. The appendix was examined and was normal. Interestingly, the cecum was located in the right hypochondrium, representing some form of abnormal rotation. The liver, gallbladder, spleen, and pancreas were unremarkable. This being an extremely rare presentation, we proceeded to laparotomy to ensure we did not miss any underlying cause of chylous ascites. Laparotomy revealed a viable bowel segment with a peculiar white staining of both mesenteric leaves (Fig.3). The bowel was unwound in a counter clockwise direction after dividing the band attaching it to the colon. The retroperitoneum was examined and revealed absence of any lymphadenopathy, lymphatic malformations or cysts. Thorough lavage was performed and the abdomen closed without drainage. He recovered uneventfully and was discharged on the third postoperative day.

Figure 1.

Laparoscopic picture of chylous ascites.

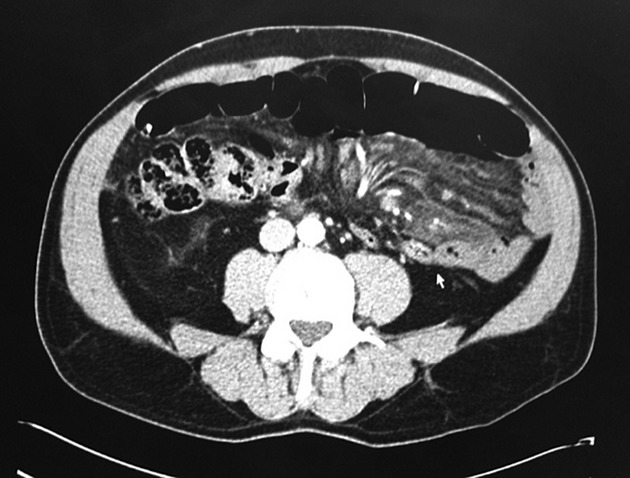

Figure 2.

CT Scan showing whirl sign of small bowel volvulus.

Figure 3.

Chyle stained ileal mesentery.

Biochemical analysis of the fluid confirmed it to be chyle with an elevated triglyceride level. Gram's stain revealed a few polymorphs but no bacteria. Cultures did not return any growth.

Discussion

Midgut volvulus presenting with acute chylous peritonitis is known in children, but is extremely rare in adults. Vasko and Tapper [2] in their review of 104 patients with chylous ascites note that congenital anomalies of intestinal rotation account for the majority of chylous ascites in children [39%]. Adults on the other hand have either a neoplastic or inflammatory etiology for chyle accumulation in two-thirds of cases.

It is postulated that gut volvulus causes lymphatic obstruction due to low pressures in this system and exudation of lymph and even rupture leading to chylous ascites [3].The lymphatic channels converge toward the root of the mesentery and run along the superior mesenteric artery to the cistern chyli and get easily occluded when the intestine torses. Simple occlusion of the lymphatics, however, does not cause chylous effusions as shown by Blalock [4] in experimental ligation of the thoracic duct and patients who develop a chylous outpouring possibly have some congenital weakness of their lymphatics which predisposes them to this condition. In the majority of cases, correction of the volvulus and lavage suffice. It is important to carefully look for and rule out the more common causes of chylous ascites: lymphatic obstruction due to tumors, cirrhosis, tuberculosis, filariasis, and ectatic lymphatics due to congenital malformations and cysts apart from trauma either external or due to abdominal surgery which is usually evident as a etiologic factor[5]. Madding [6] distinguished between acute chylous peritonitis which is usually idiopathic and frequently occurs following ingestion of a very heavy fatty meal and true or progressive chylous ascites which is due to lymphatic obstruction due to tumors or infections.

When confronted with milky white fluid in the abdomen, three possibilities are to be entertained: chyle, chyliform ascites, and pseudochyle [7]. Chyle is milky and odorless with an elevated white cell count averaging about 5000 per cubic mm and is sterile on culture. An elevated triglyceride content averaging 2–8 times higher than plasma concentration is pathognomic. A positive stain of the fat globules with Sudan red is characteristic [8]. Chyliform ascites contains lecithin-globulin complexes due to fatty degeneration of cells and pseudochyle is fluid which is milky due to admixture with pus.

Conclusions

It is important to note that midgut volvulus can present with chylous peritonitis. It is equally if not more important to look for underlying more common conditions such as tumors and malformations which may explain the chylous ascites, always remembering that uncommon manifestations of common diseases are more common than common manifestations of uncommon diseases. Treatment following the classic principles of surgery for volvulus and thorough lavage leads to satisfactory outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Ajit Pai would like to thank the foundation for surgical fellowships for providing the opportunity to carry out fellowship training at the institute of affiliation.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Renner A. [Chylus als Bruchwasser beim eingeklemmten Bruch] Beitr Klin Chir. 1910;70:695–698. German. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasko JS, Tapper RI. The surgical significance of chylous ascites. Arch. Surg. 1967;95:355–368. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1967.01330150031006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yater WM. Non-traumatic chylothorax and chylopericardium; review and report of a case due to carcinomatous thromboangitis obliterans of the thoracic duct and upper great veins. Ann. Int. Med. 1935;9:600. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blalock A, Cunningham R, Robinson C. Experimental Production of Chylothorax by Occlusion of the Superior Vena Cava. Ann. Surg. 1936;104:359. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193609000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohri SK, Patel T, Desa LA, Spencer J. The management of postoperative chylous ascites. A case report and literature review. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1990;12:693–697. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199012000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madding GF, McLaughlin RF, McLaughlin RF., Jr Acute chylous peritonitis. Ann. Surg. 1958;147:419–422. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195803000-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murugan K, Spence RA. Chylous peritonitis with small bowel obstruction. Ulster Med. J. 2008;77:132–133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward PC. Interpretation of ascitic fluid data. Postgrad. Med. 1982;71:171–173. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1982.11715995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]