Abstract

Introduction

In 2009, the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) convened a select panel of experts to develop an evidence-based set of guidelines for patients suffering from lifelong premature ejaculation (PE). That document reviewed definitions, etiology, impact on the patient and partner, assessment, and pharmacological, psychological, and combined treatments. It concluded by recognizing the continually evolving nature of clinical research and recommended a subsequent guideline review and revision every fourth year. Consistent with that recommendation, the ISSM organized a second multidisciplinary panel of experts in April 2013, which met for 2 days in Bangalore, India. This manuscript updates the previous guidelines and reports on the recommendations of the panel of experts.

Aim

The aim of this study was to develop clearly worded, practical, evidenced-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of PE for family practice clinicians as well as sexual medicine experts.

Method

A comprehensive literature review was performed.

Results

This article contains the report of the second ISSM PE Guidelines Committee. It offers a new unified definition of PE and updates the previous treatment recommendations. Brief assessment procedures are delineated, and validated diagnostic and treatment questionnaires are reviewed. Finally, the best practices treatment recommendations are presented to guide clinicians, both familiar and unfamiliar with PE, in facilitating treatment of their patients.

Conclusion

Development of guidelines is an evolutionary process that continually reviews data and incorporates the best new research. We expect that ongoing research will lead to a more complete understanding of the pathophysiology as well as new efficacious and safe treatments for this sexual dysfunction. We again recommend that these guidelines be reevaluated and updated by the ISSM in 4 years. Althof SE, McMahon CG, Waldinger MD, Serefoglu EC, Shindel AW, Adaikan PG, Becher E, Dean J, Giuliano F, Hellstrom WJG, Giraldi A, Glina S, Incrocci L, Jannini E, McCabe M, Parish S, Rowland D, Segraves RT, Sharlip I, and Torres LO. An update of the International Society of Sexual Medicine's guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of premature ejaculation (PE). Sex Med 2014;2:60–90.

Keywords: Premature Ejaculation, Definition of PE, Diagnosis of PE, Etiology of PE, Pharmacotherapy of PE, Prevalence of PE, Psychotherapy of PE

Introduction

In 2009, the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) convened a select panel of experts to develop an evidence-based set of guidelines for patients suffering from lifelong premature ejaculation (LPE) [1]. That document reviewed definitions, etiology, impact on the patient and partner, assessment, and pharmacological, psychological, and combined treatments. It concluded by recognizing the continually evolving nature of clinical research and recommended a subsequent guideline review and revision every fourth year.

Consistent with that recommendation, the ISSM organized a second multidisciplinary panel of experts in April 2013, which met for 2 days in Bangalore, India. The committee members were selected to assure diversity of discipline, balance of opinion, knowledge, gender, and geography. Twenty members consisting of nine urologists, three psychiatrists, three psychologists, one family practice physician, one endocrinologist, one sexual medicine physician, one radiation oncologist, and one pharmacologist comprised the group. The committee was chaired by Chris McMahon, MD.

Prior to the meeting, the committee members received a comprehensive literature review and were asked to critically assess the previous guidelines. Members were assigned specific topic for presentation, and a writing committee was chosen to craft this document. Quality of evidence and the strength of recommendation were graded using the Oxford Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine system [2].

The meeting was supported by an unrestricted grant from Johnson & Johnson (New Brunswick, NJ, USA), the manufacturer of dapoxetine. ISSM required complete independence from industry; there were no industry representatives at the meeting and there was no attempt by industry to influence the writing process at any time [3]. Members were required to declare in advance any conflicts of interests.

Definitions of Premature Ejaculation (PE)

Several definitions for PE exist, having been drafted by various professional organizations or professionals 4–11 (see Table 1), and most include the PE subtypes of lifelong and acquired (PE symptoms beginning after a period of normal ejaculatory function). The major criticisms of the extant definitions included their failure to be evidence based, lack of specific operational criteria, excessive vagueness, and reliance on the subjective judgment of the diagnostician [12]. Nonetheless, three common constructs underlie most definitions of PE: (i) a short ejaculatory latency; (ii) a perceived lack of control or inability to delay ejaculation, both related to the broader construct of perceived self-efficacy; and (iii) distress and interpersonal difficulty to the individual and/or partner (related to the ejaculatory dysfunction) [12].

Table 1.

Definitions of premature ejaculation established through consensus committees and/or professional organizations

| Definition | Source |

|---|---|

| A male sexual dysfunction characterized by ejaculation that always or nearly always occurs prior to or within 1 minute of vaginal penetration, either present from the first sexual experience or following a new bothersome change in ejaculatory latency, and the inability to delay ejaculation on all or nearly all vaginal penetrations, and negative personal consequences, such as distress, bother, frustration, and/or the avoidance of sexual intimacy. | International Society of Sexual Medicine, 2013 |

| A. Persistent or recurrent pattern of ejaculation occurring during partnered sexual activity within approximately 1 minute following vaginal penetration and before the individual wishes it (Note: Although the diagnosis of premature [early] ejaculation may be applied to individuals engaged in non-vaginal sexual activities, specific duration criteria have not been established for these activities). | DSM-5, 2013 |

| B. The symptom in Criterion A must have been present for at least 6 months and must be experienced on almost all or all ( approximately 75%–100%) occasions of sexual activity (in identified situational contexts or, if generalized, in all contexts). | |

| C. The symptom in Criteria A causes clinically significant distress in the individual. | |

| D. The sexual dysfunction is not better explained by a nonsexual mental disorder or as a consequence of severe relationship distress or other significant stressors and is not attributable to the effects of a substance/medication or another medical disorder. | |

| Persistent or recurrent ejaculation with minimal sexual stimulation, before, on or shortly after penetration and before the person wishes it. The condition must also cause marked distress or interpersonal difficulty and cannot be due exclusively to the direct effects of a substance. | DSM-IV-TR, 2000 |

| For individuals who meet the general criteria for sexual dysfunction, the inability to control ejaculation sufficiently for both partners to enjoy sexual interaction, manifest as either the occurrence of ejaculation before or very soon after the beginning of intercourse (if a time limit is required, before or within 15 seconds) or the occurrence of ejaculation in the absence of sufficient erection to make intercourse possible. The problem is not the result of prolonged absence from sexual activity. | International Statistical Classification of Disease, 10th Edition, 1994 |

| The inability to control ejaculation for a “sufficient” length of time before vaginal penetration. It does not involve any impairment of fertility, when intravaginal ejaculation occurs. | European Association of Urology. Guidelines on Disorders of Ejaculation, 2001 |

| Persistent or recurrent ejaculation with minimal stimulation before, on, or shortly after penetration, and before the person wishes it, over which the sufferer has little or no voluntary control, which causes the sufferer and/or his partner bother or distress. | International Consultation on Urological Diseases, 2004 |

| Ejaculation that occurs sooner than desired, either before or shortly after penetration, causing distress to either one or both partners. | American Urological Association Guideline on the Pharmacologic Management of Premature Ejaculation, 2004 |

DSM-5 definition reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved.

Because of the discontent with the existing PE definitions, as well as pressure from regulatory agencies concerning the inadequacy of the definitions, the ISSM convened in 2007 and again in 2013, a meeting of experts to develop a definition grounded in clearly definable scientific criteria [12]. After carefully reviewing the literature, the committee proposed a unified definition of both LPE and acquired PE (APE): It “is a male sexual dysfunction characterized by:

ejaculation that always or nearly always occurs prior to or within about 1 minute of vaginal penetration from the first sexual experience (LPE), OR a clinically significant reduction in latency time, often to about 3 minutes or less (acquired premature ejaculation);

the inability to delay ejaculation on all or nearly all vaginal penetrations; and

negative personal consequences, such as distress, bother, frustration, and/or the avoidance of sexual intimacy.” Level of evidence (LOE 1a)

The definition applies to both LPE and APE but is limited to intravaginal sexual activity, as correlations between coital, oral sex, and masturbatory latencies are not consistently high. In addition, it does not define PE when men have sex with men. The committee concluded that there was insufficient information available to extend the definition to these other situations or groups. (LOE 5d)

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) [13] definition of premature (early) ejaculation, published in 2013, is consistent with the ISSM definition and includes the approximately 1-minute intravaginal ejaculatory latency time (IELT) criteria as well as the inclusion of distress. It also asks the clinician to specify the subtypes of lifelong and acquired, generalized, or situational as well as the severity of the dysfunction.

Anteportal ejaculation is the term applied to men who ejaculate prior to vaginal penetration and is considered the most severe form of PE. Such men or couples typically present when they are having difficulty conceiving children. It is estimated that between 5% and 20% of men with LPE suffer from anteportal PE [14].

The committee recognized that some men who self-diagnose PE and present for treatment fail to fulfill the ISSM criteria for PE. Waldinger has proposed two additional “subtypes” of men who are distressed about their ejaculatory function but do not meet the diagnostic criterion for PE. He designated them as variable PE (VPE) and subjective PE (SPE) [10,15]. These subtypes should be considered provisional; however, we believe these categories may help health care professionals (HCPs) address the concerns of men who do not qualify for the diagnosis of PE but are seeking help. VPE is characterized by short ejaculatory latency that occurs irregularly and inconsistently with some subjective sense of diminished control of ejaculation. This subtype is not considered a sexual dysfunction but rather a normal variation in sexual performance. SPE is characterized by one or more of the following: (i) subjective perception of consistent or inconsistent short IELT; (ii) preoccupation with an imagined short ejaculatory latency or lack of control over the timing of ejaculation; (iii) actual IELT in the normal range or even of longer duration (i.e., an ejaculation that occurs after 5 minutes); (iv) ability to control ejaculation (i.e., to withhold ejaculation at the moment of imminent ejaculation) that may be diminished or lacking; and (v) the preoccupation that is not better accounted for by another mental disorder. (LOE 5d)

Epidemiology

PE has been recognized as a syndrome for well over 100 years [16]. Despite this long history, the prevalence of the condition remains unclear. This ambiguity derives in large part from the difficulty defining what constitutes clinically relevant PE. Vague definitions without specific operational criteria, different modes of sampling, and nonstandardized data acquisition have led to tremendous variability in estimated prevalence 1,12,17–19. The sensitive nature of PE further hampers the reliability of epidemiologic studies; the small fraction of the male population willing to answer questions concerning their sexual lives may not be representative of the larger population of men [20,21]. In addition, some men with genuinely rapid ejaculation times may be reluctant to report this complaint due to worry about social stigmatization [22]. Conversely, healthy individuals may report PE because of the incentives provided by researchers, the belief that they will benefit from participation in a survey [22], or a misunderstanding of what is typical with respect to ejaculatory latency in real-world sexual encounters [8]. Aside from difficulties with definitions and sampling, there is marked variability in distress related to early ejaculation between individual men and across cultures [8]. It is likely that some men may report early ejaculation when asked a single-item question on an epidemiological survey while not experiencing bother sufficient to justify medical attention. Based on the absence of distress, such men would not meet the current criteria for PE [12,23].

Peer-reviewed studies on the prevalence of PE published prior to March 2013 are summarized in Table 2 26,27,29,30,33–35,37–41,43–46,48–59. Most of these studies utilized the DSM, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (IV-TR) definition and characterized PE as the “most common male sexual dysfunction,” with a prevalence rate of 20–30% 20–22. As the DSM-IV-TR definition lacks objective diagnostic criteria, the high prevalence of PE reported in many of these surveys is a source of ongoing debate [30,33,40,46,53,55,58,59]. It is, however, unlikely that the PE prevalence is as high as 20–30% based on the relatively low number of men who present for treatment of PE [21,54,57].

Table 2.

The prevalence rates of premature ejaculation

| Date | Author | Method of data collection | Method of sample recruitment | Specific operational criteria | Prevalence rate | Number of men |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | Dunn et al. [24] | General practice registers—random stratification | Having difficulty with ejaculating prematurely | 14% (past 3 months) | 617 | |

| 31% (lifetime) | 618 | |||||

| 1999 | Laumann et al. (NHSLS) [22] | Interview | NA | Climaxing/ejaculating too rapidly during the past 12 months | 31% | 1,410 |

| 2002 | Fugl-Meyer and Fugl-Meyer [25] | Interview | Population register | NA | 9% | 1,475 |

| 2004 | Rowland et al. [26] | Mailed questionnaire | Internet panel | DSM-IV | 16.3% | 1,158 |

| 2004 | Nolazco et al. [27] | Interview | Invitation to outpatient clinic | Ejaculating fast or prematurely | 28.3% | 2,456 |

| 2005 | Laumann et al. (GSSAB) [20] | Telephone-personal interview/mailed questionnaires | Random (systematic) sampling | Reaching climax too quickly during the past 12 months | 23.75% (4.26% frequently) | 13,618 |

| 2005 | Basile Fasolo et al. [28] | Clinician based | Invitation to outpatient clinic | DSM-IV | 21.2% | 12,558 |

| 2005 | Stulhofer et al. [29] | Interview | Stratified sampling | Often ejaculating in less than 2 minutes | 9.5% | 601 |

| 2007 | Porst et al. (PEPA) [21] | Web-based survey Self-report | Internet panel | Control over ejaculation Distress | 22.7% | 12,133 |

| 2008 | Shindel et al. [30] | Questionnaire | Male partners of infertile couples under evaluation | Self report premature ejaculation | 50% | 73 |

| 2009 | Brock et al. [31] | Telephone interview | Web-based survey | DSM-III | 16% | 3,816 |

| Control | 26% | |||||

| Distress | 27% | |||||

| 2010 | Traeen and Stigum [32] | Mailed questionnaire + Internet | Web interview + randomization | NA | 27% | 11,746 + 1,671 |

| 2010 | Son et al. [33] | Questionnaire | Internet panel (younger than 60) | DSM-IV | 18.3% | 600 |

| 2010 | Amidu et al. [34] | Questionnaire | NA | NA | 64.7% | 255 |

| 2010 | Liang et al. [35] | NA | NA | ISSM | 15.3% | 1,127 |

| 2010 | Park et al. [36] | Mailed questionnaire | Stratified sampling | Suffering from PE | 27.5% | 2,037 |

| 2010 | Vakalopoulos et al. [37] | One-on-one survey | Population-based cohort | EED | 58.43% | 522 |

| ISSM lifelong PE | 17.7% | |||||

| 2010 | Hirshfeld et al. [38] | Web-based survey | Online advertisement in the United States and Canada | Climaxing/ejaculating too rapidly during the past 12 months | 34% | 7,001 |

| 2011 | Christensen et al. [39] | Interview + questionnaire | Population register (random) | NA | 7% | 5,552 |

| 2011 | Serefoglu et al. [40] | Interview | Stratified sampling | Complaining about ejaculating prematurely | 20.0% | 2,593 |

| 2011 | Son et al. [33] | Questionnaire | Internet panel | Estimated IELT ≤5 minutes, inability to control ejaculation, distress | 10.5% | 334 |

| 2011 | Tang and Khoo [41] | Interview | Primary care setting | PEDT ≥ 9 | 40.6% | 207 |

| 2012 | Mialon et al. [42] | Mailed questionnaire | Convenience sampling (18–25 years old) | Control over ejaculation Distress | 11.4% | 2,507 |

| 2012 | Shaeer and Shaeer [43] | Web-based survey | Online advertisement in Arabic countries | Ejaculate before the person wishes to ejaculate at least sometimes | 83.7% | 804 |

| 2012 | Shindel et al. [44] | Web-based survey | Online advertisement targeted to MSM + distribution of invitation to organizations catering to MSM | PEDT ≥ 9 | 8–12% | 1,769 |

| 2012 | McMahon et al. [45] | Computer-assisted interviewing, online, or in-person self-completed | NA | PEDT ≥ 11 | 16% | 4,997 |

| Self-reported (always/nearly-always) | 13% | |||||

| 2012 | Lotti et al. [46] | Interview | Men seeking medical care for infertility | PEDT ≥ 9 | 15.6% | 244 |

| 2013 | Zhang et al. [47] | Interview | Random stratified sample of married men aged 30–60 | Self-reported premature ejaculation | 4.7% | 728 |

| 2013 | Lee et al. [48] | Interview | Stratified random sampling | PEDT ≥ 11 | 11.3% | 2,081 |

| Self-reported | 19.5% | |||||

| IELT < 1 minute | 3% | 1,035 | ||||

| 2013 | Shaeer [49] | Web-based survey | Online advertisement in the United States | PEDT ≥ 11 | 50% | 1,133 |

| Self-report any PE | 78% | |||||

| Self-reported “always” or “mostly” | 14% | |||||

| 2013 | Gao et al. [50] | Interview | Random stratified sample of monogamous heterosexual men in China | Self-reported premature ejaculation | 25.8% | 3,016 |

| 2013 | Hwang et al. [51] | Survey of married couples | Married heterosexual couples in Korea | Estimated IELT < 2 minutes | 21.7% | 290 |

| PEDT ≥ 11 | 12.1% | |||||

| 2013 | Vansintejan et al. [52] | Web-based survey | Online and flyer advertisements to Belgian men who have sex with men (only HIV+ men in this study) | IPE score ≤ 50% of total possible IPE score ≤ 66% of total possible | 4% 18% | 72 |

DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; EED = early ejaculatory dysfunction; GSSAB = Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; IELT = intravaginal ejaculatory latency time; ISSM = International Society of Sexual Medicine; IPE = Index of Premature Ejaculation; MSM = men who have sex with men; NA = North American; NHSLS = National Health and Social Life Survey; PE = premature ejaculation; PEDT = Premature Ejaculation Diagnostic Tool; PEPA = premature ejaculation prevalence and attitudes

In two online surveys, one of Arabic-speaking men in the Middle East, the second of US men, 82.6% and 78% of participants, respectively, reported some degree of PE [43,49]. This high rate of PE is best accounted for by the inclusion of men with VPE or SPE. In the Middle Eastern study, only 15.3% of men reported that they “always” ejaculated before they wished, while 46% and 21% described themselves, respectively, as “sometimes” or “mostly” ejaculating before they wished. In the US study, the 78% of men acknowledging some degree of PE decreased to 14.4% when combining the “always' or “mostly” group.

In two five-nation (Turkey, United States, United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Spain) studies of IELT in men from the general population, the median IELT was 5.4 minutes (range 0.55–44.1 minutes) and 6.0 minutes (range 0.1–52.7 minutes), respectively [8,56]. In these samples, 2.5% of men had an IELT of less than 1 minute and 6% of less than 2 minutes PE [1,8,56]. These percentages are not necessarily equivalent to the prevalence of LPE because there was no assessment of distress or chronicity [8,56].

Based on these data and the ISSM and DSM-5 definition of PE, in terms of an IELT of about 1 minute, the prevalence of LPE is unlikely to exceed 4% of the general population. (LOE 3b)

Serefoglu et al. were the first to report prevalence rates for the four PE subtypes [40,58,59] as described by Waldinger and Schweitzer [10,15,23] A 2010 study reported the distribution of PE subtypes in PE patients admitted to a urology outpatient clinic in Turkey, while a subsequent 2011 study reported the prevalence of PE subtypes in the general male population in Turkey randomly selected by a proportional sampling method according to postal code [40,58]. This research design was replicated by Zhang et al. [53] and Gao et al. [50] in a Chinese population. In both these studies, a relatively high proportion of men (20.0% in Turkey and 25.8% in China) acknowledged a concern with ejaculating too quickly, consistent with previously reported prevalence studies of PE [21]. Employing Waldinger's definition [10,23], in the general male population of both countries, the prevalence of LPE was 2.3% and 3%, whereas the prevalence of APE was 3.9% and 4.8%, respectively [40,50]. The prevalence of VPE and SPE was 8.5% and 5.1% in Turkey and 11% and 7% in China, respectively [40,50].

An approximately 5% prevalence of APE and LPE in general populations is consistent with epidemiological data indicating that around 5% of the population have an ejaculation latency less than 2 minutes. (LOE 3b)

There are significant differences between PE prevalence rates in the general population and clinic settings because the majority of men with PE do not seek treatment. Of patients presenting for treatment, 36% to 63% have LPE and 16% to 28% have APE [53,58]. The prevalence of VPE and SPE among these clinic patients was 14.5% and 6.9% in the Turkish clinic and 12.7% and 23.5% in the Chinese clinic patients [53,58].

Etiology

Early PE investigators did not often differentiate between APE and LPE, nor were there objective criteria for what constituted PE in general [4,6]. With the development of the ISSM definition [12] and two new PE syndromes VPE and SPE [15,57], it is increasingly important to clarify which syndrome is being addressed in etiological studies.

Historical ambiguity on what constitutes early ejaculation has led to a diverse list of potential and established etiological factors [1]. Classically, PE was thought to be psychologically or interpersonally based, due in large part to anxiety or conditioning toward rapid ejaculation based on rushed early sexual experiences [6,60]. Over the past two decades, somatic and neurobiological etiologies for early ejaculation have been hypothesized. Myriad biological factors have been proposed to explain PE including: hypersensitivity of the glans penis [61], robust cortical representation of the pudendal nerve [62], disturbances in central serotonergic neurotransmission [63,64], erectile difficulties and other sexual comorbidities [65,66], prostatitis [67], detoxification from prescribed medications [68,69], recreational drugs [70], chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) [71], and thyroid disorders [72,73]. It is noteworthy that none of these etiologies has been confirmed in large scale studies.

Neurobiology of PE

Serotonin is the neurotransmitter of greatest interest in the control of ejaculation and has the most robust data in animal and human models. Waldinger hypothesized that lifelong early ejaculation in humans may be explained by a hyposensitivity of the 5-HT2C and/or hypersensitivity of the 5-HT1A receptors [19]. As serotonin tends to delay ejaculation, men low in 5-HT neurotransmission and/or 5-HT2C receptor hyposensitivity may have intrinsically lower ejaculatory thresholds. (LOE 3b)

Serotonin dysregulation as an etiological hypothesis for LPE has been postulated to explain only a small percentage (2–5%) of complaints of PE in the general population [74]. (LOE 2a)

Dopamine and oxytocin also appear to play important roles in ejaculation; the biology of these neurotransmitters in relation to ejaculation is less well studied, but in animal studies, both appear to have a stimulatory effect on ejaculation [75,76]. (LOE 3b)

In the spinal cord, lumbar spinothalamic neurons have been implicated as essential to the ejaculatory reflex in rats 77–80 constituting a spinal generator of ejaculation [81] (LOE2a). There is also preliminary evidence that such a neural organization also exists in humans [82]. The relevance of these findings to PE is not yet apparent, but this remains a fertile area for further translational research.

Genetics of PE

Genetic variations have been proposed to bring about differences in the neurobiological factors associated with PE. A genetic cause for PE was first hypothesized in 1943 based on family prevalence studies [60]. Waldinger et al. confirmed this finding by surveying family members of 14 men with a lifelong IELT less than 1 minute. Data on ejaculation latency in these male relatives were obtained by interview (n = 11) or “family history” (n = 6). Lifelong IELT of less than 1 minute was found in 88% of these first-degree male relatives of men with LPE [83].

In 2007, Jern et al. reported on genetic and environmental risk factors for ejaculation disturbances in 1,196 Finnish twins [84]. Modeling of etiological factors for early ejaculation (based on a subjective symptom scale) suggested a moderate additive genetic influence on propensity toward early ejaculation; however, a large portion of the variance in the frequency of early ejaculation was related to non-shared environmental variance, suggesting that genetic influences may create a diathesis or predisposition to PE rather than a direct cause-and-effect relationship [84].

The first DNA-based study on PE was performed by Janssen et al. in 89 Dutch men with LPE (confirmed by stopwatch IELT) compared with a cohort of mentally and physically healthy Dutch Caucasian men [85]. The target of this assessment was a gene polymorphism for the serotonin transporter protein (5-HTTLPR). This polymorphism has long (L) and short (S) allelic variants; the L alleles lead to greater transcriptional activity and hence decreased synaptic serotonin. In the LPE group, men homozygous for the L allele had ejaculation latencies that were half as long as men with the SL or SS genotypes. Given that the L allele leads to reduced synaptic serotonin, this finding is consistent with our current understanding of the influence of serotonin on ejaculation latency [85]. However, there was no difference in the prevalence of the LL, SL, and SS genotypes in men with LPE compared with their prevalence in the general male Dutch population, which suggests that this polymorphism alone cannot account for PE [85]. Follow-up studies on this same gene locus from other investigators have been mixed, with one report [86] being consistent with Janssen et al.'s findings, another reporting no association between 5-HTTLPR allele type and early ejaculation [87], and another study finding the exact opposite relationship between ejaculation latency and L vs. S allele carries [88].

A new body of research on tandem repeats of the dopamine transporter gene (DAT-1) as a modulator of ejaculation latency has emerged 89–91. Men with longer tandem repeat lengths have greater transcription of the transporter and hence, less synaptic dopamine activity [89]. Santtila et al. reported that men with longer tandem repeats were more likely to endorse symptoms consistent with early ejaculation [89]. A few studies, mainly performed in general male twin studies, have investigated polymorphism receptors for serotonin, oxytocin, and/or vasopressin [92]. Preliminary findings have not indicated a marked preponderance of any one genetic polymorphism in men with symptoms of early ejaculation 92–94.

The current body of evidence suggests that individual genetic polymorphisms exert a minor, if any, effect on ejaculation latency. Men with numerous genetic variants may be predisposed to development of PE, but data remain scant and controversial. (LOE 2a)

Special Patient Populations

Thyroid Hormones

Data from animal studies suggest anatomic and physiologic interactions between brain dopamine and serotonin systems and the hypothalamic-pituitary thyroid axis 95–97. Corona et al. and Carani et al. reported a significant correlation between APE and suppressed thyroid-stimulating hormone and high thyroid hormone values in andrological and sexological patients [72,73]. After normalizing thyroid function in hyperthyroid men, the prevalence of APE fell from 50% to 15% [72]. These data have been confirmed in several other reports 72,98–101. However, no link has been found between thyroid hormones and PE in a large cohort of men with LPE [102].

Hyperthyroidism (an acquired condition) has no role in LPE and has been found to be associated with APE in extremely few patients [103]. (LOE 2a)

Other Hormones

Although it is well established that male reproduction and sexuality are hormonally regulated, the endocrine control of the ejaculatory reflex is still not completely clarified. Recent studies on large populations indicate that the endocrine system is involved in the control of ejaculatory function and that prolactin (PRL) and testosterone play independent roles [100]. In particular, in a consecutive series of 2,531 outpatients consulting for sexual dysfunctions, PRL in the lowest quartile levels is associated with APE and anxiety symptoms [104]. Additionally, higher testosterone levels correlate with PE, while lower androgenization is related to delayed ejaculation [105].

Both hypoprolactinemia and relatively high testosterone levels cannot be considered etiologies of APE. The relationship between these hormonal abnormalities and PE is unclear. (LOE 2a)

Prostatitis

Twenty-six to 77% of men with chronic prostatitis (CP) or CPPS report early ejaculation [71,106,107]. Prostatic inflammation and chronic bacterial prostatitis have been reported as common findings in men with APE [67,108]. Considering the role of the prostate in the ejaculatory mechanism, a direct influence of the local inflammation in the pathogenesis of a few cases of APE seems possible [109].

The mechanism linking CP and PE is unknown, and there are some methodological limitations of the existing data. While physical and microbiological examination of the prostate expression in men with painful ejaculation or CP/CPPS is recommended, there is insufficient evidence to support routine screening of men with PE for this condition. (LOE 3a)

Erectile Dysfunction

Patients may mislabel or confuse the syndromes of PE and erectile dysfunction (ED). Examples include patients who say they have ED because they are unable to rapidly achieve a second erection after ejaculation. Similarly, some men with ED may self-report having PE because they rush intercourse to prevent loss of their erection and consequently ejaculate rapidly. This may be compounded by the presence of high levels of performance anxiety related to their ED, which serves to worsen their prematurity.

PE and ED may be comorbid conditions in some men [66]. In a global study of 11,205 men from 29 countries, Laumann et al. reported that a history of “sometimes” or “frequently” experiencing difficulty attaining and maintaining erections was independently predictive of “sometimes” or “frequently” experiencing early ejaculation within the past year. This relationship occurred across all regions, with odds ratios ranging from 3.7 to 11.9 [20]. Smaller studies from general and clinic populations have also reported this association between self-reported PE and self-reported ED 31,35,43,45,110–112, as determined by ED and PE patient-reported outcomes (PROs) [41,45,48]. Conversely, some population studies have not detected an association between ED and PE [30,32,44,46,113].

In an integrated analysis of two double-blind placebo controlled trials of dapoxetine for PE (DSM criteria and IELT < 2 minutes), the prevalence of ED was higher in men with APE vs. LPE (24% vs. 15%) [114]. Men with mild ED had less control over ejaculation compared with men with no ED and LPE [114]. This relationship was most pronounced in men with LPE and mild ED.

Comorbid ED is associated with more severe PE symptoms. In a stopwatch study of 78 men with LPE, McMahon reported that men with a normal Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM, a metric for assessment of ED risk) had a significantly greater geometric mean IELT compared with men with an abnormal SHIM suggestive of ED (18 seconds vs. 11 seconds, respectively) [115].

As in so many other areas of PE research, interpretation of data on the association between ED and PE is limited by varied definitions of PE and the means employed to assess PE.

While ED is unlikely as a comorbidity or etiological factor for LPE, there are data to support that APE is associated with ED 114,116–119 (LOE 3b). In such cases, men may experience rapid ejaculation due to performance anxiety, or due to deliberate intensification of stimulation so as to complete ejaculation before loss of tumescence (LOE 5).

Men with comorbid ED and PE may manifest a more severe variant of each disorder; furthermore, such men may experience lower sexual satisfaction and diminished response to treatment of PE [114]. (LOE 2a)

PE in Men Who Have Sex with Men

Data on the prevalence of PE in men who have sex with men (MSM) are relatively sparse. Existing studies suggest that a substantial proportion of MSM report PE and associated sexual bother. In some cases, ejaculatory dysfunction in MSM has been associated with higher risk of sexual behavior and/or social recrimination [120]. Most contemporary studies suggest a similar prevalence of concern about early ejaculation in MSM when compared with men who have sex with women only (MSW) [44]. Some older studies have suggested that the rate of distressing ejaculation problems in MSM is lower than in MSW [121]. However, differences in relationships and sexual activities may be responsible for some of these purported differences [122].

There are no stopwatch studies of ejaculation latency in MSM with or without ejaculation concerns. While there is no compelling evidence that MSM experience ejaculatory dysfunction differently than their MSW counterparts, more research is needed.

Psychological Factors

Psychological and interpersonal factors may cause or exacerbate PE. These factors may be developmental (e.g., sexual abuse, attitudes toward sex internalized during childhood), individual psychological factors (e.g., body image, depression, performance anxiety, alexithymia), and/or relationship factors (e.g., decreased intimacy, partner conflict) 123–125. There has been limited research on causality; most studies have been cross-sectional and hence can only report association. Obviously, developmental variables are likely to predate clinical PE, but it is conceivable that an intermediate factor secondary to the developmental history mediates the development of PE.

It is plausible that psychological factors may lead to PE or vice versa. It is likely that for many men, the relationship is reciprocal with either PE or the other factor causing exacerbation of the other. For example, performance anxiety may lead to PE, which then further exacerbates the original performance anxiety. (LOE 5d)

Importance of Partners and the Impact of PE on the Partner's Sexual Function

Inclusion of the partner in the treatment process is an important but not a mandatory ingredient for treatment success [118,126]. Some patients may not understand why clinicians wish to include the partner, and some partners may be reluctant to join the patient in treatment. However, if partners are not involved in treatment, they may be resistant to changing the sexual interaction. A cooperative partner augments the power of the treatment, and this likely leads to an improvement in the couple's sexual relationship, as well as the broader aspects of their relationship. There are no controlled studies on the impact of involving partners in treating PE. However, a review of treatment studies for ED demonstrates the important role of including a focus on interpersonal factors on treatment success [127].

Men with PE have been shown to have more interpersonal difficulties than men without PE, as well as partners of men with PE reporting higher levels of relationship problems compared with partners of men without PE [59,128,129]. Men with PE feel that they are “letting their partner down” by having PE and that the quality of their relationship would improve if they did not have PE [31].

Rosen and Althof reviewed 11 observational, noninterventional studies from 1997 to 2007 that reported on the psychosocial and quality of life consequences of PE on the man, his partner, and the relationship [130]. These studies employed different methodologies and outcome measures and consisted of both qualitative and quantitative investigations. All studies consistently confirmed a high level of personal distress reported by men with PE and their female partners. Men with PE have significantly lower scores on self-esteem and self-confidence than non-PE men, and one-third of men with PE report anxiety connected to sexual situations [131]. The negative impact on single men with PE may be greater than on men in relationships as PE serves as a barrier to seeking out and becoming involved in new relationships [132].

There is evidence of the negative impact of PE on the female partner's sexuality. This has been confirmed in several epidemiological studies where PE has been found to be correlated to overall female sexual dysfunction (FSD), sex not being pleasurable, desire, arousal, and orgasmic problems as well as low sexual satisfaction and sexual distress 128,129,131,133–139. FSD may also increase the risk of the partner having PE. For example, Dogan and Dogan [140] found that 50% of the partners of women with vaginismus were found to have PE, but it was not possible to determine whether PE was actually a consequence of the vaginismus.

Both men and their partners demonstrate negative effects and interpersonal difficulty related to their PE and an overall reduction in their quality of life. (LOE 1a–3a)

Assessment of PE

History

Patients want clinicians to inquire about their sexual health [141]. Often patients are too embarrassed, shy, and/or uncertain to initiate a discussion of their sexual complaints in the HCP's office [142]. Inquiry by the HCP into sexual health gives patients permission to discuss sexual concerns and also screens for associated health risks (e.g., cardiovascular risk and ED).

Table 3 lists recommended and optional questions that patients who complain of PE should be asked [1]. The recommended questions establish the diagnosis and direct treatment considerations, and the optional questions gather detail for implementing treatment. Finally, the committee recommends that HCPs take a medical and psychosocial history. (LOE 5d)

Table 3.

Recommended and optional questions to establish the diagnosis of PE and direct treatment

| Recommended questions for diagnosis | What is the time between penetration and ejaculation (cumming)? Can you delay ejaculation? Do you feel bothered, annoyed, and/or frustrated by your premature ejaculation? |

| Optional questions: Differentiate lifelong and acquired PE | When did you first experience premature ejaculation? Have you experienced premature ejaculation since your first sexual experience on every/almost every attempt and with every partner? |

| Optional questions: Assess erectile function | Is your erection hard enough to penetrate? Do you have difficulty in maintaining your erection until you ejaculate during intercourse? Do you ever rush intercourse to prevent loss of your erection? |

| Optional questions: Assess relationship impact | How upset is your partner with your premature ejaculation? Does your partner avoid sexual intercourse? Is your premature ejaculation affecting your overall relationship? |

| Optional question: Previous treatment | Have you received any treatment for your premature ejaculation previously? |

| Optional questions: Impact on quality of life | Do you avoid sexual intercourse because of embarrassment? Do you feel anxious, depressed, or embarrassed because of your premature ejaculation? |

PE = premature ejaculation

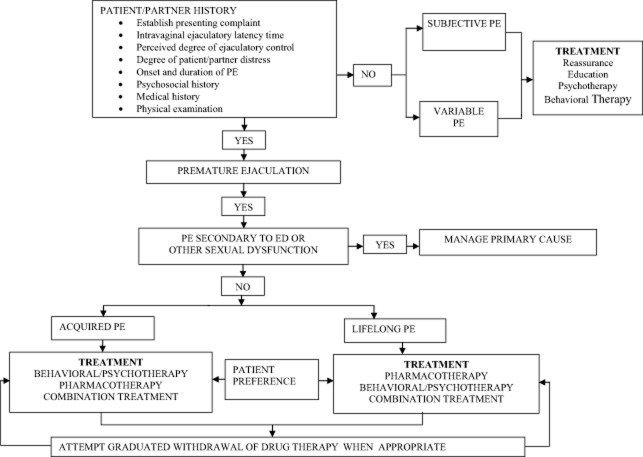

Figure 1 is a flowchart devised by Rowland et al., detailing the assessment and treatment options for subjects complaining of PE [143].

Figure 1.

Algorithm for the management of PE (with permission of D. Rowland). ED = erectile dysfunction; PE = premature ejaculation

Physical Examination

For LPE, a physical examination is advisable but not mandatory. Some patients find it reassuring for the physician to perform a hands-on physical examination. For APE, a targeted physical examination is advisable but not mandatory. The purpose of a targeted physical examination for the patient with APE is to assess for comorbidities, risk factors, and etiologies.

Stopwatch Assessment of Ejaculatory Latency (IELT)

Stopwatch measures of IELT are widely used in clinical trials and observational studies of PE, but have not been recommended for use in routine clinical management of PE [144]. Despite the potential advantage of objective measurement, stopwatch measures have the disadvantage of being intrusive and potentially disruptive of sexual pleasure or spontaneity [145]. Several studies have indicated that patient or partner self-report of ejaculatory latency correlates relatively well with objective stopwatch latency and might be useful as a proxy measure of IELT 146–148.

Because patient self-report is the determining factor in treatment seeking and satisfaction, it is recommended that self-estimation by the patient and partner of ejaculatory latency be accepted as the method for determining IELT in clinical practice. (LOE 2b)

Use of Assessment Instruments

Standardized assessment measures for PE include the use of validated questionnaires, in addition to stopwatch measures of ejaculatory latency [149]. These measures are all relatively new and were developed primarily for use as research tools. However, they may serve as valuable adjuncts for clinical screening and assessment.

Several PE questionnaires assessing lifelong and acquired subtypes have been described in the literature 150–155, although only a small number have undergone extensive psychometric testing and validation. Five validated questionnaires have been developed and published to date. Currently, there are two questionnaires that have extensive databases and meet most of the criteria for test development and validation: The Premature Ejaculation Profile (PEP) and the Index of Premature Ejaculation (IPE) [150,152]. A third brief diagnostic measure (Premature Ejaculation Diagnostic Tool [PEDT]) has also been developed, has a modest database, and is available for clinical use [154]. Two other measures (Arabic and Chinese PE questionnaires) have minimal validation or clinical trial data available [151,155]. These latter measures are not recommended for clinical use. Table 4 details these instruments in terms of number of questions, domains, and psychometric properties. The IPE, PEP, and PEDT can be found in Appendix 1.

Table 4.

Recommended patient reported outcomes for PE

| Name | Number of questions | Domain names | Reliability studies | Validity studies | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Premature Ejaculation Profile (PEP) | 4 | 1. Perceived control over ejaculation 2. Satisfaction with sexual intercourse 3. Personal distress related to ejaculation 4. Interpersonal difficulty related to ejaculation | Yes | Yes | Assesses outcome Brief, easy to administer Evaluates the subjective and clinically relevant component domains | Lack of validated cutoff scores Only one question per domain |

| Index of Premature Ejaculation (IPE) | 10 | 1. Control 2. Sexual satisfaction 3. Distress | Yes | Yes | Assesses outcome Relatively brief and easy to administer Evaluates the subjective and clinically relevant domains | Lacks norms and diagnostic cutoffs |

| Premature Ejaculation Diagnostic Tool (PEDT) | 5 | None | Yes | Yes | Screening questionnaire with cutoff scores Brief and easy to administer |

PE = premature ejaculation

Depending on the specific need, the PEP or IPE continue to be the preferred questionnaire measures for assessing lifelong or acquired subtypes of PE, particularly when monitoring responsiveness to treatment. Overall, these measures may serve as useful adjuncts but should not substitute for a detailed sexual history performed by a qualified clinician. (LOE 2b).

Psychological/Behavioral, Combined Medical and Psychological, and Educational Interventions

Psychotherapy for men and couples suffering from PE has two overlapping goals. First, psychological interventions aim to help men develop sexual skills that enable them to delay ejaculation while broadening their sexual scripts, increasing sexual self-confidence, and diminishing performance anxiety. The second goal focuses on resolving psychological and interpersonal issues that may have precipitated, maintained, or be the consequence of the PE symptom for the man, partner, or couple 156–158.

Present day psychotherapy for rapid ejaculation is an integration of psychodynamic, systems, behavioral, and cognitive approaches within a short-term psychotherapy model 7,157,159–161. Treatment may be provided in an individual, couples, or group format. Unfortunately, the majority of the psychotherapy treatment outcome studies are uncontrolled, unblinded trials; few meet the requirements for evidence-based studies [156]. Most studies employed small to moderately sized cohorts who received different varieties of psychological interventions with limited or no follow-up. Additionally, the inclusion criteria utilized by these studies varied widely and included men who would not meet the ISSM PE definition.

The most frequently used behavioral treatments are the squeeze or stop–start techniques [6,162]. Both of these therapies were designed to help men recognize mid-level ranges of excitement. Men gain skills at identifying mid-level excitement by a series of graduated exercises beginning with self-stimulation, moving on to partner-hand stimulation, then to intercourse without movement, and finally to stop/start thrusting. This process gradually leads to an increase in IELT, sexual confidence, and self-esteem; although there are few controlled studies to support this claim.

Older uncontrolled studies on the squeeze technique report a failure rate of 2.2% immediately after therapy and 2.7% at the 5-year follow-up [6]. These results have not been replicated; other studies have found success rates of between 60% and 90% [163]. De Carufel and Trudel demonstrated an eightfold increase in IELT among men treated with behavioral techniques compared with a wait-list control condition [164]. A previous study found that bibliotherapy with and without phone contact as well as sex therapy (three separate groups) experienced a sixfold increase in IELT compared with a control group [165]. Treatment gains were maintained at the 3 months follow-up.

There have been two recent meta-analytic reports and one systematic review on psychotherapy for sexual dysfunctions 166–168. The first reviewed only one PE psychotherapy article and three PE combination medical and psychotherapy studies [167]. The authors concluded that “there is weak and inconsistent evidence regarding the effectiveness of psychological interventions for the treatment of premature ejaculation.” Similarly, the second study [166] only reviewed the same report and concluded that “there was no evidence for the efficacy of psychological interventions on symptom severity in patients suffering from PE.” The third review found evidence that behavioral interventions were effective in treating PE [168]. Because these meta-analyses had such stringent inclusion criterion, the majority of the PE psychotherapy studies were not included and thus the conclusions were based on a small number of studies. The PE Guidelines Committee continues to believe that psychotherapy offers men, women, and couples benefit, including the development of sexual skills, delay of ejaculation, improving relationship concerns, and sexual self-confidence.

There is some evidence to support the efficacy of psychological and behavioral interventions in the treatment of PE (LOE 2b). Future well-designed studies on the efficacy of psychotherapy are needed.

Men with VPE (irregular and inconsistent rapid ejaculation with a diminished sense of subjective control of ejaculation) should be educated and reassured. Men with SPE (those whose IELT is within the normal range but who are preoccupied by their ejaculatory control) may require a referral for psychotherapy [10]. More research is necessary to better define the efficacy of reassurance, education, and psychotherapy with these provisional subtypes.

HCPs and mental health professionals have differing levels of interest and training in treating PE. In general, all clinicians should be able to diagnose, offer support, and prescribe behavioral exercises. When the situation is complex and/or patients are not responsive to the initial intervention, clinicians should consider referring to a sexual health specialist.

Online Treatment Programs

A recent development in the psychological treatment of male and female sexual dysfunction has been the adaptation of strategies used in face-to-face treatment to online treatment packages. McCabe et al. [169] evaluated their six-session online treatment for ED and found it to be an effective treatment for ED and a suitable alternative to face-to-face therapy. Similar findings have been obtained for Internet-based treatment for FSD [170]. Although there are currently no Internet-based programs available specifically for PE, these other programs could serve as a model for the development of such online interventions. As for other sexual disorders, this would be an extremely useful future development in the treatment of PE.

Pharmacological Treatment

Several forms of pharmacotherapy have been used in the treatment of PE [171]. These include the use of topical local anesthetics (LA) [172], selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) [57,174], tramadol [175], phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (PDE5i) [176], and alpha adrenergic blockers [177]. The use of topical LA, such as lidocaine, prilocaine, or benzocaine, alone or in association, to diminish the sensitivity of the glans penis is the oldest known pharmacological treatment for PE [60]. The introduction of the SSRIs paroxetine, sertraline, fluoxetine, citalopram, and the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) clomipramine has revolutionized the treatment of PE. These drugs block axonal reuptake of serotonin from the synaptic cleft of central serotonergic neurons by 5-HT transporters, resulting in enhanced 5-HT neurotransmission and stimulation of postsynaptic membrane 5-HT receptors.

Treatment with SSRIs and TCAs

PE can be treated with on-demand SSRIs such as dapoxetine or off-label clomipramine, paroxetine, sertraline, and fluoxetine, or with daily dosing of off-label paroxetine, clomipramine, sertraline, fluoxetine, or citalopram 63,178–187.

Dapoxetine

Dapoxetine has received approval for the treatment of PE in over 50 countries worldwide. It is a rapid-acting and short half-life SSRI with a pharmacokinetic profile supporting a role as an on-demand treatment for PE [181,182,184,188,189]. No drug–drug interactions associated with dapoxetine, including phosphodiesterase inhibitor drugs, have been reported [190]. In randomized controlled trials (RCTs), dapoxetine 30 mg or 60 mg taken 1–2 hours before intercourse is more effective than placebo from the first dose, resulting in a 2.5 and 3.0-fold increases in IELT, increased ejaculatory control, decreased distress, and increased satisfaction. Dapoxetine was comparably effective both in men with LPE and APE [114,184,191] and was similarly effective and well tolerated in men with PE and comorbid ED treated with PDE5i drugs [192]. Treatment-related side effects were uncommon, dose dependent, and included nausea, diarrhea, headache, and dizziness [184,189]. They were responsible for study discontinuation in 4% (30 mg) and 10% (60 mg) of subjects. There was no indication of an increased risk of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts and little indication of withdrawal symptoms with abrupt dapoxetine cessation [193].

There is Level 1a evidence to support the efficacy and safety of on-demand dosing of dapoxetine for the treatment of lifelong and APE. (LOE 1a)

Off-Label SSRIs and TCAs

Daily treatment with off-label paroxetine 10–40 mg, clomipramine 12.5–50 mg, sertraline 50–200 mg, fluoxetine 20–40 mg, and citalopram 20–40 mg is usually effective in delaying ejaculation 178–180,183,186,194. A meta-analysis of published data suggests that paroxetine exerts the strongest ejaculation delay, increasing IELT approximately 8.8-fold over baseline [195].

Ejaculation delay usually occurs within 5–10 days of starting treatment, but the full therapeutic effect may require 2–3 weeks of treatment and is usually sustained during long-term use [196]. Adverse effects are usually minor, start in the first week of treatment, and may gradually disappear within 2–3 weeks. They include fatigue, yawning, mild nausea, diarrhea, or perspiration. There are anecdotal reports that decreased libido and ED are less frequently seen in nondepressed PE men treated by SSRIs compared with depressed men treated with SSRIs [197]. Men wishing to impregnate their partners should be advised that SSRIs may affect the motility of spermatozoa and therefore should not begin treatment with an SSRI, or if on an SSRI, gradually discontinue taking it [198]. Neurocognitive adverse effects include significant agitation and hypomania in a small number of patients, and treatment with SSRIs should be avoided in men with a history of bipolar depression [199].

Systematic analysis of RCTs of antidepressants (SSRIs and other drug classes) in patients with depressive and/or anxiety disorders indicates a small increase in the risk of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts in youth but not adults 200–202. In contrast, such risk of suicidal ideation has not been found in trials with SSRIs in nondepressed men with PE 200–202. Caution is suggested in prescribing SSRIs to young adolescents with PE aged 18 years or less and to men with PE and a comorbid depressive disorder, particularly when associated with suicidal ideation [200]. Patients should be advised to avoid sudden cessation or rapid dose reduction of daily dosed SSRIs, which may be associated with an SSRI withdrawal syndrome [203].

On-demand administration of clomipramine, paroxetine, sertraline, and fluoxetine 3–6 hours before intercourse is modestly efficacious and well tolerated but is associated with substantially less ejaculatory delay than daily treatment in most studies [185,187,204,205]. On-demand treatment may be combined with either an initial trial of daily treatment or concomitant low-dose daily treatment [185].

Patients are often reluctant to begin off-label treatment of PE with SSRIs. Salonia et al. reported that 30% of patients refused to begin treatment (paroxetine 10 mg daily for 21 days followed by 20 mg as needed) and another 30% of those that began treatment discontinued it [206]. Similarly, Mondaini et al. reported that in a clinic population, 90% of subjects either refused to begin or discontinued dapoxetine within 12 months of beginning treatment [207]. Reasons given included not wanting to take an antidepressant, treatment effects below expectations, and cost.

There is Level 1a evidence to support the efficacy and safety of off-label daily dosing of the SSRIs paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, fluoxetine, and the serotonergic tricyclic clomipramine, and off-label on-demand dosing of clomipramine, paroxetine, and sertraline for the treatment of LPE and APE. (LOE 1a)

The decision to treat PE with either on-demand dosing of dapoxetine (where available) or daily dosing of off-label SSRIs should be based upon the treating physician's assessment of individual patient requirements. Although many men with PE who engage in sexual intercourse infrequently may prefer on-demand treatment, many men in established relationships may prefer the convenience of daily medication [208]. Well-designed preference trials will provide additional insight into the role of on-demand dosing.

In some countries, off-label prescribing may present difficulties for the physician as the regulatory authorities strongly advise against prescribing for indications in which a medication is not licensed or approved. Obviously, this complicates treatment in countries where there is no approved medication and the regulatory authorities advise against off-label prescription.

Topical Local Anesthetics

The use of topical LA such as lidocaine and/or prilocaine as a cream, gel, or spray is well established and is moderately effective in delaying ejaculation 172,173,209–211. Data suggest that diminishing the glans sensitivity may inhibit the spinal reflex arc responsible for ejaculation [212]. Dinsmore et al. reported on the use of PSD502, a lidocaine–prilocaine spray currently in clinical trials that is applied to the penis at least 5 minutes before intercourse. The treated group reported a 6.3-fold increase in IELT and associated improvements in PRO measures of control and sexual satisfaction [172]. Carson et al. reported similar results in a second Phase 3 randomized controlled trial. There were minimal reports of penile hypoanesthesia and transfer to the partner due to the unique formulation of the compound [172]. Other topical anesthetics are associated with significant penile hypoanesthesia and possible transvaginal absorption, resulting in vaginal numbness and resultant female anorgasmia unless a condom is used [210].

There is Level 1a evidence to support the efficacy and safety of off-label on-demand label topical anesthetics in the treatment of LPE. (LOE 1a)

PDE5i

PDE5i, sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil are effective treatments for ED. Several authors have reported using PDE5is alone or in combination with SSRIs as a treatment for PE 176,213–215. Although systematic reviews of multiple studies have failed to provide robust evidence to support a role for PDE5i in the treatment of PE, with the exception of men with PE and comorbid ED [216,217], recent well-designed studies do support a potential role for these agents suggesting a need for further evidence-based research [176,216].

There is some evidence to support the efficacy and safety of off-label on-demand or daily dosing of PDE5is in the treatment of LPE in men with normal erectile function (LOE 4d). Treatment of LPE with PDE5is in men with normal erectile function is not recommended, and further evidence-based research is encouraged to understand conflicting data.

Table 5 is a summary of recommended pharmacological treatments for PE.

Table 5.

Summary of recommended pharmacological treatments for premature ejaculation

| Drug | Daily dose/on demand | Dose | IELT fold increase | Side effects | Status | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Therapies | ||||||

| Dapoxetine [184] | On demand | 30–60 mg | 2.5–3 | Nausea Diarrhea Headache Dizziness | Approved in some countries | 1a |

| Paroxetine [186] | Daily dose | 10–40 mg | 8 | Fatigue Yawning Nausea Diarrhea Perspiration Decreased Sexual Desire Erectile Dysfunction | Off label | 1a |

| Clomipramine [178,180] | Daily dose | 12.5–50 mg | 6 | Off label | 1a | |

| Sertraline [183] | Daily dose | 50–200 mg | 5 | Off label | 1a | |

| Fluoxetine [194] | Daily dose | 20–40 mg | 5 | Off label | 1a | |

| Citalopram [179] | Daily dose | 20–40 mg | 2 | Off label | 1a | |

| Paroxetine [185] | Daily dose for 30 days and then on demand | 10–40 mg | 11.6 | Off label | 1a | |

| Paroxetine [185] | On demand | 10–40 mg | 1.4 | Off label | 1a | |

| Clomipramine [187] | On demand | 12.5–50 mg | 4 | Off label | 1a | |

| Topical therapy | ||||||

| Lidocaine/Prilocaine [210] | On demand | 25 mg/gm lidocaine 25 mg/gm prilocaine | 4–6.3 | Penile numbness Partner genital numbness Skin irritation Erectile dysfunction | Off label | 1a |

Other Pharmacological Treatments

Tramadol

Tramadol has been investigated as a potential off-label therapy for PE, with several studies demonstrating efficacy. The major metabolite, M1, has a 200-fold increased affinity for the μ-opioid receptor, which likely accounts for the analgesic effects achieved [218]. Because of the relatively long half-lives of tramadol (6 hours) and the M1 metabolite (9 hours), patients may be at decreased risk of developing addiction compared with other μ-opioid receptor agonists. These pharmacokinetic properties require dose adjustment in patients with hepatic or renal impairments. Although the mechanism of action is not completely described, the efficacy of tramadol may be secondary to anti-nociceptive and anesthetic-like effects, as well as via central nervous system modulation through inhibition of serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake 218–220.

Several studies have demonstrated improved IELTs with varying doses of daily or on-demand tramadol therapy. The first reported use of on demand tramadol for PE evaluated 64 patients in a blinded, randomized trial. A 50 mg dose vs. placebo was administered 2 hours prior to anticipated sexual activity over an 8-week period [219]. Results demonstrated an absolute increase in IELT from 19–21 seconds pretreatment to 243 seconds posttreatment (placebo 34 seconds, P < 0.001). Satisfaction was similarly improved with tramadol over placebo, as measured by the satisfaction domain of the International Index of Erectile Function questionnaire (14 vs. 10, P < 0.05).

Three subsequent investigations evaluated on-demand tramadol using blinded, crossover, and placebo-controlled study designs [175,221,222]. Following administration of 25–50 mg of tramadol over an 8–12-week period, patients experienced a 4–7.3-fold increase in IELT from baseline compared with a 1.7-1.8 fold increase with placebo (absolute change from 36–70 to 155–442 seconds) [175,222]. Alghobary and colleagues further investigated temporal benefits of therapy and reported slight attenuation of efficacy over time [221]. Results demonstrated a 7.2-fold increase (18 seconds pretreatment to 130 seconds) at 6 weeks of tramadol 50 mg, which decreased to 5.7-fold increase (102 seconds) at 12 weeks (P = 0.02 between time points). In comparing efficacy with paroxetine, patients receiving daily paroxetine achieved an 11.1-fold improvement (6 weeks), which further increased to 22.1-fold improvement (12 weeks). These findings suggest a need for further long-term and comparative evaluations to assess the efficacy of tramadol over time and against alternative therapies.

In the largest, blinded, placebo-controlled randomized trial performed to date, Bar-Or and colleagues evaluated the efficacy of orally disintegrating tramadol (62 mg and 89 mg) administered within 2 minutes of anticipated intercourse [223]. Results from 604 patients over 12 weeks of therapy demonstrated a clinically small, although statistically significant improvement in IELT (1.6, 2.4, and 2.5-fold increases for placebo, 62 mg and 89 mg, respectively) (P < 0.001 for all comparisons). A more recent study, evaluating 300 patients randomized to tramadol hydrochloride capsules 25, 50, or 100 mg demonstrated a dose-response effect [224]. Reported IELT increased from a mean of 174 seconds pretreatment to 790 (25 mg), 1,405 (50 mg), and 2,189 (100 mg) seconds, equating to a 4.5, 8.1, and 12.6-fold increase, respectively. Although the absolute increase in IELT was significantly elevated compared with other contemporary studies, this may be secondary to higher baseline IELTs with the study population (mean 174 seconds, standard deviation 54 seconds). See Table 6 for a summary of available studies evaluating the efficacy of tramadol on demand for the off-label treatment of PE.

Table 6.

Summary table of studies evaluating the efficacy of tramadol for the treatment of premature ejaculation

| Study | N | Design | Dosage (mg) | Duration (weeks) | Pre-tx IELT (sec) | Post-tx IELT (sec) | Mean change (sec) | Fold increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safarinejad (2006) [219] | 64 | RCT, placebo, blinded | 50 | 8 | 19 | 243 | 224 | 13 |

| Salem (2008) [222] | 60 | Crossover, placebo, blinded | 25 | 8 | 70 | 442 | 372 | 6.3 |

| Alghobary (2010) [221] | 35 | Crossover, comparison (paroxetine) | 50 | 12 | 36 | 180, 133 | 144, 97 | 7.3, 5.7 |

| Kaynar (2012) [175] | 60 | Crossover, placebo, blinded | 25 | 8 | 39 | 155 | 116 | 4 |

| Bar-Or (2012) [223] | 604 | RCT, placebo, blinded | 62, 89 | 12 | 58 | 134, 151 | 76, 93 | 2.4, 2.5 |

| Eassa (2013) [224] | 300 | Randomized, dose response | 25, 50, 100 | 24 | 174 | 790, 1,405, 2,189 | 616, 1,231, 2,015 | 4.5, 8.1, 12.6 |

RCT = randomized controlled trial; tx = treatment

Tramadol may be an effective option for the treatment of PE. However, it may be considered when other therapies have failed because of the risk of addiction and side effects. It should not be combined with an SSRI because of the risk of serotonin syndrome, a potentially fatal outcome [225]. Further well-controlled studies are required to assess the efficacy and safety of tramadol in the treatment of PE patients. (LOE2)

Oxytocin

Oxytocin has been found to shorten ejaculation latency and post-ejaculatory refractory period when it is infused into the cerebral ventricle of male rats and increases latencies of mount and intromission when administered into the intracerebroventricular space [226,227]. Similar to central administration, systemic oxytocin administration is demonstrated to shorten ejaculation latency and post-ejaculatory interval in sexually active male rats [226,227]. These findings suggested a potential role for anti-oxytocin drugs in treatment of PE. Argiolas et al. demonstrated that central administration of a selective oxytocin receptor antagonist inhibits sexual behavior, including ejaculation, in male rats [228]. Clement et al. confirmed that intraventricular administration of oxytocin antagonist dose-dependently inhibited sexual responses, whereas they also found that systemic administration of oxytocin antagonist did not make a significant change [229]. In a recent study, the same group demonstrated that a highly selective, non-peptide oxytocin antagonist (GSK557296) inhibits ejaculation when administered both peripherally and centrally [75]. The authors concluded that targeting central oxytocin receptors with a highly selective antagonist might be a promising approach for the treatment of PE.

A double-blind, placebo control study of epelsiban, a selective oxytocin receptor antagonist, failed to show either clinical or statistical differences in IELT from placebo in men with PE [230]. In an attempt to investigate the effects of polymorphisms in oxytocin and vasopressin receptor genes on ejaculatory function, Jern et al. could not detect any clear-cut gene variant revealing ejaculatory dysfunction and concluded that oxytocin receptor genes are unlikely targets for future pharmaceutical treatment of PE [92].

Intraventricular administration of oxytocin antagonist inhibits sexual behavior in animal studies; however in one human study, an oxytocin antagonist failed to clinically or statistically improve IELT. Further human studies are necessary. (LOE 4)

Cryoablation and Neuromodulation of the Dorsal Penile Nerve

Ablation and modulation of the dorsal penile nerve, which is the main afferent somatosensory pathway of the penis [231], have been suggested to be an effective treatment option for PE [232,233]. David Prologo et al. [232] reported on the unilateral computed tomography-guided percutaneous cryoablation of the dorsal penile nerve on IELT and PEP outcomes in 24 men with PE. Baseline average IELT significantly increased (from 54.7 ± 7.8 to 140.9 ± 83.6 at the end of the first year, P < 0.001) and PEP results were also improved. The authors noted that the majority of the subjects said that they would undergo the procedure again.

In another study, Basal et al. [233] investigated the clinical utility of percutaneous pulsed radiofrequency ablation of bilateral dorsal penile nerves in 15 patients with LPE. The authors described a significant increase in the mean IELT 3 weeks after the procedure (18.5 ± 17.9 vs. 139.9 ± 55.1 seconds) and PRO measures improved. However, further expanded clinical trials are necessary before such modalities can be recommended for treating PE.

Neuromodulation of the dorsal penile nerve is an invasive and irreversible procedure, which is associated with an increase in the IELT. However, safety of this treatment modality needs to be determined before this procedure can be recommended for treating PE patients. (LOE 4)

Intracavernosal Injection for PE

There is limited evidence regarding the efficacy of intracavernosal vasoactive drug injection for the treatment of PE. In one study, which included eight PE patients, a mixture of phentolamine mesylate (1.0 mg/mL) and papaverine hydrochloride (30 mg/mL) was injected. All patients reported satisfaction with the results of this treatment, but ejaculation delay was not objectively measured [234].

Intracavernosal injection of vasoactive drugs is not recommended for the treatment of PE. (LOE 4)

Acupuncture

One randomized placebo-controlled clinical study compared effectiveness of acupuncture therapy (twice a week) with paroxetine (20 mg/day) and placebo (sham acupuncture) in the treatment of PE [235]. The authors included 90 patients with PE and demonstrated that acupuncture had a significantly stronger ejaculation delaying effect than placebo (65.7 vs. 33.1 seconds), although it was less effective than daily paroxetine (82.7 seconds) (P = 0.001). Similarly, the PRO measures showed an improvement in the acupuncture and paroxetine groups.

There are limited positive data regarding the effectiveness of acupuncture therapy. (LOE 3b)

Preclinical Studies for PE

Several agents have been studied in animal models for treating PE. A potent SSRI (DA-8031) significantly inhibited ejaculation after oral and intravenous administration in both para-chloroamphetamine and meta-chlorophenylpiperazine-mediated ejaculation rat models [236]. In another study using a rat model, DA-8031 administration resulted in inhibition of the expulsion phase of ejaculation by bulbospongiosus muscle activity modulation and impairment of the emission phase by blocking the seminal vesicular pressure rise [237].

Modafinil (diphenylmethyl sulphinyl-2-acetamide) is an agent that is used for the treatment of narcolepsy. In a behavioral rat model, Marson et al. [238] demonstrated that modafinil (30 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg) produced a significant delay in ejaculation. The delay in ejaculation was accompanied by an increase in the number of intromissions without any change in the mount or intromission latency.

Because the bulbospongiosus muscle plays a pivotal role in the expulsion phase of ejaculation, decreasing its contractile activity with injection of botulinum toxin may be of benefit in treating PE [239]. In an animal model Serefoglu et al. [240] demonstrated that botulinum toxin A injection (0.5–1 U/mL) into the bulbospongiosus muscle bilaterally significantly increased ejaculatory latency in male rats.

Combining Psychological and Pharmacological Treatment

Combining medical and psychological interventions harnesses the power of both therapies to provide patients with rapid symptom amelioration, while the psychological and interpersonal issues that either precipitated or maintained the symptom are addressed [143,157,241,242]. There are three studies reporting on combined pharmacological and behavioral treatment for PE 243–245 and one study reporting on consecutive treatment with pharmacotherapy followed by behavior therapy [246]. Each study used a different medication—sildenafil, citalopram, clomipramine, or paroxetine (in the consecutive study). Pharmacotherapy was given in conjunction with a behavioral treatment and compared with pharmacotherapy alone. In all three studies, combination therapy was superior to pharmacotherapy alone on either IELT and/or the Chinese IPE.

For ED, combined treatments have also been found to be more effective than either medical or psychological treatments alone [167,247,248]. Factors that are not addressable by pharmacotherapy alone can be attended to such as: (i) patient factors (performance anxiety, self-confidence); (ii) partner factors (partner sexual dysfunction); (iii) relationship factors (conflict, lack of communication); (iv) sexual factors in the relationship (sexual scripts, sexual satisfaction); and (v) contextual factors (life stressors).

Combining a medical and psychological approach may be especially useful in men with APE where there is a clear psychosocial precipitant or lifelong cases where the individual or couple's issues interfere in the medical treatment and success of therapy. Similarly, in men with PE and comorbid ED, combination therapy may also be helpful to manage the psychosocial aspects of these sexual dysfunctions. (LOE 2a)

Role of Education and Coaching

Education (or coaching) on PE may be useful to attend to aspects of PE that are not treated with medication [157,241,242,249]. Providing education on the prevalence of PE and general population IELT may help to dispel myths. Additionally, education may help men with PE to not avoid sexual activity, to discuss issues with their partner, or limit their sexual repertoire.

Educational or coaching strategies are designed to give the man the confidence to try the medical intervention, reduce performance anxiety, and modify his maladaptive sexual scripts. (LOE 5d)

Lifelong PE

As LPE is likely to have an organic etiology, a medical intervention with basic psycho-education is initially recommended [10,250].

If the PE has resulted in psychological and relationship concerns, graded levels of patient and couple counseling, guidance, and/or relationship therapy may be a useful adjunct to the medical intervention. (LOE 1a)

Acquired PE

It is recommended that HCPs utilize a combination medical and psychological approach where feasible [251]. Men desire an immediate effect from therapy; therefore pharmacotherapy and amelioration of associated disease factors such as ED will be extremely helpful.

Education on the nature of PE, helping men improve ejaculatory control with behavioral exercises, addressing restricted/narrow sexual behavioral patterns, and resolving interpersonal issues are likely to be of significant help to men with APE. Once the man's self confidence and sense of control have improved, it may then be possible to reduce or discontinue the medical intervention. (LOE 5d)

Role of the Primary Care Clinician

Primary care providers are usually the first line of contact for a patient with the health care system, including for the diagnosis and management of sexual problems. This role includes (i) initial recognition and evaluation of any undiagnosed sign, symptom, or health concern (the “undifferentiated” patient); (ii) health promotion including disease prevention, health maintenance, counseling, patient education, chronic illness management, and patient advocacy; and (iii) coordination of care promoting effective communication with patients and encouraging the patient to be a partner in health [252]. This model of care is not limited by problem origin, organ system, or diagnosis.

Primary care providers (PCP) are the ideal group to assist the patient with sexual difficulties for several reasons including: (i) the value of the longitudinal and personal relationships with patients; (ii) the multifactorial issues around sexual problems that can be appropriately evaluated by a generalist clinician; and (iii) the long-term follow-up routine in primary care is well suited to being certain that a sexual dysfunction is resolved. The main responsibility of the PCP is to recognize PE and enable the patient to feel comfortable about getting help, either in the primary care setting or through an effective referral. PCPs can normalize and universalize the inquiry about sexual concerns and then use screening questions to identify PE. PCPs who have effective communication skills regarding sexual function and who are knowledgeable about first-line treatments can initiate the workup and treatment plan.