Abstract

Introduction

Pharmacists play a key role while dispensing over-the-counter emergency contraception (EC) to the client.

Aims

The study aims to evaluate the knowledge and over-the-counter services provided by the pharmacists in Delhi.

Methods

A prestructured questionnaire-based survey was conducted in Delhi, the capital city of India.

Results

Only 60 out of 85 pharmacies approached agreed to participate in the study. Number of packs sold in a month per pharmacy varied from 2 to 500 packs/month. Sixty-two percent of the pharmacists claimed that majority of the clients repeated use during the same month. Only 18% of the clients were referred by doctors while 82% directly approached the pharmacists. Nearly one third of the clients were adolescents. Sixty-seven percent of the pharmacists had adequate knowledge about EC. Only 3.3% asked about the last menstrual period or the time elapsed since the last unprotected intercourse. No pharmacist inquired whether there were one or multiple unprotected acts of intercourse, if any regular contraceptive method was being used, or explored the reason for EC intake. There were 91.7% who explained the dosage schedule to clients. Only half of them explained that the client may experience side effects. None of the pharmacists advised their clients for a sexually transmitted disease screening, and 35% counseled the clients regarding regular contraception.

Conclusion

Improving the quality of services provided by the pharmacists can clear misconceptions of the clients and promote subsequent regular contraception along with precautions to avoid sexually transmitted diseases. Mishra A and Saxena P. Over-the-counter sale of emergency contraception: A survey of pharmacists in Delhi. Sex Med 2013;1:16–20.

Keywords: Pharmacists, Emergency Contraception, Over the Counter

Introduction

Emergency contraception (EC) is defined as the use of contraceptive method after intercourse to prevent unintended pregnancy, and it is indicated in situations like sexual assault, incest, failure of barrier contraceptive, or after an unprotected intercourse.

The Drug Controller General of India approved levonorgestrel, a progestin-only pill, as the dedicated product for EC in 2001. It was included in a national family planning program in 2003. EC was made available over the counter in 2005 but its popularity increased in urban young women after 2007 due to mass advertising efforts of manufacturer companies.

Over-the-counter availability of EC was an important step taken by the Government of India to popularize its use in the country in order to reduce the rate of unwanted pregnancies which would bring down the rate of abortions and associated maternal morbidity and mortality. ECs taken within 72 hours of an unprotected intercourse are 75–85% effective [1]. At present there are seven EC pills available in the Indian market, all of them are sold over the counter. Their cost is about 1.84 USD per pack.

According to service delivery guidelines of Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, emergency contraceptive pills can be dispensed by doctors, nurses, midwives, pharmacists, paramedics, family welfare assistants, and other clinically trained personnel as well as community health workers in order to improve their widespread use. However, all providers should be appropriately informed about EC and should also counsel the clients for regular contraceptive usage [2].

The sale of EC has increased manifold. Most clients prefer to obtain EC through drugstores rather than medical facilities, although EC is available free of cost in public sector [3,4]. No previous published study has assessed the knowledge and practices of pharmacists for dispensing EC in India. Therefore, we conducted this study to evaluate the knowledge and over-the-counter services provided by the pharmacists in an urban city of India.

Methods

This was a prestructured questionnaire-based survey conducted in Delhi, the capital city of India. A total of 85 pharmacies situated in nine districts of Delhi were approached by a team of doctors. Only 60 out of 85 pharmacies approached agreed to participate in the study after ensuring confidentiality. Of the 25 pharmacies who refused to participate in the study, all were privately owned in urban or semi-urban areas. Six pharmacists informed that they did not dispense emergency contraceptives or any abortifacient on moral grounds; three pharmacies were small and supplied limited medications. Two pharmacies refused to participate in the study although they dispensed EC because they were not sure whether over-the-counter sale of EC was legally permitted and viewed the investigators with suspicion even after reassurance. Fourteen busy pharmacists refused to participate as they were placed near big hospitals and could not spare any time for this interview.

A team of five female doctors were trained to conduct the interview. The questionnaire was pretested before initiating the study. Any one of these five conducted the interview. A written questionnaire in both English and Hindi (local language) was handed over to the pharmacists for filling after explaining the purpose of the study, but the surveyors were always available to explain if there was any query in the mind of the pharmacists.

The prestructured proforma consisted of 14 questions along with an extra column for any special remark or any additional information provided by the pharmacists (see Appendix). Filled proforma were collected on the spot and no incentive money was paid. As this study did not involve patients, approval from ethical committee was not obtained.

During interview, knowledge of pharmacist was judged. It was considered to be adequate if they knew about the EC constituents, indications of use, mode of action, dosage schedule, time duration during which it could be taken, side effects, may lead to failure, should be used only for emergency purposes, and cannot be used as a regular contraception. If any of these was lacking, the knowledge of the pharmacist was considered inadequate.

Results

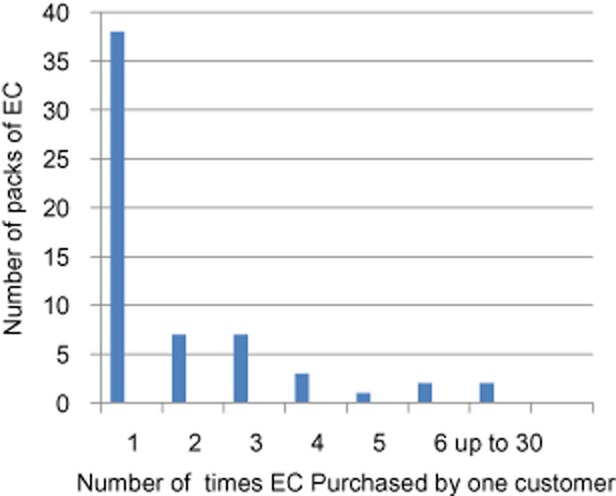

Response rate of participating pharmacists was 70.6%, i.e., 60 out of 85 approached agreed to participate in the study. Number of packs sold in a month per pharmacy varied from 2 to 500 packs/month, with a mean of 62 packs every month. Thirty-eight pharmacists claimed that clients took the EC once every month while the rest (62%) claimed that majority of the clients repeated use during the same month. Two pharmacists reported that the same clients bought pack of EC as high as even 30 times a month (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Maximum frequency of use of emergency contraception (EC) per month per customer.

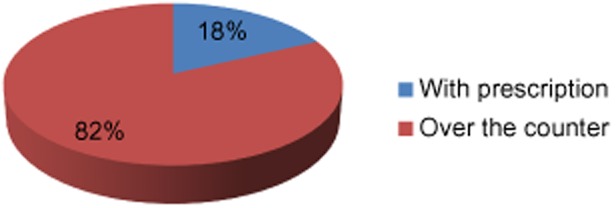

Levonorgestrel 1.5 mg single dose within 72 hours is the most preferred regimen. Eighteen percent of the clients were referred by doctors while 82% directly approached the pharmacists (Figure 2). There was a nearly equal clientele of both sexes, with 47% females and 53% males approaching the pharmacy.

Figure 2.

Mode of purchase of emergency contraception.

Nearly one third of the clients were adolescents. The duration of the interaction between the pharmacist and the client ranged from 2 to 10 minutes, with an average of 5 minutes. Sixty-seven percent (40/60) of the pharmacists had adequate knowledge about EC. According to most pharmacists, they could communicate more freely with male customers as compared with female customers because they did not want to embarrass or lose the latter.

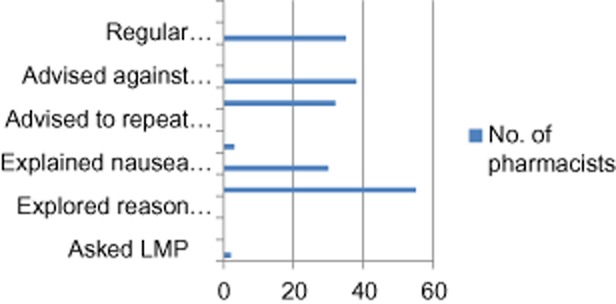

Information regarding discussion of pharmacists with clients is shown in Figure 3. Only two pharmacists (3.33%) asked about the last menstrual period or the time elapsed since the last unprotected intercourse. No pharmacist inquired whether there were one or multiple unprotected acts of intercourse. None of them asked if any regular contraceptive method was being used or explored the reason for EC intake like bursting of condom or oral contraceptive missing.

Figure 3.

Discussion while dispensing emergency contraception. LMP = last menstrual period.

While dispensing of the EC, 55/60 (91.7%) explained the dosage schedule to clients. Thirty (50%) explained that the client may experience nausea or vomiting. Three (5%) advised the clients to take EC with antacids or anti-emetics. None of them advised the client to repeat the dose of EC in case of vomiting within 2 hours of intake.

Thirty-two (53.3%) explained that the client may conceive in spite of consuming the medicine. Thirty-eight (63.3%) explained that repeat intake of ECs is harmful to the client. None of the pharmacists advised their clients for a sexually transmitted disease (STD) screening. Only 35% (21/60) counseled the clients regarding regular contraception. Five percent (3/60) advised regarding condoms while 30% (18/60) advised regarding both condom and oral contraceptives. According to all pharmacists, no patient reported back to them with failure of contraception.

Discussion

In 1960, the first clinical trials of hormone emergency contraceptive were conducted using high-dose estrogen hormone. In 1970, Yuzpe method was initiated using high-dose combined oral contraceptive containing ethinyl estradiol, and levonorgestrel. Nowadays available options of emergency contraceptive methods are Levonorgestrel (0.75 mg, 2 tabs 12 hours apart or 1.5 mg single dose), danazol, mifeprestone, and intrauterine contraceptive device. Mechanism of action of EC depends on the phase of menstrual cycle. Suggested mechanisms of action are inhibition of or delayed ovulation, prevention of implantation, fertilization or dysynchrony in transport of the sperms or ovum. Levonorgestrel-containing preparations are found to exhibit fewer side effects with identical efficacy to Yuzpe method and are the dedicated EC in India [5].

Concerns that easy access to EC may lead to careless sexual behavior have been dispelled [5]. A number of studies have now demonstrated that facilitating access neither reduces compliance with contraceptive use nor increases rates of unprotected sexual intercourse or sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [3,6,7]. However, no study has demonstrated that increased availability of EC reduces unintended pregnancy rates. At a population level, it is becoming apparent that improved access to EC has no significant impact on abortion rates [7–9].

A recent study on the impact of increased access to EC concluded that, ultimately, the greatest health benefit of EC may be achieved indirectly by health workers counseling women at the time they present for procuring EC to improve use of their current method or to change to a more reliable method [9,10].

Pharmacists play a key role in providing emergency contraception services and it is essential that they have comprehensive and correct knowledge about the methods available. Only 67% (40/60) of the pharmacists had adequate knowledge about EC. They can carry out the role of supplying EC with good counseling only if they have correct knowledge, which would reduce maternal mortality and morbidity due to unwanted pregnancies.

Most of the pharmacists interviewed in this study did not have a separate private area to conduct counseling for the clients although nearly two thirds (67%) had adequate knowledge about ECs. Fifty-five out of sixty pharmacists (91.7%) were clear about the differences between EC and medical abortions, which is a method for inducing early abortion by means of drugs. Still, only two of them inquired about the last menstrual cycle or the time elapsed since coitus and dispensed EC without ruling out pregnancy.

The reasons for not providing adequate counseling to the clients were lack of privacy during conversation, lack of time or knowledge, to avoid embarrassment to the clients, or to avoid the risk of losing the customer in the future.

Over-the-counter availability has increased use of EC due to avoidance of embarrassment and easy accessibility round the clock, but full potential of pharmacists has not been utilized. Another important fact is that hardly any clients are approaching public sector facilities for procuring EC even though it is supplied free of cost. Other advantages of obtaining EC from medical facilities would be correct information regarding use of EC along with advice regarding regular contraception, STD screening, and future protection from infection transmission.

Most of the pharmacists are not encouraging their clients to use regular contraception. They are also not advising them regarding protection from STIs by use of condoms. It is alarming that EC is being used more frequently as means of avoiding pregnancies rather than using regular family planning methods. Low efficacy and significantly higher side effects of EC as compared with regular contraception need to be emphasized by the pharmacists to avoid repeat usage by the clients.

The limitations of this study are that the results are based on the self-report by a pharmacist which implies that the practices in this study may be a proxy for actual practices while dispensing EC. Also, the results of this study cannot be generalized to all pharmacists in India.

Pharmacists should not miss any opportunity to guide and educate their clients as they are sometimes the first or only contact of client to a health professional. At the same time, it is to be remembered that unlike medical facilities, pharmacies are profit-making, private-owned places where they desire more frequent, speedy, confidential, and costly transactions (EC is more costly than oral contraceptive pills). Therefore the interest of both pharmacist and clients have to be balanced and protected.

Certain steps to improve pharmacy services could be inclusion of EC-related knowledge and services in their curriculum in order to impart correct knowledge and sensitize them for appropriate counseling for subsequent sexual behavior. Short-term refresher training can also be introduced. Close links should be developed between clinicians and pharmacists for smooth exchange of referrals. Leaflets containing correct information regarding emergency contraceptive and promotion of regular contraception can be provided to the customers along with emergency contraceptive pills. Mass media should help in behavior-changing communication and understanding need of regular contraception.

Appendix

Prestructured Questionnaire for Pharmacists

Name of the Chemist Address:

How many packs of EC are sold in 1 month?

How many clients come with prescription?

What is the gender of the clients?

What percentage of clients are adolescents?

-

Knowledge of pharmacists:

What are the constituents of EC pill?

What is the indication of use of EC pill?

What is the mode of action of EC pill?

Time limit for EC intake after unprotected act of intercourse

Dosage schedule

Side effect of EC

Can a woman conceive in spite of taking EC?

Should EC be used for emergency/regular contraception?

Do you understand the difference between emergency contraception and medical abortion?

Do clients come for buying EC more than once a month?

Maximum number of times clients come for buying EC/month

Which is the most preferred regimen of EC?

Time spent during interaction between the client and the pharmacist

-

Do you inquire the client about the following while dispensing EC?

Last menstrual period

Time elapsed since last unprotected act of intercourse

Single or multiple acts of unprotected intercourse

Whether there have been other acts of unprotected intercourse 72 hours prior to intake of EC

Whether client was using regular contraception

-

While dispensing EC do you counsel the client regarding:

Dosage Schedule?—Yes/No

Expected side effects like nausea and vomiting?—Yes/No

Taking EC along with antacid/anti-emetics?—Yes/No

Repeating EC in case of vomiting within 2 hours?—Yes/No

That frequent intake of EC may be harmful?—Yes/No

STD screening by a medical practitioner?—Yes/No

Advice to use regular contraception in future?—Yes/No. If yes, which one?

That client may conceive in spite of consuming EC?

Does any patient report to you if they conceive even after EC intake?

Reasons for not providing adequate counseling to the clients

Conflict of Interest

No financial support was provided for the study from any external source and the authors have no interest in the findings of the study.

References

- 1.Kubba AA. Hormonal postcoital contraception. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 1997;2:101–104. doi: 10.3109/13625189709167462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. 2008. Guidelines for Administration of Emergency Contraceptive Pills by Health Care Providers. Available at: http://www.nrhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/family-planing/guidelines/Guidelines%20for%20administration%20of%20Emergency%20Contraceptive%20Pills%20(ECP)%20by%20health%20care%20providers.pdf (accessed January 9, 2012)

- 3.Marston C, Meltzer H, Majeed A. Impact on contraceptive practice of making emergency hormonal contraception available over the counter in Great Britain: Repeated cross-sectional surveys. BMJ. 2005;331:271. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38519.440266.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wynn LL, Erdman JN, Foster AM, Trussell J. Harm reduction or women's rights? Debating access to emergency contraceptive pills in Canada and the United States. Stud Fam Plann. 2007;28:253–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2007.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Lancet. 1998;352:428–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raine T, Harper C, Rocca C, Fischer R, Padian N, Klausner J, Darney P. Direct access to emergency contraception through pharmacies and effect on unintended pregnancies and STIs: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:54–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreau C, Bajos N, Trussell J. The impact of pharmacy access to emergency contraceptive pills in France. Contraception. 2006;73:602–608. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polis CB, Schaffer K, Blanchard K, Glasier A, Harper CC, Grimes DA. Advance provision of emergency contraception for pregnancy prevention (full review). Cochrane Fertility Regulation Group. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005497.pub2. CD005497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raymond EG, Trussell J, Polis C. Population effect of increased access to emergency contraceptive pills: A systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:181–188. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000250904.06923.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black KI, Mercer CH. Provision of emergency contraception: A pilot study comparing access through pharmacies and clinical settings. Contraception. 2008;77:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]