Abstract

Object

To compare loss of neurons in the nucleus basalis of Meynert (NB) in subcortical ischemic vascular disease (SIVD) to normal controls, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and cases with mixed AD/SIVD pathology.

Design

Autopsied cases drawn from a longitudinal observational study with SIVD, AD and normal aging.

Subjects

Pathologically defined SIVD (n = 16), AD (n = 20), mixed pathology (n = 10), and age- and education-matched normal control (n = 17) groups were studied.

Main Outcome measures

NB neuronal cell counts in each group and their correlation with the extent of MRI white matter lesions (WML) and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scores closest to death.

Results

No significant loss of neurons was found in SIVD compared to age-matched controls in contrast to AD and mixed groups, where there was significant neuronal loss. A significant inverse correlation between NB neurons and CDR scores was found in AD, but not in the SIVD and mixed groups. NB cell counts were not correlated with either the extent of white matter lesions or cortical gray matter volume in SIVD or AD groups.

Conclusions

These findings inveigh against primary loss of cholinergic neurons in SIVD, but do not rule out the possibility of secondary cholinergic deficits due to disruptions of cholinergic projections to cerebral cortex.

Several randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials have shown beneficial effects of acetyl choline esterase inhibitors (AChEIs) in subjects with vascular dementia (VaD)1–4. However, cognitive impairment of vascular origin is highly heterogeneous and the mechanisms underlying the positive effects of AchEIs are not clear. Possible explanations include inclusion of mixed cases of Alzheimer disease (AD) and VaD, disruption of cholinergic projection pathways by ischemic white matter lesions, or primary degeneration in the nucleus basalis (NB) of Meynert. Among the four cholinergic neuron groups in the forebrain, neurons of NB of Meynert (also known as Ch4) project to the cerebral cortex5 through the medial and lateral cholinergic pathways6. It is well known that neurons of NB degenerate and their cholinergic transmissions are interrupted in AD7–9. However, whether there is loss of cholinergic neurons in pure VaD remains unclear.

Subcortical VaD is a subtype of vascular cognitive impairment attributed to ischemic brain injury (e.g., infarcts and white matter changes)10. Subcortical ischemic vascular disease (SIVD) refers to evidence of infarction in subcortical regions based on MRI or neuropathologic findings without reference to cognitive status. We hypothesized that white matter lesions can produce retrograde degeneration of NB neurons. In this study, we assessed NB neurons in autopsied subjects enrolled in a longitudinal, prospective, multi-center Ischemic Vascular Dementia program project (IVD project, PO1-AG12435). We compared numbers of neurons in pathologically-defined SIVD with age- and education-matched normal controls, AD, and mixed AD/SIVD. We also correlated NB neuronal loss with the extent of white matter lesions (WML) measured on MRI and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scores11.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were recruited to participate in a large multi-center longitudinal study to examine relative contributions of SIVD and AD to cognitive impairment12. Subjects with SIVD, AD, mixed SIVD/AD and cognitively normal elderly subjects were enrolled. Cognitively impaired or demented subjects were recruited mainly from university-affiliated memory clinics, whereas normal subjects were recruited from the community. Samples reported here comprise 191 autopsy cases (included in the December 2010, neuropathology data base), drawn from a total of 738 cases, of whom 278 were deceased (autopsy rate 68.7%). The research project was reviewed and approved by appropriate institutional review boards and written informed consent was obtained from the study participants or their legal representatives.

Inclusion criteria at the time of enrollment included age older than 55 years, English speaking, cognitively normal or impaired (CDR≤2) due to either SIVD or AD. SIVD was defined clinically by the presence in proton density MRI of discrete gray matter hyperintensities > 2 mm in diameter, which were operationally defined as lacunes. Exclusion criteria included severe dementia (CDR > 2), history of alcohol or substance abuse, a history of head trauma with loss of consciousness longer than 15 minutes, severe medical illness, neurologic or psychiatric disorders except dementia, or currently taking medications likely to affect cognitive function. Subjects with evidence of cortical infarcts, hemorrhage, or structural brain disease other than atrophy, lacunes, or white matter lesions were excluded.

Comprehensive clinical information including medical history, physical and neurological evaluation, Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE)13, and laboratory findings were collected from all participants. Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) genotype was also obtained by using a polymerase chain reaction-based assay. Serial neuropsychological tests and quantitative MRI measures were obtained in this prospective longitudinal study. Although the clinical diagnosis of probable or possible AD or IVD was made based on published criteria14, 15, pathological diagnoses were used to define comparison groups in this study12.

Neuopsychologic Evaluation

All subjects received a standardized battery of neuropsychologic tests within 6 months of the MRI. Besides MMSE and CDR for standard clinical assessments of global cognitive function, four composite domain-specific composite scores were calculated. They included global cognition (GLOBSC), verbal memory (MEMSC), non-verbal memory (NVMEMSC) and executive function (EXECSC). The procedures and validation of these scores have been previously described 16, 17. The composite scores were calculated and transformed to a measurement scale with a mean of 100 and standard deviation of 15.

Neuropathologic processing, diagnosis, and quantitative analysis

At the time of autopsy, brains were weighed and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for at least 2 weeks. Each cerebral hemisphere was sectioned coronally at 5 mm thickness using a rotary slicer and examined for macroscopic lesions. All macroscopic infarcts were measured, photographed, and blocked for microscopic examination. Tissue was obtained from standardized regions in 1 hemisphere according to a standardized protocol12. The standard protocol includes sections from both anterior and posterior white matter in addition to combined sections recommended by AD and dementia of Lewy body (DLB) consortium groups18–20. Each case was reviewed at a consensus neuropathology conference, which included two neuropathologists who were blinded to the clinical information.

The severity of cerebrovascular ischemic injury was rated using a cerebrovascular parenchymal pathology score (CVDPS) as previously described12. Subscores for cystic infarcts, lacunar infarcts, and microinfarcts were created by summing the individual scores across all brain regions and normalizing to a scale of 0 to 100. The three subscores were then summed to give a total CVDPS score (0–300). Acute strokes near the time of death were noted, but were not included in the CVDPS score. For neurodegenerative lesions, Braak & Braak (BB) stage21, CERAD plaque19, and McKeith Lewy body18 scores were recorded.

Pathologic Diagnosis

To define and categorize subgroups pathologically, cutoff scores were chosen for CVDPS and BB stage. We used a CVDPS score ≥ 20 as the cutoff score for cerebrovascular disease and BB stage ≥ IV to indicate AD as described in our previous publications12, 17, 22. Subjects with CVDPS ≥ 20 and BB stage < IV were classified as SIVD, BB stage ≥ IV and CVDPS < 20 as AD, and BB stage ≥ IV and CVDPS ≥ 20 as mixed AD/SIVD groups. Subjects with intact cognition (CDR = 0) without significant AD or CVDPS pathology were classified as normal controls.

Counts of neurons of NB

Serial 15μm thick sections containing NB tissue were stained with cresyl violet and reviewed at a low magnification field as described in our previous publication23. One slide from each case was chosen for counting. The total number of magnocellular NB neurons was counted in Ch4 region containing the site of maximum neuronal density24, 25. In addition, nucleolated neurons were identified and counted under 200X magnification. Each section was counted three times. Although NB was only available from 1 hemisphere, it is bilaterally symmetric in healthy controls and AD25. Counts were averaged over the three trials and were expressed as the total number of neurons or the number of nucleolated neurons per section.

MRI acquisition and processing methods

Acquisition and segmentation methods for MRI data have been described in previous publications26–29. MRI variables of interest were computerized measures of volumes of white matter lesions (WML) and cortical gray matter (CGM). WML volumes were assessed based on semi-automated segmentation using T1-, T2-weighted and proton density images. WML was defined as hyper-intense regions on proton density and T2-weighted MR images and anatomically located in white matter regions. All volumes were expressed as percentage of total intracranial volume (ICV).

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to (a) compare continuous variables of the demographic characteristics (age, years of education, and duration of illness), (b) total and nucleolated NB neuron counts, (c) the MMSE and four composite domain-specific composite cognitive scores among the 4 pathologic diagnosis groups (SIVD, AD, mixed, and control group). Fisher’s exact test was applied for categorical variables (gender distribution, race, presence of stroke risk factors, ApoE allele). MRI measures were corrected for ICV and expressed as %ICV. Spearman correlation coefficients were used to examine the associations between NB neuron count and MRI measures, and the correlations between neuron cell counts and global cognitive function (CDR scores closet to death). Analyses were 2-tailed with significance set at p<0.05 and were carried out with the SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Sample Characteristics

The number of autopsied cases (n = 191) comprised 19 cases with SIVD, 81 cases with AD, 16 cases mixed AD/SIVD pathology, 44 cases with normal or minimal pathology (18 CDR = 0, 26 CDR ≥ 0.5), 11 DLB, 2 fronto-temporal dementia, 2 progressive supranuclear palsy, and 15 cases pending consensus diagnosis. For this study, we selected 16 cases with SIVD with complete neuropsychological, MRI, and NB sections. We then selected comparison groups matched on age and education: 20 with AD, 10 with mixed AD/SIVD, and 17 normal controls (CDR = 0). The groups did not significantly differ on duration of illness, sex, or race (Table 1). Whereas a history of stroke was more frequent among SIVD subjects (p = 0.02), the presence of an ApoE4 allele was more frequent in the AD and mixed groups (p = 0.03).

Table 1.

Demographic Data by Pathologic Diagnosis1 (N = 63)

| Control (n = 17) | SIVD (n = 16) | AD (n = 20) | Mixed AD/SIVD (n = 10) | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at death (SD), yr | 84.0 (6.6) | 82.2 (7.5) | 85.6 (5.9) | 83.1 (7.0) | 0.50 |

| Mean education (SD), yr | 14.6 (2.9) | 14.3 (2.8) | 14.7 (2.9) | 14.1 (3.4) | 0.95 |

| Mean duration of illness (SD), yr | N/A | 6.7 (8.1) | 7.9 (4.0) | 8.1 (3.5) | 0.78 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.39 | ||||

| Male | 6 (35.3) | 10 (62.5) | 12(60.0) | 5 (50.0) | |

| Female | 11 (64.7) | 6 (37.5) | 8 (40.0) | 5 (50.0) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.06 | ||||

| White | 13 (76.5) | 12 (75.0) | 20 (100.0) | 8 (80.0) | |

| Non-white | 4 (23.5) | 4 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (20.0) | |

| Presence of risk factors, n (%) | |||||

| Hypertension | 4 (23.5) | 8 (53.3) | 9 (45.0) | 6 (60.0) | 0.25 |

| Heart disease | 2 (11.8) | 6 (40.0) | 6 (31.6) | 2 (22.2) | 0.37 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 4 (23.5) | 4 (28.6) | 2 (10.5) | 5 (55.6) | 0.09 |

| Diabetes | 3 (17.6) | 5 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0.037** |

| Stroke | 1 (5.9) | 8 (53.3) | 3 (16.7) | 2 (20.0) | 0.020** |

| TIA | 2 (11.8) | 4 (26.7) | 3 (15.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0.76 |

| Smoking | 8 (57.1) | 8 (61.5) | 8 (53.5) | 5 (55.6) | 0.93 |

| ApoE4 allele | 3 (18.8) | 3 (18.8) | 10 (58.8) | 4 (50.0) | 0.033** |

SIVD, Subcortical Ischemic vascular disease; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; TIA, transient ischemic attack, ApoE4, apolipoprotein E4; N/A, not applicable.

Subjects with CVDPS ≥ 20 and BB stage < IV were classified as SIVD; BB stage ≥ IV and CVDPS < 20 as AD; and BB stage ≥ IV and CVDPS ≥ 20 as mixed AD/SIVD. Subjects with CDR = 0 and without significant AD or CVDPS pathology were classified as a normal control group.

Data are presented as mean (SD) with group comparison by ANOVA for continuous variables; data are presented as number (%) with group comparison by Fisher’s Exact test for categorical variables.

p < 0.05

Cognitive function by pathologic diagnosis

Table 2 shows the mean cognitive scores by pathological group for all 63 subjects. The MMSE and all cognitive summary scores (global cognition, verbal memory, executive function, and non-verbal memory) all differed significantly among the groups (all p < 0.0001, ANOVA). Mean scores of all cognitive variables were the highest in the control group and the lowest in the mixed group.

Table 2.

Distribution of Cognitive Functions at Last Clinic Visit by Pathologic Diagnosis

| Control (n = 17) | SIVD (n = 16) | AD (n = 20) | Mixed AD/SIVD (n = 10) | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE | 24.14 (1.03) | 22.88 (8.51) | 17.05 (8.76) | 14.40 (6.64) | < 0.0001 |

| GLOBSC | 108.16 (10.01) | 82.92 (26.76) | 63.43 (27.93) | 51.87 (17.75) | < 0.0001 |

| MEMSC | 106.37 (18.94) | 81.91 (27.30) | 60.85 (19.34) | 56.62 (9.65) | < 0.0001 |

| EXECSC | 103.79 (10.64) | 75.71 (27.29) | 73.52 (24.47) | 61.51 (18.32) | < 0.0001 |

| NVMEMSC | 103.03 (13.39) | 74.74 (22.21) | 60.23 (14.59) | 49.91 (12.50) | < 0.0001 |

SIVD means subcortical ischemic vascular disease; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; GLOBSC, global summary score; MEMSC, verbal memory summary score; EXECSC, executive function summary score; NVMEMSC, non-verbal memory summary score.

Data are presented as mean (SD) with group comparison by ANOVA.

Pathological characteristics of the SIVD group

Table 3 summarizes the BB stages and CVDPS scores for the SIVD cases and details the location of the infarcts. All had infarcts in the basal ganglia, thalamus, or subcortical white matter. However, many of them had cystic and microinfarcts in the cerebral cortex as well. Two cases (#1 and #14) had large infarctions in the distribution of major arteries.

Table 3.

Size and location of infarcts in SIVD cases.

| Case | B&B | Standardized Infarct Scores | Location of infarcts | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVDPS (0–300) | Cystic (0–100) | Lacune (0–100) | Micro (0–100) | Subcortical | Cortical | Posterior fossa | ||

| 1 | II-III | 29 | 17 | 8 | 4 | thalamic | Frontal, occipital (posterior cerebral artery infarction) | |

| 2 | III | 79 | 33 | 17 | 29 | thalamus | amygala, frontal, parietal, occipital | |

| 3 | 0 | 180 | 72 | 75 | 33 | putamen, caudate, | frontal, parietal | pons |

| 4 | II | 89 | 39 | 25 | 25 | caudate, putamen, | frontal, insula | pons, medulla cerebellum |

| 5 | III | 102 | 6 | 67 | 29 | thalamus, putamen, globus pallidus | occipital, hippocampus | |

| 6 | 0 | 42 | 17 | 0 | 25 | caudate, white matter | parietal, temporal, insula | |

| 7 | I | 39 | 6 | 25 | 8 | caudate, thalamus, thalamus, white matter, nucleus basalis | hippocampus | pons |

| 8 | III | 75 | 0 | 50 | 25 | caudate, globus pallidus, frontal white matter, occipital white matter | ||

| 9 | 0 | 77 | 22 | 42 | 13 | putamen, white matter, | frontal, parietal | |

| 10 | II | 21 | 0 | 8 | 13 | caudate, putamen, white matter | frontal | |

| 11 | III | 58 | 33 | 17 | 8 | thalamus | frontal, parietal, occipital | |

| 12 | I | 84 | 17 | 50 | 17 | putamen, thalamus, white matter | parietal, occipital | |

| 13 | II | 44 | 11 | 8 | 25 | caudate, putamen, globus pallidus, thalamus | frontal | |

| 14 | I | 133 | 83 | 50 | 0 | caudate, putamen, globus pallidus, thalamus, white matter | frontal, parietal, (middle cerebral artery infarction) | |

| 15 | III | 25 | 0 | 25 | 0 | frontal white matter, parietal White matter, | ||

| 16 | III | 42 | 0 | 42 | 0 | putamen White matter, |

||

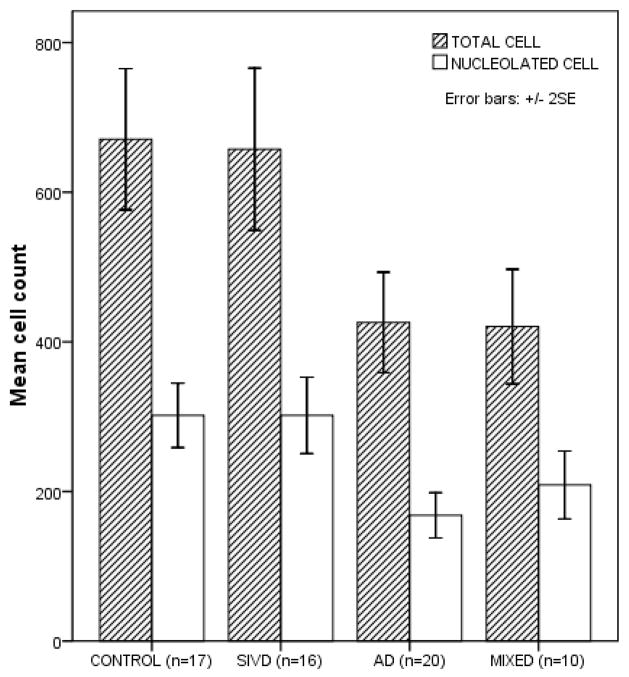

Neuropathology of the NB

The severity of NB neuronal loss varied considerably among groups (Figure 1). While the SIVD group showed no NB neuronal loss, both total and nucleolated cell counts were significantly lower in AD and mixed groups compared with control and SIVD groups (p < 0.0001, ANOVA). Among SIVD subjects, the mean counts of total and nucleolated cells were similar to those in normal controls (p = 0.996 and 1.00 in post-hoc analyses, respectively) and significantly higher than those of AD and mixed groups (p = 0.001 and p < 0.0001 for AD, p = 0.005 and p = 0.024 for mixed group). The SIVD group showed no morphological evidence of retrograde degeneration such as chromatolysis.

Figure 1.

Distribution of cell counts of the Nucleus Basalis (NB) by pathologic diagnosis. The counts of NB neurons varied significantly among groups (p < 0.0001 from ANOVA, both total and nucleolated cell counts). The mean counts of total and nucleolated cell were 670.88±183.60 (SD) and 301.71±83.67 in normal control; 657.53±203.53 and 301.63±95.83 in SIVD; 426.0±143.26 and 168.05±61.60 in AD; 420.50±107.06 and 208.70±63.48 in mixed group. Subcortical Ischemic vascular disease (SIVD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and mixed group includes cognitively normal (CDR = 0) to severe dementia (CDR > 3).

Correlations of NB counts with structural MRI data and CDR

The number of nucleolated NB neurons was not significantly correlated with either the extent of white matter lesions (ρ = −0.204, p = 0.48) or the volume of CGM (ρ = 0.147, p = 0.61) evaluated in the SIVD group (Figure 2). Similar results were obtained using total NB cell counts. Similarly, in the AD group, no significant correlations were found between NB cell counts and WML (ρ = −0.183, p = 0.44) or CGM (ρ = 0.028, p = 0.91). The association between nucleated NB neuronal loss and CDR scores (closest to death) differed by group (Figure 3). Neuronal loss in NB was significantly correlated with CDR scores in AD (Spearman’s ρ = −0.866, p < 0.0001), but not in SIVD (ρ = −0.096, p = 0.772), or in the mixed group (ρ = 0.026, p = 0.942).

Figure 2.

Correlations of nucleolated nucleus basalis (NB) cell counts with white matter lesion volume (WML%, expressed as percentage of the total intracranial volume) and cortical gray matter volume (CGM%, expressed as percentage of total intracranial volume) in subcortical ischemic vascular disease (SIVD) and Alzheimer’s disease group (AD). There were no significant correlations between cell counts of NB and WML or CGM volumes within each group. Correlations of NB cell count with (a) WML% in SIVD (ρ = −0.204, p = 0.483), (b) CGM% in SIVD (ρ = 0.147, p = 0.615), (c) WML% in AD (ρ = −0.183, p = 0.440), (d) CGM% in AD (ρ = 0.028, p = 0.907).

Figure 3.

Distribution of nucleolated NB cell counts by clinical dementia rating (CDR) scores in subcortical ischemic vascular disease (SIVD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and mixed group. Cell counts were correlated with CDR scores only in AD group (ρ = −0.866, p < 0.0001). There were no cases of CDR = 0 or 0.5 in the mixed group.

Discussion

In this autopsy study, we report preservation of NB neurons in cases of SIVD (i.e., no significant AD pathology) compared to normal controls, while confirming significant neuronal loss in cases with AD and mixed AD/SIVD pathology. Although all of our cases had subcortical infarcts, many of them also had cystic and micro infarcts in neocortex (Table 3). Loss of NB neurons in AD is well-established in the literature30–33, but has not been well studied in SIVD or mixed AD/SIVD. Our findings are consistent with a previous study (Mann et al.) of cases with multi-infarct dementia34, but extend the findings of NB sparing to the SIVD+ end of the vascular brain injury spectrum.

Only a few studies have examined NB and cholinergic projections in subcortical VaD, and the status of the network as a whole remains unsettled. Whereas a single case report with CADASIL showed pathologically-intact NB neurons35, another report of 9 CADASIL patients and 14 age-matched controls showed cholinergic neuronal deficits in cerebral cortex with possible retrograde degeneration of NB36. In a study of 6 cases with sporadic Binswanger syndrome, a discrepancy was noted between deficits in cholinergic markers in cerebral cortex and preserved number of neurons in NB neurons37. However, chromatolytic changes were noted in NB neurons, and thought to represent possible retrograde neuronal degeneration. Although our sample of SIVD cases was relatively small (n = 16), it represents a doubling of the number of cases reported in the literature, and showed no evidence of either neuronal loss or chromatolytic changes in NB. Since we did not use stereological methods, it is possible that neuronal swelling might have obscured a minor loss of neurons, as larger cells would be more likely than smaller ones to appear in any given plane of section. However, we also noted no significant loss of neuronal nucleoli, which would be less susceptible (because of their small size relative to section thickness) to counting bias.

As mentioned previously, several investigators have observed decreased choline acetyltransferase levels in cerebral cortex in patients with severe white matter disease (CADASIL or Binswanger syndrome)36, 37. Due to limitations imposed by tissue fixation, we were unable to assess the status of cholinergic projections to cerebral cortex. However, unlike previous studies, we obtained MRI measures of WML, with volumes reaching up to 11% ICV. We hypothesized that severity of WML would correlate with retrograde degeneration of NB in SIVD; whereas severity of cortical atrophy would correlate with number of NB neurons in AD. Contrary to our expectation, cell counts of NB in the SIVD group were not correlated with either volume of WML or CGM. The absence of a correlation casts doubt on the hypothesis that WML causes retrograde degeneration of NB. However, our conclusions should be tempered by the limited sample size and the possibility that retrograde changes might still occur when WML reaches an extreme threshold such as in CADASIL.

Also, contrary to our hypothesis, no correlations were found in the AD group between NB cell counts and CGM. Cullen et al.38 reported that the number of NB (Ch4) neurons of AD was coupled to the volume of CGM. They conducted the study using pathologic specimens to measure CGM volume39, while we used MRI segmentation methods to measure CGM volume40. In addition, the range used to define the AD group (B&B ≥ IV) and the small number of subjects in our study group may also be limiting factors.

The association between numbers of NB neuron and severity of dementia differed by group. While the SIVD and mixed groups showed no correlation, CDR scores were inversely correlated with number of NB neurons in the AD group. In our study, the comparison groups were defined by severity of pathology (not by CDR scores). Correlations between NB number and CDR were not shown in a previous study of Cullen et al., in which the AD subjects all had advanced dementia (CDR 4, and 5)38. A broad range of CDR scores in the AD pathology group was more evenly distributed in the present study (CDR 0 in 2 subjects; CDR 0.5 in 2; CDR 1, 4; CDR 2, 6; CDR 3 or more 6). Iraizoz et al. also reported correlations between NB numbers and clinical dementia measures, where stages ranged from stage I to III using their own rating system41. Since we found no evidence of NB loss in SIVD, the absence of correlation with CDR in SIVD is not surprising. There may not have been sufficient power to detect expected correlations between NB and CDR in the mixed AD/SIVD group, where severity of dementia (CDR) is determined by a combination of AD (where NB loss is expected) and SIVD (where no NB loss occurs.

There are several major strengths of the present study. The subjects of this study were all enrolled in a standardized longitudinal study. All were evaluated under a single neuropathology protocol that involved extensive evaluation and rating of vascular and neurodegenerative lesions at a consensus case conference. Additionally all clinical, radiologic, neuropsychologic, and pathological data were collected prospectively under a single protocol. To our knowledge, no previous studies have included volumetric MRI measures in concert with clinic-pathologic correlations of NB in SIVD.

Several limitations in the sample and method of counting neurons should also be mentioned. The study material came from a convenience, rather than population based sample, so the four groups in this study may not be representative. The comparison groups were defined by cut-off scores, which are often used in the literature but are to some extent arbitrary. Since the number of cases in each group was relatively small (it is difficult to find pure cases of VaD in autopsy studies from AD centers), replication in a larger sample is still warranted. For pathologic methodology, we used representative sections of NB rather than unbiased stereology in counting neurons. Our method was similar to some other studies23, 37 and a meta-analysis stated that studies with non-stereological method showed similar results compared to stereological method32. We report numbers of total neurons and numbers of nucleolated neurons in the complete medial to lateral extent of the nucleus basalis. Thus, our estimates of the number of neurons would not be affected by atrophy of the NB in the coronal plane. Our method, however, would not be sensitive to neuronal loss, should atrophy occur selectively in the sagittal plane.

Conclusion

In this study, the neurons of NB in SIVD were preserved irrespective of severity of cognitive deterioration and extent of MRI-defined white matter lesions, while definite neuronal degeneration which strongly correlated with CDR scores was observed in AD. These findings confirm the absence of primary degeneration of NB in SIVD. Our study is consistent with the possibility that the response to acetyl cholinesterase inhibitors in VaD reflect mixed AD pathology. Our study does not rule out the possibility of distal cholinergic deficiency due to discrete lesions in cholinergic pathways, without primary neuronal degeneration of NB.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging P01AG12435, P50AG05142 (H.C.C) and P50AG16570 (H.V.V.).

References

- 1.Mendez MF, Younesi FL, Perryman KM. Use of donepezil for vascular dementia: preliminary clinical experience. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999 Spring;11(2):268–270. doi: 10.1176/jnp.11.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erkinjuntti T, Kurz A, Gauthier S, Bullock R, Lilienfeld S, Damaraju CV. Efficacy of galantamine in probable vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease combined with cerebrovascular disease: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002 Apr 13;359(9314):1283–1290. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08267-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black S, Roman GC, Geldmacher DS, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of donepezil in vascular dementia: positive results of a 24-week, multicenter, international, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Stroke. 2003 Oct;34(10):2323–2330. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000091396.95360.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkinson D, Doody R, Helme R, et al. Donepezil in vascular dementia: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Neurology. 2003 Aug 26;61(4):479–486. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078943.50032.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mesulam MM, Geula C. Nucleus basalis (Ch4) and cortical cholinergic innervation in the human brain: observations based on the distribution of acetylcholinesterase and choline acetyltransferase. J Comp Neurol. 1988 Sep 8;275(2):216–240. doi: 10.1002/cne.902750205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selden NR, Gitelman DR, Salamon-Murayama N, Parrish TB, Mesulam MM. Trajectories of cholinergic pathways within the cerebral hemispheres of the human brain. Brain. 1998 Dec;121( Pt 12):2249–2257. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.12.2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arendt T, Bigl V, Arendt A, Tennstedt A. Loss of neurons in the nucleus basalis of Meynert in Alzheimer’s disease, paralysis agitans and Korsakoff’s Disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1983;61(2):101–108. doi: 10.1007/BF00697388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iraizoz I, de Lacalle S, Gonzalo LM. Cell loss and nuclear hypertrophy in topographical subdivisions of the nucleus basalis of Meynert in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 1991;41(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90198-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehericy S, Hirsch EC, Cervera-Pierot P, et al. Heterogeneity and selectivity of the degeneration of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Comp Neurol. 1993 Apr 1;330(1):15–31. doi: 10.1002/cne.903300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erkinjuntti T, Inzitari D, Pantoni L, et al. Research criteria for subcortical vascular dementia in clinical trials. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2000;59:23–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6781-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993 Nov;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chui HC, Zarow C, Mack WJ, et al. Cognitive impact of subcortical vascular and Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Ann Neurol. 2006 Dec;60(6):677–687. doi: 10.1002/ana.21009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 Nov;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984 Jul;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chui HC, Victoroff JI, Margolin D, Jagust W, Shankle R, Katzman R. Criteria for the diagnosis of ischemic vascular dementia proposed by the State of California Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnostic and Treatment Centers. Neurology. 1992 Mar;42(3 Pt 1):473–480. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mungas D, Reed BR, Kramer JH. Psychometrically matched measures of global cognition, memory, and executive function for assessment of cognitive decline in older persons. Neuropsychology. 2003 Jul;17(3):380–392. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.17.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reed BR, Mungas DM, Kramer JH, et al. Profiles of neuropsychological impairment in autopsy-defined Alzheimer’s disease and cerebrovascular disease. Brain. 2007 Mar;130(Pt 3):731–739. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology. 1996 Nov;47(5):1113–1124. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991 Apr;41(4):479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyman BT, Trojanowski JQ. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer disease from the National Institute on Aging and the Reagan Institute Working Group on diagnostic criteria for the neuropathological assessment of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997 Oct;56(10):1095–1097. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braak H, Braak E, Bohl J. Staging of Alzheimer-related cortical destruction. Eur Neurol. 1993;33(6):403–408. doi: 10.1159/000116984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jagust WJ, Zheng L, Harvey DJ, et al. Neuropathological basis of magnetic resonance images in aging and dementia. Ann Neurol. 2008 Jan;63(1):72–80. doi: 10.1002/ana.21296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zarow C, Lyness SA, Mortimer JA, Chui HC. Neuronal loss is greater in the locus coeruleus than nucleus basalis and substantia nigra in Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. Arch Neurol. 2003 Mar;60(3):337–341. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chui HC, Bondareff W, Zarow C, Slager U. Stability of neuronal number in the human nucleus basalis of Meynert with age. Neurobiol Aging. 1984 Summer;5(2):83–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(84)90035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doucette R, Ball MJ. Left-right symmetry of neuronal cell counts in the nucleus basalis of Meynert of control and of Alzheimer-diseased brains. Brain Res. 1987 Oct 6;422(2):357–360. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90944-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fein G, Di Sclafani V, Tanabe J, et al. Hippocampal and cortical atrophy predict dementia in subcortical ischemic vascular disease. Neurology. 2000 Dec 12;55(11):1626–1635. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du AT, Schuff N, Chao LL, et al. White matter lesions are associated with cortical atrophy more than entorhinal and hippocampal atrophy. Neurobiol Aging. 2005 Apr;26(4):553–559. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lavretsky H, Zheng L, Weiner MW, et al. The MRI brain correlates of depressed mood, anhedonia, apathy, and anergia in older adults with and without cognitive impairment or dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008 Oct;23(10):1040–1050. doi: 10.1002/gps.2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mueller SG, Mack WJ, Mungas D, et al. Influences of lobar gray matter and white matter lesion load on cognition and mood. Psychiatry Res. 2010 Feb 28;181(2):90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jellinger K. Morphology of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. In: Maurer KRP, Beckmann H, editors. Alzheimer’s disease. Epidemiology, neuropathology, neurochemistry, and clinics. New York: Springer; 1990. pp. 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogels OJ, Broere CA, ter Laak HJ, ten Donkelaar HJ, Nieuwenhuys R, Schulte BP. Cell loss and shrinkage in the nucleus basalis Meynert complex in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1990 Jan-Feb;11(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(90)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyness SA, Zarow C, Chui HC. Neuron loss in key cholinergic and aminergic nuclei in Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. Neurobiol Aging. 2003 Jan-Feb;24(1):1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ezrin-Waters C, Resch L. The nucleus basalis of Meynert. Can J Neurol Sci. 1986 Feb;13(1):8–14. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100035721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mann DM, Yates PO, Marcyniuk B. The nucleus basalis of Meynert in multi-infarct (vascular) dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 1986;71(3–4):332–337. doi: 10.1007/BF00688058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mesulam M, Siddique T, Cohen B. Cholinergic denervation in a pure multi-infarct state: observations on CADASIL. Neurology. 2003 Apr 8;60(7):1183–1185. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055927.22611.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keverne JS, Low WC, Ziabreva I, Court JA, Oakley AE, Kalaria RN. Cholinergic neuronal deficits in CADASIL. Stroke. 2007 Jan;38(1):188–191. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000251787.90695.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomimoto H, Ohtani R, Shibata M, Nakamura N, Ihara M. Loss of cholinergic pathways in vascular dementia of the Binswanger type. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;19(5–6):282–288. doi: 10.1159/000084553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cullen KM, Halliday GM, Double KL, Brooks WS, Creasey H, Broe GA. Cell loss in the nucleus basalis is related to regional cortical atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 1997 Jun;78(3):641–652. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00569-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Double KL, Halliday GM, Kril JJ, et al. Topography of brain atrophy during normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1996 Jul-Aug;17(4):513–521. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(96)00005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clarke LP, Velthuizen RP, Camacho MA, et al. MRI segmentation: methods and applications. Magn Reson Imaging. 1995;13(3):343–368. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(94)00124-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iraizoz I, Guijarro JL, Gonzalo LM, de Lacalle S. Neuropathological changes in the nucleus basalis correlate with clinical measures of dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 1999 Aug;98(2):186–196. doi: 10.1007/s004010051068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]