There is an ever expanding literature base implicating T lymphocytes in the development and progression of numerous cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension. T lymphocytes contribute to the development of hypertension in genetic, angiotensin (Ang)-II and salt-sensitive male experimental animals 1. Among the most definitive studies implicating T lymphocytes in hypertension are studies conducted in Rag-1−/− mice, which lack B and T lymphocytes. Guzik et al. were the first to demonstrate that these mice have a blunted hypertensive response to Ang-II infusion 2. Adoptive transfer of T lymphocytes into male Rag−/− mice restored the hypertensive response to Ang-II; adoptive transfer of B lymphocytes did not alter the blood pressure response. Although low-grade inflammation, and T lymphocytes in particular, are now a recognized hallmark of hypertension, the majority of basic science literature in this field has been conducted exclusively in males, despite the fact that females account for ~50% of all hypertensive cases in the United States.

Therefore, it was with great interest that we read the study by Pollow et al. in the current issue of Hypertension which was designed to determine 1) if there are sex differences in the ability of T lymphocytes to induce Ang-II-dependent hypertension and 2) if sex impacts central or renal T lymphocytes infiltration following Ang-II hypertension 3. Of particular interest, they found that male mice exhibited a significant increase in blood pressure and renal damage to Ang-II following the adoptive transfer of CD3+ T lymphocytes from wildtype male mice. In contrast, blood pressure responses and renal injury to Ang-II were not significantly altered in female Rag−/− mice following adoptive transfer of T lymphocytes from males. Male Rag−/− mice also had greater renal CD3+, CD4+, CD8+ and T regulatory cells (Tregs) following adoptive transfer than female Rag−/− mice despite both sexes having comparable blood pressures, although Ang-II did not significantly impact renal T lymphocyte infiltration in either sex. While this may call into question the role of T lymphocytes in Ang-II hypertension in the Rag−/− mice, male mice did express increased mRNA for the inflammatory cytokines IL-2, MCP-1, and TNF-α following Ang-II infusion that were not found in the female, suggesting an increase in the overall inflammatory profile only in the male. Regardless, the authors clearly demonstrate that female Rag−/− mice limit the pro-hypertensive effects of T lymphocytes from males in Ang-II hypertension. Understanding the mechanisms by which females achieve this relative cardio-protection could provide important insight into novel mechanisms to regulate blood pressure in both sexes.

Although, it has been established that T lymphocytes play a significant role in the development of hypertension, the impact of different T lymphocyte subtypes on blood pressure control remains debatable in males, and unexplored in females. It should be noted that although the study by Pollow et al. did not find an increase in renal T lymphocytes in either sex following Ang-II infusion, T lymphocyte activation was not assessed and neither were pro-inflammatory, pro-hypertensive T helper 17 (Th17) cells3. Th17 cells are effector T lymphocytes that exert their effector function by the secretion of IL-17, IL-21, and IL-23. Interestingly, male IL-17 knockout mice have an attenuated increase in BP following Ang-II infusion, implicating Th17 cells in Ang II-induced increases in BP 4. In line with this observation, we have previously shown that male spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) have greater renal Th17 cell infiltration and higher blood pressure than female SHR, and hypertension in SHR is sensitive to Ang-II inhibition. Based on these data, it would have been interesting to know how sex and Ang-II impacted Th17 cells in Rag−/− mice. In contrast, Tregs are anti-inflammatory T lymphocytes that suppress immune effector function through the secretion of IL-10 and female SHR have more Tregs in their kidneys than males. Direct support for Tregs to modulate blood pressure comes from studies where adoptive transfer of Tregs attenuates Ang-II-induced increases in blood pressure in male mice 5. Since these T lymphocyte subsets potentially have opposing effects on blood pressure regulation, defining T lymphocyte subtypes and examining the ratio of Th17 cells to Tregs may be critical to understanding the role of T lymphocytes in blood pressure control in both sexes. Moreover, since studies suggest differential roles for these T lymphocyte subtypes on blood pressure, it is not unreasonable to postulate that the sex difference in the balance of Th17 cells and Tregs may contribute to observed sex differences in blood pressure control.

It is attractive to hypothesize that the current study by Pollow et al. and the immune system may hold the key for tying together the extensive literature documenting sex differences in cardiovascular disease. There are numerous reports of sex differences in blood pressure and cardiovascular disease both in genetic models of hypertension and in Ang-II-induced hypertension. A number of different molecular mechanisms have been suggested to account for observed sex differences, including oxidative stress, nitric oxide (NO), endothelin, and the renin angiotensin system (RAS), yet how all of these mechanisms may relate to one another has remained unknown 1.

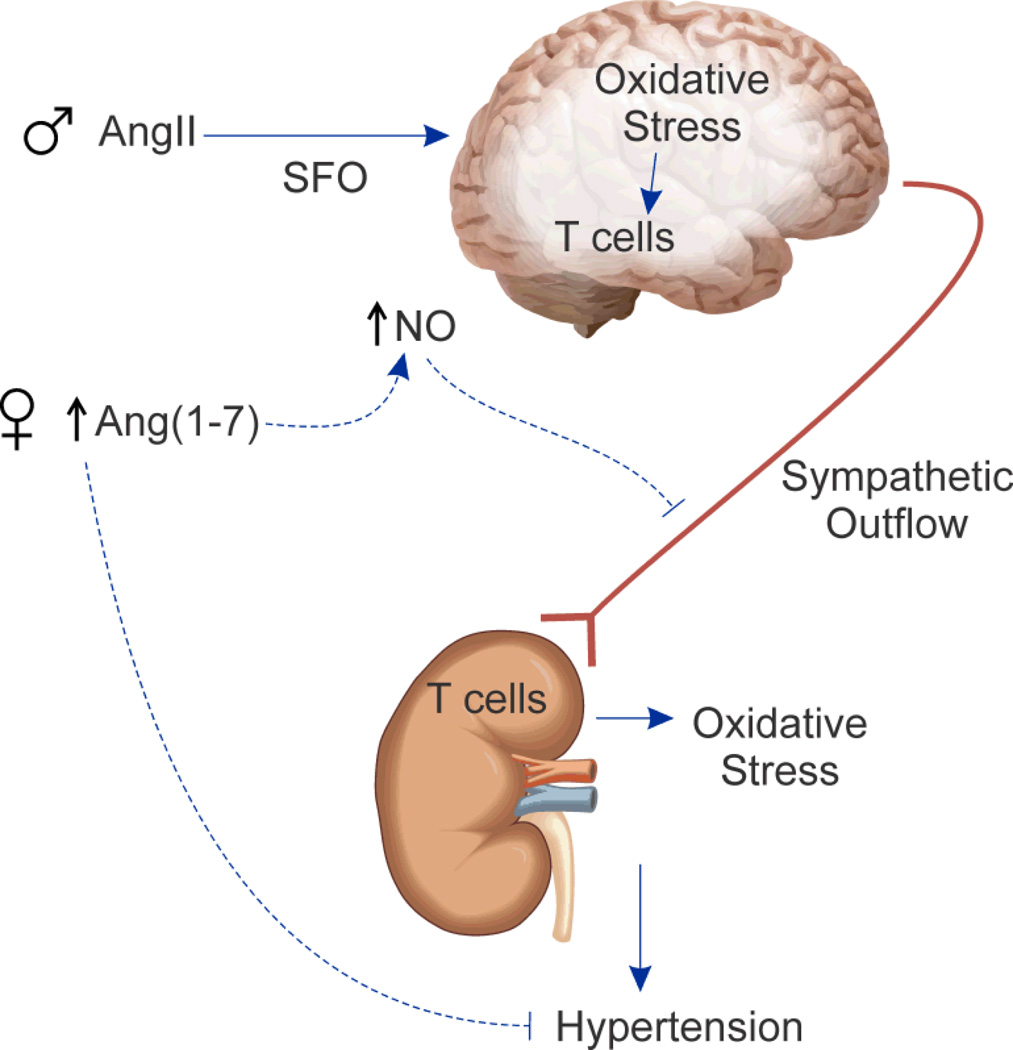

Pollow et al. examine the role of T lymphocytes during Ang-II hypertension and there are well established sex differences in the RAS and in physiological responses to Ang-II. Males typically have greater expression of classical RAS components and greater increases in blood pressure to Ang-II than females 1. Our laboratory and others have shown that males have greater Ang-II-stimulated increases in oxidative stress, which contributes to enhanced increases in blood pressure in males relative to females 1. Harrison’s group has proposed that Ang-II stimulates oxidative stress in the brain resulting in increased sympathetic outflow enhancing Ang-II activation of T lymphocytes, leading to target tissue infiltration of T lymphocytes and further increases in oxidative stress and blood pressure. Recent studies demonstrated that deletion of p22phox, a key NAPDH oxidase subunit, in the subfornical organ (SFO) blunts Ang-II-induced increases in blood pressure in male mice and abolishes Ang-II-induced aortic T lymphocyte infiltration 6. Therefore, greater oxidative stress in males likely correlates with higher levels of T lymphocyte activation and is consistent with higher blood pressure in males under both basal conditions and following Ang-II hypertension. Moreover, female mice have greater nitric oxide synthase (NOS) expression in the SFO than males and central infusion of a non-specific NOS inhibitor increases Ang-II hypertension only in female mice 7. Thus, NO attenuates Ang-II-induced increases in blood pressure in females through reduced sympathetic outflow relative to the males, which is consistent with female mice having less renal T lymphocyte activation relative to males. In support of this idea, we recently published that female SHR are more dependent on NO for blood pressure control than males and females have greater increases in renal T cell infiltration following NOS inhibition. These results support the hypothesis that NO protects females from immune cell infiltration relative to males which further contributes to their lower blood pressure. With the studies of Pollow et al., there is now direct evidence that sex differences in Ang-II hypertension extends to T lymphocytes, and the sex difference in T lymphocytes may underlie and/or explain sex differences in the RAS, oxidative stress and NO (Figure).

Figure 1.

Schematic of proposed sex differences in Ang-II–induced T lymphocyte activation. Greater Ang (1-7) and NO in females may limit Ang-II/T lymphocyte mediated increases in blood pressure.

Females have greater non-classical RAS activation, including Ang (1-7), which blunts Ang-II-induced increases in blood pressure 1. Overexpression of Ang (1-7) in monocrotaline-treated male Sprague Dawley rats increases production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 and attenuates pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 8. Further support for an anti-inflammatory role for Ang (1-7) comes from studies modulating ACE2; ACE2 is a critical enzyme in the formation of Ang (1-7). ACE2 deficiency results in greater increases in renal cytokine and T lymphocyte infiltration following unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) compared to wildtype littermates and renal ischemia-reperfusion results in greater T lymphocyte infiltration in ACE2 knock-out mice compared to wildtype 9, 10. Therefore, greater Ang (1-7) may also actively limit Ang-II-induced increases in T lymphocyte activation and blood pressure in females. This may also be related to sex differences in oxidative stress and NO, since Ang (1-7) stimulates NO, further linking the RAS, NO and inflammation. With this in mind, it would be intriguing to determine the impact of Ang (1-7) infusion on blood pressure and the immune profile following adoptive transfer of CD3+ T lymphocytes in males and females.

While there are few studies that have directly examined the role of individual T cell subtypes in hypertensive men and women, there is also clinical evidence linking immune system activation to cardiovascular disease and blood pressure. HIV+ men and women have a lower prevalence of hypertension compared to healthy individuals and treatment with anti-retroviral therapy is positively associated with increases in CD4+ T cells and blood pressure 11. In addition, non-specific inhibition of B and T lymphocytes using mycophenolate mofetil significantly decreases blood pressure in hypertensive men and women 12. Consistent with experimental studies suggesting increases in Th17 cells promote hypertension, levels of circulating IL-17 are increased in diabetic patients with hypertension compared to normotensive patients 4. While less has been done clinically to assess Tregs and IL-10 in essential hypertension, preeclampsia has been shown to be associated with decreases in these anti-inflammatory factors 13. Based on our expanding understanding of the potential complex role played by the immune system in blood pressure control, more clinical work is needed in this field to determine the potential clinical application of immune system modulation for the treatment of hypertension.

In closing, of the 68 million Americans with hypertension, fewer than 46% have their blood pressure adequately controlled and women are more likely than men to have uncontrolled hypertension. This underscores the critical need for new treatment options for both men and women. Greater understanding of the mechanisms by which females are able to maintain their cardiovascular protection holds the potential to provide better treatment options for all hypertensive patients. The current work by Pollow et al. as well as others in this field may hold the promise of explaining a fundamental difference between males and females that underlies a wide-ranging scope of biochemical and physiological sex differences allowing for greater understanding and better treatment options that have remained elusive for decades.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Greg Sullivan for artistic and technical expertise in the generation of the figure. Brain image based on work by ‘_DJ_’ (http://www.flickr.com/photos/flamephoenix1991) used under Creative Commons Share-Alike License.

Sources of funding: The authors acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (1R01 HL-093271-01A1 to JCS).

Footnotes

Disclosures: NONE

References

- 1.Zimmerman MA, Sullivan JC. Hypertension: What's sex got to do with it? Physiology. 2013;28:234–244. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00013.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2449–2460. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollow DUJ, Romero-Aleshire M, Sandberg K, Nikolich-Zugich J, Brooks HL, Hay M. Sex differences in T-lymphocyte tissue infiltration and development of angiotensin II hypertension. Hypertension. 2014 doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03581. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madhur MS, Lob HE, McCann LA, Iwakura Y, Blinder Y, Guzik TJ, Harrison DG. Interleukin 17 promotes angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2010;55:500–507. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barhoumi T, Kasal DA, Li MW, Shbat L, Laurant P, Neves MF, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular injury. Hypertension. 2011;57:469–476. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.162941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lob HE, Schultz D, Marvar PJ, Davisson RL, Harrison DG. Role of the nadph oxidases in the subfornical organ in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;61:382–387. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xue B, Badaue-Passos D, Jr, Guo F, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Hay M, Johnson AK. Sex differences and central protective effect of 17beta-estradiol in the development of aldosterone/NaCl-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1577–H1585. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01255.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shenoy V, Ferreira AJ, Qi Y, Fraga-Silva RA, Diez-Freire C, Dooies A, Jun JY, Sriramula S, Mariappan N, Pourang D, Venugopal CS, Francis J, Reudelhuber T, Santos RA, Patel JM, Raizada MK, Katovich MJ. The angiotensin-converting enzyme 2/angiogenesis-(1-7)/mas axis confers cardiopulmonary protection against lung fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1065–1072. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1840OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Z, Huang XR, Chen HY, Penninger JM, Lan HY. Loss of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 enhances TGF-beta/smad-mediated renal fibrosis and NF-kappab-driven renal inflammation in a mouse model of obstructive nephropathy. Lab Invest. 2012;92:650–661. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang F, Liu GC, Zhou X, Yang S, Reich HN, Williams V, Hu A, Pan J, Konvalinka A, Oudit GY, Scholey JW, John R. Loss of ACE2 exacerbates murine renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palacios R, Santos J, Garcia A, Castells E, Gonzalez M, Ruiz J, Marquez M. Impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on blood pressure in HIV-infected patients. A prospective study in a cohort of naive patients. HIV Medicine. 2006;7:10–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrera J, Ferrebuz A, MacGregor EG, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Mycophenolate mofetil treatment improves hypertension in patients with psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:S218–S225. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hennessy A, Pilmore HL, Simmons LA, Painter DM. A deficiency of placental IL-10 in preeclampsia. J Immunol. 1999;163:3491–3495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]