Abstract

Objective

Knee replacement (KR) represents a clinically important endpoint of knee osteoarthritis (KOA). Here we examine the four-year trajectory of femoro-tibial cartilage thickness loss prior to KR vs. non-replaced controls.

Methods

A nested case-control study was performed in Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) participants: Cases with KR between 12–60 month (M) follow-up were each matched with one control (without KR through 60M) by age, sex, and baseline radiographic stage. Femoro-tibial cartilage thickness was measured quantitatively using MRI at the annual visit prior to KR occurrence (T0), and at –-4years prior to T0 (T−1 to T−4). Cartilage loss between cases and controls was compared using paired t-tests and conditional logistic regression.

Results

189 knees of 164 OAI participants (55% women, age 64±8.7; BMI 29±4.5) had KR and longitudinal cartilage data. Comparison of annualized slopes of change across all time points revealed greater loss in the central medial tibia (primary outcome) in KRs than in controls (94±137 vs. 55±104µm; p=0.0017 [paired-t]; odds ratio [OR] 1.36 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.08-1.70). The discrimination was stronger for T−2→T0 (OR 1.61 [1.33-1.95], n=127) than for T−1→T0, and was not statistically significant for intervals prior to T−2 (i.e. T−4→T−2, OR 0.97 [0.67–1.41], n=60). Results were similar for total medial femoro-tibial cartilage loss (secondary outcome), and when adjusting for pain and BMI.

Conclusions

In knees with subsequent replacement, cartilage loss accelerates in the two years, and particularly in the year prior to surgery, compared with controls. Whether slowing this cartilage loss can delay KR remains to be determined.

Keywords: Knee Osteoarthritis, Knee Replacement, Knee Arthroplasty, Cartilage Loss, Magnetic Resonance Imaging

INTRODUCTION

Knee Osteoarthritis (KOA) is estimated to affect >10% of the population in the United States1 and, although commonly regarded as a disease of the elderly, symptomatic KOA is diagnosed today at a mean age of only 56 years, with a lifetime risk of 45%2. KOA is associated with substantial functional limitations and disability3,4, causes significant morbidity, mortality, and reduction in the quality of life,5, and substantial health care utilization6. In absence of effective disease modifying therapies, a large portion of the costs involved in managing KOA is driven by knee replacements (KR), and KR therefore represents a clinically important endpoint7. The number of annual KRs in the U.S. has doubled in the last decade, with a disproportionate increase amongst younger adults; its prevalence now is considerably greater than that of rheumatoid arthritis8.

Few studies have examined cartilage loss quantitatively with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) prior to KR7,9–12. However, these prospective cohort studies generally did not adequately adjust for the fact that knees with advanced radiographic disease exhibit greater cartilage loss13–15 and also are more likely to receive KR than those being at an earlier stage of disease. Using a case/control design with matching for baseline radiographic disease stage (Kellgren Lawrence grade [KLG]), sex, and age, we have reported that cartilage thickness loss was significantly greater in the year prior to KR than in control knees that did not subsequently undergo KR16. However, KOA is a slowly evolving disorder, and one year of observation represents a relatively short time period in relation to the time between incident symptoms or radiographic signs and need for KR. Elucidating the trajectory of cartilage loss over several years prior to KR can help in the understanding how structural change in KOA progresses prior to that knee reaching a critical clinical state. Further, this analysis may help in characterizing potential time windows for structure modification of cartilage by therapeutic intervention with disease modifying drugs (DMOADs) or other measures.

The purpose of this study therefore was to examine the trajectory of cartilage loss over four years prior to KR, compared with matched controls that did not undergo KR during this observation interval. Specifically, we asked whether cartilage loss between KRs and control knees differs during observation intervals >1 year prior to KR.

METHODS

Study Design

This study was ancillary to the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) multi-center longitudinal cohort study (OAI) (http://www.oai.ucsf.edu/)16,17. The participants were recruited at four centers16–18 and studied annually over 4 years, using 3 Tesla MRI16–19 and other methods. OAI participants were 45–79 years old and with (or at risk of symptomatic KOA) in at least one knee17. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Boards at each of the sites, and all participants gave informed consent17. OAI participants were examined and interviewed annually about having received a KR in the preceding 12-months (M). This was confirmed by radiography, or from hospital records when radiographs were not available.

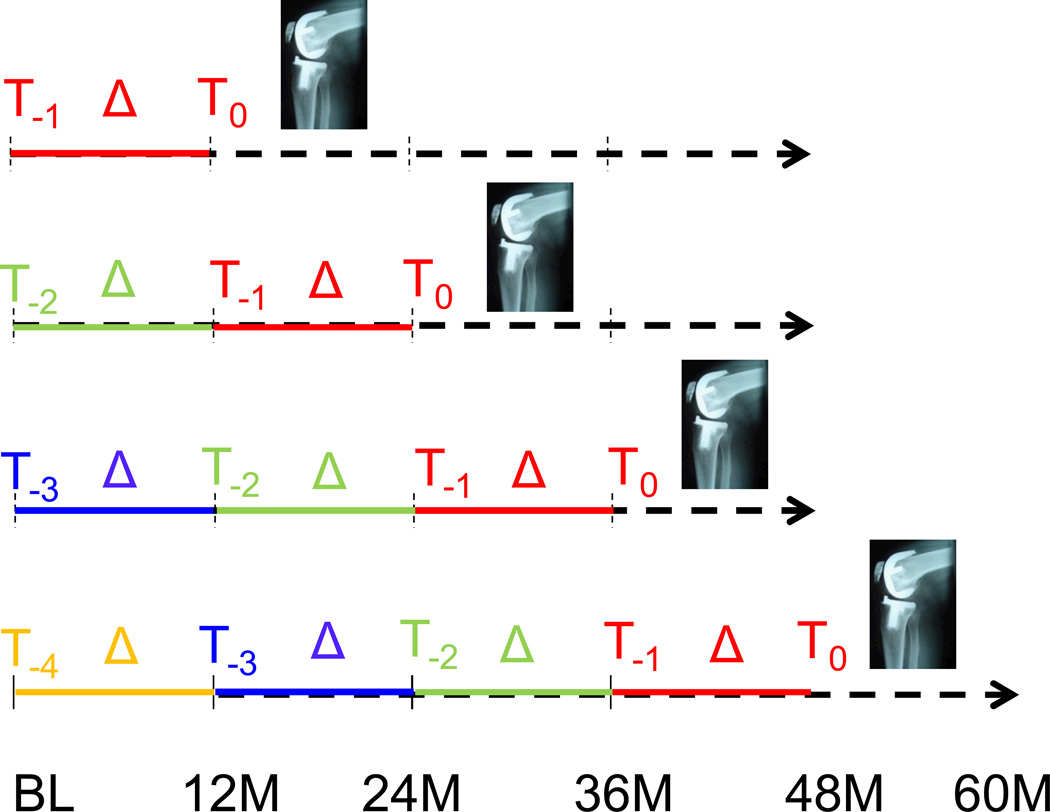

To be eligible as a case, a KR had to recorded at 24 month (M), 36M, 48M, or 60M follow-up, and MRI acquisitions acceptable for quantitative analysis had to be present for at least two prior (but not necessarily for all preceding) time points (Fig. 1). The annual MRI examination prior to KR occurrence was termed T0, and the annual examinations preceding T0 were designated T−1 through T−4. KRs detected at 12M were not included, because they did not have longitudinal data prior to KR. KRs detected at the 24M had two prior annual measurements (T0 and T−1), and those observed at 60M had up to five previous annual measurements (T0 through T−4; Fig. 1). If both knees of one participant were replaced at the same, or at different time points, both were included in the analysis (for statistical treatment of potentially correlated observations, please see below).

Figure 1.

Graph showing the study design and methods: OAI participants with KR occurrence between 24 and 60 month (M) follow-up had quantitative cartilage analysis at 2–5 prior time points, providing a minimum of one to a maximum four 1-year observation periods

Control knees were selected from those without self-reported KR and without evidence of KR on radiographs between baseline and 60M. Knees did not qualify as controls if the opposite knee received a KR during the study. Controls had to have MRIs available at time points corresponding with those of the KR cases (T0 through T−4). Cases and controls were matched 1:1 by sex, age (±5years), and radiographic disease stage, documented by central reading at the baseline visit (KLG strata of 0–1, 2, 3, and 4). KLGs from release 0.4 from the central readings of the fixed flexion radiographs (performed at Boston University) were taken)17. In a second (post-hoc) step, attempts were made to match cases with medial joint space narrowing (JSN) to controls with medial JSN, and cases with lateral JSN to controls with lateral JSN: 137 cases could be matched to controls with the same medial/lateral JSN pattern.

Quantitative MRI Analysis

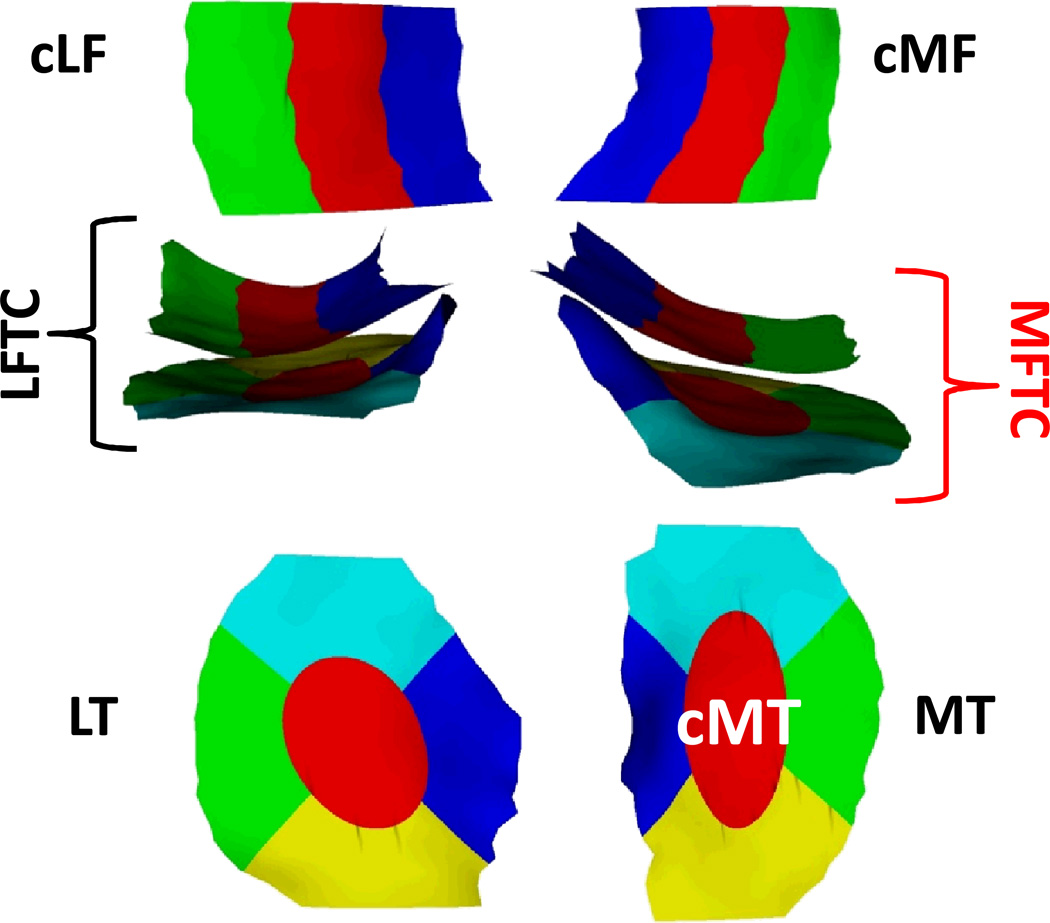

The quantitative MR image analysis relied on an oblique sagittal double-echo steadystate (DESS) sequence water excitation17,19–21. Segmentation of the medial and lateral femoro-tibial cartilages was performed at one image analysis center (Chondrometrics GmbH, Ainring, Germany), the readers being fully blinded to case/control status and to the acquisition order of the different time points16,18. The total area of subchondral bone (tAB) and cartilage surface area (AC) of the weight-bearing femoro-tibial compartment were analysed16,18, and all segmentations were quality controlled by one of two experts (S.M. or F.E) [10,12]. The mean cartilage thickness over the total area of subchondral bone (ThCtAB.Me) was derived after 3D surface reconstruction, using software by Chondrometrics GmbH (Ainring, Germany)22. The cartilage thickness was then computed for the medial and lateral (femorotibial) compartment, for the medial and lateral tibiae and weight-bearing femoral condyles, and for five tibial (central, external, internal, anterior, posterior) and three femoral subregions (central, external, internal)22 (Fig. 2). Change in cartilage thickness was computed by subtracting the thickness measured at one time point from that observed at a later time point; absolute cartilage loss hence was expressed as a negative value in µm. The change was not reported in percent (%), because percent values become very high when the cartilage thickness at the earlier time point is already close to zero.

Figure 2.

View of the weight-bearing femoral and their subregions from inferior (top), of the femoro-tibial plates from anterior (middle), and of the tibiae and their subregions from superior : the central medial tibia (cMT) was selected as the primary, and the total medial femoro-tibial compartment (MFTC) as the secondary outcome.

MT = medial tibia, LT = lateral tibia, cMF = weight-bearing (central) medial femur, cLF = weight-bearing (central) lateral femur, LFTC = lateral femorotibial compartment.

Statistical Analysis

All tests were performed using SAS software (version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The central subregion of the medial tibia (cMT; Fig. 2) was selected as the primary analytic outcome, because it had been shown to best discriminate between KR cases and non-KR controls in our previous work on longitudinal change over one year prior to KR16. Cartilage thickness in the total medial femoro-tibial compartment (MFTC) was used as a secondary endpoint, because it represents the cartilage loss across the entire compartment and also was shown to discriminate significantly between cases and controls. MFTC cartilage thickness was determined as the sum of that in the medial tibia and the weight-bearing medial femur (Fig. 2). Correlations between KR cases and their sex-, age-, and KLG-matched controls, and correlations between knees of the few participants with bilateral KRs, were accounted for by general estimating equation (GEE) models, with an independent working correlation followed by the robust sandwich estimator for the covariance matrix of the regression coefficients23,24.

Rates of cMT and MFTC cartilage loss (Fig. 2) were compared between various longitudinal one- and two- year intervals prior to KR, analyzing the same time intervals relative to baseline between the KR cases and the matched controls. Slopes of annual cMT and MFTC cartilage loss were also calculated for each knee using knee-specific linear regressions vs. time, making use of all available time points. Statistical comparisons included paired t-tests between case/control pairs, and case-control conditional logistic regression odd ratios (ccOR) per standard deviation. Robustness of these comparisons was assessed by performing additional adjustment for the effects of baseline BMI and pain at the start of each observation interval (ccORbp). These adjustments were made for standard categories of the body mass index (BMI: normal/overweight/obese) and for standard categories of pain frequency status in the past year, commonly used to classify symptomatic KOA (no pain/infrequent pain/frequent pain). Values reported at the beginning of each observation interval (i.e. at T−2 for the T−2→T−1 interval) were used for that purpose. These adjustments were made to verify whether the crude comparisons were robust, because previous studies have shown an association of cartilage loss with BMI and pain25–27. Pain frequency was used rather than the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC), because pain frequency questions asked by the OAI (Did you have pain on most days of the month, in at least one of the past 12 months?) cover a much longer period than the WOMAC, and because in contrast to pain frequency26,27, WOMAC was not found to be significantly associated with subsequent cartilage loss in a recent study28.

Case-control areas under the receiver operation curve (ccAUC)29 were calculated to allow for direct comparison with our previous report16. Sensitivity analyses were performed by repeating the above analyses after excluding case/control pairs with a mismatch in baseline medial/lateral JSN status. Given previous observations of superior discrimination between case/control pairs with “early” baseline radiographic disease status16, the above analyses were also conducted in a stratum of KLG 0–2 knees.

RESULTS

Sample description

222 knees of 192 OAI participants received a KR between 24M and 60M (37 at 24M, 60 at 36M, 58 at 48M, and 67 at 60M; Fig. 1). Of these, 189 from 164 participants (55% women; age 64±8.7; BMI 29±4.5) had a matched control and MRI readings for at least two prior time points to calculate longitudinal cartilage loss. Of the case/control pairs, 9 were baseline KLG 0, 9 KLG1, 40 KLG2, 71 KLG3, and 60 KLG4. 180 had total knee replacement, eight partial medial knee replacement, and one patello-femoral replacement.

Central medial tibia (cMT): primary analytic focus

Analysis of slopes of annual change from the available time points revealed significantly greater rates of cartilage loss in the central medial tibia (cMT) in KRs (94±137µm p.a.) than in controls (55±104µm p.a.). The difference was statistically significant with and without adjustment for potential confounders (p=0.0017 for paired t-test; p= 0.008 for the unadjusted, and 0.014 for BMI and pain-frequency adjusted conditional logistic regression model. The ccOR was 1.36 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.08–1.70) without, and 1.34 (95% CI: 1.06–1.70) with adjustment for BMI and pain frequency. The ccAUC adjusting for matching variables was 0.60 (95% CI 0.54–0.65).

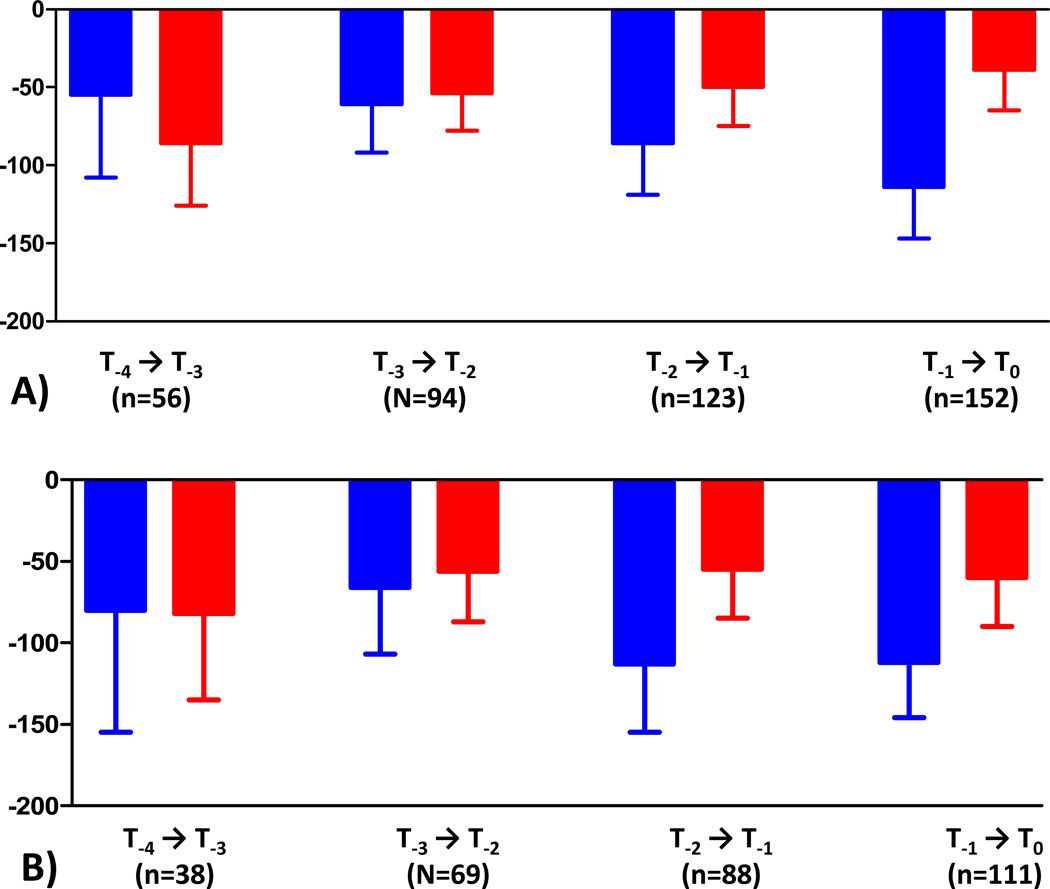

When examining the trajectory of cartilage loss during the annual time intervals prior to KR, the ratio of cMT cartilage loss in KRs vs. controls was 2.92:1 during T−1→T0 (n=152), 1.72:1 during T−2→T−1 (n=123), 1.13:1 during T−3→T−2 (n=94), and 0.64:1 during T−4→T−3 (n=56)(Table 1; Fig. 3a). The difference attained statistical significance for T−1→T0, but not for preceding time periods. When restricting the analysis to cases with T−1→T0 data that also had T−2→T0 and T−2→T−1 data available (n=127), the rate of change was very similar to that observed in the larger sample. The observed cMT cartilage loss was greater in controls than in KR cases during T−4→T−3 (Table 1, Fig. 3a).

Table 1.

Rates of cartilage loss (mean±standard deviation) in the central medial tibia (cMT; primary analytic focus; see Fig. 2) in cases with knee replacement (KR) vs. matched controls

|

T−4 → T−3 (n=56) |

T−3 → T−2 (N=94) |

T−2 → T−1 (n=123) |

T−1 → T0 (n=152) |

T−4 → T−2 (n=60) |

T−2 → T0 (n=127) |

|

| Total KR Sample | ||||||

| KRs (µm) | −55±198 | −61±152 | −86±184 | −114±207 | −119±255 | −209±281 |

| Controls (µm) | −86±147 | −54±119 | −50±137 | −39±159 | −125±175 | −61±156 |

| p (paired t) | 0.3334 | 0.7211 | 0.0913 | 0.0007 | 0.8612 | <0.0001 |

| ccAUC [95%CI] | 0.57 [.46–.68] | 0.48 [.40–57] | 0.53 [.45–60] | 0.59 [.52–65] | 0.51 [.41–62] | 0.66 [.60–73] |

| ccOR [95%CI] | 0.85 [.59–1.22] | 1.05 [.79–1.39] | 1.21 [1.00–1.47] | 1.42 *** [1.16–1.72] | 0.97 [.67–1.41] | 1.61*** [1.33–1.95] |

| ccORbp [95%CI] | 0.85 [.54–1.35] | 1.06 [.80–1.40] | 1.19 [0.98–1.45] | 1.48 *** [1.20–1.82] | 1.21 [.83–1.76] | 1.64 *** [1.34–1.99] |

| Excluding patello-femoral KR and femoro-tibial KRs with medial/lateral JSN mismatch | ||||||

|

T−4 → T−3 (n=38) |

T−3 → T−2 (N=69) |

T−2 → T−1 (n=88) |

T−1 → T0 (n=111) |

T−4 → T−2 (n=41) |

T−2 → T0 (n=86) |

|

| KRs (µm) | −80±226 | −66±167 | −113±199 | −112±183 | −146±297 | −230±252 |

| Controls (µm) | −82±162 | −56±128 | −55±142 | −60±160 | −123±195 | −79±161 |

| p (paired t) | 0.9687 | 0.6725 | 0.0348 | 0.0314 | 0.6406 | <0.0001 |

| ccOR [95%CI] | 0.99 [.69–1.43] | 1.07 [.77–1.48] | 1.32* [1.06–1.64] | 1.31* [1.03–1.68] | 1.10 [.73–1.66] | 1.77*** [1.37–2.30] |

| ccORbp [95%CI] | 1.00 [.66–1.51] | 1.09 [.80–1.49] | 1.29* [1.03–1.63] | 1.41* [1.08–1.84] | 1.29 [.83–2.02] | 1.83*** [1.35–2.48] |

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001;

T0 = annual MRI examination time point prior to KR occurrence; T−1, T−2, T−3, and T−4 = time points preceding T0 by 1,2,3 and 4 years respectively. T−4→T−3 hence represents an observation interval 4 to 3 years prior to the last measurement before KR (only available from 60M follow-up KRs), T−3→T−2 an observation interval 3 to 2 years prior (available from 48M and 60M follow-up KRs), T2→T−1 an observation interval 2 to 1 years prior (available from 36M, 48M and 60M follow-up KRs), and T−1→T0 an observation interval 1 year prior to the last measurement before KR (available from 24M, 36M, 48M and 60M follow-up KRs); T−4→T−2 represents an observation interval 4 to 2 years prior to the last measurement before KR, and T−2→T0 an interval 2 years prior to the last measurement before KR.

ccAUC: area under the curve from logistic regression model for cartilage loss discriminating KR cases from controls, adjusted for case-control baseline matching variables (age, gender, KL grade);

ccOR, conditional logistic regression odds-ratios (ORs) adjusted baseline matching variables;

ccORbp : ccOR after adjusting out the effects of baseline BMI and Pain at the start of each interval.

ORs are based on standardized measures (per SD of cartilage loss in each “change” interval)

Figure 3.

Observed rates of cartilage loss (mean and upper 95% CI) in the central subregion of the medial tibia (cMT; see Fig. 2) over 4 years prior to the occurrence of knee replacement (KRs) and in matched, non-replaced controls (same sex, age [±5 years] and baseline KLGs (values are without adjustment for pain frequency and BMI). The error bars show the lower limits of the 95% CIs

A) Total KR sample

B) Subsample of femoro-tibial KRs without medial/lateral JSN mismatch

When restricting the analysis to the 137 femorotibial KRs matched with controls based on the same medial/lateral JSN status (also excluding the one patellofemoral KR), slope analysis confirmed significantly greater rates of cartilage loss in KRs (105±141µm p.a.) than in controls (64±110µm p.a.). Again, the difference was statistically significant with and without adjustment for potential confounders, the ccOR being 1.39 (95% CI: 1.04–1.86) without and 1.39 (95% CI: 1.03–1.89) with adjustment for BMI and pain frequency. The ratio of cMT cartilage loss between KR cases and controls was 1.87:1 during T−1→T0, 2.05:1 during T−2→T−1, 1.18:1 during T−3→T−2, and 0.98:1 during T−4→T−3 (Table 1; Fig. 3b). The difference attained statistical significance for T−1→T0 and for T−2→T−1, but not for preceding time intervals (Table 1, Figure 3b).

The strongest difference in cMT cartilage loss between KRs and controls was observed for the two-year interval prior to KR occurrence (T−2→T0; Table 1). The ratio of longitudinal cartilage was 3.43:1 for all KRs, and 2.91:1 for the subsample of femoro-tibial KR/control pairs with medial/lateral JSN match. No significant difference in cartilage loss was found during T−4→T−2 (Table 1).

Medial femoro-tibial compartment: secondary analytic focus

The results in the total medial femoro-tibial compartment (MFTC) were similar to those observed in cMT (Table 2). Again, the slope analysis of annual change from the available time points revealed significantly greater rates of cartilage loss in KRs (117±178µm p.a.) than in controls (70±102µm p.a.), the difference being statistically significant with and without adjustment for potential confounders (p<0.001). The ccOR was 1.31 (95% CI: 1.14–1.50) without, and 1.31 (95% CI 1.11–1.53) with adjustment for BMI and pain frequency; the ccAUC was 0.56 (95% CI 0.50–0.62). Again, the cartilage change during T−2→T0 discriminated best between KR cases and controls, and results were similar when only including femoro-tibial KR/control pairs with medial/lateral JSN match (Table 2).

Table 2.

Rates of cartilage loss (mean±standard deviation) in the total medial femorotibial compartment (MFTC: secondary analytic focus; see Fig. 2) in cases with knee replacement (KRs) vs. matched controls

|

T−4 → T−3 (n=56) |

T−3 → T−2 (N=94) |

T−2 → T−1 (n=123) |

T−1 → T0 (n=152) |

T−4 → T−2 (n=60) |

T−2 → T0 (n=127) |

|

| Total KR Sample | ||||||

| KRs (µm) | −78±219 | −83±191 | −95±225 | −146±323 | −169±279 | −254±414 |

| Controls (µm) | −74±166 | −69±110 | −71±158 | −59±163 | −138±194 | −97±189 |

| p (paired t) | 0.9108 | 0.5287 | 0.3100 | 0.0027 | 0.4475 | 0.0002 |

| ccAUC [95%CI] | 0.51 [.40–.61] | 0.48 [.40–.57] | 0.52 [.44–.59] | 0.55 [.48–.61] | 0.53 [.43–.64] | 0.60 [.53–.67] |

| ccOR [95%CI] | 1.02 [.75–1.38] | 1.07 [.88–1.29] | 1.12 [.92–1.36] | 1.30*** [1.13–1.51] | 1.13 [.84–1.53] | 1.40*** [1.19–1.64] |

| ccORbp [95%CI] | 1.10 [.79–1.52] | 1.07 [.88–1.30] | 1.12 [.92–1.36] | 1.32*** [1.14–1.53] | 1.60 [0.99–2.59] | 1.42*** [1.21–1.66] |

| Excluding patella-femoral KR and femoro-tibial KRs with medial/lateral JSN mismatch | ||||||

|

T−4 → T−3 (n=38) |

T−3 → T−2 (N=69) |

T−2 → T−1 (n=88) |

T−1 → T0 (n=111) |

T−4 → T−2(n=41) |

T−2 → T0 (n=86) |

|

| KRs (µm) | −99±245 | −103±207 | −111±247 | −138±252 | −210±321 | −259±355 |

| Controls (µm) | −75±166 | −75±110 | −72±164 | −84±156 | −157±203 | −115±186 |

| p (paired t) | 0.5727 | 0.3371 | 0.2166 | 0.0505 | 0.3322 | 0.0013 |

| ccOR [95%CI] | 1.13 [.80–1.58] | 1.12 [.90–1.38] | 1.17 [0.94–1.44] | 1.24* [1.03 –1.50] | 1.21 [.86–1.72] | 1.46*** [1.18–1.80] |

| ccORbp [95%CI] | 1.10 [.72–1.67] | 1.14 [.92–1.41] | 1.17 [.93–1.46] | 1.30* [1.05–1.60] | 1.57 [0.94–2.64] | 1.50*** [1.22–1.86] |

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001;

T0 = annual MRI examination time point prior to KR occurrence; T−1, T−2, T−3, and T−4 = time points preceding T0 by 1,2,3 and 4 years respectively. T−4→T−3 hence represents an observation interval 4 to 3 years prior to the last measurement before KR (only available from 60M follow-up KRs), T−3→T−2 an observation interval 3 to 2 years prior (available from 48M and 60M follow-up KRs), T2→T−1 an observation interval 2 to 1 years prior (available from 36M, 48M and 60M follow-up KRs), and T−1→T0 an observation interval 1 year prior to the last measurement before KR (available from 24M, 36M, 48M and 60M follow-up KRs); T−4→T−2 represents an observation interval 4 to 2 years prior to the last measurement before KR, and T−2→T0 an interval 2 years prior to the last measurement before KR.

ccAUC: area under the curve from logistic regression model for cartilage loss discriminating KR cases from controls, adjusted for case-control baseline matching variables (age, gender, KL grade);

ccOR, conditional logistic regression odds-ratios (ORs) adjusted baseline matching variables;

ccORbp : ccOR after adjusting out the effects of baseline BMI and Pain at the start of each interval.

ORs are based on standardized measures (per SD of cartilage loss in each “change” interval)

Subsample with baseline KLG 0–2

In the KLG 0–2 case/control pairs (n=58), slope analysis revealed substantially cMT cartilage loss in KRs (79±134µm) but almost no loss in controls (4±51µm); the difference was statistically significant with and without adjustment for potential confounders (p≤0.002). The ccOR was 2.90 (95% CI: 1.49–5.64) without, and 2.55 (95%CI 1.25–5.21) with adjustment for BMI and pain frequency (Table 3); the ccAUC was 0.70 (95% CI 0.60–0.79).

Table 3.

Rates of cartilage loss (mean±standard deviation) in the central medial tibia (cMT) in the subcohort of cases and matched controls with a baseline Kellgren Lawrence Grade (KLG 0–2)

| T−4 → T−3 (n=22) |

T−3 → T−2 (N=32) |

T−2 → T−1 (n=39) |

T−1 → T0 (n=44) |

T−4 → T−2 (n=23) |

T−2 → T0 (n=42) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KRs (µm) | 18±167 | −20±92 | −64±215 | −143±263 | −22±147 | −249±359 |

| Controls (µm) | −51±125 | −20±83 | −23±110 | −37±109 | −68±146 | 5±105 |

| p (paired t) | 0.1292 | 0.9985 | 0.3100 | <0.0001 | 0.2708 | <0.0001 |

| ccAUC [95%CI] | 0.61 [.44–.78] | 0.52 [.37–.67] | 0.52 [.39–.65] | 0.72 [.61–.83] | 0.55 [.38–.72] | 0.74 [.63–.85] |

| ccOR [95%CI] | 0.56 [.26–1.21] | 1.00 [.45–2.21] | 1.23 [.86–1.74] | 2.86*** [1.45–5.65] | 0.64 [.34–1.23] | 2.54** [1.38–4.65] |

| ccORbp [95%CI] | 0.28 [.03–2.47] | 1.09 [.38–3.17] | 1.23 [.88–1.73] | 3.32** [1.33–8.29] | 0.96 [.41–2.27] | 2.72** [1.66–4.44] |

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001;

T0 = annual MRI examination time point prior to KR occurrence; T−1, T−2, T−3, and T−4 = time points preceding T0 by 1,2,3 and 4 years respectively. T−4→T−3 hence represents an observation interval 4 to 3 years prior to the last measurement before KR (only available from 60M follow-up KRs), T−3→T−2 an observation interval 3 to 2 years prior (available from 48M and 60M follow-up KRs), T2→T−1 an observation interval 2 to 1 years prior (available from 36M, 48M and 60M follow-up KRs), and T−1→T0 an observation interval 1 year prior to the last measurement before KR (available from 24M, 36M, 48M and 60M follow-up KRs); T−4→T−2 represents an observation interval 4 to 2 years prior to the last measurement before KR, and T−2→T0 an interval 2 years prior to the last measurement before KR.

ccAUC: area under the curve from logistic regression model for cartilage loss discriminating KR cases from controls, adjusted for case-control baseline matching variables (age, gender, KL grade);

ccOR, conditional logistic regression odds-ratios (ORs) adjusted baseline matching variables;

ccORbp : ccOR after adjusting out the effects of baseline BMI and Pain at the start of each interval.

ORs are based on standardized measures (per SD of cartilage loss in each “change” interval)

Results for the subsample excluding femoro-tibial KRs with medial/lateral JSN mismatch were not provided, because of the low number of observations.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to report the trajectory of knee cartilage loss for up to four years prior to KR, and the first to compare the observed trajectory with that of matched, non-replaced controls. The current work extends previous studies7,16 in several ways: a) It included up to five annual time points prior to KR, allowing us to explore the rate of cartilage loss rates over 4 years before the knees reached a critical clinical endpoint; b) it included additional KR cases from the OAI recorded at 60M follow-up, adding statistical power to our previous analysis16; c) mismatch of medial/lateral JSN between cases and controls with identical KLG was reduced post-hoc, by optimizing the matching criteria based on JSN location, and by performing sensitivity analyses in only those femoro-tibial KR cases/control pairs without medial/lateral JSN mismatch.

The T0, T−1, T−2, T−3, T−4 approach was selected to “synchronize” the observations of cartilage thickness change in relation to the time point of the KR. Doing this, we found that, in knees that had KR, the annual (medial) cartilage thickness loss was significantly (and substantially) greater in the two years prior to KR, compared to that in control knees without KR, but matched for age, sex, and baseline radiographic status. The differences in cartilage loss became less over time when moving back to earlier (annual) time intervals. The strongest difference between KR cases and matched controls was observed for T−2→T0, whereas no significantly different rates of cartilage loss were observed during the two-year interval preceding the above (T−4→T−2), or during one year intervals prior to T−2 (T−4→T−3 or T−3→T−2). A similar trajectory of differences between KR cases and non-KR controls was previously reported for knee symptoms30 and parallels those observed here for cartilage loss. A limitation of the study is that different sample sizes were available for time periods of different duration for observing cartilage loss prior to KR. Only KRs occurring at 60M had all time intervals between T−4 and T0 available, whereas knees with a KR at 24M only contributed T−1 and T0. However, because knees with very different grades of clinical and radiographic OA were included in the OAI cohort, there is no reason to assume that those with a KR at 24M were “faster progressors” than those with a KR at 60M, as they may already have been at a more advanced stage of disease at baseline. Also, the statistical analyses were not performed between periods, but between cases and matched controls within these periods, with the same time points (relative to baseline) being compared in cases versus controls. The current study focused on two specific anatomical regions of interest, cMT and MFTC. This choice was made because we previously found that the difference in cartilage loss between KRs and matched controls in the year prior to KR was greater in the medial than in the lateral femoro-tibial compartment, and greater in central than in peripheral subregions16. However, results for other cartilage subregions were thoroughly documented over one year prior to KR in our previous report, including the lateral femorotibial compartment, but were less discriminatory than cMT16. The results (AUCs) reported here for T−1→T0 cartilage thickness loss are similar to those previously reported for cMT and MFTC in the smaller sample, not including 60M KRs16.

At first impression, it may appear counterintuitive that discrimination for T−2→T0 was superior to that for T−1→T0 in the total KR sample (including partial medial/lateral JSN mismatch), given that T−2→T−1 differences in case/control pairs were less than T−1→T0 differences. However, quantitative measures of cartilage loss are subject to test-retest errors20,22,31–34, which become particularly important when relatively small longitudinal changes are measured over relatively short observation periods18. In the current and in previous studies35, the magnitude of a two-year change was approx. twice that of a one-year change, whereas the precision errors can be assumed to be similar for both observation periods. The ratio between the magnitude of change and these errors is hence more favorable for longer observation intervals35. Although the “true change” during T−1→T0 may be more discriminative than that during T−2→T0, the “observed changes” for T−2→T0 may be less variable and hence more robust for differentiating rates of structural progression between KR cases and controls.

The medical treatment for osteoarthritis is currently restricted to control symptoms, and if that fails, KR remains the only therapeutic option. Yet, while KR is a highly effective treatment for end-stage KOA, KR recipients can experience persistent pain and severe complications after the intervention8. Further, many patients will require revision surgery, particularly with life expectancy continuing to increase, and with KR being performed (or required) at increasingly younger age8,36. Currently, no medical intervention has been approved for disease (i.e. structure-) modifying therapy of KOA by a regulatory agency. Regulatory guidance for approval of disease-modifying intervention recommends that reduction or prevention of pathology in joint tissue should be accompanied by benefits in clinical outcomes37. The state at which KR is medically indicated is associated with strong pain and functional limitation, and severe reduction in quality of life; KR therefore may be considered as ultimate joint “death” or “failure” and therefore represents a very relevant and important clinical outcome7.

The current and our previous study16 are unique in that they compare the rate of cartilage loss between KRs and controls by fully controlling for baseline radiographic disease stage. In previous cohort studies7,9,12, those with advanced radiographic disease (higher KLGs) had a greater likelihood of receiving a KR, and it is known that knees with higher KLG and/or JSN grades exhibit greater cartilage loss (and other structural features of disease) than those with less severe radiographic disease13,14,18. The AUCs and ORs reported here for cartilage loss have to be interpreted with the stringent baseline matching for KLG in mind: Compared with diagnostic imaging methodology used in osteoporosis, the current approach resembles one by which a (new) microstructural imaging method is compared longitudinally in subjects prior to a bone fracture versus controls without, with subjects matched for baseline bone mineral density (BMD). Our findings would be equivalent to that of the microstructural imaging method being shown to provide discrimination of bone fracture status by longitudinal differences in bone microarchitecture, in the absence of baseline BMD differences between fracture cases and non-fractured controls.

Other structural features of KOA (i.e. effusion, meniscus, bone marrow lesions) and their longitudinal changes may be co-linearly related to the cartilage thickness change and risk of KR observed here. The current paper did not aim to assess causal relationships, but to evaluate quantitative MRI cartilage measures as “prognostic” markers38. In future studies, quantitative cartilage loss examined by MRI may be examined side-by side with other (clinical, radiographic, MRI-based, molecular) markers, to identify which (combination of) marker(s) is most efficient in predicting the risk of KR, and potentially also in evaluating the efficacy of structure modifying intervention.

In conclusion, this first study on the longer-term trajectory of cartilage thickness change prior to KR shows that cartilage loss accelerates in the two years before, and particularly in the year before, KR surgery, compared to matched control knees. Observed differences in case/control pairs were strongest during a 2 year measurement interval prior to KR, but did not reach statistical significance during previous time intervals. Whether slowing this cartilage loss, by pharmacological or other interventions, can delay KR surgery remains to be determined.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the following operators at Chondrometrics GmbH: Gudrun Goldmann, Linda Jakobi, Manuela Kunz, Tanja Killer, Dr. Susanne Maschek, Jana Matthes, Tina Matthes, Sabine Mühlsimer, Julia Niedermeier, Annette Thebis, Dr. Barbara Wehr and Dr. Gabriele Zeitelhack for the segmentation of the magnetic resonance imaging data. Susanne Maschek is to be thanked for quality control readings of the segmentations.

Further, the authors would like to thank the readers of the fixed flexion radiographs at Boston University for the central KL grading, the OAI investigators, clinic staff and OAI participants at each of the OAI clinical centers for their contributions in acquiring the publicly available clinical and imaging data, the team at the OAI coordinating center, particularly John Lynch, Maurice Dockrell, and Jason Maeda, for their help in selecting images and verifying the knee replacements radiographically, and Stephanie Green and Hilary Peterson at Pittsburgh for administrative support. This manuscript has received the approval of the OAI Publications Committee based on a review of its scientific content and data interpretation.

FUNDING SOURCES

The study and image acquisition was supported by the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI), a public-private partnership comprised of five contracts (N01-AR-2-2258; N01-AR-2-2259; N01-AR-2-2260; N01-AR-2-2261; N01-AR-2-2262) funded by the National Institutes of Health, a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services, and conducted by the OAI Study Investigators. Private funding partners include Pfizer, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Merck Research Laboratories; and GlaxoSmithKline. Private sector funding for the OAI is managed by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health.

The image analysis of this study was partly funded by Novartis Pharma AG (Basel, Switzerland), by MerckKGaA (Darmstadt, Germany), by a contract with the University of Pittsburgh (Pivotal OAI MRI Analyses POMA: NIH/NHLBI Contract No. HHSN2682010000 21C), by a vendor contract from the OAI coordinating center at University of California, San Francisco (N01-AR-2-2258), and by an ancillary grant to the OAI held by Northwestern University (NIH/NIAMS R01 AR052918 [Sharma]).

The statistical data analysis was funded by a contract with the University of Pittsburgh (Pivotal OAI MRI Analyses POMA: NIH/NHLBI Contract No. HHSN2682010000 21C) and the University of Pittsburgh Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Center (MCRC) for Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases (P60 AR054731). The sponsors were not directly involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. However, the co-authors participating in the study (and partly being affiliated with study sponsors) were involved in all above aspects of the study. The statistical analysis of the data (based on the entire raw data set and evaluation of the study protocol, and pre-specified plan for data analysis) was conducted by an independent statistical team at an academic institution (the University of Pittsburgh) which was independent of the commercial sponsors. No compensation or funding from a commercial sponsors was received for conducting the statistical analyses.

Footnotes

- the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data,

- drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content,

- final approval of the version to be submitted.

- Felix Eckstein is CEO of Chondrometrics GmbH, a company providing MR image analysis services to academic researchers and to industry. He has provided consulting services to MerckSerono, Novartis and Abbvie, has prepared educational sessions for Medtronic, and has received research support from Pfizer, Eli Lilly, MerckSerono, Glaxo Smith Kline, Centocor R&D, Wyeth, Novartis, Stryker, Abbvie, Kolon, and Synarc.

- Sebastian Cotofana has a part time employment with Chondrometrics GmbH

- Wolfgang Wirth has a part time employment with Chondrometrics GmbH and is a co-owner of Chondrometrics GmbH.

- Ali Guermazi is President and co-owner of the Boston Core Imaging Lab (BICL), a company providing MRI reading services to academic researchers and to industry. He has provided consulting services to Novartis, Merck Serono, Sanofi-Aventis, TissueGene and Genzyme.

- Frank Roemer is CMO and co-owner of the Boston Core Imaging Lab (BICL), a company providing MRI reading services to academic researchers and to industry. He has provided consulting services to Merck Serono.

- Markus John is a former employee of Novartis Pharma AG.

- Christoph Ladel is an employee of MerckKGaA.

- C. Kent Kwoh has provided consulting services to Novartis and has received research support from Astra-Zeneca

- Robert Boudreau, Zhijie Wang, Michael J. Hannon, Michael Nevitt, Leena Sharma, and David J. Hunter have no conflict of interest to declare

REFERENCES

- 1.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, Deyo RA, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Losina E, Weinstein AM, Reichmann WM, Burbine SA, Solomon DH, Daigle ME, et al. Lifetime Risk and Age at Diagnosis of Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis in the US. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:703–711. doi: 10.1002/acr.21898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guccione AA, Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Anthony JM, Zhang Y, Wilson PW, et al. The effects of specific medical conditions on the functional limitations of elders in the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:351–358. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Losina E, Walensky RP, Reichmann WM, Holt HL, Gerlovin H, Solomon DH, et al. Impact of obesity and knee osteoarthritis on morbidity and mortality in older Americans. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:217–226. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-154-4-201102150-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright EA, Katz JN, Cisternas MG, Kessler CL, Wagenseller A, Losina E. Impact of knee osteoarthritis on health care resource utilization in a US population-based national sample. Med Care. 2010;48:785–791. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e419b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pelletier JP, Cooper C, Peterfy C, Reginster JY, Brandi ML, Bruyere O, et al. What is the predictive value of MRI for the occurrence of knee replacement surgery in knee osteoarthritis? Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1594–1604. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinstein AM, Rome BN, Reichmann WM, Collins JE, Burbine SA, Thornhill TS, et al. Estimating the burden of total knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:385–392. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cicuttini FM, Jones G, Forbes A, Wluka AE. Rate of cartilage loss at two years predicts subsequent total knee arthroplasty: a prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1124–1127. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.021253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cicuttini F, Hankin J, Jones G, Wluka A. Comparison of conventional standing knee radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging in assessing progression of tibiofemoral joint osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:722–727. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanamas SK, Wluka AE, Pelletier JP, Martel-Pelletier J, Abram F, Wang Y, et al. The association between subchondral bone cysts and tibial cartilage volume and risk of joint replacement in people with knee osteoarthritis: a longitudinal study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R58. doi: 10.1186/ar2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raynauld JP, Martel-Pelletier J, Haraoui B, Choquette D, Dorais M, Wildi LM, et al. Risk factors predictive of joint replacement in a 2-year multicentre clinical trial in knee osteoarthritis using MRI: results from over 6 years of observation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1382–1388. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.146407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eckstein F, Nevitt M, Gimona A, Picha K, Lee JH, Davies RY, et al. Rates of change and sensitivity to change in cartilage morphology in healthy knees and in knees with mild, moderate, and end-stage radiographic osteoarthritis: Results from 831 participants from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;63:311–319. doi: 10.1002/acr.20370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wirth W, Buck R, Nevitt M, Le Graverand MP, Benichou O, Dreher D, et al. MRI-based extended ordered values more efficiently differentiate cartilage loss in knees with and without joint space narrowing than region-specific approaches using MRI or radiography--data from the OA initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:689–699. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wirth W, Nevitt M, Le Graverand MP, Lynch J, Maschek S, Hudelmaier M, et al. Lateral and Medial Joint Space Narrowing Predict Subsequent Cartilage Loss in the Narrowed, but not in the Non-narrowed Femorotibial Compartment - Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckstein F, Kwoh CK, Boudreau R, Wang Z, Hannon M, Cotofana S, et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging measures of cartilage predict knee replacement - a case-control study from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013:707–714. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckstein F, Wirth W, Nevitt MC. Recent advances in osteoarthritis imaging-the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:622–630. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eckstein F, Mc Culloch CE, Lynch JA, Nevitt M, Kwoh CK, Maschek S, et al. How do short-term rates of femorotibial cartilage change compare to long-term changes? Four year follow-up data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20:1250–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterfy CG, Schneider E, Nevitt M. The osteoarthritis initiative: report on the design rationale for the magnetic resonance imaging protocol for the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:1433–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eckstein F, Hudelmaier M, Wirth W, Kiefer B, Jackson R, Yu J, et al. Double echo steady state magnetic resonance imaging of knee articular cartilage at 3 Tesla: a pilot study for the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:433–441. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.039370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wirth W, Nevitt M, Hellio Le Graverand MP, Benichou O, Dreher D, Davies RY, et al. Sensitivity to change of cartilage morphometry using coronal FLASH, sagittal DESS, and coronal MPR DESS protocols--comparative data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:547–554. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wirth W, Eckstein F. A technique for regional analysis of femorotibial cartilage thickness based on quantitative magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2008;27:737–744. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2007.907323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fay MP, Graubard BI, Freedman LS, Midthune DN. Conditional logistic regression with sandwich estimators: application to a meta-analysis. Biometrics. 1998;54:195–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pelletier JP, Raynauld JP, Berthiaume MJ, Abram F, Choquette D, Haraoui B, et al. Risk factors associated with the loss of cartilage volume on weight-bearing areas in knee osteoarthritis patients assessed by quantitative magnetic resonance imaging: a longitudinal study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:R74. doi: 10.1186/ar2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saunders J, Ding C, Cicuttini F, Jones G. Radiographic osteoarthritis and pain are independent predictors of knee cartilage loss: a prospective study. Intern Med J. 2011:5910–5994. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eckstein F, Cotofana S, Wirth W, Nevitt M, John MR, Dreher D, et al. Greater rates of cartilage loss in painful knees than in pain-free knees after adjustment for radiographic disease stage: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2257–2267. doi: 10.1002/art.30414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Illingworth KD, El BY, Siewert K, Scaife SL, El-Amin S, Saleh KJ. Correlation of WOMAC and KOOS scores to tibiofemoral cartilage loss on plain radiography and 3 Tesla MRI: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janes H, Pepe MS. Matching in studies of classification accuracy: implications for analysis, efficiency, and assessment of incremental value. Biometrics. 2008;64:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boudreau RM, Hunter DJ, Wang Z, Roemer F, Eckstein F, Hannon MJ, et al. A virtual knee joint replacment clinical endpoint based on longitudinal trends and thresholds in KOOS knee pain and funtion in Osteoarthritis Initiative participants. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(Suppl.):S1040. [Abstract]. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eckstein F, Cicuttini F, Raynauld JP, Waterton JC, Peterfy C. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of articular cartilage in knee osteoarthritis (OA): morphological assessment. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(Suppl 1):46–75. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eckstein F, Buck RJ, Burstein D, Charles HC, Crim J, Hudelmaier M, et al. Precision of 3.0 Tesla quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of cartilage morphology in a multicentre clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1683–1688. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.076919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wirth W, Hellio Le Graverand MP, Wyman BT, Maschek S, Hudelmaier M, Hitzl W, et al. Regional analysis of femorotibial cartilage loss in a subsample from the Osteoarthritis Initiative progression subcohort. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hudelmaier M, Wirth W, Wehr B, Kraus V, Wyman BT, Hellio Le Graverand MP, et al. Femorotibial cartilage morphology: reproducibility of different metrics and femoral regions, and sensitivity to change in disease. Cells Tissues Organs. 2010;192:340–350. doi: 10.1159/000318178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wirth W, Larroque S, Davies RY, Nevitt M, Gimona A, Baribaud F, et al. Comparison of 1-year vs 2-year change in regional cartilage thickness in osteoarthritis results from 346 participants from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ravi B, Croxford R, Reichmann WM, Losina E, Katz JN, Hawker GA. The changing demographics of total joint arthroplasty recipients in the United States and Ontario from 2001 to 2007. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26:637–647. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guidance for industry on clinical development programs for drugs, devices and biological products intended for the treatment of osteoarthritis (OA) 1999 wwwfdagov//GuidanceComlianceRegulatoryInformation/GUidances/ucm071577pdf.

- 38.Bauer DC, Hunter DJ, Abramson SB, Attur M, Corr M, Felson D, et al. Classification of osteoarthritis biomarkers: a proposed approach. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:723–727. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]