Abstract

Recent findings suggested that the age of peak ultra-marathon performance seemed to increase with increasing race distance. The present study investigated the age of peak ultra-marathon performance for runners competing in time-limited ultra-marathons held from 6 to 240 h (i.e. 10 days) during 1975–2013. Age and running performance in 20,238 (21 %) female and 76,888 (79 %) male finishes (6,863 women and 24,725 men, 22 and 78 %, respectively) were analysed using mixed-effects regression analyses. The annual number of finishes increased for both women and men in all races. About one half of the finishers completed at least one race and the other half completed more than one race. Most of the finishes were achieved in the fourth decade of life. The age of the best ultra-marathon performance increased with increasing race duration, also when only one or at least five successful finishes were considered. The lowest age of peak ultra-marathon performance was in 6 h (33.7 years, 95 % CI 32.5–34.9 years) and the highest in 48 h (46.8 years, 95 % CI 46.1–47.5). With increasing number of finishes, the athletes improved performance. Across years, performance decreased, the age of peak performance increased, and the age of peak ultra-marathon performance increased with increasing number of finishes. In summary, the age of peak ultra-marathon performance increased and performance decreased in time-limited ultra-marathons. The age of peak ultra-marathon performance increased with increasing race duration and with increasing number of finishes. These athletes improved race performance with increasing number of finishes.

Keywords: Master athlete, Ultra-running, Sex, Endurance performance

Introduction

Ultra-running is devoted to covering the sport of long-distance running. In recent years, an increase in popularity in ultra-marathon running has been reported (Cejka et al. 2013; Hoffman and Wegelin 2009; Rüst et al. 2013). The standard definition of an ultra-marathon is any running distance longer than the classical marathon distance of 42.195 km (i.e. 26.2 miles). Therefore, the shortest standard distance considered as an ultra-marathon is 50 km (i.e. 31.07 miles). Other standard ultra-distances are 50 miles, 100 miles, 100 km or longer, and a series of events lasting for specified time periods such as 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, 6 days (i.e. 144 h) and 10 days (i.e. 240 h) (Ultrarunning, http://www.ultrarunning.com/).

Regarding the participation trends in the classical marathon distance, there is a general trend in the USA with an increase in the number of finishers since 1976 with an estimated all-time high in 2011 with 518,000 marathon finishers (Running USA, www.runningusa.org/). Since 1980, the percentage of master runners (i.e. athletes older than 40 years) increased from 26 to 46 % in 2012 (Running USA, www.runningusa.org/). Recent studies showed that the number of master runners competing in large city marathons such as the “New York City Marathon” (Lepers and Cattagni 2012) and ultra-marathons such as 24-h ultra-marathons (Zingg et al. 2013a) or “Badwater” and “Spartathlon” (Zingg et al. 2013b), increased the previous years.

Different variables such as anthropometric and physiological characteristics, training variables and previous experience have been established to predict performance in ultra-marathon running. It has been shown that age (Knechtle et al. 2010), training (Knechtle et al. 2011a) and previous experience such as personal best marathon time (Knechtle et al. 2009, 2011b) were the best predictors in ultra-marathon running. For male 100-km ultra-marathoners, training speed, mean weekly running kilometer and age were the best predictors for 100-km race time (Knechtle et al. 2010). The age of peak athletic performance is important for any sportsman to plan a career. Previous studies have examined the age of peak athletic performance for ultra-endurance sports disciplines such as triathlon (Gallmann et al. 2014; Knechtle et al. 2012b; Stiefel et al. 2013), swimming (Eichenberger et al. 2013; Rüst et al. 2014), and running (Rüst et al. 2013).

In long-distance triathlon, it seemed that the age of peak performance increased with increasing race distance. For the Ironman distance (i.e. 3.8 km swimming, 180 km cycling and 42 km running), women and men peaked at a similar age of ∼32–33 years with no sex difference (Stiefel et al. 2013). For the Triple Iron ultra-triathlon distance (i.e. 11.4 km swimming, 540 km cycling and 126.6 km running), the mean age of the fastest male finishers was ∼38 years and increased to ∼41 years for athletes competing in a Deca Iron ultra-triathlon (i.e. 38 km swimming, 1,800 km cycling and 422 km running) (Knechtle et al. 2012b).

For ultra-marathoners, the age of peak ultra-marathon performance has been investigated for single races (Da Fonseca-Engelhardt et al. 2013; Knechtle et al. 2012a) or single distances (Rüst et al. 2013; Zingg et al. 2013a). It seemed that the age of peak ultra-marathon performance increased with increasing race distance or duration as it has been shown for long-distance triathlon. For elite marathoners competing in the seven marathons of the “World Marathon Majors Series”, women were older (∼29.8 years) than men (∼28.9 years) (Hunter et al. 2011). Regarding ultra-marathons, the age of peak performance in the annual ten fastest women and men competing in 100-km ultra-marathons between 1960 and 2012 remained unchanged at ∼34.9 and ∼34.5 years, respectively (Cejka et al. 2014). In 100-miles ultra-marathoners, the mean age of the annual top ten runners between 1998 and 2011 was ∼39.2 years for women and ∼37.2 years for men (Rüst et al. 2013). The age of peak running performance was not different between women and men and showed no changes across the years (Rüst et al. 2013). In 24-h ultra-marathoners competing between 1998 and 2011, the age of the annual top ten women decreased from ∼43 to ∼40 years. For the annual top ten men, the age of peak running speed remained unchanged at ∼42 years (Zingg et al. 2013a). In two of the toughest ultra-marathons in the world, the “Badwater” and “Spartathlon”, the fastest finishers were also at the age of ∼40 years (Da Fonseca-Engelhardt et al. 2013). In the “Badwater”, the age of the annual five fastest men decreased between 2000 and 2012 from ∼42 to ∼40 years. For women, the age remained unchanged at ∼42 years. In the “Spartathlon”, the age of the annual five fastest finishers was unchanged at ∼40 years for men and ∼45 years for women.

The assumption that the age of peak ultra-marathon performance increases with increasing race distance needs, however, verification. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to determine the age of peak running speed in ultra-marathoners competing in time-limited race from 6 to 240 h (i.e. 10 days) during the 1975–2013 period. Based upon recent findings, it was hypothesized that the age of peak ultra-marathon performance would increase with increasing duration of the event.

Methods

Ethics

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of St. Gallen, Switzerland, with a waiver of the requirement for informed consent given that the study involved the analysis of publicly available data.

Data sampling and data analysis

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of St. Gallen, Switzerland, with a waiver of the requirement for informed consent given that the study involved the analysis of publicly available data. Data were retrieved from Deutsche Ultramarathon Vereinigung (DUV) http://www.ultra-marathon.org/. This website records all race results of ultra-marathons held worldwide in the section http://statistik.d-u-v.org/. Race results of ultra-marathons held between 1975 and 2013 in time-limited races in 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, 144 (6 days) and 240 h (10 days) were collected. For each race, all female and male finishers were considered for each calendar year from 1975 to 2013.

Statistical analysis

To explore data graphically, we used smoothing methods (i.e. loess if number of observations <1,000, otherwise gam both implemented in the statistical software). The 95 % confidence regions are displayed and linear or quadratic fit for each ultra-marathon, if appropriate. To compute the peak of age, we used a mixed-effects regression model with finisher as random variable to consider finishers who completed several races. To take into account the increase variance of distances by increasing race time, the distance was logarithmized to base e. We included sex, age, squared age, ultra-marathon, calendar year and the number of successful finishes for each finisher (i.e. experience) as fixed variables. We defined “experienced” when the same athlete had achieved at least five successful finishes in a specific ultra-marathon. We considered interaction effects and the final model was selected by means of Akaike information criterion (AIC). Since the logarithmized distribution of the distances was left skewed, we defined a cut-off for each ultra marathon to exclude finishes which are below these cut-offs (Tables 1 and 2). At the end of the selection process, we closed with the following model (1):

| 1 |

Table 1.

Number of finishes and finishers and cut-offs for each ultra-marathon before cut-off (column A) and after cut-off (column B). Column C shows the reduction of the finishes and finishers after applying the cut-off. Total finishers do not correspond to the sum of column A and B, respectively, since a finisher may participate in several ultra-marathons. Column D shows the mean of the age and the standard deviation of the finishers; column E the mean of distances and the standard deviations

| A | B | C | D | E | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before cut-off | After cut-off | % Reduction | Mean (SD) of age | Mean (SD) of distance | |||||||

| Race time (h) | Cut-off | Finishes | Finishers | Finishes | Finishers | Finishes | Finishers | Before cut-off | After cut-off | Before cut-off | After cut-off |

| 6 | 20 | 29,284 | 15,236 | 29,284 | 15,236 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 45.9 (10.2) | 45.9 (10.2) | 55.8 (8.9) | 55.8 (8.9) |

| 12 | 50 | 26,010 | 14,504 | 23,831 | 13,334 | 8.4 | 8.1 | 45.4 (10.9) | 45.3 (10.7) | 85.0 (23.3) | 88.6 (20.8) |

| 24 | 90 | 41,679 | 16,750 | 34,619 | 13,492 | 16.9 | 19.5 | 46.2 (10.4) | 46.3 (10.1) | 137 (47) | 152 (37) |

| 48 | 12 | 5549 | 2349 | 5161 | 2139 | 7.0 | 8.9 | 46.4 (10.9) | 46.3 (10.8) | 220 (69) | 229 (61) |

| 72 | 140 | 606 | 355 | 536 | 325 | 11.6 | 8.5 | 51.7 (12.0) | 51.6 (12.0) | 246 (90) | 266 (74) |

| 144 | 250 | 3504 | 1396 | 3292 | 1281 | 6.1 | 8.2 | 46.3 (11.2) | 46.2 (11.1) | 508 (157) | 530 (136) |

| 240 | 500 | 413 | 196 | 403 | 193 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 42.7 (11.5) | 42.6 (11.5) | 803 (172) | 814 (157) |

| Total | – | 107,045 | 35,120 | 97,250 | 31,588 | 9.2 | 10.1 | 45.9 (10.6) | 46.0 (10.4) | – | – |

Table 2.

Number of finishes and finishers before and after the cut-off was applied

| Finishes | Finishers | Finishes | Finishers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | |||

| Original | 22,857 | 84,188 | 7968 | 27,152 | 107,045 | 35,120 |

| (21.4 %) | (78.6) | (22.7 %) | (77.2 %) | |||

| After cut-off | 20,238 | 76,888 | 6863 | 24,725 | 97,126 | 31,588 |

| (20.8 %) | (79.2 %) | (21.7 %) | (78.3 %) | |||

where ln is the natural logarithm, UM is the ultra-marathon (duration), and ID is the identification number of each finisher. We validated the model by visual inspection of normal probability plot and Tukey-Anscombe plot which showed a slightly left skewed distribution and constant variance of the residuals against fitted values. The peak of age for each ultra-marathon was computed by using the coefficients from the regression analysis and the Nelder-Mead method which was implemented in the statistical software. 95 % Confidence intervals for peak of ages were computed be resampling 500 times the residuals of the regression model (1). After adding the residuals to the fitted values to get new “resampled” distance values, 500 regressions with model (1) were performed and 500 peak of ages to compute standard errors of the peak age and 95 % confidence intervals. To test if the difference of peak of ages were significant, t test were performed without Bonferroni-correction of p values. The statistical analysis and graphical outputs were performed using the statistical software R (version 3.02).

Results

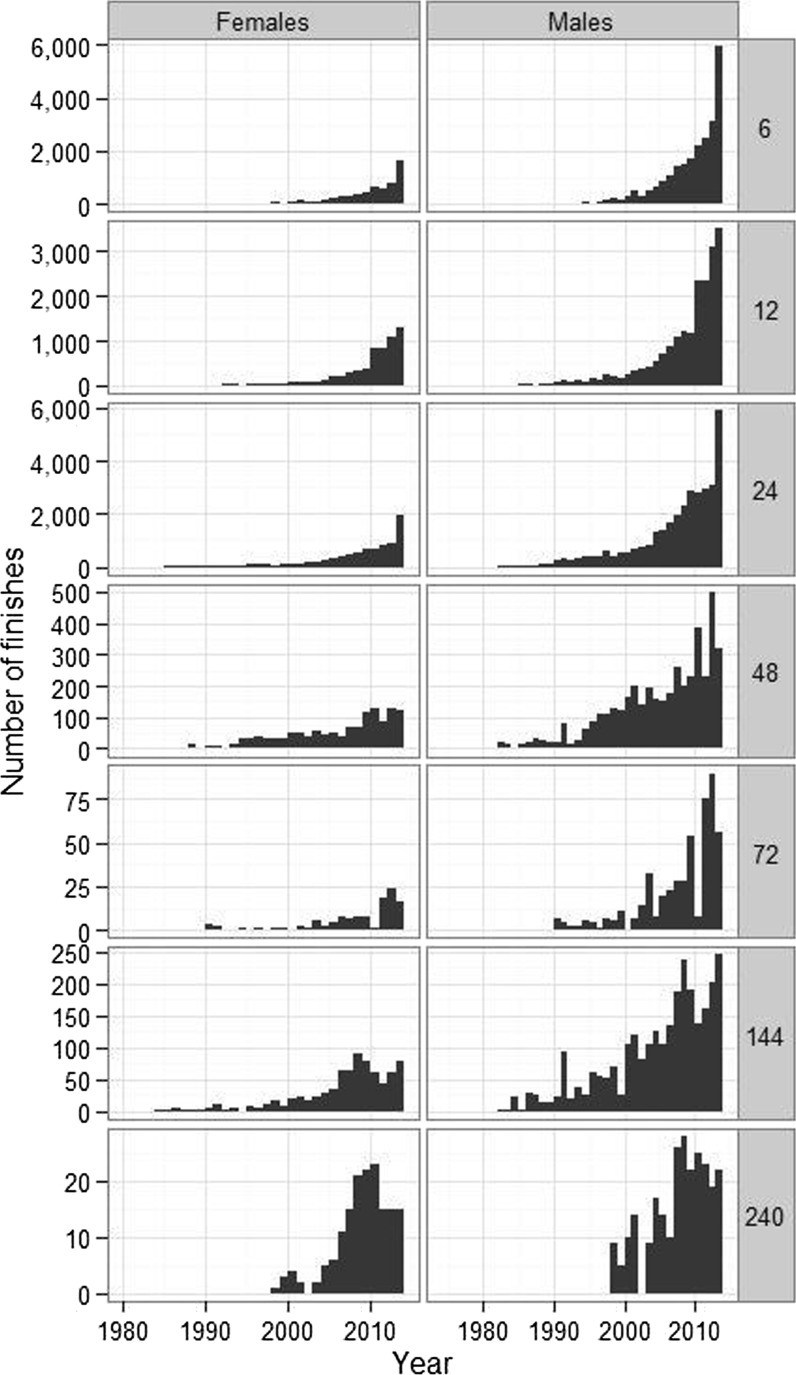

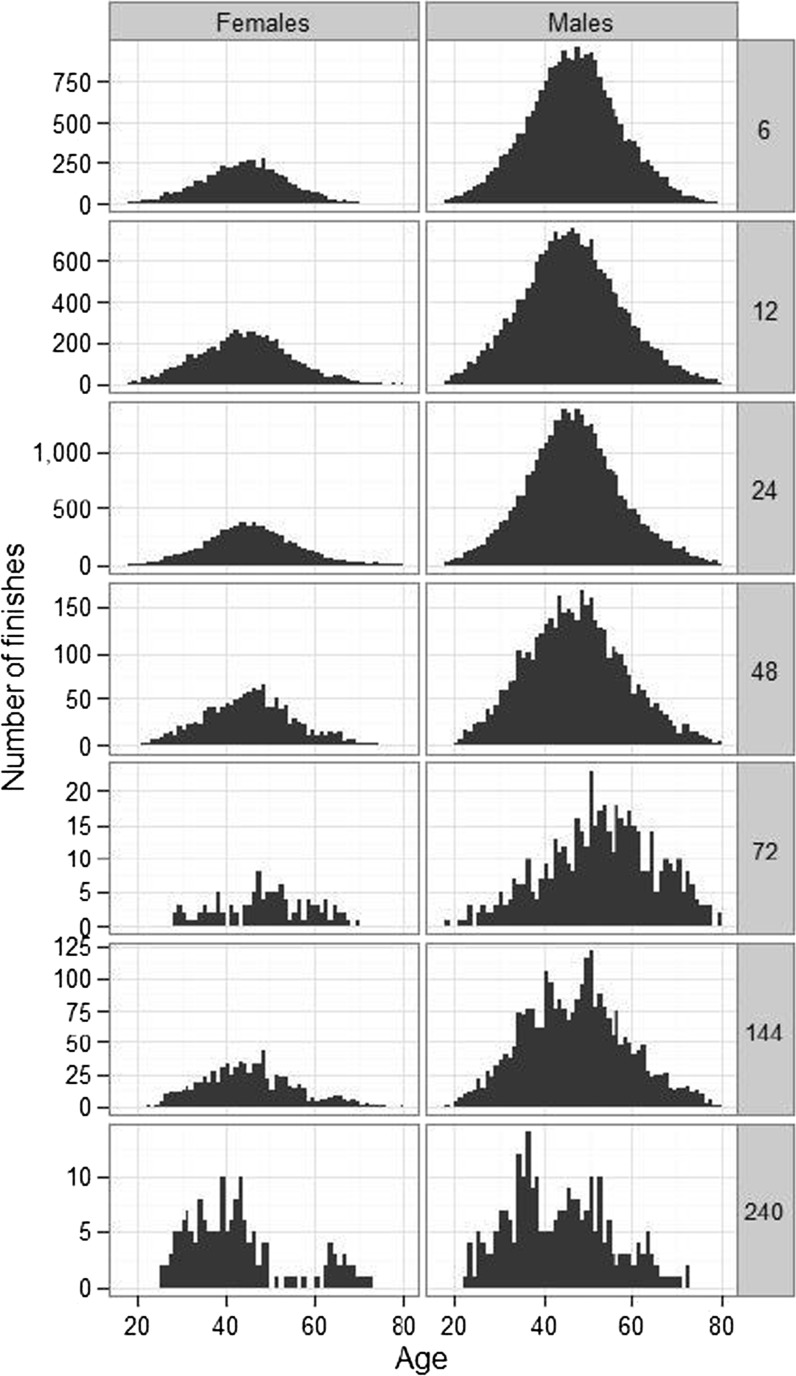

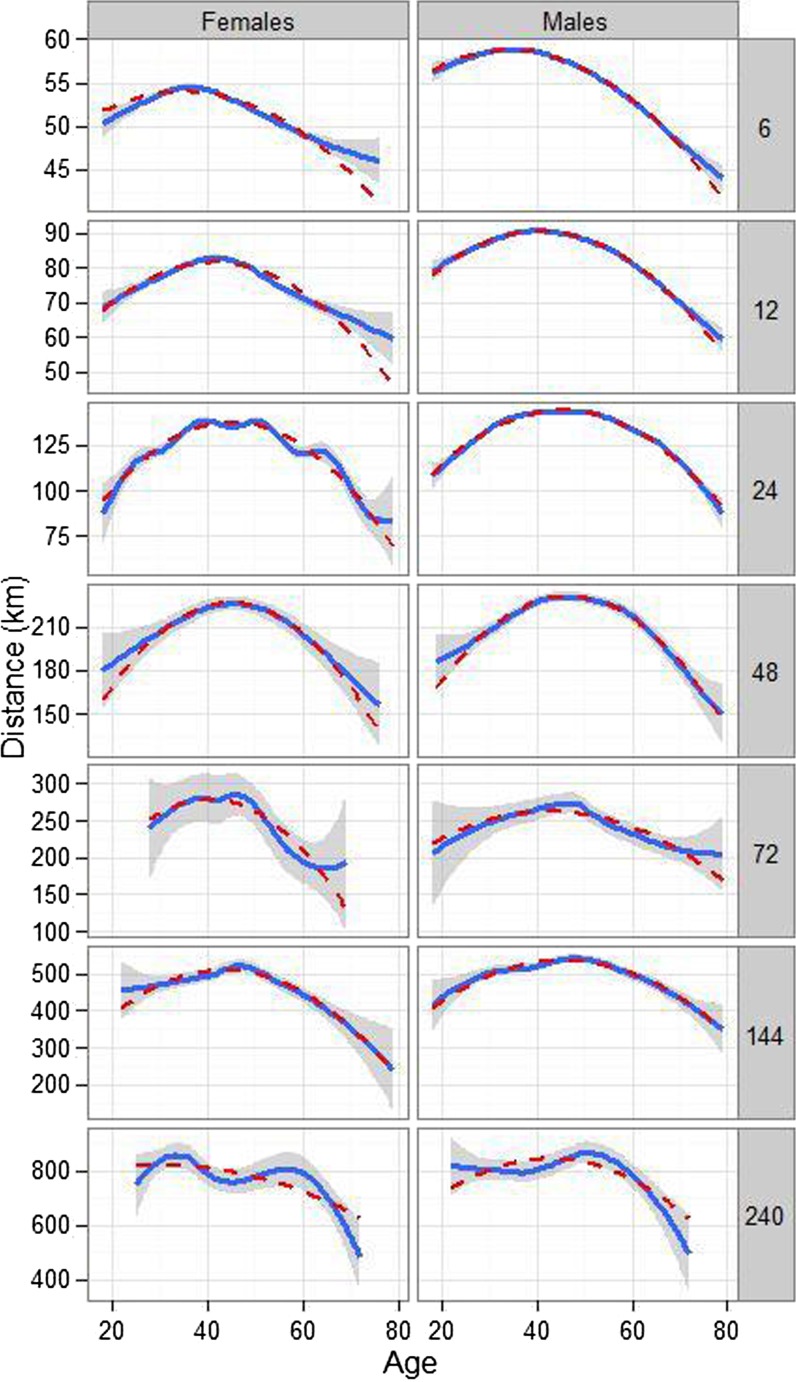

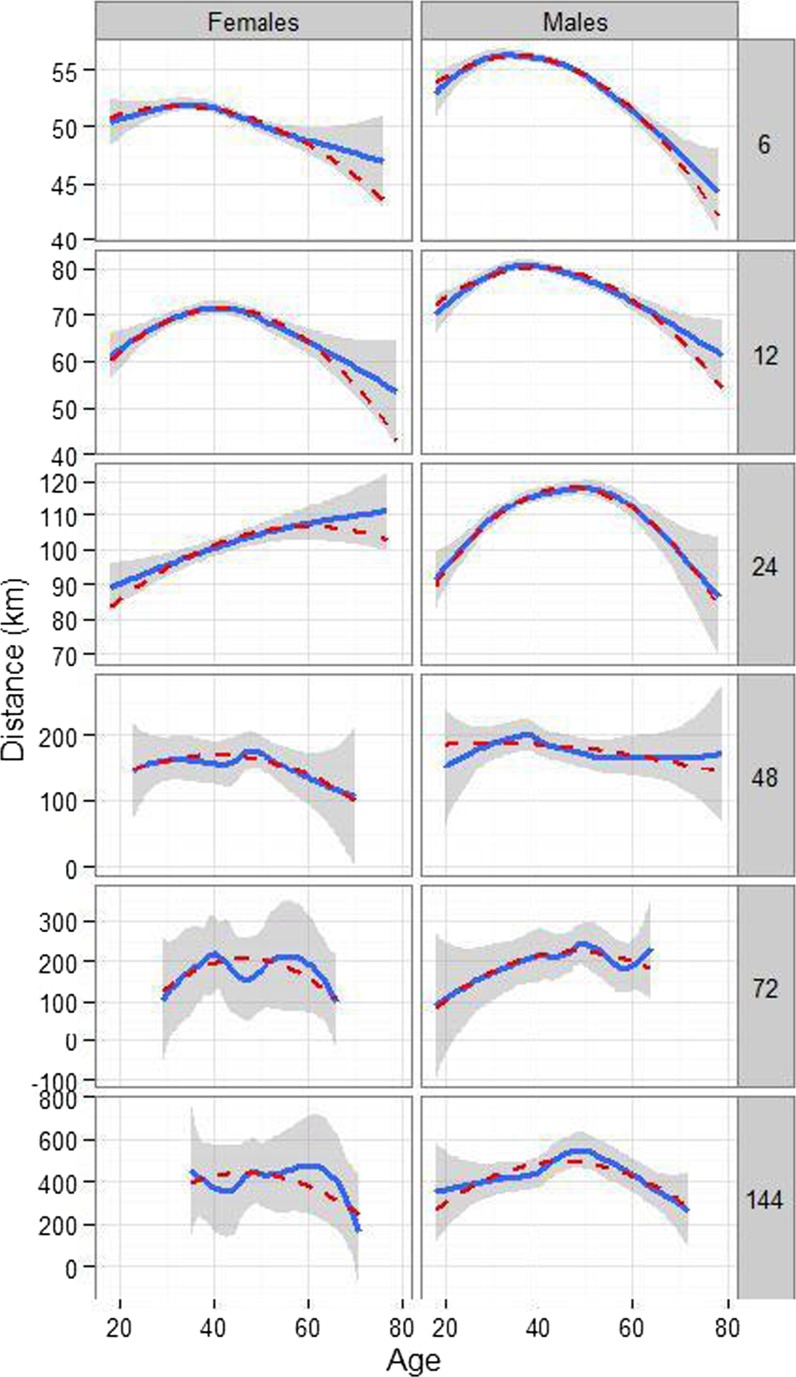

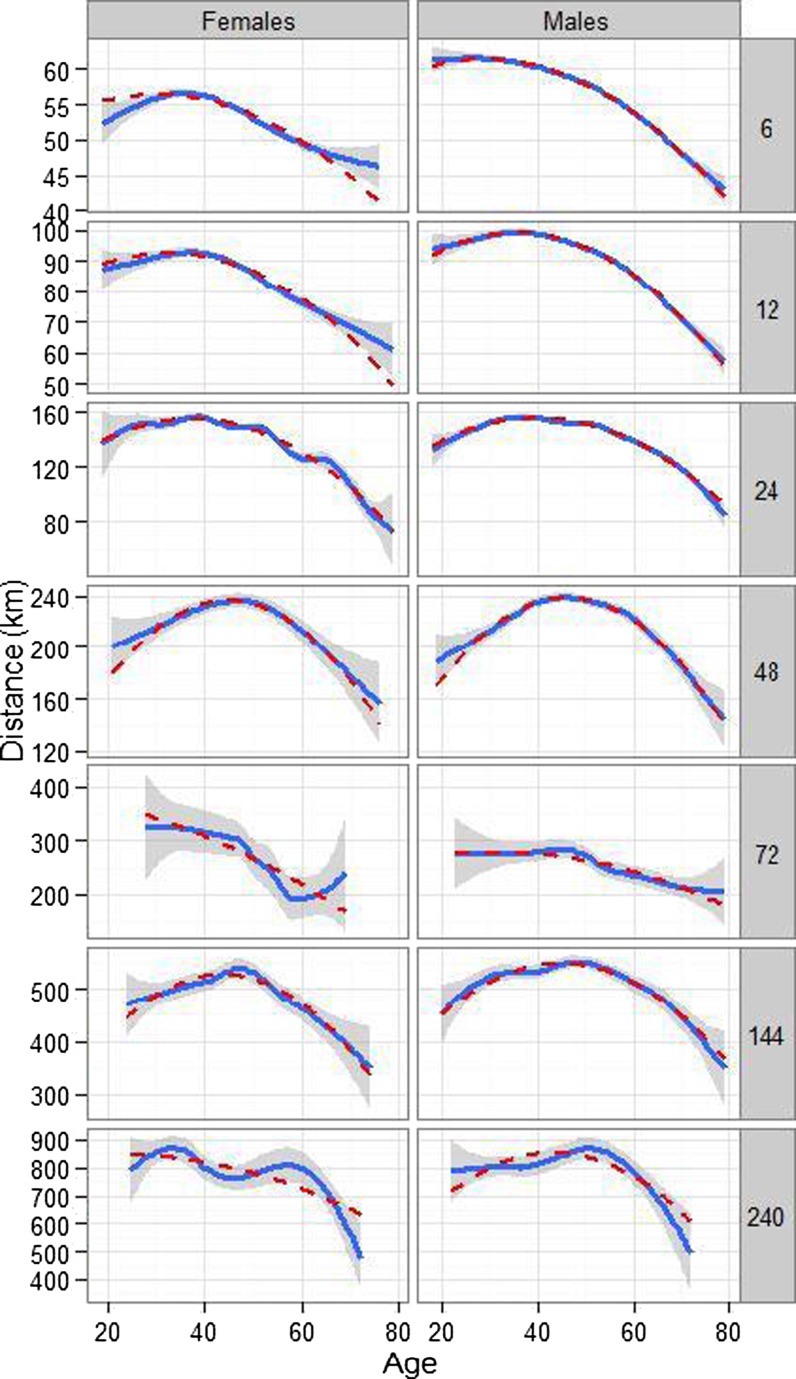

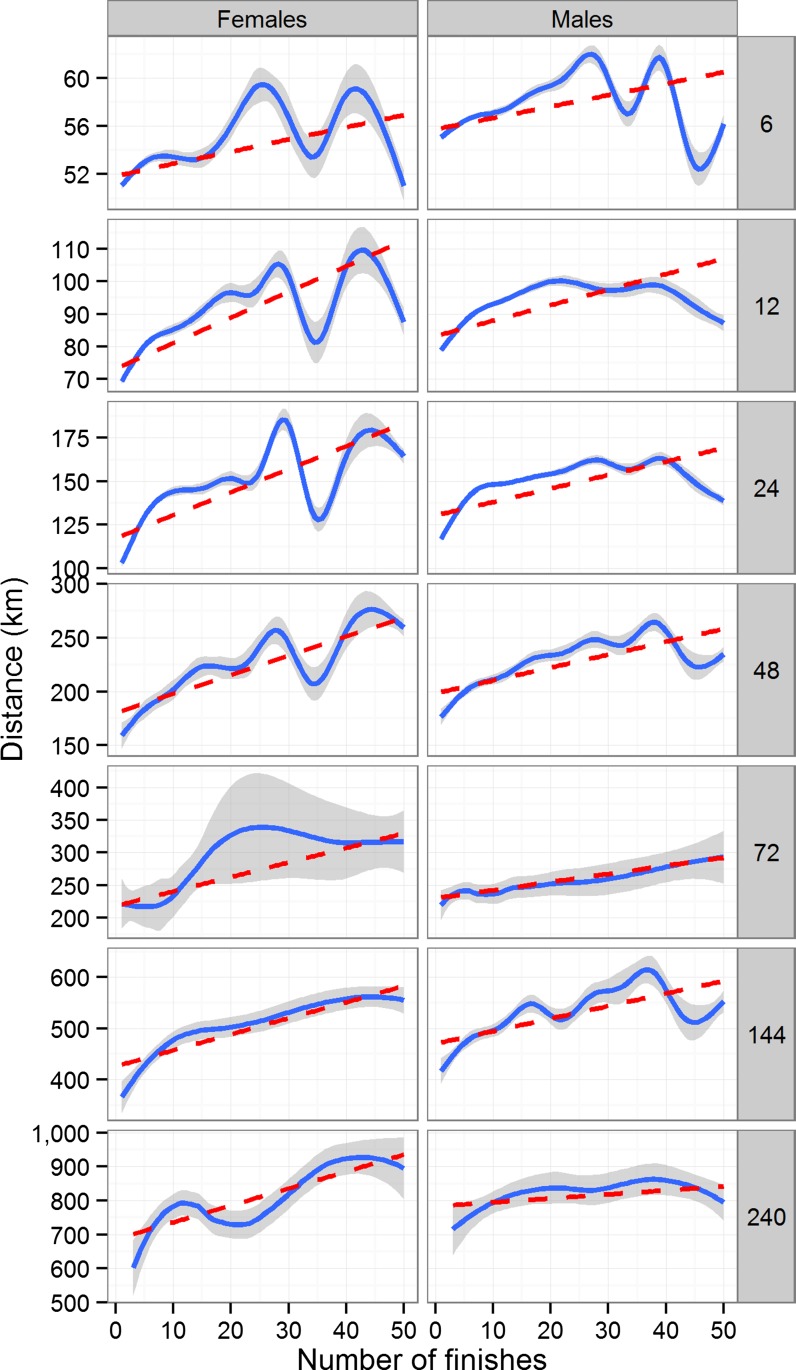

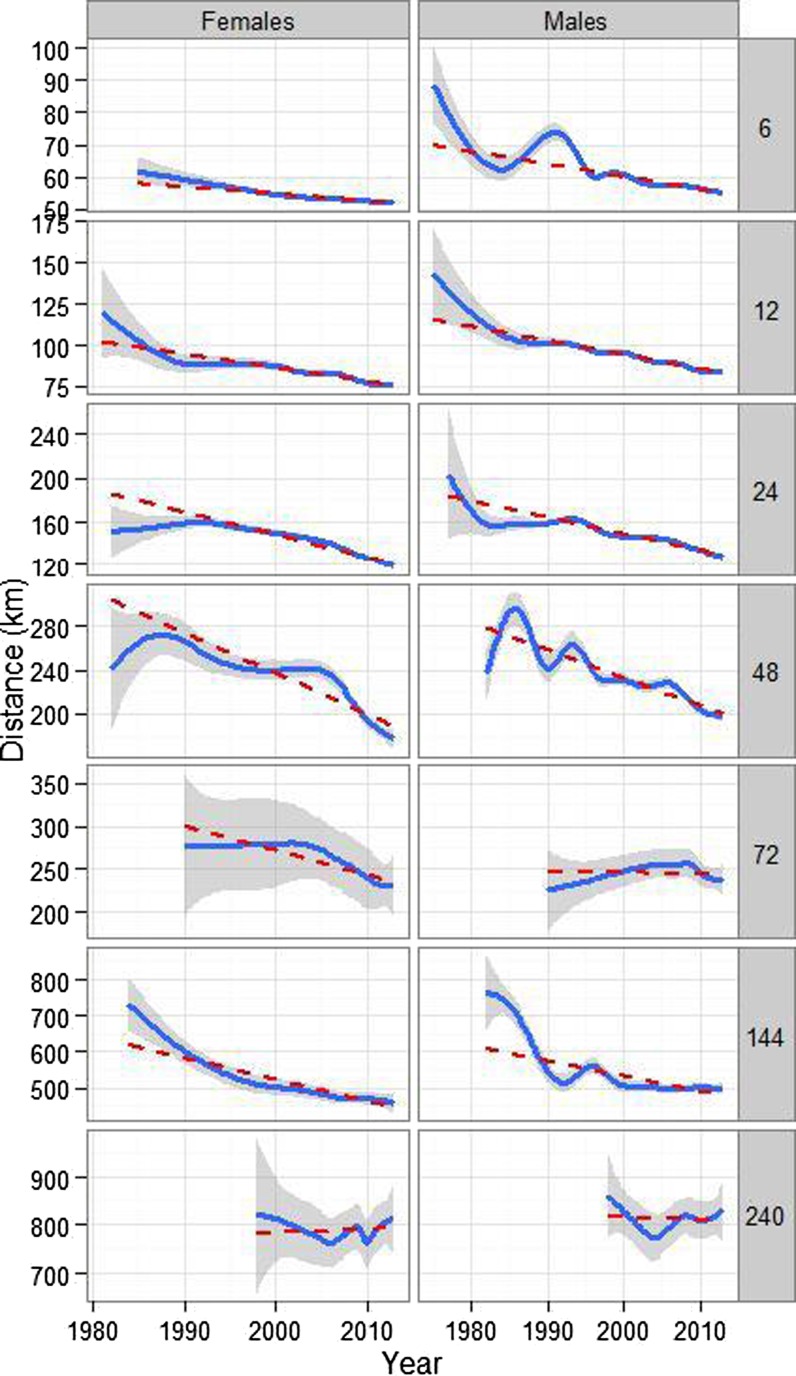

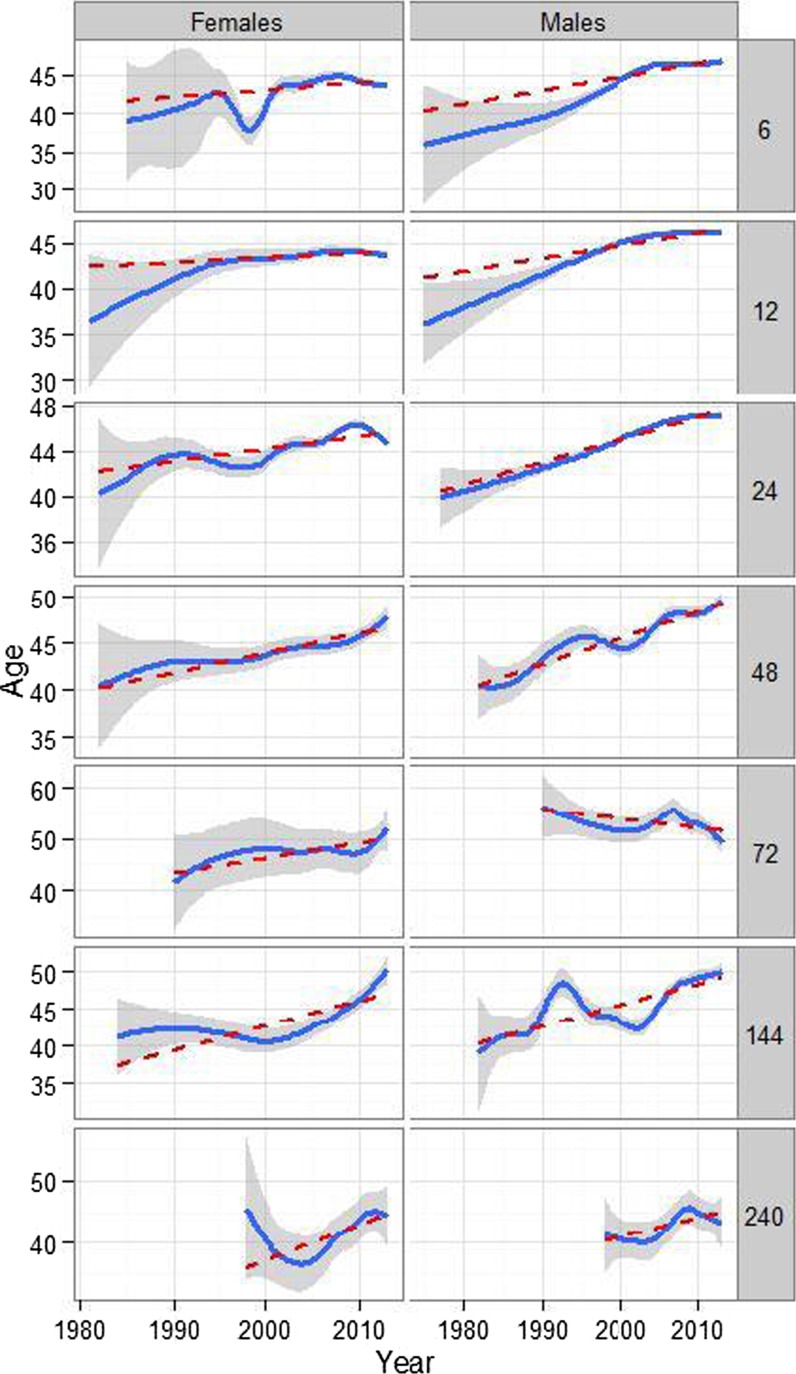

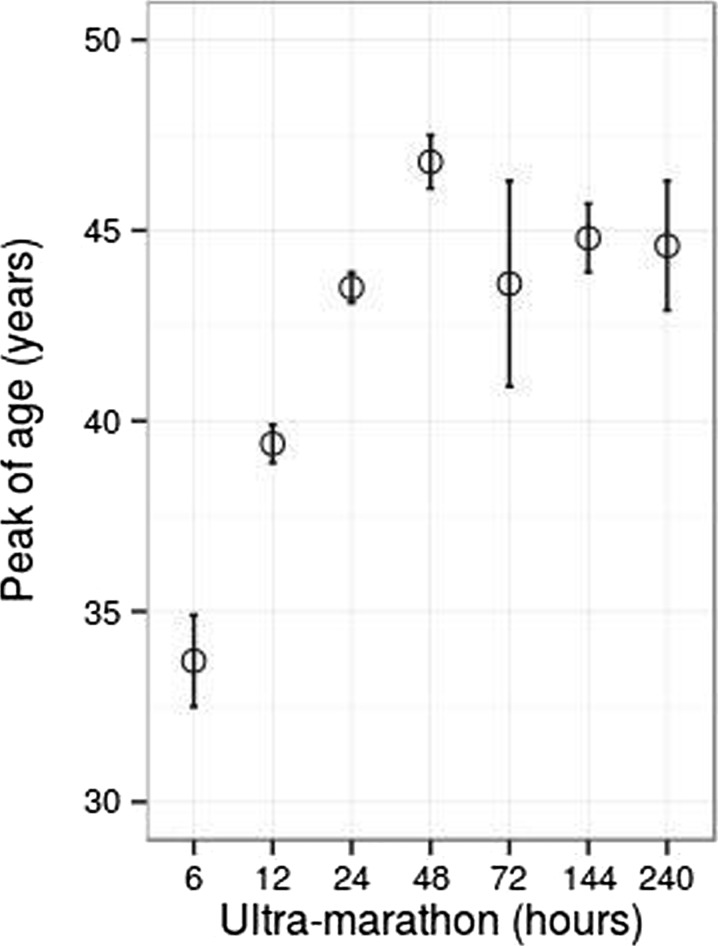

Data from 107,182 finishes of 35,134 individual finishers were available. In some cases, sex of the athlete was uncertain and they had to be excluded for data analysis. Finally, 107,045 finishes of 35,120 individual finishers were considered for the graphical analysis (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9) and 97,126 finishes of 31,588 for the regression model. Women accounted for 21.4 % before applying cut-off and 20.8 % of the finishes after applying cut-off (Table 2). For both women and men, the number of finishes increased across years for all races (Fig. 1). About half of the finishers completed one ultra-marathon and the other half completed more than one race during their active period as a runner (Table 3). Most of the finishes were achieved in the fourth decade (Fig. 2). The age of the best performance increased with increasing race duration (Fig. 3), also when only one successful finish (Fig. 4) and at least five successful finishes (Fig. 5) were considered. The regression analysis shows a difference in performance between man and women and interaction effects between age and race performance (Table 4). There were no interaction effects between sex, age and ultra-marathon. Figure 10 shows the observed and the fitted distances against age and UM. The model does fit the data quite well with some deviation in 72 h. The peak of ages are 33.7 years (95 % CI 32.5–34.9 years), 39.4 years (95 % CI 38.9–39.9 years), 43.5 years (95 % CI 43.1–43.9 years), 46.8 years (95 % CI 46.1–47.5 years), 43.6 years (95 % CI 40.9–46.3 years), 44.8 years (95 % CI 43.9–45.7 years) and 44.6 years (95 % CI 42.9–46.3 years) for 6, 12, 24, 72, 144 and 240 h, respectively (Fig. 11). The peak of age increased from 33.7 years in 6 h to the maximum of 46.8 years in 48 h (p < 0.001 for each pair comparison). The peak of age in 72 h was 3.2 years lower than in 48 h (p = 0.012) and the peak in 144 and 240 h differed not from the peak in 72 h (p > 0.05). With increasing number of finishes, the athletes were able to improve their ultra-marathon performance (Table 4). Across years, the performance decreased and the age of peak ultra-marathon performance increased (Table 4). The age of peak ultra-marathon performance increased with increasing number of finishes (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Histogram of calendar year

Fig. 2.

Histogram of age

Fig. 3.

Distance against age. Solid line smooth function (loess or gam), dashed line quadratic function. The grey region is the 95 % confidence interval

Fig. 4.

Distance against age, only finishers with one finish. Solid line smooth function (loess or gam), dashed line quadratic function. The grey region is the 95 % confidence interval

Fig. 5.

Distance against age, finishers with at least five finishes. Solid line smooth function (loess or gam), dashed line quadratic function. The grey region is the 95 % confidence interval

Fig. 6.

Distance against number of finishes (i.e. experience). Solid line smooth function (loess or gam), dashed line linear function. The grey region is the 95 % confidence interval

Fig. 7.

Distance against calendar year. Solid line smooth function (loess or gam), dashed line linear function. The grey region is the 95 % confidence interval

Fig. 8.

Age against calendar year. Solid line smooth function (loess or gam), dashed line linear function. The grey region is the 95 % confidence interval

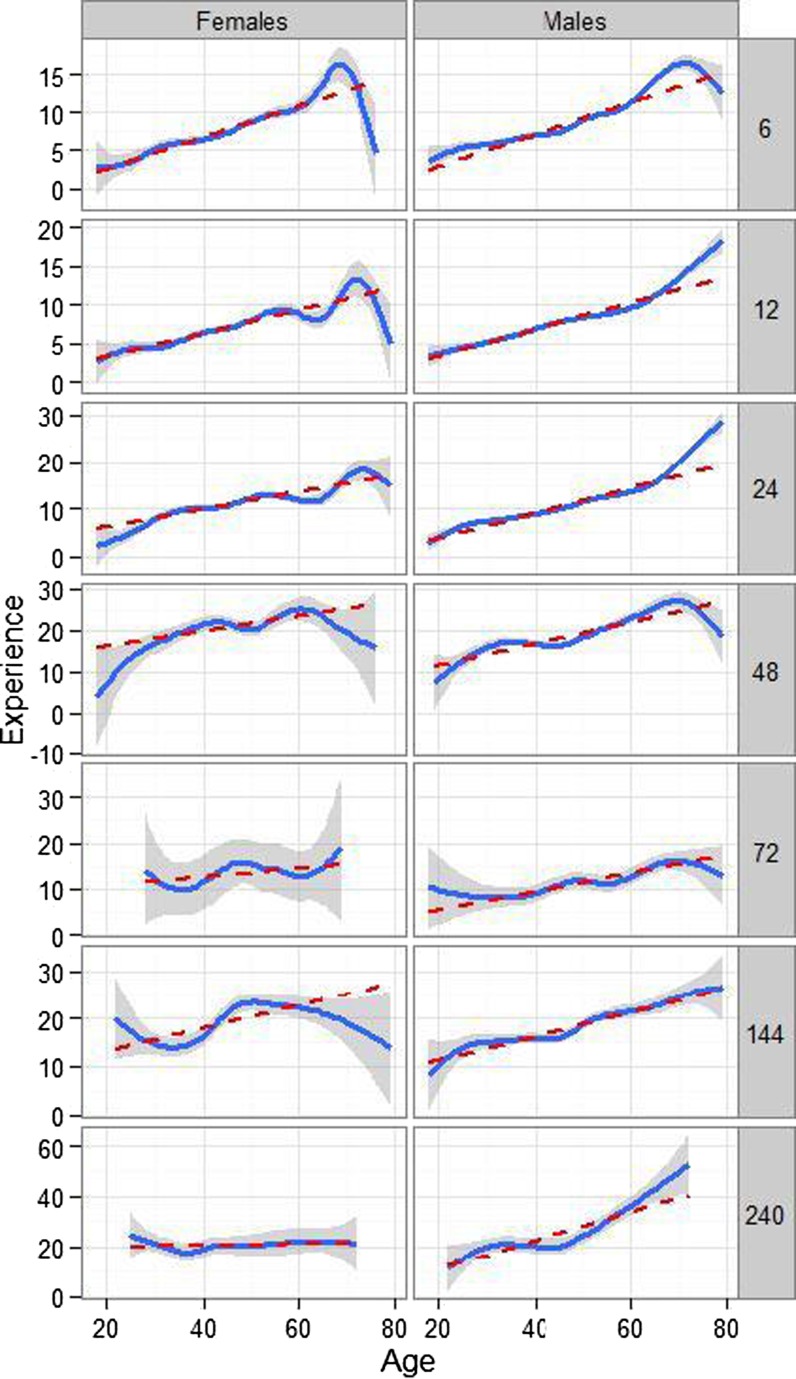

Fig. 9.

Number of finishes (i.e. experience) against age. Solid line smooth function (loess or gam), dashed line linear function. The grey region is the 95 % confidence interval

Table 3.

Distributions of number of finishes per participant

| Number of finishes | Finishers | |

|---|---|---|

| Numbers | Proportion (%) | |

| 1 | 17,999 | 51.3 |

| 2 | 6414 | 18.3 |

| 3 | 3191 | 9.1 |

| 4 | 1915 | 5.5 |

| 5 | 1233 | 3.5 |

| 6 | 869 | 2.5 |

| ≥7 | 3499 | 10.0 |

| Total finishers | 35,120 | 100.0 |

Table 4.

Coefficients and standard errors from a multivariable regression model: ln (distance in km) = UM × Age + UM × Age2 + UM × Sex + Calendar year + Calendar year + with a random intercept for each finisher

| Coefficient | Standard error | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 17.6 | 0.31 | <0.001 |

| Ultra-marathon (UM) | |||

| UM-12 | 0.47 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| UM-24 | 0.99 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| UM-48 | 1.41 | 0.006 | <0.001 |

| UM-72 | 1.68 | 0.018 | <0.001 |

| UM-124 | 2.30 | 0.008 | <0.001 |

| UM-240 | 2.80 | 0.016 | <0.001 |

| Age | |||

| Linear | −0.0037 | 0.00013 | <0.001 |

| Squared | −0.00015 | 0.00001 | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 0.0872 | 0.0034 | <0.001 |

| Calendar year of race | −0.0068 | 0.0002 | <0.001 |

| Experience | 0.0055 | 0.0002 | <0.001 |

| Interaction UM and Age, linear | |||

| (UM-12) × Age | 0.00074 | 0.00016 | <0.001 |

| (UM-24) × Age | 0.00261 | 0.00015 | <0.001 |

| (UM-48) × Age | 0.00423 | 0.00026 | <0.001 |

| (UM-72) × Age | 0.00231 | 0.00077 | 0.003 |

| (UM-144) × Age | 0.00306 | 0.00031 | <0.001 |

| (UM-240) × Age | 0.00268 | 0.00072 | <0.001 |

| Interaction UM and Age, squared | |||

| (UM-12) × Age2 | −0.000076 | 0.000011 | <0.001 |

| (UM-24) × Age2 | −0.000081 | 0.000011 | <0.001 |

| (UM-48) × Age2 | −0.000133 | 0.000018 | <0.001 |

| (UM-72) × Age2 | −0.000147 | 0.000043 | <0.001 |

| (UM-144) × Age2 | −0.000131 | 0.000021 | <0.001 |

| (UM-240) × Age2 | −0.000234 | 0.000055 | <0.001 |

| Interaction UM and Sex | |||

| (UM-12) × Sex (male) | −0.0007 | 0.0040 | 0.870 |

| (UM-24) × Sex (male) | −0.0484 | 0.0039 | <0.001 |

| (UM-48) × Sex (male) | −0.0611 | 0.0066 | <0.001 |

| (UM-72) × Sex (male) | −0.0478 | 0.0201 | 0.017 |

| (UM-144) × Sex (male) | −0.0569 | 0.0082 | <0.001 |

| (UM-240) × Sex (male) | −0.0832 | 0.0172 | <0.001 |

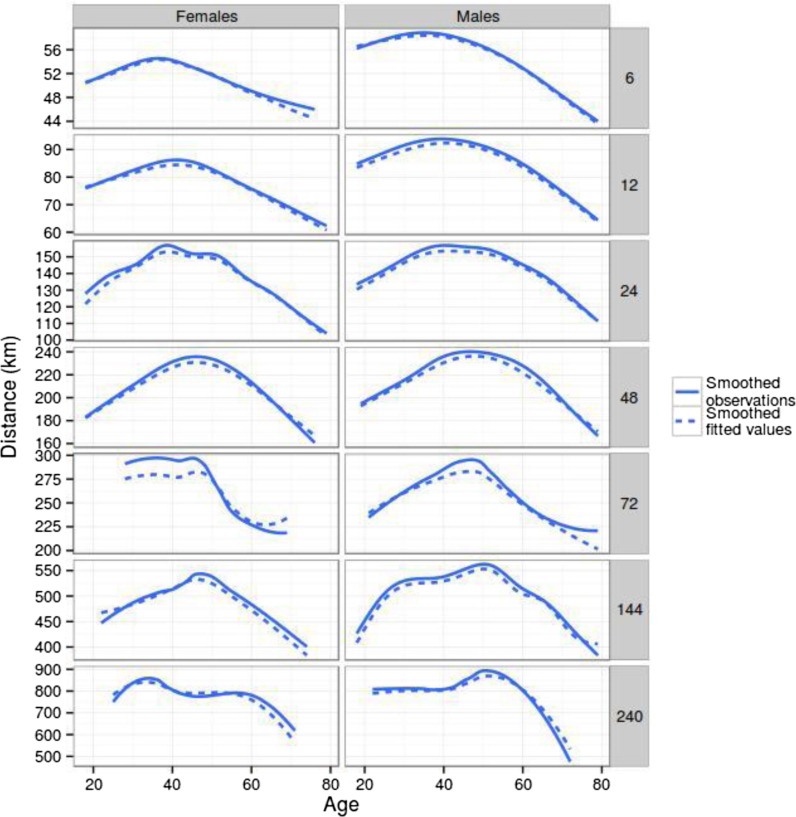

Fig. 10.

Distance against age. Solid line smoothed observed data as in Fig. 3 (loess or gam), dashed line smoothed fitted data from regression model (1) (loess or gam)

Fig. 11.

Peak of ages with 95 % confidence intervals

Discussion

This study intended to determine the age of peak ultra-marathon performance in time-limited races held from 6 to 240 h (10 days) and it was hypothesized that the age of peak ultra-marathon performance would increase with increasing duration of the events. The most important findings were, (i), the age of the best ultra-marathon performance increased with increasing race duration and with increasing number of finishes, (ii), the ultra-marathon performance decreased and the age of peak ultra-marathon performance increased across years, and (iii), the ultra-marathon performance improved with increasing number of finishes.

Increase in finishes and finishers

For all races, the number of finishes and finishers increased across years. This trend of an increase in participation in ultra-marathons has been reported by Hoffman and Wegelin (2009) for a single 161-km ultra-marathon and by Hoffman et al. (2010) for all 161-km ultra-marathons held in Northern America. An important finding in the present study considering different time-limited ultra-marathons was that most of the finishes and finishers were recorded for races held in 24 h, but not for the shorter or longer durations. A recent study investigating participation and performance trends for one event offering both a 12- and a 24-h race showed that 78.5 % of all participants competed in the 24-h race but only 21.5 % in the 12-h race (Teutsch et al. 2013). Motivational factors might be a potential explanation to compete in a 24-h race rather than in a 12 h race (Schüler et al. 2014). For female ultra-marathoners, the task orientation (i.e. finishing an ultra-marathon or accomplishing various goals) was more important than ego orientation (i.e. placing in the top three overall or beating the concurrent) (Krouse et al. 2011).

The age of the best performance increased with increasing race duration

The hypothesis of this study was that the age of peak ultra-marathon performance would increase with the duration of the event. Indeed, we can fully confirm that the age of the best ultra-marathon performance increased with increasing race duration also when only one successful finish or when at least five successful finishes were considered. The lowest age of peak performance was 33.7 years for 6 h, and the highest age was 46.8 years for 48 h.

It is a common finding that successful ultra-marathoners are older than 35 years (Hoffman 2010; Hoffman and Wegelin 2009; Hoffman and Krishnan 2013; Knechtle 2012). Wegelin and Hoffman (2011) showed that especially women performed better than men above the age of 38 years. Additionally, ultra-marathoners seemed to be well-educated middle-aged men since most of the successful 161-km ultra-marathoners have a high education. Hoffman and Fogard (2012) reported that 43.6 % of 161-km ultra-marathoners had a bachelor degree and 37.2 % and graduate degree. The increase in the age of peak ultra-marathon performance with increasing length of the races is most likely due with the experience of the athletes (Hoffman and Parise 2014).

The age of the best performance increased and performance improved with increasing number of finishes

An important finding was that these ultra-marathoners were able to improve their performance with increasing number of finishes and these athletes improved performance although they became older. Similar findings have been reported for 161-km ultra-marathoners (Hoffman and Parise 2014). The number of finishes was inversely associated with finish times for women, men and top performing men. A tenth or higher finish was 1.3, 1.7 and almost 3 h faster than a first finish for men, women and top performing men, respectively (Hoffman and Parise 2014).

The aspect of previous experience might be the most likely reason to explain the dominance of master runners in ultra-distance races (Knechtle 2012). In 161-km ultra-marathoners held in North America between 1977 and 2008, the number of annually completed races by an individual athlete increased across years (Hoffman et al. 2010). Successful ultra-marathoners generally train for 7 years before competing in the first ultra-marathon (Hoffman and Krishnan 2013) and have about 7 years of experience in ultra-marathon running (Knechtle 2012). Active ultra-marathoners train for around 3,300 km/year where the annual running distance is related to age and the longest ultra-marathon held within that year (Hoffman and Krishnan 2013).

Previous experience (e.g. number of completed races, personal best times) has been reported as an important predictor variable in different ultra-endurance disciplines such as running (Knechtle et al. 2011b), cycling (Knechtle et al. 2011c), triathlon (Herbst et al. 2011; Knechtle et al. 2011d) and inline skating (Knechtle et al. 2012d). In 24-h ultra-marathoners, the longest training session before the race and the personal best marathon time had the best correlation with race performance (Knechtle et al. 2011b). In the mountain bike ultra-cycling race “Swiss Bike Masters” covering a distance of 120 km and an altitude of around 5,000 m, the personal best time in the race, the total annual cycling kilometers and the annual training kilometers in road cycling were related to race time (Knechtle et al. 2011c). In successful finishers in a Triple Iron ultra-triathlon, the personal best time in an Ironman triathlon and a Triple Iron triathlon were positively and highly significantly related to total race time (Knechtle et al. 2011d). In a Deca Iron ultra-triathlon, race time was related to both the number of finished Triple Iron triathlons and the personal best time in a Triple Iron triathlon (Herbst et al. 2011). Also for triathlon distances longer than the Deca Iron ultra-triathlon, previous experience seemed important for a successful outcome (Knechtle et al. 2014a, b). In the longest inline marathon in Europe (111 km), the “Inline One-Eleven” in Switzerland, age, duration per training unit and personal best time were the only three variables related to race time (Knechtle et al. 2012d). The authors assumed that improving performance in a long-distance inline skating race might be related to a high training volume and previous race experience (Knechtle et al. 2012d). Overall, previous experience seems to be the most important predictor for a successful outcome in ultra-endurance performance.

The age of peak performance increased and performance decreased across years

An important finding was that the age of peak ultra-marathon performance increased and ultra-marathon performance decreased across years. Indeed, these athletes became slower with increasing age. Similar findings have been reported for 161-km ultra-marathoners (Hoffman and Parise 2014). Men and women up to the age of 38 years slowed 0.05–0.06 h/year with advancing age. Men slowed 0.17 h/year from 38 years through 50 years, and 0.23 h/year after the age of 50 years. Women slowed 0.20–0.23 h/year with advancing age starting from 38 years. Top performing men younger than 38 years did not slow with increasing age but slowed by 0.26 and 0.39 h/year from 38 through 50 years and after 50 years, respectively (Hoffman and Parise 2014). The decrease in performance is most likely due to the increase in the age of peak ultra-marathon performance over time. However, also, an increase in the number of novice ultra-marathoners might explain the decrease.

Factors contributing to the age-related decline in endurance performance in master athletes are central factors such as maximum heart rate, maximum stroke volume, maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max), blood volume and peripheral factors such as skeletal muscle mass, muscle fibre composition, fibre size, fibre capillarization and muscle enzyme activity (Reaburn and Dascombe 2008). The decline in endurance performance appears primarily to be due to an age-related decrease in VO2max (Reaburn and Dascombe 2008). Additionally, an age-related decrease in active skeletal muscle mass occurs and contributes to a decrease in endurance performance (Reaburn and Dascombe 2008).

The main reason for the age-related decline in endurance performance is most likely the decrease in VO2max (Hawkins and Wiswell 2003) due to a loss of skeletal muscle mass (Trappe et al. 1996). With ageing, skeletal muscle atrophy in humans appears to be inevitable. A gradual loss of muscle fibres starts at the age of ∼50 years and continues to the age of ∼80 years where ∼50 % of the fibres are lost from the limb muscles (Faulkner et al. 2007). The degree of atrophy of the muscle fibres is largely dependent on the habitual level of physical activity of the individual (Faulkner et al. 2007). However, for both marathoners and ultra-marathoners, age was significantly and negatively related to skeletal muscle mass and significantly and positively to percentage of body fat for master runners (>35 years) and percentage of body fat, not skeletal muscle mass, was related to running times for master runners in both marathoners and ultra-marathoners (Knechtle et al. 2012c).

However, the limiting factor in VO2max and endurance performance at any age in well-trained individuals is almost certainly cardiac output (Proctor and Joyner 1985). The reduced VO2max in highly trained older men and women relative to their younger counterparts is due, in part, to a reduced aerobic capacity per kilogram of active muscle independent of age-associated changes in body composition, i.e., replacement of muscle tissue by fat. Because skeletal muscle adaptations to endurance training can be well maintained in older subjects, the reduced aerobic capacity per kilogram of muscle likely results from age-associated reductions in maximal O2 delivery (i.e. cardiac output and/or muscle blood flow) (Proctor and Joyner 1985).

Ultra-marathon performance is also related to training characteristics such as training volume (Hoffman and Fogard 2011; Knechtle et al. 2010, 2011a) and anthropometric characteristics such as body mass index (Hoffman and Fogard 2011). In the present analysis, however, these aspects were not included.

The finding that these ultra-marathoners became slower while getting older is in contrast to recent findings for triathletes competing in “Ironman Hawaii” (Gallmann et al. 2014). The annual ten fastest finishers competing in “Ironman Hawaii” between 1983 and 2012 became faster and older (Gallmann et al. 2014). However, this trend could be confirmed in long-distance triathletes competing in “Ultraman Hawaii” where the annual top three women and men improved their performance during the 1983–2012 period although the age of the annual top three women and men increased (Meili et al. 2013). The most likely explanation for these discrepancies is the selection of the sample. While for the triathletes the annual ten fastest women and men were selected, the present study included all annual finishers.

Strength, weakness, limitations, implications for future research and practical applications

The strength of this study is the long period of time and the large data set. However, some races might not be listed in the data base. This study is limited since aspects such as training (Knechtle et al. 2010) and anthropometry (Knechtle et al. 2011b) of the athletes were not considered. Future studies need to investigate the change in performance in age group ultra-marathoners over time. With these findings, athletes and coaches can now better plan their ultra-marathon career in order to find the best point in time to switch to the next longer race in order to compete among the best athletes in the field and to achieve the best performance.

Conclusion

The present findings show that in ultra-marathoners competing in time-limited races from 6 to 240 h during the 1975–2013 period, the age of peak performance increased and performance declined. The age of peak ultra-marathon performance increased with increasing race duration and with increasing number of finishes. These athletes improved race performance with increasing number of finishes.

References

- Cejka N, Rüst CA, Lepers R, Onywera V, Rosemann T, Knechtle B (2013) Participation and performance trends in 100-km ultra-marathons worldwide. J Sports Sci 2013 Sep 9. doi:10.1080/02640414.2013.825729 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cejka N, Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R (2014) Performance and age of the fastest female and male 100-km ultra-marathoners worldwide from 1960 to 2012. J Strength Cond Res. 2014 Jan 28. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000370 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Da Fonseca-Engelhardt K, Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Knechtle P, Lepers R, Rosemann T. Participation and performance trends in ultra-endurance running races under extreme conditions—‘Spartathlon’ versus ‘Badwater’. Extrem Physiol Med. 2013;2:15. doi: 10.1186/2046-7648-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenberger E, Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R, Senn O. Sex difference in open-water ultra-swim performance in the longest freshwater lake swim in Europe. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27:1362–1369. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318265a3e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner JA, Larkin LM, Claflin DR, Brooks SV. Age-related changes in the structure and function of skeletal muscles. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:1091–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallmann D, Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R. Elite triathletes in ‘Ironman Hawaii’ get older but faster. Age (Dordr) 2014;36:407–416. doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9534-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins S, Wiswell R. Rate and mechanism of maximal oxygen consumption decline with aging: implications for exercise training. Sports Med. 2003;33:877–888. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333120-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst L, Knechtle B, Lopez CL, Andonie JL, Fraire OS, Kohler G, Rüst CA, Rosemann T. Pacing strategy and change in body composition during a Deca Iron Triathlon. Chin J Physiol. 2011;54:255–263. doi: 10.4077/CJP.2011.AMM115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman MD. Performance trends in 161-km ultramarathons. Int J Sports Med. 2010;31:31–37. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1239561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman MD, Fogard K. Factors related to successful completion of a 161-km ultramarathon. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2011;6:25–37. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.6.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman MD, Fogard K. Demographic characteristics of 161-km ultramarathon runners. Res Sports Med. 2012;20:59–69. doi: 10.1080/15438627.2012.634707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman MD, Krishnan E. Exercise behavior of ultramarathon runners: baseline findings from the ULTRA Study. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27:2939–2945. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182a1f261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman MD, Parise CA. Longitudinal assessment of age and experience on performance in 161-km ultramarathons. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2014 doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2013-0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman MD, Wegelin JA. The Western States 100-mile endurance run: participation and performance trends. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:2191–2918. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a8d553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman MD, Ong JC, Wang G. Historical analysis of participation in 161 km ultramarathons in North America. Int J Hist Sport. 2010;27:1877–1891. doi: 10.1080/09523367.2010.494385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter SK, Stevens AA, Magennis K, Skelton KW, Fauth M. Is there a sex difference in the age of elite marathon runners? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:656–664. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181fb4e00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B. Ultramarathon runners: nature or nurture? Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2012;7:310–312. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.7.4.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Wirth A, Knechtle P, Zimmermann K, Kohler G. Personal best marathon performance is associated with performance in a 24-h run and not anthropometry or training volume. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:836–839. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.045716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Rosemann T, Lepers R. Predictor variables for a 100-km race time in male ultra-marathoners. Percept Mot Skills. 2010;111:681–693. doi: 10.2466/05.25.PMS.111.6.681-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Rosemann T, Senn O. What is associated with race performance in male 100-km ultra-marathoners—anthropometry, training or marathon best time? J Sports Sci. 2011;29:571–577. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2010.541272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Rosemann T, Lepers R. Personal best marathon time and longest training run, not anthropometry, predict performance in recreational 24-hour ultrarunners. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25:2212–2218. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181f6b0c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Rosemann T, Senn O. Personal best time and training volume, not anthropometry, is related to race performance in the ‘Swiss Bike Masters’ mountain bike ultramarathon. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25:1312–1317. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181d85ac4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Rosemann T, Senn O. Personal best time, not anthropometry or training volume, is associated with total race time in a triple iron triathlon. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25:1142–1150. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181d09f0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R. Age-related changes in 100-km ultra-marathon running performance. Age (Dordr) 2012;34:1033–1045. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9290-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Knechtle P, Rosemann T, Lepers R. Age-related changes in ultra-triathlon performances. Extrem Physiol Med. 2012;1:5. doi: 10.1186/2046-7648-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Knechtle P, Rosemann T. Does muscle mass affect running times in male long-distance master runners? Asian J Sports Med. 2012;3:247–256. doi: 10.5812/asjsm.34547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R. Age, training, and previous experience predict race performance in long-distance inline skaters, not anthropometry. Percept Mot Skills. 2012;114:141–156. doi: 10.2466/05.PMS.114.1.141-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Martin N. 33 Ironman triathlons in 33 days-a case study. Springerplus. 2014;3:269. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Rosemann T, Lepers R, Rüst CA. A comparison of performance of deca iron and triple deca iron ultra-triathletes. SpringerPlus. 2014;3:461. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouse RZ, Ransdell LB, Lucas SM, Pritchard ME. Motivation, goal orientation, coaching, and training habits of women ultrarunners. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25:2835–2842. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318204caa0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepers R, Cattagni T. Do older athletes reach limits in their performance during marathon running? Age (Dordr) 2012;34:773–781. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9271-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meili D, Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R. Participation and performance trends in ‘Ultraman Hawaii’ from 1983 to 2012. Extrem Physiol Med. 2013;2:25. doi: 10.1186/2046-7648-2-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor DN, Joyner MJ. Skeletal muscle mass and the reduction of VO2max in trained older subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1985;82:1411–1415. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.5.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaburn P, Dascombe B. Endurance performance in masters athletes. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 2008;5:31–42. doi: 10.1007/s11556-008-0029-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rüst CA, Knechtle B, Rosemann T, Lepers R. Analysis of performance and age of the fastest 100-mile ultra-marathoners worldwide. Clin (Sao Paulo) 2013;68:605–611. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(05)05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüst CA, Knechtle B, Rosemann T, Lepers R. The changes in age of peak swim speed for elite male and female Swiss freestyle swimmers between 1994 and 2012. J Sports Sci. 2014;32:248–358. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2013.823221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüler J, Wegner M, Knechtle B. Implicit motives and basic need satisfaction in extreme endurance sports. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2014;36:300. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2013-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiefel M, Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R. The age of peak performance in Ironman triathlon: a cross-sectional and longitudinal data analysis. Extrem Physiol Med. 2013;2:27. doi: 10.1186/2046-7648-2-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teutsch A, Rüst CA, Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Rosemann T, Lepers R. Differences in age and performance in 12-hour and 24-hour ultra-runners. Adapt Med. 2013;5:138–146. doi: 10.4247/AM.2013.ABD060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trappe SW, Costill DL, Vukovich MD, Jones J, Melham T. Aging among elite distance runners: a 22-years longitudinal study. J Appl Physiol. 1996;80:285–290. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.1.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegelin JA, Hoffman MD. Variables associated with odds of finishing and finish time in a 161-km ultramarathon. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111:145–153. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1633-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingg M, Rüst CA, Lepers R, Rosemann T, Knechtle B. Master runners dominate 24-h ultramarathons worldwide-a retrospective data analysis from 1998 to 2011. Extrem Physiol Med. 2013;2:21. doi: 10.1186/2046-7648-2-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingg MA, Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R. Analysis of participation and performance in athletes by age group in ultramarathons of more than 200 km in length. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:209–220. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S43454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]