Abstract

The role of obesity in relation to various disease processes is being increasingly studied, with reports over the last several years increasingly mentioning its association with worse outcomes in acute disease. Obesity has also gained recognition as a risk factor for severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) [1–8]. The mortality in SAP may be as high as 30% and is usually attributable to multi system organ failure (MSOF) earlier in the disease, and complications of necrotizing pancreatitis later [9–11]. To date there is no specific treatment for acute pancreatitis (AP) and the management is largely expectant and supportive. Obesity in general has also been associated with poor outcomes in sepsis and other pathological states including trauma and burns [12–14]. With the role of unsaturated fatty acids (UFA) as propagators in SAP having recently come to light [15] and with the recognition of acute lipotoxicity, there is now an opportunity to explore different strategies to reduce the mortality and morbidity in SAP and potentially other disease states associated with such a pathophysiology. In this review we will discuss the role of fat and implications of the consequent acute lipotoxicity on the outcomes of acute pancreatitis in lean and obese states and during acute on chronic pancreatitis.

INTRODUCTION

In the past decade the role of obesity and fats in relation to various disease processes has been studied. According to recent estimates, more than 1/3rd of US adults are obese (37.5%) [16, 17]. The annual medical costs associated with obesity were estimated at $147 billion for 2008[18], and are projected to reach $ 960 billion by 2030 [19].

Obesity has long been labelled an epidemic, with clinicians and scientists recognizing the deleterious effects of fats, be it the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal or renal system [20]. Apart from its role in hypertension and atherosclerosis, in recent years scientists are understanding the role of free fatty acids (FFA) in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), acute pancreatitis (AP) and also in various cancers [21–23].

Certain studies suggest the risk of SAP is 2–3 fold higher in obese than non-obese individuals [24]. Obesity is known to worsen AP outcomes [1–8], and the mortality associated with MSOF complicating SAP may be as high as 46% [25]. In obesity, it is the visceral and android fat distribution that has been known to predict severity of acute pancreatitis [26] and several recent articles emphasize the association of visceral fat with worse outcomes [5, 27–29]. Over recent years there has also been more recognition of fat within the pancreas (Intrapancreatic fat or nonalcoholic fatty pancreas), which has been investigated further [15, 30–34]. The temporal relationship between obesity and visceral fat, in particular pancreatic fat has been documented [34, 35], but the implications of pancreatic fat with reference to its proximity to pancreatic acinar cells and its toxic effects on acinar cells has only recently come to light [15, 32]. We know that fat is also increased within the pancreas in chronic pancreatitis (CP) [32, 36, 37], however no relationship has been recognized between obesity and CP.

In this article we will summarize our understanding on the recent advances on this subject (Table 1), discuss the implications of obesity and fatty pancreas on AP, the probable mechanism by which obesity effects outcomes in AP, is the role of systemic lipotoxicity with reference to SAP, and how fat in CP is different from fat in AP (Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of the recent advances involving the role of fat in pancreatitis

Previously known information:

| |

New information:

| |

Table 2.

Comparison of intrapancreatic fat in acute and chronic pancreatitis.

| Acute Pancreatitis | Chronic Pancreatitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Relative amount in non-obese individuals | Lower | higher |

| Relationship to BMI | Positive correlation | No Correlation |

| Composition of fat | Predominantly UFA’s in obesity | Unknown |

| Presence of Surrounding Fibrosis | Minimal | Significant, with “walling off” of fat |

| Macromolecular diffusion between fat and parenchyma | significant | reduced |

| Amount of Fat necrosis | Present, increases with obesity, IPF | reduced |

| Amount of PFAN | Significant | Minimal |

| Role of IPF in acute Exacerbation | Significant | Minimal |

PANCREATIC FAT AND ACUTE PANCREATITIS

The fat in adipocytes is composed of triglycerides, which are free fatty acids hinged to a glycerol backbone, forming >80% of adipocyte mass [38–40]. As one gets more obese (BMI>30), more fat accumulates in various areas in our body including within the abdominal viscera such as the pancreas [15, 34, 35] and also around the viscera. Saisho et al have shown that pancreatic fat increases with increasing BMI [34]. We have studied human pancreas autopsy samples of obese and non-obese controls and compared them with obese and non-obese patients with AP, and noted that the amount of intrapancreatic fat increased with increasing BMI in both controls and patients with AP [15, 32].

The mechanism by which obesity may influence AP is being explored. Fat adjacent to acinar tissue has been shown to be associated with parenchymal damage in AP [15, 32, 41, 42], and it has been shown that fat in the pancreas during acute pancreatitis, has a direct toxic effect on the pancreatic parenchyma [15, 32]. On human pancreatic samples we noted that necrosed adipocytes were surrounded by a zone of necrosed parenchyma, and the worst damage was immediately around the fat (peri-fat acinar necrosis; PFAN), with progressively less necrosis noted with increasing distance from the necrosed fat. PFAN is an ante-mortem phenomenon since it is surrounded by CD68 positive macrophages and was significantly more in patients with pancreatitis compared to controls. This PFAN was significantly higher in SAP and was the predominant form of necrosis noted on the autopsy samples [15]. The other form of necrosis noted, was isolated acinar necrosis i.e. necrosis in pancreatic parenchyma not adjacent to the necrosed fat. This was found to be significantly lesser than PFAN in SAP. The sum of both forms, i.e. total necrosis, was also noted to be significantly higher in obese individuals who had SAP.

On a molecular level it is important to recognize the predominant free fatty acids (FFA) contained in visceral fat impact the severity of AP It has been shown on fluid analysis of necrosectomy samples, which were from obese patients, that the predominant long chain fatty acids (up to 73%) were unsaturated fatty acids (UFA), comprising primarily of oleic acid and linoleic acid. This is similar to what other investigators have noted where UFA’s accumulate in the pancreas adipocytes and can be 6–11 fold higher in necrosed pancreas samples as compared to a normal pancreas [33, 43]. Similarly, in obese patients with NAFLD the quantities of UFA’s were noted to be significantly increased in abdominal fat [44]. Hence, there is sufficient evidence that the predominant fatty acids that accumulate in abdominal and visceral fat in obesity are UFA’s, which ties in well with our current dietary trends and recommended daily allowance according to which the saturated fat should be <30% with correspondingly more unsaturated fat (http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2000/document/choose.htm).

The direct deleterious effects of UFA’s on pancreatic acinar tissue have also been well documented [45]. Co-culturing mice acinar tissue with adipocytes [15] or activated pancreatic homogenates along with triglyceride [45], resulted in a significant amount of acinar necrosis, increased levels of lipase in the medium and resultant increase in FFA’s. These were prevented by lipase inhibition. Addition of long chain unsaturated fatty acids alone caused acinar necrosis.[15, 45] Co-incubation of VLDL with acinar cells and cholecystokinin also resulted in an increase of FFA’s [46]. More significantly, similar trends of increased FFA’s in particular UFA’s have been documented in sera of patients with severe acute pancreatitis [47, 48].

In studying the toxic effects of FFA’s on mice pancreatic acini in more detail, we noted a rise in cytosolic calcium which was released from an intracellular calcium pool, fall in ATP levels with leakage of cytochrome c and inhibition of mitochondrial complexes I and V, confirming necrosis as the form of cell death induced by the FFA’s[15]. The UFA’s linoleic acid, oleic acid and linolenic acid were found to be toxic to acinar cells and not the SFA’s palmitic and stearic acid[15, 45]. Of note, in these studies the levels of resistin were increased in response to lipolytic generation of FFAs, and mRNA levels of TNF-α and chemokines CXCL1 and CXCL2 were also up-regulated in response to linoleic acid and not palmitic acid.

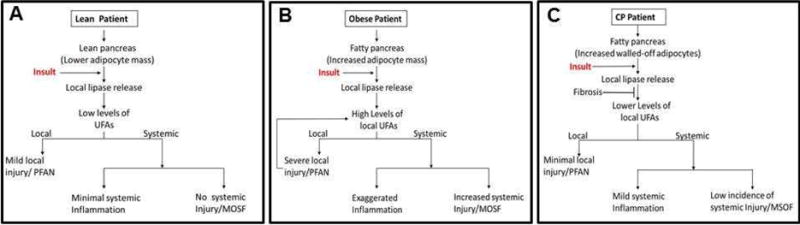

Hence in SAP, after the initial insult, the extracellular release of lipase may cause lipolysis of IPF, with a consequent increase in FFA’s, and resultant direct toxicity to the acinar cells causing necrosis (lipolytic flux). The localized spread of UFA’s in the surrounding tissues (as evidenced by the presence of saponified fatty acids seen as positive von-Kossa staining in the exocrine parenchyma) results in the phenomenon of PFAN. Thus higher IPF in obesity is associated with more PFAN and worse pancreatic necrosis. The potential interaction between the adipocyte and acinar compartment in different disease states is summarized in the schematics shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematics describe the influence of adipocyte mass and fibrosis on the progression of an acute pancreatitis attack.

An attack induced by an insult in lean (A), obese (B) and chronic pancreatitis (CP, C) patients progresses differently. The lipases released by the insult increase UFA formation when the increased adipocyte mass, such as in obesity is adjacent to the acinar cells. This UFA formation is reduced by fibrosis walling-off the adipocytes in CP.

It would be worthwhile to mention that in the case of Hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis where there is an abundance of substrate, different studies have shown worse outcomes in AP [32, 49–52]. This suggests the possible role of lipases, in influencing the outcomes of acute pancreatitis. Of the four different of lipases in the pancreas [namely PTL(pancreatic triglyceride lipase),CEL (carboxyester lipase) and pancreatic lipase related proteins 1 and 2 (PLRP-1, 2)] [53], the exact lipase that contributes to lipotoxicity is yet to be determined. The mechanism by which the triglycerides are released from adipocytes is also yet to be determined exactly. In our previous studies of adipocyte and acinar cell co-culture, addition of a serine protease-specific trypsin inhibitor resulted in a 20% drop in the generation of glycerol. Hence trypsin apart from its traditional known role in acinar injury [54–59] could also be playing a role in adipocyte injury, and further studies to validate this are required.

PANCREATIC FAT AND CHRONIC PANCREATITIS

On studying the natural history of CP, it has been suggested to be a continuum of AP leading to recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP) that eventually progresses to CP [60–63]. Progression from RAP to CP involves a change in the morphology of the pancreas with reduction in the pancreatic parenchymal mass, and its replacement with adipose tissue and fibrosis [64–66].

The differential roles of intrapancreatic fat in AP vs. CP are summarized in Table 2, and how fibrosis may influence the course of an acute exacerbation of CP is schematically shown in figure 1. A comparison of non-obese controls and non-obese CP showed that IPF was higher in CP[32]. The linear relationship that exists between IPF and BMI in obesity and AP is lost during progression to CP and for the same BMI patients suffering from CP may have a higher amount of IPF compared to their control counterparts. However, despite having a large amount of IPF the severity of acute attacks in CP are milder as compared to obese patients with AP, with mortality rarely being attributed to AP [62, 67, 68]. Interestingly, there have been case reports of AP and CP possibly being associated with the metabolic syndrome in children as no other etiology was observed [69]. Whether this remains true in adults remains to be determined.

Studies in the past have noted that fibrosis in CP can be 10 fold more than that of controls [70] with estimates suggesting that fibrous tissue may be up to 66% of the pancreatic area in CP [32, 70]. It is known that during CP, there is an induction of genes that transcribe TGF-β and other fibrogenic growth factors, which in turn stimulate pancreatic stellate cells (PSC) to produce extracellular matrix (ECM) and fibrous tissue [71, 72]. Several noxious stimuli may initiate fibrogenesis and the role of ethanol has been extensively studied in this phenomenon [73, 74]. There is also evidence that on cessation of alcohol, fibrogenesis could be partly reversed by induction of PSC apoptosis [75]. Apart from alcohol, animal models have shown that chronic high fat diets in rats induce fibrogenesis too [76, 77]. In vitro studies [78], rodent models using high fat diets [76, 79] and studies on tissue from patients with chronic pancreatitis support lipid peroxidation products to play a role in stellate cell activation and fibrogenesis. The predominant collagen present in fibrous tissue, produced by the PSC is type I collagen [80–82], with other components of the ECM being mainly proteoglycans. It has been shown that the arrangement of Type I collagen in the interstitial matrix affects the diffusion of macromolecules across it [83]. Additionally, apart from being a physical barrier to macromolecular diffusion, electrostatic repulsive forces from collagen and proteoglycans may play a role in limiting diffusion [83].

In contrast to CP, there is minimal fibrosis in AP. Apart from the aforementioned changes, CP pathology is distinct in the relationship between fibrosis, fat and parenchymal tissue. During CP, large islands of adipose tissue are walled off from the acinar parenchyma by fibrous tissue, limiting interaction between the two compartments in contrast to AP, where lipolysis of unsaturated adipose tissue triglyceride releases UFA’s that leach into the surrounding tissue and cause necrosis, as there is no fibrous tissue to limit the interaction.

While all these studies were performed on alcoholic or non-congenital etiologies of CP, Singhi et al recently studied the histopathology of PRSS1 hereditary pancreatitis [84] and noted that while children and young adults had predominant inter and interlobular fibrosis (Figure 1C in the referred manuscript), with increasing age there was a progressive loss of acinar mass and an increase in fatty replacement of the pancreas. While the amount of fibrosis was not quantified biochemically or histologically, it was localized at the periphery of the fat and surrounded the pancreatic ducts (Figure 2 of the referenced manuscript). Fatty replacement of the pancreas has also been noted to occur in rodent models of hereditary pancreatitis [85]. The fatty acid composition of the fat stored in these adipocytes and those in chronic pancreatitis remains unknown (Table 2). To conclude, with recurrent attacks of AP, and with increasing fibrosis, there is gradual walling off of the fat and parenchyma, and eventually the lipolytic flux between the two compartments gets limited and attacks of AP are attenuated (Figure 1). As mentioned earlier, in CP there is a reduction in acinar mass. There has been some thought that the lower acinar mass may be contributing to a muted response. However, it is also known that serum levels of lipase and amylase do not correlate well with the severity of AP [86] and children and adolescents with lower pancreatic acinar masses have been found to have similar severity of AP attacks [87–91]. It has also been noted that the severity of attacks reduces sharply after the initial attack in AP [62]. This suggests that apart from a lower exocrine acinar mass possibly contributing to milder attacks, fibrosis is very likely to have a role in dampening the severity of attacks.

SYSTEMIC LIPOTOXICITY IN SAP AND MSOF

Early mortality in SAP usually involves sustained failure of one or more organ systems manifesting as respiratory failure and/or acute kidney failure. We know that in SAP the levels of cytokines in the serum particularly TNF-α, IL-6 and adipokines (resistin and visfatin) are significantly elevated [92–95]. Low adiponectin levels have been associated with worse outcomes in AP [96].

In SAP associated with obesity, cytokines and adipokines have so far been noted as markers of SAP [92–94, 97]. It is unknown whether cytokines and adipokines contribute to the progression of AP. While IL-6 and TNF-α are increased in mice with oleic acid induced acute lung injury [98, 99] and in obese mice with SAP [15, 100], mortality and SAP in obese mice did not improve by neutralization of IL-6 or in IL-6 knock outs[101], and IL-6 may have a protective role in acute lung injury[102]. Similarly TNF-α mimetics have been shown to improve lung injury and [103] case reports on anti-TNF therapy [104–108] have shown mixed outcomes in AP.

We have shown that SAP and mortality were induced in obese mice that were administered IL12, 18 [15] or in rats with intraductal infusion of the unsaturated triglyceride glyceryltrilinoleate [109]. In these models the levels of cytokines including of TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1 in obese mice (and IL-1beta and KC/GRO in rats) increased along with serum unsaturated fatty acid, but treatment with the lipase inhibitor orlistat reduced the levels of these cytokines and UFAs significantly, suggesting that the increase in cytokines was a response to UFAs generated by the lipolysis resulting in necrosis and an inflammatory response. Our recent in-vitro studies have also shown that when pancreatic acini were incubated with adipocytes, the levels of adipokines (resistin) and FFA’s increased, which was prevented by inhibiting fatty acid generation using a lipase inhibitor. Adipokines (resistin and visfatin) were tested for inciting necrosis in acinar cells and were found to have no such effect [32]. Hence, apart from lipolysis being directly responsible for necrosis, it is also a likely contributor to the milieu of exaggerated inflammation that characterizes SAP.

Obesity has also been associated with increased mortality in burns and severe trauma patients apart from acute pancreatitis [12–14]. The average length of stay is prolonged for these patients and recoveries are complicated by multisystem organ failure and mortality can be 2 fold higher in obese trauma patients [110]. With higher adipokines and other cytokines in obesity, the inflammation initiated by burns and trauma may get amplified, leading to MSOF. On looking at the data available for obesity, critical illness and trauma, various studies have shown an elevated serum lipase[111–113] to be associated with worse outcomes. In our studies with ob/ob mice with SAP, we noted acute renal failure with elevation in BUN and creatinine levels. On pathology we found oil red O stained in renal tubular vacuoles. Additionally, there was an increase in serum UFAs in mice with SAP. The infusion of oleic acid in rodents to induce acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome is a commonly practiced model [99, 114, 115], which confirms the toxicity of UFAs generated by the lipolysis of visceral fat. Our studies also noted similar patterns of lung injury with an increase in apoptotic cells and lung myeloperoxidase levels. All the above changes were reversed with orlistat- a lipase inhibitor, which also normalized the increase in serum UFAs. These studies suggest that the UFA’s may have a direct toxic effect to the renal tubular epithelium and may be a mechanism by which lipotoxicity contributes to MSOF. Further studies to validate this in humans are needed.

SUMMARY

With lipotoxicity now being recognized as a strong contributor to increased morbidity and mortality in SAP, sepsis, trauma and burns, it presents us with an opportunity to intervene. There have been no studies done to demonstrate the effectiveness of lipase inhibition in reducing severity of AP in humans. Further studies need to be directed towards studying lipolytic fluxes in AP and the effects of blocking these on the local and the systemic effects postulated above.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This project was supported by Grant Number RO1DK092460 (VPS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest exist.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Abu Hilal M, Armstrong T. The impact of obesity on the course and outcome of acute pancreatitis. Obes Surg. 2008;18:326–328. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papachristou GI, Papachristou DJ, Avula H, Slivka A, Whitcomb DC. Obesity increases the severity of acute pancreatitis: Performance of apache-o score and correlation with the inflammatory response. Pancreatology. 2006;6:279–285. doi: 10.1159/000092689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porter KA, Banks PA. Obesity as a predictor of severity in acute pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol. 1991;10:247–252. doi: 10.1007/BF02924162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shin KY, Lee WS, Chung DW, Heo J, Jung MK, Tak WY, Kweon YO, Cho CM. Influence of obesity on the severity and clinical outcome of acute pancreatitis. Gut Liver. 2011;5:335–339. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2011.5.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Leary DP, O’Neill D, McLaughlin P, O’Neill S, Myers E, Maher MM, Redmond HP. Effects of abdominal fat distribution parameters on severity of acute pancreatitis. World J Surg. 2012;36:1679–1685. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1414-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sempere L, Martinez J, de Madaria E, Lozano B, Sanchez-Paya J, Jover R, Perez-Mateo M. Obesity and fat distribution imply a greater systemic inflammatory response and a worse prognosis in acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2008;8:257–264. doi: 10.1159/000134273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans AC, Papachristou GI, Whitcomb DC. Obesity and the risk of severe acute pancreatitis. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 56:169–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen SM, Xiong GS, Wu SM. Is obesity an indicator of complications and mortality in acute pancreatitis? An updated meta-analysis. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:244–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2012.00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mutinga M, Rosenbluth A, Tenner SM, Odze RR, Sica GT, Banks PA. Does mortality occur early or late in acute pancreatitis? Int J Pancreatol. 2000;28:91–95. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:28:2:091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu CY, Yeh CN, Hsu JT, Jan YY, Hwang TL. Timing of mortality in severe acute pancreatitis: Experience from 643 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1966–1969. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i13.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carnovale A, Rabitti PG, Manes G, Esposito P, Pacelli L, Uomo G. Mortality in acute pancreatitis: Is it an early or a late event? Jop. 2005;6:438–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neville AL, Brown CV, Weng J, Demetriades D, Velmahos GC. Obesity is an independent risk factor of mortality in severely injured blunt trauma patients. Arch Surg. 2004;139:983–987. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.9.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown CV, Neville AL, Rhee P, Salim A, Velmahos GC, Demetriades D. The impact of obesity on the outcomes of 1,153 critically injured blunt trauma patients. J Trauma. 2005;59:1048–1051. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000189047.65630.c5. discussion 1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottschlich MM, Mayes T, Khoury JC, Warden GD. Significance of obesity on nutritional, immunologic, hormonal, and clinical outcome parameters in burns. J Am Diet Assoc. 1993;93:1261–1268. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(93)91952-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navina S, Acharya C, DeLany JP, Orlichenko LS, Baty CJ, Shiva SS, Durgampudi C, Karlsson JM, Lee K, Bae KT, Furlan A, Behari J, Liu S, McHale T, Nichols L, Papachristou GI, Yadav D, Singh VP. Lipotoxicity causes multisystem organ failure and exacerbates acute pancreatitis in obesity. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:107ra110. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among us adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the united states, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: Payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w822–831. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L, Caballero B, Kumanyika SK. Will all americans become overweight or obese? Estimating the progression and cost of the us obesity epidemic. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:2323–2330. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu CY, McCulloch CE, Iribarren C, Darbinian J, Go AS. Body mass index and risk for end-stage renal disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:21–28. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-1-200601030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergstrom A, Hsieh CC, Lindblad P, Lu CM, Cook NR, Wolk A. Obesity and renal cell cancer–a quantitative review. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:984–990. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michaud DS, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Fuchs CS. Physical activity, obesity, height, and the risk of pancreatic cancer. JAMA. 2001;286:921–929. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of u.S. Adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suazo-Barahona J, Carmona-Sanchez R, Robles-Diaz G, Milke-Garcia P, Vargas-Vorackova F, Uscanga-Dominguez L, Pelaez-Luna M. Obesity: A risk factor for severe acute biliary and alcoholic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1324–1328. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.442_l.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vege SS, Gardner TB, Chari ST, Munukuti P, Pearson RK, Clain JE, Petersen BT, Baron TH, Farnell MB, Sarr MG. Low mortality and high morbidity in severe acute pancreatitis without organ failure: A case for revising the atlanta classification to include “moderately severe acute pancreatitis”. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:710–715. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mery CM, Rubio V, Duarte-Rojo A, Suazo-Barahona J, Pelaez-Luna M, Milke P, Robles-Diaz G. Android fat distribution as predictor of severity in acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2002;2:543–549. doi: 10.1159/000066099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadr-Azodi O, Orsini N, Andren-Sandberg A, Wolk A. Abdominal and total adiposity and the risk of acute pancreatitis: A population-based prospective cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:133–139. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yashima Y, Isayama H, Tsujino T, Nagano R, Yamamoto K, Mizuno S, Yagioka H, Kawakubo K, Sasaki T, Kogure H, Nakai Y, Hirano K, Sasahira N, Tada M, Kawabe T, Koike K, Omata M. A large volume of visceral adipose tissue leads to severe acute pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1213–1218. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Funnell IC, Bornman PC, Weakley SP, Terblanche J, Marks IN. Obesity: An important prognostic factor in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1993;80:484–486. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitt HA. Hepato-pancreato-biliary fat: The good, the bad and the ugly. HPB (Oxford) 2007;9:92–97. doi: 10.1080/13651820701286177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Geenen EJ, Smits MM, Schreuder TC, van der Peet DL, Bloemena E, Mulder CJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is related to nonalcoholic fatty pancreas disease. Pancreas. 2010;39:1185–1190. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181f6fce2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Acharya C, Cline RA, Jaligama D, Noel P, Delany JP, Bae K, Furlan A, Baty CJ, Karlsson JM, Rosario BL, Patel K, Mishra V, Dugampudi C, Yadav D, Navina S, Singh VP. Fibrosis reduces severity of acute-on-chronic pancreatitis in humans. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:466–475. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinnick KE, Collins SC, Londos C, Gauguier D, Clark A, Fielding BA. Pancreatic ectopic fat is characterized by adipocyte infiltration and altered lipid composition. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:522–530. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saisho Y, Butler AE, Meier JJ, Monchamp T, Allen-Auerbach M, Rizza RA, Butler PC. Pancreas volumes in humans from birth to age one hundred taking into account sex, obesity, and presence of type-2 diabetes. Clin Anat. 2007;20:933–942. doi: 10.1002/ca.20543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmitz-Moormann P, Pittner PM, Heinze W. Lipomatosis of the pancreas. A morphometrical investigation. Pathol Res Pract. 1981;173:45–53. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(81)80006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soyer P, Spelle L, Pelage JP, Dufresne AC, Rondeau Y, Gouhiri M, Scherrer A, Rymer R. Cystic fibrosis in adolescents and adults: Fatty replacement of the pancreas–ct evaluation and functional correlation. Radiology. 1999;210:611–615. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.3.r99mr08611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaughn DD, Jabra AA, Fishman EK. Pancreatic disease in children and young adults: Evaluation with ct. Radiographics. 1998;18:1171–1187. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.18.5.9747614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ren J, Dimitrov I, Sherry AD, Malloy CR. Composition of adipose tissue and marrow fat in humans by 1h nmr at 7 tesla. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:2055–2062. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D800010-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas LW. The chemical composition of adipose tissue of man and mice. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci. 1962;47:179–188. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1962.sp001589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garaulet M, Hernandez-Morante JJ, Lujan J, Tebar FJ, Zamora S. Relationship between fat cell size and number and fatty acid composition in adipose tissue from different fat depots in overweight/obese humans. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:899–905. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kloppel G, Dreyer T, Willemer S, Kern HF, Adler G. Human acute pancreatitis: Its pathogenesis in the light of immunocytochemical and ultrastructural findings in acinar cells. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1986;409:791–803. doi: 10.1007/BF00710764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmitz-Moormann P. Comparative radiological and morphological study of the human pancreas. Iv Acute necrotizing pancreatitis in man. Pathol Res Pract. 1981;171:325–335. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(81)80105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Panek J, Sztefko K, Drozdz W. Composition of free fatty acid and triglyceride fractions in human necrotic pancreatic tissue. Med Sci Monit. 2001;7:894–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Araya J, Rodrigo R, Videla LA, Thielemann L, Orellana M, Pettinelli P, Poniachik J. Increase in long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid n − 6/n − 3 ratio in relation to hepatic steatosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2004;106:635–643. doi: 10.1042/CS20030326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mossner J, Bodeker H, Kimura W, Meyer F, Bohm S, Fischbach W. Isolated rat pancreatic acini as a model to study the potential role of lipase in the pathogenesis of acinar cell destruction. Int J Pancreatol. 1992;12:285–296. doi: 10.1007/BF02924368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang F, Wang Y, Sternfeld L, Rodriguez JA, Ross C, Hayden MR, Carriere F, Liu G, Schulz I. The role of free fatty acids, pancreatic lipase and ca+ signalling in injury of isolated acinar cells and pancreatitis model in lipoprotein lipase-deficient mice. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2009;195:13–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2008.01933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sztefko K, Panek J. Serum free fatty acid concentration in patients with acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2001;1:230–236. doi: 10.1159/000055816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Domschke S, Malfertheiner P, Uhl W, Buchler M, Domschke W. Free fatty acids in serum of patients with acute necrotizing or edematous pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol. 1993;13:105–110. doi: 10.1007/BF02786078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buch A, Buch J, Carlsen A, Schmidt A. Hyperlipidemia and pancreatitis. World J Surg. 1980;4:307–314. doi: 10.1007/BF02393387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dominguez-Munoz JE, Malfertheiner P, Ditschuneit HH, Blanco-Chavez J, Uhl W, Buchler M, Ditschuneit H. Hyperlipidemia in acute pancreatitis. Relationship with etiology, onset, and severity of the disease. Int J Pancreatol. 1991;10:261–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deng LH, Xue P, Xia Q, Yang XN, Wan MH. Effect of admission hypertriglyceridemia on the episodes of severe acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4558–4561. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lloret Linares C, Pelletier AL, Czernichow S, Vergnaud AC, Bonnefont-Rousselot D, Levy P, Ruszniewski P, Bruckert E. Acute pancreatitis in a cohort of 129 patients referred for severe hypertriglyceridemia. Pancreas. 2008;37:13–12. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31816074a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lowe ME. The triglyceride lipases of the pancreas. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:2007–2016. doi: 10.1194/jlr.r200012-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saluja AK, Bhagat L, Lee HS, Bhatia M, Frossard JL, Steer ML. Secretagogue-induced digestive enzyme activation and cell injury in rat pancreatic acini. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G835–842. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.4.G835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh VP, Bhagat L, Navina S, Sharif R, Dawra RK, Saluja AK. Protease-activated receptor-2 protects against pancreatitis by stimulating exocrine secretion. Gut. 2007;56:958–964. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.094268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh VP, Saluja AK, Bhagat L, van Acker GJ, Song AM, Soltoff SP, Cantley LC, Steer ML. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent activation of trypsinogen modulates the severity of acute pancreatitis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1387–1395. doi: 10.1172/JCI12874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gaiser S, Daniluk J, Liu Y, Tsou L, Chu J, Lee W, Longnecker DS, Logsdon CD, Ji B. Intracellular activation of trypsinogen in transgenic mice induces acute but not chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 60:1379–1388. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.226175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ji B, Gaiser S, Chen X, Ernst SA, Logsdon CD. Intracellular trypsin induces pancreatic acinar cell death but not nf-kappab activation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17488–17498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.005520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dawra R, Sah RP, Dudeja V, Rishi L, Talukdar R, Garg P, Saluja AK. Intra-acinar trypsinogen activation mediates early stages of pancreatic injury but not inflammation in mice with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:2210–2217 e2212. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yadav D, O’Connell M, Papachristou GI. Natural history following the first attack of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 107:1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nojgaard C, Becker U, Matzen P, Andersen JR, Holst C, Bendtsen F. Progression from acute to chronic pancreatitis: Prognostic factors, mortality, and natural course. Pancreas. 40:1195–1200. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318221f569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lankisch PG, Breuer N, Bruns A, Weber-Dany B, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Natural history of acute pancreatitis: A long-term population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2797–2805. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.405. quiz 2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aoun E, Slivka A, Papachristou DJ, Gleeson FC, Whitcomb DC, Papachristou GI. Rapid evolution from the first episode of acute pancreatitis to chronic pancreatitis in human subjects. JOP. 2007;8:573–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kloppel G, Maillet B. Chronic pancreatitis: Evolution of the disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 1991;38:408–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kloppel G, Maillet B. The morphological basis for the evolution of acute pancreatitis into chronic pancreatitis. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1992;420:1–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01605976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suda K, Takase M, Takei K, Kumasaka T, Suzuki F. Histopathologic and immunohistochemical studies on the mechanism of interlobular fibrosis of the pancreas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1302–1305. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-1302-HAISOT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nojgaard C, Matzen P, Bendtsen F, Andersen JR, Christensen E, Becker U. Factors associated with long-term mortality in acute pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 46:495–502. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.537686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Otsuki M. Chronic pancreatitis in japan: Epidemiology, prognosis, diagnostic criteria, and future problems. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:315–326. doi: 10.1007/s005350300058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rajesh G, Kumar H, Menon S, Balakrishnan V. Pancreatitis in the setting of the metabolic syndrome. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2012;31:79–82. doi: 10.1007/s12664-012-0172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Valderrama R, Navarro S, Campo E, Camps J, Gimenez A, Pares A, Caballeria J. Quantitative measurement of fibrosis in pancreatic tissue. Evaluation of a colorimetric method. Int J Pancreatol. 1991;10:23–29. doi: 10.1007/BF02924250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mews P, Phillips P, Fahmy R, Korsten M, Pirola R, Wilson J, Apte M. Pancreatic stellate cells respond to inflammatory cytokines: Potential role in chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2002;50:535–541. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.4.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yokota T, Denham W, Murayama K, Pelham C, Joehl R, Bell RH., Jr Pancreatic stellate cell activation and mmp production in experimental pancreatic fibrosis. J Surg Res. 2002;104:106–111. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2002.6403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Apte MV, Pirola RC, Wilson JS. Battle-scarred pancreas: Role of alcohol and pancreatic stellate cells in pancreatic fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21(Suppl 3):S97–S101. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hu R, Wang YL, Edderkaoui M, Lugea A, Apte MV, Pandol SJ. Ethanol augments pdgf-induced nadph oxidase activity and proliferation in rat pancreatic stellate cells. Pancreatology. 2007;7:332–340. doi: 10.1159/000105499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vonlaufen A, Phillips PA, Xu Z, Zhang X, Yang L, Pirola RC, Wilson JS, Apte MV. Withdrawal of alcohol promotes regression while continued alcohol intake promotes persistence of lps-induced pancreatic injury in alcohol-fed rats. Gut. 2011;60:238–246. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.211250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang X, Cui Y, Fang L, Li F. Chronic high-fat diets induce oxide injuries and fibrogenesis of pancreatic cells in rats. Pancreas. 2008;37:e31–38. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181744b50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang LP, Ma F, Abshire SM, Westlund KN. Prolonged high fat/alcohol exposure increases trpv4 and its functional responses in pancreatic stellate cells. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304:R702–711. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00296.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Siech M, Zhou Z, Zhou S, Bair B, Alt A, Hamm S, Gross H, Mayer J, Beger HG, Tian X, Kornmann M, Bachem MG. Stimulation of stellate cells by injured acinar cells: A model of acute pancreatitis induced by alcohol and fat (vldl) Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G1163–1171. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90468.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Casini A, Galli A, Pignalosa P, Frulloni L, Grappone C, Milani S, Pederzoli P, Cavallini G, Surrenti C. Collagen type i synthesized by pancreatic periacinar stellate cells (psc) co-localizes with lipid peroxidation-derived aldehydes in chronic alcoholic pancreatitis. J Pathol. 2000;192:81–89. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH675>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.di Mola FF, Friess H, Martignoni ME, Di Sebastiano P, Zimmermann A, Innocenti P, Graber H, Gold LI, Korc M, Buchler MW. Connective tissue growth factor is a regulator for fibrosis in human chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1999;230:63–71. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199907000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Haber PS, Keogh GW, Apte MV, Moran CS, Stewart NL, Crawford DH, Pirola RC, McCaughan GW, Ramm GA, Wilson JS. Activation of pancreatic stellate cells in human and experimental pancreatic fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1087–1095. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65211-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Apte MV, Haber PS, Darby SJ, Rodgers SC, McCaughan GW, Korsten MA, Pirola RC, Wilson JS. Pancreatic stellate cells are activated by proinflammatory cytokines: Implications for pancreatic fibrogenesis. Gut. 1999;44:534–541. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.4.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stylianopoulos T, Diop-Frimpong B, Munn LL, Jain RK. Diffusion anisotropy in collagen gels and tumors: The effect of fiber network orientation. Biophys J. 2010;99:3119–3128. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Singhi AD, Pai RK, Kant JA, Bartholow TL, Zeh HJ, Lee KK, Wijkstrom M, Yadav D, Bottino R, Brand RE, Chennat JS, Lowe ME, Papachristou GI, Slivka A, Whitcomb DC, Humar A. The histopathology of prss1 hereditary pancreatitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:346–353. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gaiser S, Daniluk J, Liu Y, Tsou L, Chu J, Lee W, Longnecker DS, Logsdon CD, Ji B. Intracellular activation of trypsinogen in transgenic mice induces acute but not chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2011;60:1379–1388. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.226175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Banks PA, Freeman ML. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2379–2400. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen CF, Kong MS, Lai MW, Wang CJ. Acute pancreatitis in children: 10-year experience in a medical center. Acta Paediatr Taiwan. 2006;47:192–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Werlin SL, Kugathasan S, Frautschy BC. Pancreatitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:591–595. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200311000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lautz TB, Chin AC, Radhakrishnan J. Acute pancreatitis in children: Spectrum of disease and predictors of severity. J Pediatr Surg. 46:1144–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.DeBanto JR, Goday PS, Pedroso MR, Iftikhar R, Fazel A, Nayyar S, Conwell DL, Demeo MT, Burton FR, Whitcomb DC, Ulrich CD, 2nd, Gates LK., Jr Acute pancreatitis in children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1726–1731. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Weizman Z, Durie PR. Acute pancreatitis in childhood. J Pediatr. 1988;113:24–29. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80523-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schaffler A, Hamer O, Dickopf J, Goetz A, Landfried K, Voelk M, Herfarth H, Kopp A, Buchler C, Scholmerich J, Brunnler T. Admission resistin levels predict peripancreatic necrosis and clinical severity in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2474–2484. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schaffler A, Hamer OW, Dickopf J, Goetz A, Landfried K, Voelk M, Herfarth H, Kopp A, Buechler C, Scholmerich J, Brunnler T. Admission visfatin levels predict pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis in acute pancreatitis and correlate with clinical severity. Am J Gastroenterol. 106:957–967. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Malleo G, Mazzon E, Siriwardena AK, Cuzzocrea S. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in acute pancreatitis: From biological basis to clinical evidence. Shock. 2007;28:130–140. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e3180487ba1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen CJ, Kono H, Golenbock D, Reed G, Akira S, Rock KL. Identification of a key pathway required for the sterile inflammatory response triggered by dying cells. Nat Med. 2007;13:851–856. doi: 10.1038/nm1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sharma A, Muddana V, Lamb J, Greer J, Papachristou GI, Whitcomb DC. Low serum adiponectin levels are associated with systemic organ failure in acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2009;38:907–912. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181b65bbe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Denham W, Yang J, Fink G, Denham D, Carter G, Bowers V, Norman J. Tnf but not il-1 decreases pancreatic acinar cell survival without affecting exocrine function: A study in the perfused human pancreas. J Surg Res. 1998;74:3–7. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1997.5174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhao F, Wang W, Fang Y, Li X, Shen L, Cao T, Zhu H. Molecular mechanism of sustained inflation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:1106–1113. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318265cc6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Inoue H, Nakagawa Y, Ikemura M, Usugi E, Nata M. Molecular-biological analysis of acute lung injury (ali) induced by heat exposure and/or intravenous administration of oleic acid. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2012;14:304–308. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sennello JA, Fayad R, Pini M, Gove ME, Ponemone V, Cabay RJ, Siegmund B, Dinarello CA, Fantuzzi G. Interleukin-18, together with interleukin-12, induces severe acute pancreatitis in obese but not in nonobese leptin-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8085–8090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804091105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pini M, Rhodes DH, Castellanos KJ, Hall AR, Cabay RJ, Chennuri R, Grady EF, Fantuzzi G. Role of il-6 in the resolution of pancreatitis in obese mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;91:957–966. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1211627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bhargava R, Janssen W, Altmann C, Andres-Hernando A, Okamura K, Vandivier RW, Ahuja N, Faubel S. Intratracheal il-6 protects against lung inflammation in direct, but not indirect, causes of acute lung injury in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hartmann EK, Boehme S, Duenges B, Bentley A, Klein KU, Kwiecien R, Shi C, Szczyrba M, David M, Markstaller K. An inhaled tumor necrosis factor-alpha-derived tip peptide improves the pulmonary function in experimental lung injury. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57:334–341. doi: 10.1111/aas.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Maser EA, Deconda D, Lichtiger S, Ullman T, Present DH, Kornbluth A. Cyclosporine and infliximab as rescue therapy for each other in patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1112–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zeitz J, Huber M, Rogler G. serious course of a miliary tuberculosis in a 34-year-old patient with ulcerative colitis and hiv infection under concomitant therapy with infliximab. Med Klin (Munich) 2010;105:314–318. doi: 10.1007/s00063-010-1046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jimenez-Fernandez SG, Tremoulet AH. Infliximab treatment of pancreatitis complicating acute kawasaki disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:1087–1089. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31826108c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Triantafillidis JK, Cheracakis P, Hereti IA, Argyros N, Karra E. Acute idiopathic pancreatitis complicating active crohn’s disease: Favorable response to infliximab treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3334–3336. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fefferman DS, Alsahli M, Lodhavia PJ, Shah SA, Farrell RJ. Re: Triantafillidis et al.–acute idiopathic pancreatitis complicating active crohn’s disease: Favorable response to infliximab treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2510–2511. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Durgampudi C, Noel P, Patel K, Cline R, Trivedi RN, DeLany JP, Yadav D, Papachristou GI, Lee K, Acharya C, Jaligama D, Navina S, Murad F, Singh VP. Acute lipotoxicity regulates severity of biliary acute pancreatitis without affecting its initiation. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:1773–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Glance LG, Li Y, Osler TM, Mukamel DB, Dick AW. Impact of obesity on mortality and complications in trauma patients. Ann Surg. 2014;259:576–581. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ryan CM, Sheridan RL, Schoenfeld DA, Warshaw AL, Tompkins RG. Postburn pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1995;222:163–170. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199508000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Malinoski DJ, Hadjizacharia P, Salim A, Kim H, Dolich MO, Cinat M, Barrios C, Lekawa ME, Hoyt DB. Elevated serum pancreatic enzyme levels after hemorrhagic shock predict organ failure and death. J Trauma. 2009;67:445–449. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181b5dc11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Manjuck J, Zein J, Carpati C, Astiz M. Clinical significance of increased lipase levels on admission to the icu. Chest. 2005;127:246–250. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.1.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Beilman G. Pathogenesis of oleic acid-induced lung injury in the rat: Distribution of oleic acid during injury and early endothelial cell changes. Lipids. 1995;30:817–823. doi: 10.1007/BF02533957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hussain N, Wu F, Zhu L, Thrall RS, Kresch MJ. Neutrophil apoptosis during the development and resolution of oleic acid-induced acute lung injury in the rat. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:867–874. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.6.3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]