Abstract

Toxic anterior segment syndrome (TASS) is an acute sterile postoperative anterior segment inflammation that may occur after anterior segment surgery. I report herein a case that developed mild TASS in one eye after bilateral uneventful cataract surgery, which was masked during early postoperative period under steroid eye drop and mimicking delayed onset TASS after switching to weaker steroid eye drop.

Keywords: Cataract, inflammation, sterile endophthalmitis, toxic anterior segment syndrome

Mild toxic anterior segment syndrome (TASS) that especially happened in one eye after sequential bilateral cataract surgery was masked during early postoperative period under steroid eye drop.

Toxic anterior segment syndrome (TASS) is an acute sterile postoperative anterior segment inflammation that may occur after anterior segment surgery. This syndrome was first named by Monson et al.[1] in 1992, although reports of sterile endophthalmitis or sterile hypopyon began to appear in the literature in 1980.[2,3,4,5,6,7] The syndrome usually presents within 12-48 h of surgery and respond to steroid without accompanying posterior segment inflammation, though delayed onset intraocular inflammation has been reported.[7] Generally, TASS has been described as severe and immediate nature. To my knowledge, mild TASS that especially happened in one eye after sequential bilateral cataract surgery has not been demonstrated. I report a mild case of TASS in one eye after bilateral cataract surgery, which was masked during early postoperative period under steroid eye drop and mimicking delayed onset TASS after switching to weaker steroid eye drop.

Case Report

A 47-year-old Asian woman had bilateral uneventful cataract surgery for central cortical opacity. Phacoemulsification via clear corneal incision and implantation of hydrophilic acrylic intraocular lens (IOL) with polymethylmethacrylate modified C-loop haptics were done in the left eye first and the right eye later with interval of 2 days. The left eye was operated first among three operative cases of cataract and the right eye was operated third among four operative cases of cataract. Preoperatively, the cornea was clear with normal specular microscopic finding, and inflammation was not detected in the anterior chamber of both eyes. The patient had not have any systemic or ocular disease other than diabetes that was controlled well under medication, and diabetic retinopathy was not presented in both eyes.

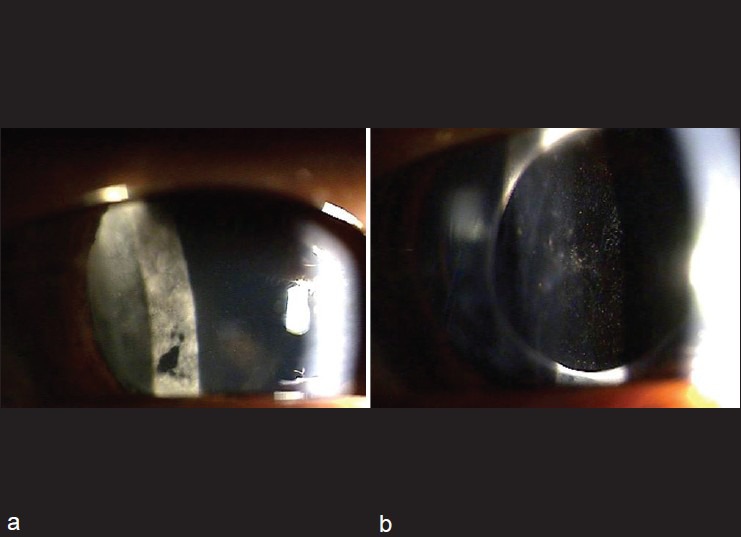

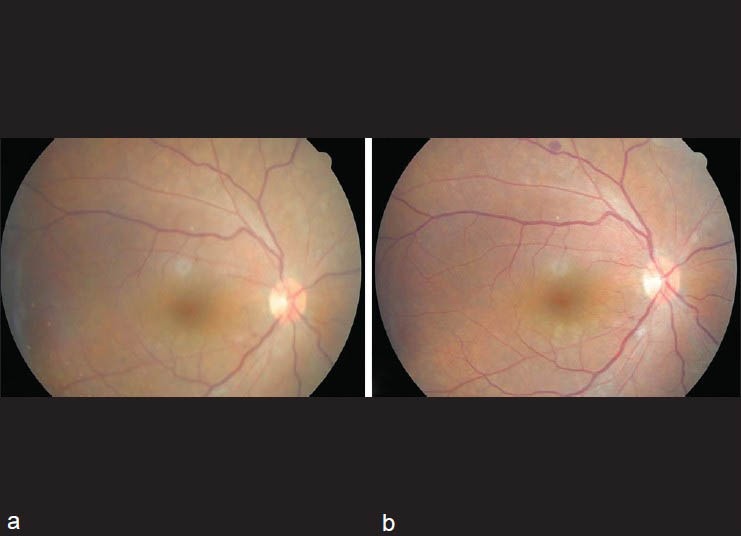

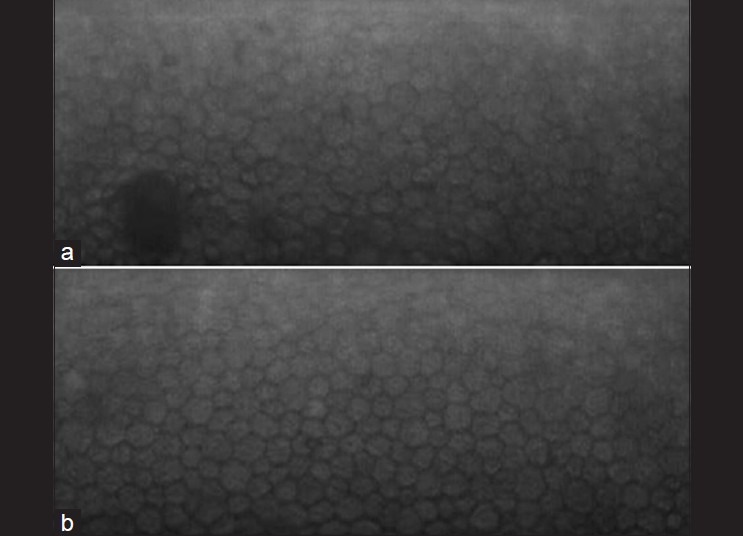

On postoperative day 1 of each eyes, right eye had grade 1+ white blood cells in the anterior segment with uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) of 20/25, while left eye had trace of white blood cells with UCVA of 20/25. Levofloxacin and prednisolone acetate 1% eye drops were prescribed 4 times a day in both eyes. On postoperative day 7 of right eye, anterior inflammation improved and prednisolone acetate 1% was switched to fluorometholone 0.02% in both eyes. On postoperative day 11 of the right eye, the patient visited appealing mild right ocular pain, and the UCVA was dropped to 20/30 presenting diffuse corneal edema. Grade 2+ white blood cells and puff balls were shown in the anterior chamber and inflammatory plaques on the surface of IOL were also found [Fig. 1]. However, the cell was not found in the vitreous and it was so clear enough to examine the retina [Fig. 2]. Intraocular pressure of right eye was 17 mm Hg. In the left eye, cell reaction was not found in the anterior chamber and the vitreous. Since anterior segment inflammation had been controlled with prednisolone acetate 1% immediately after cataract surgery and the vitreous did not present inflammatory cells, the patient was recommended to use prednisolone acetate 1% every 2 h and continue to use levofloxacin in the right eye. On postoperative day 14 of right eye, cellular reaction decreased to grade 1+ and plaques of IOL surface disappeared partially. Intraocular pressure was 15 mm Hg and UCVA was 20/25 in the right eye. The patient was recommended to use prednisolone acetate 1% every 2-4 h until next visit. On postoperative 1 month of right eye, the white blood cells and inflammatory plaques were not observed, and visual acuity improved to 20/20. On specular microscopic examination, the right eye had lower endothelial cell density than the left eye (2343 cells/mm2 vs. 2758 cells/mm2), higher mean cell area (426 ± 116 μm2 vs. 362 ± 57 μm2), and higher coefficient variation (27 vs. 15), [Fig. 3]. The left eye had a normal uncomplicated course during whole treatment period of right eye.

Figure 1.

(a) Slit lamp biomicroscopic image of the right eye on postoperative day 11 showing white blood cells in anterior chamber and white inflammatory plaques on the surface of intraocular implant. (b) On 20 days after intense use of prednisolone acetate 1%, white blood cells disappeared and inflammatory plaques was not observed on the surface of the intraocular implant

Figure 2.

(a) Fundus photograph of right eye on postoperative day 11. The retinal vessels and the optic disc margin are well visualized through clear vitreous even though anterior segment inflammation coexist. (b) On 20 days after intense use of prednisolone acetate 1%, anterior segment inflammation improved and clearer view of the retina was presented

Figure 3.

Specular microscopic image of both eyes on postoperative 1 month. (a) The shape and size of endothelial cells are irregular in damaged eye with toxic anterior segment syndrome. (b) In contrast to damaged eye, regular hexagonality was observed in control eye

Discussion

Toxic anterior segment syndrome is recognized as a specific noninfectious condition but may cause injury in a wide region of the anterior segment. TASS typically manifests within 12-48 h of surgery. The most common finding is diffuse limbus to limbus corneal edema secondary to damage from a toxic insult to the endothelial cell layer. Inflammatory white plaques on the surface of IOL, inflammatory debris “puff ball,” hypopyon, and fibrous reactions can be presented by widespread breakdown of the blood-aqueous barrier. In general, the inflammation improves with topical and/or oral steroids.[7,8] The most common symptom is blurred vision and the patient may experience pain, but most cases are asymptomatic.

It is important to differentiate TASS from infectious bacterial endophthalmitis. In contrast to TASS, 74-79% of patients with infectious endophthalmitis report pain and visual symptoms that develop a mean of 4-7 days postoperatively. And inflammed anterior segment including a variable hypopyon and vitreitis are observed in infectious endophthalmitis.[9] In this case, since anterior segment inflammation had been controlled with prednisolone acetate 1% immediately after cataract surgery and clear vitreous was presented in the course of disease, infectious endophthalmitis was hardly suspected.

In addition, I needed to differentiate Propionibacterium acnes endophthalmitis, which has chronic disease course responding to steroid initially. P. acnes endophthalmitis after cataract surgery is characterized by an indolent low-grade uveitis with latent onset, an initial response to topical steroids, and the frequent absence of more typical endophthalmitis signs and symptoms.[10] A characteristic clinical feature of the syndrome is the presence of a white intracapsular plaque that has been shown histologically to be composed of sequestered organisms inside the peripheral capsular bag. Other important clinical findings include conjunctival injection, keratic precipitates, and vitreitis.[11] In this case, the lens material and cortex were removed completely during the surgery and there was no retained white material in the capsular bag. In addition, any vitreous inflammation was not noted in the course of disease. From those points, this case does not coincide with clinical findings of P. acnes endophthalmitis.

While most reported TASS cases are acute, there have been several instances of delayed-onset TASS following cataract surgery. Jehan et al.[7] have reported 10 cases of delayed-onset inflammation after hydrophilic acrylic IOL (memory lens), which has been theorized that a residual polishing compound on the memory lens was responsible for the postoperative inflammation. Another potential source of delayed-onset TASS is the ingress of ophthalmic ointment used postoperatively in the anterior segment of the eye. Werner et al.[12] described that an oily material coating the anterior surface of the IOL or forming small globules within the anterior chamber was found in a group of delayed-onset TASS. In view of the onset time, this case seemed to be masked for early postoperative period under prednisolone acetate 1% and emerge after switching to fluorometholone 0.02% mimicking delayed onset TASS.

On specular microscopic findings, the eyes with TASS were characterized by lower endothelial cell density than the control eyes, higher mean cell area (coefficient of variation) and lower mean percentage of hexagonal cells.[13] In this case, the eye with TASS had lower endothelial cell density than control eye (2343 cells/mm2 vs. 2758 cells/mm2), higher mean cell area (426 ± 116 μm2 vs. 362 ± 57 μm2), and higher coefficient variation (27 vs. 15). This is considered as toxic response of endothelium, which is in a line of toxic endothelial cell destruction syndrome.

There are several possible causes of noninfectious sterile postoperative inflammation. These include reactions to abnormalities in the pH or ionic composition of irrigating solutions and reactions to residual denatured viscoelastic agents or residual detergent injected during surgery with reusable cannulas or tubing. Immune reactions to residual lens cortex, preservatives, or endotoxins could be causative factors of TASS.[14] In recent times, Bodnar et al.[15] have demonstrated that the most commonly identified risk factors for TASS arise from problems with the instrument-cleaning process. Of these, inadequate flushing of the hand pieces, the use of enzymatic detergents, and the use of ultrasound baths are the most prevalent. None of my surgical devices, instruments, viscoelastic materials, or other materials used in surgery had not been changed for several years in my surgery environment. Even, there had been no difference of surgical devices and materials including antiseptic solutions in operating room between the eye with TASS and control eye in this case. The IOL was the only different material between two eyes. However, I used same IOL produced by one company, and the possibility of the difference of manufacture between two IOLs is low. It is difficult to point out the causes accurately, so i am cautiously assuming that inadequate flushing the ports of the phaco, I and A handpieces, or cannulated instruments from previous cases caused TASS in this case.

Conclusion

I demonstrated mild nature of TASS, which was masked during early postoperative period under prednisolone acetate 1% and mimicked delayed onset TASS after switching to weaker steroid. This case showed rapid clearing of inflammation in the anterior chamber and the cornea without any sequelae after intense use of prednisolone acetate 1%. In addition, this case reminds me of the importance of watching and monitoring whole surgical processes from preparation to sterilization, and suggests that immediate postoperative inflammation of anterior segment after cataract surgery cannot be neglected even its nature is mild, and should be followed sufficiently.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Monson MC, Mamalis N, Olson RJ. Toxic anterior segment inflammation following cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1992;18:184–9. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80929-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meltzer DW. Sterile hypopyon following intraocular lens surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98:100–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020030102008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apple DJ, Mamalis N, Steinmetz RL, Loftfield K, Crandall AS, Olson RJ. Phacoanaphylactic endophthalmitis associated with extracapsular cataract extraction and posterior chamber intraocular lens. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:1528–32. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040031248029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrahams IW. Diagnosis and surgical management of phacoanaphylactic uveitis following extracapsular cataract extraction with intraocular lens implantation. J Am Intraocul Implant Soc. 1985;11:444–7. doi: 10.1016/s0146-2776(85)80080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richburg FA, Reidy JJ, Apple DJ, Olson RJ. Sterile hypopyon secondary to ultrasonic cleaning solution. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1986;12:248–51. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(86)80002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson DB, Donnenfeld ED, Perry HD. Sterile endophthalmitis after sutureless cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:1655–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31748-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jehan FS, Mamalis N, Spencer TS, Fry LL, Kerstine RS, Olson RJ. Postoperative sterile endophthalmitis (TASS) associated with the memorylens. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26:1773–7. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cutler Peck CM, Brubaker J, Clouser S, Danford C, Edelhauser HE, Mamalis N. Toxic anterior segment syndrome: Common causes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010;36:1073–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciulla TA. Update on acute and chronic endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:2237–8. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90521-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aldave AJ, Stein JD, Deramo VA, Shah GK, Fischer DH, Maguire JI. Treatment strategies for postoperative Propionibacterium acnes endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:2395–401. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90546-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark WL, Kaiser PK, Flynn HW, Jr, Belfort A, Miller D, Meisler DM. Treatment strategies and visual acuity outcomes in chronic postoperative Propionibacterium acnes endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1665–70. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90348-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Werner L, Sher JH, Taylor JR, Mamalis N, Nash WA, Csordas JE, et al. Toxic anterior segment syndrome and possible association with ointment in the anterior chamber following cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:227–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2005.12.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avisar R, Weinberger D. Corneal endothelial morphologic features in toxic anterior segment syndrome. Cornea. 2010;29:251–3. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181b11568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreisler KR, Martin SS, Young CW, Anderson CW, Mamalis N. Postoperative inflammation following cataract extraction caused by bacterial contamination of the cleaning bath detergent. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1992;18:106–10. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80391-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bodnar Z, Clouser S, Mamalis N. Toxic anterior segment syndrome: Update on the most common causes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:1902–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]