Abstract

Age at menarche is a marker of timing of puberty in females. It varies widely between individuals, is a heritable trait and is associated with risks for obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, breast cancer and all-cause mortality1. Studies of rare human disorders of puberty and animal models point to a complex hypothalamic-pituitary-hormonal regulation2,3, but the mechanisms that determine pubertal timing and underlie its links to disease risk remain unclear. Here, using genome-wide and custom-genotyping arrays in up to 182,416 women of European descent from 57 studies, we found robust evidence (P<5×10−8) for 123 signals at 106 genomic loci associated with age at menarche. Many loci were associated with other pubertal traits in both sexes, and there was substantial overlap with genes implicated in body mass index and various diseases, including rare disorders of puberty. Menarche signals were enriched in imprinted regions, with three loci (DLK1/WDR25, MKRN3/MAGEL2 and KCNK9) demonstrating parent-of-origin specific associations concordant with known parental expression patterns. Pathway analyses implicated nuclear hormone receptors, particularly retinoic acid and gamma-aminobutyric acid-B2 receptor signaling, among novel mechanisms that regulate pubertal timing in humans. Our findings suggest a genetic architecture involving at least hundreds of common variants in the coordinated timing of the pubertal transition.

Genome-wide array data were available on up to 132,989 women of European descent from 57 studies, and data on up to ~25,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), or their proxy markers, that showed sub-genome-wide significant associations (P<0.0022) with age at menarche in our previous genome-wide association study (GWAS)4 were available on an additional 49,427 women (Supplementary Table 1). Association statistics for 2,441,815 autosomal SNPs that passed quality control measures (including minor allele frequency >1%) were combined across all studies by meta-analysis.

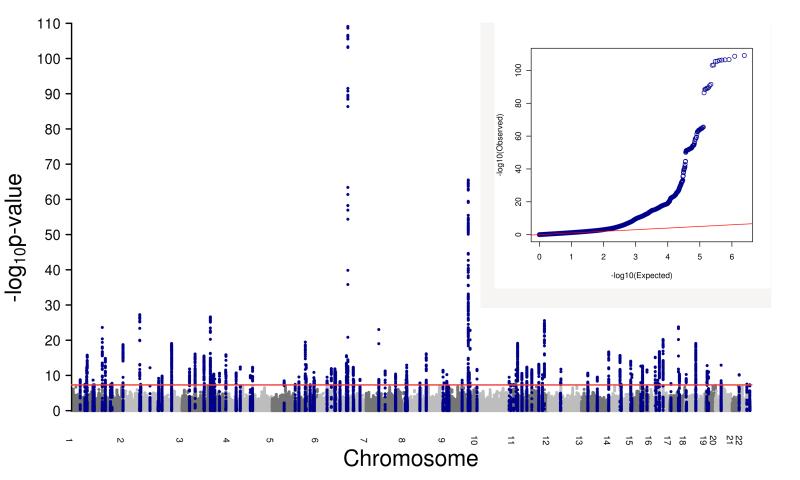

3,915 SNPs reached the genome-wide significance threshold (P<5×10−8) for association with age at menarche (Figure 1). Using GCTA5, which approximates a conditional analysis adjusted for the effects of neighbouring SNPs (Extended Data Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 2), we identified 123 independent signals for age at menarche at 106 genomic loci, including 11 loci containing multiple independent signals (Extended Data Tables 1-4; plots of all loci are available at www.reprogen.org). Of the 42 previously reported independent signals for age at menarche4, all but one (rs2243803, SLC14A2, P=2.3×10−6) remained genome-wide significant in the expanded dataset.

Figure 1. Manhattan and QQ plot of the GWAS for age at menarche.

Manhattan (main panel) and quantile-quantile (QQ) (embedded) plots illustrating results of the genome-wide association study (GWAS) meta-analysis for age at menarche in up to 182,416 women of European descent. The Manhattan plot presents the association -log10 P-values for each genome-wide SNP (Y-axis) by chromosomal position (X-axis). The red line indicates the threshold for genome-wide statistical significance (P=5×10−8). Blue dots represent SNPs whose nearest gene is the same as that of the genome-wide significant signals. The QQ plot illustrates the deviation of association test statistics (blue dots) from the distribution expected under the null hypothesis (red line).

To estimate their overall contribution to the variation in age at menarche, we analysed an additional sample of 8,689 women. 104/123 signals showed directionally-concordant associations or trends with menarche timing (binomial sign test PSign=2.2×10−15), of which 35 showed nominal significance (PSign<0.05) (Supplementary Table 3). In this independent sample, the top 123 SNPs together explained 2.71% (P<1×10−20) of the variance in age at menarche, compared to 1.31% (P=2.3×10−14) explained by the previously reported 42 SNPs. Consideration of further SNPs with lower levels of significance resulted in modest increases in the estimated variance explained with increasingly larger SNP sets, until we included all autosomal SNPs (15.8%, S.E. 3.6%, P=2.2×10−6), indicating a highly polygenic architecture (Extended Data Figure 2).

To test the relevance of menarche loci to the timing of related pubertal characteristics in both sexes, we examined their further associations with refined pubertal stage assessments in an overlapping subset of 10 to 12 years old girls (n=6,147). A further independent sample of 3,769 boys had similar assessments at ages 12 to 15 years. 90/106 menarche loci showed consistent directions of association with Tanner stage in boys and girls combined (PSign=1.1×10−13), 86/106 in girls only (PSign=6.2×10−11) and 72/106 in boys only (PSign=0.0001), suggesting that the menarche loci are highly enriched for variants that regulate pubertal timing more generally (Supplementary Table 4).

Six independent signals were located in imprinted gene regions6, which is an enrichment when compared to all published genome-wide-significant signals for any trait/disease7 (6/123, 4.8% vs 75/4332, 1.7%; Fisher’s Exact test P=0.017). Departure from Mendelian inheritance of pubertal timing has not been previously suspected, therefore we sought evidence for parent-of-origin specific allelic associations in the deCODE Study, which included 35,377 women with parental origins of alleles determined by a combination of genealogy and long-range phasing6.

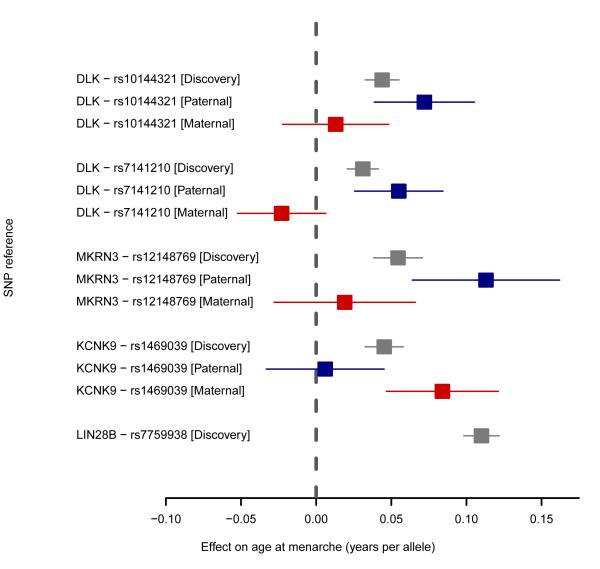

Two independent signals (#85a-b; rs10144321 and rs7141210) lie on chromosome 14q32 harbouring the reciprocally imprinted genes DLK1 and MEG3, which exhibit paternal-specific or maternal-specific expression, respectively, and may underlie the growth retardation and precocious puberty phenotype of maternal uniparental disomy-148. In deCODE, for both signals the paternally-inherited alleles were associated with age at menarche (rs10144321, Ppat=3.1×10−5; rs7141210, Ppat=2.1×10−4), but the maternally-inherited alleles were not (Pmat=0.47 and 0.12, respectively), and there was significant heterogeneity between paternal and maternal effect estimates (rs10144321, Phet=0.02; rs7141210, Phet=2.2×10−4) (Figure 2; Supplementary Table 5). Notably, rs7141210 is reportedly a cis-acting methylation-QTL in adipose tissue9 (Extended Data Table 5) and the menarche age-raising allele was also associated with lower transcript levels of DLK1 (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7)10, which encodes a transmembrane protein involved in adipogenesis and neurogenesis. In deCODE data, the maternally-inherited rs7141210 allele was correlated with blood transcript levels of the maternally-expressed genes MEG3 (Pmat<5.6×10−53), MEG8 (Pmat=4.9×10−41) and MEG9 (Pmat=5.4×10−5); however, lack of any correlation with the paternally-inherited alleles (Ppat=0.18, Ppat=0.87 and Ppat=0.37, respectively) suggests that these genes do not explain this paternal-specific menarche signal.

Figure 2. Forest plot of parent-of-origin specific allelic associations at three imprinted menarche loci.

The forest plot illustrates the associations of variants in four independent genomic signals for age at menarche that are located in three imprinted gene regions. For each variant, squares (and error bars) indicate the estimated per-allele effect sizes on age at menarche in years (and 95% confidence intervals) from the standard additive models in the combined ReproGen meta-analysis (Black), and separately for the paternally-inherited (Blue) or maternally-inherited allele (Red) in up to 35,377 women from the deCODE study. The association for the menarche locus with the largest effect size at LIN28B is also shown for reference, illustrating the similar magnitude of effect size at the MKRN3 locus when parent-of-origin is taken into account.

Signal #86 (rs12148769) lies in the imprinted critical region for Prader Willi Syndrome (PWS), which is caused by paternal-specific deletions of chromosome 15q11-13 and includes clinical features of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and hypothalamic obesity11; conversely a small proportion of cases have precocious puberty. For rs12148769, only the paternally-inherited allele was associated with age at menarche (Ppat=2.4×10−6), but the maternally-inherited allele was not (Pmat=0.43; Phet=5.6×10−3) (Figure 2). Recently, truncating mutations of MAGEL2 affecting the paternal alleles were reported in PWS; all four reported cases had hypogonadism or delayed puberty11, whereas paternally-inherited deleterious mutations in MKRN3 were found in patients with central precocious puberty3. It is as yet unclear which of these paternally-expressed genes explains this menarche signal.

Signal #57 (rs1469039) is intronic in KCNK9, which shows maternal-specific expression in mouse and human brain12. Concordantly, only the maternally-inherited allele was associated with age at menarche (Pmat=5.6×10−6), but the paternally-inherited allele was not (Ppat=0.76; Phet=3.7×10−3) (Figure 2). The menarche age-increasing allele was associated with lower transcript levels of KCNK9 in deCODE’s blood expression data when maternally-inherited (Pmat=0.003), but not when paternally-inherited (Ppat=0.31). KCNK9 encodes TASK-3, which belongs to a family of two-pore domain potassium channels that regulate neuronal resting membrane potential and firing frequency.

The two remaining signals located within imprinted regions (rs2137289 and rs947552) did not demonstrate either paternal or maternal-specific association. We then systematically tested all 117 remaining independent menarche signals for parent-of-origin specific associations with menarche timing and found only 4 (3.4%) with at least nominal associations (Phet<0.05; Supplementary Table 5), which was proportionately fewer than signals at imprinted regions (4/6 (67.0%), Wilcoxon rank sum test P=0.009).

Three menarche signals were in genes encoding JmjC-domain-containing lysine-specific demethylases (enrichment P=0.006 for all genes in this family); signal #1 (rs2274465) is intronic in KDM4A, signal #37 (rs17171818) is intronic in KDM3B, and signal #59b (rs913588) is a missense variant in KDM4C. Notably, KDM3B, KDM4A, and KDM4C all encode activating demethylases for Lysine-9 on histone H3, which was recently identified as the chromatin methylation target that mediates the remarkable long-range regulatory effects of IPW, a paternally-expressed long noncoding RNA in the imprinted PWS region on chromosome 15q11-13, on maternally-expressed genes at the imprinted DLK1-MEG3 locus on chromosome 14q3213. Examination of sub-genome-wide signals showed another potential locus intronic in KDM4B (rs11085110, P=2.3×10−6). Pubertal onset in female mice is reportedly triggered by DNA methylation of the Polycomb group silencing complex of genes (including CBX7 near signal #105) leading to enrichment of activating lysine modifications on histone H314. Specific histone demethylases could potentially regulate cross-links between imprinted regions to influence pubertal timing.

Menarche signals also tended to be enriched in/near genes that underlie rare Mendelian disorders of puberty (enrichment P=0.05)2,3. As well as rs12148769 near to MKRN3, signals were found near LEPR/LEPROT (signal #2; rs10789181), which encodes the leptin receptor, and immediately upstream of TACR3 (signal #32; rs3733631), which encodes the receptor for Neurokinin B. A further variant ~10 kb from GNRH1 approached genome-wide significance (rs1506869, P=1.8×10−6) and was also associated with GNRH1 expression in adipose tissue (P=3.7×10−5). Signals #34 (rs17086188) and #103 (rs852069) lie near PCSK1 and PCSK2, respectively, indicating a common function of the type 1 and 2 prohormone convertases in pubertal regulation. Signals in/near several further genes with relevance to pituitary development/function included: signal #20 (rs7642134) near POU1F1, signal #39 (rs9647570) within TENM2, and signal #42 (rs2479724) near FRS3. Furthermore, signals #71 (rs7103411) and #92 (rs1129700) are cis-eQTLs for LGR4 and TBX6, respectively, both of which encode enhancers for the pituitary development factor SOX2. Signals #52 (rs6964833 intronic in GTF2I) and #104 (rs2836950 intronic in BRWD1) were found in critical regions for complex conditions that include abnormal reproductive phenotypes, Williams-Beuren syndrome (early puberty)15, and Down syndrome (hypogonadism in boys), respectively16.

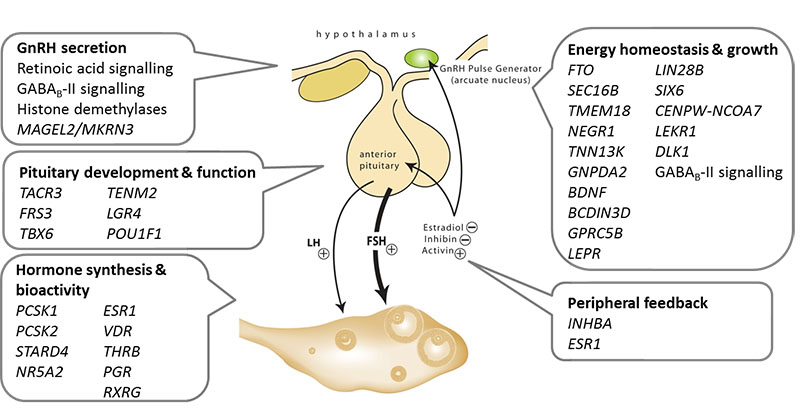

Including signals described above, we identified 29 menarche signals in/near genes with possible roles in hormonal functions (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 8), many more than the three signals we described previously (INHBA, PCSK2 and RXRG)4. Two signals were found in/near genes related to steroidogenesis. Signal 35 (rs251130) was a cis-eQTL for STARD4, which encodes a StAR-related lipid transfer protein involved in the regulation of intra-cellular cholesterol trafficking. Signal #9 (rs6427782) is near NR5A2, which encodes a nuclear receptor with key roles in steroidogenesis and estrogen-dependent cell proliferation.

Figure 3. Schematic diagram indicating possible roles in the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis of several of the implicated genes and biological mechanisms for menarche timing.

We observed that SNPs in/near a custom list of genes that encode nuclear hormone receptors, co-activators or co-repressors were enriched for associations with menarche timing (enrichment P=6×10−5). Individually, nine genome-wide significant signals mapped to within 500 kb of these genes, including those encoding the nuclear receptors for oestrogen, progesterone, thyroid hormone and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Several nuclear hormone receptors are involved in retinoic acid (RA) signaling. SNPs in/near RXRG and RORA reached genome-wide significance, and three other genes contained sub-genome-wide signals (RXRA [rs2520094, P=4×10−7], RORB [rs4237264, P=9.4×10−6], RXRB [rs241438, P=7.1×10−5]). Two other genome-wide significant signals mapped to genes with roles in RA function (#67 CTBP2 and #101 RDH8). The active metabolites of vitamin A, all-trans-RA and 9-cis-RA, have differential effects on GnRH expression and secretion17. Other possible mechanisms linking RA signaling to pubertal timing include inhibition of embryonic GnRH neuron migration, and enhancement of steroidogenesis and gonadotrophin secretion18. The relevance of our findings to observations of low circulating vitamin A levels and use of dietary vitamin A in delayed puberty19 are yet unclear.

To identify other mechanisms that regulate pubertal timing, we tested all SNPs genome-wide for collective enrichment across any biological pathway defined in publicly available databases. The top ranked pathway reaching study-wise significance (FDR=0.009) was gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAB) receptor II signaling (Extended Data Table 6); each of the nine genes in this pathway contained a SNP with sub-genome-wide significant association with menarche (Extended Data Table 7). Notably, GABAB receptor activation inhibits hypothalamic GnRH secretion in animal models20.

Regarding the relevance of our findings to other traits, we confirmed4 and extended the overlap between genome-wide significant loci for menarche and adult BMI21. At all nine loci (in/near FTO, SEC16B, TMEM18, NEGR1, TNNI3K, GNPDA2, BDNF, BCDIN3D and GPRC5B) the menarche age-raising allele was also associated with lower adult BMI (Supplementary Table 9). Three menarche signals overlapped known loci for adult height22. The menarche age-raising alleles at signals #47c (rs7759938, LIN28B) and #83 (rs1254337, SIX6) were also associated with taller adult height, which is directionally concordant with epidemiological observations. Conversely, the menarche age-raising allele at signal #48 (rs4895808, CENPW/NCOA7) was associated with shorter adult height (Supplementary Table 9).

Further menarche signals overlapped reported GWAS loci for other traits, but in each case at only a single locus, therefore possibly reflecting small-scale pleiotropy rather than a broader shared genetic aetiology. Signal #26 (rs900400) was a cis-eQTL for LEKR1, and is the same lead SNP associated with birth weight23. The menarche age-raising allele was also associated with higher birth weight, directionally concordant with epidemiological observations24. Signal #48 (rs4895808, a cis-eQTL for CENPW) is in LD (r2=0.90) with the lead SNP for the autoimmune disorder type 1 diabetes, rs938848925, which also showed robust association with menarche timing (P=6.49×10−12). Signal #41 (rs16896742) is near HLA-A, which encodes the class I, A major histocompatibility complex, and is a known locus for various immunity or inflammation-related traits7. Signal #50 (rs6933660) is near ESR1, which encodes the oestrogen receptor, a known locus for breast cancer26 and bone mineral density27. Notably, the menarche age-raising allele at rs6933660 was associated with higher femoral neck bone mineral density (P=6×10−5)27, which is directionally discordant with the epidemiological association28. Signal #70 (rs11022756) is intronic in ARNTL, a known locus for circulating plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) levels29; the reported lead SNP (rs6486122) for PAI-129 also showed robust association with menarche timing (P=9.3×10−10).

Our findings indicate both BMI-related and BMI-independent mechanisms that could underlie the epidemiological associations between early menarche and higher risks of adult disease1.These include actions of LIN28B on insulin sensitivity through the mTOR pathway, GABAB receptor signaling on inhibition of oxidative stress-related ß-cell apoptosis, and SIRT3 (mitochondrial sirtuin 3), which could link early life nutrition to metabolism and ageing. Finally, only few parent-of-origin specific allelic associations at imprinted loci have been described for complex traits6. Our findings implicate differential pubertal timing, a trait with putative selection advantages30, as a potential additional target for the evolution of genomic imprinting.

METHODS

GWAS meta-analysis

We performed an expanded GWAS meta-analysis for self-reported age at menarche in up to 182,416 women of European descent from 58 studies (Supplementary Table 1). All participants provided written informed consent and the studies were approved by the respective Local Research Ethics committees or Institutional Review Boards. Consistent with our previous analysis protocol4, women who reported their age at menarche as < 9 years or > 17 years were excluded from the analysis; birth year was included as the only covariate to allow for the secular trends in menarche timing. Genome-wide SNP array data were available on up to 132,989 women from 57 studies. Each study imputed genotype data based on HapMap Phase II CEU build 35 or 36. Data on an additional 49,427 women from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC) were generated on the Illumina iSelect "iCOGS" array31. This array included up to ~25,000 SNPs, or their proxy markers, that showed sub-genome-wide associations (P<0.0022) with age at menarche in our earlier GWAS4. SNPs were excluded from individual study datasets if they were poorly imputed or were rare (MAF <1%). Test statistics for each study were adjusted using study-specific genomic control inflation factors and where appropriate individual studies performed additional adjustments for relatedness (Supplementary Table 1). Association statistics for each of the 2,441,815 autosomal SNPs that passed QC in at least half of the studies were combined across studies in a fixed effects inverse-variance meta-analysis implemented in METAL32.

On meta-analysis, 3,915 SNPs reached the genome-wide significance threshold (P<5×10−8) for association with age at menarche (Figure 1). The overall GC inflation factor was 1.266, consistent with an expected high yield of true positive findings in large-scale GWAS meta-analysis of highly polygenic traits33.

Selection of independent signals

Given the genome-wide results of the meta-analysis, SNPs showing evidence for association at genome-wide significant P-values were selected and clumped based on a physical (kb) threshold <1 Mb. The lead SNPs of the 105 clumps formed constitute the list of SNPs independently associated with age at menarche (Extended Data Tables 1-4).

To augment this list we performed approximate conditional analysis using GCTA software34, where the LD between variants was estimated from the Northern Finland Birth Cohort (NFBC66) consisting of 5,402 individuals of European ancestry with GWAS data imputed using CEU haplotypes from Hapmap Phase II. Assuming that the LD correlations between SNPs more than 10 Mb away or on different chromosomes are zero, we performed the GCTA model selection to select SNPs independently associated with age at menarche at genome-wide significant P-values. This software selected as independently associated with age at menarche 115 SNPs at 98 loci, 11 of which had two or more signals of association (six loci contained two signals, four loci contained three signals, and one locus contained four signals). Plots of all 106 loci are available at www.reprogen.org. SNPs with A/T or C/G alleles were excluded from this analysis to prevent strand issues leading to false-positive results.

To summarize the information obtained from the single-SNP and GCTA analyses, the 105 SNPs selected from the uni-variate analysis and the 115 SNPs selected from the GCTA model selection analysis were combined into a single list of signals independently associated with age at menarche (Supplementary Table 2), using the following selection process (Extended Data Figure 1). For loci with no evidence of allelic heterogeneity, if the uni-variate signal was genome-wide significant, the lead uni-variate SNP was selected (94 independent association signals follow this criterion); otherwise the lead GCTA SNP was selected instead (one independent signal). For loci where evidence for allelic heterogeneity was found, all signals identified in the GCTA joint model were selected if GCTA selected the uni-variate index SNP (21 independent signals at 8 loci) or a very good proxy (r2>0.8) (7 independent signals at 3 loci). When instead GCTA selected a SNP independent from the uni-variate index SNP, both the lead uni-variate SNP and all signals identified in the GCTA joint model were selected (0 independent signals).

To determine likely causal genes at each locus, we used a combination of criteria. The gene nearest to each top SNP was selected by default. This gene was replaced or added to if the top SNP was (in high LD with) an expression quantitative-trait locus (eQTL) or a non-synonymous variant in another gene, or if there was an alternative neighbouring biological candidate gene. 31/123 signals mapped as eQTLs in data from Westra et al. (E)10, five were annotated as non-synonymous functional (F), 60 as biological candidates (C), and four mapped to gene deserts (nearest gene >500 kb) (Supplementary Tables 6-8). We also used publicly available whole blood and adipose tissue methylation-QTL data to map 9/123 signals to cis-acting changes in methylation level (Extended Data Table 5)9.

Follow up in the EPIC-InterAct study

We used an independent sample of 8689 women from the EPIC-InterAct study35 to follow-up our menarche signals. To test associations between each identified SNP and age at menarche with correction for cryptic relatedness, we ran a linear mixed model association test implemented in GCTA34 (--mlma-loco option), adjusting for birth year, disease status and research centre. Given the relatively small sample size compared to our discovery set, directional consistency with results from the discovery-meta analysis was assessed using a binomial sign test. Variance explained by menarche loci was estimated using restricted maximum likelihood analysis in GCTA34. In addition to the 123 confirmed menarche loci, variance explained in subsets of menarche loci below the genome-wide significance thresholds was also assessed.

eQTL analyses

In order to estimate the potential downstream regulatory effects of age at menarche associated variants, we used publicly available blood eQTL data (downloadable from http://genenetwork.nl/bloodeqtlbrowser/) from a recently published paper by Westra et al. (2013)10. Westra et al. conducted cis-eQTL mapping by testing, for a large set of genes, all SNPs (HapMap2 panel) within 250 kb of the transcription start site of the gene for association with total RNA expression level of the gene. The publicly available data contain, for each gene, a list of all SNPs that were found to be significantly associated with gene expression using a False Discovery Rate (FDR) of 5%. For a detailed description of the quality control measures applied to the original data, see Westra et al10. Their meta-analysis was based on a pooled sample of 5,311 individuals from 7 population-based cohorts with gene expression levels measured from full blood. We used the software tool SNAP (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/snap/) to identify variants in close linkage disequilibrium (r2 ≥ 0.8) with the trait associated variants. All eQTL effects at FDR 5% and also lists of the strongest SNP effect for all the significant genes are shown in Supplementary Table 7.

Index SNPs (or highly correlated proxies) were also interrogated against a collected database of eQTL results from a range of tissues. Blood cell related eQTL studies included fresh lymphocytes36, fresh leukocytes37, leukocyte samples in individuals with Celiac disease38, whole blood samples39–43, lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCL) derived from asthmatic children44,45, HapMap LCL from 3 populations46, a separate study on HapMap CEU LCL47, additional LCL population samples48–50 (and Mangravite et al. (unpublished)), CD19+ B cells51, primary PHA-stimulated T cells48, CD4+ T cells52, peripheral blood monocytes51,53,54, CD11+ dendritic cells before and after Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection55. Micro-RNA QTLs56 and DNase-I QTLs57 were also queried for LCL. Non-blood cell tissue eQTLs searched included omental and subcutaneous adipose39,50,58, stomach58, endometrial carcinomas59, ER+ and ER- breast cancer tumor cells60, brain cortex53,61,62, pre-frontal cortex63,64, frontal cortex65, temporal cortex62,65, pons65, cerebellum62,65, 3 additional large studies of brain regions including prefrontal cortex, visual cortex and cerebellum, respectively66, liver58,67–70, osteoblasts71, intestine72, lung73, skin50,74 and primary fibroblasts48. Micro-RNA QTLs were also queried for gluteal and abdominal adipose75. Only results that reach study-wise significance thresholds in their respective datasets were included (Supplementary table 6). Expression data was also available on adipose tissue and whole blood samples from deCODE where parent-of-origin specific analyses were possible.

Parent-of-origin specific associations

Evidence for parent-of-origin specific allelic associations at imprinted loci was sought in the deCODE Study, which included 35,377 women with parental origins of alleles determined by a combination of genealogy and long-range phasing as previously described6. Briefly, using SNP chip data in each proband, genome-wide, long range phasing was applied to overlapping tiles, each 6 cM in length, with 3 cM overlap between consecutive tiles. For each tile, the parental origins of the two phased haplotypes were determined regardless of whether the parents of the proband were chip-typed. Using the Icelandic genealogy database, for each of the two haplotypes of a proband, a search was performed to identify, among those individuals also known to carry the same haplotype, the closest relative on each of the paternal and maternal sides. Results for the two haplotypes were combined into a robust single-tile score reflecting the relative likelihood of the two possible parental origin assignments. Haplotypes from consecutive tiles were then stitched together based on sharing at the overlapping region. For haplotypes derived by stitching, a contig-score for parental origin was computed by summing the individual single-tile scores. Similarly, parent-of-origin specific allelic associations at imprinted loci were also sought in the deCODE blood cells and adipose tissue expression datasets.

Pathway analyses

Meta-Analysis Gene-set Enrichment of variaNT Associations (MAGENTA) was used to explore pathway-based associations in the full GWAS dataset. MAGENTA implements a gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) based approach, as previously described76. Briefly, each gene in the genome is mapped to a single index SNP with the lowest P-value within a 110 kb upstream, 40 kb downstream window. This P-value, representing a gene score, is then corrected for confounding factors such as gene size, SNP density and LD-related properties in a regression model. Genes within the HLA-region were excluded from analysis due to difficulties in accounting for gene density and LD patterns. Each mapped gene in the genome is then ranked by its adjusted gene score. At a given significance threshold (95th and 75th percentiles of all gene scores), the observed number of gene scores in a given pathway, with a ranked score above the specified threshold percentile, is calculated. This observed statistic is then compared to 1,000,000 randomly permuted pathways of identical size. This generates an empirical GSEA P-value for each pathway. Significance was determined when an individual pathway reached a false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05 in either analysis. In total, 2529 pathways from Gene Ontology, PANTHER, KEGG and Ingenuity were tested for enrichment of multiple modest associations with age at menarche. MAGENTA software was also used for enrichment testing of custom gene sets.

Relevance of menarche loci to other traits

We assessed the relevance of identified menarche loci to other traits by comparing SNPs significantly associated with age at menarche with published GWAS findings or by using publicly available data from the Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits (GIANT) consortium22,21 and the GEnetic Factors for OS (GEFOS) consortium27. In addition, we requested look-ups up the 123 menarche SNPs for association with puberty timing assessed by Tanner staging in the Early Growth Genetics (EGG) consortium77.

Supplementary Material

Extended Data Figure 1 | Flow chart illustrating the selection criteria used to identify independent signals for age at menarche.

Extended Data Figure 2 | Estimates of genetic variance explained. Variance in age at menarche in the EPIC-InterAct replication sample (N=8689) explained by combined sets of SNPs defined by their strength of association in the discovery set.

Extended Data Table 1 | Details of the 123 independent signals for menarche ming at 106 genomic loci – signals #1 to 30

1. All positions mapped to Hapmap build 36.

2. Novel indicates previously unidentified loci. If the locus was established, r-sq refers to the linkage disequilibrium between the reported SNP and the previous signal. Some regions with known associations and no prior evidence for allelic heterogeneity now have multiple independent signals.

3. Alleles/freq refers to the menarche age increasing allele (from the uni-variate SNP discovery), and the decreasing allele / increasing allele frequencies from meta-analysis study estimates

4. Uni-variate models included only one SNP per model

5. Joint models were performed using GCTA software. These models approximate conditional analysis; i.e. the effect estimates are adjusted for the effects of other neighbouring SNPs

6. Gene refers to the consensus gene(s) reported at that locus mapped using 4 approaches: (N) Nearest, (C) Biological Candidate, (F) 1000 Genomes missense variant in high LD (r2 > 0.8), (E) gene expression linked by eQTL. See Supplementary tables 5, 7 and 8 for more information.

Extended Data Table 2 | Details of the 123 independent signals for menarche ming at 106 genomic loci – signals #31 to 58

1. All positions mapped to Hapmap build 36.

2. Novel indicates previously unidentified loci. If the locus was established, r-sq refers to the linkage disequilibrium between the reported SNP and the previous signal. Some regions with known associations and no prior evidence for allelic heterogeneity now have multiple independent signals.

3. Alleles/freq refers to the menarche age increasing allele (from the uni-variate SNP discovery), and the decreasing allele / increasing allele frequencies from meta-analysis study estimates

4. Uni-variate models included only one SNP per model

5. Joint models were performed using GCTA software. These models approximate conditional analysis; i.e. the effect estimates are adjusted for the effects of other neighbouring SNPs

6. Gene refers to the consensus gene(s) reported at that locus mapped using 4 approaches: (N) Nearest, (C) Biological Candidate, (F) 1000 Genomes missense variant in high LD (r2 > 0.8), (E) gene expression linked by eQTL. See Supplementary tables 5, 7 and 8 for more information.

Extended Data Table 3 | Details of the 123 independent signals for menarche ming at 106 genomic loci – signals #59 to 87

1. All positions mapped to Hapmap build 36.

2. Novel indicates previously unidentified loci. If the locus was established, r-sq refers to the linkage disequilibrium between the reported SNP and the previous signal. Some regions with known associations and no prior evidence for allelic heterogeneity now have multiple independent signals.

3. Alleles/freq refers to the menarche age increasing allele (from the uni-variate SNP discovery), and the decreasing allele / increasing allele frequencies from meta-analysis study estimates

4. Uni-variate models included only one SNP per model

5. Joint models were performed using GCTA software. These models approximate conditional analysis; i.e. the effect estimates are adjusted for the effects of other neighbouring SNPs

6. Gene refers to the consensus gene(s) reported at that locus mapped using 4 approaches: (N) Nearest, (C) Biological Candidate, (F) 1000 Genomes missense variant in high LD (r2 > 0.8), (E) gene expression linked by eQTL. See Supplementary tables 5, 7 and 8 for more information.

Extended Data Table 4 | Details of the 123 independent signals for menarche ming at 106 genomic loci – signals #88 to 106

1. All positions mapped to Hapmap build 36.

2. Novel indicates previously unidentified loci. If the locus was established, r-sq refers to the linkage disequilibrium between the reported SNP and the previous signal. Some regions with known associations and no prior evidence for allelic heterogeneity now have multiple independent signals.

3. Alleles/freq refers to the menarche age increasing allele (from the uni-variate SNP discovery), and the decreasing allele / increasing allele frequencies from meta-analysis study estimates

4. Uni-variate models included only one SNP per model

5. Joint models were performed using GCTA software. These models approximate conditional analysis; i.e. the effect estimates are adjusted for the effects of other neighbouring SNPs

6. Gene refers to the consensus gene(s) reported at that locus mapped using 4 approaches: (N) Nearest, (C) Biological Candidate, (F) 1000 Genomes missense variant in high LD (r2 > 0.8), (E) gene expression linked by eQTL. See Supplementary tables 5, 7 and 8 for more information.

Extended data table 5 | Methylation QTLs based on Illumina 450K whole blood and adipose methylome data in 648 twins.

1. mQTLs were derived for associations between genotypes and methylation in 648 adipose samples from the MuTHER study using a 1% FDR level, corresponding to P<8.6×10−41. Significant mQTLs were also tested for replication in whole blood in 200 individuals.

2. Methylation data available from Grundberg et al. 2013. The American Journal of Human Genetics, Volume 93, Issue 6, 5 December 2013, Page 1158

3. Methylation betas are presented per menarche-age-increasing allele.

Extended data table 6 | MAGENTA pathway analyses. Results are shown for database pathways and custom pathways that reached study-wise statistical significance (FDR < 0.05).

1. Genes denotes number of genes in pathway (number of genes successfully mapped by MAGENTA).

2. Enrichment denotes expected number of genes at enrichment threshold (observed number of genes).

3. Genes for Mendelian pubertal disorders, as described in References 2 & 3.

Extended data table 7 | GABAB receptor II signaling pathway genes.

Acknowledgements

A full list of acknowledgements can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information Supplementary information contains: Supplementary Tables and Figures, acknowledgements, author disclosures.

Data deposition statement

Plots of all 106 menarche loci and genome-wide summary level statistics are available at the ReproGen Consortium website: www.reprogen.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prentice P, Viner RM. Pubertal timing and adult obesity and cardiometabolic risk in women and men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 2013;37:1036–43. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silveira LFG, Latronico AC. Approach to the patient with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98:1781–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abreu AP, et al. Central precocious puberty caused by mutations in the imprinted gene MKRN3. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:2467–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elks CE, et al. Thirty new loci for age at menarche identified by a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:1077–85. doi: 10.1038/ng.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang J, et al. Conditional and joint multiple-SNP analysis of GWAS summary statistics identifies additional variants influencing complex traits. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:369–75. S1–3. doi: 10.1038/ng.2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kong A, et al. Parental origin of sequence variants associated with complex diseases. Nature. 2009;462:868–74. doi: 10.1038/nature08625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hindorff LA, et al. [Accessed 1st Nov 2013];A catalog of published genome-wide association studies. Available at: www.genome.gov/gwastudies.

- 8.Temple IK, Shrubb V, Lever M, Bullman H, Mackay DJG. Isolated imprinting mutation of the DLK1/GTL2 locus associated with a clinical presentation of maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 14. J. Med. Genet. 2007;44:637–40. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.050807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grundberg E, et al. Global analysis of DNA methylation variation in adipose tissue from twins reveals links to disease-associated variants in distal regulatory elements. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;93:876–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westra H-J, et al. Systematic identification of trans eQTLs as putative drivers of known disease associations. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1238–43. doi: 10.1038/ng.2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaaf CP, et al. Truncating mutations of MAGEL2 cause Prader-Willi phenotypes and autism. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1405–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruf N, et al. Sequence-based bioinformatic prediction and QUASEP identify genomic imprinting of the KCNK9 potassium channel gene in mouse and human. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:2591–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stelzer Y, Sagi I, Yanuka O, Eiges R, Benvenisty N. The noncoding RNA IPW regulates the imprinted DLK1-DIO3 locus in an induced pluripotent stem cell model of Prader-Willi syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ng.2968. advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lomniczi A, et al. Epigenetic control of female puberty. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:281–9. doi: 10.1038/nn.3319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Partsch C-J, et al. Central precocious puberty in girls with Williams syndrome. J. Pediatr. 2002;141:441–4. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.127280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grinspon RP, et al. Early onset of primary hypogonadism revealed by serum anti-Müllerian hormone determination during infancy and childhood in trisomy 21. Int. J. Androl. 2011;34:e487–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2011.01210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho S, et al. 9-cis-Retinoic acid represses transcription of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) gene via proximal promoter region that is distinct from all-transretinoic acid response element. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2001;87:214–22. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagl F, et al. Retinoic acid-induced nNOS expression depends on a novel PI3K/Akt/DAX1 pathway in human TGW-nu-I neuroblastoma cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C1146–56. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00034.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zadik Z, Sinai T, Zung A, Reifen R. Vitamin A and iron supplementation is as efficient as hormonal therapy in constitutionally delayed children. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf) 2004;60:682–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Constantin S, et al. GnRH neuron firing and response to GABA in vitro depend on acute brain slice thickness and orientation. Endocrinology. 2012;153:3758–69. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Speliotes EK, et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat Genet. 2010;42:937–948. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lango Allen H, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010;467:832–838. doi: 10.1038/nature09410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horikoshi M, et al. New loci associated with birth weight identify genetic links between intrauterine growth and adult height and metabolism. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:76–82. doi: 10.1038/ng.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Aloisio AA, DeRoo LA, Baird DD, Weinberg CR, Sandler DP. Prenatal and infant exposures and age at menarche. Epidemiology. 2013;24:277–84. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31828062b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrett JC, et al. Genome-wide association study and meta-analysis find that over 40 loci affect risk of type 1 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:703–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng W, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a new breast cancer susceptibility locus at 6q25.1. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:324–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Estrada K, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 56 bone mineral density loci and reveals 14 loci associated with risk of fracture. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:491–501. doi: 10.1038/ng.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parker SE, et al. Menarche, menopause, years of menstruation, and the incidence of osteoporosis: the influence of prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;99:594–601. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang J, et al. Genome-wide association study for circulating levels of PAI-1 provides novel insights into its regulation. Blood. 2012;120:4873–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-436188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Migliano AB, Vinicius L, Lahr MM. Life history trade-offs explain the evolution of human pygmies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:20216–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708024105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references cited in the Methods

- 31.Michailidou K, et al. Large-scale genotyping identifies 41 new loci associated with breast cancer risk. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:353–61. 361e1–2. doi: 10.1038/ng.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2190–1. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang J, et al. Genomic inflation factors under polygenic inheritance. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;19:807–12. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langenberg C, et al. Design and cohort description of the InterAct Project: an examination of the interaction of genetic and lifestyle factors on the incidence of type 2 diabetes in the EPIC Study. Diabetologia. 2011;54:2272–82. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2182-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Göring HHH, et al. Discovery of expression QTLs using large-scale transcriptional profiling in human lymphocytes. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1208–16. doi: 10.1038/ng2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Idaghdour Y, et al. Geographical genomics of human leukocyte gene expression variation in southern Morocco. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:62–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heap GA, et al. Complex nature of SNP genotype effects on gene expression in primary human leucocytes. BMC Med. Genomics. 2009;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emilsson V, et al. Genetics of gene expression and its effect on disease. Nature. 2008;452:423–8. doi: 10.1038/nature06758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fehrmann RSN, et al. Trans-eQTLs reveal that independent genetic variants associated with a complex phenotype converge on intermediate genes, with a major role for the HLA. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mehta D, et al. Impact of common regulatory single-nucleotide variants on gene expression profiles in whole blood. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;21:48–54. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maeda T, et al. The correlation between clinical laboratory data and telomeric status of male patients with metabolic disorders and no clinical history of vascular events. Aging Male. 2011;14:21–6. doi: 10.3109/13685538.2010.502270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sasayama D, et al. Identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms regulating peripheral blood mRNA expression with genome-wide significance: an eQTL study in the Japanese population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dixon AL, et al. A genome-wide association study of global gene expression. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1202–7. doi: 10.1038/ng2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liang L, et al. A cross-platform analysis of 14,177 expression quantitative trait loci derived from lymphoblastoid cell lines. Genome Res. 2013;23:716–26. doi: 10.1101/gr.142521.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stranger BE, et al. Population genomics of human gene expression. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1217–24. doi: 10.1038/ng2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kwan T, et al. Genome-wide analysis of transcript isoform variation in humans. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:225–31. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dimas AS, et al. Common regulatory variation impacts gene expression in a cell type-dependent manner. Science. 2009;325:1246–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1174148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cusanovich DA, et al. The combination of a genome-wide association study of lymphocyte count and analysis of gene expression data reveals novel asthma candidate genes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:2111–23. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grundberg E, et al. Mapping cis- and trans-regulatory effects across multiple tissues in twins. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1084–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fairfax BP, et al. Genetics of gene expression in primary immune cells identifies cell type-specific master regulators and roles of HLA alleles. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:502–10. doi: 10.1038/ng.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murphy A, et al. Mapping of numerous disease-associated expression polymorphisms in primary peripheral blood CD4+ lymphocytes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:4745–57. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heinzen EL, et al. Tissue-specific genetic control of splicing: implications for the study of complex traits. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zeller T, et al. Genetics and beyond--the transcriptome of human monocytes and disease susceptibility. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barreiro LB, et al. Deciphering the genetic architecture of variation in the immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:1204–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115761109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang RS, et al. Population differences in microRNA expression and biological implications. RNA Biol. 8:692–701. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.4.16029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Degner JF, et al. DNase I sensitivity QTLs are a major determinant of human expression variation. Nature. 2012;482:390–4. doi: 10.1038/nature10808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Greenawalt DM, et al. A survey of the genetics of stomach, liver, and adipose gene expression from a morbidly obese cohort. Genome Res. 2011;21:1008–16. doi: 10.1101/gr.112821.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kompass KS, Witte JS. Co-regulatory expression quantitative trait loci mapping: method and application to endometrial cancer. BMC Med. Genomics. 2011;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li Q, et al. Integrative eQTL-based analyses reveal the biology of breast cancer risk loci. Cell. 2013;152:633–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Webster JA, et al. Genetic control of human brain transcript expression in Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;84:445–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zou F, et al. Brain expression genome-wide association study (eGWAS) identifies human disease-associated variants. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Colantuoni C, et al. Temporal dynamics and genetic control of transcription in the human prefrontal cortex. Nature. 2011;478:519–23. doi: 10.1038/nature10524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu C, et al. Whole-genome association mapping of gene expression in the human prefrontal cortex. Mol. Psychiatry. 2010;15:779–84. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gibbs JR, et al. Abundant quantitative trait loci exist for DNA methylation and gene expression in human brain. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang B, et al. Integrated systems approach identifies genetic nodes and networks in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2013;153:707–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schadt EE, et al. Mapping the genetic architecture of gene expression in human liver. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Innocenti F, et al. Identification, replication, and functional fine-mapping of expression quantitative trait loci in primary human liver tissue. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sulzbacher S, Schroeder IS, Truong TT, Wobus AM. Activin A-induced differentiation of embryonic stem cells into endoderm and pancreatic progenitors-the influence of differentiation factors and culture conditions. Stem Cell Rev. 2009;5:159–73. doi: 10.1007/s12015-009-9061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schröder A, et al. Genomics of ADME gene expression: mapping expression quantitative trait loci relevant for absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of drugs in human liver. Pharmacogenomics J. 2013;13:12–20. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grundberg E, et al. Population genomics in a disease targeted primary cell model. Genome Res. 2009;19:1942–52. doi: 10.1101/gr.095224.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kabakchiev B, Silverberg MS. Expression quantitative trait loci analysis identifies associations between genotype and gene expression in human intestine. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1488–96. 1496.e1–3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hao K, et al. Lung eQTLs to help reveal the molecular underpinnings of asthma. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ding J, et al. Gene Expression in Skin and Lymphoblastoid Cells: Refined Statistical Method Reveals Extensive Overlap in cis-eQTL Signals. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;87:779–789. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rantalainen M, et al. MicroRNA expression in abdominal and gluteal adipose tissue is associated with mRNA expression levels and partly genetically driven. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Segrè AV, Groop L, Mootha VK, Daly MJ, Altshuler D. Common inherited variation in mitochondrial genes is not enriched for associations with type 2 diabetes or related glycemic traits. PLoS Genet. 2010;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cousminer DL, et al. Genome-wide association study of sexual maturation in males and females highlights a role for body mass and menarche loci in male puberty. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu150. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Extended Data Figure 1 | Flow chart illustrating the selection criteria used to identify independent signals for age at menarche.

Extended Data Figure 2 | Estimates of genetic variance explained. Variance in age at menarche in the EPIC-InterAct replication sample (N=8689) explained by combined sets of SNPs defined by their strength of association in the discovery set.

Extended Data Table 1 | Details of the 123 independent signals for menarche ming at 106 genomic loci – signals #1 to 30

1. All positions mapped to Hapmap build 36.

2. Novel indicates previously unidentified loci. If the locus was established, r-sq refers to the linkage disequilibrium between the reported SNP and the previous signal. Some regions with known associations and no prior evidence for allelic heterogeneity now have multiple independent signals.

3. Alleles/freq refers to the menarche age increasing allele (from the uni-variate SNP discovery), and the decreasing allele / increasing allele frequencies from meta-analysis study estimates

4. Uni-variate models included only one SNP per model

5. Joint models were performed using GCTA software. These models approximate conditional analysis; i.e. the effect estimates are adjusted for the effects of other neighbouring SNPs

6. Gene refers to the consensus gene(s) reported at that locus mapped using 4 approaches: (N) Nearest, (C) Biological Candidate, (F) 1000 Genomes missense variant in high LD (r2 > 0.8), (E) gene expression linked by eQTL. See Supplementary tables 5, 7 and 8 for more information.

Extended Data Table 2 | Details of the 123 independent signals for menarche ming at 106 genomic loci – signals #31 to 58

1. All positions mapped to Hapmap build 36.

2. Novel indicates previously unidentified loci. If the locus was established, r-sq refers to the linkage disequilibrium between the reported SNP and the previous signal. Some regions with known associations and no prior evidence for allelic heterogeneity now have multiple independent signals.

3. Alleles/freq refers to the menarche age increasing allele (from the uni-variate SNP discovery), and the decreasing allele / increasing allele frequencies from meta-analysis study estimates

4. Uni-variate models included only one SNP per model

5. Joint models were performed using GCTA software. These models approximate conditional analysis; i.e. the effect estimates are adjusted for the effects of other neighbouring SNPs

6. Gene refers to the consensus gene(s) reported at that locus mapped using 4 approaches: (N) Nearest, (C) Biological Candidate, (F) 1000 Genomes missense variant in high LD (r2 > 0.8), (E) gene expression linked by eQTL. See Supplementary tables 5, 7 and 8 for more information.

Extended Data Table 3 | Details of the 123 independent signals for menarche ming at 106 genomic loci – signals #59 to 87

1. All positions mapped to Hapmap build 36.

2. Novel indicates previously unidentified loci. If the locus was established, r-sq refers to the linkage disequilibrium between the reported SNP and the previous signal. Some regions with known associations and no prior evidence for allelic heterogeneity now have multiple independent signals.

3. Alleles/freq refers to the menarche age increasing allele (from the uni-variate SNP discovery), and the decreasing allele / increasing allele frequencies from meta-analysis study estimates

4. Uni-variate models included only one SNP per model

5. Joint models were performed using GCTA software. These models approximate conditional analysis; i.e. the effect estimates are adjusted for the effects of other neighbouring SNPs

6. Gene refers to the consensus gene(s) reported at that locus mapped using 4 approaches: (N) Nearest, (C) Biological Candidate, (F) 1000 Genomes missense variant in high LD (r2 > 0.8), (E) gene expression linked by eQTL. See Supplementary tables 5, 7 and 8 for more information.

Extended Data Table 4 | Details of the 123 independent signals for menarche ming at 106 genomic loci – signals #88 to 106

1. All positions mapped to Hapmap build 36.

2. Novel indicates previously unidentified loci. If the locus was established, r-sq refers to the linkage disequilibrium between the reported SNP and the previous signal. Some regions with known associations and no prior evidence for allelic heterogeneity now have multiple independent signals.

3. Alleles/freq refers to the menarche age increasing allele (from the uni-variate SNP discovery), and the decreasing allele / increasing allele frequencies from meta-analysis study estimates

4. Uni-variate models included only one SNP per model

5. Joint models were performed using GCTA software. These models approximate conditional analysis; i.e. the effect estimates are adjusted for the effects of other neighbouring SNPs

6. Gene refers to the consensus gene(s) reported at that locus mapped using 4 approaches: (N) Nearest, (C) Biological Candidate, (F) 1000 Genomes missense variant in high LD (r2 > 0.8), (E) gene expression linked by eQTL. See Supplementary tables 5, 7 and 8 for more information.

Extended data table 5 | Methylation QTLs based on Illumina 450K whole blood and adipose methylome data in 648 twins.

1. mQTLs were derived for associations between genotypes and methylation in 648 adipose samples from the MuTHER study using a 1% FDR level, corresponding to P<8.6×10−41. Significant mQTLs were also tested for replication in whole blood in 200 individuals.

2. Methylation data available from Grundberg et al. 2013. The American Journal of Human Genetics, Volume 93, Issue 6, 5 December 2013, Page 1158

3. Methylation betas are presented per menarche-age-increasing allele.

Extended data table 6 | MAGENTA pathway analyses. Results are shown for database pathways and custom pathways that reached study-wise statistical significance (FDR < 0.05).

1. Genes denotes number of genes in pathway (number of genes successfully mapped by MAGENTA).

2. Enrichment denotes expected number of genes at enrichment threshold (observed number of genes).

3. Genes for Mendelian pubertal disorders, as described in References 2 & 3.

Extended data table 7 | GABAB receptor II signaling pathway genes.